Submitted:

21 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To systematically document and analyze the cyclical nature of infrastructure damage and the subsequent emergence of both formal and informal community-led responses to the chronic energy deficit.

- To apply the theoretical lenses of Energy Resilience and Energy Justice to critically evaluate the failures of the conventional reconstruction model and the socio-economic inequities embedded within the current energy landscape.

- To identify and assess viable pathways towards a more resilient, equitable, and sustainable energy future for Gaza, drawing lessons from both local innovations and international best practices in decentralized energy systems.

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Dominant Paradigm: Technical-Financial Approaches to Infrastructure Reconstruction

2.2. The Resilience Turn: From Robustness to Adaptive and Transformative Capacity

2.3. The Justice Imperative: Integrating Equity into Energy Systems

- Distributive Justice: Pertains to the equitable allocation of benefits (e.g., access to affordable, reliable electricity) and burdens (e.g., pollution from power plants, infrastructure costs, the impacts of blackouts) across all segments of society.

- Procedural Justice: Concerns the right to fair, transparent, and meaningful participation in energy decision-making processes for all stakeholders, regardless of race, class, or gender.

- Recognition Justice: Involves acknowledging and respecting the rights, needs, and unique vulnerabilities of different social groups, particularly marginalized and historically disadvantaged communities.

2.4. The Research Gap and the Positioning of Gaza

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design: A Qualitative Case Study Approach

3.2. Bounding the Case

- Temporally: The study primarily focuses on the period from 2007, marking the imposition of the full blockade, to the present. This timeframe allows for an analysis of the cumulative and cyclical impacts of repeated conflicts and prolonged restrictions on the energy sector.

- Spatially: The geographical boundary is the Gaza Strip, though the analysis necessarily considers external factors, including the supply of electricity and fuel from Israel and Egypt and the role of international donors.

- Conceptually: The unit of analysis is Gaza's socio-technical electricity system, encompassing not only the physical infrastructure (power plant, grid, solar panels) but also the key institutions (e.g., PENRA, GEDCO), governance structures, community-level actors, and the lived experiences of energy scarcity.

3.3. Data Sources and Collection Strategy

3.3.1. Official Reports and Grey Literature

-

Palestinian Energy and Natural Resources Authority (PENRA) and Gaza Electricity Distribution Company (GEDCO): These are the primary sources for technical and operational data. Their reports, though sometimes sporadic, provide critical statistics on:

