4.1. Dataset

We conducted experiments on a Mandarin multi-speaker speech dataset, AISHELL-3[

41], and a Mandarin multi-singer singing dataset, M4Singer[

42], to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method in both speech and singing voice conversion tasks.

(1) AISHELL-3

AISHELL-3 is a high-quality multi-speaker Mandarin speech synthesis dataset released by AISHELL Foundation. It contains 218 speakers (where the male-to-female ratio is balanced) and more than 85000 speech sentences, the total duration is about 85 hours, and the sampling rate is 44.1kHz. A 16-bit, professional recording environment made clear sound quality possible. In order to construct the speech test set, in this study, we randomly selected 10 of the speakers to be excluded from training, and from each, we randomly selected 10 speech samples, totaling 100 speech samples.

(2) M4Singer

M4Singer is a large-scale Chinese singing voice dataset with multiple styles and multiple singers released by Tsinghua University. The dataset contains 30 professional singers (where the male-to-female ratio is balanced) and a total of 16000 singing sentences, the total duration is 18.8 hours, and the sampling rate is 44.1kHz. It was generated in a 16-bit, clean, and noise-free recording environment and covers pop, folk, rock, and other styles. Similar to the above, 10 singers were randomly selected to be excluded from training, and 10 singing samples were selected for each singer, for a singing test set totaling 100 samples.

