1. Introduction

In recent years, advancements in textile materials have introduced new functional properties to clothing, enhancing their performance for the wearer, particularly in terms of comfort. This encompasses both sensory comfort (touch and feel) and thermophysiological comfort, which involves the body’s thermal regulation and moisture management, in accordance with established comfort standards [

1]. Comfort is generally defined as a state of psychological, physiological, and physical well-being resulting from an optimal interaction between the human body and its environment. In clothing science, comfort encompasses several dimensions, including thermophysiological, psychological, ergonomic, and sensory aspects. Thermophysiological comfort refers to the effective regulation of heat and moisture transfer from the skin to the surrounding environment, ensuring the maintenance of core body temperature within the optimal range of 36.5–37.5 °C [

2]. Therefore, this definition highlights the critical role of textile breathability, particularly parameters such as air and water vapor permeability, in ensuring clothing comfort [

3]. In recent decades, researchers worldwide have focused on developing innovative wearable textile systems to meet human comfort needs more efficiently. The textile comfort has been explored through various strategies, including fibre micro structuring, the use of hydrophilic–hydrophobic fibre combinations, particular fabric constructions, and surface modification, including laminations, coatings, and chemical treatments [

2,

4]. Among various strategies, surface modifications stand out as one of the most straightforward and effective approaches for tailoring textile properties to enhance wearer comfort. These techniques enable precise adjustment of fabric characteristics without compromising the inherent qualities of the textile substrate [

5]. Current commercial applications illustrate the success of such modifications, prominently featuring advanced microfibre polyester fabrics treated with silicone or fluorinated compounds for water repellency [

6]. Innovative microporous coatings and membranes have also revolutionized performance textiles, with notable examples including Gore-Tex®, which utilizes microporous polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membranes, and Aquatex®, based on polyurethane coatings. Additionally, hydrophilic solid coatings and films, such as Sympatex®, derived from modified polyester films, provide alternative mechanisms for moisture management and breathability [

7,

8]. Collectively, these technologies highlight the pivotal role of surface modification in advancing functional textiles geared toward enhanced user comfort and performance.

However, despite their functional advantages, the extensive use of fluorinated polymers, polyurethanes, and silicones in textile surface treatments presents significant environmental challenges [

9,

10]. Fluorinated compounds, including PTFE-based materials, are exceptionally persistent due to the strength of their carbon-fluorine bonds, rendering them resistant to natural degradation processes [

11]. Consequently, these substances accumulate in ecosystems and living organisms, leading to long-term toxicological risks for wildlife and human health, especially due to bioaccumulation and widespread environmental distribution [

12]. Similarly, polyurethanes and silicones, though less chemically stable and durable, are largely non-biodegradable and complicate waste management. Their degradation contributes to microplastic pollution, a growing concern, given that synthetic textile fibres represent a major source of microplastics in aquatic environments. This persistence and environmental impact underscore the urgent need to develop sustainable, eco-friendly alternatives in textile surface engineering, solutions that maintain high performance while minimizing ecological harm [

13,

14]. In this context, polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) emerge as a promising class of biodegradable polymers capable of replacing petroleum-derived materials in textile applications. PHAs are naturally produced thermoplastic polyesters synthesized by bacteria, capable of degrading in diverse environmental conditions without generating persistent pollutants [

15]. Their production avoids the use of volatile organic solvents, making them inherently safer and more sustainable. Importantly, their material properties can be precisely tailored by adjusting the ratio and composition of copolymers, enabling performance customization for specific applications [

16].

PHAs have also demonstrated commercial viability in the packaging industry, where PHA-based coatings are being developed for paperboard and paper substrates to impart essential barrier properties, such as water resistance, oil repellency, and mechanical strength, without compromising compostability [

17,

18]. This broader adoption underscores the material’s versatility and strong alignment with circular economic principles. Additionally, PHAs offer innovative end-of-life options, including conversion into fertilizers or fermentation feedstocks to produce new polymers [

19]. The integration of PHAs into textile surface engineering therefore represents a viable, forward-thinking approach toward high-performance and environmentally responsible materials that deliver both functional benefits and ecological sustainability [

20]. While PHAs have recently been introduced as coatings for yarns and fabrics using conventional methods such as extrusion and doctor blade application [

21], their potential for direct deposition onto textile surfaces via spray coating techniques remains largely underexplored. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to employ a spray coating system to apply an aqueous, chemically modified PHA dispersion onto two distinct fabric substrates, polyester (PES) and cotton (CO).

The spray coating technique enables precise control over both the quantity and uniformity of polymer deposition, ensuring consistent surface coverage while preserving the intrinsic properties of the textile substrates. This method offers several advantages, including scalability, cost-effectiveness, and compatibility with existing industrial textile finishing processes, making it a promising approach for large-scale implementation [

22].

By optimizing parameters such as spray pressure, polymer concentration, and drying/curing conditions, durable and functional PHA coatings were achieved, providing enhanced surface characteristics without compromising the fabric’s breathability or mechanical integrity. This approach highlights a practical pathway to integrate biodegradable polymer coatings into conventional textile manufacturing, advancing the development of sustainable, high-performance materials.

Building on these advances, this study reports the development and application of aqueous, solvent-free PHA dispersions specifically formulated for textile substrates. By incorporating surfactants and dispersants, the coating process achieved uniform and consistent deposition while ensuring polymer stability within the dispersions. The functional properties of the coated textiles were comprehensively evaluated, underscoring the promise of PHA coatings as sustainable alternatives for textile surface engineering. This work marks a pivotal step toward the industrial adoption of biodegradable polymer coatings, addressing urgent environmental challenges without compromising the intrinsic functionality of the materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) (P3HB) with a weight average molecular weight Mw = 250,000 g/mol and a polydispersity index (PDI) = 2.7 was purchased from Biomer (Schwalbach/Germany). Ethylene glycol (≥99 %) and p-toluene sulfonic (≥99 %) acid were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Darmstadt, Germany). The PHB.E.0 powder is a P3HB diol (Mw 24,000 Da, PDI 1.83) characterized by a particle size distribution ranging from ≤45 µm to ≥250 µm. Woven 100% polyester fabrics (PES, 235 g/m²) pretreated for printing and woven 99% cotton, and 1% elastane fabrics (CO, 369 g/m²) were kindly provided by Riopele (V.N. Famalicão, Portugal). A nonionic surfactant, Tween 80 was kindly provided by Croda Iberica SAU (Barcelona, Spain). DISPERBYK-190, a VOC-free and solvent-free wetting and dispersing additive was acquired from BYK (Wesel, Germany).

