1.

Take home message: This study did not find that caffeine (0.003g/kg body weight) or sodium bicarbonate (0.3 g/kg body weight) provided ergogenic effects on chest press or knee extension resistance training performance. 1. Introduction

Supplements, including caffeine and sodium bicarbonate consumption, are commonly used to enhance exercise performance (Kilding et al., 2012). Since caffeine’s removal from the World Anti-Doping Agency’s prohibited substances list in 2004, there is a renewed interest in caffeine supplementation (Del Coso et al., 2011). Caffeine is consumed globally on a daily basis in many forms to reduce fatigue and perceived effort while increasing alertness and vigour through the antagonization of adenosine receptors in the central nervous system (Ribeiro and Sebastião, 2010; Ferragut et al., 2024).

Muscular strength output is affected by various neural factors, including enhanced motor unit recruitment, synchronization, rate coding, and neuromuscular inhibition (Behm, 1995; Grgic et al., 2019). Caffeine-induced adenosine receptor antagonization can also increase motor unit recruitment; hence caffeine’s popularity as an ergogenic supplement for high-intensity physical tasks across sports modalities (Guest et al., 2021). In addition to neural effects, caffeine can also increase mobilization, and myofibrillar sensitivity of calcium ions (Ferreira et al. 2022). Further ergogenic benefits of decreased pain perception and increased endurance have led to caffeine being a beneficial supplement for aerobic sports, however fewer investigations have explicitly focused on resistance exercise (Del Coso et al., 2011; Grgic et al., 2019; 2021a;b; Guest et al., 2021). Domaszewski et al. (2021) reported reduced muscle contraction time following the ingestion of 9mg/kg of caffeine. Reports on the magnitude of caffeine’s ergogenic effects range from positive to no effect to negative effects on athletic performance (Martins et al., 2020; Guest et al., 2021). A recent umbrella meta-analysis of 9 meta-analyses reported that caffeine increased muscle strength and endurance primarily with male participants who consumed the caffeine typically 60 minutes prior to testing (Bilondi et al. 2024).

Further, research has proposed intracellular water content as an indicator for muscle strength in certain populations (Serra-Prat et al., 2020), likely due to the effect of fluid volume on energy metabolism (Schoffstall et al., 2001). As such, studies report increased intracellular hydration in resistance-trained males and females (Ribeiro et al., 2014; Cholewa et al., 2018). Contrary to the general belief that caffeine is dehydrating due to diuretic effects, studies show no such effects during exercise when hydration was measured via fluid retention and urine output (Silva et al., 2013; Antonio et al., 2024). Regarding caffeine dosage, it has been established that 3-9 mg/kg of body weight may elicit an exercise performance enhancement; however, researchers have noted that gaps exist concerning lower caffeine doses on short-burst anaerobic exercise (Sabol et al., 2019; Siquier-Coll et al., 2023).

Whereas caffeine impacts the central nervous system and muscle calcium sensitivity, supplements such as sodium bicarbonate can enhance high-intensity exercise or sports performance by acting as a metabolic acidic buffer at the peripheral level of the active muscle (Hadzic et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2022). Exercise-induced acidosis can induce muscular fatigue when the rate of hydrogen ion (H+) production exceeds the rate of removal (McNaughton et al., 2016). The use of a buffering agent such as sodium bicarbonate can help to counterbalance H+ acidosis, thus reducing fatigue (McNaughton et al., 2016). Studies have shown that sodium bicarbonate can act as both an ergogenic and ergolytic substance (i.e., side effects of gastrointestinal upset can adversely affect performance) (Hadzic et al., 2019). A position stand by the International Society of Sports Nutrition (Grgic et al. 2021a) states that sodium bicarbonate supplementation can improve muscle endurance and exercise performance for both men and women (optimal dose of 0.3 g/kg taken 60-180 minutes before exercise).

The bicarbonate buffering capacity has implications for the gastric system, specifically the stomach and duodenum by neutralizing gastric acid (Hadzic et al., 2019). Participants that have ingested sodium bicarbonate have experienced gastrointestinal upset, nausea, diarrhea, and vomiting (Hadzic et al., 2019). Many factors are known to affect the efficacy of supplementation in improving exercise outcomes, such as dosage, timing, and training status (Saunders et al., 2022). Therefore, dosing is critical when administering sodium bicarbonate for ergogenic effects. The most commonly utilized dosage of sodium bicarbonate in exercise science literature is 0.3g/kg of body weight (Hadzic et al., 2019).

Disparities exist within the literature on the effects of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate supplementation on each sex (Saunders et al., 2022; Montalvo-Alonso et al., 2024). Research into nutritional supplements for women has been scarce and needs more attention (Grgic et al., 2021a;b; Saunders et al., 2022). The common exclusion of female participants from sports science research has been routinely justified based on menstrual hormonal changes (Lew et al., 2022). This approach has led to the inequality between male and female data in the field of supplement research for enhancing exercise performance (Grgic et al., 2021a;b; Saunders et al., 2022).

As there are fewer studies directly comparing caffeine and sodium bicarbonate acute supplementation effects especially with women, this study aimed to assess and compare the efficacy of an acute dose of caffeine (neuromuscular stimulant) and sodium bicarbonate (peripheral metabolic buffer) as an ergogenic aid for knee extension (KE) and chest press resistance (CP) training. This study included both women and men, thus contributing more female data to an underrepresented field. We hypothesized that sodium bicarbonate and caffeine supplementation would enhance exercise performance by increasing repetitions and reducing participants' ratings of perceived exertion similarly in both male and female participants compared to the placebo.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

This study included data from 12 participants (mean age: 21.7 ± 1.4 years, range 20-25 years). The required sample size was determined using an a priori statistical analysis (G*power version 3.1.9.2, Dusseldorf, Germany). Based on pre- to post-test force data from prior similar studies (Battazza et al. 2023, Da Silva et al. 2015, Ferragut et al. 2024), the mean differences between two dependent means (matched pairs) (f-test: test family) were used to determine that approximately 12 participants were needed to achieve an alpha of 0.05, an effect size of 0.5 (moderate magnitude) and a power of 0.8. There were seven females (mean height: 164.9 ± 9.6 cm; mean body mass: 66.4 ± 12.6 kg) and five males (mean height: 176.3 ± 2.5cm; mean body mass: 86.4 ± 12.2 kg). The average KE 1RM for females was 80.2 ± 20.3 kg (51.0 - 113.4 kg) and 129.5 ± 23.1 kg (102.1-162.0 kg) for males. The average CP 1RM for females was 47.0 ± 14.9 kg (24.9-70.3 kg) and 110.2 ± 24.5 kg (83.9-147.4 kg) for males. Convenience and snowball sampling were used to recruit participants, and posters were placed throughout the Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s campus. The inclusion criteria were apparently (self-reported) healthy, physically active males and females between ages 18-40 with regular (minimum three times a week) resistance training experience for the past 6 months, who regularly consumed (at least once a day) caffeine. The exclusion criteria were people below 18 years old or over 40 years old; people who were not fluent in English to decrease the possibility of confusion with instructions that could impact protocols; people with physical and/or cognitive impairment that would prevent physical activity inclusion; and people currently using other ergogenic supplements.

All participants were informed of the procedures and potential risks before giving their written informed consent to participate. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol for this study (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06714331) was approved by the Interdisciplinary Committee on Ethics in Human Research (ICEHR) of the Memorial University of Newfoundland under protocol number #20241611.

