Introduction

In 1883, French ichthyologist Henri Frédéric Paul Gervais (1845–1915), son of renowned zoologist and palaeontologist Paul Gervais, both linked to the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle (MNHN) in Paris, described a new species of humpback whale,

Megaptera indica H.-P. Gervais, 1883 (see Supplementary Information). The description was based on an adult humpback whale that stranded in Iraq, at the extreme northwestern end of the Persian/Arabian Gulf (hereinafter referred to as ‘the Gulf’) at Basora Bay, near the present-day port city of Basrah (30°30’54”N, 47°48’36”E) (

Figure 1), on an unknown date, but in or before 1883. A later, more detailed paper (H.-P. Gervais, 1888) reported that the holotype skeleton was collected at the Chat-el-Arab river delta and brought to Marseille, France, by ship in 1883. It was deposited as a trade item with a merchant in Marseille, where a certain ‘Professor Marion’ was able to examine it. Prof. Georges Pouchet

1 then asked Gervais to research the species to which it belonged and to assess its scientific value. Reportedly, examination of the tympanoperiotic indicated that the whale skeleton belonged to

Megaptera (Gervais, 1888). A drawing of the diagnostic scapula by Prof. Marion confirmed this identification (Gervais, 1888). The MNHN decided to acquire the skeleton, registered in the MNHN

Journal du Laboratoire d’Anatomie comparée (JAC) (Gervais, 1888). Only an incomplete skull remains, referred to by Robineau (1989, p. 278) as calvarium ‘JAC 1883-2255’, but presently bearing the collection number MNHN-ZM-AC-1883-2255. It is unknown what happened to the mandibles and postcranial bones, but they must have been transported to France as Gervais (1883a,b, 1888) had access to them.

Contrary to what we presently know, i.e that humpback whales have a habitual presence in the Gulf (Dakhteh et al., 2017), Gervais (1883a,b) suggested that the Iraqi whale had ‘accidentally’ entered the Gulf from the Indian Ocean, hence his choice of the species name. Several lines of evidence including distributional, genetic, behavioural, morphological, ecological and pathological, indicate that the humpback whale population inhabiting the Arabian Sea represents a reproductively isolated lineage, distinct from Southern Hemisphere humpback whales, long suspected to be of subspecific status (Mikhalev, 1997; Papastavrou and Van Waerebeek, 1997; Clapham and Mead, 1999; Baldwin et al., 2010; Minton et al., 2010, 2011; Pomilla et al., 2014; Jackson et al., 2014; Van Bressem et al., 2014; Willson et al., 2015, 2017). Humpback whales found inside the Gulf (Dakhteh et al., 2017), represented by the Iraqi specimen, are proposed to form part of the non-poleward migrating Arabian Sea humpback whales (ASHW), a newly recognised subspecies Megaptera novaeangliae indica (Amaral et al., submitted).

A study visit to MNHN was conducted aiming to: (a) confirm the Iraqi whale skull as a humpback whale; (b) document its cranial morphology; (c) collect a sample for molecular genetic comparison with the ASHW population to evaluate taxonomic status and nomenclature (Amaral et al., submitted).

Material and Methods

Two of us (KVW, RB) visited MNHN on 23 May 2019 in order to examine the M. indica holotype and to sample bone tissue. The curator of vertebrate holotypes (CC), aided by Laurent Albenga, arranged in situ logistics, greatly facilitating our mission to the MNHN marine mammal storage facilities, which are kept in warehouses located in the Ile-de-France region.

The incomplete and moderately damaged

M. indica skull

2 was found set in a horizontal position, dorsal side up, inside a 180 cm high wooden crate, which however obstructed lateral and ventral photographic documentation. A small wooden plate inscribed with ‘Basra, Iraq’ was associated with the skull and both large numericals ‘1883 2255’ in (fading) red, and smaller ones in black, were marked on the supraoccipital bone, confirming that this specimen was indeed the

Megaptera indica holotype (Gervais, 1883a,b, 1888; Robineau, 1989).