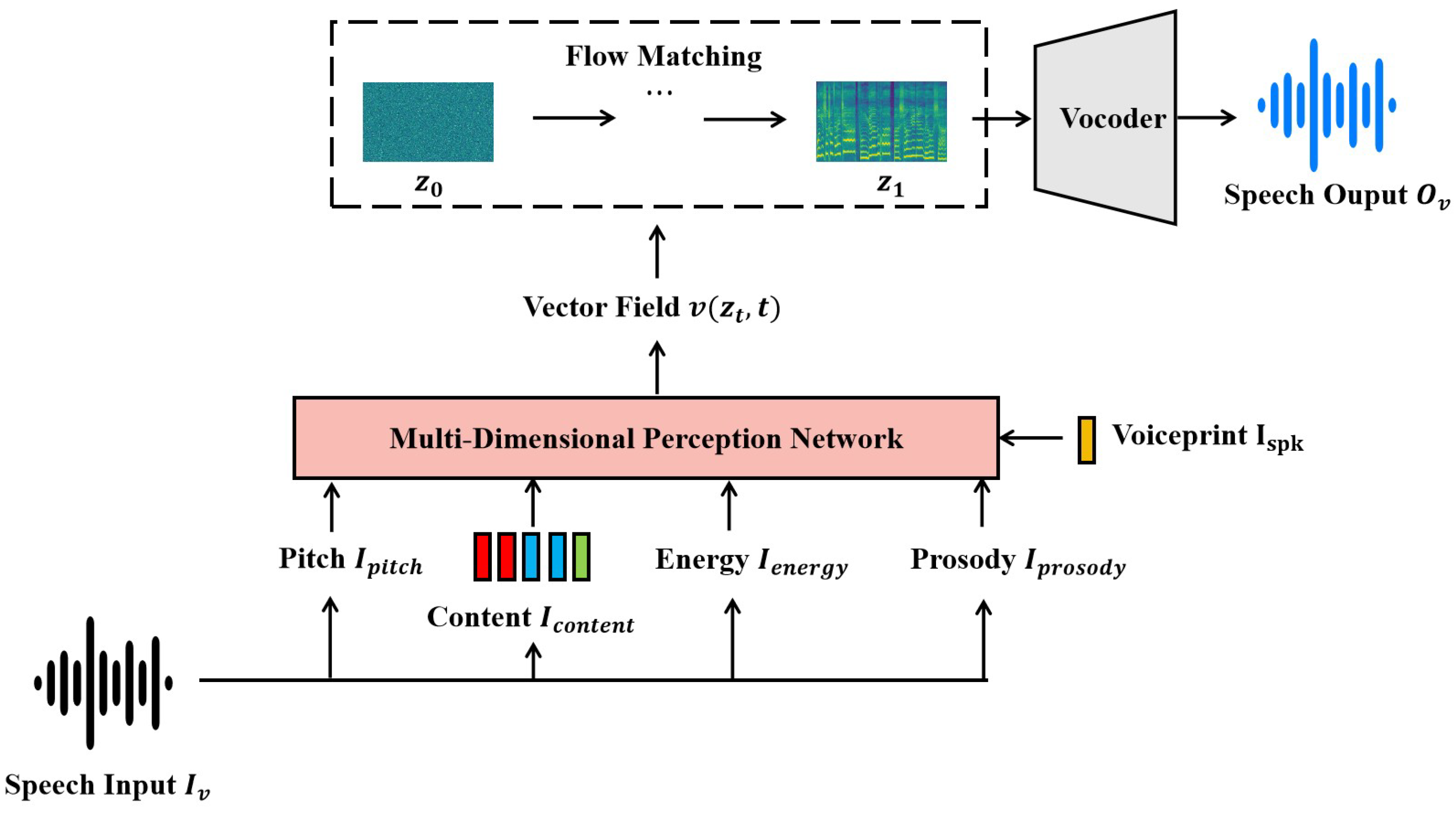

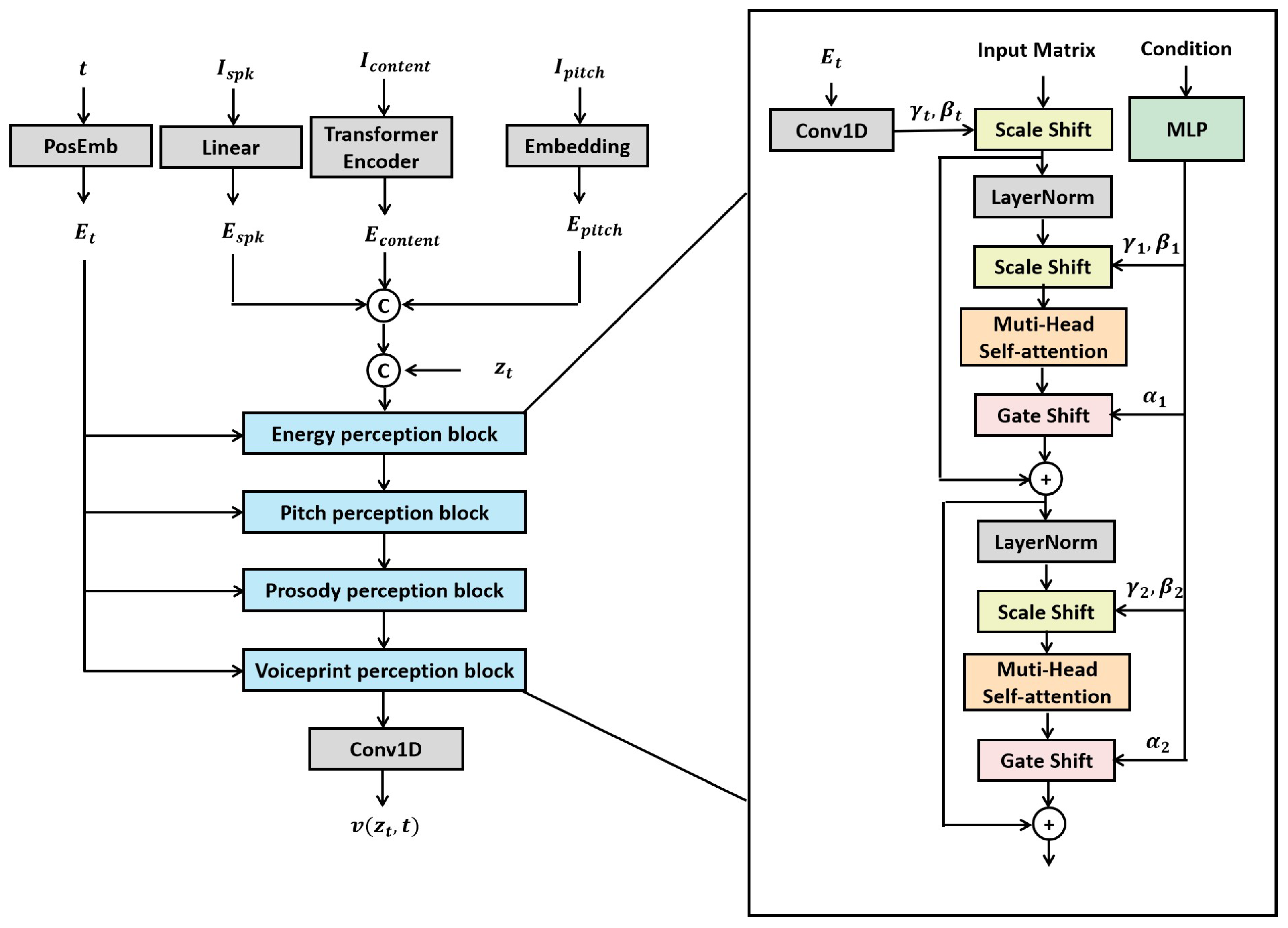

4.2. Data processing

In this study, multiple key features were extracted from the original speech data, including content representation (

), speaker voiceprint (

), pitch (

), energy (

), prosody (

), and the target mel spectrogram. The content representation,

, was extracted by using a pre-trained automatic speech recognition model, SenseVoice[

43], which provides high-precision linguistic features. Speaker identity features

were obtained by using the pre-trained speaker verification model Camplus[

44], which captures speaker-dependent characteristics. Pitch information

was extracted by using the pre-trained neural pitch estimation model RMVPE[

45], which directly derives pitch features from raw audio, ensuring high accuracy and robustness. Energy

was calculated as the root mean square (RMS) energy of each frame in the speech signal. Prosodic features

were extracted by using the neural prosody encoder HuBERT-Soft[

46], which captures rhythm, intonation, and other prosodic cues in speech. The target mel spectrogram was computed with a standard signal processing pipeline consisting of pre-emphasis, framing, windowing, Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT), power spectrum calculation, and mel filterbank projection. The configuration details are as follows: a sampling rate of 32,000 Hz, a pre-emphasis coefficient of 0.97, a frame length of 1024, a frame shift of 320, the Hann window function, and 100 mel filterbank channels.