2.2. Experimental Design

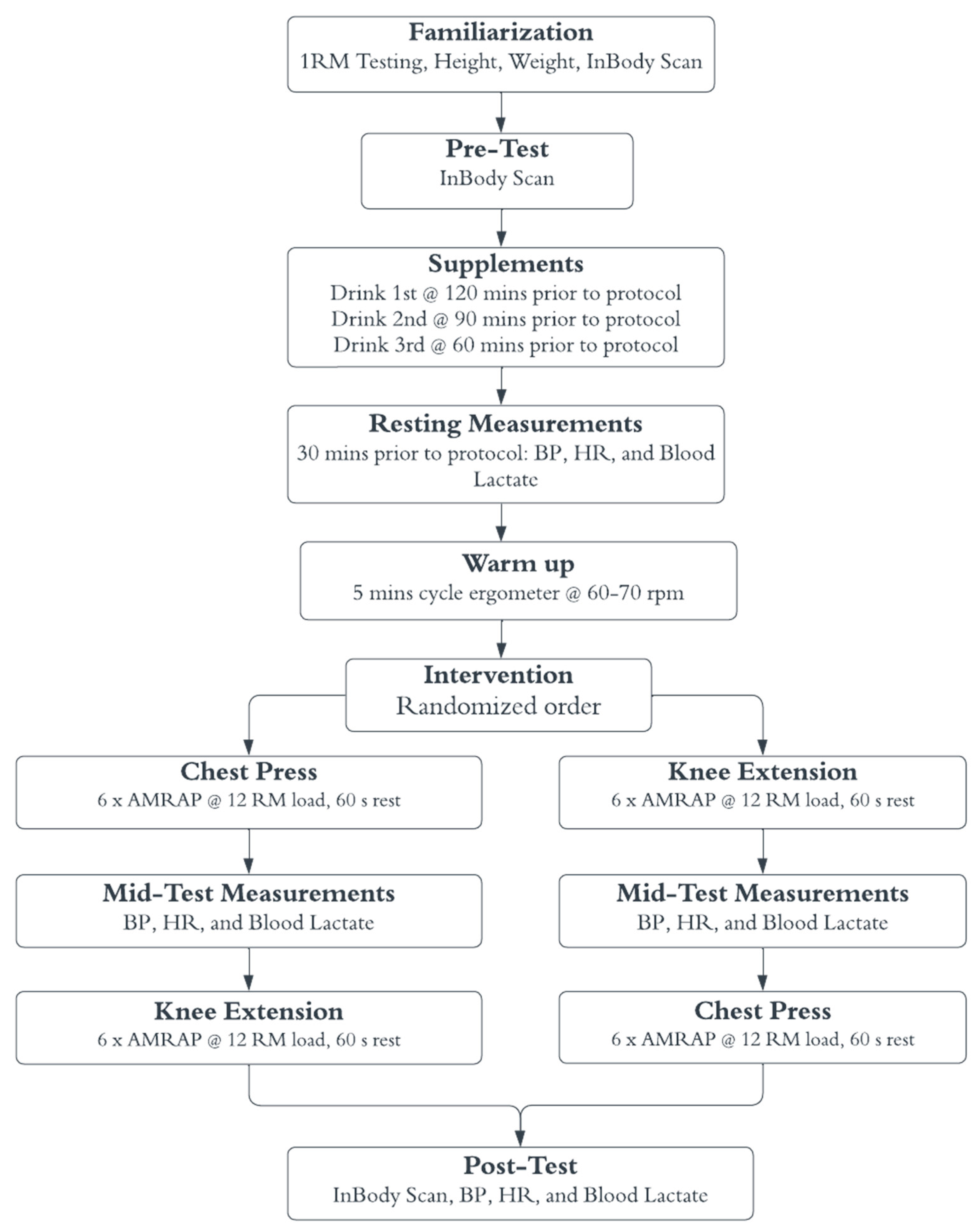

The study employed a randomized (for the supplement conditions), double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study design that examined the effect of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate on performance using an isoinertial knee extension resistance device and Olympic bar bench press. Parameters included number of repetitions to failure with a 12-repetition maximum (12RM) load, rating of perceived exertion (RPE), electromyography (EMG) activity, blood lactate, blood pressure, heart rate, intracellular and extracellular body water, and extracellular body water versus total body water measurements. Participants visited the School of Human Kinetics and Recreation applied neuromuscular research laboratory on four separate occasions to complete familiarization and three supplement conditions: 1) placebo, 2) caffeine, and 3) sodium bicarbonate, in a randomized order (

www.thewordfinder.com/random-letter-generator). Supplements were prepared by a researcher who was not present at the testing protocol. This researcher kept a private record of each participant’s supplement sequence to blind participants and researchers during the testing protocols. During each testing protocol, participants completed CP and KE in a randomized order (

www.thewordfinder.com/random-letter-generator). Testing was performed approximately one week apart at approximately the same time of day to allow for recovery and supplement washout and avoid possible diurnal variations in performance. There were no test timing differences for female participants since research does not show significant effects of the menstrual cycle on acute strength or power performance (Romero-Moraleda, Coso, et al., 2019; Romero-Moraleda, Del Coso, et al., 2019; Lara, Gutiérrez-Hellín, Ruíz-Moreno, et al., 2020; Lara, Gutiérrez-Hellín, García-Bataller, et al., 2020; Umlauff et al., 2021; Miyazaki and Maeda, 2022). Participants were instructed to avoid vigorous exercise and refrain from consuming alcohol, caffeine, and other stimulants 24-h before each experimental trial.

Figure 1 describes the experimental design.

2.3. Familiarization

Participants completed the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PARQ+) (Warburton et al., 2011). Participants’ anthropometric measurements were taken, including height via wall-mounted stadiometer and body composition via InBody machine (InBody Co., Ltd., Seoul, South Korea). Participants were introduced to the 60 beats per minute (bpm) which was used during the testing protocol to maintain a cadence of 1 second for both the concentric and eccentric muscle actions. Participants were also introduced to the RPE scale, a modified Borg CR10 scale ranging from 1-10 with adjectives to help participants identify their exertion level (Borg, 1998). Participants then underwent 1RM testing for KE and CP exercises to determine their maximal load for one repetition. Each participant’s 1RM was used to calculate their 12RM load for the subsequent experiment trials. This calculation was completed using the National Strength and Conditioning Association Training Load Chart, 70% of the 1RM load was used as the estimated 12RM load (National Strength and Conditioning Association, 2012).

2.4. Body Composition and Water Content

InBody analysis was completed prior to supplement consumption and after the testing protocol. Pre- and post-test intracellular water (kg), extracellular water (kg), and extracellular water:total body water (ECW:TBW) ratio data were recorded from a standing (erect) position. Body weight was recorded during the pre-test (GE body weight scale).

2.5. Supplement Protocol

The supplement protocol began 120 minutes before the testing protocol and immediately following the initial InBody analysis. All three supplement conditions followed the same protocol: three opaque bottles containing 300mL of fluid were consumed each session (900mL of fluid total per session). The first 300 ml bottle was consumed two hours (120 minutes) in advance of the testing protocol, the second 300 ml, 90 minutes in advance, and the third 300 ml, 60 minutes in advance. All bottles were consumed as quickly as the participant was able to tolerate. The placebo condition was prepared with water and Mio water flavouring (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, Kraft Heinz) in all three bottles. For the caffeine condition, commercial grade caffeine was used (Atelier Evia, Repentigny, QC, Canada). The dose of caffeine was 0.003g/kg body weight, since this dose is suggested to elicit ergogenic effects without the possible side effects present in higher doses (Grgic, 2021). This caffeine dose was present only in the third of three 300mL bottles (60 minutes in advance), with the first two 300mL bottles containing only placebo. Food-grade sodium bicarbonate was used (Arm & Hammer, Wyoming, USA). The concentration dose of sodium bicarbonate was 0.3g/kg body weight, as is commonly used in the literature to explore ergogenic effects with minimal gastrointestinal side effects (Siegler et al., 2018; Ferragut et al., 2024). The sodium bicarbonate was consumed at 120, 90 and 60 minutes prior to testing to minimize possible gastrointestinal distress. All conditions used Mio water flavouring to mask the supplements.

