Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

26 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Sample

2.1.2. Experimental Supplies and Instruments

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Extraction of Intestinal Bacteria from Penaeus Monodon

2.2.2. Extraction of Bacteria from Water Samples of Mixed Culture Pond

2.2.3. Extraction, PCR Amplification and Purification of Total DNA of Thesample and Sequence Determination

2.2.4. Water Quality Index Testing

2.2.5. Data Processing

3. Results

3.1. Water Quality Index Data

| Sampling Phase | pH | NH3-N (mg·L−1) |

NO2--N (mg·L−1) |

NO3--N (mg·L−1) |

PO43--P (mg·L−1) |

TN (mg·L−1) | TP (mg·L−1) |

| SH1 | 8.1±0.02 | 0.11±0.01 | 0.01±0.02 | 0.51±0.02 | 0.05±0.012 | 0.71±0.02 | 0.08±0.05 |

| SH2 | 7.8±0.01 | 0.25±0.01 | 0.02±0.02 | 0.75±0.03 | 0.11±0.02 | 1.34±0.02 | 0.15±0.02 |

| SH3 | 7.6±0.04 | 0.33±0.02 | 0.02±0.01 | 1.18±0.01 | 0.27±0.06 | 1.53±0.02 | 0.31±0.03 |

| SH4 | 7.5±0.02 | 0.51±0.02 | 0.04±0.02 | 1.22±0.02 | 0.34±0.07 | 1.86±0.02 | 0.36±0.02 |

3.2. High-Throughput Sequencing Data

3.3. OTU Cluster Analysis

3.3.1. OTU Clustering and Annotation Analysis

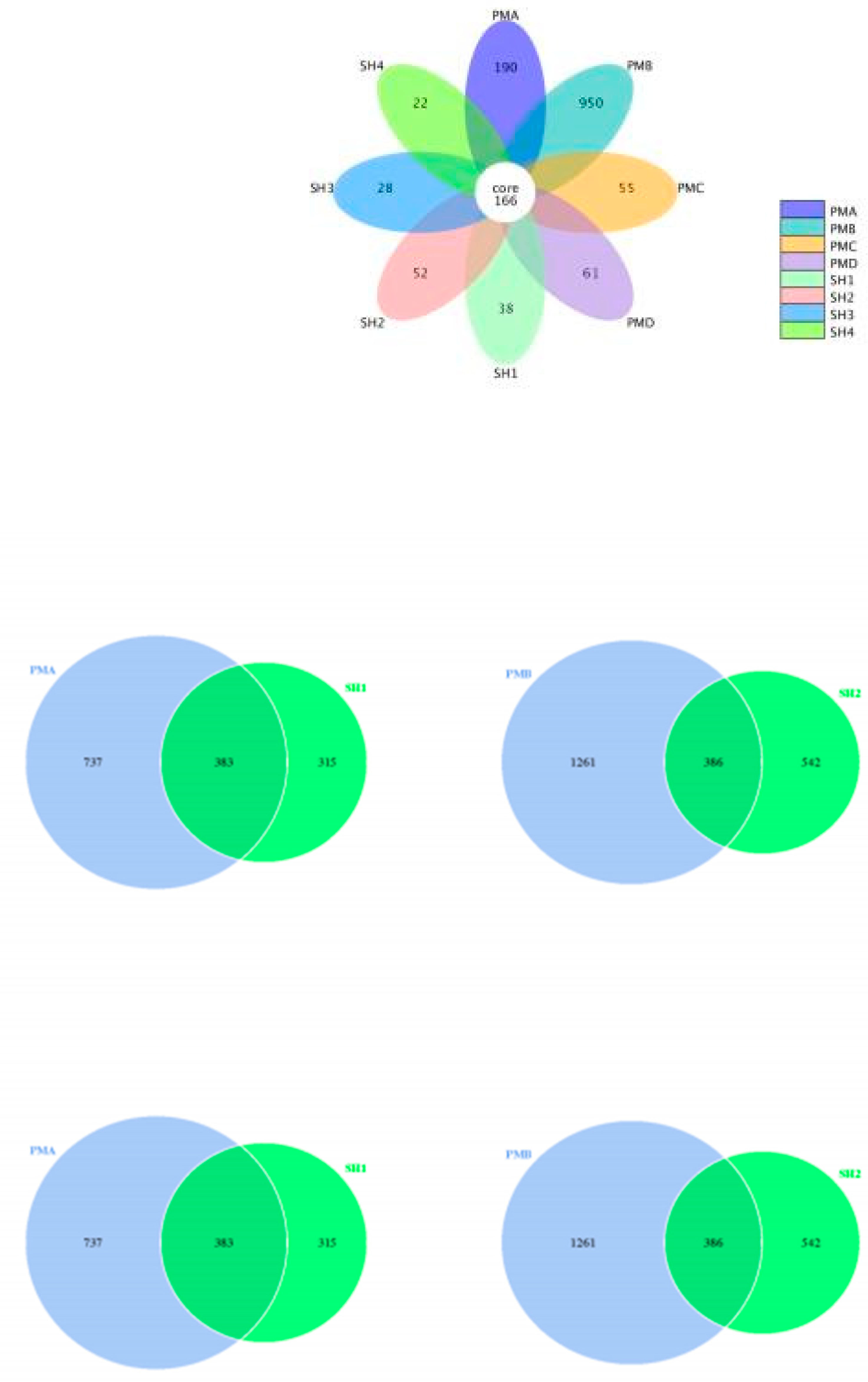

3.3.2. Analysis of OTU Petal Diagram and Wayne Diagram

3.4. Analysis of Flora Structure and Abundance

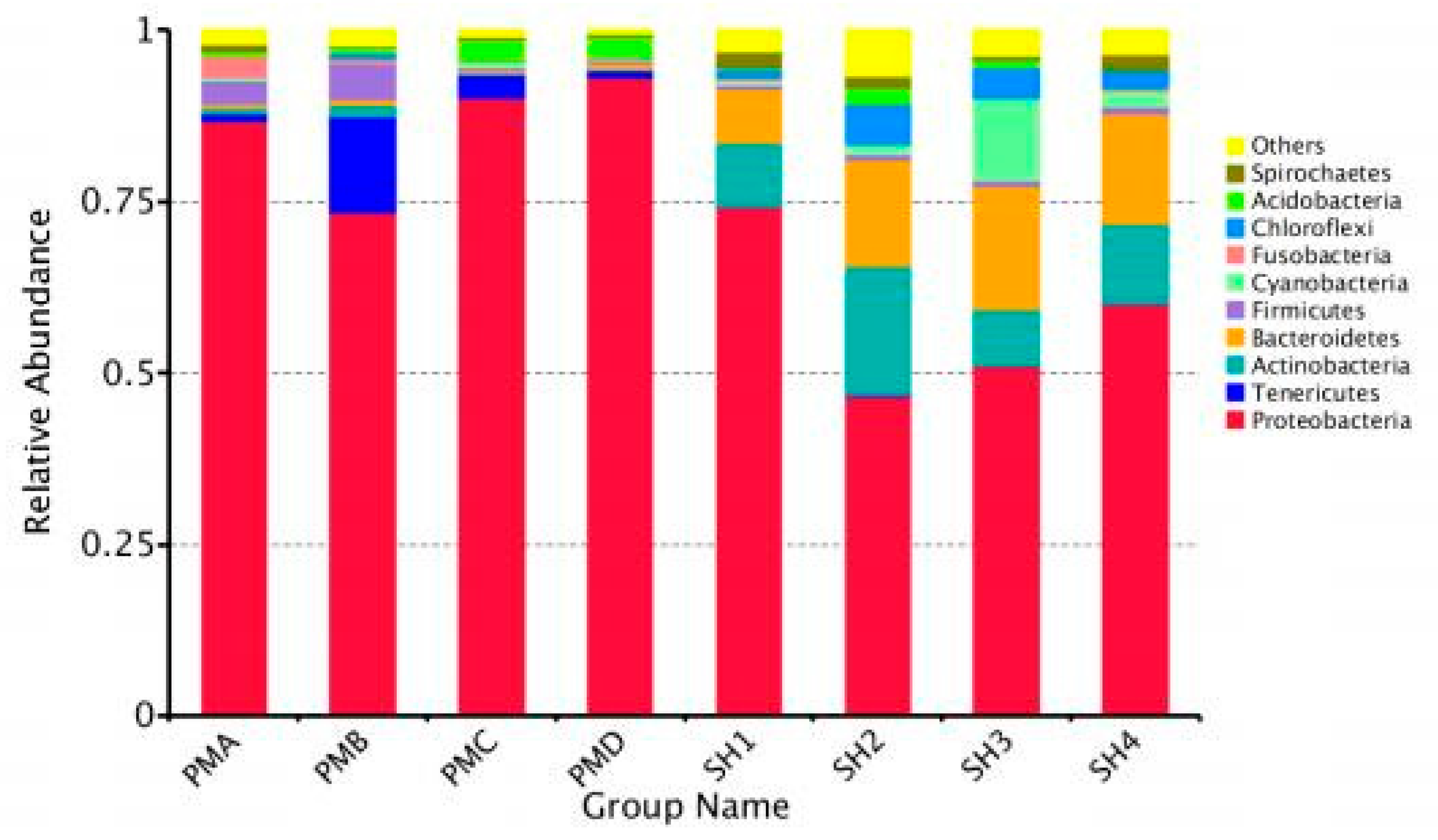

3.4.1. Microflora Structure Under Phyla Classification Level

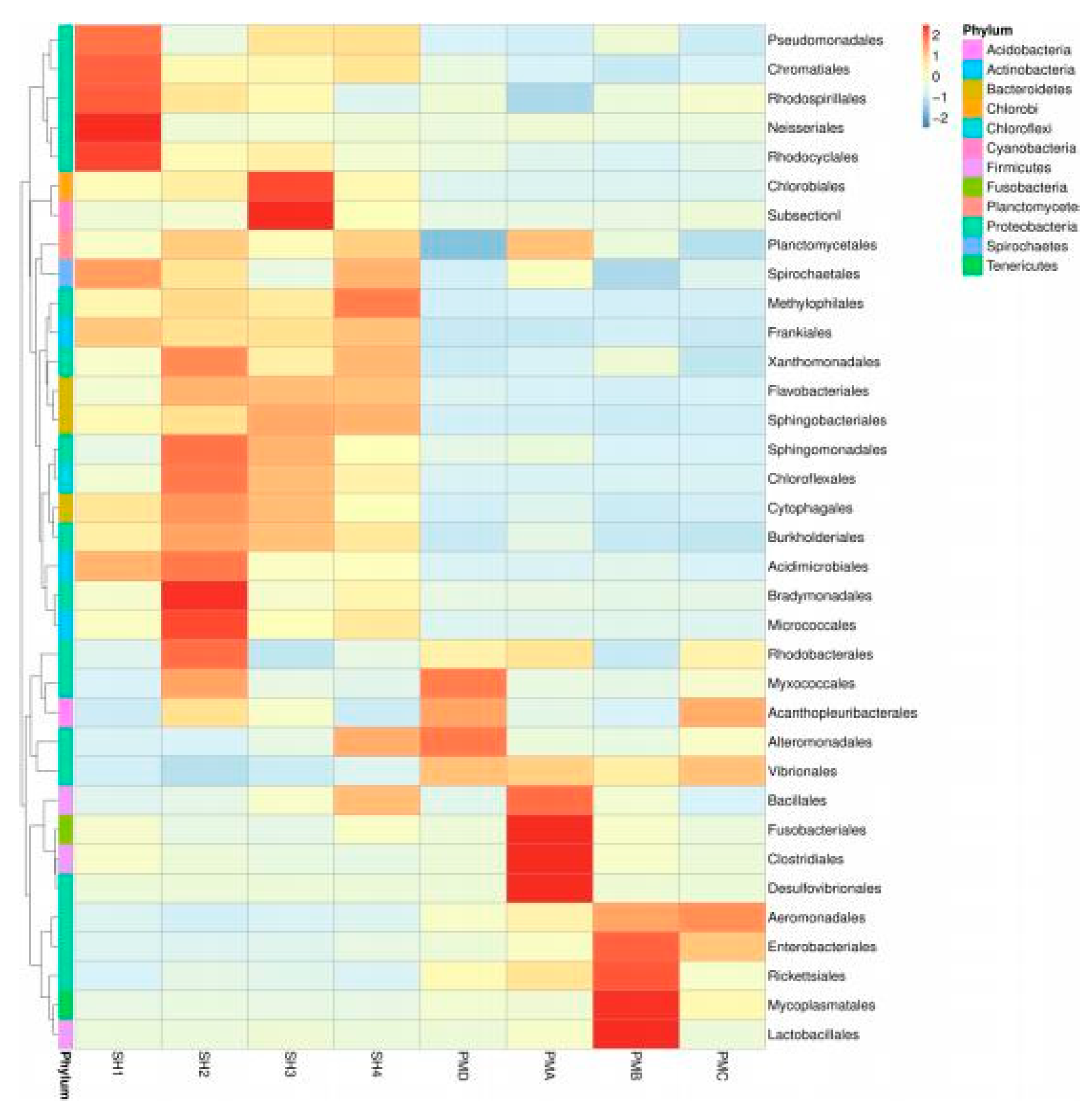

3.4.2. Flora Structure at the Order Classification Level

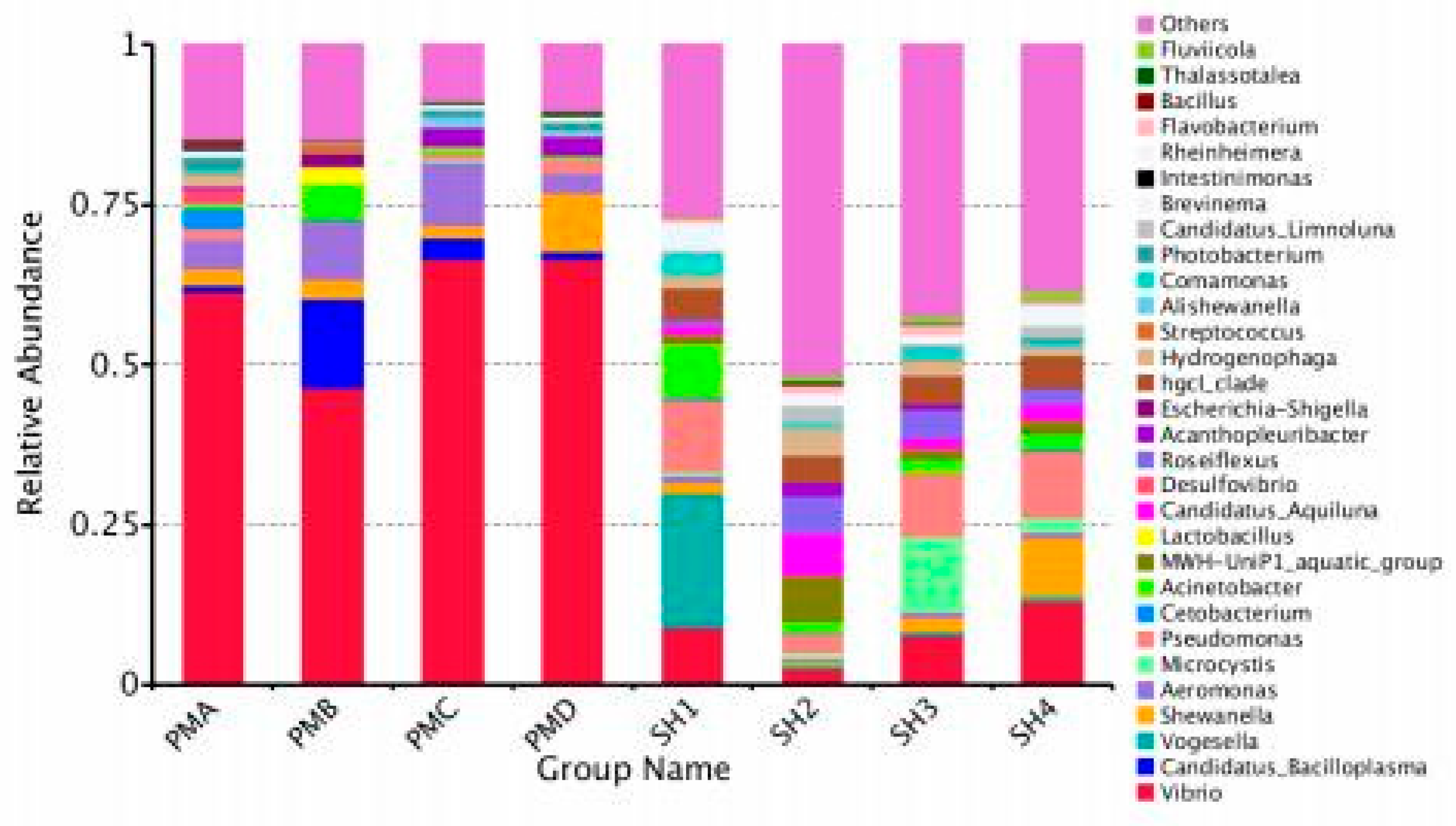

3.4.3. Microflora Structure at Genus Classification Level

3.5. Analysis of Flora Diversity and Similarity

