1. Introduction

One of the world’s most risk-prone industries is the construction industry [

1]. Among the various reasons for this are the industry’s critical role in meeting infrastructure needs across all activity sectors; the complex and ever-changing dynamics of construction, resulting in frequent cost overruns, delays, and failures to meet operational and quality standards; the vast network of interrelated actors in the industry; and other stochastic factors beyond human control [

2,

3]. Traditionally, the focus has been on managing risks at the project level, as individual projects are primary revenue sources [

4]. However, this narrow focus can lead to challenges such as a fragmented understanding of risks, limited transparency between projects, suboptimal resource distribution, and obstacles in fulfilling broader corporate strategies [

5,

6]. Organizations have recently undergone a major transformation in their risk management strategies, shifting toward a more holistic perspective [

7,

8]. Central to this evolution is enterprise risk management (ERM), which has garnered considerable attention on a global scale [

9]. According to the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission [

10], ERM is characterized as “

a process, carried out by an organization’s board of directors, management, and staff, that is integrated into strategy formulation and across the organization, aimed at identifying potential events that could impact the organization and managing risks in alignment with its risk appetite, thereby providing reasonable assurance for the achievement of organizational objectives”.

ERM is essential for driving sustainable development in the construction industry by identifying, measuring, and managing risks that impact long-term organizational success [

11,

12]. Effective ERM practices enhance economic efficiency, foster growth, and boost investor confidence [

13]. Given the complexity of construction projects, ERM is a crucial factor influencing business performance. However, as globalization, technological advancements, and evolving stakeholder expectations reshape the industry, construction firms must adapt their risk management strategies to remain competitive [

14]. While ERM is widely recognized for its role in managing project and operational risks, ensuring its own process is sustainable remains underexplored [

15]. Companies implement ERM to improve performance indicators, optimize decision-making, and minimize losses (Liu et al., 2011; Low et al., 2013). However, for ERM to deliver lasting value, it must be integrated into an organization’s long-term strategy, continuously improved, and adapted to changing environments. This shift towards Sustainable ERM (SERM) is not about managing sustainability-related risks but rather ensuring that ERM itself remains effective, agile, and resilient over time.

SERM enhances traditional ERM by broadening its scope and introducing a more holistic and forward-looking orientation to risk governance. Unlike conventional ERM, which typically centers on financial and operational risk mitigation, SERM incorporates long-term sustainability considerations, enabling organizations to respond to emerging environmental, social, and governance (ESG) challenges [

13]. According to [

16], SERM is the process of identifying, assessing, and prioritizing threats to cost-effective organizational performance, while adopting long-term initiatives to address and mitigate these risks. This practice ensures that organizations not only manage immediate risks but also maintain resilience and sustainability over time [

17]. It encourages organizations to consider the environmental and social consequences of their actions, promoting responsible practices and minimizing negative externalities [

16]. Recent empirical research such as the work of Bashir et al. [

18], Dewi et al. [

19] and Jegan Joseph Jerome et al. [

20] confirms that SERM implementation in construction firms is positively associated with enhanced competitive advantage, improved sustainability performance, and strengthened stakeholder relationships, reinforcing its value as a transformative tool in high-risk project environments.

This relevance is magnified in the construction sector, where the convergence of high-risk project environments and long-term sustainability pressures creates unique operational challenges. In the United Arab Emirates (UAE), the construction industry is a central pillar of economic development, yet it faces persistent exposure to uncertainties ranging from regulatory fluctuations to environmental and social liabilities [

21]. Despite a general awareness of risk, many firms continue to apply fragmented approaches that neglect the broader sustainability implications of their activities. Risk management practices in UAE construction projects often lack methodological depth, limiting their capacity to anticipate and mitigate systemic project risks [

22]. Integrating SERM in the construction of projects is essential to mitigate these negative impacts and enhance the long-term viability of the industry. The adoption of SERM practices enables construction companies in the UAE to proactively manage risks related to environmental regulations, resource scarcity, and growing social expectations, while also creating opportunities for innovation and improved efficiency [

23].

