1. Introduction

The modern university operates in an environment characterized by profound transformations. Globalization, digitalization, and, in particular, the emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) have significantly altered teaching and learning processes (González-Campos et al., 2024; Yánez-Jara et al., 2019). In this context, students are required not only to develop technical and disciplinary competencies but also to strengthen emotional and adaptive abilities that enable them to face uncertainty and take advantage of the opportunities provided by emerging technologies (Paik et al., 2025; Salas et al., 2022).

In this regard, artificial intelligence emerges as a versatile resource for university students, applicable in academic, informational, and emotional domains. As an academic tool, AI optimizes learning processes by facilitating content comprehension, skill practice, and personalized teaching tailored to individual needs. In its informational function, it provides fast and organized access to large volumes of data, supporting research, analysis, and synthesis of relevant information for tasks and projects. Moreover, AI can play an emotional support role by assisting with time management, activity organization, and, in some cases, offering guidance or feedback that contributes to self-regulation and stress management in the university setting. This broad potential of AI underscores the importance of studying how students integrate these tools into their academic and daily experiences, and how personal competencies may influence their effective use (Today & Moya, 2024). Among these competencies, emotional intelligence stands out as a fundamental element in the educational context (Bartz et al., 2023; Chacón-Chamorro et al., 2024; Rehman et al., 2021).

The concept of emotional intelligence was proposed decades ago by Mayer and Salovey (1997), who defined it as a construct comprising various skills oriented toward perceiving, valuing, and adequately expressing emotions, as well as generating feelings that facilitate thought, understanding emotional states, and effectively regulating them. This contributes to better adaptation to one’s environment (Goleman, 1995; Mayer et al., 2016; Morales & López-Zafra, 2009), which is essential in academia. Its development benefits not only the student’s personal well-being but also the creation of more effective collaborative environments, enhancing collective learning and strengthening the university community.

Although various instruments exist to evaluate emotional intelligence (EI), one of the most widely used is the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS), a self-report questionnaire developed by Salovey et al. (1995). This instrument identifies three main dimensions of EI: a) Attention to emotions, b) Emotional clarity, and c) Repair of negative emotional states. Attention refers to the ability to perceive and reflect on one’s emotions; clarity focuses on the understanding of personal emotional states; and repair refers to the regulation and management of negative feelings.

In general, the literature has shown that individuals with higher levels of EI, as measured by the TMMS, report fewer physical symptoms, lower social anxiety and depression, better self-esteem, higher satisfaction in interpersonal relationships, and more frequent use of active coping strategies to solve problems (Buenrostro et al., 2012; Martins, Ramalho & Morin,2010; Sánchez-Camacho & Grane, 2022). However, the relevance of each EI dimension varies depending on the construct with which it is related (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005; Fragoso-Luzuriaga, 2015). For instance, several studies using the TMMS have found that the repair ability is negatively associated with depression, alexithymia, irritability, and somatic symptoms, while attention shows a positive relationship with these variables (Buenrostro et al., 2012; Páez Cala & Castaño Castrillón, 2015; Martins et al., 2010; Sánchez-Camacho & Grane, 2022).

In the university context, studies using the TMMS have shown that the dimensions of clarity and repair are linked to higher empathy levels, greater life satisfaction, and better quality social relationships (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005; Fragoso-Luzuriaga, 2015). Likewise, students with higher EI levels demonstrate better stress management, stronger intrinsic motivation, and improved interpersonal relationships, all of which positively influence academic performance (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005; MacCann et al., 2020). Moreover, EI enables greater flexibility in facing the demands of a university environment marked by complexity, competitiveness, and constant technological innovation.

Translating the EI construct into the university setting, where the rapid emergence of AI is transforming teaching, learning, and social interaction practices, there arises a need to deepen our understanding of how students employ these technological tools.

In this sense, various authors highlight that EI plays a crucial role in motivation and academic achievement, and its relationship with AI in emotional evaluation is an area of ongoing research (Cejudo & López, 2017; López De La Cruz & Baldeón-Canchaya, 2024; Today & Moya, 2024). Thus, considering the diverse applications of AI, it becomes relevant to explore whether different levels of emotional intelligence influence its use as a resource for educational, informational, or emotional support in the university environment.

