1. Introduction

Polymer-inorganic composite films can be fabricated via a variety of methods, such as the sol-gel method [

1], melt blending [

2], in-situ polymerization [

3,

4], and solution casting [

5]. Solution casting has been widely used because of its simple operation and low cost [

6,

7]. For example, Chen et al. [

8] prepared PPA@GNPs/PVA composite film by solution casting, using graphene nanoplates (GNPs) as a thermally conductive filler, and the resulting PPA@GNPs/PVA composite film achieved high in-plane thermal conductivity of 82.4 W·m

-1·K

-1. Wang et al. [

9] reported a self-healing, highly stretchable, and conductive polymer composite by solution casting, which is suitable for electronic skin applications. Polymer-inorganic composites obtained by solution casting are usually considered to be homogeneous, this is, the inorganic fillers are equally distributed in all parts of the polymer matrix from inside to outside. Few studies have focused on what happens to the upper and lower surfaces of the polymer-inorganic composites.

We previously prepared a thermally conductive yet electrically insulating Polyvinyl alcohol/reduced graphene oxide (PVA/rGO) composite film by solution casting [

10]. Surprisingly, the composite film was not uniform, and its good electrical insulation performance was due to the pure PVA self-assembled on the upper and lower surfaces of the composite film. It is known that the surfaces of polymer-based composites are coated by pure polymer at low filler content. However, it is challenging to reveal the formation mechanism of polymer self-assembly on the surfaces of polymer-based composites at high filler loading.

In this work, we prepared PVA/rGO and alcohol-soluble nylon/rGO (ES/rGO) composite films with high filler contains by solution casting, and revealed pure polymer (PVA/ES) accumulated on the surface of composite films produce their good electrical insulation performance at high rGO content. Subsequently, molecular dynamics simulation was used to elucidate the formation mechanism of the phenomenon in two steps. First, we computed the interaction energies ΔE of PVA with PVA, H2O, and rGO, and of rGO with itself, in the PVA/rGO composite film system; this allows us to judge the motion trend of each component. Next, we observed the self-assembly behavior of the polymer on the composite surface at the molecular level. In addition, a series of polymer-inorganic composite systems were also prepared by solution casting, varying polymer matrices, solvents, and fillers. After plasma etching, changes in the surface morphology of these samples indicated it may be a universal phenomenon of polymer self-assembled on the surface of composites. This study can provide valuable references for the design and preparation of multifunctional composites.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Waterborne polyurethane (WPU) (pH = 6-9) was purchased from the Anhui Anda Huatai New Materials Co., Ltd., Anhui, China. Multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) (diameters: 10-20 nm, purity > 98%) were provided by Chengdu Organic Chemistry Co. Ltd., Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu, China. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA, Mw ≈ 1750) with an alcoholysis degree of 88% was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd., China. Graphene oxide (GO) dispersion solution (Solid content: 1.0%) was purchased from the Sixth Element (Changzhou) Materials Technology Co., Ltd., China. N, N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), glycerol, ascorbic acid, and glacial acetic acid were provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China. Alcohol-soluble nylon (ES) was purchased from the Shanghai Zhenwei Composites Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China. Al2O3 was provided by Xiya Chemical Technology Co. Ltd., Shandong, China. Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) was provided by BASF Polyurethanes GmbH, Germany.Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication.

2.2. Preparation of Composite Films

We prepared the polymer-inorganic composite films by solution casting according to the previous study [

