1. Introduction

Nutritional supplementation is widely adopted in resistance-training and bodybuilding communities [1,2,3], where small improvements in training quality, recovery, or translational efficiency can yield measurable changes in muscle size. This topic matters beyond sport performance because skeletal muscle contributes to metabolic health, functional capacity, and injury resilience across the lifespan [5,6]. Yet the literature is difficult to interpret due to heterogeneity in study designs, participant training status, dosing strategies, and—critically—the choice of outcomes [7,8,9,10]. Clarifying how supplements map onto biological mechanisms and morphology-direct endpoints can reduce confusion and improve practice.

A key challenge is that changes in whole-body or regional lean mass (e.g., DXA) do not necessarily reflect true hypertrophy, as they may be influenced by water, glycogen, or non-contractile compartments. By contrast, ultrasound and MRI measurements of muscle thickness or cross-sectional area more directly index myofibrillar accretion in trained populations [11,12,13,14,15]. Even so, imaging protocols vary in site selection, reliability, and standardization, which can contribute to divergent findings across studies. These measurement issues, coupled with differences in training programs and adherence, motivate a morphology-anchored appraisal of the evidence [16,17,18,19,20].

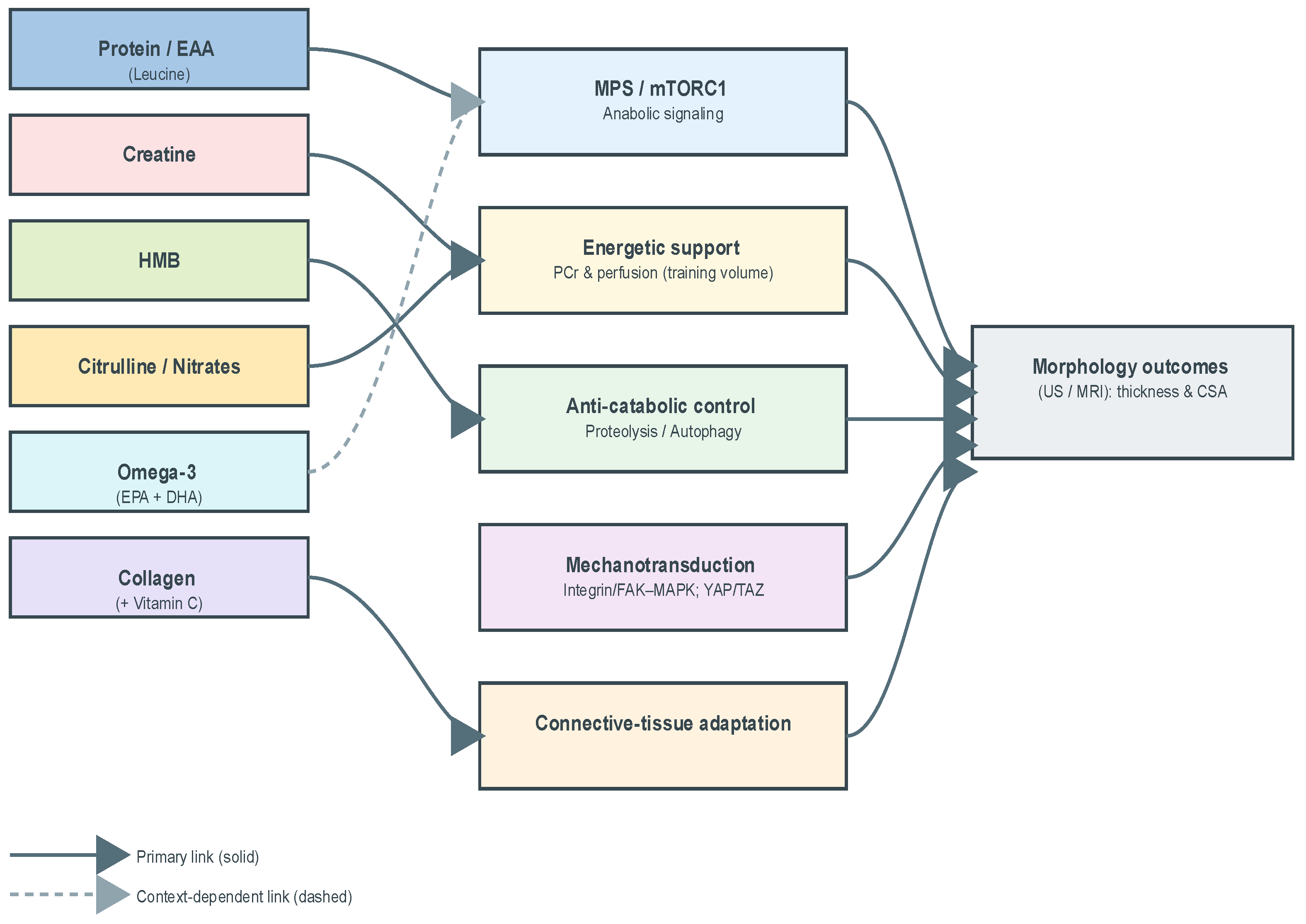

Mechanistically, several modules plausibly connect common nutritional supplements to hypertrophy. Anabolic signaling and muscle protein synthesis (MPS)—regulated in part by mTORC1 and translational control—are responsive to high-quality protein and essential amino acids (EAA), with the leucine-threshold concept frequently discussed in trained adults [21,22,23,24,25]. Creatine monohydrate supports high-intensity work via phosphocreatine buffering, which can enhance set quality and cumulative training volume over weeks. β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB) may reduce protein breakdown and improve net protein balance under specific stressors [26,27,28,29,30]. Mechanotransduction pathways (e.g., integrin/FAK–MAPK and related axes, including YAP/TAZ) converge on translational machinery and interact with nutritional status [30,31,32,33,34,35]. Common adjuncts—omega-3 fatty acids, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen—are hypothesized to sensitize anabolic signaling, improve perfusion/tolerance to training, or support connective-tissue adaptation, respectively [36,37,38,39,40].

The current field shows asymmetric strength of evidence across supplements. Protein/EAA interventions are generally supportive when habitual intake is modest or distribution is suboptimal, with diminishing returns once adequate intake and per-meal leucine thresholds are consistently achieved [40,41,42,43,44,45]. Creatine’s clearest effects relate to performance and training-volume accrual; morphology-level changes tend to appear in sufficiently long, well-controlled programs and are sometimes obscured by body-composition surrogates [46,47,48,49,50]. HMB shows mixed outcomes in well-trained, eucaloric settings, with potential benefits under high load or energy deficit. Adjuncts such as omega-3, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen offer plausible mechanistic support for training tolerance or connective-tissue function, yet direct morphology-specific evidence remains limited or context-dependent [51,52,53,54].

Important controversies and diverging hypotheses include: reliance on DXA versus morphology-direct endpoints for evaluating “hypertrophy”; whether leucine alone versus EAA mixtures or high-quality whole proteins are optimal for stimulating MPS and supporting hypertrophy in trained adults; the extent to which creatine-related gains reflect true myofibrillar accretion versus fluid shifts in early phases; the magnitude and conditions of HMB efficacy (free-acid versus calcium salt; trained versus untrained; energy status); and inconsistent effects of nitrate/citrulline on strength and hypertrophy despite plausible vascular mechanisms [55,56,57,58,59].

Purpose and significance - this article is a narrative review that integrates mechanistic plausibility with evidence from randomized and controlled trials reporting morphology-direct outcomes assessed by ultrasound and MRI. By privileging direct imaging of skeletal muscle hypertrophy over body-composition surrogates, it delineates the contexts in which supplementation exerts reliable effects. The synthesis organizes protein and essential amino acids, creatine, HMB, and adjuncts into a tiered conceptual framework that connects mechanistic pathways with morphological outcomes. In doing so, it provides both a critical appraisal of current evidence and a practical model for guiding future research and application in resistance-trained populations.

