1. Introduction

Heavy metals are hazardous environmental pollutants. Cadmium, lead and thallium are the most hazardous to human health and the environment due to their toxicity, cancer-causing potential and accumulation in food chains [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The main sources of their entry into the environment are associated with the entry of nano- and microparticles into the atmosphere during the development of ore deposits, the operation of metallurgical enterprises, as a result of industrial and automobile emissions, the combustion of coal and oil, and many other ways. According to [

1,

3,

6,

7,

8], particles up to 2-3 µm in size predominate in the atmosphere. Solid particles of this size are the most hazardous to living organisms. According to WHO [

9], in most areas of Europe PM

2.5, i.e. particles up to about 2.5 µm in size, make up 50-70% of PM

10 particles. It is important to note that 3% of deaths from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases and 5% of deaths from lung cancer are associated with PM

2.5. Toxic metals play a key role in this. The hazard of microparticles of toxic metals is associated not only and not so much with their small size and the permeability of membranes of organisms for them. A significantly greater hazard is associated with their toxicity. Due to their small size, they can remain suspended in the atmosphere for a long time and, thus, travel long distances. Water (sea, natural springs, reservoirs, etc.) is a virtually obligatory intermediate link in their subsequent distribution in the natural environment. It is in water that metals oxidize and in the form of ions and compounds then enter the soil and organisms. Therefore, it is important to study the properties of cadmium, lead and thallium microparticles and their solubility in water. This is difficult due to their high chemical activity, the need to develop special methods for obtaining particles of the desired size and protective measures when working with them. Earlier, we developed a radiation-chemical method for obtaining nano- and microparticles of cadmium [

10,

11]. We found that aqueous dispersions of cadmium microparticles of 2–3 μm in size are unstable. They quickly oxidize in air and dissolve in water of various compositions and origins.

This work continues the study of microparticles of toxic metals. Its goal is to compare the chemical activity of cadmium, lead and thallium in their ability to dissolve in water and the influence of various environmental factors (air, pH, ions, etc.) on this process.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

The chemicals used in the study were of high analytical quality and were used without additional purification. The following chemicals were used: 3CdSO4·8H2O (extra pure), Pb(ClO4)2 (Acros Organics, Belgium), Tl2SO4 (extra pure); 2- propanol (CH3)2CHOH (99.8 %, EKOS-1, Russia), and hydrochloric acid HCl (extra pure, EKOS-1, Russia), NaOH (99.9 %, Khimmed, Russia), Na2CO3 (99.9 %, Khimmed, Russia). The solutions were prepared using triple-distilled water.

2.2. Preparation of Metal Dispersions

The following methods and installations were used in the experiments. The solutions were irradiated using a LINS-02-500 linear accelerator (RadiaBeam Technologies, Santa Monica, CA, USA). The monochromatic radiation energy was 2 MeV, the pulse length was 4 μs, and the pulse frequency was 50 Hz. The absorbed dose rate was measured with an iron sulfate dosimeter. The absorbed dose varied from 10 to 100 kGy.

Solutions of cadmium, lead or thallium salts which also contained 2-propanol, were irradiated with accelerated electrons in a closed glass vessel. The irradiation was performed in 30 cm3 glass test tubes of 3 × 9.5 cm size and in flat cells 1 cm thick and 4.5 cm in diameter with a volume of 10 mL. Prior to irradiation, the solutions were degassed by freezing–pumping–thawing. The vessel carried a sidearm with an optical quartz cuvette. Another sidearm carried a septum. Optical spectra or dynamic light scattering could therefore be measured and substances be added via a syringe without exposure of the solutions to air.

2.3. Study of Characteristics of Metal Particles

The UV spectra were recorded with a Cary 100 spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, USA) using 1 and 0.5 cm thick quartz cells. The hydrodynamic size of the resulting metal nanoparticles was determined with a Delsa Nano C device (Beckman Coulter, USA) by photon correlation spectroscopy using a laser with a wavelength of 658 nm; the scattering angle was 160°.

The photographs of the surface of deposited metals and colloidal particles were taken with a Revelation III (model R3M-BN4A-DAL3) binocular microscope (LW Scientific, USA). The images were processed using the ScopePhoto 3.0 and ImageJ 22H2 (ensamble OC 190.45.4780) programs. After irradiation of the deaerated solutions, the metal microparticles were examined using microscopy. They were first examined at the bottom of the optical cell without air access. Then air was passed through to evaluate the changes. The oxidative dissolution of the particles was analyzed by applying drops of the dispersion to glass. The entire preparation process, including the application of the drops, took about one minute before the measurements began.