4.5. Baseline models and evaluation metrics

(1) Baseline models

1) Free-VC[

24] (2022, ICASSP) is a voice conversion model that adopts the variational autoencoder architecture of VITS for high-quality waveform reconstruction; it is widely used in voice conversion tasks due to its efficient feature modeling capabilities.

2) Diff-VC[

32] (2022, ICLR) is a diffusion model-based voice conversion method which can generate high-quality converted speech based on noise reconstruction; it is the representative diffusion model for VC tasks.

3) DDDM-VC[

33] (2024, AAAI) is a newly proposed feature decoupling speech conversion method based on a diffusion model which improves the quality of converted speech and speaker consistency while maintaining the consistency of speech features.

(2) Evaluation index

1) Mean Opinion Score (MOS): The naturalness of the synthesized speech was evaluated by 10 students with good Mandarin skills and sound sense as the audience.

2) Mel Cepstral Distortion (MCD): It measures the spectral distance between the converted speech and the target speech, where a lower value indicates higher-quality conversion.

3) Word Error Rate (WER): The intelligibility of the converted speech was evaluated by using automatic speech recognition, where a lower WER indicates higher speech intelligibility.

4) Similarity Mean Opinion Score (SMOS): Listeners (10 students with good Mandarin skills and sound sense) scored the timbre similarity of the synthesized speech for us to measure the subjective similarity of the timbre after speech conversion.

5) Speaker Embedding Cosine Similarity (SECS): The cosine similarity between the original speech and the converted speech was calculated based on the speaker coding, which is used to objectively measure the degree of timbre preservation. The higher the value is, the closer the converted speech is to the target timbre.

4.6. Experimental results

(1) Quality evaluation of voice conversion

The primary goals of the voice conversion (VC) task are to transform the speaker’s timbre while preserving the original linguistic content and maximize the naturalness and intelligibility of the generated speech. To this end, we evaluated the proposed method on the speech test set by using both subjective and objective metrics. Subjective evaluation was conducted based on Mean Opinion Score (MOS) tests, while objective performance was quantified by using Mel Cepstral Distortion (MCD) and the Word Error Rate (WER). This combination provides a comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of different voice conversion approaches.

As shown in

Table 1, the proposed algorithm, MPFM-VC, demonstrates superior performance in the voice conversion task, achieving the highest scores in terms of naturalness, audio fidelity, and speech clarity. Compared with existing methods, MPFM-VC exhibits stronger stability across multiple evaluation metrics, indicating its ability to maintain high-quality synthesis under varying data conditions. Specifically, MPFM-VC achieves an 11.57% improvement in the MOS over Free-VC, showing significant advantages in speech continuity and prosody control and effectively avoiding the distortion issues commonly observed in traditional end-to-end VITS-based frameworks. In comparison with diffusion-based models such as Diff-VC and DDDM-VC, MPFM-VC achieves the lowest MCD (6.23) and the lowest WER (4.23%), which suggests that it better preserves the semantic content of the target speaker during conversion, thereby enhancing the intelligibility and clarity of the generated speech. These results highlight that the integration of multi-dimensional feature perception modeling and content perturbation-based training augmentation significantly improves the model’s ability to adapt to various speech features. Consequently, MPFM-VC delivers consistent and high-quality voice synthesis across different speakers and speaking contexts.