Main aim and principal take-home conclusions - based on mechanistic plausibility and morphology-anchored trials, we contend that adequately dosed protein/EAA forms the foundation for hypertrophy-oriented supplementation; creatine plausibly amplifies growth indirectly by enabling higher training volume/quality over time; HMB may offer context-dependent benefits under specific stressors; and evidence for adjuncts remains provisional for direct morphological change, though they may facilitate training quality and continuity. We also argue for standardized morphological assessments in future trials to improve comparability and synthesis.

Working hypotheses guiding this review (stated a priori):

H1. Morphology-direct endpoints (ultrasound/MRI thickness or cross-sectional area) are more specific indicators of hypertrophy in trained adults than lean-mass surrogates.

H2. Protein/EAA support hypertrophy primarily via MPS; consistent morphology-level benefits are most likely when baseline intake or per-meal leucine exposure is insufficient.

H3. Creatine contributes to hypertrophy predominantly indirectly through improved training volume/quality, with effects emerging over adequately long, progressive programs.

H4. HMB’s benefits, if present, are condition-dependent (e.g., high training load, energy deficit) and attenuated in eucaloric, well-trained conditions.

H5. Adjuncts (omega-3, citrulline/nitrates, collagen) are more likely to act as facilitators of training and recovery than as direct drivers of morphological change.

2. Materials and Methods

The strength of any integrative review lies not only in the interpretation of findings but also in the transparency of its methodological framework. Because conclusions about supplementation and hypertrophy are highly sensitive to how evidence is gathered and weighted, it was essential to define clear inclusion criteria, extraction strategies, and appraisal procedures. In this context, the present article was designed as a narrative review, informed by mechanistic considerations and privileging morphology-direct endpoints (ultrasound/MRI) as primary outcomes. Eligible evidence consisted of randomized or controlled trials in adults undergoing resistance training, with a minimum intervention duration of six weeks. Relevant studies were identified through a structured multi-database search (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science) up to 1 September 2025. Risk of bias was appraised qualitatively using the Cochrane RoB 2 domains to contextualize trial-level interpretability. No preregistered protocol was available, and no meta-analysis or quantitative pooling was attempted. This methodological framework was chosen to provide a coherent synthesis that integrates mechanistic plausibility with direct imaging evidence, while recognizing the heterogeneity and limited density of available trials. The present section therefore details the conceptual framework guiding the review, the eligibility rules used to select trials, the sources and search terms employed, and the procedures adopted to evaluate study quality and risk of bias. By outlining these steps explicitly, the review seeks to provide a reproducible pathway from the existing literature to the conclusions drawn in the preceding sections.

2.1. Conceptual Framework

To ensure consistency in the extraction and interpretation of evidence, a conceptual framework was predefined linking supplement classes to mechanistic modules and morphology-direct outcomes. The framework delineates five modules—anabolic signaling and muscle protein synthesis (MPS), energetic support and training volume/quality, anti-catabolic control, mechanotransduction, and connective-tissue adaptation—mapped onto ultrasound/MRI endpoints (muscle thickness or cross-sectional area). By operationalizing supplements, mechanisms, and endpoints within a single scheme, the framework minimized ad hoc judgments across heterogeneous trials and provided a uniform interpretive lens.

Figure 1 presents this analytical map, situating supplement classes within mechanistic pathways and linking them to morphology-direct outcomes. The figure functions as a methodological guide, clarifying how diverse interventions were organized into a coherent interpretive structure.

Directed graph linking supplement classes (Protein/EAA; Creatine; HMB; Omega-3; Citrulline/Nitrates; Collagen) to mechanistic modules—MPS/mTORC1 (anabolic signaling), phosphocreatine buffering & perfusion (energetic support/training volume), proteolysis/autophagy attenuation (anti-catabolic control), integrin/FAK-MAPK and related axes (mechanotransduction), connective-tissue adaptation—and to morphology-direct outcomes (ultrasound/MRI thickness; cross-sectional area). Solid arrows indicate primary mechanisms, dashed arrows indicate context-dependent links.

2.2. Scope and Eligibility

Scope - the primary scope of this review was to evaluate the evidence on nutritional supplementation for skeletal muscle hypertrophy in adults undergoing resistance training, with an emphasis on trials reporting morphology-direct outcomes (ultrasound or MRI). The review aimed to integrate mechanistic plausibility with empirical findings, distinguishing foundational supplements from conditional or adjunctive strategies.

Eligibility criteria were applied a priori to ensure consistency in evidence selection, addressing study design, intervention duration, participant characteristics, outcome measures, and the rationale for the supplement classes included:

Study design—Inclusion/Exclusion - eligible evidence comprised randomized or controlled trials in healthy adults that combined nutritional supplementation with resistance training. Excluded were observational designs, case reports/series, uncontrolled pilots, pharmacological agents, pediatric or clinical populations, and trials whose outcomes were unrelated to skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Trials reporting only body-composition surrogates were not considered primary evidence.

Minimum intervention duration - interventions shorter than six weeks were excluded a priori, on the premise that such durations are typically insufficient to capture morphology-direct adaptations to resistance training plus supplementation.

Participants - the target population was healthy adults. Both untrained and resistance-trained cohorts were eligible; however, trained populations were emphasized due to their higher relevance to hypertrophy-oriented supplementation and the greater need for morphology-level sensitivity in this group.

Outcomes and role of surrogates - primary outcomes were direct imaging endpoints of hypertrophy—ultrasound or MRI measures of muscle thickness or cross-sectional area. Body-composition surrogates (e.g., DXA, BIA) were extracted only as supportive context, given their limited specificity for contractile tissue and susceptibility to fluid/glycogen shifts.

Rationale for supplement classes - the scope was restricted to supplement classes with clear mechanistic plausibility for hypertrophy and widespread practice relevance in resistance-training settings:

Protein/EAA (leucine)—direct stimulation of MPS via mTORC1-linked mechanisms (leucine “threshold”/per-meal distribution);

Creatine monohydrate—energetic support (PCr buffering) enabling higher training volume/quality with downstream morphological accrual;

β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate (HMB)—anti-catabolic candidate with putative benefit under high training stress or energy deficit;

Adjuncts (omega-3, citrulline/nitrates, collagen )—plausible facilitators (anabolic sensitivity/recovery, perfusion/tolerance, connective-tissue adaptation), for which morphology-direct evidence remains limited or context-dependent.

Training Status (Operational Definitions) - we operationalized training status a priori as follows: Trained = ≥6 months of supervised resistance training or an equivalent structured program; Untrained = <3 months of resistance training or irregular/unstructured exposure. Where mixed cohorts were included, data extraction and narrative synthesis were stratified by training status whenever possible.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

Relevant studies were identified by searching major electronic databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science. The complete list of the 46 included randomized controlled trials is provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

The search combined controlled vocabulary and free-text terms related to supplementation and hypertrophy. Search strings used Boolean operators linking supplement terms (e.g., “protein,” “essential amino acids,” “leucine,” “creatine,” “β-hydroxy-β-methylbutyrate,” “HMB,” “omega-3,” “citrulline,” “nitrate,” “collagen”) with resistance training and outcome terms (e.g., “resistance training,” “strength training,” “hypertrophy,” “muscle thickness,” “cross-sectional area,” “ultrasound,” “MRI”).

No lower time limit was imposed, and the search covered the literature up to the present day. No language restrictions were applied at the search stage, but only studies published in English were retained for synthesis. In addition to database searches, reference lists of pertinent reviews and included trials were screened manually to identify additional eligible studies.

This strategy was designed to capture both morphology-direct evidence (ultrasound or MRI) and studies reporting surrogate outcomes (DXA, BIA) that could be used as supportive context. All retrieved records were screened against the predefined eligibility criteria.

