1. Introduction

The rapid advancement of AI technology has made its use in education a subject of significant academic and practical interest [

1]. As an innovative educational and learning tool, AI has become an important pillar of education [

2]. Against this backdrop, numerous studies have begun examining the influence of AI on students’ learning outcomes and cognitive levels. Existing literature shows that in higher education, students’ academic performance, motivation, and engagement may all be enhanced by the application of AI [

3]. Additionally, some research has shown that using AI may improve mental health by offering psychological support [

5] in addition to learning feedback [

4]. Nonetheless, the majority of previous studies on the combination of AI and education have been on either primary and secondary education or higher education institutions, with insufficient discussion on the vocational education. Vocational education plays a significant role in developing socially adept talent in China, and the academic and mental health challenges that students encounter are distinct [

6]. Due to the influence of traditional societal and historical perspectives, the social recognition of vocational education may not be as high as that of higher education [

7], which could exacerbate psychological stress among vocational education students. Additionally, influenced by the stratified education system, vocational education students generally have weaker academic foundations and insufficient learning confidence, potentially leading to greater academic anxiety [

8]. Therefore, the academic anxiety issues faced by vocational education students are being highly addressed.

AI, as an innovative and powerful learning tool [

9], may play a significant role in student learning within vocational education. Some studies have begun to explore the application of AI in vocational education, such as the introduction of intelligent training systems and virtual simulation platforms by some higher vocational colleges to assist in skill development [

10], and preliminary investigations into the role of AI in optimizing class teaching [

11]. However, overall, the application of AI in vocational education is still mostly limited to teaching tools, lacking systematic attention to students’ actual usage and its impact on class engagement and mental health (such as academic anxiety). Therefore, the first objective of this study is to explore how AI usage affects academic anxiety in vocational education students.

The conservation of resources (COR) theory offers a valuable lens to explore how AI usage influences academic anxiety in vocational education students [

12]. According to this theory, when faced with potential stress and challenges, individuals not only strive to prevent resource loss but also acquire and utilise internal and external resources to increase resources for coping with stress [

12]. Students can obtain new learning resources and tools through the instant feedback [

13], diversified learning content, and interactive experiences provided by AI [

14]. The input of these external resources helps stimulate students’ class engagement. The influence of AI usage on academic anxiety may be significantly mediated by class engagement. Therefore, this study’s second goal is to investigate how class engagement mediates the effect of AI usage on academic anxiety in students enrolled in vocational education..

In addition, perceived teacher support for AI usage is considered an important moderating factor. In educational settings, teachers not only organise class teaching but also guide students in adopting new technologies [

15]. Students’ perceptions of teachers’ encouragement, guidance, and support for AI usage directly affect their trust , enthusiasm , and ability to use AI tools [

16], this could mitigate the association between class participation and AI usage. Prior research has shown that when students feel more technical support and emotional encouragement from teachers, they are more willing to transform external resources into class engagement, which in turn stimulates higher levels of learning motivation and concentration [

