1. Introduction

The time series of Cuban marine finfish landings over the last 30 years shows a similar pattern to that of Hilborn and Walters’ model of fisheries development, where the total catch increases, peaks, and then decreases [

1,

2]. The Cuban fishing industry underwent an industrialization phase in the early 1960s [

3], accompanied by an increase in finfish landings until the late 1980s, after which landings fell from 29 thousand tons in 1987 to 13 thousand tons in 2015, leading regional fisheries to a critical state [

4,

5]. Although primarily operated by state enterprises, the fishery sector is mainly artisanal or small-scale, accounting for 90% of the catches nationwide [

6,

7]. However, effective management is limited due to the fishery’s data-poor status and the diverse and numerous landing sites, vessel types, fishing gears, and target species.

There are different studies explaining such a pattern. It is argued that since the 1990s, most Cuban commercial fishing resources are at high risk of overexploitation because fisheries shifted towards smaller, less valuable species, causing a decrease in both the average trophic level and the size of catches and even the collapse of several fishery resources [

4,

5,

8]. The overall decline in landings can be attributed to several factors, including the high market value of the target species, the fishing of spawning aggregations, the use of non-selective fishing gear, and the low reproductive potential (e.g., sharks) or low growth rate (e.g., many reef fishes) of many of the exploited species [

4]. Other non-fishing factors, such as habitat degradation, are also believed to have affected Cuba’s marine finfish landings [

6,

9,

10]. For example, the construction of numerous dams on rivers to create water reservoirs and the reduction in the amount of nutrients entering the environment from agricultural fertilizers have been identified as significant causes of declining fish populations [

5,

6,

11,

12]. However, these conclusions have not been empirically verified.

Specifically, the decline in finfish catch since the 1980s is attributed to a reduction in primary production due to a decline in nutrients, affecting species that feed on plankton, such as herrings. Furthermore, the construction of dams has increased the salinity of shallow water areas and brackish lagoons along the Cuban coast, where most species’ recruitment and nursery areas are found [

12,

13]. Dam-induced oligotrophication, through sediment and nutrient trapping, can also severely alter the ecological functioning of coastal waters [

14]. Mangroves are particularly susceptible to extreme salinity and sediment accretion due to lower freshwater discharge and less sediment flush [

15,

16]. The alterations in the natural coastal vegetation may have also disrupted the recruitment processes of important finfish species.

Climate variability is among the non-fishing factors that may potentially affect finfish landings. Studies in the wider Caribbean have found that changes in fishery landings composition are likely related to significant shifts in regional climate processes [

17]. Similarly, studies conducted in the Mexican Campeche Bank subarea have demonstrated that climate change and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) have significantly impacted fisheries. These studies have linked changes in sea surface temperature (SST) to declines in key fishery stocks, including the collapse of the pink shrimp fishery and the decrease in annual yields and stock abundance of the red grouper [

18,

19,

20]. In particular, the spiny lobster fishery in Cuba is affected by the cumulative, synergistic effects of human-induced impacts and changes in El Niño and tropical cyclone intensity and frequency [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Despite the well-documented impact of climate variability on marine ecosystems and fisheries [

25] and its projected effects on fisheries, mainly by altering species’ life cycles, abundance, and distribution [

26,

27], this factor’s effects on fish species remain unexplored in Cuba.

While regional trends indicate a continuous decrease, particularly in the southeast region, Cuba’s most productive fishing zone [

6], the behavior of individual species or groups of species presents a more complex picture. Notably, landings of key species like rays, herrings, and snappers show increasing trends, contradicting the regional overall declining trend [

28]. These inconsistencies underscore the complex interplay of factors other than fishing effort driving finfish populations, which remain poorly understood. It is worth noting that previous studies that have identified non-fishery factors influencing finfish landings in Cuba lack statistically validated analyses that address the interaction of these different factors, particularly in the unique ecological and economic context of Cuba’s fisheries.

We hypothesize that local and regional environmental factors may play a significant role in the finfish catch trends. Consequently, improvements in management actions could result from considering these factors. The current study aims to fill this gap by studying the temporal variations of 19 species that represent 90% of the historical finfish landings on the southeastern coast of Cuba. Through dynamic factor analysis (DFA) [

29] and considering multiple environmental factors and fishing effort, this research seeks to provide a nuanced understanding of the drivers behind the current landing trends, aiming to inform more effective management strategies and underscore the necessity for further, rigorous research in this field.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Cuba’s continental shelf is divided into four administrative fishing zones. The four coastal zones constitute relatively independent fishing areas for management purposes [

