1. Introduction

Climate change is exerting unprecedented pressure on plant systems worldwide, challenging their survival through increased temperatures, altered precipitation patterns, and the intensification of abiotic stresses such as drought or salinity [

1]. These environmental perturbations not only compromise plant productivity and biodiversity but also affect global food security and ecosystem resilience [

2,

3].

In the last years,

Aloe vera (

A. vera) has emerged as a model of resilience among the plant species demonstrating remarkable tolerance to harsh environmental conditions [

2,

3,

4]. This succulent plant, native to arid and semi-arid regions, exhibits high adaptability to extreme drought and saline environments—conditions increasingly prevalent under current climate scenarios [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. From a physiological perspective,

A. vera reduces its foliar area to minimize evapotranspiration during prolonged drought periods and enhances the synthesis of aloin, polysaccharides, and phenolic compounds, along with an increase in antioxidant activity, as part of its defense response to stress [

2,

3,

8]. Indeed, a critical component of

A. vera’s stress resilience is the biosynthesis of acemannan, a bioactive acetylated polysaccharide stored in the parenchymatous gel of the plant [

5,

7,

8,

9], contributing to cellular water retention and stabilization of membrane structures [

5,

12]. At the molecular level,

A. vera deploys a series of biochemical and genetic strategies that underpin its survival under abiotic stress [

5,

12]. Thus, the enzyme glucomannan mannosyltransferase (GMMT), encoded by the

CSLA-9 gene, plays a key role in the synthesis of acemannan [

5]. Under stress conditions, upregulation of

CSLA-9 enhances acemannan production, improving the structural plasticity of

A. vera cell walls, including the modification of pectin composition and branching, supporting mechanical stability and stress signaling [

8,

9]. These molecular adaptations are accompanied by the accumulation of secondary metabolites with antioxidant properties, further protecting the plant from oxidative damage [

8].

Additional to this, one of the most prominent mechanisms involves the upregulation of stress-responsive genes related to the biosynthesis and signaling pathways of abscisic acid (ABA), a key phytohormone in drought and salinity tolerance [

5,

13,

14]. Within context, genes such as

ABA2 and

AOG, which regulate the biosynthesis and transport of active ABA, are significantly modulated under water-deficit conditions [

13,

15]. The elevated expression of these genes facilitates stomatal closure, minimizes water loss, and activates downstream protective responses, including antioxidant defense systems and osmoprotectant accumulation [

1,

13,

16,

17].

Understanding the molecular and physiological mechanisms that confer stress tolerance in

A. vera offers valuable insights into the design of climate-resilient crops. As global temperatures continue to rise, harnessing such natural resilience—either through genetic engineering or cross-breeding strategies—may be crucial for sustaining agricultural productivity in vulnerable regions [

18].