The SEM images were taken with a KYKY-EM6900 scanning electron microscope equipped with a thermoemission tungsten cathode. The device allowed taking SEM images and performing elemental mapping by energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy in the real time. The resolution was 3 nm at 30 kV. The accelerating voltage was from 0 to 30 kV.

The reduction of metal ions (Cd

2+, Pb

2+ or Tl

+) occurs by the radicals which are generated by irradiation of aqueous solutions. The radiolysis leads to the uniform generation of radical and ionic species throughout the volume: hydrated electrons (e

–aq), hydrogen atoms (H

•), and hydroxyl radicals (

•OH); their radiation-chemical yields are

G(e

aq–) = 0.27,

G(H

•) = 0.06, and

G(

•OH) = 0.28 µmol J

–1 [

12,

13]. The

•OH radical and H

• atom enter into the dehydrogenation reaction with 2-propylol:

In this conditions only reducing species are formed: e

aq– (E

0 = −2.87 V) and (CH

3)

2•COH (E

0 = -1.34 V) respectively [

14,

15]. In this case, the action of accelerated electrons on an aqueous solution containing metal ions initiates their reduction to form a metal [

16]. Comparison of the reduction potentials of these radical species with the electrode potentials of the metals under study (-0.403 V, −0.126 V and –0.336 V for pairs Cd

2+/Cd

0, Pb

2+/Pb

0 and Tl

+/Tl

0, respectively) shows that the reduction of their ions in water is thermodynamically possible. The results of the studies confirm this. The total concentration of reducing species in this case formed at an absorbed dose of 1 kGy is approximately 6 × 10

–4 mol L

–1 kGy

–1. Schematically, the reduction process using cadmium as an example can be expressed by the following reactions:

As a result, aqueous dispersions of the metals being studied are formed. According to reactions 2 and 3, the concentrations of Cd0 and Pb0 atoms formed at an absorbed dose of 1 kGy should be expected to be ~3 × 10–4 mol L–1 kGy–1, and for Tl0 atoms the concentration should be twice as high.

The studies showed that the radiation-chemical method is suitable for obtaining aqueous dispersions of cadmium, lead and thallium. The main fraction of particles corresponded to PM

2.5—that is, did not exceed 2.5 μm in diameter. Such particles predominate in the air of large cities [

1,

3,

6,

7,

8,

9].

3. Results

3.1. Formation and Characteristics of the Metal Dispersions in Water

Deaerated aqueous solutions of Cd, Pb and Tl salts containing 2-propanol acquire a grey-brown color after irradiation, which is caused by the formed metal particles.

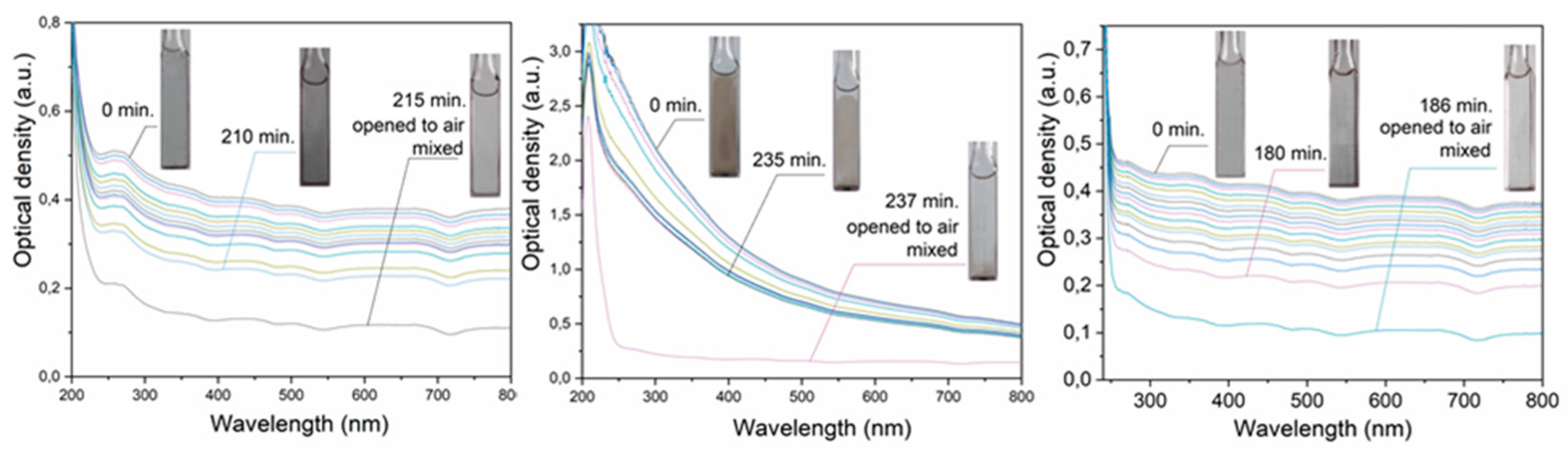

Figure 1 illustrates the optical spectra of aqueous dispersions. In the case of cadmium and thallium, a spectrum without pronounced maxima in the UV and Vis regions is observed. Such a flat optical spectrum is caused by the scattering and reflection of light by the formed metal particles, the size of which is comparable (d≥0.1λ) or exceeds the wavelength of light (the so-called diffuse transmittance) [

