1. Introduction

Evidence from stone tools in Mozambique suggests that early humans relied on cereal seeds as early as 100,000 years ago, much earlier than previously thought (Mercader, 2009). This reliance on seeds eventually led to the development of agriculture and the rise of civilisations. While modern agriculture plays a critical role in ensuring the quality and reliability of crop seeds, its reliance on traditional breeding techniques to generate new cultivars amidst intensifying climate change is projected to be insufficient to meet the anticipated global food demand of 11.6 billion tons by 2030 (Ahmad et al., 2021; Bailly and Gomez Roldan, 2023) highlighting the urgent need for integrating novel approaches such as genomics-assisted breeding, precision agriculture, advanced biotechnologies, and sustainable farming systems to enhance productivity and resilience. Improving seed quality and yield represents one of the most effective strategies to match this global food demand.

Seed quality is a critical aspect of the plants’ lifecycle, influencing germination success and eventual plant establishment and growth. Quality is determined by multiple factors, primarily seed genetic purity, viability, seed vigour, resistance to biotic and abiotic stressors (Taylor, 2003). Alongside seed quality, seed yield plays a pivotal role in agricultural productivity, exerting a direct influence on both global food security and the economic sustainability of agricultural communities. Seed yield refers to the total amount of viable seeds produced by a plant or crop per unit area. It is an indicator of performance in agronomic research and production (Australian Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development (ADPIRD), 2023). Seed yield is influenced by three main factors: environmental conditions, agronomic practices and the plant's genetics (Kameswara Rao et al., 2017). Advancements in omic technologies have provided a framework for enhancing seed quality and yield, offering novel insights into the underlying biological mechanisms and pathways.

Genomics examines the DNA sequence by utilising advanced technologies such as high-throughput sequencing, bioinformatics tools, and comparative analyses to identify genes, regulatory elements, and genetic variations underlying important biological traits. Genomic technologies, such as genome-wide association studies, whole-genome sequencing, and quantitative trait locus mapping, help unravel the associations between genotype and key seed traits, including seed size, yield, germination rate, and abiotic resistance (Sangam et al., 2020). Many plant species traits have already been improved through the use of genomic technologies, such as seed oil content in canola, grain size and weight in wheat, seed viability and grain quality in rice and drought tolerance in maize (Subedi et al., 2020; Hamdan and Tan, 2024; Angon et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2024; Mou et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2018). Gene editing technologies also provide alternative avenues to traditional plant breeding, allowing for the application of genomic technologies to improve seed quality and yield.

Transcriptomics, which examines gene expression, helps understand how genes are regulated during seed development and under various environmental conditions. Numerous transcription factors regulate various stages of seed development at the molecular level (Zhang et al., 2013). Transcription factors also regulate many seed development processes, such as organ formation, cell division and differentiation, and seed maturation (Agarwal et al., 2011).

Proteomics and metabolomics further complement these genomic technologies by analysing the proteins and metabolites influencing seed physiology and stress responses (Punia et al., 2024). Numerous proteomic and metabolomic studies have investigated the molecular changes that occur during early seed germination in various plant species (Fait et al., 2006; Gallardo et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2022). In recent years, advanced high-throughput analysis of complex metabolite mixtures has been utilised in seed studies, leading to the identification of metabolite biomarkers (Kalemba et al., 2025), identifying the role of galactose and gluconic acid in seed vigour (Chen et al., 2022), and the role of a seed’s proteome in biotic and abiotic resistance (Ahmad et al., 2016; Kausar et al., 2022). For instance, seed vigour and aging in rice are controlled by metabolomic markers such as galactose and gluconic acid (Chen et al., 2022). These two omic technologies provide effective methodologies for monitoring and analysing seed quality, vigour, and seed dormancy.

Epigenetics refers to changes in the expression of genes that do not involve changes in DNA sequence. Epigenomics studies these heritable changes, with a focus on DNA methylation and histone modifications (Miyaji and Fujimoto, 2018). Epigenetic control is known to play an essential role in plant development (Fujimoto et al., 2012). For example, asymmetric methylation affects embryogenesis, germination, and seed dormancy (Kawakatsu et al., 2017). Zhang et al. (2015) identified Epi-rav6, a gain-of-function epiallele in rice, which affects grain size through hypomethylation of the RAV6 promoter, leading to ectopic gene expression and altered brassinosteroid homeostasis.

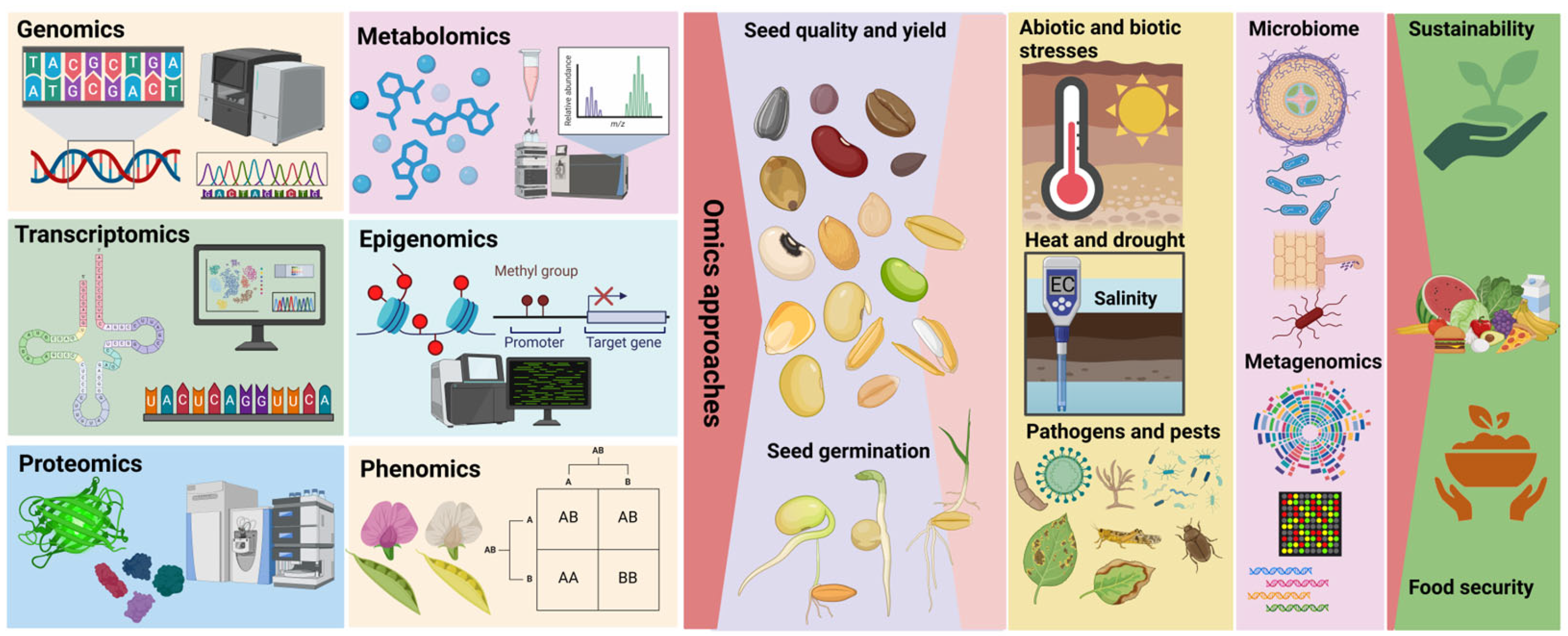

Integrating omics technologies into seed improvement programs can lead to significant advancements in crop breeding. These technologies facilitate the development of seeds with higher yields, improved nutritional profiles, and greater resilience to climate change. Consequently, omics technologies are indispensable for addressing global food security challenges and ensuring the sustainability of modern agriculture (

Figure 1) (Dwivedi et al., 2020; Faryad et al., 2021; Nasar et al., 2024).

This review discusses the importance of seed quality and yield enhancement, considering climate change and population growth, and then highlights how omics approaches can be used to improve seed-related traits and help overcome challenges in crop production by assisting in expediting conventional breeding techniques. We will demonstrate how each technology has been applied to identify the molecular markers of seed traits and seed viability during germination and dormancy. We also review how genome editing tools, such as CRISPR-Cas, can be leveraged to introduce beneficial traits into crops, enhancing their performance under various environmental conditions. Furthermore, we explored strategies for manipulating plant-microbe interactions, stress tolerance, and nutrient uptake.