2. Results

2.1. RNA Extraction and Quality

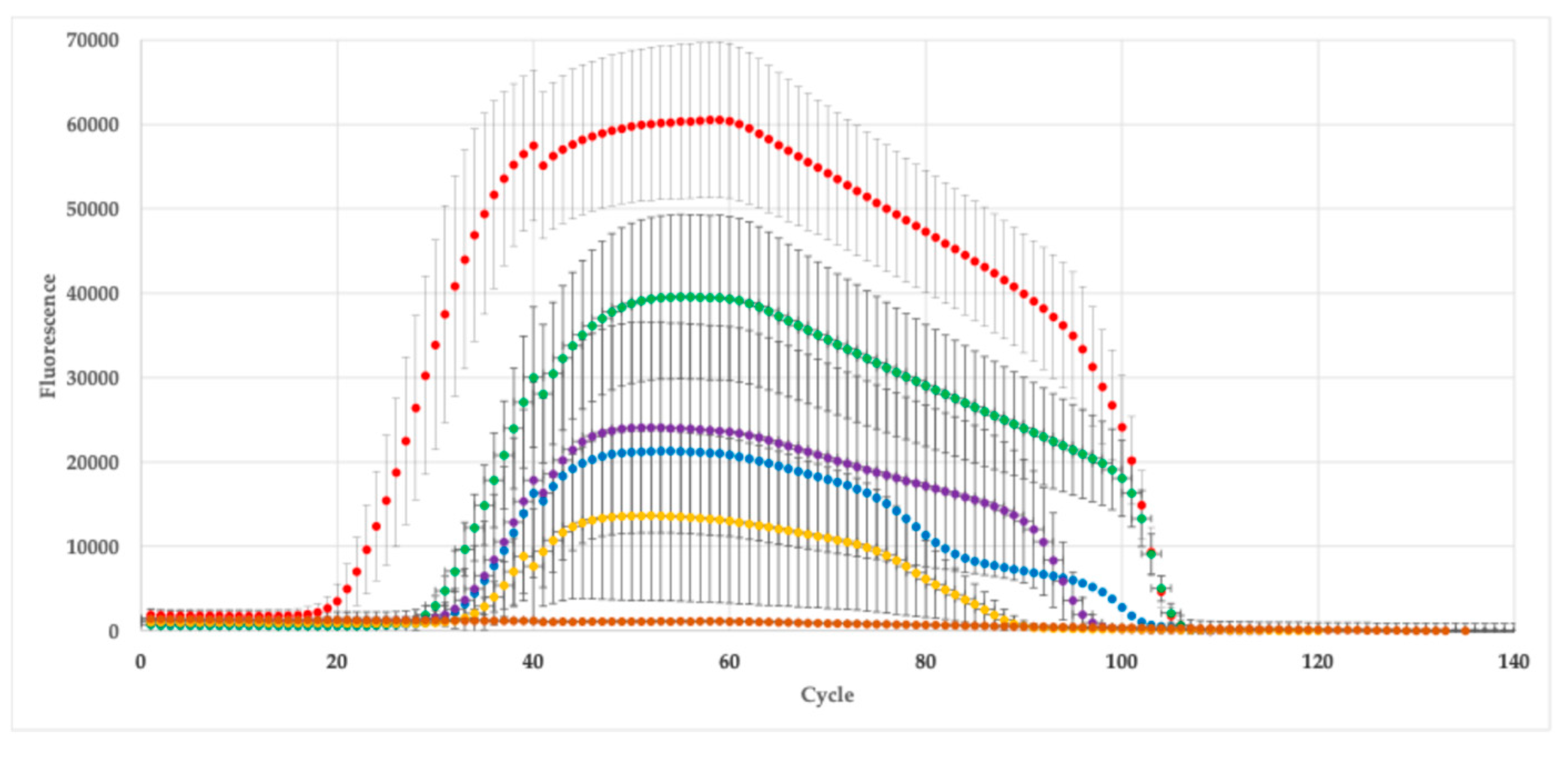

The genes

ACT (actin),

GMMT,

AOG, and

ABA2 showed well-defined amplification curves, with a clear exponential phase and high fluorescence levels, indicating good efficiency and specificity. Opposite to this, the

ABA8 and

ZEP genes exhibited very low or flat signals, without reaching significant fluorescence levels, suggesting low expression (

Figure 1). Thus, these last genes were excluded from further analysis.

2.2. Expression of Key Gens on Aloe vera Under Saline-Water Stress

2.2.1. Expression of AOG Gen on Aloe vera Under Saline-Water Stress

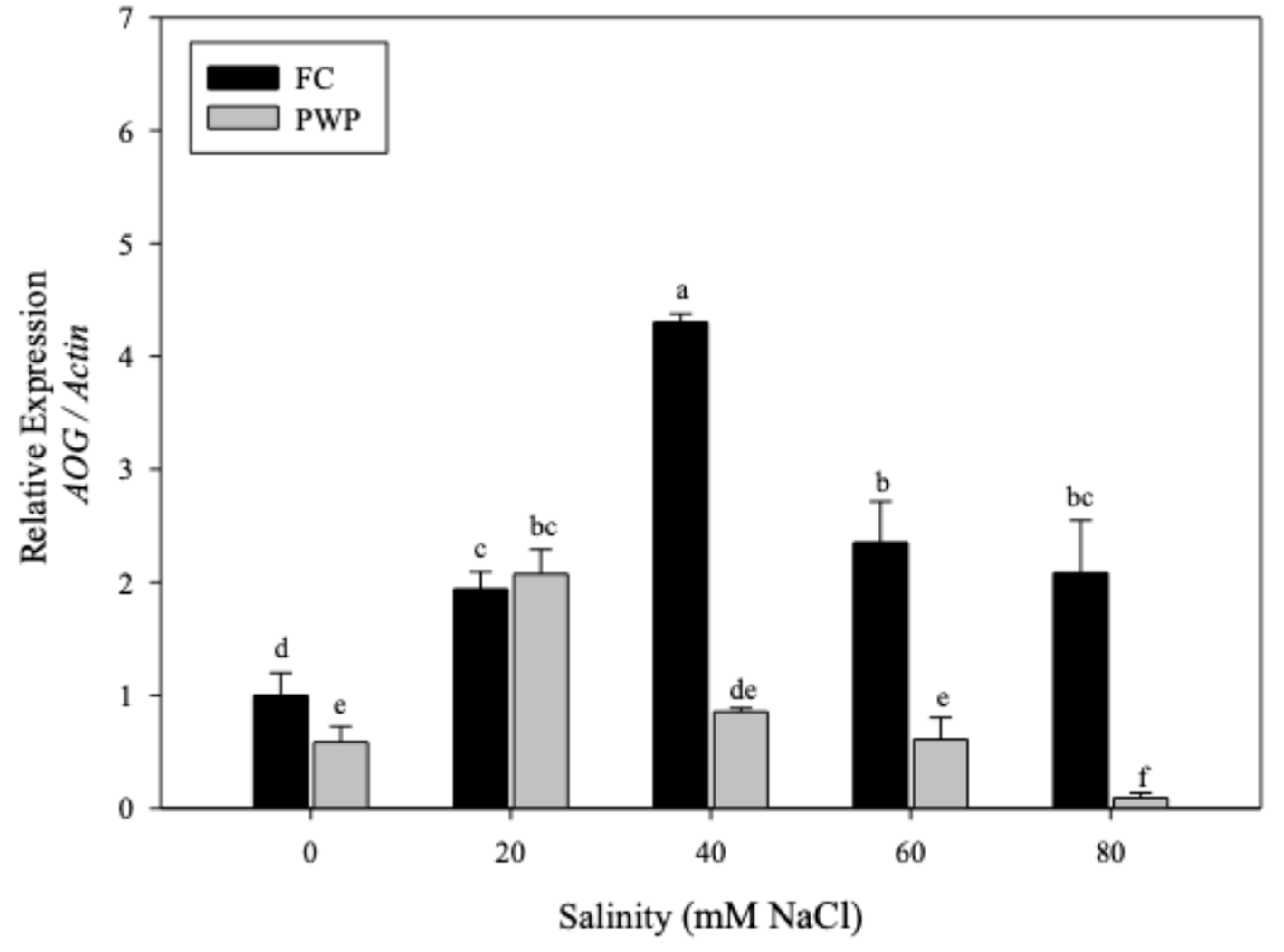

The expression of

AOG gene in

A. vera plants grown under saline-water stress is showed in

Figure 2. As can be seen, the

AOG expression was significantly affected by saline-water stress (

p < 0.05). The

AOG expression ranged from 0.1% to > 4%, being the lowest expression observed in those plants grown at the higher stress conditions (S80WD) whereas those plants grown under 40 mM salinity but irrigated at FC exhibited the highest expression of this gen. It is important to note that the

AOG expression was more affected by water deficit than by saline stress, with most of the plants grown under water deficit exhibiting the lowest expression, >1%. Interestingly, those plants taken as a control exhibited a relative expression of

AOG gene of 1 ± 0.3%.