17]. In the case of lead, a spectrum increasing in the UV region is observed, caused by the superposition of an additional absorption band of plasmons in this metal on the diffuse transmittance spectrum. It is known that lead nanoparticles have an absorption band at 218 nm with a molar absorption coefficient of 3.2 × 10

4 mol L

-1 cm

-1 induced by a surface plasmon oscillation [

18].

The optical density of the plasmon band (

Figure 1a) and the molar absorption coefficient allow us to calculate the concentration of Pb

0 atoms in the form of nanoparticles. This is approximately 1-2% of the total metal concentration in the dispersion. With an increase in the concentration of Pb

0 atoms, the relative intensity of the plasmon band of nanoparticles decreases due to their aggregation. Addition of CO

32- and SO

42- anions to an aqueous lead dispersion immediately leads to the disappearance of the plasmon band. This occurs due to the sorption of anions, which neutralizes the charge of the metal core of colloidal particles. The stabilizing double electric layer is destroyed, the nanoparticles lose stability and aggregate. The spectrum becomes similar to that observed for cadmium and thallium dispersions.

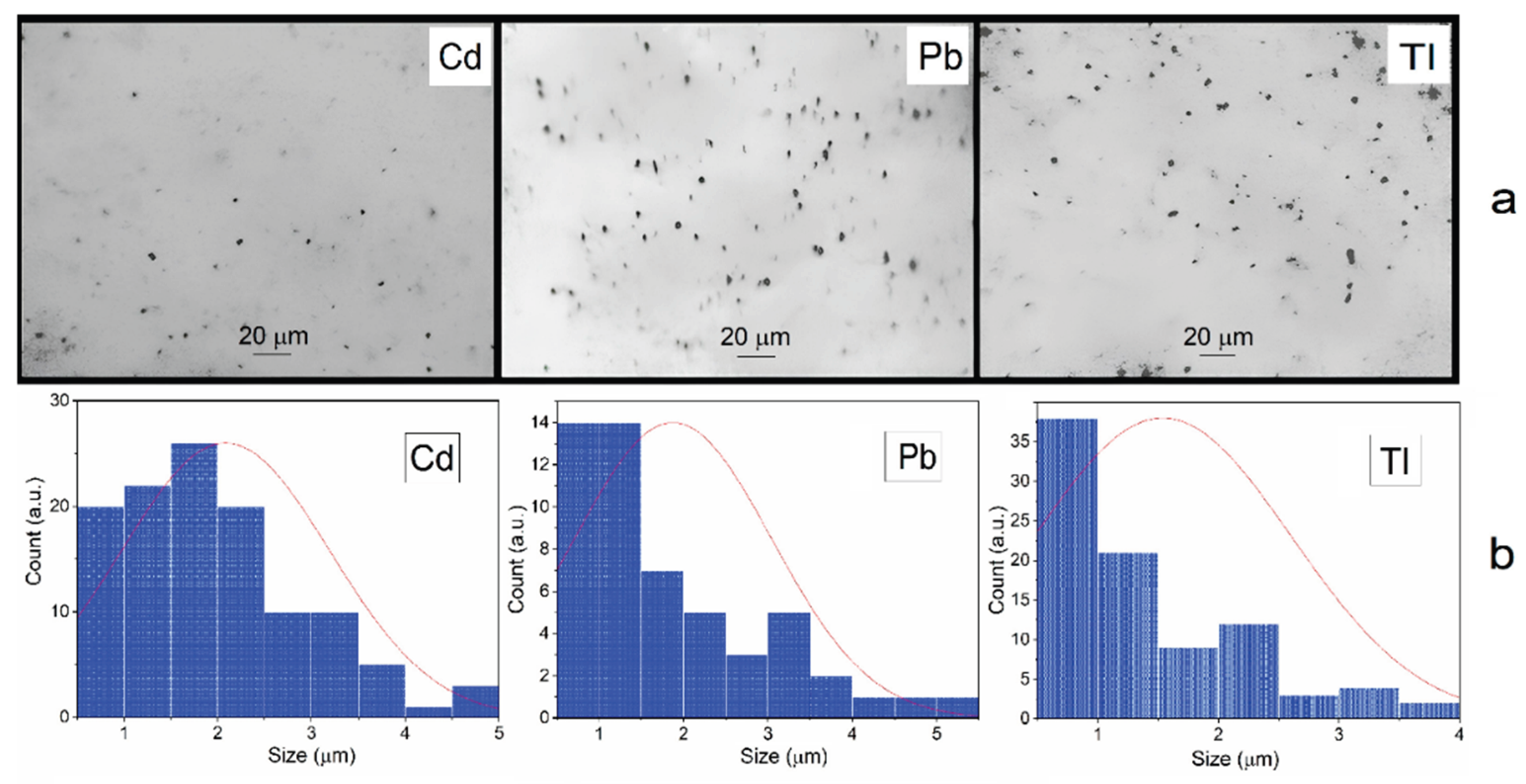

The size of the metal particles formed in deaerated solutions after irradiation is 2.3±0.1 m, 2.0±0.1 m and 1.8±0.1 μm for Cd, Pb, and Tl dispersions respectively (

Figure 2). The mean mass concentration of PM