2. Genomics Approaches

Genomic approaches in seed biology have revolutionised our understanding of seed quality and yield enhancement, offering valuable insights into the genetic diversity of seeds. Sequencing technologies are at the forefront of genomic approaches, with whole-genome sequencing (WGS) being the standard method. The advent of WGS has significantly advanced our understanding of plant genomics, enabling the identification of genes involved in traits such as crop yield, disease resistance and seed quality (Kumar et al., 2024). Variations in these traits among individuals of the same species are linked to single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), copy number variants (CNVs) and presence/absence variants (PAVs) (Hu et al., 2012; Dong et al., 2014; Jia et al., 2022). For instance, Xie et al. (2019) utilised optical mapping to compare wild and cultivated soybean varieties, identifying a significant inversion at the locus that influences seed coat colour during domestication. This variation is detected by comparing genetic sequences to a reference genome or pangenome (Amas et al., 2023; Hu et al., 2024). Alternatively, to WGS, genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are employed to identify genotypes associated with potential genetic traits, allowing for the easier identification of novel genes. GWAS were used in field peas to identify genome regions associated with seed traits (Gali et al., 2019). A total of 135 accessions were phenotyped and sequenced using WGS to identify SNPs that exhibited strong associations with seed quality traits, such as seed weight, yield, and protein concentration (Gali et al., 2019; Lipka et al., 2012). SNPs associated with seed quality traits can be introduced into other domesticated lines through crossbreeding and genetic introgression (Akpertey et al., 2018). In Brassica napus, a GWAS was conducted using PAVs identified from eight whole-genome assemblies, revealing causal associations between structural variants (SVs) and traits such as silique length, seed weight, and flowering time (Song et al., 2020). Gangurde et al. (2023) conducted WGS to map novel diagnostic markers for seed weight in the Arachis hypogaea genomes by comparing sequences to reference genomes. Sequencing was combined with sequencing-based trait mapping, including QTL-seq to identify genomic regions associated with seed weight on three chromosomes: B06, B08 and B09. Furthermore, 104 SNPs were identified across three genomic regions on B06 and 30 SNPs in the genomic region on B09 (Gangurde et al., 2023). These SNPs provide valuable diagnostic markers for accelerated breeding strategies to introduce weight-related genes to other cultivars. A study revealed that genome structural variations and 3D chromatin architecture play a crucial role in regulating seed oil content in Brassica napus, with the candidate gene BnaA09g48250D identified as a key regulator through fine-mapping and functional validation (Zhang et al., 2024). These genomic tools help researchers establish associations between SNPs, genes, and alleles and seed quality traits such as weight, vigour, and viability.

In plants, there are a multitude of genetic determinants that influence overall seed yield, primarily number of seeds per pod, plant height and pod shattering. Pod shattering is the rapid dispersal of seeds by the plant and causes a significant loss in crop yields; Brassica napus loses 15-50% of its total yield due to pod shattering under unfavourable weather or machine harvesting conditions (Zhai et al., 2019). Multiple loci associated with pod-shattering have been identified in B. napus, specifically on chromosomes A02, A03 and A09 (Raman et al., 2023). Additionally, these QTLs were mapped near homologous genes in Arabidopsis thaliana, primarily the FRUITFULL (FUL) gene. These results were obtained by genotyping an F2 hybrid derived from B. napus and an interspecific line (B. napus/Brassica rapa) resistant to pod shattering (Raman et al., 2014). In legume and crucifer crops, a non-functional copy of the pod shattering gene Pdh1 is frequently detected in North American landraces and is a likely candidate for higher seed yield (Funatsuki et al., 2014). This highlights the applicability of genomics in producing cultivars with higher seed yields through hybridisation. Similarly, a frameshift mutation in the brittle rachis one gene, rendering it non-functional, increases spike stiffness and reduces seed loss (Pourkheirandish et al., 2018). Fujita et al. (2013) and Gautam et al. (2020) utilised MAB to increase crop yield in rice and wheat, respectively, by analysing the genetics of plant height and yield per pod in overall seed yield. In wheat, a quantitative trait locus (QTL), Qyld.csdh.7AL, was associated with a 20% increase in grain yield and higher yield per ear. A closely linked simple sequence repeat (SSR) marker (Xwmc273.3) was identified, allowing breeders to apply marker-assisted selection (MAS) across generations (F1 to BC2F1) to improve yield (Gautam et al., 2020). In rice, MAS was used to introduce the SPIKE gene, which is associated with enhanced grain productivity, into Indica cultivars (IRRI146). This was achieved by introducing SPIKE to the recently released Indica cultivar, IRRI146, through MAS and introgression, and performing phenotypic analysis on the successive generations (Fujita et al., 2013). This study identified an 18% increase in crop yield of the successive generations. In identifying genes and SNPs linked to high seed yield, genomic technologies have become essential tools for advancing breeding efforts focused on maximising yield and minimising seed loss.

Pangenomes are a valuable tool in revealing species-wide genetic diversity and can uncover genetic variants linked to important traits, such as seed yield and quality. Pangenome analysis integrates whole genome sequencing of multiple individuals and aggregates the data, thereby capturing a broader spectrum of CNVs and PAVs (Tao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022). Pangenome analysis, with the support of phenotypic data and GWAS, can identify desirable genes for higher seed yields and improved seed quality (Tao et al., 2019; Li et al., 2022). For instance, a graph-based pangenome analysis of 29 soybean assemblies revealed a novel PAV linked to seed lustre (Liu et al., 2020). Similarly, pangenomic analysis in parallel with GWAS research uncovered 124 PAVs related to yield and fibre quality in cotton (Li et al., 2021), genes tied to seed characteristics and early leaf senescence in rice (Tanaka et al., 2020), PAVs associated with seed and flowering traits in canola (Song et al., 2020), seed weight in pigeon peas (Zhao et al., 2020). and 398 SNPs connected to agronomic traits in sorghum (Ruperao et al., 2021). In B. napus, PAV associations related to disease resistance were identified (Dolatabadian et al., 2020; Gabur et al., 2020; MacNish et al., 2024). These studies underscore the pangenome’s critical role in uncovering mutations associated with key seed traits, positioning it as a powerful resource in improving seed quality and yield.

Transgenic technologies provide an alternative application for genomic technologies beyond guiding traditional breeding methods, instead allowing for modifications to the plant genome directly. Previously identified SNPs and PAVs can be introduced into homologous crop species with lower seed performance profiles using site-directed nucleases such as the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Targeted editing used site directed nucleases (SDNs) to introduce these SNPs and PAVs into such species holds significant potential to enhance seed yield and quality (Podevin et al., 2013; Gogolev et al., 2021). SDNs have been used to increase seed yield and seed size in some commercial crops such as rapeseed (Khan et al., 2020), soybean (Yu et al., 2023), and wheat (Wang et al., 2019). A negative regulator of seed size in rapeseed was identified by modifying the gene regulator’s genetic sequence and rendering it non-functional using CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis (Gu et al., 2023). Knock-out of this ENHANCER OF DA1 gene in Brassica napus resulted in an overall increase in seed size and weight regardless of mutation. In maize, CRISPR-Cas9 was utilised to induce male sterility and produce a maintainer line for restored fertility (Qi et al., 2020), highlighting the use of gene editing technologies to streamline and expedite the introduction of male sterility into domesticated crops for hybrid seed production.