Search Parameters and Flow – the final literature search was conducted up to 1 September 2025. Boolean expressions combined supplement-related terms with resistance training and morphology-direct endpoints, for example: (protein OR amino acids OR leucine OR creatine OR HMB OR beta-hydroxy-beta-methylbutyrate OR omega-3 OR collagen OR citrulline) AND (ultrasound OR MRI) AND (muscle thickness OR cross-sectional area OR CSA OR hypertrophy).

Operational definitions of training status were applied a priori:

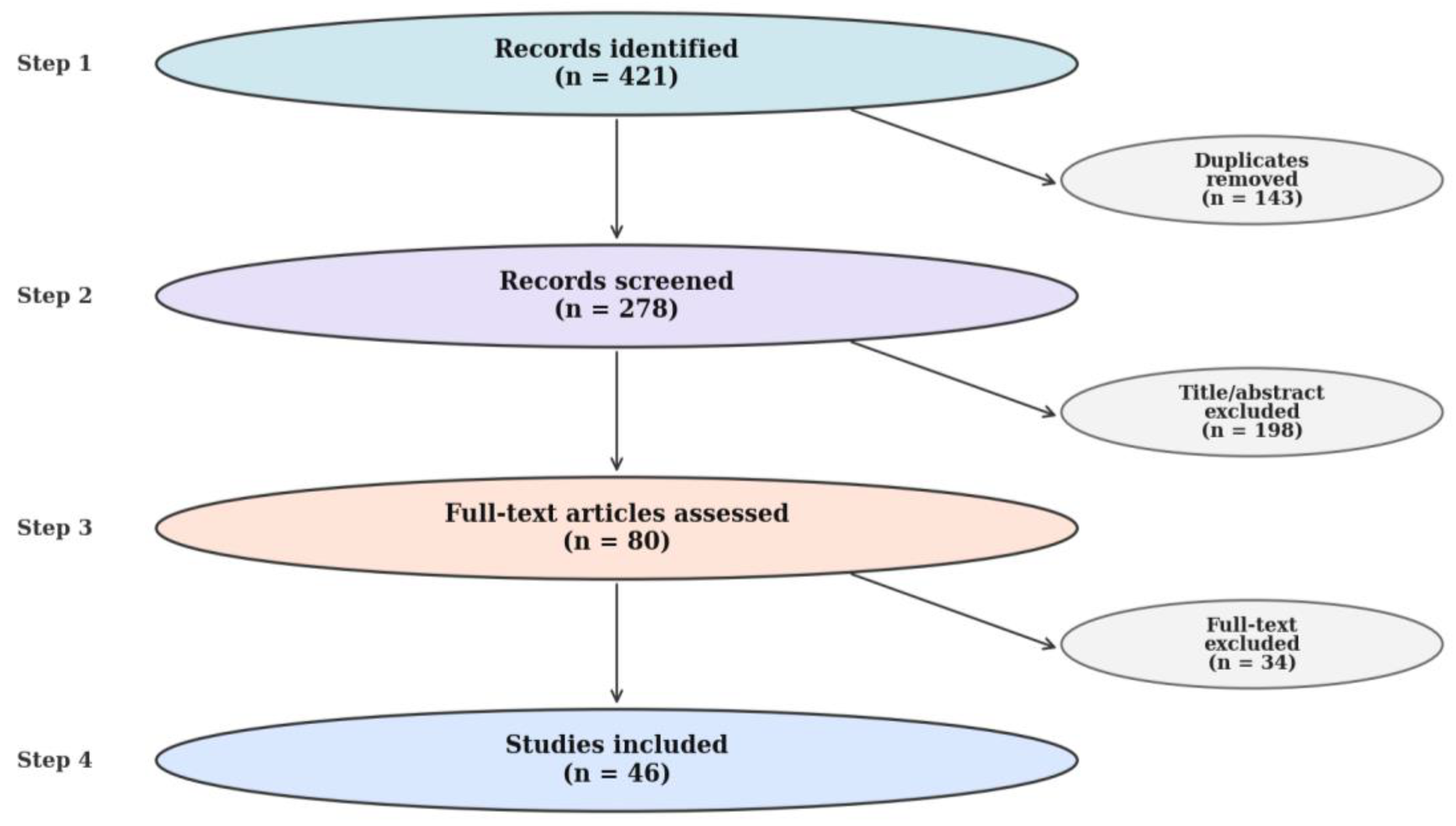

Screening followed a simplified PRISMA-lite process. Of 421 records initially retrieved, 143 duplicates were removed, 198 were excluded after title/abstract review, and 80 full texts were assessed. 34 full-text reports were excluded for predefined reasons: duration <6 weeks (n = 12), no morphology-direct outcomes (n = 10), ineligible population/design (n = 8), and other reasons (n = 4). Ultimately, 46 trials were included for synthesis, comprising 28 with ultrasound, 12 with MRI, and 6 with both methods. A summary of the study screening and selection procedure is presented in

Figure 2, which depicts the PRISMA-style flow from identification to final inclusion.

2.4. Study Selection and Data Extraction

Study selection followed the eligibility rules described before. Retrieved records were screened for relevance in two stages: title/abstract review followed by full-text evaluation. Only studies that met the predefined inclusion criteria—randomized or controlled design, adult participants, resistance training intervention, and morphology-direct outcomes (ultrasound or MRI)—were retained. Trials reporting exclusively on body-composition surrogates (DXA or BIA) were extracted separately as contextual evidence.

For each included study, data were extracted on sample size and characteristics (age, sex, training status), intervention features (supplement type, dosing, timing, duration), and training program parameters (volume, intensity, progression, supervision). Outcome information included imaging modality (US or MRI), anatomical site, reliability metrics where reported, and primary morphology results. Contextual endpoints such as lean body mass or strength performance were also noted when available.

Data extraction was performed manually, with cross-checking against original articles to minimize transcription error. Given the narrative nature of this review, no quantitative pooling was undertaken; instead, extracted data were synthesized qualitatively and organized by supplement class, mechanistic rationale, and consistency of morphology outcomes.

2.5. Quality Appraisal and Risk of Bias (RoB 2)

We conducted a qualitative risk-of-bias appraisal of randomized controlled trials that reported direct imaging outcomes of hypertrophy (ultrasound/MRI/CT). Risk of bias was judged qualitatively using the Cochrane RoB 2 domains (randomization process; deviations from intended interventions; missing outcome data; outcome measurement; selection of the reported result). We did not compute domain scores or meta-analytic weights; instead, we provide an overall judgment (Low/Some concerns/High) per study to contextualize effect estimates.

2.6. Evidence Appraisal and Synthesis Approach

Given the narrative design, results were synthesized qualitatively, organized by supplement class and mapped onto mechanistic modules (anabolism/MPS, energetic support, anti-catabolic actions, mechanotransduction, connective tissue adaptation). Patterns of convergence and inconsistency were highlighted, and contextual moderators (baseline protein intake, training status, program duration, imaging standardization) were noted to frame interpretation. This synthesis approach allowed the evidence base to be appraised systematically in structure, while remaining narrative in execution.

3. Results

Direct imaging of hypertrophy offers a more precise window into the adaptations produced by resistance training combined with nutritional supplementation than whole-body composition surrogates such as DXA or BIA. Trials employing ultrasound or MRI provide regional measures of muscle thickness or cross-sectional area, which are considered the most specific indices of myofibrillar accretion in vivo. Although relatively few compared with studies reporting lean mass, these trials are essential for disentangling true hypertrophy from water or glycogen-related changes.

Across the literature, designs vary considerably in training status (untrained novices vs. experienced lifters), intervention length, dosing strategies, and imaging protocols. Short interventions may capture only early compositional shifts, whereas programs of ≥8–12 weeks allow potential divergence between supplement and control groups to manifest in morphology. At the same time, methodological issues—such as single-site ultrasound measures or small sample sizes—limit interpretability.