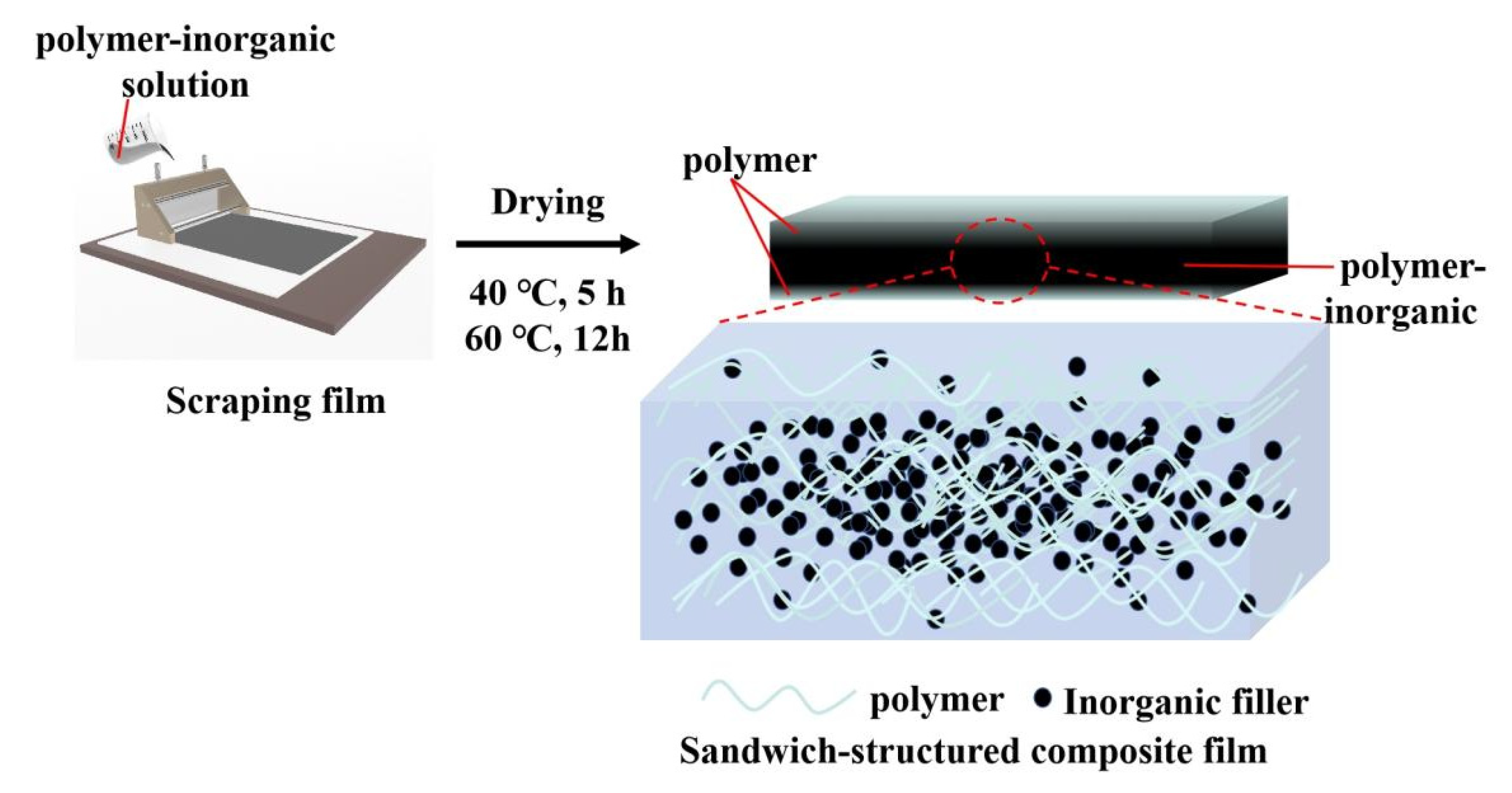

10]; the water-based polymer PVA and the alcohol-soluble nylon (ES) were chosen to prepare polymer/rGO composite films by solution casting, the process is shown in

Figure 1. The inorganic filler and polymer matrix were first dissolved in their corresponding solvents; the two solutions were then mixed. The mixed solution was scraped onto a flat plate and dried at 40 ℃ for 5 h, then at 60 ℃ for 12 h, to yield the polymer-inorganic composite film.

2.3. Preparation of Composite Films

A plasma etching machine was used to etch the surface of composite films. The surface micro-morphologies of the composite films both before and after etching were observed by field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, with an S-4800 (II) microscope from Japan). All SEM images were taken with low acceleration voltage (e.g., 3 kV) and high current (e.g., 10 µA). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, performed with a JEOL-2100F at 100 kV) was employed to observe the morphology and microstructures of films. The volume/surface resistivity of different composite films was obtained using a ZC36 high insulation resistance measuring instrument.

2.4. Molecular Dynamics Simulation (MDS)

We first imported the graphene cell and geometrically optimized it using the COMPASS III force field, then increased the supercell range to 6 for computations including polymers. We constructed a real polymer PVA conformation containing 10 PVA chains and with a density of 1.26 g/cm

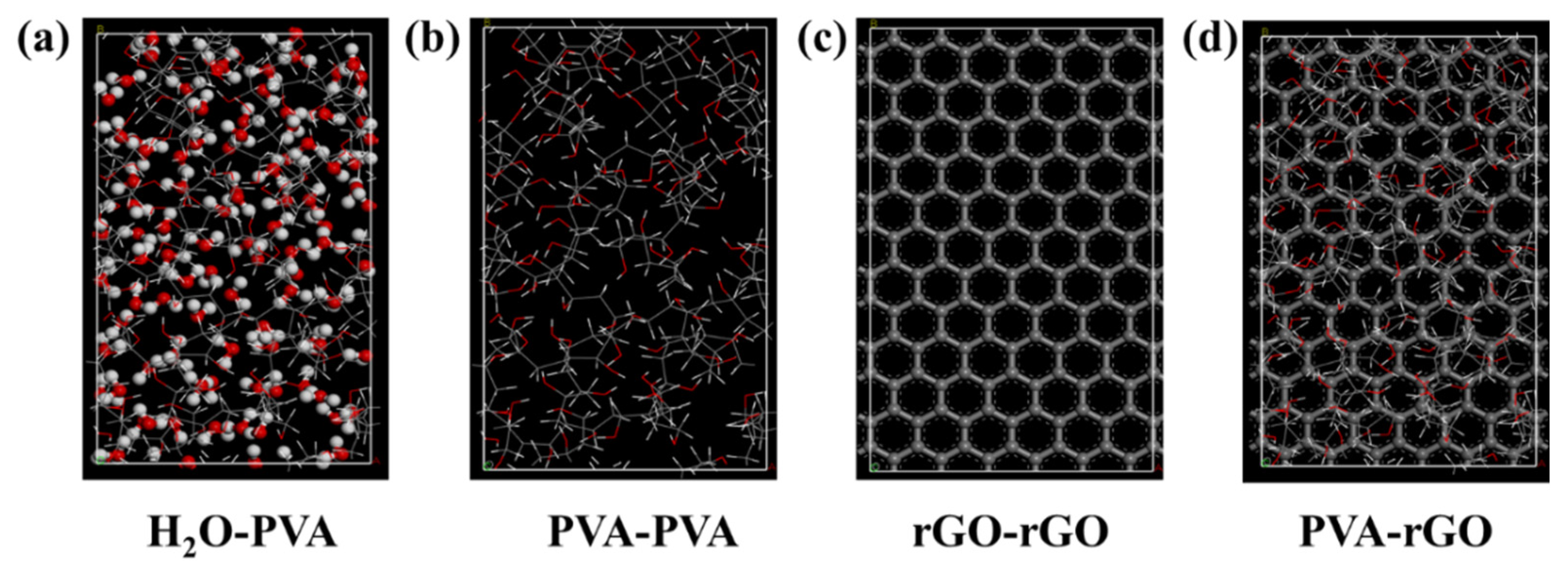

3 with the Amorphous cell module, and from that built an initial atactic polymer chain of 10 repeat units. Finally, we built the PVA-graphene model (as shown in

Figure 5). We performed geometry optimization (≤ 5000 iterations) and dynamics on the layer, followed by a calculation of the interaction energies ΔE of the PVA-graphene system.