2.2.2. Expression of ABA2 Gen on Aloe vera Under Saline-Water Stress

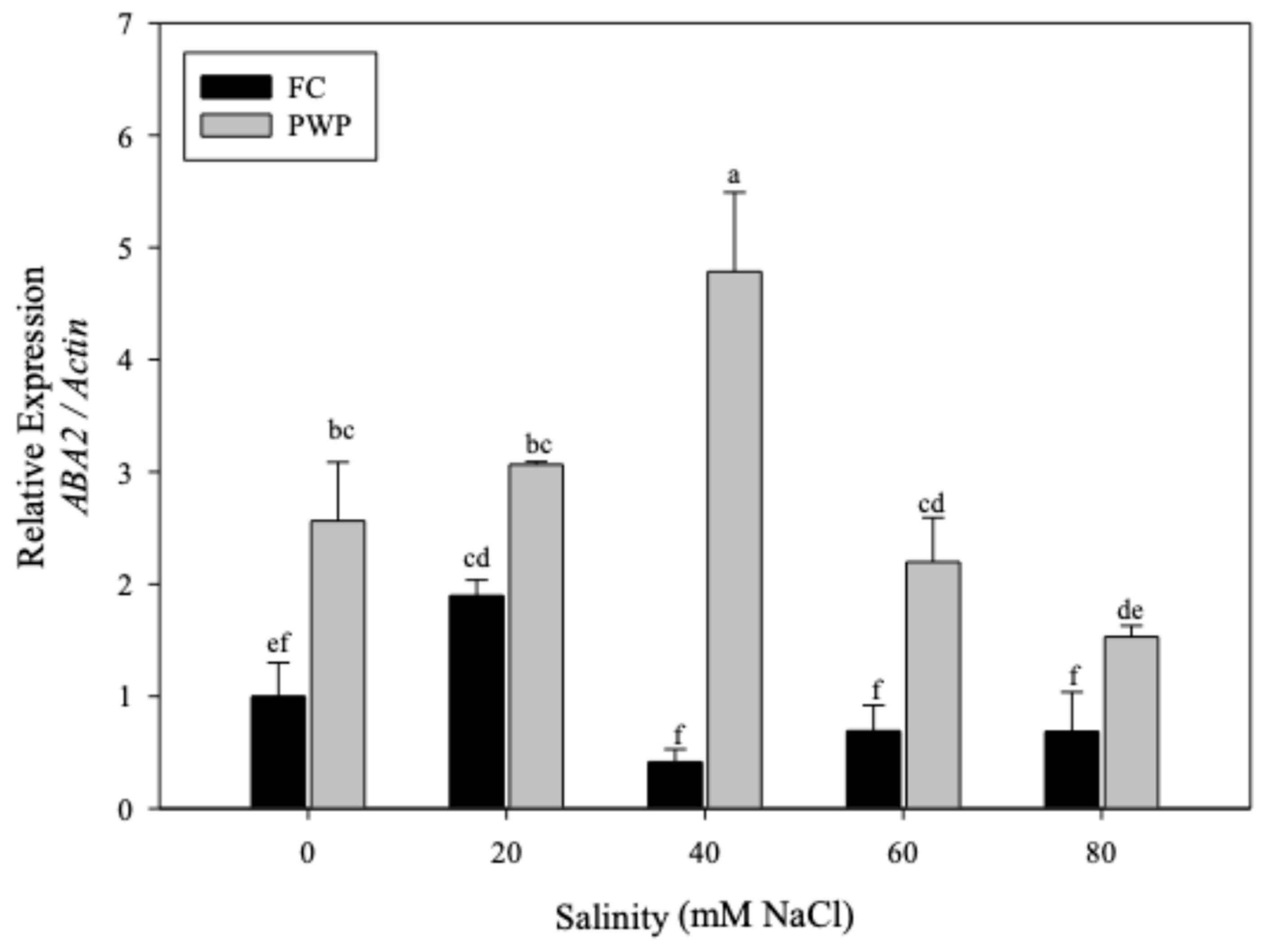

The relative

ABA2 expression showed significant differences between treatments (

p < 0.05) (

Figure 3). Interestingly, this gene exhibited larger expression than

AOG when

A. vera plants were subjected to salinity-water stress, reaching expression levels around 5.5%. Further, those plants grown at field capacity (FC) conditions exhibited lower

ABA2 expression than plants under permanent wilting point (PWP) conditions. Notably, those plants grown under PWP conditions and 40 mM salinity showed positive regulation, denoted by expression levels increasing approximately four-fold compared to the control samples. Curiously, the lowest levels of

ABA2 were observed when

Aloe vera was grown under higher salinity conditions. Specifically,

ABA2 levels were reduced to less than 2% when salinity exceeded 40 mM salinity at PWP and dropped to below 1% when salinity was greater than 20 mM salinity at FC (

p < 0.05).

