1. Introduction

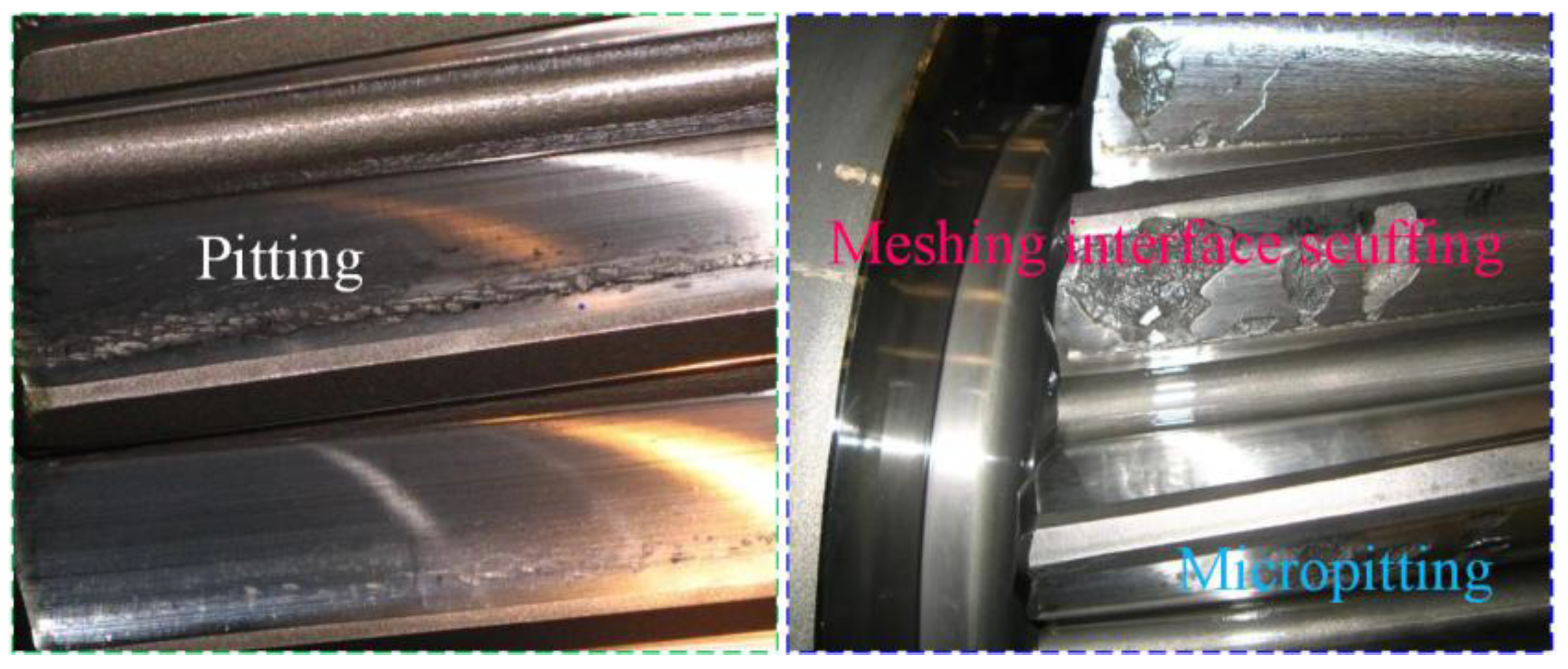

Meshing interface engineering has emerged as a distinct interdisciplinary domain dedicated to resolving multiscale contact challenges inherent in gear surface topographies. This necessitates the development of scale-bridging computational frameworks to decode the intricate interplay between interfacial mechanics and thermal transfer phenomena. This research field carries significant academic importance, as interfacial contact behavior profoundly impacts the global performance of marine power rear transmission components under coupled thermo-mechanical loading conditions. The meshing interface, specifically defined as the contact boundary region formed under THE-mode loading conditions, exhibits fundamentally distinct deformation mechanisms compared to bulk materials. This divergence originates from the marked differences between the interfacial microstructure and bulk material properties, along with their abrupt physical property transitions. Therefore, to gain an in-depth understanding of the thermo-mechanical contact behavior at meshing interfaces, it is essential to establish a multiscale research framework specifically tailored for non-smooth line-contact interface topographies.

The pioneering work in the study of meshing interface mechanics can be traced back to the Hertzian elastic contact theory [

1,

2]. This groundbreaking progress laid the foundation for the discipline of contact mechanics, which mainly investigates the deformation behavior of rigid contacts with Euclidean macroscopic configurations. Since Hertz’s pioneering research, the elastoplastic contact deformation problem of rotationally symmetric bodies has been of continuous interest to the academic community. This is primarily due to the significant impact of meshing interface mechanics on the durability of gear transmission systems containing contact elements. The early researchers of quasi-static contact studied the deformation problem of a rigid sphere indented into an ideal elastoplastic half-space. In another early study, the process of a rigid cylinder indenting into a linearly hardening elastic half-space is analyzed, and it is found that the contact pressure distribution exhibited a flattening characteristic, with the material having the weakest strain hardening capability showing the most significant deviation from the Hertzian pressure distribution [

3,

4,

5]. In subsequent research, the quasi-static spherical indentation problem in a fully plastic deformation zone of a hardening material is explored, employing a power-law hardening nonlinear elastic model to simulate the deformation behavior of a rigid sphere indenting into a half-space in the fully plastic region.

With the continuous development of numerical computation methods such as the finite element method, finite difference method, finite volume method, and boundary element method, as well as significant improvements in computational efficiency, research on the mechanics of meshing interfaces has achieved groundbreaking progress in theoretical modeling and numerical simulation. In the field of contact mechanics modeling, researchers have established a finite element model for the rolling contact between a cylindrical body and an elastoplastic half-space, innovatively employing moving elliptical or modified elliptical pressure distributions to simulate cylindrical loading [

6,

7,

8]. For spherical contact problems, the three-dimensional frictionless contact behavior between a rigid sphere and a linear kinematic hardening half-space has been systematically investigated by introducing a moving Hertzian pressure distribution [

9,

10,

11]. In the realm of elastoplastic contact theory, scholars have conducted in-depth analyses of the mechanical responses of isotropic strain-hardening and non-hardening elastoplastic half-spaces under cyclic loading by spherical indenters, obtaining for the first time an exact interfacial mechanical solution for the first loading cycle in the fully plastic contact deformation stage. Based on extensive numerical calculations, the research team has mapped out characteristic diagrams of average contact pressure versus deformation mechanisms, covering elastic, perfectly plastic, and elastic-hardening materials [

12,

13,

14]. Notably, studies on the contact behavior between a rigid sphere and a perfectly elastoplastic half-space reveal that as the number of loading cycles increases, the contact pressure distribution gradually deviates from the classical Hertzian solution [

15,

16,

17]. Regarding the influence of material parameters, numerous researchers have systematically examined the multiple loading-unloading processes of elastoplastic spherical contact under various material parameter conditions and proposed a universal solution for average contact pressure based on normalized indentation strain parameters for perfectly plastic materials. The latest dynamic contact research has extended this theoretical framework to spherical indentation problems involving elastoplastic half-spaces with or without strain hardening and strain-rate-dependent constitutive relations [

18,

19,

20]. The key finding is that a normalized strain parameter, defined as the product of yield strain and indentation strain, can uniformly characterize universal solutions for dimensionless global field parameters (e.g., dimensionless average contact pressure) at meshing interfaces [

21,

22,

23]. This theoretical breakthrough provides a foundational basis for predicting the mechanical contact behavior of meshing interfaces under complex working conditions.