The review of existing literature shows that there are still few studies explicitly addressing the relationship between emotional intelligence (EI) and the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in educational contexts, particularly in higher education (Cevallos et al., 2024; López de la Cruz & Baldeón-Canchaya, 2024; Today & Moya, 2024). More specifically, no publications have been found analyzing how EI dimensions may condition the frequency, motivation, or purpose of students’ use of AI tools for academic, informational, or emotional goals. In light of this gap, fundamental questions arise: Can EI influence the degree of AI use? And if so, are the reasons for use modulated by differences in students’ emotional profiles? Likewise, if EI is structured around three dimensions—attention, clarity, and emotional regulation (Salovey et al., 1995)—it is worth asking whether these dimensions guide the motives behind university students’ use of AI, and to what extent each conditions its use as a resource for academic or personal support.

The analysis of EI dimensions in relation to the participation and motives for AI use is particularly relevant, as these socio-emotional competencies shape how individuals perceive, value, and adapt to technological innovations (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005; Mayer et al., 2016). Indeed, while self-awareness and self-regulation can determine perceived confidence and control in interactions with automated systems, motivation may guide one’s disposition toward learning and exploration of these tools, and social skills may facilitate collaborative and communicative use of AI in academic environments (MacCann et al., 2020; Martins et al., 2010). Understanding this relationship not only identifies facilitating factors or barriers to AI adoption but also helps develop pedagogical strategies that foster conscious, ethical, and human-centered use.

In this sense, the present research fits within an emerging field that places the relationship between emotional intelligence and AI in higher education as a subject of growing scientific and pedagogical interest (Cejudo & López, 2017; Rehman et al., 2021). Therefore, the general objective is to analyze the relationship between university students’ EI profiles and their use of AI in education, considering its impact on academic, informational, and emotional domains.

From this general objective, the following specific objectives are derived: (1) to identify and describe university students’ EI profiles based on the relevance of its dimensions; (2) to determine whether these profiles are related to AI use as a resource for educational support and learning enhancement.

From these objectives, several research hypotheses emerge, among them:

H1. EI profiles, configured from the combination of intrapersonal and interpersonal competencies, will show significant differences in how students integrate AI into their academic and daily experiences. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that EI has been consolidated as a key element in promoting adaptation, personal well-being, and the quality of interactions in educational environments (Goleman, 1995; Mayer & Salovey, 1997).

H2. Emotional intelligence (EI) profiles influence the use of artificial intelligence (AI) in higher education differently, both for educational, informational, and emotional support. This hypothesis is based on the premise that EI profiles, by influencing motivation, self-regulation, and adaptation to new technologies, condition how students use AI as a resource for educational support and learning enhancement (Morales & López-Zafra, 2009).

2. Method

2.1. Participants

The sample consisted of 352 students from the University of Alicante (UA), aged between 18 and 28 years, with a mean age of 21.4 years (SD = 2.3). Of the total, 178 were women (50.6%) and 174 men (49.4%), distributed across various fields of study: Engineering (n = 85), Education (n = 69), Business Administration (n = 61), Health Sciences (n = 70), and Social Sciences (n = 67).

To assess the homogeneity of the gender distribution across academic fields, a Chi-square test of homogeneity was applied. The results indicated no significant differences between men and women according to degree program (χ2 = 0.279, df = 4, p = 0.991). The expected values under the assumption of uniform distribution were approximately 43 women and 42 men in Engineering, 34 and 35 in Education, 31 and 30 in Business Administration, 35 and 35 in Health Sciences, and 34 and 33 in Social Sciences, thus confirming the homogeneity of the sample.

2.2. Instruments

To measure perceived emotional intelligence, a self-report instrument was used: the Trait Meta-Mood Scale-24 (TMMS-24) developed by Fernández-Berrocal, Extremera, and Ramos (2005). This scale is a shortened version adapted into Spanish from the original Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS) by Salovey et al. (1995), derived from the TMMS-48.

The TMMS-24 consists of 24 items, assessed using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree), and is organized into three dimensions with 8 items each: Attention to feelings, Emotional clarity, and Repair of negative emotions.

This instrument was chosen for its ease of application and its validation in both young and adult populations (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004). The Spanish version of the scale has demonstrated internal consistency indices above 0.80 (Attention, α = .84; Clarity, α = .82; Repair, α = .81). In the present study, reliability was α = .83 for Attention, α = .81 for Emotional Clarity, and α = .80 for Emotional Repair.

