1. Introduction

Maritime transport remains the foundation of global trade, currently handling about 83% of all international commerce. As the world’s population grows and industrial activity expands, this figure continues to rise [

1]. Naturally, this increasing demand has put more pressure on shipowners and shipbuilders to deliver vessels faster, more efficiently, and at greater volumes. Although commercial shipping continues to lead global maritime activity, other sectors such as defense, luxury yacht construction, and maritime tourism have steadily gained ground. These growing fields are not only adding to industrial output but are also opening up new employment opportunities across the sector.

As these changes take shape, the shipbuilding industry has been adapting by blending emerging technologies with practical, cross-disciplinary engineering. One clear example of this shift is the growing use of lean production methods—originally introduced in the automotive industry—as a way to improve how shipyards operate [

2]. These approaches don’t rely on rigid, one-size-fits-all procedures. Instead, they make room for adaptability, encourage teams to work more closely together, and keep the focus on working smarter—cutting down on waste, avoiding delays, and staying responsive to real-world conditions. By using things like just-in-time delivery, planning rooted in actual field experience, and regular check-ins on quality, shipyards are finding it easier to keep up with rising expectations for speed, reliability, and overall performance [

3].

Digital twin technology is quickly becoming a core part of modern shipbuilding as the industry moves toward Industry 4.0. These systems give shipbuilders a clear, real-time view of what’s happening at every stage—from design to commissioning—which makes it easier to spot problems early, make informed decisions, and keep quality on track from start to finish [

2]. At the same time, using quantitative evaluation models makes it possible to measure build quality more precisely by linking individual subsystems to overall mission reliability [

3]. Recent findings suggest that maritime transport networks tend to follow patterns seen in small-world and rich-club systems—an insight that calls for more thoughtful planning, not just at the infrastructure level but also in how operations are organized day to day [

4].

In parallel, risk assessment models are being reworked to keep pace with the changing nature of maritime operations, making room for the kinds of uncertainties that come with new technologies and evolving global conditions [

5,

6,

7]. From accident modeling to AI-enhanced predictive systems, the field is moving toward more integrated, multi-scalar risk mitigation strategies that align with both operational resilience and environmental sustainability objectives [

1,

8,

9].

This study focuses on the detailed analysis of electrical outfitting processes in modern shipbuilding. It begins with an overview of the global significance of maritime transportation and provides a concise introduction to the shipbuilding industry and its core production procedures. This study looks at shipbuilding by breaking it down into two main parts. The first deals with getting the project off the ground—figuring out what needs to be built and what the client expects. The second part takes those plans and turns them into reality, covering everything from managing the project and designing the systems to ordering materials, checking quality, and carrying out the actual construction. As shipbuilding has evolved, electrical systems have taken on a much more central role. What used to be a smaller part of the process is now one of the most demanding and essential areas of the build. With the constant addition of new technologies on board, electrical outfitting has become deeply integrated into every stage of construction, requiring careful coordination and a high level of expertise. The chapters that follow walk through three key technical areas: how cableways are installed, how cables are pulled, and how electrical connections are made. Each section takes a close look at the methods currently in use, the typical issues that come up, and the strategies that work best to avoid mistakes and keep things moving efficiently. To ground the analysis in real-world experience, the study includes a detailed case study of a completed chemical tanker project. This example provides insight into how the process plays out in practice, including performance results and labor hour data for each phase. Overall, the goal of the study is to show why electrical outfitting plays such a crucial role in shipbuilding today—and to offer practical ideas for improving quality, managing costs, and keeping projects on schedule.

2. Electrical Outfitting in Modern Shipbuilding

Electrical outfitting is a key part of modern shipbuilding, shaping not only how smoothly a vessel is constructed but also how reliably it operates once it’s in service. It covers a wide range of systems—power distribution, automation, onboard communications, and various electromechanical components—all of which need to work together seamlessly. It becomes especially important during the segment outfitting stage, which makes up a large part of the overall workload and demands a high level of precision. Despite its importance, traditional manual methods often fall short—leading to delays, disorganized workspaces, and higher costs. As shipbuilding continues to move toward more advanced and higher-value vessels, adopting structured, tech-driven approaches to electrical outfitting is becoming key to staying competitive and working more efficiently on a global scale [

10,

11,

12,

13].