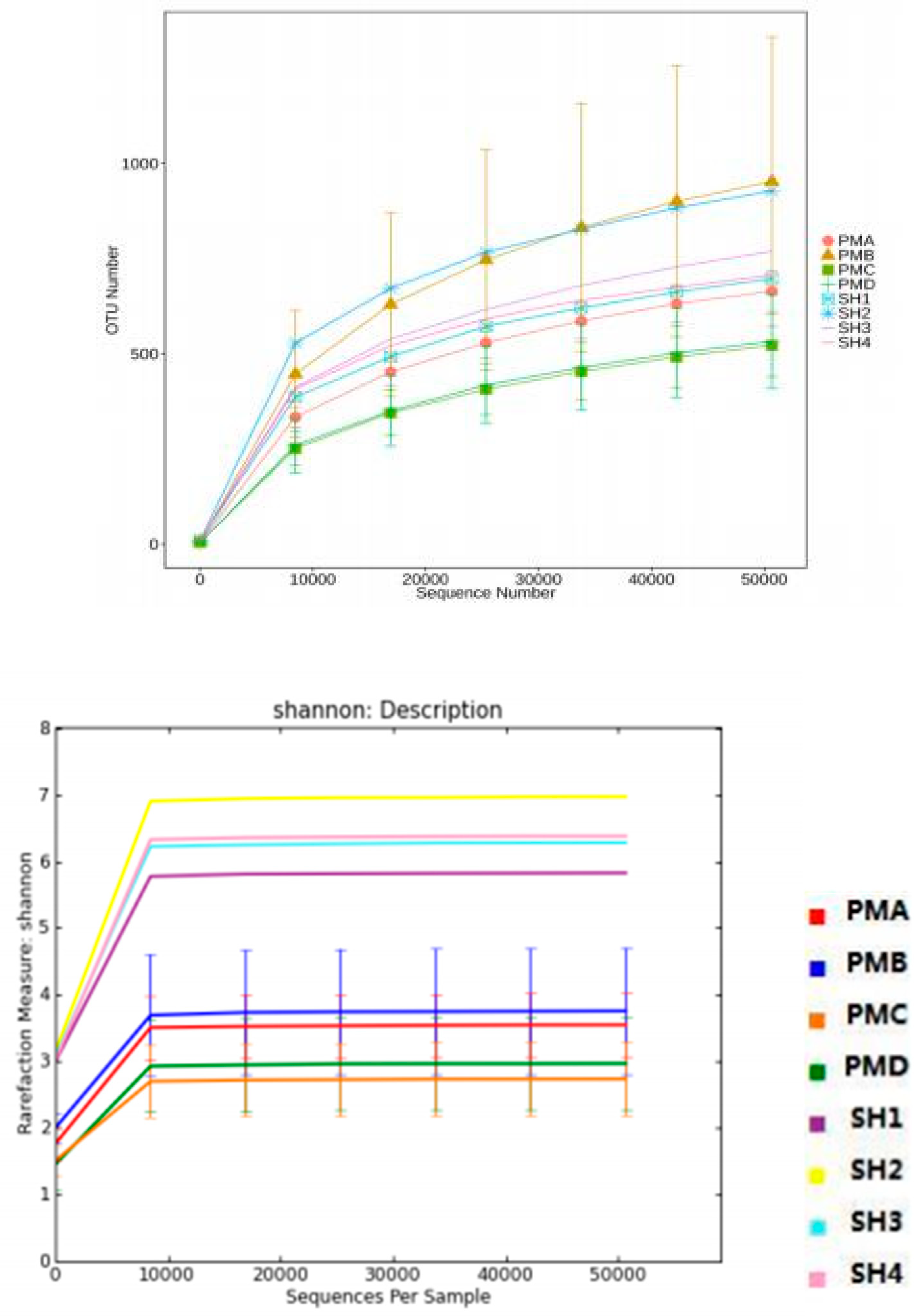

3.5.1. Alpha Diversity Index Analysis

3.5.2. Alpha Diversity Curve Analysis

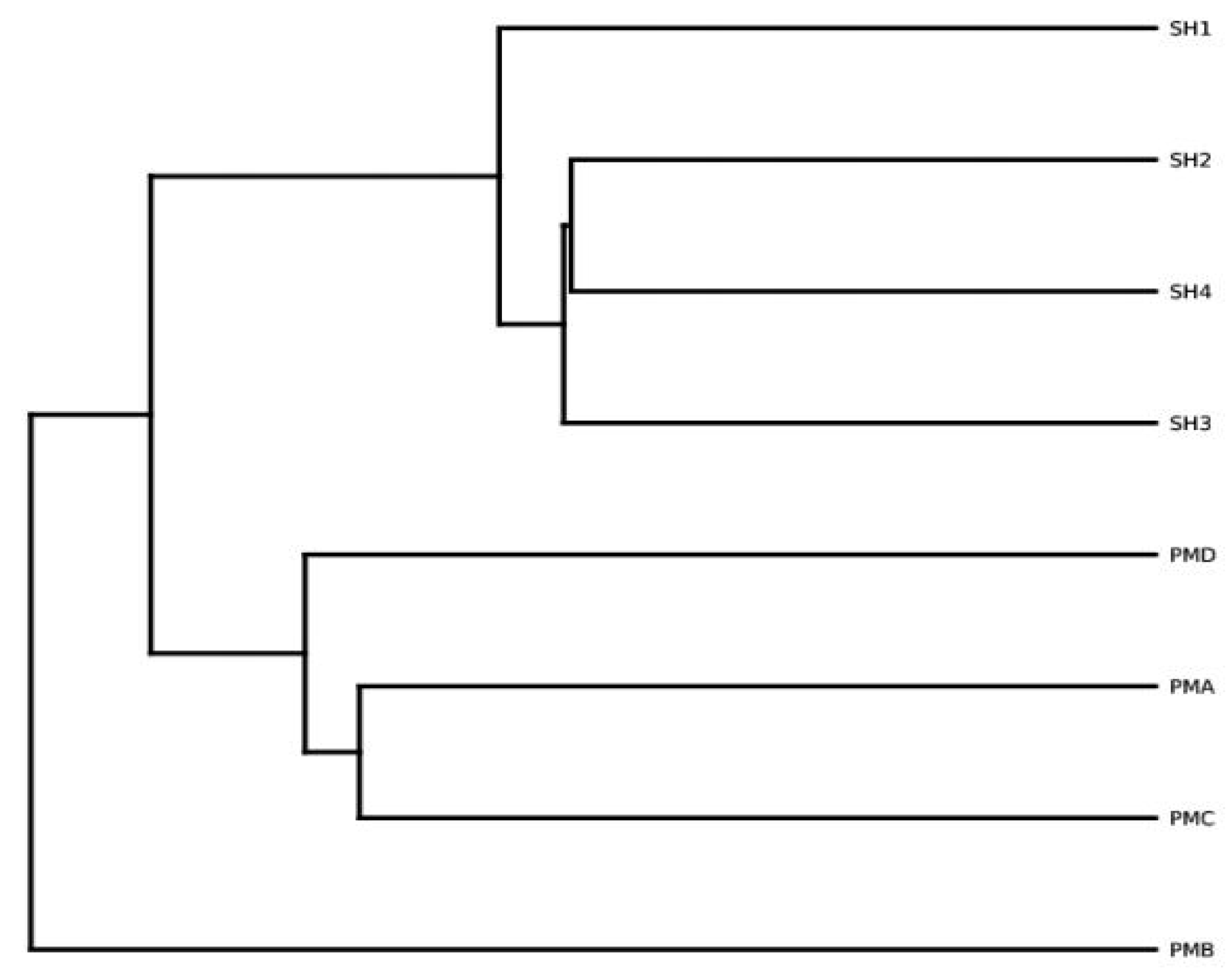

3.5.3. Species Similarity Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Water Quality Index Data Analysis

4.2. OTU Cluster Analysis of Prawn Gut and Its Aquaculture Water Body

4.3. Analysis and Discussion on the Structure of Intestinal Flora of Penaeus Prawn and Its Aquaculture Water

4.4. Analysis of Microbial Diversity in Prawn Intestine and Its Aquaculture Water

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Naylor, R.L.; Hardy, R.W.; Buschmann, A.H.; Bush, S.R.; Cao, L.; Klinger, D.H.; Little, D.C.; Lubchenco, J.; Shumway, S.E.; Troell, M. A 20-year retrospective review of global aquaculture. Nature. 2021, 591, 551–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, S.; Huang, Z.; Hou, D.; He, J. Intestinal Microbiota Dysbiosis and Its Association with Disease in Shrimp: A Review. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 13213–13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmild, M.; Hukom, V.; Nielsen, R.; Nielsen, M. Is economies of scale driving the development in shrimp farming from Penaeus monodon to Litopenaeus vannamei?The case of Indonesia. Aquaculture. 2024, 579, 740178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmanuel, A.; Wei, Y.; Ramzan, M.N.; Yang, W.; Zheng, Z. Dynamics of Bacterial Communities and Their Relationship with Nutrients in a Full-Scale Shrimp Recirculating Aquaculture System in Brackish Water. Animals. 