To evaluate university students’ use of artificial intelligence (AI), an ad hoc questionnaire was developed focusing on three dimensions: educational support, informational support, and emotional support. The instrument consisted of 12 items formulated as statements, using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). The first dimension, educational support, included four items that explored students’ perceptions of AI usefulness for understanding content, organizing and planning study, generating ideas, solving academic problems, and fostering autonomous learning. The second dimension, informational support, also with four items, assessed AI’s ability to provide reliable information, facilitate rapid access to complex concepts, support academic decision-making, and complement traditional study materials. The third dimension, emotional support, likewise comprised four items, examining how AI can reduce anxiety, provide guidance in academic difficulties, offer a sense of companionship during study, and increase motivation and concentration on academic goals.

Additionally, the questionnaire included an optional open-ended comments section to collect further experiences regarding students’ interaction with AI.

Regarding validity, the questionnaire was designed based on an exhaustive review of literature on AI tools in educational contexts and on academic and emotional support in university students. Item relevance and clarity were evaluated by a panel of education and psychology experts, ensuring content validity. A subsequent exploratory factor analysis (EFA) confirmed that the proposed three-factor structure aligned with the theoretical dimensions, explaining approximately 70% of total variance: 26% for educational support, 24% for informational support, and 20% for emotional support.

To ensure construct validity, data adequacy tests were conducted prior to the EFA. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index yielded a value of 0.84, indicating sampling adequacy for factor extraction. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (χ2(66) = 512.37, p < 0.001), confirming sufficient correlations among items to justify factor analysis.

The EFA was performed using the factor extraction method with varimax rotation, identifying a three-factor structure consistent with the theoretical dimensions: educational, informational, and emotional support. The results showed that the first factor, educational support, explained 28% of the variance; the second, informational support, 24%; and the third, emotional support, 18%, accounting for a total of 70% explained variance. Factor loadings ranged between 0.45 and 0.82, indicating that all items adequately associated with their respective factors.

The reliability of the instrument was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding satisfactory values for each dimension: α = 0.85 for educational support, α = 0.82 for informational support, and α = 0.80 for emotional support. The overall reliability coefficient was α = 0.87, indicating adequate internal consistency.

2.3. Procedure

Data collection was carried out through the administration of a questionnaire to students from different degree programs at the University of Alicante. First, authorization was requested from the Vice-Rectorate of Students to disseminate the study and invite voluntary participation. Subsequently, an online announcement was posted on the university’s virtual campus, outlining the study objectives and inviting students to participate voluntarily.

The questionnaire was hosted on a web platform, and students accessed it through the link provided in the announcement. Completion of the questionnaire took approximately 10 minutes. Before answering, informed consent was requested, ensuring participants understood the study’s objectives, procedures, data confidentiality, and the voluntary nature of their participation, in accordance with ethical standards for research with university populations.

2.4. Data Analysis

To identify students’ emotional intelligence (EI) profiles, cluster analysis was employed, combining hierarchical and non-hierarchical techniques. First, an agglomerative hierarchical method was applied using Euclidean distance and average linkage criteria. This phase allowed exploration of the underlying data structure and determination of the optimal number of student groups according to their scores on the three EI dimensions assessed with the TMMS-24: attention to feelings, emotional clarity, and repair of negative emotions.

Subsequently, the k-means method was implemented, using the number of clusters suggested by the hierarchical analysis. This technique enabled precise assignment of each participant to a group, optimizing within-cluster homogeneity and ensuring clear separation between EI profiles. Means and standard deviations of each dimension within each group were calculated, facilitating the interpretation of profiles as high and balanced EI, regulatory EI, or EI with a deficit in emotional repair.

Next, to assess whether different EI profiles influenced perceived use of AI in its three dimensions (educational, informational, and emotional support), analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) were conducted, considering gender and age as covariates to control for their possible effects on differences among profiles. Post-hoc comparisons were performed using the Bonferroni method to detect significant differences between clusters, and Cohen’s d effect size was calculated to quantify the magnitude of differences.

Values of F, p, and partial η2 were reported to assess statistical significance and global effect size, as well as means and standard deviations for each cluster across the three AI use dimensions. Significance was set at p < .05. This approach allowed for the determination of how different emotional intelligence profiles relate to the perception and use of AI in university contexts, providing evidence on the influence of emotional competencies in the adoption of educational and emotional support technologies.