Despite these constraints, imaging-based studies form the empirical backbone for understanding whether supplementation alters hypertrophy beyond the effects of progressive training. They reveal both convergent evidence (e.g., protein and essential amino acids when baseline intake is inadequate; creatine as a facilitator of training volume) and points of debate (e.g., conditional utility of HMB; weak or inconsistent evidence for adjuncts such as omega-3, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen).

Table 1 summarizes the principal randomized or controlled trials that incorporated direct imaging endpoints, collating participant characteristics, training protocols, supplementation strategies, and reported hypertrophy outcomes.

Although imaging-based trials offer the clearest lens on hypertrophy,

Table 1 also highlights the unevenness of the evidence base. Most interventions remain short in duration, small in scale, and heterogeneous in methodology, which constrains interpretation. This scarcity of robust, morphology-direct studies underscores why supplement-specific sections must integrate mechanistic reasoning alongside trial outcomes, rather than relying on imaging data alone.

Table 2 distills the inferential content of the imaging trials—emphasizing the magnitude and direction of morphological adaptations, the comparative balance between supplement and control groups, and the methodological safeguards (reliability indices, blinding, risk-of-bias) that condition the interpretability of these outcomes.

The pattern that emerges is one of pronounced heterogeneity: clear morphological advantages appear only in a subset of interventions, while many others yield negligible or equivocal outcomes. Such contrasts emphasize that supplementation effects cannot be abstracted from their methodological context—duration of training, imaging fidelity, and trial quality remain decisive in shaping whether hypertrophy signals can be discerned.

3.1. Proteins and Essential Amino Acids (EAA; Leucine)

Mechanistic anchor - high-quality proteins and essential amino acids (EAA), with sufficient leucine exposure, stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS) through translational control and mTORC1-related signaling, thereby supporting myofibrillar accretion when resistance training provides the mechanical stimulus. The “leucine threshold” concept indicates per-meal leucine requirements for robust MPS, particularly relevant in trained adults exposed to repeated anabolic stimulation.

Morphology-direct evidence - trials in trained participants report increases in muscle thickness or cross-sectional area when protein/EAA intake is inadequate at baseline or poorly distributed, with diminishing returns once per-meal leucine targets and daily intake are consistently met. Studies using ultrasound or MRI at standardized sites (e.g., vastus lateralis, elbow flexors) yield more coherent hypertrophy signals than those relying solely on whole-body composition.

Dose/timing patterns and moderators - effective regimens typically provide ~0.3 g·kg−1·meal−1 of high-quality protein (or ~2–3 g leucine per meal) distributed across 3–5 meals and timed around resistance-training sessions. Greater benefits are observed in individuals with lower habitual intake, suboptimal per-meal leucine exposure, or insufficient post-exercise provision. Sex, training status, and program duration moderate effect sizes, while consistency in imaging site selection further influences detectability.

Key Caveat - morphology-direct evidence confirms that supplementation is beneficial primarily when baseline intake or per-meal leucine distribution is inadequate. Once daily protein consistently exceeds ~1.6–2.0 g·kg−1·day−1, further supplementation rarely translates into additional hypertrophy, reflecting a ceiling effect. Variability in habitual diet, protein timing, and participant sex or training status explains much of the heterogeneity across trials.

Summary (H1, H2) - Consistent with H1, imaging endpoints confirm that ultrasound and MRI detect morphological gains more specifically than body-composition surrogates. In line with H2, the evidence supports protein/EAA supplementation as a foundation for hypertrophy, with morphology-direct benefits most pronounced under conditions of inadequate intake or distribution, and attenuated once nutritional provision is already optimized.

3.2. Creatine Monohydrate

Mechanistic anchor - creatine increases phosphocreatine (PCr) availability, improving high-intensity set quality and cumulative training volume, which can translate into hypertrophy over weeks of progressive RT. Early mass changes may include water shifts, but morphology-direct imaging discriminates myofibrillar gains from fluid alterations.

Morphology-direct evidence - in trained adults following well-controlled RT (≥8–12 weeks), several studies report small-to-moderate increases in muscle thickness/CSA (e.g., elbow flexors, quadriceps), while others find neutral effects when programs are short, under-progressed, or when endpoints rely on body-composition surrogates. Inter-individual variability (baseline intramuscular creatine, fiber type distribution, diet) partly explains mixed findings.

Dose/timing patterns and moderators - common regimens include loading (e.g., ~0.3 g·kg−1·d−1 for 5–7 days) followed by 3–5 g·d−1, or simply 3–5 g·d−1 without loading. Pairing creatine with adequate protein/EAA and progressive RT appears to maximize morphology-level changes. Imaging at consistent anatomical landmarks enhances detectability.

Key Caveat - early increases in body mass during creatine loading are largely attributable to fluid retention and osmotic shifts rather than myofibrillar accretion. Ultrasound and MRI provide the necessary resolution to distinguish these transient effects from structural hypertrophy. Consistent morphology-direct benefits emerge only in ≥8–12-week progressive programs, with inter-individual variability (baseline intramuscular creatine, diet, fiber type distribution) further moderating responsiveness. This chronological sequence clarifies why many short-term interventions report neutral morphological outcomes. Ergogenic benefits in training tolerance and volume accrue earlier, while measurable hypertrophy emerges only with sustained overload across multiple months. Interpreting creatine as a performance amplifier with delayed morphological expression reconciles the apparent discrepancy between early neutral findings and long-term imaging evidence.

Summary (H1, H3) - Consistent with H1, imaging outcomes discriminate creatine-related adaptations from early fluid shifts, showing morphological gains when interventions are sufficiently long. In line with H3, creatine’s primary contribution is indirect—enhancing training volume and quality—rather than direct anabolic signaling.

3.3. β-Hydroxy-β-Methylbutyrate (HMB)

Mechanistic anchor - HMB may attenuate muscle protein breakdown (ubiquitin–proteasome/autophagy) and support membrane integrity, potentially improving net protein balance under high training stress or energy deficit. Free-acid versus calcium-salt forms have been differentially studied, with distinct absorption kinetics.

Morphology-direct evidence - in well-trained, eucaloric settings, ultrasound/MRI outcomes are inconsistent, with neutral findings being common; context-specific benefits are reported under novel/high-load microcycles, during aggressive training blocks, or when energy availability is reduced.

Dose/timing patterns and moderators - typical dosing is 3 g·d−1, sometimes periodized around high-stress phases. Training status, energy intake, and program design appear to moderate outcomes; imaging standardization remains limited across studies.

Key Caveat - HMB’s effects are context-dependent: trials in high-stress or energy-deficit conditions are more likely to report benefits, whereas well-fed, resistance-trained cohorts often show null outcomes. Formulation appears relevant, with free-acid HMB demonstrating higher bioavailability than calcium salt, although evidence remains inconsistent. Several positive studies were industry-sponsored, and heterogeneous imaging protocols further constrain confidence in reported hypertrophy effects.

Formulation and bias considerations - positive signals in the literature have been disproportionately associated with the free-acid formulation, which shows faster uptake and higher plasma concentrations than the calcium salt. However, several of these favorable trials were industry-sponsored, raising concerns about selective reporting and publication bias. Neutral or negative findings are more common in independently funded studies, particularly those using calcium salt formulations or well-fed, resistance-trained populations. This pattern underscores that both formulation and sponsorship context must be weighed when interpreting reported hypertrophy effects.

Summary (H1, H4) - Consistent with H1, morphology-direct outcomes clarify that hypertrophy effects of HMB are absent in many eucaloric, trained contexts. In line with H4, benefits emerge under high training stress or energy deficit, supporting a conditional rather than general role.

