1. Introduction

The construction industry is considered a major growth industry globally and construction projects are characterised by interdisciplinary and multistep processes with excessive portion of global energy consumption and carbon emissions (Kadume and Naji, 2021; Khoshfetrat et al. 2022; Duran and Elnokly 2024). According to Kozlovska et al. (2021), we live in an era of change, not measured in years, but days or even hours, due to digital revolution pushing towards all aspects of our life at a faster pace and advancing the industry towards a more innovative, collaborative, and technological approach is essential (Zairul and Zaremohzzabieh, 2023). The adoption of new digital technologies for advanced information and communication allows capturing, displaying, processing, collaborating and storing information (Kozlovska et al. 2021). An example of such modern digital technology is Building Information Modelling (BIM). Currently, BIM technology is widely used and is becoming increasingly prevalent in the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry (Liu et al., 2025; Li et al.,2025). It is the process of creating and managing information using an intelligent model and a cloud platform, integrating multidisciplinary data for built asset throughout its lifecycle (Ahmad et al., 2025). BIM is a process and modelling technology for creating, communicating, analysing digital information models during the life cycle of a construction project (Ismail et al., 2025). BIM application extends three dimensional (3D) geometric data into a multi-dimensional information model to achieve specific functions (Li et al., 2025). Such as a central information repository to provide comprehensive, reliable, and easily accessible information to stakeholders, and information integration platform for managing building operation and maintenance (Li et al., 2025; Pav’on et al., 2025; Liu et al., 2025). The widespread application of BIM technology yielded several benefits in the construction industry (Huan et al., 2025), such as improving reliability, enhancing data availability as a potential solution for reducing time in carbon emission assessments (Li et al., 2025). Including quality control, cost management, scheduling, clash detection, and simulations through 3D data models enhancing efficiency and transparency (He et al., 2025; Ahmad et al., 2025). The extraordinary scalability of BIM integrated with advanced multiple technologies plays a pivotal role throughout the planning, design, construction, operation and maintenance of a project’s entire lifecycle (Liu et al., 2025). For example, Liu et al., (2025) merge BIM with generative AI technologies for intelligent structural design pipeline. BIM integrated with Internet of Things and cloud computing to develop Bim-based Digital Twin to overpass BIM implementation barriers (Pav’on et al., 2025; Huan et al., 2025). Within that context there are various associated risks implementing BIM due to increasing complexity of the construction industry and the advances in computer technology (Ismail et al., 2025). Such important implementation barriers and challenges are initial investment in hardware and software, stakeholder coordination issues, initial BIM and programming skills or low data interoperability (Pav’on et al., 2025; Elshabshiri et al., 2025); changes in traditional working methods with more capital investment at the early stages hinders BIM application in property management (Huan et al., 2025); Applying theoretical knowledge to practical real-life scenarios is challenging and adapting legal frameworks to accommodate new technologies and the management of intellectual property rights within these digital environment still remain a significant obstacle. Additionally, the necessity for systemic cultural change and workforce upskilling adapting to new technological demands further complicates the implementation process (Elshabshiri et al., 2025). In addition to that the construction industry is still ranked amongst the highest in terms of risk exposure (Ranjbar et al. 2021; Yasser et al., 2023; Okika et al., 2024), because risk is present ubiquitously in every aspect of our everyday life. Hence an inherent element in every aspect of the construction industry that is hard to avoid (Szymański, 2017), and building safety has always been one of the most important pillars of building construction processes (Mirzaei-Zohan et al., 2023). However, incorporating the implications of these uncertainties and risks is a key feature of management for construction companies in the industry. In other words, an effective risk management is understood to be valuable in managing construction projects more accurately with consistency to achieve optimum project performance (Ranjbar et al. 2021; Chenya et al. 2022). Hence, risk management is an essential part of construction management, which is a process of gathering information for analysis to make informed decisions (Chenya et al. 2022). Risk is defined as an event with known uncertainty, usually measured in terms of likelihood and severity. It has the potential to significantly affect project outcomes such as time, cost and quality, with both negative and positive impacts on project objectives (Mat Ya’acob et al. 2018; Ahmad et al., 2025). Moreover, risk management refers to a series of actions taken to mitigate the risk (Górecki, 2018). It is essential for decision-making and integrated into the structure, program, operations, and strategic activities of an organisation project levels. By virtue, risk vary in nature depending on the project type, as a result numerous studies meticulously defined risk management, as a process of planning, identifying, analysing, treatment, monitoring project risks and review (Lee et al. 2019; Zou et al. 2017; Mat Ya’acob et al. 2018; Ahmad et al., 2025). Nevertheless, risk identification is the first stage in the process (Mat Ya’acob et al. 2018), and risk categorisation which structures the diverse nature of risks, has been widely accepted as an integral part of risk identification (Zhao et al. 2017). Various scholars have adopted various risks identification techniques such as expert interview, document review, fault tree analysis, risk map and risk breakdown structure (RBS) etc. (Ganbat et al. 2018; Zou et al. 2016). However, the scope of this study is limited to BIM and RBS to develop a risk database, because RBS is highly ranked in the representation of risk factors in events and projects. It is an easily updatable framework that is open and flexible, which can offer a global view of risk exposure (Zou et al. 2016). Researchers categorise risks as internal and external risk, social risks covering community engagement, environmental risks involve climate conditions, financial risks inaccuracies in cost and technical risks such as design flaws etc. from a single dimensional perspective (Ahmad et al., 2025). Hence, the scope of this study extends to the amalgamated dimensional perspective specifically the techno-organisational aspect. Therefore, for a successful BIM implementation, identifying risks early will enable industry professionals to plan and better respond to these potential risk factors via RBS (Yanda et al. 2019), and effective risk management is vital to mitigate these risks (Ahmad et al., 2025).

There is considerable literature that is focused on BIM benefits with less consideration of the problematic implementation process across the construction industry. What is lacking are management strategies to mitigate these risks. For example, Alreshidi et al. (2018) study on cloud-based BIM governance solutions to facilitate team collaboration in construction projects identified some socio-organisational barriers to BIM adoption, which suggest there is a significant knowledge gap in the literature with non from a techno-organisational perspective. Zou et al. (2016) developed a tailored RBS and Ahmad et al., (2025) discussed risk classification such as environmental, economic and social risks from a single dimensional perspective. Those studies, however, failed to extend the scope to the amalgamated dimensional aspect. Elshabshiri et al., (2025) discussed challenges and barriers in advancing BIM and DT technology and suggest establishing universal standards for data interoperability and security is crucial to overcome this barrier. These scholars have consistently highlighted the continual problematic implementation of the technology and inherent risk in the construction industry even though a much higher dimension and levels within BIM have been reached. However, no research was conducted on management strategies to mitigate these risks. Recognising this knowledge gab, this study delves into the literature relating to the techno-organisational aspect describing BIM based tools implementation from a technical and organisational dimension. For example, Hartmann et al. (2012) suggested that various project practitioners practise formal critical path scheduling techniques for estimating project duration. Conversely, they structure cost estimates into cost categories using work breakdown structures relating to the physical project work. However, in BIM practical settings the approach by technology-pull implementation perspectives that is focused on aligning existing BIM based tools with the current work practices in organisations might balance the prevailing technology-push implementation perspectives (such as UK government BIM mandate) within the construction industry. This suggests that aligning an organisation with technology depends on understanding the project management methods that guide the operation of a project team and aligning the existing functionality of BIM-based tools with these methods (Hartmann et al. 2012). Considering that the construction industry is fragmented, likewise introducing innovative technology such as BIM is fragmented (Zhao et al. 2018). As a consequence, Matthews et al. (2018) suggest the successful implementation of BIM involves moving away from fragmented roles. Contrarily, these risks will keep evolving as Hooper and Ekholm (2012) suggest BIM project delivery remains both a practical and a theoretical problem due to new design processes and procedures emerging. This is because, as technology advances with new models, new issues will inevitably arise. It is not just about switching tools but also about adapting to new work processes (Tomek and Matejka, 2014; Ku, DDES, and Taiebat, 2011; Azhar, 2011; Dossick and Neff, 2010). Moreover, BIM should not be understood merely as a digital tool; it encompasses vast amounts of data and information, which also introduce risks associated with the misinterpretation of BIM among AEC professionals. Hence, Beach et al. (2017) suggests the fragmentation of BIM data, which is problematic can be resolved by providing a transparent BIM coordination framework that represents the fragmented BIM data as a single distributed data model. Additionally, Mahamadu et al. (2018) recommend that functional coupling of the fragmented construction organisations into an integrated project delivery team(s) can be a solution for the lack of data integration between stakeholders. The COBie standard enables stakeholders to systematically organise maintenance information in BIM addressing information losses (Huan et al., 2025). BIM protocols alignment with ISO standards is one of the best ways to achieve and provide a structured well-defined guidance that clarifies, simplifies, and organises each process throughout the project lifecycle (Ahmad et al., 2025). Notably, mitigating strategies were limited with regard to the identified risk factors in this category due to lack of reference materials indicating a knowledge gap in this domain. Thus, a comprehensive study of BIM’s practical applications in construction is necessary to fully explore risk factors and management strategies. Therefore, the goal is to address the problem using an integrative review method to identify and assess the magnitude of the risk factors and then align appropriate management strategies. The following objectives seeks to implement the risk management process by: first, identify and categorise the risk factors via risk breakdown structure; Secondly, assess the severity of the risk factors; Thirdly, link management strategies to the identified risk factors; finally, assess and interpret the evidence, drawing on the views and experience of these professionals.