3. Results

3.1. Emotional Intelligence Profiles

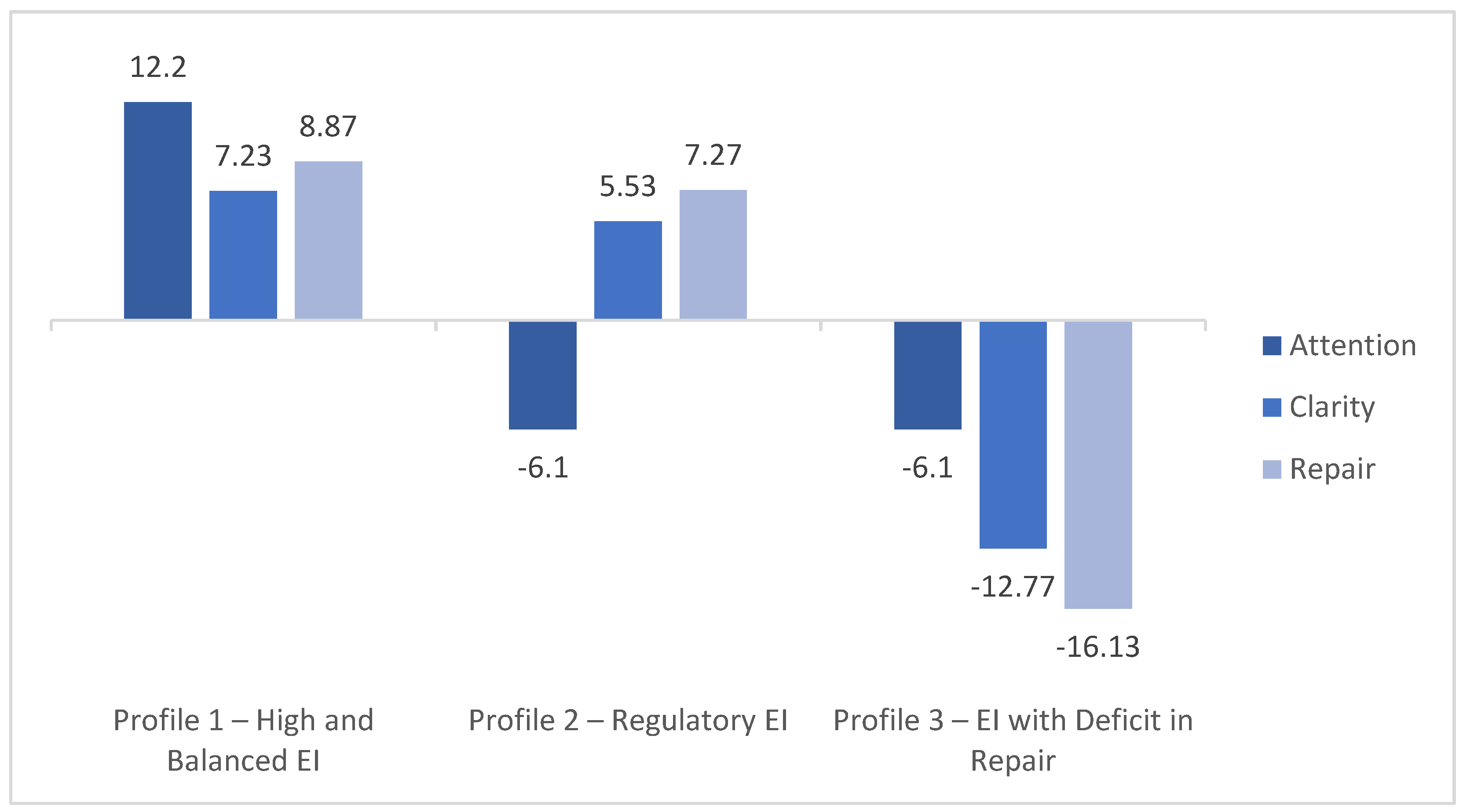

The cluster analysis based on TMMS-24 dimensions identified three EI profiles among the 352 university students:

The Profile 1 – High and balanced EI (40%, n = 141): High scores in Attention (77.5%), Clarity (80%), and Repair (77.5%). This group demonstrates comprehensive emotional development, with the ability to perceive, understand, and manage emotions effectively. The Profile 2 – Regulatory EI (35%, n = 123): Moderate Attention (50%) but high Clarity (77.5%) and Repair (75%). Students in this profile understand and regulate their emotions effectively without focusing excessively on each emotion, supporting decision-making and resilience to academic stress. The Profile 3 – EI with deficit in Repair (25%, n = 88): Moderate Attention (50%) and Clarity (50%), but low Repair (40%). This pattern suggests that students partially perceive and understand their emotions but struggle to regulate them adequately, which may affect stress management and academic motivation.

