Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

24 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

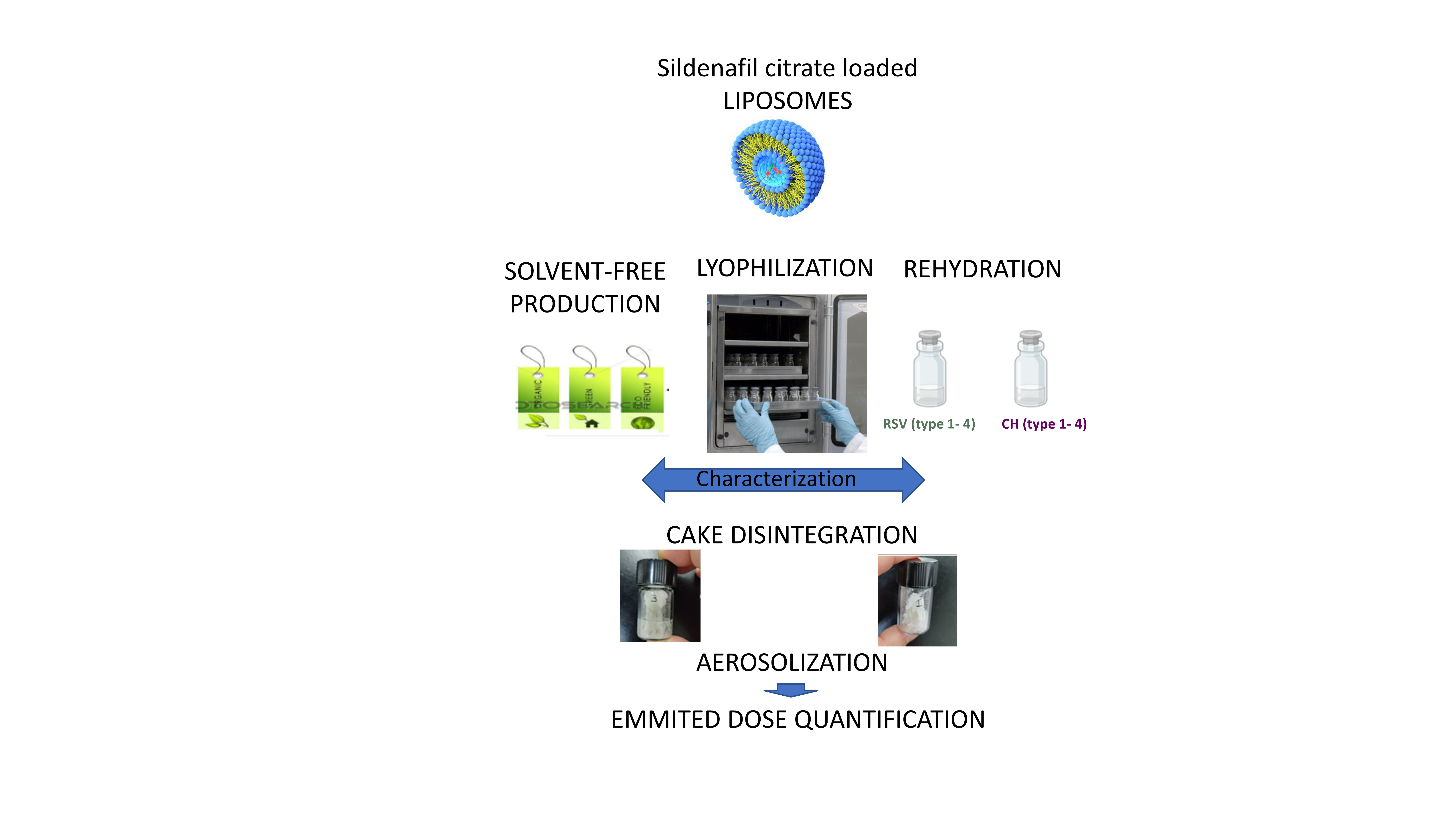

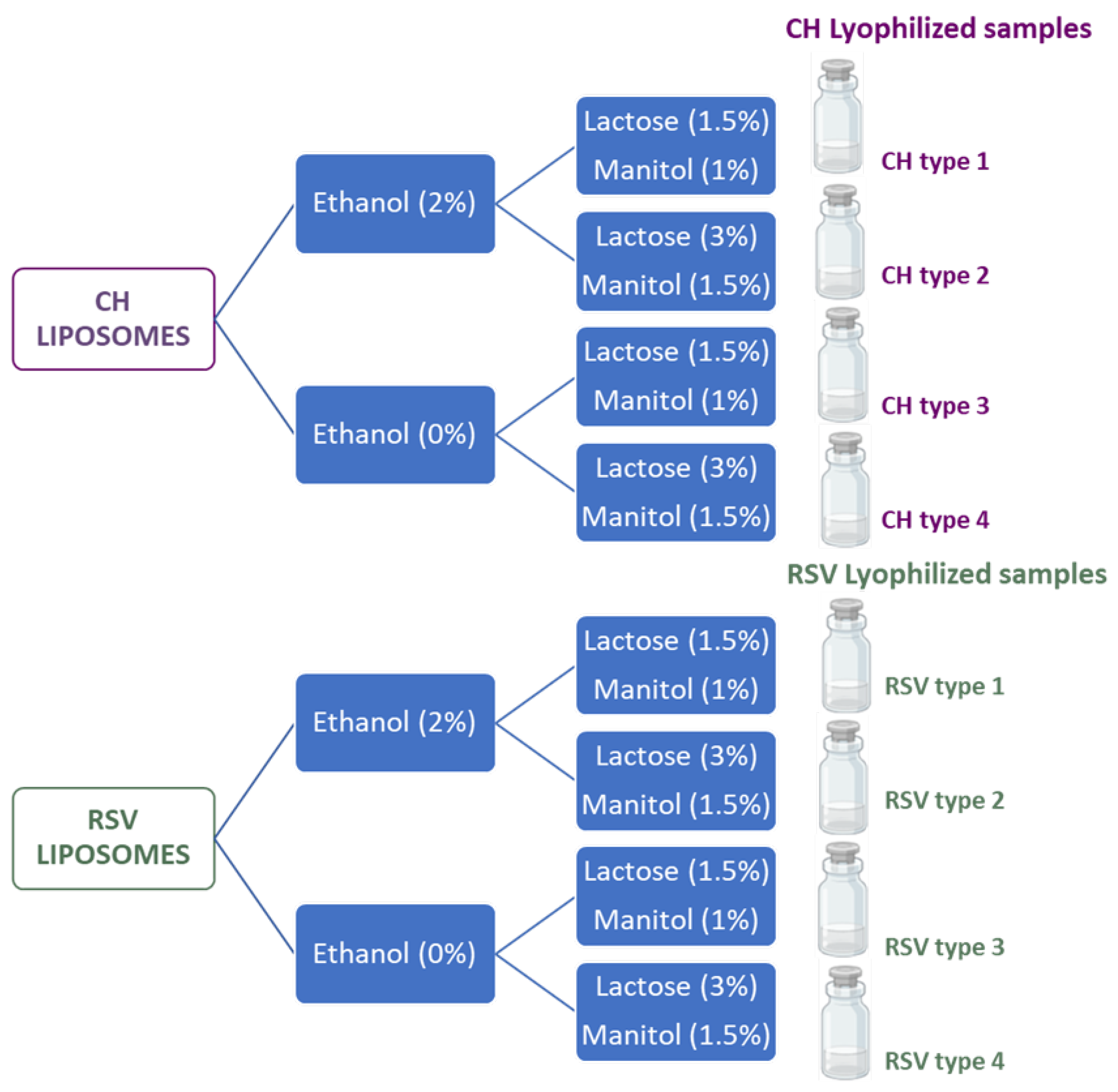

Pulmonary drug delivery is a promising approach for the treatment of respiratory diseases allowing for passive drug targeting and enhanced drug efficacy. Background/Objectives: The aim of the present study was to develop inhalable dry powders from lyophilized sildenafil citrate (SC) loaded liposomes made of phosphatidylcholine and either cholesterol (CH) or resveratrol (RSV). Methods: Liposomes were prepared via a pH gradient method to increase drug entrapment efficiency and drug loading and then the lipid vesicles were lyophilized using different proportions of ethanol, mannitol and lactose as excipients. The resulting dry cakes were converted into powders and evaluated for aerodynamic performance using a custom-designed air-blowing device. Notably, this is the first time that resveratrol has been used as a substitute for cholesterol in SC loaded liposomes. Results: The obtained results demonstrate that RSV is a suitable component of liposome bilayer that improves drug loading and probe that lyophilized cakes containing the liposomes produced a dry powder suitable for aerosolization and pulmonary delivery of sildenafil citrate. The results found for RSV liposomes point to this polyphenol offering a potential alternative to traditional cholesterol-based liposomal formulations. Conclusions: This approach presents a novel strategy for pulmonary delivery of sildenafil using biocompatible and FDA-approved excipients for this administration route.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