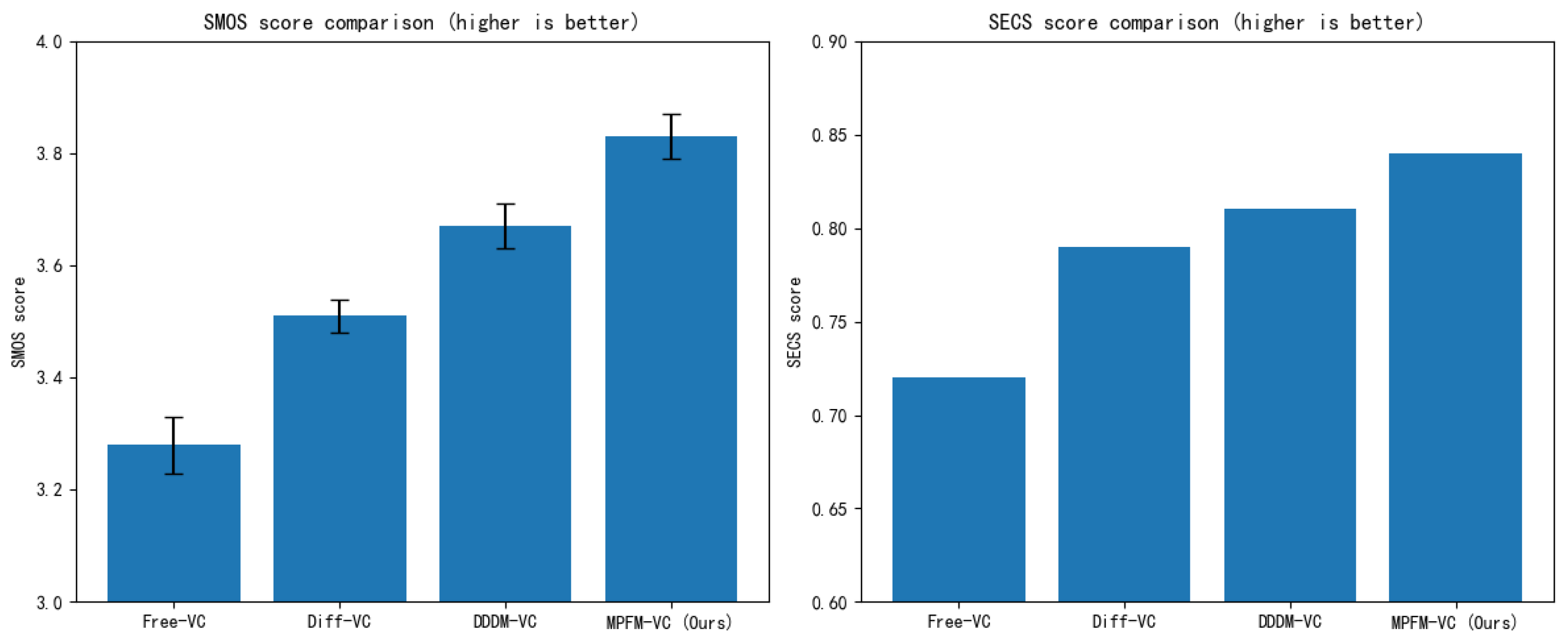

(2) Timbre similarity evaluation of voice conversion

The goal of speaker similarity evaluation is to assess a voice conversion method’s ability to preserve the timbre consistency of the target speaker. In this study, we adopt two metrics for analysis: Similarity MOS (SMOS) and Speaker Embedding Cosine Similarity (SECS).

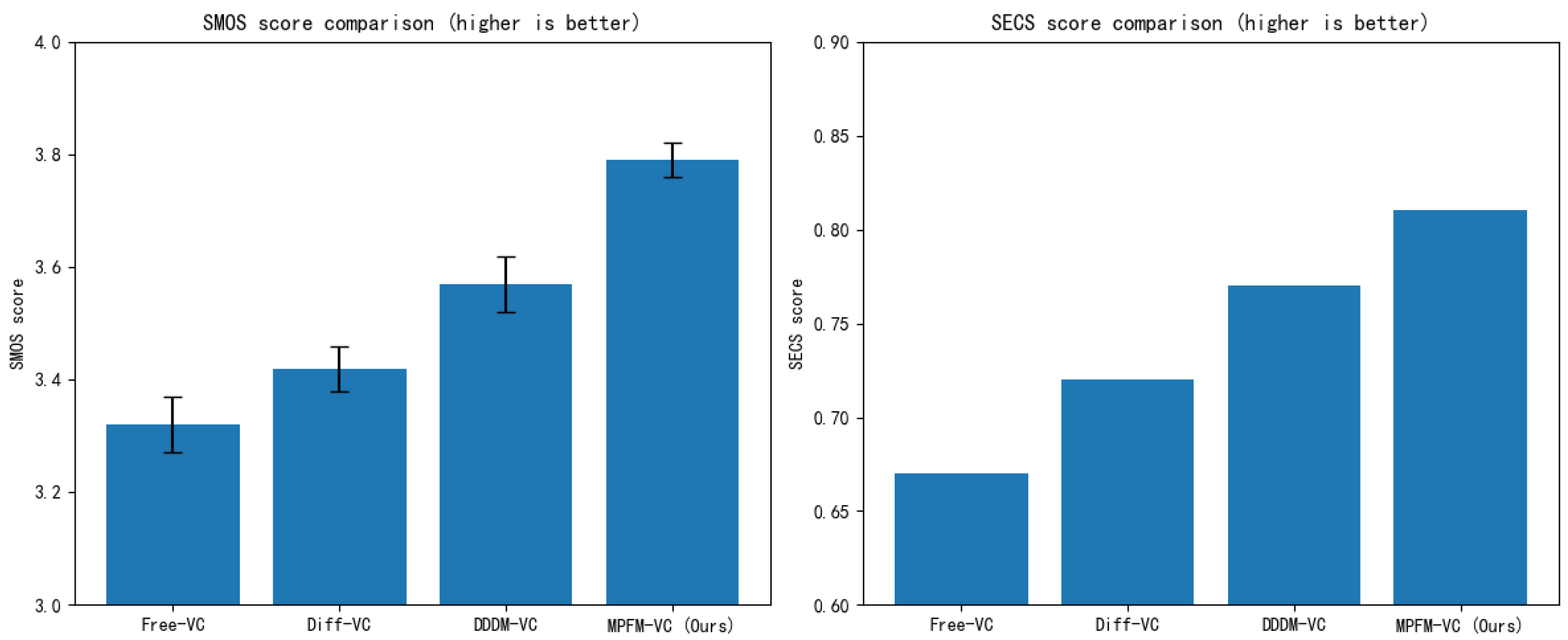

As shown in

Table 2 and

Figure 7, MPFM-VC demonstrates strong speaker consistency in the speaker similarity evaluation task, achieving the highest SMOS (3.83) and SECS (0.84) scores. This indicates that MPFM-VC is more effective in preserving the timbral characteristics of the target speaker during conversion. Compared with Free-VC, MPFM-VC enhances the model’s adaptability to target speaker embeddings through multi-dimensional feature perception modeling, thereby improving post-conversion timbre similarity. Although Diff-VC benefits from diffusion-based generation, which improves overall audio quality to some extent, it fails to sufficiently disentangle speaker identity features, resulting in residual characteristics from the source speaker in the converted speech. While DDDM-VC introduces feature disentanglement mechanisms that improve speaker similarity, it still falls short compared with MPFM-VC. These findings suggest that the combination of flow matching modeling and adversarial training on speaker embeddings in MPFM-VC effectively suppresses unwanted speaker information leakage during conversion. As a result, the synthesized speech is perceptually closer to the target speaker’s voice while maintaining naturalness and improving controllability and stability in voice conversion tasks.

