Submitted:

24 September 2025

Posted:

25 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Theoretical Framework

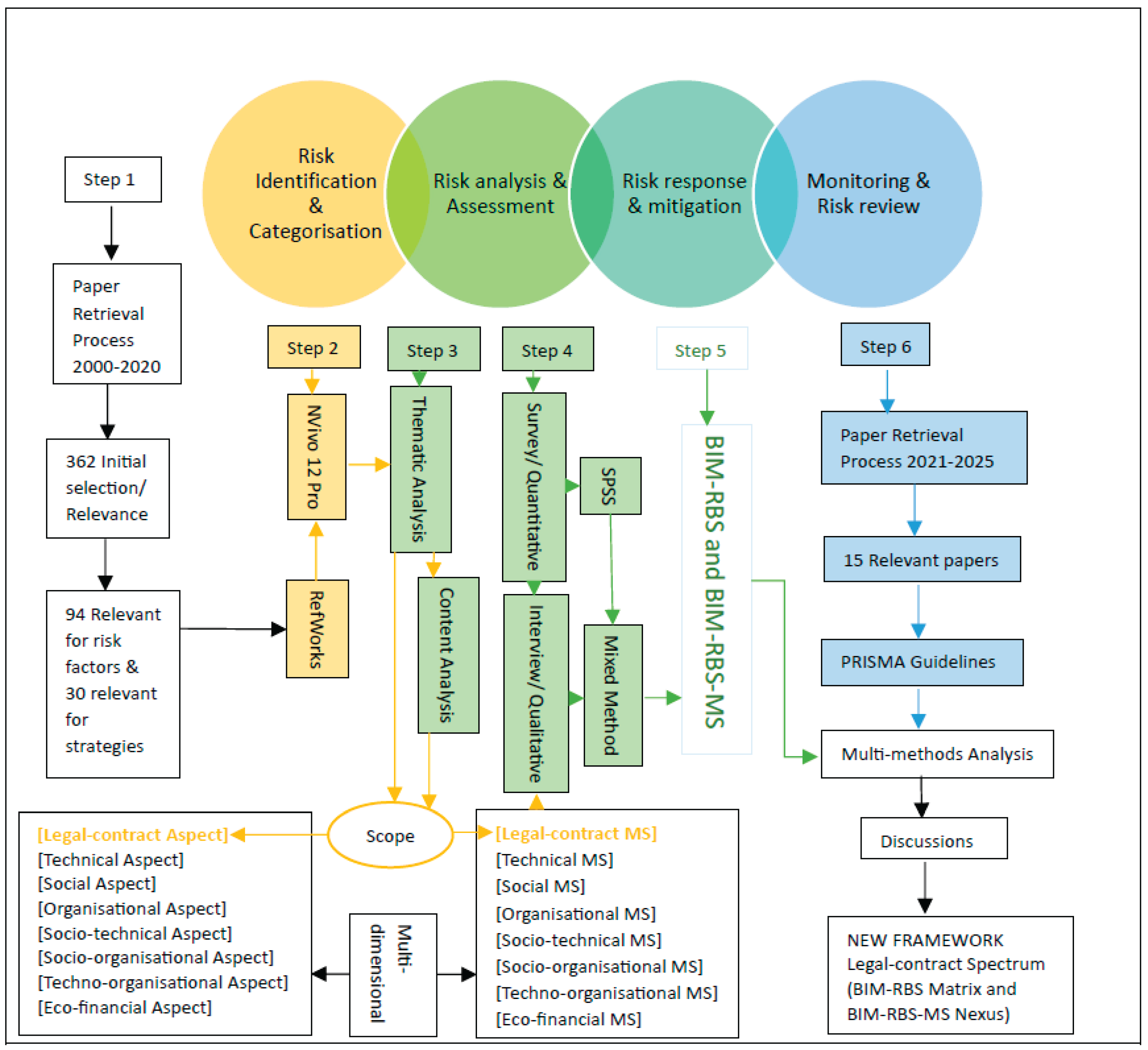

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design and Paper Retrieval Process

2.2. Survey and Interviews

- Variables and Scales: Nominal (N) Gender and Age; Ordinal (O) Level of BIM experience, BIM-RBS as the outcome variable and shares the same properties as the dependent variables; String (S) BIM-RBS-MS as the intervening variable that transmit the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable.

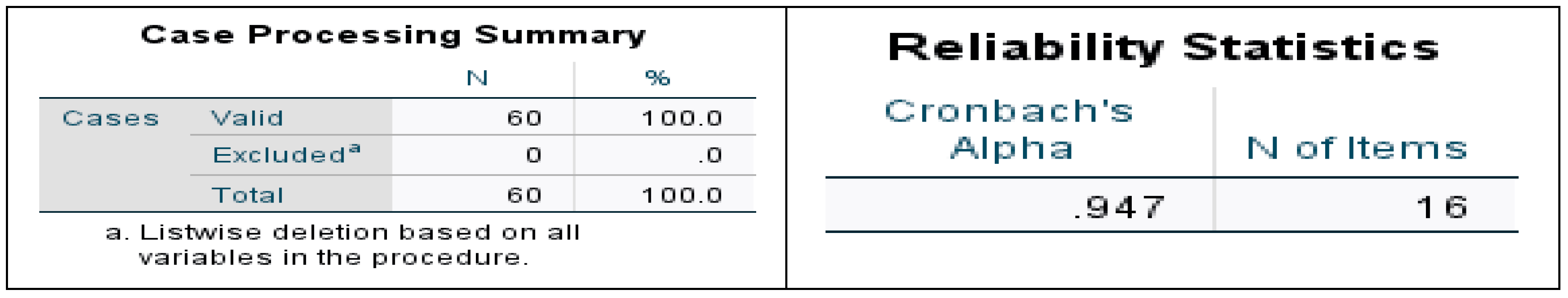

- Cronbach's Alpha (α) test (CA): Utilised to measure internal consistency/reliability of the survey scale. It assessed the reliability of multiple Likert-scale questions determining the magnitude of risk factors (BIM-RBS). Various thresholds were applied and the test procedure involved [Click Analyse > Scale > Reliability Analysis > select the variables > ensuring the model says 'Alpha' > then click OK].