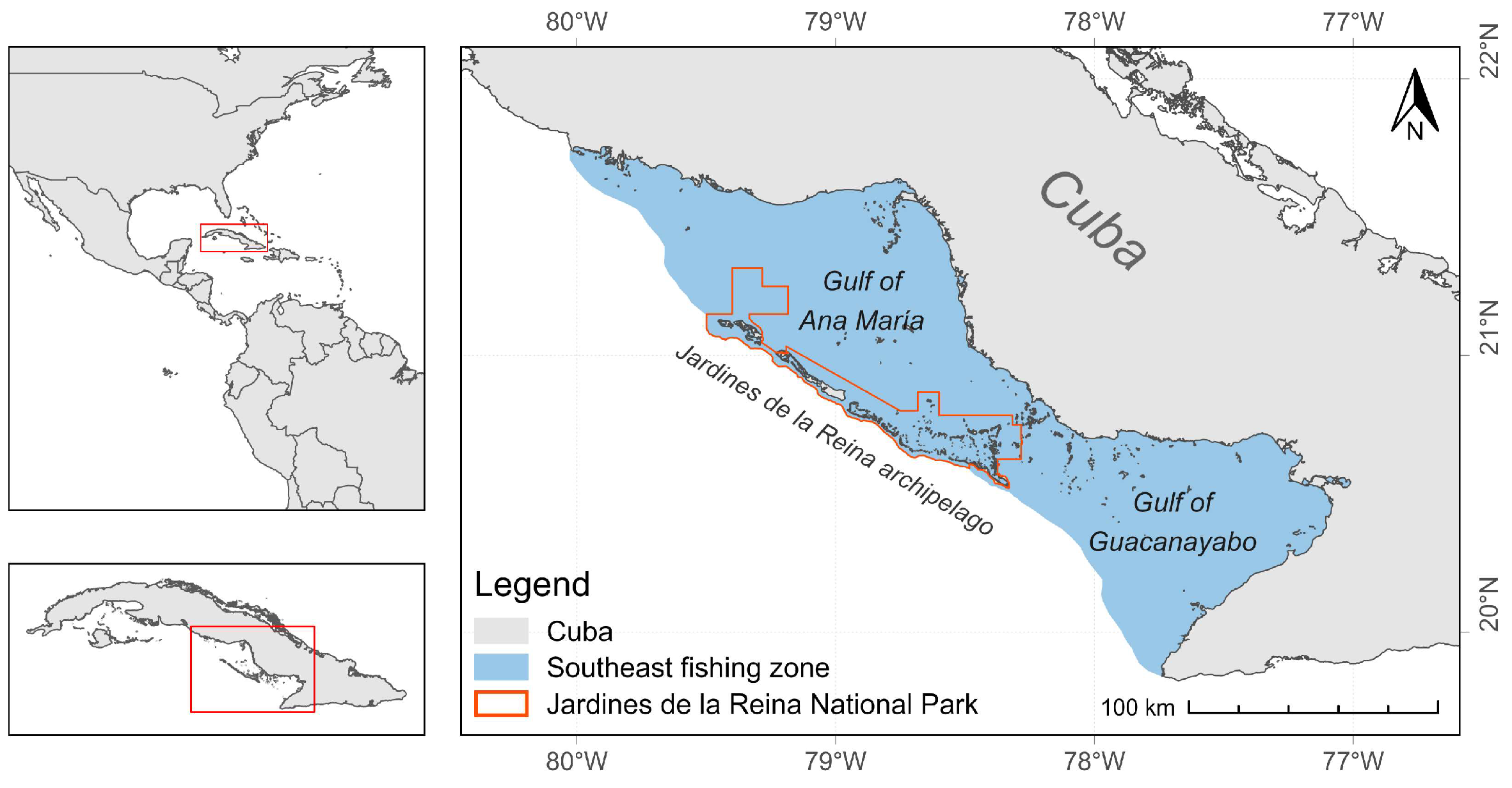

6]. This study was conducted in the most productive fishing zone, the southeastern zone (

Figure 1), which contributes 44% of the national fishing production [

6]. Covering two gulfs - Ana María and Guacanayabo - the southeastern zone is dominated by muddy marine habitats interspersed with mixed seagrasses, patch reefs, and numerous small cays surrounded by mangroves [

30]. To the north and east, the basin encompasses towns, agricultural areas, and Cuba’s longest river and largest dam. The zone limits to the south with the keys and marine ecosystems of the Jardines de la Reina National Park, one of the most important marine reserves in the Caribbean [

31]. More than 55% of the endemic species of the Caribbean coexist on its insular platform, and it is home to some of the most extensive and best-preserved mangroves, seagrasses, and reefs in the region [

28]. Fishing-related activities constitute the main sustenance for the coastal communities. However, it has been impacted by multiple stressors like overfishing, mangrove deforestation, aggressive fishing gear, reduction in the circulation of freshwater flows, and illegal fishing.

2.2. Data Collection

In Cuba, 90% of fishing is carried out by 14 state enterprises operating 705 vessels, 385 of which are between 15 and 20 meters long, mainly targeting finfish [

6]. Most Cuban fisheries, excluding shrimp fisheries, are considered artisanal or small-scale, based on various factors like boat size, tonnage, and target species [

7].

Fish landing data from 1981 and 2017 for the nine fishing ports located in the southeastern zone were obtained from the Cuban Food Industry Ministry’s Fisheries Research Center, reflecting catches solely made and landed in this area. The data comprised 70 species (

Table S1), landing port, year, and fishing effort as vessel days-at-sea. Catches in the region come mainly from seine nets, gillnets, traps, longlines, hooks, set nets (banned since 2008), and trawls (banned since 2012) [

28].

The landing data were used to construct time series of annual landings per species by summing the landings of each species over the ports. Because of changes in technology and gear efficiency over the period and unreliable reporting of fishing data, days-at-sea may not be an optimal proxy for fishing effort [

32]. Despite these limitations, in Cuba’s data-poor fisheries context, days-at-sea remains the most uniformly recorded metric, offering a continuous insight into fishing activities in the area. The minimal management interventions in finfish fisheries and the absence of significant technological advancements due to economic constraints imply that fishing practices have remained relatively stable during the study period [

6].

We compiled a database of human-related and environmental variables that correspond to the same period. We used online databases and satellite data to analyze their effect as predictors of finfish landings. These variables include climate oscillations, sea surface temperature (SST) variations, ecological conditions, agricultural impacts, and fishing effort (

Table 1, Supplementary material 1,

Figure S1). We selected variables reported in the scientific literature as significant causes of the decline in finfish landings and can impact the species’ population dynamics.

2.3. Data Analysis

We conducted exploratory analyses of the landing data to find possible patterns. We used the Hoeffding test to analyze the relationship between fishing effort and the species composition of the landings. The Hoeffding test is a non-parametric rank-based measure of association that detects more general departures from independence [

35], including non-linear associations [

36]. To further our analysis, we used dynamic factor analysis (DFA) [

29] to identify the common landings trends, a robust multivariate time series method to discern common trends across the landings data.

The DFA models the time series by decomposing them into a linear combination of shared trends, explanatory variables, a level parameter, and a stochastic component [

29]. Specifically, the mathematical formulation of our DFA model is as follows:

where

represents the observation of the

th time series at time

,

denotes the

th common trend affecting all time series,

is the factor loading on the

th time series by the

th common trend, and

signifies the noise or error term. This model is extended to incorporate explanatory variables as follows:

where

represents the values of

explanatory variables at time

, and

represents the matrix of regression coefficients. This inclusion explains how environmental variables and other relevant explanatory factors dynamically influence the species landings over time.