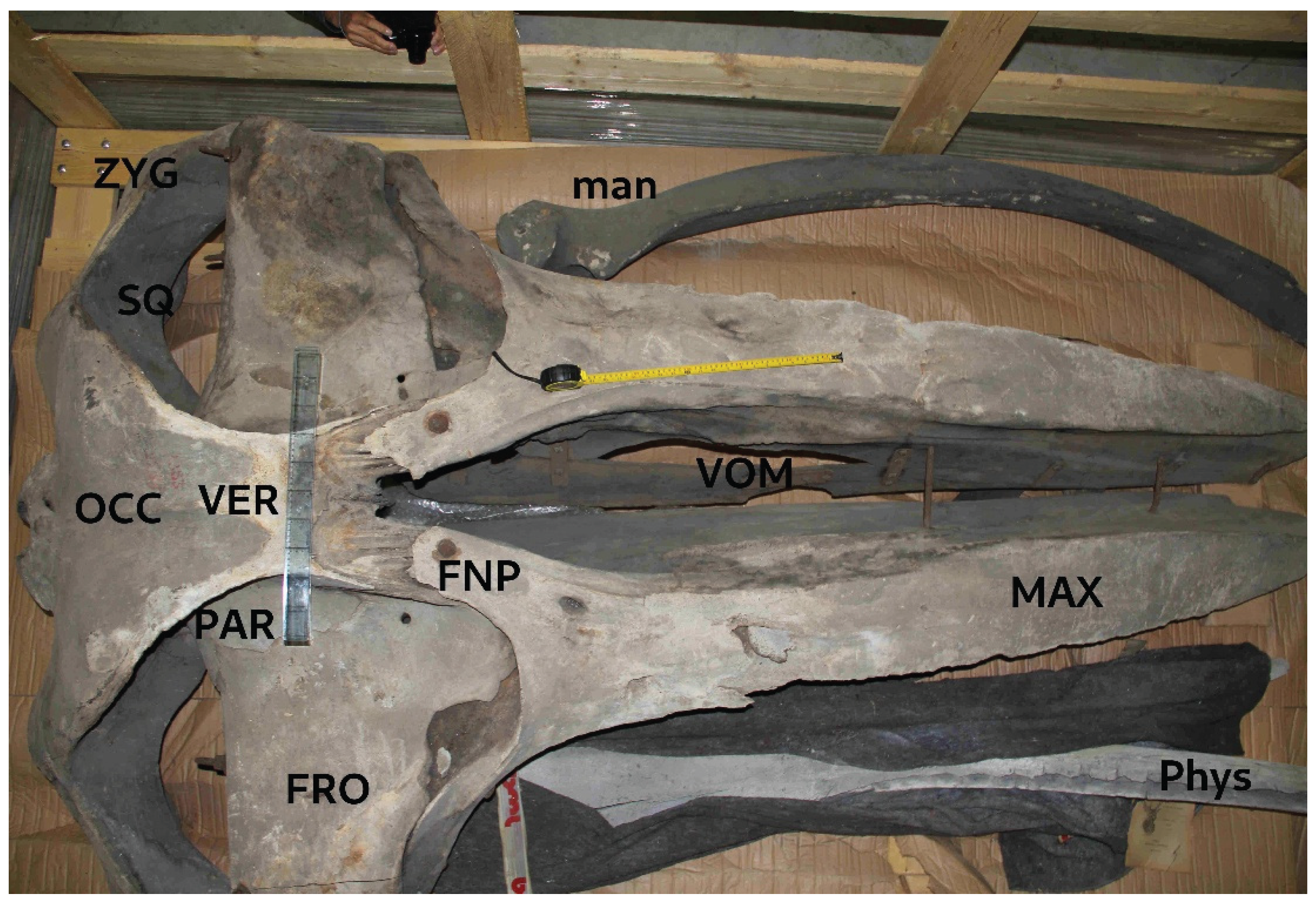

Three unrelated bones were found inside the same crate, including a mandible of a small sperm whale

