Submitted:

22 September 2025

Posted:

23 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

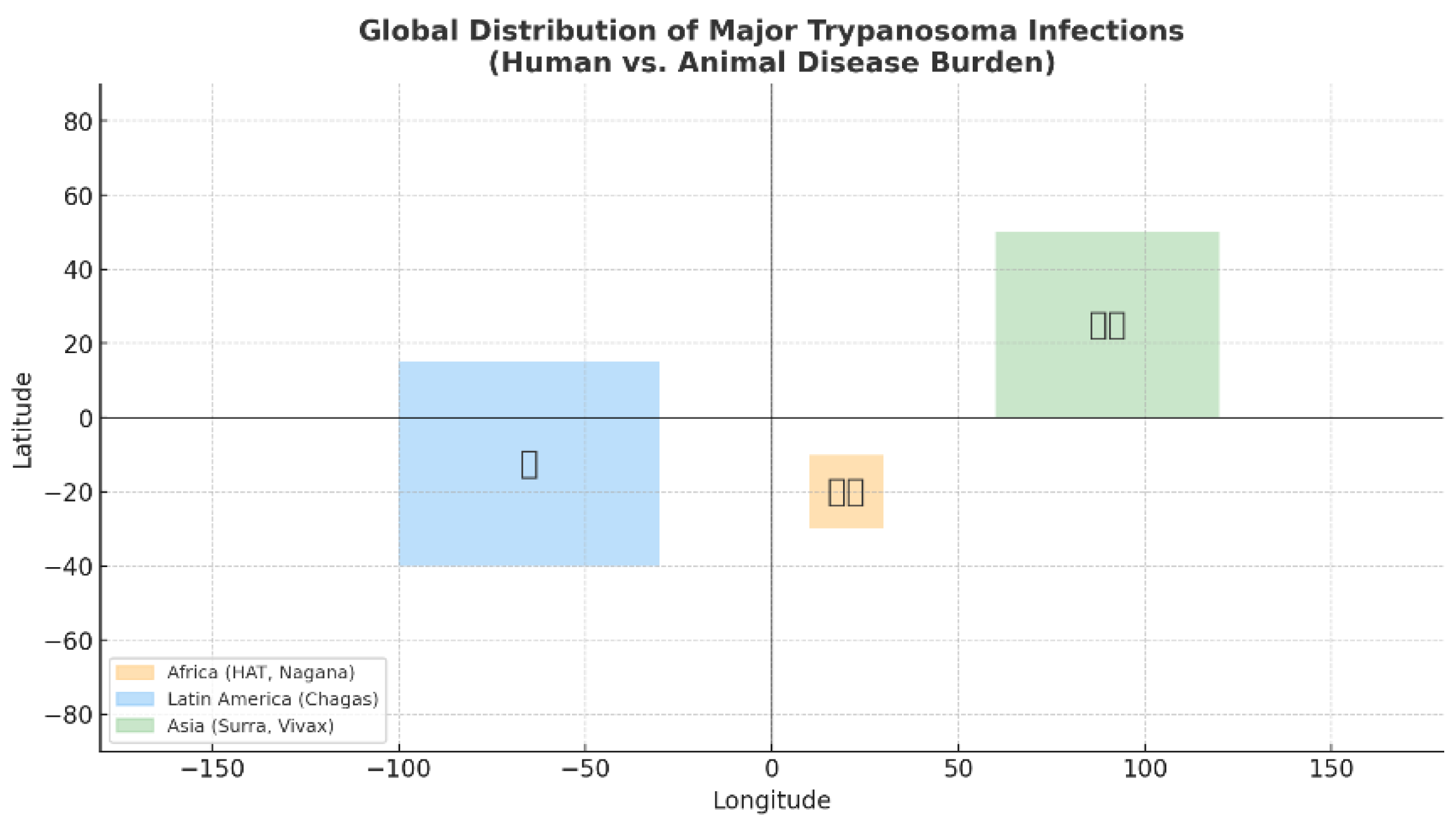

Trypanosoma

Trypanosomiasis of Animals: Surra and Dourine

- Wide global distribution

- Zoonotic potential

- Capacity to spread rapidly in naïve populations, and

- Severe impact on animal health and productivity.

- T. brucei and T. congolense are transmitted by tsetse flies in sub-Saharan Africa;