Despite extensive research on ERM across industries manufacturing [

24], banking [

25], construction [

6] and healthcare [

26], there is little focus on the critical success factors (CSFs) driving SERM implementation, particularly in the UAE construction sector. The UAE presents a unique setting due to its rapid urbanization, regulatory developments, and increasing emphasis on structured risk management in construction. Understanding the CSFs of SERM in this context can provide valuable insights into how organizations can strengthen ERM frameworks to support long-term business continuity and industry resilience as highlighted Hristov et al. [

27]. This forms the central motivation of the current study, which is positioned to fill this critical gap by identifying the organizational elements that underpin effective and enduring SERM in the UAE’s construction environment.

Prior research on risk management in the construction industry has primarily focused on traditional ERM frameworks, risk identification tools, and their influence on operational or financial performance [

28,

29,

30]. These studies have contributed to a foundational understanding of how construction firms manage risks, yet they tend to concentrate on procedural aspects or firm-level outcomes, often excluding broader sustainability dimensions. More recent work has emphasized the need for integrated approaches that link risk governance with long-term environmental and social goals, yet empirical investigation into such approaches, particularly in project-based contexts, remains limited [

16,

31]. It has been noted that the CSFs that enable or constrain the effective integration of SERM in construction are underexplored, particularly in the context of emerging economies. This gap has limited the operational relevance of existing ERM models and their ability to support sustainability-aligned project delivery. As a result, there is a need for research that identifies and contextualizes the key enablers of SERM implementation. This study responds to that gap by focusing on the construction industry in the UAE. To this end, this research aims to investigate the CSFs that enable effective SERM integration in the UAE construction industry. The objectives are to: (1) identify the CSFs that matter most to SERM in construction settings; (2) assess the significance of these factors for long-term business continuity and resilience; (3) group the factors into clear dimensions that reflect the main areas of SERM; and (4) explore how these factors collectively contribute to strengthening enterprise-wide risk management frameworks in the context of the UAE construction industry.

1.1. Contributions

This research contribution can be summarized as follows. First, this research identifies and categorizes the critical success factors essential for the effective implementation of SERM in the UAE construction sector. While existing literature has emphasized the importance of identifying CSFs for enterprise risk practices, particularly in sectors with high volatility and complex stakeholder networks [

5,

32], the integration of sustainability principles into ERM frameworks within the Middle Eastern construction context remains underexplored. This research addresses that gap by focusing on sector-specific characteristics such as rapid urbanization, regulatory evolution, and economic diversification unique to the UAE, thereby contributing new empirical knowledge relevant to both regional and international audiences. This approach aligns with calls for more context-specific analyses in construction project management [

33].