- ◦

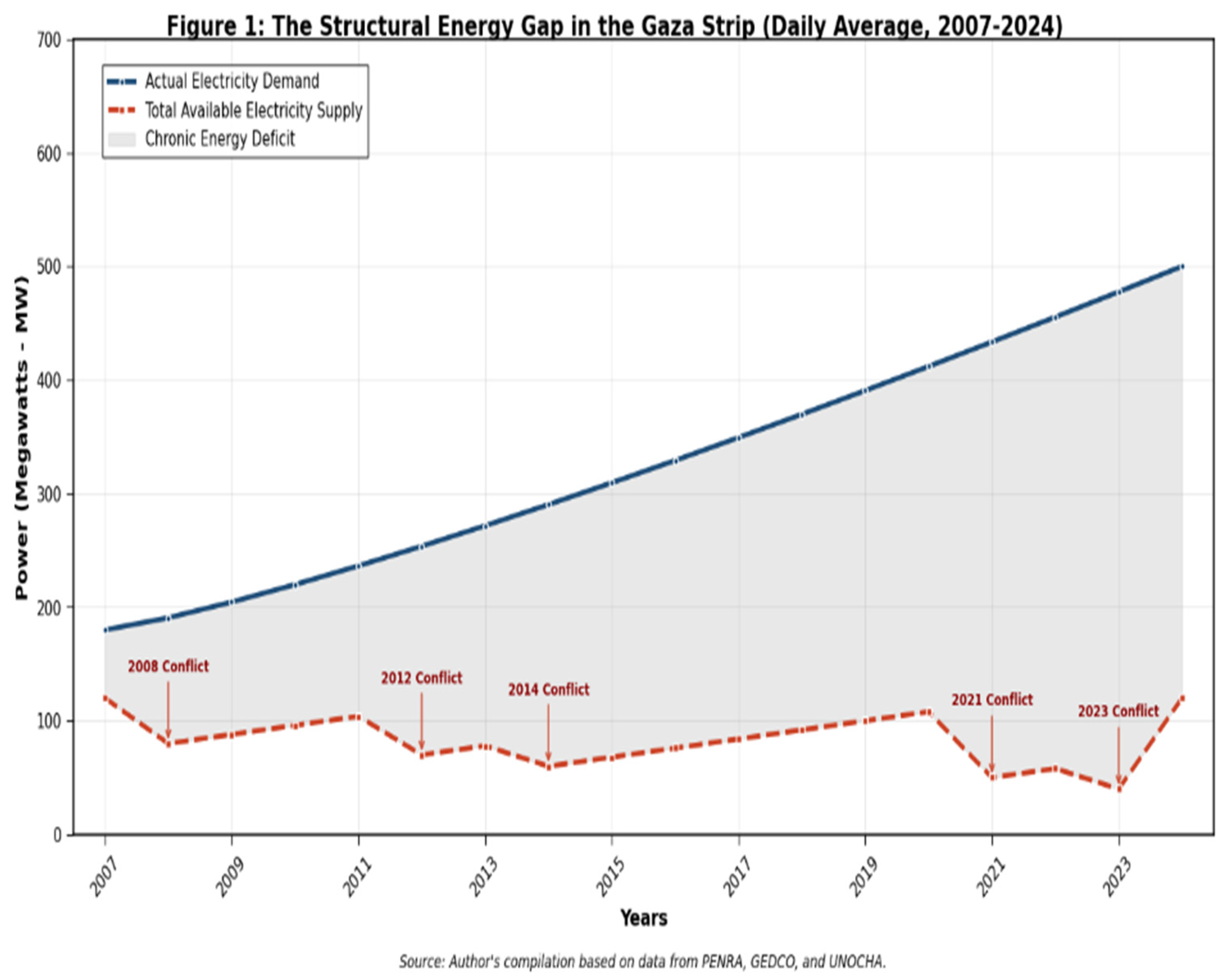

- Daily electricity supply versus estimated demand (typically around 120-180 MW supplied against a peak demand exceeding 500-600 MW).

- ◦

- Technical specifications of damage after each conflict, such as the number of destroyed transformers, damaged feeder lines (e.g., the nine cross-border lines from Israel), and kilometers of cabling requiring replacement.

- ◦

- Operational data on the Gaza Power Plant's output, fuel consumption, and recurring shutdowns.

- ◦

- Customer data, including billing rates, revenue collection challenges, and statistics on electricity theft or informal connections.

-

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA): OCHA's regular Situation Reports and thematic deep-dives on Gaza's infrastructure are invaluable for understanding the humanitarian impact. This data includes:

- ◦

- Daily average electricity availability per household, often tracked by governorate, providing a clear picture of the lived reality of blackouts (e.g., "4-6 hours on, 12 hours off").

- ◦

- Impact assessments on essential services, detailing the operational capacity of hospitals, water wells, and wastewater treatment plants, which are heavily reliant on UN-provided emergency fuel.

-

The World Bank and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP): These organizations provide macro-level economic and developmental perspectives. Their reports are key sources for:

- ◦

- Formal Damage and Needs Assessments (DNAs) conducted post-conflict, which quantify the economic cost of infrastructure destruction and the capital required for reconstruction. A 2021 Rapid DNA, for instance, estimated tens of millions of dollars in damages to the energy sector alone.

- ◦

- Feasibility studies and project evaluations for interventions, such as the UNDP's projects to install solar power systems on the rooftops of hospitals and schools, providing data on the cost-benefit and resilience impact of such initiatives.

-

Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS): PCBS household surveys offer socio-economic data that helps contextualize the crisis, providing statistics on:

- ◦

- Household expenditure on energy, allowing for analysis of the "double-billing" phenomenon where families pay for both the public grid and expensive private generator subscriptions.

- ◦

- Prevalence of alternative energy sources, such as the percentage of households owning small generators or having installed solar panels.

3.3.2. Reflexive Practitioner Expertise

3.4. Analytical Framework

3.4.1. Operationalizing the Resilience Lens:

- Vulnerability: Data from GEDCO and UNOCHA on network topology (e.g., over-reliance on a few central feeder lines) and the impact of the blockade on spare parts will be used to map the system's inherent vulnerabilities.