This paper is structured as follows: It presents a comprehensive integrative review encompassing key domains of BIM and other Information Technology (IT)-related studies intertwined with BIM. This review scrutinises evolving risk factors inherent in the technology’s implementation. Then critically examines the existing body of BIM literature and its intersection with risk management, rationalising the research problem that serves as the focal point of this study. Additionally, encompassing the theoretical framework that will guide the study. Moving forward, section two outlines the methodology, reporting on the paper retrieval process, detailing the research design, and categorising risks systematically from a techno-organisational perspective, and discussing the online survey strategy. Section three provides a meticulous account of the study’s results, and a comprehensive analysis of these findings. In section four, the paper discusses the practical implications, and conscientiously delineates its limitations. The concluding section synthesises the research study, drawing attention to its broader impact and applicability. It culminates with well-founded recommendations that not only encapsulate the direction for future studies but also emphasise the significance of the research’s contributions to the field.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

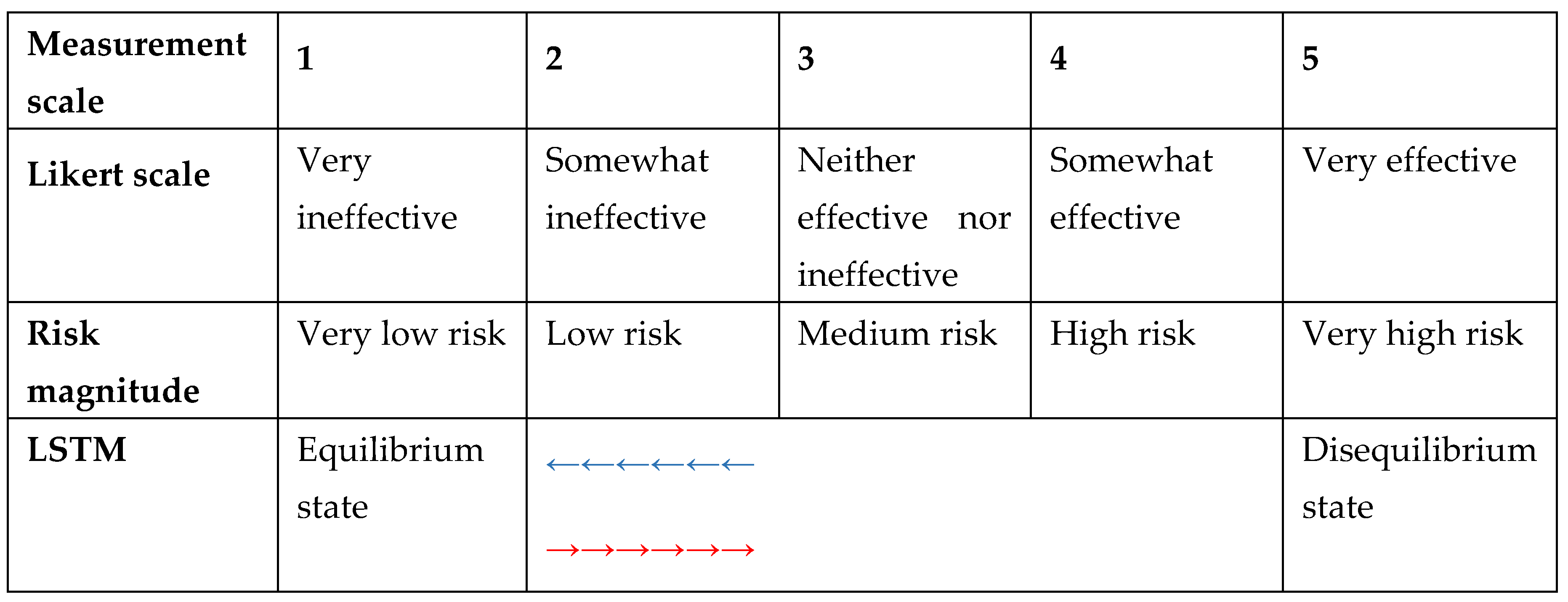

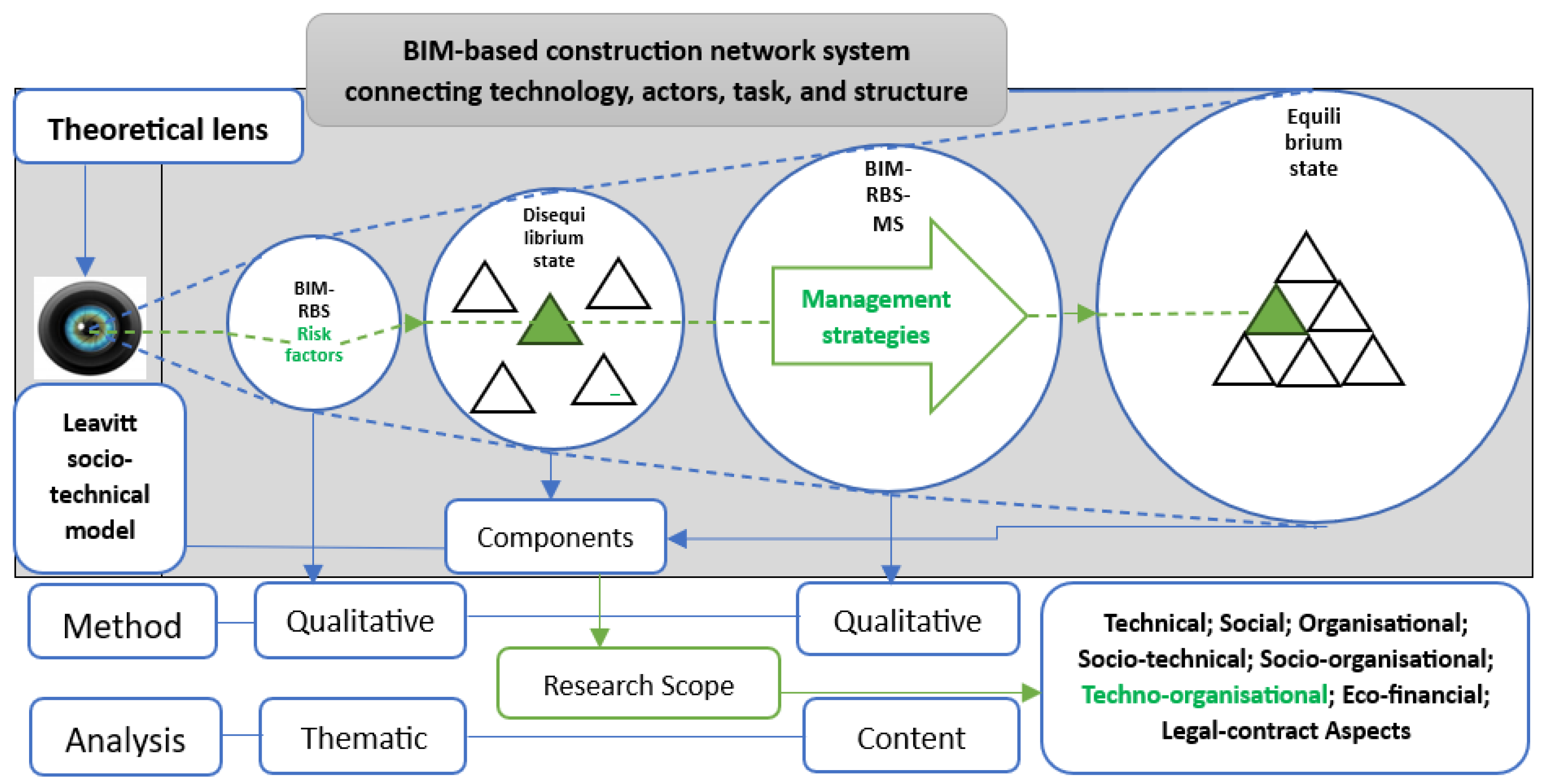

BIM implementation is a combination of information technology (IT) in a social environment that requires an organisation culture change. Therefore, its success in organisations depends not only on technical issues but also on social issues (Maskil-Leitan and Reychav, 2018). Hence, to examine this integration from a techno-organisational perspective requires a theoretical framework and means of evaluation for a successful BIM implementation by AEC professionals. Theories act as a bridge between variables, while a theoretical lens guides a study (Creswell, 2003: Khosrowshahi and Arayici, 2012). There are various theoretical models and frameworks for the design and analysis of BIM studies from a techno-organisational perspective. For example, Technology Organisation Environment Theory, DeLone and McLean IS Success Model (2003) and Leavitt Socio-technical Model (LSTM) etc. (Elnokaly and Dogonyaro, 2024). The Leavitt’s model comprises of four components tightly connected to each other (i.e., technology, actors, task, and structure). Merschbrock et al. (2018) applied the model to investigate collaboration in BIM-based construction networks (BbCNs) (i.e., BbCNs is a BIM system that connects technology, actors, task, and structure in BIM-enabled projects). They extended the model by including new components that act in synergy to achieve a balance in socio-technical systems. Therefore, the proposed theoretical framework for this particular paper was developed by Elnokaly and Dogonyaro (2024) perceived as the “blueprint” of this research enquiry serving as a guide. It is the structure that summarizes concepts and theories, and supports them within a research study (Kivunja, 2018; Grant and Osanloo, 2014). The blueprint is suitable for this study because it encompasses the extended version of the sociotechnical theory known as the Leavitt Socio-technical Model (LSTM) developed by Leavitt, H. J. (1964). In Sackey et al. (2014), the study utilizes the model to examine the BIM implementation process within an organisation in relation to the sociotechnical framework. Their findings suggest that a complex and interrelated set of incidents, events, and gaps emerged, threatening the stability of organisational norms and work processes. This indicates extending the model to include additional components in developing a framework to examine all the aspects is beneficial. Hence, the Leavitt sociotechnical model is a suitable theoretical lens for this study, as its underlying principles closely reflect the working nature of BIM systems and are capable of explaining the challenges of modern sociotechnical systems (STSs). Its explanatory power expands to include new components, producing a modified model that better reflects BIM-related systems (Sackey et al. 2014; Oraee et al. 2017; Elnokaly and Dogonyaro 2024). Therefore, an extended version of the Leavitt sociotechnical model, incorporating BIM-RBS risk factors and BIM-RBS-MS management strategies developed by Elnokaly and Dogonyaro (2024), will provide the theoretical basis for examining all categories while limiting the scope to the techno-organisational dimension. This is because the fundamental principle enacted with the model states that all the components are highly interrelated, and the system is in a state of equilibrium. Any event that causes a change in the system is an incident (i.e., risk factor). These incidents shift the system into a state of disequilibrium and is determined by the boundaries of the deep structure representing the risk magnitude. Therefore, an intervention is required (i.e., management strategy) to move the system back to a new equilibrium state (Merschbrock et al. 2018; Oraee et al. 2017; Elnokaly and Dogonyaro 2024).

Figure 1 displays the developed theoretical framework by Elnokaly and Dogonyaro (2024) and its application to this study.

2. Methodology

This section outlines the materials and methods used to assess BIM implementation risks and establish management strategies. It covers the research design, inquiry procedures, and data collection methods (i.e., primary and secondary data) suitable for analysis and interpretation to achieve the study’s objectives.

Bibliometric analysis identifies key trends, collaborations, and research patterns, offering an overview of the body of knowledge. Meanwhile, an integrative review—a flexible and holistic approach distinct from a systematic review—examines a broad range of sources, including various study designs, methodologies, and literature types (Klein and Müller, 2020). A systematic literature review, on the other hand, delves deeper into challenges, gaps, and opportunities in the field (Ganbat et al., 2019; Ganbat et al., 2018; Succar et al., 2012; Elshabshiri et al., 2025).