3.4. Adjuncts: Omega-3 Fatty Acids, Citrulline/Nitrates, Collagen

Adjunct compounds such as omega-3 fatty acids, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen have been investigated in RCTs with claims of hypertrophic or anabolic potential. Unlike protein, creatine, or HMB, these interventions rarely yielded significant CSA/MT increases. Their plausible contribution lies in indirect pathways—sensitizing anabolic signaling, improving perfusion and tolerance, or supporting connective-tissue remodeling—rather than directly driving hypertrophy.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids - proposed to sensitize anabolic signaling and modulate membrane/inflammation biology, omega-3 supplementation shows mixed morphology-direct findings in trained adults; any benefits likely depend on adequate protein and progressive overload.

Mechanistic anchor. Omega-3 fatty acids (EPA/DHA) have been hypothesized to enhance anabolic sensitivity through membrane fluidity, inflammatory modulation, and mTOR-related signaling.

Morphology-direct evidence. Trials with ultrasound or MRI endpoints are scarce and heterogeneous. Most show no direct increases in CSA or MT when protein intake and training are already adequate, though minor effects have been reported in older or malnourished populations.

Dosing. Typical protocols use 1–3 g/day of combined EPA+DHA, taken chronically.

Key Caveat. Omega-3 supplementation is unlikely to produce hypertrophy in healthy, resistance-trained adults; benefits may instead be restricted to recovery or metabolic health contexts.

Citrulline and Nitrates - by enhancing NO-mediated perfusion and possibly exercise tolerance, these compounds may improve set quality; morphology-direct evidence is inconsistent, with positive signals more often seen in performance outcomes than in thickness/CSA.

Mechanistic anchor. Citrulline and dietary nitrates target nitric oxide pathways, increasing vasodilation, perfusion, and training tolerance.

Morphology-direct evidence. Evidence for hypertrophy endpoints is virtually absent; most studies evaluate endurance capacity, fatigue resistance, or acute performance, not CSA or MT.

Dosing. Typical regimens: 6–8 g/day L-citrulline or nitrate-rich foods/beverages, usually administered pre-exercise.

Key Caveat. The lack of direct hypertrophy outcomes means that any putative morphological benefits remain speculative, and these compounds are better viewed as acute performance aids.

Collagen - targeting connective-tissue adaptation (with vitamin C co-ingestion in some protocols), collagen appears to indirectly support training continuity and load progression rather than drive direct muscle CSA gains; morphology endpoints are limited or neutral in trained adults.

Mechanistic anchor. Collagen peptides, especially with vitamin C co-ingestion, are proposed to enhance connective tissue remodeling and tendon integrity, potentially supporting load transfer during resistance training.

Morphology-direct evidence. Imaging trials report improvements in tendon CSA and mechanical properties, but direct skeletal muscle hypertrophy is minimal compared with whey protein controls.

Dosing. Standardized at 10–15 g/day collagen peptides plus 50 mg vitamin C, usually peri-exercise.

Key Caveat. Collagen is better positioned as a facilitator of joint and tendon health, not as a primary driver of muscle CSA.

Summary (H1, H5) - Consistent with H1, imaging endpoints highlight the absence of robust morphology-specific effects for adjuncts. In line with H5, their plausible contribution is to facilitate training tolerance or recovery, not to act as primary drivers of hypertrophy.

3.5. Evidence Synthesis Across Supplement Classes

Taken together, the supplement classes reviewed in

Section 2.1–2.4 reveal both convergent and divergent patterns. Despite distinct mechanistic anchors—protein and EAA targeting MPS, creatine enhancing workload through phosphocreatine buffering, HMB attenuating catabolic signaling, and adjuncts supporting recovery or connective-tissue remodeling—morphology-direct evidence consistently highlights the contextual nature of hypertrophy outcomes. Interventions with insufficient duration, non-progressive training, or participants already near ceiling thresholds for protein or creatine rarely produce measurable differences in muscle thickness or CSA.

Cross-comparison also reveals that the evidentiary hierarchy is uneven across supplement categories. Protein/EAA and creatine demonstrate the most reliable morphology-direct benefits, though both depend on baseline intake, distribution, or training progression. In contrast, HMB remains conditional, with outcomes driven by stress or energy status, and adjuncts such as omega-3 fatty acids, citrulline/nitrates, or collagen provide primarily indirect contributions—facilitating tolerance, recovery, or connective-tissue adaptation rather than driving hypertrophy per se.

This uneven hierarchy is further complicated by moderator variables that shaped the magnitude and direction of outcomes. Protein and EAA benefits clustered in untrained or undernourished cohorts, whereas trained individuals with optimized intake often showed attenuated or null responses. Creatine-related gains appeared most consistent in young male participants under progressive overload, with smaller or inconsistent effects in mixed-sex or older samples. HMB demonstrated conditional utility, particularly under caloric deficit or deliberate overreaching, but largely neutral effects in eucaloric, resistance-trained settings. Adjuncts such as omega-3 fatty acids occasionally yielded small signals in older or nutritionally compromised populations yet remained neutral in young, healthy adults. Taken together, these moderators underscore that hypertrophy responses cannot be abstracted from sex, training background, or energy balance.

Few trials, however, reported performance outcomes and workload variables in parallel with imaging, limiting the ability to determine whether supplementation effects were mediated by enhanced training tolerance or by direct anabolic signaling.

To provide a concise comparative overview,

Table 3 synthesizes these patterns. It maps each supplement class to its mechanistic node, typical protocol, morphology-direct evidence, consistency rating, and key moderators. This integrative perspective underscores that supplementation should be considered not as isolated “anabolic switches,” but as context-dependent tools whose value depends on baseline nutrition, training program design, and outcome specificity.

Table 4 situates the supplement classes within the quantitative landscape of imaging trials, outlining trial density, intervention length, and the typical magnitudes of morphological divergence

Table 4 makes visible the quantitative stratification: protein and creatine show reproducible gains of 3–7% in morphological indices when studied under sufficient duration and with appropriate baselines; HMB demonstrates a narrow window of efficacy under stress or deficit; and adjuncts contribute negligible direct hypertrophy, with collagen acting more on tendon than on muscle. This hierarchy is empirical, shaped by trial density, duration, and outcome sensitivity.