2.2. Synthesis of P3HB Diol via Alcoholysis

Ten grams of P3HB were dissolved in 100 mL of chloroform under reflux at 80 °C for one hour. Subsequently, a tenfold molar excess of ethylene glycol (relative to P3HB) was added to the solution, along with 0.5 g of p-toluenesulfonic acid as a catalyst. The mixture was refluxed for an additional four hours. After the reaction, the mixture was poured into ethanol to precipitate the product. The precipitated P3HB-diol was washed with ethanol and filtered. The resulting P3HB-diol (PHB.E.0) was then dried under vacuum at 40 °C to constant weight. The weight average molecular weight was determined by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) using an Agilent chromatograph (Waldbronn, Germany), conducted in chloroform, and calibrated with polystyrene standards.

2.3. Coating Aqueous PHB.E.0 Dispersions on Woven Fabrics

Several aqueous dispersions were prepared by dispersing 1-5% w/v PHB.E.0 (particle size ≤ 45 µm to ≤ 250 µm) in distilled water for 30 minutes. The polymer particle size was adjusted firstly by sieving using a 250 µm stainless steel vibratory sieve (Retsch, German), followed by sieving using a 45 µm stainless steel sieve. The pH was then adjusted to neutral using a 5% (w/v) sodium carbonate solution. Following, 0.05-6% w/v Tween 80 and 0.05-6% w/v Disperbyk 190 were added to the PHB.E.0 dispersion and stirred for 1 hour. To achieve an effective dispersion, the solution was sonicated using a Q700 (QSonica, Newtown, CT, United Sates) at 65% amplitude for 1 to 45 minutes. The selected dispersion was applied to 16 × 16 cm samples of polyester and cotton fabrics using an E1850+ Complete Cabinet Standard Model spray system, equipped with a hydraulic nozzle (diameter of 0.28 mm) (AutoJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, Illinois, USA). The spraying process was carried out at a pressure of 0.4 MPa. The distance between the spray gun and the fabric surface was maintained at 40 cm, and the spray flow rate was set to 100%. Each sample was sprayed for a duration of 5 seconds. Following deposition, the coated fabrics were dried at 100 °C for 10 minutes, then thermofixed at 150 °C for 5 minutes. Subsequently, a pressing process was performed at 160 and 180 °C for 15 seconds under a pressure of 5 bar to enhance polymer fixation efficiency.

2.4. Characterization

2.4.1. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Morphological analyses of the uncoated fabrics and those coated with PHB.E.0 dispersions were performed using a ZEISS EVO 10 Scanning Electron Microscope (Oberkochen, Germany) at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV. Before analysing, PHB.E.0-coated fabrics were coated with a thin layer of Au using a BIO-RAD SC502 sputter coater (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Watford, United Kingdom). Images at a magnitude of 500x were used.

2.4.2. Attenuated Total Reflectance - Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

ATR-FTIR spectra were collected in triplicate. A Spectrum One (PerkinElmer, Rodgau, Germany) spectrophotometer with a diamond crystal was used. Each spectrum was obtained in transmittance mode, by accumulation of 45 scans with a resolution of 4 cm-1 in the range of 650 and 4000 cm-1.

2.4.3. Energy-Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS) analysis

Elemental analysis was carried out using an EDAX Inca Energy 350 X-Max50 EDS detector (Oxford Instruments, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK). The analyses were performed under variable pressure conditions to allow examination without applying a conductive coating, which could potentially alter the surface characteristics of the composite resin. For each sample button, 10 images were acquired at randomly selected locations on the top surface using 2000× magnification. The data are presented in a table as mean ± standard deviation, calculated from measurements taken from 10 images per condition.

2.4.4. Thickness and Grammage

The thickness of fabrics, both before and after coating, was measured using a thickness gauge (SCHRÖDER Rainbow, Weinheim, Germany). The fabrics were placed between two plates or sensors, and the thickness was displayed digitally to ensure greater precision. The grammage was determined following ISO 3801: 1977 – Textiles – Determination of Mass per Unit Length or Mass per Unit Area.

2.4.5. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermal degradation behaviour was examined by monitoring weight loss as the temperature increased from 30 °C to 600 °C, at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, under a nitrogen flow rate of 40 mL/min. The measurements were performed using a TGA 4000 instrument (PerkinElmer, Rodgau, Germany) equipped with ceramic pans and operated via Pyris™ software (PerkinElmer). The results were presented as percentage weight loss versus temperature.

2.4.6. Wettability

Water contact angle measurements were conducted in an optical tensiometer Theta Flex (Biolin scientific, Gothenburg, Sweden) connected to a video-based drop shape analyzer OneAttension software (version 1.2), via the sessile drop measuring method, using droplets of 3 μL of H2O. Ten measurements were performed per type of sample. Static angles were registered immediately after the stable drop contacted with the surface.

2.4.7. Water Absorption Test

The water absorption capacities of samples were evaluated according to ISO 20158:2028. Initially, each sample was placed in a moisture analyser (MBT 64M, VWR, Weinheim, Germany) at 35 °C until equilibrium weight was achieved. The difference between the initial and final masses was recorded. To determine the water absorption, each sample was immersed in a beaker containing 400 mL of water. The time each sample remained on the surface before sinking to the bottom of the beaker was recorded, up to a maximum of 180 s. Samples that remained on the surface for more than 180 s were noted as having a sinking time greater than 180 s. Once a sample reached the bottom of the beaker, it was immediately removed, placed in the moisture analyser, and dried at 150 °C. The water absorption capacity was calculated by the difference between the dried and wet masses of the sample. For samples that did not sink and remained on the surface for longer than 180 s, they were carefully submerged to the bottom of the beaker using tweezers. After reaching the bottom, the samples were immediately removed, placed in the moisture analyser, and dried at 150 °C. The water absorption capacity was again determined by the difference between the dried and wet masses.

