Submitted:

23 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

1.2. Model of Combustion Kinetics

1.3. Novelty and Research Gap

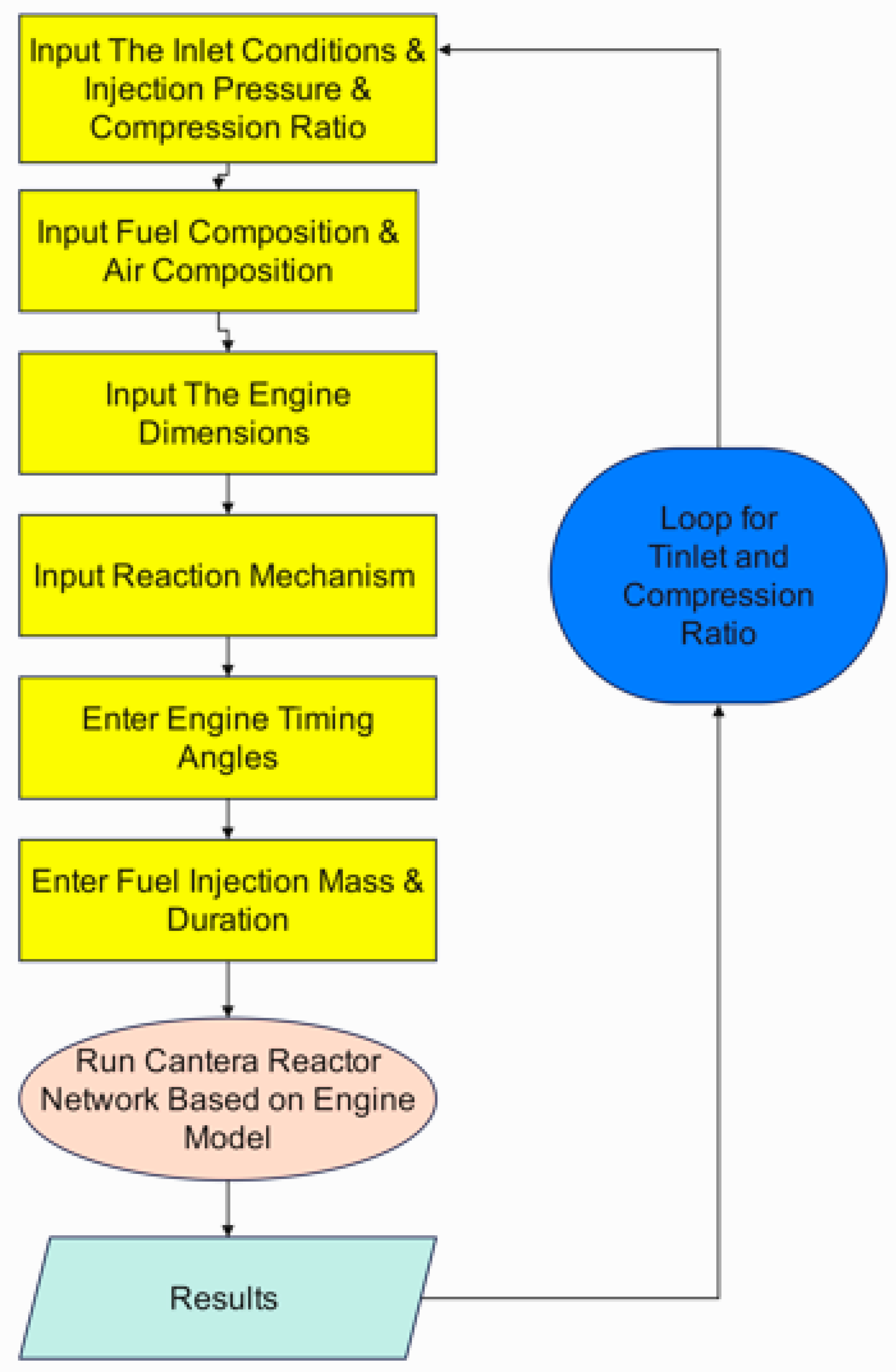

2. Method and Model

2.1. Effects of Compression Ratio and Inlet Temperature on the Performance and Emissions of Hydrogen Engines

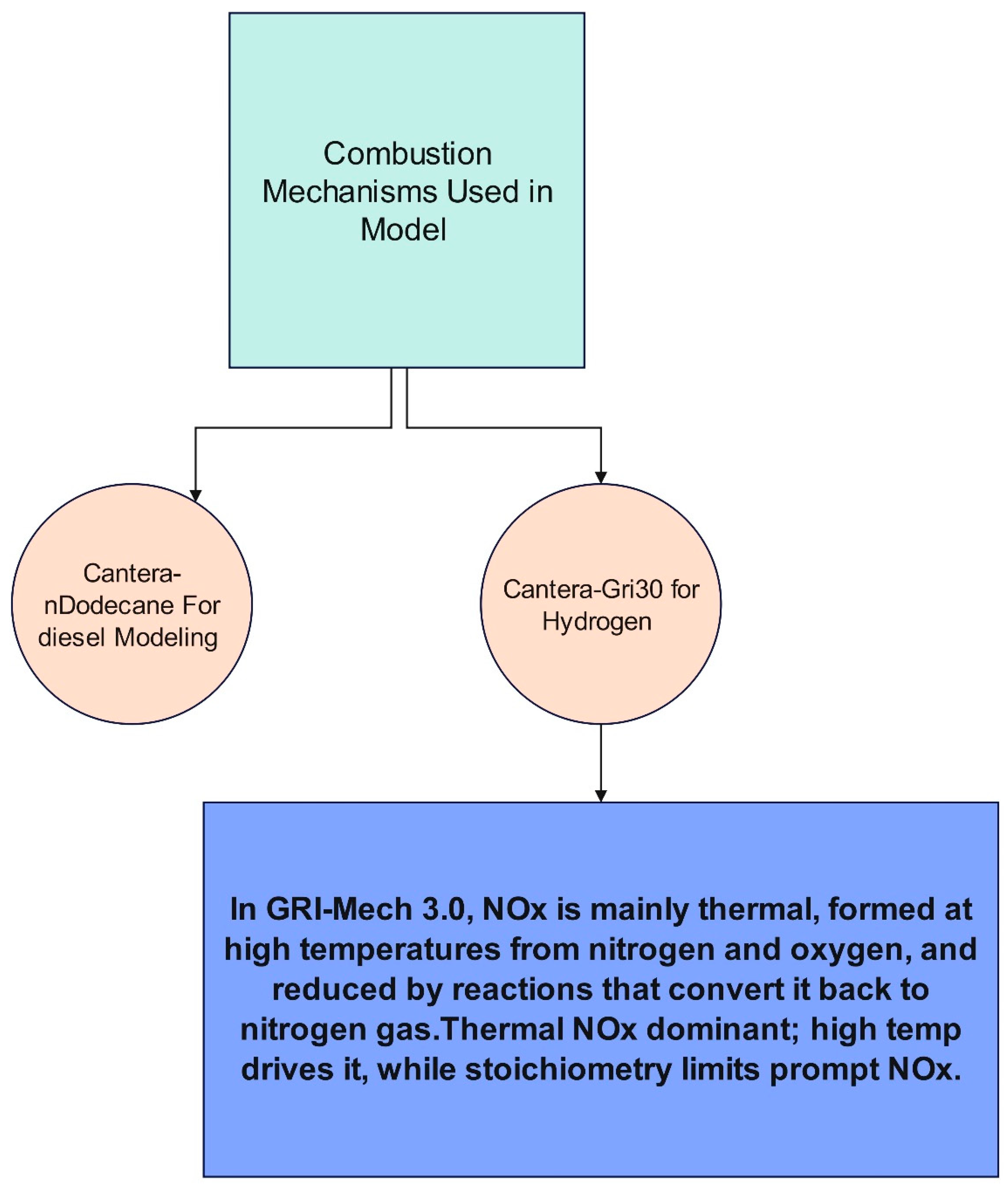

| Aspect | Hydrogen (GRI-Mech 3.0) | Dodecane (Reitz mechanism) | Explanation & Main Factors |

| Reaction mechanism | Uses GRI-Mech 3.0, widely validated for hydrogen and natural gas. | Uses Reitz mechanism, validated for heavy hydrocarbons like dodecane. | Mechanism defines how the fuel burns, including ignition delay, flame propagation, and pollutant formation. |