To analyse the intersection of the technical and organisational aspects, this study adopts an integrative review approach following a systematic process. This method enables the synthesis and structuring of knowledge, facilitating its application in practice by AEC professionals—particularly in risk evaluation, management strategies, and identifying key considerations for BIM implementation. The research design is presented next.

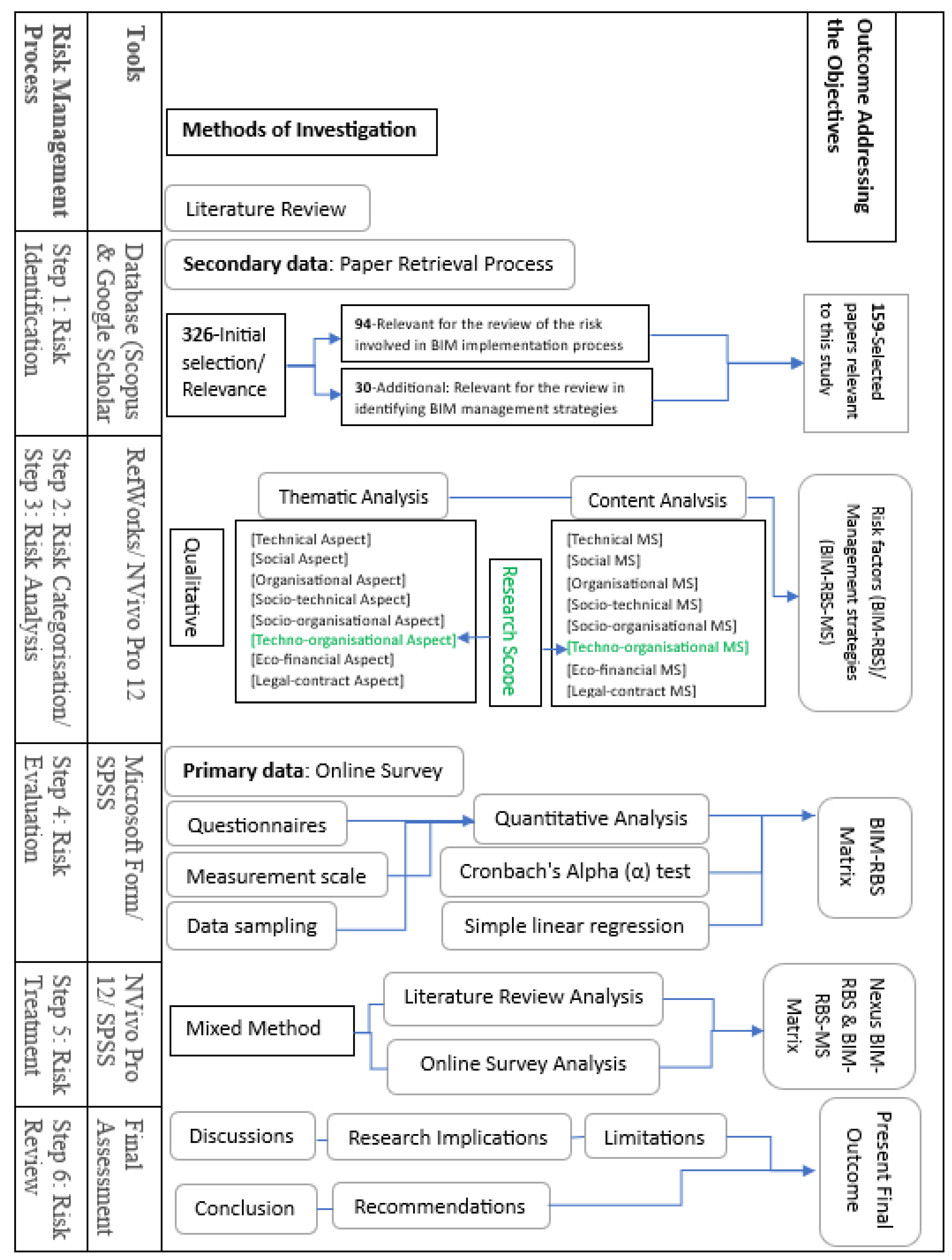

2.1. Research Design

Research design refers to a strategic plan when conducting research outlining the methods and procedure for data collection and analysis in relation to the study’s objectives (Akhtar, 2016). In this study, the research design aligns with the risk management process as illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.2. Paper Retrieval Process (Step 1-3)

Database: Journal articles and conference papers were retrieved from Scopus and Google Scholar as they provide extensive coverage of multidisciplinary scientific literature (Zhao et al. 2017; Oraee et al. 2017).

Search strategy: In Scopus three sets of keyword combinations were used for risk identification by triangulating “Building information modelling” and “risk” and “management”. For management strategies the terms “Risk management” and “management strategies” and “BIM” or “Building Information Modelling” were applied. On Google scholar the full research topic was entered into the search engine. Adequately, the search covered publications from 2000 to 2025.

Article selection criteria: A total of 326 English language publications were initially downloaded. After screening for relevance—excluding non-English papers and those unrelated to the research focus - 94 articles were selected for risk identification and 30 for risk management strategies totalling 124 relevant articles for this study.

-

Relevant Tools

RefWorks: Relevant articles were saved to this reference management program enabling the convenient elimination of duplicates.

NVivo 12 Pro software: enabled risk identification and analysis for categories via coding because a similar approach was successfully conducted and validated by Aksenova et al. (2018) and Dhakal (2022).

Analysis

Thematic analysis: Thematic analysis was used to extract risk factors from relevant papers, recognizing that different fields describe risks using various terms such as “threat,” “hazard,” “uncertainty,” “challenge,” and “barriers” (Zou et al., 2017). An open coding process facilitated categorization, a well-established qualitative analysis method that emphasizes comparison, similarity, and contrast against existing models to frame interpretations.

Identified risks were classified based on prior scholars’ categorization techniques but were modified using a risk breakdown structure (RBS) from a theoretical perspective (

Figure 1). This approach contributed to developing “BIM-RBS” to achieve the study’s first objective (Poirier et al., 2017; Blay et al., 2019; Elnokaly and Dogonyaro, 2024).

Content analysis: Content analysis was used to extract and analyse management strategies linked to identified risk factors, focusing on key areas such as previous experience, knowledge reuse, techniques, methods, and procedures (Ding et al., 2016; Oyedele et al., 2013; Enegbuma et al., 2014).

Research Framework

Figure 2.

Research Design (Author’s own).

Figure 2.

Research Design (Author’s own).

2.3. Online Survey (Step 4)

A survey was conducted to achieve the second objective—establishing the statistical relationship between BIM-RBS and BIM-RBS-MS, determining the magnitude of risk factors, and ensuring high representativeness for precise results. Sampling and questionnaire design are key aspects of this survey, as detailed below.

Table 1.

Criteria for questionnaire development.

Table 1.

Criteria for questionnaire development.

| Themes |

Risk Factors |

Management Strategies |

| A |

Difficult to implement due to fragmented structure of construction industry and also BIM |

Knowledge gap |

| B |

Lack of strategies for integration and exchanging information among BIM components |

Knowledge gap |

| C |

Lack of alignment between the IT strategy and organisational strategy |

Knowledge gap |

| D |

Privacy constraints associated with external storage |

Knowledge gap |

| E |

Lack of data integration between stakeholders |

Functional coupling of fragmented organisations into an integrated project delivery team(s) |

| F |

Technological interface among programs within organisations |

Application programming interface (API) |

| G |

Challenges controlling transactions in multi-model collaborative environment |

Version control system controls BIM data repository transactions in a collaborative environment |

Figure 3.

5-point Likert scale measurement aligned with LSTM (Author’s own).

Figure 3.

5-point Likert scale measurement aligned with LSTM (Author’s own).

Data Sampling: Defining a specific sample frame was challenging due to geographic restrictions, which could limit valuable insights. To enhance generalizability, AEC professionals were targeted through BIM groups on LinkedIn, where they were invited to participate. The survey was distributed via Microsoft Forms, receiving 60 responses.

-

Relevant Tools

Microsoft Forms: An online tool for creating and distributing surveys.

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS): Used for numerical data analysis. The techniques employed for quantitative analysis are detailed below.

Analysis

Variables and Scales: Nominal (N) Gender and Age; Ordinal (O) BIM-RBS, Level of BIM experience; String (S) BIM-RBS-MS.

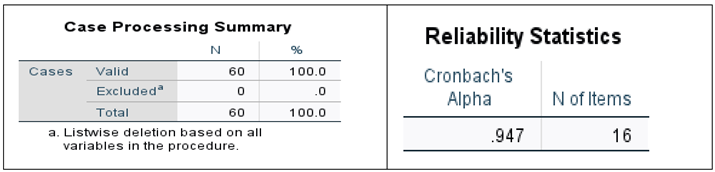

Cronbach’s Alpha (α) test (CA): Used to measure internal consistency/reliability of the survey scale. It assessed the reliability of multiple Likert-scale questions determining the magnitude of risk factors (BIM-RBS). Various thresholds were applied, and the results are shown in the tables below. The 16-item questionnaire measured Evaluation Ability across all BIM-RBS dimensions, yielding a Cronbach’s Alpha value of α = .947, indicating “Very High Reliability” (Cohen et al., 2018, p. 744)

Table 2.

The Cronbach’s Alpha test results.

Table 2.

The Cronbach’s Alpha test results.

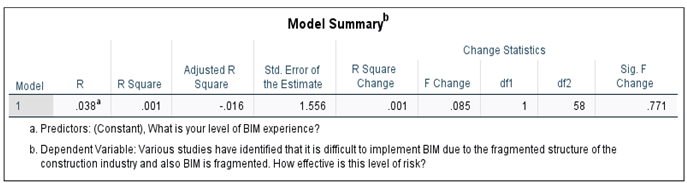

Simple linear regression (SLR): attempts to predict the outcome variable (BIM-RBS) using the predictor variable (Level of BIM experience). The analysis presents the model summary and the table below shows a selection of descriptive statistics about the model/regression overall: the R-value (R), the R-Squared Statistic (R Square), the F statistic measuring change (F Change) and the p-value associated with the F stat change (Sig. F Change)

Table 3.

The Model Summary results.

Table 3.

The Model Summary results.

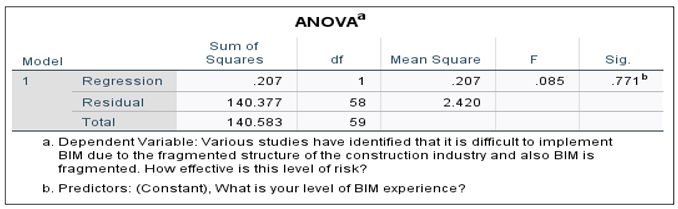

ANOVA: The table below shows a further selection of descriptive statistics about the model/regression overall: two different Degrees of Freedom (df), the F statistic measuring change (F Change) and the p-value associated with the F stat change (Sig. F Change).

