Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

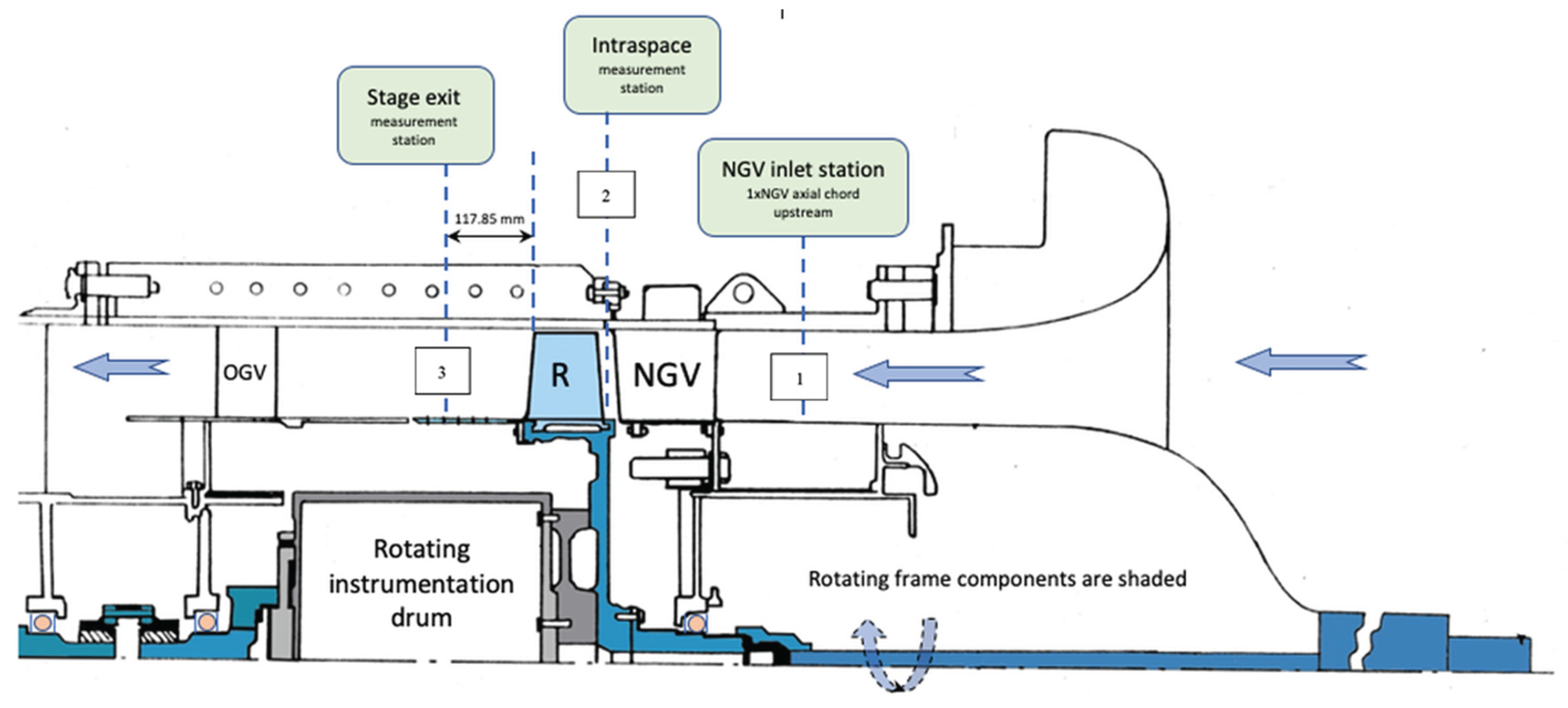

2.1. Baseline Turbine Experiments:

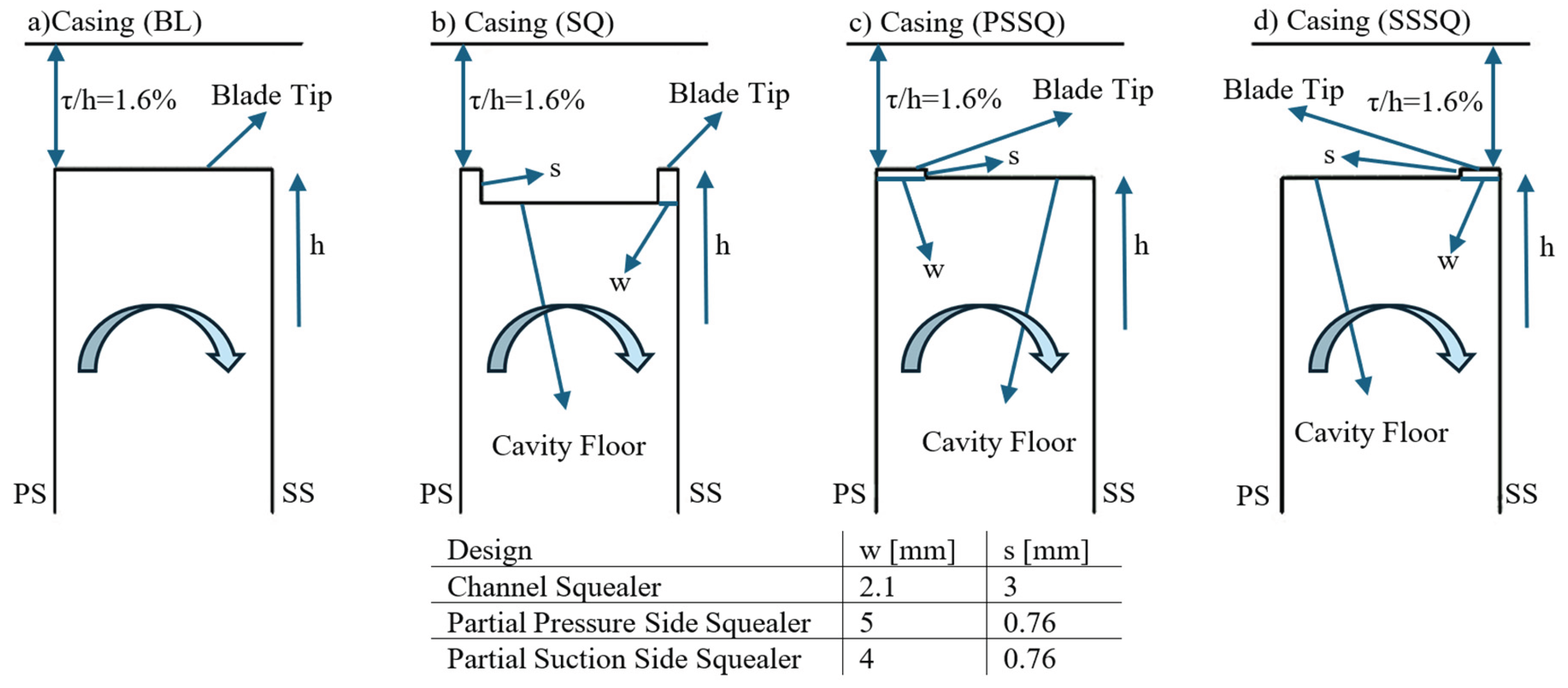

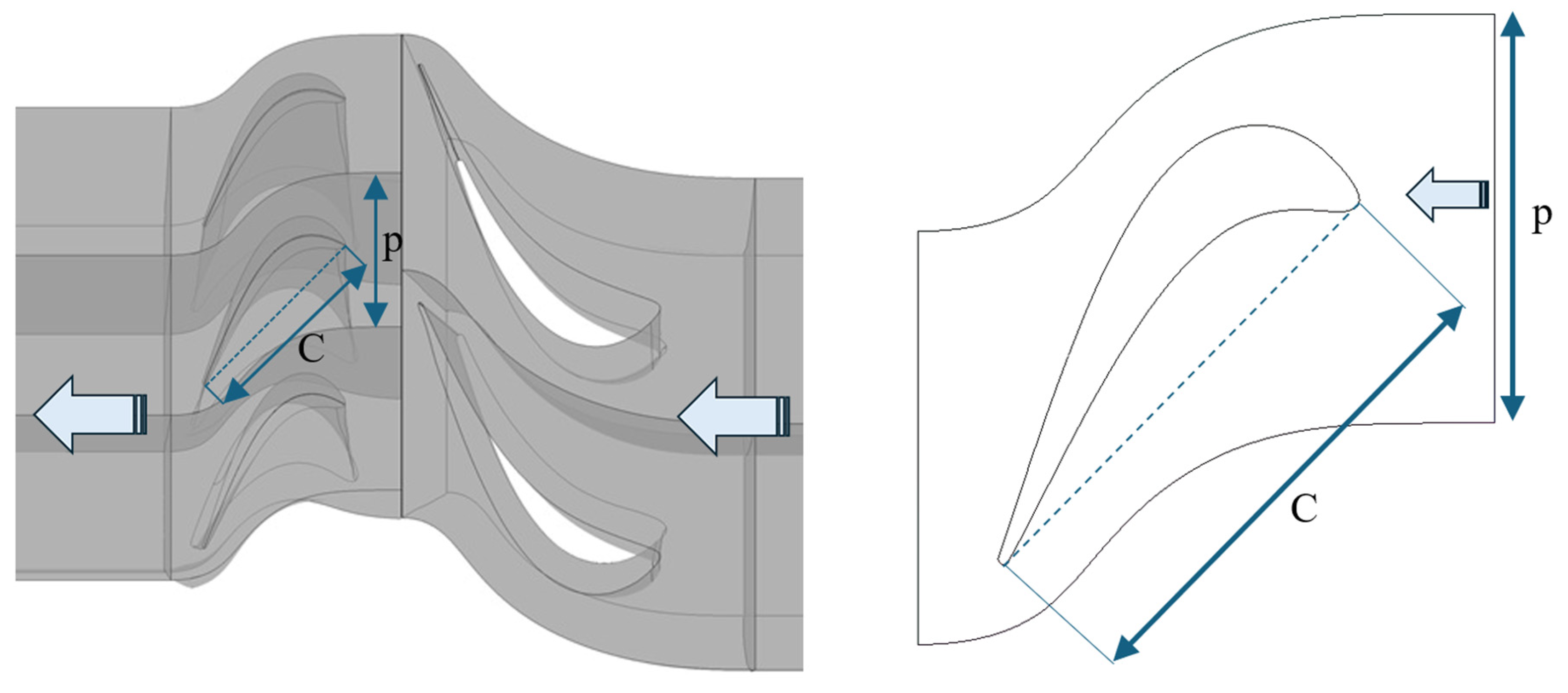

2.2. Turbine Stage Geometry for the Computations

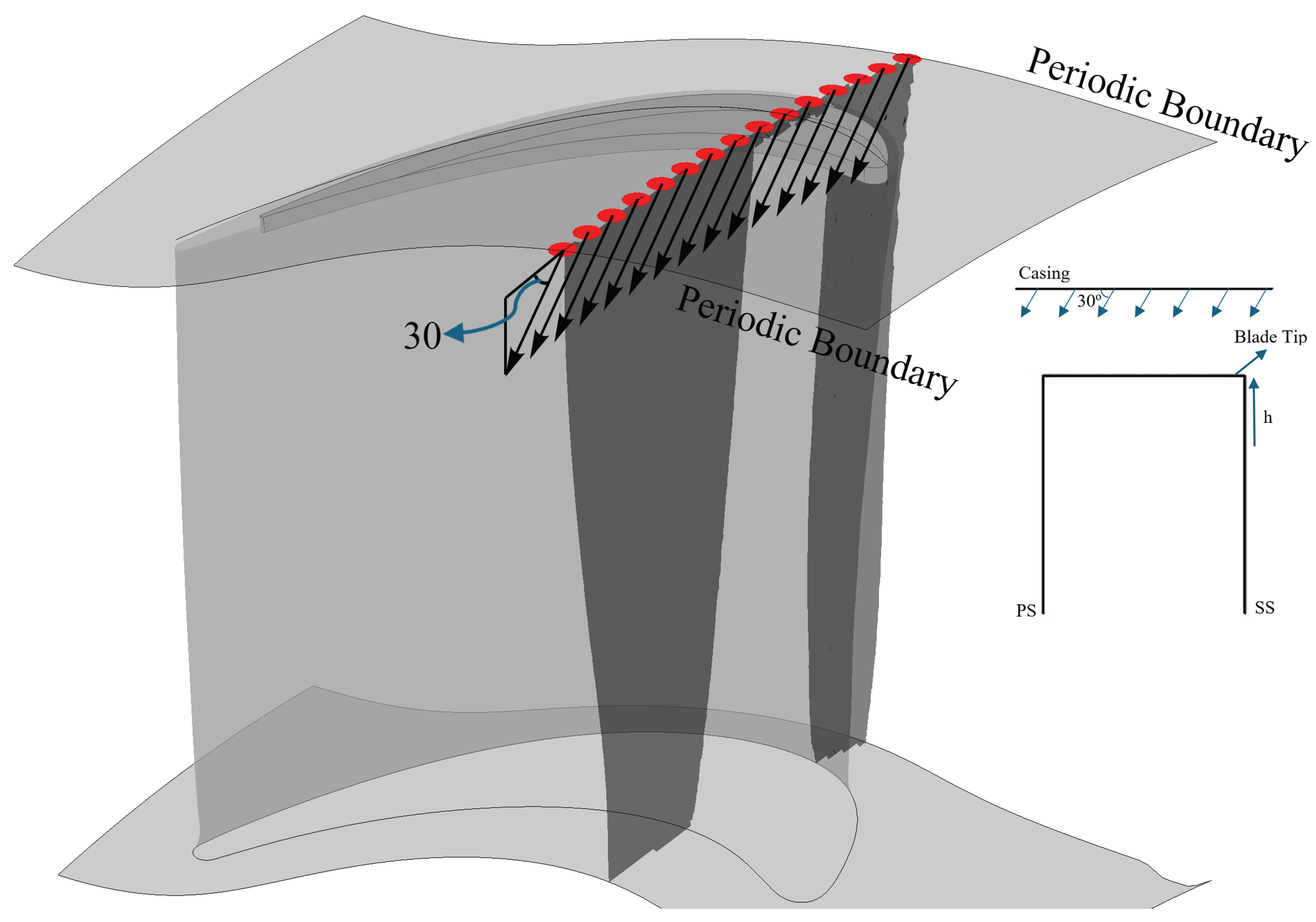

2.3. Discrete Hole Cooling Jets on the Casing

2.4. Unsteady Computations of Flow and Heat Transfer in the Stage

2.5. Turbulence Closure, Convergence and Mass Imbalance

2.6. Unsteady Simulations

2.7. Rotor Time-Stepping During URANS Calculations

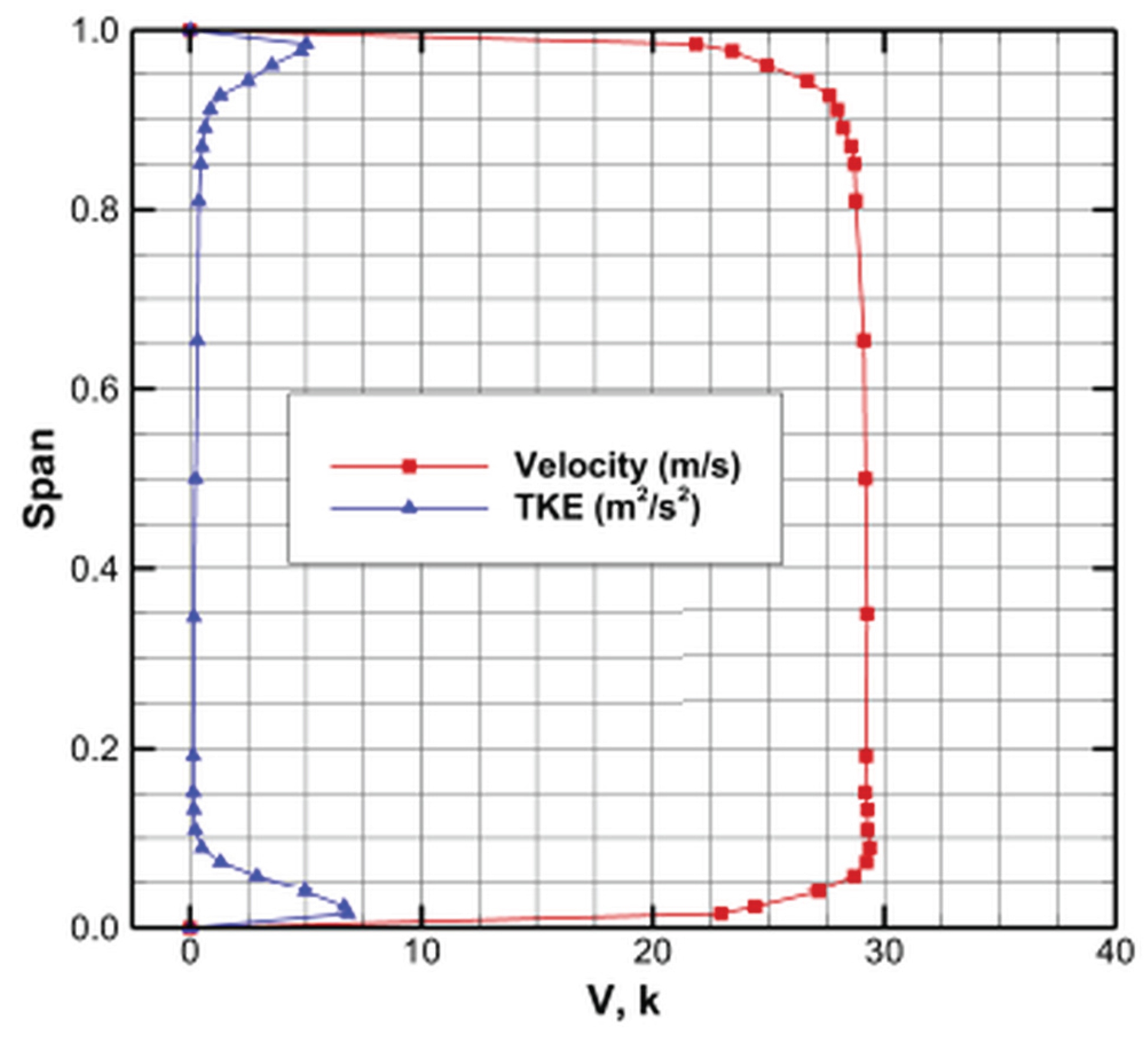

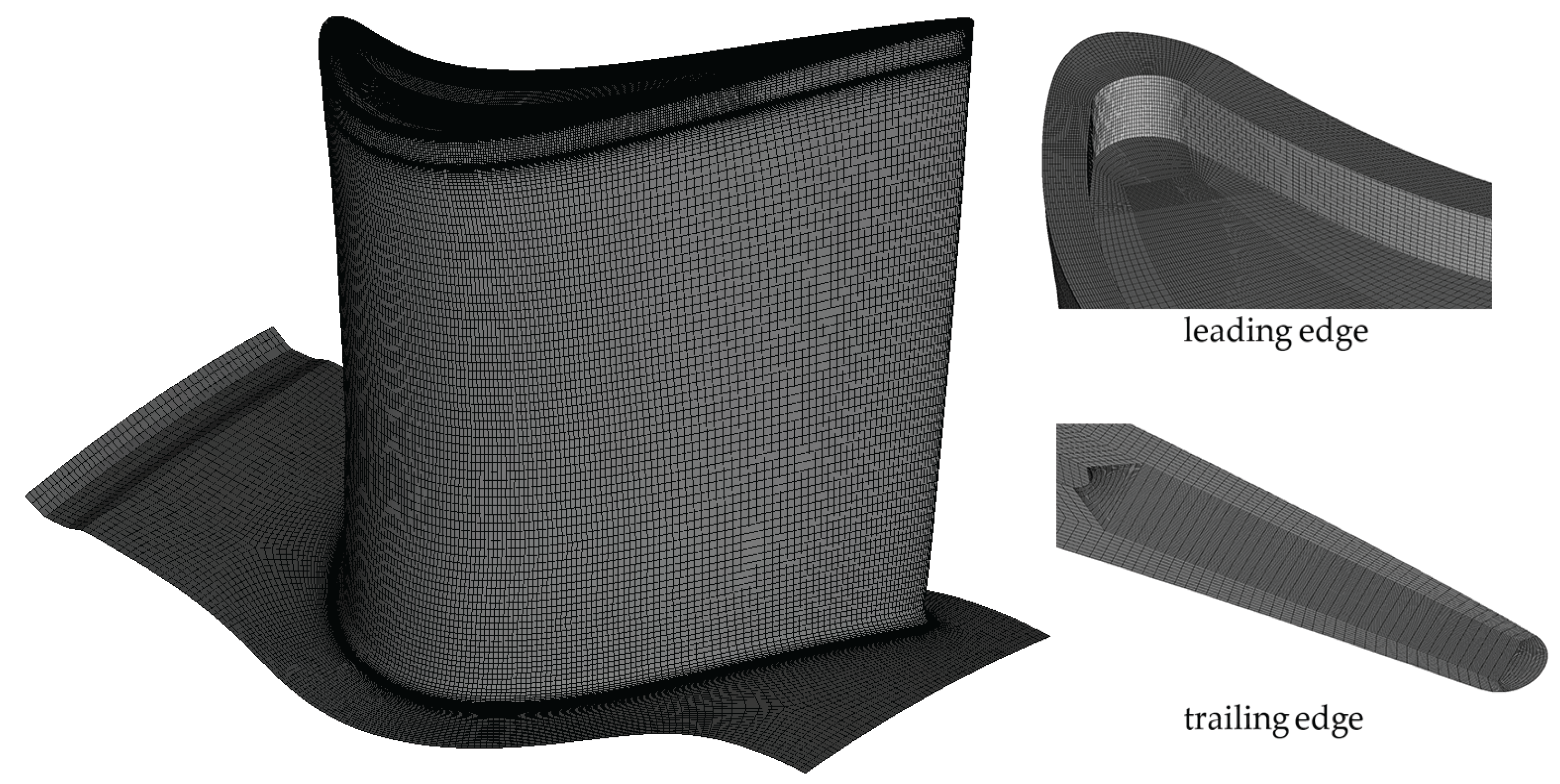

2.8. Mesh Dependency and Validation of the Computations for the Baseline Case

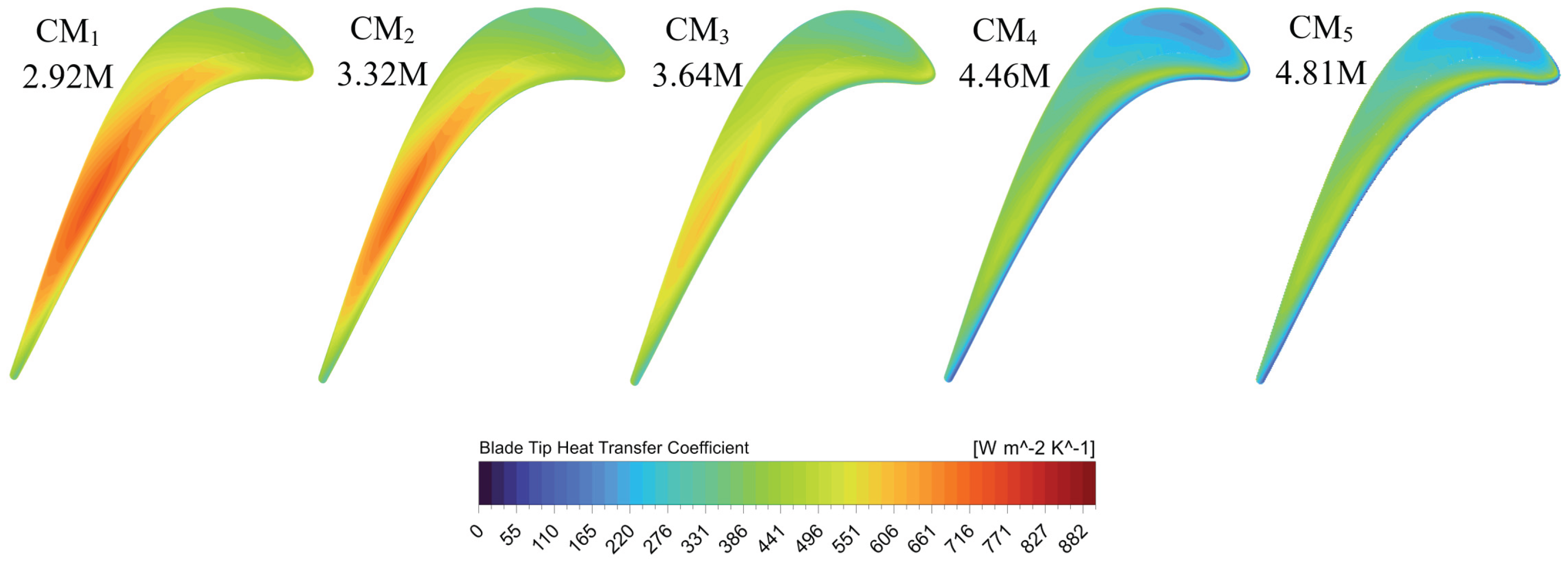

2.8.1. Mesh Dependency of Computed Stage Total Pressure Loss and Heat Transfer

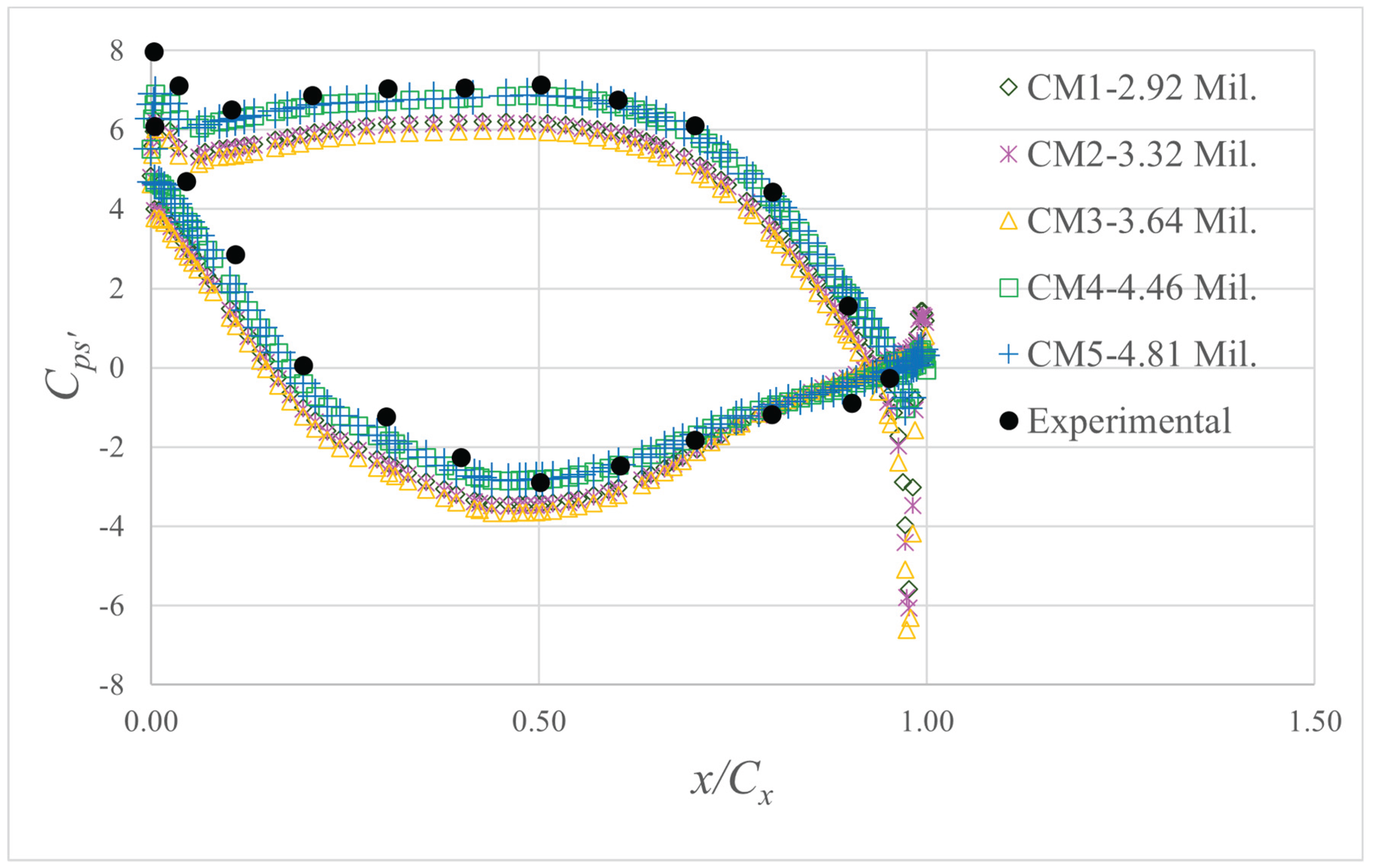

2.8.2. Mesh Dependency and Validation of Blade Loading on the Rotor Mid-span

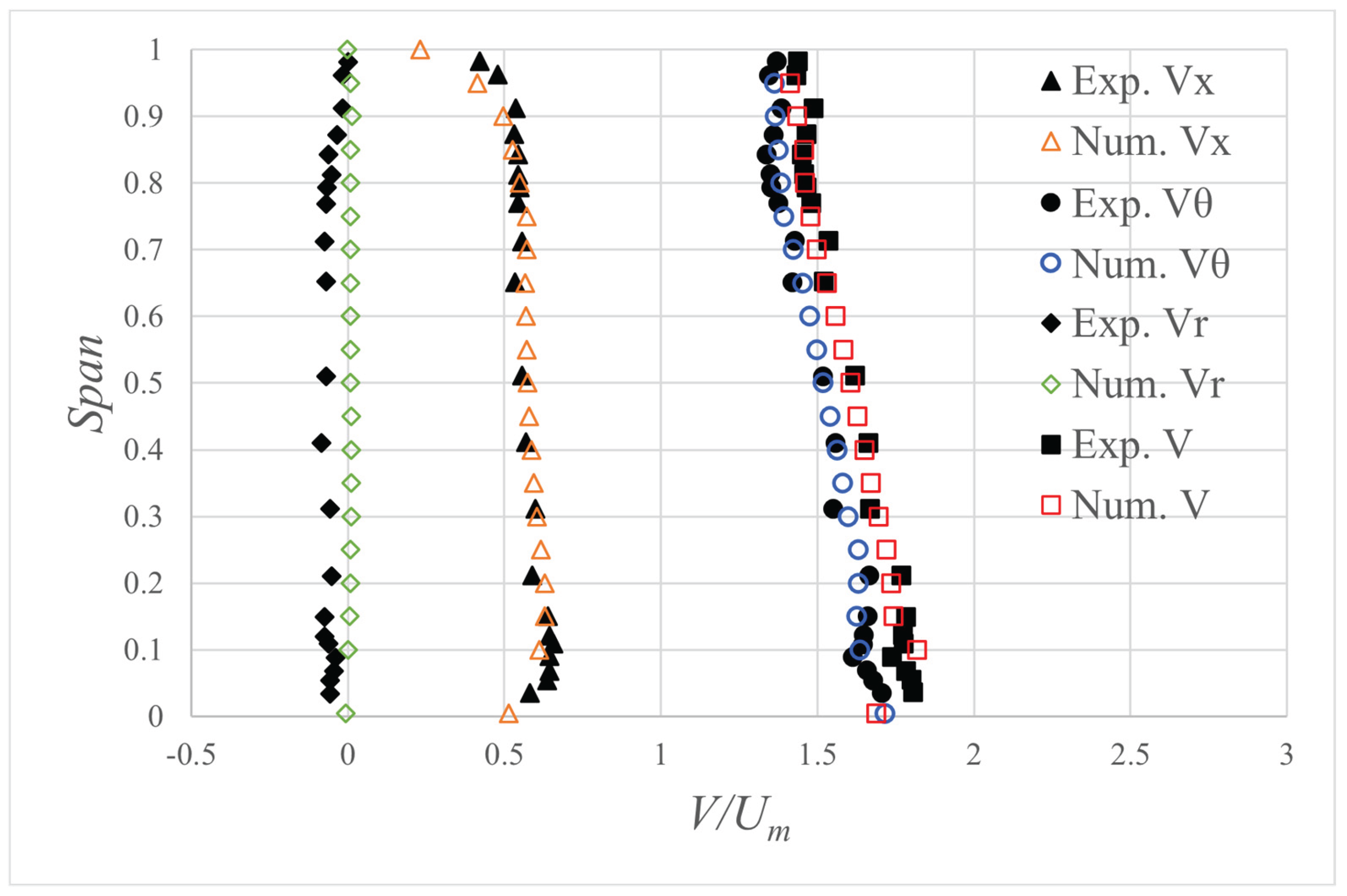