2.5 fraction, particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 μm or less, is 80% or more. That is, by their size they correspond to the main fraction of toxic metals present in the polluted air environment of megacities [

1,

2,

3,

6,

7,

8,

9].

Metal dispersions are unstable (

Figure 1a). Over time, the particles stick together and settle. Sedimentation makes the solutions more transparent.

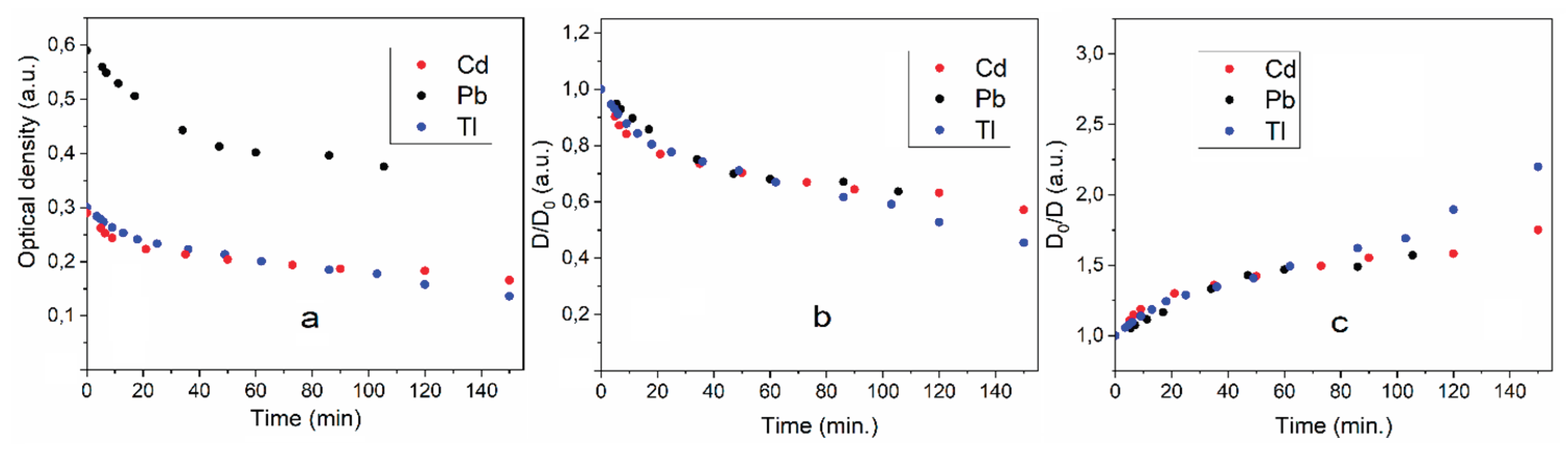

Figure 3 shows how the optical density of the dispersions decreases over time. There are two stages of optical density reduction. The first occurs quickly, within 50–70 minutes. The second lasts for several hours. These two stages are clearly revealed if the dependence of the change in optical density on time is expressed in coordinates D

t/D

0 and D

0/D

t. The D

t/D

0 coordinates reflect the change in turbidity, and the D

0/D

t coordinates reflect the change in transparency. These dependences are shown in

Figure 3b,c.

It can be seen that the change in optical density over time in the fast region is the same for dispersions of cadmium, lead and thallium. It can be assumed that the change in optical density here is due to the agglomeration of the formed metal particles. The slow sections are approximately the same for lead and thallium. However, for cadmium the turbidity decreases more slowly and, accordingly, the dispersion also becomes clearer more slowly. Complete clarification of the dispersion and the release of the metal into the sediment takes almost a day. Dispersions of all the metals studied quickly dissolve when exposed to air (

Figure 1a).