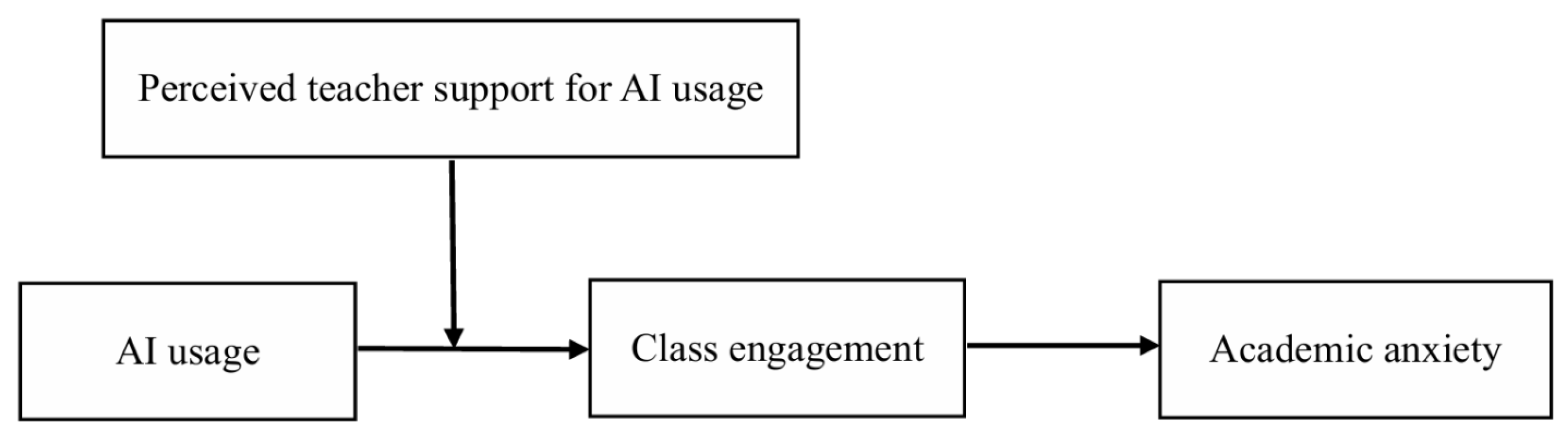

17]. Accordingly, the third objective of this study is to further examine the moderating role of perceived teacher support for AI usage in the relationship between AI usage and class engagement. The theoretical model is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The AI usage has complex effects on students’ psychology and behavior [

18,

19,

20], and its impact on academic anxiety among vocational education students may involve multiple equivalent pathways. While quantitative methods can objectively verify the causal relationships between variables, but struggle to account for other explanatory antecedent conditions, leading to overly rigid research logic. Thus, this research also seeks to elucidate the connection between academic anxiety and AI usage.Based on empirical research, we perform a configurational analysis of the antecedents that cause low academic anxiety using the fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) method.

This study has certain theoretical contributions. First, this study combines COR theory to investigate the connection between vocational education students’ AI usage and academic anxiety. Second, this study explores the precise processes via which academic anxiety is impacted by the usage of AI among students enrolled in vocational education, exposing the pathways that link the two. Third, this study explores the boundary conditions of perceived teacher support for AI usage and conducts a configurational analysis of the antecedents that trigger low academic anxiety. This study extends the application of COR theory within vocational education, offering novel theoretical insights and actionable guidance for improving both instructional and administrative practices.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample and Collection

This study adopted random sampling and distributed electronic questionnaires via the “QuestionStar” platform to students from vocational colleges in Sichuan, Chongqing, Henan, and Shanghai. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed of the research purpose, the voluntary nature of participation, and that all data would be used solely for academic purposes with strict confidentiality. Those unwilling to participate could exit the survey at any time.

To ensure relevance, a screening question—“Do you utilize AI in your daily learning and life?”—was included at the outset; respondents who answered “no” were excluded. As an incentive, participants received a 4-yuan red envelope after manual review. To reduce common method bias, data were collected in three waves at two-week intervals. Demographic variables and AI usage were collected at TIME 1 (T1); perceived teacher support for AI usage and class engagement at TIME 2 (T2); and academic anxiety at TIME 3 (T3). Questionnaires were matched using the last four digits of participants’ phone numbers, resulting in 564 matched cases. After removing responses with patterned answers (e.g., selecting the same option 10 consecutive times), 511 valid questionnaires remained, yielding a response rate of 90.6%.

Among the 511 questionnaires, 54.6% were from males and 45.4% from females. First-year students accounted for 16.2%, second-year students for 52.1%, and third-year students for 31.7%. The average age was 20.4 years. Other demographic information is detailed in

Table 1.

3.2. Measurement

The measurement tools used in this study were selected based on the following criteria: (1) They were sourced from internationally recognised, authoritative journals and widely accepted. (2) Validated across multiple cultural contexts, including China, demonstrating good reliability and validity. Additionally, to enhance the accuracy and adaptability of the measurement items, this study employed the widely used “back-translation method” to repeatedly revise and refine the wording of the original scale, ultimately developing a 5-point Likert-scale questionnaire incorporating core variables. Scores range from 1 to 5, indicating varying degrees of agreement, with 1 representing “completely disagree” and 5 representing “completely agree.”