Figure 1.

Emotional Intelligence Profiles.

Figure 1.

Emotional Intelligence Profiles.

3.2. Use of AI According to EI Profiles

The results showed significant differences in perceived AI use across the three emotional intelligence (EI) profiles.

Regarding educational support, students with a high and balanced emotional intelligence profile (Profile 1) reported the highest mean score (M = 4.20, SD = 0.48), followed by those with regulatory emotional intelligence (Profile 2) (M = 3.90, SD = 0.52), and finally, students with an emotional repair deficit (Profile 3) (M = 3.50, SD = 0.55). ANOVA analysis revealed significant differences between profiles, F(2, 349) = 40.10, p < .001, with a large effect size (partial η2 = .18), indicating that students with higher emotional development perceive artificial intelligence as a more useful tool for organizing, planning, and enhancing academic learning.

A similar pattern was observed for informational support. Profile 1 students had a mean of 4.10 (SD = 0.50), Profile 2 students 3.85 (SD = 0.55), and Profile 3 students 3.45 (SD = 0.54). ANOVA showed significant differences, F(2, 349) = 36.50, p < .001, with a moderate-to-high effect size (partial η2 = .17). This suggests that students with higher emotional intelligence use AI more effectively for searching, organizing, and understanding academic information.

Regarding emotional support, Profile 1 students scored a mean of 3.80 (SD = 0.60), Profile 2 students 3.60 (SD = 0.62), and Profile 3 students 2.90 (SD = 0.65). Differences were significant, F(2, 349) = 35.20, p < .001, with a considerable effect size (partial η2 = .16), indicating that emotional regulation directly influences the perception of AI as a resource for stress management, self-regulation, and academic motivation.

Post hoc analyses using the Bonferroni correction confirmed that all three emotional intelligence profiles differed significantly across all dimensions of AI use. In terms of educational support, Profile 1 scored significantly higher than both Profile 2 (p < .01) and Profile 3 (p < .001), while Profile 2 also outperformed Profile 3 (p < .01). A similar pattern emerged for informational support, with Profile 1 achieving higher scores than Profile 2 (p < .05) and Profile 3 (p < .001), and Profile 2 surpassing Profile 3 (p < .01). Regarding emotional support, Profile 1 again scored above Profile 2 (p < .05) and Profile 3 (p < .001), while Profile 2 maintained a significant advantage over Profile 3 (p < .01). The effect sizes were moderate to large (partial η2 = .16–.18), underscoring the important role of emotional intelligence in the adoption and effective use of AI in academic contexts.

Table 1.

AI Use According to EI Profiles.

Table 1.

AI Use According to EI Profiles.

| AI Dimension |

Profile 1: High EI |

Profile 2: Regulatory EI |

Profile 3: Deficit in Repair |

F(2,349) |

p |

η2 partial |

| Educational support |

4.20 (0.48) |

3.90 (0.52) |

3.50 (0.55) |

40.10 |

< .001 |

.18 |

| Informational support |

4.10 (0.50) |

3.85 (0.55) |

3.45 (0.54) |

36.50 |

< .001 |

.17 |

| Emotional support |

3.80 (0.60) |

3.60 (0.62) |

2.90 (0.65) |

35.20 |

< .001 |

.16 |

4. Discussion

Emotional intelligence (EI) has been established in the literature as a key factor for academic performance, social adaptation, and psychological well-being of university students (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005; MacCann et al., 2020; Martins et al., 2010). In this context, the present study aimed to identify EI profiles in a sample of 352 university students and examine the relationship between these profiles and perceived use of artificial intelligence (AI) across three key dimensions: educational support, informational support, and emotional support.

The results indicate that EI profiles differ not only in their dimensions of attention, clarity, and emotional repair (Salovey et al., 1995) but also significantly modulate the perception and utilization of AI. This provides empirical evidence supporting the interaction between emotional competencies and technological tools in higher education (López de la Cruz & Baldeón-Canchaya, 2024; Today & Moya, 2024).