Although the aforementioned studies and numerous relevant findings in recent years have provided a vital theoretical foundation for the macroscopic contact mechanics of meshing interfaces under various loading conditions, it must be pointed out that real gear surfaces in mesh are not ideally smooth, but are composed of complex geometric features spanning multiple scales. Therefore, to accurately characterize the local deformation behavior of surface asperities (roughness peaks) during actual contact processes, a multi-scale analysis framework must be established. Against this backdrop, the microcontact theory has emerged. Its core objective is to reveal the deformation evolution mechanism of the contact region of asperities. In the field of rough surface contact theory research, a milestone is the earliest proposed probabilistic contact model. The innovation of this model lies in its first recognition that nominally smooth surfaces are actually composed of asperities distributed over multiple scales, and its pioneering use of the normal distribution to describe the height distribution characteristics of asperities. However, this model has obvious theoretical limitations: it assumes that all asperities have the same radius of curvature and a fixed lateral spacing, which is significantly different from the actual topography of rough surfaces. It is this idealized assumption that leads to the inherent theoretical flaws in all contact mechanics analyses based on this model.

The morphological characteristics of real gear meshing surfaces are traditionally characterized by statistical parameters of surface height distribution, including key parameters such as root mean square roughness, micro-asperity slope, and curvature. However, due to the significant non-stationary and random characteristics of the actual meshing surface morphology, these statistical parameters will fluctuate significantly with changes in the measurement sampling area size and instrument resolution, making them unsuitable as deterministic parameters. Therefore, to achieve precise characterization of gear meshing surface morphology, it is necessary to establish an analysis method based on scale-invariant parameters that are independent of measurement scale and instrument resolution.

The representation methods of scale invariance of geometric similarity features under different magnifications (i.e., self-affine characteristics) have gradually attracted the attention of the academic community. This has in turn promoted the application of fractal geometry in the field of contact mechanics. Fractal geometry provides an effective means for describing, measuring, and even predicting these natural phenomena, studying the response mechanisms of materials to external stimuli, and characterizing the real meshing surface topography. Experimental evidence from high-resolution microscopes has confirmed that the vast majority of actual surfaces exhibit fractal characteristics. The fact that the power spectrum of most contact surfaces follows a power-law characteristic over a wide range of scales has led to the introduction of fractal geometry into contact mechanics research, giving birth to the emerging sub-discipline of “fractal surface contact mechanics”-a field that focuses on studying the multi-scale deformation behavior induced by meshing interfaces with fractal characteristics over a wide range of scales.

The analysis demonstrates that the multi-scale nature of meshing interfaces introduces complexity to contact-related physical phenomena (including deformation and thermal conduction), which substantially complicates the performance assessment of thermo-mechanical systems. The present work proposes to: (1) establish a multi-scale theoretical contact model for meshing interfaces subject to mechanical-thermal coupling effects; and (2) develop correlations between dimensionless parameters characterizing the contact behavior of fractal-based multi-scale meshing interfaces.

2. Multiscale Characterization of Real Meshing Interface Morphology

The core properties of the meshing interface with fractal roughness characteristics are manifested as continuity, non-differentiability, and self-affinity. These scale-invariant mathematical properties are characterized by the Weierstrass-Mandelbrot (W-M) function. In its two-dimensional form, the function maintains dimensional consistency, and its expression is provided. The right-hand side of Equation (1) represents a superposition of cosine spectra with geometric progression distribution. This mathematical structure reflects the self-similarity characteristics of multi-scale features in fractal profiles, where the frequencies exhibit geometric progression growth [

24,

25,

26].

where

represents the two-dimensional projected length of the meshing interface profile,

characterizes the fractal dimension-dependent roughness,

is the fractal dimension with the interval constraint (

),

serves as the characteristic scaling parameter for asperity distribution at meshing interfaces (

), which determines the self-affine properties by governing the spectral component density in contact profiles, and

is the frequency index whose value determines the weighting contribution of multi-scale features in meshing interface profiles. The frequency index

ranges between zero and

, where

denotes the rounding of the bracketed value to the largest integer, and

represents the minimum wavelength in the meshing interface profile. To ensure the applicability of continuum medium description,

is typically set at 5 to 6 times the material’s lattice spacing. The selection of parameter

must satisfy both phase randomization and high spectral density conditions. Research indicates that

represents an optimal balance between interface flatness and contact frequency distribution density. This scaling parameter

plays another critical role in fractal characterization: when the lateral dimension

is magnified by a factor of

, the height

will be scaled by

, expressed as

. This self-affine relationship constitutes a fundamental characteristic of self-affine fractals, whose physical essence stems from scale-invariant fundamental physical laws governing specific geometric domains.

To model higher-dimensional random processes, the Weierstrass-Mandelbrot (W-M) function can be generalized using multiple variables [

27]. This extension retains the original function’s essential properties—homogeneity, scaling behavior, and self-affinity—as defined in Equation (1). A bivariate formulation enables the simulation of a 3D fractal meshing interface, accurately representing its undulating topography in all directions. By taking the real part of the function, we obtain a height profile that exhibits stochastic variations across any planar orientation.

In the polar coordinate systemdescribing the contact points of a meshing interface at height , the transformation relationship with Cartesian coordinates is expressed as: , . where,andmaintain the same physical meaning and dimensional units as in Equation (1). The termdenotes a uniformly distributed random phase within the interval [0, 2π], generated by a random number generator. Its role is to ensure that the frequency components of the meshing interface profile do not spatially overlap. The parameterrepresents the wavenumber associated with the characteristic sample size, defined as . The angledescribes the ridge offset in the azimuthal direction (under uniform angular offset conditions, ). is a morphological construction parameter indicating the number of superimposed ridges, and its appropriate value can be determined based on the power spectral characteristics of the meshing interface morphology. For a two-dimensional interface with cylindrical undulations, , whereas for a three-dimensional fractal isotropic interface exhibiting axisymmetric power spectral features, the condition must be satisfied.

The height functionof a three-dimensional isotropic surface () is obtained by introducing the roughness parametersatisfying the relationinto Equation (2), and substituting the relational expressions of , , , as well as the value range of into Equation (2).

Classical geometry and fractal geometry differ fundamentally in their conceptualization of dimension. Classical geometry employs an integer-based dimensional framework, where a point is 0-dimensional, a line is 1-dimensional, a plane is 2-dimensional, and a solid is 3-dimensional. In contrast, fractal geometry introduces the innovative concept of fractional dimensions [

28,

29,

30]. Consider a straight line segment: while its classical dimension is unequivocally 1, in fractal geometry, a surface composed of intricately interconnected line segments may exhibit a non-integer dimension between 1 and 2 (for a two-dimensional surface) or between 2 and 3 (for a three-dimensional structure). This fractional dimension quantifies the spatial filling efficiency of the surface’s complex structure [

31,

32,

33]. If a surface that macroscopically resembles a tall mountain but is microscopically composed of countless tiny valleys will have a fractal dimension approaching 2. Conversely, a surface that appears flat at macroscopic scales but exhibits extreme microscopic complexity—such as being covered with nanoscale roughness peaks and valleys—will have a fractal dimension closer to 3. Thus, fractal dimension serves as a quantitative measure of morphological complexity across multiple scales, bridging macroscopic observations with microscopic intricacies. The physical significance of fractal interface roughness can be elucidated as follows: Equations (1, 3) demonstrate that R modulates the amplitude of the frequency components constituting the meshing interface profile. These equations also indicate that fractal interface roughness is a height-scaling parameter independent of frequency. The two-dimensional and three-dimensional functions provided by Equations (1, 3) can be used to generate random rough interface profiles, with the only unknown parameters being the experimentally determinable scale-independent parameters

and

. Fractal geometry possesses an inherent capability to characterize meshing interfaces across multiple scales (even those differing from the measurement scale), and its description is not constrained by the resolution of imaging instruments or the measurement length scale [

34]. A fractal interface can be characterized by three uniquely defined parameters:

,

, and

.