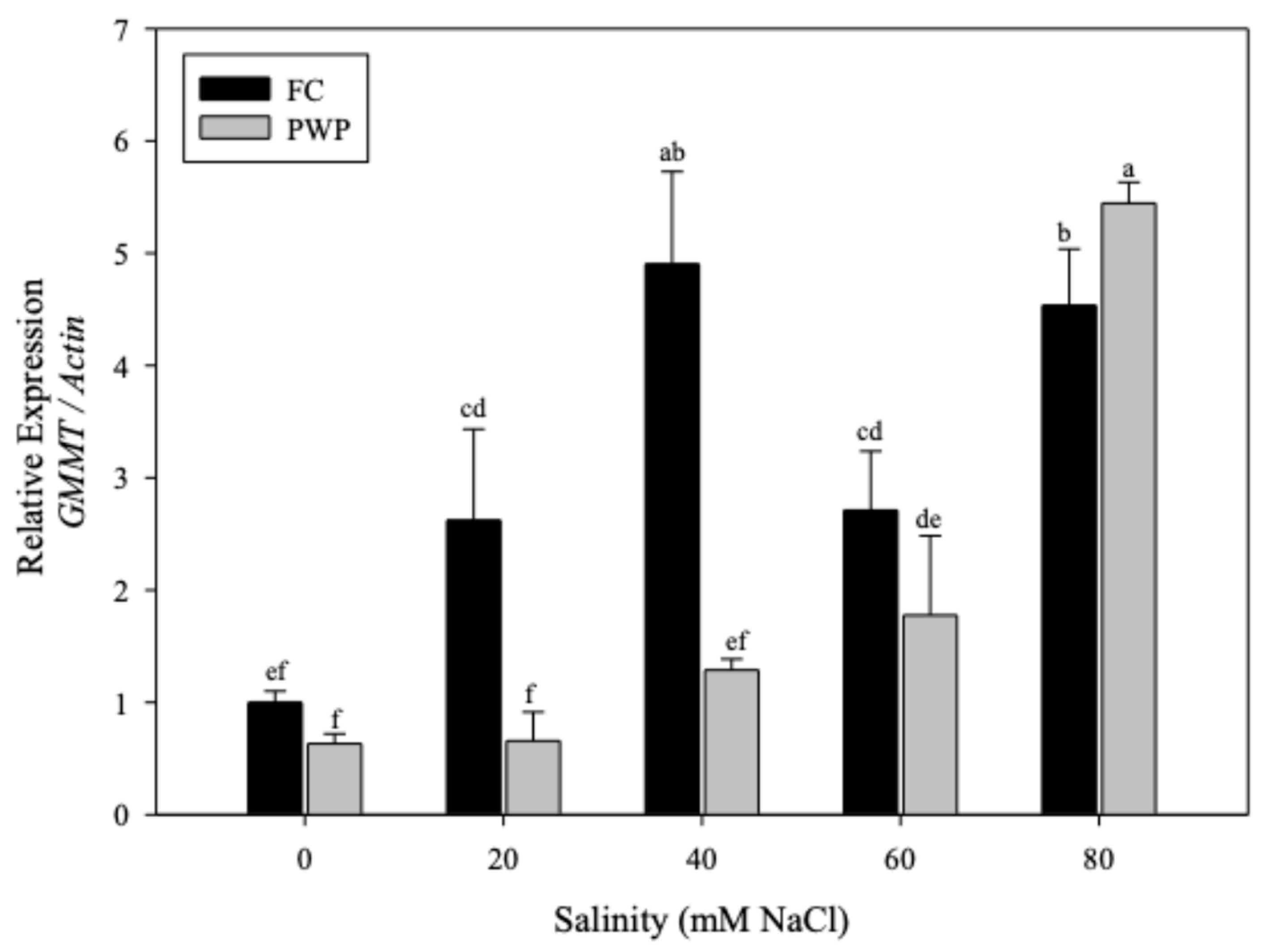

2.2.3. Expression of GMMT Gen on Aloe vera Under Saline-Water Stress

Saline-water stress promoted the overexpressing of the glucomannan mannosyl transferase (

GMMT) in

A. vera (see

Figure 4). The expression of

GMMT in

Aloe plants grown under FC was higher than those grown under PWP, except for plants exposed to the most extreme conditions (PWP with 80 mM salinity) (

p < 0.05). Interestingly, a significant increase of the GMMT levels was observed in those plants grown under 40mM salinity and FC. However, further increases in salinity led to a significant reduction in

GMMT expression. On the contrary,

Aloe vera grown under PWP condition reached the highest

GMMT levels at 80 mM, the most severe condition.