2.1. The Shipbuilding Process

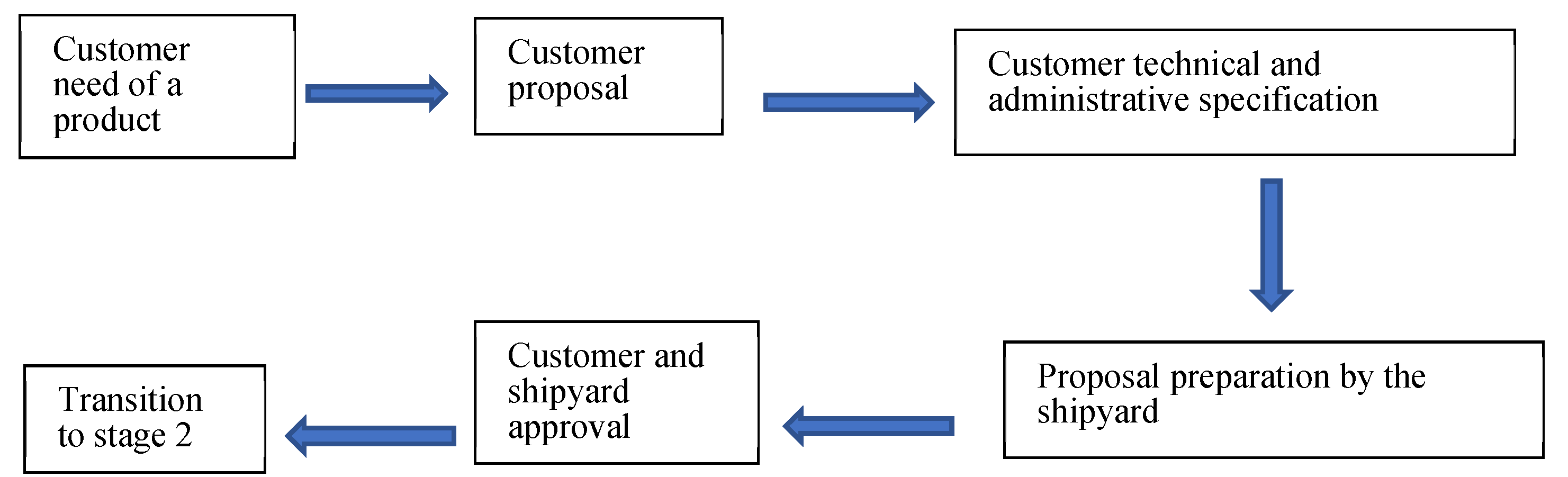

The shipbuilding process can be broadly divided into two main stages. The first stage given in

Figure 1 involves project determination based on customer requirements and the formulation of technical and contractual specifications, including a maker’s list and project timeline. Projects may be either pre-designed or custom-made, depending on client demands. Once both sides have agreed on the details and the legal groundwork is in place, the project moves into its next phase. This stage involves kicking off work, putting together a solid plan, handling the design and procurement, managing the supply chain, ensuring quality standards are met, and moving into full-scale production. Throughout, close coordination between teams helps keep everything on track and aligned with international requirements—making sure the project finishes on time and meets expectations.