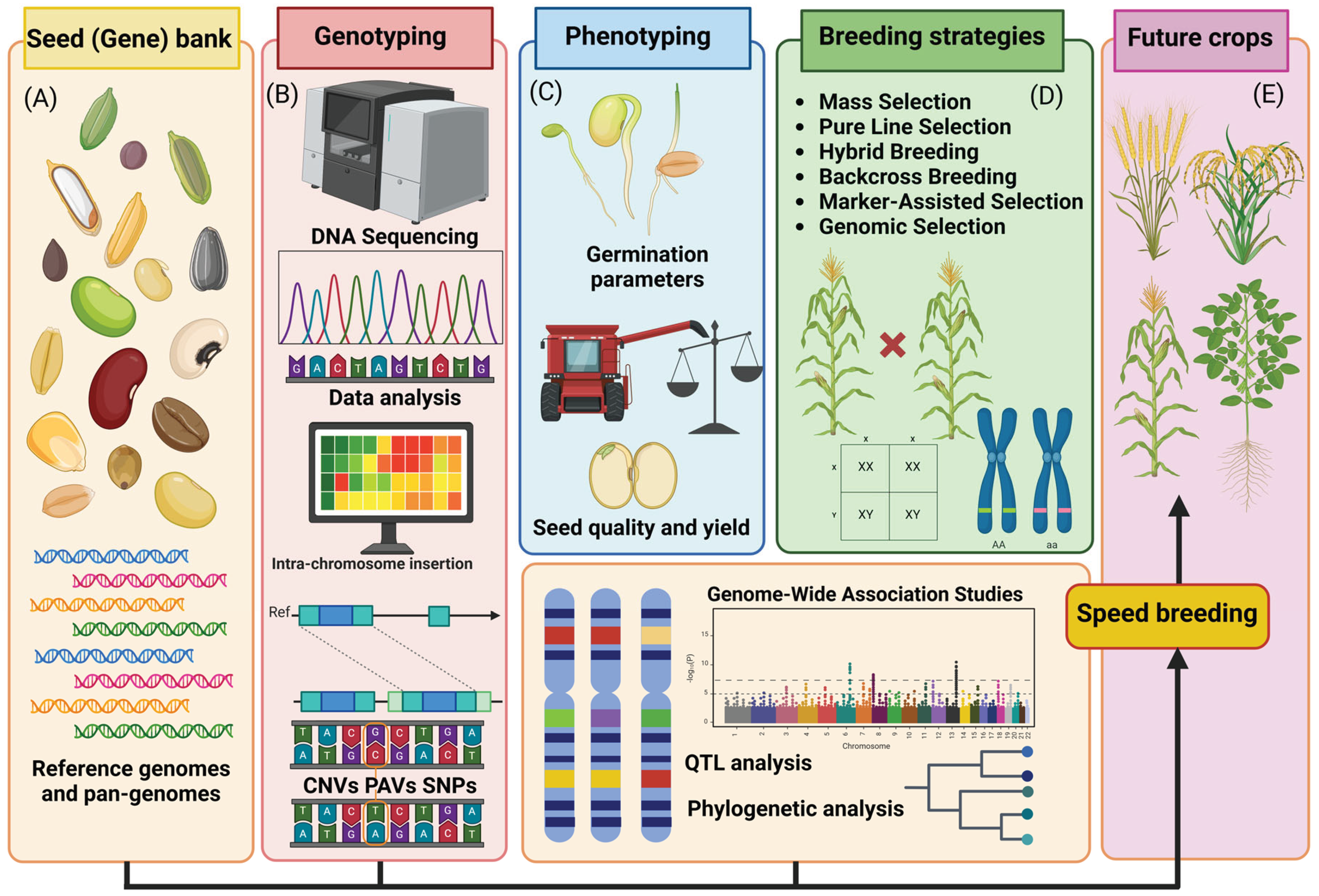

Seed enhancement relies on the genetic diversity of crops for the propagation of higher yield and disease resistance traits (Tripathi and Khare, 2016). However, domesticated crops are constrained by their limited genetic diversity due to selective breeding in the domestication processes, a phenomenon called genetic erosion (Khoury et al., 2021). Commercial crops possess limited diversity, particularly compared to their crop wild relatives (CWR); in 1999, the FAO estimated a 75% loss in commercial crop genetic diversity since the 1900s (FAO, 1999). For instance, commercial soybean crops have lost 79% of the rare alleles found in Asian landraces and retained only 72% of their sequence diversity, while B. napus exhibited limited genetic variation in genes associated with shatter resistance (Hyten et al., 2006; Raman et al., 2014). Domestication of these plants via traditional breeding methods will likely result in greater genetic diversity of domesticated crops and introduce new alleles associated with seed quality and seed yield (Omar et al., 2019; Rajpal et al., 2023). Additionally, transgenic technologies can rapidly domesticate CWR by de novo domestication and enrich the gene pool of domesticated crops (Fernie and Yan, 2019). Zsögön et al. (2018) employed a CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing strategy to rapidly domesticate wild Solanum pimpinellifolium (wild tomato) to alter the fruit yield size and overall crop yield. This method of de novo domestication resulted in a tenfold increase in crop yield and a threefold increase in fruit size compared to the wild progenitor parent. Currently, the application of transgenic methods in seeds is limited due to regulations on gene editing. However, with an improved understanding of SDNs and changes to laws and regulations, these genomic technologies can enhance overall seed yield and quality of crops, and introduce newly domesticated plant species into the market (

Figure 2).

3. Transcriptomics Insights

Transcriptomics provides a snapshot of seed gene expression by analysis of the seed’s RNA content and composition. Gene expression is influenced by gene sequence and epigenetic factors, and in turn dictates seed traits, particularly seed size and dormancy (Gibney and Nolan, 2010). RNA molecules, including mRNA (Bai et al., 2020), rRNA (Brocklehurst and Fraser, 1980) and tRNA (Kedzierski and PaweŁkiewicz, 1977), are differentially expressed depending on the current growth stage and growth conditions of the seed (Han et al., 2015, Yang et al., 2022, Jain et al., 2023, Krzyszton et al., 2022). For instance, Chu et al. (2021) performed RNA-sequencing on two strains of B. napus with varying pod-shatter resistance (one susceptible and one resistant) to identify genes associated with pod-shattering resistance. They identified 16,878 differentially expressed genes at the later stages of seed development. These genes were narrowed down to only 16 by focusing on down-regulated genes in the resistant strain and utilising reference genome map intervals (Chu et al., 2021). Among these, BnTCP8.CO9 emerged as a strong candidate for association with pod shatter resistance and was reverse transcribed into cDNA for cloning and further functional analysis. This study underscores the utility of transcriptomic approaches in elucidating gene expression patterns relevant to seed yield and development traits.

Seed quality is dictated by the molecular mechanisms of early seed development, and transcriptomics provides insights into these dynamics. In soybean seeds, transcriptome analysis by RT-qPCR was performed to capture the temporal patterns of gene expression during seed development (Hu et al., 2023). 199 genes strongly correlated with seed weight were identified, including a novel transcription factor gene, GmPLATZ, that regulates cell proliferation-related genes and is a critical determinant in seed size and weight. GmPLATZ, is continuously expressed and is not degraded during seed development and maturation (Hu et al., 2023; Li et al., 2023). In Brassica juncea, comparative transcriptome analysis between small- and large-seeded lines uncovered a total of 5,974 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including 954 transcription factors (Mathur et al., 2022). Co-expression analysis revealed two modules correlated with increased seed size within these modules, eight DEG were identified that had a strong correlation with increases in seed size, some of which were novel candidates for association with seed size. Similarly, RNA-seq in tomatoes identified 54 seed size-associated DEGs related to transcription factors, hormones, and starch biosynthesis (Li et al., 2023). These findings provide valuable genomic resources and insights into the regulation of crop seed development, which is crucial for determining yield and seed quality.

Transcriptome analysis provides a complementary approach to genomic technologies in enhancing seed quality and yield, but also potentially assists breeders and growers in refining their agronomic practices to optimise seed traits through creating detailed nutrient profiles or growth programs based on seed gene expression in response to stimuli (Takehisa and Sato, 2021). Takehisa and Sato (2019) performed transcriptome monitoring of rice during the period of growth from seed to fruiting to monitor the gene expression dynamics in response to dynamic external nutrient statuses in the field. They highlighted how seeds and plants in varying soil conditions will have altered gene expression during critical stages of growth. By capturing gene expression profiles, transcriptomics goes beyond ‘mining for genes’ and, as explored previously, identifies genes that promote seed yield and growth by analysing those expression profiles during germination. These identified genes can then be validated using genomic technologies, such as pangenome analysis and homology analysis, and introduced into species through MAS breeding or gene editing. Advances in transcriptomics aimed at improving seed quality and yield also enhance our understanding of the seed growth cycle and how gene transcription responds to various stimuli and agronomic practices.

4. Proteomics Advances

Advances in proteomics have significantly enhanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying seed yield and quality, offering valuable insights into the functional proteins that directly influence these complex traits. Structurally, seeds comprise a seed coat, the endosperm, cotyledons and embryonic axes (Miernyk, 2013). A significant portion of the seed’s protein content consists of storage proteins, which serve as nutrient reservoirs and markers of seed quality. Separated proteins are analysed using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and MALDI-TOF to determine their precise molecular weight and protein sequence (Ribeiro et al., 2020; Reeve and Pollard, 2019; Chen et al., 2022; Ran et al., 2024). These techniques have been applied to various crops to investigate seed proteomes under stress conditions, such as in studies of soybean plasma membrane proteins under osmotic stress (Nouri and Komatsu, 2010), shotgun proteomic profiling of quinoa seeds (Galindo-Luján et al., 2021) and proteomic characterisation of herbicide-tolerant soybean seeds (Varunjikar et al., 2023). Stress-responsive proteomic studies enable comparisons between experimental and reference seed proteomes, offering insights into proteins associated with resilience and productivity.

The development of reference proteomes has further advanced the utility of proteomics in seed research. For instance, Bourgeois et al. (2009) established the first reference proteome of mature pea seeds. They identified 156 proteins, including 88 storage proteins, 25 involved in stress response, 18 associated with energy and metabolism, and 25 linked to storing non-protein compounds and other functions. This map was generated through two-dimensional gel electrophoresis (2D-GE), followed by MALDI-TOF MS. This approach enables precise identification of seed protein content, which is crucial for assessing nutritional quality for human consumption. The combination of 2D-GE and MALDI-TOF produces a seed proteomic map with known protein profiles, facilitating comparisons with other seed proteomic maps or genetically modified pea seed cultivars. Seed proteome maps have also been developed for other crop species, including wheat (Afzal et al., 2023), Arabidopsis (Galland et al., 2014), the nuclear proteome of Medicago truncatula (barrel medic) (Repetto et al., 2008) and Pisum sativa L. (pea) following deletion of vicilin-related genes (Rayner et al., 2024). Reference proteomes provide alternative avenues for evaluating seed nutritional content and comparison of proteomes across cultivars.