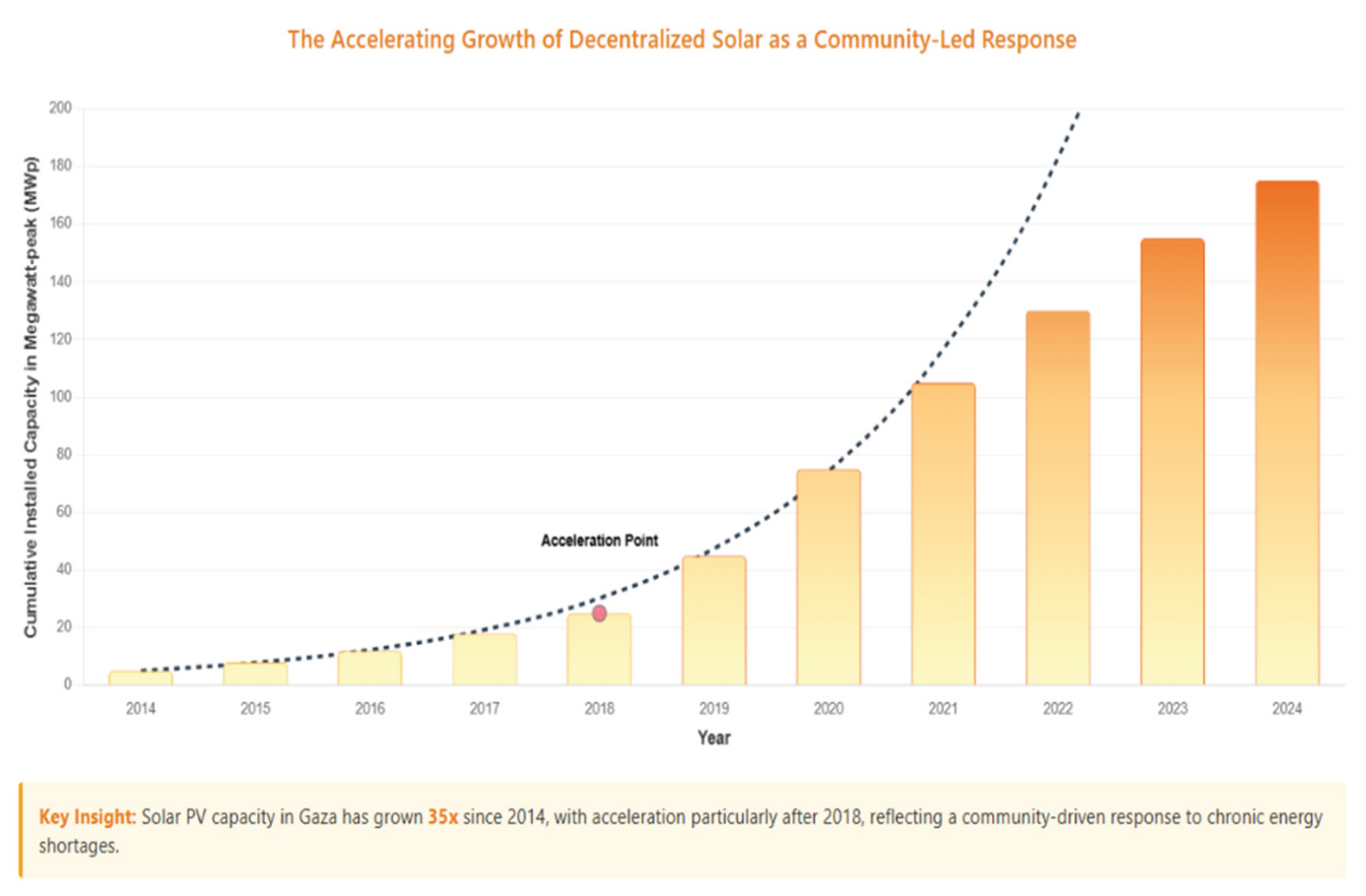

- Adaptive Capacity: Data on the proliferation of rooftop solar panels (from UNDP reports and PCBS surveys) and the emergence of informal generator networks will be analyzed as evidence of bottom-up, community-level adaptation to chronic system failure.

- Transformative Capacity: The analysis will assess the potential for existing innovations (e.g., pilot microgrid projects) to serve as catalysts for a fundamental transformation of the energy system from a centralized, fragile model to a decentralized, resilient one.

3.4.2. Operationalizing the Energy Justice Lens:

- Distributive Justice: GEDCO's electricity distribution schedules and OCHA's data on power availability by region will be critically examined to identify and quantify spatial inequities between urban centers, rural areas, and refugee camps. Household expenditure data from PCBS will be used to analyze how the economic burden of the crisis is distributed.