The length scale range over which an interface exhibits fractal characteristics depends on its morphological structure, with different machining processes contributing to the final contact morphology in distinct ways [

35,

36]. Taking polishing as an example: at scales less than or equal to the average abrasive particle size, the process behaves as a stochastic process; however, at larger scales (such as wafer planarization), its effects can be described as deterministic. While fractal descriptions are widely adopted for engineering surfaces at micro/nano scales, their macro/mesoscopic morphology still adheres to Euclidean geometry. If the contact interface morphology itself is formed by stochastic processes (thin-film devices fabricated via photolithography), fractal descriptions remain valid even at macroscopic scales, requiring the determination of distinct fractal parameters for different scale ranges to ensure the applicability of the aforementioned fractal surface theory. This implies that a single set of fractal parameters cannot be applied across the entire scale range where fractal behavior is observed. Such interfaces are termed as exhibiting multifractal characteristics.

3. Multiscale Analysis of Meshing Interface Micro-Asperity Contact Mechanics Characteristics

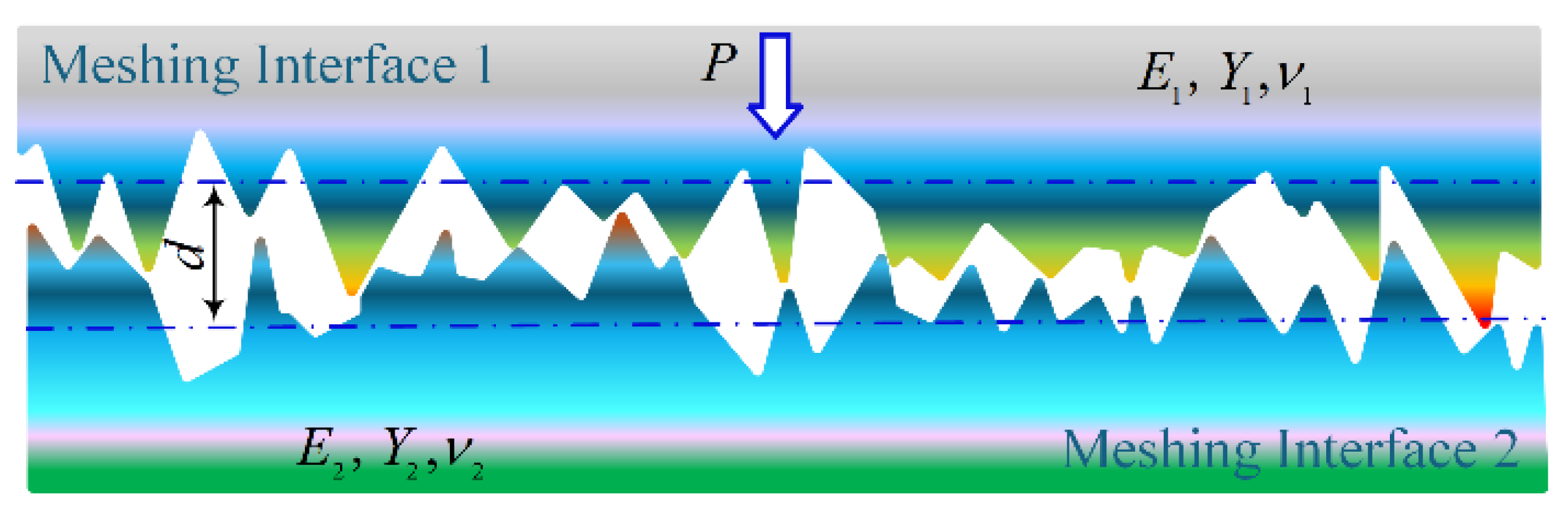

The mechanical properties of the meshing interface are a comprehensive reflection of the interactions between the deformations of multiple micro-asperities, which are triggered by the multi-scale characteristics of the contact surface roughness (as shown in

Figure 1). In the study of meshing interface mechanics, it is essential to integrate the contact deformation at the micro-asperity scale with multi-scale surface characterization. As mentioned earlier, the contact interface of two fractal surfaces can be modeled using equations (1, 2, and 3). This model can employ fractal parameters that dominate the power surface spectrum within the target frequency (wavelength) range, or it can use a multi-fractal description method. Based on this, the problem can be simplified under the action of the global surface interference amount

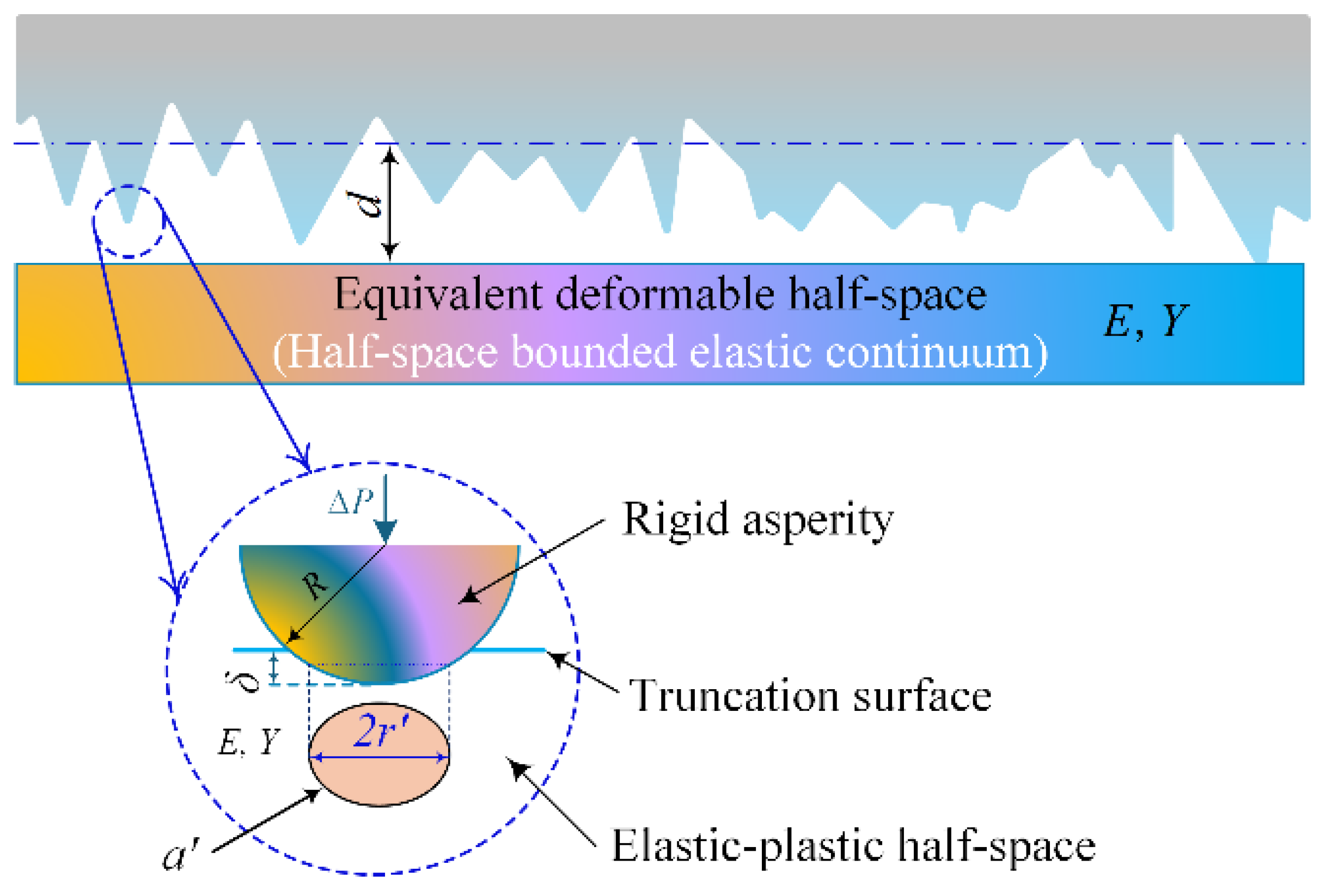

, when a deformable fractal surface comes into contact with a rigid plane, multi-scale micro-asperity contact is formed, which exhibits a distinct scale effect (as shown in

Figure 2).

