Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

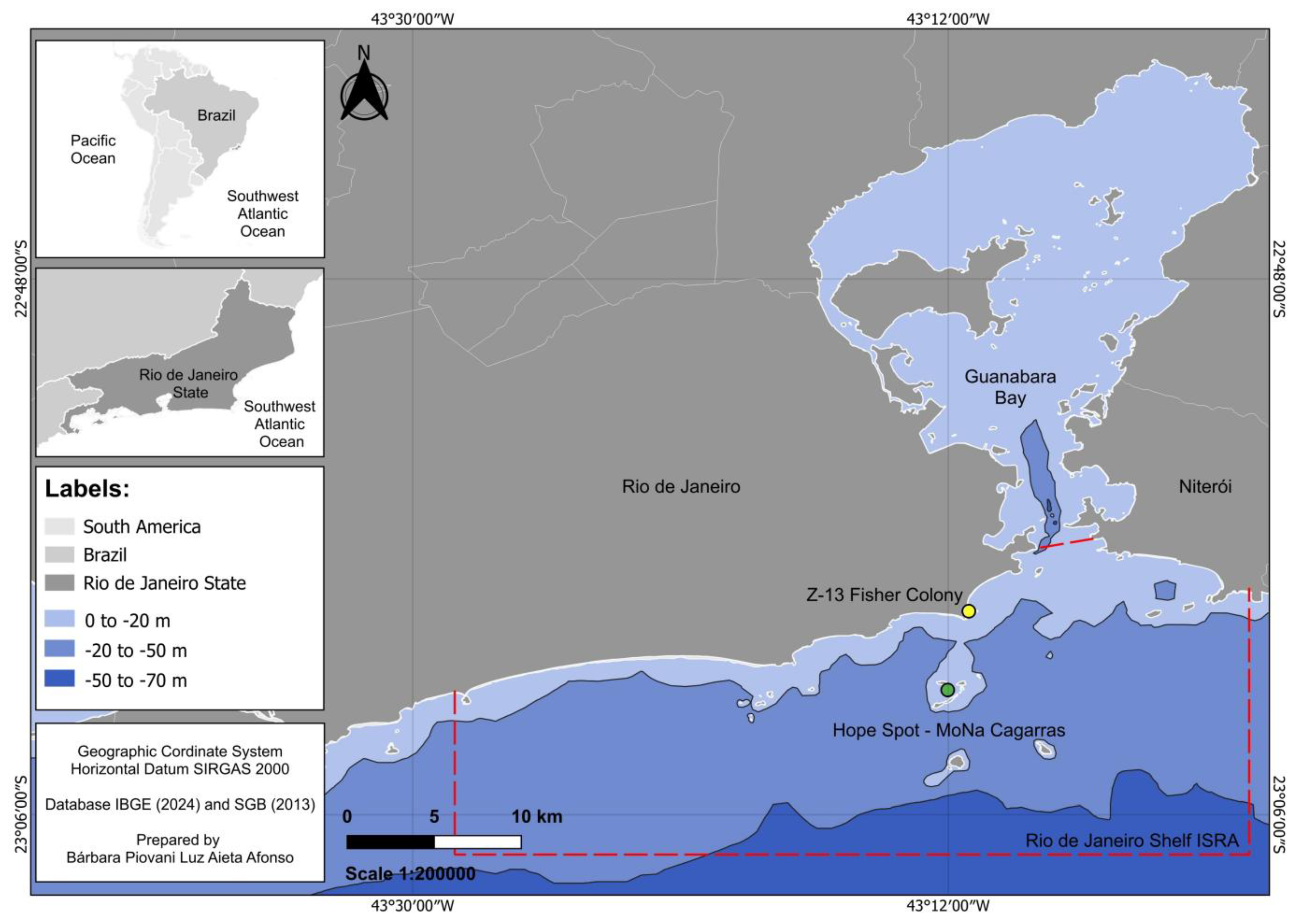

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Source

2.3. Fishery Data and Biological Information

2.4. Productivity and Susceptibility Analysis (PSA)

3. Results

3.1. Fishery Data and Species Composition

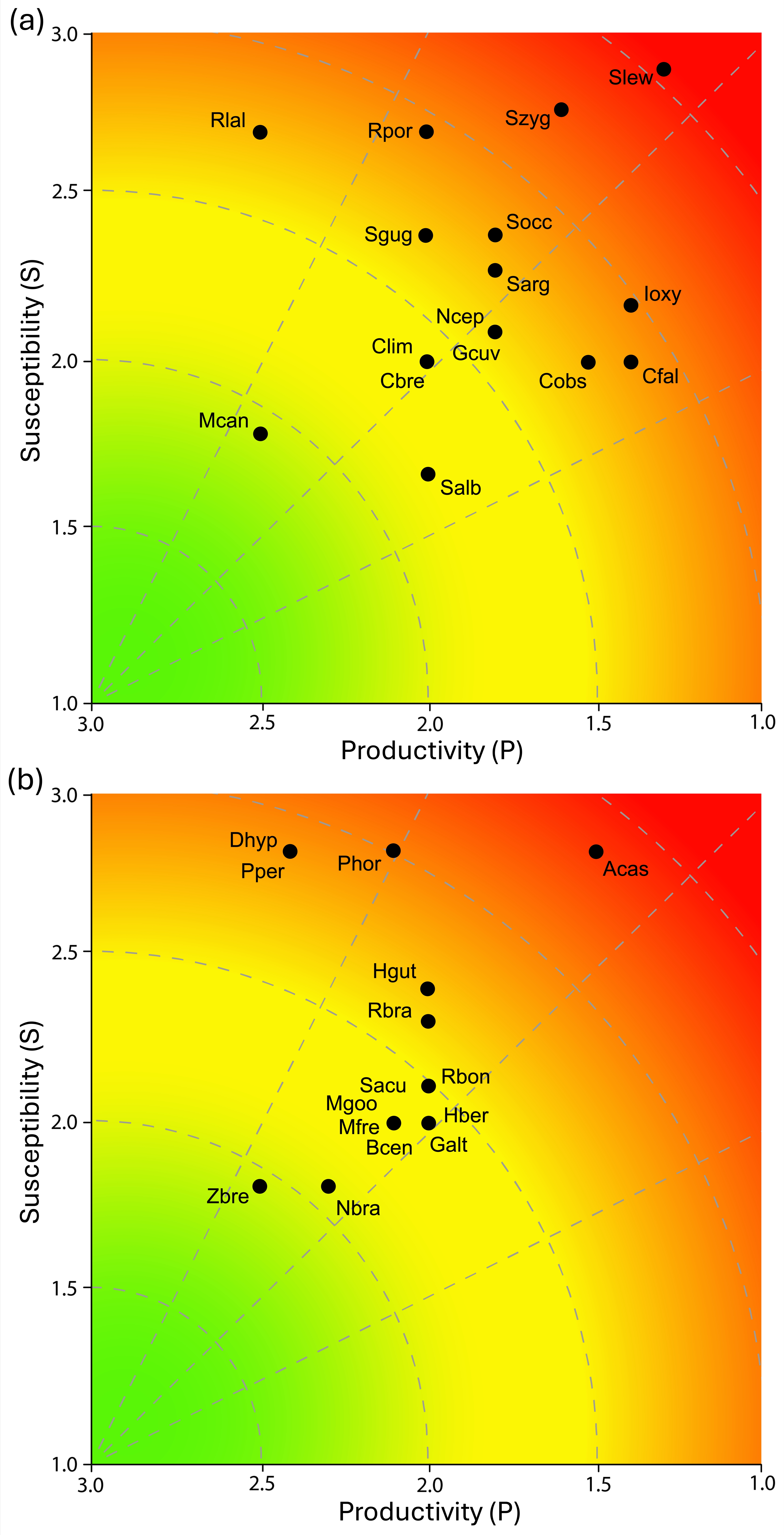

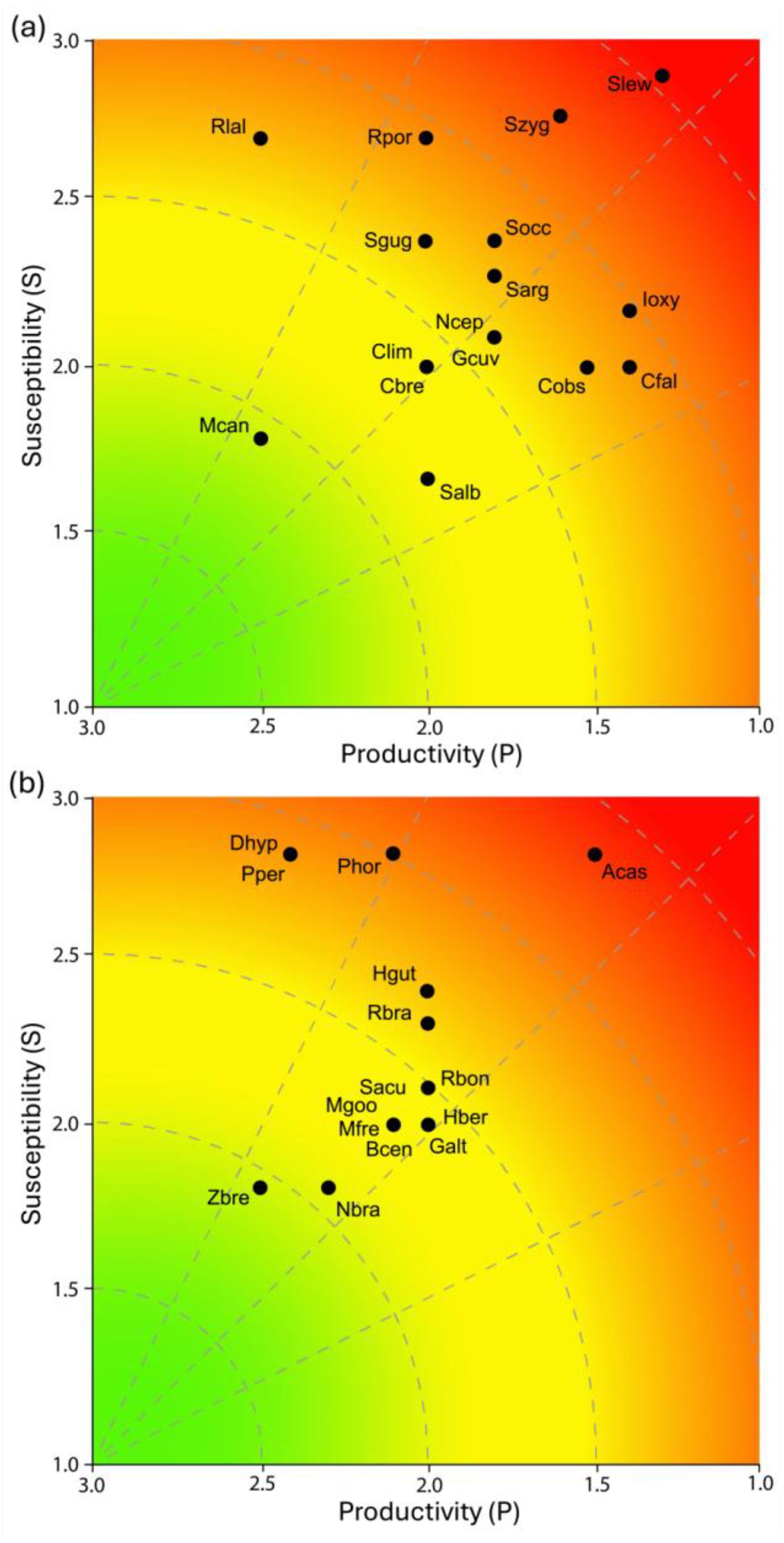

3.2. Productivity and Susceptibility Analysis (PSA)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

References

- Andrade, A.C.; Silva-Junior, L.C.; Vianna, M. Reproductive biology and population variables of the Brazilian sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon lalandii (Müller & Henle, 1839) captured in coastal waters of south-eastern Brazil. J. Fish Biol. 2008, 72, 473–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aximoff, I.; Cumplido, R.; Rodrigues, M.T.; de Melo, U.G.; Netto, E.B.F.; Santos, S.R.; Hauser-Davis, R.A. New Occurrences of the Tiger Shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) (Carcharhinidae) off the Coast of Rio de Janeiro, Southeastern Brazil: Seasonality Indications. Animals 2022, 12, 2774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, R.; Ferretti, F.; Flemming, J.M.; Amorim, A.; Andrade, H.; Worm, B.; Lessa, R. Trends in the exploitation of South Atlantic shark populations. Conserv. Biol. 2016, 30, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto, R.; Bornatowski, H.; Motta, F.; Santander-Neto, J.; Vianna, G.; Lessa, R. Rethinking use and trade of pelagic sharks from Brazil. Mar. Policy 2017, 85, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, V.S.; Fabré, N.N.; Malhado, A.C.M.; Ladle, R.J. Tropical Artisanal Coastal Fisheries: Challenges and Future Directions. Rev. Fish. Sci. Aquac. 2014, 22, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begot, L.H.; Vianna, M. Frota pesqueira costeira do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. Bol. Inst. de Pesca 2014, 40, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Bornatowski, H.; Heithaus, M.R.; Abilhoa, V.; Corrêa, M.F.M. Feeding of the Brazilian sharpnose shark Rhizoprionodon lalandii (Müller & Henle, 1839) from southern Brazil. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2012, 28, 623–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornatowski, H.; Braga, R.R.; Vitule, J.R.S. Shark Mislabeling Threatens Biodiversity. Science 2013, 340, 923–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornatowski, H.; Navia, A.F.; Braga, R.R.; Abilhoa, V.; Corrêa, M.F.M. Ecological importance of sharks and rays in a structural foodweb analysis in southern Brazil. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 71, 1586–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornatowski, H.; Braga, R.R.; Kalinowski, C.; Vitule, J.R.S. “Buying a Pig in a Poke”: The Problem of Elasmobranch Meat Consumption in Southern Brazil. Ethnobiol. Lett. 2015, 6, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bornatowski, H.; Braga, R.R.; Barreto, R.P. Elasmobranch Consumption in Brazil: Impacts and 4 Consequences - Chapter 10. In Advances in Marine Vertebrate Research in Latin America: Technological Innovation and Conservation; Rossi-Santos, M.R., Finkl, C.W., Eds.; New York, United States of America: Springer International Publishing, Coastal Research Library: 2018; pp. 