We also constructed the MD model in a 3D-periodic 19.2×16.6×51.9 Å simulation cell (as shown in

Figure 6). This system was equilibrated with COMPASS III at 300 K (controlled by the Nose thermostat) in the NPT ensemble for 50 ps in 1 fs time steps. We treated the van der Waals interaction with the atom-based method and the electrostatic interaction with the Ewald method. We employed a non-bonding cutoff distance of 1.25 nm (with a spline width of 0.1 nm and a buffer width of 0.05 nm) to evaluate the non-bonding interactions.

In additon, the molecular formulas employed took into account the ideal scenario (i.e., the situation where rGO completely removes all oxygen atoms, it can be represented by graphene) to investigate the binding energy between PVA and rGO. Under ideal conditions, the calculated binding strength of the PVA - rGO system is lower than that in the actual situation. In reality, rGO has defects, which increases the interfacial strength between rGO and PVA [

11,

12]. The oxygen atoms on the surface of rGO can form hydrogen-bonding interactions with PVA, leading to a greater interaction strength [

13,

14,

15]. Nevertheless, this does not affect the specific ranking of the interaction strength and the verification and analysis of the self-assembly mechanism.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Polymer/rGO Composite Films Prepared from Solution Casting and Their Electrical Properties

Recently, graphene has been widely used as functional filler to fabricate multifunctional polymer/graphene composites due to its excellent properties [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. It is well known that most polymers are electrically insulating [

21,

22,

23]. However, because of its high electrical conductivity (106 S/cm), even a small amount of graphene content can significantly reduce the electrical insulation performance of the polymer, and greatly hindered its application when electrical insulation is required [

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

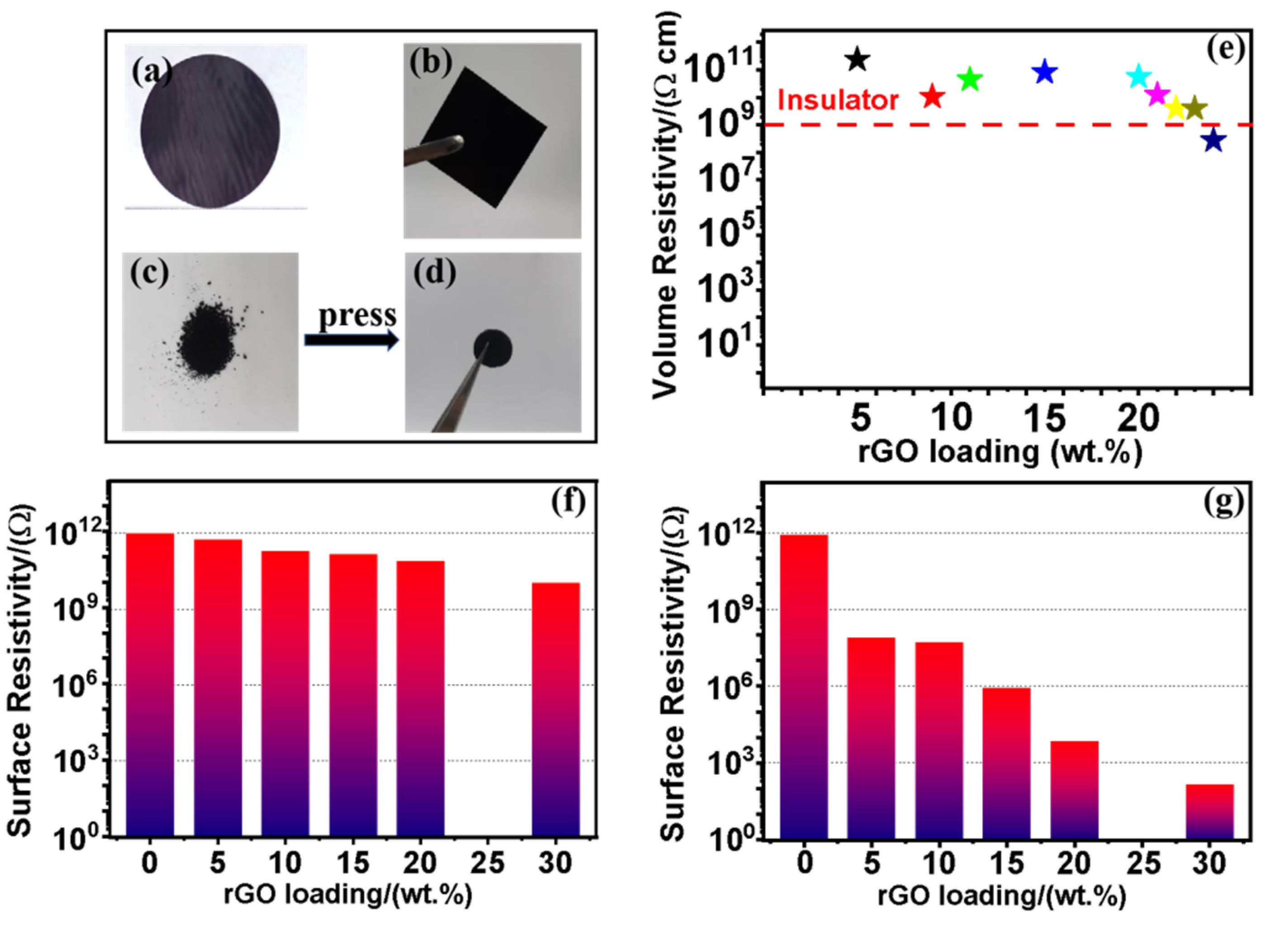

29]. It is interesting that different phenomenon is discovered in this work. Photographs of the PVA/rGO and ES/rGO composite film we prepared are shown in

Figure 2a and

Figure 2b, respectively. For comparison, the ES/rGO powder sample is also fabricated and shown in

Figure 2c,d.