Sedimentation of metal microparticles under the action of gravity occurs in the laminar region, where Stokes’ law applies [

19]. The settling velocity of cadmium particles of 2-3 μm in size, as measured by the change in suspension turbidity, is about 1.3×10⁻⁵ m s

-1 [

11]. This value agrees well with the calculated value for spherical particles — 6.7×10⁻⁶ m s

-1. Considering that the calculations were carried out for a monodisperse system, the results of the experiments and theoretical calculations can be considered satisfactory.

In our studies, the characteristics of cadmium, lead and thallium solutions were the same and did not change, and the particle sizes were also approximately the same. According to Stokes’ law [

19], differences in the settling velocities of microparticles of these metals can be explained by the difference in their specific masses. For cadmium, lead and thallium they are 8.7 g cm

-3, 11.3 g cm

-3 and 11.8 g cm

-3 respectively [

20]. The mass ratio of lead and thallium to cadmium suggests that their sedimentation rate should be 35-40% higher than that of cadmium. This roughly corresponds to the changes in the optical densities of solutions of these metals over time (

Figure 3).

Increasing the concentration of metals increases the particle size and accelerates their sedimentation [

10,

11]. However, in this paper we will focus on the PM

2.5 particle fraction. They constitute a significant part of the atmospheric pollution with toxic metals. The study showed that Cd, Pb and Tl microparticles in deaerated water are stable. Mixing the sediment returns the system to a dispersed state, and subsequent storage is accompanied by sediment formation. Microscopy revealed particle aggregation over time. Microparticles are not dissolved and retain their size and shape during long-term storage without air. However, they quickly dissolve in the presence of air.

3.2. Oxidative Dissolution of the Metal Microparticles in Water

As already mentioned, cloudy-gray aqueous dispersions of cadmium, lead and thallium become transparent after a few minutes of saturation with air and mixing (

Figure 1a). This is due to the oxidative dissolution of microparticles.