2.6. RM Testing Protocol

Following supplement consumption, participants performed an aerobic warm up of five minutes of stationary cycling at 60-70 rpm at 1 kilopond resistance on a Velotron ergometer (Velotron RacerMate, Seattle, WA, USA). Participants then did a resistance training warm up of 8-10 repetitions of KE (Cybex isoinertial machine) and CP (Olympic bar) at 50% of the weight (random order allocation). In order to induce significant fatigue (Halperin et al. 2014a, Ramsay et al. 2023) and based on a prior supplement study (Glenn et al. 2017), participants were instructed to complete as many repetitions as possible against a 12RM (approximately 70% of 1RM according to National Strength and Conditioning Association, 2012) load for each set (6 sets for each exercise with the two exercises performed in a randomized order) until they could no longer complete a repetition without assistance or maintain the prescribed cadence. Multiple-set protocols at 70–85% 1RM (≈8–12RM range) are common in resistance-exercise research for assessment of muscular endurance and supplement effects since they stress glycolytic pathways and accumulate fatigue, which are ideal conditions to detect ergogenic benefits (ACSM 2014). The number of repetitions successfully completed during each set was recorded. Based on prior research from this lab and others (Behm et al. 2019, Glenn et al. 2017, Halperin et al. 2014b, Ramsay et al. 2023, Zahiri et al. 2024), the participants had a 60-second rest period between each set which is consistent with muscular endurance training guidelines from American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM 2014). They recommend short rest periods (30–90 s) to maximize metabolic stress and fatigue accumulation. Based on similar interset rest periods (Glenn et al. 2017, Graham et al. 2023, Halperin et al. 2014a,b), following completion of 6 sets of the first exercise (CP or KE), participants rested for 120-seconds before completing the same procedure on the next exercise (CP or KE)

2.7. Electromyography (EMG)

Since caffeine is considered a central nervous system stimulant, EMG was recorded to determine any possible changes in muscle activation (Ribeiro and Sebastião, 2010; Ferragut et al., 2024). EMG electrodes were placed 3 cm apart at the mid-belly of the lateral head of the triceps brachii (mid-point between acromion process to the olecranon process) and 3 cm apart at the mid-belly of the rectus femoris (mid-point between the anterior superior iliac spine and the superior edge of the patella). Ground electrodes were placed on the acromion process for the upper limb and on the fibular head for the lower limb. A thorough skin preparation was executed prior to electrode placement, including shaving and removing dead epithelial cells with an abrasive pad, then cleansing the aforementioned areas with an isopropyl alcohol swab. EMG was collected using a Biopac (Biopac System Inc., DA 100: analog–digital converter MP150WSW; Holliston, Massachusetts) data acquisition system at a sample rate of 2,000 Hz [impedance = 2 MΩ, common mode rejection ratio >110 dB min (50/60 Hz), noise >5 μV]. A bandpass filter (10–500 Hz) was applied prior to digital conversion.

The mean amplitude of the root mean square (RMS) EMG was monitored during the middle 500 ms period of the 1 second concentric phase for both the KE and CP. The mean amplitude of the RMS EMG was normalized to the highest pre-test value and reported as a percentage.

2.8. Blood Lactate, Heart Rate (HR), and Ratings of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

Blood lactate levels were measured with The Edge Blood Lactate Analyzer (Atwood, California, USA) three times, once prior to exercise, once between the two exercises, and immediately after the testing protocol was completed. The participant’s HR (bpm: Polar H10 heart rate monitor with chest and wrist straps Polar Electro, Kempele, Finland), blood pressure (Omron Health Care upper arm cuff), and RPE (modified Borg CR10 scale: Borg, 1998) were collected immediately after the completion of each set The descriptive Borg 1-10 RPE scale was placed in the field of view of participants.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were calculated using SPSS software (Version 28.0, SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL). Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality were conducted for all dependent variables. Significance was defined as p < 0.05. If the assumption of sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse−Geiser correction was employed. A series of repeated measures ANOVAs with sex as a between group factor were conducted with Bonferroni post-hoc tests corrected for multiple comparisons (α-value divided by the number of analyses on the dependent variable) to detect significant main effect differences and identify the significant interactions. The repeated measures ANOVAs included 3 conditions x 2 times (pre- and post-test) for blood lactate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and ECW/TBW. A 3 conditions x 6 sets repeated ANOVA was employed for KE and CP repetitions to failure, RPE, rectus femoris and triceps brachii EMG, while a 3 conditions x 7 times (resting heart rate and 6 sets) was implemented for KE and CP heart rates. Partial Eta-squared (ηp2) values are reported for main effects and overall interactions representing small (0.01≤ ηp2 < 0.06), medium (0.06 ≤ ηp2 < 0.14) and large (ηp2 ≥ 0.14) magnitudes of change (from SPSS-tutorials, 2022). Observed power (OP) was also reported for main effects and interactions.