In

Figure 2, each truncated micro-asperity is modeled as a sphere, with its truncation position determined by the local surface interference distance

, thereby forming a circular truncated contact area with a radius of

. Therefore, the key to the analysis of interface contact mechanics is to accurately grasp the distribution patterns of micro-asperity contact under a given global surface interference amount, as well as the deformation behavior characteristics at the micro-asperity scale.

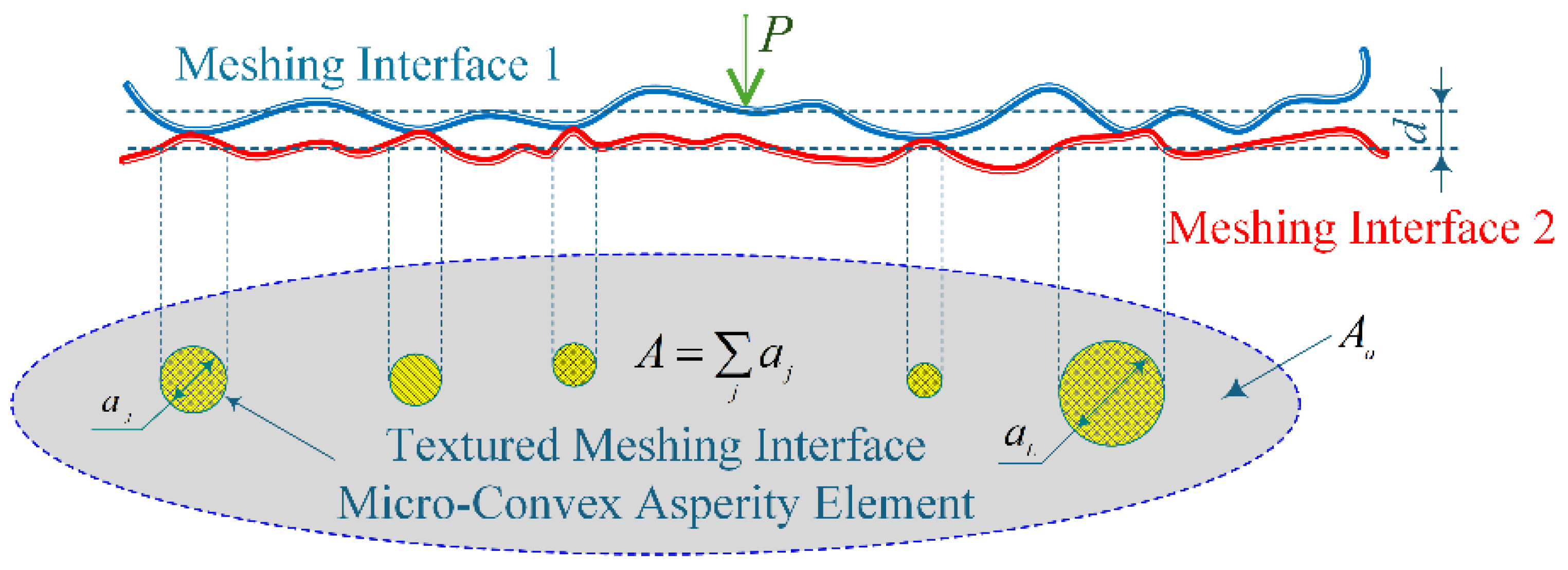

For relatively small interferences of the meshing interface, the textured meshing interface only involves several discrete microcontact points of varying sizes. As the meshing interface interference increases, more microcontact points will form, and some of the previously formed microcontact points will grow larger by merging with adjacent microcontact points.

Figure 3 shows a similar model, that is, the microcontact points formed when two rough surfaces are in contact under the normal load

. These microcontact points are approximately circular spots. Therefore, the actual contact area

(the sum of the areas of all microcontact points) is much smaller than the apparent contact area

. The microcontact model of the textured meshing interface is simplified as shown in

Figure 3. The truncated area of the resulting microcontacts can be described by a power-law relationship. The model describes the non-smooth contact behavior between two meshing interfaces under load, with its distinctive feature being that actual meshing only occurs at discretely distributed asperity contact points, where these micro-contact points exhibit multi-scale distribution characteristics.

where

is the number of micro-asperities within the meshing domain whose contact area is greater than

, and

represents the maximum micro-contact area within the meshing domain. According to Equation (4), the distribution function of micro-asperity contact areas within the meshing domain is written as

where

is determined from the truncated contact area

of the meshing interface profile, and the relationship is expressed as

where

represents the minimum microcontact area within the meshing domain, which indicates the truncated microcontact area below which the continuous medium mechanics cannot be applied to describe. Due to the existence of

, Equation (6) is expressed in the following simplified form.

The total micro-asperity contact areaof the textured meshing interface is determined by the fractal surface height distribution (as shown in Equation (3)), which is the sum of the areas of all pixels greater than the truncated interface height. Correspondingly, and is obtained through Equations (6, 7) and Equation (5), respectively. The spatial distribution of the roughness asperities of the textured meshing interface with a given contact profile has been completely determined. However, sinceis dependent on the contact interference amount(or contact load) of the meshing domain textured interface through, the micro-contact behavior may show significant inconsistency. After the non-smooth interface is truncated by a rigid plane to a certain meshing domain interference amount and the contact area distribution of the textured interface micro-roughness asperities is established (as shown in Equation (5)), it is necessary to further investigate the deformation modes of each micro-contact. A rigorous treatment of this problem demands the introduction of contact deformation equations to accurately capture the micromechanical response of interacting roughness asperities.

The deformation problems of sphere-plane contact (point contact) and cylinder-plane contact (line contact) have become core research topics in three-dimensional and two-dimensional mechanics, respectively. In the study of three-dimensional contact problems, the conventional approach simplifies the microscopic contact between two deformable rough surfaces as a contact model of two spheres with different curvature radii (

,

), elastic moduli (

,

), Poisson’s ratios (

,

), and yield strengths (

,

). Through equivalent transformation analysis, a spherical asperity model is established with an equivalent curvature radius

and an equivalent elastic modulus

. Under normal contact loading, this model determines the critical interference

at which yielding occurs, ultimately forming a circular microscopic contact area a′ with radius

, as illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2.

The dimensionless local contact interference

and the radius of curvature of the meshing interface asperity

are represented as

For textured meshing interfaces with effective elastic-plastic material properties (and), various deformation modes may exhibit at the micro-asperity level depending on the values of and, which are functions ofandas shown in Equation (8). The microcontact meshing behavior of textured interfaces is simply described by elastic deformation and fully plastic deformation. A more realistic description would include elastic deformation, elastic-plastic deformation, and fully plastic deformation, while a more precise characterization would involve elastic deformation, linear elastic-plastic deformation, nonlinear elastic-plastic deformation, transient fully plastic deformation, and steady-state fully plastic deformation. Even without considering interfacial strain hardening, the relationship between the dimensionless average contact pressure and the real textured meshing contact area is established for the three deformation modes at the micro-asperity level: elastic deformation, elastic-plastic deformation, and fully plastic deformation.

The deformation mode of a textured meshing interface under micro-contact is governed by the local asperity interference

and the effective elastic-plastic material properties

and

, as illustrated in

Figure 2. A single dimensionless parameter (

) fails to effectively characterize the deformation evolution in the elastic-plastic transition regime. Instead, it is preferable to treat the ratios

and

as independent dimensionless parameters. The micro-contact parameters of the meshing interface, specifically the dimensionless average contact pressure

and the ratio of local asperity contact area to real meshing contact area

, must be comprehensively analyzed across a wide range of

and

values.