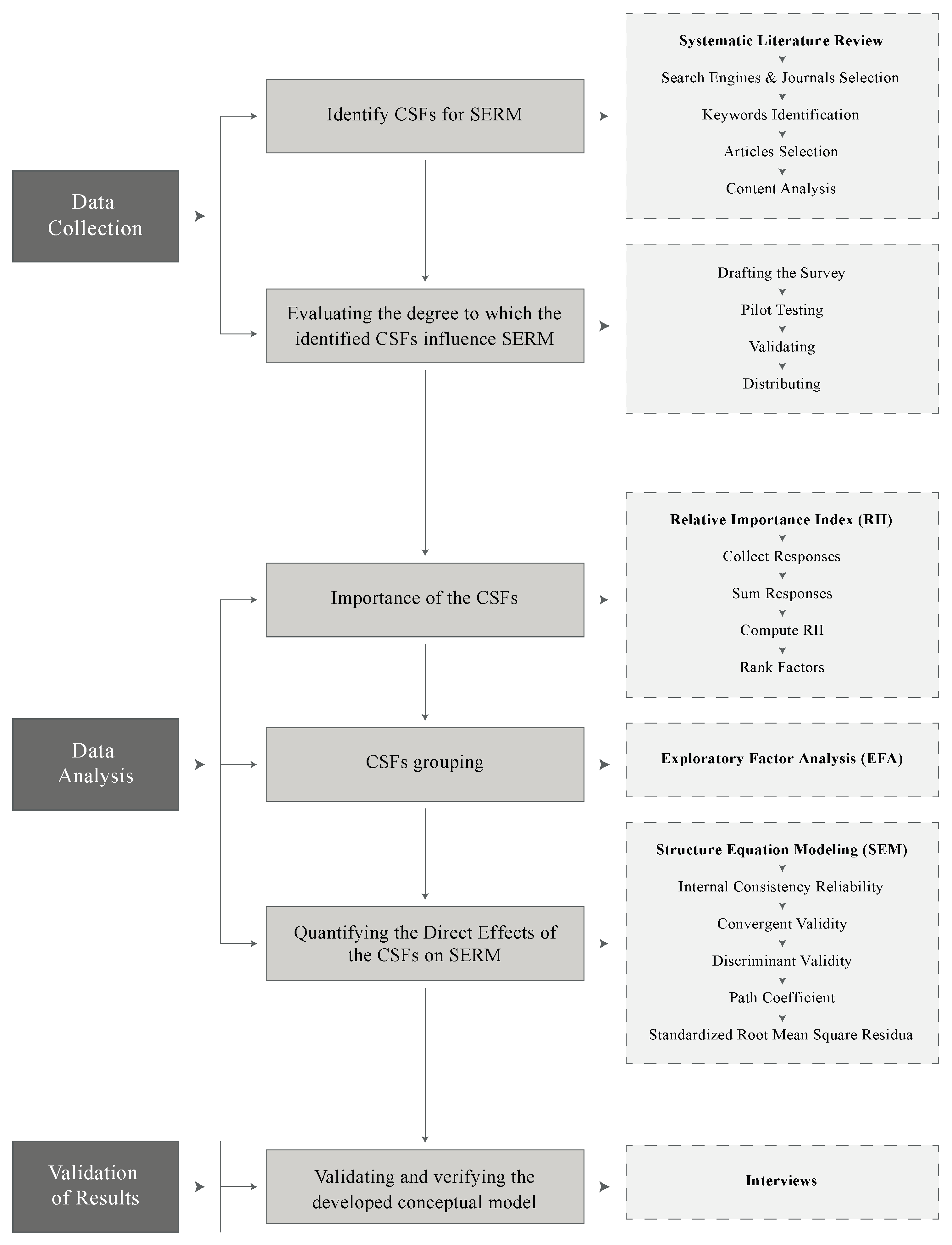

Second, the study applies a multi-method approach, including a Systematic Literature Review, Relative Importance Index, Exploratory Factor Analysis, and Structural Equation Modeling, to examine the structure and influence of SERM CSFs. Prior research has validated the use of combined statistical methodologies for risk factor prioritization and model development [

34,

35]. This comprehensive design enables a layered investigation; first identifying CSFs through literature synthesis, then validating their significance via industry data, and finally testing causal pathways using SEM. This contributes methodologically by refining how empirical models can be used to capture interdependencies in construction risk governance.