3. Results

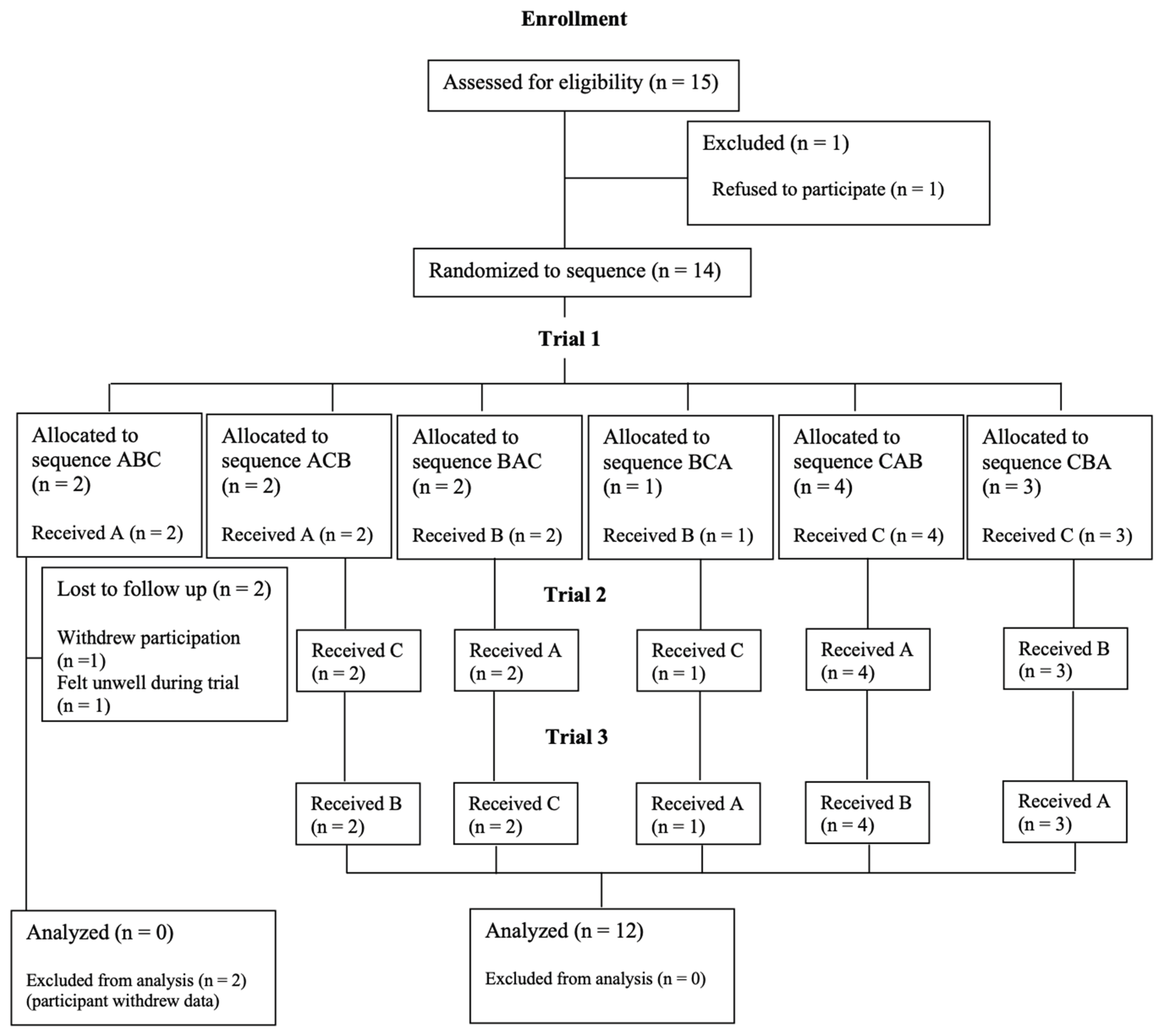

Fifteen individuals fulfilled the study inclusion criteria. However, 12 individuals completed the study. Details of enrollment, exclusion, randomization of supplement conditions, and final number of participants analyzed in this study are provided in

Figure 2.

3.1. Knee Extension (KE) and Chest Press (CP) Repetitions

There were no significant main effects for supplements or any interactions for KE repetitions. A significant main effect for supplements (F(2,20)=4.35, p=0.027, ηp2: 0.303, OP: 0.686) was evident with CP repetitions. Although, the sodium bicarbonate condition exhibited the greatest number of CP repetitions (7.42; 95%CI: 6.8-7.9), the Bonferroni post-hoc analysis indicated non-significant p values of 0.15 and 0.18 when compared to the caffeine (6.7; 95%CI: 6.1-7.3) and control (7.1; 95%CI: 6.4-7.6) conditions, respectively.

3.2. EMG and RPE

There were no significant main effects or interactions evident for triceps brachii EMG or rectus femoris EMG. There were no significant main effects for supplements or any interactions for KE or CP RPE.

3.3. Diastolic Blood Pressure

A main effect for supplement condition (F(2,20)=4.17, p=0.03, ηp2: 0.294, OP: 0.66) indicated that the caffeine condition diastolic blood pressure (79.2 mmHg; 95%CI: 74.6-83.7) was significantly greater than the sodium bicarbonate (72.7 mmHg; 95%CI: 67.5-77.9) and control (74.5 mmHg; 95%CI: 71.7-77.3).

3.4. Extracellular Water/Total Body Water (ECW/TBW)

A significant Time x Sex interaction (F(1,9)=5.46, p=0.04, ηp2: 0.378, OP: 0.55) revealed that both males (0.368-0.371) and females (0.372-0.377) experienced pre- to post-test increases in ECW/TBW. A significant supplements x time interaction (F(2,18)=16.49, p=0.001, ηp2: 0.647, OP: 0.977) showed that all three conditions demonstrated an increase in the ECW/TBW ratio with no significant differences between conditions.

3.5. Main Effects for Time and Sets

Significant main effects for time (pre- to post-test) demonstrated increases in ECW/TBW, blood lactate, and systolic blood pressure (

Table 1). Repetitions generally decreased from the first to the subsequent sets for both KE and CP whereas KE RPE increased from the first to subsequent sets (

Table 2). Heart rate significantly increased when compared to the resting heart rate with a plateau in subsequent sets for KE and only minor but significant differences with CP (

Table 3).

3.6. Sex Differences

Table 4. illustrates significant main effects for sex with lower blood lactates in females, versus higher CP repetitions for females. A significant sets x sex interaction (F

(6,60)=2.66, p=0.023, η

p2: 0.210, OP: 0.826) for CP HR showed that while resting heart rates were similar between the sexes, females experienced lower heart rates during each of the six sets.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the ergogenic effects of an acute dose of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate for KE and CP resistance training. Contrary to our hypothesis, exercise performance as measured by increased repetitions and decreased RPE was not enhanced. The major findings were that 300mL of solution containing caffeine (0.003g/kg solution), 900mL of solution containing sodium bicarbonate (0.3g/kg), or dextrose (control) ingested at 120, 90 and 60 minutes before the testing protocol did not enhance KE repetitions, rectus femoris or triceps brachii activation (EMG), or RPE. There was some evidence for performing a greater number of CP repetitions after ingesting a sodium bicarbonate solution, however, the post-hoc analysis did not achieve significance. Caffeine ingestion did elevate diastolic blood pressure. The interventions in general (main effects for time or sets) increased blood lactate, RPE, ECW/TBW, and systolic blood pressure, and decreased repetitions. Females produced lower blood lactate levels and a greater number of CP repetitions. However, with only 7 female and 5 male participants, the analysis of sex differences should be considered exploratory.

4.1. Knee Extension (KE) and Chest Press (CP) Repetitions

We found that caffeine supplementation did not enhance KE or CP muscle endurance as measured by the number of repetitions successfully performed. Literature on the acute ergogenic effects of caffeine for increased repetitions is inconsistent, especially when comparing the upper and lower body. Contrary to our results, prior research supports acute and chronic training ergogenic effects of caffeine on upper body resistance exercise/training (Grgic et al., 2019; Grgic, 2021). A recent meta-analysis of the literature concluded that there is a significant increase in the number of CP repetitions performed until failure in those who ingested caffeine compared to placebo control (Ferreira et al., 2021). Regarding lower body performance, the literature is contradictory, with most studies reporting increased repetitions during caffeine supplementation (Grgic et al., 2019; Grgic et al., 2020; Ferreira et al., 2021; Grgic, 2021). However, these ergogenic results are most commonly reported in squat and leg press exercises (Grgic, 2021). In those studies that have also tested knee extension, significant increases in repetitions compared to placebo control have been found with doses of 0.005g/kg, while no improvements are reported at a 0.002g/kg dose (Grgic et al., 2019; Grgic, 2021).

This suggests that the lack of significant increases in our results may be due to our caffeine dosage of 0.003g/kg. Prior studies have reported ergogenic effects with as low as 0.002g/kg with specific lower body exercises (i.e., leg press and squats). The International Society of Sports Nutrition recommends a minimum dosage of 0.002g/kg (Guest et al. 2021). Doses of 0.004g/kg to 0.006g/kg are reported for ergogenic effects on upper body performance and 0.005g/kg to 0.006g/kg for significance in knee extension exercise (Grgic, 2021). Thus, our findings agree with much of the current literature that there is no statistically significant difference in upper and lower body endurance with caffeine doses below 0.004g/kg (Ferreira et al., 2021).

