Submitted:

31 October 2025

Posted:

03 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

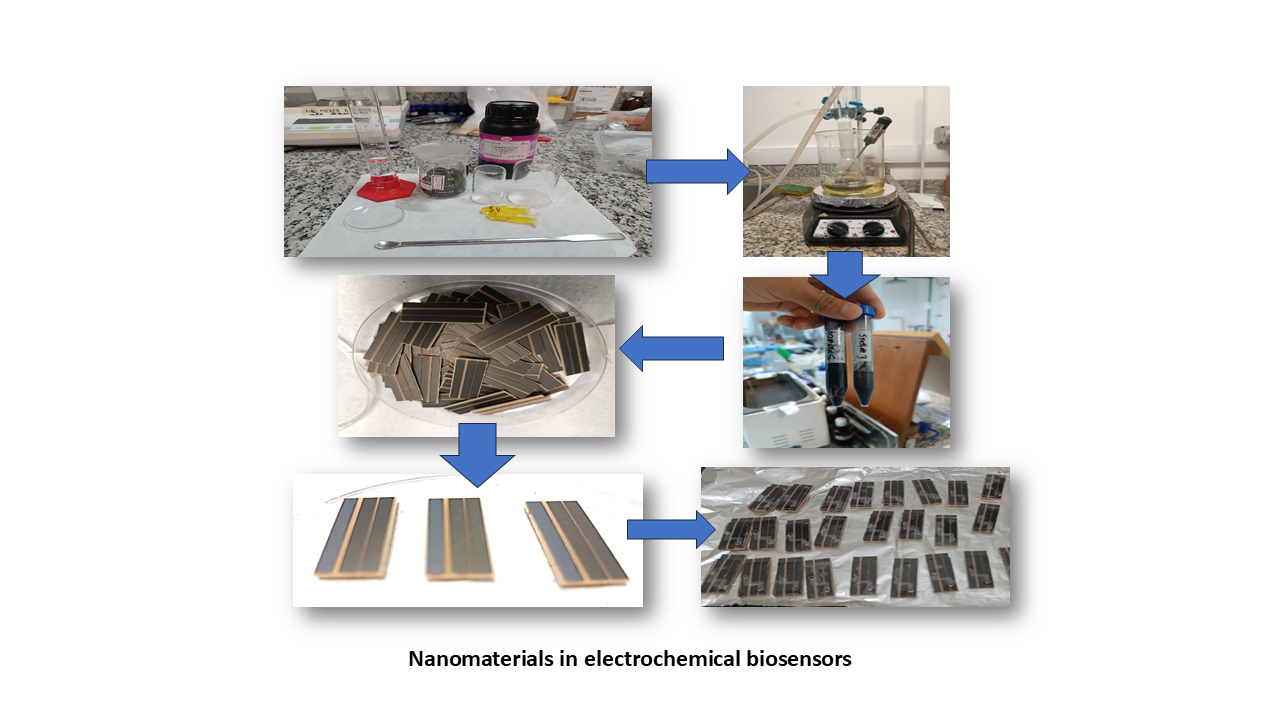

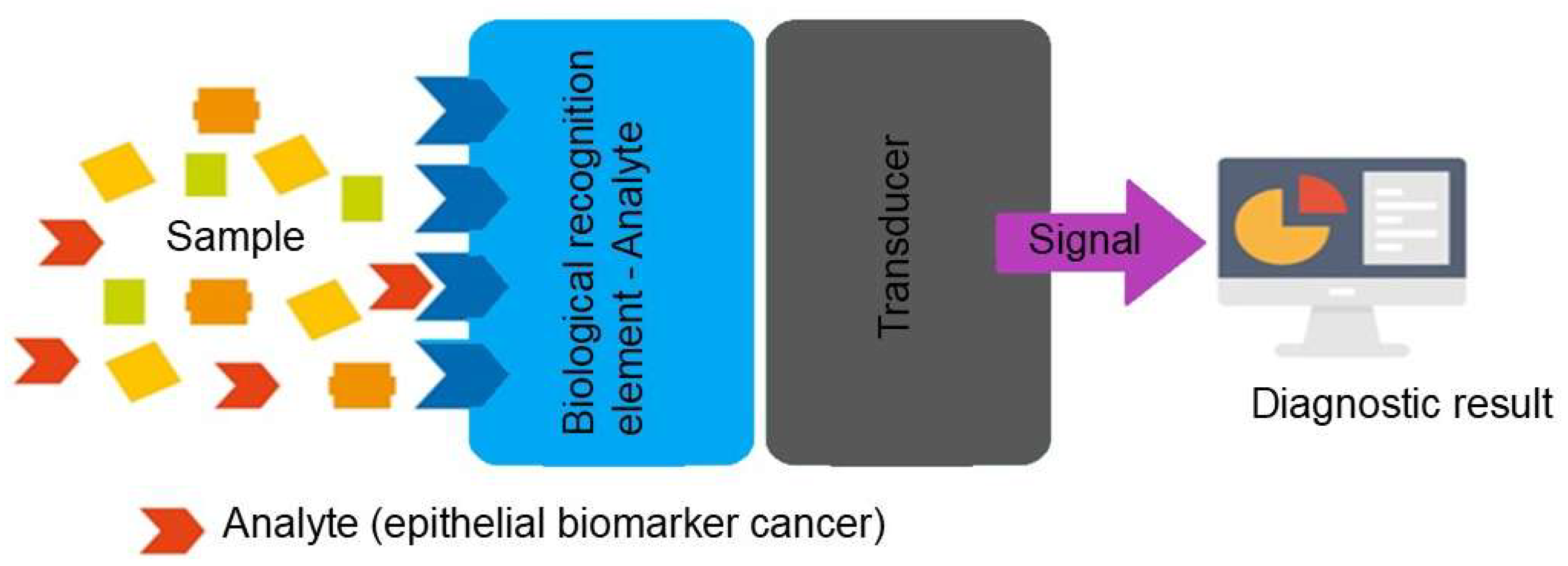

2. Electrochemical Biosensors

3. Epithelial Cancer Biomarkers

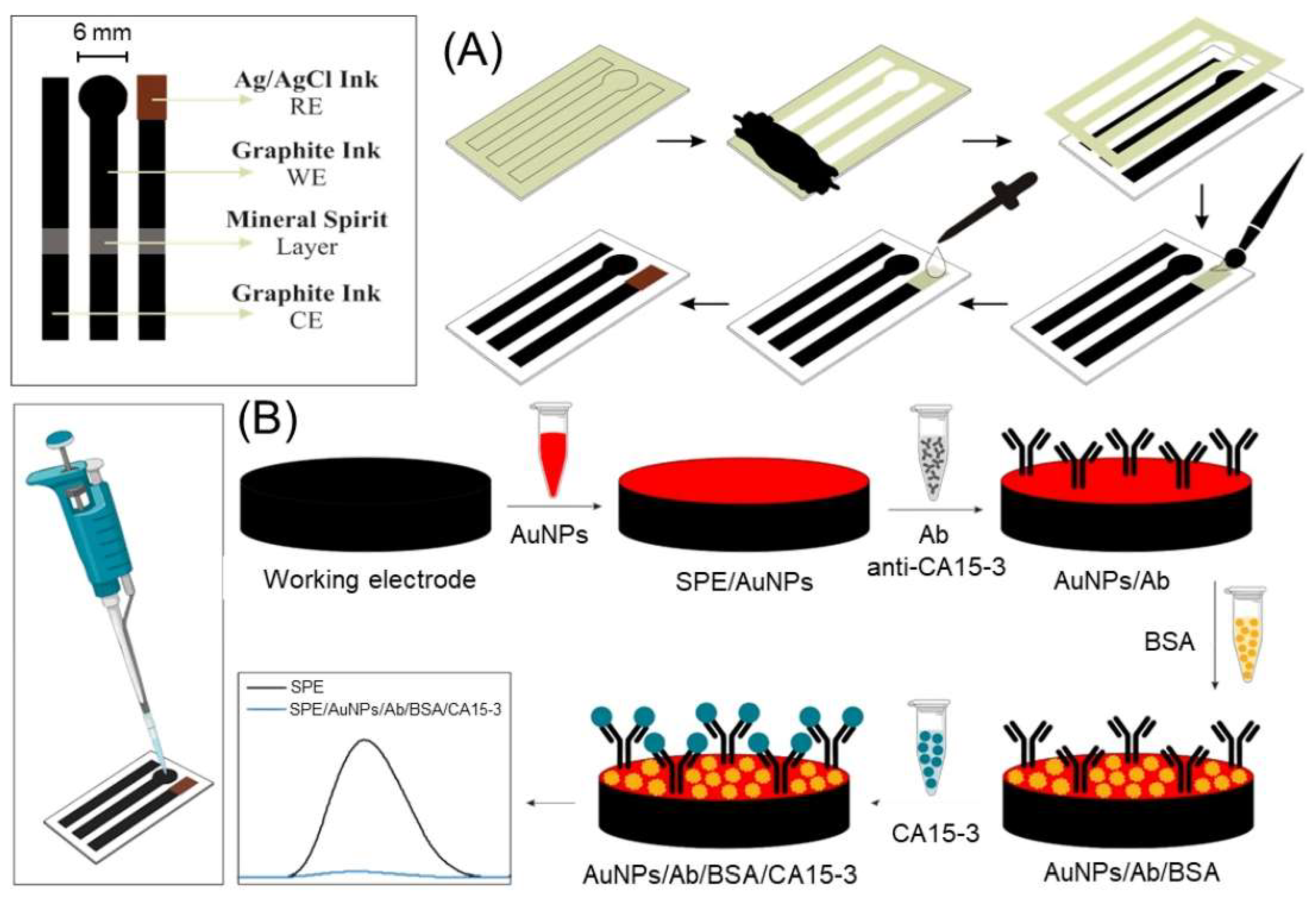

3.1. Cancer Antigen (CA)

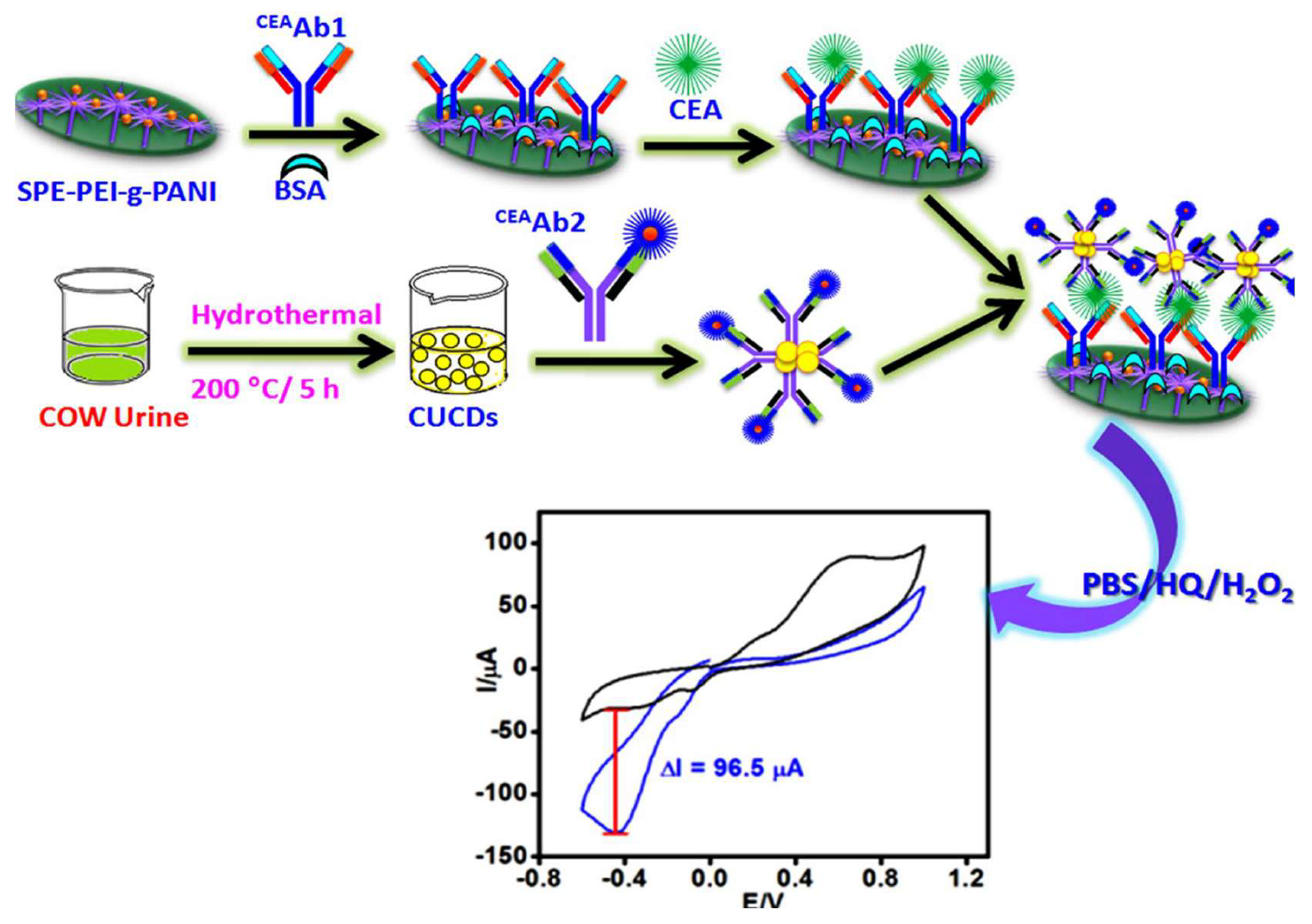

3.2. CEA

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4-mercaptophenyl /AuNPs | Aptasensor | 0.5-10 ng mL-1 | 0.102 ng mL-1 | Serum | [7] |

| ZrO2-AuNPs | Aptasensor | 0.01-104 pg mL-1 | 42.504 fg mL-1 | Serum | [42] |

| Fc/PdPt@PCN-224 | Aptasensor | 1 pg mL-1–100 ng mL-1 | 0.27 pg mL-1 | Serum | [19] |

| Au@MoS2@rGO | Aptasensor | 0.1 pg mL-1–100 ng mL-1 | 0.019 pg mL-1 | Serum | [44] |

| IDE | Aptasensor | 0.002 ng mL-1 - 2 ng mL-1 |

3.8 pg mL-1 | Serum | [43] |

| MNC | Immunosensor | 500 fM–50 nM | 500 fM | Serum | [38] |

| Au-MoO3-Chi | Immunosensor | 0.001–0.01 ng mL-1 | 0.5 pg mL-1 | Serum | [35] |

| CDs | Immunosensor | 0.5-50 ng mL-1 | 10 pg mL-1 | Serum | [39] |

| Fe3O4/MWCNTs | Immunosensor | 0.005–2.5 ng mL-1 | 0.3 pg mL-1 | Serum | [37] |