| Reactor type | Treated as a well-stirred cylinder with variable volume. | Same approach. | Assumes gas inside is uniform in temperature, pressure, and composition. |

| Geometry & piston motion | Volume changes based on compression ratio and piston speed profile. | Same. | The piston movement compresses and expands the charge, driving the cycle. |

| Cycle events | Intake, injection, combustion, and exhaust triggered by crank angle timing. | Same. | Valves and injector open and close at specific crank angles. |

| Fuel injection | Hydrogen injected as gas; injector delivers the required mass during the open period. | Dodecane injected as gaseous equivalent in this model. | Ensures correct fuel mass each cycle; in reality, dodecane would involve spray and evaporation. |

| Inlet and outlet valves | Connect the cylinder to inlet and exhaust reservoirs. | Same. | Flow depends on valve opening and pressure difference. |

| Piston model | Moving wall imposes cylinder volume change. | Same. | Converts thermodynamic pressure into piston work. |

| Chemistry solver | Uses a stiff numerical solver to handle fast hydrogen reactions. | Same solver applied to dodecane chemistry. | Ensures stability during rapid ignition and combustion. |

| Numerical stability | Controlled with tight tolerances and a temperature rise limit per step. | Same approach. | Prevents the solver from diverging during heat release. |

| Cycle tracking | Eight engine revolutions simulated with resolution of one degree crank angle. | Same. | Captures full intake–compression–combustion–expansion–exhaust sequence. |

| Heat release | Calculated from hydrogen reaction rates inside the cylinder. | From dodecane reactions. | Represents the chemical energy released from fuel. |

| Work and power | Expansion work integrated over the piston cycle; average power derived. | Same method. | Converts cylinder pressure and piston movement into mechanical output. |

| Efficiency | Ratio of useful expansion work to total heat released. | Same. | Provides a cycle efficiency estimate (idealized, no friction or heat losses). |

| Emissions | Mainly water and nitrogen oxides; carbon monoxide is negligible. | Carbon monoxide and soot are significant, plus nitrogen oxides. | Hydrogen burns clean but can form high NOx at high temperatures; dodecane produces carbon emissions and particulates. |

| Equivalence ratio (mixture richness) | Calculated based on hydrogen injected compared to oxygen or air available at intake closing. | Calculated based on dodecane injected compared to oxygen or air available at intake closing. | Expresses whether the mixture is lean, stoichiometric, or rich. |

| Combustion kinetics main dependencies | Strongly dependent on temperature, pressure, mixture richness, and exhaust gas recirculation. | Same dependencies, with additional influence from evaporation and mixing of liquid fuel. | These factors control ignition timing, flame development, and pollutant levels. |

| Parameter | Diesel Engine (n-dodecane) | hydrogen Engine |

| Reaction Mechanism | ndodecane_Reitz.yaml | gri30.yaml |

| Fuel Composition | C12H26:1 (n-dodecane) | H2:1 (hydrogen) |

| Inlet Temperature (K) | 300 | 400 |

| Compression Ratio (ε) | 20 | 20 |

| Engine Speed (rpm) | 3000 | 3000 |

| Displaced Volume (m³) | 5.00E-04 | 5.00E-04 |

| Piston Diameter (m) | 0.083 | 0.083 |

| Expansion Power (kW) | 18.5 | 19.5 |

| Heat Release Rate (kW) | 33.6 | 37.2 |

| Efficiency (%) | 55.2 | 52.3 |

| CO Emission (ppm) | 8.9 | 0 |

| Inlet Valve Angle (deg) | -18 (open) to 198 (close) | -18 (open) to 198 (close) |

| Outlet Valve Angle (deg) | 522 (open) to 18 (close) | 522 (open) to 18 (close) |

| Injector Angle (deg) | 350 (open) to 365 (close) | 350 (open) to 365 (close) |

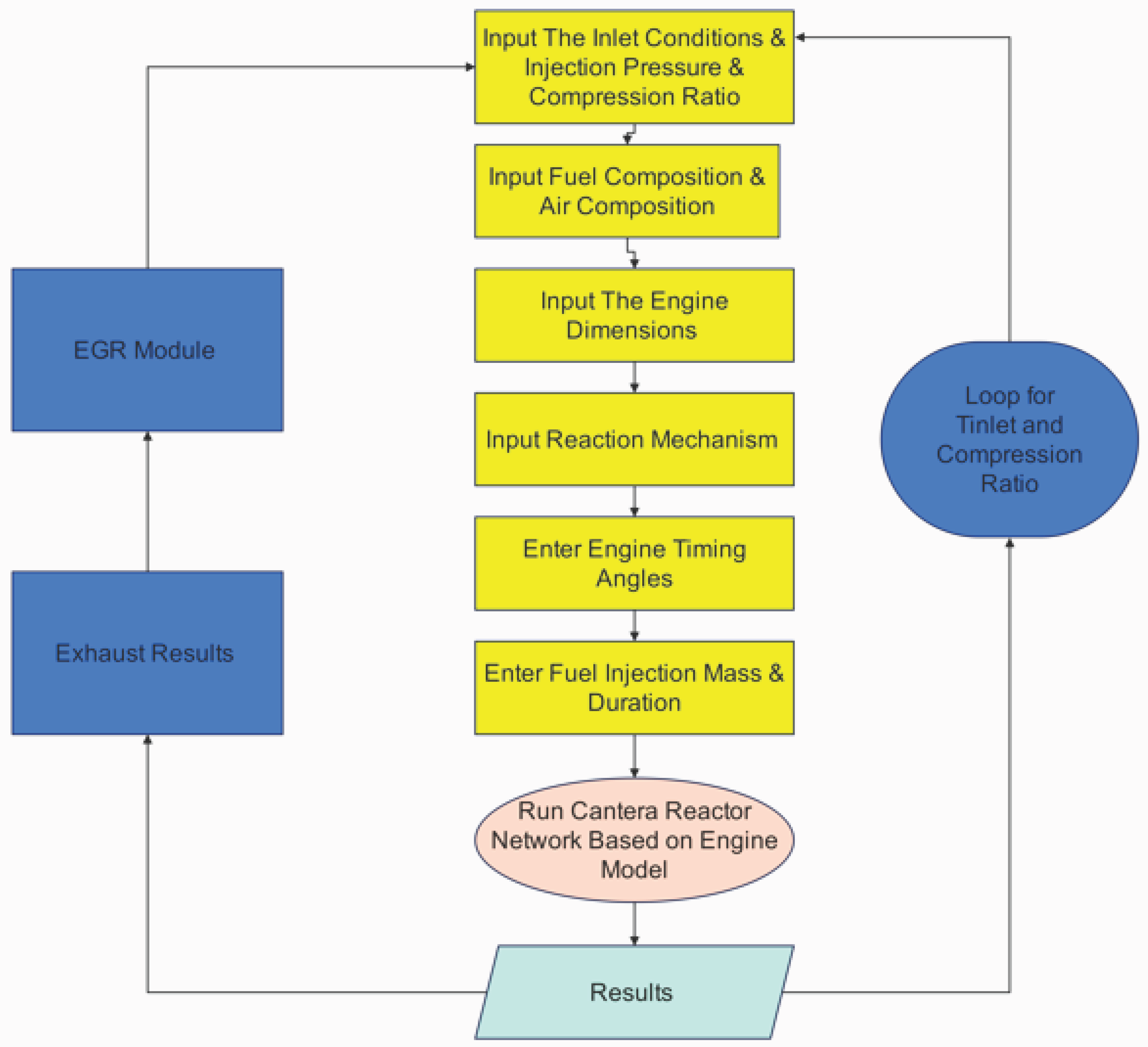

2.2. EGR Modeling in a Hydrogen Engine

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Comparison of Performance and Combustion Characteristics of Diesel and Hydrogen Engines