In accordance with our findings, many previous studies show no significant effect of sodium bicarbonate on the number of CP (Duncan et al., 2014; Fontanella et al., 2020) or KE repetitions (Carr et al., 2013; Siegler et al., 2018). However, sodium bicarbonate has contributed to a significant increase in the time to fatigue in cycling to exhaustion tests (Bouissou et al., 1988; Ferreira et al., 2019). This contrast can likely be attributed to differences in exercise duration and intensity. Shorter, high intensity exhaustion tests rely on relatively more energy from anaerobic metabolism (greater accumulation of H+) compared to traditional resistance training; facilitating earlier fatigue (Ferreira et al., 2019). It is proposed that the sodium bicarbonate ingestion can inhibit pH decrease in the muscle and increase the removal rate of H+ (Ferreira et al., 2019). As a result of the brief duration of the CP and KE sets (estimated 12 RM from 70% 1 RM) with the 60 second recovery between sets, the accumulation of H+ ions (acidosis) would not be as high as some other high intensity cycling or running protocols (Ferreira et al., 2019) and thus the role of sodium bicarbonate as a buffer (Hadzic et al., 2019) was not as consequential in the present study.

Prior studies have shown a significant increase in muscular endurance as a result of placebo effect (Pollo et al., 2008; Duncan et al., 2009). Further, in a recent study, a significant increase in upper body strength was only found when supplementation was compared to no-placebo control versus placebo control (Grgic et al., 2020). It is possible that if participants in this study believed they were consuming caffeine during the control session, they might perform better, thus skewing their baseline measures. Researchers have suggested asking participants to indicate which trial they believe to be caffeine, to distinguish between caffeine and placebo effects (Grgic et al., 2019). This was not done in this study and should be considered as a methodological limitation.

4.2. Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

Although our finding that caffeine had no effect on RPE disproves our hypothesis, this finding aligns with most of the literature that also reports no reduction in RPE (Green et al., 2007; Hudson et al., 2008; Ribeiro and Sebastião, 2010; Da Silva et al., 2015; Grgic et al., 2019; Grgic et al., 2020; Ferreira et al., 2021; Pakulak et al., 2022; Ferragut et al., 2024). Caffeine is a popular ergogenic aid for aerobic exercises, where it has been reported to provide a 5% decrease in RPE, but few resistance training studies have found similar results (Doherty and Smith, 2005). In many of these aerobic studies, RPE is lower during the prolonged activity, but is unchanged at the end of the exercise (Birnbaum and Herbst, 2004; Doherty and Smith, 2005; Killen et al., 2013). It is possible that since RPE measurements in this study occurred at the end of each set (i.e., following the activity) instead of during the sets, no reduction in effort was perceived (Grgic et al., 2019).

No significant effect of sodium bicarbonate on RPE was apparent in our protocol of acute bouts of CP and KE resistance training; this concurs with the current literature (Duncan et al., 2014; Fontanella et al., 2020; Battazza et al., 2023). In contrast, Marriott et al. (2015) found that sodium bicarbonate significantly reduced RPE in a Yo-Yo intermittent recovery test (20m running test at progressively increasing speeds), after an upper body workout. The Yo-Yo test, described as high-intensity intermittent exercise, produced greater heart rates than our resistance training protocol, once again identifying intensity as a factor that differs between the present study and studies that found ergogenic effects for sodium bicarbonate (Marriott et al., 2015).

4.3. Electromyography (EMG)

We found no effect of either caffeine or sodium bicarbonate on EMG amplitude in either CP or KE exercises, which aligns with a few studies that have implemented short-term, high-intensity exercise or isometric (Greer et al., 2006; Siegler et al., 2018; Franco-Alvarenga et al., 2019). While no apparent studies have investigated the effect of caffeine on EMG during CP exercises, Trevino et al., (2015) found no effect on biceps brachii EMG amplitude during isometric elbow flexion.

4.4. Blood Pressure

Both resistance training and caffeine have been shown to lead to increased blood pressure (Grgic et al., 2019). This finding is supported by our study and is an important note of caution for individuals with high blood pressure. Caffeine stimulation of the central nervous system could increase blood pressure by inhibiting adenosine receptors, leading to increased neurotransmitter release, such as dopamine, acetylcholine, epinephrine, and norepinephrine (Ferreira et al., 2021; Mor et al., 2024; Kaçoğlu et al., 2024).

4.5. Extracellular Water/Total Body Water (ECW/TBW)

ECW/TBW was elevated after the resistance training intervention for all conditions. This response is attributed to physiological responses to stress, such as the release of stress hormones like cortisol and inflammatory responses, which can promote water retention. As muscles enlarge in response to resistance exercise, they require greater intracellular water, which is initiated by an increase in extracellular water (Ribeiro et al., 2014).

4.6. Sex differences

The significant sex differences seen in this study were lower blood lactate levels, higher CP repetitions, and lower working heart rates in females. Lower blood lactate levels in females have been observed in a variety of both aerobic and resistance training studies (Szivak et al., 2013; Holfelder et al., 2013; Mochizuki et al., 2022). In a study of high intensity (75% of 1RM), short rest (1 minute) resistance training, males demonstrated significantly higher blood lactate levels. Further, lactate has a strong positive correlation with total work done in kilograms (Szivak et al., 2013), which is in accord with the higher levels of total work with males in the present study.

Regarding higher repetitions of CP in females, in tests of isometric endurance females have demonstrated less fatigability than males (Hunter, 2014). However, a narrative review of sex differences reported that sex differences in muscle endurance during non-isometric programs are mixed (Nuzzo, 2023). Specifically, the review cited that evidence of sex differences in muscle fatigability measured through repetitions to failure at relative loads, as in our study design, is lacking (Nuzzo, 2023). It is important to note that as seen in our study, sex differences in fatigability do appear to be task specific and may be influenced by factors such as the muscle group assessed (Hunter, 2014; Nuzzo, 2023).

Females tend to have higher resting heart rates (Genovesi et al., 2007), however in the present study we found no difference in resting heart rate between sexes. In fact, females in our study actually had lower working heart rates than males. Two non-sex difference related mechanisms behind lower heart rates are lower heart rates in more highly trained individuals (inclusion criteria of at least 6 months of resistance training in the present study), and lower heart rates due to a lower relative workload (Genovesi et al., 2007; Castinheiras-Neto et al., 2010).

Sex differences in both CP repetitions and heart rate could be theoretically related to the relative load determined in this study through the 1RM test. Resistance training experience level has been suggested in some literature to impact the accuracy of 1RM testing based on individuals producing greater 1RM results with more testing sessions (Ritti-Dias et al., 2011). There is also greater variability in the maximum repetitions performed at any percentage-based training load with lower percentages of 1RM load (Nuzzo, 2023). However, a recent systematic review has found that 1RM testing generally has between good and excellent test-retest reliability regardless of resistance training experience and sex (Grgic et al., 2020).

An important consideration to make when interpreting our results is sample size. A greater sample size could have strengthened statistical power. We did compute statistical power for main effects but with only 7 females and 5 males, the statistical sex interaction findings should be considered exploratory. It was difficult to attract participants to volunteer for a familiarization session and three – 3-hour experimental sessions, which included the possibility of gastrointestinal distress. Additionally, participant self-reporting may have affected results if participants did not fully follow pre-test instructions (e.g., no vigorous activity or alcohol 24 hours before testing). Furthermore, participants were not required to change their dietary habits prior to lab visits; however, research regarding supplementation on a fed versus fasted state has elucidated that a 0.003g/kg dose is only ergogenic in a fasted state (Grgic et al., 2019). Finally, since we asked participants to do as many repetitions as possible for each set, it is possible they rated their RPE immediately after each set as corresponding with their level of effort.