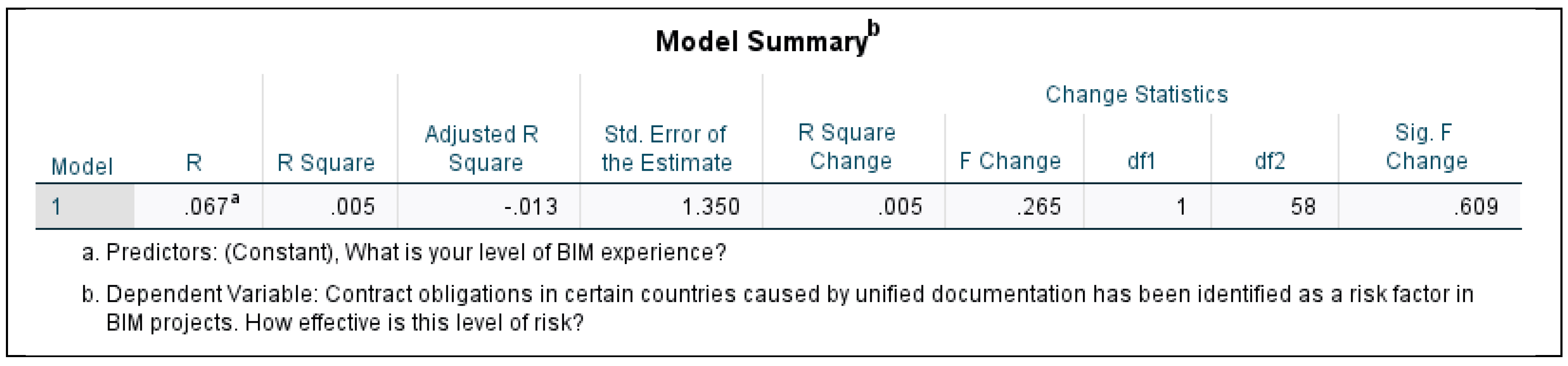

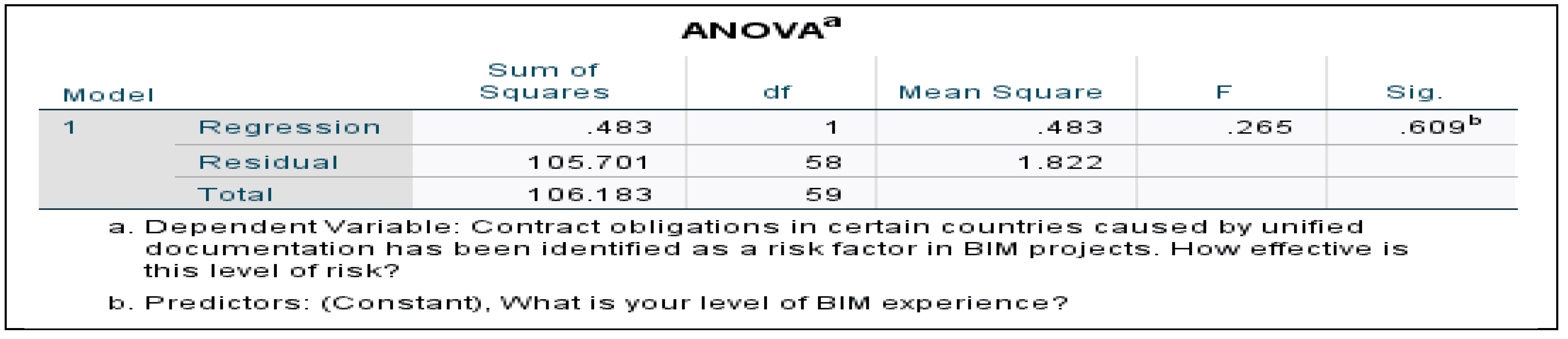

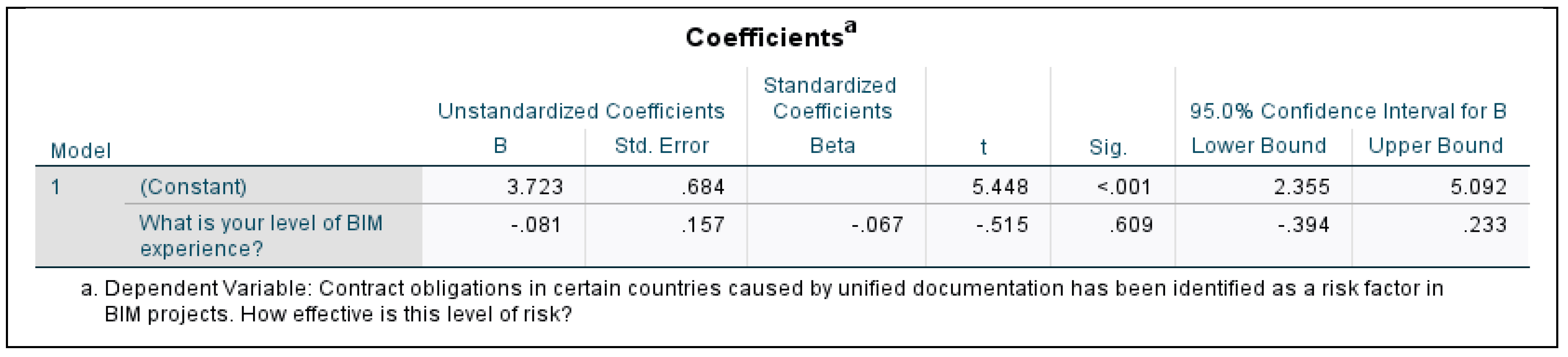

- Simple linear regression (SLR): Strive to predict the outcome variable (BIM-RBS) using the predictor variable (Level of BIM experience). The test procedure involved [Click Analyse > Regression > Linear > select outcome variable and move to the 'Dependent' box > select predictor variable and move to the 'Block 1 of 1' box > Select Statistics > click Estimates, Confidence Intervals, Model Fit, R Squared Change, and Descriptives].