| MoO3-rGO-IL | Immunosensor | 25 fg mL-1–100 ng mL-1 | 1.19 fg mL-1 | Serum | [36] |

| AuNPs | Immunosensor | 0.1-40 ng mL-1 | 0.03 ng mL-1 | Serum | [45] |

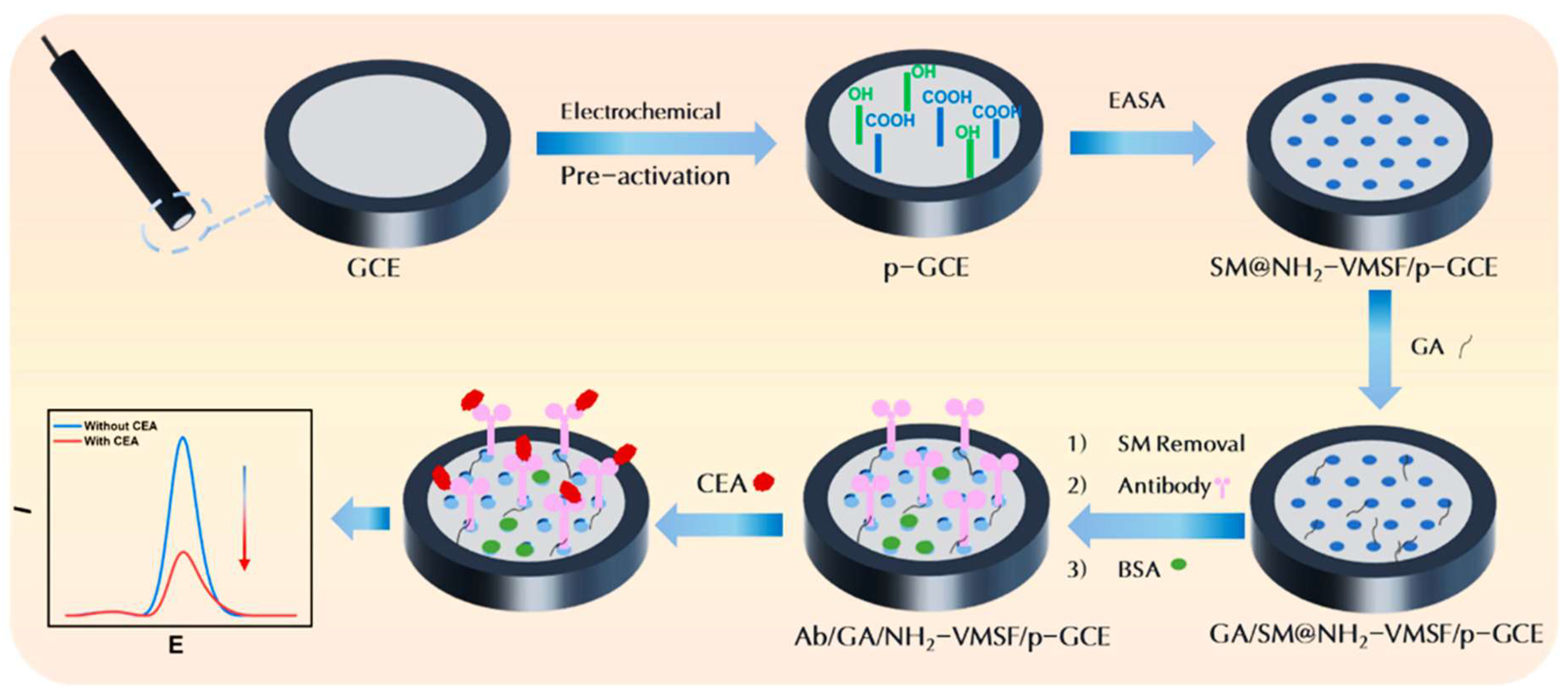

| VMSF | Immunosensor | 0.01 ng mL-1–100 ng mL-1 | 6.3 pg mL-1 | Serum | [46] |

| ZnONPs/GNPs | Immunosensor | 0.5-10.0 ng mL-1 | 0.44 ng mL-1 | Serum | [40] |

| MX@CNT | Immunosensor | 0.005–1.0 ng mL-1 | 1.6 pg mL-1 | Serum | [41] |

| Note: Au-MoO3-Chi: gold nanoparticles-molybdenum trioxide-chitosan; AuNPs: gold nanoparticles; FcPdPt@PCN-224: ferrocene PdPt nanoparticles@Zr-based porphyrinic metal–organic framework; Au@MoS2@rGO: gold@disulfide@graphene oxide; MNC: nitrogen-rich mesoporous carbon; CDs: carbon dots; Fe3O4: iron oxide nanoparticles; MWCNTs: multi-walled carbon nanotubes; MoO3-rGO-IL: ionic liquid-functionalized molybdenum trioxide-reduced graphene oxide; ZrO2-AuNPs: zirconia-gold nanoparticles; IDE: interdigitated gold electrode; VMSF: ordered mesoporous silica film; ZnONPs: flower-like zinc oxide nanoparticles; GNPs: graphene nanoplatelets; MX@CNT: carbon nanotube-bridged Ti3C2Tx MXene. | |||||