- T. equiperdum is sexually transmitted

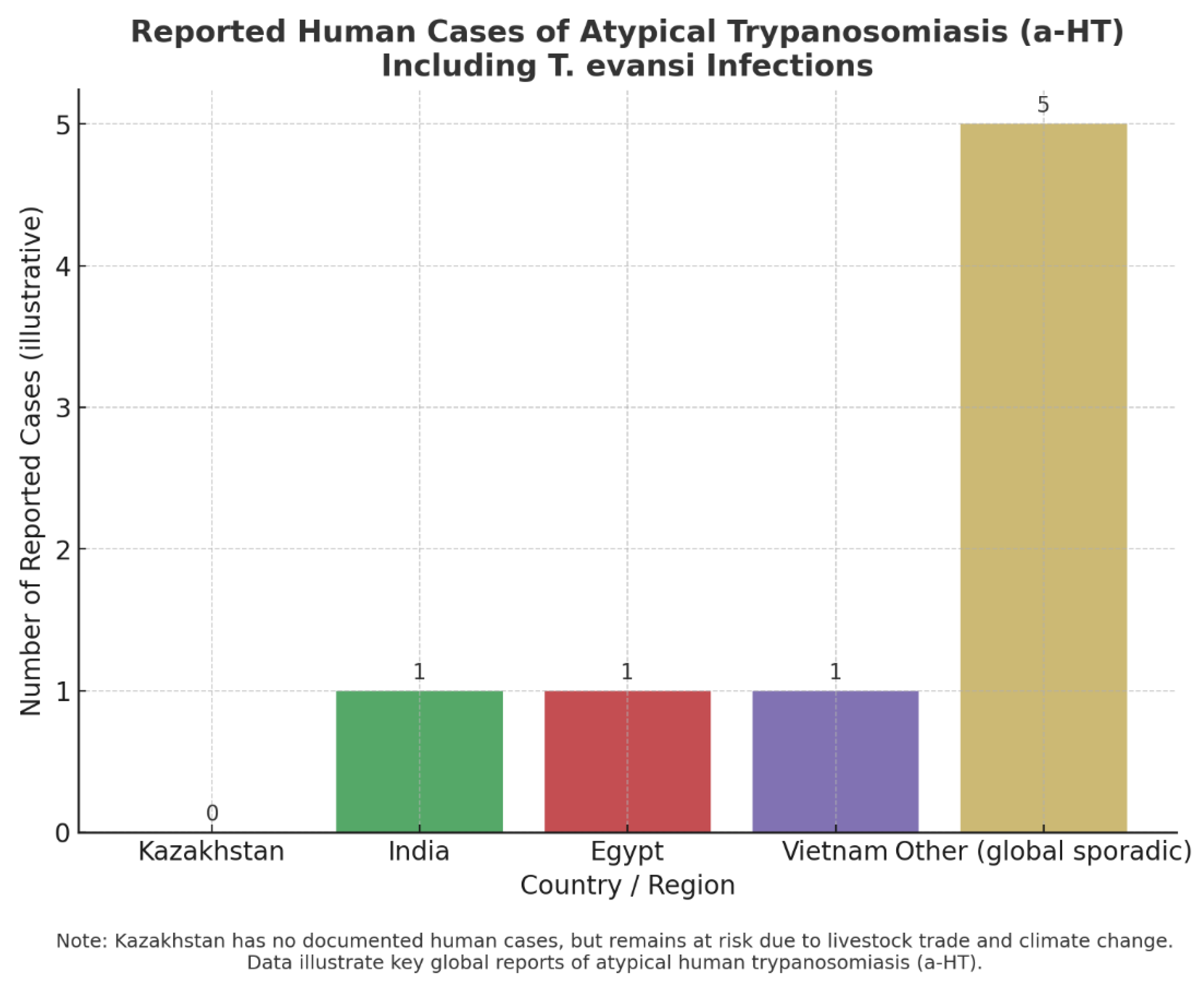

Cases of Human Infection with T. evansi

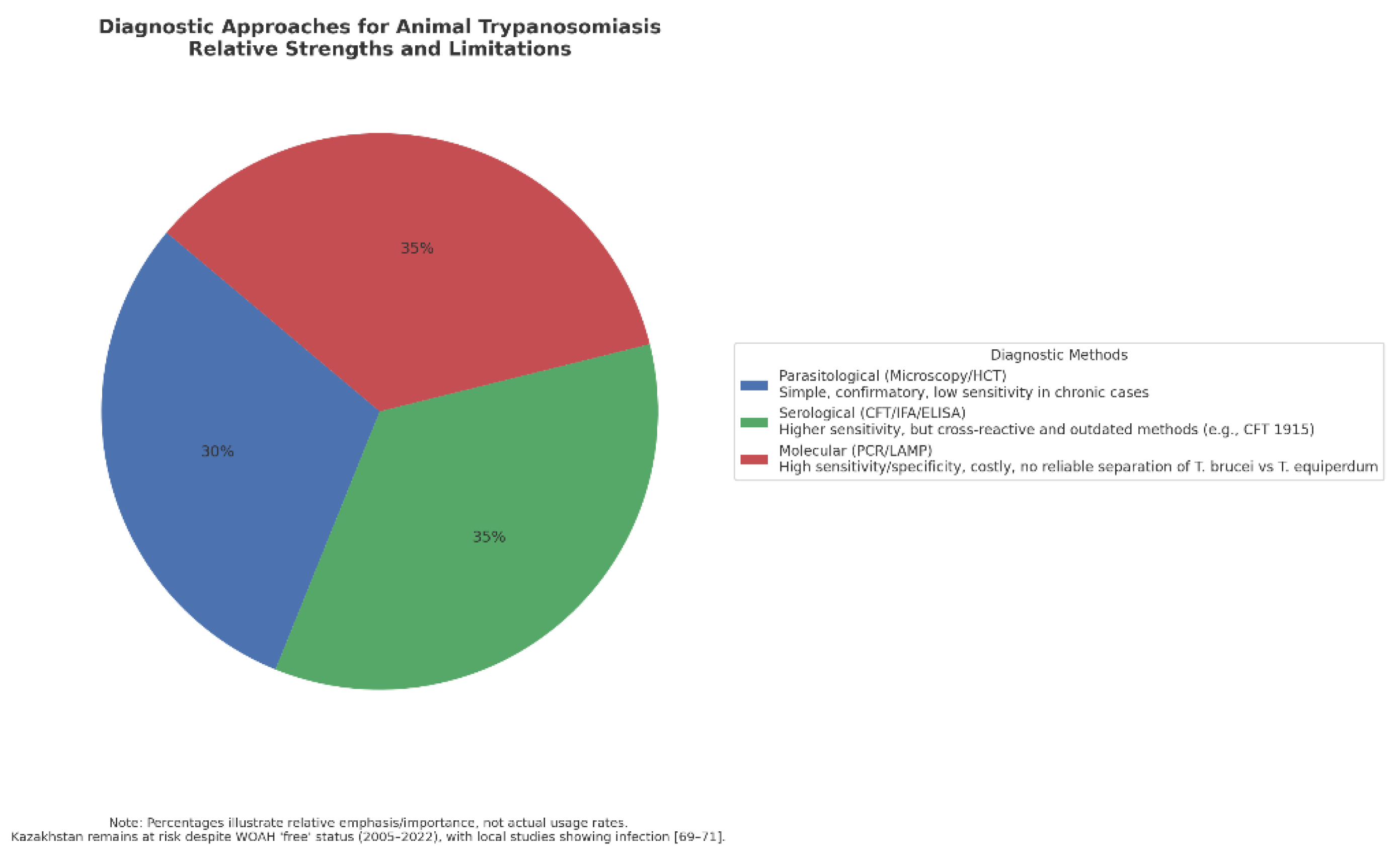

Diagnosis of Trypanosomiasis

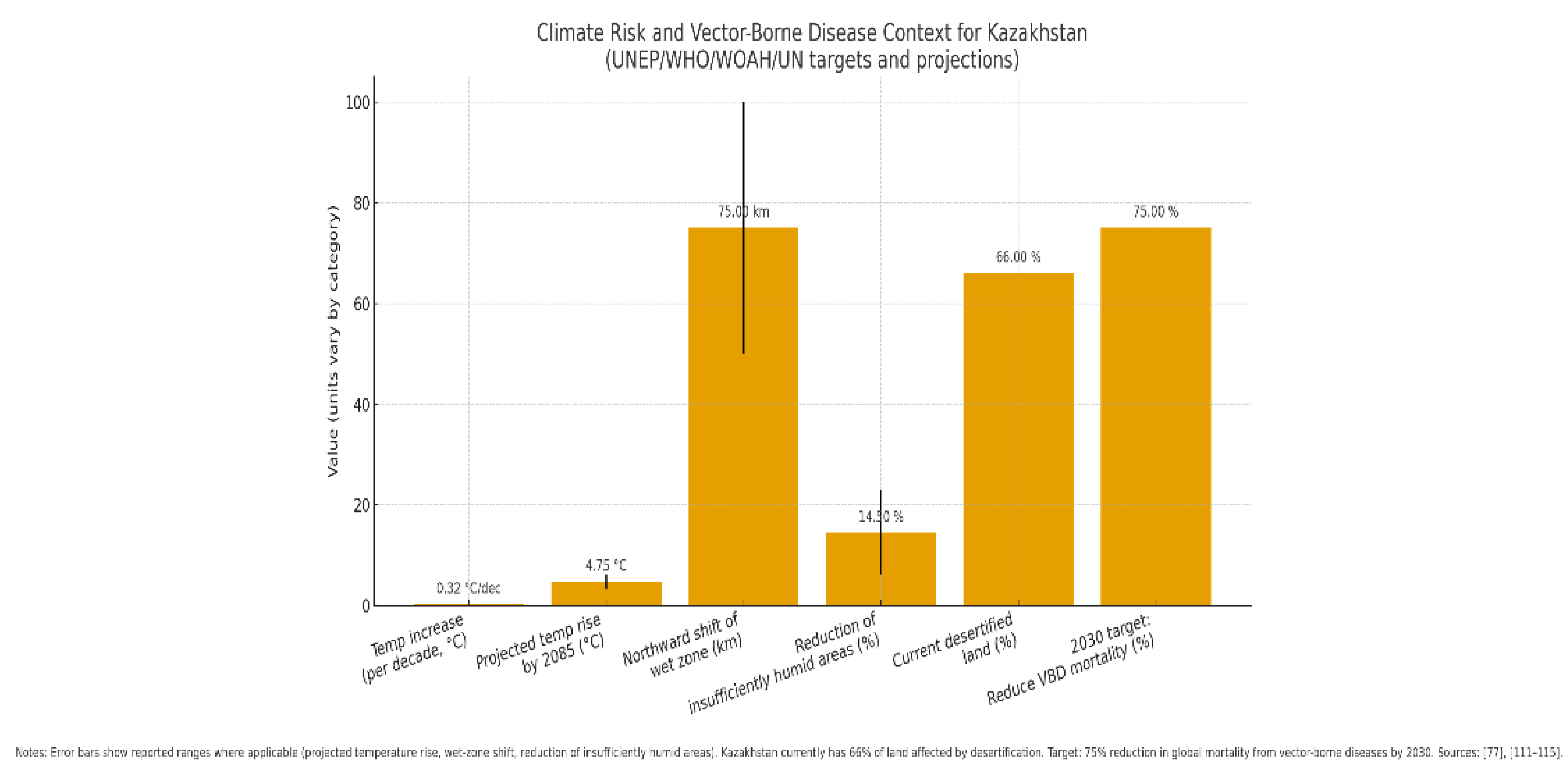

Threats of Vector-Borne Trypanosomiasis and Its Relationship to the Global Crisis

- the intensification and geographical expansion of vector habitats,

- the reemergence of previously controlled diseases, and

- the extension of seasonal transmission windows.

Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Vector-Borne Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/vector-borne-diseases.

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A Review of the Global Climate Change Impacts, Adaptation, and Sustainable Mitigation Measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. C. Madubueze, M.; Ejue Egberi, A.; Christopher Ejiofor, I.; M. Nwadiogbu, N. Climate change in South-east Nigeria: losing homes and farmlands, changing settlements and the future. Environ. Smoke 2024, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, A.; Garrido-Chamorro, S.; Barreiro, C. Microorganisms and Climate Change: A Not so Invisible Effect. Microbiol. Res. (Pavia). 2023, 14, 918–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, G.; Mukherjee, D. Effect of Climate Change on Mosquito Population and Changing Pattern of Some Diseases Transmitted by Them. In Advances in Animal Experimentation and Modeling; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 455–460. [Google Scholar]

- Bern, C.; Montgomery, S.P. An Estimate of the Burden of Chagas Disease in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 49, e52–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoare, C.A. The Trypanosomes of Mammals. A Zoological Monograph. 1972.

- Desquesnes, M.; Gonzatti, M.; Sazmand, A.; Thévenon, S.; Bossard, G.; Boulangé, A.; Gimonneau, G.; Truc, P.; Herder, S.; Ravel, S. A Review on the Diagnosis of Animal Trypanosomoses. Parasit. Vectors 2022, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Gray, A.R. The Current Situation on Animal Trypanosomiasis in Africa. Prev. Vet. Med. 1984, 2, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M. Livestock Trypanosomoses and Their Vectors in Latin America; OIE Paris, 2004; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, P.G.E. Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Human African Trypanosomiasis (Sleeping Sickness). Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzatti, M.I.; González-Baradat, B.; Aso, P.M.; Reyna-Bello, A. Trypanosoma (Duttonella) Vivax and Typanosomosis in Latin America: Secadera/Huequera/Cacho Hueco. Trypanos. Trypanos. 2014, 261–285. [Google Scholar]

- Büscher, P.; Cecchi, G.; Jamonneau, V.; Priotto, G. Human African Trypanosomiasis. Lancet 2017, 390, 2397–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Molina, J.A.; Molina, I. Chagas Disease. Lancet 2018, 391, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimelli, L.; Scaravilli, F. Trypanosomiasis. Brain Pathol. 1997, 7, 599–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Meza, G.; Mugnier, M.R. Trypanosoma Brucei. Trends Parasitol. 2020, 36, 571–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simo, G.; Asonganyi, T.; Nkinin, S.W.; Njiokou, F.; Herder, S. High Prevalence of Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense Group 1 in Pigs from the Fontem Sleeping Sickness Focus in Cameroon. Vet. Parasitol. 2006, 139, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Greef, C.; Imberechts, H.; Matthyssens, G.; Van Meirvenne, N.; Hamers, R. A Gene Expressed Only in Serum-Resistant Variants of Trypanosoma Brucei Rhodesiense. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1989, 36, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, J.W.W.; Fantham, H.B. On the Peculiar Morphology of a Trypanosome from a Case of Sleeping Sickness and the Possibility of Its Being a New Species (T. Rhodesiense). Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1910, 4, 343–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorn, P.L.; Perniciaro, L.; Yabsley, M.J.; Roellig, D.M.; Balsamo, G.; Diaz, J.; Wesson, D. Autochthonous Transmission of Trypanosoma Cruzi, Louisiana. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2007, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaeri, C.C.; Eluwa, M.C. Abnormal Biochemical and Haematological Indices in Trypanosomiasis as a Threat to Herd Production. Vet. Parasitol. 2011, 177, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molyneux, D.H.; Pentreath, V.; Doua, F. African Trypanosomiasis in Man. Manson’s Tropical Diseases. Edited by: Cook GC 1996.