2025, 15, 1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoqratt, M.Z.H.M.; Eng, W.W.H.; Thai, B.T.; Austin, C.M.; Gan, H.M. Microbiome Analysis of Pacific White Shrimp Gut and Rearing Water from Malaysia and Vietnam. PeerJ. 2018, 6, e5826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abakari, G.; Wu, X.; He, X.; Fan, L.; Luo, G. Bacteria in Biofloc Technology Aquaculture Systems: Roles and Mediating Factors. Rev. Aquaculture. 2022, 14, 1260–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.C.; Bass, D.; Stentiford, G.D.; van der Giezen, M. Understanding the Role of the Shrimp Gut Microbiome in Aquaculture. J. Fish Dis. 2021, 44, 1109–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; et al. Dynamics of the Gut Microbiota in Developmental Stages of Shrimp. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaizumi, K.; Sakamoto, R.; Inoue, Y.; et al. Analysis of Microbiota in the Stomach and Midgut of Two Penaeid Shrimps during Probiotic Feeding. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, E.; Gueguen, Y.; Magré, K.; et al. Bacterial Community Characterization of Water and Intestine of the Shrimp Litopenaeus stylirostris in a Biofloc System. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; et al. Temporal Dynamics of Shrimp Gut Microbiota Following Probiotic/Herbal Treatment. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 10, 1332585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.T.; Chen, I.T.; Li, C.Y.; et al. Gut Microbiota Dynamics in Shrimp Infected with Pathogenic vs. Non-Pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus. mSystems. 2023, 8, e00447–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angthong, P.; Uengwetwanit, T.; Uawisetwathana, U.; et al. Investigating Host–Gut Microbial Relationship in Penaeus monodon upon Exposure to Vibrio harveyi. Aquaculture. 