(3) Quality evaluation of singing voice conversion

In the context of voice conversion, singing voice conversion is generally more challenging than standard speech conversion due to its inherently richer pitch variations, timbre stability, and prosodic complexity. We adopted the same set of evaluation metrics used in speech conversion to comprehensively evaluate the performance of different models on the singing voice conversion task, including the subjective Mean Opinion Score (MOS) and objective indicators such as Mel Cepstral Distortion (MCD) and the Word Error Rate (WER).

As shown in

Table 3, MPFM-VC also demonstrates outstanding performance on the singing voice conversion task, achieving a MOS of 4.12, an MCD of 6.32, and a WER of 4.86%.Through multi-dimensional feature perception modeling, MPFM-VC effectively adapts to melodic variations and pitch fluctuations inherent in singing voices, resulting in converted outputs that are more natural and fluent while maintaining high levels of audio quality and clarity. Compared with Free-VC, MPFM-VC further improves the naturalness of the generated singing voices by leveraging flow matching, which enhances the modeling of dynamic acoustic features during conversion. In contrast to diffusion-based methods such as Diff-VC and DDDM-VC, MPFM-VC avoids the timbre over-smoothing often introduced by diffusion models, which can lead to the loss of fine-grained acoustic details. As a result, the synthesized singing voices generated by MPFM-VC exhibit greater depth, expressiveness, and structural richness.