Proteomics has also emerged as a powerful tool for deciphering the molecular mechanisms that regulate seed nutritional quality, providing valuable insights into protein composition, metabolic pathways, and post-translational modifications that influence nutrient accumulation. Seed protein composition varies widely across species. For instance, soybean seeds contain approximately 36-40% protein, making them a significant dietary protein source. In contrast, rapeseed meal, obtained after oil extraction, has a protein content of 35-45%, but it is primarily used as animal feed rather than for human consumption (So and Duncan, 2021). This is partly due to its dominant storage protein, 2S napins, which are albumin-like proteins that are not easily digestible (Nietzel et al., 2013). Similarly, maize seeds contain approximately 9.5% protein, of which 80% consists of storage proteins (Flint-Garcia et al., 2009). The predominant storage proteins in maize are alpha-zeins, which lack three essential amino acids: lysine, tryptophan and methionine (Flint-Garcia et al., 2009; Paulis and Wall, 1977). Proteomic analysis of different maize cultivars has revealed that those carrying a mutant opaque-2 gene exhibit increased lysine content in the endosperm, as determined by nitrogen content analysis (Mertz et al., 1964). This finding highlights the role of proteomics in identifying mutant strains or cultivars with enhanced nutritional profiles compared to conventionally bred varieties.

Seed vigour and seed longevity are two aspects of seed quality that have direct impacts on seed germination. Current methodology to determine seed vigour relies on the assumption that all seeds sown are grown in optimal conditions to allow for uniform germination. However, seed proteomics presents an alternative avenue for assessing seed quality and vigour. Proteomics using the methodologies described above can facilitate the development of biomarkers to determine the seed vigour after sowing and longevity after long-term storage. Wu et al. (2011) identified 28 proteins that were differentially expressed in viable maize seeds compared to dead seeds. Proteins related to abiotic stress resistance, stabilisation and nutrient storage were up-regulated in high-viability seeds and proteases were down-regulated in high-viability seeds. Correct metabolite and protein storage is critical in retaining the viability of seeds over a prolonged time, as these assist in the induction of germination (Yacoubi et al., 2013; Shen et al., 2018). Improper seed storage will negatively impact the vigour and viability of seeds. Proteomics can identify biomarkers of this relationship between storage conditions and seeds and the impact on seed expression and synthesis. In Lupinus albus, seeds stored at 14°C had a germination rate of 86.3%, compared to the 0% germination rate of seeds stored at temperatures greater than 20°C (Dobiesz and Piotrowicz-Cieślak, 2017). Of the two seed groups, vicilin-like proteins (γ conglutin) were more abundant in the low-temperature-stored seeds, which supports the findings of previous proteomic studies, as these proteins are involved in nutrient reservoirs. The presence of seed proteins and metabolites is a critical determinant in the viability of seeds; therefore, placing a greater importance on joint metabolomic and proteomic studies to measure these seed metabolites and nutrient reservoirs.

5. Metabolomics

Seeds contain a diverse array of metabolites that are essential for their growth, development and eventual germination. These metabolites include carbohydrates, lipids, proteins, amino acids and secondary metabolites (Campbell et al., 2021). Profiling these metabolites provides valuable insights into the biomechanical pathways involved in seed formation, storage and dormancy (Song and Zhu, 2019). Metabolomic analysis is conducted by high-throughput techniques such as GC-MS, LC-MS and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Chen et al., 2022; Ran et al., 2024; Terskikh and Kermode, 2011). GC-MS is particularly effective for analysing volatile compounds and small metabolites which are easily vaporised at low temperatures (Chen et al., 2022). LC-MS is particularly beneficial for examining complex seed extracts that may be more temperature sensitive, providing qualitative and quantitative insights into metabolite composition (Peixoto Araujo et al., 2020).

Metabolites play pivotal roles in energy storage, cellular function and defence mechanisms within seeds. These functions contribute to key seed quality parameters, including viability, vigour, weight and dormancy (International Seed Testing Association, 2015). Metabolomic analysis enables the investigation of biochemical pathways responsible for metabolite synthesis and degradation. For instance, Qi et al. (2023) used LC-MS to analyse carbohydrate profiles in Amorphophallus muelleri during growth cycles. Their study identified 46 carbohydrates in A. muelleri, including nine sugars and 37 glycosidic substances, mapping their accumulation patterns across different developmental stages (Qi et al., 2023). Campbell et al. (2021) examined the metabolomic profile of Avena sativa L. and found that 57% of the annotated metabolites were lipid-like molecules. LC-MS and GC-MS were utilised to screen 100 latent factors of the seed metabolome, and it was identified that 37 were enriched. Most of these enriched latent factors were associated with lipid metabolism (Campbell et al., 2021). Additionally, the relationship between seed quality and seed size was explored by profiling the amino acid content of Medicago truncatula using GC-MS (Domergue et al., 2022). There is a positive correlation between free amino acid content and seed size of M. truncatula. This demonstrates that by measuring these key regulators in the seed’s metabolome, metabolomics provides valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying seed quality, offering a more comprehensive understanding of seed vigour and its potential for successful cultivation.

Metabolomics offers a complementary approach to genomics for the rapid assessment of seed viability and quality. For example, in Torreya yunnanensis seeds, ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS)-based metabolomics analytical methods were employed to evaluate the seed quality during cold storage (Zhou et al., 2024). A total of 373 metabolites were identified, including 92 lipids, 83 phenolic acids, 63 amino acids, 38 nucleotides, 24 saccharides, 11 vitamins and 9 alcohols. Zhou et al. (2024) selected 49 metabolites with the most significant differential regulation post-cold storage from this dataset for further analysis. Among these, lipids were the most abundant class, followed by organic acids and amino acids, thereby acting as biochemical markers for farmers and breeders in developing optimal storage methods for seeds. Chen et al. (2022) identified metabolomic biomarkers of seed vigour and aging in rice using GC-MS. Their study found that galactose, gluconic acid, fructose, and glycerol levels significantly increased with seed aging. Notably, galactose and gluconic acid displayed a strong negative correlation with seed germination, suggesting their potential as biomarkers for assessing seed viability. Conversely, specific metabolites positively correlate with seed longevity. In Arabidopsis thaliana and Brassica oleracea var. capitata (cabbage) seeds, GC-TOF-MS analysis and germination assays revealed that galactinol content positively correlates with seed longevity during storage (de Souza Vidigal et al., 2016). Metabolomics can determine seed quality over extended periods of storage, with variation between seed species. Reference metabolomes may greatly benefit farmers and researchers.

6. Epigenomics

Epigenomics studies the complete set of epigenetic modifications on an organism's DNA and histone proteins. These modifications can significantly impact plant seed quality and yield, influencing traits such as germination, vigour, and stress responses (Gallusci et al., 2017; Kakoulidou et al., 2021). This has led scientists to reevaluate the connection between genotypes and phenotypes (Pikaard and Mittelsten Scheid, 2014; Meyer, 2015; Rey et al., 2016). Key aspects of epigenomics in seeds include DNA methylation, which is changes in DNA methylation patterns that can lead to alterations in gene expression, affecting seed development and quality (Gallego-Bartolome, 2020; Gupta and Salgotra, 2022). For instance, appropriate methylation can enhance seed vigour and longevity, as Mira et al. (2020) investigated how seed ageing affects nucleic acid stability and identified molecular markers for monitoring epigenetic changes in plant conservation. They observed aged Mentha aquatica seeds stored at high temperatures and humidity, finding a 50% reduction in germination after 28 days. Methylation-sensitive amplification polymorphism revealed an 8% epigenetic difference in aged seeds and 16% in seedlings (Mira et al., 2020). These findings indicate that stress during storage affects methylation and DNA integrity in seeds and their seedlings. A study by Han et al. (2022) presented a gene expression atlas of 16 castor bean tissues and identified 1,162 seed-specific genes. Whole-genome DNA methylation analysis revealed 32,567 differentially methylated valleys (DMVs) across five tissues, which are highly hypomethylated and conserved across plants. DMVs were found to activate transcription, particularly of tissue-specific genes, and contain key regulators of seed development.

Histone modifications can also regulate genetic expression related to traits such as disease resistance and tolerance to abiotic stress, which directly influence yield (Shi et al., 2024). A recent epigenetic study showed that histone modifications regulate key genes involved in phytohormone metabolism and signalling, such as DELAY OF GERMINATION 1 and DORMANCY-ASSOCIATED MADS-box genes (Sato and Yamane, 2024). Histone modification analysis showed that most modifications occur within DMVs, and distal DMVs may function as enhancers, highlighting their crucial role in regulating seed-specific gene expression (Han et al., 2022).