Physeter macrocephalus, a small-sized balaenopterid mandible

3 incompatible with the

M. indica skull, and an unidentified whale rib, all without visible collection numbers.

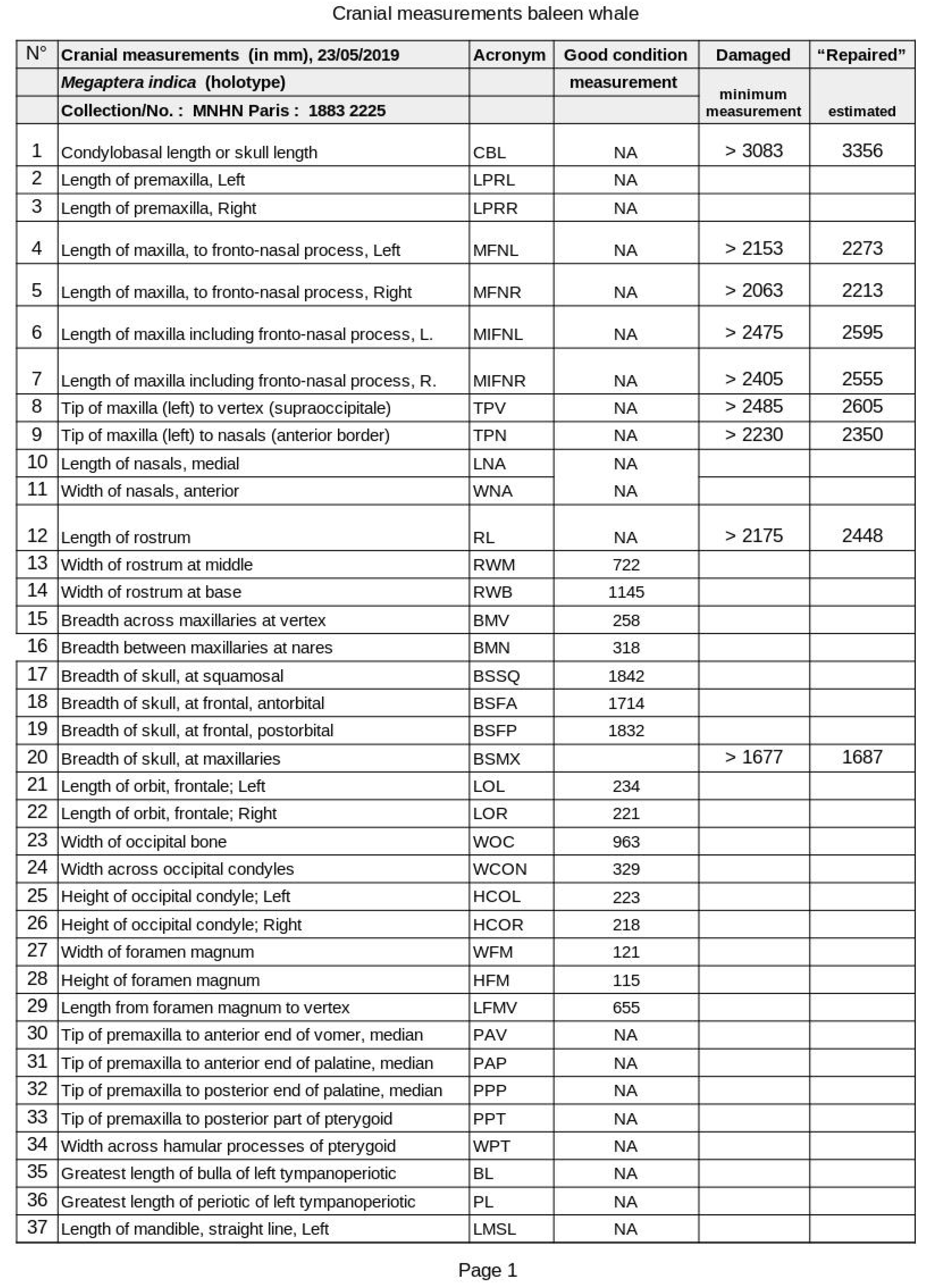

A protocol with 50 standard cranial measurements was prepared (Table), based primarily on Omura (1975) and other cetacean osteology sources (Miller, 1923; Tomilin, 1967; Glass, 1973; Perrin, 1975; True, 1983). However, only about half of craniometrics could be measured due to the skull’s incomplete condition. Per convention (Perrin, 1975), where feasible, left side craniometrics were selected.

The originally planned bone sampling method for genetic analysis, involving the use of a diamond core drill bit to microsample an occipital condyle, was deemed incompatible with MNHN protocols. The curator (CC) proposed an alternate methodology, proven effective before, consisting of the macrosampling of bone for later microsampling at the laboratory in sterile conditions. Indeed, the warehouse contained hundreds of marine mammal specimens, which, via aerosolized bone dust, could contaminate a locally collected microsample.

Photographs were taken, mostly in orthogonal plane to the skull, with Nikon and Canon EOS 60D cameras fitted with 18-135 mm zoom lenses. A 50 cm ruler was placed as scale. The specimen was too heavy and damaged to allow safe manipulation; thus no ventral or lateral views were obtained.

o facilitate interpretation, Gervais (1883a) was transcribed and translated from French (Supplementary Information). DeepL.com software was used to speed up translation, after which KVW thoroughly edited it for scientific accuracy.

Results

Publication History

The publication record of Megaptera indica is somewhat complex, as two slightly different versions were published (Gervais 1883a,b), besides a third, more comprehensive, paper (Gervais, 1888). A first account of the new species was scheduled to be orally presented by H.-P. Gervais to the Académie des Sciences in Paris at its final session (‘Séance’) of the year, on 31 December 1883 (Gervais, 1883a). This early published version (Gervais, 1883a, see Supplementary material), what could be considered equivalent to a preprint or a separate, was dated 31 December 1883. Apparently, it was printed sometime prior to the 1883’s final Académie session and was most likely available as a separate at the meeting. It shows a simple, preliminary pagination (p. 1–4), and reports the type location as ‘baie de Basora’ which posteriorly (Gervais, 1883b) was corrected as ‘baie de Bassora’. This preprint must have been published prior to the 31 December meeting as evidenced by the fact that it was not yet known that H.-P. Gervais would not himself present his paper, but rather Mr. É. Blanchard, as reported later (p. 1566) in the volume (tome) 97 (2) (Gervais, 1883b). Therefore, we have assumed that Mr. Blanchard must have had the physical preprint (Gervais, 1883a) in his hands, to be able to present the paper, or an equivalent text, instead of Gervais.

Interestingly, Robineau (1989) cites the tome 97 (Gervais, 1883b) as the formal source of the new species description. However, this half-yearly compilation, 1578 pages long, can hardly have been printed in 1833, considering that it lists on p. 1577 ‘Ouvrages recus dans la Séance du 31 décembre 1883’ (publications received on 31/12/1883) and added the detail (p. 1566) of Mr. Blanchard’s reading. We conclude that tome 91(2) was completed, printed and published after the last session of 31 December 1983, i.e., in early 1884. However, the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) in its article 21.8. states: ‘Before 2000, an author who distributed separates in advance of the specified date of publication of the work in which the material is published thereby advanced the date of publication’. In conclusion, with Gervais (1883a) being the earliest version of the work, it should be designated the formal description of Megaptera indica.

Condition of the Skull

The 19th century

M. indica type specimen was described as an almost complete skeleton, including long anterior limbs and black baleen, consistent with

Megaptera (Gervais, 1883a,b; 1888). The cause of death and the precise condition of carcass when encountered stranded were not reported, but Gervais (1888) stated it was a skeleton. Robineau (1989) found only a partial skull at MNHN, like we did. Many cranial bones were missing, including both mandibles, premaxillae, nasals, palatines (damaged), pterygoids, lacrimals, tympano-periotics and jugals. Hyoid bones and sternum were also missing. No baleen plates were present. Moreover, the maxillae were damaged apically (see below), while the vomer was bolted together because fractured in several pieces. Several pins and metal plates had also been applied to ensure the maxillae remained attached to the neurocranium and potentially for lifting/display purposes. The maxillae appeared mostly correctly placed, which is important since misaligned maxillae could bias the rostrum base width (RBW) measurement (

Table 1).