2.3. Mixed Method

3. Results and Analysis

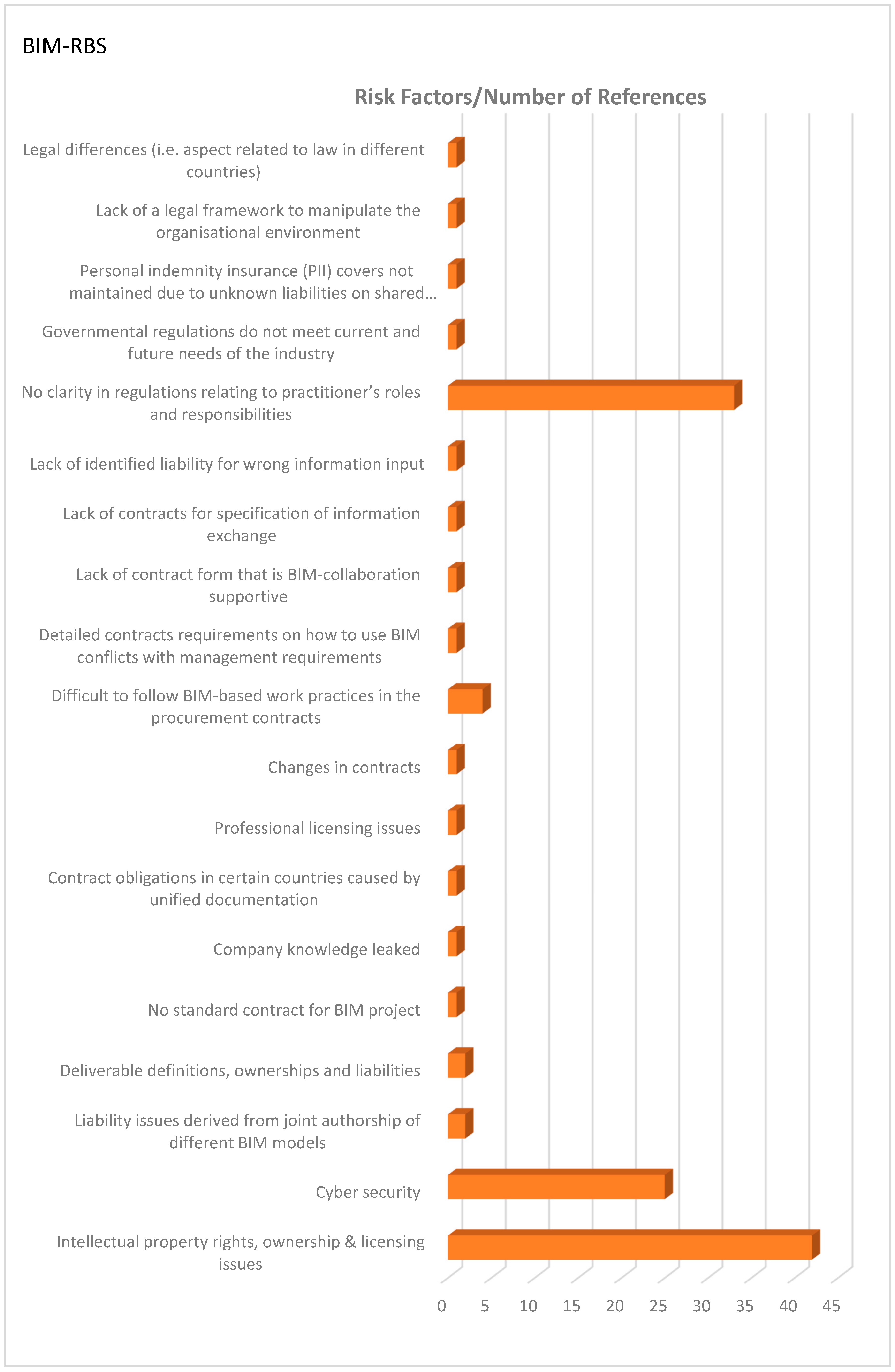

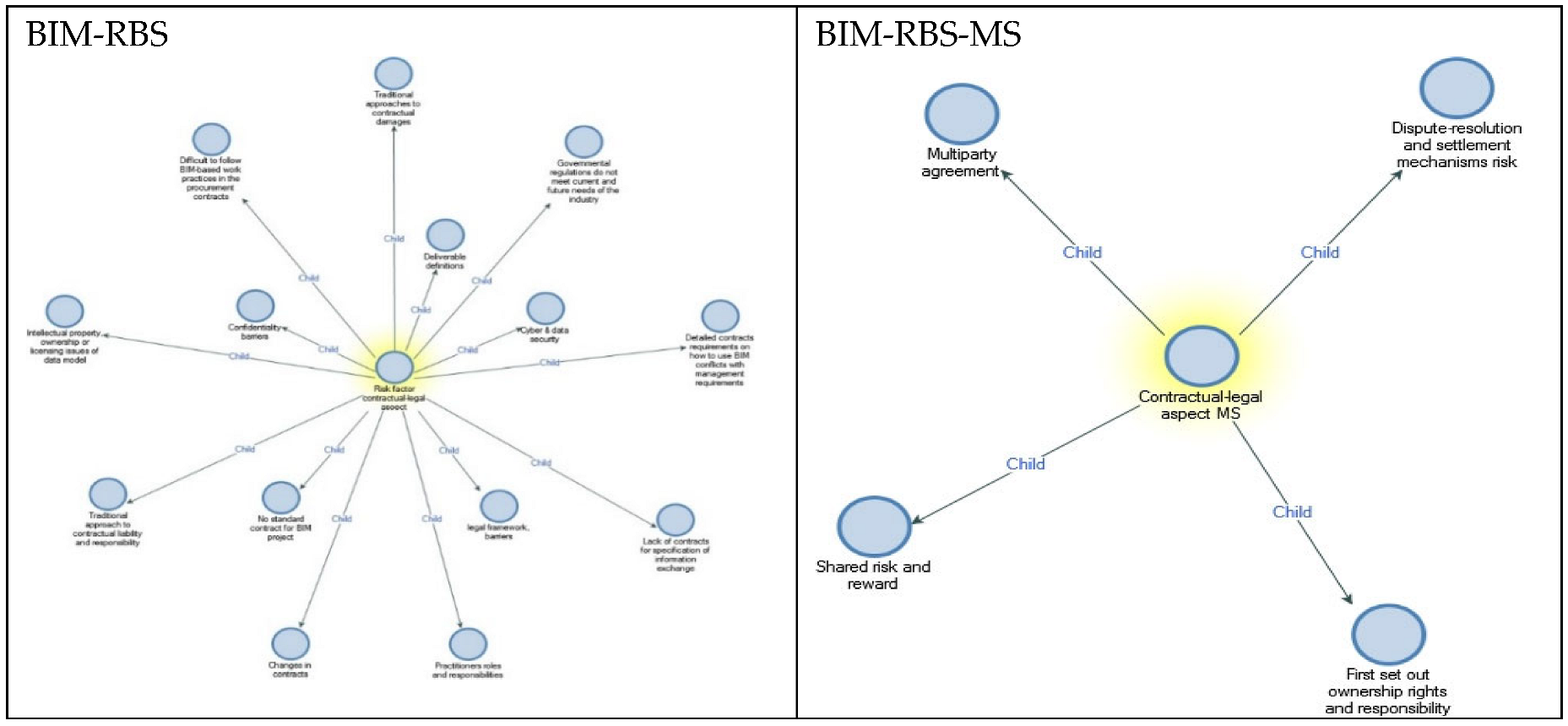

3.1. Secondary Data Analysis (Literature Review)

3.2. Primary Data Analysis (Interviews)

3.3. Primary Data Analysis (Survey)

3.4. Findings

| BIM-RBS (Risk factors) | BIM-RBS-MS (Management strategies) | References |

|---|---|---|

| Conditions of the Agreement | Incorporate BIM standards and protocols into the contract guidelines such as: -NEC3 and NEC4 contracts -CIOB contract - FIDIC contract - ACA) PPC 2000 contract - JCT CE contract -SBCC contract - CIC/BIM Protocol - Function: Add-on contract clauses - Standards: BS 1192/PAS1192 |

Muhammad and Nasir, (2022) El Hajj et al., (2023) Dao et al., (2021) Mohammadi et al., (2024) Erpay and Sertyesilisik, (2021) Weber and Achenbach, (2023) Nilchian et al., (2022) Mahdian et al., (2023) |

| Data security | Establish data security policies and inspection procedures, and assign responsibilities for data backup and recovery. (model creation/ signing the contracts with their subsets) | |

| ICT protocols and liability | Employ common data environment (CDE) and BIM execution plan (BEP) to promote data sharing and cooperation | |

| Intellectual property and Copyright Ownership Model ownership |

In the contractual agreement establish intellectual property rights, copyright ownership and licenses for the usage of the model. (updating LOD table and modelling requirements) (IFC) (BIM protocol) | |

| Data infringement and confidentiality. | BIM data governance, protect confidential data from corruption, theft, or manipulation by project players | |