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brasil., 2022a. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Portaria MMA nº 148, de 07 de junho de 2022. Altera os Anexos da Portaria nº 443, de 17 de dezembro de 2014, da Portaria nº 444, de 17 de dezembro de 2014, e da Portaria nº 445, de 17 de dezembro de 2014, referentes à atualização da Lista Nacional de Espécies Ameaçadas de Extinção. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF, ano 160, n. 108, p. 74, 08 jun. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/web/dou/-/portaria-mma-n-148-de-7-de-junho-de-2022-406272733 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Brasil., 2022b. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Portaria GM/MMA nº 300, de 13 de dezembro de 2022. Revoga os Atos da Portaria nº 443, de 17 de dezembro de 2014, da Portaria nº 444, de 17 de dezembro de 2014, da Portaria nº 445, de 17 de dezembro de 2014, da Instrução Normativa nº 1, de 12 de fevereiro de 2015, da Portaria nº 98, de 28 de abril de 2015, da Portaria nº 162, de 08 de junho de 2015, da Portaria nº 163, de 08 de junho de 2015, da Portaria nº 395, de 1º de setembro de 2016, da Portaria nº 161, de 20 de abril de 2017, da Portaria nº 201, de 31 de maio de 2017, da Portaria nº 217, de 19 de junho de 2017, da Portaria nº 73, de 26 de março de 2018, da Portaria nº 148, de 7 de junho de 2022 e da Portaria nº 229, de 5 de setembro de 2022, referentes à atualização da Lista Nacional de Espécies Ameaçadas de Extinção. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF, ano 160, n. 234, p. 75-118, 14 dez. 2022. ISSN 1677-7042. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-gm/mma-n-300-de-13-de-dezembro-de-2022-450425464 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Brasil., 2023. Ministério do Meio Ambiente. Portaria nº 354, de 27 de janeiro de 2023. Revoga os Atos da Portaria MMA nº 299, de 13 de dezembro de 2022, e nº 300, de 13 de dezembro de 2022. Repristinados os seguintes atos do MMA da Portaria nº 443, de 17 de dezembro de 2014; Portaria nº 444, de 17 de dezembro de 2014; Portaria nº 445, de 17 de dezembro de 2014; Instruçao Normativa nº 1, de 12 de fevereiro de 2015; Portaria nº 98, de 28 de abril de 2015; Portaria nº 162, de 08 de junho de 2015; Portaria nº 163, de 08 de junho de 2015; Portaria nº 395, de 1º de setembro de 2016; Portaria nº 161, de 20 de abril de 2017; Portaria nº 201, de 31 de maio de 2017; Portaria nº 217, de 19 de junho de 2017; Portaria nº 73, de 26 de março de 2018; Portaria nº 148, de 7 de junho de 2022; Portaria nº 229, de 5 de setembro de 2022; Portaria nº 43, de 31 de janeiro de 2014; Portaria nº 162, de 11 de maio de 2016; e Portaria nº 444, de 26 de novembro de 2018, com inclusão de espécies na Portaria nº 148, de 7 de junho de 2022, da Lista Nacional de Espécies Ameaçadas de Extinçao. Diário Oficial da União: seção 1, Brasília, DF, ano 160, n. 21, p. 72-73, 27 jan. 2023. ISSN 1677-7042. Available online: https://www.in.gov.br/en/web/dou/-/portaria-mma-n-354-de-27-de-janeiro-de-2023-460770327 (accessed on 29 July 2025)ISSN 1677-7042.