Estimation of Condylobasal Length and Body Length

The condylobasal length (CBL) and zygomatic width (ZW, typically equals maximum skull width) arguably comprise the two most important craniometrics of the balaenopterid skull, considering that the relative size of cranial bones are weighted against these. In Megaptera, as in other balaenopterids, the premaxillae extend beyond the maxillae anteriad and thus co-determine standard CBL. However, considering that both premaxillae of M. indica were missing, skull length was initially approximated as the (shorter) ‘maxilla-based CBL’. Moreover, although the rostral tips of the maxillae were slightly damaged, the original outline and the length of the missing maxillary apices could be estimated from their converging left and right borders, i.e., by adding ≈120 mm (left side) and ≈150 mm (right side). The left ‘maxilla-based CBL’ was then estimated at 3,203 mm (3,083 mm measured + 120 mm correction).

We used good-resolution photographs of three adult M. novaeangliae skulls (see True, 1983; plates 29 & 32) to calculate the relative protrusion of the left premaxilla anteriad beyond the left maxilla in this species. The three skulls considered were: USNM 21492; USNM 16252; and N.N. at Milwaukee Public Museum (True, 1983). To account for the projecting premaxillae required the addition of an extra axial length of respectively, 5.13%, 5.09% and 4.13% (mean= 4.78%) of the measured ‘maxilla-based CBL’. When applying this mean correction, i.e., by adding 153 mm length to compensate for the missing premaxilla, a fair estimate of the ‘standard CBL’ of M. indica is then ca. 3,356 mm.

The skull length (CBL) of an adult humpback whale is 26.5–30% of body length (True, 1983; Tomilin, 1967), while the mandible length may reach 25% (Pyenson et al., 2013)

4. Thus, from the approximate CBL, body length of

M. indica is estimated to have ranged between 11.87–12.91 m, indicating the whale was almost certainly sexually mature (Mikhalev, 1997). Although some variation in cranial proportions between Atlantic

Megaptera specimens and

M. indica is postulated (Gervais, 1883a,b; 1888), the above approximations are likely reasonably correct.

Bone Sampling and Processing

About 1 cm3 of bone tissue from the anterio-mesial edge of the left frontal bone was sampled using a Dremel rotary tool mounted with a small circular saw. Standard precautions were taken to avoid contamination (gloves, thorough cleansing of tools and sample locus with ethanol). The macrosampling yielded good-quality DNA (Amaral et al., submitted), despite the age (136 yrs) of the skull.

The CITES export-import permit procedure of the sample and actual delivery to the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York, was coordinated by CC, TC & RLB. The process was severely complicated by Covid-19 pandemic restrictions. Ancient DNA extraction, amplification and comparative analysis with ASHW specimens were implemented by experts in M. novaeangliae phylogenetics (Amaral et al., submitted).