Despite clearly defining the inclusion criteria with participants regularly performing resistance training (minimum three times a week) for the past 6 months is still vague. This description can include those who may have had years of extensive training experience, while also including individuals who may have only begun training 6 months ago affecting the homogeneity of the sample. For example, the range within and between male CP 1RM (n = 5, Range = 185-325 lbs) and female CP 1RM was considerable (n = 8, Range = 55-155 lbs).

Our study, however, had numerous strengths, including its double-blind, crossover, placebo-controlled design. Furthermore, the inclusion of a washout period between testing protocols and a 24-hour abstinence from stimulants ensured that our results accurately reflect the effects of an acute dosage of each supplement with no interactions. Lastly, this study expands the literature on the sex-based differences in resistance training performance following supplement ingestion.

5. Conclusions

This study observed no significant ergogenic effects for muscle endurance, EMG, or RPE during KE and CP exercises from caffeine at a 0.003g/kg dosage or sodium bicarbonate supplementation at a 0.3g/kg dosage when ingested 60-120 minutes prior to exercise. While sodium bicarbonate supplementation seemed to increase CP repetitions, these interaction findings were non-significant. This study adds to the currently contradictory supplementation literature by concluding that 0.003g/kg may be too minimal a caffeine dosage to elicit performance improvements during resistance training. Further research should include more participants, investigate sex differences further, and focus solely on upper or lower body protocols to determine ergogenic dosages for each.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.B., C.P.M., K.S., M.S., M.W., D.G.B.; funding acquisition, D.G.B.; investigation/data collection/analysis, C.B., C.P.M., K.S., M.S., M.W., E.L., A.S.; methodology, C.B., C.P.M., K.S., M.S., M.W., D.G.B.; project administration, C.B., C.P.M., K.S., M.S., M.W., D.G.B.; resources, D.G.B.; supervision, D.G.B.; writing—original draft, C.B., C.P.M., K.S., M.S., M.W., D.G.B.; writing—review and editing, C.B., C.P.M., K.S., M.S., M.W. E.L., A.S., R.Z., K.M.H., D.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a grant for David G. Behm from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (RGPIN-2023-05861).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Committee for Ethics in Human Research (ICEHR) at Memorial University of Newfoundland under protocol number #20241611.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank ReachSci Society for their support and assistance. This work was conducted as part of the Mini-PhD Programme 2024: Food Science & Nutrition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- American College of Sports Medicine. (2014). ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. (Vol. 9th Edition). Lippincott, Wiliams and Wilkins.

- Antonio, J., Newmire, D.E., Stout, J.R., Antonio, B., Gibbons, M., Lowery, L.M., Harper, J., Willoughby, D., Evans, C., Anderson, D., Goldstein, E., Rojas, J., Monsalves-Álvarez, M., Forbes, S.C., Gomez Lopez, J., Ziegenfuss, T., Moulding, B.D., Candow, D., Sagner, M. and Arent, S.M. 2024. Common questions and misconceptions about caffeine supplementation: what does the scientific evidence really show? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 21(1), p.2323919.

- Battazza, R.A., Kalytczak,Marcelo M., Leite,Carine D. F. C., Rica,Roberta L., Lamolha,Marco A., Junior,Antonio H. Lancha, Maia,Adriano F., Bergamin,Marco, Baker,Julien S., Politti,Fabiano and and Bocalini, D.S. 2023. Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate Supplementation on Muscle Performance and Muscle Damage: A Double Blind, Randomized Crossover Study. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 20(5), pp.689–705.

- Behm, D.G. 1995. Neuromuscular Implications and Applications of Resistance Training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 9(4), p.264.

- Behm D.G., Colwell E.M., Power G.M.J., Ahmadi H., Behm A.S.M., Bishop A., Murphy C.

- Pike J., McAssey B., Fraser K., Kearley S., Ryan M. 2019. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Improves Fatigue Performance of the Treated and Contralateral Knee Extensors. European Journal of Applied Physiology 119:2745–2755. [CrossRef]

- Bilondi, H. T., Valipour, H., Khoshro, S., Jamilian, P., Ostadrahimi, A., and Zarezadeh, M. 2024. The effect of caffeine supplementation on muscular strength and endurance: A meta-analysis of meta-analyses. Heliyon. 10(15), e35025. [CrossRef]

- Birnbaum, L.J. and Herbst, J.D. 2004. Physiologic Effects of Caffeine on Crosscountry Runners. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 18(3), p.463.

- Borg, G. 1998. Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign, IL, US: Human Kinetics.

- Bouissou, P., Defer, G., Guezennec, C.Y., Estrade, P.Y. and Serrurier, B. 1988. Metabolic and blood catecholamine responses to exercise during alkalosis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 20(3), p.228.

- Carr, B.M., Webster, M.J., Boyd, J.C., Hudson, G.M. and Scheett, T.P. 2013. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation improves hypertrophy-type resistance exercise performance. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 113(3), pp.743–752.

- Castinheiras-Neto, A.G., Costa-Filho, I.R. da and Farinatti, P.T.V. 2010. Cardiovascular responses to resistance exercise are affected by workload and intervals between sets. Arquivos Brasileiros de Cardiologia. 95, pp.493–501.

- Cholewa, J.M., Rossi, F.E., MacDonald, C., Hewins, A., Gallo, S., Micenski, A., Norton, L. and Campbell, B.I. 2018. The Effects of Moderate- Versus High-Load Resistance Training on Muscle Growth, Body Composition, and Performance in Collegiate Women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 32(6), pp.1511–1524.

- Da Silva, V.L., Messias, F.R., Zanchi, N.E., Gerlinger-Romero, F., Duncan, M.J. and Guimarães-Ferreira, L. 2015. Effects of acute caffeine ingestion on resistance training performance and perceptual responses during repeated sets to failure. The Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness. 55(5), pp.383–389.

- Del Coso, J., Muñoz, G. and Muñoz-Guerra, J. 2011. Prevalence of caffeine use in elite athletes following its removal from the World Anti-Doping Agency list of banned substances. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 36(4), pp.555–561.

- Doherty, M. and Smith, P.M. 2005. Effects of caffeine ingestion on rating of perceived exertion during and after exercise: a meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports. 15(2), pp.69–78.

- Domaszewski, P., Pakosz, P., Konieczny, M., Baczkowicz, D., and Sadowska-Krepa, E. 2021.

- Caffeine-induced effects on human skeletal muscle contraction time and maximal displacement measured by tensiomyography. Nutrients. 13(3). [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J., Lyons, M. and Hankey, J. 2009. Placebo effects of caffeine on short-term resistance exercise to failure. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 4(2), pp.244–253.

- Duncan, M.J., Weldon, A. and Price, M.J. 2014. The Effect of Sodium Bicarbonate Ingestion on Back Squat and Bench Press Exercise to Failure. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 28(5), p.1358.

- Ferragut, C., Gonzalo-Encabo, P., López-Samanes, Á., Valadés, D. and Pérez-López, A. 2024. Effect of Acute Sodium Bicarbonate and Caffeine Coingestion on Repeated-Sprint Performance in Recreationally Trained Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Trial. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 19(5), pp.427–434.

- Ferreira, L.H.B., Smolarek, A.C., Chilibeck, P.D., Barros, M.P., McAnulty, S.R., Schoenfeld, B.J., Zandona, B.A. and Souza-Junior, T.P. 2019. High doses of sodium bicarbonate increase lactate levels and delay exhaustion in a cycling performance test. Nutrition. 60, pp.94–99.