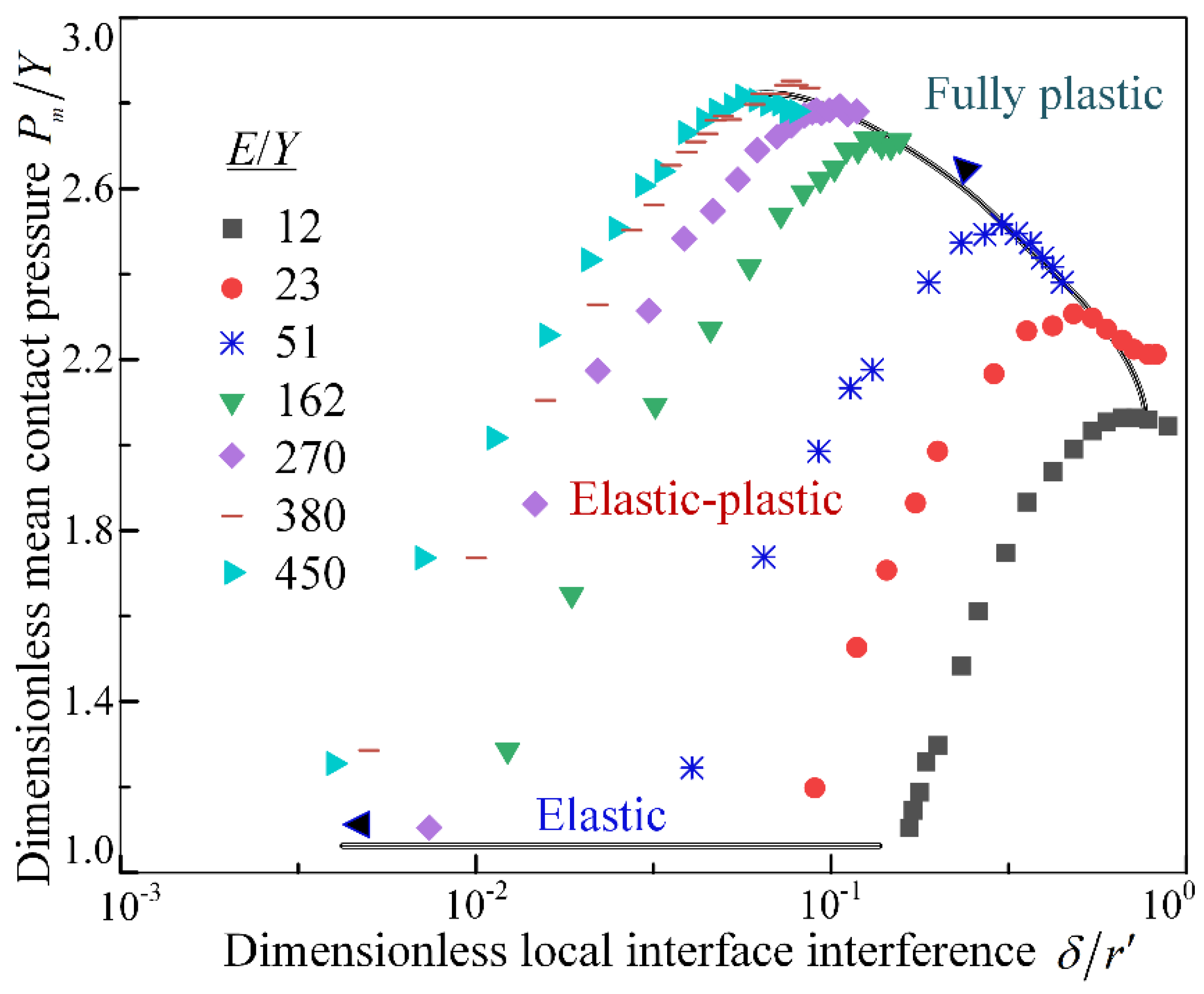

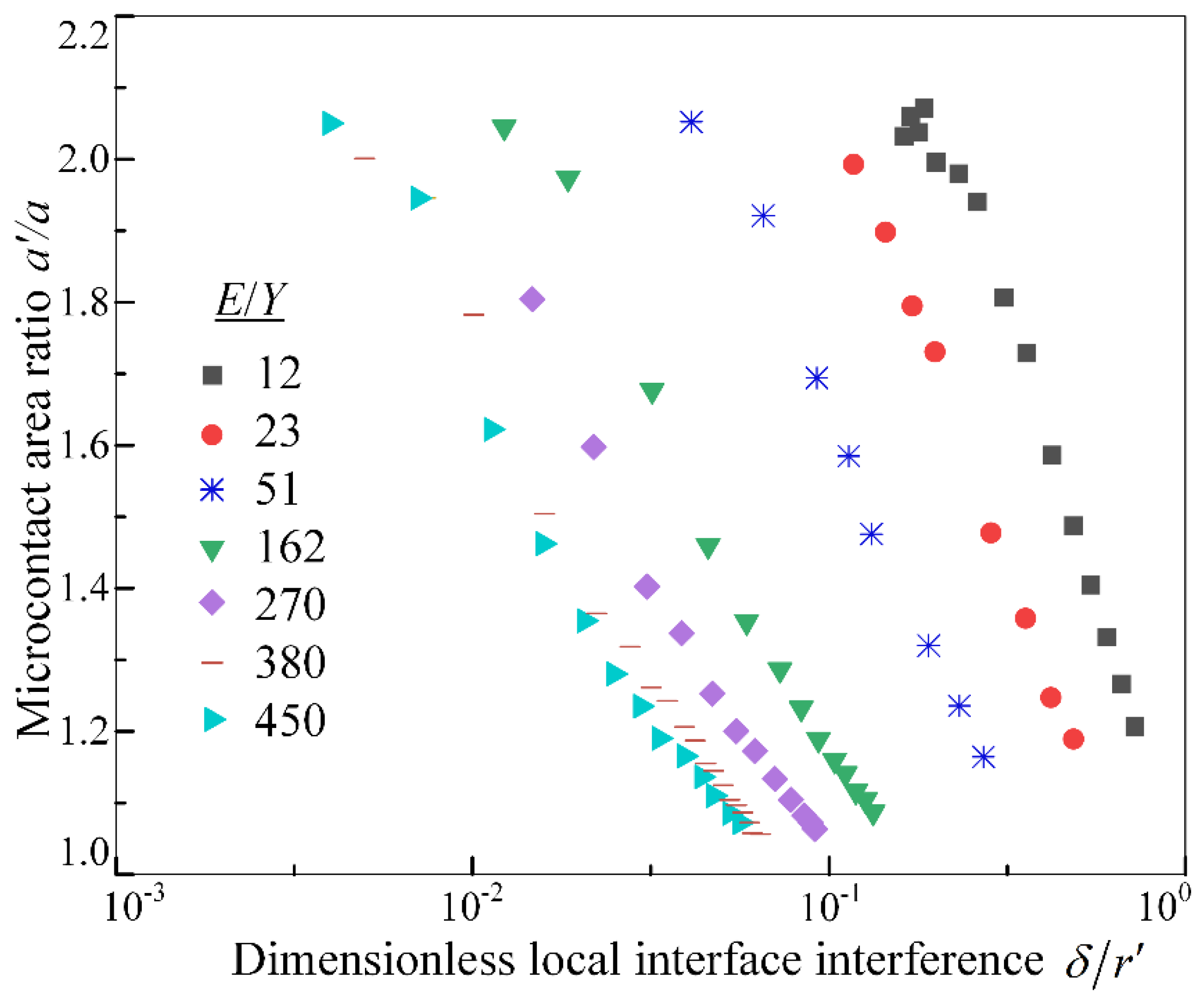

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 respectively present the finite element simulation results in the elastic-plastic deformation region. When

ranges between 12-450, the variation patterns of

and the corresponding

with

are revealed. All simulation cases indicate that yielding begins at

. According to Hertz theory, this implies that elastic deformation occurs within the dimensionless range of local micro-asperity meshing interface interference

.