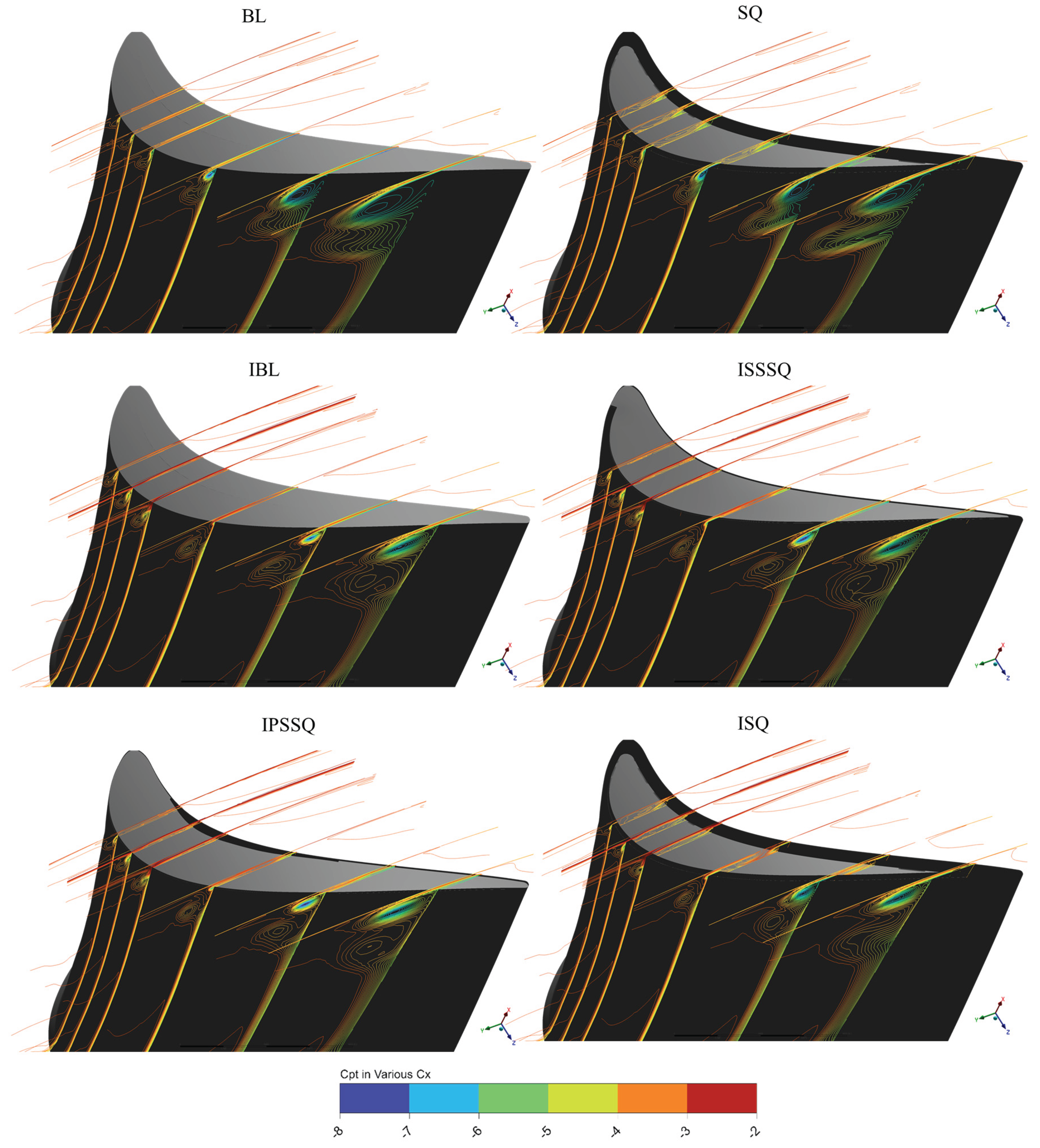

2.8.3. Validation of the Three-Dimensional Flow at NGV Exit

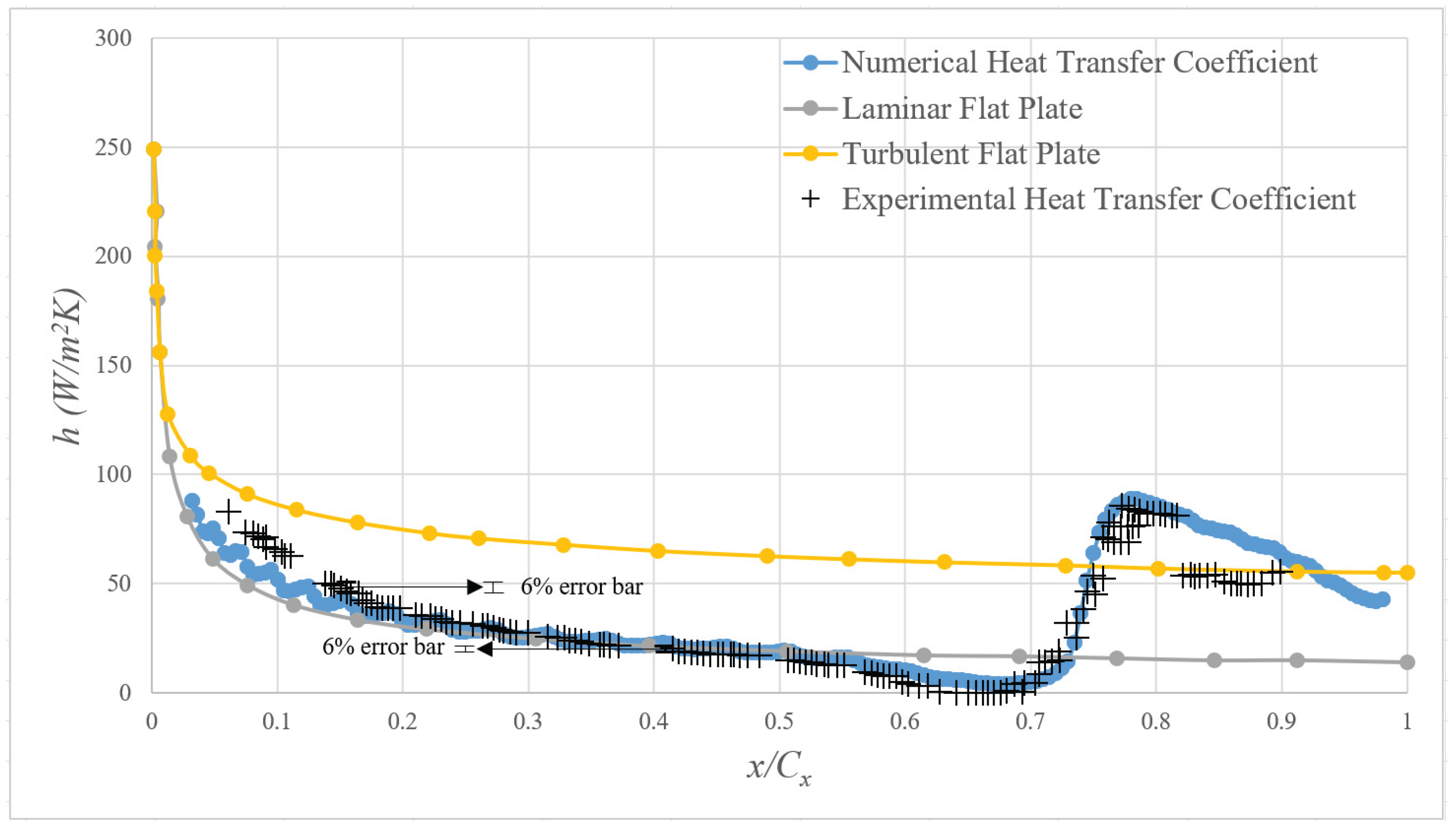

2.8.4. Validation of Convective Heat Transfer Computation

2.8.5. Comparison of Heat Transfer Computations and Measured Data

3. Results and Discussion

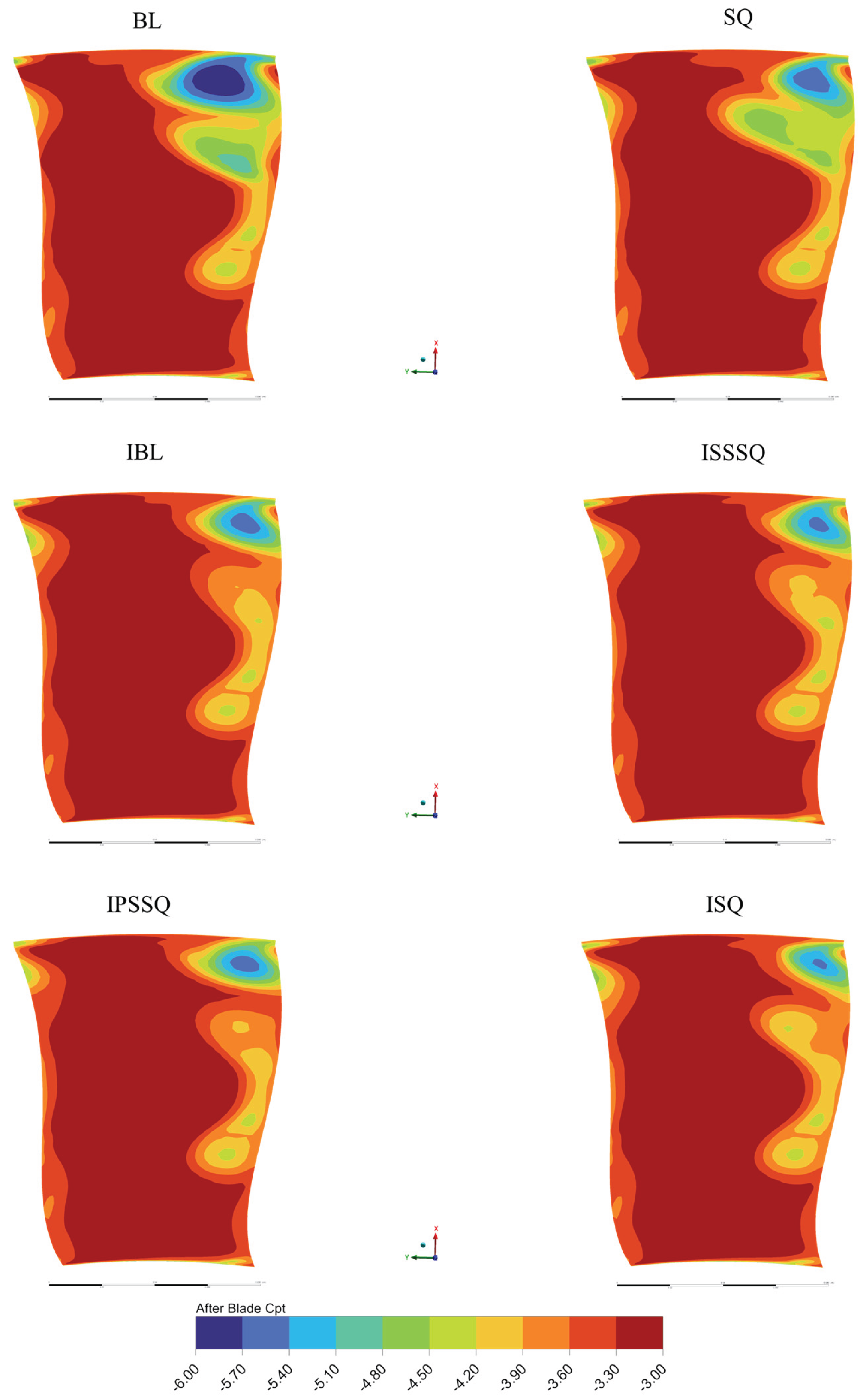

3.1. Influence of Casing Injection on Stage Total Pressure Loss

3.2. Wall Shear Stress on the Investigated Designs

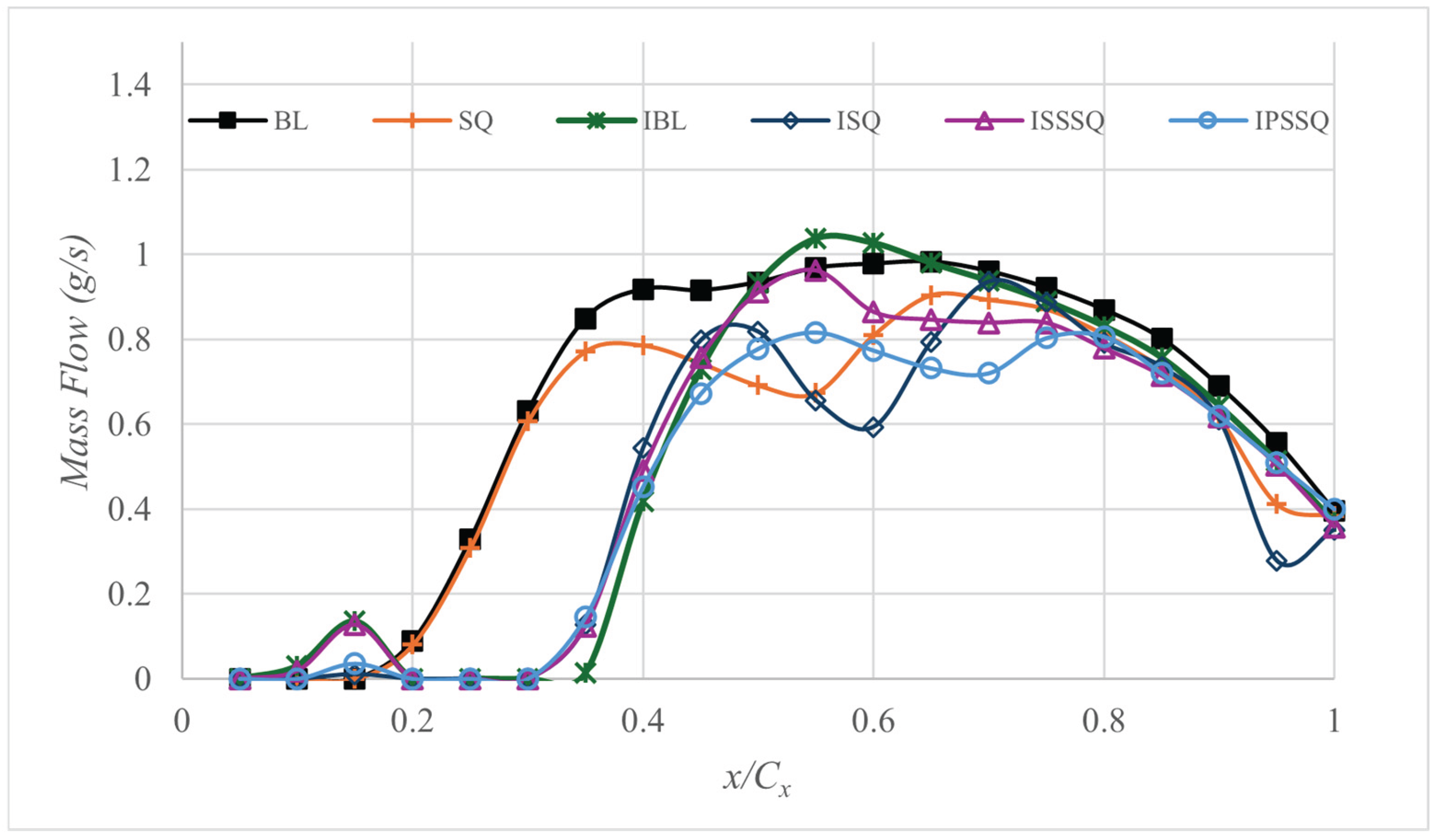

3.3. Local Leakage Mass Flow Rate Distribution Exiting the Blade Tip

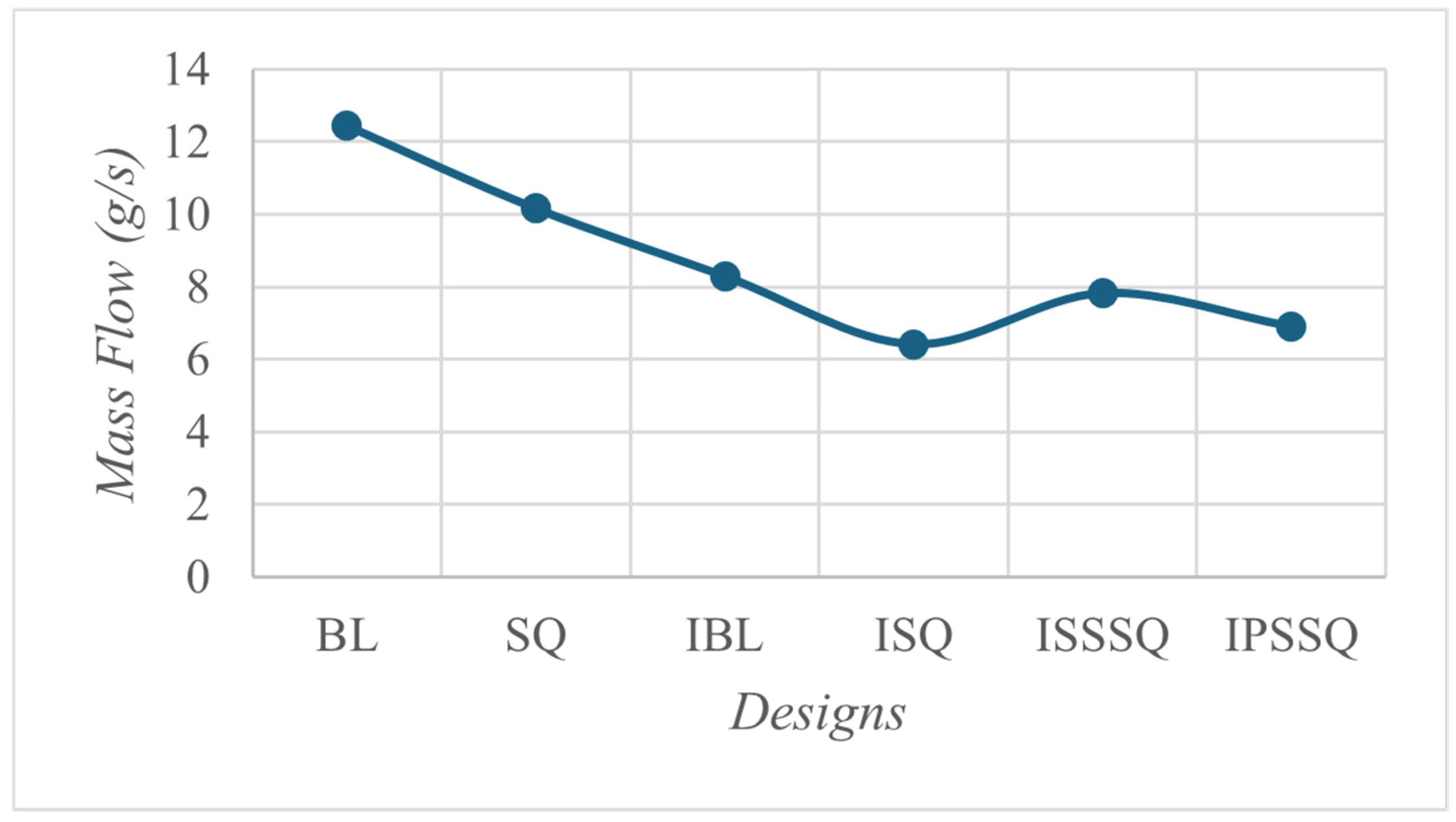

3.4. Total Tip Leakage Mass Flow Rate of the Investigated Designs

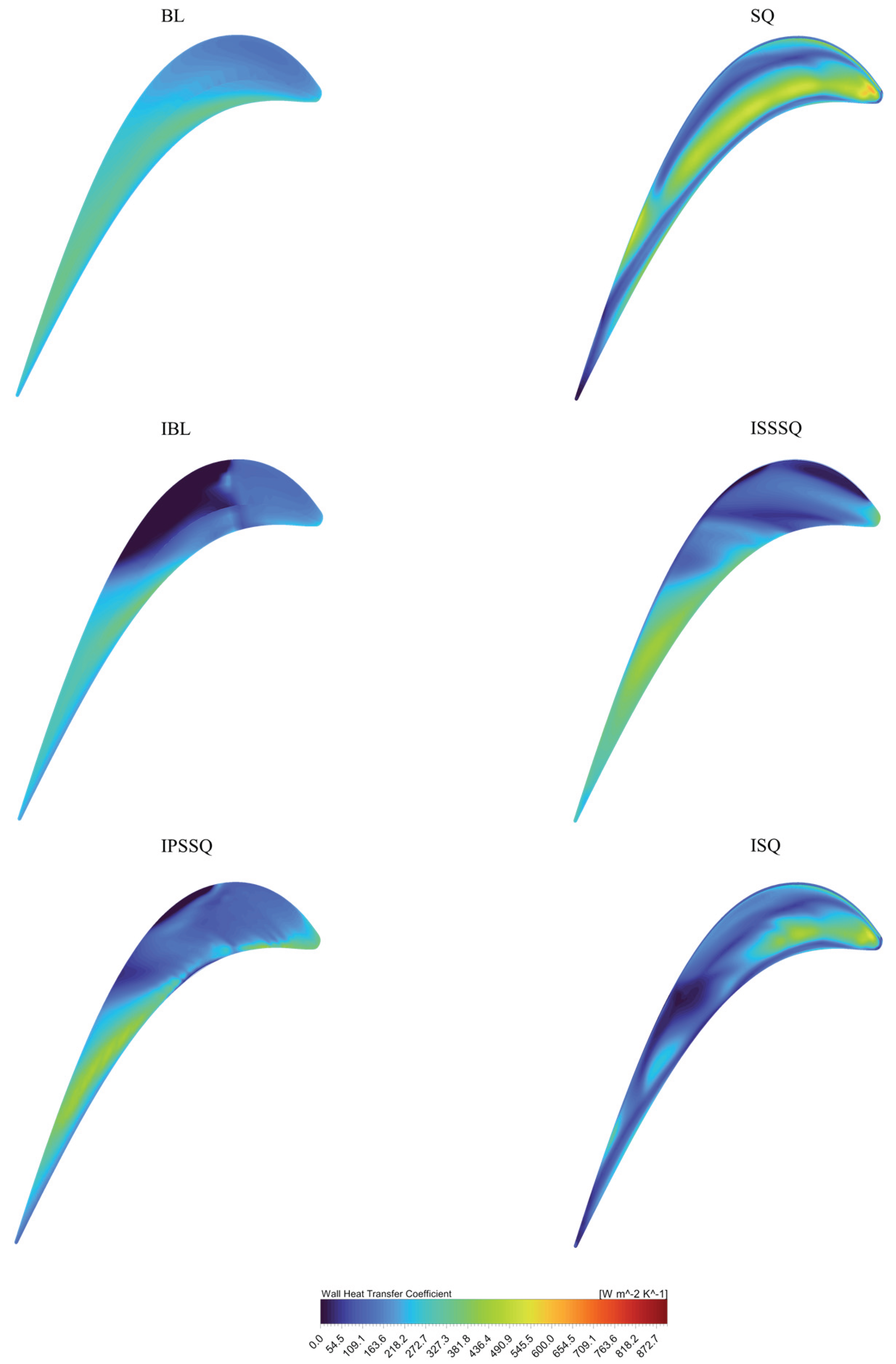

3.5. Convective Heat Transfer on the Tip Surfaces of the Designs

3.6. Comparison of Tip Averaged Heat Transfer Coefficients

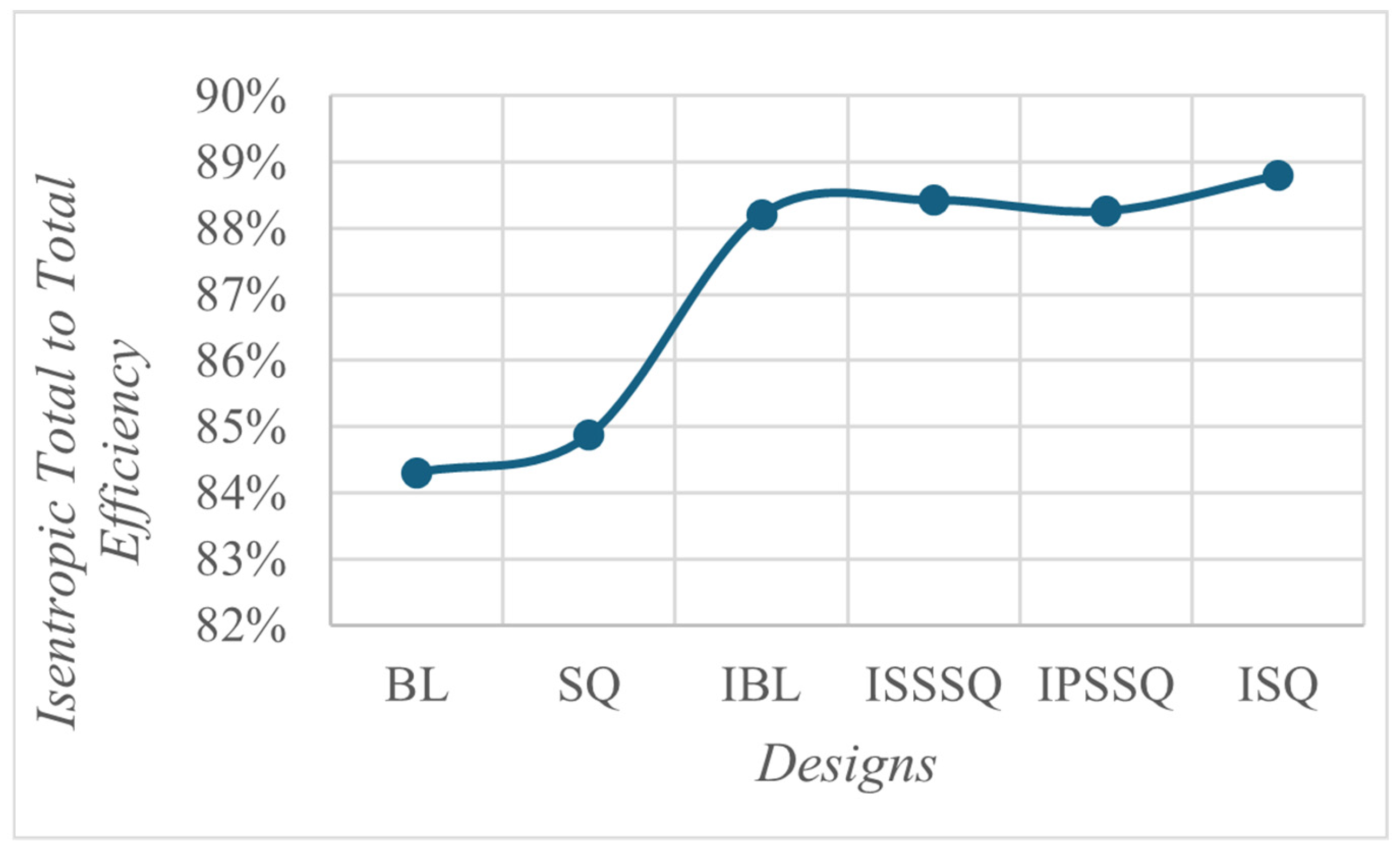

3.7. Total-to-Total Stage Efficiency of the Designs

4. Conclusions