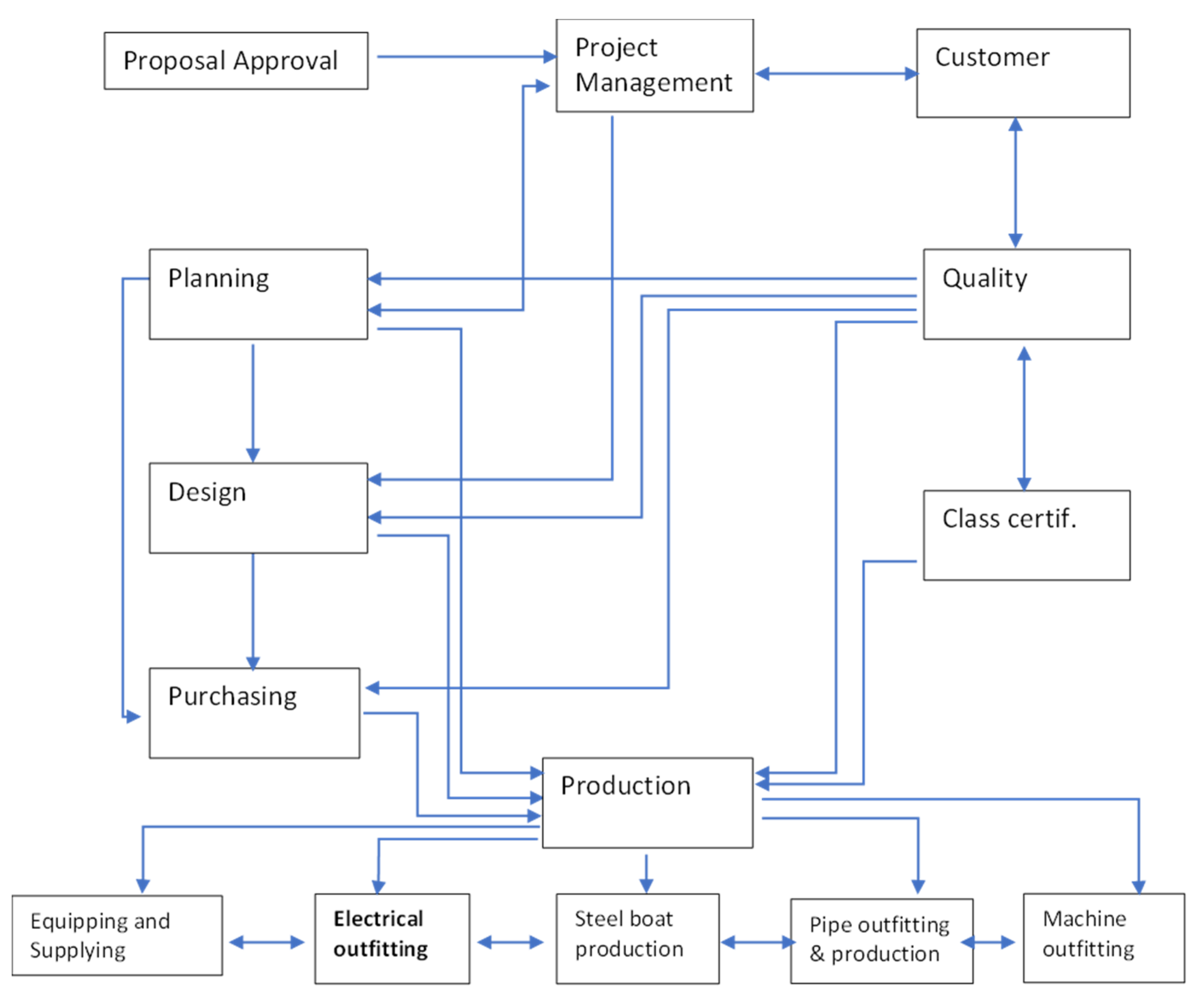

In the second stage of shipbuilding, the design process begins in line with the project’s approved technical specifications and international shipbuilding regulations. This phase depicted in

Figure 2 involves coordination between project management, design, procurement, and production departments, with key milestones and delivery dates established according to the contractual framework. Once the vessel’s layout and equipment specifications are finalized by the design team, they are forwarded to the purchasing and supply chain departments. These units produce the necessary materials and equipment in accordance with the production schedule to ensure efficient workflow.

Every step is carried out in a coordinated and well-structured way to lay the groundwork for construction. During this process, the quality control team is constantly involved, checking each stage to make sure everything meets the required standards. Alongside them, both the client and representatives from a certified classification society closely follow the progress to ensure the work stays in line with international regulations and quality expectations.

2.2. Electrical Systems in Ships

Shipbuilding technology has been evolving faster than ever, with recent years seeing a sharp rise in innovation. As new systems are built into modern vessels, the level of direct human involvement has decreased, making way for the emergence—and real-world testing—of fully autonomous ships. The share of electrical systems in the overall construction scope differs based on the type of vessel. For instance, electrical outfitting makes up roughly 30% of the total system components in passenger ships, about 35% in military vessels, 6% in dry cargo ships, and ranges from 5% to 20% in oil and chemical tankers, depending on the size of the ship. At first glance, the electrical side of shipbuilding might not seem like a major contributor in terms of labor. But when it comes to cost, it tells a different story. Because of the high price of specialized equipment, quality materials, and the need for experienced technicians, the electrical work often makes up a much larger share of the budget. In fact, in some projects, it can account for as much as 60% of the total construction cost. For instance, in a 10,000 DWT chemical tanker, electrical installation man-hours are generally lower than those required for piping systems—approximately 20,000 man-hours compared to 80,000 for piping. Nevertheless, due to the higher wage levels of electrical personnel, the cost difference between these two trades narrows significantly, often reaching comparable levels.