Small RNAs are involved in gene regulation. They can help control the expression of genes critical for seed development and response to environmental factors (Das et al., 2015). Small RNAs play a crucial role in seed germination and dormancy by regulating key genes involved in phase transitions. In addition, small RNAs direct and mediate epigenetic modifications in plants. Small RNAs in plants guide epigenetic changes, including DNA methylation, histone, and chromatin modifications, which control gene activity (Simon and Meyers, 2011). Studying siRNA-directed DNA methylation has revealed how plants regulate gene silencing, heterochromatin formation, paramutation, imprinting, and epigenetic reprogramming. Advances in next-generation sequencing have enabled the mapping of the plant epigenome, thereby improving our understanding of the biological roles of these epigenetic marks. Mutations in DCL1, HYL1, HEN1, and AGO1 disrupt embryogenesis and seed development (Willmann et al., 2011), with DCL1 being positively regulated by LEC2 and FUS3 and repressed by ASIL1, ASIL2, and HDA6/SIL1 (Willmann et al., 2011). Various miRNAs, including miR156, miR159, miR164, miR167, and miR172, influence germination and dormancy (Jung and Kang, 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Reyes and Chua, 2007; Kim et al., 2010a, b; Martin et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2013), with miR156 maintaining dormancy by down-regulating SPL and miR172 (Martin et al., 2010; Huang et al., 2013). Imbibition further alters miRNA levels, promoting germination (Li et al., 2013), while miR156 and miR157 also regulate flowering transitions (Wu et al., 2009). Breeding programs increasingly incorporate epigenomics knowledge to enhance seed quality (Tonosaki et al., 2022). For example, a study analysed epiallele stability in Brassica napus, finding that 90% of methylation markers remained stable across environments and 97% were inherited through five meioses. Researchers mapped 17 of 19 centromeres and observed distinct clustering of epiloci and genetic loci, aiding in detecting new QTLs (Long et al., 2011).

Epigenetic editing is a technique used to modify gene expression by changing epigenetic marks on DNA or histones rather than altering the DNA sequence itself. This can be achieved using tools like CRISPR. Epigenetic editing allows breeders to fine-tune traits without altering the genetic sequence itself (Qi et al., 2023). Epigenetic modifications influence chromatin structure and gene regulation, playing a crucial role in crop improvement by controlling plant growth, enhancing stress and disease resistance, and regulating fruit development (Qi et al., 2023). Through epigenetic studies, breeders can enhance plants' ability to adapt to changing climates, ensuring consistent yields even under stress conditions.

7. Phenomics

Phenomics examines the physical and biochemical traits of organisms. In seed science, it quantifies phenotypic characteristics such as seed size, shape, colour, protein and oil content, moisture levels, and germination potential, providing precise, high-throughput data that can inform breeding, quality assessment, and crop improvement strategies. Over the past two decades, significant advancements have been made in non-destructive techniques for exploring and understanding seed phenomics (Hacisalihoglu and Armstrong, 2023). Non-destructive phenomics techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), fluorescence microscopy, computed tomography (CT), and spectroscopic techniques like near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, enable researchers to gather detailed molecular, biochemical, and structural information about organisms without causing damage. Other high-throughput phenotyping (HTP), including imaging, spectroscopy, robotics, LiDAR, UAVs, and deep learning, enables rapid, non-destructive evaluation of traits such as plant height, biomass, seed morphology, disease resistance, stress tolerance, pigment content, and nutrient profiles, improving understanding of genetic diversity and informing breeding and conservation strategies (Fernando et al., 2023). These methods are useful for studying crop growth, development, and their responses to climate stress, helping to uncover the mechanisms driving biological processes (Rahaman et al., 2015).

Hacisalihoglu and Armstrong (2023) reviewed recent advances in non-destructive seed phenomics methods, which are crucial for evaluating seed quality and improving crops to support global food security. They highlighted techniques such as FT-NIR, DA-NIR, SKNIR, MEMS-NIR spectroscopy, hyperspectral imaging, and micro-CT. In addition, Ghamkhar et al. (2024) explored the transformative potential of phenomics technologies in genebanks, particularly for traits like disease resistance, drought tolerance, and root characteristics.

Another study (Rodriguez et al., 2022) evaluated interspecific hybrids of Phaseolus vulgaris, P. acutifolius, and P. parvifolius using quantitative phenomic descriptors to overcome the limitations of traditional qualitative genebank traits. Parent accessions and their hybrid line (INB 47) were grown and analysed for seed and pod morphometrics, physiological traits, and yield using multivariate and machine learning techniques. The hybrid showed low similarity to its parents, about 2.2% with P. acutifolius and 1% with P. parvifolius for physiological traits, and 4.5% with P. acutifolius for seed traits. The results demonstrate that phenomic proportions of parental traits can be quantified, providing a tool to verify trait transfer, identify key phenomic markers, and support genebank curation and breeding decisions.

Seed phenotyping using automated imaging and AI enhances quality assessment, while plant content analysis supports biofortification for nutritional improvement (Maciel et al., 2019.

Rodriguez et al. (2022) used phenomics descriptors and machine learning to analyse three bean accessions and an interspecific hybrid (INB 47). They identified key traits for classification, such as seed and pod characteristics, physiological behaviour, and yield. The hybrid showed low similarity with its parent accessions. In another study, Laurençon et al. (2024) focused on improving seed germination in oilseed rape, which is crucial for crop establishment and stress tolerance. It identified 17 QTL related to seed germination traits, with favourable alleles corresponding to the most frequent alleles in the panel. Both genomic and phenomics prediction methods were used, showing moderate-to-high predictive abilities and capturing small additive and non-additive effects for germination. The phenomics prediction was found to estimate phenotypic values more accurately than genomic estimated breeding values (GEBV), and it was less influenced by the genetic structure of the panel, making it a valuable tool for characterising genetic resources and designing breeding populations.

In addition, advancements in sensors, imaging, and automation have led to the development of high-throughput, automated, and intelligent phenotyping systems across various scales (Yang et al., 2020). Technologies such as micro-CT, LAT, 3D scanners, ground-based platforms, and aerial drones enable detailed phenotyping at the cellular, organ, plant, and field levels (Zhao et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020). Beyond data collection, improvements in software and analytical methods for trait extraction and standardisation enhance phenotyping efficiency. These innovations allow breeders to monitor crop performance and environmental conditions with greater precision, identifying minor environmental effects and improving the genetic analysis of complex traits, particularly those controlled by minor-effect QTLs.

Overall, advances in seed phenomics have significantly improved the ability to analyse seed traits with high precision and efficiency. Non-destructive imaging and spectroscopic techniques provide detailed insights into seed composition, morphology, and physiological responses to environmental stress. Integrating phenomics with genomic prediction enhances the understanding of seed-related traits, including germination, biochemical composition, and yield potential.

8. Seed Dormancy and Germination

Seed dormancy is a crucial adaptive trait that regulates the timing of germination to ensure seedling survival under favourable environmental conditions. When drought, nutrient deficiency, or insufficient light are present, premature germination can lead to poor seedling establishment or plant death. Seed dormancy delays seed germination until conditions are more favourable. Two sets of hormonal regulators, which are small metabolites, regulate seed dormancy as positive regulators, such as abscisic acid (ABA), by maintaining dormancy and negative regulators, such as nitric oxide and gibberellic acid (GA), by inducing germination (El-Marouf-Bouteau, 2022). Metabolomic analysis by LC-MS of alfalfa seeds revealed that there is a greater accumulation of secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids and phenolic acids, in seeds during dormancy compared to germination phases (Wang et al., 2023). Additionally, Wang et al. (2023) recorded significantly greater levels of ABA in dormant seeds compared to seeds entering or undergoing germination. This supports the current literature regarding ABA, which is primarily recognised as a hormonal regulator of seed dormancy, inhibiting water uptake and preventing radicle growth initiation (Schopfer et al., 1979; Shu et al., 2016). ABA is critical in its interactions with other small metabolites in regulating seed dormancy across all seed species (Wang et al., 2023). Transcriptome analysis of alfalfa seeds supported the metabolomic findings, highlighting ABA’s central role in seed dormancy. Four-hundred and seventy-eight differentially expressed genes were identified using RNA-seq, notably ten genes involved in negative regulation of ABA were downregulated during dormancy. Additionally, chitinases that are involved in seed defence were upregulated in alfalfa seeds; this correlates with the proteomic analysis of soybean seeds (Wang et al., 2023, Gijzen et al., 2001). Proteins were extracted from Soybean seed hulls and analysed by SDS-PAGE. Abundant in the coat of dormant soybean seeds was a novel 32 kDa chitinase enzyme, demonstrating the role of the proteome in seed defence and dormancy. At a genomics level, seed dormancy in Arabidopsis thaliana is partially determined by the gene expression of the DOG1 (Delay of Germination1) (Huo et al., 2016). The concentration of DOG1 RNA transcripts influences the depth of seed dormancy, and during imbibition, the transcripts rapidly degrade in preparation for seed germination (Bentsink et al., 2006). The DOG1 gene and its conserved homologs form the genetic basis that influences the seed’s transcriptome, proteome and metabolome in determining seed dormancy, repression of this gene as a response to optimal temperatures, salt concentration or water availability, will eventually result in seed germination (Graeber et al., 2014, Nakabayashi et al., 2012).