| Hosting and archiving of BIM Files/ Missing files/ Authenticity of the files/ File misuse/ Adequacy and method of transferred files | Define BIM, integrated model and modelling requirements | |

| Access rights to specify model users and the authority to share information to other parties | Define model element, production and delivery table with naming convention | |

| BIM model issues: quality control; error; inaccurate; inconsistent; integrity and responsibility of model. | Define LOD, availability of information and technology, and the licensing of the model. | |

| Method of resolving clashes | Define model user and author | |

| Contradiction between BIM and construction method | Define project information requirements | |

| Unclear rights and legal obligations and responsibilities | Define the role of BIM coordinator, relationships between BIM stakeholder in the contracts and appendix. Establish standards and guidelines for BIM adoption. | |

| Uncertainty of the current status of legal system in the country where BIM is adopted | Government schemes with clear standard/duty of care for each project stakeholder | |

| Modification Rights | Sought permission from copyright owner | |

| Legal status of the BIM Model as the ‘single source of truth’ | (Using meta data, e.g. Map viewer BIM without disclosures) (BEP) (Addendum) Industry-wide cultural change |

|

| Unclear BIM standards and protocols used in contract | (ISO; PAS; BSI Standards) CIC/BIM Protocol |

| Categories | Magnitude of risk factors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Legal-contract Aspect | Very low risk | Low risk | Medium risk | High risk | Very high risk |