AI usage. AI usage was assessed with a three-item scale from Pok et al. [

48], including items like “I use AI to fulfil most of my learning functions.” The scale demonstrated good reliability in this study, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.812.

Perceived teacher support for AI usage. This construct was measured using an eight-item scale developed by Patrick et al. [

49]. An example item is “I have a teacher I can count on when I need help with the usage of AI.” The Cronbach’s α in the current study was 0.950.

Class engagement. Class engagement was evaluated using a 12-item scale from Reeve and Lee [

32], with items such as “I try hard to do well in the class.” The scale showed high reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.927.

Academic anxiety. Academic anxiety was measured using a seven-item scale developed by Liu and Lu [

23]. A sample item reads, “To finish my homework makes me feel pressure.” The Cronbach’s α for this scale in this study was 0.915.

Control variables. Referring to existing research on academic anxiety among vocational education students [

50], this study controlled for gender, age, grade, and subject as variables to avoid interference with the conclusions of this study.

3.3. Data Analysis

This study utilised SPSS 27.0 software to examine descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations, and common method bias. AMOS 24.0 software was employed for confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modelling, path coefficient testing, and mediation and moderation effect testing. Among them, the mediation and moderation effect tests used the bias-corrected nonparametric percentile Bootstrap estimation method to perform 2,000 random repeated samples on the sample (n=511). The fsQCA 4.1 was used to perform fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis to test the configuration path of low academic anxiety.

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Implication

Firstly, AI technology has been highly touted in the field of education due to its powerful functions [

52]. However, existing studies have mostly focused on the promotional role of AI in teaching effectiveness, student academic performance, creativity, and innovative behavior [

53], while the discussion of the mechanism of AI’s role in student mental health, especially academic anxiety, remains relatively weak. This study systematically examined the impact of AI usage on academic anxiety among vocational education students, expanding the research on educational technology in the field of mental health and providing a new perspective for interdisciplinary research on AI and educational psychology. In addition, using vocational education students as a sample, we further enriched the research landscape of AI technology in the field of vocational education, responding to recent calls for attention to the special characteristics of vocational education students’ learning and psychological adaptation.

Secondly, we explored the mediating role of class engagement in the impact of AI usage on academic anxiety among vocational education students. Currently, vocational education students generally face multiple pressures, such as weak learning foundations and insufficient learning confidence [

8]. The class has become the core arena for shaping their skills and building their career confidence. A high level of class engagement not only affects learning outcomes but also directly affects their psychological adaptation and future career development. Our research shows that with the increasing integration of AI into vocational education, the use of AI can provide rich external resources such as personalised tutoring, instant feedback, and simulated vocational teaching [

15], shifting class engagement from traditional passive listening to active exploration and in-depth interaction [

54]. This study verifies the important bridging role of class engagement between AI usage and academic anxiety, enriching the understanding of educational psychological mechanisms in a digital learning environment.