Seed germination marks the transition from dormancy to a metabolically active seedling. A seed's vigour, determining its germination rate, stress resilience, and uniformity, is a critical factor in germination and successful crop establishment. However, seed vigour declines during dormancy, making seeds increasingly susceptible to stress and reducing their germination potential (Finch-Savage and Bassel, 2015). Omics technologies, including transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics, have emerged as powerful tools for determining and enhancing a seed’s vigour. In addition to regulating seed dormancy, DOG1 has also been identified as a biomarker of seed vigour, particularly the dog1 mutation, which is associated with seed longevity and high germination rate after several days of storage (Bentsink et al., 2006). Introducing the dog1 allele by marker-assisted breeding will result in A. thaliana seeds that have greater longevity and vigour after short storage periods, resulting in more uniform and predictable germination rates. Proteins are suitable biomarkers for seed vigour in Spinacia oleracea during priming. Chen et al. (2010) identified two classes of proteins that act inversely to each other: Type I (37 and 35 kDa proteins) are at greater concentrations in unprimed seeds and degrade during seed priming, and Type II (20 kDa proteins) accumulate over time during priming of seeds. These proteins are beneficial in determining a seed’s vigour and the stage between dormancy and germination. The transition to germination from dormancy is highly controlled by the seed’s metabolic profile. Gibberellins are the metabolite regulators of seed germination and are the antagonistic regulators to ABA, but the exact mechanism of how GA breaks dormancy remains unknown (Shu et al., 2016). Metabolomic analysis can elucidate how GA interacts with ABA and GA-regulated genes to induce germination. Other metabolites also influence germination and seedling establishment as a response to environmental conditions. Seed fatty acid content in Sesasmum indicum L. (sesame seeds) impacts germination by increasing the optimum and maximum temperatures for germination to occur (Balouchi et al., 2023). Seeds employ multiple molecular mechanisms to ensure germination is induced at the correct conditions, but prolonged dormancy can result in a reduction of seed vigour, leading to delayed germination and non-uniform germination rates.

9. Abiotic and Biotic Stress-Resistant Seeds

Omics approaches offer valuable insights into the genetic, molecular, and biochemical mechanisms that drive plant immunity. Developing abiotic stress-resilient seed varieties is critical to ensuring food security in the face of climate change and increasingly erratic environmental conditions (Pourkheirandish et al., 2020). In Australia, abiotic stresses accounted for 63% of the total yield loss from 2022-2023 (Slatter, 2024). This highlights the urgent need for genomic tools to mitigate such losses and enhance crop resilience in the face of climate change and a growing population. Genome-wide association studies are a powerful tool for identifying genetic loci linked to complex traits related to abiotic stress tolerance and can be used in molecular breeding (Aleem et al., 2024). CRISPR-Cas technologies provide a new avenue to introduce agronomically relevant gene regulators into crop plant species without relying upon breeding techniques. Abiotic stressors, including drought (Guo et al., 2021; Hussain et al., 2019), fluctuating temperatures (Hatfield and Prueger, 2015; Thenveettil et al., 2024), and salinity (Welbaum and Bradford, 1990; Khajeh-Hosseini et al., 2003), affect seeds in species-specific ways, primarily by altering the proteome, genome, and metabolome, which can lead to seed loss, reduced quality, and compromised viability. For instance, every 1°C increase in temperature, rice and wheat yields decrease by 2.8% and 2.4%, respectively “when evaluated at the global mean temperature for each crop” (Agnolucci et al., 2020). Multiple genes and QTLs associated with drought resistance and heat tolerance have been identified in domesticated crops using comparative genomics, next-generation sequencing in parallel with genome-wide association studies and reverse-genotyping through transcriptomics and RNA-seq (Vikram et al., 2012; Bhardwaj et al., 2022). For instance, Ghazy et al. (2024) utilised a novel technique in rice to identify SNPs across the genotypic data from 1554 accessions with 413 genotypes to identify genes associated with traits such as number of days to heading, yield, sterility, panicle length and tillers per plant under drought and normal growth conditions. The high-density rice array (HDRA) panel, in parallel with GWAS, identified 700,000 SNPs, 340 were associated with all traits in both growing conditions, 189 SNPs of which were associated with all traits under water drought (Ghazy et al., 2024). 26 SNPs were associated with increased yield in both growth conditions, and due to their pleiotropic effects on multiple traits, they provide suitable candidates to be introduced into other cultivars by marker-assisted breeding and site-directed nuclease gene-editing. Heat-tolerant genes have been identified using a similar genotyping methodology by sequencing for SNP calling in Cicer arietinum L. (chickpea) (Jha et al., 2021). Jha et al. (2021) genotyped 77 QTLs associated with heat stress tolerance, with effects on days to flowering, yield, cell membrane and chlorophyll content and identified key heat stress-responsive genes in each QTL. Identifying these traits and genes is crucial in maintaining seed and crop quality in a changing climate, thereby preventing crop loss and maintaining a consistent level of crop yield.

Crop wild relatives form an alternative reservoir for biotic and abiotic resistance genes that can be utilised in the adaptation of modern cultivars. Modern domesticated plants are increasingly vulnerable to biotic and abiotic pressures compared to their CWRs, which may be attributed to the loss of genetic information during domestication (Petereit et al., 2025) while CWR contain a wide range of genes that enhance resistance to abiotic stresses (Quezada-Martinez et al., 2021). Resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses has been studied in wild relatives of various crops, including chickpea, barley, and maize (Brozynska et al., 2016; Fustier et al., 2017; von Wettberg et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020). For instance, WGS identified a novel salt tolerance gene in wild soybeans, resulting in increased seed yield compared to their domesticated variants (Qi et al., 2014). CWRs offer a valuable resource of beneficial genes, particularly for seed viability and resistance, that can be introduced to domesticated crops by breeding or gene editing.

The need for abiotic and biotic stress-resistant seeds is increasing over time as the level of genetic diversity in plants decreases. Consequently, bacterial and fungal isolates are becoming more genetically diverse to overcome plant disease resistance. Climate change is only progressing and accelerating further, and will create rapidly changing environments with a higher frequency of droughts and floods, and the planet’s overall temperature continuing to rise. There is a greater need for more versatile and adaptable cultivars.

Biotic resistance is critical in seeds to guarantee seed viability prior to germination and future plant health. The most prevalent biotic stressors affecting seeds are allelochemicals, bacteria, fungi, viruses and insects (Begum et al., 2024). Generally, infection of seeds by microorganisms occurs by transmission from the parent plant by the vascular system or during germination (Pagán, 2022; Kachap et al., 2025). For instance, the bacteria Pseudomonas syringae pv. Syringae accumulates on the seed coat and funiculus of peas until the seed is further developed, where it begins to form cavities within the seed coat and surrounding the embryo. However, literature regarding the molecular mechanisms in response to infection is limited. This may be due to difficulties phenotyping seeds with biotic stress resistance, or that seeds do not possess mechanisms to respond only to biotic stress. Much of a seed’s biology already tends towards defence, for instance, the seed coat is the primary defence of seeds by acting as a physical barrier against chemicals, plant hormones and fungal and bacterial pathogens (Buchmann and Holmes, 2015). Many plant pathogens, such as Leptosphaeria maculans that infect Brassicaceae species, require a wound for infection; however, wounds in the seed coat can result in loss of viability of the seed and minimal nutrients for the pathogen (West et al., 2001). Seed dormancy, as discussed previously, is another biological feature that assists in biotic defence. Seeds have minimal metabolic activity in their dormant state, making them not suitable targets for pathogens that require plant cells to be metabolically active to leach nutrients or chemicals and hormones that are actively absorbed by the plant cell wall (Nonogaki, 2014; Begum et al., 2019). Much of the molecular analysis of biotic defence has focused on the compounds and enzymes present on the seed coat and in the spermosphere during dormancy and germination (Hubert et al., 2024). For instance, transcriptomic and proteomic analysis of Medicago truncatula revealed a regulatory subunit involved in dormancy that also influences expression of pathogenesis-related proteins (Bolingue et al., 2010). Omic technologies can expand our understanding of seed resistance to biotic stress by further elucidating these pathogen-related proteins and their metabolic pathways.

10. The Role of Seed/Soil Microbiome in Quality and Yield

Microbes inhabiting the seeds can influence the quality of the seeds in terms of higher germination rates and tolerance under stressful conditions. For example, the microbiome can enhance performance in various environments by providing essential nutrients through nitrogen fixation (Suman et al., 2022). The soil microbiome interacts with plant roots, promoting nutrient acquisition such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium which are vital to overall plant development (Wang et al., 2024). Mycorrhizal fungi were shown to facilitate better water and nutrient uptake with extended root networks, particularly in nutrient-depauperate soil (Begum et al., 2019). Microbes in seed and soil can outcompete damaging pathogens leading to fewer seed-borne diseases or post-harvest decay. The production of antimicrobial metabolites from beneficial microbes can suppress pathogenic microorganisms (Raaijmakers & Mazzola, 2012). Furthermore, the microbiome allows plants to be more resilient in a less optimal environment such as drought, high salinity, heavy metal levels or extreme temperatures by producing growth hormones or enzymes with better outcomes in the survival rate of seedlings plus higher yields (Singh et al., 2023).

Seeds can house a diverse community of microbes exteriorly as epiphytes or interiorly as endophytes (Nelson, 2018). Microbes that inhabit seed embryos and endosperm tissues can be vertically transmitted onto progeny plants compared to those residing on seed surface which can be transmitted horizontally or vertically (Barret et al., 2015). Handling during transportation and storage also plays an important role in the seed microbial recruitment (Sun et al., 2023). Seed microbiome studies started with a culture-based approach isolating mostly endophytic bacteria from cultivated plant species (Truyens et al., 2014). Microorganisms associated with seeds are not only limited to bacteria and fungi but can include oomycete and viruses (Sastry, 2013; Thines, 2014). There is no strict delineation of microbial lifestyle as mutualist or pathogen, specifically in the seed-microbe interaction as these properties are expressed within a certain situation (Nelson, 2018).