Taxonomic Confirmation as Megaptera

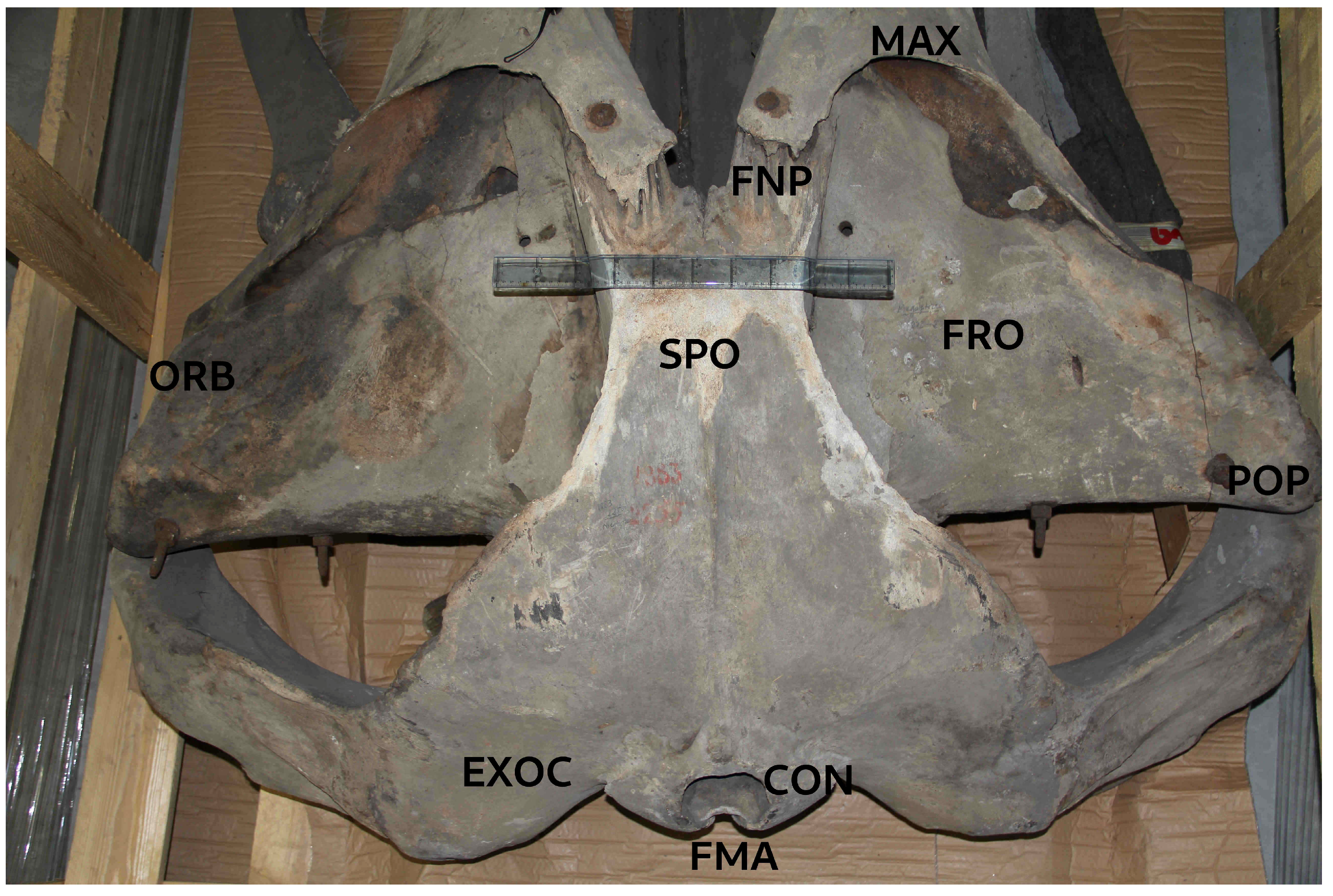

The size of the skull and moderate ankylosis between cranial bones indicated that the

M. indica type specimen was cranially mature, albeit not an old individual (

Figure 1 and Figure 3). For instance, suture lines between the temporal and frontal bones were still clearly visible. Gervais (1883a,b) reported it as an adult individual. Despite multiple missing and damaged cranial bones, the overall cranial morphology (

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) confirms the study specimen to be a

Megaptera sp., distinct from

Balaenoptera spp. The below characters are of particular relevance.

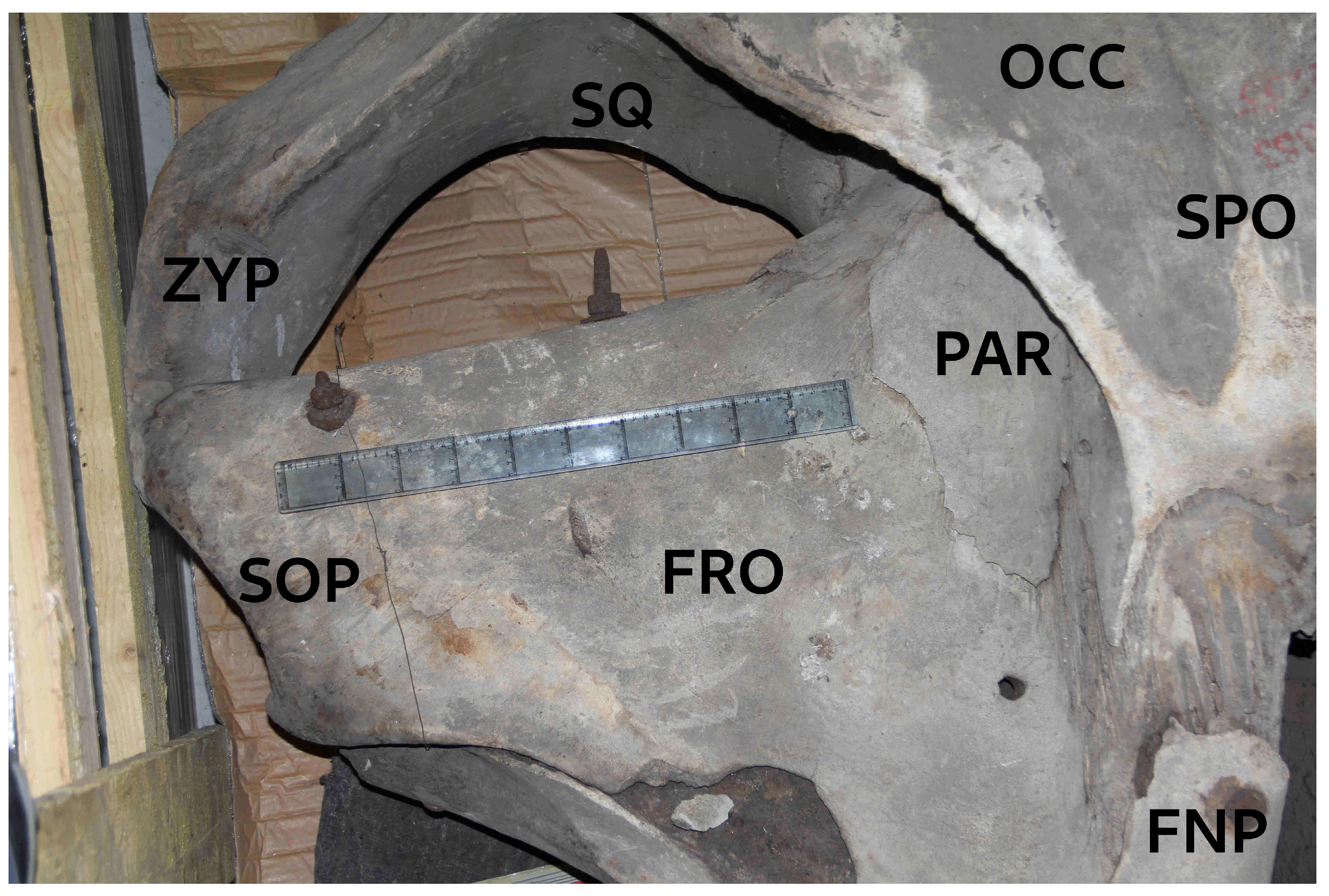

(i) A key anatomical cue for

Megaptera is the strongly prominent supraorbital processes of the frontal bones (see Gray, 1866 [his Figure 14]; True, 1983 [Plates 29 and 32]; Jefferson et al., 1993 [p.60], 2008 [p.501], which is also evident in

M. indica (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). Tomilin (1963; p.246) accurately emphasized the different shape of the supraorbital processes compared to these in

Balaenoptera spp.: ‘processes [in

Megaptera] are considerably expanded along the axis of the cranium, but greatly narrow towards the orbit’. Jointly with (ii), it is the most striking morphological feature, readily identifying a

Megaptera skull at ocular inspection.