The analyses included only the time series of 19 species, constituting 90% of all landings, to increase the models’ convergence probability (

Table S1). Before applying the analysis, the data were log-transformed and standardized (subtracted the mean and divided by the standard deviation) to simplify the interpretation of the results. The DFA models were adjusted to incorporate environmental variables to assess their effects on individual species or species groups. Before evaluating the impact of the explanatory variables over the finfish landings, we lagged all variables from 0 (no lag) to 4 years, obtaining 67 environmental variables. We did not lag the fisheries landings data to maintain the focus on how past environmental conditions potentially impacted future landings. We detected potential collinear variables through linear correlations and Variance Inflation Factors, and we did not include multiple collinear variables in the same model. The analyses corresponded to the period 1986-2017 due to the data lagging and the lack of landing information for additional years.

DFA models included different structures in the variance-covariance matrix and scenarios where the 19 species could have 1 to 8 common trends. The best model was selected based on the Akaike Information Criteria (AICc), following the next steps for model selection:

Fit the most complex model based on the possible covariates and random factors (i.e., states or common trends).

Keep the covariates fixed and choose the number of trends (states) using AIC.

Keep the covariates and states fixed and choose the form for the variance-covariance matrix ().

Sort out the covariates while keeping the states and fixed.

A factor loading threshold of 0.2 was used to determine whether a series was associated with a common trend. All analyses were performed in R 4.3.0 [

37], the Hoeffding test with the package

correlation [

36], and the DFA with the package

MARSS [

38].

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Analysis of the Landings

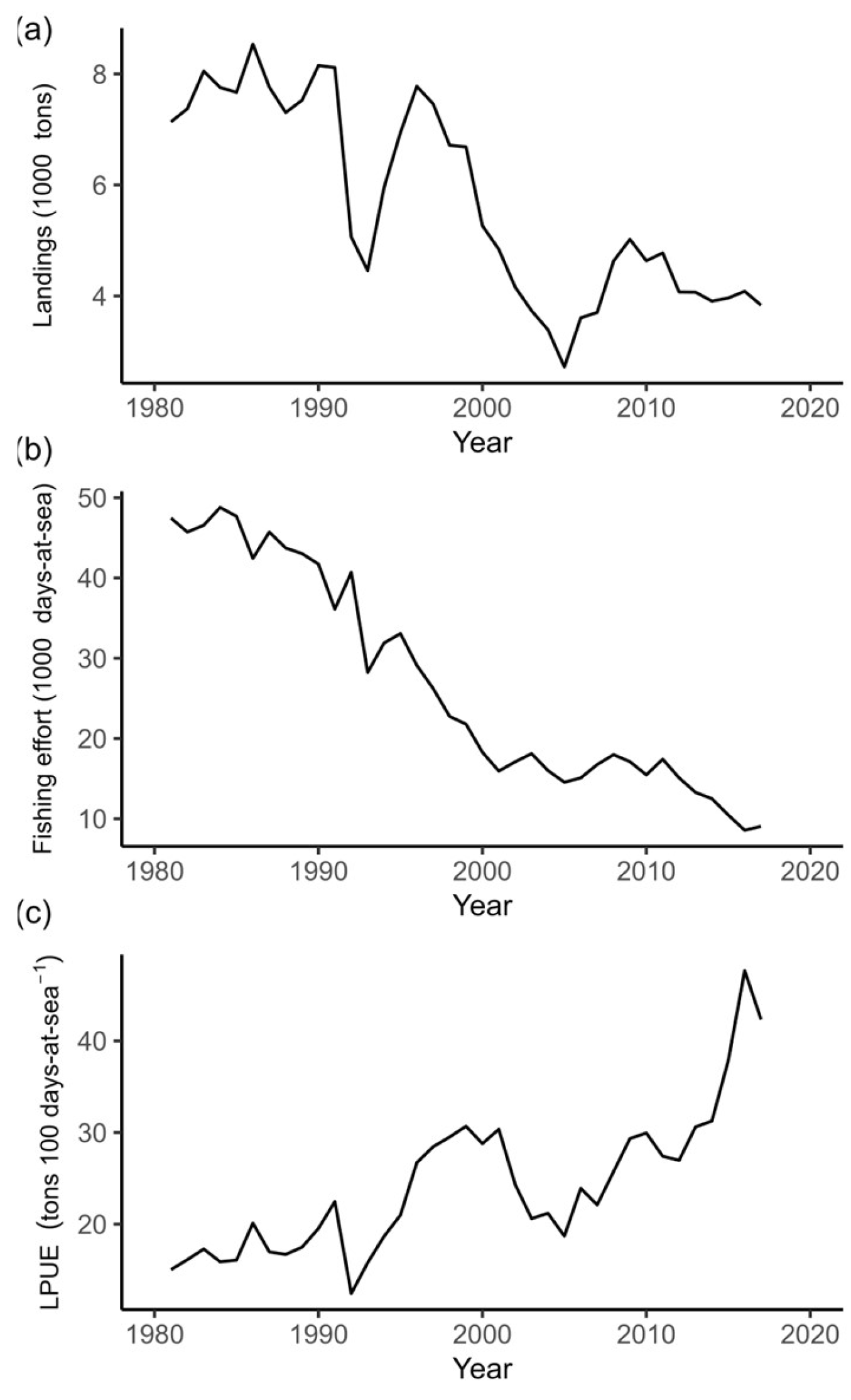

Finfish landings in the southeastern region of Cuba decreased by 46% from 1981 to 2017, with 56 out of 70 species exhibiting negative changes (

Table S1,

Figure S2a). Landings went from 7 thousand tons in 1981, at the beginning of the time series, to just under 4 thousand tons in 2017 (

Figure 2a). Likewise, fishing effort decreased by over 80%, from over 47 thousand days-at-sea in 1981 to 9 thousand in 2017 (

Figure 2b). Based on the landings and effort values, we estimated that the landings per unit of effort (LPUE) increased 2.8 times during this period (

Figure 2c). Notably, 37 out of 70 species showed positive trends in LPUE (

Table S1,

Figure S2b). Despite the decrease in fishing effort, the number of landed species remained stable over time (rounded mean: 61

2 species) (

Figure S3), and no relationship between fishing effort and the composition of the landings was found (Hoeffding test: D = -0.004, p = 0.42). The most common landed species was the Atlantic thread herring (

Opisthonema oglinum [Lesueur, 1818]), with the highest annual landings except for the years 2005 and 2007 when the rays (Rajiformes) displaced it, and in 2017 when the mojarras (Gerreidae) became the most landed species.