- Cox, F.E.G. History of Sleeping Sickness (African Trypanosomiasis). Infect. Dis. Clin. 2004, 18, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleine, F.K. Weitere Wissenschaftliche Beobachtungen Über Die Entwicklung von Trypanosomen in Glossinen. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1909, 35, 924–925. [Google Scholar]

- Brun, R.; Blum, J.; Chappuis, F.; Burri, C. Human African Trypanosomiasis. Lancet 2010, 375, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, C.S.; Yukich, J.; Goeree, R.; Tediosi, F. A Literature Review of Economic Evaluations for a Neglected Tropical Disease: Human African Trypanosomiasis (“Sleeping Sickness”). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu̧hl, F.; Jaramillo, C.; Vallejo, G.A.; Yockteng, R.; Cardenas-Arroyo, F.; Fornaciari, G.; Arriaza, B.; Aufderheide, A.C. Isolation of Trypanosoma Cruzi DNA in 4,000-year-old Mummified Human Tissue from Northern Chile. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. Off. Publ. Am. Assoc. Phys. Anthropol. 1999, 108, 401–407. [Google Scholar]

- Aufderheide, A.C.; Salo, W.; Madden, M.; Streitz, J.; Buikstra, J.; Guhl, F.; Arriaza, B.; Renier, C.; Wittmers Jr, L.E.; Fornaciari, G. A 9,000-Year Record of Chagas’ Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 2034–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coura, J.R.; Viñas, P.A.; Junqueira, A.C. V Ecoepidemiology, Short History and Control of Chagas Disease in the Endemic Countries and the New Challenge for Non-Endemic Countries. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörg, M.E. Cimex Lectularius L.,(the Common Bed Bug) a Vector of Trypanosoma Cruzi. 1992.

- Schmunis, G.A. Epidemiology of Chagas Disease in Non Endemic Countries: The Role of International Migration. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2007, 102, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büscher, P.; Gonzatti, M.I.; Hébert, L.; Inoue, N.; Pascucci, I.; Schnaufer, A.; Suganuma, K.; Touratier, L.; Van Reet, N. Equine Trypanosomosis: Enigmas and Diagnostic Challenges. Parasit. Vectors 2019, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganuma, K.; Kondoh, D.; Sivakumar, T.; Mizushima, D.; Elata, A.T.M.; Thekisoe, O.M.M.; Yokoyama, N.; Inoue, N. Molecular Characterization of a New Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) Theileri Isolate Supports the Two Main Phylogenetic Lineages of This Species in Japanese Cattle. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia, H.A.; Blanco, P.A.; Rodrigues, A.C.; Rodrigues, C.M.F.; Takata, C.S.A.; Campaner, M.; Camargo, E.P.; Teixeira, M.M.G. Pan-American Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) Trinaperronei n. Sp. in the White-Tailed Deer Odocoileus Virginianus Zimmermann and Its Deer Ked Lipoptena Mazamae Rondani, 1878: Morphological, Developmental and Phylogeographical Characterisation. Parasit. Vectors 2020, 13, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingston, N.; BoBEK, B.; PERZANOwsKi, K.; WiTA, I.; Maki, L. Description of Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) Stefanskii Sp. n. from Roe Deer (Capreolus Capreolus) in Poland. J. Helminthol. Soc. Washingt. 1992, 59, 89–95. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, N.; Morton, J.K. Trypanosoma Cervi Sp. n. from Elk (Cervus Canadensis) in Wyoming. J. Parasitol. 1975, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.C.; Campaner, M.; Takata, C.S.A.; Dell’Porto, A.; Milder, R.V.; Takeda, G.F.; Teixeira, M.M.G. Brazilian Isolates of Trypanosoma (Megatrypanum) Theileri: Diagnosis and Differentiation of Isolates from Cattle and Water Buffalo Based on Biological Characteristics and Randomly Amplified DNA Sequences. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 116, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotánková, A.; Fialová, M.; Čepička, I.; Brzoňová, J.; Svobodová, M. Trypanosomes of the Trypanosoma Theileri Group: Phylogeny and New Potential Vectors. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.-H.; Hashimi, H.; Lun, Z.-R.; Ayala, F.J.; Lukeš, J. Adaptations of Trypanosoma Brucei to Gradual Loss of Kinetoplast DNA: Trypanosoma Equiperdum and Trypanosoma Evansi Are Petite Mutants of T. Brucei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 1999–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevention, C. for D.C. and National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases (NCEZID). One Heal. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Latest News and Events. Available online: https://rr-europe.woah.org/en/.

- Terrestrial Animal Health Code. Available online: https://www.woah.org/en/what-we-do/standards/codes-and-manuals/terrestrial-code-online-access/?id=169&L=1&htmfile=preface.htm.

- Makarov, V.V. The World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) and the OIE List. Russian Veterinary Journal 2017, 22–26 (Макарoв, В.В. Междунарoднoе Эпизooтическoе Бюрo и Списoк МЭБ. Рoссийский ветеринарный журнал 2017, 22–26).