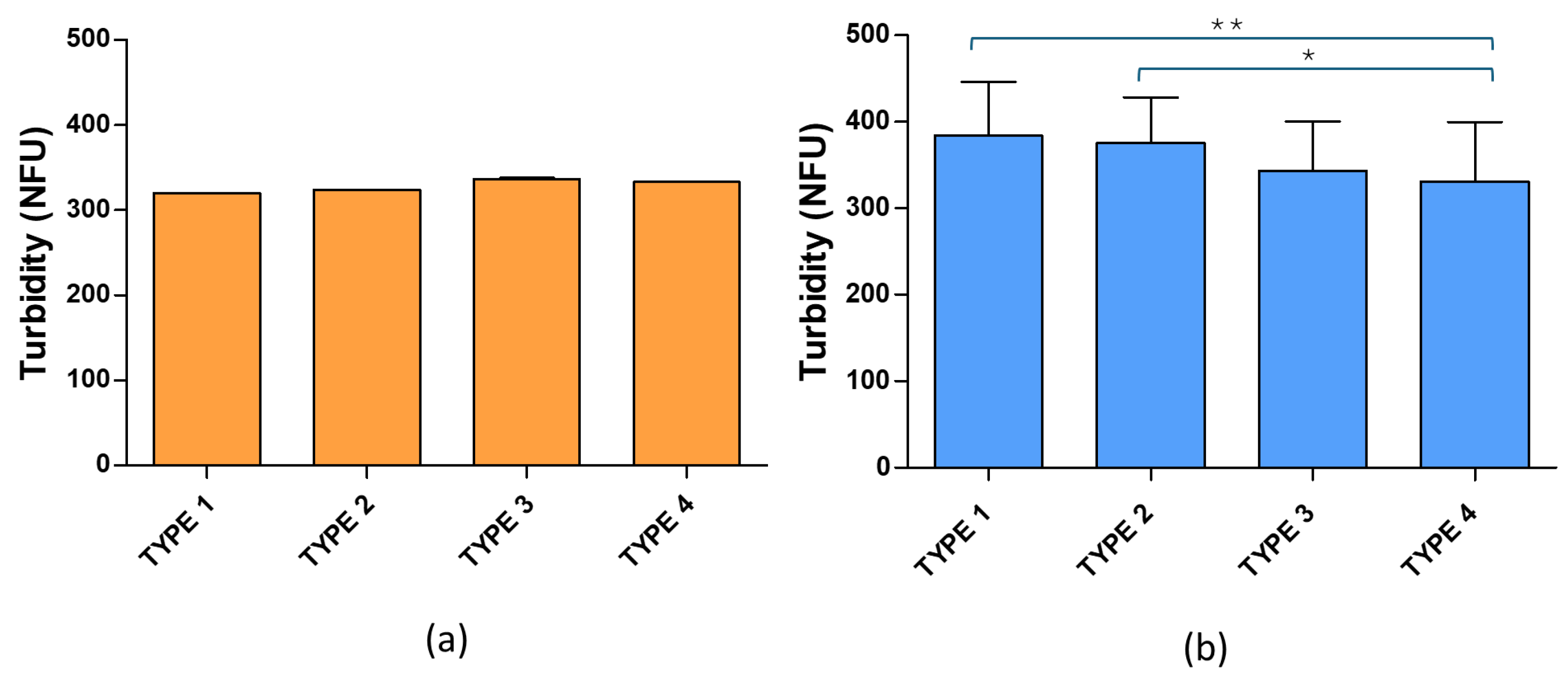

2.1. Liposomes

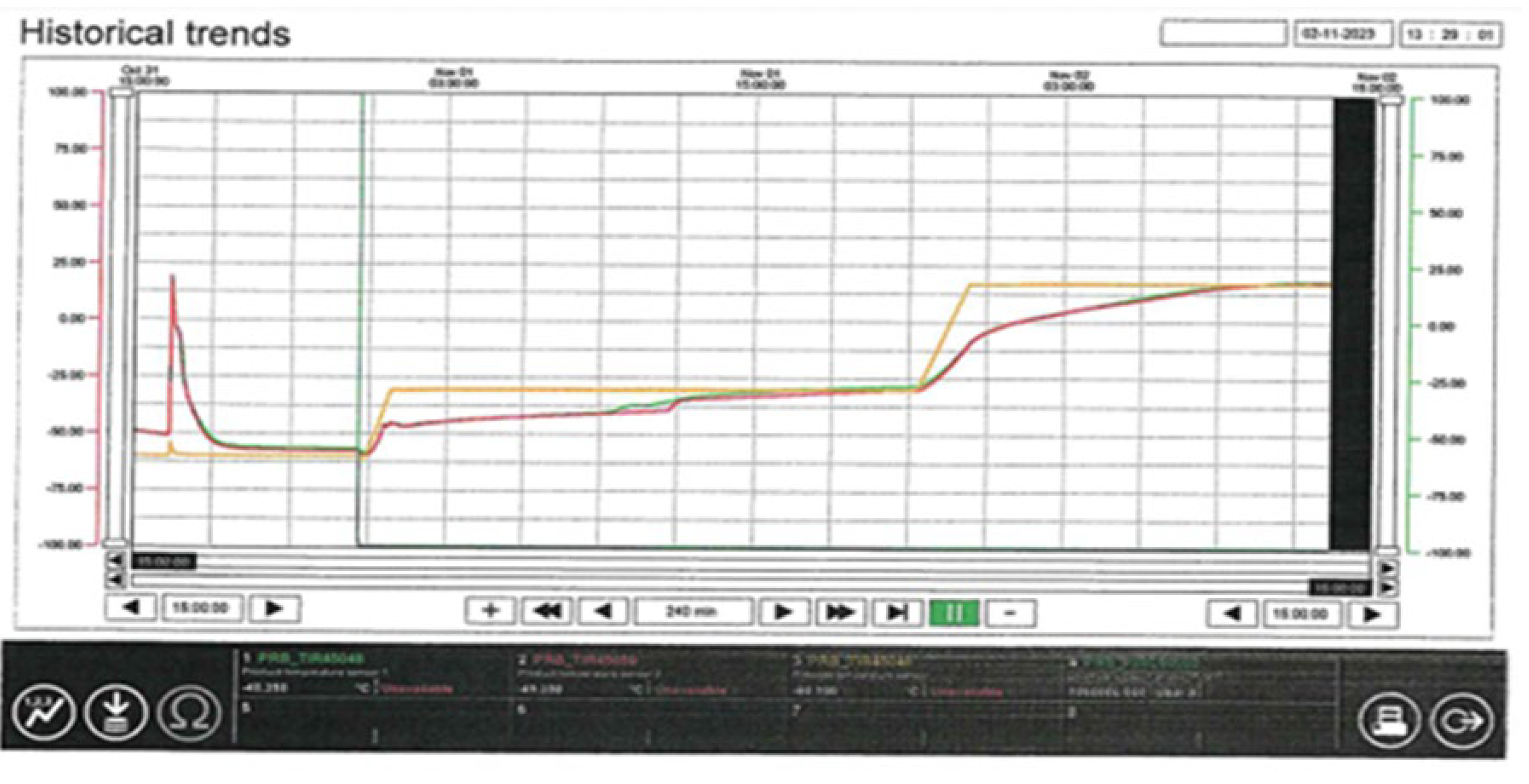

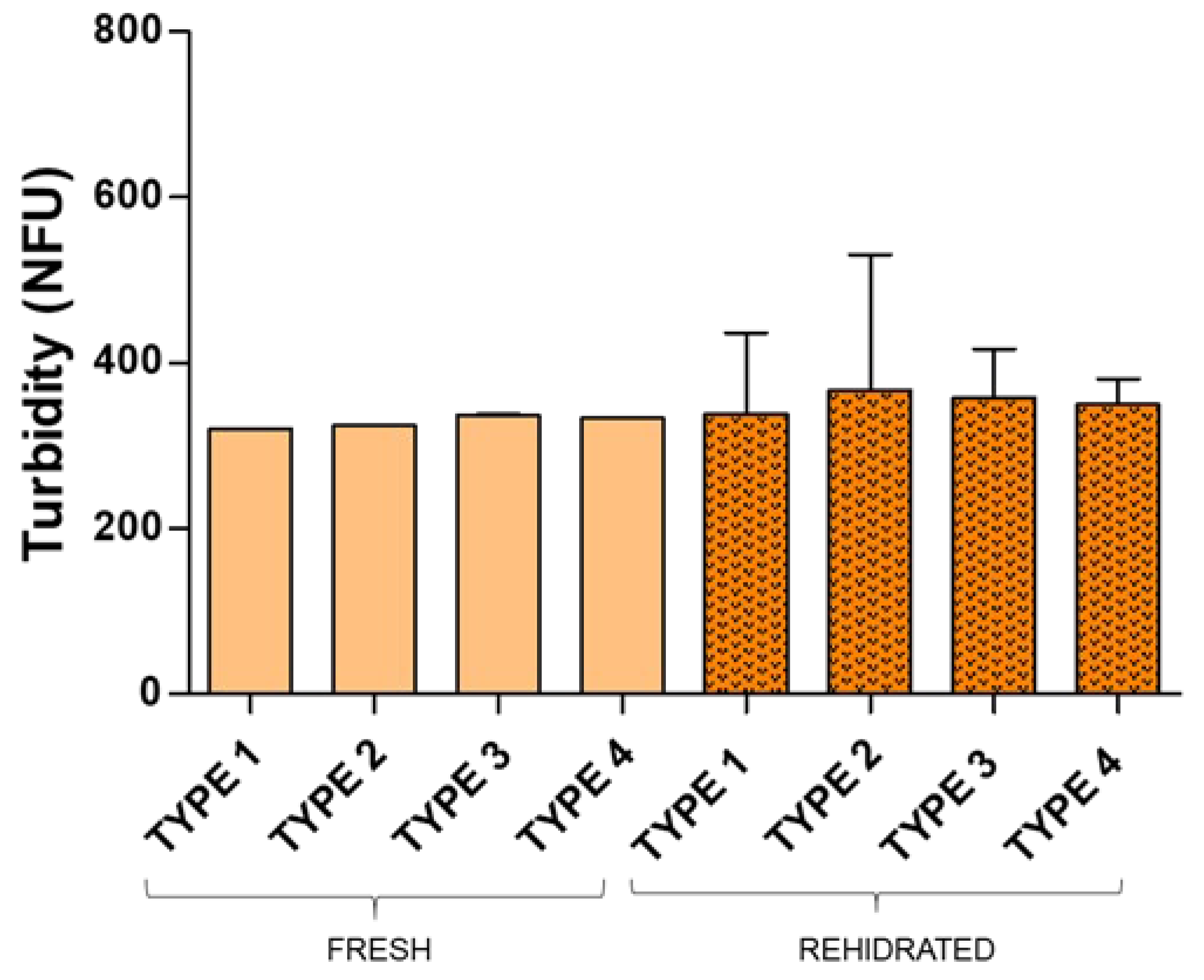

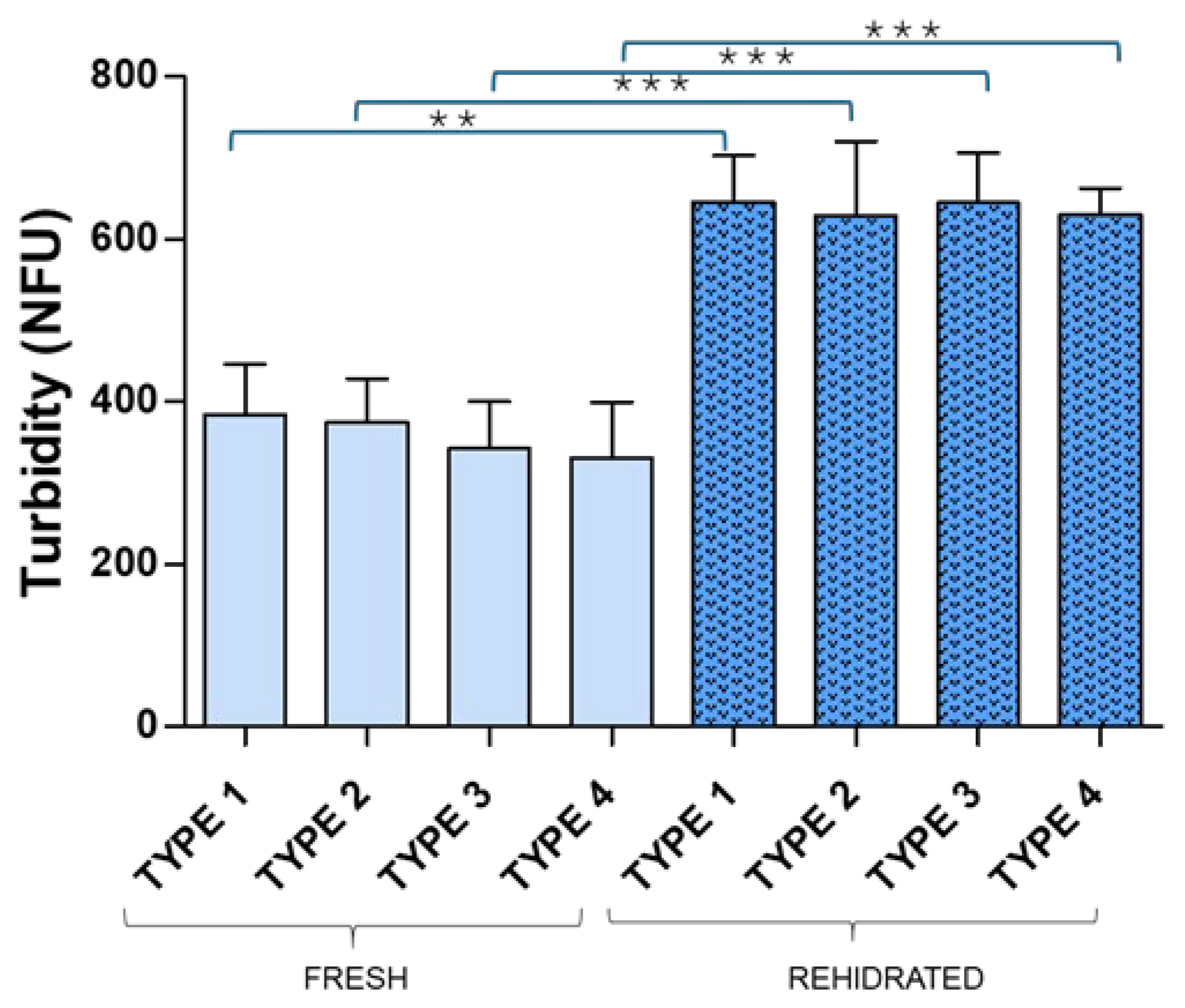

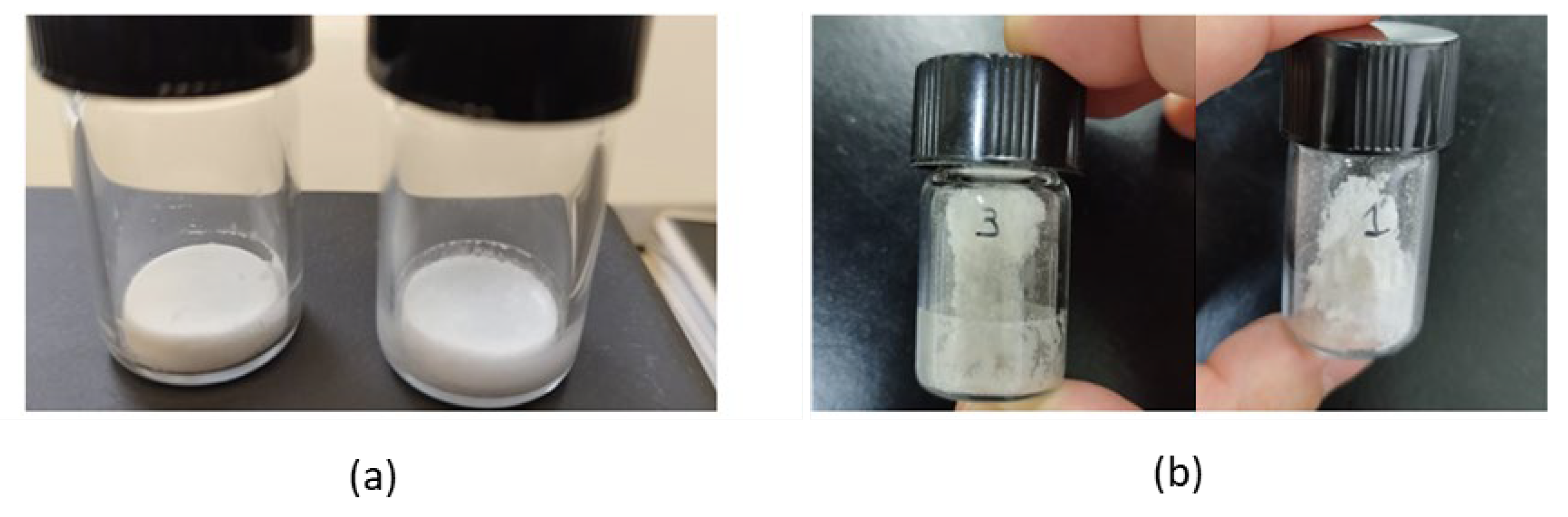

2.2. Lyophilization

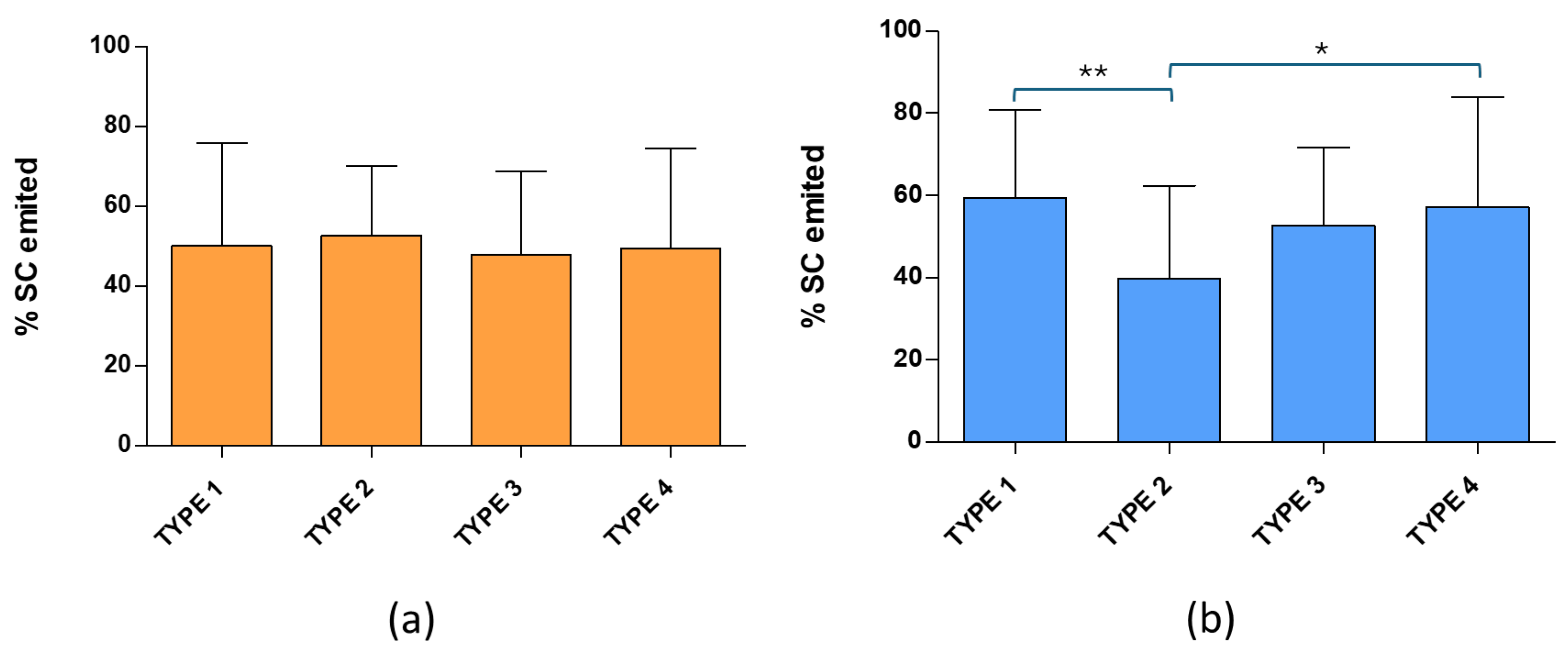

2.3. Dry Powders

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials

3.2. Liposome Preparation and Characterization

3.3. Lyophilization

3.4. Dry Powders

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaikwad, S.S.; Pathare, S.R.; More, M.A.; Waykhinde, N.A.; Laddha, U.D.; Salunkhe, K.S.; Kshirsagar, S.J.; Patil, S.S.; Ramteke, K.H. Dry powder inhaler with the technical and practical obstacles, and forthcoming platform strategies. J. Control. Release 2023, 355, 292–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, P.P.; Ghoshal, D.; Pawar, A.P.; Kadam, S.S.; Dhapte-Pawar, V.S. Recent advances in inhalable liposomes for treatment of pulmonary diseases: Concept to clinical stance. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 56, 101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzmov, A.; Minko, T. Nanotechnology approaches for inhalation treatment of lung diseases. J. Control. Release 2015, 219, 500–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, A.M.; Minko, T. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled nanotherapeutics for pulmonary delivery. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 222–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhu, J. The future of dry powder inhaled therapy: Promising or discouraging for systemic disorders? Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 614, 121457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhege, C.T.; Kumar, P.; Choonara, Y.E. Pulmonary drug delivery devices and nanosystems as potential treatment strategies for acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 657, 124182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Gui, J.; Xiong, K.; Chen, M.; Gao, H.; Fu, Y. A roadmap to pulmonary delivery strategies for the treatment of infectious lung diseases. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2022, 20, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulbake, U.; Doppalapudi, S.; Kommineni, N.; Khan, W. Liposomal formulations in clinical use: An updated review. Pharmaceutics 2017, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ngan, C.L.; Asmawi, A.A. Lipid-based pulmonary delivery system: A review and future considerations of formulation strategies and limitations. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2018, 8, 1527–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dushianthan, A.; Grocott, M.P.W.; Murugan, G.S.; Wilkinson, T.M.A.; Postle, A.D. Pulmonary surfactant in adult ARDS: Current perspectives and future directions. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, A.I.; Acosta, M.F.; Muralidharan, P.; Yuan, J.X.-J.; Black, S.M.; Hayes, D.; Mansour, H.M. Advanced spray dried proliposomes of amphotericin B lung surfactant-mimic phospholipid microparticles/nanoparticles as dry powder inhalers for targeted pulmonary drug delivery. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 64, 101975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, J.; Vogt, F.G.; Li, X.; Hayes, D.; Mansour, H.M. Design, characterization, and aerosolization of organic solution advanced spray-dried moxifloxacin and ofloxacin dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine (DPPC) microparticulate/nanoparticulate powders for pulmonary inhalation aerosol delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2013, 8, 3489–3505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, L.; Hayes, D.; Mansour, H.M. Therapeutic liposomal dry powder inhalation aerosols for targeted lung delivery. Lung 2012, 190, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Shou, Z.; Jin, X.; Chen, Y. Emerging strategies in nanotechnology to treat respiratory tract infections: Realizing current trends for future clinical perspectives. Drug Deliv. 2022, 29, 2442–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.L.; Nees, S.N.; Valencia, G.A.; Rosenzweig, E.B.; Krishnan, U.S. Sildenafil use in children with pulmonary hypertension. J. Pediatr. 2019, 205, 29–34.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unegbu, C.; Noje, C.; Coulson, J.D.; Segal, J.B.; Romer, L. Pulmonary hypertension therapy and a systematic review of efficacy and safety of PDE-5 inhibitors. Pediatrics 2017, 139, e20161450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benza, R.L.; Grünig, E.; Sandner, P.; Stasch, J.-P.; Simonneau, G. The nitric oxide–soluble guanylate cyclase–cGMP pathway in pulmonary hypertension: From PDE5 to soluble guanylate cyclase. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2024, 33, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J.M. Pulmonary hypertension: Recognition, diagnosis and management. Pharm. J. 2024. Available online: https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/pulmonary-hypertension-recognition-diagnosisand- management.