- Procedural Justice: Donor reports and PENRA policy documents will be scrutinized for evidence of community consultation and participation in the planning of reconstruction projects. The framework will be used to assess whose voices are heard and prioritized in decision-making forums.

- Recognition Justice: The analysis will focus on how the specific energy needs of the most vulnerable groups (e.g., hospital patients reliant on life-support machines, families with low-incomes, female-headed households) are recognized—or ignored—in official energy policy and humanitarian response plans.

4. Findings

4.1. Dissecting the Systemic Collapse: Quantifying Infrastructure Damage

- Main Feeder Lines: Three of the nine main feeder lines from Israel were directly damaged, leading to an immediate loss of a significant portion of imported electricity.

- Internal Distribution Network: Over 70 kilometers of medium and low-voltage cables and 450 distribution transformers were destroyed, in addition to thousands of poles and household connections.

- Cumulative Impact: More significant is the cumulative effect. Equipment that is temporarily repaired using second-hand or "cannibalized" parts from other destroyed sites lacks efficiency and reliability. This elevates technical losses in the grid to over 35% in some areas, compared to the global standard of 8-10%.

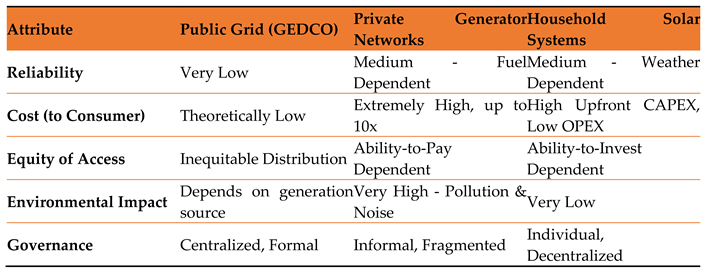

4.2. The Emergent Energy Ecosystem: A Multi-Level Analysis of Emergency Responses

-

Level 1: Household and Community Response (Bottom-up Adaptation):

- ◦

- Private Generator Networks: The "ampere subscription" model has become the primary source of electricity for a majority of the population during grid outages. Data from PCBS surveys reveals that households in Gaza spend up to 25% of their monthly income on energy, a significant portion of which goes to these subscriptions. The cost per kilowatt-hour from these generators ranges from 3 to 4 Israeli Shekels (ILS), which is 7 to 10 times the cost of official grid electricity (approx. 0.4 ILS). This response, while demonstrating adaptive capacity, has entrenched a massive distributive injustice.

- ◦

- The Silent Solar Revolution: The last decade has witnessed a massive boom in the installation of small-scale rooftop photovoltaic (PV) systems (typically 1-3 kW). UNDP estimates suggest there is now over 150 MW of decentralized solar capacity installed, effectively creating a "virtual power plant" larger than the official Gaza Power Plant.

-

Level 2: International Organization Response (Top-down Support):

- ◦

- International organizations have played the role of a "safety valve," preventing the complete collapse of critical services. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) have strategically installed solar power systems on 35 hospitals and primary healthcare centers, as well as over 100 water and wastewater pumping stations.

- ◦

- UNOCHA coordinates the distribution of internationally funded emergency fuel to run the backup generators for these critical facilities when solar power is insufficient, ensuring a minimum continuity of services.

4.3. Compounding Barriers: A Multi-Dimensional Analysis of Reconstruction Challenges

- Political and Logistical Challenges (The Blockade): The Israeli blockade is the primary impediment. Critical equipment such as large transformers, insulated cables, and SCADA control systems are classified as "dual-use" items. Their importation is subject to a complex and lengthy security approval process that can take months or years, if approval is granted at all. This causes catastrophic project delays and forces engineers to resort to "cannibalization"—dismantling parts from some damaged equipment to repair other equipment.

- Economic Challenges (The Vicious Cycle): The electricity sector is trapped in a financial "death spiral." Low supply leads to consumer dissatisfaction and an unwillingness to pay, resulting in GEDCO's revenue collection rates falling below 40%. This financial deficit prevents the company from investing in maintenance and upgrades, which further degrades the grid and reduces supply, and the cycle continues. Compounding this is the "double-billing" phenomenon that drains the purchasing power of the population.