The installation of a ship’s electrical systems is not executed in a single operation. It occurs incrementally, in accordance with the pace of the construction process. Each step must align with the activities of other teams—structure, pipeline, machinery—to prevent interference. Effective teamwork facilitates smoother operations—errors are identified promptly, and the project remains on track. Electrical outfitting occurs towards the conclusion of the construction process, however it is one of the most critical phases. It animates the vessel, necessitating meticulous oversight, continual inspections, and unwavering commitment to quality throughout the entire process.

Just like in other areas of engineering, electrical systems on ships have to meet international rules and the specific standards set by classification societies. Extra care is taken with systems tied to emergency response, navigation, and environmental safety—since these are critical not only for the ship’s operation but also for meeting strict regulatory requirements [

14].

2.2.1. Cableways

Electrical installation on a vessel often commences with the establishment of foundational elements—installing support structures such as brackets, trays, and mounting frames for panels and switchboards. This responsibility generally lies with welders and metalworkers, whose selection of materials is contingent upon the installation’s location. Conditions can be especially bad on open parts of a ship, like decks on the outside, because they are always exposed to the weather and saltwater. To deal with this, builders usually utilize stronger materials, like galvanized or stainless steel, to place electrical supports. These decisions aren’t only about short-term strength; they’re also about long-term reliability, since contemporary ships are intended to last for up to twenty years [

15,

16]. With the adoption of block construction methods, where individual ship blocks weighing several hundred tons are pre-assembled before final integration on the slipway, there is a growing emphasis on performing cableway and equipment support installations during the block assembly phase.

Pre-outfitting during block construction comes with a lot of advantages—it saves time, reduces costs, and makes the whole process more efficient. When cable support systems are installed while the blocks are still being built, it’s much easier to access work areas, the job is less physically demanding, and there’s less need for things like temporary lighting, ventilation, or working in tight, enclosed spaces later on. Getting the supports in early also means cable pulling can start sooner, which helps keep electrical outfitting on schedule. But to make this work, the project needs to be planned carefully from the beginning, with materials and skilled workers available exactly when they’re needed. Still, some shipyards miss this opportunity and delay cableway installation until after the blocks are joined—losing valuable time and driving up costs in the process.

2.2.2. Cable Pull Process

Cables are essential for the operation of a ship, transmitting both electricity and signals that connect and regulate the vessel’s various systems. In contrast to terrestrial cables, marine cables are engineered to withstand the harsh conditions of the ocean; they possess the durability to endure continuous movement, saline environments, ultraviolet radiation, chemical exposure, and interference from adjacent apparatus. This durability is essential for ensuring the reliable operation of all onboard systems, regardless of the environment. It costs a lot to make something that strong. Marine cables are costly, and because so much depends on them working properly, they’re tested thoroughly at every stage—from production to installation. To keep things on track and avoid wasting materials, cable installation needs to follow a clear plan from the start. Engineers use 3D models and design studies to figure out where each cable should go and how much is needed. Ships use different types of cables—power, control, emergency, and communication—each with its own needs. Good planning also means making sure cables are safely routed, especially in areas where fire safety or waterproofing is critical.

Shipyards use three main ways to attach cables. While the first way is to cut wires straight from supply spools according to schematics, it often leads to unregulated waste and poor inventory management. The second technique, although it makes it a little easier to control the warehouse, still retains the problems of the first. The third method, which employs a pre-approved, sorted “from-to” list with fixed amounts and routing patterns, makes things more accurate, easier to track, and less wasteful. This plan makes it easy to keep an eye on things in real time, keep track of changes, and better coordinate with deadlines for buying products.

The third strategy is not very common, even if it seems to have some benefits. This is usually because design and production don’t work well together, people don’t want to change how they do things, or operations are entrenched in their ways. The best amount of cable loss per run is 2 meters (1 meter on each end), however if you don’t follow the right steps, this number can go up by two or three times. When this is done to hundreds or thousands of cable lines, it wastes a lot of materials and costs more than planned, which undermines the project’s efficiency and the shipyard’s bottom line.