- Ferreira, T.T., Da Silva, J.V.F. and Bueno, N.B. 2021. Effects of caffeine supplementation on muscle endurance, maximum strength, and perceived exertion in adults submitted to strength training: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 61(15), pp.2587–2600.

- Ferreira, L. H. B., Forbes, S. C., Barros, M. P., Smolarek, A. C., Enes, A., Lancha-Junior, A. H.,.

- Martins, G. L., and Souza-Junior, T. P. 2022. High doses of caffeine increase muscle strength and calcium release in the plasma of recreationally trained men. Nutrients 14(22), 4921. [CrossRef]

- Fontanella, L.R., Azara, C., Scudese, E., Silva, D. de O., Nogueira, C.J., Costa, M.S.E. and Senna, G.W. 2020. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation in resistance exercise performance, perceived exertion and blood lactate concentration. Motriz: Revista de Educação Física. 26, p.e10200215.

- Franco-Alvarenga, P.E., Brietzke, C., Canestri, R., Goethel, M.F., Viana, B.F. and Pires, F.O. 2019. Caffeine Increased Muscle Endurance Performance Despite Reduced Cortical Activation and Unchanged Neuromuscular Efficiency and Corticomuscular Coherence. Nutrients. 11(10), p.2471.

- Genovesi, S., Zaccaria, D., Rossi, E., Valsecchi, M.G., Stella, A. and Stramba-Badiale, M. 2007. Effects of exercise training on heart rate and QT interval in healthy young individuals: are there gender differences? EP Europace. 9(1), pp.55–60.

- Glenn J.M, Gray M., Wethington L.N., Stone M.S., Stewart R.W., and Moyen N.E. 2017.

- Acute citrulline malate supplementation improves upper- and lower-body submaximal weightlifting exercise performance in resistance-trained females. European Journal of Nutrition 56, 775–784.

- Graham A.P., Gardner H., Chaabene H., Talpey S., Alizadeh S., Behm D.G. 2023. Maximal and.

- Submaximal Intensity Isometric Knee Extensions Induce an Underestimation of Time Estimates with both Younger and Older Adults: A Randomized Crossover Trial”. Journal of Sport Science and Medicine 22, 405-415.

- Green, J.M., Wickwire, P.J., McLester, J.R., Gendle, S., Hudson, G., Pritchett, R.C. and Laurent, C.M. 2007. Effects of caffeine on repetitions to failure and ratings of perceived exertion during resistance training. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 2(3), pp.250–259.

- Greer, F., Morales, J. and Coles, M. 2006. Wingate performance and surface EMG frequency variables are not affected by caffeine ingestion. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism 31(5), pp.597–603.

- Grgic, J. 2021. Effects of Caffeine on Resistance Exercise: A Review of Recent Research. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 51(11), pp.2281–2298.

- Grgic, J., Pedisic, Z., Saunders, B., Artioli, G. G., Schoenfeld, B. J., McKenna, M. J., Bishop, D.

- J., Kreider, R. B., Stout, J. R., Kalman, D. S., Arent, S. M., VanDusseldorp, T. A., Lopez, H. L., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Burke, L. M., Antonio, J., and Campbell, B. I. 2021a. International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: sodium bicarbonate and exercise performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18(1), 61. [CrossRef]

- Grgic, J., Grgic, I., Del Coso, J., Schoenfeld, B.J. and Pedisic, Z. 2021b. Effects of sodium bicarbonate supplementation on exercise performance: an umbrella review. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18(1), p.71.

- Grgic, J., Lazinica, B., Schoenfeld, B.J. and Pedisic, Z. 2020. Test–Retest Reliability of the One-Repetition Maximum (1RM) Strength Assessment: a Systematic Review. Sports Medicine - Open. 6, p.31.

- Grgic, J., Mikulic, P., Schoenfeld, B.J., Bishop, D.J. and Pedisic, Z. 2019. The Influence of Caffeine Supplementation on Resistance Exercise: A Review. Sports Medicine (Auckland, N.Z.). 49(1), pp.17–30.

- Guest, N.S., VanDusseldorp, T.A., Nelson, M.T., Grgic, J., Schoenfeld, B.J., Jenkins, N.D.M., Arent, S.M., Antonio, J., Stout, J.R., Trexler, E.T., Smith-Ryan, A.E., Goldstein, E.R., Kalman, D.S. and Campbell, B.I. 2021. International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and exercise performance. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 18(1), p.1.

- Hadzic, M., Eckstein, M.L. and Schugardt, M. 2019. The Impact of Sodium Bicarbonate on Performance in Response to Exercise Duration in Athletes: A Systematic Review. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 18(2), pp.271–281.

- Halperin I., Aboodarda S.J., Basset F.A., Behm D.G. 2014a. Knowledge of repetitions range.

- affects force production in trained females. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 13: 736-741.

- Halperin I., Copithorne D., Behm D.G. 2014b. Unilateral isometric muscle fatigue decreases.

- force production and activation of contralateral knee extensors but not elbow flexors. Applied Physiology Nutrition and Metabolism 39: 1-7.

- Holfelder, B., Brown, N. and Bubeck, D. 2013. The Influence of Sex, Stroke and Distance on the Lactate Characteristics in High Performance Swimming. PLOS ONE. 8(10), p.e77185.

- Hudson, G.M., Green, J.M., Bishop, P.A. and Richardson, M.T. 2008. Effects of caffeine and aspirin on light resistance training performance, perceived exertion, and pain perception. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 22(6), pp.1950–1957.

- Hunter, S.K. 2014. Sex differences in human fatigability: mechanisms and insight to physiological responses. Acta Physiologica. 210(4), pp.768–789.

- Kaçoğlu, C., Kirkaya, İ., Ceylan, H.İ., De Assis, G.G., Almeida-Neto, P., Bayrakdaroğlu, S., Chaves Oliveira, C., Özkan, A. and Nikolaidis, P.T. 2024. Pre-Exercise Caffeine and Sodium Bicarbonate: Their Effects on Isometric Mid-Thigh Pull Performance in a Crossover, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Sports. 12(8), p.206.

- Kilding, A.E., Overton, C. and Gleave, J. 2012. Effects of caffeine, sodium bicarbonate, and their combined ingestion on high-intensity cycling performance. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism. 22(3), pp.175–183.

- Killen, L.G., Green, J.M., O’Neal, E.K., McIntosh, J.R., Hornsby, J. and Coates, T.E. 2013. Effects of caffeine on session ratings of perceived exertion. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 113(3), pp.721–727.

- Lara, B., Gutiérrez-Hellín, J., García-Bataller, A., Rodríguez-Fernández, P., Romero-Moraleda, B. and Del Coso, J. 2020. Ergogenic effects of caffeine on peak aerobic cycling power during the menstrual cycle. European Journal of Nutrition. 59(6), pp.2525–2534.

- Lara, B., Gutiérrez-Hellín, J., Ruíz-Moreno, C., Romero-Moraleda, B. and Del Coso, J. 2020. Acute caffeine intake increases performance in the 15-s Wingate test during the menstrual cycle. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 86(4), pp.745–752.

- Lew, L.A., Williams, J.S., Stone, J.C., Au, A.K.W., Pyke, K.E. and MacDonald, M.J. 2022. Examination of Sex-Specific Participant Inclusion in Exercise Physiology Endothelial Function Research: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. 4.

- Marriott, M., Krustrup, P. and Mohr, M. 2015. Ergogenic effects of caffeine and sodium bicarbonate supplementation on intermittent exercise performance preceded by intense arm cranking exercise. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition. 12(1), p.13.