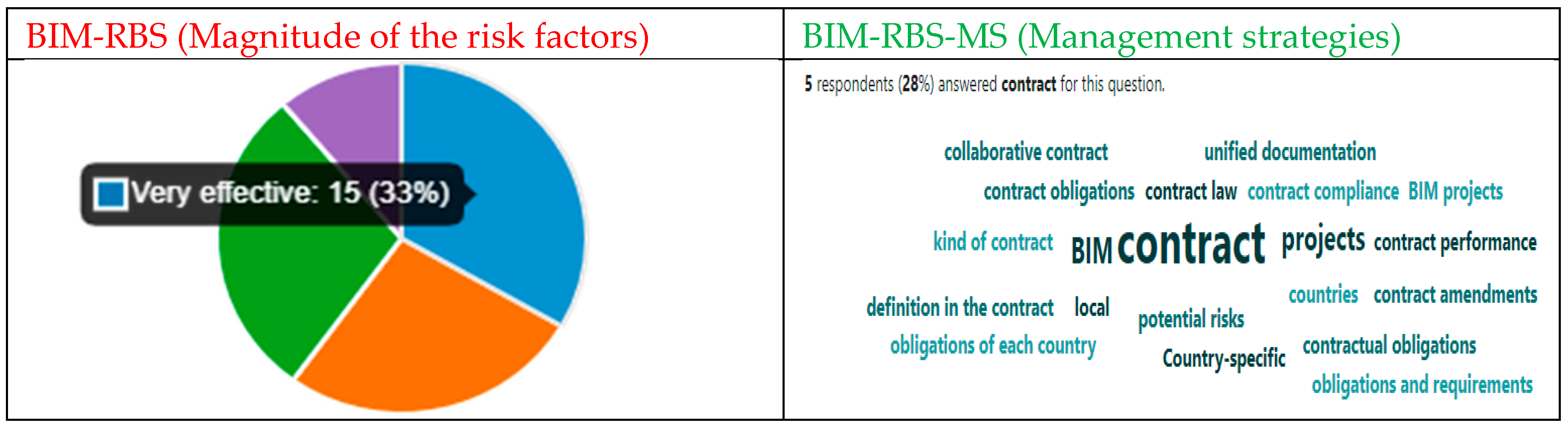

| Contract obligations caused by unified documentation | 11 | 0 | 29 | 27 | 33 |

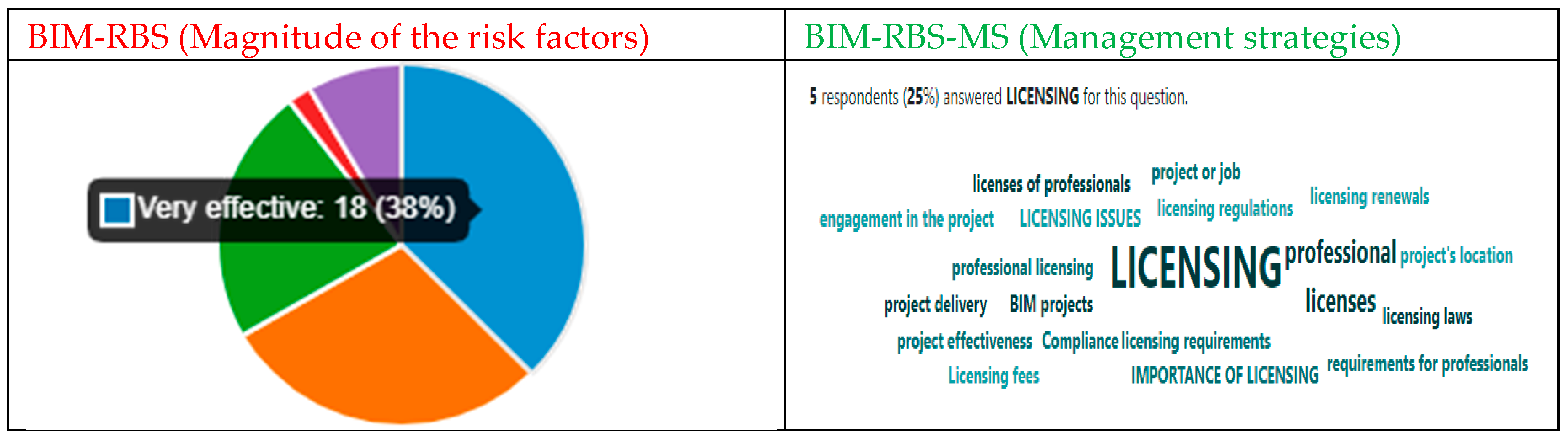

| Professional licensing issues | 8 | 2 | 23 | 29 | 38 |

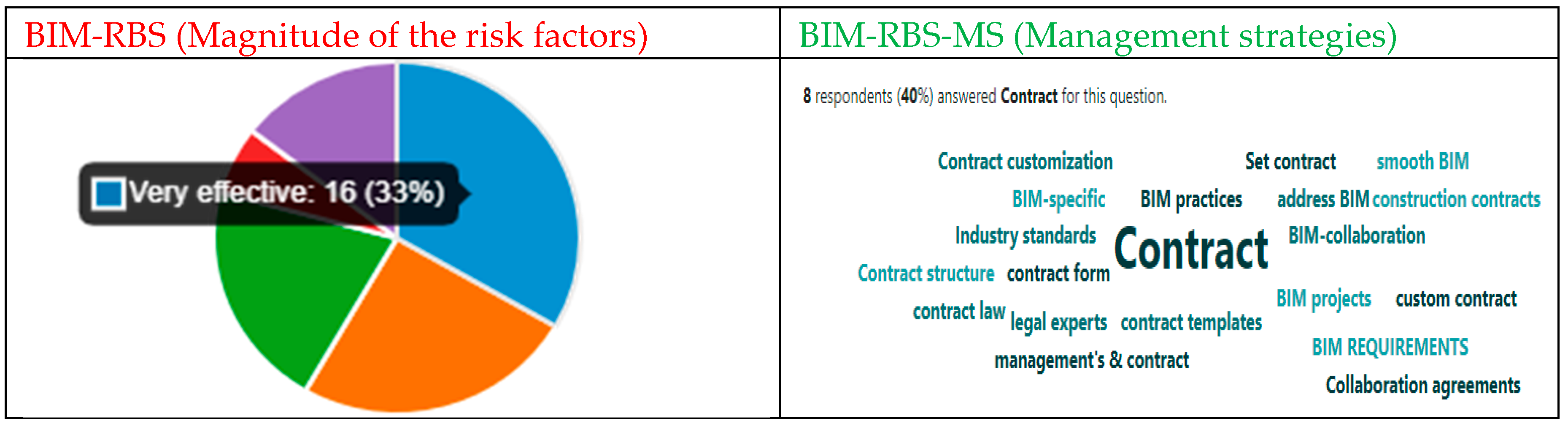

| Lack of supportive BIM-collaboration contract form | 15 | 6 | 21 | 25 | 33 |

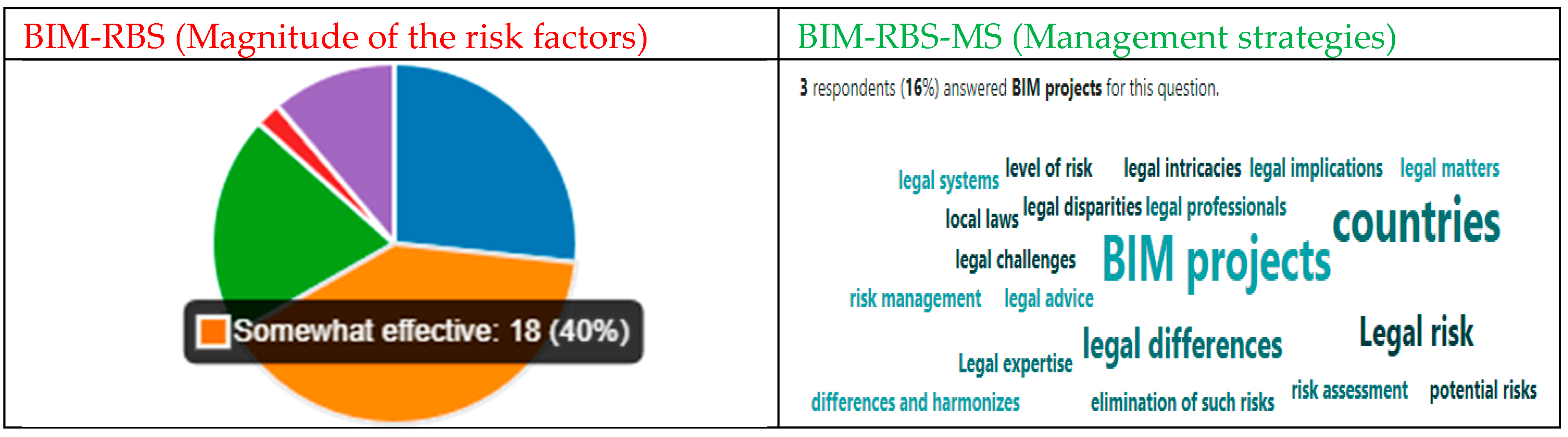

| Issues with legal differences of various countries laws | 11 | 2 | 20 | 40 | 27 |

| Average (%) | 11.25 | 2.5 | 23.25 | 30.25 | 32.75 |

| LSTM | Equilibrium state |

<<<<<<<< >>>>>>>> |

Disequilibrium state | ||

3.5. Discussions

4. Conclusion and Knowledge Contributions

Recommendations for Innovation and Knowledge Impact

- Adopt the BIM-RBS Matrix as a proactive tool during contract preparation and project planning phases to clarify risk allocation, reduce disputes, and improve collaboration.

- Use the BIM-RBS–MS Nexus to guide the selection of tailored management strategies, ensuring that digital, legal, and organisational risks are jointly addressed rather than managed in isolation.

- Invest in training and capacity building to equip project managers, legal advisors, and BIM coordinators with the skills required to operationalise these frameworks.

- Integrate the BIM-RBS framework into national and international BIM guidelines (e.g., ISO 19650, NEC, JCT, CIC) to provide standardised guidance on risk allocation and contractual provisions.

- Encourage the development of dispute resolution protocols specific to BIM by recognising the unique challenges of shared digital environments.

- Promote incentives for collaborative risk-sharing models, such as shared risk–reward mechanisms, to align stakeholder interests and reduce adversarial practices.

- Further investigation is needed across socio-organisational, eco-financial, and techno-organisational perspectives to validate and refine the framework across different contexts.

- Future research should empirically test the BIM-RBS Matrix across jurisdictions, contract types, and project scales, ensuring global applicability.

- Theoretical development is required to strengthen the legal-contractual dimension within BIM adoption models, thereby extending current construction management theory.