Under normal circumstances, the fractal roughness of micro-textures, the contact load of the meshing interface, and the actual contact area all tend to increase with the increase of the fractal dimension. This is because when the fractal dimensionis high, the fractal texture interface will exhibit relatively smooth and dense surface morphological characteristics. This surface morphology significantly enhances the micro-contact load-bearing capacity, thereby leading to an increase in the actual contact area. Meanwhile, as the fractal roughnessof micro-textures gradually decreases, the contact load and the actual contact area will also show a similar increasing trend. The reason is that a high value means that the surface profile is relatively rough and not dense enough, which directly results in a smaller actual contact area and a correspondingly lower micro-contact load-bearing capacity.

The aforementioned theoretical analysis reveals the influence of the configuration and material parameters on the evolution of the real contact area in multi-scale fractal micro-textured interface morphology. It provides direct guidance for experimental evaluation methods of the real contact area of meshing interfaces, which are constrained by the sampling length and resolution of detection devices. It is particularly pointed out that the multiscale microcontact mechanics analysis is applied to assess the real contact area detection data of meshing interfaces obtained by various experimental techniques such as optical interferometry, X-ray, and tomography scanning. The multiscale microcontact mechanics analysis framework can also be used to evaluate the reliability of non-smooth meshing interface micro-asperity theory and textured micro-element elastic models in characterizing the contact mechanical behavior of multiscale surface textures. Furthermore, the micro-asperity contact mechanics theory described in this topic can be extended by introducing a more comprehensive theoretical system (micro-contact elastoplastic theory) to incorporate the coupled thermoelastic deformation effects between adjacent micro-asperities of the meshing interface under high-load conditions, where elastoplastic behavior dominates.

4. MultiscaleThermomechanicsCharacteristicsAnalysis ofMeshingInterfaceMicro-AsperityContact

While the meshing interface thermal resistance phenomenon has long been recognized, its inconsistency is intricate and challenging to explain, attributed to the combined influence of factors such as the micro-textured morphology of the meshing interface, applied contact pressure, and the thermomechanics characteristics of micro-contact multiscale elements. The thermal resistance

of the meshing interface is a thermal transfer limiting phenomenon dominated by multiscale contact thermo-mechanical coupling effects, which is particularly significant in line contact gear systems with dynamic micro-texture features. As shown in

Figure 3, due to the typical multiscale fractal characteristics of the micro-asperities on the meshing interface, the actual effective contact area

is significantly smaller than the apparent contact area

. The thermal conduction process of the micro-textured meshing interface has the following characteristics: (1) The thermal flow transmission path is strictly limited by the micro-texture morphological features determined by fractal parameters. (2) The thermal transfer efficiency depends on the distribution characteristics of micro-contact points under the interface’s elastic-plastic deformation state. (3) The thermo-mechanical coupling effect at the microscopic scale causes a significant two-way interaction between thermal conduction and elastic deformation. This complex thermal transfer mechanism requires a multiscale thermodynamic analysis method to accurately characterize its thermal transfer behavior, by considering the micro-contact characteristics and thermomechanical coupling effects of the fractal meshing interface.

The characteristics of microcontact thermal resistance depend on the mechanical and thermophysical properties of the textured micro-elements, the morphology of the micro-textured meshing interface, and any interstitial material (or film) that may exist between the gears interfaces. Considering a vacuum environment where convective thermal transfer is absent and thermal conduction is negligible, the interfacial thermal resistance characteristics can be analyzed through the thermal conduction of the micro-textured contact points. The contact thermal conductivity coefficient

of the textured micro-elements is expressed as

where,

is the total thermal flux load between the meshing interfaces, and

, where

and

are the nominal contact temperatures of meshing interfaces (1) and (2), respectively.

and

represent the thermal conductivities of the meshing interfaces (1) and (2), respectively.

is the total number of micro-asperity contacts in the meshing domain when the interference amount of the textured interface is

. The value of

is determined by

, and the specific expression is selected from the equations based on the deformation mode.