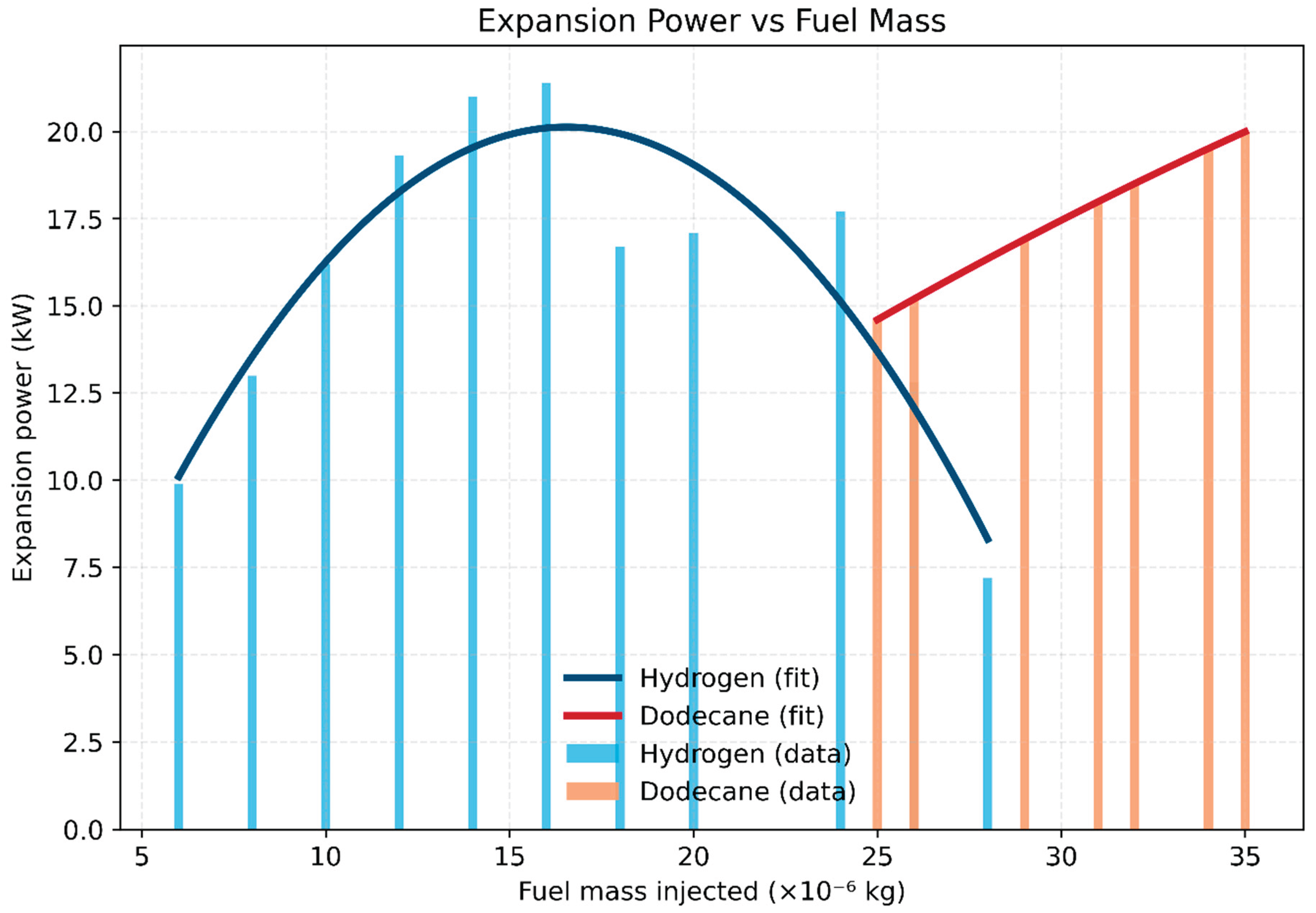

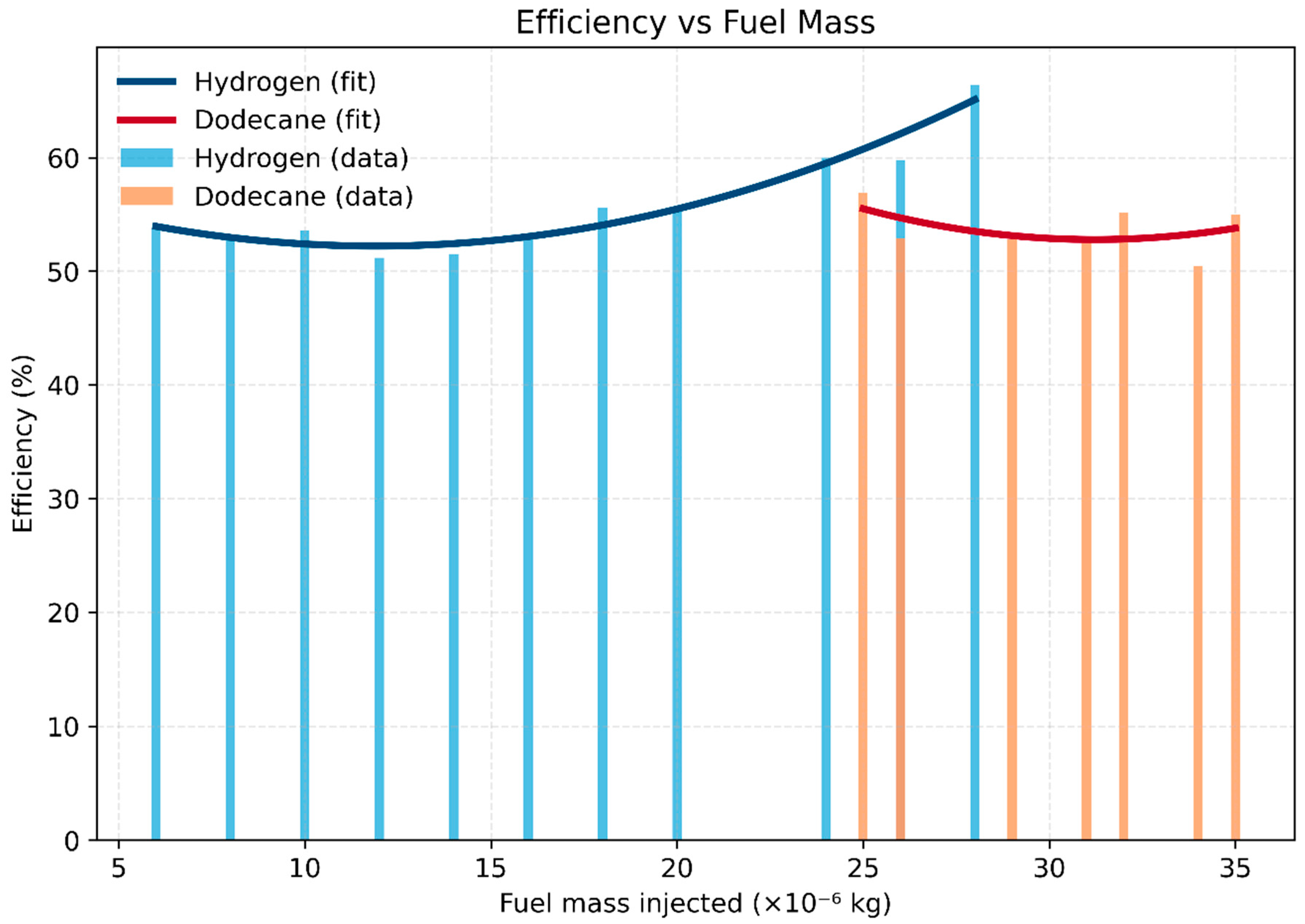

- Fuel mass requirement: Hydrogen achieves comparable peak power (~21 kW) with much less injected mass (6–28 ×10⁻⁶ kg) compared to dodecane (25–35 ×10⁻⁶ kg). This reflects hydrogen’s high specific energy per unit mass of oxidizer.

- Operational window: Hydrogen sustains stable combustion across a broader mass range. At the same time, dodecane is more limited and sensitive to over- or under-fueling, while hydrogen could operate in a wide span of equivalence ratio with a chance to decrease NOx in fuel-lean mixtures.

- Intake conditions: Dodecane ignites reliably at 300 K intake, while hydrogen requires preheating to ~400 K to ensure stable combustion. Once ignited, hydrogen’s broad flammability and rapid kinetics allow operation over richer conditions with efficiency advantages.

- Hydrogen: Efficiency remains above 50% across the entire fueling range, climbing steadily to a maximum of ~66% at the richest condition (≈ 2.8 ×10⁻⁵ kg injected). This demonstrates hydrogen’s capability to maintain high efficiency even at elevated equivalence ratios, due to fast kinetics and the absence of carbon-based incomplete combustion losses.