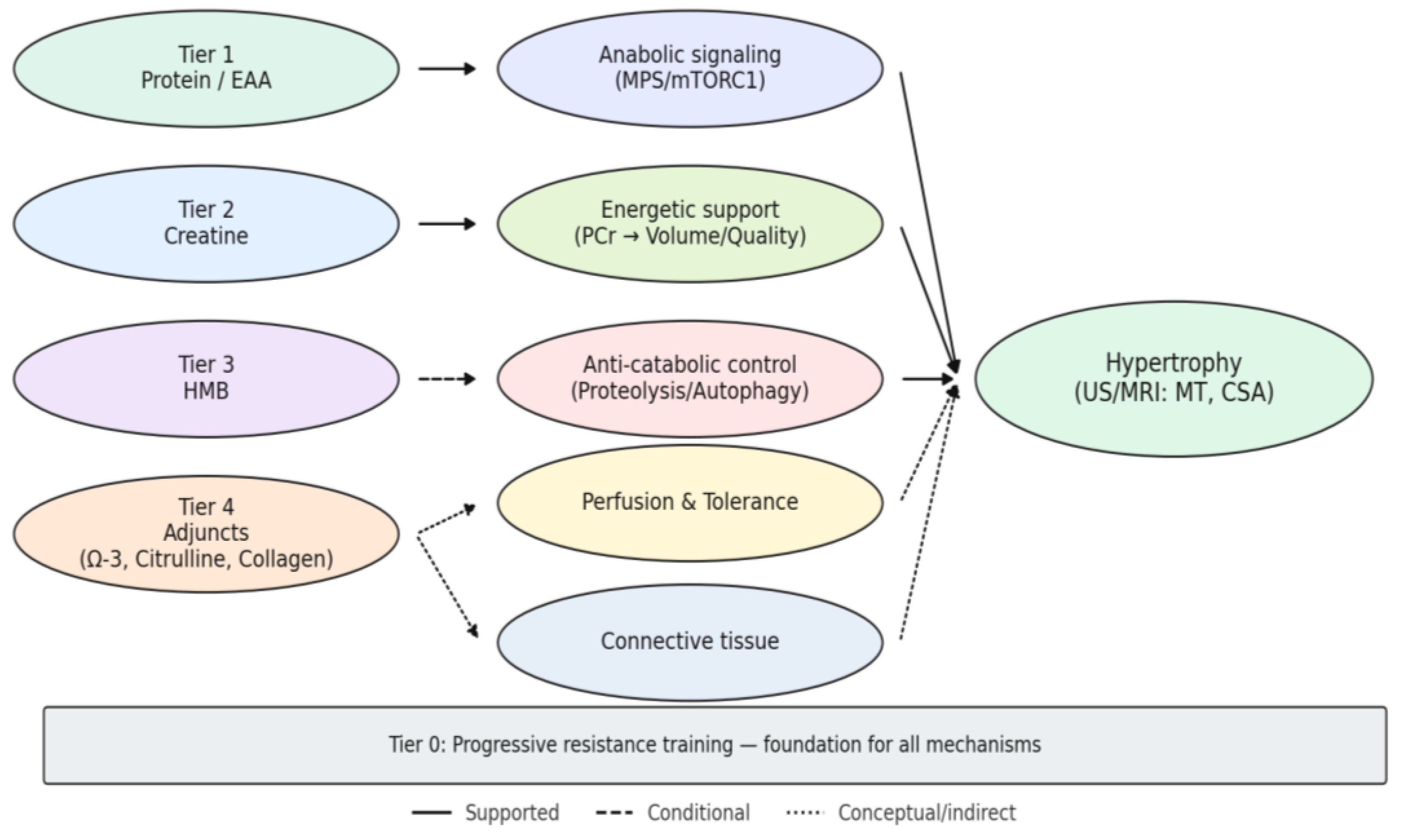

The quantitative contrasts outlined resolve, in visual form, into the tiered framework depicted in

Figure 3, where mechanistic pathways and empirical weight are integrated into a coherent map of supplementation and hypertrophy.

The diagram arranges supplement classes into hierarchical tiers, with progressive resistance training (Tier 0) as the foundation. Tier 1 (protein and essential amino acids) anchors anabolic signaling through mTORC1 and translational control, providing the most consistent morphological gains when baseline intake or leucine distribution is suboptimal. Tier 2 (creatine) amplifies growth indirectly by sustaining phosphocreatine resynthesis, enabling higher training volume and quality; morphological effects emerge only in programs of sufficient length and progression. Tier 3 (HMB) operates as a conditional anti-catabolic agent, with detectable hypertrophy signals largely confined to contexts of overreaching or energy deficit. Tier 4 (adjuncts such as omega-3 fatty acids, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen) contributes primarily as facilitators of training tolerance, vascular support, or connective-tissue adaptation rather than direct drivers of hypertrophy. Line thickness reflects the strength of empirical support (thicker = stronger, thinner = weaker), while line style differentiates robust (solid), conditional (dashed), and conceptual (dotted) pathways.

Together, the figure integrates mechanistic plausibility with imaging evidence (US/MRI: muscle thickness, cross-sectional area), situating supplementation within a coherent hierarchy of certainty.

This integrated mapping motivates the working hypotheses (H1–H5) and frames when and why each tier is expected to translate into measurable morphological change.

3.6. Cross-Walk to Working Hypotheses (H1–H5)

H1 (Specificity of ultrasound/MRI) - across supplement classes, ultrasound and MRI consistently provided more specific indexing of hypertrophy than body-composition surrogates (DXA, BIA). Studies relying on imaging demonstrated clearer discrimination between transient changes (e.g., fluid shifts with creatine) and structural hypertrophy, confirming that morphology-direct methods are superior for mechanistic inference.

H2 (Protein and leucine thresholds) - evidence strongly supported H2: protein and EAA supplementation yielded measurable hypertrophy only when baseline intake or per-meal leucine provision was inadequate. Once thresholds of ~1.6–2.0 g·kg−1·day−1 and 2–3 g leucine/meal were met, additional supplementation produced little further benefit, reflecting a ceiling effect.

H3 (Creatine as a volume amplifier) - consistent with H3, creatine’s effect on muscle size was mediated predominantly through enhanced training volume and quality. Morphology-direct gains were evident only in sufficiently long and progressive programs (≥8–12 weeks), with negligible outcomes in short or under-progressed interventions.

H4 (Conditional role of HMB) - evidence for HMB aligned with H4: benefits were most apparent under high training stress or energy deficit, while eucaloric, resistance-trained contexts typically showed null effects. Formulation (free-acid vs. calcium salt) and sponsorship bias contributed to heterogeneity, underscoring the conditional and contested status of HMB as a hypertrophy agent.

H5 (Adjuncts as facilitators) - in line with H5, adjuncts such as omega-3 fatty acids, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen functioned primarily as facilitators of training tolerance, recovery, or connective-tissue remodeling. Imaging rarely demonstrated direct CSA changes, but these compounds may sustain training continuity and indirectly support hypertrophy trajectories.

Overall, the cross-walk confirms that morphology-direct outcomes sharpen the appraisal of each hypothesis, with H1, H2, and H3 strongly supported, H4 conditionally supported, and H5 reframed as indirect facilitation rather than direct hypertrophy.

3.7. Quality and Risk-of-Bias Snapshot (Rolled-Up)

The methodological quality of the imaging trials was moderate, with several recurrent sources of risk of bias. Randomization procedures were usually described as adequate, yet the reporting of allocation concealment and blinding—both of participants and outcome assessors—was inconsistent, leaving scope for performance and detection bias. Sample sizes were generally modest, amplifying the risk of random error and limiting external validity. Although ultrasound protocols were frequently standardized, reliance on single anatomical sites and operator-dependent measurements introduced potential measurement bias. MRI-based assessments offered superior robustness in terms of reliability and reproducibility, but such trials were relatively scarce and unevenly distributed across supplement classes. Attrition bias was low in most studies, yet selective reporting of outcomes and incomplete disclosure of trial protocols could not be excluded, particularly in industry-sponsored interventions. Collectively, these limitations constrain the strength of inference and emphasize the need for preregistered protocols, larger and better-powered cohorts, and harmonized imaging practices to improve comparability in future research.

Table 5 summarizes trial-level risk-of-bias assessments across included studies with morphology-direct endpoints.

4. Discussion

The synthesis of mechanistic reasoning with morphology-direct evidence allows a more nuanced appraisal of how nutritional supplements contribute to skeletal muscle hypertrophy in resistance-trained adults. Unlike traditional reviews that emphasize lean mass or performance outcomes, the present analysis deliberately privileges ultrasound and MRI data, which capture myofibrillar accretion with greater specificity. This approach brings into sharper focus both the convergences and the contradictions within the literature. Convergences emerge where protein/EAA intake, creatine supplementation, or condition-specific use of HMB align with expected biological pathways, whereas contradictions arise from short trials, unstandardized imaging, and the scarcity of robust evidence for adjuncts. Such contrasts do not merely reflect gaps in experimental design; they delineate the frontier between what can be stated with confidence and what remains provisional. In this respect, the discussion moves beyond a catalog of results to examine their broader implications: how supplementation should be conceptualized relative to baseline diet and training status, how mechanistic plausibility intersects with trial quality, and how methodological rigor will determine the trajectory of future research in this field.