Table 4.

The Anova results.

Table 4.

The Anova results.

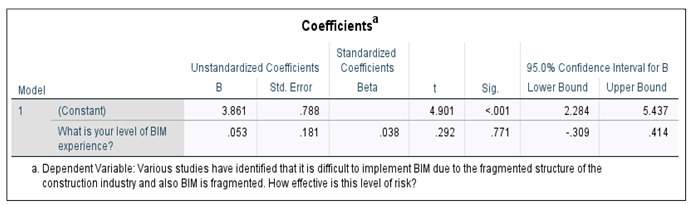

Coefficients: The table below shows the exact values of the constant and of our predictors, it also shows if the variables are significant (Sig.) and the 95% Confidence intervals (95.0% Confidence Interval for B).

Table 5.

The Coefficients results.

Table 5.

The Coefficients results.

A simple linear regression was used to predict the magnitude of the risk factors in BIM-RBS Techno-organisational Aspect (TOA) based on the level of BIM experience. The results showed that experience is a significantly influence on the TOA, however it only accounted for less than 1% of the variance seen in TOA. F= 0.085, p= < .001, R square = 0.001, R square adjusted = -0.016. The regression coefficient (B = -0.053, 95% CI [-0.309,0.414]) indicated that an increase in one point level of BIM experience score, would correspond, on average, to a decrease in BIM-RBS (TOA) score by -0.053 points.

2.4. Mix-method Analysis (Step 5)

This approach involved manually sifting through and analysing both qualitative data (i.e., literature review) and quantitative data (i.e., online survey), enabling different perspectives and paradigms to frame the Nexus BIM-RBS and BIM-RBS-MS matrix and develop the database. This approach helps gain a holistic understanding of risk factors, their magnitude, and management strategies for implementing BIM by comparing data and producing more robust and compelling results with global relevance.

The research gap identified in this study is predominantly associated with two interrelated domains, as revealed through a critical analysis of the literature review. Scholars have mainly focused on a single-dimensional aspect. The technical aspect relates to the physical characteristics of the technology, such as tools (i.e., software and hardware), while the organisational aspect concerns the structure (i.e., inter- or intra-organisational links between departments and disciplines). Therefore, the aspects and capabilities of BIM are examined by narrowing the research scope to the intersection of these two knowledge domains, referred to as the techno-organisational spectrum, as presented below.

Secondary data analysis (Literature review)

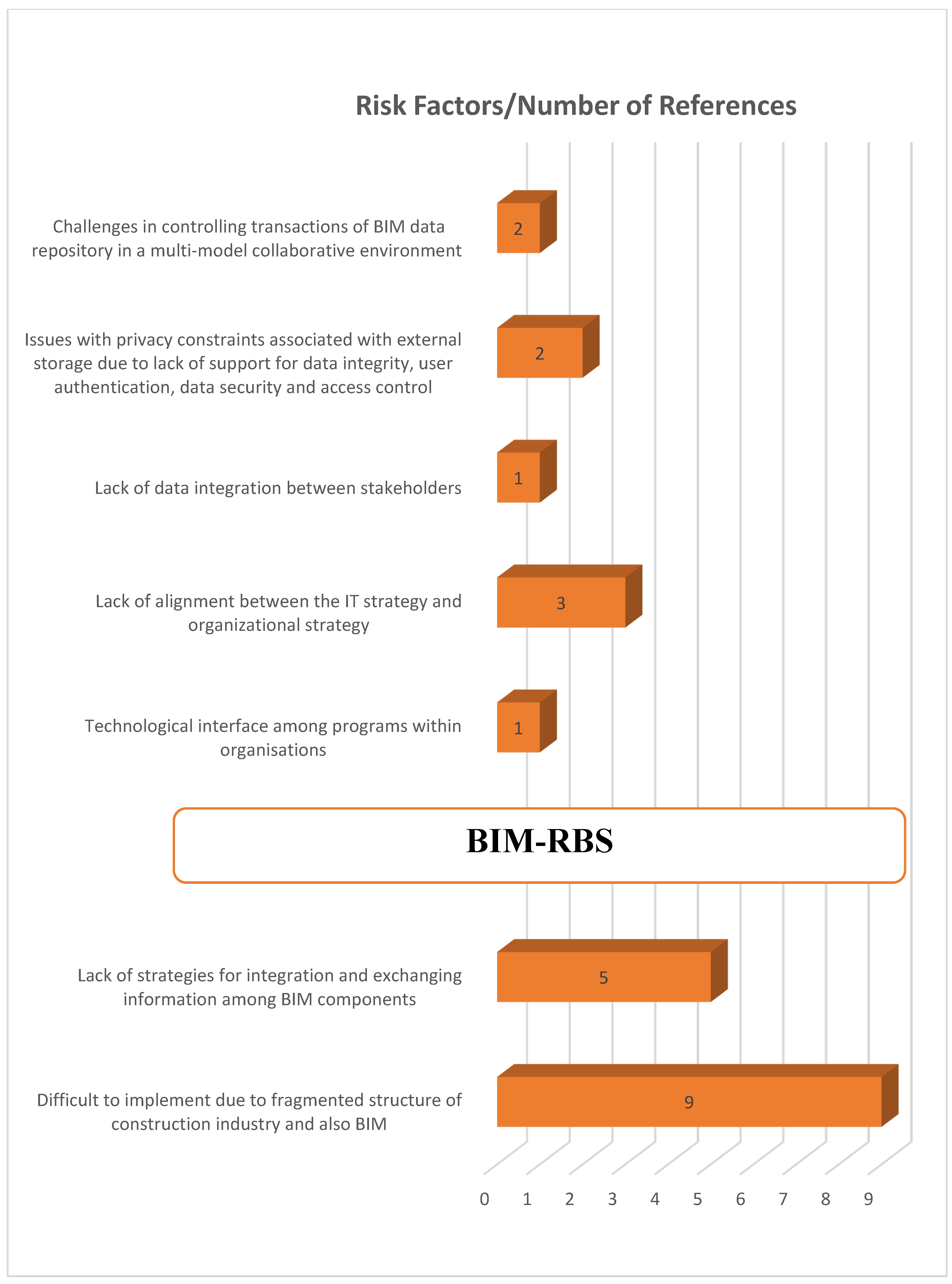

BIM-RBS: Analysing for BIM-RBS, Dossick and Neff (2010) suggest that BIM holds promise for addressing AEC industry challenges, but the analysis reveals practical difficulties in BIM implementation due to the construction industry’s fragmented structure, inherently affecting BIM (Zhao et al. 2018). Notably, there’s a lack of strategies to integrate and exchange information among fragmented BIM components and roles (Matthews et al. 2018), highlighting the need for research to evaluate and address this risk. Practitioners must recognise that immediate solutions for these challenges are elusive, given the constant evolution of BIM technology with new components, processes, and methods (Tomek and Matejka, 2014; Hooper and Ekholm, 2012). Furthermore, the technical challenges of integrating BIM models with other systems such as facilities management, project management and quantity surveying systems etc. indicate time constraint for organisations to properly internalise BIM tools into their work processes and practices. Nevertheless, the boundaries of the two-knowledge domain lack comprehensive research, leading to a shortage of reference materials for certain strategies. Further research was crucial to comprehend and tackle challenges within this category to avoid a shift of BIM systems into a disequilibrium state.

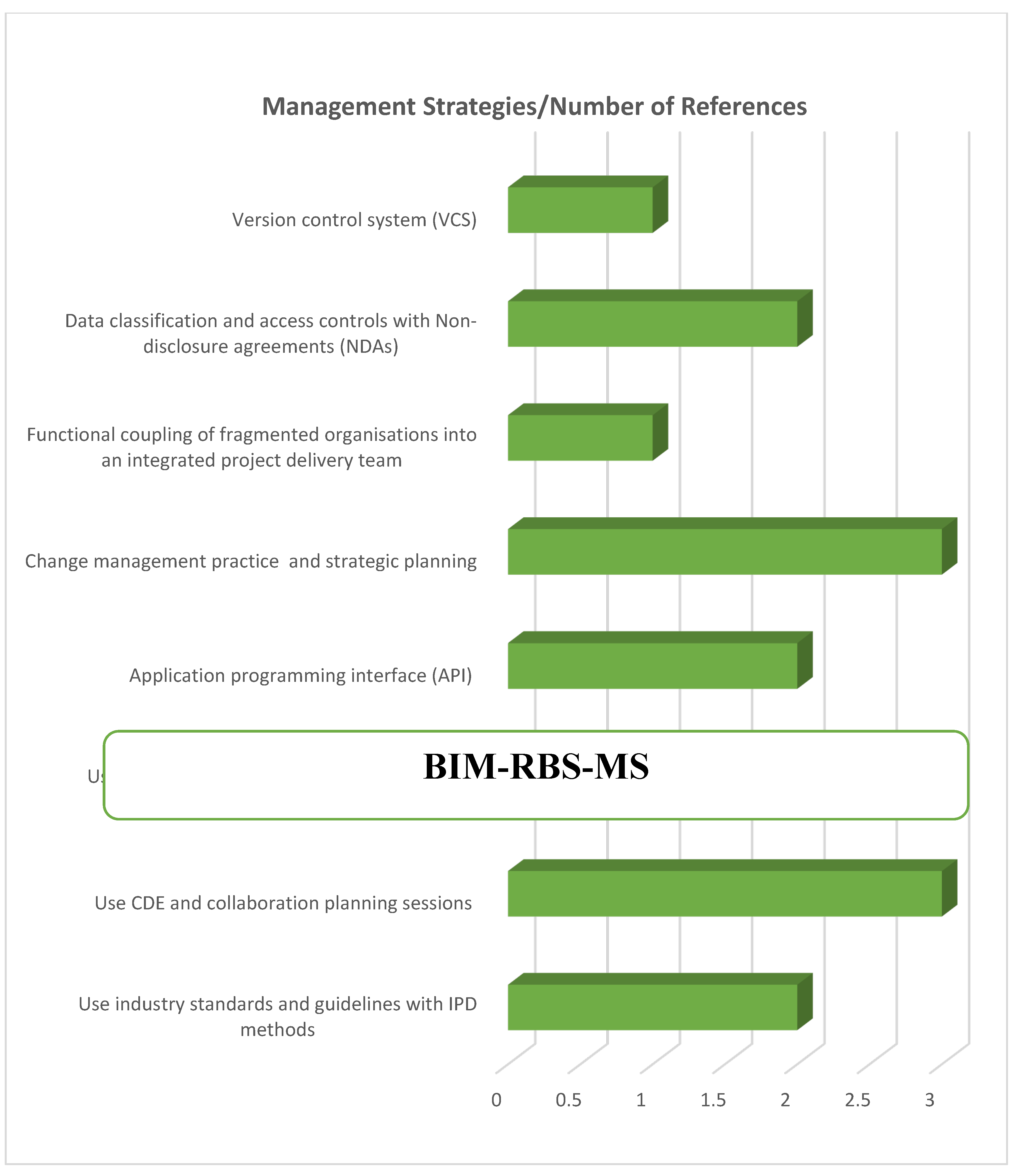

BIM-RBS-MS: Analysing for BIM-RBS-MS to manage data integration gaps among stakeholders, integrating fragmented organisations into an integrated project delivery team can be effective (Mahamadu et al. 2019). Implementing a version control system controls BIM data repository transactions in a collaborative environment, addressing organisational and legal-contractual challenges (Feist et al. 2017). Utilising Application Programming Interface (API) mitigates technological interface challenges, advancing BIM systems toward equilibrium (Chien et al. 2014). (See Figure 8 displaying the findings) Further research was necessary to determine the risk magnitude and establish equilibrium-seeking strategies by employing the online survey to address the risk factors in

Table 1.