2.4.8. Permeabilities

Air and water vapor permeability studies were conducted according to standards ISO 9237:1997 and BS 7209:1990, respectively. Air permeability was measured using a Textest FX 3300 (Textest AG, Schwerzenbach, Switzerland) device under an applied air pressure of 100 Pa, a value commonly used for clothing applications. For each fabric, three samples were tested, with measurements taken at nine equidistant points (20 cm² each) distributed transversely across the fabric surface. On the water vapor permeability (WVP) assessment, a water vapour permeability tester (M261, SDL Atlas, Rock Hill, United States) was used. The samples were placed over cylindrical cups containing 46 mL of deionized water (dH₂O) for 16 hours, with the coated side of the fabric-oriented outward, representing the exterior side of the clothing. Water evaporation through the textile substrates was evaluated by weighing the test cups before and after the exposure period. Experiments were conducted at room temperature (20-24 °C) and 65% relative humidity (RH). An open cup covered with a reference substrate served as the control. All measurements were performed in triplicate. The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) and the water vapor permeability index (I) were calculated using the following equations:

where ΔW is the difference in the water weight (g) before and after the 16 h test, A is the inner area of the cup (mm), Δt is the exposure time (h), WVPs is the water vapor permeability of the samples and WVPr is the water vapor permeability of reference.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Process Optimization of PHA Dispersion Preparation and Spray Coating on Textiles

A spray coating approach was adopted as an alternative finishing method using P3HB-diol (PHB.E.0), a chemically modified form of P3HB containing hydroxyl groups. This modification was intended to facilitate the production of water-based dispersions, enabling more environmentally friendly and easily processable formulations.

To ensure consistent and clog-free application, it was first necessary to develop a stable aqueous dispersion of the PHB.E.0 polymer. To overcome the inherent hydrophobicity of PHB.E.0, various formulation parameters were systematically evaluated to ensure effective aqueous dispersion. This included the evaluation of different polymer particle sizes (granulometries), polymer concentrations, the selection of suitable surfactants and dispersants, the optimization of their respective concentrations, and the determination of appropriate stirring and sonication times. Distilled water was chosen as the dispersing medium due to its environmental benefits, aligning with the European Commision sustainability goals. Furthermore, technical limitations of the spray system mandated the use of water, as the equipment is incompatible with solvents that may corrode internal components or have low flash points. The system’s maximum allowable viscosity is restricted to 280 cP, necessitating precise formulation balancing. Accordingly, to develop a formulation that satisfies all these criteria, a series of PHB.E.0 formulations with concentrations ranging from 1% to 5% w/v were systematically evaluated. While all tested concentrations produced stable dispersions, the primary objective was to determine the optimal concentration for the spray system, ensuring smooth, clog-free operation throughout the spraying process. To support this, surfactant and dispersant concentrations were varied between 0.05% and 6% w/v, and sonication times were explored from 1 to 45 minutes. Additionally, polymer particle sizes ranging from ≤ 45 µm to ≤ 250 µm were assessed to further optimize the formulation. Based on these investigations, the aqueous dispersion selected for use in the spray system was formulated with 2% w/v PHB.E.0 (particle size ≤ 60 µm), combined with 6% w/v Tween 80 and 3% w/v Disperbyk 190.

To achieve uniform spray-coated textiles, a comprehensive evaluation of key spray parameters was conducted, including nozzle type, spray flow rate, spray pressure, nozzle-to-substrate distance, and application duration. Although not yet a standard practice in the textile industry, spray coating is considered a valuable technique due to its potential for scalable and efficient deposition of functional coatings over large surface areas through controlled wet processes [

23]. Nozzle selection ultimately favored the hydraulic type, as pneumatic nozzles showed a higher tendency to clog, particularly when spraying hydrophobic polymer dispersions. Among the parameters evaluated, spray pressure was also found to be critical. Excessive spray pressure generates finer droplets, which increases the likelihood of coating solution penetrating the textile substrate. This can alter the fabric’s microstructure and compromise surface functionality, negatively affecting coating uniformity, durability, and the desired performance characteristics [

24]. Therefore, precise optimization of spraying parameters is essential to control coating thickness, homogeneity, and fabric integrity, ensuring that the final product meets stringent functional specifications [

25].

Based on systematic parameter optimization and the rheological characteristics of the polymer dispersion, a spray pressure of 0.4 MPa was identified as optimal. When combined with an optimized nozzle-to-substrate distance, this pressure maximized surface coverage while minimizing material waste and preventing excessive penetration into the fabric. Specifically, a nozzle-to-fabric distance of 40 cm and a spray duration of 5 seconds provided the most effective surface modification, reducing polymer dispersion loss and promoting consistent, uniform coating deposition.

To evaluate the necessity of a hot-pressing step, two different post-treatment temperatures (160 °C and 180 °C) were applied to the PHB.E.0-coated fabrics. A control sample, i.e., coated fabrics without any hot-pressing step, was also included for comparison.