- Bravo-Zavala, F.G.; Pérez-Jiménez, J.C.; Tovar-Ávila, J.; Arce-Ibarra, A.M. Vulnerability of 14 elasmobranchs to various fisheries in the southern Gulf of Mexico. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2022, 73, 1064–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calado, L.; Da Silveira, I.C.A.; Gangopadhyay, A.; De Castro, B.M. Eddy-induced upwelling off Cape São Tomé (22ºS, Brazil). Continental Shelf Research 2010, 30, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonel, C.A.A.H.; Galeão, A.C.N. A stabilized finite element model for the hydrothermodynamical simulation of the Rio de Janeiro coastal ocean. Commun. Numer. Methods Eng. 2007, 23, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreón-Zapiain, M.T.; Tavares, R.; Favela-Lara, S.; Oñate-González, E.C. Ecological Risk Assessment with integrated genetic data for three commercially important shark species in the Mexican Pacific. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 39, 101431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, R.d.S.; Canuel, E.A.; Macko, S.A.; Lopes, M.B.; Luz, L.G.; Jasmim, L.N. On the accumulation of organic matter on the southeastern Brazilian continental shelf: a case study based on a sediment core from the shelf off Rio de Janeiro. Braz. J. Oceanogr. 2012, 60, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claireaux, M.; Jørgensen, C.; Enberg, K. Evolutionary effects of fishing gear on foraging behavior and life-history traits. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 10711–10721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compagno, L.J.V. Checklist of living elasmobranchs. Pp. 471-498. In Sharks, Skates, and Rays - The Biology of Elasmobranch Fishes. 1a Ed.; Hamllet, W.C., Ed.; Baltimore, United States of America: John Hopkins University Press, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Compagno, L.J.V. 2001. Sharks of the world - An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Volume 2. Bullhead, Mackerel and Carpet sharks (Heterodontiformes, Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes). FAO, Species Catalogue for Fishery Purposes., 2001. [CrossRef]

- Cope, J.M.; DeVore, J.; Dick, E.J.; Ames, K.; Budrick, J.; Erickson, D.L.; Grebel, J.; Hanshew, G.; Jones, R.; Mattes, L.; et al. An Approach to Defining Stock Complexes for U.S. West Coast Groundfishes Using Vulnerabilities and Ecological Distributions. North Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2011, 31, 589–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, E.; Arocha, F.; Beerkircher, L.; Carvalho, F.; Domingo, A.; Heupel, M.; Holtzhausen, H.; Santos, M.N.; Ribera, M.; Simpfendorfer, C. Ecological risk assessment of pelagic sharks caught in Atlantic pelagic longline fisheries. Aquat. Living Resour. 2009, 23, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés, E.; Brooks, E.N.; Shertzer, K.W. Risk assessment of cartilaginous fish populations. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2014, 72, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, M.M.; Szynwelski, B.E.; de Freitas, T.R.O. Biodiversity on sale: The shark meat market threatens elasmobranchs in Brazil. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2021, 31, 3437–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.D.; Baum, J.K. Extinction Risk and Overfishing: Reconciling Conservation and Fisheries Perspectives on the Status of Marine Fishes. Sci. Rep. 2012, 2, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, C.M.; Agusti, S.; Barbier, E.; Britten, G.L.; Castilla, J.C.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Fulweiler, R.W.; Hughes, T.P.; Knowlton, N.; Lovelock, C.E.; et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature 2020, 580, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, L.M.; Griffiths, S.P. Assessing attribute redundancy in the application of productivity-susceptibility analysis to data-limited fisheries. Aquat. Living Resour. 2019, 32, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Davidson, L.N.; Fordham, S.V.; Bräutigam, A.; Sant, G.; Welch, D.J. Challenges and Priorities in Shark and Ray Conservation. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R565–R572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dulvy, N.K.; Pacoureau, N.; Rigby, C.L.; Pollom, R.A.; Jabado, R.W.; Ebert, D.A.; Finucci, B.; Pollock, C.M.; Cheok, J.; Derrick, D.H.; et al. Overfishing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Curr. Biol. 2021, 31, 4773–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainability in action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. Fisheries operations: Guidelines to prevent and reduce bycatch of marine mammals in capture fisheries; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture: Sustainability in action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- FIPERJ. Fundação Instituto de Pesca do Estado do Rio de Janeiro., 2015. Available online: http://www.fiperj.rj.gov.br/fiperj_imagens/arquivos/revistarelatorios2015.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- FIPERJ. Fundação Instituto de Pesca do Estado do Rio de Janeiro., 2016. Relatório 2016. Available online: http://www.fiperj.rj.gov.br/fiperj_imagens/arquivos/revistarelatorios2015.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- FIPERJ. Fundação Instituto de Pesca do Estado do Rio de Janeiro., 2020. Estatística Pesqueira do Estado do Rio de Janeiro. PMAP-RJ, Projeto de Monitoramento da Atividade Pesqueira no Estado do Rio de Janeiro (2018-2019). In: Projeto de Monitoramento da Atividade Pesqueira no Estado do Rio de Janeiro., 2020. Relatório Técnico Consolidado Final-RTF. 1. Available online: http://www.fiperj.rj.gov.br/index.php/publicacao/index/1 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Freire, K.M.F.; Aragão, J.A.N.; Araújo, A.R.R.; et al. Reconstruction of catch statistics for Brazilian marine waters (1950-2010): fisheries catch reconstructions for Brazil's mainland and oceanic islands. Fish. Centre Res. Rep. 2015, 23, 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, K.M.F.; Almeida, Z.d.S.d.; Amador, J.R.E.T.; Aragão, J.A.; Araújo, A.R.d.R.; Ávila-Da-Silva, A.O.; Bentes, B.; Carneiro, M.H.; Chiquieri, J.; Fernandes, C.A.F.; et al. Reconstruction of Marine Commercial Landings for the Brazilian Industrial and Artisanal Fisheries From 1950 to 2015. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froese, R.; Pauly, D. FishBase: world wide web electronic publication. Available online: https://www.fishbase.org (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Furlong-Estrada, E.; Galván-Magaña, F.; Tovar-Ávila, J. Use of the productivity and susceptibility analysis and a rapid management-risk assessment to evaluate the vulnerability of sharks caught off the west coast of Baja California Sur, Mexico. Fish. Res. 2017, 194, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, A.J.; Kyne, P.M.; Hammerschlag, N. Ecological risk assessment and its application to elasmobranch conservation and management. J. Fish Biol. 2012, 80, 1727–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasalla, M.A.; Rodrigues, A.R.; Duarte, L.F.; Sumaila, U.R. A comparative multi-fleet analysis of socio-economic indicators for fishery management in SE Brazil. Prog. Oceanogr. 2010, 87, 304–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.; Smith, A.; Stobutzki, I.; Bulman, C.; Daley, R.; Dambacher, J.; Deng, R.; Dowdney, J.; Fuller, M.; Furlani, D.; et al. Ecological risk assessment for the effects of fishing. Fish. Res. 2011, 108, 372–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobday, A.J.; Smith, A.; Webb, H.; Daley, R.; Wayte, S.; Bulman, C.; Dowdney, J.; Williams, A.; Sporcic, M.; Dambacher, J.; Fuller, M.; Walker, T. Ecological Risk Assessment for the Effects of Fishing: Methodology. Report R04/1072 for the Australian Fisheries Management Authority, Canberra. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hordyk, A.R.; Carruthers, T.R. A quantitative evaluation of a qualitative risk assessment framework: Examining the assumptions and predictions of the Productivity Susceptibility Analysis (PSA). PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0198298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, M.M.; Studd, E.K.; Menzies, A.K.; Boutin, S. To Everything There Is a Season: Summer-to-Winter Food Webs and the Functional Traits of Keystone Species. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2017, 57, 961–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyde, C.A.; di Sciara, G.N.; Sorrentino, L.; Boyd, C.; Finucci, B.; Fowler, S.L.; Kyne, P.M.; Leurs, G.; Simpfendorfer, C.A.; Tetley, M.J.; et al. Putting sharks on the map: A global standard for improving shark area-based conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 968853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística., 2019. Available online: www.ibge.gov.br (accessed on 20 October 2024).