- Dodecane: Efficiency peaks lean (~57% at 2.5 ×10⁻⁵ kg injected) but drops near stoichiometry, falling to ~52–55% as fueling increases. This reflects increasing CO and incomplete oxidation penalties at higher injection masses.

- Comparative insight: Hydrogen delivers a clear efficiency advantage (~9–10 percentage points higher) at rich fueling, while dodecane’s efficiency window is narrower and more sensitive to φ. Hydrogen’s broad stable range offers flexibility for lean- and rich-burn strategies, while dodecane requires careful fueling control to avoid efficiency loss.

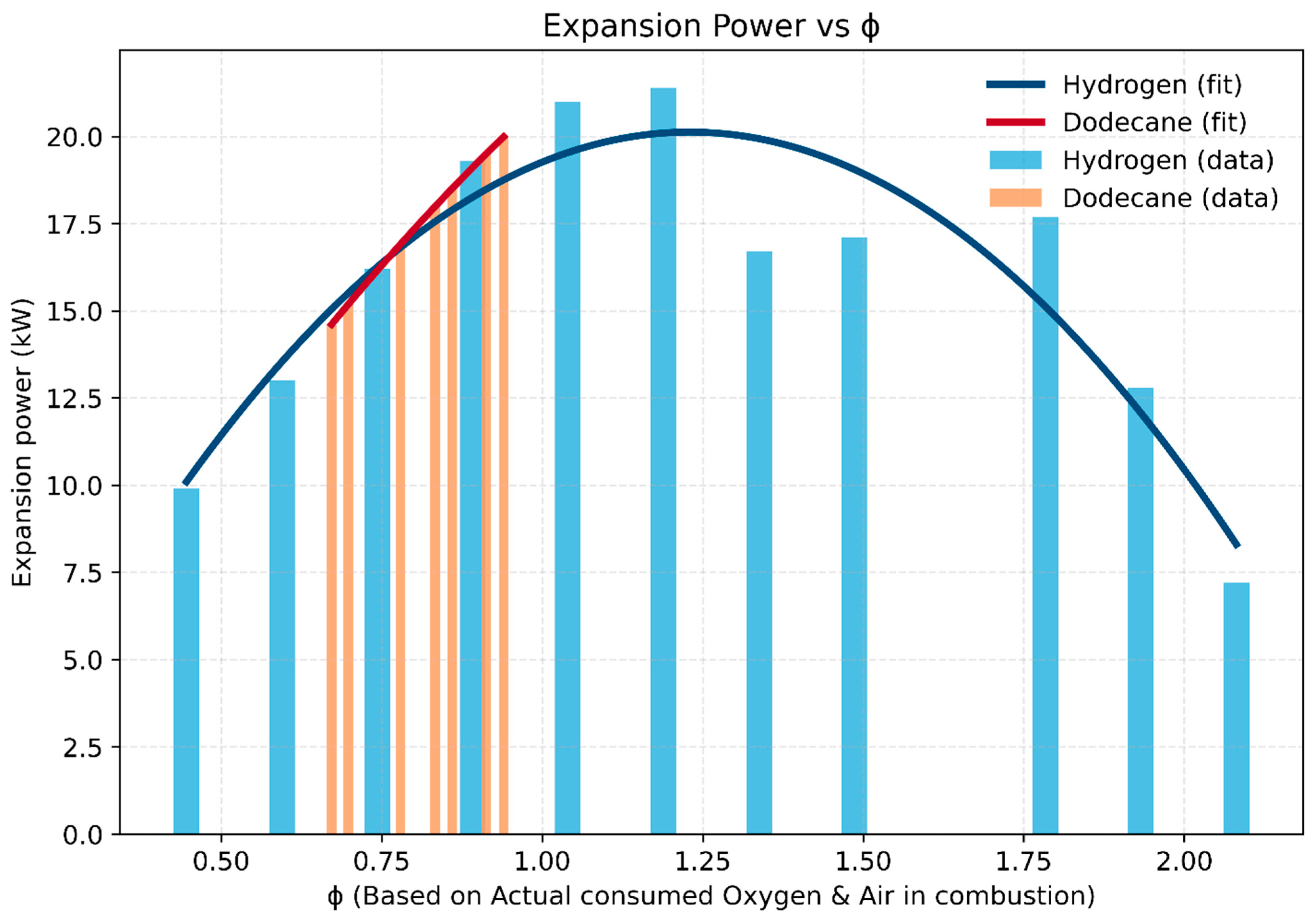

- Hydrogen: Expansion power peaks at ~21 kW around ϕ ≈ 1.2, and remains relatively high across a broad operating window (ϕ = 0.45–2.1). This highlights hydrogen’s wide flammability limits and robust combustion stability at both lean and rich conditions.

- Dodecane: Power output peaks near 20 kW but within a much narrower range (ϕ = 0.67–0.94). Beyond this region, incomplete combustion and mixture inhomogeneity limit power rise, making the system more sensitive to small fueling changes.

- Comparative insight: While both fuels achieve similar peak power, hydrogen’s broader ϕ operability range allows greater flexibility in engine operation and better tolerance to load or mixture variations. In contrast, dodecane requires tight control near stoichiometric operation, where deviations rapidly reduce performance.

- Practical implication: Hydrogen enables both lean-burn efficiency strategies and rich-burn high-power modes, whereas dodecane is constrained to a narrow stoichiometric band.