3.2. Trends in Landings

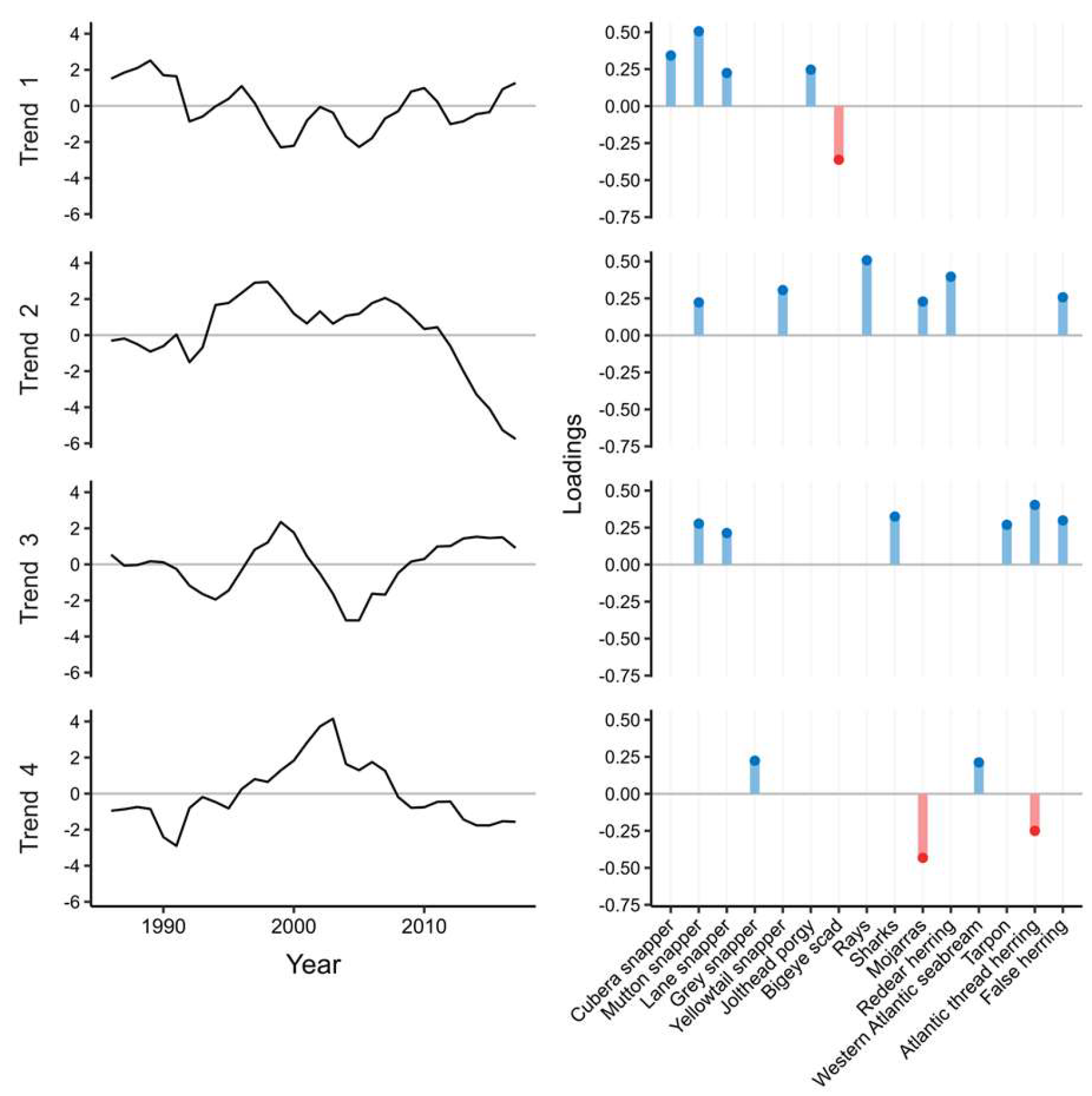

A total of 1551 models were tested to analyze common trends in the finfish landings and the explanatory variables affecting landing patterns. According to the DFA, landings on the southeastern coast of Cuba follow four common trends, driven by fishing effort and a 26-year cycle of AMO with lags of 2 and 3 years (

Table 2). All four trends describe declines in landings until the early 1990s, followed by an increase (

Figure 3). Trends 1 and 3 indicate an increase from 2005 and 2013, respectively, while trends 2 and 4 show a decrease in catches from 2003 and 2007.

The first trend mainly describes the landing patterns of the mutton snapper (Lutjanus analis [Cuvier, 1828]), cubera snapper (Lutjanus cyanopterus [Cuvier, 1828]), and bigeye scad (Selar crumenophthalmus [Bloch, 1793]) although with a negative relationship for this last species.

The second trend is mainly associated with rays and three other species, false herring (Harengula clupeola [Cuvier, 1829]), redear herring (Harengula humeralis [Cuvier, 1829]), and yellowtail snapper (Ocyurus chrysurus [Bloch, 1791]); indicating a substantial drop in landings by the end of the trend.

The third trend is positively associated with the Atlantic thread herring, sharks, false herring, and the mutton snapper, with some recovery at the end but starting to decline again.

The fourth trend describes the patterns of the grey snapper (Lutjanus griseus [Linnaeus, 1758]) and western Atlantic seabream (Archosargus rhomboidalis [Linnaeus, 1758]) and the opposite patterns of the mojarras and the Atlantic thread herring, which show mainly increased landings towards the end of the period analyzed.

Overall, our data analysis suggests that different finfish species show distinct landing patterns over the period studied, with some species experiencing declines while others show signs of recovery towards the end of the trend.