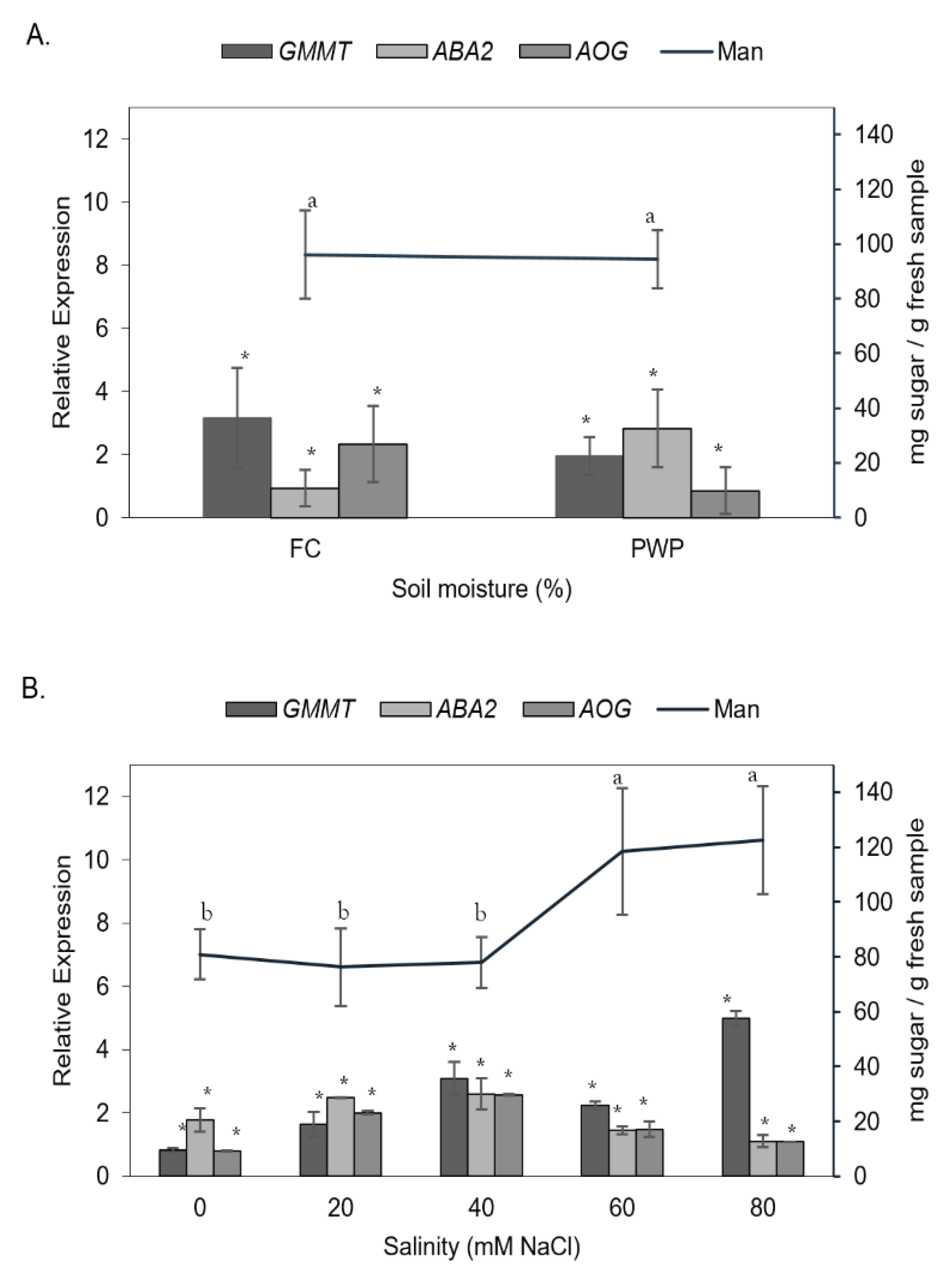

2.3. Biosynthesis of Mannose-Rich Polysaccharides in Aloe vera

Mannose-rich polysaccharides play a key role in the stress tolerance of

A. vera plant. Thus, the content of mannose as a function of individual stressors, either water deficit or saline concentration, was evaluated (

Figure 5). As can be seen, the mannose content was not significantly affected by the soil moisture levels, FC or PWP (

p > 0.05). However, the salinity led to a significant increase in mannose, from ~60 up to ~140 mg/g sample, in the parenchymatous tissue (

p < 0.05). On the other hand, the effect of saline-water stress on

A. vera, the gene expression was also compared by individual stressors.

The expression of AOG and GMMT genes was higher in plants grown under FC conditions than in those under PWP. Notably, the ABA2 gene was overexpressed when A. vera was subjected to water restriction (PWP condition). Interestingly, the gene expression increased as salinity increased from 0 to 40 mM NaCl but decrease when salinity exceeded 40 mM, except for the GMMT gene, which was overexpressed near to 6%.

3. Discussion

Aloe vera (

Aloe barbadensis Miller) is without doubt one of the most popular plants used in traditional medicine, and recently, in food industry. This popularity has been largely attributed to the high adaptability to adverse environments, including drought and salinity conditions. However, despite its high tolerance to adverse conditions,

A. vera can still experience abiotic stress when water deficit and salinity occur simultaneously [

6,

8,

9].

Aloe vera’s tolerance to water and salt stress appears to be closely linked to the regulation of specific biosynthetic pathways mediated by abscisic acid (ABA), particularly those involved in the synthesis of acemannan, a functionally important acetylated glucomannan [

5]. Several studies have shown that ABA not only acts as a physiological regulator in response to water deficit but also directly modulates gene expression, promoting the synthesis of hydrophilic polysaccharides capable of retaining water in parenchymal tissues [

13,

14,

19]. In this context, the

CSLA9 gene, which encodes the enzyme glucomannan mannosyltransferase (

GMMT), has been identified as a central element in the synthesis of the acemannan skeleton [

5]. Evidence suggests that

GMMT expression is positively regulated by ABA, both under water stress conditions and through exogenous application of the phytohormone, with an overexpression of up to fourfold compared to the control group being observed after 48 h of ABA treatment [

5], indicating that

GMMT is an ABA-regulated gene, which represents a novel finding in CAM plants such as

A. vera.

At the metabolic level, a significant accumulation of acemannan was observed under combined stress conditions (water deficit and salinity), along with an increase in its acetylation level, suggesting a structural adaptation to enhance water retention [

8,

9]. In parallel, endogenous ABA levels progressively increase with stress severity, reaching increases of up to 15.5-fold compared to control, reinforcing its role as a molecular signal in this response [

5]. At this point, it is important to note the

GMMT activation does not occur in isolation, the genes

AOG and

ABA2, respectively involved in the transport of conjugated ABA (ABA-GE) and its conversion into active ABA, show expression patterns consistent with stress levels.