The cable list shown in

Table 1 was put together using a method that emphasizes early preparation and clear, traceable steps. By planning routes in advance, it becomes easier to manage materials, reduce unnecessary waste, and keep teams aligned throughout the project. Each cable entry has the technical specifications, route details, and checkpoints essential for maintaining organization and preventing errors during installation. The list can be enhanced by incorporating the weight of each cable, rather than only monitoring the progress of the installation. When you add all up, it provides naval architects a useful number that they can use to figure out how stable a ship is and where its center of gravity is. These actions are very important for keeping a ship safe and stable at sea. Having this kind of information on hand can also be useful later on, whether it’s to make ships that are lighter and more efficient or to make better tools for managing weight distribution in future versions.

A solid cable list does more than guide the initial setup—it sticks around as a practical reference through the ship’s entire service. It helps crews stay on top of changes, like adding new systems during maintenance or tweaking existing ones during upgrades. Shipowners usually include extra cables from the start so they can make changes afterward. This not only saves time, but it also helps make sure there are no surprises later on. The list is more than just a technical document; it’s a way to keep things consistent and make sure the vessel stays reliable long after it has been built.

2.2.3. Cable Connection Process

It may seem like a normal aspect of the job to connect cables aboard a ship, but it’s actually one of the most important things to do. It has to be done in steps, starting with shore power and going through things like generators and emergency gear. Things can go wrong, sometimes in dangerous or costly ways, if tests aren’t done or modifications in the field aren’t shared with the design team. One of the worst things you can do is turn on the power before all the cords are plugged in. That’s why it’s so vital to keep note of what you’ve done, double-check each connection, and follow safety rules. Safety should always come first, no matter how tight the schedule gets. The structured cable connection list, as illustrated in

Table 2, provides a systematic method for recording and managing electrical terminations across the vessel. A clear, well-organized cable connection list does more than just track tasks—it helps hold the whole project together. By noting down specs, terminal points, test results, and any changes made along the way, it keeps everyone on the same page and makes errors less likely

The cable connection list is more than simply a list of things to accomplish; it’s a helpful tool that keeps the project on track. By keeping an eye on progress in real time, it helps teams stick to their plans for installing the system and getting it up and running. It also helps keep things safe during power-up, plan the job of the staff, and make maintenance easier in the future. The list changes as the build goes on, so it is a valuable source of information that helps with both daily work and long-term ship operations.

3. Materials and Methods

In this study, the electrical outfitting of a 10,000 DWT IMO11 chemical tanker was carried out using a systematic and integrated strategy that stressed early planning, effective execution, and ongoing management. Before the giant blocks were joined together, the outfitting procedure began with the installation of cableways. This happened throughout the block construction phase. This plan made it possible to finish cableways at places that were easy to go to and see. This made things easier later on and let them start working on the electrical work sooner. The project papers say that hot work on the cableway took up 8,430 hours of worker time and made up 35% of the total electrical burden.

The design team created a “from-to” cable list that was used to schedule the cable pulling activities ahead of time. This list told you where each cable came from and where it was going, how many there were, and how they needed to be routed.

Table 3 shows a sample cable pull list. Before they were put in, cables like W11, W12, and W13 were given specific courses, quantities, and terminal locations. This process saved a lot of materials from being lost. They pulled 110 km of cable, yet only 87 km was wasted. Employees did 9,655 hours of work, and cable pulling made about 40% of the electrical work.

A structured cold wire test list was utilized to make sure that each termination met the requirements before it was powered on. As you can see in

Table 4, the cable connection list, each cable was tested for insulation resistance (for example, W11 was tested at 1.5 GΩ) and examined to make sure the terminals were mapped correctly. Changes, like changing the terminal designation for cable W21, were written down to keep the design the same. This phase took up 25% of the electrical work, which was 6,110 hours of work by employees.

Maintaining a structured and continuously updated record of cable types, codes, test results, and connection approvals proved essential for day-to-day control. It allowed project teams to track progress, coordinate with field engineers, and assess system readiness in line with delivery schedules. The utilization of workers and the effectiveness of their job performance were more easily discernible through the recording and analysis of 24,195 man-hours. The integration of all cable-related duties into a single system facilitated communication between design and field crews and reduced the number of errors. Making these documents digital made the supply chain more open and easier to work together. This method made it possible to safely, on time, and effectively complete all electrical work, from routing cables to making final connections.

