Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

22 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Setup

2.2. Data preprocessing

2.3. Accuracy metrics

2.4. Machine Learning Implementation

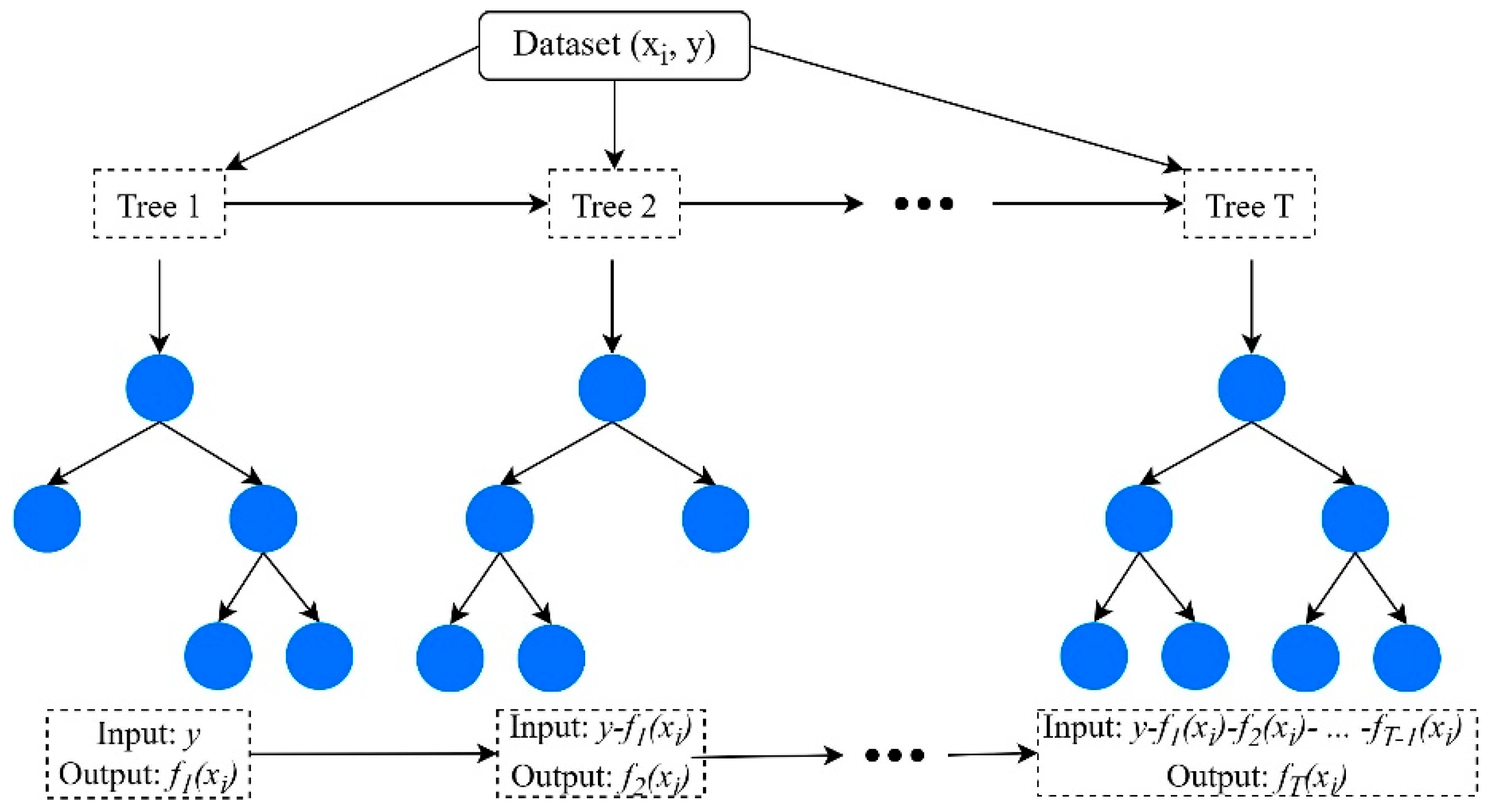

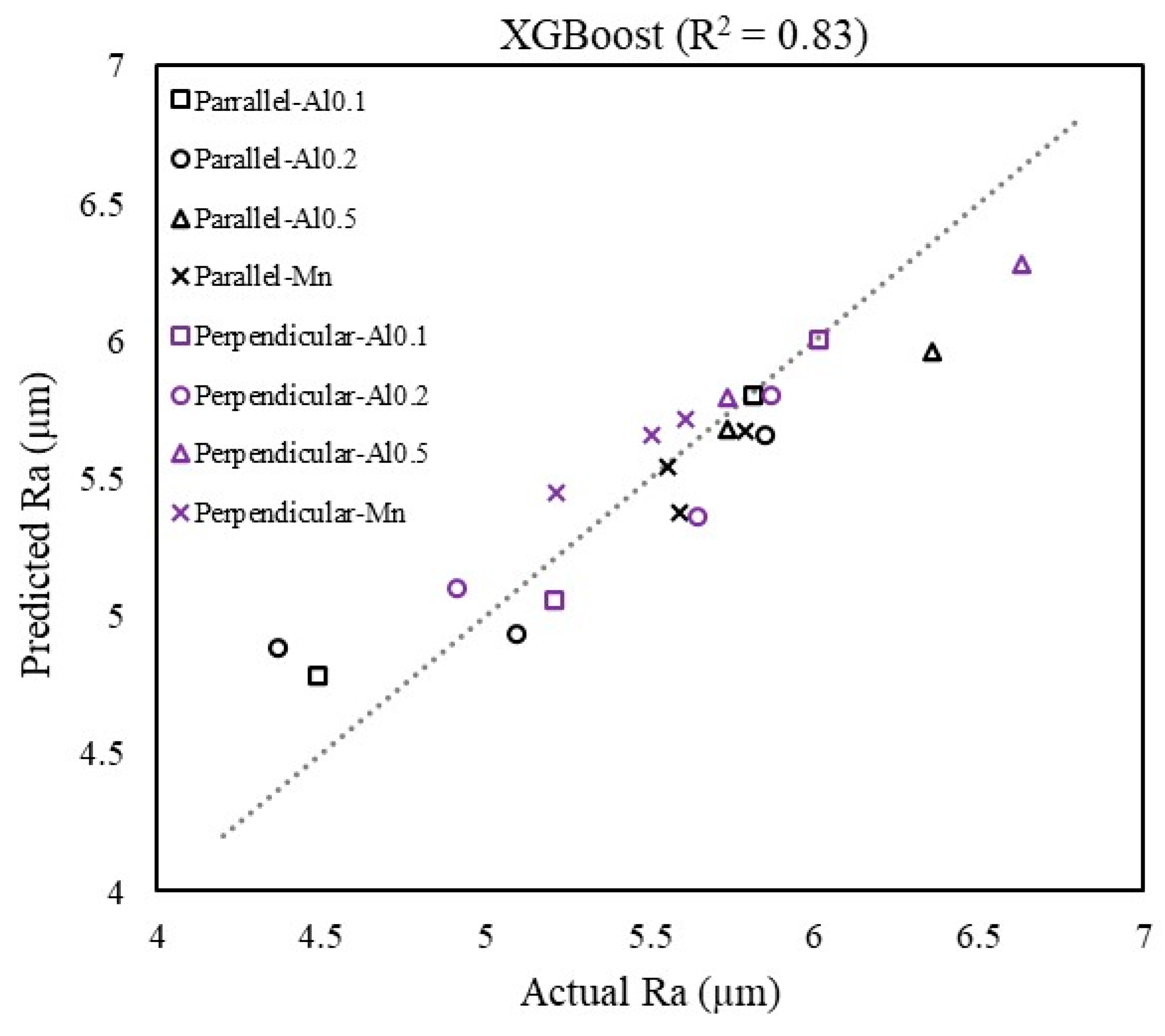

2.4.1. Extreme gradient boosting

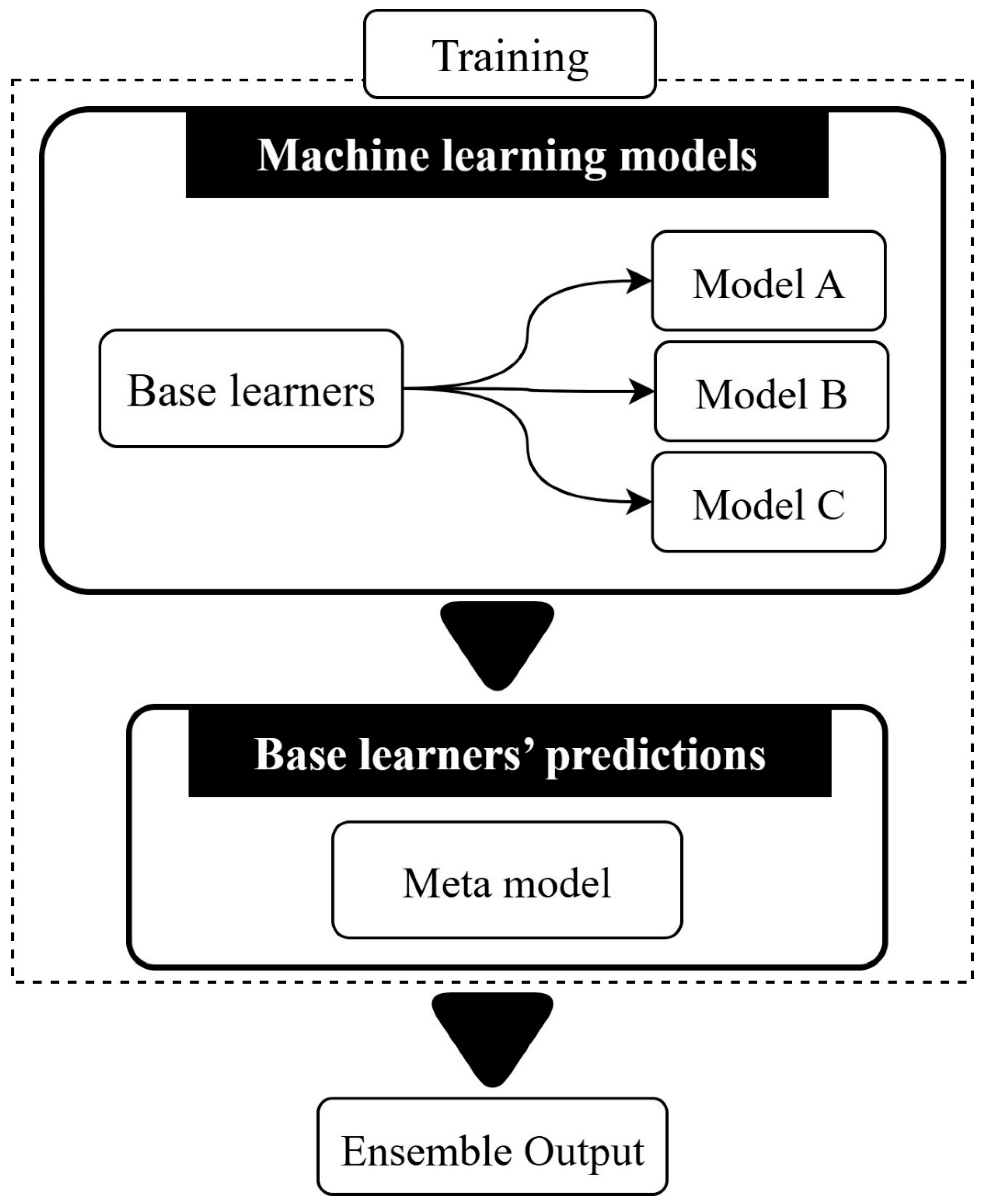

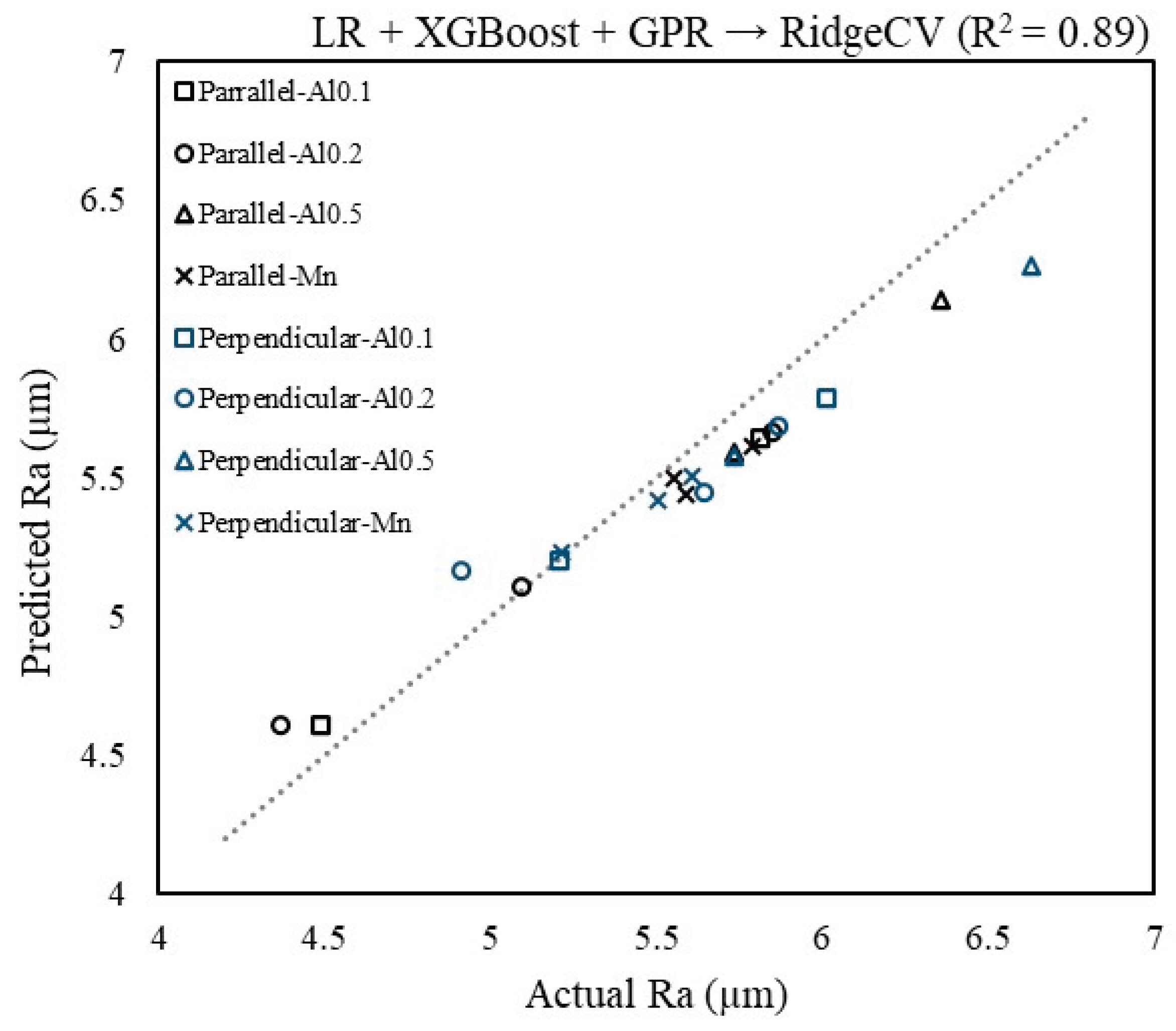

2.4.2. Stacking ensemble

3. Results and Conclusions

| Accuracy (%) | RMSE (µm) | MAPE (%) | R2 | |

| XGBoost | 96.79 | 0.22 | 3.32 | 0.83 |

| Stacking ensemble | 97.26 | 0.17 | 2.73 | 0.89 |

4. Conclusion

Acknowledgments

References

- Sesana, R.; Sheibanian, N.; Corsaro, L.; Özbilen, S.; Lupoi, R.; Artusio, F. Cold spray HEA coating surface microstructural characterization and mechanical testing. Results in Materials 2024, 21, 100540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, J.-W. Overview of High-Entropy Alloys. In High-Entropy Alloys: Fundamentals and Applications; Gao, M.C., Yeh, J.-W., Liaw, P.K., Zhang, Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, M.-H.; Yeh, J.-W. High-Entropy Alloys: A Critical Review. Materials Research Letters 2014, 2, 107–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zuo, T.T.; Tang, Z.; Gao, M.C.; Dahmen, K.A.; Liaw, P.K.; Lu, Z.P. Microstructures and properties of high-entropy alloys. Progress in Materials Science 2014, 61, 1–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miracle, D.B.; Senkov, O.N. A critical review of high entropy alloys and related concepts. Acta Materialia 2017, 122, 448–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, H. A Review on the Tribological Performances of High-Entropy Alloys. Advanced Engineering Materials 2022, 24, 2101548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemphill, M.A.; Yuan, T.; Wang, G.Y.; Yeh, J.W.; Tsai, C.W.; Chuang, A.; Liaw, P.K. Fatigue behavior of Al0.5CoCrCuFeNi high entropy alloys. Acta Materialia 2012, 60, 5723–5734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.