(ii) As evident in

M. indica (

Figure 2 and 3), the anterior margin of the squamosal is rounded or U-shaped in

Megaptera, while pointed or V-shaped in

Balaenoptera spp. (see Jefferson et al., 1993, Figure 179; Jefferson et al., 2008; p.501). Also, squamosals in

M. indica are heavily built (

Figure 2 and 3), consistent with other

Megaptera (Tomilin, 1963). Archer et al. (2018) described it as ‘in

Megaptera, unlike other balaenopterids, the anterior margin of the squamosal is marked by a smooth and continuous surface’. The result, diagnostic for

Megaptera, is the lack of a distinct fold in the squamosal (a ‘squamosal crease’) as it transitions from the temporal wall to the zygomatic process at the rear of the temporal fossa (

Figure 2 and 3) (Deméré et al., 2005; Archer et al., 2018).

(iii) In Balaenoptera spp. the breadth of the skull (BSFP) at the postorbital processes of frontals does not exceed 1.5 times the rostrum width at base (RWB) (Reyes and Molina, 1997), differentiating it from M. novaeangliae which are reported to have a breadth of skull ratio of about 2 (Reyes and Molina, 1997). Published photos of four North Atlantic M. novaeangliae skulls (True, 1983) allowed this ratio to be estimated, with a range of 1.72–1.96 (mean= 1.85). In M. indica the ratio ranged between 1.60 and 1.73 (mean= 1.665), calculated respectively from cranial measurements and photogrammetry. Thus, the highest M. indica estimate only slightly overlaps with the lowest value for Atlantic humpback whales, but amply exceeds other balaenopterids.

Jefferson et al. (2008) presented an inverted ratio, but equivalent to Reyes and Molina (1997): the RWB is only about 0.50 of cranial width (BSFP) in M. novaeangliae while at least 2/3 cranial width (0.666 or higher) in other balaenopterids. In M. indica this ratio was 0.625, again outside the Balaenoptera spp. range.

(iv) In

M. indica, as in other humpback whales (see True, 1983: Plates 29 and 32), the imaginary line that unites the external borders of the orbital processes of the maxillae passes behind the nasals (

Figure 3), whereas it passes over the nasals in other balaenopterids (Reyes and Molina, 1997). The nasal bones were lacking in

M. indica but their relative location at the skull’s vertex was evident.

(v) Tomilin (1967) indicates that, among large balaenopterids, M. novaeangliae has the maximum zygomatic process width index (i.e., breadth skull at squamosals = BSSQ) relative to CBL (57–66.9%, n=8), somewhat higher than M. indica which scored 54.9%, and considerably higher than fin whale B. physalus (44.6–52.2%, n=10), sei whale B. borealis (43–50.8%, n=9) and blue whale B. musculus (47.2–52.5) (Tomilin, 1967). Here again, M. indica scores in between M. novaeangliae and other balaenopterids, suggesting some taxonomic significance.

(vi) The naso-frontal process of the maxillae normally

5 expands posteriad in width in all

Balaenoptera spp., but not in

Megaptera (Tomilin, 1967; Reyes and Molina, 1997). Although proximal parts of the naso-frontal processes of the

M. indica holotype are slightly damaged, their outline is evident and there is no indication of a distal expansion (

Figure 1 and

Figure 3).

(vii) Another feature reported for the Megaptera skull is a downward rostral curvature, characterized by Tomilin (1967) as ‘dorsal contours of the maxillary and premaxillary more intricately curved than in Balaenoptera’. However, such curvature is not diagnostic, considering that sei whale B. borealis Lesson, 1828, also shows an arched head with slightly down-turned rostrum tip (see Andrews, 1916; images p. 98 & 101; Gambell, 1985).

(viii) The Megaptera scapula is unique among Balaenopteridae, for it lacks coracoid and acromial processes, while sometimes represented by rudimentary tubercles (Gray, 1866; Miller, 1923; Tomilin, 1967; True, 1983, Plates 34 and 36). Gervais (1883a,b) noted that the scapula of M. indica was lacking an acromion and that the coracoid process was represented by a small bony protrusion, consistent with known Megaptera features.

(ix) Gervais (1888), without specifying why, reported that the examination of the (presently missing) tympanoperiotic complex confirmed that the whale was a Megaptera. Gray (1866; e.g., his Figures 20 and 53) recognized ‘great differences’ in form of tympanic bones to separate whale species from one another.

Other Features of Interest

(a) Gervais (1883a,b) underscored that, in comparison with

Megaptera Boops of the North Atlantic,

M. indica had thick (dense) osseous tissue affecting many bones including vertebral bodies and their spinal and transverse processes, especially in the first cervicals, but also affecting pterygoids, palatine bones, sternum and metacarpals. These bones were not available for examination. This systemic condition is interesting as it may be pathologic, but might also be equivalent to the ‘swollen’ (pachyostosis) and dense (osteosclerotic) bones of Sirenia, a skeletal adaptation to reduce buoyancy (Domning, 2018). Unusually heavy bones could help whales to remain fully immerged and avoid insolation, despite the high-salinity, high-density waters of the Gulf (Swift and Bower, 2003; Paparella et al., 2022). Besides that unusual condition, no deformations or osteopathy were reported (Gervais, 1883a,b; 1888; Robineau, 1989). We did notice a small foramen (2-3 cm in diameter) perforating the dorsal edge of the left occipital condyle (

Figure 5), osteolytic, non-traumatic in origin. Considering its small size, it is unlikely that this foramen caused any ill health effects. The occipital condyles and adjacent occipital bone presented a somewhat rough surface, apparently also from osseous lysis (

Figure 5).