Three differentiated profiles were identified via cluster analysis: Profile 1 (High and Balanced EI), Profile 2 (Regulatory EI), and Profile 3 (Deficit in Emotional Repair). These findings align with previous research using the TMMS-24 to assess EI in university and adolescent populations (González et al., 2021; Guerra-Bustamante et al., 2019; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004), confirming the instrument’s utility in distinguishing functional student groups according to emotional competencies. The Profile 1, representing ~40% of the sample, reflects comprehensive emotional development with the capacity to perceive, understand, and regulate emotions effectively. This configuration supports resilience to academic stress and motivation for autonomous learning, consistent with studies highlighting EI as a predictor of academic success (Goleman, 1995; Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005). The Profile 2, characterized by moderate emotional attention but high clarity and repair, demonstrates that emotional regulation can compensate for lower attention to affective states, facilitating decision-making and management of complex academic situations (Mayer et al., 2004). This pattern aligns with findings emphasizing the role of regulation in academic resilience and autonomous learning strategies (Petrides et al., 2004; Salovey & Mayer, 1990). Finally, the Profile 3, defined by a deficit in emotional repair, shows that difficulties in regulation limit the ability to manage stress and leverage technological support resources. This finding is consistent with studies linking low repair levels with higher anxiety and lower academic performance (Extremera & Berrocal, 2005).

Regarding the relationship between EI profiles and AI use, results for the second objective showed statistically significant differences across all three dimensions: educational, informational, and emotional support. Students in Profile 1 reported the highest levels in all dimensions, indicating that comprehensive emotional development favors both perception of technological resources and their strategic use (MacCann et al., 2020). Conversely, students in Profile 3 scored lowest, particularly in emotional support, suggesting that low regulation limits not only AI use for learning but also its potential as a socio-emotional tool (Extremera & Berrocal, 2005).

Post hoc analyses confirmed that differences among profiles were significant across all AI dimensions, with moderate to large effect sizes. In educational support, each profile differed significantly from the others, whereas in informational and emotional support, Profiles 1 and 2 clearly differed from Profile 3. This pattern confirms that EI influences not only academic performance but also the adoption and strategic use of emerging educational technologies (Ocampo et al., 2024).

From a practical perspective, findings suggest that emotional training programs can significantly improve emotional regulation, especially in students with deficits in repair, enhancing well-being and optimizing AI use as an educational and socio-emotional tool (López-Bustamante & Vargas-D’Uniam, 2025). Additionally, technology platform design should incorporate adaptive feedback mechanisms and self-regulation resources to support students with lower emotional competence (López de la Cruz & Baldeón-Canchaya, 2024).

However, results should be interpreted cautiously due to certain limitations. The sample was restricted to a single university, limiting generalizability. Moreover, self-report measures may introduce social desirability bias, and the cross-sectional design prevents establishing definitive causal relationships (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004).

These limitations open avenues for future research, such as longitudinal studies examining AI use over time according to EI profiles or incorporating objective measures of technological interaction, such as platform usage logs. Likewise, it would be valuable to design interventions focused on strengthening emotional repair and evaluate their impact on AI perception and utilization in university contexts.

5. Conclusion

the present study’s findings indicate that emotional intelligence profiles are a determining factor in the perception and use of AI in higher education. Students with high clarity and emotional repair tend to use AI more strategically and effectively, whereas those with regulatory deficits show significant limitations, particularly in socio-emotional use. These results highlight the need to integrate emotional competence development into university education and technology platform design as a means to optimize learning, well-being, and adaptation in an increasingly digital educational context.

References

- Bartz, E.; Bartz-Beielstein, T.; Zaefferer, M.; Mersmann, O. Hyperparameter tuning for machine and deep learning with R: A practical guide (p. 323); Springer Nature, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Buenrostro-Guerrero, A. E.; Valadez-Sierra, M. D.; Soltero-Avelar, R.; Nava-Bustos; Zambrano-Guzmán, G.; García-García, R. A. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en adolescentes. Revista de Educación y Desarrollo 2012, 20(1), 29–37. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.cucs.udg.mx/revistas/edu_desarrollo/anteriores/20/020_Buenrostro.pdf.

- Cejudo, J.; López, M. Competencias emocionales y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 2017, 49(2), 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevallos, C. C.; Nogueira, D. M.; Matellán, E. L. D.; Balseca, D. N. N. Aprendizaje autónomo en entornos virtuales, su relación con las inteligencias artificial y emocional. Estudio bibliométrico. Universidad y Sociedad 2024, 16(1), 252–261. Available online: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2218-36202024000100252&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=en.