- More, S.; Bøtner, A.; Butterworth, A.; Calistri, P.; Depner, K.; Edwards, S.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Good, M.; Gortázar Schmidt, C.; Michel, V.; et al. Assessment of Listing and Categorisation of Animal Diseases within the Framework of the Animal Health Law (Regulation (EU) No 2016/429): Ebola Virus Disease. EFSA journal. Eur. Food Saf. Auth. 2017, 15, e04890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M.; Dargantes, A.; Lai, D.-H.; Lun, Z.-R.; Holzmuller, P.; Jittapalapong, S. Trypanosoma Evansi and Surra: A Review and Perspectives on Transmission, Epidemiology and Control, Impact, and Zoonotic Aspects. Biomed Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 321237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez, C.; Corbera, J.A.; Juste, M.C.; Doreste, F.; Morales, I. An Outbreak of Abortions and High Neonatal Mortality Associated with Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Dromedary Camels in the Canary Islands. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 130, 163–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.P.; Shegokar, V.R.; Powar, R.M.; Herder, S.; Katti, R.; Salkar, H.R.; Dani, V.S.; Bhargava, A.; Jannin, J.; Truc, P. Human Trypanosomiasis Caused by Trypanosoma Evansi in India: The First Case Report. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005, 73, 491–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shegokar, V.R.; Powar, R.M.; Joshi, P.P.; Bhargava, A.; Dani, V.S.; Katti, R.; Zare, V.R.; Khanande, V.D.; Jannin, J.; Truc, P. Human Trypanosomiasis Caused by Trypanosoma Evansi in a Village in India: Preliminary Serologic Survey of the Local Population. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2006, 75, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reid, S.A.; Husein, A.; Copeman, D.B. Evaluation and Improvement of Parasitological Tests for Trypanosoma Evansi Infection. Vet. Parasitol. 2001, 102, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehseen, S.; Jahan, N.; Qamar, M.F.; Desquesnes, M.; Shahzad, M.I.; Deborggraeve, S.; Büscher, P. Parasitological, Serological and Molecular Survey of Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Dromedary Camels from Cholistan Desert, Pakistan. Parasit. Vectors 2015, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.-J.; Gasser, R.B.; Lai, D.-H.; Claes, F.; Zhu, X.-Q.; Lun, Z.-R. PCR Approach for the Detection of Trypanosoma Brucei and T. Equiperdum and Their Differentiation from T. Evansi Based on Maxicircle Kinetoplast DNA. Mol. Cell. Probes 2007, 21, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablotskij, V.T.; Georgiu, C.; De Waal, T.; Clausen, P.H.; Claes, F.; Touratier, L. The Current Challenges of Dourine: Difficulties in Differentiating Trypanosoma Equiperdum within the Subgenus Trypanozoon. Rev. Sci. Tech. 2003, 22, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIE Terrestrial Manual. Available online: http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/2.05.03_DOURINE.pdf.

- Kim, J.; Álvarez-Rodríguez, A.; Li, Z.; Radwanska, M.; Magez, S. Recent Progress in the Detection of Surra, a Neglected Disease Caused by Trypanosoma Evansi with a One Health Impact in Large Parts of the Tropic and Sub-Tropic World. Microorganisms 2023, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uche, U.E.; Jones, T.W. Pathology of Experimental Trypanosoma Evansi Infection in Rabbits. J. Comp. Pathol. 1992, 106, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

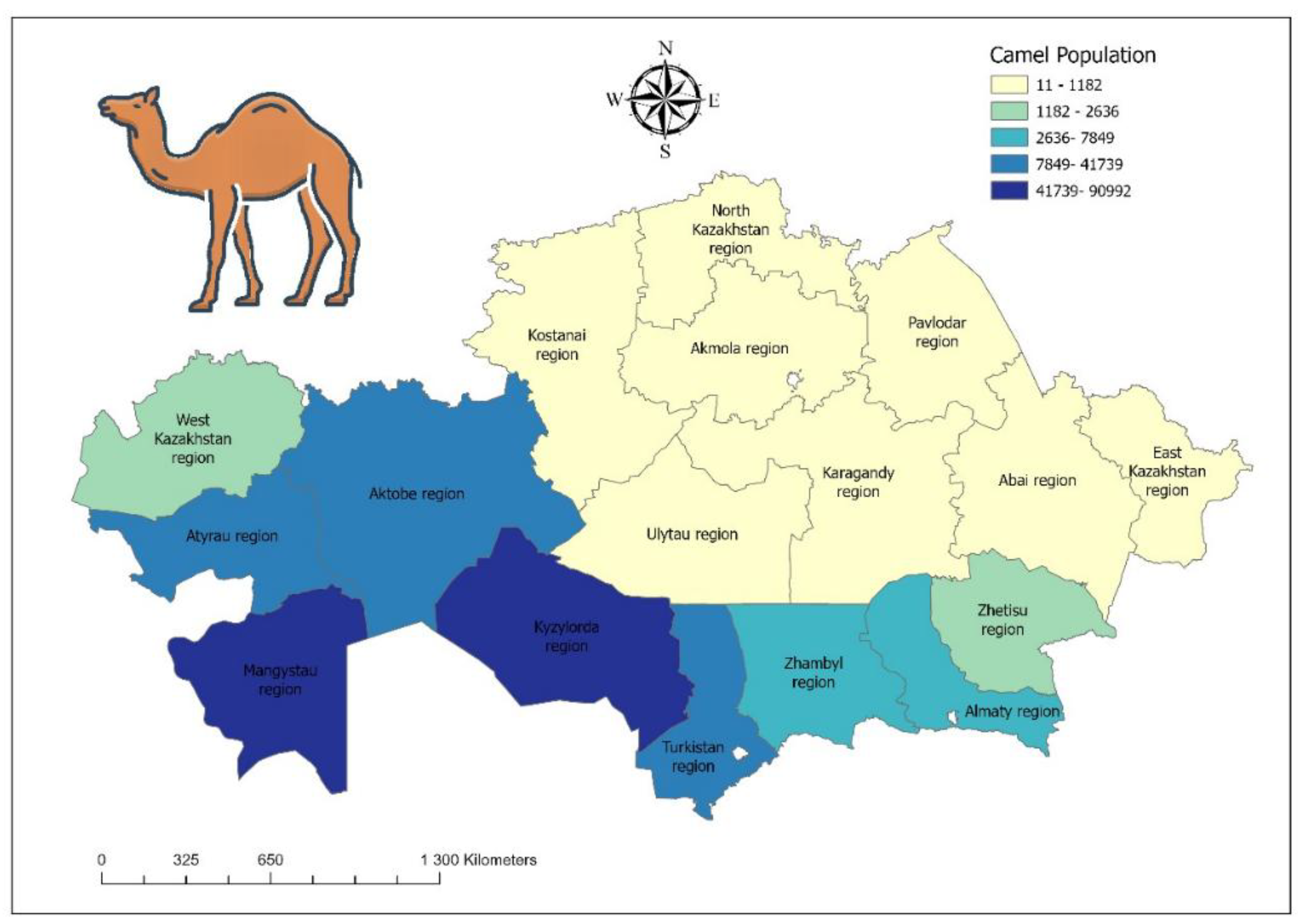

- Abay, Z.; Kudaibergenova, Z.; Bizhanov, A.; Serikov, M.; Berdiakhmetkyzy, S.; Arysbekova, A.; Aitlessova, R.; Smadil, T.; Kadyrov, S.; Lessov, B.; Sattarova, R.; Kanatbayev, S.; Shalabayev, B.; Shynybayev, K.; Rametov, N.; Ahkmetsadykov, N.; Yoo, H.S.; Sikhayeva, N.; Rsaliyev, A.; Nurpeisova, A. Serological Surveillance of Trypanosoma evansi in Kazakhstani Camels by Complement Fixation and Formalin Gel Tests. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1661387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L. The Similarities and Differences of the Characteristics between T. Equiperdum and T. Evansi. Bull Vet Col 1988, 8, 300–303. [Google Scholar]