- Channel squealer plus casing injection (ISQ) delivered the best overall performance, cutting by 2.87%, raising ηtt by 4.5%, and slashing area-averaged tip by 43.9% relative to the flat-tip baseline.

- Injection alone (IBL) already reduced by 2.66%, identifying the most favorable jet parameters for the recessed-tip phase.

- Moving the casing-injection holes progressively upstream exerts the greatest leverage on loss reduction. Placing them at x/Cx = 0.30, rather than 0.50 or 0.70, further weakens the tip-leakage vortex during its formative roll-up and shortens its development path, yielding up to a three-fold drop in total-pressure loss relative to the flat tip. Once the injection is early, performance scales almost linearly with jet momentum and its spatial distribution, larger diameters and a higher blowing ratio supply more kinetic energy to the jet core, while increasing the hole count from 7 to 11 and finally to 15 spreads that momentum over a wider swath of the tip gap, enhancing entrainment and further weakening the TLV. A steeper inclination (50° vs 30°) provides an additional but secondary boost by directing the jet more directly against the cross-gap leakage flow. However, its marginal benefit diminishes when the dominant vortex has already been truncated by upstream, high-momentum, finely distributed injection. Overall, the data indicate a “sooner–stronger–finer” strategy, early introduction, ample momentum, and dense spatial coverage, delivers the most effective aerodynamic mitigation of tip-induced losses while avoiding the diminishing returns observed when any one parameter is optimized in isolation.

- A plain channel squealer without injection gave moderate benefits, ( ↓ 1.03%, h ↓ 9.3%, ηtt ↑ ≈ 0.6 p.p.) showing cavity confinement helps but cannot suppress the leakage vortex entirely.

- Partial squealer rims with injection (ISSSQ & IPSSQ) offered intermediate gains ( ↓ ≈ 2.7–2.8 %, h ↓ 17.9–29.4 %, ηtt ↑ ≈ 4.1–3.9 p.p.) but remained inferior to the full squealer due to asymmetric leakage control.