- ICMBIO. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade., 2010. MoNa do Arquipélago das Ilhas Cagarras. Available online: https://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/mona-do-arquipelago-das-ilhas-cagarras (accessed on 27 October 2024).

- ICMBio. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade., 2018a. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume VI - Peixes. ICMBio, Brasília - DF, Brazil, p. 1.235.

- ICMBio. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade., 2018b. Livro Vermelho da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçada de Extinção: Volume I. ICMBio / MMA, Brasília - DF, Brazil.

- ICMBio. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade., 2023. Plano de Ação Nacional para a Conservação dos Tubarões e Raias Marinhos Ameaçados de Extinção. Available online: https://pt.scribd.com/document/682264893/Livro-Pan-Tubaroes-2023-Vfinal-23-Digital-Compacto-Compressed-1 (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- ICMBio. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade., 2025. Sistema de Avaliação do Risco de Extinção da Biodiversidade - SALVE. Available online: https://salve.icmbio.gov.br/ (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- ISRA. Important Shark and Ray Area., 2025. IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group. Rio de Janeiro Shelf ISRA Factsheet. Dubai: IUCN SSC Shark Specialist Group., 2025. Available online: https://sharkrayareas.org/factsheets/rio-de-janeiro-shelf-isra/ (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature., 2022. Standards and Petitions Committee. Guidelines for Using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria. Version 15.1. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Committee., 2022. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/documents/RedListGuidelines.pdf.

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature., 2024. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2022-2., 2024. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- IUCN. International Union for Conservation of Nature., 2025. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2025-1., 2025. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 25 July 2025).

- Jacquet, J.L.; Pauly, D. Trade secrets: Renaming and mislabeling of seafood. Mar. Policy 2008, 32, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.R.; McFarlane, G.A. Marine fish life history strategies: applications to fishery management. Fish. Manag. Ecol. 2003, 10, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoroske, L.M.; Lewison, R.L. Addressing fisheries bycatch in a changing world. Frontiers in Marine Science 2015, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotas, J.E.; Vizuete, E.P.; Santos, R.A.; Baggio, M.R.; Salge, P.G.; Barreto, R. 2023. PAN Tubarões: Primeiro Ciclo do Plano de Ação Nacional para a Conservação dos Tubarões e Raias Marinhos Ameaçados de Extinção., 2023. ICMBio/CEPSUL, Brasília, DF, Brazil, p. 384.

- Le Grix, N.; Cheung, W.L.; Reygondeau, G.; Zscheischler, J.; Frölicher, T.L. Extreme and compound ocean events are key drivers of projected low pelagic fish biomass. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2023, 29, 6478–6492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, M.S.; Bertucci, T.C.P.; Rapagnã, L.; Tubino, R.d.A.; Monteiro-Neto, C.; Tomas, A.R.G.; Tenório, M.C.; Lima, T.; Souza, R.; Carrillo-Briceño, J.D.; et al. The Path towards Endangered Species: Prehistoric Fisheries in Southeastern Brazil. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0154476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loto, L.; Monteiro-Neto, C.; Martins, R.R.M.; Tubino, R.d.A. Temporal changes of a coastal small-scale fishery system within a tropical metropolitan city. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 153, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucifora, L.O.; García, V.B.; Worm, B. Global Diversity Hotspots and Conservation Priorities for Sharks. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e19356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, Í.; Santos, P.E.; Campos, R.; De Oliveira, C.A.C.R.; Wosnick, N.; Evangelista-Gomes, G.; Petrere Jr, M.; Bentes, B. Fishing profile and commercial landings of shark and batoids in a global elasmobranchs conservation hotspot. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2024, 96, e20231083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, A.A.; de Moraes, F.C.; Aguiar, A.A.; Hostim-Silva, M.; Santos, L.N.; Bertoncini, Á.A. Rocky reef fish biodiversity and conservation in a Brazilian Hope Spot region. Neotropical Ichthyol. 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, R.A.; Julio, T.G.; Sole-Cava, A.M.; Vianna, M. A new strategy proposal to monitor ray fins landings in south-east Brazil. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2019, 30, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.M.A.; Silva, T.S.M.; Fernandes, A.M.; Massone, C.G.; Carreira, R.S. Characterization of particulate organic matter in a Guanabara Bay coastal ocean transect using elemental, isotopic and molecular markers. PANAMJAS 2016, 11, 276–291. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, R.R.; Schwingel, P.R. Variação espaço-temporal da CPUE para o gênero Rhinobatos (Rajiformes, Rhinobatidae) na costa sudeste e sul do Brasil. Braz. J. Aquat. Sci. Technol. 2003, 7, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCully, S.R.; Scott, F.; Ellis, J.R.; Pilling, G.M. . Productivity and susceptibility analysis: Application and suitability for data poor assessment of elasmobranchs in northern European seas. ICCAT, Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. 2013, 69, 1679–1698. [Google Scholar]

- McGoodwin, J.R. Comprender las culturas de las comunidades pesqueras: clave para la ordenación pesquera y la seguridad alimentaria. FAO, Doc. Téc. Pesca, Roma 2002, 401, 1–301. [Google Scholar]

- Mejia-Falla, P.A.; Castro, E.R.; Ballesteros, C.A.; Bent-Hooker, H.; Caldas, J.P.; Rojas, A.; Navia, A.F. Effect of a precautionary management measure on the vulnerability and ecological risk of elasmobranchs captured as target fisheries. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2019, 31, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MPA. Ministério da Pesca e Aquicultura. Pesca Artesanal., 2014. Available online: http://www.mpa.gov.br/pesca/artesanal (accessed on 21 October 2024).