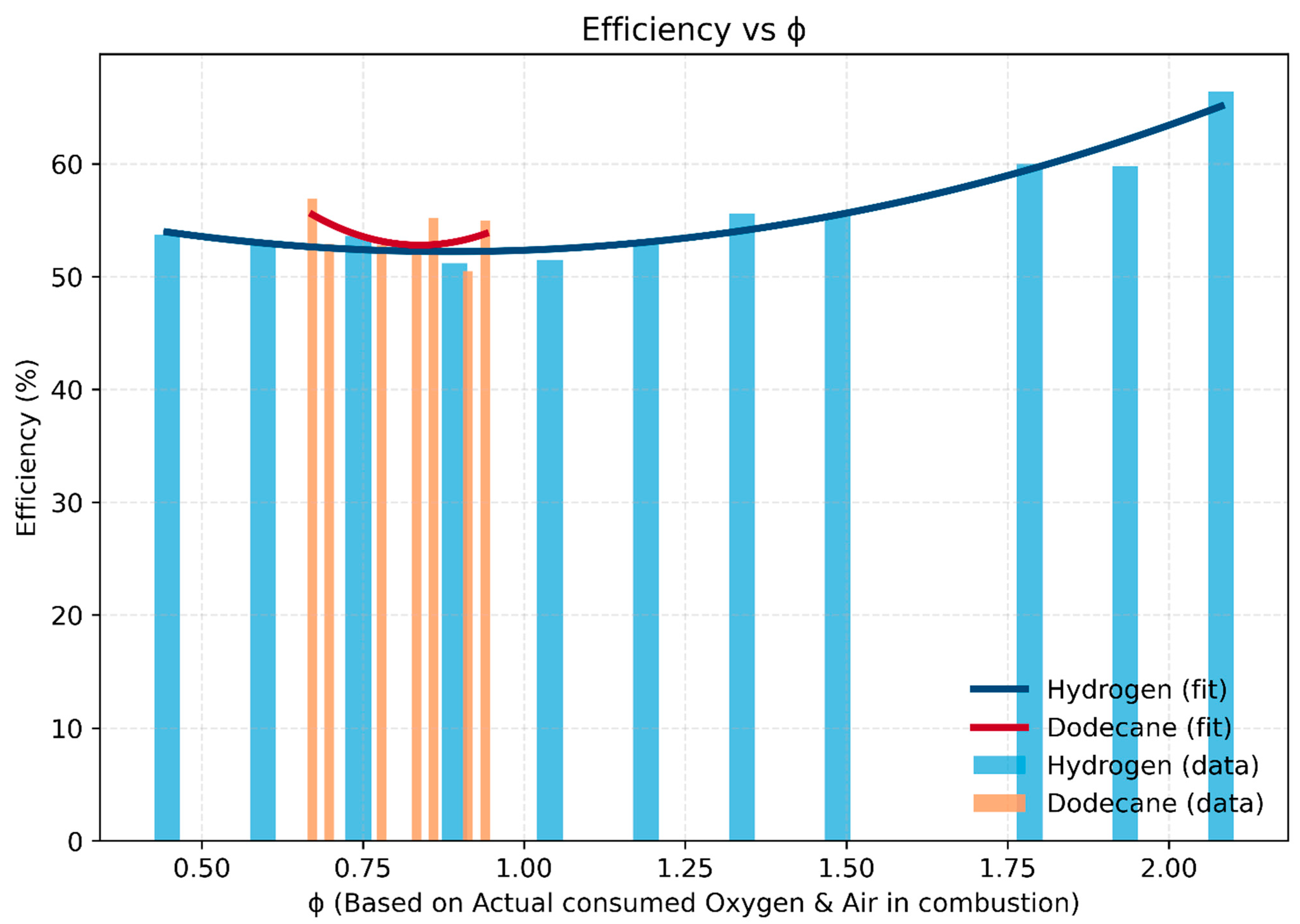

- Hydrogen: Efficiency remains above 50% across the entire operating window (ϕ = 0.45–2.08) and increases significantly with richer mixtures, reaching ~66% at ϕ ≈ 2.0. This trend reflects hydrogen’s high reactivity, rapid combustion, and the absence of incomplete carbon oxidation losses.

- Dodecane: Efficiency stays within 52–57% but in a much narrower window (ϕ = 0.67–0.94). Outside this range, combustion is unstable or penalized by incomplete oxidation, limiting its operability.

- Comparative insight: Hydrogen provides a broader and more robust efficiency range, particularly under rich conditions, while dodecane is lean-favoring but tightly bound around stoichiometry.

- Practical implication: The wide ϕ operability of hydrogen makes it suitable for both high-efficiency lean-burn modes and high-power rich-burn modes. Dodecane, on the other hand, requires strict control near stoichiometry to maintain stable and efficient combustion.