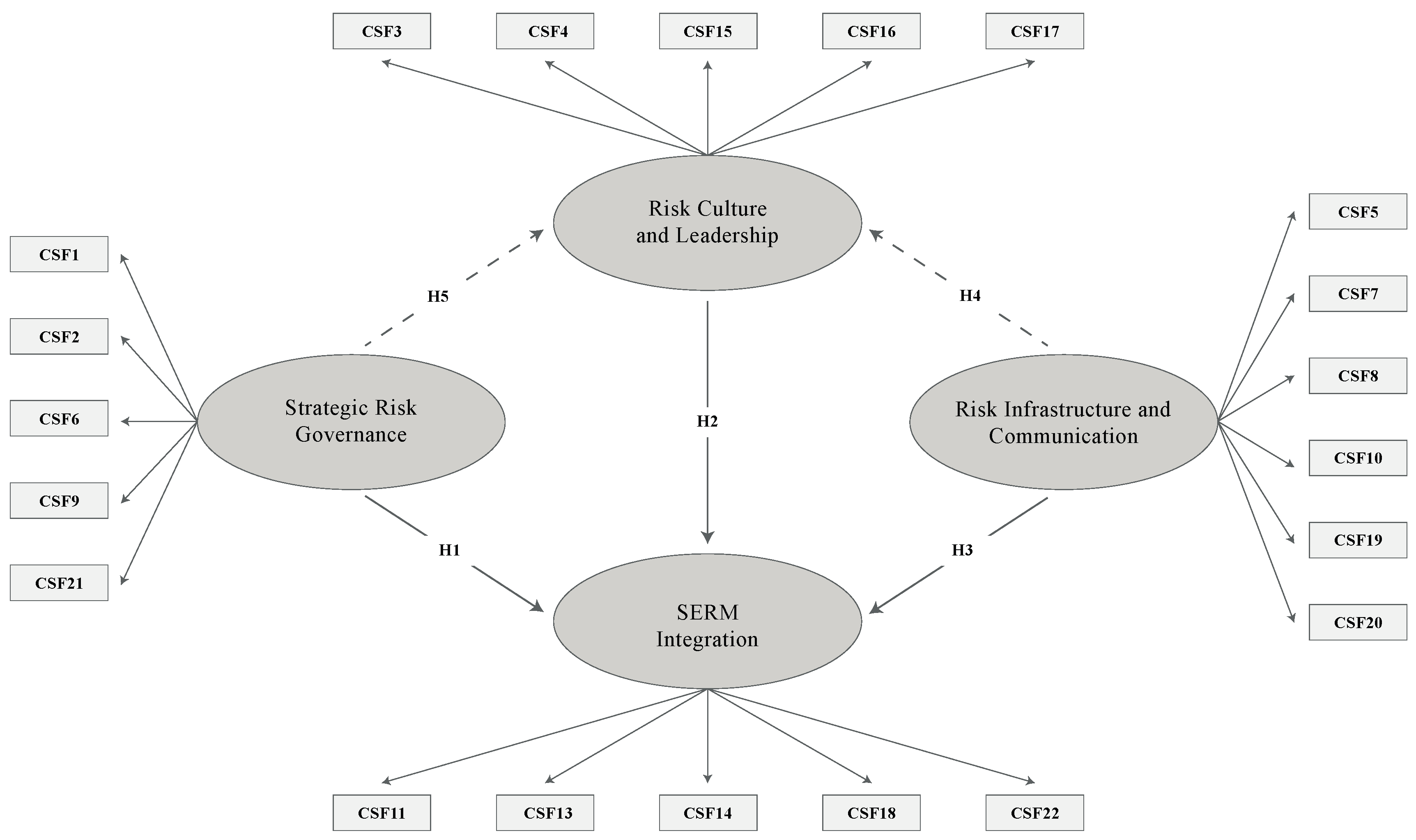

Third, the research empirically validates that strategic risk governance acts as a foundational enabler, positively impacting organizational risk culture and leadership, which in turn influence the robustness of risk infrastructure and communication systems. These interlinkages are crucial for facilitating seamless regulatory and process integration within construction firms [

36]. The findings support the conceptual alignment with COSO’s ERM framework while extending its applicability to sustainable risk practices [

10].

Fourth, the study introduces a validated SERM model that supports long-term organizational resilience and competitive advantage in high-risk construction environments. This model advances theoretical discourse by contextualizing sustainability not only as an environmental consideration but as a structural requirement for enterprise-wide risk strategy. It aligns with emerging perspectives that call for resilience and agility in risk management as strategic imperatives rather than operational afterthoughts [

37]. The model provides construction organizations with a structured pathway to integrate sustainability into risk governance, helping transition ERM from compliance-oriented to strategy-driven frameworks.

Fifth, the study offers actionable insights for industry professionals and policymakers by outlining how specific organizational capabilities such as governance, leadership, and communication can be leveraged to enhance regulatory integration and operational resilience. This has practical implications for reforming policy and institutional mechanisms in the UAE and comparable economies. These insights are intended to guide future industry initiatives aimed at embedding sustainability within core risk management practices, thereby improving project outcomes and long-term viability.

1.2. Knowledge Gap Identification

Despite growing scholarly attention to risk management for sustainability in construction, the literature reveals persistent gaps. For example, Guan et al. [

38] examined interdependencies among risks in green building projects via interpretive structural modeling, but this project-level analysis did not integrate sustainability considerations into a broader ERM framework. Similarly, Qazi et al. [

39] introduced a Monte Carlo simulation-based process to prioritize sustainability-related construction risks in the UAE; however, their focus on isolated project risk prioritization fails to bridge into enterprise-wide sustainable risk management. Erdenekhuu et al. [

40] proposed a method combining Monte Carlo and AHP to assess critical environmental risk factors in construction activities, yet this approach remains confined to the environmental dimension at the project level and does not model how multiple success factors interrelate within an organization’s risk landscape. Likewise, Kassem [