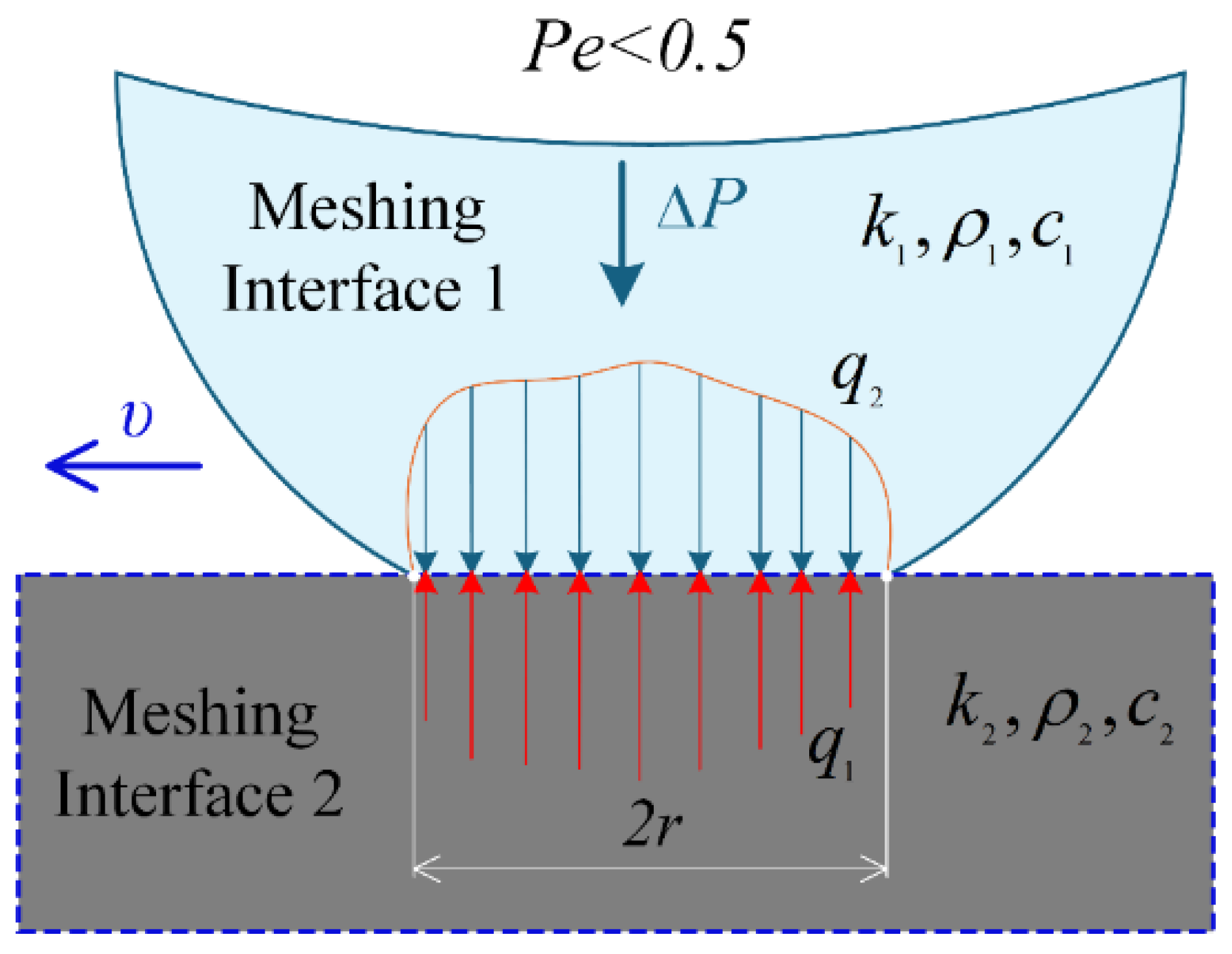

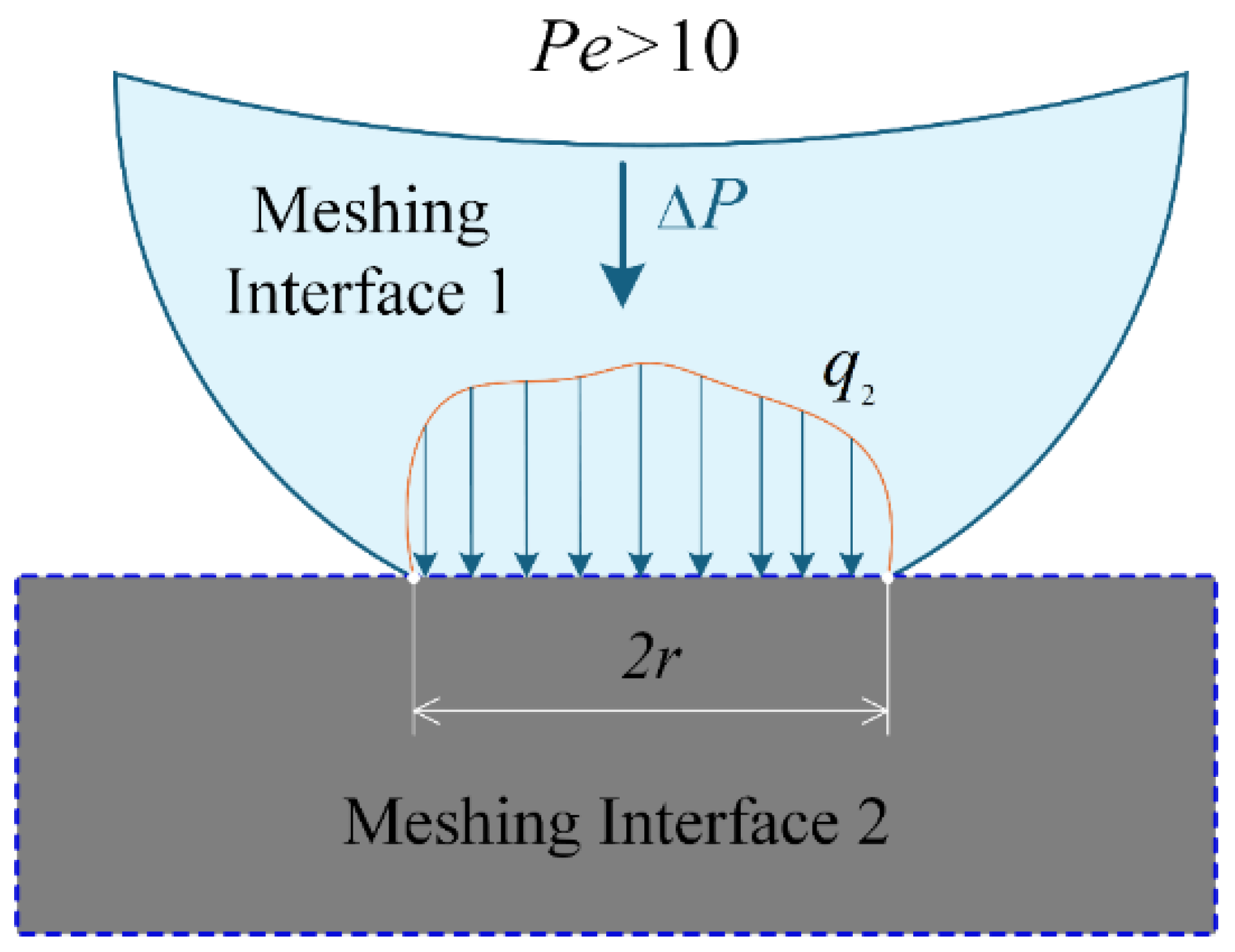

In the rolling/sliding line contact meshing interface, micro-asperities not only limit the thermal flux conduction but also cause the gear surface temperature to rise. Based on the two-dimensional fractal thermal conduction theory of line contact interface with the distribution density function of gear surface temperature rise, this study fully considers the proportion of the actual contact area affected by the gear surface temperature rise and the maximum temperature rise within the fractal domain under high-speed/low-speed rolling/sliding line contact conditions, and introduces a three-dimensional fractal method based on the dimensionless average temperature rise

. This method is proposed at the micro-asperity contact by simplifying the concept.

where

denotes the mean temperature rise during low-speed rolling/sliding, while

represents the mean temperature rise during high-speed rolling/sliding. The occurrence of low-speed or high-speed rolling/sliding is determined by the Peclet number

, where

indicates the relative sliding velocity at the micro-contact interface,

is density, and

is specific thermal capacity. For low-speed rolling/sliding (

), the thermal flux will conduct into both meshing interfaces see

Figure 6. Whereas for high-speed rolling/sliding (

), the thermal flux will transfer from the hotter micro-interface to the relatively cooler one, as illustrated in

Figure 7.

In the analysis of microcontact thermal characteristics, the meshing interface microtexture morphology and thermodynamic properties are optimized and corrected through iterative methods until the microcontact analysis yields a distribution of micro-asperity contact unit sizes that meets the following conditions: under the given contact load, apparent contact area, rolling and sliding speed, and microcontact friction coefficient, the temperature increase at the meshing interface is within the expected range.

This analysis is based on the following assumptions: 1) The influence of the thermoelastic effect on the deformation of micro-asperity contact can be considered a secondary factor; 2) The micro-asperity contact area used in the temperature calculation is determined by the contact mechanics method described in the previous section. To calculate the thermoelastic performance parameters corresponding to the micro-asperity contact area required under specific temperature rise conditions, they can be substituted into the corresponding contact mechanics equations after the iterative calculations are completed. It should be noted that although this method achieves indirect coupling of thermal and mechanical analyses, it does not directly consider the effect of temperature on the size of micro-asperity contact units. For more accurate analysis, a fully coupled thermomechanical analysis method can be employed to solve the meshing interface heat conduction process and contact deformation behavior simultaneously.

5. Analysis ofMeshingLoad-BearingCharacteristics ofTexturedInterfaceConsideringFractalDimension

This study is based on fractal theory and establishes a fractal characterization parameter system that considers the characteristics of micro-contact elements of textured interfaces. Through theoretical derivation, the micro-contact load equation and actual contact area equation between textured micro-elements of meshing interfaces are obtained. The influence of mechanisms of key parameters, such as the friction coefficient and the peak amplitude of micro-asperities, on the mechanical properties of textured interfaces (including normal stiffness, viscous damping, and average contact load coefficient) are analyzed. A quantitative relationship model between the morphological characteristics of textured micro-elements and the meshing load-bearing characteristics is constructed. Based on the established mathematical model of micro-contact of textured interfaces, the dynamic evolution laws of meshing load-bearing characteristics of textured interfaces under different fractal characterization parameters are studied using MATLAB numerical simulation methods. The research results can provide theoretical basis and parameter guidance for the optimization design of meshing tooth surface texture micro-element configurations, thereby achieving the optimal load-bearing performance of textured interfaces.