3.3. PSA

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNPs/2D-MoS2 | Immunosensor | 0-10 ng mL-1 | 3.58 pg mL-1 | Serum | [47] |

| AuNPs | Immunosensor | 0.1-50000 pg mL-1 | 0.083 pg mL-1 | Serum | [48] |

| CDs@PANI | Immunosensor | 0.01-60 ng mL-1 | 20 pg mL-1 | Serum | [49] |

| AuNPs | Immunosensor | 10-104 pg mL-1 | 102 fg mL-1 | Serum | [51] |

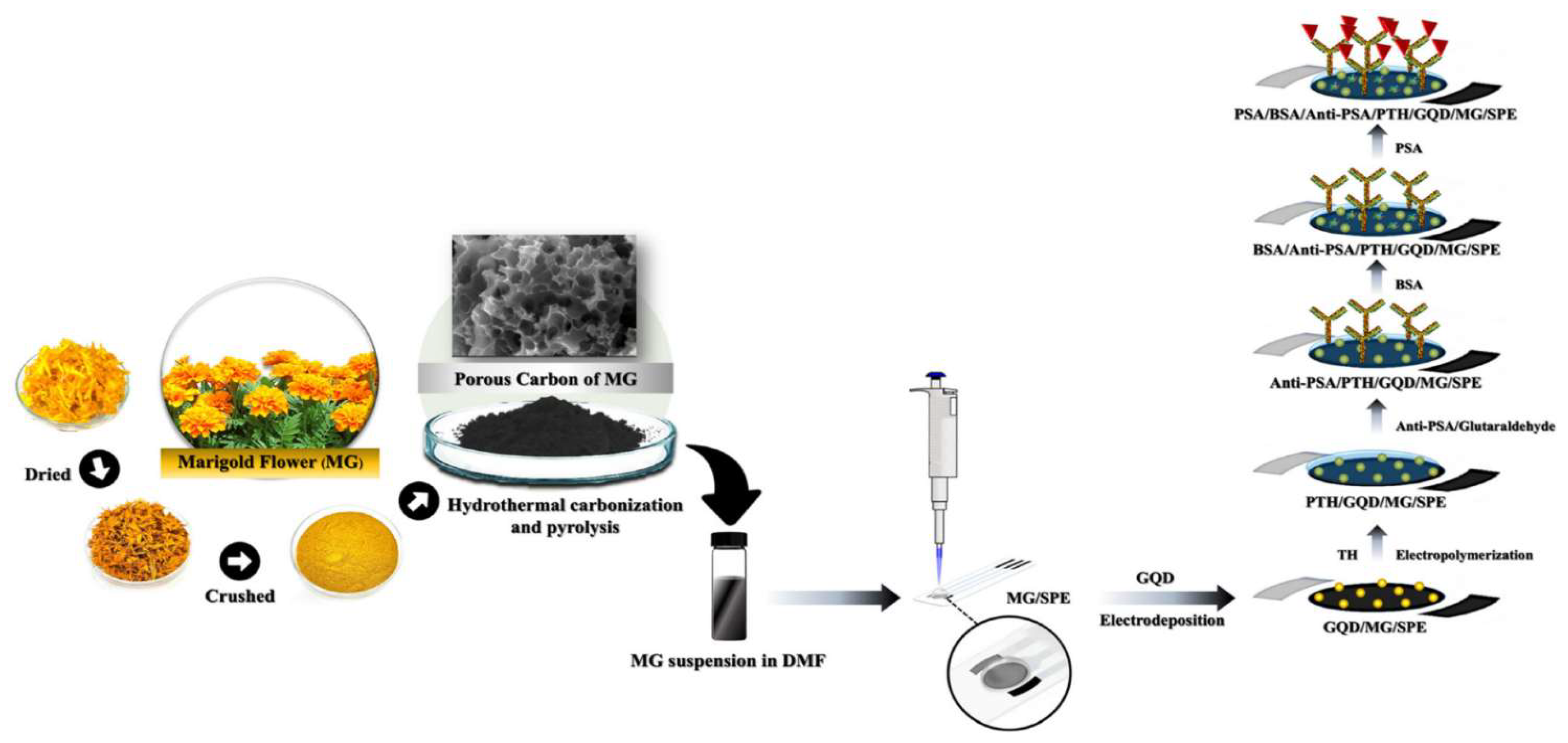

| GQDs | Immunosensor | 0.0125-1.0 ng mL-1 | 0.005 ng mL-1 | Serum | [56] |

| 2FcP-GA-GDY(Fe)@NMIL-B | Peptide biosensor | 10 fg mL-1-50 ng mL-1 | 0.94 fg mL-1 | Serum | [52] |

| AuNPs | Protein biosensor | 0.01-100 ng mL-1 | 3.574 pg mL-1 | Serum | [53] |

| Nanopore/MIPs | Aptasensor | 5-100 ng mL-1 | 0.42 ng mL-1 | Serum | [50] |

| rGO/g-C3N4/AuNPs | Aptasensor | 2.5–12.5 pM | 0.44 fM | Serum | [54] |

| α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4@Au | Aptasensor | 100 fg mL-1-100 ng mL-1 | 0.78 pg mL-1 | Serum | [55] |

| Note: AuNPs/2D-MoS2: gold nanoparticles/two-dimensional molybdenum disulfide; CDs@PANI: carbon dots functionalized polyaniline; MIPs: molecularly imprinted polymers; 2FcP-GA-GDY(Fe)@NMIL-B: Fe-Graphdiyne into a metal-organic framework material NH2-MIL88B(Fe); rGO/g-C3N4: reduced graphene oxide/graphitic carbon nitride; α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4@Au: magnetic nanoparticles/gold nanoparticles; GQDs: Graphene quantum dots. | |||||

3.4. RNA, DNA, EVs y Cells

3.4.1. miRNA Detection: A Focus on Early Cancer Biomarkers

3.4.2. Extracellular Vesicles Detection: Non-Invasive Biomarkers

3.4.3. Tumor Cell and Circulating Tumor DNA Detection: Early Cancer Screening

3.5. Other Relevant Epithelial Biomarkers

| Nanomaterial | Biomarker type | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au | EGFR | Aptasensor | 0.1-1000 ng mL-1 | 0.18 ng mL-1 | Serum | [88] |

| Magnetic NPs | EGFR | Aptasensor | 10 fM-1 µM | 372 aM | Serum | [89] |

| Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3 | HER 2 | Aptasensor | 10 fg mL-1–5×106 fg mL-1 | 4.1 fg mL-1 | Serum | [92] |

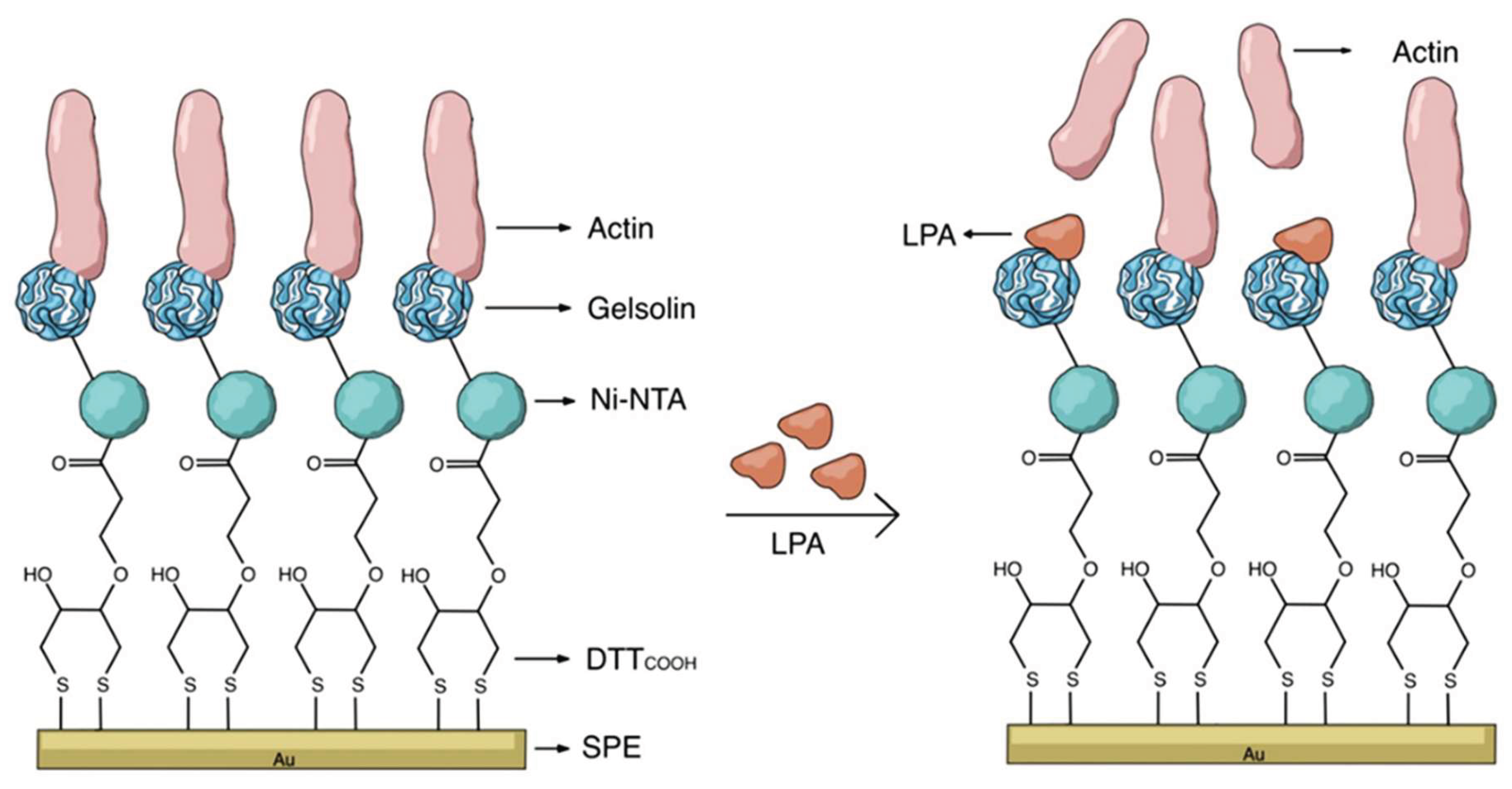

| DTTCOOH | LPA | Biosensor | 0.01–10 μM | 0.9 µM | Serum | [98] |

| SiO2NPs | EGFR | Immunosensor | 1-1000 ng mL-1 | 0.06 ng mL-1 | Serum | [90] |

| Gr/CNT | CLDN18.2 | Immunosensor | 0.1–100 ng mL-1 and 0.01 ng mL-1–100 ng mL-1 | 7.9 pg mL-1 for CNT and 0.104 ng mL-1 for Gr | Serum | [93] |

| GO | PG I | Immunosensor | 0.01–200 ng mL-1 | 9.1 pg mL-1 | Serum | [94] |

| rGO/Fe3O4NPs/AuPtNPs | PGI/PGII | Immunosensor | 5 pg mL-1–100 ng mL-1 for PG I and 50 pg mL-1–200 ng mL-1 for PG II | 1.67 pg mL-1 for PG I and 16.67 pg mL-1 for PG II | Serum | [95] |

| PtNPs/Fe3O4NPs | NSE | Immunosensor | 1.0 fg mL-1–10 ng mL-1 | 0.34 fg mL-1 | Serum | [96] |

| 3-PTAA/FLG | AFP | Immunosensor | 0.0001–250 ng mL-1 | 0.047 pg mL-1 | Serum | [12] |

| GH-PtCoNi BNCs | AFP | Immunosensor | 0.1 to 105 pg mL-1 | 0.017 pg mL-1 | Serum | [97] |

| ITO-PET/3-APTES | HE4 | Immunosensor | 1 pg/mL to 3000 pg mL-1 | 0.094 pg mL-1 | Serum | [16] |

| HOOC-MBs | TIMP-1/GDF-15 | Immunosensor | 43.4–2500 pg mL-1 | 13 pg mL-1 | Plasma | [11] |

| Au/CoNPs-3D MCF | CYFRA21-1 | Immunosensor | 0.0001–100 ng mL-1 | 0.0224 pg mL-1 | Serum | [99] |