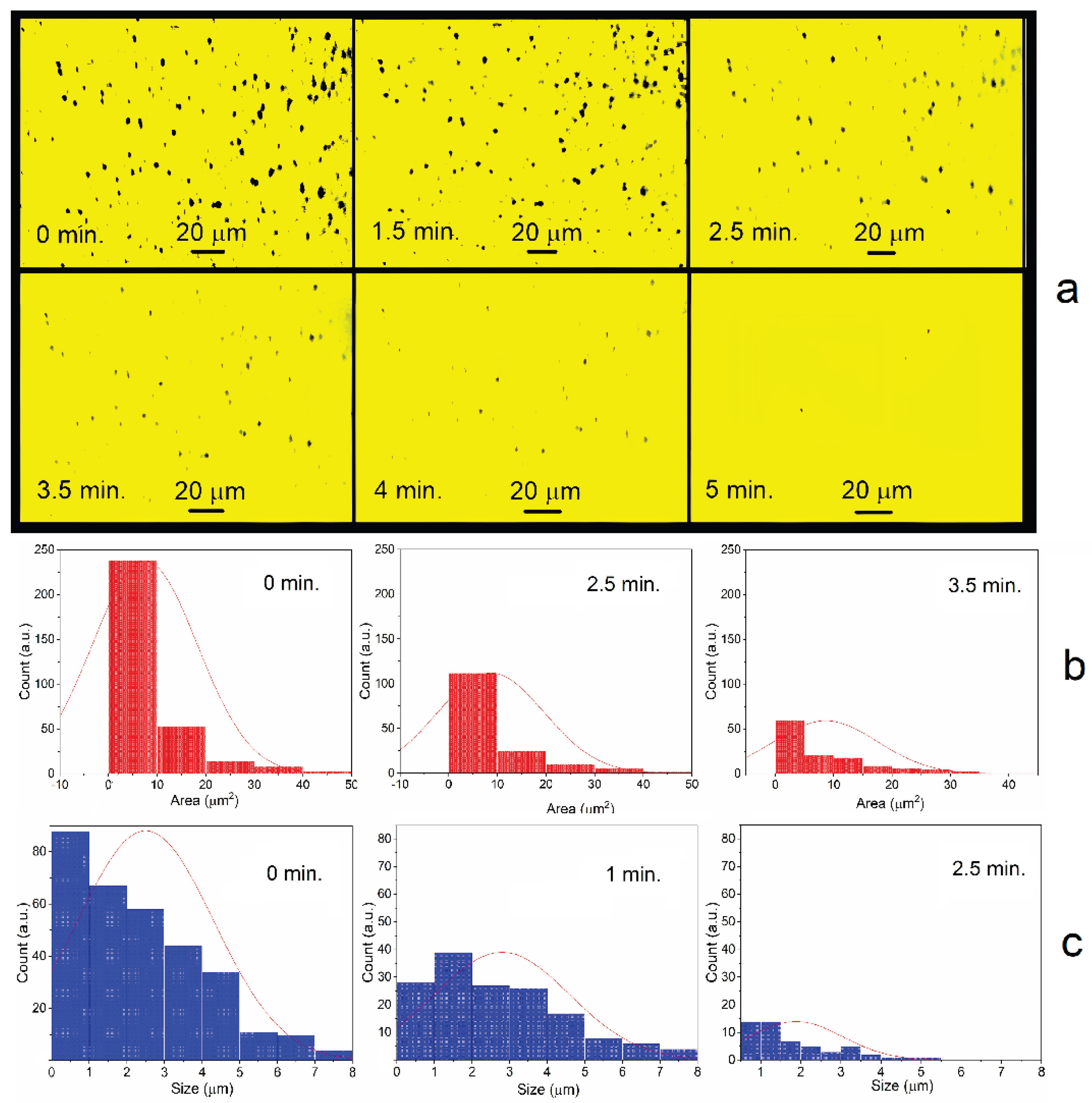

Figure 4 shows this process in dynamics on the glass surface in several drops of lead dispersion. The sizes and areas of microparticles were recorded by photomicroscopy along their contours. Deaerated drops of the solution were applied to a glass plate in air. The first measurement was taken after about one minute.

Figure 4 shows that the metal microparticles disappear and decrease in size in about 4-5 minutes. Small particles disappear first, while large ones decrease in size. The average particle diameter is 2.3±0.3 nm. The particle size distribution changes noticeably only at the last stage of dissolution. This is probably due to the fact that the disappearance of small particles is compensated by the appearance of new ones of the same size due to the dissolution of large particles.