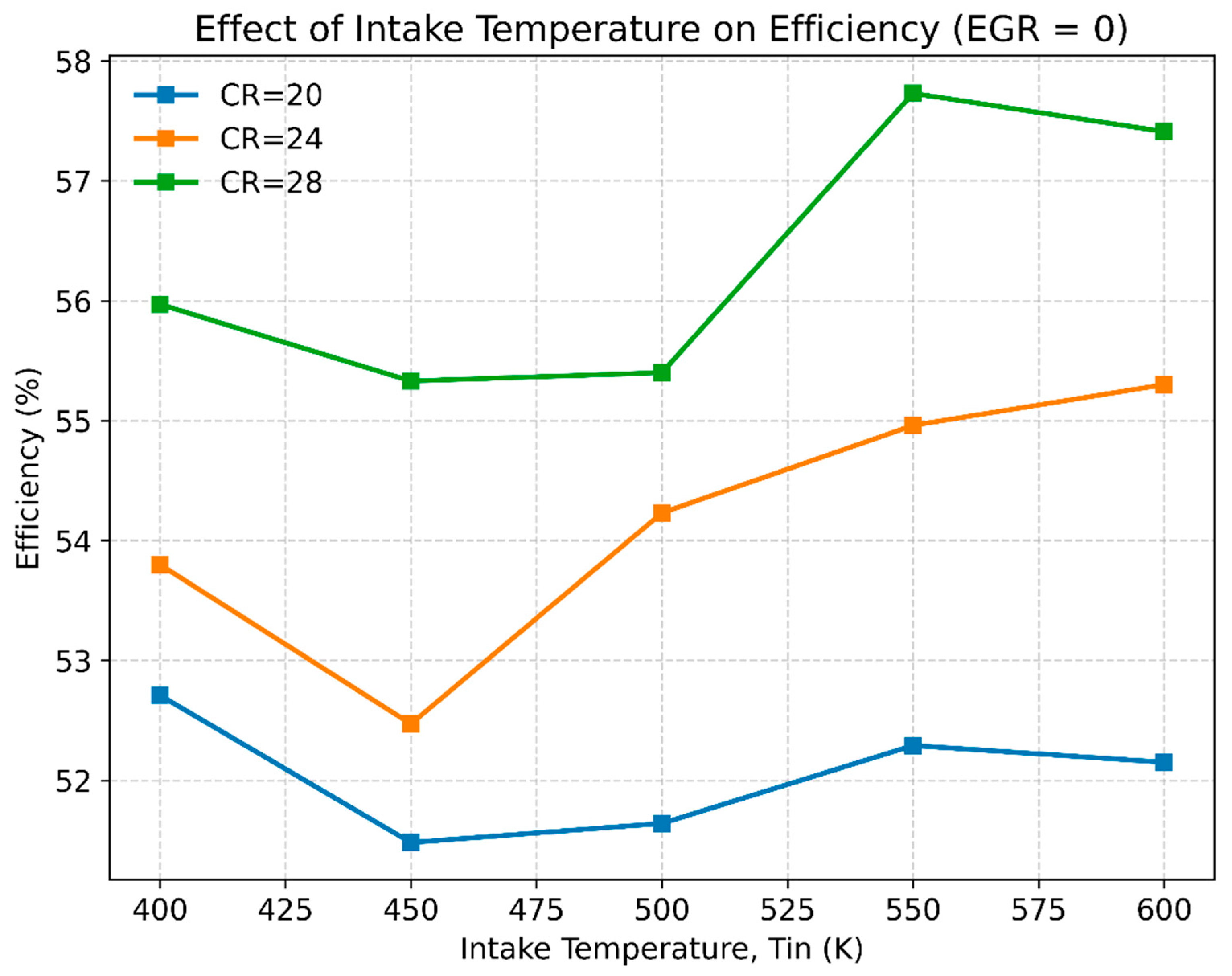

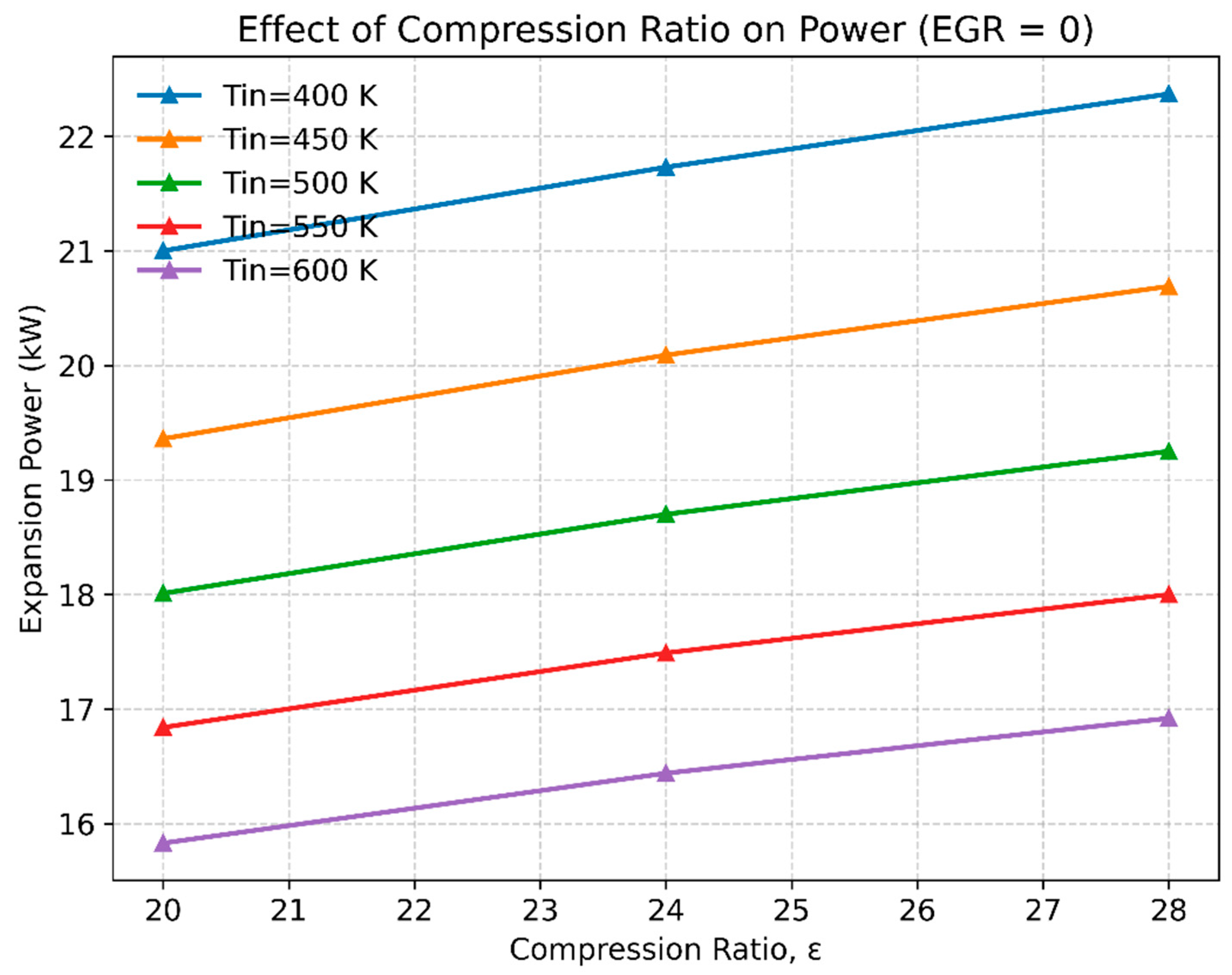

3.2. The Effect of Compression Ratio and Inlet Temperature on Engine Performance

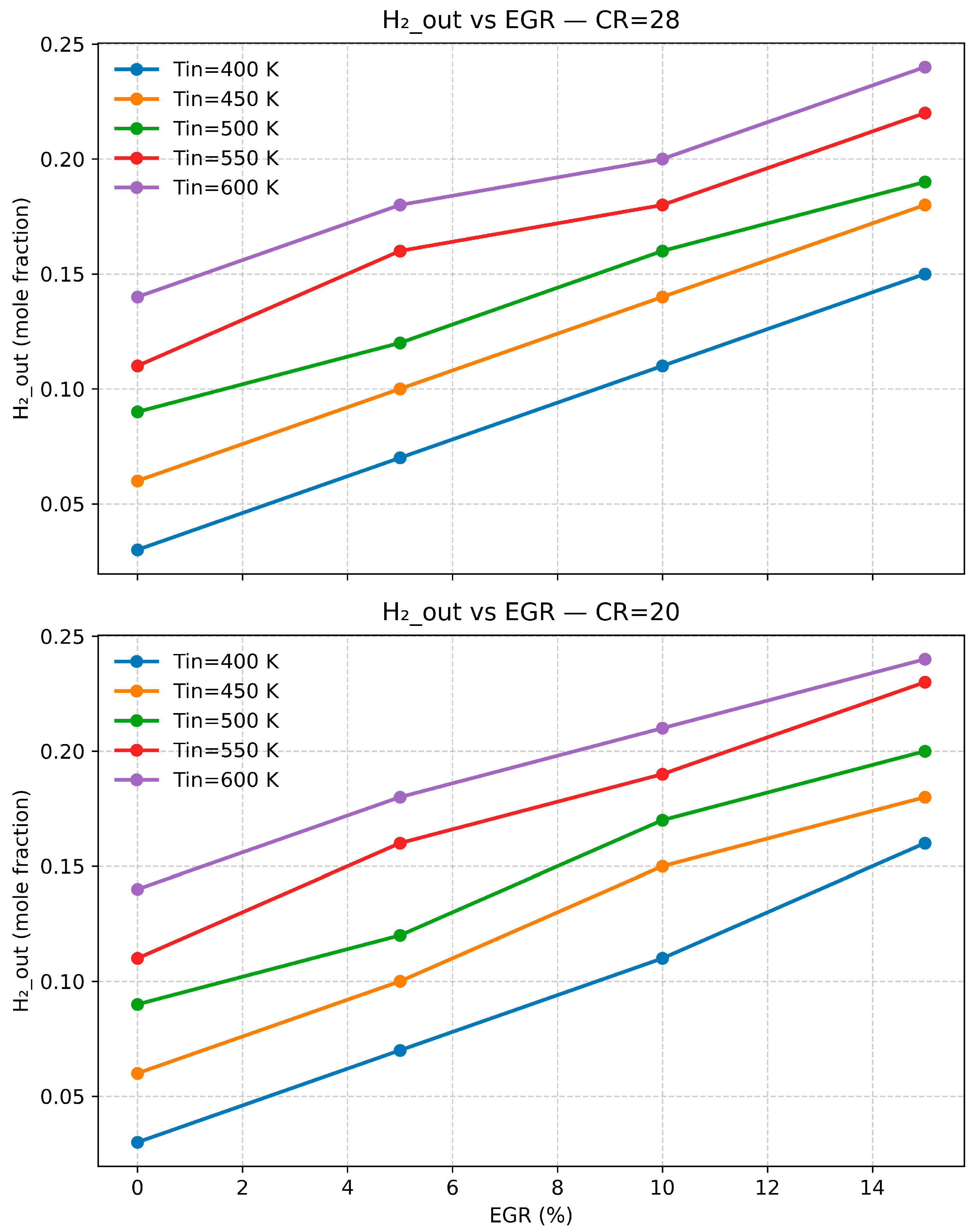

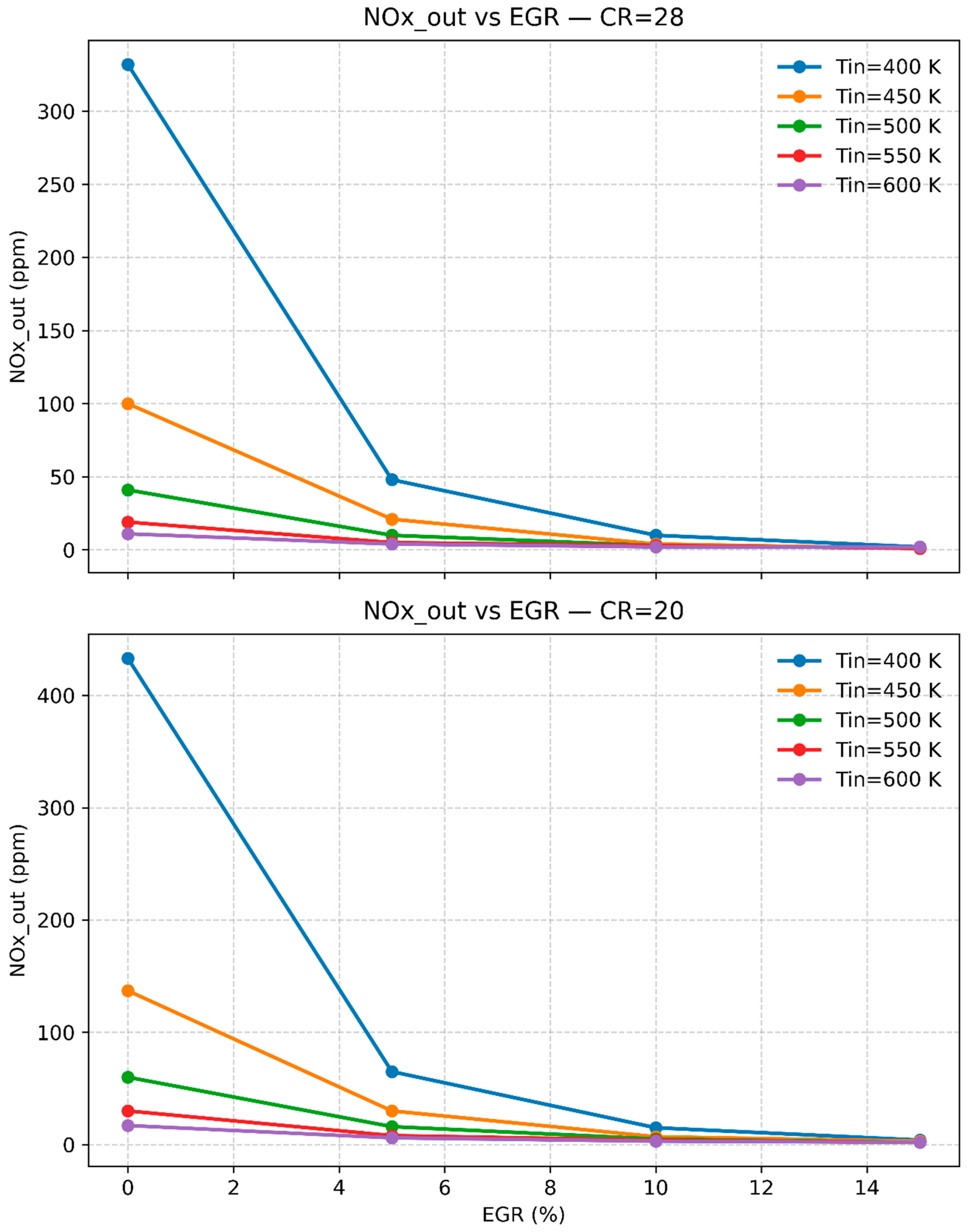

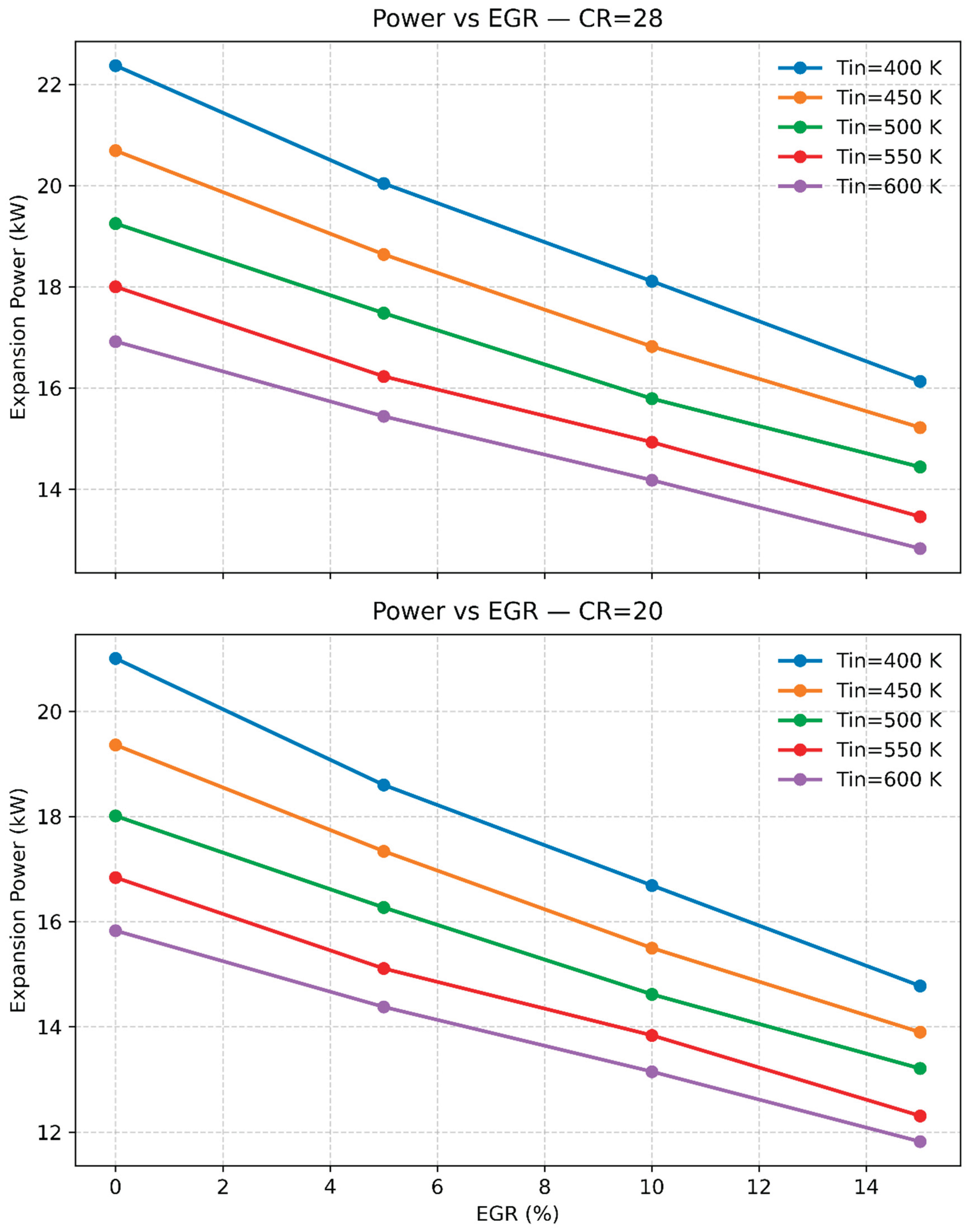

3.3. The Impact of Temperature, Compression Ratio, and Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) on Engine Emissions and Performance

4. Validation

4.1. Validation Introduction

4.2. Validation Details

| Study | Validation of Findings |

| Tsujimura & Suzuki (2017) | hydrogen.CR and intake temperature are , the results emphasize their critical influence on combustion phasing and hydrogen usability in dual-fuel diesel engines.[1] |

| Chintala & Subramanian (2014) | Introducing hydrogen increased the engine’s thermal efficiency but also led to a significant rise in NOx emissions due to hydrogen’s high combustion temperature[21] |

| Rosati & Aleiferis (2009) | In the hydrogen HCCI engine experiment, elevated intake air temperatures (200–400 °C) enabled stable autoignition by compensating for the low compression ratio of the optical engine. This preheating allowed homogeneous combustion without spark or additives. To control NOx, the system operated under lean burn conditions (λ = 1.2–3.0).[12]Supports our numerical result: high CR/intake temp enable ignition. |

| Chaichan & Al-Zubaidi (2015) | An experimental study demonstrated that hydrogen requires higher compression ratios for effective operation in a dual-fuel compression ignition engine. Using a single-cylinder Ricardo E6 engine at 1500 rpm, hydrogen was introduced as a supplementary fuel to diesel. The baseline Higher Useful Compression Ratio (HUCR) for diesel alone was 17.7:1, but this increased when hydrogen was added.[22] Supports our numerical result: high CR/intake temp enable ignition. |