4. Conclusions

5. Key Challenges and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Malecka-Baturo, K.; Grabowska, I. Efficiency of Electrochemical Immuno- vs. Apta(Geno)Sensors for Multiple Cancer Biomarkers Detection. Talanta 2025, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, P.; Vatankhahan, H.; Zare-Hoseinabadi, A.; Ferdosi, F.; Ehtiati, S.; Heidari, P.; Dorostgou, Z.; Movahedpour, A.; Baktash, A.; Rajabivahid, M.; et al. Electrochemical Biosensors for Early Detection of Breast Cancer. Clinica Chimica Acta 2025, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhi, S.; Ghasemi, H.; Alizadeh, M.; Movahedpour, A.; Vahedi, F.; Fattahi, M.; Aiiashi, S.; Khatami, S.H. MiRNA-Based Electrochemical Biosensors for Ovarian Cancer. Clinica Chimica Acta 2025, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yao, W.; Sun, W.; Fan, Y.; Xiao, J.; Wang, T.; Huang, K.; Liu, L.; Wang, X.; Jiang, H. Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Analysis Platform for Tumor Cells and Biomarkers Detection. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2024, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Rabbani, G.; Zamzami, M.A.; Hosawi, S.; Baothman, O.A.; Altayeb, H.; Akhtar, M.S.N.; Ahmad, V.; Khan, M.V.; Khan, M.E.; et al. An Affordable Label-Free Ultrasensitive Immunosensor Based on Gold Nanoparticles Deposited on Glassy Carbon Electrode for the Transferrin Receptor Detection. Int J Biol Macromol 2024, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunati, S.; Giannetto, M.; Pedrini, F.; Nikolaou, P.; Donofrio, G.; Bertucci, A.; Careri, M. A Novel Magnetic Ligand-Based Assay for the Electrochemical Determination of BRD4. Talanta 2024, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkal-Aytemur, A.; Mülazımoğlu, İ.E.; Üstündağ, Z.; Caglayan, M.O. A Novel Aptasensor Platform for the Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen Using Quartz Crystal Microbalance. Talanta 2024, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Q.Y.; Xu, B.F.; Xu, F.; Wang, A.J.; Mei, L.P.; Wu, L.; Song, P.; Feng, J.J. Dual Amplification for PEC Ultrasensitive Aptasensing of Biomarker HER-2 Based on Z-Scheme UiO-66/CdIn2S4 Heterojunction and Flower-like PtPdCu Nanozyme. Talanta 2024, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Zhu, T.F.; Dong, M.; Liu, L. Aggregation-Induced Signal Amplification Strategy Based on Peptide Self-Assembly for Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Detection of Melanoma Biomarker. Anal Chim Acta 2024, 1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmi Narayanan, M.; Prabhu, K.; Ponpandian, N.; Viswanathan, C. Cu Encrusted RF Sputtered ZnO Thin Film Based Electrochemical Immunosensor for Highly Sensitive Detection of IL-6 in Human Blood Serum. Microchemical Journal 2024, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejerina-Miranda, S.; Gamella, M.; Pedrero, M.; Montero-Calle, A.; Rejas, R.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Barderas, R.; Campuzano, S. Dual Immunoplatform to Assess Senescence Biomarkers TIMP-1 and GDF-15: Advancing in the Understanding of Colorectal Cancer. Electrochim Acta 2024, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, B.; Roy, A.; Paul, D.; Panda, S.; Das, B.; Karmakar, S.; Dutta, K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Chattopadhyay, D. 3-Polythiophene Acetic Acid Nanosphere Anchored Few-Layer Graphene Nanocomposites for Label-Free Electrochemical Immunosensing of Liver Cancer Biomarker. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2024, 7, 485–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, D.; Dubey, N.; Yadav, A.K.; Saraya, A.; Sharma, R.; Solanki, P.R. Disposable Paper-Based Screen-Printed Electrochemical Immunoplatform for Dual Detection of Esophageal Cancer Biomarkers in Patients’ Serum Samples. Mater Adv 2024, 5, 2153–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarić, S.; Schobesberger, S.; Velicki, L.; Milovančev, A.; Nikolić, S.; Ertl, P.; Bobrinetskiy, I.; Knežević, N. Direct Electrochemical Reduction of Graphene Oxide Thin Film for Aptamer-Based Selective and Highly Sensitive Detection of Matrix Metalloproteinase 2. Talanta 2024, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokni, M.; Tlili, A.; Khalij, Y.; Attia, G.; Zerrouki, C.; Hmida, W.; Othmane, A.; Bouslama, A.; Omezzine, A.; Fourati, N. Designing a Simple Electrochemical Genosensor for the Detection of Urinary PCA3, a Prostate Cancer Biomarker. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vural, B.; Çalışkan, M.; Bilgi Kamaç, M.; Sezgintürk, M.K. A Disposable and Ultrasensitive Immunosensor for the Detection of HE4 in Human Serum Samples. Chemical Papers 2024, 78, 3871–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Suonanmu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Q.; Tao, F.; Li, C.; Wang, F. An Integrated Microfluidic Cytosensor Coupled with Self-Calibration Electrochemical/Colorimetric Dual-Signal Output for Sensitive and Accurate Detection of Hepatoma Cells. Sens Actuators B Chem 2024, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Xiao, W.; Shen, L.; Shi, X.; Li, J. An Electrochemical Method Based on CRISPR-Cas12a and Enzymatic Reaction for the Highly Sensitive Detection of Tumor Marker MUC1 Mucin. Analyst 2024, 149, 3920–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, S.S.; Li, X.J.; Ma, R.N.; Shang, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, H.Q.; Jia, L.P.; Wang, H.S. A Novel Dual-Signal Output Strategy for POCT of CEA Based on a Smartphone Electrochemical Aptasensing Platform. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinchia, J.; Blázquez-García, M.; Torrente-Rodríguez, R.M.; Ruiz-Valdepeñas Montiel, V.; Serafín, V.; Rejas-González, R.; Montero-Calle, A.; Orozco, J.; Pingarrón, J.M.; Barderas, R.; et al. Disposable Electrochemical Immunoplatform to Shed Light on the Role of the Multifunctional Glycoprotein TIM-1 in Cancer Cells Invasion. Talanta 2024, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, M.; Bilgi, M. A Disposable Impedimetric Immunosensor for the Analysis of CA125 in Human Serum Samples. Biomed Microdevices 2024, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Wang, L.; Xie, C.; Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, T.; Liu, S. A Disposable Ultrasensitive Immunosensor Based on MXene/NH2-CNT Modified Screen-Printed Electrode for the Detection of Ovarian Cancer Antigen CA125. Talanta 2025, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H. Application of a Novel and Effective Aptasensor for Electrochemical Monitoring of Cancer Antigen 125 in Human Serum. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 109, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghiani, I.; Souza, L. V.; Bach-Toledo, L.; Faria, A.M.; Ortega, P.P.; Amoresi, R.A.C.; Simões, A.Z.; Mazon, T. Application of NiFe2O4 Nanoparticles towards the Detection of Ovarian Cancer Marker. Mater Res Bull 2024, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Er, O.F.; Kivrak, H.; Alpaslan, D.; Dudu, T.E. One-Step Electrochemical Sensing of CA-125 Using Onion Oil-Based Novel Organohydrogels as the Matrices. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 17919–17930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Q.; Wu, R.; Wang, J.; Zeng, T.; Yang, L. An Ultrasensitive Sandwich-Type Electrochemical Immunosensor Based on RGO-TEPA/ZIF67@ZIF8/Au and AuPdRu for the Detection of Tumor Markers CA72-4. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Gao, H.; Qiu, R.; Zhang, H.; Ren, X.; Qi, X.; Miao, M.; Rui, C.; Chang, D.; Pan, H. A Novel Ratiometric Electrochemical Immunosensor for the Detection of Cancer Antigen 125 Based on Three-Dimensional Carbon Nanomaterial and MOFs. Microchemical Journal 2024, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Bilal, S.; Naz, I.; Nawaz, M.H.; Andreescu, S.; Jubeen, F.; Arif, A.; Hayat, A. A Multifunctional N-GO/PtCo Nanocomposite Bridged Carbon Fiber Interface for the Electrochemical Aptasensing of CA15-3 Oncomarker. Anal Biochem 2024, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos Oliveira, D.; Oliveira, A.S.R.; Mendonça, P.V.; Coelho, J.F.J.; Moreira, F.T.C.; Sales, M.G.F. An Innovative Approach for Tailoring Molecularly Imprinted Polymers for Biosensors—Application to Cancer Antigen 15-3. Biosensors (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Cai, S.; Chen, X. Atomically Co-Dispersed Nitrogen-Doped Carbon for Sensitive Electrochemical Immunoassay of Breast Cancer Biomarker CA15-3. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srilikhit, A.; Kongkeaw, S.; Cotchim, S.; Janduang, S.; Wannapob, R.; Kanatharana, P.; Thavarungkul, P.; Limbut, W. Carcinoembryonic Antigen and Cancer Antigen 125 Simultaneously Determined Using a Fluidics-Integrated Dual Carbon Electrode. Microchemical Journal 2024, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, A.E.F.; Pereira, A.C.; Resende, M.A.C.; Ferreira, L.F. Disposable Voltammetric Immunosensor for Determination and Quantification of Biomarker CA 15-3 in Biological Specimens. Analytica 2024, 5, 74–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Pang, W.; Huang, S.; Deng, M.; Yao, J.; Huang, Q.; Jin, M.; Shui, L. Integrated Biosensor Array for Multiplex Biomarkers Cancer Diagnosis via In-Situ Self-Assembly Carbon Nanotubes with an Ordered Inverse-Opal Structure. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzin, M.A.; Naghib, S.M. Paper-Based Immunosensor Integrated with Bioinspired Cu-Polydopamine Nanozyme for Voltammetric Detection of CA-15-3 Tumor Marker. Sensors and Actuators Reports 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotchim, S.; Kongkaew, S.; Thavarungkul, P.; Kanatharana, P.; Limbut, W. A Dual-Electrode Label-Free Immunosensor Based on in Situ Prepared Au–MoO3-Chi/Porous Graphene Nanoparticles for Point-of-Care Detection of Cholangiocarcinoma. Talanta 2024, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, P.; Abubakar Sadique, M.; Yadav, S.; Khan, R.; Kumar Srivastava, A. Electrochemical Nanobiosensor of Ionic Liquid Functionalized MoO3-RGO for Sensitive Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen. Chempluschem 2024, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsazar, A.; Moghaddam, M.S.; Asadi, A.; Mahdavi, M. Development and Performance Assessment of a Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotube/Iron Oxide Nanocomposite-Based Electrochemical Immunosensor for Precise and Ultrasensitive Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen. J Appl Electrochem 2024, 54, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, D.; Kaur, S.; Nagaiah, T.C. Realizing the Label-Free Sensitive Detection of Carcinoembryogenic Antigen (CEA) in Blood Serum via a MNC-Decorated Flexible Immunosensor. Analytical Methods 2024, 16, 1473–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chellachamy Anbalagan, A.; Korram, J.; Doble, M.; Sawant, S.N. Bio-Functionalized Carbon Dots for Signaling Immuno-Reaction of Carcinoembryonic Antigen in an Electrochemical Biosensor for Cancer Biomarker Detection. Discover Nano 2024, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janduang, S.; Cotchim, S.; Kongkaew, S.; Srilikhit, A.; Wannapob, R.; Kanatharana, P.; Thavarungkul, P.; Limbut, W. Synthesis of Flower-like ZnO Nanoparticles for Label-Free Point of Care Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen. Talanta 2024, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, W.; Hao, J.; Wu, K. Ultrasensitive Carbon Nanotube-Bridged MXene Conductive Network Arrays for One-Step Homogeneous Electrochemical Immunosensing of Tumor Markers. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, M.S.; Meng, F.; Zhang, R.; Huang, L.; Qian, K. Integrating Zirconia-Gold Hybrid into Aptasensor Capable of Ultrasensitive and Robust Carcinoembryonic Antigen Determination. Electrochim Acta 2024, 507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunussova, N.; Tilegen, M.; Pham, T.T.; Kanayeva, D. Rapid Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen by Means of an Electrochemical Aptasensor. iScience 2024, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Cao, T.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Luo, C. An Electrochemical Aptasensor Based on Ce-MOF@COF to Detect Carcinoembryonic Antigen. New Journal of Chemistry 2024, 48, 10628–10635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Shen, J.; Zhang, B.; Xue, T.; Lv, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, G. A Dual-Mode Homogeneous Electrochemical-Colorimetric Biosensing Sensor for Carcinoembryonic Antigen Detection Based on a Microfluidic Paper-Based Analysis Device. Analytical Methods 2024, 16, 7372–7380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, H.; Xi, F.; Lu, C. Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of Carcinoembryonic Antigen Based on Biofunctionalized Nanochannel Modified Carbonaceous Electrode. Molecules 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaiwong, P.; Jakmunee, J.; Pimalai, D.; Ounnunkad, K.; Bamrungsap, S. An Electrochemical/SERS Dual-Mode Immunosensor Using TMB/Au Nanotag and Au@2D-MoS2 Modified Screen-Printed Electrode for Sensitive Detection of Prostate Cancer Biomarker. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2024, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uruc, S.; Dokur, E.; Gorduk, O.; Sahin, Y. Disposable and Ultrasensitive Label-Free Gold Nanoparticle Patterned Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene-Co-3-Methylthiophene) Electrode for Electrochemical Immunosensing of Prostate-Specific Antigen. New Journal of Chemistry 2024, 48, 10415–10426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellachamy Anbalagan, A.; Korram, J.; Koyande, P.; Khan, S.; Agrawal, R.; Sawant, S.N. Carbon Dots Functionalized Polyaniline as Efficient Sensing Platform for Cancer Biomarker Detection. Diam Relat Mater 2024, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Liang, R.; Qin, W. Chronopotentiometric Nanopore Sensor Based on a Stimulus-Responsive Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for Label-Free Dual-Biomarker Detection. Anal Chem 2024, 96, 9370–9378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo-Fernández, G.; Cid-Barrio, L.; Fernández-Argüelles, M.T.; de la Escosura-Muñiz, A.; Soldado, A.; Costa-Fernández, J.M. Controlled Silver Electrodeposition on Gold Nanoparticle Antibody Tags for Ultrasensitive Prostate Specific Antigen Sensing Using Electrochemical and Optical Smartphone Detection. Talanta 2024, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Li, J.; Wu, W.; Yu, X.; Tao, M.; Han, Y.; Lin, Y.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, L.; Zhao, Z.; et al. Dual Chemical Bonding Construction of Electrochemical Peptide Sensor Based on GDY/MOFs(Fe) Composite for Ultra-Low Determination of Prostate-Specific Antigen. Talanta 2024, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.F.A.; Arshad, M.K.M.; Gopinath, S.C.B.; Fathil, M.F.M.; Sarry, F.; Ibau, C.; Elmazria, O.; Hage-Ali, S. Interdigitated Impedimetric-Based Maackia Amurensis Lectin Biosensor for Prostate Cancer Biomarker. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi Tabar, F.; pourmadadi, M.; Yazdian, F.; Rashedi, H.; Rahdar, A.; Fathi-karkan, S.; Romanholo Ferreira, L.F. Ultrasensitive Aptamer-Based Electrochemical Nanobiosensor in Diagnosis of Prostate Cancer Using 2D:2D Reduced Graphene Oxide/Graphitic Carbon Nitride Decorated with Au Nanoparticles. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Reports 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Z.; Sun, L.; Li, S.; Liu, R. Ultrasensitive Detection of PSA in Human Serum Using Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensor with Magnetically Induced Self-Assembly Based on α-Fe2O3/Fe3O4@Au Nanocomposites. Microchemical Journal 2024, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotchim, S.; Kongkaew, S.; Thavarungkul, P.; Kanatharana, P.; Limbut, W. An Unlabeled Electrochemical Immunosensor Uses Poly(Thionine) and Graphene Quantum Dot-Modified Activated Marigold Flower Carbon for Early Prostate Cancer Detection. Biosensors (Basel) 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