Primary data Analysis (Online survey)

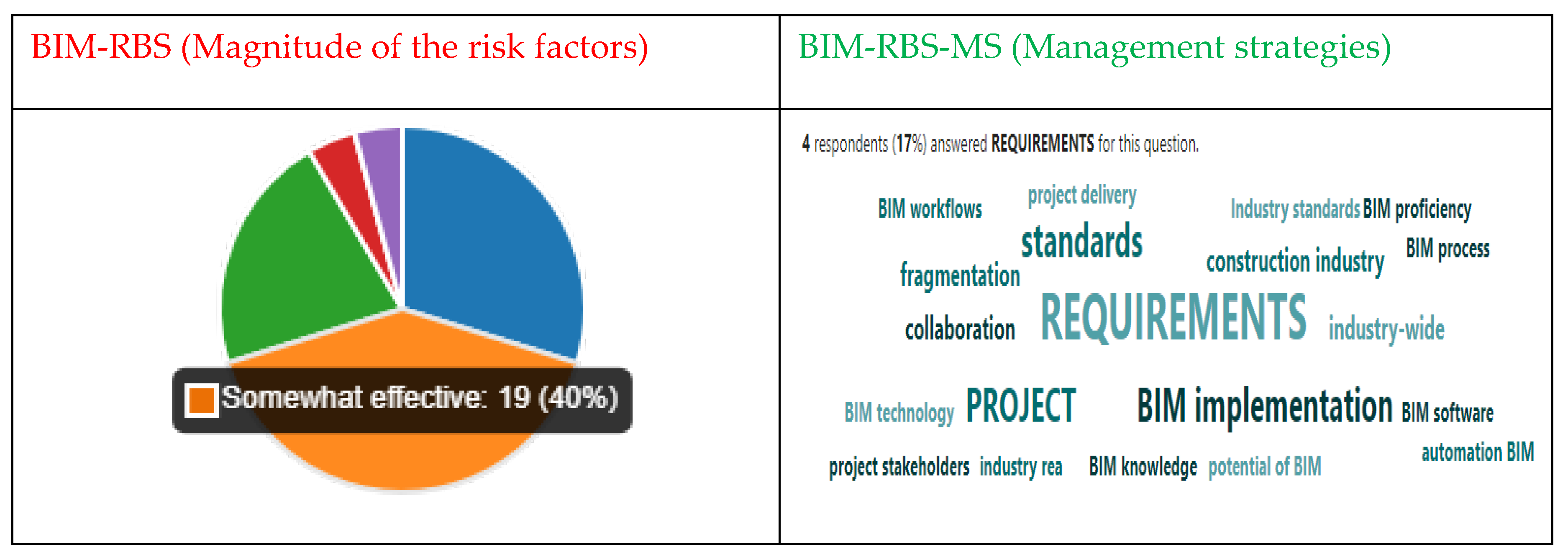

A- (Risk Magnitude): Analysing for risk magnitude to address issues with the difficulty to implement BIM due to the fragmented structure of the construction industry, as BIM is also fragmented still poses challenges. Because it is routed beyond and reaching over to the real estate development dynamics. The level of the risk factor by participants shows 30% selected very effective; 40% somewhat effective; 21% neither effective nor ineffective; 4% somewhat ineffective; 4% very ineffective. A shift to disequilibrium state of BbCNs by 70%. (See

Figure 4)

A-(BIM-RBS-MS) Strategies for Achieving Equilibrium in BIM Implementation: Achieving equilibrium in BIM implementation requires industry standards, collaboration, capacity building, and technological advancements. Organisations and industry bodies have established standards and guidelines to promote consistency and interoperability in BIM processes, aligning data formats and information exchange among stakeholders. Collaborative project delivery methods, such as Integrated Project Delivery (IPD) and Building-SMART’s Open-BIM, encourage early stakeholder involvement, fostering integration and cooperation while reducing fragmentation and improving project outcomes. Capacity-building initiatives, including training programs, certifications, and education, aim to bridge the BIM proficiency gap and promote standardized practices across the industry. Additionally, advancements in BIM software and technology are addressing interoperability challenges, with Open-BIM principles supporting non-proprietary data formats to enhance data exchange and collaboration across platforms. While these strategies help move BIM systems toward equilibrium by enhancing productivity and streamlining processes, challenges remain due to the fragmented nature of the construction industry. Since BIM implementation also faces fragmentation, ongoing collaboration, industry-wide cooperation, and a commitment to standardization are essential to mitigating risks and ensuring long-term success.

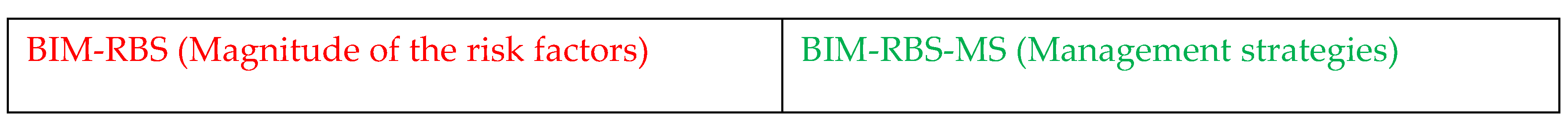

B- (Risk Magnitude): Analysing for risk magnitude due to lack of strategies for integration and exchanging information among BIM components between organisations working together on a project, is also associated with lack of computing power. The level of the risk factor by participants indicates 39% selected very effective; 24% somewhat effective; 16% neither effective nor ineffective; 6% somewhat ineffective; 14% very ineffective. A shift on BIM systems to disequilibrium status by 63%. (See

Figure 5)

B-(BIM-RBS-MS) Strategies for Achieving Equilibrium status in BbCNs: Analysing for BIM-RBS-MS for equilibrium status to achieve a coordinated and integrated approach, enabling smooth collaboration and avoiding delays or discrepancies in the exchange of critical project information involves; conducting collaboration planning sessions early in the project to identify the BIM components involved and establish strategies for their integration. This includes defining information exchange requirements, data formats, and protocols to ensure compatibility and seamless communication between organisations. Utilize data sharing platforms such as Common Data Environments (CDEs) or cloud-based collaboration tools, to facilitate efficient information exchange. These platforms provide a centralised repository for storing and sharing BIM components, enabling real-time access and collaboration among organisations. Establish standardised information exchange protocols that outline the requirements for sharing BIM components. These protocols specify the format, level of detail, and naming conventions to ensure consistency and compatibility across organisations. Utilise BIM software and file formats that supports interoperability, allowing seamless integration of BIM components between organisations. Open-BIM principles and Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) can be utilised to enable the exchange of information across different software platforms. Regular coordination meetings with representatives from each organisation involved in the project. These meetings will provide opportunities to discuss integration challenges, exchange information, and address any issues or conflicts that may arise during the process.

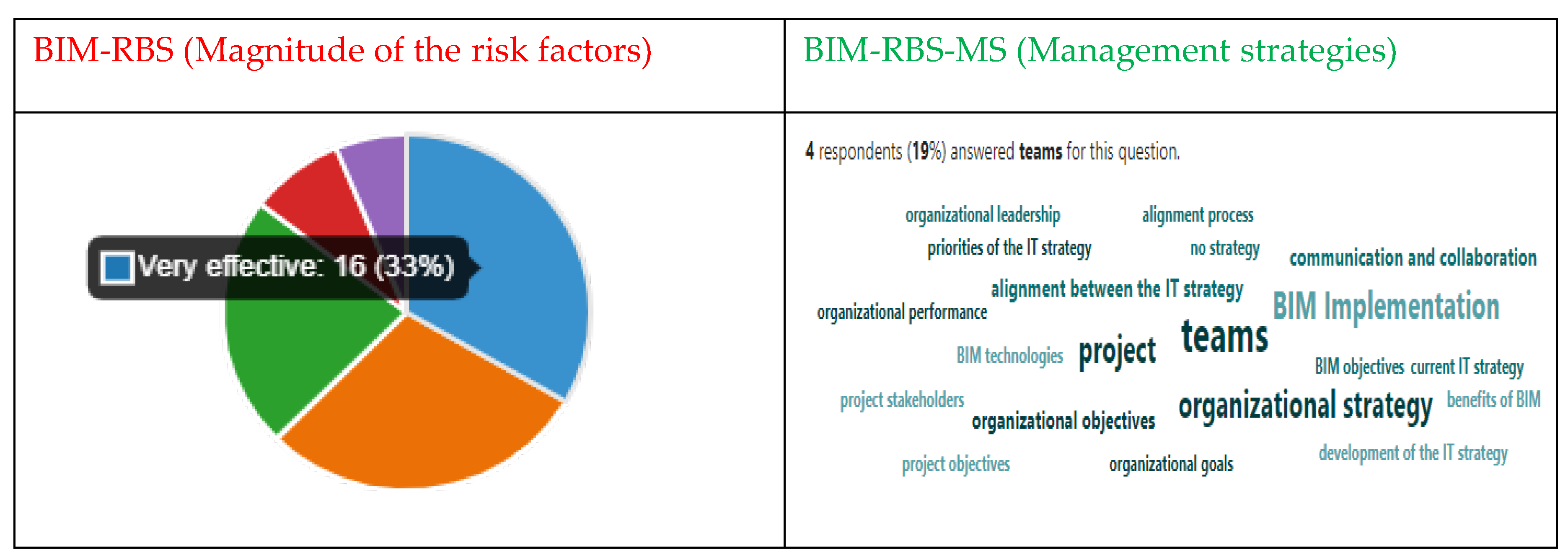

C- (Risk Magnitude): Analysing for risk magnitude due to lack of alignment between the IT strategy and organisational strategy in BIM-enabled projects can result in suboptimal utilization of BIM technologies, disjointed workflows, and missed opportunities for process improvements. In assessing the severity of the risk factor 33% of participant selected very effective; 29% somewhat effective; 23% neither effective nor ineffective; 8% somewhat ineffective; 6% very ineffective. Indicating a shift to disequilibrium status of BbCNs by 62%. (See