- Extremera Pacheco, N.; Fernández Berrocal, P. Inteligencia emocional percibida y diferencias individuales en el meta-conocimiento de los estados emocionales: una revisión de los estudios con el TMMS. Ansiedad y Estrés 2005, 11(2-3), 101–122. Available online: https://portaldelainvestigacion.uma.es/documentos/66294b39fa03b20738752ba1.

- Fragoso-Luzuriaga, R. Inteligencia emocional y competencias emocionales en educación superior, ¿un mismo concepto? Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior 2015, 6(16), 110–125. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=299138522006. [CrossRef]

- Goleman, D. Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ; Bantam Books, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- González -Campos, J.; López - Núñez, J.; Araya - Pérez, C. Educación superior e inteligencia artificial: desafíos para la universidad del siglo XXI. Aloma: Revista De Psicologia, Ciències De l’Educació I De l’Esport 2024, 42(1), 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, R.; Brenda, J.; Zalazar, M.; Medrano, L. Trait Meta-Mood Scale-24: estructura factorial, validez y confiabilidad en estudiantes universitarios argentinos. Bordón: Revista de pedagogía 2021, 73(3), 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Bustamante, J.; León-Del-Barco, B.; Yuste, R. Inteligencia emocional y bienestar psicológico en adolescentes. Revista de Psicología 2019, 37(2), 123–135. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6985489.

- López De La Cruz, J.; Baldeón Canchaya, M. Inteligencia artificial en la evaluación de la inteligencia emocional en estudiantes universitarios: un análisis actualizado. Revista de Innovación Empresarial 2024, 4(1), 35–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Bustamante, G.; Jessica Vargas-D’Uniam, C. Relación entre las competencias digitales y el compromiso académico en estudiantes de posgrado en modalidad virtual: una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Revista Complutense de Educación 2025, 36(2), 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, C.; Jiang, Y.; Brown, L. E.; Double, K. S.; Bucich, M.; Minbashian, A. Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 2020, 146(2), 150–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.; Ramalho, N.; Morin, E. A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Personality and Individual Differences 2010, 49(6), 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D.; Salovey, P. Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; What is emotional intelligence? In Emotional development and emotional intelligence: Educational implications; Basic Books, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J. D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D. R. The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emotion Review 2016, 8(4), 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, J.; López-Zafra, E. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico: estado actual de la cuestión. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología 2009, 41(1), 69–79. Available online: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=80511492005.

- Ocampo, M.; Ríos, C.; García, M.; Tapia, M. La inteligencia emocional en estudiantes en un escenario de post pandemia. Aula Virtual 2024, 5(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez Cala, M. L.; Castaño Castrillón, J. J. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Psicología desde el Caribe 2015, 32(2), 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paik, J. H.; Himelfarb, I.; Yoo, S. H.; Lee, J. T.; Ha, H. The Role of Students’ Reporting of Emotional Experiences in Mathematics Achievement: Results from an e-Learning Platform. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy 2025, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrides, K. V.; Pita, R.; Kokkinaki, F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. British Journal of Psychology 2004, 95(2), 273–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, R.; Tariq, S.; Tariq, S. Emotional intelligence and academic performance of students. Journal Of Pakistan Medical Association 2021, 71(12), 2777–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salas Román, N.; Alcaide Risoto, M.; Hue García, C. Mejora de las competencias socioemocionales en alumnos de educación infantil a través de la educación emocional. Revista Española de Pedagogía 2022, 80(283), 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J. D. Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality 1990, 9(3), 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J. D.; Goldman, S.; Turvey, C; Palfai, T. Pennebaker, J. W., Ed.; Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In Emotion, disclosure, and health; American Psychological Association, 1995; pp. 125–154. Available online: https://scholars.unh.edu/psych_facpub/425/.

- Sánchez-Camacho, R.; Grane, M. Instrumentos de Evaluación de Inteligencia Emocional en Educación Primaria: Una Revisión Sistemática. Journal of Psychology & Education/Revista de Psicología y Educación 2022, 17(1), 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Today, J.; Moya, L. La inteligencia artificial como método de apoyo académico para estudiantes universitarios. Boletín Científico Ideas y Voces 2024, 4(3), 352–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yánez-Jara, V. M.; Vega-Muñoz, A.; Araya-Castillo, L. A. Grupos estratégicos como área de investigación en educación superior. Revista Espacios 2019, 40(44), 11. Available online: https://www.revistaespacios.com/a19v40n44/19404411.html.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).