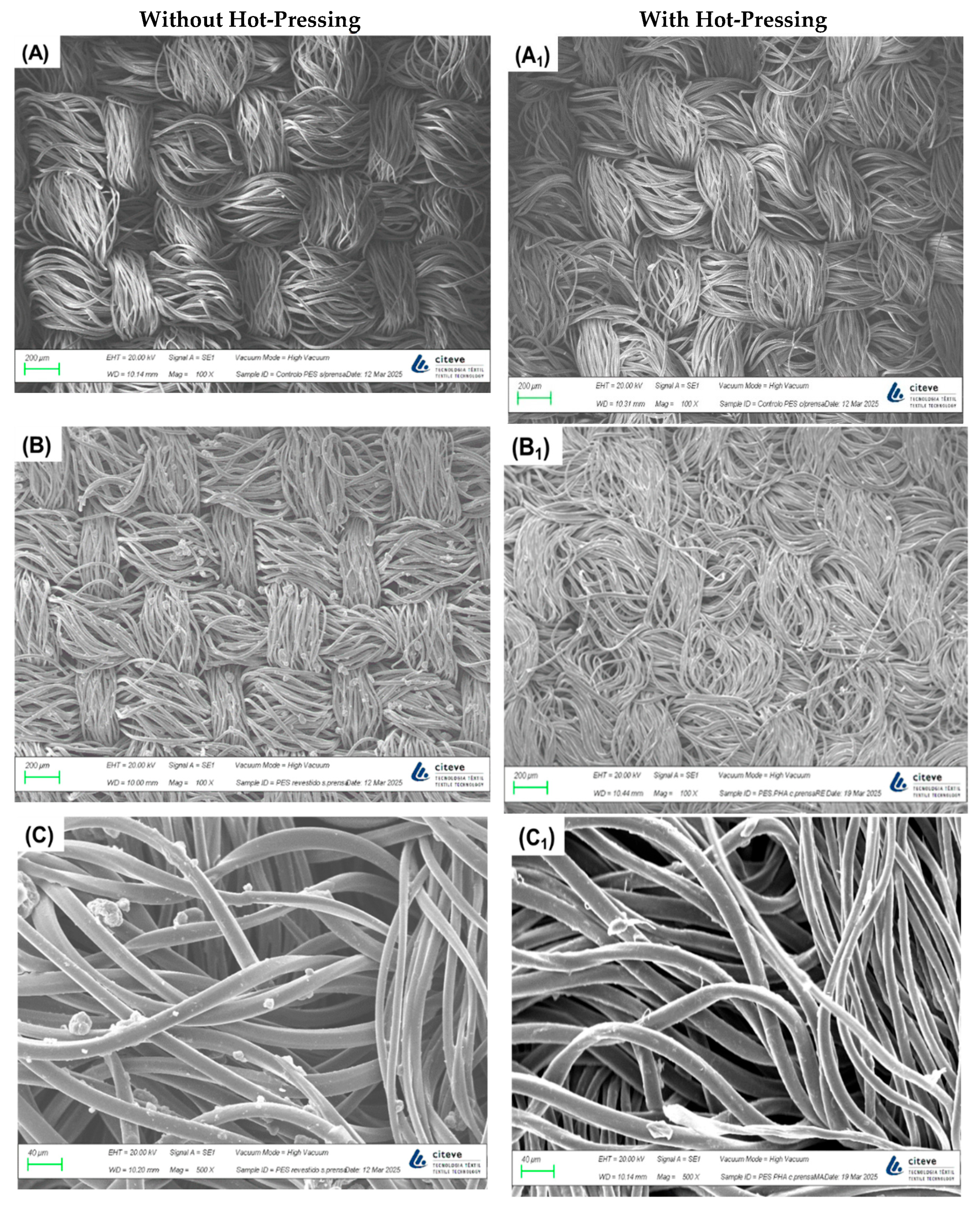

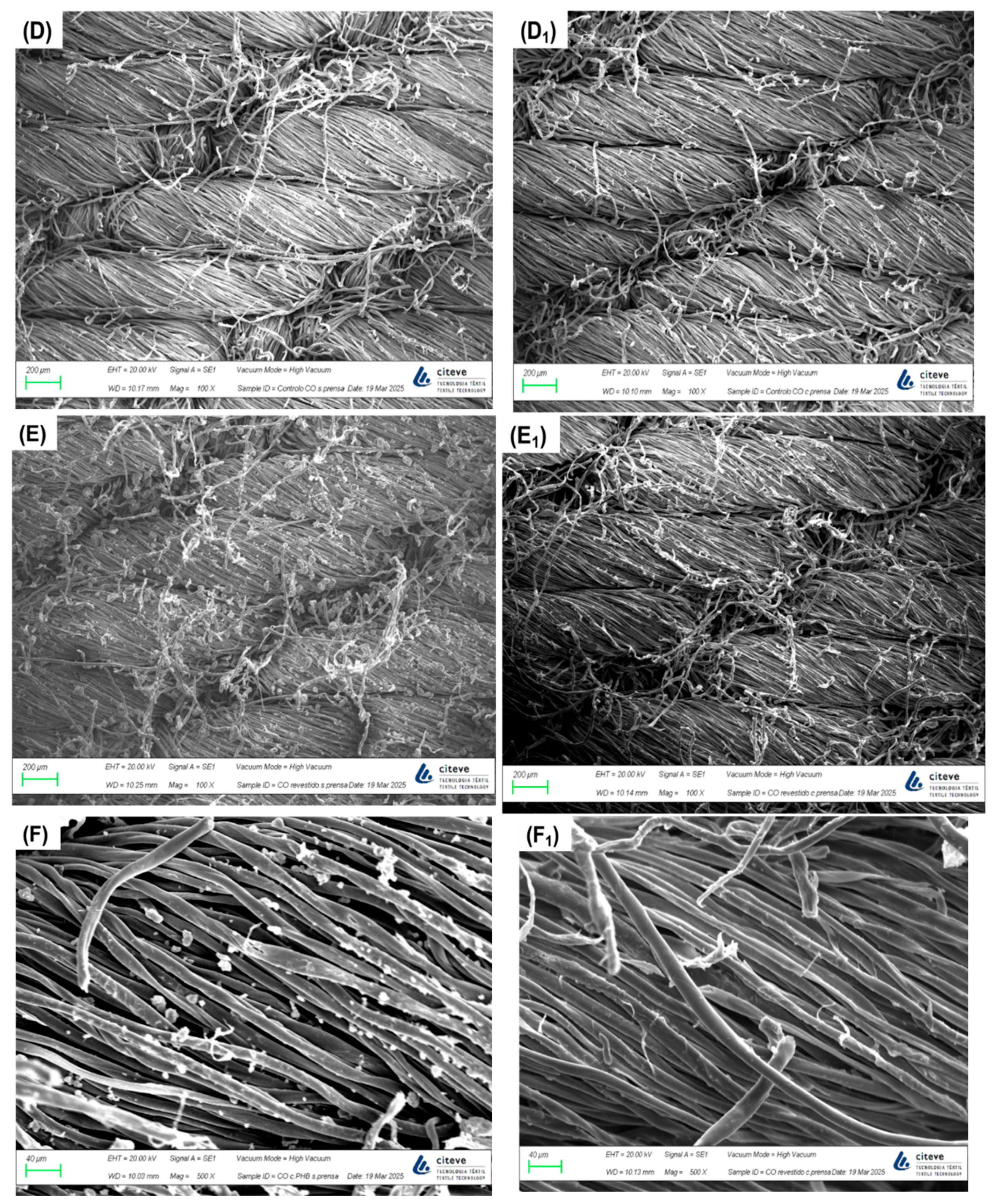

3.2. Morphological Analysis of Fabrics Coated with PHB.E.0 Dispersions

To confirm and analyse the presence of PHB.E.0 on the textile substrates after the spray process, SEM imaging was performed (

Figure 1). The control PES and CO fabrics (images A and D) exhibited smooth surfaces, especially in the PES samples. After applying the polymeric spray finish, distinct particle deposition was clearly visible (images B, C, E and F). These micrographs demonstrate the effectiveness of the coating process, confirming the successful deposition of PHB.E.0 on the fabric surfaces. The coated textiles showed a uniform and homogeneous distribution of the polymeric material throughout the fabric matrix, indicating consistent coverage. In samples subjected to hot-pressing, the fibres appeared more compacted and flattened (images A

1, B

1, D

1 and E

1). At higher magnifications (C and F), PHB.E.0 was observed not only coating the fibre surfaces but also partially embedded within the fabric structure, further confirming the polymer’s penetration during the spray-coating process.