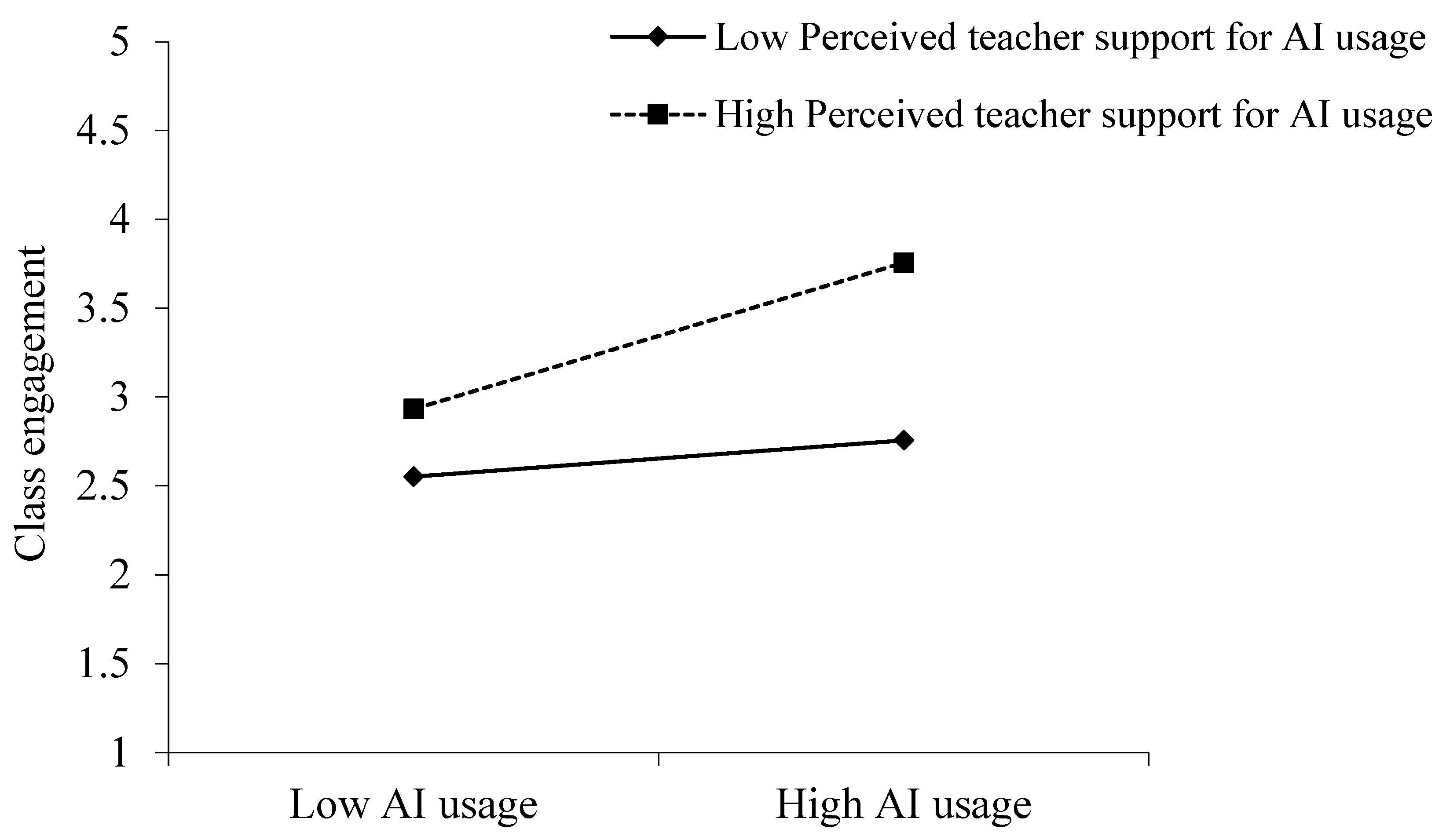

Thirdly, this study expands on related research on teacher support in the context of educational technology by revealing the moderating effect of perceived teacher support for AI usage. Our study validates that teacher support, as an important external resource, can influence students’ AI usage positivity and ability by encouraging, supporting, and guiding students in their use of AI [

16], providing a positive boost for students to transform AI usage resources into learning benefits [

17]. This finding highlights the critical role of teachers as “AI learning facilitators” and confirms the key role of external support factors in the effectiveness of educational technology [

40].

Finally, this study used the fsQCA method to reveal the multiple conditions that trigger low academic anxiety, enriching the understanding of the complexity of the causes of academic anxiety among vocational education students. The results show that low academic anxiety can be achieved through three main paths: first, the combination of AI usage and perceived teacher support for AI usage; second, the combination of AI usage and class engagement; and third, the combination of perceived teacher support for AI usage and class engagement. This result demonstrates the importance of resource diversity, i.e., different types of resources (technical resources, contextual support, and classroom learning engagement) can work together in multiple ways to significantly reduce academic anxiety without requiring all resources, namely AI usage, class engagement, and perceived teacher support for AI usage, to reach high levels simultaneously. This also reflects the principle of “equifinality” emphasised in educational psychology research. This not only complements previous research that has focused on single or linear mechanisms, and further introduces a novel conceptual approach to unpack the complex pathways of academic anxiety in digitally mediated learning environments.