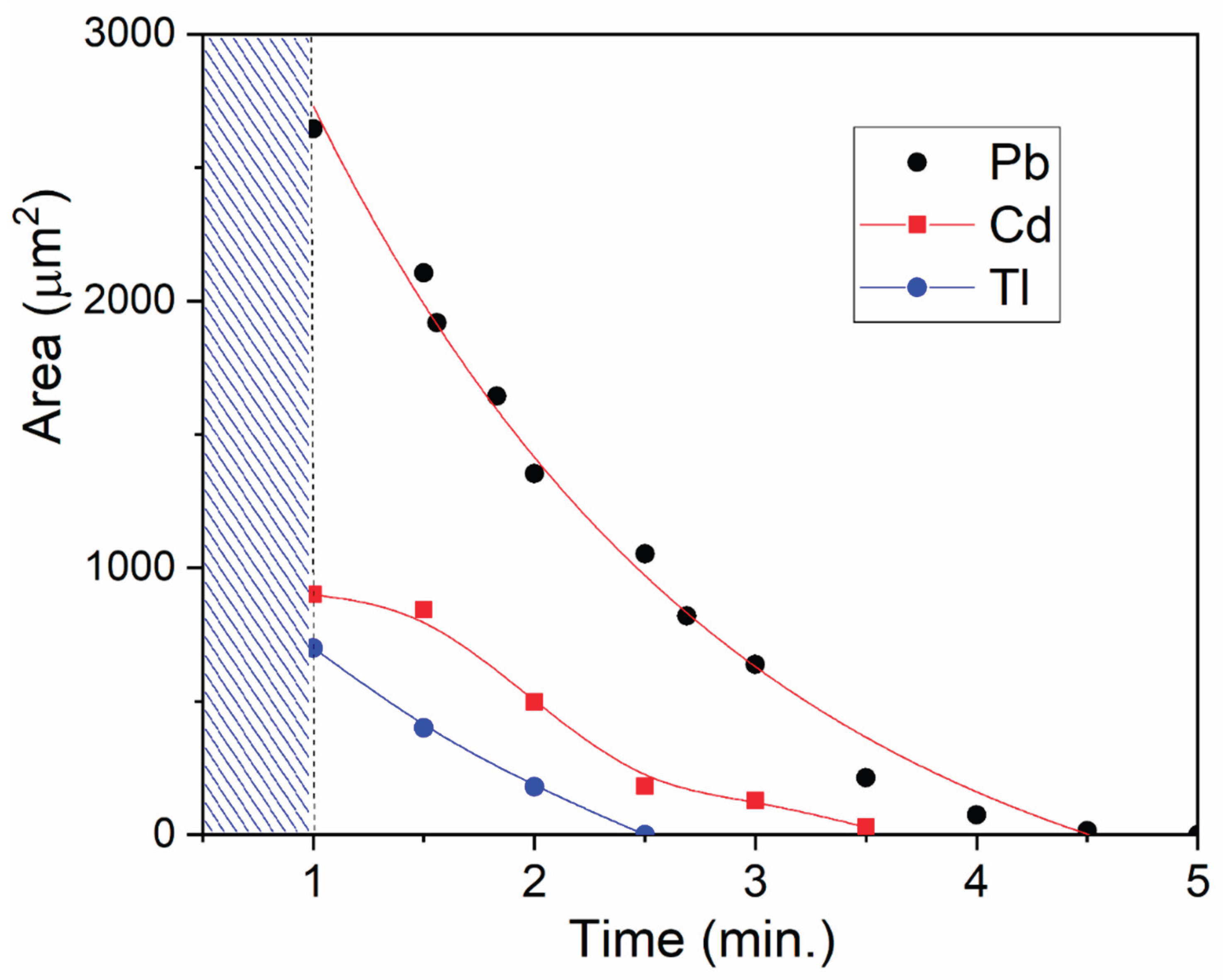

The dynamics of cadmium and thallium dissolution resembles the process of lead dissolution. First, small particles disappear, then large one’s dissolve (

Supplement 1). However, there is an important difference: the dissolution rate increases in the series lead – cadmium – thallium. The concentrations of metals in deaerated solutions were approximately the same immediately after their preparation (

Figure 1a). But by the time of the first measurement, the total surface area for cadmium was 3–4 times smaller than for lead, and for thallium, almost 10 times smaller (

Figure 5). After one minute of cadmium and thallium dispersions being in the air, their concentrations significantly decreased compared to lead. Dissolution of these metals also occurs more quickly. The subsequent dissolution of lead takes about 5–6 minutes, cadmium – 2–3 minutes, and thallium – about 1.5 minutes.

It can be concluded that most of the cadmium and especially thallium microparticles dissolved within one minute of exposure to air even before the microscopy was started. No direct relationship between the rate of oxidative dissolution of metals and the values of their electrode potentials (-0.403 V, −0.126 V and –0.336 V for pairs Cd

2+/Cd

0, Pb

2+/Pb

0 and Tl

+/Tl

0, respectively [

20]) is found here. The rate is probably affected by the formation of a protective oxide film and its subsequent relatively slow dissolution. Indeed, TlOH is highly soluble (34.3 g in 100 ml of water), while Cd(OH)

2 is poorly soluble (0.0015 g) and Pb(OH)

2 is even less soluble (0.00012 g) [

20]. It has been found that the acidity of water accelerates the dissolution of metals, while alkalinity, on the contrary, slows down this process.

Dissolution of cadmium, lead and thallium is activated in the presence of air. The standard reduction potential of the reaction O

2 + 4H

+ + 4 e

- ⇌ 2H

2O is 1.229 V [

20]. The electromotive force of the oxidation reaction of metals ΔE = E(O

2/H

2O) - E(M

n+/M

s) is 1.632 V for cadmium, 1.355 V for lead and 1.565 V for thallium, respectively. Such a large EMF favors its active course, i.e. oxidation of metals. During oxidation, metal hydroxides are formed at the initial stage - poorly soluble Cd(OH)

2 and Pb(OH)

2. A protective film is formed, hindering the development of the corrosion process of their dissolution. The role of the acid is that it dissolves the hydroxides and, thus, favors oxidative dissolution. Then the stoichiometry of oxidative dissolution of Cd and Pb can be written as follows:

In the case of thallium, soluble TlOH does not hinder the corrosion of the metal and therefore its dissolution rate is the highest.

The oxidative dissolution of cadmium, lead and thallium, conductive materials, in an electrolyte, which is water, occurs by an electrochemical mechanism. This mechanism underlies the corrosion of metals and their dissolution.