- Flow-field computations confirmed that the ISQ configuration almost eliminates the tip-leakage vortex core and associated high-loss region, whereas injection or squealer alone only weakens it; the baseline retains the strongest vortex and largest loss zone.

- Recessed tip designed lengthen the leakage flow path and reduce the discharge coefficient, establishing a cavity recirculation that raises static pressure at the rim and weakens the effective cross-gap pressure gradient, thereby diminishing TLV roll-up and near-wall shear production. By shifting the leakage emergence downstream and away from the suction-edge peak-loading region, the squealer lowers vortex-core strength and reduces its residence time near the endwall, cutting entropy generation and wall-parallel velocity gradients. Discrete casing injection introduced upstream and at a shallow inclination lays down a wall-attached momentum sheet that energizes the endwall boundary layer, fills the low-momentum corner, and resists the cross-passage sweep that feeds secondary separation.

- The injected jets also impose counter-circulation and add static pressure locally, partially resisting the inflow into the gap so that vortex–vortex interaction cancels part of the TLV circulation. With an adequate blowing ratio and sufficient hole density, the jets remain attached (avoiding lift-off), limiting extra mixing while providing film cooling that lowers driving temperature differences and further reduces convective coefficients. In combination, the recessed cavity suppresses the leakage source while the injection pre-conditions the endwall flow and preempts TLV formation, yielding a synergistic reduction in aerodynamic loss and heat transfer beyond either strategy alone.

- Partial rims deliver only intermediate gains because residual asymmetric leakage paths remain, sustaining weaker but still organized TLV structures compared with the uniform confinement achieved by a full channel.