- MPF. Ministério Público Federal., 2017. Pesca artesanal legal: pescador da região sul / sudeste - conheça seus direitos e deveres!., 2017. MPF, 6ª Câmara de Coordenação e Revisão, Populações Indígenas e Comunidades Tradicionais, Brasília, DF, Brazil, p. 59.

- A Myers, R.; Worm, B. Extinction, survival or recovery of large predatory fishes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 2005, 360, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.S.; Grande, T.C.; Wilson, M.V.H. Fishes of the world, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New Jersey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Neves, R.A.; Miralha, A.; Guimarães, T.B.; Sorrentino, R.; Calderari, M.R.M.; Santos, L.N. Phthalates contamination in the coastal and marine sediments of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2023, 190, 114819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddone, M.; Awruch, C.A.; Barreto, R.R.; Charvet, P.; Chiaramonte, G.E.; Cuevas, J.M.; Dolphine, P.; Faria, V.V.; Paesch, L.; Rincon, G.; et al. guggenheim. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick, W.S.; et al. 2009. Use of productivity and susceptibility indices to determine the vulnerability of a stock: with example applications to six U.S. fisheries., 2009. NOAA Technical Memorandum, NMFS-F/SPO-101, Silver Spring, p. 104.

- Patrick, W.S.; Spencer, P.; Link, J.; Cope, J.; Field, J.; Kobayashi, D.; Lawson, P.; Gedamke, T.; Cortes, E.; Ormseth, O.; Bigelow, K.; Overholtz, W. Using productivity and susceptibility indices to assess the vulnerability of United States fish stocks to overfishing. Fish. Bull. 2010, 108, 305–322. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D.; Cheung, W.W.L. Sound physiological knowledge and principles in modeling shrinking of fishes under climate change. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 24, E15–E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauly, D.; Zeller, D. Catch reconstructions reveal that global marine fisheries catches are higher than reported and declining. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peckham, S.H.; Maldonado-Dias, D.; Koch, V.; Mancini, A.; Gaos, A.; Tinker, M.T.; Nichols, W.J. High mortality of loggerhead turtles due to bycatch, human consumption and strandings at Baja California Sur, Mexico, 2003 to 2007. Endangered Species Research 2008, 5, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, J.A.A.; Pezzuto, P.R.; Wahrlich, R.; Soares, A.L.S. Deep-water fisheries in Brazil: history status and perspectives. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Resources 2009, 37, 513542. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Jiménez, J.C.; Mendoza-Carranza, M. Occurrence of immature sharks in artisanal fisheries of the southern Gulf of Mexico. Arquivos de Ciências do Mar, Fortaleza, Brazil 2023, 56, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PMAP-RJ. Projeto de Monitoramento da Atividade Pesqueira na Bacia de Santos., 2020. Relatório Técnico consolidado: 2018-2019, p. 1943.

- PMAP-RJ. Projeto de Monitoramento da Atividade Pesqueira na Bacia de Santos., 2022. Relatório Técnico consolidado: 2019-2021.

- Pollom, R.; Barreto, R.R.; Charvet, P.; Chiaramonte, G.E.; Cuevas, J.M.; Faria, V.V.; Herman, K.; Montealegre-Quijano, S.; Motta, F.; Paesch, L.; et al. Atlantoraja platana. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pollom, R.; Barreto, R.R.; Charvet, P.; Chiaramonte, G.E.; Cuevas, J.M.; Faria, V.V.; Herman, K.; Montealegre-Quijano, S.; Motta, F.; Paesch, L.; et al. Dasyatis hypostigma. In The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Rigby, C.L.; Dulvy, N.K.; Barreto, R.R.; Carlson, J.; Fernando, D.; Fordham, S.; Francis, M.P.; Herman, K.; Jabado, R.W.; Liu, K.M.; et al. 2019. Sphyrna lewini. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species., 2019. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/pdf/2921825/attachment.

- Santos, P.R.; Balanin, S.; Gadig, O.B.; Garrone-Neto, D. The historical and contemporary knowledge on the elasmobranchs of Cananeia and adjacent waters, a coastal marine hotspot of southeastern Brazil. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2022, 51, 102224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.; Veloso, J.V.; Santos, T.B.; Bezerra, N.P.A.; Oliveira, P.; Hazin, F.H.V. An equatorial mid-Atlantic Ocean archipelago as nursery area for the cookiecutter shark: Investigating foraging strategies of neonates through bite mark inferences. J. Fish Biol. 2024, 104, 1290–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, R.; Cardoso, L.G.; Fischer, L.G.; Mourato, B.L.; Monteiro, D.S.; Sant’ana, R. Opening Pandora’s Box: Reconstruction of Catches in Southeast-South Brazil Revealed Several Threatened Elasmobranch Species under One Umbrella Name. Coasts 2024, 4, 552–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shester, G.G.; Micheli, F. Conservation challenges for small-scale fisheries: Bycatch and habitat impacts of traps and gillnets. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 1673–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva-Junior, L.C.; Andrade, A.C.; Vianna, M. Caracterização de uma pescaria de pequena escala em uma área de importância ecológica para elasmobrânquios, no Recreio dos Bandeirantes, Rio de Janeiro. Arquivos de Ciências do Mar, Fortaleza, Brazil 2008, 41, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, G.M.; Fernades, I.; Monteiro-Neto, C.; da Costa, M.R. Life-history traits, capture dynamics, and conservation status of key species landed by the artisanal gillnet fleet in the southwest Atlantic Ocean. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2025, 35, 461–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobutzki, I.; Miller, M.; Brewer, D. Sustainability of fishery bycatch: a process for assessing highly diverse and numerous bycatch. Environ. Conserv. 2001, 28, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stobutzki, I.C.; Miller, M.J.; Heales, D.S.; Brewer, D.T. Sustainability of elasmobranchs caught as bycatch in a tropical prawn (shrimp) trawl fishery. Fish. Bull. 2002, 100, 800–821. [Google Scholar]

- Suguio, K. 2003. Geologia Sedimentar. Ed. Edgard Blucher., 2003. São Paulo, Brazil.

- Tavares, R.; Carreon-Zapiain, M.T.; Perez-Jimenez, J.C. Vulnerability of elasmobranchs caught by artisanal fishery in the Southeastern Caribbean. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2024, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorson, J.T.; Munch, S.B.; Cope, J.M.; Gao, J. Predicting life history parameters for all fishes worldwide. Ecol. Appl. 2017, 27, 2262–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toussaint, A.; Brosse, S.; Bueno, C.G.; Pärtel, M.; Tamme, R.; Carmona, C.P. Extinction of threatened vertebrates will lead to idiosyncratic changes in functional diversity across the world. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentin, J.L. A ressurgência: Fonte de vida nos oceanos. Ciência Hoje 1994, 18, 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- Valentin, J.L.; Coutinho, R. Modelling maximum chlorophyll in the Cabo Frio (Brazil) upwelling: a preliminary approach. Ecol. Model. 1990, 52, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasconcellos, M.; Diegues, A.C.; Kalikoski, D.C. Coastal fisheries of Brazil. In Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean; Salas, S., Chuenpagdee, R., Charles, A., Seijo, J.C., Eds.; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, 544; FAO: Rome, 2011; pp. 73–116. [Google Scholar]

- Vianna, M.; Almeida, T. Bony fish bycatch in the southern Brazil pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus brasiliensis and F. paulensis) fishery. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2005, 48, 611–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visintin, M.R.; Perez, J.A.A. Vulnerabilidade de espécies capturadas pela pesca de emalhe-de-fundo no Sudeste-Sul do Brasil: produtividade-suscetibilidade (PSA). Bol. Do Inst. de Pesca 2016, 42, 119–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vooren, C.M.; Klippel, S. Ações para a Conservação de Tubarões e Raias no sul do Brasil. Eds.; Igaré: Porto Alegre, 2005; p. 161. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, T.I. Can shark resources be harvested sustainably? A question revisited with a review of shark fisheries. Mar. Freshw. Res. 1998, 49, 553–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosnick, N.; Martins, A.P.B.; Leite, R.D.; Giareta, E.P.; Faria, V.V.; Charvet, P. Brazil. In The global status of sharks, rays, and chimaeras; Jabado, R.W., Morata, A.Z.A., Bennett, R.H., Finucci, B., Ellis, J.R., Fowler, S.L., Grant, M.I., Barbosa Martins, A.P., Sinclair, S.L., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 441–456. [Google Scholar]