ABA2 was especially sensitive to water deficit, with overexpression under permanent wilt point (PWP) conditions and 40 mM salinity. For its part,

AOG showed differential regulation, decreasing drastically under high combined stress conditions, suggesting a limitation in the intracellular availability of active ABA under extreme conditions. Together, these findings highlight the ABA-GE → ABA activation pathway mediated by

AOG and

ABA2 as a key regulatory mechanism of

GMMT expression. The overexpression of the latter under stress suggests an adaptive mechanism by which

A. vera increases acemannan biosynthesis to counteract water loss and maintain the functional integrity of the gel. From a biochemical perspective, stress conditions also alter cell wall polysaccharides. Mannose content increased significantly under salinity, reinforcing the connection between gene regulation and mannose-rich polysaccharide accumulation. Both pectins and acemannan underwent structural changes: acetylation of acemannan increased by 90–150% under low humidity and high salinity, while pectin methylesterification remained high (~60%), thereby stabilizing the cell wall and preventing collapse [

8,

9]. These molecular and chemical responses converge to support the hypothesis that acemannan and pectins are central to the resilience strategy of

A. vera [

9].

The results of this study further demonstrate that abiotic stress represses

AOG expression as stress severity increases, whereas well-hydrated control plants exhibited the highest levels (10.3%).

AOG encodes an ABA-glucosyltransferase that conjugates ABA with glucose ester to form ABA-GE, an inactive storage form of ABA typically sequestered in vacuoles [

13]. Under severe stress,

Aloe vera prioritizes survival over productivity, entering dormancy and reducing

AOG activity. This aligns with the general role of ABA as a “stress hormone” [

13,

14]. Indeed, stress conditions trigger ABA biosynthesis, catabolism, and transport, leading to upregulation of genes in ABA metabolism and signaling [

20]. Accumulated evidence shows that cell wall polysaccharides synthesized by the cellulose synthase-like (

CSL) gene family are critical for plant development and stress tolerance. Several Arabidopsis

CSLA members, for instance, are involved in high-mannose polysaccharide synthesis [

21,

22]. In

A. vera,

GMMT has been consistently identified as a key ABA-regulated gene mediating water stress tolerance through the synthesis of mannose-rich polysaccharides [

5,

23]. In addition, the chemical modifications previously reported in key polysaccharides, such as the increased acetylation of acemannan combined with the structural stability provided by pectin, enhance water retention and cellular resistance, positioning

A. vera as an effective model for biochemical adaptation to multiple abiotic stresses.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

Aloe vera seedlings, aged 6 months and measuring between 25 and 30 cm, were used for the experiment. These seedlings were transplanted into 15 kg capacity pots filled with 10 kg of sandy loam soil collected from the study area. The experiment took place at the Regional University Unit for Arid Zones of the Autonomous University of Chapingo (Durango, Mexico) during the spring-summer of 2020. Five saline concentrations were tested: 0, 20, 40, 60, and 80 mM NaCl, along with two soil moisture levels: field capacity (FC) at 20.7% and permanent wilting point (PWP) at 12.3% soil water content [

3]. This setup resulted in ten treatments: five salinity treatments (S0, S20, S40, S60, S80) irrigated at FC, and five combined salinity and water deficit treatments (S0WD, S20WD, S40WD, S60WD, S80WD) irrigated at PWP. Plants grown under 0 mM salinity and irrigated at field capacity (S0) were used as the control sample. All plants were irrigated weekly according to the experimental treatments for a period of 3 months. Soil moisture was monitored using an Extech Soil Moisture Meter MO750 (Nashua, New Hampshire, USA) [

8].

After the stress treatments, the plants were carefully washed with distilled water using a spray bottle. For RNA extraction and subsequent RT-qPCR, the third leaf from the inside to the outside of the rosette of each plant was sectioned separately. The samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C until analysis.

4.2. RNA Extraction

The RNA extraction was carried out using the exocarp or leaf cortex, separated from the parenchyma. This cortex was frozen with liquid nitrogen and ground with a mortar and pestle. This tissue was chosen to avoid contamination with plant mucilage, as polysaccharides interfere with RNA extraction. Thus, 700 µL of extraction buffer (2% w/v CTAB, 2% w/v PVP, 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8, 25 mM EDTA, 2 M NaCl, 0.05% spermidine) and 100 µL of β-mercaptoethanol were added to the sample. The mixture was vortexed at maximum speed for 30 s. Then, it was incubated for 10 min at 65 °C, inverting the tube four times. 500 µL of chloroform were added, and the mixture was vortexed again at maximum speed for 30 s. It was then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and 350 µL of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) were added. The mixture was vortexed at maximum speed for 30 s and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and an equal volume of chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added. The mixture was vortexed for 30 s and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min. Again, the supernatant was transferred to a new tube, and 1/3 volume of 10 M LiCl was added. It was left to precipitate overnight at 4 °C. The sample was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 20 min, decanted, and the sediment was washed with 800 µL of 96% ethanol. The mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 5 min. The sediment was then washed with 800 µL of 70% ethanol and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 5 min. Finally, the sediment was decanted, dried at room temperature, and resuspended in 20 µL of DEPC water.

Then, a DNase treatment was performed to degrade residual DNA using DNase I RNase-free (Ambion Life Technologies) according to the provider’s instructions. Finally, the RNA extraction was evaluated for quantity, purity, and integrity using spectrophotometry (NanoDrop 2000, UV/Vis, Thermo Scientific) and horizontal electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels.