- Pairing optimized casing injection with a full channel squealer achieves a synergistic suppression of tip-leakage aerodynamic losses and heat transfer, outperforming either strategy in isolation. The approach offers a 2.9% reduction in stage losses, 43.9% drop in area-averaged tip heat transfer coefficient together with a 5.3% efficiency gain, figures that translate directly into reduced fuel burn or increased turbine life. slashing tip h by 43.9%. Future work should address a more comprehensive optimization of the parameters encompassing all the blade chord as well as higher blowing ratio to assess overblowing effects and lower injection angles.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | |

| AFTRF | Pennsylvania State University Axial Flow Turbine Research Facility |

| BL | Baseline |

| CM | Computational mesh |

| Exp. | Experimental |

| HP | High pressure |

| IBL | Injection plus baseline |

| IPSSQ | Injection plus pressure side partial squealer |

| ISQ | Injection plus channel squealer |

| ISSSQ | Injection plus suction side partial squealer |

| NGV | Nozzle guide vane |

| Num. | Numerical |

| p.p. | Percentage point |

| PS | Pressure side |

| PSSQ | Pressure side partial squealer |

| Rad. | Radial |

| SQ | Channel squealer |

| SS | Suction side |

| SSSQ | Suction side partial squealer |

| SST | Shear stress transport |

| TLV | Tip leakage vortex |

| URANS | Unsteady Reynolds-averaged Navier–Stokes |

| Vel. | Velocity |

Appendix A

| Upper Surface | Lower Surface | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| x [mm] | y [mm] | x [mm] | y [mm] |

| -1.512 | 1.906 | 29.33 | -23.823 |

| -4.31 | 4.462 | 30.965 | -28.265 |

| -7.173 | 6.741 | 32.506 | -32.569 |

| -10.096 | 8.716 | 33.952 | -36.731 |

| -13.076 | 10.349 | 35.318 | -40.749 |

| -16.089 | 11.609 | 36.606 | -44.62 |

| -19.099 | 12.49 | 37.823 | -48.344 |

| -22.058 | 13.015 | 38.971 | -51.919 |

| -24.794 | 13.232 | 40.005 | -55.187 |

| -27.277 | 13.263 | 40.931 | -58.146 |

| -29.497 | 13.188 | 41.752 | -60.797 |

| -31.452 | 13.056 | 42.47 | -63.137 |

| -33.145 | 12.919 | 43.089 | -65.167 |

| -34.58 | 12.833 | 43.61 | -66.885 |

| -35.808 | 12.826 | 44.053 | -68.353 |

| -36.838 | 12.905 | 44.43 | -69.587 |

| -37.673 | 13.059 | 44.744 | -70.605 |

| -38.322 | 13.261 | 44.968 | -71.42 |

| -38.792 | 13.489 | 45.062 | -72.063 |

| -39.115 | 13.711 | 44.966 | -72.539 |

| -39.358 | 13.93 | 44.739 | -72.878 |

| -39.526 | 14.13 | 44.492 | -73.091 |

| -39.637 | 14.292 | 44.274 | -73.203 |

| -39.752 | 14.508 | 44.086 | -73.258 |

| -39.869 | 14.813 | 43.827 | -73.292 |

| -39.953 | 15.212 | 43.503 | -73.251 |

| -39.982 | 15.701 | 43.16 | -73.102 |

| -39.921 | 16.351 | 42.808 | -72.725 |

| -39.721 | 17.175 | 42.452 | -72.129 |

| -39.355 | 18.171 | 42.085 | -71.364 |

| -38.784 | 19.327 | 41.697 | -70.593 |

| -38.004 | 20.649 | 41.105 | -69.326 |

| -36.987 | 22.128 | 40.48 | -68.032 |

| -35.701 | 23.816 | 39.741 | -66.503 |

| -34.102 | 25.67 | 38.886 | -64.739 |

| -32.14 | 27.632 | 37.915 | -62.741 |

| -29.729 | 29.584 | 36.828 | -60.509 |

| -26.81 | 31.38 | 35.617 | -58.044 |

| -23.339 | 32.808 | 34.294 | -55.348 |

| -19.512 | 33.645 | 32.901 | -52.538 |

| -15.434 | 33.811 | 31.44 | -49.616 |

| -11.229 | 33.241 | 29.908 | -46.584 |

| -7.031 | 31.901 | 28.301 | -43.443 |

| -2.982 | 29.781 | 26.616 | -40.196 |

| 0.816 | 26.956 | 24.845 | -36.845 |

| 4.341 | 23.558 | 22.986 | -33.394 |

| 7.508 | 19.823 | 21.092 | -29.692 |

| 10.379 | 15.856 | 19.159 | -26.552 |

| 13.025 | 11.736 | 17.176 | -23.17 |

| 15.479 | 7.499 | 15.139 | -19.889 |

| 17.772 | 3.172 | 13.038 | -16.508 |

| 19.925 | -1.226 | 10.878 | -13.241 |

| 21.923 | -5.674 | 8.623 | -10.034 |

| 23.922 | -10.166 | 6.276 | -6.894 |

| 25.791 | -14.692 | 3.813 | -3.844 |

| 27.59 | -19.246 | 1.224 | -0.9 |

Appendix B

| Upper Surface | Lower Surface | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| x/c | y/c | x/c | y/c |

| 0.00168 | 0.00771 | 0.00016 | -0.0021 |

| 0.00736 | 0.0191 | 0.00435 | -0.0098 |

| 0.01701 | 0.03121 | 0.01501 | -0.0163 |

| 0.03055 | 0.04344 | 0.03127 | -0.0224 |

| 0.04794 | 0.05534 | 0.05277 | -0.028 |

| 0.06915 | 0.06648 | 0.07923 | -0.0329 |

| 0.09417 | 0.07658 | 0.11036 | -0.0373 |

| 0.12295 | 0.08544 | 0.14575 | -0.041 |

| 0.15541 | 0.09296 | 0.18488 | -0.0442 |

| 0.19133 | 0.09914 | 0.22722 | -0.0467 |

| 0.23041 | 0.10397 | 0.27222 | -0.0485 |

| 0.27229 | 0.10746 | 0.31929 | -0.0494 |

| 0.31654 | 0.10964 | 0.36784 | -0.0494 |

| 0.36268 | 0.11055 | 0.41726 | -0.048 |

| 0.41019 | 0.11018 | 0.46727 | -0.0449 |

| 0.45853 | 0.10853 | 0.51811 | -0.0398 |

| 0.50714 | 0.10557 | 0.56979 | -0.0334 |

| 0.55548 | 0.1012 | 0.62191 | -0.0262 |

| 0.60323 | 0.09517 | 0.67386 | -0.0189 |

| 0.65041 | 0.0876 | 0.72497 | -0.0118 |

| 0.69676 | 0.07903 | 0.77446 | -0.0055 |

| 0.74171 | 0.0699 | 0.82144 | -0.0004 |

| 0.78466 | 0.06055 | 0.86497 | 0.00324 |

| 0.82498 | 0.05125 | 0.90406 | 0.00526 |

| 0.86207 | 0.04221 | 0.93768 | 0.00567 |

| 0.89529 | 0.03348 | 0.96489 | 0.00463 |

| 0.92431 | 0.02493 | 0.98462 | 0.00262 |

| 0.94922 | 0.01669 | 0.99624 | 0.00073 |

| 0.96999 | 0.00946 | 1 | 0 |

| 0.98605 | 0.00405 | ||

| 0.9964 | 0.00095 | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||

References

- Moore, J.; Tilton, J.S. Tip Leakage Flow in a Linear Turbine Cascade. J. Turbomach. 1988, 110, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameri, A.A.; Steinthorsson, E.; Rigby, D.L. Effects of Tip Clearance and Casing Recess on Heat Transfer and Stage Efficency in Axial Turbines. J. Turbomach. 1999, 121, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, L.S. Secondary Flows in Axial Turbines—A Review. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2001, 934, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camci, C.; Dey, D.; Kavurmacıoğlu, L. Tip Leakage Flows Near Partial Squealer Rims in an Axial Flow Turbine Stage. In Proceedings of the GT2003; Volume 6: Turbo Expo , Parts A and B, June 16, 2003; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Camci, C.; Dey, D.; Kavurmacıoğlu, L. Aerodynamics of Tip Leakage Flows Near Partial Squealer Rims in an Axial Flow Turbine Stage. J. Turbomach. 2005, 127, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavurmacıoğlu, L.; Dey, D.; Camci, C. Aerodynamic Character of Partial Squealer Tip Arrangements in an Axial Flow Turbine. Part II: Detailed Numerical Aerodynamic Field Visualisations via Three Dimensional Viscous Flow Simulations around a Partial Squealer Tip. Prog. Comput. Fluid Dyn. Int. J. 2007, 7, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavurmacıoğlu, L.A.; Maral, H.; Senel, C.B. A Parametric Approach to Turbine Tip Leakage Aerodynamic Investigation for Axial Flow Turbine. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Transport Phenomena and Dynamics of Rotating Machinery; Honolulu, United States; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Senel, C.B.; Maral, H.; Kavurmacıoğlu, L.A.; Camci, C. An Aerothermal Study of the Influence of Squealer Width and Height near a HP Turbine Blade. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 120, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavurmacıoğlu, L.A.; Senel, C.B.; Maral, H.; Camci, C. Casing Grooves to Improve Aerodynamic Performance of a HP Turbine Blade. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2018, 76, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andichamy, V.C.; Khokhar, G.T.; Camci, C. An Experimental Study of Using Vortex Generators As Tip Leakage Flow Interrupters in an Axial Flow Turbine Stage. In Proceedings of the GT2018; Volume 2B: Turbomachinery, June 11 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Da Soghe, R.; Bianchini, C.; Micio, M.; D’Errico, J.; Bavassano, F. Effect of Rim Seal Configuration on Gas Turbine Cavity Sealing in Both Design and Off-Design Conditions. In Proceedings of the GT2018; Volume 5B: Heat Transfer, June 11 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kavurmacıoğlu, L.; Maral, H.; Senel, C.B.; Camci, C. Performance of Partial and Cavity Type Squealer Tip of a HP Turbine Blade in a Linear Cascade. Int. J. Aerosp. Eng. 2018, 2018, 3262164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mischo, B.; Burdet, A.; Behr, T.; Abhari, R.S. Control of Rotor Tip Leakage Through Colling Injection from Casing in a High Work Turbine: Computational Investigation Using A Feature-Based Jet Model.; American Society of Mechanical Engineers, 2007; Vol. 6, p. 1355.