The experimental results showed that the volume resistivity of PVA/rGO composite films generally decreased as the filler content increased (

Figure 2e). However, even at 23% rGO (w/w), the volume resistivity of the composite film was still as high as 3.92×10

9 Ω·cm, indicating good electrical insulation. When the rGO content was increased to 24% (w/w), the volume resistivity of PVA/rGO composite film dropped below the insulation level (10

9 Ω·cm). Similarly, the surface resistance of ES/rGO composite films and ES/rGO composite powder samples decreased with increasing rGO, as shown in

Figure 2f,g. At 30% rGO (w/w), the surface resistance of the composite films (powder samples) was 9.7×10

9 Ω (1.5×10

2 Ω). Therefore, we conclude that the polymer/rGO composite films we prepared by solution casting method maintain good electrical insulation properties under high rGO content, while the powder samples do not.

3.2. Accumulation of PVA and ES on the Surface of Polymer/rGO Composite Films

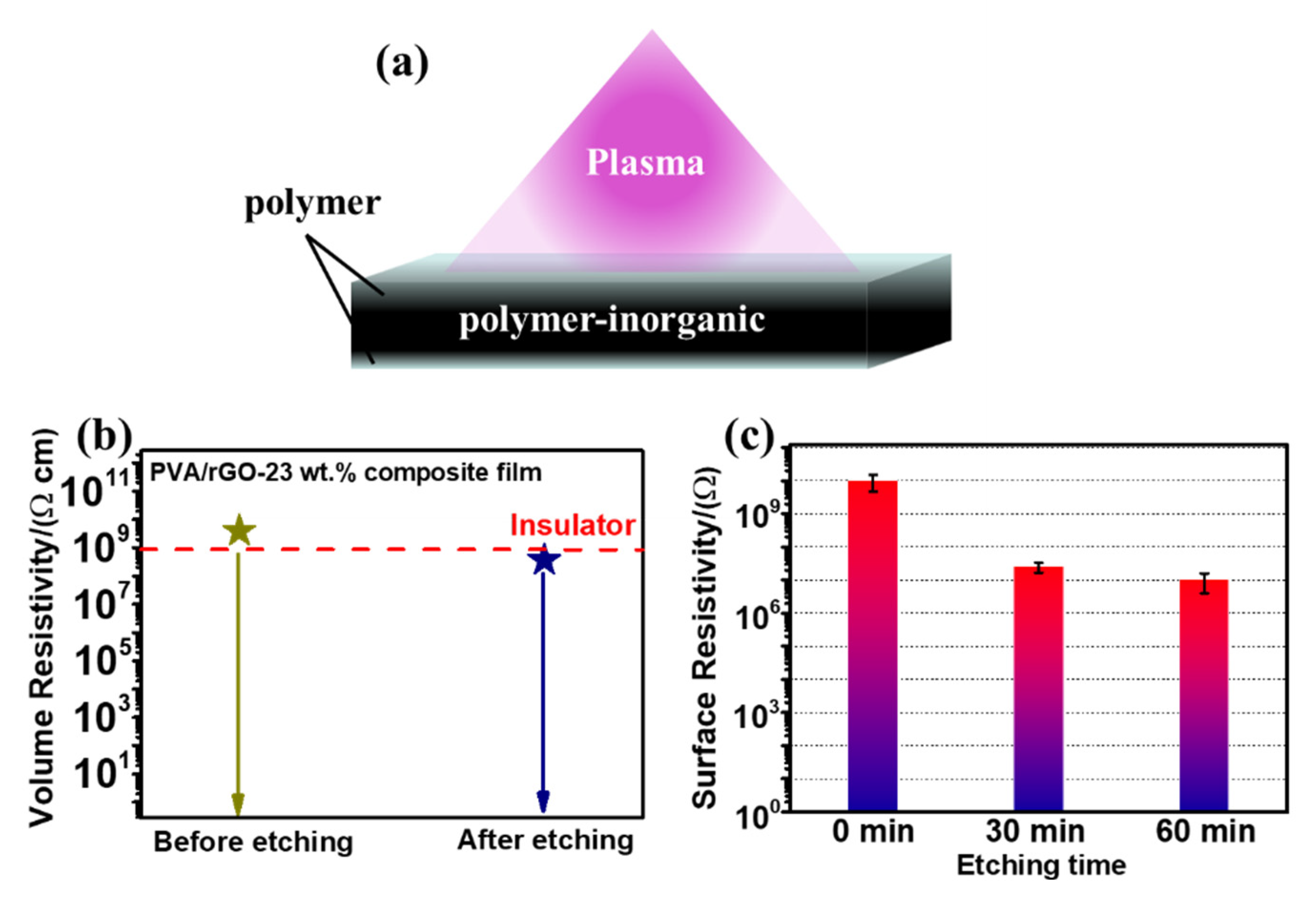

To explore why the polymer/rGO composite films we prepared maintained good electrical insulation performance at high rGO content, both sides of the PVA/rGO-23 wt.% and ES/rGO-30 wt.% composite films were treated by plasma etching [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34], as shown in

Figure 3a. Surprisingly, the volume resistivity of the PVA/rGO-23 wt.% composite film after etching for 20 min decreased to 3.69×10

8 Ω·cm, lower than that before etching, as shown in

Figure 3b. The surface resistivity of ES/rGO-30 wt.% decreased by two orders of magnitude (from 9.7×10

9 to 1.0×10

7 Ω) when etched for 60 min (as shown in

Figure 3c). Therefore, we can infer that the polymer/rGO composite films we prepared by the solution casting method are not uniform, and the surface layer has an important effect on the insulating ability of the entire film.