- Martins, G.L., Guilherme, J.P.L.F., Ferreira, L.H.B., de Souza-Junior, T.P. and Lancha, A.H. 2020. Caffeine and Exercise Performance: Possible Directions for Definitive Findings. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. 2, p.574854.

- McNaughton, L.R., Gough, L., Deb, S., Bentley, D. and Sparks, S.A. 2016. Recent Developments in the Use of Sodium Bicarbonate as an Ergogenic Aid. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 15(4), pp.233–244.

- Miyazaki, M. and Maeda, S. 2022. Changes in hamstring flexibility and muscle strength during the menstrual cycle in healthy young females. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 34(2), pp.92–98.

- Mochizuki, Y., Saito, M., Homma, H., Inoguchi, T., Naito, T., Sakamaki-Sunaga, M. and Kikuchi, N. 2022. Sex differences in lifting velocity and blood lactate concentration during resistance exercise using different rest intervals.

- Montalvo-Alonso, J.J., Ferragut, C., Del Val-Manzano, M., Valadés, D., Roberts, J. and Pérez-López, A. 2024. Sex Differences in the Ergogenic Response of Acute Caffeine Intake on Muscular Strength, Power and Endurance Performance in Resistance-Trained Individuals: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 16(11), p.1760.

- Mor, A., Acar, K., Alexe, D.I., Mor, H., Abdioğlu, M., Man, M.C., Karakaș, F., Waer, F.B., Yılmaz, A.K. and Alexe, C.I. 2024. Moderate-dose caffeine enhances anaerobic performance without altering hydration status. Frontiers in Nutrition. 11.

- National Strength and Conditioning Association 2012. NSCA Tools and Resources. NSCA Tools and Resources. [Online]. [Accessed 22 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.nsca.com/education/tools-and-resources/.

- Nuzzo, J.L. 2023. Narrative Review of Sex Differences in Muscle Strength, Endurance, Activation, Size, Fiber Type, and Strength Training Participation Rates, Preferences, Motivations, Injuries, and Neuromuscular Adaptations. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 37(2), p.494.

- Pakulak, A., Candow,Darren G., Totosy de Zepetnek,Julia, Forbes,Scott C. and and Basta, D. 2022. Effects of Creatine and Caffeine Supplementation During Resistance Training on Body Composition, Strength, Endurance, Rating of Perceived Exertion and Fatigue in Trained Young Adults. Journal of Dietary Supplements. 19(5), pp.587–602.

- Pollo, A., Carlino, E. and Benedetti, F. 2008. The top-down influence of ergogenic placebos on muscle work and fatigue. European Journal of Neuroscience. 28(2), pp.379–388.

- Ramsay E., Alizadeh S., Summers D., Hodder A., Behm D.G. 2023. The Effect of a Mental Task.

- versus Unilateral Physical Fatigue on Non-local Muscle Fatigue in Recreationally Active Young Adults. Journal of Sport Sciences and Medicine 22, 548-557.

- DOI:. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S., Avelar, A., Schoenfeld, B.J., Ritti Dias, R.M., Altimari, L.R. and Cyrino, E.S. 2014. Resistance training promotes increase in intracellular hydration in men and women. European Journal of Sport Science. 14(6), pp.578–585.

- Ribeiro, J.A. and Sebastião, A.M. 2010. Caffeine and adenosine. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease: JAD. 20 Suppl 1, pp.S3-15.

- Ritti-Dias, R.M., Avelar, A., Salvador, E.P. and Cyrino, E.S. 2011. Influence of Previous Experience on Resistance Training on Reliability of One-Repetition Maximum Test. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 25(5), p.1418.

- Romero-Moraleda, B., Coso, J.D., Gutiérrez-Hellín, J., Ruiz-Moreno, C., Grgic, J. and Lara, B. 2019. The Influence of the Menstrual Cycle on Muscle Strength and Power Performance. Journal of Human Kinetics. 68(1), pp.123–133.

- Romero-Moraleda, B., Del Coso, J., Gutiérrez-Hellín, J. and Lara, B. 2019. The Effect of Caffeine on the Velocity of Half-Squat Exercise during the Menstrual Cycle: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients. 11(11), p.2662.

- Sabol, F., Grgic, J. and Mikulic, P. 2019. The Effects of 3 Different Doses of Caffeine on Jumping and Throwing Performance: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Crossover Study. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance. 14(9), pp.1170–1177.

- Saunders, B., Oliveira, L.F. de, Dolan, E., Durkalec-Michalski, K., McNaughton, L., Artioli, G.G. and Swinton, P.A. 2022. Sodium bicarbonate supplementation and the female athlete: A brief commentary with small scale systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Sport Science. 22(5), pp.745–754.

- Schoffstall, J.E., Branch, J.D., Leutholtz, B.C. and Swain, D.P. 2001. Effects of Dehydration and Rehydration on the One-Repetition Maximum Bench Press of Weight-Trained Males. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 15(1), pp.102–108.

- Serra-Prat, M., Lorenzo, I., Papiol, M., Palomera, E., Bartolomé, M., Pleguezuelos, E. and Burdoy, E. 2020. Intracellular Water Content in Lean Mass as an Indicator of Muscle Quality in an Older Obese Population. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 9(5), p.1580.

- Siegler, J.C., Marshall, P.W.M., Finn, H., Cross, R. and Mudie, K. 2018. Acute attenuation of fatigue after sodium bicarbonate supplementation does not manifest into greater training adaptations after 10-weeks of resistance training exercise. PloS One. 13(5), p.e0196677.

- Silva, A.M., Júdice, P.B., Matias, C.N., Santos, D.A., Magalhães, J.P., St-Onge, M.-P., Gonçalves, E.M., Armada-da-Silva, P. and Sardinha, L.B. 2013. Total body water and its compartments are not affected by ingesting a moderate dose of caffeine in healthy young adult males. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism. 38(6), pp.626–632.

- Siquier-Coll, J., Delgado-García, G., Soto-Méndez, F., Liñán-González, A., García, R. and González-Fernández, F.T. 2023. The Effect of Caffeine Supplementation on Female Volleyball Players’ Performance and Wellness during a Regular Training Week. Nutrients. 16(1), p.29.

- Szivak, T.K., Hooper, D.R., Dunn-Lewis, C., Comstock, B.A., Kupchak, B.R., Apicella, J.M., Saenz, C., Maresh, C.M., Denegar, C.R. and Kraemer, W.J. 2013. Adrenal Cortical Responses to High-Intensity, Short Rest, Resistance Exercise in Men and Women. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 27(3), p.748.

- Trevino, M.A., Coburn, J.W., Brown, L.E., Judelson, D.A. and Malek, M.H. 2015. Acute Effects of Caffeine on Strength and Muscle Activation of the Elbow Flexors. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 29(2), p.513.

- Umlauff, L., Weil, P., Zimmer, P., Hackney, A.C., Bloch, W. and Schumann, M. 2021. Oral Contraceptives Do Not Affect Physiological Responses to Strength Exercise. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 35(4), pp.894–901.

- Warburton, D.E.R., Jamnik, V.K., Bredin, S.S.D. and Gledhill, N. 2011. The Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire for Everyone (PAR-Q+) and Electronic Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination (ePARmed-X+). The Health & Fitness Journal of Canada. 4(2), pp.3–17.

- Zahiri A., Goudini R., Alizadeh S., Daneshjoo A., Mahmoud M.M.I., Konrad A., Granacher U., Behm D.G. 2024. The duration of non-local muscle fatigue effects. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine 23, 425-435 http://www.jssm.org. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).