- Yokota, L.; Lessa, R.P. A nursery Area for Sharks and Rays in Northeastern Brazil. Environ. Biol. Fishes 2006, 75, 349–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamboni, A.; Dias, M. , 2020. Auditoria da pesca: Brasil 2020: uma avaliação integrada da governança, da situação dos estoques e das pescarias. Brasília - DF, Brazil: Oceana Brasil.

| Z-13 FISHER COLONY (C. P. Z-13): n, average, range and ±SD of the fleet, fishing and gear | |

| C. P. Z-13- DIVERSIFIED COASTAL MODE | LEGISLATION* |

| . Number of vessels (n (total): 19 (average of 10 active vessels/day (range: 00-14; average: 05-07 and; ±SD4-8 | |

| (minimum of 00 and maximum of 14); | |

| . Approx. total length: 05 m (traditional-artisanal boats) and 08 m (speedboats). With beams of 1.4-1.8 m; respectively; | √ |

| . Construction material: fiberglass (with wooden keel); | |

| . GT: ≤ 20 (artisanal fishing); | √ |

| . "Ages": traditional-artisanal boats 20+ years old and speedboats 8-16 years old; | |

| . Engine type: stern drive; | |

| . Power (HP) of diesel engines: "NSB" 75 and 90 / speedboats (gasoline and/or alcohol): 20-40 and 2-4 T; | |

| . Complements: Ursa 40 oil for diesel engines (traditional-artisanal boats) and 2 T oil for gasoline engines | |

| (speedboats); | |

| . Average consumption (sea autonomy): directly proportional to the distance from fishing grounds. | |

| Approximately 03 operational days with a full tank; | |

| . Number of crew/vessel: between 02-03 to 04 (range: 01-04; average: 03 and; ±SD2-3 (minimum of 01 and | |

| maximum of 04); | √ |

| . Materials: the most used gear are gillnets (passive fishing gear with varying dimensions, threads and | |

| meshes, with different buoys and weights - 100.0% of total-local elasmobranch landings during this study); | |

| . Gillnets height: ~02 m; | √ |

| . Configurations - Threads (mm)-meshes (mm): "Corvineiras" (mid-water and surface fishing): 40/60-50/60 | |

| (n = 147; 58.3%); "Linguadeiras" (for bottom fishing only): 50/110 (n = 111; 33.3%) and, "Come-dormes" | |

| (subsurface and mid-water fishing): 40/45-45/55 (n = 38; 8.4%); | √ |

| . Monofilament nylon threads: 0.5-1 mm, gauge (medium thickness); | √ |

| . Opening: 90-120 mm between opposite nodes; | √ |

| . Covers: 10-25 or up to 2,500 m for midwater and surface gillnets. When with two gillnets (or for bottom), | |

| reaching 30 (or up to 3,000 m). Each 100 m longitudinal long and ~1.85 km, on average, from the coast and; | √ |

| . Gillnets permanence time in water: 24-48 h | |

| Where: n (quantitative), ±SD (Standard Deviation), m (meters), GT (Gross Tonnage), T ("times") and, h (hours), and; | |

| *Interministerial Normative Instruction MPA/MMA nº 12 (Art. 2, IV, of NI 12/2012), of 08/22/2012 and MPA/MMA Ordinance | |

| nº 04, of 05/14/2015 (MPF, 2017). | |

| PRODUCTIVITY PARAMETERS-P | |||||||||

| GROUP/SPECIES | Tmax | Lmax | K | M | L₅₀ | RC | Fec. | Tlevel | SOURCES |

| Sharks | |||||||||

| Carcharhinus brevipinna (Müller & Henle, 1839) (Nrd) | 16.30 | 208.00 | 0.21 | 0.48 | 180.00 | Biennial | 9.00 | 4.20 | Tavares et al. (2024); ** |

| Carcharhinus falciformis (Müller & Henle 1839) (Nrd) | 27.20 | 272.00 | 0.10 | 0.18 | 207.50 | Biennial | 11.70 | 5.48 | Estupiñán-Montaño et al. (2017) |

| Santander-Neto et al. (2021); ** | |||||||||

| Carcharhinus limbatus (Müller & Henle, 1839) | 14.40 (Nrd) | 199.40 (Nrd) | 0.24 (Nrd) | 0.40 (Nrd) | 149.30 (Nrd) | Biennial | 5.50 (Nrd) | 4.30 | Bornatowski et al. (2014) |

| Tavares et al. (2024); ** | |||||||||

| Carcharhinus obscurus (LeSueur, 1818) | 45.00 (Nrd) | 371.00 (Nrd) | 0.04 (Nrd) | 0.90 (Nrd) | 284.00 (Nrd) | Biennial-Triennial | 8.07 (Nrd) | 4.30 | Cortés (2000) |

| Romine et al. (2009) | |||||||||

| Bornatowski et al. (2014); ** | |||||||||

| Rhizoprionodon lalandii (Müller & Henle 1839) | 6.00 (Nrd) | 80.00 | 0.30 (Nrd) | 0.35 (Nrd)* | 62.10 | Annual | 3.50 | 4.28 | Ferreira (1988) |

| Motta et al. (2007) | |||||||||

| Andrade et al. (2008) | |||||||||

| Lessa et al. (2009); ** | |||||||||

| Rhizoprionodon porosus (Poey, 1861) | 5.00 (Nrd) | 115.00 | 0.17 (Nrd) | 0.35 (Nrd) | 85.00 | Annual | 3.00 | 4.00 | Ferreira (1988) |

| Lessa et al. (2009) | |||||||||

| Mattos and Maynou (2009) | |||||||||

| Silva et al. (2023); ** | |||||||||

| Galeocerdo cuvier (Péron & LeSueur, 1822) | 13.50 (Nrd) | 393.00 | 0.25 (Nrd) | 0.36 | 310.00 (Nrd) | Biennial | 32.60 (Nrd) | 4.40 | Whitney and Crow (2007) |

| Driggers et al. (2008) | |||||||||

| Bornatowski et al. (2014) | |||||||||

| Aximoff et al. (2022) | |||||||||

| Santana da Silva et al. (2024); ** | |||||||||

| Notorynchus cepedianus (Perón, 1807) | 32.00 (Nrd) | 300.00 | 0.11 (Nrd) | 0.51 (Nrd) | 242.00 | Annual | 86.70 (Nrd) | 4.43 (Nrd) | Cortés (2000) |

| Lucifora et al. (2005) | |||||||||

| Barnett and Braccini (2019) | |||||||||

| Lewis et al. (2020) | |||||||||

| Lopes et al. (2021) | |||||||||

| Funes et al. (2023); ** | |||||||||

| Isurus oxyrinchus (Rafinesque, 1810) | 23.00 | 330.00 | 0.04 | 0.15 (Nrd) | 278.00 (Nrd) | Triennial | 11.50 | 4.38 | Costa et al. (1996) |

| Bishop et al. (2006) | |||||||||

| Doño et al. (2015) | |||||||||

| Barreto et al. (2016) | |||||||||

| Cabanillas-Torpoco et al. (2024); ** | |||||||||

| Sphyrna lewini (Griffith & Smith, 1834) | 31.50 | 344.00 | 0.05 | 0.13 | 240.00 (Nrd) | Annual | 11.50 (Nrd) | 4.44 | Hazin et al. (2001) |