-J.; Chen, M.-R.; Yeh, J.-W.; Lin, S.-J.; Chen, S.-K.; Shun, T.-T.; Chang, S.-Y. Mechanical performance of the AlxCoCrCuFeNi high-entropy alloy system with multiprincipal elements. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions A 2005, 36, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Zhou, Q.; Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; He, Y.; Wang, H. Tribological Behavior of High Entropy Alloy Coatings: A Review. Coatings 2022, 12, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, G.L.; Wang, X.H.; Wang, J.F. Microstructure and properties of ceramic particle reinforced FeCoNiCrMnTi high entropy alloy laser cladding coating. Intermetallics 2022, 140, 107402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Wang, Z. Microstructure and wear behaviour of in-situ TiN-Al2O3 reinforced CoCrFeNiMn high-entropy alloys composite coatings fabricated by plasma cladding. Materials Letters 2020, 272, 127870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Tao, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, B. Microstructure and wear properties of TiN–Al2O3–Cr2B multiphase ceramics in-situ reinforced CoCrFeMnNi high-entropy alloy coating. Materials Chemistry and Physics 2022, 276, 125352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, J.; Xin, D.; Chen, X.; Xin, H. Investigation of the microstructure and friction mechanism of novel CoCrCu0.2FeMox high-entropy alloy coating using plasma arc cladding. Journal of Materials Science 2022, 57, 19972–19985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruzova, Т.