2023, 567, 739252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, S.; et al. Intestine Bacterial Community Composition of Shrimp Varies under Low- and High-Salinity Culture Conditions. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 589164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicala, F.; Lago-Lestón, A.; Gomez-Gil, B.; et al. Gut Microbiota Shifts in the Giant Tiger Shrimp Penaeus monodon during Ontogenetic Development. Aquac. Int. 2020, 28, 1421–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo-Granados, F.; Lopez-Zavala, A.A.; Gallardo-Becerra, L.; et al. Host Genome Drives the Microbiota Enrichment of Beneficial Shrimp Strains. Anim. Microbiome. 2025, 7, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Xu, W.; et al. Dynamic Changes of Environment and Gut Microbial Community of Litopenaeus vannamei in Greenhouse Farming. Fishes. 2024, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, M.H.; Ghaedi, A.; Rastegar, M.; et al. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics in Shrimp Aquaculture: Growth, Immunity, and Disease Resistance. Aquaculture. 2024, 580, 738651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, B.; Zhang, K.; Wang, L.; et al. Microbes and Their Effect on Growth Performance of Litopenaeus vannamei in Biofloc Systems: A Review. Microorganisms. 2024, 12, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Microbiome Determinants of Productivity in Shrimp Aquaculture. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e02420–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Xu, H.; Zhang, C.; et al. Profile of the Gut Microbiota of Pacific White Shrimp under Industrial Indoor Farming System. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 108, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Xiong, J.; Li, C.; et al. Core Gut Microbiota of Shrimp Function as a Regulator to Maintain Intestinal Homeostasis and Promote Health. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02465–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Postlarval Shrimp-Associated Microbiota and Ecological Processes over AHPND Progression. Microorganisms. 2025, 13, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gai, C.; et al. WSSV Infection in the Gut Microbiota of the Black Tiger Shrimp Penaeus monodon. Fishes. 2025, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Zeng, S.; Hou, D.; et al. Microecological Koch’s Postulates Reveal that Intestinal Microbiota Dysbiosis Contributes to Shrimp White Feces Syndrome. ISME J. 2020, 14, 1630–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J. Characterization of bacterial community in intestinal and rearing water of Penaeus monodon differing growth performances in outdoor and indoor ponds. Aquaculture Research 2020, 51, 4376–4387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angthong, P.; Uengwetwanit, T.; Arayamethakorn, S.; Chaitongsakul, P.; Karoonuthaisiri, N.; Rungrassamee, W. Bacterial analysis in the early developmental stages of the black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon). Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 4896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garibay-Valdez, E.; Martínez-Córdova, L.R.; López-Torres, M.A.; Almendariz-Tapia, F.J.; Martínez-Porchas, M.; Calderón, K. The implication of metabolically active Vibrio spp. in the digestive tract of Litopenaeus vannamei for its post-larval development. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, M.; Lo, T.H.W.; Lazzarotto, V.; Briggs, M.; Smullen, R.P.; Barnes, A.C. Biodiversity of the intestinal microbiota of black tiger prawn (Penaeus monodon) increases with age and is only transiently impacted by major ingredient replacement in the diet. Aquaculture Reports 2022, 22, 100948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Li, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, F. Crustin Defense against Vibrio parahaemolyticus Infection by Regulating Intestinal Microbial Balance in Litopenaeus vannamei. Marine Drugs 2023, 21, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-T.; Huang, W.-T.; Wu, P.-L.; Kumar, R.; Wang, H.-C.; Lu, H.-P. Low salinity stress increases the risk of Vibrio parahaemolyticus infection and gut microbiota dysbiosis in Pacific white shrimp. BMC Microbiology 2024, 24, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mat Deris, Z.; Iehata, S.; Gan, H.M.; Ikhwanuddin, M.; Najiah, M.; Asaduzzaman, M.; et al. Understanding the effects of salinity and Vibrio harveyi on the gut microbiota profiles of Litopenaeus vannamei. Frontiers in Marine Science 2022, 9, 974217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Liao, X.; Long, X.; Zhao, J.; He, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, T.; Sun, C. Vibrio alginolyticus Infection Induces Coupled Changes of Bacterial Community and Metabolic Phenotype in the Gut of Swimming Crab. Aquaculture 2019, 499, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rungrassamee, W.; Klanchui, A.; Maibunkaew, S.; Chaiyapechara, S.; Jiravanichpaisal, P.; Karoonuthaisiri, N. Bacterial population in intestines of the black tiger shrimp (Penaeus monodon) under different growth stages. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8, e60802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.; Qi, L.; Fu, L.; Tian, M.; Zhang, X.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, Y. Dynamics of the gut microbiota in developmental stages of Litopenaeus vannamei and its association with body weight. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, J.; Zhu, J.; Dai, W.; Dong, C.; Qiu, Q.; Li, C. The underlying ecological processes of gut microbiota among cohabitating retarded, overgrown and normal shrimp. Microbial Ecology 2017, 73, 988–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, P.; Guo, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, R.; et al. Gastrointestinal microbiota imbalance is triggered by the enrichment of Vibrio in subadult Litopenaeus vannamei with acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Sun, X. Core Gut Microbiota of Shrimp Function as a Regulator to Maintain Immune Homeostasis in Response to WSSV Infection. Microbiology Spectrum 2023, 11(3), e01180–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Liu, P.-P.; Yao, J.-Y.; Vasta, G.R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X. Shrimp Intestinal Microbiota Homeostasis: Dynamic Interplay Between the Microbiota and Host Immunity. Reviews in Aquaculture 2025, 17(1), e12986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Sample Names |