| Kotas (2004) | |||||||||

| Galina and Vooren (2005) | |||||||||

| Vooren et al. (2005) | |||||||||

| Kotas et al. (2011); ** | |||||||||

| Sphyrna zygaena (Linnaeus, 1758) | 18.00 (Nrd) | 226.00 (Nrd) | 0.07 | 0.13 (Nrd) | 198.00 (Nrd) | Biennial | 35.00 | 4.30 | Vooren et al. (2005) |

| Coelho et al. (2011) | |||||||||

| CMFRI (2016) | |||||||||

| Bezerra et al. (2017) | |||||||||

| Huynh and Tsai (2023); ** | |||||||||

| Squalus albicaudus Viana, Carvalho & Gomes, 2016* | 32.00 (Nrd) | 89.00 (Nrd) | 0.20 | 0.34 | 59.00 (Nrd) | Annual | 4.50 (Nrd) | 4.17 | Compagno (1984) |

| Pajuelo et al. (2011) | |||||||||

| Viana et al. (2016); ** | |||||||||

| Squatina argentina (Marini, 1930) (Nrd) | 46.50 | 138.00 | 0.20* | 0.27* | 70.00 | Biennial-Triennial | 9.00 | 4.39* | Silva (1996) |

| Cortés (2000) | |||||||||

| Vooren and Klippel (2005) | |||||||||

| Cuevas et al. (2020); ** | |||||||||

| Squatina guggenheim Marini, 1936 | 12.00 | 95.50 | 0.27 (Nrd) | 0.36 | 72.00 (Nrd) | Biennial | 7.00 (Nrd) | 4.39 | Silva (1996) |

| Vieira (1996) | |||||||||

| Sunyé and Vooren (1997) | |||||||||

| Vögler et al. (2003) | |||||||||

| Vooren and Klippel (2005) | |||||||||

| Cardoso and Haimovici (2014) | |||||||||

| Della-Fina et al. (2020); ** | |||||||||

| Squatina occulta (Vooren & Silva, 1991) | 21.00 | 125.00 | 0.13 (Nrd) | 0.19 | 110.00 (Nrd) | Biennial | 10.00 | 4.39* | Silva (1996) |

| Vieira (1996) | |||||||||

| Vooren and Klippel (2005) | |||||||||

| Cardoso and Haimovici (2014) | |||||||||

| Della-Fina et al. (2020); ** | |||||||||

| Mustelus canis (Mitchell, 1815) (Nrd) | 11.90 | 132.00 | 0.29 | 0.49 | 102.00 | Annual | 12.00 | 3.60 | Tavares et al. (2024); ** |

| Rays | |||||||||

| Atlantoraja castelnaui (Ribeiro, 1907) | 29.00 | 116.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 | 105.00 | Annual | 5.00 | 4.50 | Casarini (2006) |

| Oddone and Amorim (2007) | |||||||||

| Oddone et al. (2008) | |||||||||

| Silva et al. (2020a) | |||||||||

| Silva et al. (2020b); ** | |||||||||

| Sympterygia acuta Garman, 1877 | 40.50 | 62.00 | 0.12 (Nrd)* | 0.05 | 44.70 (Nrd) | Annual | 52.00 (Nrd) | 3.87 (Nrd) | Basallo and Oddone (2014) |

| Hozbor and Massa (2015) | |||||||||

| Mabragaña et al. (2015) | |||||||||

| Barbinil and Lucifora (2016) | |||||||||

| Pollom et al. (2020); ** | |||||||||

| Bathytoshia centroura (Mitchill, 1815) (Nrd) | 11.00* | 300.00 | 0.28* | 0.48* | 116.50 | Annual | 3.00 | 3.62* | Jacobsen and Bennett (2013); ** |

| Dasyatis hypostigma Santos & Carvalho, 2004 | 11.00 | 58.00 | 0.29 | 0.41 | 49.70 | Annual | 2.00 | 3.70 | Santos and Carvalho (2004) |

| Ribeiro et al. (2006) | |||||||||

| Torres (2024); ** | |||||||||

| Hypanus berthalutzae Petean, Naylor & Lima, 2020 (Nrd) | 14.00* | 68.00 | 0.11* | 0.20* | 67.10* | Annual | 2.50* | 3.62* | Jacobsen and Bennett (2013); ** |

| Hypanus guttatus (Bloch & Schneider, 1801) (Nrd) | 14.00 | 166.60 | 0.11 | 0.20 | 67.10 | Annual | 2.50* | 3.60 | Da Silva et al. (2018) |

| Gianeti et al. (2019) | |||||||||

| Oliveira et al. (2020) | |||||||||

| Tavares et al. (2024); ** | |||||||||

| Gymnura altavela (Linnaeus, 1758) | 18.00 (Nrd) | 143.00 | 0.12 | 0.24 | 71.70 | Annual | 5.50 | 3.91 | Bauchot (1987) |

| Gonçalves-Silva and Vianna (2018) | |||||||||

| Parsons et al. (2018); ** | |||||||||

| Myliobatis freminvillei LeSueur, 1824 (Nrd) | 23.00* | 129.00 | 0.12* | 0.21* | 65.00 | Annual | 4.50* | 3.37* | Jacobsen and Bennett (2013); ** |

| Myliobatis goodei Garman, 1885 (Nrd) | 23.00 | 115.00 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 68.30 | Annual | 4.50 | 3.20 | Molina and Cazorla (2015) |

| Araújo et al. (2016); ** | |||||||||

| Narcine brasiliensis (Olfers, 1831) | 22.55 | 47.00 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 31.89 | Annual | 9.50 (Nrd) | 3.66 (Nrd)* | Rudlow (1989) |

| Jacobsen and Bennett (2013) | |||||||||

| Rolim et al. (2015) | |||||||||

| Rolim et al. (2020); ** | |||||||||

| Pseudobatos horkelii (Müller & Henle, 1841) | 8.00 | 138.00 | 0.18 | 0.41 | 79.60 | Annual | 8.00 (Nrd) | 3.83 | Lessa et al. (1986) |

| Caltabellotta (2014) | |||||||||

| Martins et al. (2017) | |||||||||

| Caltabellotta et al. (2019); ** | |||||||||

| Pseudobatos percellens (Walbaum, 1792) | 11.00 | 76.20 (Nrd) | 0.16 | 0.38 | 58.30 | Annual | 7.50 | 3.83* | Rocha and Gadig (2013) |

| Caltabellotta (2014) | |||||||||

| Tagliafico et al. (2017) | |||||||||

| Caltabellotta et al. (2019); ** | |||||||||

| Rhinoptera bonasus (Mitchill, 1815) | 21.00 (Nrd)* | 120.00 (Nrd) | 0.19 (Nrd)* | 0.26* | 65.30 (Nrd) | Annual | 3.00 (Nrd) | 3.43 (Nrd)* | Nerr and Thompson (2005) |

| Pérez-Jiménez (2011) | |||||||||

| Fisher et al. (2013) | |||||||||

| Jacobsen and Bennett (2013) | |||||||||

| Jones and Driggers (2015); ** | |||||||||

| Rhinoptera brasiliensis Müller, 1836 | 21.00 (Nrd)* | 94.00 | 0.19 (Nrd)* | 0.26 | 65.30 (Nrd)* | Annual | 1.00 | 3.49 (Nrd)* | Gómez-Canchong et al. (2004) |

| Domingues et al. (2009) | |||||||||

| Fisher et al. (2013); ** | |||||||||

| Zapteryx brevirostris (Müller & Henle 1839) | 10.00 (Nrd) | 56.00 (Nrd) | 0.22 | 0.43 | 42.30 | Triennial | 3.75 | 3.55 | Batista (1991) |

| Caltabellotta (2014) | |||||||||

| Carmo (2015) | |||||||||

| Carmo et al. (2018) | |||||||||

| Caltabellotta et al. (2019); ** | |||||||||

| Where: (Nrd), non-regional data (reported outside of the Southeastern Brazilian Bight - SBB), values in bold are estimated or from FishBase, data compiled from congeneric species*, and; | |||||||||

| Sources: "Supplementary dataset." and "Supplementary Information (SI).** at the Supplementary Materials - S1. | |||||||||