Figure 6)

C- (BIM-RBS-MS) Strategies for Attaining Equilibrium Status Implementing BIM: To achieve equilibrium status involves strategic planning where organisations should ensure that the IT strategy and organisational strategy are developed in tandem. This involves aligning the objectives, goals, and priorities of the IT strategy with the overall organisational strategy. Clear communication and collaboration between IT and organisational leadership are essential to achieving this alignment. Engaging key stakeholders from different departments and levels of the organisation is crucial to understand their requirements and expectations regarding BIM implementation. This input should be considered in the development of the IT strategy, ensuring that it supports and enables the broader organisational objectives. Encouraging cross-functional collaboration and communication between IT teams and other departments is essential for aligning strategies. Regular meetings, workshops, and forums can facilitate knowledge sharing and ensure that the IT strategy is closely linked to the needs of various business units. Effective change management practices should be implemented to support the alignment process. This involves communicating the strategic direction, addressing any resistance or concerns, and providing training and support to ensure smooth adoption of BIM technologies and practices across the organisation. Continuous evaluation and adjustment by regular monitoring and evaluation of the alignment between the IT strategy and organisational strategy should be conducted. This allows organisations to identify any gaps or emerging issues and make necessary adjustments to ensure ongoing alignment. Organisations that prioritize alignment and actively work towards bridging the gap are more likely to achieve better integration of BIM technologies, improved organisational performance, and enhanced project outcomes.

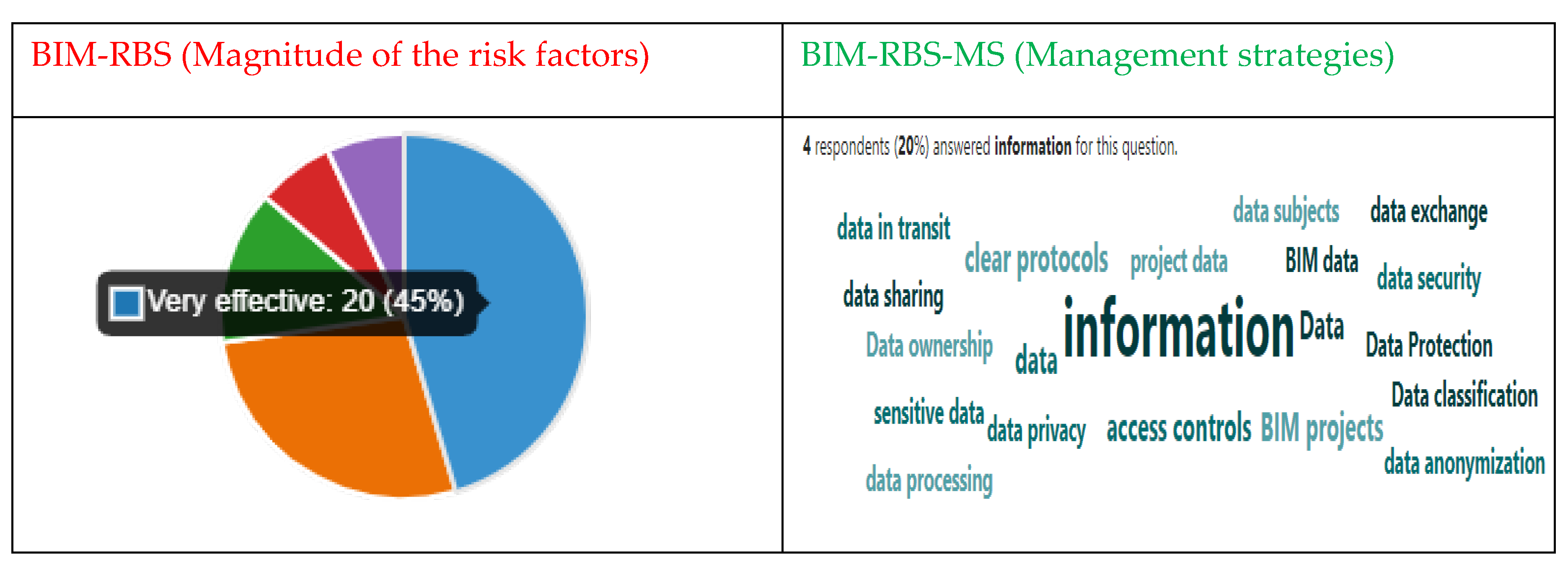

D- (Risk Magnitude): Analysing the magnitude of the risk factor regarding issues with privacy constraints associated with external storage when organisations work together due to data security and access control; user authentication and data integrity; challenges controlling transactions in multi-model collaborative environment on a BIM project. The assessment indicates 45% of participant selected very effective; 27% somewhat effective; 14% neither effective nor ineffective; 7% somewhat ineffective; 7% very ineffective. A shift on BIM systems to disequilibrium state by 72%. (See

Figure 7)

D- (BIM-RBS-MS) Strategies to Achieve Equilibrium Status in BIM implementation: To effectively manage the risk severity and shift BIM systems towards equilibrium status involves data classification and access control. As organisations should implement a data classification framework that categorises information based on its sensitivity and importance. Access control should be established to restrict access to sensitive data, ensuring that only authorised individuals can view and modify it. When sharing BIM data externally, secure data transfer protocols should be employed to protect data in transit. Encryption, secure file transfer protocols, and virtual private networks (VPNs) can be used to establish secure channels for data exchange. Organisations should implement non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) with external parties involved in the project. These agreements establish legal obligations for maintaining the confidentiality of shared information and help protect against unauthorised disclosure. Clear policies should be established regarding data ownership and retention. This ensures that organisations retain control over their data and can specify how long it will be stored and when it should be securely disposed of after the project’s completion. Organisations should adhere to relevant privacy regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) or local data protection laws. Ensuring compliance with these regulations includes obtaining necessary consent for data processing, providing transparency to data subjects about the collection and use of their data, and implementing appropriate safeguards for data protection. These measures align towards best practices for data privacy and security, ensuring that sensitive information is adequately protected throughout the project lifecycle.

3.1. Findings

The findings from the analysis shows the aspects and capabilities of BIM-RBS and BIM-RBS-MS providing an up to date understanding of risk factors and management strategy in the techno-organisational spectrum “BIM-RBS Matrix and BIM-RBS-MS Nexus”. (See

Figure 8 and

Table 6)

The average magnitude of the risk factors in this spectrum is 66.75% shift to disequilibrium status. The risk magnitude associated with the difficulty to implement BIM due to the fragmented structure of the construction industry and BIM is also fragmented is 70% shift to disequilibrium state and can be managed using industry standards and guidelines with IPD methods. Lack of strategies for integration and exchanging information among BIM components has a 63% shift and can be minimised using CDE and collaboration planning sessions. Lack of alignment between the IT strategy and organisational strategy has a 62% shift and can be mitigated implementing change management practice and strategic planning. Privacy constraints associated with external storage has a 72% shift to disequilibrium state and can be minimised using data classification and access control with non-disclosure agreements.

3.2. Discussions

The body of literature examining BIM and risk management, as assessed by various scholars (Zou et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2018; Ganbat et al., 2019; Georgiadou, 2019; Blay et al., 2019; Pu et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2022; Waqar et al., 2023; Okika et al. 2024; Elnokaly and Dogonyaro, 2024; Ahmad et al., 2025) has significantly advanced our understanding in key BIM-related domains. This includes diverse insights into BIM definitions presented by experts such as Mahamadu et al. (2014), Lee et al. (2014), Zou et al. (2016), Kadume and Naji (2021), Khoshfetrat et al. (2022), Yasser et al. (2023), and Ahmad et al. (2025). It also explores the integration of BIM with other components, processes, and methodologies, advancing the technology into the Construction 5.0 era (Lee et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2017; Sani and Rahman, 2018; Waqar et al., 2023; Tabejamaat et al., 2024; Yitmen et al., 2024). The critical analysis of these findings highlights key areas within BIM studies, unveiling previously unexplored facets and identifying notable research gaps such as the techno-organisational spectrum. The varying definitions of BIM, reflecting its multifaceted applications across disciplines, contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the term and also exacerbate further risks. Furthermore, the examination reveals that the integration of BIM maturity advances with various components, methods, and processes, as discussed in the existing literature, heightens the risk factors associated with BIM implementation. Responding to these challenges, scholars (Ahmad et al., 2025; Yasser et al., 2023; Pu et al., 2021; Ali et al., 2022; Ganbat et al., 2019; Georgiadou, 2019; Blay et al., 2019; Bensalah et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2018) have independently proposed some strategies and delineated singular dimensions of risk factors, culminating in the emergence of the concept of BIM-RBS, a term embraced and expanded upon in this study. The scope of the risk management process employed by these scholars in their studies was limited to the third stage of the risk management process. However, this study extends the process one step further to the fourth stage, risk response and treatment culminating in the identification of management strategies to develop BIM-RBS-MS in alignment with BIM-RBS as strategies to mitigate the risk factors that extends to the amalgamated dimensional aspects specifically the techno-organisational spectrum.

To achieve this, an integrative approach was employed, facilitating the processing of retrieved papers on BIM and risk management. Furthermore, the purpose of the analysis, conducted through coding using NVivo 12 Pro software, not only established BIM-RBS through thematic analysis from a single dimensional perspective but also unveiled BIM-RBS-MS through content analysis from both single and double dimensional perspective of the techno-organisational spectrum. This extends to the analysis conducted through statistics using SPSS software to further discover management strategies for the identified risk factors and determine its magnitude, and further validate the established theoretical framework by Elnokaly and Dogonyaro (2024). These methods include the Cronbach’s Alpha (α) test for reliability and ‘Simple’ Linear Regression to predict the outcome variable (BIM-RBS) using the predictor variable (Level of BIM experience). This allowed for the interpretation of the techno-organisational aspect of risk factors and management strategies, generating the terminology that had not been previously explored in scholarly works. Thus, contributes to a deeper understanding of BIM-related risk severity and provides valuable insights into the development of effective management strategies. This approach completely neutralises the issue put forward by Zhao et al. (2018) that the construction industry is fragmented, likewise introducing innovative technology such as BIM is also fragmented. As Matthews et al. (2018) suggest the successful implementation of BIM involves moving away from fragmented roles, and the findings in this study is a course of action. Because it is a solution which will aid in mitigating these risks that will keep evolving based on Hooper and Ekholm (2012) suggestion that BIM project delivery remains both a practical and a theoretical problem due to new design processes and procedures emerging. In essence, this study not only enriches the existing knowledge base but also equips AEC professionals with a data that transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries, fostering a more integrated and informed approach to BIM implementation. Moreover, the qualitative methodology, leveraging NVivo 12 Pro software for coding, demonstrated its efficacy. The quantitative methodology via the statistical approach determined the severity of the risk factors. Both approaches (i.e., mixed method) facilitated the establishment of “BIM-RBS Matrix and BIM-RBS-MS Nexus.” Notably, this database systematically categorises risks inherent across disparate construction stages and proffers targeted management strategies aimed at mitigating their impact.