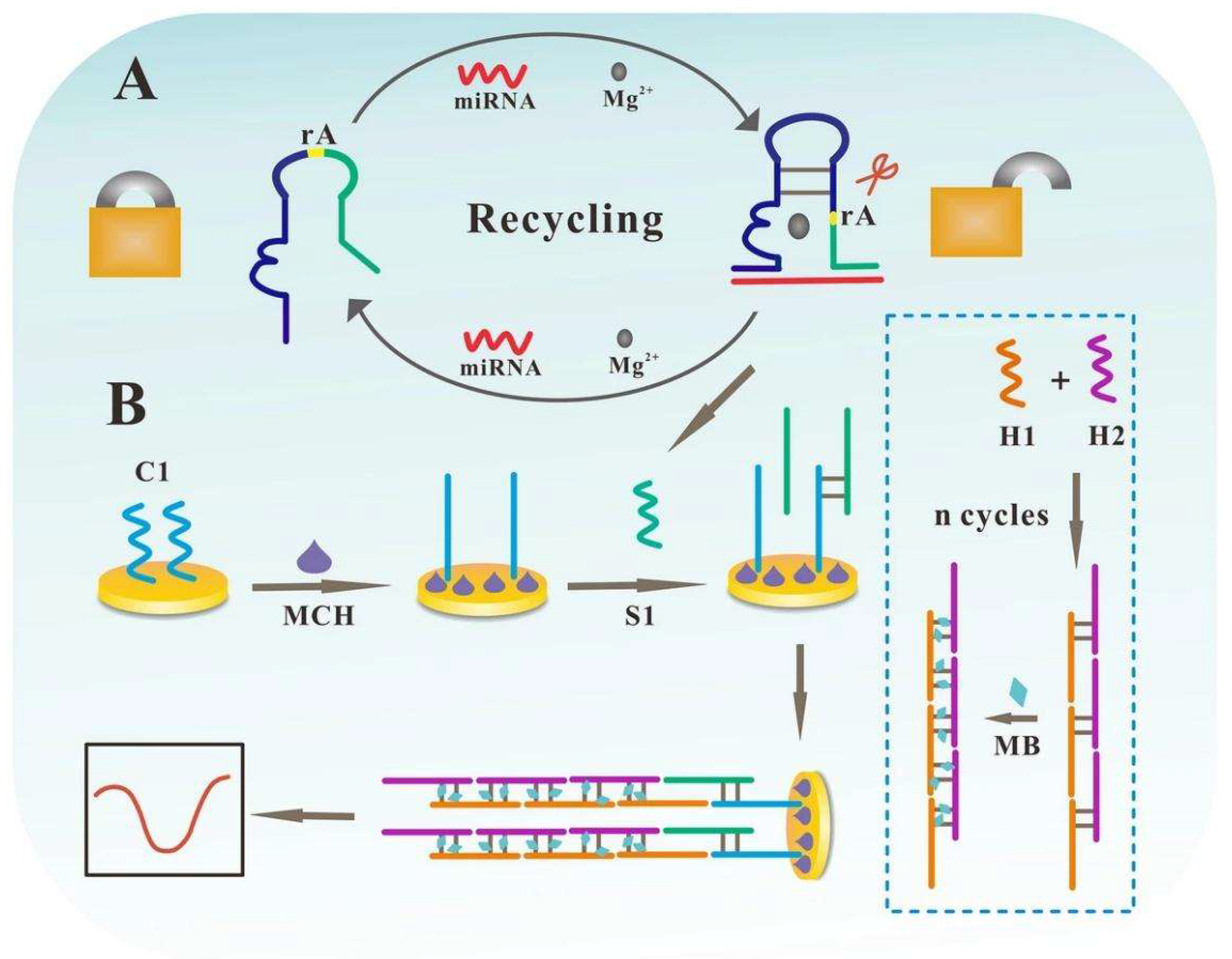

- Sasa, G.B.K.; He, B.; Chen, C.; Chen, Z.; Li, S.; Tan, C.S. A Dual-Targeted Electrochemical Aptasensor for Neuroblastoma-Related MicroRNAs Detection. Talanta 2024, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Ding, S.; Zhao, Y.; Xu, M.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, C. A Highly Sensitive and Robust Electrochemical Biosensor for MicroRNA Detection Based on PNA-DNA Hetero-Three-Way Junction Formation and Target-Recycling Catalytic Hairpin Assembly Amplification. Talanta 2024, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Tang, H.; Gao, G.; Qian, Y.; Shen, Q.; Liang, L.; Cao, H. Al-Doped ZnO Nanostars for Electrochemical MiRNA-21 Biosensors. J Electrochem Soc 2024, 171, 087509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Zhou, Q.; Shi, J.; Gao, H.; Huang, D.; Xue, H.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; et al. CRISPR-Empowered Electrochemical Biosensor for Target Amplification-Free and Sensitive Detection of MiRNA. Talanta 2024, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.S.; Govindasamy, M.; Chinnapaiyan, S.; Lin, Y.T.; Lu, S.Y.; Samukawa, S.; Huang, C.H. Electrochemical Biosensor Based on an Atomic Layered Composite of Graphene Oxide/Graphene as an Electrode Material towards Selective and Sensitive Detection of MiRNA-21. Microchemical Journal 2024, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

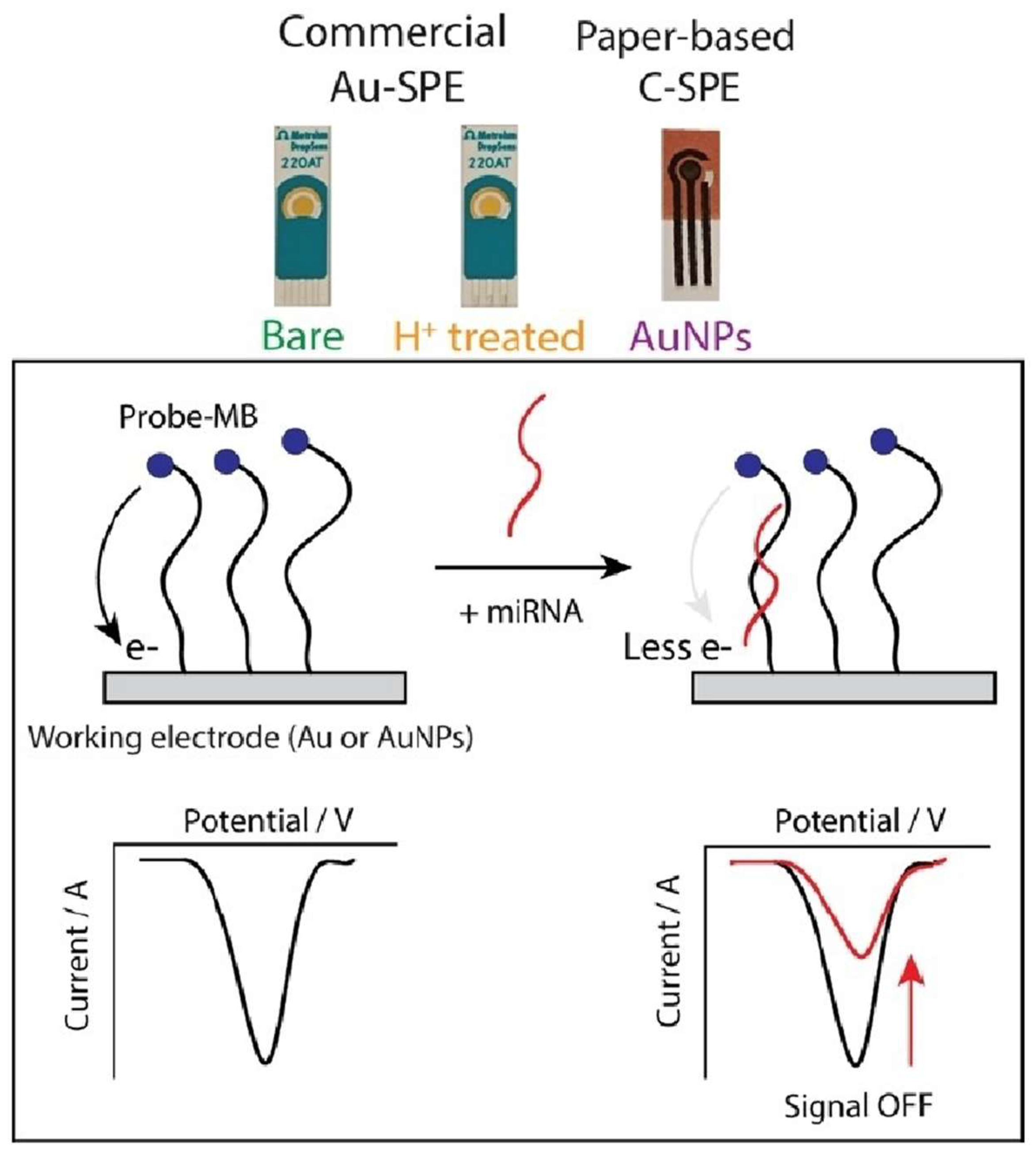

- Raucci, A.; Cimmino, W.; Romanò, S.; Singh, S.; Normanno, N.; Polo, F.; Cinti, S. Electrochemical Detection of MiRNA Using Commercial and Hand-Made Screen-Printed Electrodes: Liquid Biopsy for Cancer Management as Case of Study. ChemistryOpen 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; George, M.; Neppolian, B.; Das, J. Electrochemical Detection of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Mir-223 Biomarker Employing Gold/MWCNT Nanocomposite–Based Sandwich Platform. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2025, 29, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimmino, W.; Raucci, A.; Grosso, S.P.; Normanno, N.; Cinti, S. Enhancing Sensitivity towards Electrochemical MiRNA Detection Using an Affordable Paper-Based Strategy. Anal Bioanal Chem 2024, 416, 4227–4236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chen, J.; Yu, L.; Li, J.; You, S.; Zheng, Y.; Zhuang, W.; Qiu, B.; Huang, Y. Detection of Fucosylated Extracellular Vesicles MiR-4732-5p Related to Diagnosis of Early Lung Adenocarcinoma by the Electrochemical Biosensor. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulgerbaki, C.; Uygun Oksuz, A. Iron Oxide/Poly(3,4-Ethylenedioxythiophene): Poly(Styrene Sulfonate) Glassy Carbon Electrode as a Novel Label-Free Electrochemical MicroRNA-21 Sensor. Instrum Sci Technol 2024, 52, 67–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Luo, Z.; Liu, J.; Bao, T.; Wu, Z.; Wen, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Magnetic Beads-Assisted Split DNAzyme Cleavage-Driven Assembly of Functionalized Covalent Organic Frameworks for Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Detection of MicroRNA. Sens Actuators B Chem 2024, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Wei, G.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, J.; Kong, J.; Zhang, X. Organic Small Molecule Catalytic PET-RAFT Electrochemical Signal Amplification Strategy for MiRNA-21 Detection. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raucci, A.; Cimmino, W.; Grosso, S.P.; Normanno, N.; Giordano, A.; Cinti, S. Paper-Based Screen-Printed Electrode to Detect MiRNA-652 Associated to Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Electrochim Acta 2024, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Hasan, E.; Barman, S.C.; Hedhili, M.N.; Alshareef, H.N.; Alsulaiman, D. Peptide Nucleic Acid-Clicked Ti3C2Tx MXene for Ultrasensitive Enzyme-Free Electrochemical Detection of MicroRNA Biomarkers. Mater Horiz 2024, 11, 5045–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Che, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, X. Primer Exchange Reaction Assisted CRISPR/Cas9 Cleavage for Detection of Dual MicroRNAs with Electrochemistry Method. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, S.; Lan, F.; Li, W.; Ji, T.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Y.; Pan, W.; Luo, S.; Xie, R. Sensitive Electrochemical Biosensor for Rapid Detection of SEV-MiRNA Based Turbo-like Localized Catalytic Hairpin Assembly. Anal Chim Acta 2024, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kivrak, E.; Kara, P. Simultaneous Detection of Ovarian Cancer Related MiRNA Biomarkers with Carboxylated Graphene Oxide Modified Electrochemical Biosensor Platform. Bioelectrochemistry 2025, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