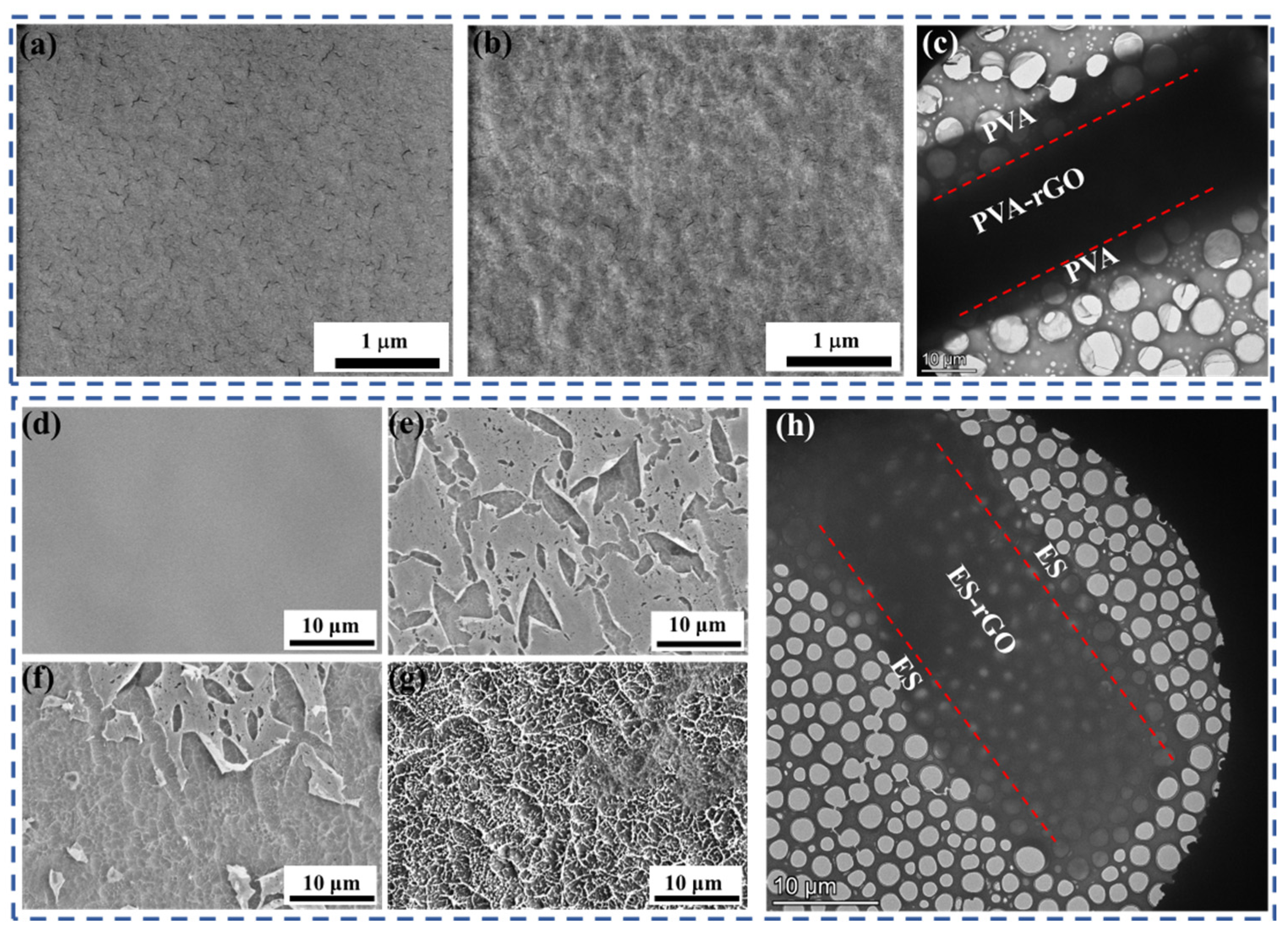

To further confirm our conjecture, the surface morphology changes of polymer/rGO composite films before and after etching were observed with SEM. Before etching, the surface of PVA/rGO composite film was flat and smooth (

Figure 4a), but after 20 minutes of etching, the surface of the composite film became rough (

Figure 4b). The surface of the ES/rGO-30 wt.% composite film behaved similarly; it was very smooth, without damage and unevenness, before etching (

Figure 4d). As etching time increased, the surface of composite film also became rough (

Figure 4e–g), and tiny defects were already visible on the surface after 10 min of etching (

Figure 4f); after 30 min, the surface layer was almost completely etched away, and the rGO fillers in the composite film were exposed (

Figure 4g). SEM results provide further evidence that our polymer/rGO composite films are not uniform. It is worth noting that the cross-section microstructures of the polymer/rGO composite films all have an obvious sandwich structure, as shown in

Figure 4c,h. This structure also indicates the nonuniformity of the polymer/rGO composite films we prepared. According to the previous research [

10,

35], the transparent layers distributed above and below the sandwich are composed solely of the polymer, while the darker middle layer is a polymer-rGO composite.

The solution casting method is vital to the self-assembly of the pure polymer layer on the surface of the polymer/rGO composite film. Specifically, as the solution dries to form the film, surface tension directs the polymer with a lower surface energy to aggregate to the side of the film closest to the air [

36,

37,

38]. Thus, the surface layer of the final composite film will be coated by a layer of pure polymer. It is therefore pure PVA and ES accumulated on the surface of PVA/rGO and ES/rGO that produces their good electrical insulation performance at high rGO content.