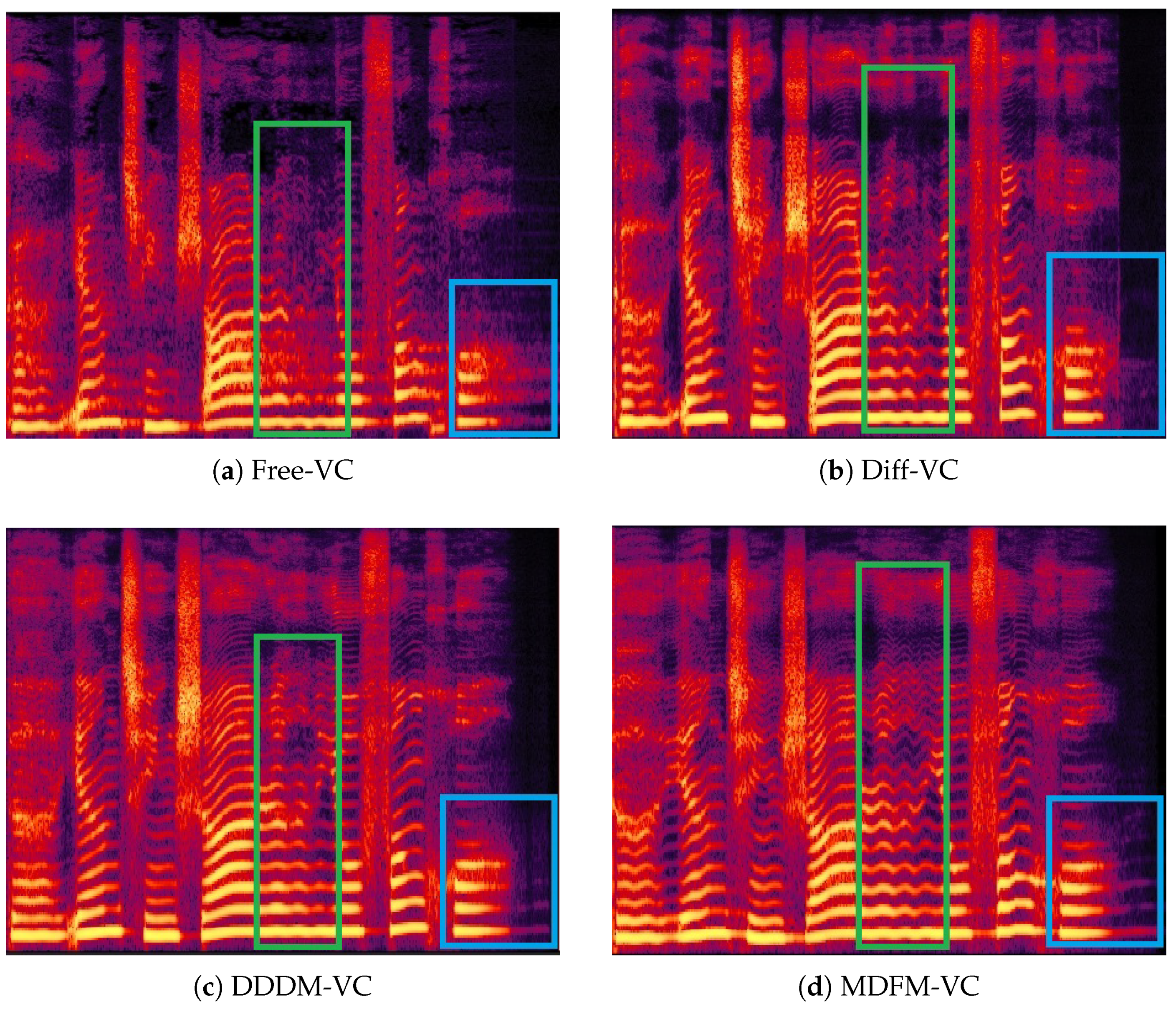

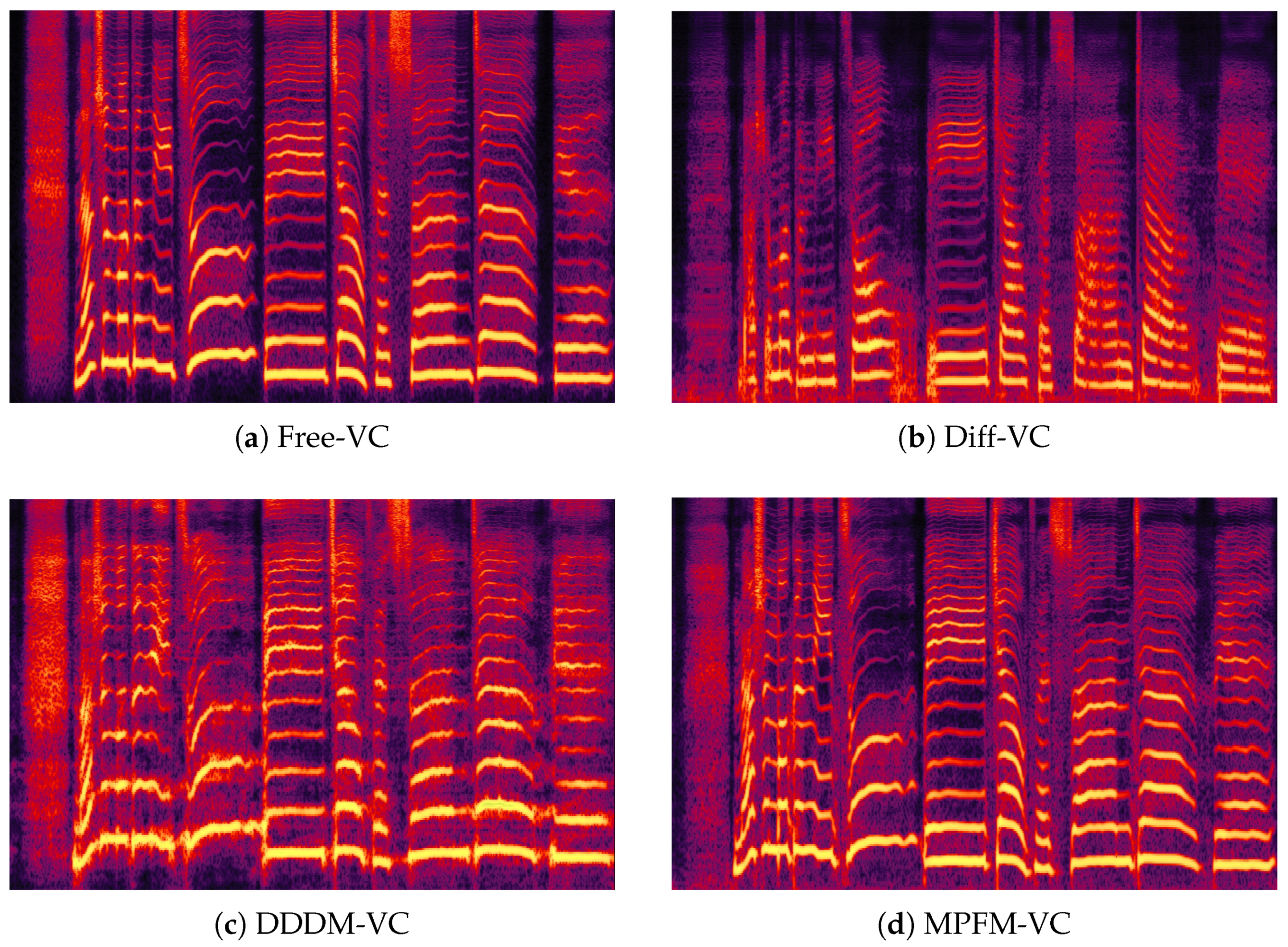

Additionally, we randomly selected a singing voice segment for spectrogram comparison, as shown in

Figure 8. The proposed MDFM-VC produces the clearest and most well-defined spectrogram, benefiting from the additional feature inputs of the multi-dimensional perception network, which allow the model to reconstruct finer acoustic details such as vibrato and tail articulations more accurately. In contrast, although DDDM-VC and Diff-VC are also capable of generating spectrograms with strong intensity and clarity, their outputs tend to suffer from over-smoothing, which results in the loss of important contextual and prosodic information—diminishing the expressive detail in the converted singing voice.