- Technical Challenges (Accumulated Degradation): As a result of the blockade and economic challenges, the grid suffers from chronic ailments. It operates without modern protection and control systems, relies on dangerous manual interventions, and suffers from voltage and frequency instability, which damages consumer appliances and further erodes public trust.

- Social Challenges (Spatial Energy Injustice): An analysis of distribution schedules reveals clear spatial injustice. Urban areas housing institutions and commercial enterprises often receive relatively more hours of electricity, while rural, agricultural areas and marginalized refugee camps are left to endure longer blackouts. This deepens existing developmental gaps and fuels a sense of grievance.

4.4. Seeds of Transformation: Pockets of Innovation and Resilience

- Decentralization as a De Facto Reality: The massive, albeit chaotic, proliferation of rooftop solar has, in effect, created a structural shift. It has cultivated a new generation of "prosumers" (producers and consumers of energy), breaking the monopoly of the state and external suppliers on electricity generation. This represents a transformation from a fully centralized model to a hybrid one, which is the foundation of resilience in modern infrastructure systems.

- Pioneering Microgrid Models: The projects implemented by international organizations to supply hospitals with solar power and battery storage systems serve as prototypes for integrated microgrids. These facilities have become "islands of resilience," capable of operating completely independently from the public grid for extended hours, guaranteeing the continuity of critical services even during a total blackout. These models provide a "proof of concept" for the feasibility of expanding this approach to encompass residential neighborhoods or small industrial zones.

5. Discussion

5.1. Situating Gaza in Global Context: From Uniqueness to Universal Lessons

- Comparison with Puerto Rico (Hurricane Maria, 2017): The collapse of Puerto Rico's aging, centralized power grid post-hurricane led to months of darkness, exposing the latent vulnerabilities of the centralized energy model. As in Gaza, the most effective response emerged from the grassroots: a surge in rooftop solar installations and community microgrids that became lifelines. The similarity lies in demonstrating that decentralization is an innate response to the failure of centralization. The distinction, however, is crucial: whereas the shock in Puerto Rico was acute and singular (a natural disaster), the shock in Gaza is chronic and continuous (a man-made disaster). This makes Gaza’s lessons more urgent, as they teach not how to recover from a single shock, but how to survive under a permanent one.

- Comparison with Japan (Fukushima Disaster, 2011): The nuclear catastrophe led to a deep-seated loss of trust in the state-controlled, centralized energy system. The result was a massive political and investment shift towards renewable and decentralized energy sources. What Japan shares with Gaza is that a crisis triggered a reimagining of the socio-political "imaginary" of energy, away from a reliance on massive, centralized structures. However, while Japan's transformation was driven by government policy and investment, Gaza's is driven by necessity and community innovation in the absence of effective state action.

5.2. Re-Theorizing Resilience: From Shock Response to Co-Existence with Chronic Fragility

- Passive Adaptation: Reliance on diesel generators is an adaptation that solves an immediate problem but creates long-term ones (prohibitive economic cost, pollution, noise) and keeps the population in a state of dependency.

- Transformative Adaptation: The adoption of solar power, especially when organized into community microgrids, represents a transformative leap. It does not just solve the problem of outages but also builds local productive assets, enhances technical skills, and creates a degree of energy sovereignty.

5.3. The Centrality of Justice: Energy as a Site of Inequity and Empowerment

- Distributive Injustice: Manifests starkly in two phenomena: the "double billing" that imposes a disproportionate economic burden on poor households, and the "spatial injustice" in the distribution of scarce electricity hours, which exacerbates the economic marginalization of rural areas and refugee camps.

- Procedural Injustice: The process of reconstruction and energy planning is characterized by an almost complete absence of community participation. Decisions are made by international donors and political and technical elites, leading to solutions that may not meet the real needs of the population or foster a sense of ownership.

- Recognition Injustice: The needs of the most vulnerable groups are often ignored. The focus on restoring "megawatts" to the grid can overlook the vital need of a small clinic in a refugee camp for a few reliable, continuous kilowatts to run a medicine refrigerator.

5.4. Broader Implications: Forging a New Blueprint for Post-Conflict Energy Reconstruction

- Move Beyond the "In-Kind Replacement" Model: Reconstruction efforts must cease to focus exclusively on repairing or replacing destroyed centralized infrastructure with the same specifications. The guiding principle should be to "Build Forward Differently," prioritizing investments in hybrid systems that combine an improved central grid with decentralized, resilient microgrids.