4. Discussion

4.1. Finfish Landings

A critical question in this study is whether landings or LPUE serve as reliable indices of stock abundance, and if so, under what assumptions. Unfortunately, there is a lack of data for Cuban commercial marine finfish species against which to compare catches. The only information available is historical landings of target species (1981-2017) and a single fishing effort time series. As shown in

Figure 2, there is a consistent positive correlation between total landings and fishing effort over the 37-year period, which contradicts the expected theoretical non-linear (parabolic) relationship. This discrepancy suggests that LPUE may not accurately reflect true stock abundance.

When landings and fishing effort change together consistently through all stages of a fishery’s development, it becomes difficult to discern whether changes in catch are driving changes in fishing effort, or vice versa. For example, the rapid decline in landings and effort beginning in 1987 coincided with a severe economic crisis in Cuba following the dissolution of the Soviet Union [

39]. This crisis led to fuel shortages and a shift to primarily export-oriented fishing activities [

40], suggesting that fishing effort may be the primary driver of catches.

In addition, the crisis reduced the availability of fertilizer for agricultural purposes, leading to a reduction in nutrient runoff, which is likely to affect primary production and fish stocks [

5,

11]. Conversely, a critical environmental event occurred in 2005 when Hurricane Dennis, a category 4 storm, hit the region, causing significant runoff in coastal habitats [

41,

42]. However, fishing activities resumed shortly thereafter, increasing landings of Atlantic thread herring, the main species in the study area. Such an increase in landings could indicate a positive impact of the hurricane on the Atlantic herring population despite the widespread coastal damage. These two events suggest that catches may reflect the underlying abundance of the stock and influence subsequent fishing effort.

4.2. Environmental variables Affecting Finfish Landings

The reduction in Cuban landings has also been attributed to the decrease in nutrient load in coastal areas caused by the damming of rivers and the reduction in fertilizers in agriculture [

5,

6,

11,

12]. In the 1960s, Cuban water resources were limited, and the government established a dam construction program to mitigate the intense and prolonged drought in 1961-1962 and the severe flooding caused by hurricanes [

15]. Since then, most Cuban rivers have been dammed, with a total capacity of 9 billion m

3 across 242 water reservoirs [

43]. According to Baisre [

44], cited in [

11], Cuban marine coastal fisheries depend primarily on river discharge for nutrients due to its location in the oligotrophic Caribbean Sea, lack of coastal upwelling processes, and minimal tidal range. Changes in freshwater input can affect sediment and nutrient fluxes, affecting coastal marine productivity [

17]. However, in our study, changes in the water reservoir area and the use of fertilizers in agriculture had no statistical support as plausible explanations for the landing trends.

The southeastern region appears more stable and shows fewer seasonal variations than Cuba’s other fishing zones, mainly because it is more profound and receives moderate river drainage [

13,

45]. Additionally, it is possible that the domestic and industrial effluents partially compensate for the reduced river flow and decreased nutrient supply [

15]. Nutrient imports may occur through a) groundwater contributions facilitated by the limestone rocks that make up the soils, b) enhanced rainwater drainage given by the orographic slopes along the longitudinal axis of the main island, c) the increase of untreated or partially treated urban and industrial effluents, d) the increase in fertilizer and irrigation in rice paddies especially in estuarine areas like the Cauto River swamp located in the basin of the current study area, and e) the runoff of swamps [

15]. These factors could explain why there was no evidence of lower inorganic nitrogen and phosphate concentrations in coastal waters after comparing 1972-1973 and 1990-2000 [

15]. This may be why plankton-feeder species, like the Atlantic thread herring, dominated most of the composition of the landings between 1981 and 2017.

This is the first time AMO has been linked to Cuban finfish fisheries behavior. Alheit et al. [

46] noted that the AMO might be a proxy for several complex processes that influence ecosystem dynamics. Karnauskas et al. [

17] also suggest that the AMO affects the Gulf of Mexico through various factors, including temperature changes, current patterns, mixed layer depth, biogeochemical cycling patterns, and indirect effects on different trophic levels. Every 13 years, the North Atlantic ocean-atmospheric system relaxes and intensifies for the next 13 years. When the system changes, it coincides with weak/strong winds and upwellings, lowering/raising of the thermocline, and subsequent changes in the primary production. The AMO influences the landings through atmospheric drivers and weather effects on the regional and local hydrology, habitat conditions, and the amount and timing of zooplankton prey production.

The changes in the West Atlantic ocean-atmospheric conditions are reflected on the southeastern coast of Cuba fisheries after 2-3 years. The lagged effect could coincide with the life cycle of some of the main landed species, like herrings and mojarras. In these short-lived species, annual recruitment can represent a substantial component of the stock [

47]. Hydrologic changes may affect eggs and larvae retention in the coastal areas enriched by increased runoff and thickening of the mixing layer driven by winds. These changes are mainly noticed around the second year when the species reach a commercial size and their age of first maturity [

48]. However, the effects could also be adverse since the increased precipitation and winds could lead to changes in water salinity and advective movements that could displace the eggs and larvae. The causal relationships between environmental variables, the species’ life cycle, and the subsequent fish abundance can be contradictory [

32,

47].

4.3. Management Considerations

The current fishing crisis in Cuba has prompted suggestions to reduce fishing effort as a solution. However, this approach has increased informal and illegal fishing practices as fishers struggle to supplement their income [

39]. Therefore, a comprehensive management approach that considers estimating both informal and illegal fishing effort and landings is necessary. Furthermore, it is essential to consider the impacts of climate change and extreme events on the fishing industry.

Cuba has been working toward ecosystem-based fisheries management (EBFM) since the 1990s. This approach recognizes the need to understand how shifts in ecosystems’ natural and human components impact ecosystem function and scale. The state has declared marine protected areas, special use areas, and integrated management areas [

49]. Educational workshops and social programs have been developed to promote sustainable fishing practices [

50,

51]. Vulnerability analyses have been carried out on species of economic interest [

6], and projections have been made under different management strategies [

52]. The recent approval of the first Cuban fisheries law in 2020 is a significant milestone in this regard, which aims to establish fisheries management under the principles of conservation, sustainable use, the precautionary approach, and the implementation of scientific-technological criteria.