4. Results

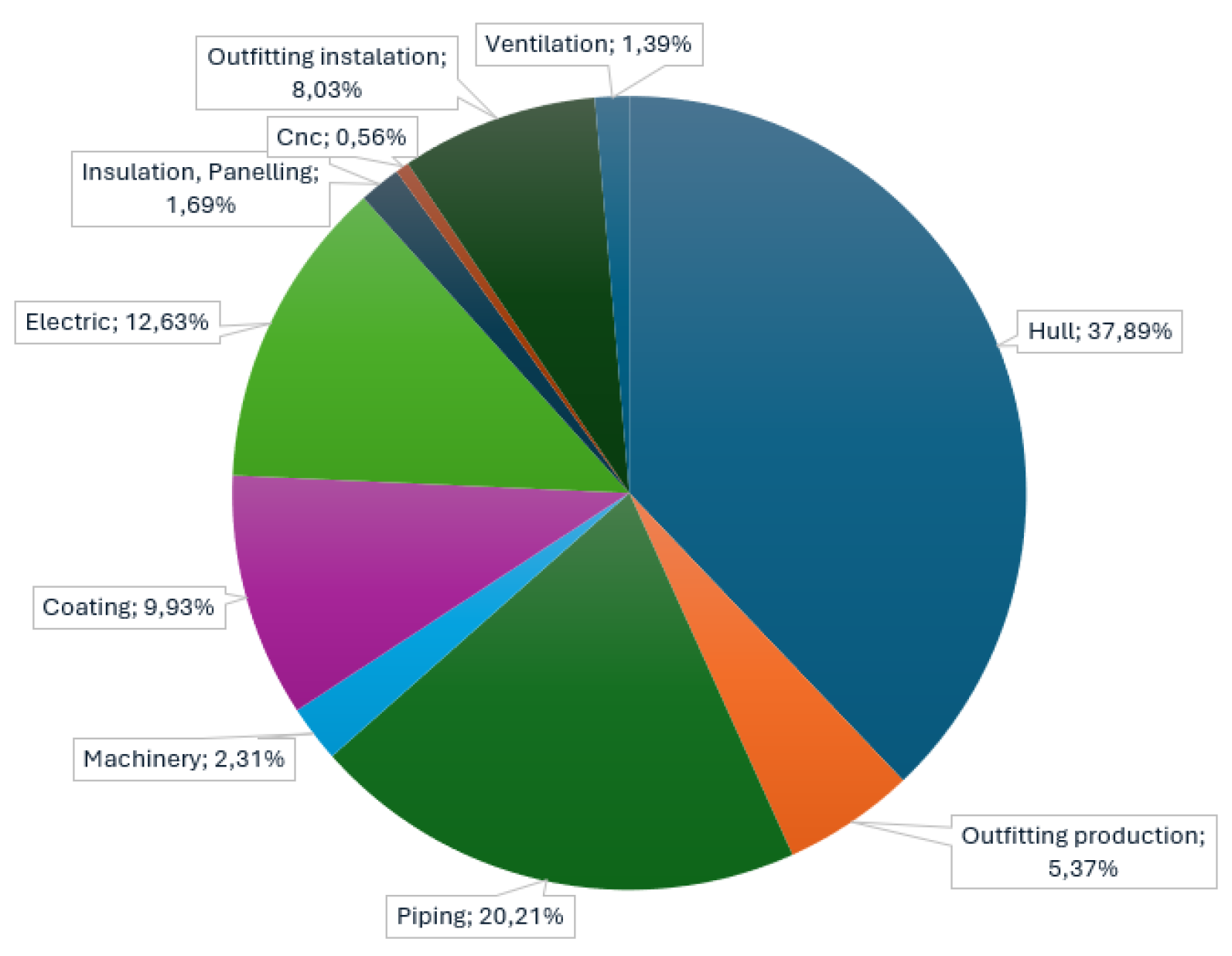

Figure 3 shows how the manhours were spread out across the several departments while the 10,000 DWT ship was being built. It is intriguing that electrical installation accounted for only 9% of the total manhours. Initially, this may apper to be a little percentage. This fraction remains significant, as electrical systems are crucial for the ship’s overall performance post-delivery. Even though the job is done in a short amount of time, it shows how precise and skilled the Electrical Department is, which is necessary for the ship to run.

Figure 4 depicts a part of the cableways that were built during the block stage, right before the block was put together with the bigger mega block. This is a very important step in building a ship. The early electrical installations must line up perfectly with the systems in the blocks around them. Completing the cableways at this point not only speeds up the installation process, but it also makes sure that structural pieces link more smoothly and reliably, which lowers the likelihood of delays or problems during assembly and outfitting.