4.3. Primers

A quantity of 40 ng of total RNA per reaction was used to estimate the expression for the

ABA 8H,

ZEP,

ABA2,

AOG, and

GMMT genes, with

actin being the reference gene, using specific primers (Table 1). All primers were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich.

| Gene |

Encoded enzyme |

Primer Sequence |

Melting Temperature (°C) |

Amplicon size (bp) |

Reference |

| ABA 8H-F |

Abscisic acid

8′-hydroxylase |

5′-GAGAGAGAGAGGTGCTACATTTG-3′ |

54.0 |

206.0 |

[24] |

| ABA 8H-R |

5′-ATGTTTGGGTCTTGAGAGTAGAG-3′ |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| ZEP-F |

Zeaxanthin

epoxidase |

5′-GAAACTTGGGCAAAGGGAATG-3′ |

55.0 |

258.0 |

[24] |

| ZEP-R |

5′-CTTGTTGTACCCACCCTGATAG-3′ |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| ABA2-F |

Zeaxanthin epoxidase

chloroplastic |

5′-GGACAGTACAGAGGTCCAATTC-3′ |

55.0 |

333.0 |

[24] |

| ABA2-R |

5′-TCCTCAGCAACCTCCAAATC-3′ |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| AOG-F |

Abscisate beta-

glucosyltransferase |

5′-GGTGCCCACCCTCTTATTATC-3′ |

54.0 |

277.0 |

[24] |

| AOG-R |

5′-AAGGTGAAGGAGGAGGAGAA-3′ |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| GMMT-F |

Glucomannan

mannosyltransferase |

5′-GTCCAGATCCCCATGTTCAACGAG-3′ |

60.0 |

107.0 |

[5] |

| GMMT-R |

5′-CCAACAGAATTGAGAAGGGTGAT-3′ |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Act-F |

Actin |

5′-AGCCGTCGATGATTGGGATG-3′ |

60.0 |

116.0 |

[5] |

| Act-R |

5′-CCACTGAGCACAATGTTGCC-3′ |

4.4. RT-qPCR Quantitative Analysis

The RT-qPCR was conducted using the Power SYBR

® Green RNA-to-CT™ 1-Step Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, USA) on a Step One™ Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, with a reaction volume of 10 µL. A negative control, containing DEPC water, was included. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: reverse transcription at 48 °C for 30 min, Taq polymerase activation at 95 °C for 10 min, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, and annealing at 60 °C for 1 min. This cycle was repeated 40 times, followed by a melting curve analysis: 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 95 °C for 15 s. Relative expression levels were determined using the Quantitation–Comparative CT (

ΔΔCT) method [

25].

After RT-qPCR, melting curves were generated to verify the specificity of the amplification. Additionally, a horizontal electrophoresis was performed on a 1.2% agarose gel as a complementary test. All assays were carried out in triplicate.

4.5. Biosynthesis of Mannose-Rich Polysaccharides

The biosynthesis of mannose-rich polysaccharides was associated to the mannose content. Thus, the extraction as well as the carbohydrate composition of mannose-rich polysaccharides was conducted according to the described methodology by Comas-Serra

, et al. [

9]. The alcohol residue insoluble was obtained from freeze-dried

A. vera gel which was then subjected to water extraction and the water-soluble material was freeze-dried and subjected to hydrolysis. The released mannose was derivatized to their alditol acetate and quantified by GC [

9].

4.6. Statistical Analysis

All results were statistically analyzed by ANOVA. The soil moisture and NaCl concentration were taken as factors, and a General Linear Model was utilized to conduct ANOVA with a statistical significance level of α < 0.05. The post-hoc analysis was performed using the lower significant difference (LSD) test. All statistical analyses were performed in MINITAB® software.

5. Conclusions

The study highlights that Aloe vera activates a hormonal cascade under saline-water stress that enhances the biosynthesis and signaling of ABA through key genes like ABA2 and AOG. These genes regulate the balance between active and conjugated ABA, enabling the plant to adjust stomatal behavior and cellular stress defenses. Concurrently, the gene GMMT, encoding the enzyme responsible for acemannan biosynthesis, is upregulated in response to stress, particularly under moderate salinity and water deficit, reinforcing cell wall structure and water retention through increased production and acetylation of mannose-rich polysaccharides. At the biochemical level, these polysaccharides, along with stable pectic matrices, enhance the plant’s capacity to retain water and maintain cellular integrity under extreme conditions. While ABA2 expression peaks under drought stress, AOG expression is downregulated under high stress intensity, suggesting a metabolic shift toward ABA preservation and survival prioritization. Altogether, the findings support a model in which A. vera’s resilience is rooted in its ability to integrate hormonal, genetic, and structural responses, allowing it to thrive in increasingly hostile environments. Understanding and leveraging these adaptive mechanisms offers promising avenues for the development of climate-resilient crops through biotechnological or breeding strategies. There is no doubt that climate change is intensifying abiotic stressors such as drought and salinity, posing serious threats to global agriculture and ecosystem resilience. In this context, A. vera emerges as a resilient model species, displaying a complex and highly coordinated response to environmental adversity. This response involves morphological adaptations, physiological regulation, and a robust molecular network driven primarily by the abscisic acid (ABA) pathway.