3.3. Molecular dynamics simulation of PVA assembly on the PVA/rGO surface

We next investigated the molecular mechanism of the surface layer’s formation computationally, choosing to study the PVA/rGO composite film. We ran molecular dynamics simulations with the Forcite and Amorphous Cell Module on Materials Studio 2020 software from Accelrys. We computed the interaction energy

ΔE between PVA and rGO as the following equation:

where

EPVA-rGO,

EPVA, and

ErGO represent the total energy of the PVA-rGO system, optimized rGO, and optimized PVA respectively. When the interaction energy

ΔE is negative, the composite is more stable than the constituents, indicating attraction. On the contrary, the addition of inorganic media increases the system energy, indicating repulsion. To judge the attraction or repulsion of each component of PVA/rGO, we computed the analogous interaction energies for PVA-PVA, PVA-H

2O, rGO-rGO and PVA-rGO with the COMPASS III force field (see

Figure 5); the results are listed in

Table 1. We found that the interaction strength follows the order PVA-H

2O > PVA-PVA > rGO-rGO > PVA-rGO, suggesting that PVA tends to be carried to the surface of the composite film by water molecules during solution evaporation.

Figure 6 shows one MD trajectory and vividly illustrates the aggregation behavior of PVA on the composite surface at the molecular level.

The analysis of the results of the dynamic process is carried out under the condition that the model reaches the equilibrium. There are many parameters to judge whether a system has reached the equilibrium process, such as the system energy, temperature, density, etc. The most commonly used parameters are the energy and temperature of the system.

Figure S1a,b showed the system temperature change over the MD simulation time.

Figure S1c,d displayed the system energy change at various simulation times. The simulation results show that the system reaches equilibrium at about 4ps. It can be seen clearly, driven by the evaporation of water molecules, the polymer tends to move up and down sides of the composite, while the graphene sheets tend to slip only horizontally due to the stronger interaction energies

ΔE (graphene-graphene> PVA-graphene). The simulation results can well explain the aggregation behavior of polymer on the surface of composite materials from the molecular level.

3.4. Extension to More Polymer/Inorganic Composite Films

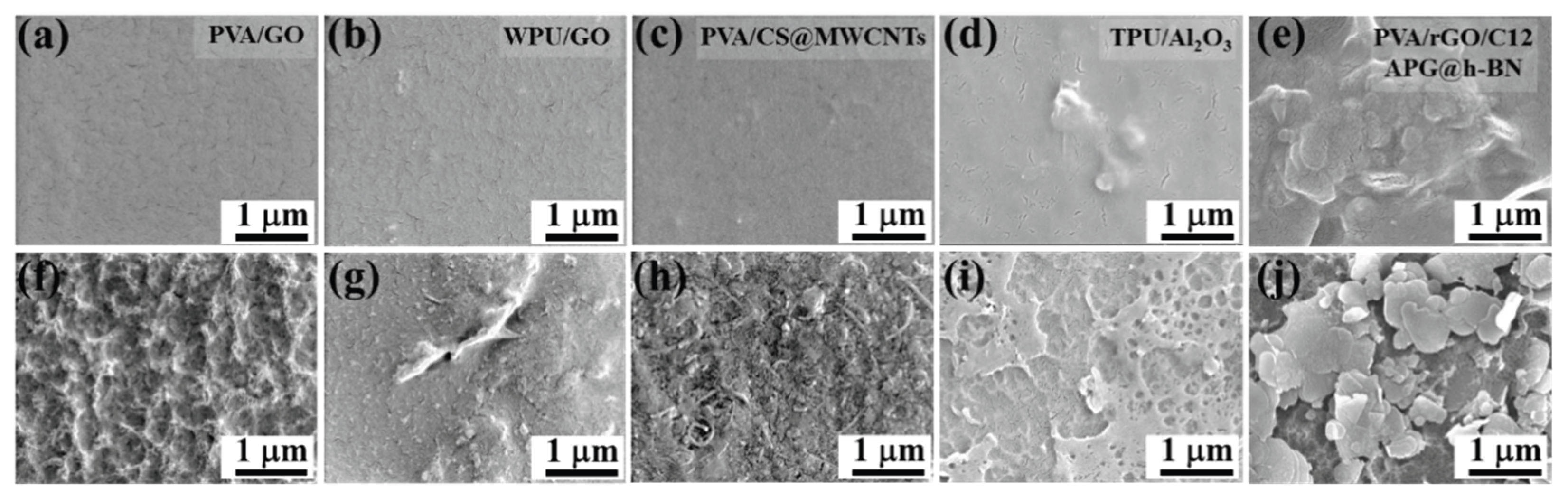

The surface polymer assembly investigated above is promising for the design and preparation of multifunctional polymer-inorganic composites. It is therefore worthwhile to extend this phenomenon to composite films containing non-water-soluble polymers, non-hydrophilic inorganic fillers, and organic solvents.