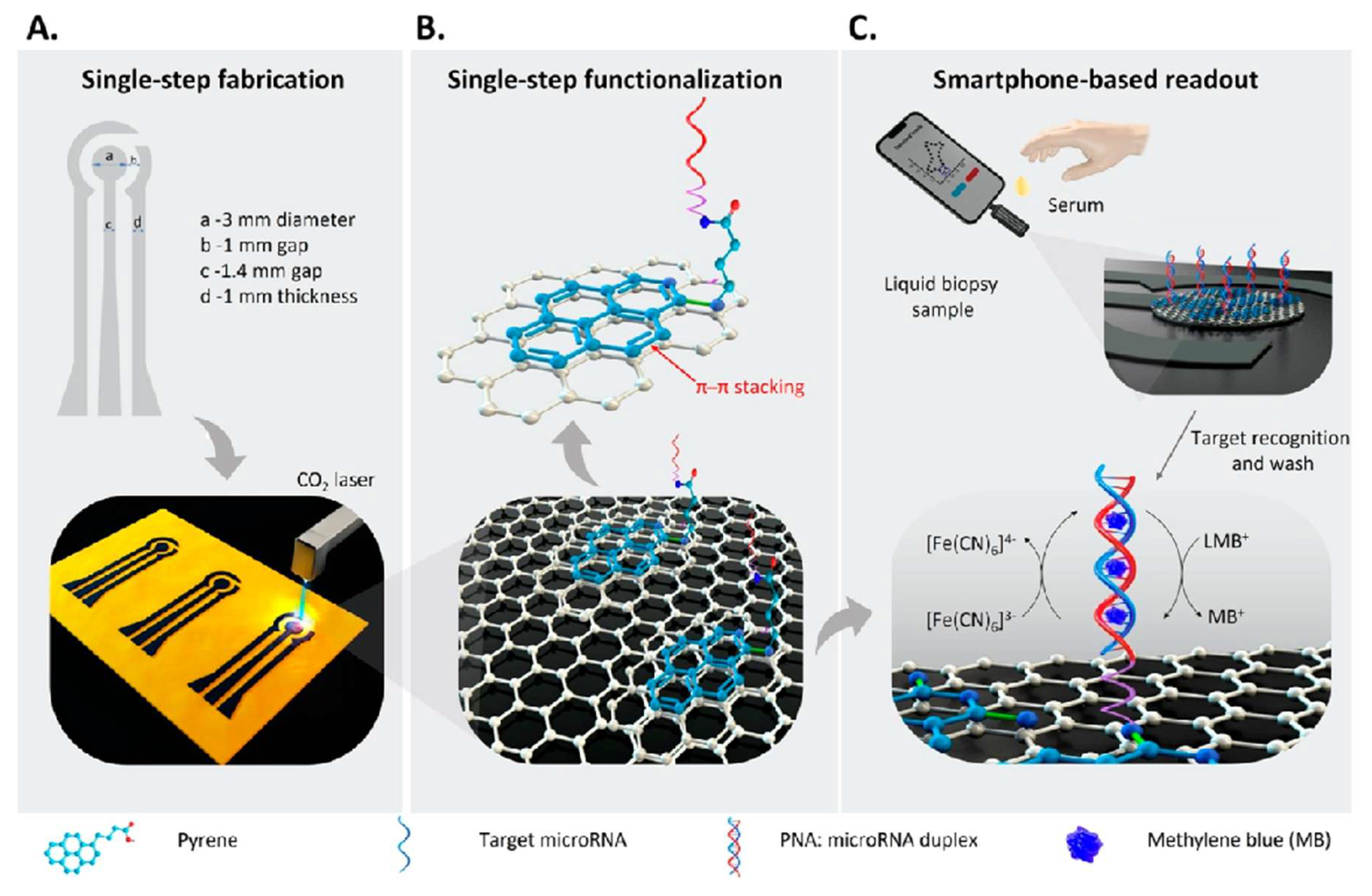

- Barman, S.C.; Ali, M.; Hasan, E.A.; Wehbe, N.; Alshareef, H.N.; Alsulaiman, D. Smartphone-Interfaced Electrochemical Biosensor for MicroRNA Detection Based on Laser-Induced Graphene with π-π Stacked Peptide Nucleic Acid Probes. ACS Mater Lett 2024, 6, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Jin, Y.; Qian, H.; Wang, Y.; Bao, T.; Wu, Z.; Wen, W.; Zhang, X.; Wang, S. Target-Driven Cascade Amplified Assembly of Covalent Organic Frameworks on Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructure with Multiplex Recognition Domains for Ultrasensitive Detection of MicroRNA. Anal Chim Acta 2024, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, J.; Xie, Q.; Chu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Q. Sensitive Detection of Exosomes by an Electrochemical Aptasensor Based on Double Nucleic Acid Amplifications. Microchemical Journal 2024, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, T.; Zhao, Y.; Li, D.; Huang, Q.; Cao, L.; Chen, J.; Chen, D.; Hu, L.; Liu, H. Colloidal Quantum Dots-Modified Electrochemical Sensor for High-Sensitive Extracellular Vesicle Detection. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wu, X.; Chen, G.; Chen, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, J.; Chen, J. Dual Amplified Electrochemical Sensing Coupling of Ternary Hybridization-Based Exosomal MicroRNA Recognition and Perchlorate-Assisted Electrocatalytic Cycle. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahraei, N.; Mazloum-Ardakani, M.; Moradi, A.; Hoseynidokht, F. Flexible Electrochemical Paper-Based Device for Detection of Breast Cancer-Derived Exosome Using Nickel Nanofoam 3D Nanocomposite. J Appl Electrochem 2024, 54, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sazaklioglu, S.A.; Torul, H.; Tamer, U.; Ensarioglu, H.K.; Vatansever, H.S.; Gumus, B.H.; Çelikkan, H. Sensitive and Reliable Lab-on-Paper Biosensor for Label-Free Detection of Exosomes by Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, T.; Mei, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Yang, X.; Wang, K. A Homogeneous Electrochemical Sensing Platform Based on DNAzyme Walker for Accurate Detection of Breast Cancer Exosomes. Sens Actuators B Chem 2024, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Zhou, F.; Yu, X.; Zhou, D.; Wang, J.; Bo, B.; Cao, Y.; Zhao, J. Electrochemical Detection of Tumor Cells Based on Proximity Labelling-Assisted Multiple Signal Amplification. Sensors and Diagnostics 2024, 3, 1542–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Che, Z.; Shi, Z.; Lv, J.; Yang, L.; Lu, T.; Lu, Y.; Shan, J.; Liu, Q. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Detection by Cell Sensor Based on Anti-GPC3 Single-Chain Variable Fragment. Advanced Devices and Instrumentation 2024, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