It is important to note that regional oceanographic events can impact local Cuban fisheries, and therefore, management strategies must be tailored to the specific ecosystem state. Due to the multispecies nature of Cuban fisheries [

53], single-species management may not be sufficient to recover overexploited populations [

6]. However, EBFM may only achieve satisfactory results if the data scarcity issue is addressed. Additionally, incorporating economic viability measures such as the Fishery Essentiality index [

54] and bioeconomic models [

55] can complement EBFM by accounting for the economic drivers behind fishers’ behavior, including informal and illegal fishing efforts.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the contribution of fishing effort and environmental variables to the current trend of multispecies finfish landings on the southeastern coast of Cuba. Our findings indicate that the decline in finfish landings on the southeast coast of Cuba over the last 30 years is not solely attributed to overfishing and the reduction in nutrient imports in coastal areas. Instead, we found that the decrease in fishing effort and changes in a 26-year Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation cycle were the main drivers of the landings in the region. These findings have important implications for fisheries management in the area, highlighting the need to include informal and illegal fishing effort and landings, and the importance of performing stock assessments to not rely on the assumption that landings serve as a proxy for stock abundance. Moreover, our study underscores the need to recognize the effect of changing environmental patterns on fishery landings and consider reference points estimated ad hoc for each ecosystem state to inform specific management actions that match the stock dynamics and the ecosystem states.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Overview of finfish landings in Southeastern Cuba (1981-2017), highlighting the dominant species (90 % of historic landings) with bold and assessing trends in landing volumes and landings per unit of effort (LPUE); Supplementary material 1: Processing of human-related and environmental variables; Figure S1: Covariates added to the dynamic factor analyses (DFA); Figure S2: Changes in species landings (a) and landings per unit of effort (LPUE) (b), between 1981 and 2017 on the southeastern coast of Cuba; Figure S3: Relationship between fishing effort and the composition of the landings between 1981 and 2017 on the southeastern coast of Cuba. Reference [

56] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.O.E., Y.R.C., F.P.A., F.A.S., M.J.Z.R., K.K., and P.d.M.L.; Methodology, Y.O.E., Y.R.C., F.P.A., F.A.S., M.J.Z.R., K.K., and P.d.M.L.; Software, Y.O.E.; Validation, Y.O.E. and P.d.M.L; Formal Analysis, Y.O.E. and Y.R.C.; Investigation, Y.O.E., Y.R.C., and F.P.A.; Resources, Y.O.E. and P.d.M.L.; Data Curation, Y.O.E and Y.R.C; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Y.O.E. and Y.R.C.; Writing – Review & Editing, Y.O.E., Y.R.C., F.P.A., F.A.S., M.J.Z.R., K.K., and P.d.M.L.; Visualization, Y.O.E., F.P.A., F.A.S., M.J.Z.R., K.K., and P.d.M.L.; Supervision, K.K. and P.d.M.L.; Project Administration, Y.O.E; Funding Acquisition, Y.O.E., F.P.A., and P.d.M.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by scholarships from CONACyT and BEIFI-IPN and funding from the NGO Idea Wild.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Fisheries Research (Centro de Investigaciones Pesqueras) of Cuba for providing the data. We also thank CONACyT and BEIFI-IPN for the scholarships provided and the NGOs Idea Wild and Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) for all the support. FAS, MJZR, and PdML, thank COFAA and EDI from Instituto Politécnico Nacional.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hilborn, R.; Walters, C.J. Quantitative Fisheries Stock Assessment: Choice Dynamics and Uncertainty; Chapman and Hall: New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Karr, K.A.; Miller, V.; Coronado, E.; Olivares-Bañuelos, N.C.; Rosales, M.; Naretto, J.; Hiriart-Bertrand, L.; Vargas-Fernández, C.; Alzugaray, R.; Puga, R.; et al. Identifying Pathways for Climate-Resilient Multispecies Fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 721883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doyon, S. Fishing for the Revolution: Transformations and Adaptations in Cuban Fisheries. MAST 2007, 6, 83–108. [Google Scholar]

- Baisre, J.A. Historical Development of Cuban Fisheries: Why We Need an Integrated Approach to Fisheries Management? Proc. Gulf Caribb. Fish. Inst. 2007, 59, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Baisre, J.A. An Overview of Cuban Commercial Marine Fisheries: The Last 80 Years. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2018, 94, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, R.; Valle, S.; Kritzer, J.P.; Delgado, G.; Estela de León, M.; Giménez, E.; Ramos, I.; Moreno, O.; Karr, K.A. Vulnerability of Nearshore Tropical Finfish in Cuba: Implications for Scientific and Management Planning. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2018, 94, 377–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valle, S.V.; Sosa, M.; Puga, R.; Font, L.; Duthit, R. Coastal Fisheries of Cuba. In Coastal fisheries of Latin America and the Caribbean; FAO fisheries and aquaculture technical paper; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Roma, Italia, 2011; ISBN 978-92-5-106722-2. [Google Scholar]

- Baisre, J.A. Chronicle of Cuban Marine Fisheries, 1935-1995: Trend Analysis and Fisheries Potential; FAO Fisheries Technical Paper, 2000.