- Integrate Justice into the Core of Resilience Design: Justice should not be an afterthought but a foundational component of project design. This requires developing practical tools, such as the proposed "Energy Equity Index (EEEI)," to evaluate projects based on how well they serve marginalized groups and ensure the fair distribution of benefits.

- Invest in Local Agency: Gaza has proven that communities are not passive victims but active innovators. The role of international aid must shift from being a "provider of solutions" to an "enabler of local capacity." This means funding local energy cooperatives, supporting the training of local technicians, and facilitating access to technology rather than imposing turnkey solutions.

6. Conclusion & Policy Recommendations

6.1. Conclusion

6.2. Policy Recommendations

- 1.

-

A Strategic Shift from Repair to Hybrid Investment:Donors and policymakers must redirect a significant portion of reconstruction funding away from short-term fixes for the central grid and towards a hybrid investment strategy. This strategy should support the development of solar-powered microgrids with storage systems, beginning with critical facilities (hospitals, water plants, schools) and gradually expanding to encompass residential and productive clusters. This approach not only enhances resilience by reducing central points of failure but also contributes to a degree of local energy sovereignty.

- 2.

-

Institutionalizing Energy Justice as an Investment Criterion:To ensure that new investments do not deepen existing inequities, we propose the development and adoption of a "Palestinian Energy Equity Index (PEEEI)." This index should become a mandatory tool for evaluating all proposed energy projects. Projects must be assessed not only on their technical and economic feasibility but also on their contribution to serving the most vulnerable groups, alleviating the energy cost burden on poor households, and providing clear mechanisms for community participation in their design and operation.

- 3.

-

Empowering the Local Renewable Energy Ecosystem:The true innovation in Gaza comes from the grassroots. Interventions must therefore focus on empowering this base rather than bypassing it. This requires concrete actions such as: (a) providing concessional loans and crowdfunding mechanisms for households and small businesses to install high-quality solar systems; (b) supporting vocational training programs to create a skilled workforce of solar technicians, thereby generating green jobs; and (c) facilitating the establishment of community energy cooperatives that can manage and operate local microgrids.

References

- Abdel-Baqi, A.; Phelan, P.E. Energy justice in protracted conflict: The case of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Energy Research & Social Science 2022, 85, 102409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajbaili, M. Gaza’s endless cycle of destruction and reconstruction. The New Arab. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Alareer, A.; El-Harbawi, M. Feasibility of a 100% renewable energy system for the Gaza Strip by 2030. Sustainable Cities and Society 2021, 73, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albatta, R.A.; Bocheva, G.S. The political economy of de-development in the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Journal of Conflict Transformation and Security 2021, 11, 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.H. Rebuilding post-conflict infrastructure: The challenge of legitimacy and good governance. Journal of International Peacekeeping 2018, 22, 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, A.; Arcos-Vargas, A. Energy poverty and gender: A case study of the Gaza Strip, Palestine. Energy Policy 2020, 139, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atallah, M. Gaza’s infrastructure: On the brink of collapse; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- B'Tselem. (2021). Playing with fire in Gaza: Israel’s policy on the electricity crisis. The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories.

- Berdiev, A.; Pasadilla, G. Infrastructure and institutional quality: A panel data analysis. Economic Systems 2017, 41, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broto, V.C. Energy landscapes and urban trajectories to the post-carbon city. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 524–534. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, M.A.; Sovacool, B.K. Climate change and global energy security: Technology and policy options; MIT Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, M.J.; Stephens, J.C. Political power and renewable energy futures: A critical review. Energy Research & Social Science 2018, 35, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldecott, B.L. Stranded assets and the energy transition; Routledge, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chester, M.V. Resilience reconsidered. Infrastructure Complexity 2020, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Daher, S.; Ruble, B.A. Rebuilding the city: The case of post-war Beirut. Urban Studies 2018, 55, 941–957. [Google Scholar]

- Dalby, S. Anthropocene geopolitics: Globalization, security, sustainability; University of Ottawa Press, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- El-Hallaq, M.A. Analysis of the factors affecting PV system adoption in the Gaza Strip. Renewable Energy Focus 2020, 35, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Global Environmental Change 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Biggs, R.; Norström, A.V.; Reyers, B.; Rockström, J. Social-ecological resilience and biosphere-based sustainability science. Ecology and Society 2016, 21. [Google Scholar]

- Gaza Electricity Distribution Company (GEDCO). (2022). Annual Report 2021. GEDCO Publishing.