А.; Haddadi, B. Surface roughness and its measurement methods - Analytical review. Results in Surfaces and Interfaces 2025, 19, 100441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushil, K.; Ramkumar, J.; Chandraprakash, C. Surface roughness analysis: A comprehensive review of measurement techniques, methodologies, and modeling. Journal of Micromanufacturing 0 25165984241305225. [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, W.; Liu, Z.; Gong, Z.; Du, S.; Zhang, Y. The Impact of Surface Roughness on the Friction and Wear Performance of GCr15 Bearing Steel. Lubricants 2025, 13, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Bai, Q.; Zhao, C.; Li, Q.; Zhang, S. Effect of ultrasonic high-frequency micro-forging on the wear resistance of a Fe-base alloy coating deposited by high-speed laser cladding process. Vacuum 2024, 221, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, A.; Zhao, J.; Cui, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B. Effects of TiAlN Coating Thickness on Machined Surface Roughness, Surface Residual Stresses, and Fatigue Life in Turning Inconel 718. Metals 2024, 14, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, J.; Sonwani, R.K. Optimize chemical milling of aluminium alloys to achieve minimum surface roughness in Aerospace and Defense Industry. Journal of the Indian Chemical Society 2025, 102, 101537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, K.; Smolina, I.; Dziedzic, R.; Stopyra, W.; Karoluk, M.; Kuźnicka, B.; Kurzynowski, T. Tailoring heat treatment for AlSi7Mg0.6 parts with as-built surface generated by laser powder bed fusion to reduce surface roughness sensitivity. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2024, 984, 173903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abellán-Nebot, J.V.; Vila Pastor, C.; Siller, H.R. A Review of the Factors Influencing Surface Roughness in Machining and Their Impact on Sustainability. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Computer Science 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahani, N.M.; Zheng, X.; Liu, C.; Hassan, F.U.; Li, P. Developing an XGBoost Regression Model for Predicting Young’s Modulus of Intact Sedimentary Rocks for the Stability of Surface and Subsurface Structures. Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, Volume 9 - 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustapha, I.B.; Abdulkareem, Z.; Abdulkareem, M.; Ganiyu, A. Predictive modeling of physical and mechanical properties of pervious concrete using XGBoost. Neural Computing and Applications 2024, 36, 9245–9261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, W.; Qin, J. Coupling of XGBoost ensemble methods and discrete element modelling in predicting autogenous grinding mill throughput. Powder Technology 2023, 422, 118480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Ren, X.; Chen, J.; Chen, X. A novel material removal prediction method based on acoustic sensing and ensemble XGBoost learning algorithm for robotic belt grinding of Inconel 718. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2019, 105, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraheni, M.; Soudmand, B.H.; Amini, S.; Fotouhi, M. Stacked generalization ensemble learning strategy for multivariate prediction of delamination and maximum thrust force in composite drilling. Journal of Composite Materials 2024, 58, 3113–3138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, T.; Cao, Y. Tool wear prediction based on multisensor data fusion and machine learning. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2025, 137, 5213–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, E.; Ramasamy, M.; Elango, S.; Mohanraj, K.; Ang, C.K.; Khalfallah, A. Ensemble Learning-Based Metamodel for Enhanced Surface Roughness Prediction in Polymeric Machining. Machines 2025, 13, 570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özbilen, S.; Vasquez, J.F.B.; Abbott, W.M.; Yin, S.; Morris, M.; Lupoi, R. Mechanical milling/alloying, characterization and phase formation prediction of Al0.1–0.5(Mn)CoCrCuFeNi-HEA powder feedstocks for cold spray deposition processing. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2023, 961, 170854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesana, R.; Corsaro, L.; Sheibanian, N.; Özbilen, S.; Lupoi, R. Wear Characterization of Cold-Sprayed HEA Coatings by Means of Active–Passive Thermography and Tribometer. Lubricants 2024, 12, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvålseth, T.O. Cautionary Note about R 2. The American Statistician 1985, 39, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicco, D.; Warrens, M.J.; Jurman, G. The coefficient of determination R-squared is more informative than SMAPE, MAE, MAPE, MSE and RMSE in regression analysis evaluation. Peerj computer science 2021, 7, e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodson, T.O. Root-mean-square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE): when to use them or not. Geosci. Model Dev. 2022, 15, 5481–5487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour Abyaneh, M.; Narimani, P.; Hadad, M.; Attarsharghi, S. Using machine learning and optimization for controlling surface roughness in grinding of St37. Energy Equipment and Systems 2023, 11, 321–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarafza, M.; Hajialilue Bonab, M.; Derakhshani, R. A Deep Learning Method for the Prediction of the Index Mechanical Properties and Strength Parameters of Marlstone. Materials 2022, 15, 6899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Li, Y.; Qiao, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Huang, Z. Prediction of mechanical properties and surface roughness of FGH4095 superalloy treated by laser shock peening based on XGBoost. Journal of Alloys and Metallurgical Systems 2023, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.H.; Liu, Y.F.; Wang, T.; Wang, J.G.; Liu, Y.M.; Huang, Q.X. Intelligent prediction model of mechanical