- Claro, R.; Sadovy, Y.; Lindeman, K.C.; García-Cagide, A.R. Historical Analysis of Cuban Commercial Fishing Effort and the Effects of Management Interventions on Important Reef Fishes from 1960–2005. Fish. Res. 2009, 99, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzugaray, R.; Puga, R.; Valle, S.; Hernández-Betancourt, A.; Boné, E.; Kleisner, K.; Manguin, T.; Karr, K.A. Situación actual y proyecciones futuras de las pesquerías multiespecíficas de peces en la región suroriental de Cuba: Situação atual e projecções futuras da pesca de peixes multiespecíficos na região sudeste de Cuba. Braz. J. Anim. Environ. Res. 2023, 6, 1950–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baisre, J.A. Assessment of Nitrogen Flows into the Cuban Landscape. Biogeochemistry 2006, 79, 91–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baisre, J.A.; Arboleya, Z. Going Against the Flow: Effects of River Damming in Cuban Fisheries. Fish. Res. 2006, 81, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, R.; Reshetnikov, Y.S.; Alcolado, P. Physical Attributes of Coastal Cuba. In Ecology of the marine fishes of Cuba; Claro, R., Lindeman, K.C., Parenti, L.R., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, 2001; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Winton, R.S.; Calamita, E.; Wehrli, B. Reviews and Syntheses: Dams, Water Quality and Tropical Reservoir Stratification. Biogeosciences 2019, 16, 1657–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lajonchère, L.; Laíz-Averhoff, O.; Perigó-Arnaud, E. River Dam Effects on Cuban Fisheries and Aquaculture Development with Recommendations for Mitigation. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2018, 17, 491–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, W.E.; Johannes, R.E. The Response of Mangroves to Man-Induced Environmental Stress. In Tropical Marine Pollution; Wood, E.J.F., Johannes, R.E., Eds.; Elsevier Oceanography Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Karnauskas, M.; Schirripa, M.J.; Craig, J.K.; Cook, G.S.; Kelble, C.R.; Agar, J.J.; Black, B.A.; Enfield, D.B.; Lindo-Atichati, D.; Muhling, B.A.; et al. Evidence of Climate-Driven Ecosystem Reorganization in the Gulf of Mexico. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 2554–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arreguín-Sánchez, F.; del Monte Luna, P.; Zetina-Rejón, M.J.; Tripp-Valdez, A.; Albañez-Lucero, M.O.; Mónica Ruiz-Barreiro, T. Building an Ecosystems-Type Fisheries Management Approach for the Campeche Bank, Subarea in the Gulf of Mexico Large Marine Ecosystem. Environ. Dev. 2017, 22, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arreguín-Sánchez, F. Cambio Climático y El Colapso de La Pesquería de Camarón Rosado (Farfantepenaeus duorarum) de La Sonda de Campeche. In Cambio Climático en México un Enfoque Costero-Marino; Rivera-Arriaga, E., Azuz-Adeath, I., Alpuche-Gual, L., Villalobo-Zapata, G.J., Eds.; Universidad Autónoma de Campeche Cetys-Universidad, Gobierno del Estado de Campeche, 2010; pp. 399–410.

- Arreguín-Sánchez, F.; del Monte-Luna, P.; Zetina-Rejón, M.J. Climate Change Effects on Aquatic Ecosystems and the Challenge for Fishery Management: Pink Shrimp of the Southern Gulf of Mexico. Fisheries 2015, 40, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, B.; Puga, R. Influencia Del Fenómeno El Niño En La Región Occidental de Cuba y Su Impacto En La Pesquería de Langosta (Panulirus argus) Del Golfo de Batabanó. Invest. Mar. 1995, 23, 03–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, R.; Piñeiro, R.; Alzugaray, R.; Cobas, L.S.; León, M.E.D.; Morales, O. Integrating Anthropogenic and Climatic Factors in the Assessment of the Caribbean Spiny Lobster (Panulirus argus) in Cuba: Implications for Fishery Management. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2013, 3, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puga, R.; Piñeiro, R.; Cobas, S.; De León, M.E.; Capetillo, N.; Alzugaray, R. La Pesquería de La Langosta Espinosa, Conectividad y Cambio Climático En Cuba. La biodiversidad en ecosistemas marinos y costeros del litoral de Iberoamérica y el cambio climático: I. Memorias del Primer Taller de la Red CYTED BIODIVMAR, La Habana.

- Alzugaray, R.; Puga, R.; Piñeiro, R.; de León, M.E.; Cobas, L.S.; Morales, O. The Caribbean Spiny Lobster (Panulirus argus) Fishery in Cuba: Current Status, Illegal Fishing, and Environmental Variability. Bull. Mar. Sci. 2018, 94, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U.R.; Cheung, W.W.; Lam, V.W.; Pauly, D.; Herrick, S. Climate Change Impacts on the Biophysics and Economics of World Fisheries. Nat. Clim. Change 2011, 1, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, A.L.; Low, P.J.; Ellis, J.R.; Reynolds, J.D. Climate Change and Distribution Shifts in Marine Fishes. Science 2005, 308, 1912–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios-Abrantes, J.; Frölicher, T.L.; Reygondeau, G.; Sumaila, U.R.; Tagliabue, A.; Wabnitz, C.C.C.; Cheung, W.W.L. Timing and Magnitude of Climate-Driven Range Shifts in Transboundary Fish Stocks Challenge Their Management. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2022, 28, 2312–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Hurtado, E.; Ramos-Díaz, I.; Valle, S. Análisis de La Productividad Pesquera de La Plataforma Suroriental de Cuba. Rev. Cub. Invest. Pesq. 2016, 33, 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Zuur, A.F.; Tuck, I.D.; Bailey, N. Dynamic Factor Analysis to Estimate Common Trends in Fisheries Time Series. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2003, 60, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura-Díaz, Y.; Rodríguez-Cueto, Y. Hábitats Del Golfo de Ana María Identificados Mediante El Empleo de Procesamiento Digital de Imágenes. Rev. Invest. Mar. 2012, 32, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Pina-Amargós, F.; Figueredo-Martín, T.; Rossi, N.A. The Ecology of Cuba’s Jardines de La Reina: A Review. Rev. Invest. Mar. 2021, 41, 2–42. [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Pardo, J.; Pierce, G.J.; Cabecinha, E.; Grilo, C.; Assis, J.; Valavanis, V.; Pita, C.; Dubert, J.; Leitão, F.; Queiroga, H. Trends and Drivers of Marine Fish Landings in Portugal Since Its Entrance in the European Union. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2020, 77, 988–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Monte-Luna, P.; Villalobos, H.; Arreguín-Sánchez, F. Variability of Sea Surface Temperature in the Southwestern Gulf of Mexico. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 102, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landsea, C.W.; Franklin, J.L. Atlantic Hurricane Database Uncertainty and Presentation of a New Database Format. Mon. Weather Rev. 2013, 141, 3576–3592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeffding, W. A Non-Parametric Test of Independence. Ann. Math. Stat. 1948, 19, 546–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makowski, D.; Wiernik, B.M.; Patil, I.; Lüdecke, D.; Ben-Shachar, M.S. Correlation: Methods for Correlation Analysis; 2023.