Seeds bacterial microbiota consists of major phyla typically found in soil such as Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Firmicutes, and Bacteroidetes (Barret et al., 2015; Fierer et al., 2012). Bacterial seed endophytes may be highly conserved in certain plant species but can be inconsistent in different host genotypes, seed development from germination to maturation, geographical sites, and the presence of plant pathogens (Nelson, 2018). One of the most predominant fungal seed endophytes belongs to the genus Epichloe and has been found to protect their grass hosts against plant pathogens (Saikkonen et al., 2016). Four classes of ascomycetes (Dothideomycetes, Eurotiomycetes, Leotiomycetes, and Sordariomycetes) and a class of basidiomycete (Tremellomycetes) dominated the Brassicaceae seeds (Barret et al., 2015). Interestingly, some important plant pathogens genera such as Alternaria, Leptosphaeria, Fusarium, Phoma, and Pyrenophora made up most of the Brassica and Triticum seed epiphytic fungal populations (Links et al., 2014). Root exudates secreted below ground can also contribute towards microbial recruitment and infiltration from the soil to the seeds during germination (Adeleke & Babalola, 2021).

Omics technologies have a transformative role in improving seed quality and yield by providing a deeper understanding of plant-microbe interactions. With advanced tools like metagenomics, comprehensive DNA analysis of microbial communities on seeds, in the soil, and within the plant rhizosphere can be made (Fadiji & Babalol, 2020). Metagenomics allows the identification of microbial species associated with healthy seeds and correlates specific microbial communities with improved seed health (Fadiji & Babalola, 2020). Meta-transcriptomics allows RNA analysis and is used to determine which microbial genes are expressed during major plant development phases such as seed germination and seedling establishment (Kimotho & Maina, 2024). This enables a better understanding of which microbial functions are important for seedling vigour. Metabolomics is another approach which can be used to identify key microbial metabolites like phytohormones that influence seed health (Kimotho & Maina, 2024). These integrated data can be used to synthetically engineer more efficient microbial inoculants and biofertilizers, enabling sustainable agricultural practices and enhancing seed quality and yield (Ke et al., 2021).

Omics technologies play a transformative role in improving seed quality and yield by providing deep insights into plant–microbe interactions. Metagenomics has been particularly valuable for uncovering seed-associated microbiomes that promote plant health and resistance to pathogens. For instance, in stored wheat grains, metagenomic profiling identified beneficial bacteria, Bacillus strains that reduced seedborne pathogenic fungal load up to 3.59 log10 CFU/g compared to untreated controls (Solanki et al., 2021). Another strain of yeast, Rhodotorula glutinis isolated from the wheat grains in the same study, was shown to significantly metabolize and reduce the carcinogenic mycotoxin contamination level by up to 65% (Solanki et al., 2021). Likewise, in maize, bio-inoculants harbouring arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and bacteria demonstrated grain yield advantages of 7–15%, highlighting the potential of targeted microbial inoculation strategies (Lahijanian et al., 2025).

Meta-transcriptomics refines these insights by identifying microbial genes actively expressed during critical developmental stages. In wheat, comparative meta-transcriptomic analyses of the rhizosphere microbiomes revealed the largest number of upregulated genes in the non-suppressive soils related to stress, such as detoxifying reactive oxygen species (ROS) and superoxide radicals (sod, cat, ahp, bcp, gpx1, trx), which corresponded to root infection caused by Rhizoctonia solani (Hayden et al., 2018). This approach shifts the focus from identifying microbial presence to uncovering functional activity, offering a clearer picture of microbial roles at early plant growth.

Metabolomics further complements this understanding by characterising bioactive compounds produced by seed- and soil-associated microbes. Key metabolites identified from peanut seedlings inoculated with Trichoderma harzianum, such as indole acetic acid (IAA), ACC synthase, and ACC oxidase, have been shown to stimulate root length and suppress soilborne pathogens (Wang et al., 2024). In addition, metabolomic profiling of soybean–rhizobia symbiosis demonstrated shifts in amino acid and flavonoid composition that contributed to positive readjustment of plant growth in a heavy metal-stressed environment (Preiner et al., 2024).

Finally, multi-omics integration provides a systems-level perspective, linking microbial community composition, functional gene expression, and metabolite production. Such integrative approaches enabled the design of tailored microbial inoculants and biofertilizers, achieving yield gains under disease pressure or environmental stress (Ke et al., 2021). Collectively, these omics-driven strategies are paving the way for sustainable and resilient agriculture by enabling precise manipulation of plant–microbe interactions to enhance seed quality and productivity.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

This review addressed the critical research on omics technologies in advancing our understanding of seed biology, particularly in relation to seed dormancy, germination, stress resistance, and microbiome interactions. The primary objective was to highlight how omics approaches positively affect seed quality and quantity. The review indicates that researchers have gained significant insights into the molecular and biochemical processes underlying seed development and performance by utilising genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, as well as metabolomics, epigenomics, and phenomics technologies. For example, identifying key regulators such as ABA, DOG1, and various resistance genes has provided avenues for improving seed vigour and resilience to biotic and abiotic stresses. Moreover, the recognition of the seed microbiome's role in influencing seed quality and yield highlights the potential for innovative strategies that extend beyond traditional breeding practices. The implications of these findings are profound. They underline the need for omics approaches to improve seed-related traits. Incorporating these approaches could help mitigate some agricultural challenges and promote sustainable farming practices.

Despite progress, challenges persist in comprehending the intricate networks that regulate seed traits and their interactions with environmental factors.

A more holistic, multi-omics approach will be essential to uncover the intricate networks that govern seed biology. Specifically, combining genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics can provide a comprehensive view of the molecular mechanisms involved in seed dormancy, germination, and stress responses. The role of the microbiome in seed health and performance offers an emerging area of exploration, where genomic and proteomic tools could be applied to manipulate microbial communities to benefit plant growth.

The application of CRISPR-Cas technologies to directly modify key genes related to seed vigour, stress resistance, and germination holds great promise, but further research into the functional characterisation of these genes is necessary. Furthermore, long-term studies on the impact of climate change on seed traits and the development of drought and heat-resistant varieties will be critical for future food security. Additionally, integrating high-throughput technologies with large-scale data analytics will allow for more efficient breeding programs and the development of more resilient crop varieties.

Ultimately, continued advancements in omics technologies and their application to seed biology will be vital for developing crops that can thrive in increasingly variable environmental conditions, ensuring sustainable agricultural productivity in the face of global challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Aria Dolatabadian and Mohammad Sayari; writing—original draft preparation, Jake Cummane, Aria Dolatabadian and Maria Lee; writing—review and editing, Jake Cummane, Aria Dolatabadian, William Thomas, Jacqueline Batley and David Edwards; supervision, Aria Dolatabadian and Jacqueline Batley; project administration, Jacqueline Batley; funding acquisition, Jacqueline Batley. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analysed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments). Where GenAI has been used for purposes such as generating text, data, or graphics, or for study design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, please add “During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used [tool name, version information] for the purposes of [description of use]. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.”

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript: DNA – Deoxyribonucleic acid