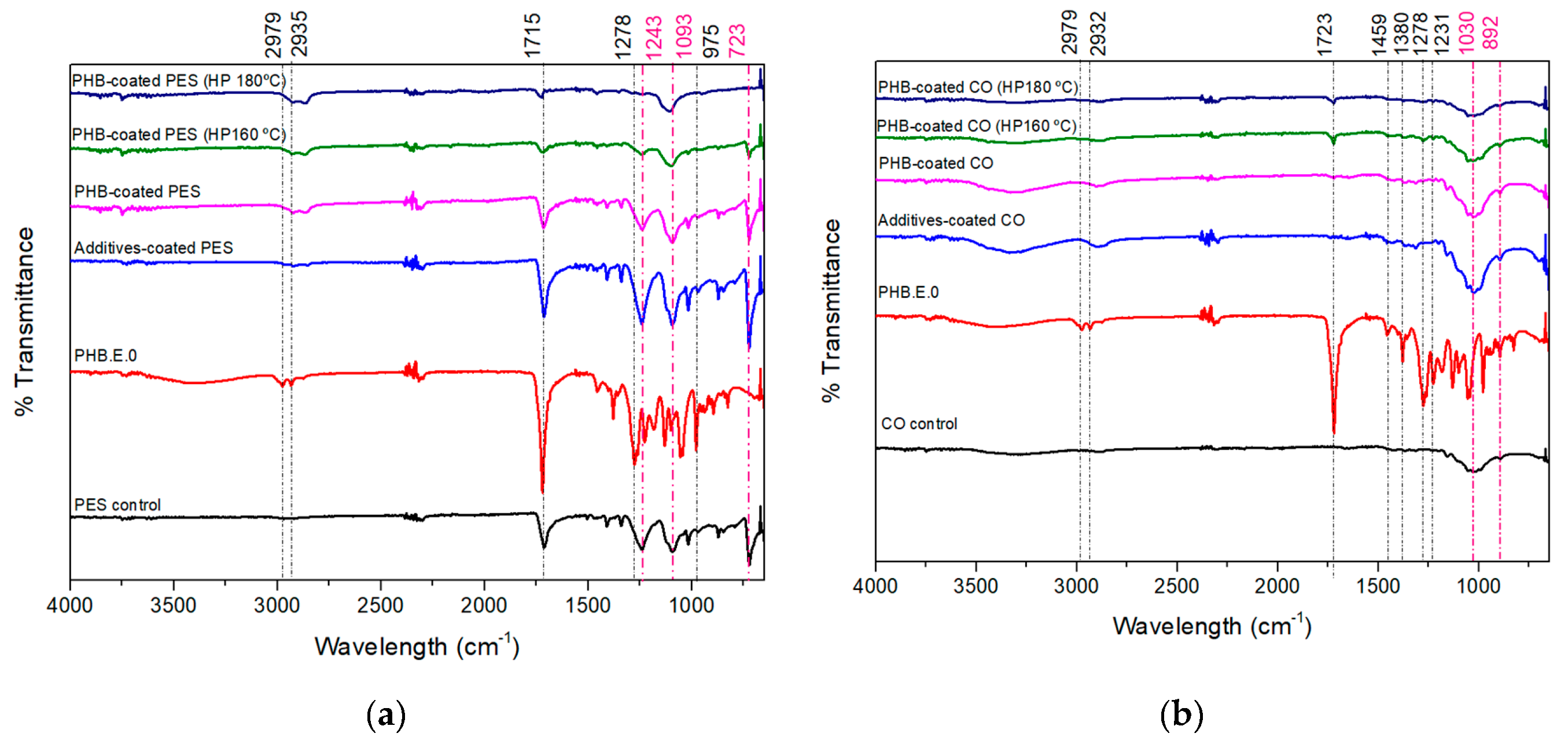

3.3. ATR-FTIR Analysis

To assess the presence of PHB.E.0 on the fabrics, and to investigate potential interactions between the polymer and the textile substrate, ATR-FTIR was conducted. The FTIR spectra of uncoated fabrics (PES and CO), PHB.E.0 polymer powder, and PHB.E.0-coated fabrics are presented in

Figure 2. The spectra clearly reveal the chemical identities of both textile substrates used. The spectrum of the PES substrate (

Figure 2a) displays the characteristic absorption bands of aromatic polyester. The most prominent peak appears at 1715 cm⁻¹, attributed to the stretching vibration of the ester carbonyl (C=O) group. A strong band at 1243 cm⁻¹ corresponds to C–O stretching of the aromatic ester linkage, while the band at 1093 cm⁻¹ is associated with C–H in-plane bending of the aromatic ring. Additionally, a band at 723 cm⁻¹ indicates aromatic C–H out-of-plane bending, another typical feature of PES [

26,

27]. The CO substrate (

Figure 2b) also exhibits its expected spectral features, confirming the presence of cellulose. Notably, a strong band at 1030 cm⁻¹ is assigned to C–O stretching vibrations in the polysaccharide backbone, while the band at 892 cm⁻¹ is attributed to the β-glycosidic linkage, a key marker of cellulose structure [

28,

29].

The spectrum of PHB.E.0 powder exhibits the characteristic bands of PHAs, confirming the chemical identity of the synthesized polymer. The most prominent absorption band appears at ≈1720–1723 cm⁻¹, corresponding to the C=O stretching vibration of the ester carbonyl group, a primary fingerprint for the aliphatic polyester backbone of PHAs [

30,

31]. In addition, well-defined bands are observed at ≈2931 cm⁻¹ and ≈2876 cm⁻¹, attributed to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of CH₃ and CH₂ groups, respectively, from the alkyl side chains. A set of bands between 1000 and 1300 cm⁻¹, particularly at 1276 cm⁻¹, are assigned to C–O–C stretching and CH bending, further supporting the presence of ester linkages and methylene groups. Additional bands at 1457 cm⁻¹ and 1380 cm⁻¹ are due to CH₂ scissoring and CH₃ symmetric bending, respectively, features typical of semi-crystalline PHAs [

30,

31,

32].

These characteristic PHB.E.0 peaks are more distinctly observed in the PHB.E.0-coated CO fabrics, likely due to their different composition. Nevertheless, in the PHB.E.0-coated PES fabrics, key PHA-related bands at ≈2935 cm⁻¹ and ≈2979 cm⁻¹ remain well visible, confirming also the presence of the polymer coating on the synthetic substrate (

Figure 2a).