| PRODUCTIVITY ATTRIBUTES | DEFINITION | HIGH (3) | MEDIUM (2) | LOW (1) |

| Maximum age (Tmax, years) | Maximum observed age reported | <11.90 | 11.90-27.20 | >27.20 |

| Maximum size (Lmax, cm) | Maximum Total Length (TL) observed or Fork Length (FL) and Disc Diametric (DD) reported | <89.00 | 89.00-226.00 | >226.00 |

| von Bertalanffy's growth coefficient (K, cm year¯¹) | How rapidly an elasmobranch reaches its maximum size | >0.22 | 0.11-0.22 | <0.11 |

| Esteemed natural mortality (M, year¯¹) | Instantaneous natural mortality rate | >0.41 | 0.20-0.41 | <0.20 |

| Length at maturity (L₅₀, cm) | Length at which 50.0% of the individuals attain gonadal maturity for the first time | <65.00 | 65.00-180.00 | >180.00 |

| Reproductive Cycle (RC, periodicity) | Reproductive periodicity (or time frequency) | Biannual | Annual | Biennial-Triennial |

| Fecundity (Fec., mid-point of the number of oocytes or embryos) | Mid-point of the reported range of the number of oocytes (or embryos) per individual | >11.50 | 3.50-11.50 | <3.50 |

| Trophic level (Tlevel, no unit) | Species position in the food web | <3.62 | 3.62-4.39 | >4.39 |

| SUSCEPTIBILITY ATTRIBUTES | DEFINITION | LOW (1) | MEDIUM (2) | HIGH (3) |

| Vertical overlap (VO) | Location of the stock within the water column (i.e., demersal versus pelagic) in relation to the fishing gear |

<25% of the stock occurs at the depths of the fishery | ≥25% and ≤50% of the stock occurs at the depths of the fishery | >50% of the stock occurs at the depths of the fishery |

| Extent of geographic overlap between the | Low probability that an organism encounters a | Medium probability that an organism encounters a | High probability that an organism encounters a | |

| Areal overlap (or Encounterability - E) | known distribution of the stock and that of | fishing gear (e.g., a species of benthic habits caught | fishing gear (e.g., a species of pelagic habits, mainly on the surface | fishing gear (e.g., a species of bento-pelagic habits, caught |

| the fishery | with surface gillnet) | caught with bottom gillnet) | with gillnets) | |

| The ability of the fishing gear to captutre fish | No morphological characteristics or habits | Has few characteristics and habits | Has morphological characteristics and habits | |

| Morphology affecting capture (or Selectivity - S) | based on their morphological characteristics (e.g., body shape, spiny versus soft rayed fins, etc.) | that influence catchability (Low selectivity of the gillnet) | that influence catchability (Moderate selectivity of the gillnet) | that influence catchability (High selectivity of the gillnet) |

| Fishing rate in relation to esteemed natural mortality (M) | Fishing pressure (direct and/or indirect) | 0.00-0.50 | 0.51-0.99 | 1.00 |

| Food items | Forging site versus fishing ground | Spatial distribution of the prey does not overlap | Spatial distribution of prey partially overlapping | Spatial distribution of the prey overlaps completely |

| with the area of action of the fishing mechanism | with the fishing mechanism's area of operation | with the area of action of the fishing mechanism | ||

| Seasonal migrations | Increase or decrease in fishery-species interaction | Reduces overlap with fishing | Does not substantially affect the overlap with fishing | Increases overlap with fishing |

| when any seasonal migrations occur | ||||

| Schooling/aggregation/geographic concentration and behavioral responses | Aggregations of organisms for feeding or reproduction | Reduces the catchability of the fishing gear | Does not substantially affect the catchability of the fishing gear | Increases the catchability of the fishing gear |

| Fishery impact | Direct and/or indirect impacts to essential fish habitat | Adverse effects absent, minimal or temporary | Adverse effects more than minimal or temporary but are mitigated | Adverse effects more than minimal or temporary and are not mitigated |

| Valued or desired of the fishery | Value of fish to the final consumer | Stock is not highly valued or desired by the fishery (low or no price) | Stock is moderately valued or desired by the fishery (medium price) | Stock is highly valued or desired by the fishery (high price) |

| Management strategy | Current fisheries legislation | Targeted stocks have catch limits and proactive accountability measures; Non-target stocks are closely monitored | Targeted stocks have catch limits and reactive accountability measures | Targeted stocks do not have catch limits or accountability measures; Non-target stocks are not closely monitored |

| Immatures caugth (%) | Capture of juveniles/species (%) in relation to the selectivity | 0.0-30.0% | 31.0-60.0% | 61.0-100.0% |

| off the fishing gear in the catches sampled | ||||

| IUCN status | Conservation status | NE-DD | LC-NT | VU-EN-CR |

| GROUP/SPECIES | iD SPECIES | PRODUCTIVITY | PRODUCTIVITY | SUSCEPTIBILITY | SUSCEPTIBILITY | OVERALL | VULNERABILITY | RISK |

| DATA QUALITY | DATA QUALITY | DATA QUALITY | ||||||

| Sharks | ||||||||

| Sphyrna lewini | Slew | 1.3 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 2.6 | High |

| Sphyrna zygaena | Szyg | 1.6 | 5.3 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 2.3 | High |

| Isurus oxyrinchus | Ioxy | 1.4 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 2.0 | High |

| Squatina occulta | Socc | 1.8 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 1.9 | Moderate |

| Rhizoprionodon porosus | Rpor | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.9 | Moderate |

| Carcharhinus falciformis | Cfal | 1.4 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 1.9 | Moderate |

| Carcharhinus obscurus | Cobs | 1.5 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 1.8 | Moderate |

| Squatina argentina | Sarg | 1.8 | 6.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 1.8 | Moderate |

| Rhizoprionodon lalandii | Rlal | 2.5 | 4.8 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 1.7 | Low |

| Notorynchus cepedianus | Ncep | 1.8 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.7 | Low |

| Galeocerdo cuvier | Gcuv | 1.8 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.7 | Low |

| Squatina guggenheim | Sgug | 2.0 | 5.3 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.3 | 1.7 | Low |

| Carcharhinus limbatus | Clim | 2.0 | 5.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.4 | 1.4 | Low |

| Carcharhinus brevipinna | Cbre | 2.0 | 6.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 1.4 | Low |

| Squalus albicaudus | Salb | 2.0 | 6.0 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 1.2 | Low |

| Mustelus canis | Mcan | 2.5 | 6.3 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 1.0 | Low |

| Rays | ||||||||

| Atlantoraja castelnaui | Acas | 1.5 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 2.3 | High |

| Pseudobatos horkelii | Phor | 2.1 | 4.3 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 2.0 | High |

| Dasyatis hypostigma | Dhyp | 2.4 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 1.9 | Moderate |

| Pseudobatos percellens | Pper | 2.4 | 4.0 | 2.8 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 | Moderate |

| Hypanus guttatus | Hgut | 2.0 | 6.0 | 2.4 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 1.7 | Low |

| Rhinoptera brasiliensis | Rbra | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.6 | Low |

| Rhinoptera bonasus | Rbon | 2.0 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 1.5 | Low |

| Gymnura altavela | Galt | 2.0 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.4 | Low |

| Hypanus berthalutzae | Hber | 2.0 | 6.3 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 1.4 | Low |

| Sympterygia acuta | Sacu | 2.1 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.2 | 1.3 | Low |

| Myliobatis goodei | Mgoo | 2.1 | 6.0 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 1.3 | Low |

| Myliobatis freminvillei | Mfre | 2.1 | 6.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 1.3 | Low |

| Bathytoshia centroura | Bcen | 2.1 | 6.8 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.9 | 1.3 | Low |

| Narcine brasiliensis | Nbra | 2.3 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 2.8 | 1.1 | Low |

| Zapteryx brevirostris | Zbre | 2.5 | 4.8 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 1.0 | Low |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).