Despite the invaluable insights offered by this study, it is imperative to acknowledge certain inherent limitations. Notably, the absence of data validation through case study approach via interviews and observations involving real-world cases stands out as a constraint. This limitation implies that the robustness of the findings may be subject to the absence of direct engagement with practitioners and stakeholders in real construction scenarios. The reliance on academic publications and the online survey conducted while informative, introduces another potential limitation, as it may not fully capture the complex and dynamic challenges present in actual construction projects. The impact on the validity of the appropriate strategies is an aspect that warrants consideration. To address these limitations future research endeavours should prioritize validation through case studies via implementation in real-world construction projects. This pragmatic approach not only ensures a more comprehensive understanding but also serves to bridge existing gaps between theoretical propositions and practical applications in the dynamic field of BIM and risk management.

The practical implications of this study are profound. The developed “BIM-RBS Matrix and BIM-RBS-MS Nexus” provides a valuable repository of strategies to assist industry professionals in effectively mitigating associated risks. This repository can serve as a knowledge base and a “check and balance mechanism,” guiding AEC professionals towards a more efficient BIM implementation process from a techno-organisational perspective. Furthermore, as BIM integration continues to evolve, organisations must embrace the flexibility of the BIM-RBS and BIM-RBS-MS Nexus to continually update new strategies, post-implementation ensuring long-term performance monitoring. The potential for generalisation and application of the BIM-RBS and BIM-RBS-MS nexus is substantial because its adaptability emphasises its value for various disciplines involved in BIM-enabled projects—architects during design, contractors throughout construction, and facilities managers during maintenance. For project managers overseeing all stages providing indispensable guidance. Academically, this study expands the research domain by delving into two key knowledge domains such as the techno-organisational aspect which can influence government regulations and guidelines concerning BIM and risk management, shaping their development and implementation. The novel BIM-RBS Matrix and BIM-RBS-MS Nexus composes an exceptional knowledge contribution to the field addressing an important gap, providing new insight, and demonstrating its potential for global impact and applicability via the breakthrough techno-organisational aspect.

4. Conclusion

This study of BIM and risk management presented in this paper provided an up to date understanding of challenges and risks involved in BIM-enabled projects due to limited research. Numerous studies were conducted on the single dimensional aspects such as technical, social and organisational aspect etc. however, this research have shown that there is an evident knowledge gap on the two-dimensional aspect such as the techno-organisational spectrum. The integrative review of previous studies undertaken established challenges, barriers and highlight the risk factors implementing the technology. BIM maturity levels leading to the fourth and fifth industrial revolutions represent the era of digitisation (i.e., industry 4.0; 5.0). It is upon the AEC industry to transform through these processes (i.e., Construction 5.0 enhancing collaboration between humans and machines) to advance the industry. Making the construction industry more sustainable and improving the working experience. Hence, BIM, Digital twin and AI technologies are at the centre to become the key factors. For the transformation of the construction industry to move towards this era it is essential to resolve the risk factors (BIM-RBS) identified in this study related to the techno-organisational spectrum. The integrative approach undertaken enabled the discovery of appropriate management strategies used such as Application Programming Interface (API) to eradicate issues with technological interface among various programs. The critical analysis of the results via the mixed method approach guided by the theoretical framework enabled the establishment of a novel robust BIM-RBS Matrix establishing the risk magnitude and BIM-RBS-MS Nexus to mitigate the risks as a contribution to knowledge that can be used globally by AEC and academic professionals.

4.1. Recommendations

This study highlights a significant gap in existing research, particularly at the intersection of two knowledge domains—BIM-RBS and BIM-RBS-MS. Further exploration in this area is essential, prompting the need to address these issues from a:

Socio-organisational Aspect

Eco-financial perspective

Legal-contractual perspective

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available on demand, within the article and its supplementary materials.

Acknowledgements

This article and the research behind were possible due to the exceptional support of my supervisors. Their enthusiasm, knowledge and exacting attention to detail have been an inspiration and also looked over my transcripts. I am grateful for the perceptive comments they offered. Their expertise has improved this study in innumerable ways.

Ethics Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the University of Lincoln Ethics Committee. The research project titled “A Framework for Identifying the Link between BIM-RBS Management Strategies and BIM-RBS Risk Factors” (Review ref. 2021_7067) received a favourable ethical opinion on 17 September 2021.

References

- Ahmad, D. M., Gáspár, L., & Maya, R. A. (2025). Optimizing Sustainability in Bridge Projects: A Framework Integrating Risk Analysis and BIM with LCSA According to ISO Standards. “Applied Sciences, 15(1), 383. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, D.M., Gáspár, L., Bencze, Z. and Maya, R.A., (2024) The Role of BIM in Managing Risks in Sustainability of Bridge Projects: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. “Sustainability, 16(3), p.1242. [CrossRef]

- Ali, K.N., Alhajlah, H.H. and Kassem, M.A., (2022) Collaboration and risk in building information modelling (BIM): a systematic literature review. “Buildings, 12(5), p.571.

- Akhtar, D.M.I., (2016) Research design. Research in Social Science: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. pp.68-84. Available online at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Research+Design+Md.+Inaam+Akhtar+Deptt.+of+Political+Science%2C+Faculty+of+Social+Sciences%2C+Jamia+Millia+Islamia%2C+New+Delhi&btnG= Retrieved on 28/08/22.

- Aksenova, G., Kiviniemi, A., Kocaturk, T. and Lejeune, A., (2019) From Finnish AEC knowledge ecosystem to business ecosystem: lessons learned from the national deployment of BIM. “Construction management and economics, 37 (6) 317-335. [CrossRef]

- Alreshidi, E., Mourshed, M. and Rezgui, Y., (2018) Requirements for cloud-based BIM governance solutions to facilitate team collaboration in construction projects. “Requirements engineering, 23 (1) 1-31. [CrossRef]

- Azhar, S. (2011) Building Information Modelling (BIM): Trends, Benefits, Risks, and Challenges for the AEC Industry. “Leadership Management in Engineering, 11(3) 241-252.

- Beach, T., Petri, I., Rezgui, Y. and Rana, O. (2017) Management of Collaborative BIM Data by Federating Distributed BIM Models. 31(4) 4017009. Available from http://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/(ASCE)CP.1943-5487.0000657.

- Bensalah, M., Elouadi, A. and Mharzi, H. (2019) Overview: the opportunity of BIM in railway. 8(2) 103–116. Available from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/SASBE-11-2017-0060/full/html.

- Blay, K.B., Tuuli, M.M. and France-Mensah, J. (2019) Managing change in BIM-Level 2 projects: benefits, challenges, and opportunities. 9(5) 581–596. Available from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/BEPAM-09-2018-0114/full/html.

- Chenya, L., Aminudin, E., Mohd, S. and Yap, L.S., (2022) Intelligent risk management in construction projects: Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access. [CrossRef]

- Chien, K.-F., Wu, Z.-H. and Huang, S.-C. (2014) Identifying and assessing critical risk factors for BIM projects: Empirical study. 45 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K., (2018) Research methods in education. Routledge.

- Creswell, W. J. (2003) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches. 2nd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA; Sage.

- DeLone W. H. and McLean E. R. (2003) The DeLone and McLean Model of Information Systems Success: A Ten-Year Update “Journal of Management Information Systems, 19 (4) 9–30.

- Dhakal, K., (2022) NVivo. “Journal of the Medical Library Association, 110(2) 270-272.

- Ding, L., Zhong, B., Wu, S. and Luo, H. (2016) Construction risk knowledge management in BIM using ontology and semantic web technology. 87 202–213. Available from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0925753516300492.

- Dossick, C.S. and Neff, G. (2010) Organizational Divisions in BIM-Enabled Commercial Construction. 136(4) 459–467. Available from http://ascelibrary.org/doi/abs/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0000109.

- Duran, Ö. and Elnokly, A., (2024) Collaborative Approach to Design: Case-study of Future-Proofing A Paragraph 80 House. Proceedings of the 18th IBPSA Conference, Shanghai, China, Sept. 4-6, 2023. P 1497-1504.

- Elnokaly, A. and Dogonyaro, I., (2024) Framework to assess connection of risk factors and management strategies in Building Information Modelling. “Academia Engineering, 1(4) 1-20. [CrossRef]

- Elshabshiri, A., Ghanim, A., Hussien, A., Maksoud, A., & Mushtaha, E. (2025). Integration of Building Information Modelling and Digital Twins in the Operation and Maintenance of a Building Lifecycle: A Bibliometric Analysis Review. “Journal of Building Engineering, 111541. [CrossRef]

- Enegbuma, W.I., Aliagha, U.G. and Ali, K.N. (2014) Preliminary building information modelling adoption model in Malaysia. 14(4) 408–432. Available from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2083743522.

- Feist, S., Ferreira, B., and Leitão, A. (2017) Collaborative algorithmic-based building information modelling. Protocols, Flows and Glitches, Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference of the Association for Computer-Aided Architectural Design Research in Asia (CAADRIA) 2017, 613-623.

- Ganbat, T., Chong, H.-Y., Liao, P.-C. and Lee, C.-Y. (2019) A Cross-Systematic Review of Addressing Risks in Building Information Modelling-Enabled International Construction Projects. 26(4) 899–931. Available from https://search.proquest.com/docview/2041056169.

- Ganbat, T., Chong, H., Liao, P. and Wu, Y. (2018) A Bibliometric Review on Risk Management and Building Information Modelling for International Construction. “Advances in Civil Engineering, (1) 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Georgiadou, M. (2019) An overview of benefits and challenges of building information modelling (BIM) adoption in UK residential projects. “Construction Innovation, 19 (3) 298-320. [CrossRef]

- Górecki, J. (2018) Big Data as a Project Risk Management Tool. “Risk Management Treatise for Engineering Practitioners, (2) 26-49.