properties of ultrathin niobium strips based on XGBoost ensemble learning algorithm. Computational Materials Science 2024, 231, 112579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, T.M.H. Chapter 4 - Linear regression. In Machine Learning; Mechelli, A., Vieira, S., Eds.; Academic Press, 2020; pp. 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, M.; Hassani, H.; Javaherian, A.; Amindavar, H.; Torabi, S. Automatic fault detection in seismic data using Gaussian process regression. Journal of Applied Geophysics 2019, 163, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawar, S.; Mouazen, A.M. Combining mid infrared spectroscopy with stacked generalisation machine learning for prediction of key soil properties. European Journal of Soil Science 2022, 73, e13323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modanloo, V.; Elyasi, M.; Lee, T.; Quagliato, L. Modeling of tensile strength and wear resistance in friction stir processed MMCs by metaheuristic optimization and supervised learning. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2025, 139, 3095–3118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modanloo, V.; Alimirzaloo, V.; Elyasi, M. Optimal Design of Stamping Process for Fabrication of Titanium Bipolar Plates Using the Integration of Finite Element and Response Surface Methods. Arabian Journal for Science and Engineering 2020, 45, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faska, Z.; Khrissi, L.; Haddouch, K.; El Akkad, N. A robust and consistent stack generalized ensemble-learning framework for image segmentation. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science 2023, 70, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Lu, H. A novel stacking ensemble learner for predicting residual strength of corroded pipelines. npj Materials Degradation 2024, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Parameters | Output Parameters | |||||