36] used PLS-SEM to model key risk factors affecting project success in oil and gas construction, capturing static cause–effect relationships but without addressing sustainability performance or dynamic enterprise contexts. Furthermore, Prakash and Ambekar [

6] employed a Delphi-driven ISM–MICMAC framework to map hierarchical ERM barriers in Indian construction firmsemerald.com, yet their barrier-centric analysis omitted sustainability considerations and offered no guidance for enterprise-level SERM integration. Collectively, these studies demonstrate limited integration of ERM and sustainability at the enterprise level. This clear knowledge gap in enterprise wide SERM integration indicates the need for research that synthesizes sustainability and risk management beyond the project scope. The present study fills this gap by adopting a structured, multi-method approach that integrates sustainability into ERM at the enterprise level, models the complex interdependencies among CSFs, and is tailored to the dynamic conditions of the UAE construction industry.

Table 1 summarizes the most recent and relevant studies, highlighting their focus, findings, and the specific gaps that the current research seeks to fill.

The paper rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the research methodology used in the study, while

Section 3 presents the results and analysis.

Section 4 offers a discussion on the key findings, and

Section 5 concludes by summarizing the main insights drawn from the research.

5. Conclusions

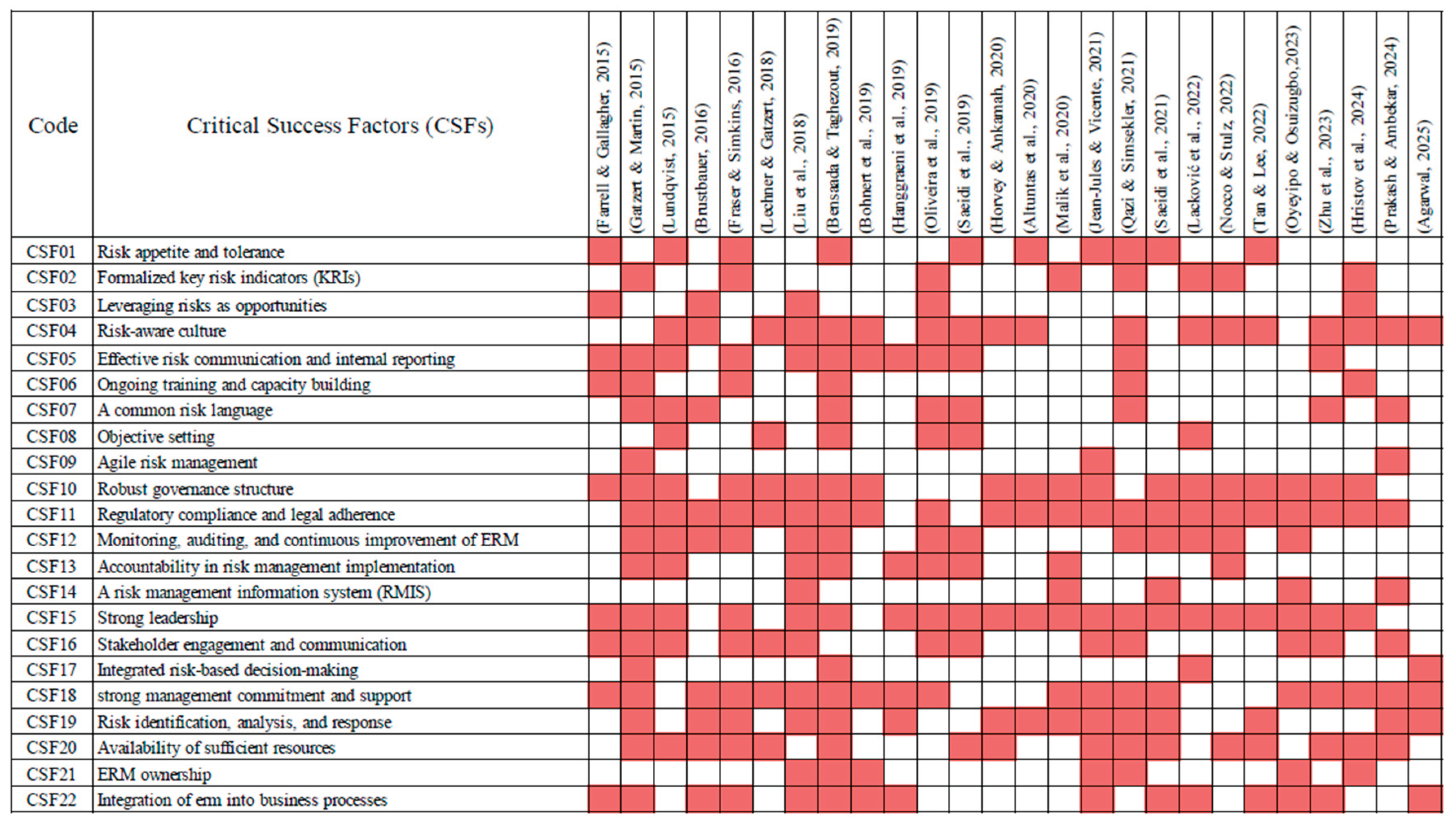

This study identified the CSFs for SERM in the UAE construction sector and examined their interrelationships. It extended beyond traditional sustainability perspectives by emphasizing the development of ERM systems that remain resilient and adaptable throughout the project lifecycle. The SLR identified 26 relevant studies, leading to the selection of 22 CSFs. These factors were assessed through a structured questionnaire survey of 106 professionals and key stakeholders in the UAE construction industry. The RII analysis showed that all CSFs ranked highly in both the public and private sectors, with the top-ranked factors representing the most crucial elements for successful SERM implementation. EFA grouped these CSFs into four key categories: strategic risk governance, risk culture and leadership, regulatory and process integration, and risk infrastructure and communication. These categories and their interconnections formed a conceptual framework outlining the core areas of SERM in the UAE construction industry. The PLS-SEM analysis confirmed the acceptance of all hypotheses, while expert validation through interviews further reinforced the framework’s relevance. This proposed framework offers a structured understanding of SERM activities and their interrelationships within the UAE construction industry, providing a clearer approach to effective risk management in the sector.

5.1. Theoretical Implications