| Lee et al.2013 | It was previously believed that compression ignition of neat hydrogen-air mixtures was impossible due to hydrogen’s high auto-ignition temperature and risk of backfire. However, this study demonstrated successful autoignition at a high compression ratio of 32 under cold start conditions, reduced to 26 under firing. This breakthrough proves hydrogen can ignite without additives [13] Supports our numerical result: high CR/intake temp enables ignition. |

5. Conclusions

6. Standards Refrence

References

- T. Tsujimura and Y. Suzuki, “The utilization of hydrogen in hydrogen/diesel dual fuel engine,” Int J hydrogen Energy, vol. 42, no. 19, 2017. [CrossRef]

- W. H. a. P. H. Stoke, “hydrogen-cum-oil gas as an auxiliary fuel for airship compression ignition engines,” British Royal Aircraft Establishment . Report No. E 3219, , 1930.

- F. H. N. M. S. J. C. Quang Truc Dam, “Modeling and simulation of an Internal Combustion Engine using hydrogen: A MATLAB implementation approach,” Engineering Perspective ISSN: 2757-9077, 2024.

- G. A. Karim, “hydrogen as a spark ignition engine fuel,” Int J hydrogen Energy, vol. 28, no. 5, 2003. [CrossRef]

- Amr Abbass, “hydrogen as a Clean Fuel: Review of Production, Storage, Fuel Cells, and Engine Technologies for Decarbonization,” International Journal of Progressive Research in Engineering Management and Science (IJPREMS), vol. 4, no. 11, 2024.

- Amr Abbass, “hydrogen Integration in Gas Turbines: OEM Innovations and Challenges in Advancing Sustainable Energy Systems,” Journal of Management andEngineering Sciences, 2024.