- Grant, C. and Osanloo, A. (2014) Understanding, selecting, and integrating a theoretical framework in dissertation research: Creating the blueprint for your “House” “Administrative issues journal, 4 (2) 12-26.

- Hartmann, T., van Meerveld, H., Vossebeld, N. and Adriaanse, A. (2012) Aligning building information model tools and construction management methods. 22 605–613. Available from https://search.datacite.org/works/10.1016/j.autcon.2011.12.011.

- He, Z., Wang, Y. H., & Zhang, J. (2025). Generative AIBIM: An automatic and intelligent structural design pipeline integrating BIM and generative AI. “Information Fusion, (114) 102654. [CrossRef]

- Hooper, M and Ekholm, A (2012) A BIM-Info delivery protocol. “Australasian Journal of Construction Economics and Building, 12(4), 39-52.

- Huan, X., Kang, B. G., Xie, J., & Hancock, C. (2025). Building Information Modelling (BIM)-enabled Facility Management (FM) of Nursing Homes in China: A Systematic Review. “Journal of Building Engineering, 111580. [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N. H., Kamal, E. M., & Fizal, M. F. (2025) A Systematic Literature Review: Implementing Building Information Modelling (BIM) for TVET Educators in Malaysia. “Journal of Advanced Research in Applied Sciences and Engineering Technology 49 (1) 194-210. [CrossRef]

- Kadume, N. H., and Naji, H. I. (2021) Building Schedule Risks Simulation by Using BIM with Monte Carlo Technique. “IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 856 (2021) 012059. [CrossRef]

- Khoshfetrat, R., Sarvari, H., Chan, D.W. and Rakhshanifar, M., (2022) Critical risk factors for implementing building information modelling (BIM): a Delphi-based survey. “International Journal of Construction Management, 22 (12) 2375-2384. [CrossRef]

- Khosrowshahi, F. and Arayici, Y. (2012) Roadmap for implementation of BIM in the UK construction industry. 19(6) 610–635. Available from http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/10.1108/09699981211277531.

- Kivunja, C. (2018) Distinguishing between Theory, Theoretical Framework, and Conceptual Framework: A Systematic Review of Lessons from the Field “International Journal of Higher Education, 7 (6) 44-53.

- Klein, G. and Müller, R., (2020) Literature Review Expectations of Project Management Journal®. “Project Management Journal, 51(3) 239-241.

- Kozlovska, M., Klosova, D. and Strukova, Z. (2021) Impact of Industry 4.0 Platform on the Formation of Construction 4.0 Concept: A Literature Review. “Sustainability, (13) 2683. [CrossRef]

- Ku DDES, K. and Taiebat, M. (2011) BIM Experiences and Expectations: The Constructors’ Perspective. 7(3) 175–197. Available from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/15578771.2010.544155.

- Leavitt, H. J. (1964). “Applied organization change in industry: Structural, technical and human approaches.” New perspectives in organizational research, W. W. Cooper, H. J. Leavitt, and M. W. Shelly, eds., John Wiley, New York, 55–71.

- Lee, P.C., Wei, J., Ting, H.I., Lo, T.P., Long, D. and Chang, L.M. (2019) Dynamic Analysis of Construction Safety Risk and Visual Tracking of Key Factors based on Behaviour-based Safety and Building Information Modelling. 23(10) 4155–4167. Available from https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002506377.

- Li, X., Jiang, M., Lin, C., Chen, R., Weng, M., & Jim, C. Y. (2025). Integrated BIM-IoT platform for carbon emission assessment and tracking in prefabricated building materialization. “Resources, Conservation and Recycling, (215) 108122. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Li, M., & Ji, W. (2025). Development and application of a digital twin model for Net zero energy building operation and maintenance utilizing BIM-IoT integration. “Energy and Buildings, (328) 115170. [CrossRef]

- Mahamadu, A.-M., Mahdjoubi, L., Booth, C., Manu, P. and Manu, E. (2019) Building information modelling (BIM) capability and delivery success on construction projects. 19(2) 170–192. Available from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/CI-03-2018-0016/full/html.

- Maskil-Leitan, R., Gurevich, U. and Reychav, I., (2020) BIM management measure for an effective green building project. “Buildings, 10(9), p.147. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, J., Love, P.E.D., Mewburn, J., Stobaus, C. and Ramanayaka, C. (2018) Building information modelling in construction: insights from collaboration and change management perspectives. 29(3) 202–216. Available from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09537287.2017.1407005.

- Mat Ya’acob, I.A., Mohd Rahim, F.A. and Zainon, N. (2018) Risk in Implementing Building Information Modelling (BIM) in Malaysia Construction Industry: A Review. 65 3002. Available from https://www.openaire.eu/search/publication?articleId=doajarticles::ed31ed2f1ae12567b82d0ab66f9afd7b.

- Merschbrock, C., Hosseini, M., Martek, I., Arashpour, M. and Mignone, G. (2018) Collaborative Role of Sociotechnical Components in BIM-Based Construction Networks in Two Hospitals. “American Society of Civil Engineers, 34(4). [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei-Zohan, S.A., Gheibi, M., Chahkandi, B., Mousavi, S., Khaksar, R.Y. and Behzadian, K., 2023. A new integrated agent-based framework for designing building emergency evacuation: A BIM approach. International journal of disaster risk reduction, 93, p.103753. [CrossRef]

- Okika, M.C., Vermeulen, A. and Pretorius, J.H.C., (2024) A Systematic Approach to Identify and Manage Interface Risks between Project Stakeholders in Construction Projects. “Civil Eng, 5(1), pp.89-118. [CrossRef]

- Oraee, M., Hosseini, M.R., Papadonikolaki, E., Palliyaguru, R. and Arashpour, M. (2017) Collaboration in BIM-based construction networks: A bibliometric-qualitative literature review. 35(7) 1288–1301. [CrossRef]

- Oyedele, L.O., Regan, M., von Meding, J., Ahmed, A., Ebohon, O.J. and Elnokaly, A. (2013), “Reducing waste to landfill in the UK: identifying impediments and critical solutions”, World Journal of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, Vol. 10 No. 2, pp. 131-142. [CrossRef]

- Pavón, R. M., Alberti, M. G., Álvarez, A. A. A., & Cepa, J. J. (2025). Bim-based Digital Twin development for university Campus management. Case study ETSICCP. “Expert Systems with Applications, (262) 125696. [CrossRef]

- Poirier, A., Forgues, D. and Staub-French, S. (2017) Understanding the impact of BIM on collaboration: a Canadian case study; “Building Research & Information, 45(6).

- Pu, L. and Wang, Y., (2021) The combination of BIM technology with the whole life cycle of green building. “World Journal of Engineering and Technology, 9(3)604-613. [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, A. A., Ansari, R., Taherkhani, R. and Hosseini, M. R. (2021) Developing a novel cash flow risk analysis framework for construction projects based on 5D BIM. “Journal of Building Engineering, (44). [CrossRef]

- Sackey, E., Tuuli, M. and Dainty, A. (2014) Sociotechnical Systems Approach to BIM Implementation in a Multidisciplinary Construction Context “American Society of Civil Engineers, 31(1) 1-11.

- Sani, M.J. and Abdul Rahman, A. (2018) GIS and BIM integration at data level: a review. 299–306. Available from https://www.openaire.eu/search/publication?articleId=dedup_wf_001::9f2144c87bd11c2a6cd9dd2460190ab3.

- Succar, B., Sher, W. and Williams, A. (2012) Measuring BIM performance: Five metrics. 8(2) 120–142. Available from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17452007.2012.659506.

- Szymański, P., (2017) Risk management in construction projects. “Procedia engineering, (208)174-182.

- Tabejamaat, S., Ahmadi, H. and Barmayehvar, B., 2024. Boosting large-scale construction project risk management: Application of the impact of building information modelling, knowledge management, and sustainable practices for optimal productivity. “Energy Science & Engineering, 12(5), pp.2284-2296.

- Tomek, A. and Matejka, P. (2014) The impact of BIM on risk management as an argument for its implementation in a construction company. “Procedia engineering, (85) 501-509.

- Wang, G. and Song, J., (2017) The relation of perceived benefits and organizational supports to user satisfaction with building information model (BIM). “Computers in Human Behaviour, (68) 493-500. [CrossRef]

- Waqar, A., Qureshi, A.H. and Alaloul, W.S., (2023) Barriers to building information modelling (BIM) deployment in small construction projects: Malaysian construction industry. “Sustainability, 15(3), p.2477. [CrossRef]

- Yanda, G., Amin, M. and Soehari, T. D. (2019) Investment, Returns, and Risk of Building Information Modelling (BIM) Implementation in Indonesia’s Construction Project. “International Journal of Engineering and Advanced Technology, 9 (1) 5159- 5166.

- Yasser, M., Rashid, I.A., Nagy, A.M. and Elbehairy, H.S., (2022) Integrated model for BIM and risk data in construction projects. “Engineering Research Express, 4(4)045044. [CrossRef]

- Yitmen, I., Almusaed, A. and Alizadehsalehi, S., (2024) Facilitating Construction 5.0 for smart, sustainable and resilient buildings: opportunities and challenges for implementation. “Smart and Sustainable Built Environment. Available at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2046-6099.htm.

- Zairul, M. and Zaremohzzabieh, Z. (2023) Thematic Trends in Industry 4.0 Revolution Potential towards Sustainability in the Construction Industry. “Sustainability, (15) 7720. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X., Wu, P. and Wang, X. (2018) Risk paths in BIM adoption: empirical study of China. 25(9) 1170–1187. Available from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ECAM-08-2017-0169/full/html.

- Zhao, X., Feng, Y., Pienaar, J. and O’Brien, D. (2017) Modelling paths of risks associated with BIM implementation in architectural, engineering and construction projects. 60(6) 472–482. Available from https://proxy.library.lincoln.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=vth&AN=125880558&site=ehost-live.

- Zou, Y., Kiviniemi, A., Jones, S., and Walsh, J. (2019) Risk Information Management for Bridges by Integrating Risk Breakdown Structure into 3D/4D BIM. 23(2) 467–480. Available from https://www.openaire.eu/search/publication?articleId=core_ac_uk__::c18d9a37d1b034d6840499170df7da7e.

- Zou, Y., Kiviniemi, A. and Jones, S.W. (2017) A review of risk management through BIM and BIM-related technologies. 97 88–98. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y., Kiviniemi, A. and Jones, S.W. (2016) Developing a tailored RBS linking to BIM for risk management of bridge projects. 23(6) 727–750. Available from https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/ECAM-01-2016-0009/full/html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).