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; Ferreira, D.S.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Giannakoulas, G.; Kiely, D.G.; Mayer, E.; Meszaros, G.; Nagavci, B.; Olsson, K.M.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; Quint, J.K.; Rådegran, G.; Simonneau, G.; Sitbon, O.; Tonia, T.; Toshner, M.; Vachiery, J.L.; Vonk Noordegraaf, A.; Delcroix, M.; Rosenkranz, S. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lammi, M.R.; Mukherjee, M.; Saketkoo, L.A.; Carey, K.; Hummers, L.; Hsu, S.; Krishnan, A.; Sandi, M.; Shah, A.A.; Zimmerman, S.L.; Hassoun, P.M.; Mathai, S.C. Sildenafil versus placebo for early pulmonary vascular disease in scleroderma (SEPVADIS): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024, 24, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemian, E.; Vatanara, A.; Rouini, M.R.; Rouholamini Najafabadi, A.; Gilani, K.; Lavasani, H.; Mohajel, N. Inhaled sildenafil nanocomposites: Lung accumulation and pulmonary pharmacokinetics. Pharm. Dev. Technol. 2016, 21, 961–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paranjpe, M.; Finke, J.H.; Richter, C.; Gothsch, T.; Kwade, A.; Büttgenbach, S.; Müller-Goymann, C.C. Physicochemical characterization of sildenafil-loaded solid lipid nanoparticle dispersions (SLN) for pulmonary application. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 476, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makled, S.; Nafee, N.; Boraie, N. Nebulized solid lipid nanoparticles for the potential treatment of pulmonary hypertension via targeted delivery of phosphodiesterase-5-inhibitor. Int. J. Pharm. 2017, 517, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, H.; Vinjamuri, B.P.; Mahmoud, A.A.; Mansour, S.M.; Chougule, M.B.; Chablani, L. Formulation and optimization of sildenafil citrate-loaded PLGA large porous microparticles using spray freeze-drying technique: A factorial design and in-vivo pharmacokinetic study. Int. J. Pharm. 2021, 597, 120320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.A.; Abou-Saleh, H.; Kameno, Y.; Marei, I.; de Nucci, G.; Ahmetaj-Shala, B.; Shala, F.; Kirkby, N.S.; Jennings, L.; Al-Ansari, D.E.; Davies, R.P.; Lickiss, P.D.; Mitchell, J.A. Studies on metal-organic framework (MOF) nanomedicine preparations of sildenafil for the future treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesús Valle, M.J.; Alves, A.; Coutinho, P.; Prata Ribeiro, M.; Maderuelo, C.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Lyoprotective effects of mannitol and lactose compared to sucrose and trehalose: Sildenafil citrate liposomes as a case study. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Benfante, V.; Raimondo, D.D.; Salvaggio, G.; Tuttolomondo, A.; Comelli, A. Recent developments in nanoparticle formulations for resveratrol encapsulation as an anticancer agent. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jesús Valle, M.J.; Rondon Mujica, A.M.; Zarzuelo Castañeda, A.; Coutinho, P.; de Abreu Duarte, A.C.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Resveratrol liposomes in buccal formulations, an approach to overcome drawbacks limiting the application of the phytoactive molecule for chemoprevention and treatment of oral cancer. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2024, 98, 105910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, M.M.A.; Cevc, G. Turbidity spectroscopy for characterization of submicroscopic drug carriers, such as nanoparticles and lipid vesicles: Size determination. Pharm. Res. 2011, 28, 2204–2222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, A.-H.; Corti, D.S.; Franses, E.I. Rayleigh and Rayleigh-Debye-Gans light scattering intensities and spectroturbidimetry of dispersions of unilamellar vesicles and multilamellar liposomes. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 578, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jesús Valle, M.J.; Zarzuelo Castañeda, A.; Maderuelo, C.; Cencerrado Treviño, A.; Loureiro, J.; Coutinho, P.; Sánchez Navarro, A. Development of a mucoadhesive vehicle based on lyophilized liposomes for drug delivery through the sublingual mucosa. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boafo, G.F.; Magar, K.T.; Ekpo, M.D.; Qian, W.; Tan, S.; Chen, C. The role of cryoprotective agents in liposome stabilization and preservation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.Y.; Chuesiang, P.; Shin, G.H.; Park, H.J. Post-processing techniques for the improvement of liposome stability. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeagbo, B.A.; Alao, M.; Orherhe, O.; Akinloye, A.; Boukes, G.; Willenburg, E.; Fenner, C.; Bolaji, O.O.; Fox, C.B. Lyophilization strategy enhances the thermostability and field-based stability of conjugated and comixed subunit liposomal adjuvant-containing tuberculosis vaccine formulation (ID93 + GLA-LSQ). Mol. Pharm. 2025, 22, 2306–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, K.; Reddy, A.; Paliwal, R.; Chaurasiya, A. Dynamic intervention to enhance the stability of PEGylated ibrutinib loaded lipidic nano-vesicular systems: Transitioning from colloidal dispersion to lyophilized product. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2024, 14, 3269–3290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamal, A.; Saeed, H.; Sayed, O.M.; Kharshoum, R.M.; Salem, H.F. Proniosomal microcarriers: Impact of constituents on the physicochemical properties of proniosomes as a new approach to enhance inhalation efficiency of dry powder inhalers. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020, 21, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelrahim, M.E. Emitted dose and lung deposition of inhaled terbutaline from Turbuhaler at different conditions. Respir. Med. 2010, 104, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasero, L.; Susa, F.; Limongi, T.; Pisano, R. A review on micro and nanoengineering in powder-based pulmonary drug delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 659, 124248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, K.; Taga, H.; Akita, T.; Yamashita, C. Simple Method to Measure the Aerodynamic Size Distribution of Porous Particles Generated on Lyophilizate for Dry Powder Inhalation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).