The outcomes of this study offer both theoretical and practical value. Theoretically, by systematically identifying and categorizing the CSFs that influence SERM implementation, this research enriches existing literature and provides a nuanced understanding of how sustainability considerations integrate with traditional risk management frameworks. This study contributes to theory by emphasizing the internal sustainability of ERM processes themselves, shifting the focus from managing external sustainability risks to sustaining the functionality, relevance, and adaptability of ERM frameworks over time. By clarifying the role of governance, leadership, infrastructure, communication, and regulatory alignment in sustaining ERM, the research provides a basis for future theoretical models that treat SERM as a system of interdependent organizational enablers rather than a compliance function. This reframing invites further scholarly investigation into how these enablers interact under different regulatory and institutional conditions, especially in emerging economies like the UAE. This enhanced perspective lays a robust foundation for future studies, encouraging scholars to delve deeper into SERM dynamics across various sectors. Such exploration is pivotal for developing more resilient and adaptive risk management systems globally.

5.2. Practical Implications

For practitioners, the insights from this study serve as a strategic guide for construction firms in the UAE and potentially in other regions. Pinpointing and analyzing the CSFs helps top management recognize the essential components that facilitate successful SERM adoption. This awareness enables the allocation of necessary resources and fosters executive commitment. The findings can support leadership in reinforcing a proactive risk culture, ensuring that sustainability becomes embedded in decision-making, communication structures, and governance processes. They also help organizations assess the strength of their internal risk environment and identify where adjustments are needed such as improving cross-departmental communication or aligning leadership with regulatory expectations. While the study is contextualized within the UAE, its findings offer a valuable benchmark for construction companies worldwide aiming to embed sustainability into their risk management practices, thereby bolstering industry-wide resilience.

5.3. Future work

Future research could benefit from incorporating project-based case studies alongside expert interviews and surveys to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the CSFs influencing the successful implementation of SERM. Expanding the assessment model to include additional constructs and performance indicators may further refine its applicability. Longitudinal studies could offer valuable insights into how organizations strengthen key CSFs over time and assess the effectiveness of mitigation strategies in dynamic environments. Developing and validating advanced quantitative models that incorporate emerging analytical techniques, such as machine learning, could enhance risk prediction and management capabilities. Testing the proposed model across different geographical regions would help evaluate its generalizability and robustness. Finally, investigating the role of advanced digital technologies in optimizing key CSFs could offer innovative solutions for advancing SERM practices.