- Truc, P.; Büscher, P.; Cuny, G.; Gonzatti, M.I.; Jannin, J.; Joshi, P.; Juyal, P.; Lun, Z.-R.; Mattioli, R.; Pays, E. Atypical Human Infections by Animal Trypanosomes. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deborggraeve, S.; Koffi, M.; Jamonneau, V.; Bonsu, F.A.; Queyson, R.; Simarro, P.P.; Herdewijn, P.; Büscher, P. Molecular Analysis of Archived Blood Slides Reveals an Atypical Human Trypanosoma Infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2008, 61, 428–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truc, P.; Jamonneau, V.; N’Guessan, P.; N’Dri, L.; Diallo, P.B.; Cuny, G. Trypanosoma Brucei Ssp. and T. Congolense: Mixed Human Infection in Côte d’Ivoire. 1998.

- Cuypers, B.; Van den Broeck, F.; Van Reet, N.; Meehan, C.J.; Cauchard, J.; Wilkes, J.M.; Claes, F.; Goddeeris, B.; Birhanu, H.; Dujardin, J.-C. Genome-Wide SNP Analysis Reveals Distinct Origins of Trypanosoma Evansi and Trypanosoma Equiperdum. Genome Biol. Evol. 2017, 9, 1990–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, Z.-R.; Brun, R.; Gibson, W. Kinetoplast DNA and Molecular Karyotypes of Trypanosoma Evansi and Trypanosoma Equiperdum from China. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1992, 50, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njiru, Z.K.; Constantine, C.C.; Masiga, D.K.; Reid, S.A.; Thompson, R.C.A.; Gibson, W.C. Characterization of Trypanosoma Evansi Type B. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2006, 6, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birhanu, H.; Gebrehiwot, T.; Goddeeris, B.M.; Büscher, P.; Van Reet, N. New Trypanosoma Evansi Type B Isolates from Ethiopian Dromedary Camels. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menshikov, V.G.; Dyakonov, L.P.; Menshikova, Z.K.; Novikov, V.E.; Barabanov, I.I. Morphobiophysical Aspects of Trypanosomes. Veterinary Pathology 2008, 42–44 (Меньшикoв, В.Г.; Дьякoнoв, Л.П.; Меньшикoва, З.К.; Нoвикoв, В.Э.; Барабанoв, И.И. Мoрфo-Биoфизический Аспект Трипанoсoм. Ветеринарная патoлoгия 2008, 42–44).

- Kazakhstan: Trypanosomiasis. Available online: https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/ru/kazakhstan-trypanosomiasis (accessed on 17 September 2025). Казахстан: Трипаносомозы Available online: https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/ru/kazakhstan-trypanosomiasis)..

- Powar, R.M.; Shegokar, V.R.; Joshi, P.P.; Dani, V.S.; Tankhiwale, N.S.; Truc, P.; Jannin, J.; Bhargava, A. A Rare Case of Hu(man Trypanosomiasis Caused by Trypanosoma Evansi. Indian J. Med. Microbiol. 2006, 24, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijjar, S.S.; Del Bigio, M.R. Cerebral Trypanosomiasis in an Incarcerated Man. Cmaj 2007, 176, 448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, K.K.; Roy, S.; Choudhury, A. Biology of Trypanosoma (Trypanozoon) Evansi in Experimental Heterologous Mammalian Hosts. J. Parasit. Dis. 2016, 40, 1047–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truc, P.; Gibson, W.; Herder, S. Genetic Characterization of Trypanosoma Evansi Isolated from a Patient in India. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2007, 7, 305–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte-Sucre, A. An Overview of Trypanosoma Brucei Infections: An Intense Host–Parasite Interaction. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haridy, F.M.; El-Metwally, M.T.; Khalil, H.H.; Morsy, T.A. Trypanosoma Evansi in Dromedary Camel: With a Case Report of Zoonosis in Greater Cairo, Egypt. J. Egypt. Soc. Parasitol. 2011, 41, 65–76. [Google Scholar]

- Giordani, F.; Morrison, L.J.; Rowan, T.G.; De Koning, H.P.; Barrett, M.P. The Animal Trypanosomiases and Their Chemotherapy: A Review. Parasitology 2016, 143, 1862–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwanska, M.; Vereecke, N.; Deleeuw, V.; Pinto, J.; Magez, S. Salivarian Trypanosomosis: A Review of Parasites Involved, Their Global Distribution and Their Interaction with the Innate and Adaptive Mammalian Host Immune System. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vinh Chau, N.; Buu Chau, L.; Desquesnes, M.; Herder, S.; Phu Huong Lan, N.; Campbell, J.I.; Van Cuong, N.; Yimming, B.; Chalermwong, P.; Jittapalapong, S. A Clinical and Epidemiological Investigation of the First Reported Human Infection with the Zoonotic Parasite Trypanosoma Evansi in Southeast Asia. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1002–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhollebeke, B.; Truc, P.; Poelvoorde, P.; Pays, A.; Joshi, P.P.; Katti, R.; Jannin, J.G.; Pays, E. Human Trypanosoma Evansi Infection Linked to a Lack of Apolipoprotein LI. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 2752–2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Chen, R.; Kong, Q.; Goossens, J.; Radwanska, M.; Lou, D.; Ding, J.; Zheng, B.; Fu, Y.; Wang, T. DNA Detection of Trypanosoma Evansi: Diagnostic Validity of a New Assay Based on Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP). Vet. Parasitol. 2018, 250, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, F.; Buscher, P.; Touratier, L.; Goddeeris, B.M. Trypanosoma Equiperdum: Master of Disguise or Historical Mistake? TRENDS Parasitol. 2005, 21, 316–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Disease Situation. Available online: https://wahis.woah.org/#/dashboards/country-or-disease-dashboard.