WGS – Whole genome sequencing

SNP – Single nucleotide Polymorphism

CNV – Copy number variant

PAV – Presence/absence variant

GWAS – Genome-wide association studies

QTL – Quantitative trait loci

QTL-seq – Quantitative trait loci sequencing

MAS – Marker-assisted selection

SSR – Simple sequence repeat

SDN – Site directed nuclease

CWR – Crop wild relatives

RNA – Ribonucleic acid

RT-PCR – Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

DEG – Differentially expressed gene

LC-MS – Liquid chromatography mass spectrometry

GC-MS – Gas chromatography mass spectrometry

MS – Mass spectrometry

DOG – Delay of Germination

GA – Gibberellic acid

References

- Adeleke, B.S.; Babalola, O.O. The endosphere microbial communities, a great promise in agriculture. International Microbiology 2021, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Sielaff, M.; Distler, U.; Schuppan, D.; Tenzer, S.; Longin, C.F.H. Reference proteomes of five wheat species as starting point for future design of cultivars with lower allergenic potential. npj Science of Food 2023, 7, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Kapoor, S.; Tyagi, A.K. Transcription factors regulating the progression of monocot and dicot seed development. Bioessays: News and Reviews in Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology 2011, 33, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnolucci, P.; Rapti, C.; Alexander, P.; De Lipsis, V.; Holland, R.A.; Eigenbrod, F.; Ekins, P. Impacts of rising temperatures and farm management practices on global yields of 18 crops. Nature Food 2020, 1, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Munawar, N.; Khan, Z.; Qusmani, A.T.; Khan, S.H.; Jamil, A.; Ashraf, S.; et al. An Outlook on Global Regulatory Landscape for Genome-Edited Crops. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, P.; Abdel Latef, A.A.H.; Rasool, S.; Akram, N.A.; Ashraf, M.; Gucel, S. Role of proteomics in crop stress tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016, 7, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpertey, A.; Singh, R.J.; Diers, B.W.; Graef, G.L.; Mian, M.A.R.; Shannon, J.G.; Scaboo, A.M.; et al. Genetic Introgression from Glycine tomentella to Soybean to Increase Seed Yield. Crop science 2018, 58, 1277–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleem, M.; Razzaq, M.K.; Aleem, M.; Yan, W.; Sharif, I.; Siddiqui, M.H.; Aleem, S.; et al. Genome-wide association study provides new insight into the underlying mechanism of drought tolerance during seed germination stage in soybean. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 20765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amas, J.C.; Bayer, P.E.; Hong Tan, W.; Tirnaz, S.; Thomas, W.J.W.; Edwards, D.; Batley, J. Comparative pangenome analyses provide insights into the evolution of Brassica rapa resistance gene analogues (RGAs). Plant Biotechnology Journal 2023, 21, 2100–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angon, P.B.; Mondal, S.; Akter, S.; Sakil Md, A.; Jalil Md, A. Roles of CRISPR to mitigate drought and salinity stresses on plants. Plant Stress 2023, 8, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, B.; van der Horst, S.; Cordewener, J.H.G.; America, T.A.H.P.; Hanson, J.; Bentsink, L. Seed-Stored mRNAs that Are Specifically Associated to Monosomes Are Translationally Regulated during Germination. Plant Physiology 2020, 182, 378–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailly, C.; Gomez Roldan, M.V. Impact of climate perturbations on seeds and seed quality for global agriculture. The Biochemical Journal 2023, 480, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balouchi, H.; Soltani Khankahdani, V.; Moradi, A.; Gholamhoseini, M.; Piri, R.; Heydari, S.Z.; Dedicova, B. Seed Fatty Acid Changes Germination Response to Temperature and Water Potentials in Six Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) Cultivars: Estimating the Cardinal Temperatures. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barret, M.; Briand, M.; Bonneau, S.; Préveaux, A.; Valière, S.; Bouchez, O.; Hunault, G.; et al. Emergence shapes the structure of the seed microbiota. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2015, 81, 1257–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, K.; Hasan, N.; Shammi, M. Selective biotic stressors’ action on seed germination: A review. Plant Science 2024, 346, 112156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, N.; Qin, C.; Ahanger, M.A.; Raza, S.; Khan, M.I.; Ashraf, M.; Ahmed, N.; et al. Role of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in plant growth regulation: implications in abiotic stress tolerance. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019, 10, 1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentsink, L.; Jowett, J.; Hanhart, C.J.; Koornneef, M. Cloning of DOG1, a quantitative trait locus controlling seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2006, 103, 17042–17047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhardwaj, A.; Devi, P.; Chaudhary, S.; Rani, A.; Jha, U.C.; Kumar, S.; Bindumadhava, H.; et al. “Omics” approaches in developing combined drought and heat tolerance in food crops. Plant Cell Reports 2022, 41, 699–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolingue, W.; Rosnoblet, C.; Leprince, O.; Vu, B.L.; Aubry, C.; Buitink, J. The MtSNF4b subunit of the sucrose non-fermenting-related kinase complex connects after-ripening and constitutive defense responses in seeds of Medicago truncatula. The Plant Journal 2010, 61, 792–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourgeois, M.; Jacquin, F.; Savois, V.; Sommerer, N.; Labas, V.; Henry, C.; Burstin, J. Dissecting the proteome of pea mature seeds reveals the phenotypic plasticity of seed protein composition. Proteomics 2009, 9, 254–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocklehurst, P.A.; Fraser, R.S.S. Ribosomal RNA integrity and rate of seed germination. Planta 1980, 148, 417–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brozynska, M.; Furtado, A.; Henry, R.J. Genomics of crop wild relatives: expanding the gene pool for crop improvement. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2016, 14, 1070–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchmann, J.P.; Holmes, E.C. Cell walls and the convergent evolution of the viral envelope. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2015, 79, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, M.T.; Hu, H.; Yeats, T.H.; Caffe-Treml, M.; Gutiérrez, L.; Smith, K.P.; Sorrells, M.E.; et al. Translating insights from the seed metabolome into improved prediction for lipid-composition traits in oat (Avena sativa L.). Genetics 2021, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.-X.; Fu, H.; Gao, J.-D.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Huang, W.-J.; Chen, Z.-J.; Qi-Zhang et, a.l. Identification of metabolomic biomarkers of seed vigor and aging in hybrid rice. Rice (New York, N.Y.) 2022, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Arora, R.; Arora, U. Osmopriming of spinach (Spinacia oleracea L. cv. Bloomsdale) seeds and germination performance under temperature and water stress. Seed Science and Technology 2010, 38, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Liu, J.; Cheng, H.; Li, C.; Fu, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, H.; et al. A lignified-layer bridge controlled by a single recessive gene is associated with high pod-shatter resistance in Brassica napus L. The Crop journal 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- collection, handling, storage and pre-treatment of Prosopis seeds in Latin America. (n.d.). . Retrieved June 24, 2025, from https://www.fao.org/4/q2180e/Q2180E00.htm#TOC.

- Crop loss/waste on Australian horticulture farms, 2023–2024 - DAFF. (n.d.). . Retrieved September 20, 2025, from https://www.agriculture.gov.au/abares/research-topics/surveys/horticulture-crop-loss-23-24.

- Das, S.S.; Karmakar, P.; Nandi, A.K.; Sanan-Mishra, N. Small RNA mediated regulation of seed germination. Frontiers in Plant Science 2015, 6, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobiesz, M.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.I. Proteins in Relation to Vigor and Viability of White Lupin (Lupinus albus L.) Seed Stored for 26 Years. Frontiers in Plant Science 2017, 8, 1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolatabadian, A.; Bayer, P.E.; Tirnaz, S.; Hurgobin, B.; Edwards, D.; Batley, J. Characterization of disease resistance genes in the Brassica napus pangenome reveals significant structural variation. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2020, 18, 969–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domergue, J.-B.; Lalande, J.; Beucher, D.; Satour, P.; Abadie, C.; Limami, A.M.; Tcherkez, G. Experimental Evidence for Seed Metabolic Allometry in Barrel Medic (Medicago truncatula Gaertn.). International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, J.; Wang, B.-H.; Liu, B.-L.; Wang, Y.-Z. Pod shattering resistance associated with domestication is mediated by a NAC gene in soybean. Nature Communications 2014, 5, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.L.; Spillane, C.; Lopez, F.; Ayele, B.T.; Ortiz, R. First the seed: Genomic advances in seed science for improved crop productivity and food security. Crop science 2021, 61, 1501–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Maarouf-Bouteau, H. The seed and the metabolism regulation. Biology 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estimating crop yield | Agriculture and Food. (n.d.). . Retrieved December 17, 2024, from https://www.agric.wa.gov.au/mycrop/estimating-crop-yield.

- Fadiji, A.E.; Babalola, O.O. Metagenomics methods for the study of plant-associated microbial communities: A review. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2020, 170, 105860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fait, A.; Angelovici, R.; Less, H.; Ohad, I.; Urbanczyk-Wochniak, E.; Fernie, A.R.; Galili, G. Arabidopsis seed development and germination is associated with temporally distinct metabolic switches. Plant Physiology 2006, 142, 839–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faryad, A.; Aziz, F.; Tahir, J.; Kousar, M.; Qasim, M.; Shamim, A. Integration of OMICS technologies for crop improvement. Protein and Peptide Letters 2021, 28, 896–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernie, A.R.; Yan, J. De Novo Domestication: An Alternative Route toward New Crops for the Future. Molecular Plant 2019, 12, 615–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fierer, N.; Leff, J.W.; Adams, B.J.; Nielsen, U.N.; Bates, S.T.; Lauber, C.L.; Owens, S.; et al. Cross-biome metagenomic analyses of soil microbial communities and their functional attributes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109, 21390–21395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finch-Savage, W.E.; Bassel, G.W. Seed vigour and crop establishment: extending performance beyond adaptation. Journal of Experimental Botany 2016, 67, 567–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flint-Garcia, S.A.; Bodnar, A.L.; Scott, M.P. Wide variability in kernel composition, seed characteristics, and zein profiles among diverse maize inbreds, landraces, and teosinte. TAG. Theoretical and Applied Genetics. Theoretische und Angewandte Genetik 2009, 119, 1129–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, R.; Taylor, J.M.; Shirasawa, S.; Peacock, W.J.; Dennis, E.S. Heterosis of Arabidopsis hybrids between C24 and Col is associated with increased photosynthesis capacity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2012, 109, 7109–7114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, D.; Trijatmiko, K.R.; Tagle, A.G.; Sapasap, M.V.; Koide, Y.; Sasaki, K.; Tsakirpaloglou, N.; et al. NAL1 allele from a rice landrace greatly increases yield in modern indica cultivars. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013, 110, 20431–20436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]