(4) Timbre similarity evaluation of singing voice conversion

Timbre similarity in singing voices is a critical metric for evaluating a model’s ability to preserve the target singer’s vocal identity during conversion. Compared with normal speech, singing involves more complex pitch variations, formant structures, prosodic patterns, and timbre continuity, which pose additional challenges for accurate speaker similarity modeling. In this study, we performed a comprehensive evaluation by using both subjective SMOS (Similarity MOS) and objective SECS (Speaker Embedding Cosine Similarity) to assess the effectiveness of different methods in capturing and preserving timbral consistency in singing voice conversion.

As shown in

Table 4 and

Figure 9, MPFM-VC achieves superior performance in singing voice timbre similarity evaluation. It outperforms traditional methods in both SMOS (3.79) and SECS (0.81), indicating its ability to more accurately preserve the target singer’s timbral identity. In singing voice conversion, Free-VC and Diff-VC fail to sufficiently disentangle content and speaker representations, leading to perceptible timbre distortion and poor alignment with the target voice. Although the diffusion-based DDDM-VC model partially solves this issue, it still suffers from timbre over-smoothing, resulting in synthesized singing voices that lack distinctiveness and individuality. In contrast, MPFM-VC incorporates an adversarial speaker disentanglement strategy, which effectively suppresses residual source speaker information and ensures that the converted singing voice more closely resembles the target singer’s timbre. Additionally, MPFM-VC enables the fine-grained modeling of timbral variation with a multi-dimensional feature-aware flow matching mechanism, leading to improved timbre stability and consistency throughout the conversion process.

(5) Robustness Evaluation under Low-Quality Conditions

In real-world applications, voice conversion systems must exhibit robustness to low-quality input data in order to maintain reliable performance under adverse conditions such as background noise, limited recording hardware, or unclear articulation by the speaker. To assess this capability, we additionally collected a set of 30 low-quality speech samples that incorporate common noise-related challenges, including mumbling, background reverberation, ambient noise, signal clipping, and low-bitrate encoding.

As shown in

Table 5 and the spectrograms in

Figure 10, the proposed algorithm, MPFM-VC, demonstrates strong performance even under low-quality speech conditions. The generated spectrograms remain sharp and well defined, indicating high-fidelity synthesis, whereas other voice conversion systems exhibit significantly degraded robustness—resulting in reduced naturalness and timbre consistency in the converted outputs. In particular, diffusion-based models such as Diff-VC and DDDM-VC suffer from substantial performance degradation in noisy environments, with spectrograms appearing blurry and incomplete. This suggests that diffusion models have limited stability under extreme data conditions and are less effective in handling perturbations introduced by low-quality inputs. Moreover, Diff-VC performs the worst in both the MCD and WER metrics, indicating a large mismatch between its generated mel spectrograms and the target speech, as well as a severe decline in speech intelligibility. These results reveal that Diff-VC is highly sensitive to input noise, making it less suitable for real-world applications where input quality cannot be guaranteed.

It is worth noting that although Free-VC showed relatively weaker performance in previous experiments, it still outperforms diffusion-based architectures under low-quality speech conditions. Its generated spectrograms appear only slightly blurred, indicating that the end-to-end variational autoencoder (VAE)-based modeling approach offers a certain degree of robustness to noise. However, its SECS score remains significantly lower than that of MPFM-VC, suggesting persistent inaccuracies in timbre matching.

In contrast, MPFM-VC consistently maintains superior speech quality and speaker consistency even under low-quality input conditions. It achieves the best performance across all evaluation metrics—including MOS, MCD, WER, and SMOS—and its spectrograms remain sharp and vibrant. This advantage can be attributed to the multi-dimensional feature-aware flow matching mechanism, which enables the fine-grained modeling of speech features under varying noise conditions. Additionally, the content perturbation-based training augmentation strategy allows the model to adapt to incomplete or degraded inputs during training, resulting in greater robustness during inference. Furthermore, the adversarial training on speaker embeddings enhances timbre preservation under noisy conditions, allowing MPFM-VC to significantly outperform other methods in SECS and more accurately retain the target speaker’s timbral characteristics.

4.7. Ablation experiments

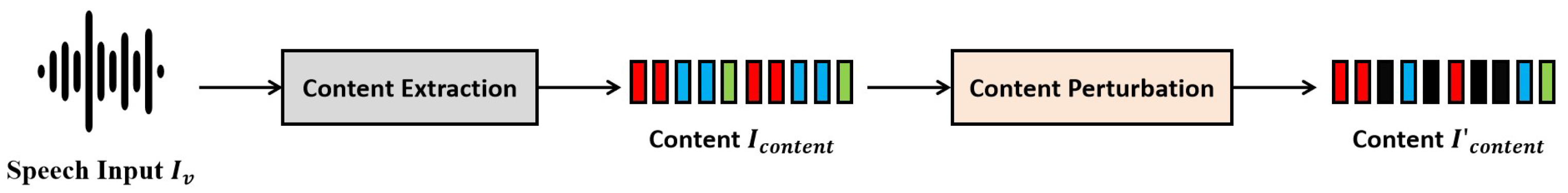

(1) Content perturbation-based training enhancement method

In the voice conversion task, the content perturbation-based training augmentation strategy is designed to improve model generalization by introducing controlled perturbations to content representations during training. This approach aims to reduce inference-time artifacts such as unexpected noise and improve the overall stability of the converted speech. To validate the effectiveness of this method, we conducted an ablation study by removing the content perturbation mechanism and observing its impact on speech conversion performance. A test set consisting of 100 out-of-distribution audio samples with varying durations was used to simulate real-world scenarios under complex conditions. The following evaluation metrics were determined: MOS, MCD, WER, SMOS, SECS, and the frequency of plosive artifacts per 10 seconds in converted speech (Badcase).