5.2. Practical Implication

Firstly, we found that in the context of insufficient class engagement and obvious academic anxiety among vocational education students, AI usage provides an important resource that can help alleviate this situation. This suggests that vocational education administrators should attach importance to AI technology as an important learning aid [

47] and give full play to its positive role in improving student class engagement and academic anxiety. First, students should be encouraged and guided to recognize the positive effects of using AI to assist in classroom and learning, so that they can actively use AI in the classroom with confidence and an open attitude [

25], make full use of the vast learning resources provided by AI, help enhance classroom interaction, and alleviate their academic anxiety. Second, administrators also need to provide the necessary technical support to help students use AI more reasonably and efficiently [

55]. For example, AI cognitive skills training courses and lectures can be conducted, AI learning spaces or interactive groups can be set up, and resources can be invested to provide the necessary equipment support to create a favourable environment for students to use AI. Third, the fsQCA results reveal three configurations that trigger low academic anxiety, reminding administrators to pay attention to the characteristics of different classes or student groups and to focus on improving AI usage, class engagement, and teacher support for AI usage in order to achieve the goal of alleviating academic anxiety.

Secondly, we found that teacher support for AI usage can strengthen the positive effect of AI usage on class engagement. Therefore, teachers should improve their cognitive attitudes and technical capabilities regarding AI tools, encourage and support students’ use of AI, thereby increasing students’ class engagement and alleviating academic anxiety. On the one hand, teachers should maintain an open and supportive attitude toward AI, allowing and encouraging students to use AI in classroom learning [

47], creating an open and inclusive classroom learning atmosphere, and reducing students’ concerns about not daring to use AI for fear of criticism [

1]. For example, when evaluating students’ classroom performance, teachers should positively express their recognition of the use of AI to assist in the learning process. On the other hand, in addition to attitudinal and emotional support, teachers should also provide technical guidance and demonstrations on the standardised and efficient use of AI tools to reduce students’ barriers to using technology [

46]. For example, teachers can demonstrate in class how to use AI tools for intelligent question and answer sessions, translation, writing, and learning plan development. They can also set up special AI usage teaching and classroom sessions to better understand students’ usage and provide targeted guidance.

Finally, for vocational education students, it is important to proactively understand and use AI technology to assist learning, take the initiative to use intelligent technology to improve their learning foundation and class engagement confidence, and alleviate their academic anxiety. On the one hand, they should correctly understand the role and functions of AI, overcome their fear of the unknown and the threat of technical barriers to using AI technology [

56], recognize that AI-assisted learning can play a positive role, and embrace AI with an open and confident attitude [

10]. On the other hand, they should actively learn how to use AI technology, such as by watching online courses and consulting teachers and classmates, to understand the diverse tools and related search commands of AI, so as to give full play to the powerful functions of AI technology in assisting learning and class engagement.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

The main limitations of this study are as follows, and they should be given full consideration in future research. The first limitation of this study is that all data were obtained from student self-reports. Although this study employed multiple methods to verify that CMV was not severe, CMV cannot be eliminated. Future research should adopt more scientific measurement methods, such as teacher evaluations for class engagement and academic anxiety, to enhance the robustness of the data. Second, although we endeavoured to obtain student survey samples from vocational education schools in multiple regions, including Sichuan, Chongqing, and Shanghai, which enhanced the representativeness and generalizability of the research conclusions, the coverage of the sample areas still needs to be improved, and future research can consider this. Third, although we used a multi-time point approach to collect data and used the fsQCA analysis method to infer causal relationships, the data we used was still cross-sectional data, which cannot reveal the causal relationships of the entire model. Future research may consider using longitudinal research designs or experimental methods to investigate the dynamic changes in academic anxiety and better infer causal relationships. Finally, we examined the important moderating role of perceived teacher support for AI usage. Future research may explore other factors at the individual and organisational levels to broaden the boundaries of the study.