Figure 7a–e displayed the SEM images of the PVA/GO, WPU/GO, PVA/CS@MWCNTs, TPU/Al

2O

3 (using dimethylformamide as the solvent), and PVA/rGO/h-BN composite film fabricated by solution casting method before etching, and corresponding SEM images after etching were shown in

Figure 7f–j, respectively. The experimental results show that the surface of composite films all became coarser because the surface layer was etched away, and fillers were exposed after etching. In particular, the MWCNTs in PVA/CS@MWCNTs and the h-BN nanosheets in PVA/rGO/h-BN composite film were completely exposed. Based on the above discussions for PVA/rGO and ES/rGO, we can also infer that a layer of pure polymer also accumulates on the surface of these composite films, even when organic solvent, insoluble polymer matrices, and non-hydrophilic inorganic fillers are used. Thus, we speculate that the self-assembly of a polymer layer on the surface of the composites may be a universal phenomenon for polymer-inorganic composite films fabricated via solution casting method.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we prepared the polymer/rGO composite film and investigated the specific mechanism of the sandwich structure formation through MDS. The characterization results of the experimental samples show that polymer self-assembled on the surface of PVA/rGO (ES/rGO) composite film maintain good electrical insulation performance, even at high rGO content. MDS results demonstrate that the interaction energy ΔE between each pair of components of the PVA/rGO composite film varies; from strongest to weakest interaction energy, PVA-H2O > PVA-PVA > rGO-rGO > PVA-rGO. We ascribe PVA self-assembly on the surface of PVA/rGO to the stronger interaction between PVA and water molecules, which is the key factor for the formation of the sandwich structure. The spontaneous assembly of polymers on the surface of polymer-inorganic composite films provides a new strategy for designing multiple anisotropic materials; it could be applied to many composite materials, allowing the realization of different thermal and electrical properties inside the same material.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author contributions: Fanghua Luo conceived the manufacturing procedure and experiments and wrote the original draft. Xueli Ma and Zhitao Dong assisted in completing the experiment. Huaiyuan Wang revised the original manuscript and supervised the work. Fanghua Luo and Guohua Chen offered financial support.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (51373059), Science and Technology Projects in Fujian province (2021H6027), Northeast Petroleum University Talent Introduction Research Start-up Funding Project (13051202303), Daqing Guiding Science and Technology Plan Project (Zd-2024-09), and the Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Fund (LBH-Z24103).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no interest conflict.

References

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Che, Y.; Han, X.; Jiang, F. Cellulose Nanofibrils Enhanced, Strong, Stretchable, Freezing-Tolerant Ionic Conductive Organohydrogel for Multi-Functional Sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2003430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Zhou, H.; Liu, B.; Li, H.; Du, Z.; Zhang, C. Study on the Effect of Dispersion Phase Morphology on Porous Structure of Poly (Lactic Acid)/Poly (Ethylene Terephthalate Glycol-Modified) Blending Foams. Polymer 2013, 54(21), 5839–5851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, N.; Tan, Z. Kinetics and Characterization of Preparing Conductive Nanofibrous Membrane by In-Situ Polymerization of Polypyrrole on Electrospun Nanofibers. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 433, 133531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, R.; Zhao, H.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Dai, N.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, E.; Lv, F.; Huang, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. In Situ Synthesis of Photoactive Polymers on a Living Cell Surface via Bio-Palladium Catalysis for Modulating Biological Functions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60(11), 5759–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Kunikyo, N.; Kanda, M.; Lebrun, L.; Guyomar, D. Impact Value of High Electric Conductive ABS Composites with Copper Powder Dispersion Prepared by Solution-Cast Method. Mater. Trans. 2010, 51(1), 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksman, K.; Aitomaki, Y.; Mathew, A.P.; Siqueira, G.; Zhou, Q.; Butylina, S.; Tanpichai, S.; Zhou, X.; Hooshmand, S. Review of the Recent Developments in Cellulose Nanocomposite Processing. Compos. Part A-Appl. S. 2016, 83, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.H.; Dong, Z.T.; Chen, G.H.; Ma, C.; Wang, H.Y. Preparation of PVA/GO/h-BN Janus Film with High Thermal Conductivity and Excellent Flexibility via a Density Deposition Self-Assembly Method. Chinese J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 42(8), 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Ma, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhu, M.; Lei, W.; Song, P. Scalable, Robust, Low-Cost, and Highly Thermally Conductive Anisotropic Nanocomposite Films for Safe and Efficient Thermal Management. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32(8), 2110782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Cheng, W.; Wang, X.; Pan, L.; Xu, B.; Xu, H. A Self-Healable, Highly Stretchable, and Solution Processable Conductive Polymer Composite for Ultrasensitive Strain and Pressure Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28(7), 1705551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Zhang, M.; Chen, S.; Xu, J.; Ma, C.; Chen, G. Sandwich-Structured PVA/rGO Films from Self-Construction with High Thermal Conductivity and Electrical Insulation. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2021, 207, 108707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.C.; Grossman, J.C. Atomistic Understandings of Reduced Graphene Oxide as an Ultrathin-Film Nanoporous Membrane for Separations. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, J.S.; Shi, R.R.; Xie, H.N. Defects Induced the Bilayer Graphene-Copper Hybrid and Its Effect on Mechanical Properties of Graphene Reinforced Copper Matrix Composites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 644, 158762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, J.C.; Li, Y.B.; Yang, C.Y.; Luo, W. Hydroxyl-Binding Induced Hydrogen Bond Network Connectivity on Ru-Based Catalysts for Efficient Alkaline Hydrogen Oxidation Electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 64(3), e202415447. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson, M.K.; Sumpter, B.G.; Demchuk, Z. High-Performance Reversible Adhesive from PET Waste for Underwater, Structural, and Pressure-Sensitive Applications. Sci. Adv. 2025, 11(30), eadw1288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, N.J.; Chen, A.C.; Xing, J.F.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q. Nonclassical Hydrogen Bond-Based Efficient Solid-State Organic Emitters Enabled by a Synergistic Anion and Mechanical Bond Effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64(23), e202505774. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; An, C.; Guo, Y.; Zong, Y.; Jiang, N.; Zheng, Q.; Yu, Z.Z. Highly Aligned Graphene Aerogels for Multifunctional Composites. Nano-Micro Lett.