As shown in

Table 6, the content perturbation-based training augmentation strategy plays a crucial role in improving the stability and robustness of the voice conversion model. Specifically, after removing this module, the Badcase rate increases significantly—from 0.39 to 1.52 occurrences per 10 seconds—indicating a higher frequency of artifacts such as plosive noise, interruptions, or other unexpected distortions under complex, real-world conditions. In addition, both MCD and WER show slight increases, suggesting a decline in the acoustic fidelity and intelligibility of the converted speech.

Interestingly, a minor improvement is observed in the MOS, which may be attributed to the model’s tendency to overfit the training distribution when not exposed to adversarial or perturbed inputs. As a result, the model performs better on in-domain evaluation sets but suffers from reduced generalization and greater output variability when tested on more challenging, out-of-distribution audio samples with varying durations. It is also worth noting that the SMOS and SECS remain largely unchanged, implying that content perturbation primarily contributes to improving speech stability, rather than influencing timbre consistency.

In summary, the proposed content perturbation strategy effectively reduces unexpected artifacts and enhances the stability and generalization capability of the voice conversion system. These findings confirm that incorporating this method is critical to maintaining high speech quality under diverse and noisy-input conditions and thus holds significant practical value in real-world deployment scenarios.

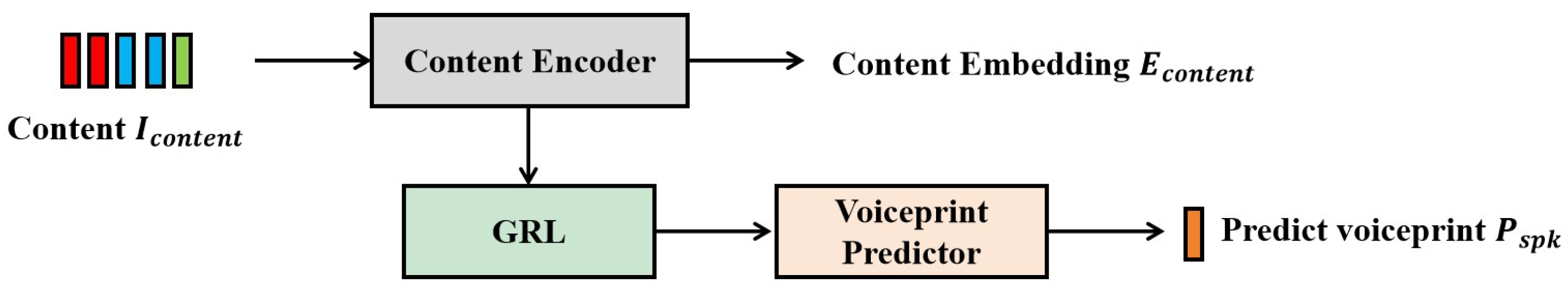

(2) Adversarial training mechanism based on voiceprint

In the voice conversion task, the strategy of adversarial training on speaker embeddings is designed to enhance the timbre similarity to the target speaker while suppressing residual speaker identity information from the source speaker. This ensures that the converted speech better matches the target speaker’s voice without compromising the overall speech quality. To evaluate the effectiveness of this strategy, we conducted an ablation study by removing the adversarial training module and comparing its impact on timbre similarity and overall speech quality in the converted outputs.

As shown in

Table 7, the strategy of adversarial training on speaker embeddings plays a critical role in improving timbre matching in the voice conversion task. Specifically, after removing this module, both the SMOS and SECS drop significantly—the SMOS decreases from 3.83 to 3.62, and SECS drops from 0.84 to 0.73. This indicates a notable decline in target timbre consistency, as the converted speech becomes more susceptible to residual characteristics from the source speaker, leading to suboptimal conversion performance.

On the other hand, the MOS and MCD remain largely unchanged, suggesting that adversarial training primarily enhances timbre similarity without significantly affecting overall speech quality. Interestingly, the WER shows a slight improvement, implying that removing the adversarial mechanism may enhance intelligibility and clarity. However, this improvement likely comes at the cost of timbre fidelity; in other words, while the output speech may sound clearer, it deviates more from the target speaker’s vocal identity, resulting in less precise conversion.

Overall, the speaker adversarial training strategy ensures accurate timbre alignment by suppressing residual speaker identity features from the source, making the converted speech more consistent with the desired voice. Although some quality metrics slightly improve when the module is removed, this is primarily due to the model reverting to generic or averaged timbre features, rather than capturing the distinct timbral traits of the target speaker. Therefore, in practical applications, adversarial training remains essential to achieving high-quality voice conversion—ensuring that the generated speech is not only intelligible but also accurately timbre-matched to the intended target speaker.