(b) Gervais (1883a,b) reported that the occipital bone of M. indica shows a strong central ridge, as do two of four humpback whale skulls pictured in True (1983). However, this feature is not unique to Megaptera, e.g., Balaenoptera physalus (Linnaeus, 1758) can also show such an occipital ridge (see True, 1983, Plate 1).

(c) The unique shape of the sternum in M. indica was emphasized by Gervais (1883a,b; 1888), however variation in shape between and within balaenopterid species is known to be naturally high. Klima (1978) confirmed great individual variability in the shape of sterna of M. novaeangliae that one could call triangular, heart-shaped, trilobate or U-shaped. Hence, diagnostic value is very limited, if not nihil.

Discussion and Conclusions

Contemporary cranial data presented here and historical descriptions of postcranials, e.g., on scapular morphology and long pectoral fins (Gervais, 1883a,b; 1888) confirm that Megaptera indica is a humpback whale. A comprehensive phylogenetic comparison between M. indica and Arabian Sea humpback whales from the Gulf of Oman is consistent with this finding (Amaral et al., submitted).

Some cranial indices demonstrated M. indica to be morphologically intermediate between M. novaeangliae and Balaenoptera spp. This supports the arguments based on mt-DNA control region (Amaral et al., submitted) to recognize M. indica as a distinct subspecies. Considering the historical publication record, it should be referred to as Megaptera novaeangliae indica (H.-P. Gervais, 1883).

Unusually thick postcranial bones (pachyostosis) were described by Gervais (1883a,b), which we suggest to be an example of phenotypic plasticity (Price et al., 2003) a likely adaptation to reduce excessive buoyancy (and damaging sun exposure), due to the high-salinity, high-density waters of the Gulf. The pachyostotic phenotype may have been acquired after long permanence in the Gulf (multiple months or years).

While detailed case studies are scarce, negative anthropogenic impacts affecting threatened humpback whales in the Persian/Arabian Gulf and the Arabian Sea are of major concern. Of seven documented records in the Gulf (Dakhteh et al., 2017), only two humpback whales were seen alive, one of which, a juvenile, was net-entangled in a drift gillnet and the other was severely injured by a propeller with unclear survivability. Among the five dead whales, at least three were juveniles. One was a confirmed fatality by ship collision, and three cases were probable collision victims as they were suspiciously found floating inside a port or in the general vicinity of a portarea (Dakhteh et al. 2017). In fact the Iraqi specimen, found near the port of Basrah, may well have died from a hit by a vessel. Globally, humpback whale, after fin whale, is the second-most commonly killed whale species by ship collisions (Van Waerebeek and Leaper, 2008) which for a remnant population as the ASHW is likely to be a significant factor. Some ship-stricken whales may have been killed considerable distances from the reporting location since they are often transported, wrapped around the ship’s bulbous bow (Van Waerebeek and Leaper, 2008), therefore interpretation of the precise conflict area should be carefully evaluated. Other plausible threats in the Gulf and Arabian Sea may include bycatch and entanglement in fisheries (Dakhteh et al., 2017; Minton et al., 2022), organic (eutrophication) and chemical pollution and oil spills (e.g., Robineau and Fiquet, 1994; Preen, 2004; Shokat et al., 2010) as well as infectious diseases (e.g., Van Bressem et al., 2014; Minton et al., 2022). Systematic whale surveying linked to environmental data should shed light on the factors that make the Gulf a suitable long-term habitat, if not permanent residence, for humpback whales. This shallow sea apparently offers favourable feeding or reproductive conditions (i.e., avoiding calf predation by killer whales Orcinus orca), or both (Dakhteh et al., 2017).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Funding

The US Marine Mammal Commission is acknowledged for funding key mission (logistics) expenses, especially travel.

Acknowledgements

The Muséum National d’Histoire naturelle of Paris is thanked for logistics support, access to the M. indica holotype, the commission’s approval of destructive sampling and general help with sampling. We thank in particular Laurent Albenga (MNHN) for practical help during the study visit. Five Oceans Environmental Services is acknowledged for supporting Robert Baldwin’s time. Lastly, we would also like to thank Ms. Leslie K. Overstreet, Curator of Natural-History Rare Books, Smithsonian Libraries and Archives, Washington, DC who provided important insight into the publications and dates on when H. P. Gervais’ new species description was actually published. The Lima-based Centro Peruano de Estudios Cetológicos (CEPEC) is an all-volunteer working group. KVW accepted no honorarium.

Disclosure Statement

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Amaral, A. R., Gaughran, S. J., Giakoumis, M., Brownell, R. L., Willson, A., Minton, G., Baldwin, R., Willson, M. S., Al Harthy, S., Al Jabri, A., Collins, T., Van Waerebeek, K. & Rosenbaum, H. (2025). A Whale Apart: Genetic Isolation of Arabian Sea Humpbacks Signals Subspecies Distinction. Submitted to Journal of Mammalogy.

- Andrews, R.C. (1916). Whale hunting with gun and camera; a naturalist’s account of the modern shore-whaling industry, of whales and their habits, and of hunting experiences in various parts of the world. Appleton and Company, New York.