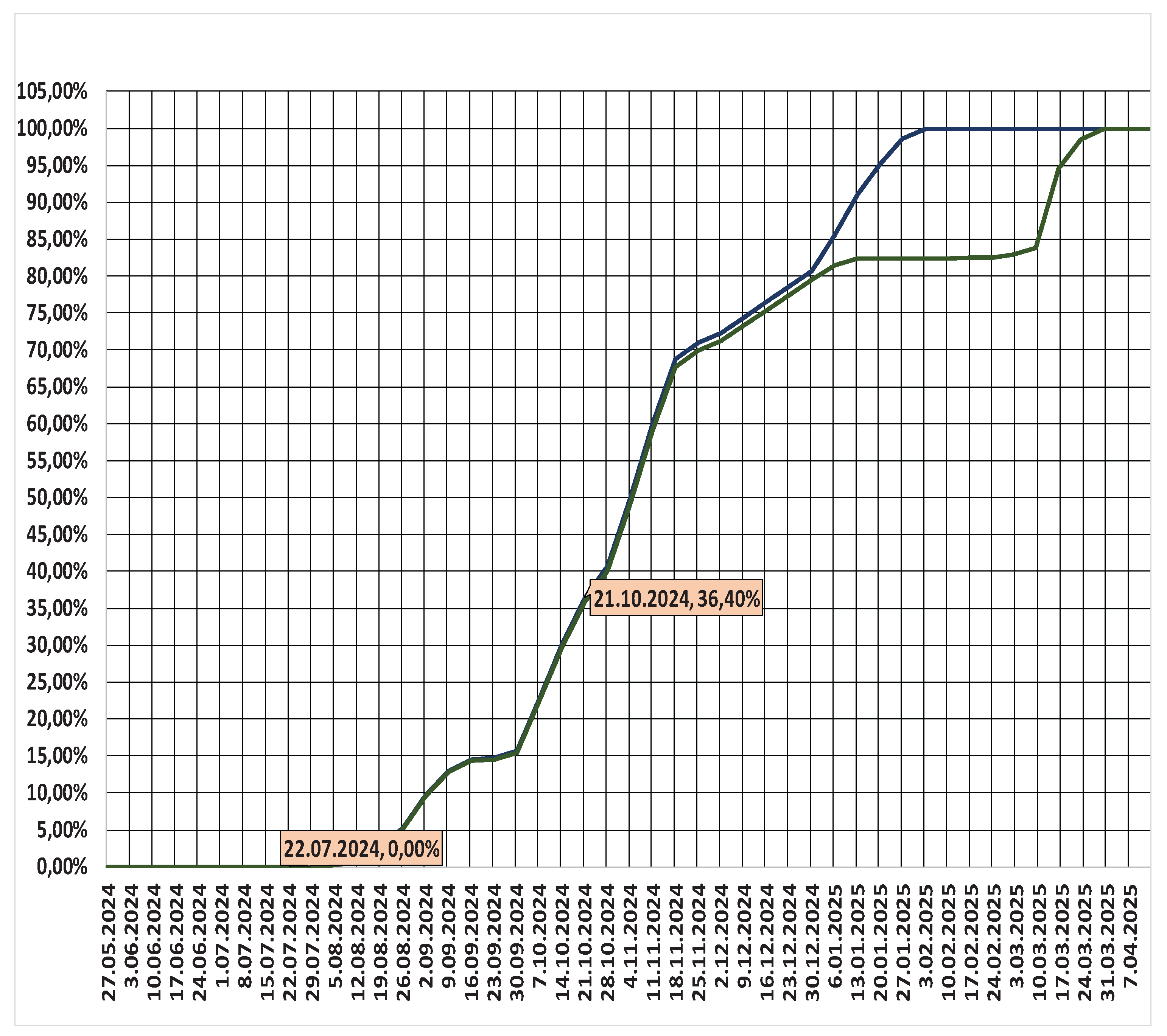

The chart in

Figure 5 illustrates the advancement of electrical work over an eight-month duration, with the project adhering to its timeline and achieving completion as intended. Approximately 70% of the work occurred between August 2024 and January 2025, suggesting that the initial phase predominantly concentrated on the installation of electrical equipment, executing hot work on cableways, and cable pulling. Most of the work in the last stages was testing the systems and finishing the cable connections. Nevertheless it’s also important to point out the work that was done before the active phase, which took place from May to August 2024. At this point, the design team put together the necessary assembly drawings, made detailed lists for installing and connecting cables, and finished the planning documents. These early steps were very important to making sure that all of the work on site went smoothly and was in sync after the project moved to the field.