- K. Wróbel, J. Wróbel, W. Tokarz, J. Lach, K. Podsadni, and A. Czerwiński, “hydrogen Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles: A Review,” 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Hwang, K. Maharjan, and H. J. Cho, “A review of hydrogen utilization in power generation and transportation sectors: Achievements and future challenges,” 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Dimitriou, “hydrogen Compression Ignition Engines,” in Green Energy and Technology, vol. Part F1098, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. M. Domínguez, J. J. Hernández, Á. Ramos, M. Reyes, and J. Rodríguez-Fernández, “hydrogen or hydrogen-derived methanol for dual-fuel compression-ignition combustion: An engine perspective,” Fuel, vol. 333, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Ikegami, K. Miwa, and M. Shioji, “A study of hydrogen fuelled compression ignition engines,” Int J hydrogen Energy, vol. 7, no. 4, 1982. [CrossRef]

- M. F. Rosati and P. G. Aleiferis, “hydrogen SI and HCCI combustion in a Direct-Injection optical engine,” in SAE Technical Papers, 2009. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Lee, Y. R. Kim, C. H. Byun, and J. T. Lee, “Feasibility of compression ignition for hydrogen fueled engine with neat hydrogen-air pre-mixture by using high compression,” 2013. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Homan, R. K. Reynolds, P. C. T. De Boer, and W. J. McLean, “hydrogen-fueled diesel engine without timed ignition,” Int J hydrogen Energy, vol. 4, no. 4, 1979. [CrossRef]

- A. T. Kirkpatrick, Internal Combustion Engines: Applied Thermosciences, Fourth Edition. 2020. [CrossRef]

- H. K. M. I. S. R. L. S. and B. W. Weber. David G. Goodwin, “Cantera: An object-oriented software toolkit for chemical kinetics, thermodynamics, and transport processes. https://www.cantera.org, 2023. Version 3.0.0.,” Cantera.

- A. Abbass, “The Numerical Modeling of Internal Combustion Engines with Application to Simulation of Combustion of Single-Cylinder HCCI engine by Cantera and Application of Implementation of an Integrative MATLAB Engine Model and Validation on Waukesha VHP Series Engines,” International Journal of Research Publication and Reviews, vol. 4, no. 10, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Li, Y. Wang, B. Jia, Z. Zhang, and A. Roskilly, “Numerical Investigation on NOx Emission of a hydrogen-Fuelled Dual-Cylinder Free-Piston Engine,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 3, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. H. W. Funke, N. Beckmann, J. Keinz, and A. Horikawa, “30 Years of Dry-Low-NOx Micromix Combustor Research for hydrogen-Rich Fuels - An Overview of Past and Present Activities,” J Eng Gas Turbine Power, vol. 143, no. 7, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Sharma and A. Dhar, “Compression ratio influence on combustion and emissions characteristic of hydrogen diesel dual fuel CI engine: Numerical Study,” Fuel, vol. 222, 2018. [CrossRef]

- V. Chintala and K. A. Subramanian, “hydrogen energy share improvement along with NOx (oxides of nitrogen) emission reduction in a hydrogen dual-fuel compression ignition engine using water injection,” Energy Convers Manag, vol. 83, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. Chaichan and D. S. M. Al-Zubaidi, “A practical study of using hydrogen in dual – fuel compression ignition engine,” International Publication Advanced Science Journal, vol. 2, pp. 1–10, 2015.

- Efstathios-Al. Tingas, hydrogen for Future Thermal Engines. 2023.

- E. Al Tingas and A. M. K. P. Taylor, “hydrogen: Where it Can Be Used, How Much is Needed, What it May Cost,” in Green Energy and Technology, vol. Part F1098, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Que, J., Xia, Y., Li, X., Jiang, Q., & Feng, L. (2024). A comparative study of the effects of EGR on combustion and emission characteristics of port fuel injection and late direct injection in hydrogen internal combustion engine. Applied Energy, 375, 123830. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K., Hori, T., & Akamatsu, F. (2022). Fundamental Study on hydrogen Low-NOx Combustion Using Exhaust Gas Self-Recirculation. Processes, 10(1), 130. [CrossRef]

- Irimescu, A.; Vaglieco, B.M.; Merola, S.S.; Zollo, V.; De Marinis, R. Conversion of a Small-Size Passenger Car to hydrogen Fueling: 0D/1D Simulation of EGR and Related Flow Limitations. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Mohamed, S. Vijayaraghavan, and A. Krishnan, “Performance and emission characteristics of a hydrogen gasoline direct injection engine under lean burn conditions,” SAE International Journal of Engines, vol. 17, no. 4, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Shamkuwar, A. Khare, and V. Kumar, “Comparative performance and emission analysis of diesel–hydrogen and diesel–CNG dual fuel engines,” International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, vol. 50, no. 5, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. Akhtar, R. Ahmad, and H. Khan, “Experimental investigation on performance enhancement and NOx control of a dual-fuel diesel–hydrogen engine,” Energy Reports, vol. 11, pp. 5520–5535, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. Musy, A. Rossi, and C. Boulouchos, “Direct injection versus port fuel injection in hydrogen-fueled internal combustion engines: Efficiency and emission trade-offs,” Fuel, vol. 354, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Huang, L. Zhang, and T. Zhao, “Influence of injection timing on NOx reduction in a direct-injection hydrogen engine,” Applied Energy, vol. 347, 2025. [CrossRef]

- X. Qin, H. Wang, and Y. Chen, “Combustion characteristics and heat release analysis of a hydrogen-assisted compression ignition engine,” International Journal of Engine Research, vol. 26, no. 3, 2025. [CrossRef]

- A. Abdelwahed, M. El-Sayed, and K. Mahmoud, “Improving brake thermal efficiency and reducing emissions in hydrogen-fueled CI engines: An experimental approach,” Energy Conversion and Management, vol. 307, 2025. [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), 40 CFR Part 60, Subpart JJJJ — Standards of Performance for Stationary Spark Ignition Internal Combustion Engines, Washington, DC, USA. [Online]. Available: https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-40/chapter-I/subchapter-C/part-60/subpart-JJJJ.

- European Commission, Regulation (EC) No. 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on type approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6), Official Journal of the European Union, L 171/1, June 29, 2007. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32007R0715.

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Emission Standards Reference Guide: EPA Emission Standards for Nonroad Engines and Vehicles (Tier 1–4), Washington, DC, USA. [Online]. Available: https://www.epa.gov/emission-standards-reference-guide/epa-emission-standards-nonroad-engines-and-vehicles.

| Research/Strategy | Year | Compression Ratio (CR) | Key Findings | Challenges/Limitations |

| Helmore and Stokes | 1930 | 11.6 | Attempted CI operation with hydrogen. Observed misfiring and violent detonation.[2] | hydrogen’s characteristics make it challenging to ignite solely through compression. |

| Homan et al. (Glow Plug Assistance) | 1979 | 29 | Glow plugs provided stable ignition, higher IMEP than diesel, and knock-free combustion.[14] | Continuous glow plug use led to efficiency losses due to thermal demands. |

| Ikegami et al. | 1982 | 18.6 | Claimed successful hydrogen CI operation; later contested—possible ignition due to contaminants.[11] | Ignition reliability was limited without pilot fuel or hot spots. |

| Rosati and Aleiferis | 2000 | 17.5 | Achieved hydrogen ignition at 200-400°C intake with ultra-lean mixtures [12] | Elevated intake temperatures increased NOx emissions and energy use. |

| Lee et al. | 2013 | >26 | Demonstrated possible hydrogen CI with CRs as high as 26-32[13] | Narrow operating range with risk of knocking and backfire at high CRs. |

| Case | Tin (K) | CR | EGR (%) | Power (kW) | η (%) | Nox out (ppm) | H₂ out (mf) | Rationale |

| 1 | 400 | 28 | 5 | 20.04 | 55.7 | 48 | 0.07 | Highest power with minimal hydrogen slip; moderate NOx reduction. |

| 2 | 400 | 28 | 10 | 18.11 | 57.24 | 10 | 0.11 | Balanced compromise: large NOx reduction with acceptable power penalty. |

| 3 | 400 | 28 | 15 | 16.13 | 58.95 | 2 | 0.15 | Ultra-low NOx regime; significant power penalty and higher hydrogen slip. |

| 4 | 450 | 28 | 5 | 18.64 | 57.25 | 21 | 0.1 | High efficiency with moderate NOx control; power slightly lower than Case 1. |

| 5 | 450 | 28 | 10 | 16.82 | 58.2 | 4 | 0.14 | Strong NOx reduction with reasonable efficiency; reduced power. |

| 6 | 400 | 24 | 5 | 19.35 | 53.79 | 55 | 0.07 | Power-oriented option under moderate compression ratio constraints. |

| 7 | 400 | 24 | 10 | 17.41 | 55.94 | 12 | 0.11 | Balanced choice for CR = 24 with significant NOx reduction. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).