- Behr, T.; Kalfas, A.I.; Abhari, R.S. Desensitization of the Flowfield from Rotor Tip-Gap Height by Casing-Air Injection. J. Propuls. Power 2008, 24, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, T.; Kalfas, A.I.; Abhari, R.S. Control of Rotor Tip Leakage Through Cooling Injection From the Casing in a High-Work Turbine. J. Turbomach. 2008, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, M.; Zang, S. Active Control of Tip Clearance Flow through Casing Air Injection in Axial Turbines. J. Energy Inst. 2011, 84, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Z.; Simon, T.W. Controlling Leakage Flows Over a Rotor Blade Tip Using Air-Curtain Injection: Part I — Aero-Thermal Performance of Rotor Tips. In Proceedings of the GT2019; Volume 5B: Heat Transfer, June 17 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Q.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z.; Feng, Z.; Simon, T.W. Controlling Leakage Flows Over a Rotor Blade Tip Using Air-Curtain Injection: Part II — Rotor Casing Film Cooling. In Proceedings of the GT2019; Volume 5B: Heat Transfer, June 17 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, S.; Gholamalipour, A. Parametric Study of Injection from the Casing in an Axial Turbine. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part J. Power Energy 2020, 234, 582–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Gholamalipour, A. Performance Optimization of an Axial Turbine with a Casing Injection Based on Response Surface Methodology. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2021, 43, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Tan, X.; Liu, S. Effects of Casing Air Injection on Film Cooling and Aerodynamic Performances of an Axial Turbine Cascade. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2022, 29, 101209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, F.; Alpman, E.; Kavurmacıoğlu, L.; Camci, C. An Artificial Neural Network (Ann) Based Aerothermal Optimization of Film Cooling Hole Locations on the Squealer Tip of an Hp Turbine Blade. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccaria, M.A. An Experimental Investigation into the Steady and Unsteady Flow Field in an Axial Flow Turbine. PhD Thesis, The Pennsylvania State University: University Park, PA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lakshminarayana, B.; Camci, C.; Halliwell, I.; Zaccaria, M. Design and Development of a Turbine Research Facility to Study Rotor-Stator Interaction Effects. Int. J. Turbo Jet Engines 1996, 13, 155–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camci, C. 2004; -02.

- Camci, C. A Turbine Research Facility to Study Tip Desensitization Including Cooling Flows, von Karman Institute Lecture Series VKI-LS 2004-02 Turbine Blade Tip Design and Tip Clearance Treatment; Brussels, 2004; ISBN 2-930389-51-6.

- Menter, F.R. Two-Equation Eddy-Viscosity Turbulence Models for Engineering Applications. AIAA J. 1994, 32, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, J.A.; Martinuzzi, R.J.; Savory, E.; Zhang, C.; Roberts, D.A. Assessment of Turbulence Model Predictions for an Aero-Engine Centrifugal Compressor. J. Turbomach. 2010, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turgut, Ö.H.; Camci, C. Factors Influencing Computational Predictability of Aerodynamic Losses in a Turbine Nozzle Guide Vane Flow. J. Fluids Eng. 2016, 138, 051103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaput, T. Control of Near Wall Flow on an Isolated Airfoil at High Angle of Attack Using Piezoelectric Surface Vibration Elements. MSc, Pennsylvania State University: University Park, PA, USA, 1997.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Rotor Hub Tip Ratio | 0.7269 |

| Tip Radius (m) | 0.4582 |

| Blade Height h (m) | 0.1229 |

| Tip Relative Mach Number | 0.24 (max) |

| Nozzle Guide Vane | |

| Number | 23 |

| Midspan axial chord (m) | 0.1123 |

| Turning angle (deg) | 70 |

| Reynolds number based on inlet velocity | 3~4 x |

| Rotor-stator axial spacing at hub (mm) | 36.32 |

| Rotor Blade | |

| Number | 29 |

| Blade pitch, p (mm) | 99.27 |

| Inlet flow angle [o] | 71.3 |

| Stagger angle [o] | 46.2 |

| Midspan axial chord (m) | 0.0929 |

| Turning at tip angle (deg) Turning angle at hub (deg) |

94.42 125.69 |

| Tip clearance t/h | 0.8 % |

| Reynolds number based on inlet velocity | 2.87x |

| Operating Condition | Value |

|---|---|

| Inlet Total Temperature (K) | 289 |

| Inlet Total Pressure (KPa) | 101.36 |

| Mass Flow Rate (kg/s) | 11.05 |

| Rotational Speed (RPM) | 1300 |

| Total Pressure Ratio (/) | 1.0778 |

| Total Temperature Ratio (/) | 0.981 |

| Pressure Drop(mmHg) - | 56.04 |

| Inlet Mass Flow Rate [kg/s] | 11.05 |

| Power (KW) | 60.6 |

| Parameter | Values |

|---|---|

| Number of Injection Points | 7, 11 and 15 |

| Injection Axial Chord Position | 0.3, 0.5 and 0.7 |

| Injection Angle, [o] | 30 and 50 |

| Injection Blow Ratio | 1.22 and 1.85 |

| Injection Hole Diameter [mm] | 0.7 and 1 |

| Mesh | Number of Elements (millions) | Ave. Tip y+ | Error (%) | Blade Tip (W/m2-K) |

Blade Tip Error (%) | |

| CM1 | 2.92 | 24.07 | 3.419 | 0.67% | 548.40 | -25.32 |

| CM2 | 3.32 | 12.52 | 3.442 | 0.61% | 409.54 | -13.43 |

| CM3 | 3.64 | 1.92 | 3.463 | 0.59% | 354.53 | -8.08 |

| CM4 | 4.46 | 0.799 | 3.483 | 0.01% | 325.9 | 0.12 |

| CM5 | 4.81 | 0.774 | 3.484 | - | 326.3 | - |

| Design | ε | Design | ε | Design | ε | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (no inj.) | 3.48374 | - | 0.5-30-1.22-0.7-7 | 3.45758 | 0.75% | 0.7-30-1.22-0.7-11 | 3.46077 | 0.66% |

| 0.3-30-1.22-0.7-7 | 3.45343 | 0.87% | 0.5-30-1.22-0.7-11 | 3.45224 | 0.90% | 0.7-30-1.22-0.7-15 | 3.45842 | 0.73% |

| 0.3-30-1.22-0.7-11 | 3.44597 | 1.08% | 0.5-30-1.22-0.7-15 | 3.44549 | 1.10% | 0.7-30-1.22-1-7 | 3.45909 | 0.71% |

| 0.3-30-1.22-0.7-15 | 3.43739 | 1.33% | 0.5-30-1.22-1-7 | 3.44899 | 1.00% | 0.7-30-1.22-1-11 | 3.45694 | 0.77% |

| 0.3-30-1.22-1-7 | 3.44149 | 1.21% | 0.5-30-1.22-1-11 | 3.43751 | 1.33% | 0.7-30-1.22-1-15 | 3.45315 | 0.88% |

| 0.3-30-1.22-1-11 | 3.43029 | 1.53% | 0.5-30-1.22-1-15 | 3.42391 | 1.72% | 0.7-30-1.85-0.7-7 | 3.45984 | 0.69% |

| 0.3-30-1.22-1-15 | 3.41623 | 1.94% | 0.5-30-1.85-0.7-7 | 3.4508 | 0.95% | 0.7-30-1.85-0.7-11 | 3.45883 | 0.72% |

| 0.3-30-1.85-0.7-7 | 3.44395 | 1.14% | 0.5-30-1.85-0.7-11 | 3.44279 | 1.18% | 0.7-30-1.85-0.7-15 | 3.45432 | 0.84% |

| 0.3-30-1.85-0.7-11 | 3.43385 | 1.43% | 0.5-30-1.85-0.7-15 | 3.42902 | 1.57% | 0.7-30-1.85-1-7 | 3.45551 | 0.81% |

| 0.3-30-1.85-0.7-15 | 3.42131 | 1.79% | 0.5-30-1.85-1-7 | 3.43351 | 1.44% | 0.7-30-1.85-1-11 | 3.4515 | 0.93% |

| 0.3-30-1.85-1-7 | 3.43118 | 1.51% | 0.5-30-1.85-1-11 | 3.41992 | 1.83% | 0.7-30-1.85-1-15 | 3.44649 | 1.07% |

| 0.3-30-1.85-1-11 | 3.41334 | 2.02% | 0.5-30-1.85-1-15 | 3.40361 | 2.30% | 0.7-50-1.22-0.7-7 | 3.46087 | 0.66% |

| 0.3-30-1.85-1-15 | 3.39843 | 2.45% | 0.5-50-1.22-0.7-7 | 3.45197 | 0.91% | 0.7-50-1.22-0.7-11 | 3.46034 | 0.67% |

| 0.3-50-1.22-0.7-7 | 3.4493 | 0.99% | 0.5-50-1.22-0.7-11 | 3.44615 | 1.08% | 0.7-50-1.22-0.7-15 | 3.45662 | 0.78% |

| 0.3-50-1.22-0.7-11 | 3.43996 | 1.26% | 0.5-50-1.22-0.7-15 | 3.43606 | 1.37% | 0.7-50-1.22-1-7 | 3.45722 | 0.76% |

| 0.3-50-1.22-0.7-15 | 3.43059 | 1.53% | 0.5-50-1.22-1-7 | 3.44022 | 1.25% | 0.7-50-1.22-1-11 | 3.4557 | 0.80% |

| 0.3-50-1.22-1-7 | 3.43486 | 1.40% | 0.5-50-1.22-1-11 | 3.4267 | 1.64% | 0.7-50-1.22-1-15 | 3.45076 | 0.95% |

| 0.3-50-1.22-1-11 | 3.41857 | 1.87% | 0.5-50-1.22-1-15 | 3.41137 | 2.08% | 0.7-50-1.85-0.7-7 | 3.45758 | 0.75% |

| 0.3-50-1.22-1-15 | 3.40518 | 2.26% | 0.5-50-1.85-0.7-7 | 3.44212 | 1.19% | 0.7-50-1.85-0.7-11 | 3.45684 | 0.77% |

| 0.3-50-1.85-0.7-7 | 3.43597 | 1.37% | 0.5-50-1.85-0.7-11 | 3.42933 | 1.56% | 0.7-50-1.85-0.7-15 | 3.45232 | 0.90% |

| 0.3-50-1.85-0.7-11 | 3.42246 | 1.76% | 0.5-50-1.85-0.7-15 | 3.41243 | 2.05% | 0.7-50-1.85-1-7 | 3.451 | 0.94% |

| 0.3-50-1.85-0.7-15 | 3.4093 | 2.14% | 0.5-50-1.85-1-7 | 3.4185 | 1.87% | 0.7-50-1.85-1-11 | 3.44473 | 1.12% |

| 0.3-50-1.85-1-7 | 3.41465 | 1.98% | 0.5-50-1.85-1-11 | 3.40286 | 2.32% | 0.7-50-1.85-1-15 | 3.43543 | 1.39% |

| 0.3-50-1.85-1-11 | 3.39186 | 2.64% | 0.5-50-1.85-1-15 | 3.39164 | 2.64% | |||

| 0.3-50-1.85-1-15 | 3.39101 | 2.66% | 0.7-30-1.22-0.7-7 | 3.4617 | 0.63% |

| Design | ε | ηtt | ϑ | Г | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BL | 3.48374 | 0.00% | 84.304% | 0.00% | 325.95 | 0.00% |

| SQ | 3.44781 | 1.03% | 84.874% | 0.57% | 295.49 | 9.34% |

| IBL | 3.39101 | 2.66% | 88.199% | 3.89% | 221.32 | 32.10% |

| ISSSQ | 3.38985 | 2.70% | 88.419% | 4.11% | 267.62 | 17.89% |

| IPSSQ | 3.38673 | 2.78% | 88.253% | 3.95% | 230.06 | 29.42% |

| ISQ | 3.38360 | 2.87% | 88.791% | 4.49% | 182.82 | 43.91% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).