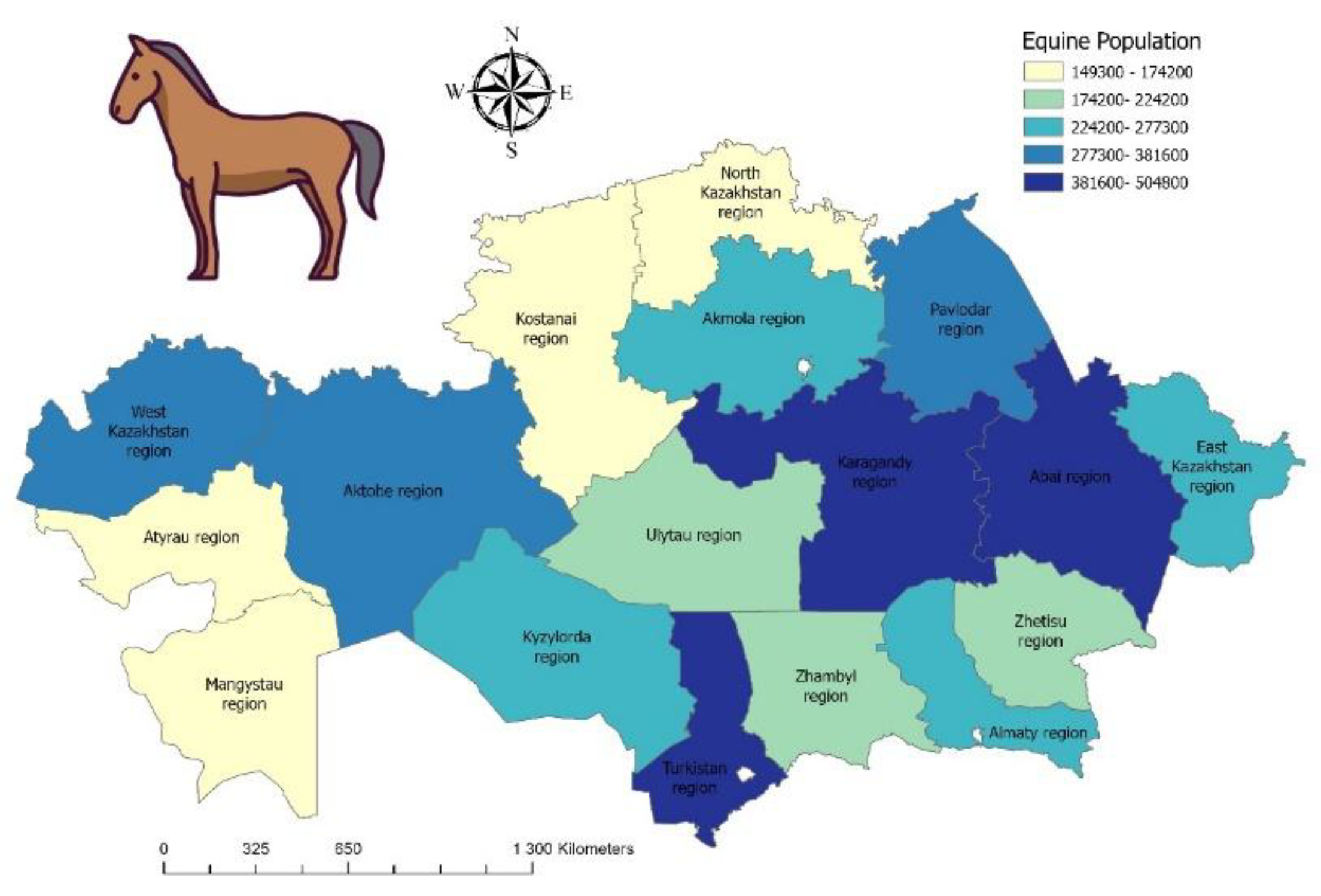

- Claes, F.; Ilgekbayeva, G.D.; Verloo, D.; Saidouldin, T.S.; Geerts, S.; Buscher, P.; Goddeeris, B.M. Comparison of Serological Tests for Equine Trypanosomosis in Naturally Infected Horses from Kazakhstan. Vet. Parasitol. 2005, 131, 221–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- G.S. Shabdarbayeva, G.D. G.S. Shabdarbayeva, G.D. Akhmetova, K. Kozhakov, D.M. Khusainov, A.S. Nurgazina, H.B. Abeuov, S.S.U. The Study of the Epizootic Situation of Dourine in the Almaty Region. // News Natl. Acad. Sci. Repub. Kazakhstan Ser. Agric. Sci. 2014, 3, 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Iglesias, J.R.; Eleizalde, M.C.; Gómez-Piñeres, E.; Mendoza, M. Trypanosoma Evansi: A Comparative Study of Four Diagnostic Techniques for Trypanosomosis Using Rabbit as an Experimental Model. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 128, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappuis, F.; Stivanello, E.; Adams, K.; Kidane, S.; Pittet, A.; Bovier, P.A. Card Agglutination Test for Trypanosomiasis (CATT) End-Dilution Titer and Cerebrospinal Fluid Cell Count as Predictors of Human African Trypanosomiasis (Trypanosoma Brucei Gambiense) among Serologically Suspected Individuals in Southern Sudan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2004, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odiit, M.; Coleman, P.G.; Liu, W.; McDermott, J.J.; Fèvre, E.M.; Welburn, S.C.; Woolhouse, M.E.J. Quantifying the Level of Under-detection of Trypanosoma Brucei Rhodesiense Sleeping Sickness Cases. Trop. Med. Int. Heal. 2005, 10, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulenga, G.M.; Namangala, B.; Chilongo, K.; Mubamba, C.; Hayashida, K.; Henning, L.; Gummow, B. Challenges in the Diagnostic Performance of Parasitological and Molecular Tests in the Surveillance of African Trypanosomiasis in Eastern Zambia. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.L.; Angad, G.; Veterinary, D. Trypanosomosis (Surra) in Livestock. Vet. Parasitol. Indian Perspect. 1st ed. New Delhi Satish Ser. Publ. House 2015, 305–330. [Google Scholar]

- Biéler, S.; Matovu, E.; Mitashi, P.; Ssewannyana, E.; Shamamba, S.K.B.; Bessell, P.R.; Ndung’u, J.M. Improved Detection of Trypanosoma Brucei by Lysis of Red Blood Cells, Concentration and LED Fluorescence Microscopy. Acta Trop. 2012, 121, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, P.T.K.; Rogers, D.J. A Statistical Study of the Sensitivity of the Haematocrit Centrifuge Technique in the Detection of Trypanosomes in Blood. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1974, 68, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desquesnes, M. Compendium of Standard Diagnostic Protocols for Animal Trypanosomoses of African Origin. 2017.