| Samples | Cut off (mm) |

No. Cut off | Type | Temperature (°C) |

Alloy type | Ra (µm) |

| 1 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 650 | Al0.1 | 5.81 |

| 2 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 750 | Al0.1 | 4.48 |

| 3 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 650 | Al0.2 | 4.36 |

| 4 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 750 | Al0.2 | 5.85 |

| 5 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 850 | Al0.2 | 5.09 |

| 6 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 650 | Al0.5 | 6.35 |

| 7 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 750 | Al0.5 | 5.73 |

| 8 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 650 | MN-HEA | 5.58 |

| 9 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 750 | MN-HEA | 5.55 |

| 10 | 0.25 | 5 | Parallel | 850 | MN-HEA | 5.78 |

| 11 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 650 | Al0.1 | 6.01 |

| 12 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 750 | Al0.1 | 5.20 |

| 13 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 650 | Al0.2 | 5.64 |

| 14 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 750 | Al0.2 | 5.87 |

| 15 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 850 | Al0.5 | 4.90 |

| 16 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 650 | Al0.5 | 6.62 |

| 17 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 750 | Al0.5 | 5.73 |

| 18 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 650 | MN-HEA | 5.21 |

| 19 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 750 | MN-HEA | 5.50 |

| 20 | 0.25 | 5 | Perpendicular | 850 | MN-HEA | 5.60 |

| Parameter | Sum sq | df | Mean sq | F | P-Value |

| Type | 5.93 | 1 | 5.93 | 1.24 | 0.28 > 5% |

| Temperature | 2.12 | 1 | 2.12 | 0.44 | 0.51 > 5% |

| Alloy type | 15.53 | 3 | 5.17 | 1.08 | 0.38 > 5% |

| Error | 66.92 | 14 | 4.78 | - | - |

| Total | 90.52 | 19 | - | - | - |

| Hyperparameter | Optimal value |

| Number of trees | 400 |

| Learning rate/tree | 0.07 |

| Maximum depth/tree | 4 |

| Subsample/tree | 0.9 |

| Column sample/tree | 0.9 |

| reg_lambda | 5.0 |

| reg_alpha | 0.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).