Therefore, FTIR analysis confirms not only the chemical identity of the PES and CO substrates and the PHB.E.0 polymer, but also the successful deposition of the coating onto both textile surfaces, as evidenced by the presence and persistence of the characteristic PHB.E.0 absorption bands in the coated samples.

3.4. EDS Analysis

To evaluate the efficiency of the PHB.E.0 coating, surface elemental composition analyses were conducted on the textile substrates before and after the coating process (

Table 1). This technique utilizes a focused electron beam to excite atoms at the sample surface, inducing the emission of characteristic X-rays specific to each element. By detecting these emissions, EDS enables semi-quantitative determination of elemental composition, including atomic and weight percentages, within the analysis depth of a few micrometres [

33]. The P3HB-diol used in this researcher is a member of the PHA family, a class of biopolyesters composed primarily of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O). The repeating monomer units in PHAs are typically hydroxyalkanoic acids (e.g., 3-hydroxybutyrate), which contain ester functional groups and hydrocarbon backbones, resulting in a polymer structure rich in carbon and oxygen atoms [

34]. Therefore, the observed increase in the relative surface concentrations of carbon and oxygen, as detected by EDS after coating, is consistent with the successful deposition of PHB.E.0 [

35]. This trend was consistently observed across both fabric types, PES and CO, and under both processing conditions, with and without hot pressing.

For instance, in PES fabrics without hot-pressing treatment, the atomic concentration of carbon increased from 59.8% in the control sample to 61.0% after coating, while oxygen content rose from 35.7% to 38.7%.

In CO fabrics, the control sample exhibited a high oxygen content (51.7%), consistent with the cellulose-based composition. After coating, the carbon content increased to 54.7% after hot pressing (from 48.3%), while oxygen decreased to 45.3%, confirming successful deposition of the PHB.E.0 layer.

Overall, the EDS results demonstrate effective surface modification of both PES and CO fabrics through the applied coating process.

3.5. TGA Analysis

TGA was conducted to evaluate the presence of PHB.E.0 on the fabrics and to assess the impact of the coating on the thermal properties of the treated textiles. It was performed on neat PHB.E.0 powder, uncoated textile substrates (CO and PES), and on PHB.E.0-coated substrates both without hot-pressing and after being subjected to hot-pressing at 160 °C and 180 °C. The TGA and corresponding derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves, carried out to identify the temperature ranges corresponding to the most prominent degradation events, are presented in

Figure S1 and S2 (in support information), and the numerical results for onset temperature, maximum degradation temperature (T

d), and weight loss are summarized in

Table 2. The degradation profiles revealed three main stages: an initial step, observed exclusively in cotton-based samples, related to the evaporation of adsorbed and absorbed moisture; a second step, attributed to the degradation of the PHB.E.0 coating; and a third step, corresponding to the thermal decomposition of the textile substrates themselves. The neat P3HB diol (PHB.E.0) exhibited a single-stage thermal degradation process, initiating at approximately 283.4 ± 3.4 °C with a weight loss of about 97.7%. The onset temperature of the PHB.E.0 layer varied depending on the substrate, indicating that the textile substrate plays a role in modulating the thermal behaviour of the coating. Specifically, the onset temperature was lower for PES (238.7 ± 8.8 °C) compared to CO (252.2 ± 11.3 °C), despite PES exhibiting a much higher thermal degradation temperature (421.0 ± 1.6 °C) and greater residual mass than CO (354.3 ± 1.7 °C). This discrepancy suggests that CO provides a more thermally protective and compatible interface for PHB.E.0. The improved performance on CO is likely related to the presence of hydroxyl groups on cellulose chains, which can engage in hydrogen bonding with the ester and hydroxyl functionalities of PHB.E.0, promoting more interfacial interactions. Furthermore, the porous and fibrous morphology of the CO substrates may facilitate a more uniform anchoring of the coating, while their degradation behaviour may promote the formation of a char barrier that thermally shields the PHB.E.0 layer. In contrast, the PES surface, being less chemically reactive and less porous, may limit adhesion and interfacial bonding, leaving the coating more exposed to thermal stress. The influence of hot-pressing was also substrate dependent. On coated CO substrates, the onset temperature of PHB.E.0 increased with pressing temperature, rising from 252.2 °C (no pressing) to 254.5 °C and 259.1 °C at 160 °C and 180 °C respectively, likely due to improved hydrogen bonding or physical entanglement under heat and pressure, resulting in a more compact and stable interface. However, on coated PES substrates, the onset temperature decreased from 238.7 °C (no pressing) to 229.1 °C and 219.6 °C following hot-pressing at 160 °C and 180 °C respectively, suggesting that thermal treatment may induce unfavourable morphological changes or weaken the adhesion between the PHB.E.0 coating and the PES substrate. Although PES exhibits inherently high thermal stability at its core, the observed interfacial degradation of the PHB.E.0 layer under these conditions indicates limited compatibility between the coating and substrate, resulting in a reduced protective effect. The relative weight loss attributed to the PHB.E.0 coating ranged from 1.3% to 1.8%, slightly below the initial polymer loading of 2%, suggesting minimal polymer loss during processing. Despite this slight reduction, the PHB.E.0 coating provides valuable insights into the establishment of interfacial interactions between the polymeric layer and the studied substrates.

3.6. Wettability Analysis

Static contact angle measurements were performed to evaluate the surface wettability of the fabrics both before (controls) and after PHB.E.0 coating, as well as to investigate the impact of varying hot-pressing temperatures on this property (

Table 3). As PHAs are well known for their intrinsic hydrophobicity, it would be expected that the coated textiles would be more repellent to water than the uncoated textiles [

36]. However, under all tested conditions, the fabrics consistently exhibited hydrophilic behaviour, likely due to the low concentration of PHB.E.0 in the formulation and the high content of hydrophilic additives.