4. Conclusions

In a polluted atmosphere, ultrafine particles of 2-3 μm and smaller (PM2.5) predominate. They pose a severe threat to bioorganisms, as they contain toxic metals. These metals can remain in the air for a long time and be transported over long distances. Water becomes an intermediate link in which they transform into ionic form and spread further. Getting into food chains, they accumulate in organisms, causing hazardous diseases. The study showed that in an ultrafine state, cadmium, lead and thallium have high chemical activity. In the presence of air, metal microparticles dissolve in water in a few minutes, transforming into ionic form, which is most hazardous for the environment. The dissolution rate increases in the following order: Pb-Cd-Tl. Studying the properties of heavy metal microparticles is important for assessing their migration in the environment, health risks and developing methods for preventing pollution.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: Micrographs of Cd microparticles on the glass surface (a), changes in their area (b) and size (c) over time. Magnification ×1000. Average particle sizes 2.2±0.1 m (0 min.); 2.0±0.1 m (1 min.) and 1.8±0.1 μm (2.5 min.); Figure S2: Micrographs of Tl microparticles in the volume of liquid (a), changes in their area (b) and size (c) over time. Magnification ×1000. Average particle sizes 2.5±0.1 m (0 min.); 2.2±0.1 m (1.5 min.) and 1.7±0.1 μm (2 min.)

Author Contributions

Gennadii L. Bykov data curation, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, writing review & editing; Boris G. Ershov conceptualization, formalanalysis, methodology, writing- review & editing. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

References

- Yuanguan Gao, Cha, Zhichun, Xi Zhang, Kai Zhang, Guanhua Zhou, Sichu Sun, Yuanguan Gao, and Haiyan Liu. Atmospheric Heavy Metal Pollution Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment Across Various Type of Cities in China. Toxics. 2025, 13, 220. [CrossRef]

- Balali-Mood, M., Naseri, K., Tahergorabi, Z., Khazdair, M.R., Sadeghi, M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12. [CrossRef]

- Popoola, L.T., Adebanjo, S.A., Adeoye, B.K. Assessment of atmospheric particulate matter and heavy metals: a critical review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 15, 935–948. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P.B., Yedjou, C.G., Patlolla, A.K., Sutton, D.J. Heavy Metal Toxicity and the Environment. 2012, 133–164. [CrossRef]

- Cai, K., Yu, Y., Zhang, M., Kim, K. Concentration, Source, and Total Health Risks of Cadmium in Multiple Media in Densely Populated Areas, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019, 16, 2269. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.R.W. and R.M. Cadmium in the atmosphere. Experientia. 1984, 40, 29–36. [CrossRef]

- Sa’adeh, H., Chiari, M., Pollastri, S., Aquilanti, G. Quantification and speciation of lead in air particulate matter collected from an urban area in Amman, Jordan. Nucl. Instruments Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. with Mater. Atoms. 2023, 539, 108–112. [CrossRef]

- 8 Pakkanen, T.A., Kerminen, V.-M., Korhonen, C.H., Hillamo, R.E., Aarnio, P., Koskentalo, T., Maenhaut, W. Urban and rural ultrafine (PM0.1) particles in the Helsinki area. Atmos. Environ. 2001, 35, 4593–4607. [CrossRef]

- Convention on Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution [web site]. Geneva, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. 27 October 2012. https://doi.org/http://www.unece.org/env/lrtap/, accessed.

- Bykov, G.L., Bludenko, A.V., Ponomarev, A.V., Ershov, B.G. Dynamics of metal formation upon radiation-chemical reduction of Cd2+ ions in aqueous solutions: Morphology of cadmium precipitate. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2024, 225, 112115. [CrossRef]

- Bykov, G.L., Ershov, B.G. Effect of Oxygen and Solution Composition on the Oxidative Dissolution of Cadmium Microparticles in Water. ACS ES&T Water. 2024, 4, 5669–5677. [CrossRef]

- Spinks J.W.T., Woods R.J., 1990. An Introduction to Radiation Chemistry. Wiley-Interscience, 1990.

- Ershov, B.G., Gordeev, A.V. A model for radiolysis of water and aqueous solutions of H2, H2O2 and O2. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2008, 77, 928–935. [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, H.A., Dodson, R.W. Reduction potentials of CO2- and the alcohol radicals. J. Phys. Chem. 1989, 93, 409–414. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, D.A., Huie, R.E., Koppenol, W.H., Lymar, S. V., Merényi, G., Neta, P., Ruscic, B., Stanbury, D.M., Steenken, S., Wardman, P. Standard electrode potentials involving radicals in aqueous solution: inorganic radicals (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1139–1150. [CrossRef]

- Ershov, B.G., Bykov, G.L. Formation of porous metals upon radiation chemical reduction of Cd2+ and Pb2+ ions in aqueous solution in the presence of formate ions. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2022, 201, 110460. [CrossRef]

- Bohren, C.F., Huffman, D.R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. 1998. Wiley. [CrossRef]

- Henglein, A. Chemisorption Effects on Colloidal Lead Nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 1999, 103, 9302–9305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, A. Transport and Deposition of Particles in Turbulent and Laminar Flow. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2008, 40, 311–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.M., Lide, D.R., Bruno, T.J. (Eds.), 2016. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. CRC Press. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).