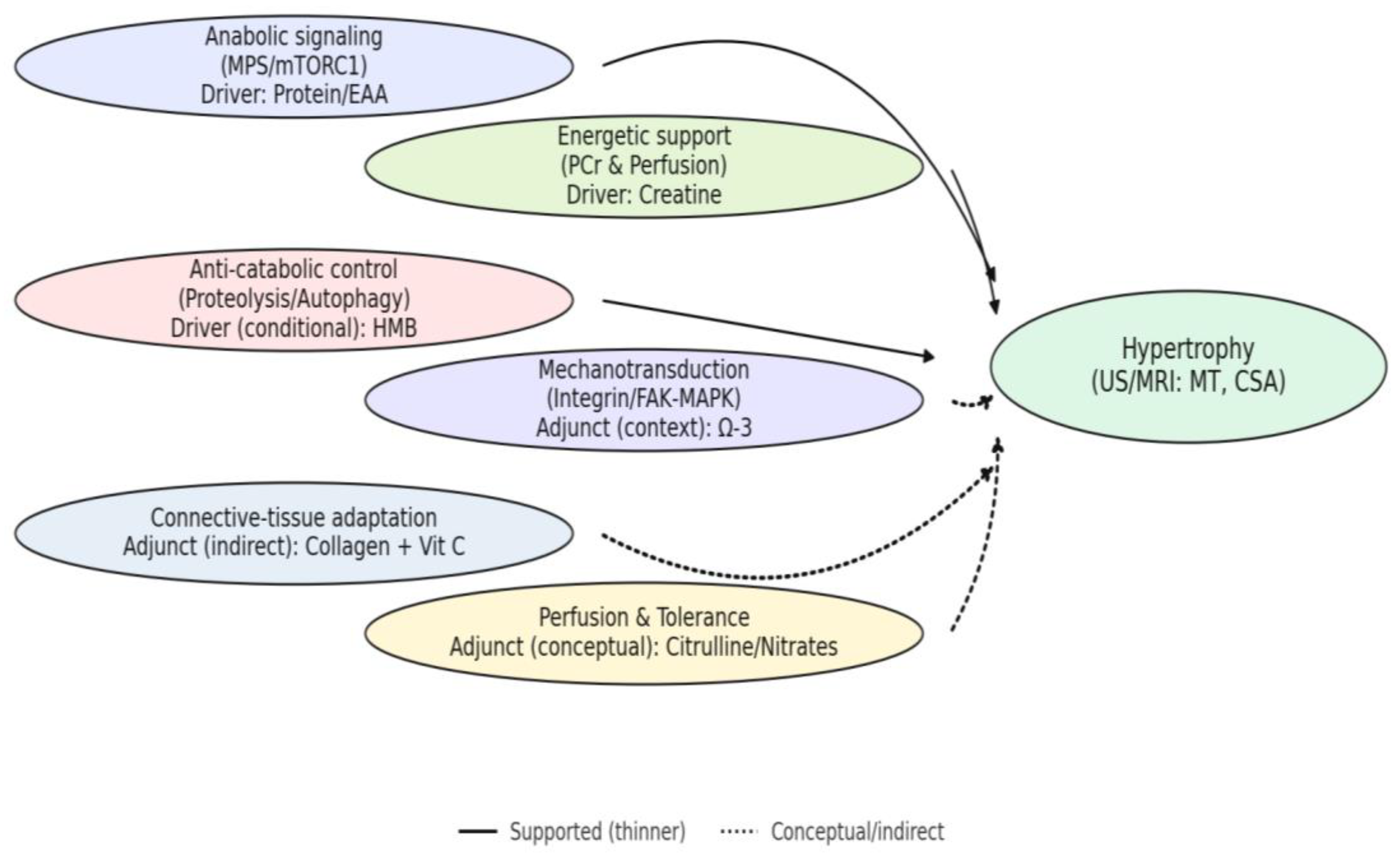

Figure 4 provides the mechanism-centric map used to interpret the following arguments (H1–H5), linking supplement-driven modules to morphology-direct outcomes (US/MRI: MT, CSA).

This mechanism-centric view clarifies context-dependent effects (e.g., anti-catabolic and adjunct pathways) and guides the interpretation of heterogeneous findings across studies.

4.1. Integrating Findings with the Working Hypotheses (H1–H5)

Morphology-Direct Endpoints (Linkage to H1) - the comparison between imaging outcomes and lean-mass surrogates clearly supports H1: ultrasound and MRI provide more specific indexing of hypertrophy than DXA or BIA. This distinction is not trivial, as early increases in lean mass often reflect water or glycogen accretion, whereas imaging captures actual myofibrillar growth. Nevertheless, even imaging protocols vary widely in site selection, assessor training, and reproducibility, which introduces noise into the estimates. Single-site ultrasound can over- or under-represent adaptation depending on the chosen muscle group, while MRI, although more robust, is costly and therefore underused. The implication is that future trials must standardize imaging landmarks and report reliability indices to allow cross-study comparison. Without such standardization, the methodological strength of imaging remains underexploited despite its superiority over compositional surrogates.

Protein/EAA as Foundation (Linkage to H2) - findings strongly confirm H2, as protein and essential amino acids consistently act as the nutritional foundation for hypertrophy. Morphology-direct benefits are most evident when baseline intake is inadequate or when per-meal leucine exposure falls below the threshold required to maximize MPS. Once intake exceeds ~1.6–2.0 g·kg−1·day−1, further supplementation rarely translates into measurable morphological gains, revealing a ceiling effect. This explains why novice or undernourished cohorts show robust benefits, whereas trained athletes with optimized diets often display minimal or null responses. The nuance is crucial: without accounting for habitual intake and protein distribution, results can be misinterpreted as inconsistent or contradictory. Future trials should therefore stratify participants by baseline protein status to delineate responders and non-responders more clearly.

Creatine as Volume Amplifier (Linkage to H3) - the literature affirms H3 by showing that creatine rarely drives hypertrophy directly but exerts its influence via enhanced training volume and quality. Creatine supplementation sustains phosphocreatine resynthesis, delays fatigue, and enables greater workload across sessions, which over time translates into measurable gains in muscle size. Imaging evidence confirms this pathway only when interventions are sufficiently long (≥8–12 weeks) and progressive; shorter trials tend to report neutral outcomes, reflecting the lag between functional improvements and morphological accrual. A further complication is inter-individual variability: baseline intramuscular creatine levels, dietary patterns, and muscle fiber type composition all moderate responsiveness. This chronological sequence clarifies why early null findings contrast with later imaging evidence: osmotic water retention dominates in the first days, ergogenic improvements in training tolerance emerge within weeks, and only with sustained overload across months do creatine-related advantages manifest as measurable hypertrophy. The implication is that creatine should be conceptualized as a performance enhancer with secondary morphological consequences, not as a direct anabolic stimulus.

HMB as Conditional Agent (Linkage to H4) - support for H4 is conditional: HMB appears beneficial under high training stress, overreaching, or caloric deficit, but results are inconsistent in eucaloric, well-trained contexts. Mechanistically, HMB may reduce proteolysis and stabilize cell membranes, thereby preserving net protein balance during catabolic strain. Yet trials in trained athletes consuming adequate protein often report null morphology-direct effects, underscoring the context-dependence of supplementation. Formulation adds another layer of complexity: free-acid HMB demonstrates higher bioavailability than the calcium salt, and positive results have clustered disproportionately in trials using the free-acid form. However, many of these trials were industry-sponsored, raising concerns about selective reporting and publication bias. Neutral or negative findings are more frequent in independently funded work, particularly with calcium salt formulations. This asymmetry suggests that the apparent controversy surrounding HMB may derive as much from methodological and financial contingencies as from true biological inconsistency. Collectively, the evidence positions HMB as situational—potentially useful under stress or deficit, but not a universal tool for hypertrophy.