List of Acronyms

| ACA | Association of Consultant Architects |

| AEC | Architecture Engineering Construction |

| AIA | American Institute of Architects |

| BbCNs | BIM-based Construction Networks |

| BEP | BIM execution plan |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| CA | Cronbach's Alpha (α) test |

| CDBB | Central of digital built Britain |

| CDE | Common Data Environment |

| CIOB | Chartered Institute of Building |

| CIC | Construction Industry Council |

| DBB | Design bid-build |

| FIDIC | Fédération Internationale des Ingénieurs-Conseils (International Federation of Consulting Engineers) |

| GC | General Contractor |

| IFC | Industry Foundation Classes |

| IPD | Integrated Project Delivery |

| IPR | Intellectual Property Rights |

| ISO | International Organisation for Standardisation |

| JCT | Joint Contracts Tribunal |

| LCA | Legal Contract Aspect |

| LOD | Level of Development |

| LSTM | Leavitt Socio-technical Model |

| MoU | Memoranda of Understanding |

| MS | Management Strategies |

| NBS | National Building Specification |

| NEC | New Engineering Contracts |

| PAS | Publicly Available Specification |

| PII | Personal Indemnity Insurance |

| PPC | Project partnering contract |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| RBS | Risk Breakdown Structure |

| SBCC | Scottish Building Contracts Committee |

| SLR | Simple Linear Regression |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

| UK | United Kingdom |

| VC | Version Control |

Appendix A

References

- Akhtar, D.M.I. , (2016) Research design. Research in Social Science: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. pp.68-84. Available online at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Research+Design+Md.+Inaam+Akhtar+Deptt.

- Aksenova, G.; Kiviniemi, A.; Kocaturk, T.; Lejeune, A. From Finnish AEC knowledge ecosystem to business ecosystem: lessons learned from the national deployment of BIM. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 37, 317–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarri, K.; Aljarman, M.; Boussabaine, H. Emerging contractual and legal risks from the application of building information modelling. Eng. Constr. Arch. Manag. 2019, 26, 2307–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotaibi, B.S.; Waqar, A.; Radu, D.; M. KHan, A.; Dodo, Y.; Althoey, F.; Almujibah, H. Building information modeling (BIM) adoption for enhanced legal and contractual management in construction projects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharom, M.H.; Habib, S.N.H.A.; Ismail, S. Building Information Modelling (BIM): Contractual Issues of Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) in Construction Projects. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, T.; Petri, I.; Rezgui, Y.; Rana, O. Management of Collaborative BIM Data by Federating Distributed BIM Models. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2017, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalah, M.; Elouadi, A.; Mharzi, H. Overview: the opportunity of BIM in railway. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2019, 8, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berema, R.K.R.; Ismail, Z.; Brahim, J. Comparative Analysis of Existing Contracts for Building Information Modelling (BIM) Projects in Malaysia and Selected Common Law Countries. Int. J. Sustain. Constr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 12, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Building Information Modelling (BIM) PROTOCOL (2018) Standard Protocol for use in projects using Building Information Models. Second edition. Construction Industry Council. London.

- Butler, H. N. (1989) The contractual theory of the corporation “ Geo. mason u.l. rev,, 11(4) 99-123.

- Chien, K.-F.; Wu, Z.-H.; Huang, S.-C. Identifying and assessing critical risk factors for BIM projects: Empirical study. Autom. Constr. 2014, 45, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, H.-Y.; Fan, S.-L.; Sutrisna, M.; Hsieh, S.-H.; Tsai, C.-M. Preliminary Contractual Framework for BIM-Enabled Projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2017, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circo, C. J. Contract theory and contract practice: Allocating design responsibility in the construction industry “Florida law review, (58) 561-638. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L. , Manion, L. and Morrison, K., (2018) Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Creswell, J.W. and Creswell, J.D., (2020) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approach. 5th edition. Sage publications.

- Dao, T.-N.; Chen, P.-H.; Nguyen, T.-Q. Critical Success Factors and a Contractual Framework for Construction Projects Adopting Building Information Modeling in Vietnam. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2020, 19, 85–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabseh, M. and Joo, M., (2021) October. Protecting BIM design intellectual property with blockchain: review and framework. In Proc. of the Conference CIB W78 (Vol. 2021, pp. 11-15).

- Dhakal, K. , (2022) NVivo. “Journal of the Medical Library Association, 110(2) 270-272.

- Ding, L.; Zhong, B.; Wu, S.; Luo, H. Construction risk knowledge management in BIM using ontology and semantic web technology. Saf. Sci. 2016, 87, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Hajj, C.; Montes, G.M.; Sleiman, S. Investigation of BIM Contractual Perspective in the MENA Construction Industry. 2023 Fifth International Conference on Advances in Computational Tools for Engineering Applications (ACTEA). LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, LebanonDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 104–108.

- Elnokaly, A.; Dogonyaro, I. Framework to assess connection of risk factors and management strategies in Building Information Modeling. Acad. Eng. 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enegbuma, W.I.; Aliagha, U.G.; Ali, K.N. Preliminary building information modelling adoption model in Malaysia. Constr. Innov. 2014, 14, 408–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feist, S.; Ferreira, B.; Leitao, A. Collaborative Algorithmic-based Building Information Modelling. CAADRIA 2017: Protocols, Flows, and Glitches. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, ChinaDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 613–622.

- Ganbat, T.; Chong, H.-Y.; Liao, P.-C.; Lee, C.-Y. A Cross-Systematic Review of Addressing Risks in Building Information Modelling-Enabled International Construction Projects. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2018, 26, 899–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M.C. An overview of benefits and challenges of building information modelling (BIM) adoption in UK residential projects. Constr. Innov. 2019, 19, 298–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contract theory and contract practice: Allocating design responsibility in the construction industry “Florida law review, (58) 561-638.

- Hartmann, T. and Fischer, M. (2008) Applications of BIM and Hurdles for Widespread Adoption of BIM 2007 AISC-ACCL e-Construction Roundtable Event Report “Centre for Integrated Facility Engineering, 1-18.