Control PES fabrics not subjected to hot-pressing exhibited a moderate contact angle of 63.93°, indicative of partial surface wettability. Hot pressing at 160 °C enhanced the surface hydrophilicity, as evidenced by a reduced contact angle of 50.30°. In contrast, increasing the temperature to 180 °C resulted in a rise in the contact angle to 86.96°, indicating decreased wettability. This reduction may be attributed to thermal restructuring or surface smoothing of the thermoplastic PES fabric induced specifically at 180 °C, which likely altered its surface energy. A similar effect was reported in the study developed by Oh et al. [

37], where thermal treatment altered the surface properties leading to increased hydrophobicity. However, control samples treated only with surfactant and dispersant, without polymer, demonstrated immediate drop absorption. Tween 80, a non-ionic surfactant, and Disperbyk 190, a polymeric dispersing agent, both contain hydrophilic groups that strongly interact with water molecules, promoting rapid water adsorption on the fabric surface [

38]. PHB.E.0-coated PES samples exhibited immediate water absorption under all tested conditions, except after hot pressing at 180 °C, where a measurable contact angle of 49.73° was recorded, indicating the surface remained hydrophilic, although less than in the other conditions. The increase in contact angle observed after hot pressing at 180 °C is likely attributed to subtle surface modifications of the PES fabric induced by the thermal treatment, as supported by TGA analysis (with the lowest onset temperature) and consistent with trends noted in the uncoated control samples. The immediate water absorption observed in coated samples, both untreated and hot-pressed at 160 °C, is likely due to the low concentration of PHB.E.0, its diol nature with available hydroxyl groups, and the presence of hydrophilic additives in the formulation. Overall, the results suggest that at the applied concentration, the PHB.E.0 coating did not significantly alter the surface energy nor confer hydrophobic character to the fabric.

Regarding CO fabrics, inherently hydrophilic, exhibited immediate water absorption across all control and PHB.E.0-coated samples, irrespective of the hot-pressing temperature. This behaviour confirms that the surface properties of cotton remained unaffected, consistent with its strong natural affinity for water. Unlike PES, cotton control fabrics were not subjected to hot pressing, as cotton is not a thermoplastic polymer. Additionally, the concentration of PHB.E.0 applied was insufficient to significantly modify surface energy or impart hydrophobicity to cotton, paralleling the findings observed for PES fabrics.

3.7. Water Absorption Test

The water absorption capacity of fibres is a critical factor influencing the thermal comfort of sportswear by facilitating moisture management and aiding in body temperature regulation through sweat wicking; therefore, this property was evaluated alongside contact angle measurements [

39]. Water absorption data complemented contact angle analysis to provide a comprehensive understanding of fabric wettability and moisture-handling behaviour.

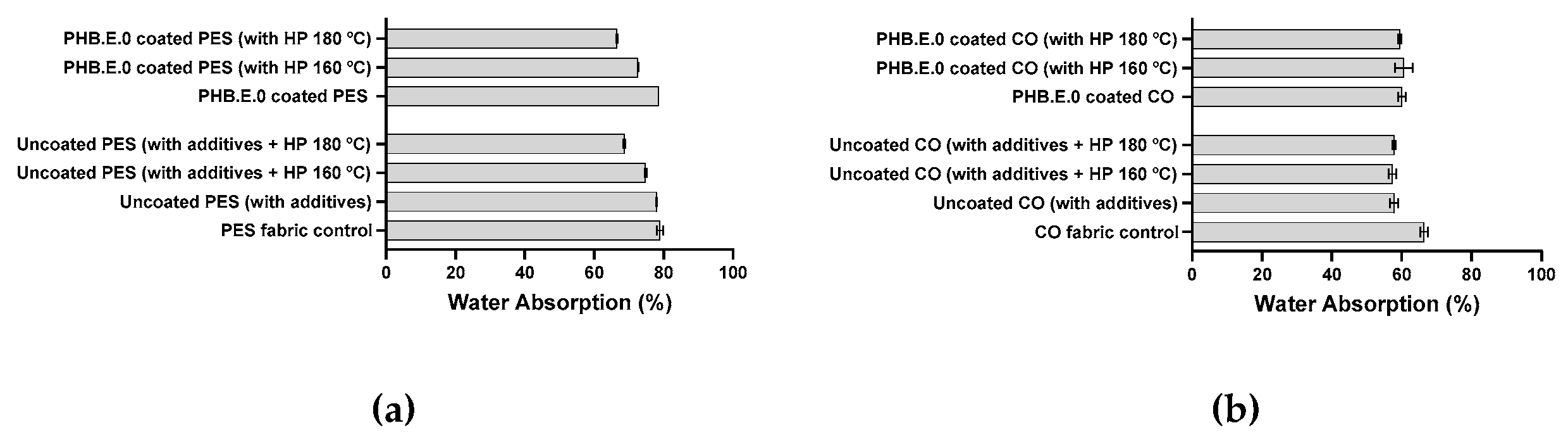

In uncoated PES fabrics, a clear correlation between contact angle and water absorption was observed. Application of hot pressing at 180 °C significantly reduced water absorption from 78.9% to 66.8%, concomitant with a slight increase in contact angle, indicating decreased surface wettability. Samples treated solely with additives exhibited water absorption values comparable to untreated PES, suggesting that despite rendering the surface highly hydrophilic (as evidenced by the absence of a measurable contact angle), additives alone did not enhance water uptake within the substrates structure. Similarly, PHB.E.0-coated PES fabrics showed negligible variation in water absorption, consistent with contact angles remaining within the hydrophilic regime. The observed reduction in water absorption following hot pressing is attributed primarily to surface morphology alterations arising from the thermoplastic nature of PES, as corroborated by TGA analysis, rather than from the polymer coating itself. Consequently, PHB.E.0 coatings at the applied concentration exert minimal influence on the water absorption of PES substrates.

In contrast, uncoated CO fabrics that did not undergo hot pressing displayed slightly higher water absorption (≈66%) relative to those subjected to thermal treatment (≈59%). This decrease is likely attributable to increased fibre densification induced by the hot-pressing process, as supported by SEM micrographs (

Figure 1). Notably, CO fabrics hot-pressed at 160 °C and 180 °C demonstrated comparable water absorption levels, indicating that once fibre compaction is achieved, further increases in pressing temperature exert limited additional effect on moisture uptake. For CO fabrics coated with PHB.E.0, a modest reduction in water absorption was observed relative to their uncoated counterparts, likely due to the polymer coating partially masking cotton’s intrinsic hydrophilicity and abundant hydroxyl groups. Among these coated samples, those hot-pressed at 180 °C exhibited the lowest water absorption (≈54%), which may be associated with enhanced interfacial interactions between PHB.E.0 and the substrate facilitated by this temperature, as evidenced by TGA results. Collectively, these findings indicate that the PHB.E.0 coating alone has a limited effect on the water absorption properties of both PES and CO substrates, with hot pressing also contributing to changes in surface wettability.