Adjuncts as Facilitators (Linkage to H5) - the evidence for H5 remains provisional. Omega-3 fatty acids, citrulline/nitrates, and collagen display plausible mechanistic rationales—ranging from enhanced anabolic sensitivity and perfusion to connective-tissue support—but direct imaging evidence in trained adults is scarce and inconsistent. Positive effects are more often observed on recovery, tolerance to training, or performance proxies rather than on CSA or muscle thickness per se. This pattern suggests that adjuncts should be considered facilitators, potentially enabling sustained training quality or reducing injury risk, rather than primary drivers of hypertrophy. Their value may therefore lie in integrated strategies where foundational nutrition and progressive overload are already in place. Future trials should clarify whether these compounds contribute indirectly by preserving training continuity or directly by augmenting morphological growth under specific contexts.

4.2. Practical Translation for Resistance-Trained Populations

The hierarchy of evidence derived from morphology-direct outcomes suggests a tiered model for supplementation in resistance-trained adults. At the foundation (Tier 0) remains progressive overload itself: consistent documentation of volume, intensity, and session density, ideally accompanied by site-specific imaging where feasible. No supplementation can substitute for inadequate training progression, and methodological precision in training design is as crucial as the supplements under study.

Building on this, Tier 1 encompasses protein and essential amino acids, which provide the nutritional base for hypertrophy. Practical translation aligns with ~0.3 g·kg−1 per meal, or 2–3 g leucine equivalents, distributed across three to five meals per day and timed around resistance training sessions. Benefits are particularly evident when baseline intake is below optimal, whereas in individuals already consuming >1.6–2.0 g·kg−1·day−1 of protein, effects may plateau.

Tier 2 is represented by creatine monohydrate, best conceptualized as a volume and quality amplifier. Dosing strategies of 3–5 g·day−1 (with or without a short loading phase) are sufficient to sustain phosphocreatine resynthesis and permit higher training workloads. Morphological adaptations typically emerge after several months of progressive training, consistent with its indirect pathway through enhanced performance rather than direct anabolic signaling.

Tier 3 covers condition-dependent adjuncts. HMB may be useful during high-load training blocks or energy deficit (~3 g·day−1), although expectations should remain moderate given mixed results in well-fed, trained populations. Omega-3 fatty acids can plausibly sensitize anabolic signaling or aid recovery, particularly where habitual intake of EPA and DHA is low. Citrulline and dietary nitrates may improve session quality via enhanced perfusion and tolerance, but morphology-specific evidence remains weak. Collagen peptides, often paired with vitamin C, appear more relevant to connective-tissue support than direct hypertrophy, yet may indirectly sustain training continuity.

Finally, quality and safety considerations apply across all tiers. Third-party testing, label accuracy, and individual tolerability remain essential, while supplementation strategies should always be integrated with total diet and periodized training. Conceptualized in this way, supplementation does not replace fundamental training principles but can support or amplify them under the right nutritional and physiological conditions.

4.3. Safety and Ethical Considerations

Beyond efficacy, the safety profile of nutritional supplements in athletic practice warrants equal attention. Reports have documented undeclared substances, mislabeled dosages, or contaminants in commercially available products, raising potential health risks and concerns regarding anti-doping compliance. While the present synthesis emphasized efficacy as captured by morphology-direct outcomes, the scarcity of long-term safety data—particularly in elite athletes—limits firm conclusions on chronic use. For this reason, independent replication, transparent labeling, and third-party testing are critical safeguards. Ethical considerations also extend to ensuring that supplements are positioned as adjuncts to, rather than replacements for, progressive training and balanced nutrition. Integrating efficacy with safety, regulatory oversight, and fair-play principles is essential to translate research findings into responsible sport practice.

4.4. Limitations, Measurement Issues, and Research Gaps

This present synthesis is narrative in design, without protocol registration or formal meta-analysis, and thus cannot provide pooled effect sizes or quantitative bias diagnostics. The emphasis has been on mechanistic interpretation and morphology-direct outcomes, but the absence of systematic synthesis inevitably limits precision. While this approach is appropriate for an integrative framework, it also leaves open the possibility of selection bias and underlines the need for preregistered systematic reviews in the future.

Measurement heterogeneity represents a second major limitation. Ultrasound was the most frequently applied technique, yet often restricted to single anatomical sites with modest reliability reporting, which constrains generalizability. MRI-based trials, although methodologically stronger, remain relatively scarce and unevenly distributed across supplement classes. Inter-operator variability, landmarking differences, and inconsistent reporting of error margins collectively reduce the comparability of trials that otherwise appear similar on the surface. Without harmonized imaging protocols, conclusions about morphological change remain qualified.

Program heterogeneity further complicates interpretation. Training interventions varied widely in volume, progression, supervision, and duration, making it difficult to isolate supplementation effects. Short blocks are particularly problematic, as they may capture early compositional shifts without allowing morphological divergence to manifest. This limits interpretability across creatine and HMB trials, where program quality directly mediates the plausibility of morphological outcomes.

Moderator variables add yet another layer of complexity. Apparent inconsistencies across the literature often reflect differences in sex distribution, training background, or energy balance rather than genuine contradictions in supplement efficacy. Protein and EAA effects clustered in untrained or undernourished cohorts, whereas trained adults with optimized intake frequently exhibited null outcomes. Creatine-related gains appeared most consistent in young male participants under progressive overload, but were less pronounced in mixed-sex or older cohorts. HMB showed context-dependent utility under caloric deficit or deliberate overreaching, but largely neutral effects in eucaloric, resistance-trained settings. Adjuncts such as omega-3 fatty acids occasionally produced small morphological signals in older or nutritionally compromised populations yet were negligible in healthy young adults. Future trials should therefore predefine and report subgroup analyses by these moderators to clarify under which conditions supplementation meaningfully alters hypertrophy trajectories.

These limitations point to clear research gaps. Priority should be given to factorial or “stack” trials with morphology endpoints, standardized imaging protocols and reliability reporting, and larger, adequately powered cohorts. Longitudinal designs linking performance-mediated mechanisms (e.g., creatine-driven workload) to direct morphological outcomes are also needed. Addressing these gaps will require stronger methodological rigor, integration of baseline dietary assessment, and preregistration of analytic plans to reduce selective reporting and strengthen the evidence base.

4.5. Standardizing Morphological Assessments (Recommendations)

The future strength of evidence on supplementation and hypertrophy will depend less on the number of trials conducted than on the rigor with which outcomes are assessed and reported. Standardization of morphological assessments is therefore essential. To operationalize this recommendation, a minimum reporting framework is proposed in

Table 6.

Adherence to such standards would minimize operator-dependent variability, sharpen the distinction between true hypertrophy and methodological noise, and facilitate cross-study synthesis. Exact imaging sites should be specified, alongside reliability metrics and inter-operator error, to permit replication and comparability across studies. Pre-registration of measurement plans would further reduce selective reporting and improve transparency. In parallel, reporting of resistance-training programs must include set-level details—load, volume, proximity to failure, and progression—so that morphological outcomes can be correctly attributed to the interaction between training and supplementation. Finally, both morphology-direct and performance endpoints should be presented together, allowing mediation analyses that clarify whether supplements act primarily through enhanced workload, anti-catabolic effects, or direct anabolic signaling.

To enable such mediation, a parallel framework is needed for documenting performance variables with the same rigor applied to imaging.

Table 7 outlines minimum reporting elements that allow performance outcomes to be paired with morphological endpoints in a reproducible manner.

Together, these dual frameworks—

Table 6 for imaging and

Table 7 for performance variables—provide the methodological scaffolding needed to resolve the current ambiguity in supplementation trials. By aligning the precision of morphological assessments with equally rigorous documentation of training and performance, future studies will be able to disentangle whether supplements exert their influence through improved workload, reduced catabolism, or direct anabolic signaling. Taken together, such standardization will not only strengthen internal validity but also enable meaningful synthesis across trials, thereby elevating the overall quality of evidence on supplementation and hypertrophy.