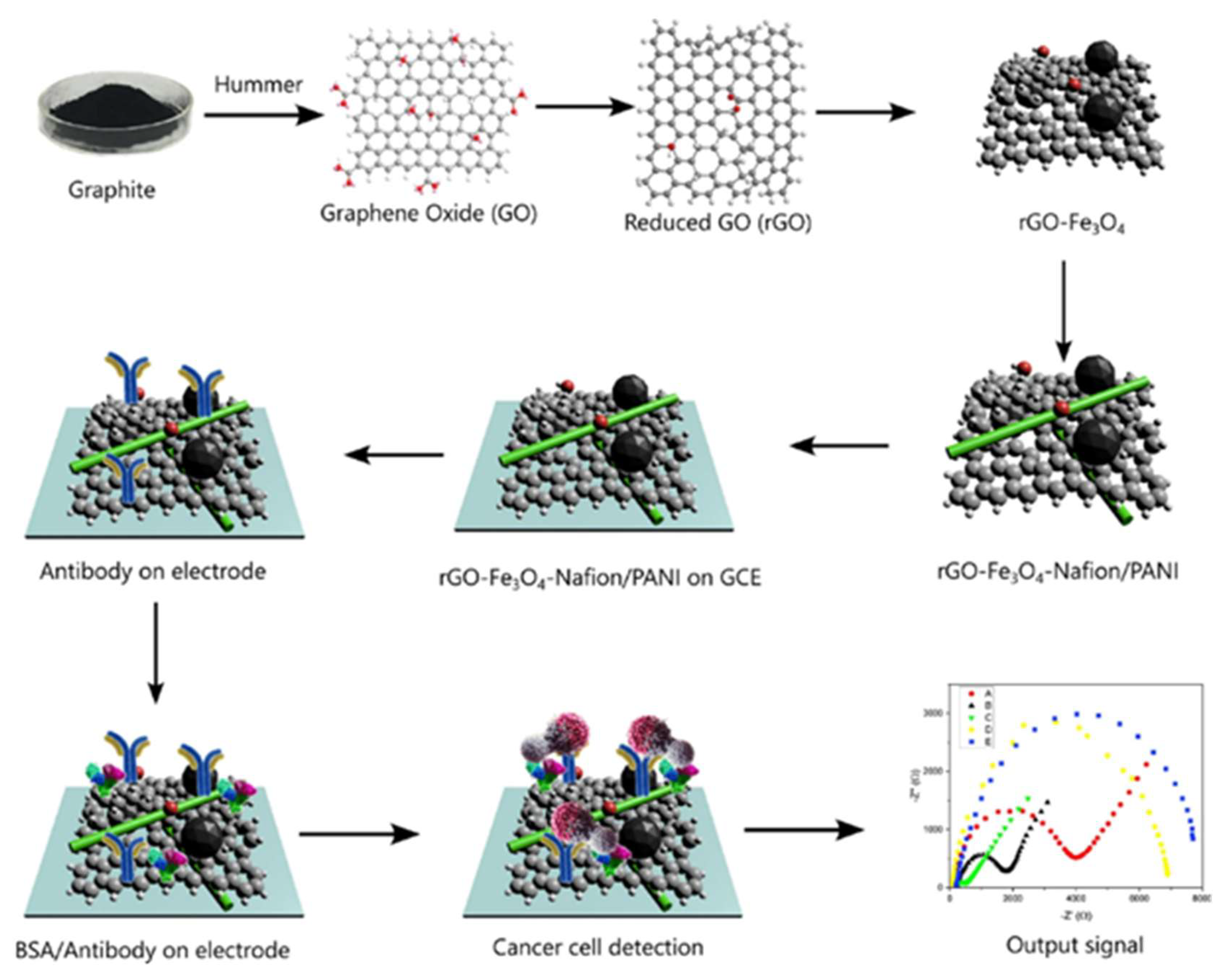

- Hosseine, M.; Naghib, S.M.; Khodadadi, A. Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensor Based on Green-Synthesized Reduced Graphene Oxide/Fe3O4/Nafion/Polyaniline for Ultrasensitive Detection of SKBR3 Cell Line of HER2 Breast Cancer Biomarker. Sci Rep 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zhao, L.; Yang, X.; Yang, L.; Fa, H.; Wang, Y.; Huo, D.; Hou, C.; Zhong, D.; Yang, M. MBene as Novel and Effective Electrochemical Material Used to Enhance Paper-Based Biosensor for Point-of-Care Testing CtDNA from Mice Serum. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çağlayan Arslan, Z.; Okan, M.; Külah, H. Pre-Enrichment-Free Detection of Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Specific CtDNA via PDMS and MEMS-Based Microfluidic Sensor. Microchimica Acta 2024, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.C.; Soh, J.O.; Choi, H.J.; Park, H.S.; Lee, S.M.; Fu, H.E.; Kim, M.S.; Ko, M.J.; Koo, T.M.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Ultrasensitive and Rapid Circulating Tumor DNA Liquid Biopsy Using Surface-Confined Gene Amplification on Dispersible Magnetic Nano-Electrodes. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 12781–12794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, R. Construction of a Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensing System Utilizing Fe3O4/α-Fe2O3@Au with Magnetic-Induced Self-Assembly for the Detection of EGFR Glycoprotein. Vacuum 2024, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, H.; Mu, W.; Que, L.; Gu, X.; Rong, S.; Ma, H.; Miao, M.; Qi, X.; Chang, D.; et al. Electrochemical-Fluorescent Bimodal Biosensor Based on Dual CRISPR-Cas12a Multiple Cascade Amplification for CtDNA Detection. Anal Chem 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Xu, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Tang, X. Highly Sensitive Electrochemical Immunosensor Based on SiO2 Nanospheres for Detection of EGFR as Colorectal Cancer Biomarker. Alexandria Engineering Journal 2024, 89, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Li, N.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Huo, D.; Hou, C. Cu-MOF/Aptamer/Magnetic Bead Sensor for Detection of Breast Cancer Biomarkers HER2 and ER. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2024, 7, 9768–9776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Ni, Y.; Yue, Y.; He, D.; Liu, R. Magnetically Induced Self-Assembly Electrochemical Biosensor with Ultra-Low Detection Limit and Extended Measuring Range for Sensitive Detection of HER2 Protein. Bioelectrochemistry 2024, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanagavalli, P.; Eissa, S. Exploring Various Carbon Nanomaterials-Based Electrodes Modified with Polymelamine for the Reagentless Electrochemical Immunosensing of Claudin18.2. Biosens Bioelectron 2024, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagavalli, P.; Eissa, S. Redox Probe-Free Electrochemical Immunosensor Utilizing Electropolymerized Melamine on Reduced Graphene Oxide for the Point-of-Care Diagnosis of Gastric Cancer. Talanta 2024, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, S.; Ren, H.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhao, F.; Zhu, J.; Chen, Z. Ultrasensitive and Multiplexed Gastric Cancer Biomarkers Detection with an Integrated Electrochemical Immunosensing Platform. Talanta 2025, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Guo, J.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, W.Q.; Jin, Y.S.; Fu, Y.Z.; Yuan, R. Efficient CdIn2S4/MgIn2S4 Heterojunction for Ultrasensitive Detection of Lung Cancer Marker Neuron-Specific Enolase. Talanta 2024, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Ai, Q.Y.; Wang, A.J.; Mei, L.P.; Song, P.; Liu, W.; Feng, J.J.; Cheang, T.Y. Pronounced Signal Enhancement with Gourd-Shaped Hollow PtCoNi Bunched Nanochains for Electrochemical Immunosensing of Alpha-Fetoprotein. Sens Actuators B Chem 2025, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.; Ahmadi, S.; Chan, E.; Fournier, L.; Spagnolo, S.; Thompson, M. Detection of Ovarian Cancer Biomarker Lysophosphatidic Acid Using a Label-Free Electrochemical Biosensor. Electrochem 2024, 5, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Ding, J.; Guo, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, B.; Yang, H.; Sun, Y.; Hang, L. Dual-Responsive Electrochemical Immunosensor for CYFRA21-1 Detection Based on Au/Co Co-Loaded 3D Ordered Macroporous Carbon Interconnected Framework. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2024, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPCE/PTBDES/AuNPs | Immunosensor | 5–100 pg mL-1 | 1.20 pg mL-1 | Serum | [21] |

| ONOH-3 | Immunosensor | 0.5–10 and 10–300 ng mL-1 | 0.805 μU mL-1 | Serum | [25] |

| rGO-TEPA/ZIF-67@ZIF-8/Au | Immunosensor | 0.001–1000 U mL-1 | 1.8 × 10-5 U mL-1 | Serum | [26] |

| Ti3C2Tx/NH2-CNT | Immunosensor | 1–500 U mL-1 | 1 μU mL-1 | Serum | [22] |

| 3DrGO/MWCNTs-Thi)UiO-66-NH2/ferrocenecarboxylic | Immunosensor | 0.01–80 U mL-1 | 0.089 U mL-1 | Serum | [27] |

| PAAm-co-PMBAm@MIP@3-MPA@Au-SPE | Immunosensor | 0.01–100 U mL-1 | 0.001 U mL-1 | Serum | [29] |

| ITO-Mn/ZnO-Au | Immunosensor | 0.002–3 ng mL-1 | 0.5 pg mL-1 | Serum | [23] |

| NiFe2O4NPs | Immunosensor | 8.5–70 U mL-1 | 8.5 U mL-1 | Serum | [24] |

| FluiDCE | Immunosensor | 2–50 ng mL-1 | 0.6 U mL-1 | Serum | [31] |

| Paper-based electrodes (f-SPE) |

Immunosensor | 2–16 U mL-1 |

0.56 U mL-1 |

Serum Sputum | [32] |

| CNTs | Immunosensor | 0–300 U mL-1 | 0.005 ng mL-1 | Serum | [33] |

| Ab/HQ/Cu-PDA/CuNSs/FP | Immunosensor | 5–280 U mL-1 | 1.3 mU mL-1 | Serum | [34] |

| NGO-PtCo | Aptasensor | 0.05–200 U mL-1 | 4.1 × 10-2 U mL-1 | Serum | [28] |

| Note: PTBDES/AuNPs: (PTB) (poly toluidine blue in deep eutectic solvent)/gold nanoparticles (AuNP); ONOH-3: Onion oil–based organic–inorganic hybrids; rGO-TEPA/ZIF-67@ZIF-8/Au: Zeolitic Imidazol Frameworks-67 doped with rGO-TEPA= reduced graphene oxide-tetraethylenepentamine anchored in AuPdRu trimetallic nanoparticles; Ti3C2Tx/NH2-CNT-SPCE: Ti3C2Tx-MXene/amino-functionalized carbon nanotube (NH2-CNT) modified screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE); ITO-Mn/ZnO-Au: Mn-doped ZnO nanorod anchored in ITO substrate; NiFe2O4-NPs: NiFe2O4 magnetic nanoparticles; 3D-rGO/MWCNTs-Thi)UiO-66-NH2/ferrocenecarboxylic: UiO-66-NH2/ferrocenecarboxylic acid (UiO-66-Fc) doped with reduced graphene oxide/multi-walled carbon nanotube carboxylic acid- thionine; NGO-PtCo: nitrogen-doped graphene oxide decorated platinum cobalt nanoparticles; PAAm-co-PMBAm@MIP@3-MPA@Au-SPE: electrode based on gold surface (Au-SPE/3-MPA) doped with a copolymer of acrylamide and N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (PAAm-co-PMBAm); CNTs: carbon-nanotubes; f-SPE: Screen-printed paper-based electrodes (f-SPE); FluiDCE: fluidic dual carbon electrode; Ab/HQ/Cu-PDA/CuNSs/FP: device based on cellulosic filter paper (FP) coated with Cu nanosponges (CuNSs) and then covered with Cu-doped polydopamine nanospheres (Cu-PDA) and grafted with hydroquinone (HQ). | |||||

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNRs-AuNPs | Aptasensor | 0.1 fM–100 pM | 5.10 aM/9.39 aM | Serum | [57] |

| PNA-DNA H3WJ | PNA | 0.5 fM–5 nM | 0.15 fM | Serum | [58] |

| PNA | PNA | 0.1 fM–0.1 nM | 12.4 aM | Serum | [68] |

| PNA-MXene (Ti3C2Tx) | PNA | 100 aM–10 nM | 40 aM | Serum | [70] |

| LIG+PNA | PNA | 100 aM–100 nM | 0.6 aM | Serum | [74] |

| PB-COFs nanospheres | DNA | 10 fM–100 nM | 2.5 fM | Serum | [75] |

| AZO nanostars | DNA | 1 pM–10 nM | 3.98 pM | Breast cells | [59] |

| PER-CRISPR | DNA | 10-13–10-7 M | 30.2 fM | Serum | [60] |

| GO + G | DNA | 10 fM–1 nM | 3.18 fM | Serum | [61] |

| AuNPs | DNA | 0.1–1000 nM | 1 nM | Serum | [62] |

| Au/MWCNT | DNA | 0.001–10 nM | 0.73 pM | Serum | [63] |

| AuNPs | DNA | 1-100 nM | 50 pM | Serum | [64] |

| Lentil lectin (LCA)-MB | DNA | 1 fM–10 pM | 26 aM | Serum | [65] |

| IONPs | DNA | 0.1 pM–1µM | 0.023 pM | Serum | [66] |

| AuNPs/MBs/COFs | DNA | 10 fM–5 nM | 1.2 fM | Serum | [67] |

| AuNPs | DNA | ~1–100 nM | 0.4 nM | Serum | [69] |

| PER-CRISPR | DNA | — | 0.43 fM/0.12 fM | Serum | [71] |

| AuNPs | DNA | 10 aM–100 pM | 5.24 aM | Plasma | [72] |

| GO | DNA | 0.1 pM –10 nM | 0.029 pM | Serum | [73] |

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOxS1 (DNAzyme) | Aptasensor | 3.63 × 104–7.26 × 108 particles mL-1 | 3.63 × 104 particles mL-1 | Plasma | [76] |

| MCH–AuNPs | Aptasensor | 88–8.8×107 particles μL-1 | 22 particles μL-1 | Serum | [81] |

| MB-DNA probes | DNA | 1×102–1×108 aM | 45 aM | Exosomal miRNA | [78] |

| PbS CQDs | Immunosensor | 102–108 particles mL-1 | 19 particles mL-1 | Serum | [77] |

| GO + AuNPs | Immunosensor | 500–1×107 exo μL-1 | 110 exo μL-1 | Serum | [79] |

| AuNPs | Immunosensor | 105–1012 exo mL-1 | 8.7×102 exo mL-1 | Urine | [80] |

| Nanomaterial | Biosensor type | Linear range | Detection limit | Sample | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe-MOF | Cytosensor | 10–105 (EC)/150-105 (CL) | 3 cells mL-1 (EC)/ 10 cells mL-1 (CL) | HepG2 cells | [17] |

| AuNPs | Aptasensor | 100-106 cells/mL | 21 cells mL-1 | MUC1+ cells | [82] |

| Ni@MWNT | Immunosensor | 102-107 cells/mL | 2 cells mL-1 | Mouse liver tissue | [83] |

| rGO + IONPs | Immunosensor | 102-106 cells/mL | 5 cells mL-1 | SKBR3 cells | [84] |

| AuNPs | DNA | 1 pM-50 pM | 178 fM/216 fM | Mouse serum | [85] |

| (Au-Pt–Ag)-PDMS | DNA | 2-200 fM | 24.1 fM | Carcinoma cells | [86] |

| Au@Fe3O4NPs | DNA | — | ~3 aM | Plasma | [87] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).