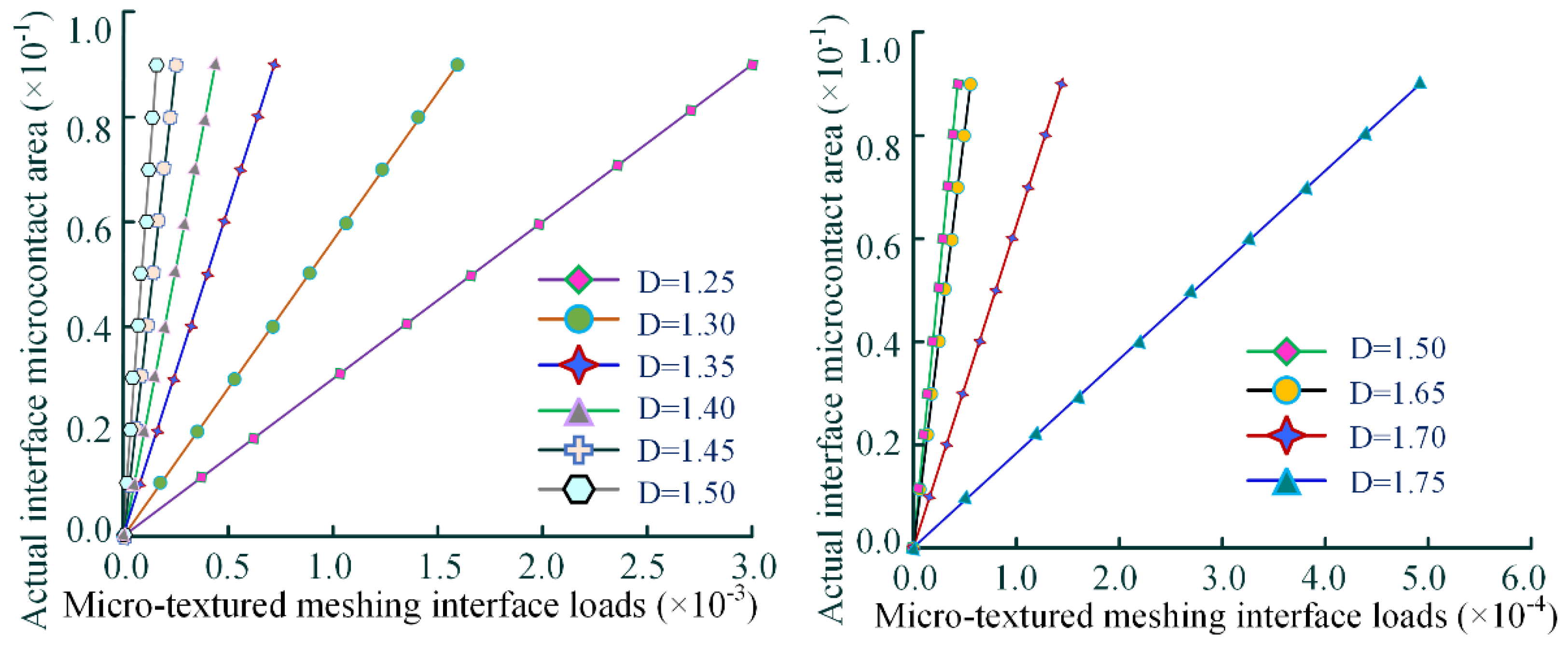

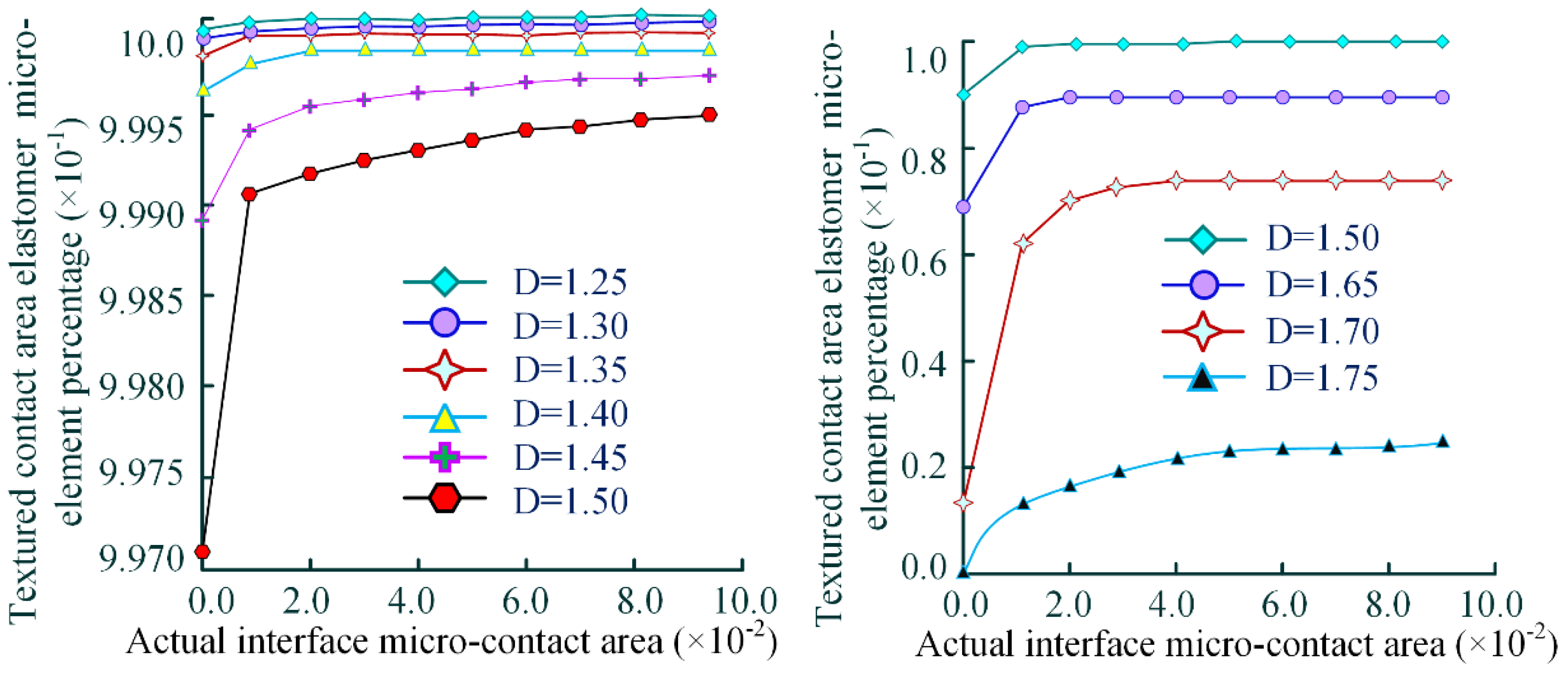

Based on different fractal dimensions and using MATLAB simulations, the relationship between the contact load of textured micro-elements and the actual contact area of the interface within the meshing region is analyzed. As shown in

Figure 8 (left), under the same meshing load, as the contact area of the textured interface increases, the unit micro-element area decreases, and the load-bearing capacity of the meshing interface is enhanced. The results indicate a proportional linear relationship between the load of the textured interface and the actual contact area. The analysis shows that as the fractal dimension increases, the slope of the variation curve gradually increases and reaches its maximum value at a fractal dimension of [

], thereby demonstrating that the textured interface exhibits the best average contact load coefficient at this fractal dimension. In

Figure 8 (right), it can be observed that at a fractal dimension of [

], if the slope of the variation curve shows a declining trend, it indicates the existence of an optimal constant value for this fractal dimension. Specifically, when the fractal dimension of the textured micro-elements is [

], the micro-contact interface achieves the best meshing load-bearing performance.

The simulation results in

Figure 9 demonstrate a significant positive correlation between the asperities micro-contact area of the textured interface and the proportion of elastic micro-elements: as the textured contact area of the gear pair tooth surfaces increases, the proportion of elastic micro-elements in the micro-contact area of the meshing domain shows a monotonically increasing trend.

In contrast, the fractal dimension of the micro-texture has a pronounced negative impact on the proportion of elastic micro-elements, the proportion of elastic micro-elements decreases systematically with the increase of fractal dimension. It is particularly noteworthy that when the fractal dimension reaches the critical value [], this downward trend accelerates significantly. This phenomenon reveals the essential influence of the increase in fractal dimension on the asperities micro-contact mechanical behavior of the micro-textured meshing interface: the increase in fractal dimension significantly enhances the stress concentration effect at the tips of the asperities micro-contact units, thereby leading to the rapid expansion of the plastic deformation area and ultimately resulting in a substantial decrease in the proportion of elastic micro-elements.