5. Conclusions

The study makes it clear that electrical outfitting, though often viewed as a smaller part of the shipbuilding process, carries much more weight than its limited labor share might suggest. Its function is crucial in ensuring the vessel operates securely, effectively, and without significant problems over time. Nevertheless it’s not just about doing the work out in the field—it also depends on how well the design, planning, and supply teams communicate and coordinate at the right time.

One of the most important lessons from this work is the impact of early preparation. When cableway plans are clearly laid out, schedules are set, and everything is organized from the beginning, the rest of the process tends to go much more smoothly. Aligning electrical work with the broader construction schedule helps avoid delays, reduce unnecessary costs, and makes final testing and delivery more straightforward. Since critical systems like automation, navigation, and control all rely on electrical infrastructure, how well this part is handled directly affects the ship’s long-term performance—and its value in the market. In short, shipyards that want to deliver high-quality vessels on time and stay competitive in a demanding industry should give electrical outfitting the planning, attention, and investment it deserves from day one.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be shared upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank T. Oda for his valuable contributions, particularly for his support in data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huang, X.; Wen, Y.; Zhang F. A review on risk assessment methods for maritime transport. Ocean Eng. 2023, Volume 279, 114577.

- Iwankowicz, R.; Rutkowski, R. Digital twin of shipbuilding process in shipyard 4.0. Sustainability 2023, Volume 15, 9733.

- Guo, Y; Wang H.; Liang X. A quantitative evaluation method for the effect of construction process on shipbuilding quality. Ocean Eng. 2018, Volume 169, 484-491.

- Hu Y; Zhu D. Empirical analysis of the worldwide maritime transportation network. Physica A 2009, Volume 388, 2061-2071.

- Mousavi M.; Ghazi I.; Omaraee B. Risk assesment in the maritime industry. Eng. Tech. Appl. Sci. Res. 2017, Volume 7(1), 1377 – 1381.

- Chang C.H.; Kontovas C.; Yu Q. Risk assesment of the operations of maritime autonomous surface ships. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Safety 2017, Volume 207, 107324.

- Wang J. Sii H.S.; Yang J.B. 2024. Use of advances in technology for maritime risk assessment. Risk Analysis 2024, Volume 24(4), 1041-1063.

- Alanhdi A.; Toka L. A survey on integrating edge computing with AI and blockchain in maritime domain, aerial systems, IoT, andiIndustry 4.0. IEEE Access 2024, Volume 12, 28684-28709.

- Kaklis D.; Varlamis I; Giannakopoulos G. 2023. Enabling digital twins in the maritime sector through the lens of AI and industry 4.0. Int. J. Info. Manag. Data Insights 2023, Volume 3(2), 100178.

- Garcia C.; Rabadi G. Approximation Algorithms for Spatial Scheduling Heuristics; Publisher: Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016, pp 1-16.

- Zhang Y.; Ci H. Research on Irregular Block Spatial Scheduling Algorithm in Shipbuilding. International Conference on Intelligent and Interactive Systems and Applications, 2018, pp 1130-36.

- Im I.; Shin D.; Jeong J. Components of smart autonomous ship architecture based on intelligent information technology. Procedia Comp. Sci. 2018, Volume 134, 91-98.

- Koikas G.; Papoutsidakis M.; Nikitakos N. New technology trends in the design of autonomous ships. Int. J. Comput. App. 2019, Volume 178(25), 4-7.

- Kim M.; Joung T.H.; Jeong B. Autonomous shipping and its impact on regulations, technologies, and industries. J. Int. Maritime Safety, Envir. Affairs, and Shipping 2020, Volume 4(2), 17-25.

- Rose C.D.; Coenen J.M.G. Automatic generation of a section building planning for constructing complex ships in European shipyards. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2016, Volume 54(22), 6848-6859.

- Rubesa R.; Fafandjel N. Procedure for estimating the effectiveness of ship modular outfitting. Eng. Review 2011, Volume 31(1), 55-62.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).