- Yan, Z.; Cai, X.; Liang, H.; Tang, J.; Gou, Q.; Wang, W.; Gao, Y.; Qin, M.; Tan, H.; Cai, J. Thermally Conductive Epoxy Resin Composites Based on 3D Graphene Nanosheet Networks for Electronic Package Heat Dissipation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7(11), 12644–12652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, G.; Zhang, C.; Wang, A.; Zhou, X.; Xing, X.; Liu, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, Q.; Lu, Q. Research Progress on Self-Healing Polymer/Graphene Anticorrosion Coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2021, 155, 106231. [Google Scholar]

- Croft, Z.L.; Valenzuela, O.; Thompson, C.; Whitfield, B.; Betzko, G.; Liu, G. Copper Oxidation-Induced Nanoscale Deformation of Electromechanical, Laminate Polymer/Graphene Thin Films during Thermal Annealing: Implications for Flexible, Transparent, and Conductive Electrodes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2024, 7(24), 28829–28840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, L.; Lopez, K.O.; Nair, A.B.; Desueza, W.; Agarwal, A. Micro-Mechanosensory Insights from Nature’s Mimosa Leaves to Shape Memory Adaptive Robotics. Mater. Design 2025, 249, 113567. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wu, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, F. Highly Thermal Conductivity Polymer Composites Reinforced by BNNS/UHMWPE Fabric for Reliable Electronic Thermal Protection and Management. Compos. Commun. 2024, 49, 101991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morishita, T.; Matsushita, M. Ultra-Highly Electrically Insulating Carbon Materials and Their Use for Thermally Conductive and Electrically Insulating Polymer Composites. Carbon 2021, 184, 786–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, P.; Alexis, L.; Lee, J.; Alvarez, G.A.; Brueggemann, A.; Santiago, D.; Lizcano, M.; Tian, Z. ELF/VLF Electromagnetic Interference Shielding by Low-Dimensional Conductors Embedded in Insulating Polymer Matrices. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 2423497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare, Y.; Munir, M.T.; Rhee, K.Y. From Nano to Macro in Graphene-Polymer Nanocomposites: A New Methodology for Conductivity Prediction. Colloid Surface A 2024, 703, 135353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goli, P.; Ning, H.; Li, X.; Lu, C.Y.; Novoselov, K.S.; Balandin, A.A. Thermal Properties of Graphene-Copper-Graphene Heterogeneous Films. Nano Lett. 2014, 14(3), 1497–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, T.; Ma, P.; Zhang, S.; Du, M.; Chen, M.; Dong, W.; Ming, W. Highly Thermal Conductive and Electrically Insulating Polymer Composites Based on Polydopamine-Coated Copper Nanowire. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2018, 164, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renteria, J.D.; Ramirez, S.; Malekpour, H.; Alonso, B.; Centeno, A.; Zurutuza, A.; Cocemasov, A.I.; Nika, D.L.; Balandin, A.A. Strongly Anisotropic Thermal Conductivity of Free-Standing Reduced Graphene Oxide Films Annealed at High Temperature. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25(29), 4664–4672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekpour, H.; Chang, K.H.; Chen, J.C.; Lu, C.Y.; Nika, D.L.; Novoselov, K.S.; Balandin, A.A. Thermal Conductivity of Graphene Laminate. Nano Lett. 2014, 14(9), 5155–5161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Mueller, M.B.; Gilmore, K.J.; Wallace, G.G.; Li, D. Mechanically Strong, Electrically Conductive, and Biocompatible Graphene Paper. Adv. Mater. 2008, 20(18), 3557–3561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barz, J.; Haupt, M.; Oehr, C.; Hirth, T.; Grimmer, P. Stability and Water Wetting Behavior of Superhydrophobic Polyurethane Films Created by Hot Embossing and Plasma Etching and Coating. Plasma Process. Polym. 2019, 16(6), e1800214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, D.; Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, J.; Zhao, N.; Wong, C.-P. A Facile, Low-Cost Plasma Etching Method for Achieving Size Controlled Non-Close-Packed Monolayer Arrays of Polystyrene Nano-Spheres. Nanomaterials 2019, 9(4), 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrakellis, P.; Gogolides, E. Atmospheric Plasma Etching of Polymers: A Palette of Applications in Cleaning/Ashing, Pattern Formation, Nanotexturing and Superhydrophobic Surface Fabrication. Microelectron. Eng. 2018, 194, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memos, G.; Lidorikis, E.; Kokkoris, G. The Interplay between Surface Charging and Microscale Roughness during Plasma Etching of Polymeric Substrates. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123(7), 073303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda Spyrides, S.M.; Alencastro, F.S.; Guimaraes, E.F.; Bastian, F.L.; Simao, R.A. Mechanism of Oxygen and Argon Low Pressure Plasma Etching on Polyethylene (UHMWPE). Surf. Coat. Tech. 2019, 378, 124990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, F.; Ma, C.; Tang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Ding, Y.; Chen, G. Sandwich-Structured Flexible PVA/CS@MWCNTs Composite Films with High Thermal Conductivity and Excellent Electrical Insulation. Polymers 2022, 14(12), 2512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Archer, L.A. Functionalizing Polymer Surfaces by Field-Induced Migration of Copolymer Additives. 1. Role of Surface Energy Gradients. Macromolecules 2001, 34(13), 4572–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, L.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Y.; Du, X. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Cross-Linked Epoxy Resin and Its Interaction Energy with Graphene under Two Typical Force Fields. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2018, 143, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.R.; Rashid, H.O.; Kareem, M.T.; Tang, C.-S.; Manolescu, A.; Gudmundsson, V. Effects of Bonded and Non-Bonded B/N Codoping of Graphene on Its Stability, Interaction Energy, Electronic Structure, and Power Factor. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384(12), 126350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).