- Gisha. (2023). Red Lines, Gray Zones: Israel's dual-use policy and its impact on Gaza's civilian infrastructure. Gisha - Legal Center for Freedom of Movement.

- Healy, N.; Barry, J. Politicizing energy justice and energy sovereignty: Opening up the broader socio-political questions. Energy Policy 2017, 107, 360–369. [Google Scholar]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, M.D.; Jaddivada, A. Toward a resilient and intelligent power system; Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). (2022). Gaza: Two million people, ten hours of electricity a day.

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Research & Social Science 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemun, M.M.; Rignall, K. The politics of microgrids: A critical review of community-centered energy transitions. Energy Research & Social Science 2021, 81, 102271. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari, U. Political imaginations in the post-conflict city. City 2014, 18, 539–545. [Google Scholar]

- Le Billon, P. The political ecology of war: Natural resources and armed conflicts. Political Geography 2001, 20, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linkov, I.; Trump, B.D. The science and practice of resilience; Springer, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Loring, P.A. Toward a theory of resilience in the human-environment sciences. Environmental Science & Policy 2017, 73, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Mancarella, P. MIGRIDS: Concepts, architectures, and technical challenges. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Electronics 2014, 61, 3747–3759. [Google Scholar]

- Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS). (2023). Palestinian household expenditure and consumption survey, 2022. PCBS Publishing.

- Palestinian Energy and Natural Resources Authority (PENRA). (2020). Strategic Plan for Energy Sector in Palestine 2021–2023. PENRA.

- Pelling, M. Adaptation to climate change: From resilience to transformation; Routledge, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Qahman, M.A.; Othman, A.A. Economic analysis of grid-connected photovoltaic systems in the Gaza Strip. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 234, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, S. (2016). The Gaza Strip: The political economy of de-development. Institute for Palestine Studies. (Foundational work).

- Said, A. The politics of infrastructure in the occupied Palestinian territories; The Palestinian Policy Network: Al-Shabaka, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schleifer, P. Orchestrating infrastructure for development: New habits of governance; Cambridge University Press, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Serdeczny, O.; Adams, S. After the storm: The politics and practice of post-disaster reconstruction. Disasters 2020, 44, 675–696. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.; Sovacool, B.K. The contested politics of post-disaster energy transitions: A case study of Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. Global Environmental Change 2022, 74, 102506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Who are the victims of low-carbon transitions? Towards a political ecology of energy justice. Energy, Ecology and Environment 2021, 6, 273–287. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; D'Agostino, A.L. The wicked politics of energy transitions: A case study of Puerto Rico's solar microgrid struggles. Energy Policy 2018, 117, 347–359. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Allen, M.J.B. The socio-technical governance of energy transitions. Tsinghua Science and Technology 2014, 19, 557–573. [Google Scholar]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Burke, M.; Baker, L.; Kotikalapudi, C.K.; Wlokas, H. New frontiers and conceptual frameworks for energy justice. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 677–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.C.; Wilson, E.J.; Peterson, T.R. Smart grids, big data, and the future of energy governance; Routledge, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). (2022). Report on UNCTAD assistance to the Palestinian people: Developments in the economy of the Occupied Palestinian Territory.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2021). Solar power for Gaza's hospitals: A lifeline. UNDP Programme of Assistance to the Palestinian People.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2023). Gaza Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment (RDNA) - Post-May 2023 Escalation.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2023). Humanitarian Needs Overview: Occupied Palestinian Territory.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2024). Hostilities in the Gaza Strip and Israel | Flash Updates. [Regularly updated reports].

- Walker, B.; Salt, D. Resilience thinking: Sustaining ecosystems and people in a changing world; Island Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinthal, E.; Sowers, J. Targeting infrastructure and livelihoods in the West Bank and Gaza. International Affairs 2019, 95, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2018). Securing energy for development in the West Bank and Gaza. World Bank Group.

- World Bank. (2021). Gaza Rapid Damage and Needs Assessment. World Bank Group.

- World Bank. (2023). Unlocking the potential of the Palestinian economy: The role of private investment and infrastructure.

- Yona, L.; Ugursal, V.I. Resilience of power systems: A review of concepts, metrics, and analysis methods. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2021, 145, 111091. [Google Scholar]

- Zio, E. Challenges in the vulnerability and risk analysis of critical infrastructures. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2016, 152, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).