Supplementary Materials

Not applicable.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.Q.-R, A.P.-S. and R.M.-F.; methodology, M.M.-I. and J.J.Q.-R, J.S.-M. and R.M.-F.; software, M.M.-I.; validation, M.M.-I., J.J.Q.-R, J.S.-M. and R.M.-F.; formal analysis, M.M.-I., J.J.Q.-R, J.S.-M. and R.M.-F.; investigation, M.M.-I., J.J.Q.-R, A.P.-S. and R.M.-F.; resources, J.J.Q.-R, A.P.-S., J.S.-M. and R.M.-F.; data curation, M.M.-I.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.-I.; writing—review and editing, M.M.-I., J.J.Q.-R and R.M.-F.; visualization, M.M.-I.; supervision, J.J.Q.-R, A.P.-S. and R.M.-F.; project administration, J.J.Q.-R, A.P.-S. and R.M.-F.; funding acquisition, J.J.Q.-R, A.P.-S. and R.M.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors María Mota-Ituarte ad Aurelio Pedroza-Sandoval would like to thank to the Dirección General de Investigación from the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo for the financial support by the Institutional Strategic Project with Code 20125-C-60. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the language and readability of some paragraphs from manuscript. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Saharan, B.S.; Brar, B.; Duhan, J.S.; Kumar, R.; Marwaha, S.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T. Molecular and physiological mechanisms to mitigate abiotic stress conditions in plants. Life 2022, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Sifuentes-Rodríguez, N.S.; Trejo-Calzada, R.; Zegbe-Dominguez, J.A.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Samaniego-Gaxiola, J.A. Leaf production and gel quality of Aloe vera (l.) burm. F. Under irrigation regimens in northern mexico. Journal of the Professional Association for Cactus Development 2022, 24, 139–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Ituarte, M.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Trejo-Calzada, R.; Zegbe, J.A.; Quezada-Rivera, J.J. Water deficit and salinity modify some morphometric, physiological, and productive attributes of Aloe vera (l.). Bot. Sci. 2023, 101, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatorre-Castillo, J.P.; Delatorre-Herrera, J.; Lay, K.S.; Arenas-Charlín, J.; Sepúlveda-Soto, I.; Cardemil, L.; Ostria-Gallardo, E. Preconditioning to water deficit helps Aloe vera to overcome long-term drought during the driest season of atacama desert. Plants 2022, 11, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, P.; Salinas, C.; Contreras, R.A.; Zuñiga, G.E.; Dupree, P.; Cardemil, L. Water deficit and abscisic acid treatments increase the expression of a glucomannan mannosyltransferase gene (gmmt) in Aloe vera burm. F. Phytochem. 2019, 159, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salinas, C.; Handford, M.; Pauly, M.; Dupree, P.; Cardemil, L. Structural modifications of fructans in aloe barbadensis miller (Aloe vera) grown under water stress. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Medina-Torres, L.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Rodríguez-González, V.M.; Eim, V.; Femenia, A. Influence of water deficit on the main polysaccharides and the rheological properties of Aloe vera (aloe barbadensis miller) mucilage. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, M.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Mota-Ituarte, M.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Comas-Serra, F.; Quezada-Rivera, J.J.; Sáenz-Esqueda, Á.; Femenia, A. Joint water and salinity stresses increase the bioactive compounds of Aloe vera (aloe barbadensis miller) gel enhancing its related functional properties. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 285, 108374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Serra, F.; Miró, J.L.; Umaña, M.M.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Femenia, A.; Mota-Ituarte, M.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A. Role of acemannan and pectic polysaccharides in saline-water stress tolerance of Aloe vera (aloe barbadensis miller) plant. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatorre-Herrera, J.; Delfino, I.; Salinas, C.; Silva, H.; Cardemil, L. Irrigation restriction effects on water use efficiency and osmotic adjustment in Aloe vera plants (aloe barbadensis miller). Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, T.S.; Singh, K.; Singh, B. Screening of sodicity tolerance in Aloe vera: An industrial crop for utilization of sodic lands. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Mahajan, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, V.K. The genome sequence of Aloe vera reveals adaptive evolution of drought tolerance mechanisms. iScience 2021, 24, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Singh, A. Abscisic acid, a principal regulator of plant abiotic stress responses. In Plant signaling molecules, Khan, M.I.R., Reddy, P.S., Ferrante, A., Khan, N.A., Eds. Woodhead Publishing: 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816451-8.00021-6pp. 341–353.

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Tiozon, R.N.; Fernie, A.R.; Sreenivasulu, N. Abscisic acid and its role in the modulation of plant growth, development, and yield stability. Trends in Plant Science 2022, 27, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.-J.; Nakajima, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamaguchi, I. Cloning and characterization of the abscisic acid-specific glucosyltransferase gene from adzuki bean seedlings. Plant Physiology 2002, 129, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, F.; Singh, A.; Kamal, A. Osmoprotective role of sugar in mitigating abiotic stress in plants. Protective chemical agents in the amelioration of plant abiotic stress. 10.1002/9781119552154.ch3pp. 53-70.

- Rodríguez-García, R.; Rodríguez, D.J.d.; Gil-Marín, J.A.; Angulo-Sánchez, J.L.; Lira-Saldivar, R.H. Growth, stomatal resistance, and transpiration of Aloe vera under different soil water potentials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2007, 25, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebamiji, Y.O.; Adigun, B.A.; Shamsudin, N.A.A.; Ikmal, A.M.; Salisu, M.A.; Malike, F.A.; Lateef, A.A. Recent advancements in mitigating abiotic stresses in crops. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, R.; Rehman, R.U.; Siddiqui, M.W.; Liu, H.; Seth, C.S. Phytohormones: Heart of plants’ signaling network under biotic, abiotic, and climate change stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochemi. 2025, 223, 109839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Abscisic-acid-dependent basic leucine zipper (bzip) transcription factors in plant abiotic stress. Protoplasma 2017, 254, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.-H.; Chiang, V.L. The cellulose synthase gene superfamily and biochemical functions of xylem-specific cellulose synthase-like genes in populus trichocarpa Plant Physiology 2006, 142, 1233–1245. [CrossRef]

- Felix, K.; Su, J.; Lu, R.; Zhao, G.; Cui, W.; Wang, R.; Mu, H.; Cui, J.; Shen, W. Hydrogen-induced tolerance against osmotic stress in alfalfa seedlings involves aba signaling. Plant and Soil 2019, 445, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.M.; Thu, S.W.; Balasubramanian, V.K.; Cobos, C.J.; Disasa, T.; Mendu, V. Identification, characterization, and expression analysis of cell wall related genes in sorghum bicolor (l.) moench, a food, fodder, and biofuel crop. Fron. Plant Sci. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, M. Expresión génica como indicador de viviparidad en nogal pecanero (carya illinoinensis [wangenh.] k. Koch). Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, 2023.

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time pcr data by the comparative ct method. Nature Protocols 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).