-

R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Holmes, E.E.; Ward, E.J.; Scheuerell, M.D.; Wills, K. MARSS: Multivariate Autoregressive State-Space Modeling; 2024.

- Ramenzoni, V.C.; Borroto Escuela, D.; Rangel Rivero, A.; González-Díaz, P.; Vázquez Sánchez, V.; López-Castañeda, L.; Falcón Méndez, A.; Hernández Ramos, I.; Valentín Hernández López, N.; Besonen, M.R.; et al. Vulnerability of Fishery-Based Livelihoods to Extreme Events: Local Perceptions of Damages from Hurricane Irma and Tropical Storm Alberto in Yaguajay, Central Cuba. Coast. Manage. 2020, 48, 354–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, I.T. The Fisheries of the Cuban Insular Shelf: Culture History and Revolutionary Performance. PhD thesis, Arts and Social Sciences: History, Simon Fraser University: British Columbia, Canada, 1996.

- Moreira, A.; Barcia, S.; Cabrales, Y.; Suárez, A.M.; Fujii, M.T. El Impacto Del Huracán Dennis Sobre El Macrofitobentos de La Bahía de Cienfuegos, Cuba. Rev. Invest. Mar. 2009, 30, 175–185. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrani-Arenal, I.; Perez-Bello, A.; Cabrales-Infante, J.; Povea-Perez, Y.; Hernandez-Gonzalez, M.; Diaz-Rodriguez, O.O. Coastal Flood Forecast in Cuba, Due to Hurricanes, Using a Combination of Numerical Models. Rev. Cub. Meteorol. 2019, 25, 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- INRH Boletín Hidrológico 2021-09; Instituto Nacional de Recursos Hidráulicos: Havana, Cuba, 2021; p. 17.

- Baisre, J.A. Los Complejos Ecológicos de Pesca: Definición e Importancia En La Administración de Las Pesquerías Cubanas. FAO Fisheries Report 1985, 327, 251–272. [Google Scholar]

- Batista-Silva, J.L. Isolíneas Del Módulo de Escurrimiento Medio Anual. Voluntad Hidráulica 1974, 32, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Alheit, J.; Licandro, P.; Coombs, S.; Garcia, A.; Giráldez, A.; Santamaría, M.T.G.; Slotte, A.; Tsikliras, A.C. Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) Modulates Dynamics of Small Pelagic Fishes and Ecosystem Regime Shifts in the Eastern North and Central Atlantic. J. Mar. Syst. 2014, 131, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.B.; González-Quirós, R.; Riveiro, I.; Cabanas, J.M.; Porteiro, C.; Pierce, G.J. Cycles, Trends, and Residual Variation in the Iberian Sardine (Sardina Pilchardus) Recruitment Series and Their Relationship with the Environment. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2012, 69, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Cagide, A.; Claro, R.; Koshelev, B.V. Reproductive Patterns of Fishes of the Cuban Shelf. In Ecology of the marine fishes of Cuba; Claro, R., Lindeman, K.C., Parenti, L.R., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, 2001; pp. 73–114. [Google Scholar]

- Kritzer, J.P.; Hicks, C.C.; Mapstone, B.D.; Pina-Amargos, F.; Sale, P.F.; Fogarty, M.J.; McCarthy, J.J. Ecosystem-Based Management of Coral Reefs and Interconnected Nearshore Tropical Habitats. The Sea 2014, 16, 369–419. [Google Scholar]

- Karr, K.A.; Fujita, R.; Carcamo, R.; Epstein, L.; Foley, J.R.; Fraire-Cervantes, J.A.; Gongora, M.; Gonzalez-Cuellar, O.T.; Granados-Dieseldorff, P.; Guirjen, J.; et al. Integrating Science-Based Co-Management, Partnerships, Participatory Processes and Stewardship Incentives to Improve the Performance of Small-Scale Fisheries. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, V.; Mirabal-Patterson, A.; García-Rodríguez, E.; Karr, K.A.; Whittle, D. The SOS Pesca Project: A Multinational and Intersectoral Collaboration for Sustainable Fisheries, Marine Conservation and Improved Quality of Life in Coastal Communities. MEDICC Review 2018, 20, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzugaray, R.; Puga, R.; Valle, S.; Morales, O.; Grovas, A.; López, L.; Kleisner, K.; Boné, E.; Mangin, T.; Kritzer, J.; et al. Un enfoque multiinstitutional para modelar el beneficio bioeconómico de perspectivas de manejo pesquero en Cuba. Rev. Cub. Invest. Pesq. 2019, 36, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Claro, R.; Baisre, J.A.; Lindeman, K.C.; García-Arteaga, J.P. Cuban Fisheries: Historical Trends and Current Status. In Ecology of Marine Fishes of Cuba; Claro, R., Lindeman, K.C., Parenti, L.R., Eds.; Smithsonian Institution Press: Washington, 2001; pp. 194–219. [Google Scholar]

- Dorta, C.; Martín-Sosa, P. Fishery Essentiality: A Short-Term Decision-Making Method Based on Economic Viability as a Tool to Understand and Manage Data-Limited Small-Scale Fisheries. Fish. Res. 2022, 246, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costello, C.; Ovando, D.; Clavelle, T.; Strauss, C.K.; Hilborn, R.; Melnychuk, M.C.; Branch, T.A.; Gaines, S.D.; Szuwalski, C.S.; Cabral, R.B.; et al. Global Fishery Prospects Under Contrasting Management Regimes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 5125–5129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, F.; Alcantara, E.; Rodrigues, T.; Rotta, L.; Bernardo, N.; Imai, N. Remote Sensing of the Chlorophyll-a Based on OLI/Landsat-8 and MSI/Sentinel-2A (Barra Bonita Reservoir, Brazil). An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017, 90, 1987–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).