Valid sequence | Avg Len (nt) | Q20 | Q30 | GC% | Effective% |

| PMA | 84067 | 253 | 99.12 | 98.23 | 52.90 | 88.77 |

| PMB | 85093 | 253 | 99.29 | 98.58 | 52.32 | 89.15 |

| PMC | 84922 | 253 | 99.34 | 98.65 | 52.94 | 92.32 |

| PMD | 84456 | 253 | 99.30 | 98.59 | 53.10 | 90.51 |

| SH1 | 89203 | 253 | 99.34 | 98.60 | 53.80 | 91.43 |

| SH2 | 84365 | 253 | 99.34 | 98.61 | 53.57 | 94.68 |

| SH3 | 87808 | 253 | 99.31 | 98.58 | 53.49 | 93.27 |

| SH4 | 79681 | 253 | 99.31 | 98.57 | 53.33 | 90.74 |

| Sample Names | Total_tag | Taxon_Tag | Unique_Tag | OTU_num |

| PMA | 81853 | 80778 | 1069 | 784 |

| PMB | 75182 | 73775 | 1407 | 1119 |

| PMC | 79882 | 79326 | 555 | 638 |

| PMD | 81857 | 81259 | 596 | 651 |

| SH1 | 83173 | 80554 | 2617 | 812 |

| SH2 | 81583 | 79317 | 2266 | 1071 |

| SH3 | 83688 | 81546 | 2142 | 881 |

| SH4 | 73983 | 71725 | 2258 | 821 |

| Classification | PMA | PMB | PMC | PMD | SH1 | SH2 | SH3 | SH4 |

| Vibrio genus Candidatus_Bacilloplasma |

61.48% | 46.51% | 66.48% | 66.52% | 9.04% | 2.45% | 7.83% | 13.15% |

| Candidatus | 0.99% | 13.87% | 3.38% | 1.19% | 0.00% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Vogesella | 0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% | 20.92% | 0.66% | 0.67% | 0.72% |

| Shewanella | 2.54% | 2.88% | 1.99% | 9.10% | 1.71% | 0.59% | 1.96% | 9.07% |

| Aeromonas SPP | 4.61% | 8.87% | 9.76% | 3.12% | 1.09% | 0.42% | 0.95% | 1.02% |

| Microcystis | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.51% | 0.03% | 0.69% | 0.93% | 11.76% | 2.21% |

| Pseudomonas | 1.65% | 0.32% | 1.01% | 2.09% | 11.21% | 3.05% | 10.04% | 10.43% |

| Cetobacterium sporomonas | 3.27% | 0.44% | 0.16% | 0.20% | 0.36% | 0.03% | 0.01% | 0.46% |

| Acinetobacter Actinomyces | 0.70% | 5.46% | 0.94% | 0.54% | 8.39% | 1.71% | 2.11% | 2.17% |

| Others Others | 24.70% | 21.63% | 15.75% | 17.21% | 45.25% | 82.92% | 63.03% | 58.62% |

| Sample Group | shannon | Simpson | chao1 | ACE | goods_coverage |

| PMA | 3.549 | 0.674 | 784.482 | 829.319 | 0.996 |

| PMB | 3.758 | 0.744 | 1192.509 | 1226.536 | 0.994 |

| PMC | 2.738 | 0.577 | 691.362 | 694.126 | 0.997 |

| PMD | 2.97 | 0.625 | 687.119 | 709.296 | 0.997 |

| SH1 | 5.825 | 0.94 | 915.686 | 900.221 | 0.996 |

| SH2 | 6.971 | 0.981 | 1114.667 | 1133.218 | 0.996 |

| SH3 | 6.279 | 0.967 | 1060.011 | 1036.474 | 0.995 |

| SH4 | 6.378 | 0.971 | 801.375 | 830.585 | 0.997 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).