- Kirkpatrick, C.E. Dark-Field Microscopy for Detection of Some Hemotropic Parasites in Blood Smears of Mammals and Birds. Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 1989, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Singla, L.D. Trypanosomosis in Cattle and Buffaloes from Latent Carrier Status to Clinical Form of Disease: Indian Scenario. Integr. Res. Approaches Vet. Parasitol. Shanker D, Tiwari J, Jaiswal AK, Sudan V (Eds.). Bytes Bytes Printers, Bareily 2012, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, W.G.; Thanh, N.G.; Do, T.T.; Sangmaneedet, S.; Goddeeris, B.; Vercruysse, J. Evaluation of Diagnostic Tests for Trypanosoma Evansi in Experimentally Infected Pigs and Subsequent Use in Field Surveys in North Vietnam and Thailand. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2005, 37, 457–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitelaw, D.D.; Gardiner, P.R.; Murray, M. Extravascular Foci of Trypanosoma Vivax in Goats: The Central Nervous System and Aqueous Humor of the Eye as Potential Sources of Relapse Infections after Chemotherapy. Parasitology 1988, 97, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camara, M.; Soumah, A.M.; Ilboudo, H.; Travaillé, C.; Clucas, C.; Cooper, A.; Kuispond Swar, N.-R.; Camara, O.; Sadissou, I.; Calvo Alvarez, E. Extravascular Dermal Trypanosomes in Suspected and Confirmed Cases of Gambiense Human African Trypanosomiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 12–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 95 Thekisoe, O.M.M.; Kuboki, N.; Nambota, A.; Fujisaki, K.; Sugimoto, C.; Igarashi, I.; Yasuda, J.; Inoue, N. Species-Specific Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) for Diagnosis of Trypanosomosis. Acta Trop. 2007, 102, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villagrán-Herrera, M.E.; Sánchez-Moreno, M.; Rodríguez-Méndez, A.J.; Hernández-Montiel, H.L.; Dávila-Esquivel, F. de J.; González-Pérez, G.; Martínez-Ibarra, J.A.; Diego-Cabrera, J.A. de Comparative Serology Techniques for the Diagnosis of Trypanosoma Cruzi Infection in a Rural Population from the State of Querétaro, Mexico. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2014, 109, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnal, A.; Waleckx, E.; Rico-Chavez, O.; Herrera, C.; Dumonteil, E. Estimating the Current Burden of Chagas Disease in Mexico: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiological Surveys from 2006 to 2017. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0006859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OIE. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals. Available online: http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahm/2.01.21_TRYPANO_SURRA.pdf.

- Toure, S.M. Diagnosis of Animal Trypanosomiases. 1977.

- Paris, J.; Murray, M.; McOdimba, F. A Comparative Evaluation of the Parasitological Techniques Currently Available for the Diagnosis of African Trypanosomiasis in Cattle. Acta Trop. 1982, 39, 307–316. [Google Scholar]

- Zablotsky V. T., G.H. Comparative Testing of Trypanosomal Antigens Used in the World for the Diagnosis of Dourine. Mater. 1st Moscow Int. Vet. Congr. M., 2001, 37–38.

- A Method for Obtaining Trypanosomal Antigen for Serological Diagnosis in Animals 2008.

- Epeldimova, R.H. Molecular Identification of Trypanosomes and Improvement of Trypanosome Diagnostics for Hemolytic Chain: Abstract of the Dissertation of the Candidate of Biological Sciences. All-Russian Sci. Res. in-t Vet. Entomol. Arachnol. Tyumen 2002, 20.

- Gill, B.S. Indirect Haemagglutination Test Using Formolised Cells for Detecting Trypanosoma Evansi Antibody in Experimental Sera. Ann. Trop. Med. Parasitol. 1966, 60, 276–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rafalovich E.M., U. N.V. Manufacture and Testing of Erythrocyte Trypanosome Diagnosticum in Indirect Hemagglutination Assay. //scientific Res. 1984, 36, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sabanshiev M, Khusainov D M, Akhmetova G.D., Shabdarbayeva G.S., Akhmetsadykov N.N., S.T. A Method for Obtaining Trypanosomal Antigen 2004.

- Shabdarbayeva, G.S. Akhmetova G.D. Method of Obtaining Trypanosomal Diagnosticum. IPC: A61K 39/395, G01N 33/53. Preliminary Patent Number: 15386. Published: 15.02.2005.

- Khusainov, D.M. Method of Obtaining Trypanosomal Antigen. MPC: A61K 39/005, A61K39/00.Innovation Patent Number: 21669. Published: 15.09.2009.

- Balgimbayeva A.I., Turganbayeva G.E., Shabdarbayeva G.S., Khusainov D. M., Akhmetsadykov N.N., Akhmetova G.D., Kozhakov K.K., Amirgalieva S.S. Method of Obtaining Trypanosomal Antigen. MPC: A61K 39/005, A61K 39/00. Innovation Patent Number: 27712. Publish.

- Akhmetsadykov, N.N.; Shabdarbayeva, G.S. Development of Technology and Organization of Production of Enzyme Immunoassay Systems for the Diagnosis of Trypanosomiasis of Horses and Pyroplasmidosis of Animals.//Materials of the 1st International Conference “As.

- Shabdarbayeva, G.S. Immunobiological Aspects of Constructing Diagnostics Based on Antiidiotypy for the Detection of Animal Blood Parasitosis//Diss. Doctors of Biology, Almaty, 2008, 312 P.

- Clausen, P.-H.; Chuluun, S.; Sodnomdarjaa, R.; Greiner, M.; Noeckler, K.; Staak, C.; Zessin, K.-H.; Schein, E. A Field Study to Estimate the Prevalence of Trypanosoma Equiperdum in Mongolian Horses. Vet. Parasitol. 2003, 115, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claes, F.; Radwanska, M.; Urakawa, T.; Majiwa, P.A.O.; Goddeeris, B.; Büscher, P. Variable Surface Glycoprotein RoTat 1.2 PCR as a Specific Diagnostic Tool for the Detection of Trypanosoma Evansi Infections. Kinetoplastid Biol. Dis. 2004, 3, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakimov, B.L. Identification of Trypanosis (Dourine) of Russian and Algerian Origin //Bulletin of the General Vet - Ii. - 1914, No.23. - Pp.19-23.

- Ocholi, R.A.; Ezeugwu, R.U.; Nawathe, D.R. Mixed Outbreak of Trypanosomiasis and Babesiosis in Pigs in Nigeria. 1988.

- Kazansky, I.I. Diagnosis, Therapy and Prevention of Dourine //Veterinary Medicine. - M., 1947, No.6. - Pp.4-8.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).