Figure 3.

Water absorption values (%) of (a) PES fabric control (uncoated PES) and PHB.E.0 coated PES; (b) CO fabric control (uncoated CO) and PHB.E.0 coated CO.

Figure 3.

Water absorption values (%) of (a) PES fabric control (uncoated PES) and PHB.E.0 coated PES; (b) CO fabric control (uncoated CO) and PHB.E.0 coated CO.

3.8. Permeabilities

Both air permeability and water vapor permeability are critical metrics to evaluate textile breathability, as they directly regulate the exchange of heat and moisture vapor between the skin and the ambient environment. Efficient breathability facilitates sweat evaporation through the fabric, thereby maintaining skin dryness and overall thermal comfort for the wearer [

37]. To elucidate the effects of PHB.E.0 coating and hot-pressing treatment on the breathability of the PES and CO fabrics, comprehensive air and water vapor permeability assessments were conducted (

Table 4).

For PES substrates, the untreated control fabrics (original fabrics) exhibited high air permeability (670.0 l/m²/s) alongside substantial water vapor permeability (574.9 g/m²/24 h), reflecting its inherently porous and breathable structure. Hot pressing at 180 °C of these uncoated PES substrates caused a substantial reduction in air permeability by approximately 81% (down to 128.0 l/m²/s), while water vapor permeability slight decreased (568.0 g/m²/24 h). This pronounced decline in air permeability is attributed to thermally induced densification and surface restructuring, characteristic of the thermoplastic behaviour of PES, as evidenced by morphological analyses and TGA observations. The resulting fibre compaction reduces pore size and inter-fibre spacing, significantly restricting convective airflow but preserving vapor diffusion pathways. Consequently, the fabric retains its ability to transport moisture vapor despite the notable reduction in air exchange. In relation to treatment exclusively with surfactant and dispersant additives, a significant reduction (≈ 48%) in air permeability was observed (346.0 l/m²/s), without significantly impacting water vapor permeability. These findings suggest that the application of additives contributes to altering the fabric’s physical porosity without affecting its capacity for vapor transmission. Similarly, applying the PHB.E.0 coating without subsequent thermal treatment led to a significant reduction in air permeability (≈ 49%, 344.0 l/m²/s) compared to the untreated control fabric. In contrast, water vapor permeability was only marginally affected (≈1%), indicating that the concentration of PHA applied was relatively low. Although PHAs are inherently hydrophobic and typically serve as effective barriers to water vapor, the results observed were comparable to those of the uncoated samples [

40].

However, it is important to note that the air permeability of PHB.E.0-coated PES did not differ significantly from that of the PES substrate modified solely with additives, suggesting that the polymer had limited influence on this parameter. When PHB.E.0-coated PES fabrics were hot pressed at 180 °C, air permeability further decreased to 171.0 l/m²/s, representing a 74% reduction compared to the untreated control, accompanied by a slight decrease in water vapor permeability (564.0 g/m²/24 h). However, comparing PHB.E.0-coated PES fabrics hot pressed at 180 °C to those not hot pressed, air permeability was reduced by approximately 50%, while the change in water vapor permeability remained insignificant. These findings emphasize that the thermal treatment is the primary factor influencing permeability, particularly air permeability, under these conditions.

In contrast, CO fabrics naturally exhibited significantly lower air permeability (50.2 l/m²/s) due to their denser fibrous structure (higher grammage), while maintaining a water vapor permeability (571.4 g/m²/24 h) comparable to that of PES samples. Treatment with additives and PHB.E.0 coating further reduced air permeability to approximately 32–39 l/m²/s, representing decreases of 23% and 37%, respectively, with negligible effects on vapor permeability. Notably, PHB.E.0-coated CO fabrics subjected to hot pressing at 180 °C exhibited the lowest air permeability (29.8 l/m²/s), corresponding to a 40% reduction relative to untreated control CO fabrics, alongside a slight increase in water vapor permeability (577.6 g/m²/24 h). This indicates that thermal compaction restricts convective airflow but may enhance microstructural pathways that favour vapor diffusion. This nuanced behaviour in CO fabrics highlights the complex interplay between natural fibre morphology and thermal processing.

Across all treatments, the water vapor permeability index (I%) remained consistently high (≈ 92–97%), confirming the fabrics’ effective capacity for moisture regulation. These findings indicate that the PHB.E.0 coating, combined with subsequent hot-pressing, successfully reduces air permeability, a potentially beneficial effect when enhanced wind resistance or structural integrity is desired without compromising breathability. Notably, hot pressing appears to be the primary driver of these changes, promoting structural rearrangements that reduce air permeability while maintaining the vapor permeability essential for wearer comfort. Overall, these insights offer valuable guidance for the development of functional textile coatings intended to enhance everyday user comfort, with potential applications in performance and outdoor settings.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates the successful development and application of a sustainable coating system based on chemically modified poly(3-hydroxybutyrate)-diol (PHB.E.0), formulated as an aqueous dispersion and applied to PES and CO fabrics via a solvent-free spray-coating technique. The coating process was confirmed through morphological, chemical, and thermal analyses, including SEM, ATR-FTIR, elemental analysis, and TGA.

Despite the addition of the biopolymer layer and subsequent thermal treatment, the coated textiles retained their hydrophilic character, facilitating moisture uptake and transfer, while maintaining high water vapor permeability, essential for breathability. At the same time, a significant reduction in air permeability was achieved, particularly in hot-pressed samples, indicating improved wind resistance. These enhancements were achieved without compromising vapor transport, reflecting a well-balanced improvement in textile functionality.

This work serves therefore as a first step toward understanding the interactions between PHB.E.0 and both synthetic and natural fibre substrates. TGA results highlight substrate-dependent thermal behaviour and suggest complex interfacial phenomena that merit further investigation. Given the intrinsic challenges in achieving strong interfacial adhesion between hydrophobic PHA and hydrophilic fibres, especially under mechanical or washing conditions, future work may be focused on evaluating adhesion performance and exploring strategies such as surface modification or compatibilizer incorporation to strengthen the polymer–substrate interface. Furthermore, the effect of increasing PHB.E.0 concentration on coating performance may be systematically explored to determine the optimal balance between coating thickness, durability, and breathability. Insights from these studies would inform the development of optimized, scalable formulations.

Overall, PHB.E.0 coatings offer a promising and environmentally responsible pathway for enhancing textile performance, contributing to the advancement of sustainable, high-performance materials for sportswear and technical apparel.