- Kivits, R.A.; Furneaux, C. BIM: Enabling Sustainability and Asset Management through Knowledge Management. Sci. World J. 2013, 2013, 983721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leavitt, H. J. (1964). “Applied organization change in industry: Structural, technical and human approaches.” New perspectives in organizational research, W. W. Cooper, H. J. Leavitt, and M. W. Shelly, eds.

- Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, Y.-P.; Huang, W.-T.; Hong, C.-C. Development of BIM Execution Plan for BIM Model Management during the Pre-Operation Phase: A Case Study. Buildings 2016, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblad, H. Black boxing BIM: the public client’s strategy in BIM implementation. Constr. Manag. Econ. 2018, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Peng, Y.; Shen, Q.; Li, H. Generic Model for Measuring Benefits of BIM as a Learning Tool in Construction Tasks. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2013, 139, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdian, A.; Jalal, M.P.; Roushan, T.Y. Contractual Risks of BIM Implementation and the Proposed Contract Form for DBB and DB Projects. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2023, 15, 06522003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ya’aCob, I.A.M.; Rahim, F.A.M.; Zainon, N. Risk in Implementing Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Malaysia Construction Industry: A Review.CONFERENCE NAME, LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, COUNTRYDATE OF CONFERENCE; p. 03002.

- Merschbrock, C.; Hosseini, M.R.; Martek, I.; Arashpour, M.; Mignone, G. Collaborative Role of Sociotechnical Components in BIM-Based Construction Networks in Two Hospitals. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erpay, M.Y.; Sertyesilisik, B. Preliminary checklist proposal for enhancing BIM-based construction project contracts. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2021, 26, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Aibinu, A.A.; Oraee, M. Risk Allocation and Mitigation Practices for Building Information Modeling: Addressing Legal and Contractual Risks Associated with Contract Documentation. J. Leg. Aff. Disput. Resolut. Eng. Constr. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilchian, S. , Sardrood, J.M., DarabPour, M. and Tafreshi, S.T., (2021) The Study of the Contracts of Building Information Model (BIM) and the Approach to its Contractual Framework Codification. “Amirkabir Journal of Civil Engineering, 53(8), pp.3239-3260.

- Nilchian, S.; Sardroud, J.M.; Darabpour, M.; Tafreshi, S.T. Features and Conditions of Building Information Modeling Contracts. Buildings 2022, 12, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oraee, M.; Hosseini, M.R.; Papadonikolaki, E.; Palliyaguru, R.; Arashpour, M. Collaboration in BIM-based construction networks: A bibliometric-qualitative literature review. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2017, 35, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, L.O.; Regan, M.; von Meding, J.; Ahmed, A.; Ebohon, O.J.; Elnokaly, A. Reducing waste to landfill in the UK: identifying impediments and critical solutions. World J. Sci. Technol. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 10, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabo, W. and Zahn, J. K. (2005) Building information modelling and legal issues. “The Construction Specifier, 58 (6) 18-19.

- Sackey, E.; Tuuli, M.; Dainty, A. Sociotechnical Systems Approach to BIM Implementation in a Multidisciplinary Construction Context. J. Manag. Eng. 2015, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, A.; Scott, R.E. Contract Theory and the Limits of Contract Law. Yale Law J. 2003, 113, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghizadeh, K.; Roushan, T.Y.; Alizadeh, M. Liability in BIM projects—Preliminary review results. Int. J. Arch. Comput. 2022, 20, 476–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, B. and Achenbach, M., (2023) Legal governance for BIM–Rights management and lawful data Use. In Life-Cycle of Structures and Infrastructure Systems (pp. 3292-3299). CRC Press.

- Winfield, M. , (2015) UK standard form contracts: Are they ‘BIM-enabled’.

- Zhao, X.; Feng, Y.; Pienaar, J.; O’Brien, D. Modelling paths of risks associated with BIM implementation in architectural, engineering and construction projects. Archit. Sci. Rev. 2017, 60, 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Kiviniemi, A.; Jones, S.W. A review of risk management through BIM and BIM-related technologies. Saf. Sci. 2017, 97, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Stakeholder | Recommendation | Knowledge & Innovation Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Construction Industry | Adopt the BIM-RBS Matrix during contract preparation and project planning. | Converts tacit legal/contractual risks into explicit knowledge, reducing disputes and enabling collaborative innovation. |

| Use the BIM-RBS–MS Nexus to guide tailored management strategies. | Integrates digital, legal, and organisational knowledge streams to enable effective innovation diffusion. | |

| Invest in training and capacity building for BIM managers, legal advisors, and project leaders. | Builds absorptive capacity to operationalise frameworks and embed innovation into daily practice. | |

| Policymakers & Standard-Setting Bodies | Integrate the BIM-RBS framework into BIM standards (e.g., ISO 19650, NEC, JCT, CIC). | Standardises risk knowledge, ensuring scalability and comparability across projects and countries. |

| Develop dispute resolution protocols tailored to BIM environments. | Provides knowledge-based mechanisms for fair and timely resolution, enhancing trust in BIM adoption. | |

| Promote incentives for collaborative risk-sharing (e.g., shared risk–reward). | Aligns stakeholder knowledge and interests, fostering organisational innovation and reducing adversarial practices. | |

| Research & Academia | Extend investigations into socio-organisational, eco-financial, and techno-organisational perspectives. | Expands the knowledge base by embedding multidisciplinary perspectives into innovation adoption. |

| Empirically test the BIM-RBS Matrix across jurisdictions and project scales. | Validates knowledge transferability, ensuring global relevance and adaptability. | |

| Advance theoretical development on the legal-contractual dimension in BIM adoption models. | Strengthens the knowledge foundations for innovation governance in construction and allied industries. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).