- Archer, F., Robertson, K., Sabin, R. & Brownell, R.L., Jr. (2018). Taxonomic status of a “finner whale” (Balaenoptera swinhoei Gray, 1865) from southern Taiwan. Marine Mammal Science, 34, 1134-1140. [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, R., Collins, T., Minton, G., Findlay, K., Corkeron, P., Willson, A. & Van Bressem, M-F. (2010). Arabian Sea Humpback Whales: Canaries for the Northern Indian Ocean? IWC Scientific Committee document SC/62/SH20, Agadir, Morocco, June 2010. 5pp.

- Clapham, P. J. & Mead, J. G. (1999). Megaptera novaeangliae. Mammalian Species, 604, 1-9.

- Dakhteh, S. M. H., Ranjbar, S., Moazeni, M., Mohsenian, N., Delshab, H., Moshiri, H., Nabavi, S. M. B. & Van Waerebeek, K. (2017). The Persian Gulf is part of the habitual range of the Arabian Sea Humpback whale population. Journal of Marine Biology & Oceanography 6(3): 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Deméré, T. A., Berta, A. and McGowen, M.R. (2005). The taxonomic and evolutionary history of fossil and modern balaenopterid mysticetes. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 12:99–143. [CrossRef]

- Domning, D.P. (2018). Sirenian evolution. pp. 856-859. In : B. Würsig, J.G.M. Thewissen and K. M. Kovacs (eds). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Third Edition, Elsevier.

- Gambell, R. (1985). Sei whale Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828. Pp. 155-170. In: S. H. Ridgway & R. Harrison (Eds), Handbook of Marine Mammals, 3. Academic Press, London.

- Gervais, H.-P. (1883a). Sur une nouvelle espèce de Mégaptère, provenant de la baie de Basora (golfe Persique). Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Paris, 31 décembre 1883, 1-4. [separate or preprint].

- Gervais, H.-P. (1883b). Sur une nouvelle espèce du genre Mégaptère provenant de la baie de Bassora (golfe Persique). Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, Paris, 97(2), 1566-1569.

- Gervais, H.-P. (1888). Sur une nouvelle espèce de Mégaptère (Megaptera indica) Provenant du Golfe Persique. Nouvelles archives du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris 10, 199-218.

- Glass, B. P. (1973). A Key to the Skulls of North American Mammals. Oklahoma State University, Stillwater. 59pp. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J. E. (1866). Catalogue of Seals and Whales in the British Museum. Printed by Order of the Trustees. Second Edition, London. 402 pp.

- Jackson, J. A., Steel, D. J., Beerli, P., Congdon, B. C., Olavarría, C., Leslie, M. S., Pomilla, C., Rosenbaum, H. & Baker, C. S. (2014). Global diversity and oceanic divergence of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Proceedings of Biological Sciences, 2014 Jul 7, 281(1786):20133222. [CrossRef]

- Jefferson, T.A., Leatherwood, S. & Webber, M.A. (1993). FAO species identification guide. Marine Mammals of the World. United Nations Environment Programme. FAO, Rome. 320 pp.

- Jefferson, T. A., Webber, M. A. & Pitman, R. L. (2008). Marine Mammals of the World. A comprehensive Guide to their Identification. Elsevier, Academic Press, London, UK, 573pp.

- Klima, M. (1978). Comparison of early development of sternum and clavicle in striped dolphin and in humpback whale. The Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute, 30, 253-269.

- Miller, G.S. (1923). The telescoping of the cetacean skull. Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections, 76(5), 1-55, 8 plates.

- Minton, G., Collins, T., Findlay, K., Ersts, P., Rosenbaum, H., Berggren, P. & Baldwin, R. (2011). Seasonal distribution, abundance, habitat use and population identity of humpback whales in Oman. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management (Special Issue 3), 185–198. [CrossRef]

- Minton, G., Cerchio, S., Ersts, P., Findlay, K., Pomilla, C., Bennet, D., Meyer, M., Razafindrakoto, Y., Kotze, P., Oosthuizen, W., Leslie, M., Andrianarivelo, N., Baldwin, R., Ponnampalam, L. & Rosenbaum, H. (2010). A note on the comparison of humpback whale tail fluke catalogues from the Sultanate of Oman with Madagascar and the East African Mainland. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 11, 65-68. [CrossRef]

- Minton, G., Van Bressem, M-F., Willson, A., Collins, T., Al Harthi, S., Sarouf Willson, M., Baldwin, R., Leslie, M. & Van Waerebeek, K. (2022). Visual health assessment and evaluation of anthropogenic threats to Arabian Sea humpback whales in Oman. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, 23 (1), 59-79. [CrossRef]

- Mikhalev, Y. A. (1997). Humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae in the Arabian Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 149, 13-21. [CrossRef]

- Omura, H. (1975). Osteological study of the minke whale from the Antarctic. The Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute, 27, 1-36.

- Paparella, F.-, D’Agostino, D. & John Burt, J.A. 2022. Long-term, basin-scale salinity impacts from desalination in the Arabian/Persian Gulf. Scientific Reports 12:20549. [CrossRef]

- Papastavrou V. and Van Waerebeek K. (1997). A note on the occurrence of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in tropical and subtropical areas: the upwelling link. Report of the International Whaling Commission 47: 945-947. [CrossRef]

- Perrin, W.F. (1975). Variation of spotted and spinner porpoise (genus Stenella) in the eastern tropical Pacific and Hawaii. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. 206 pp.

- Pomilla, C., Amaral, A. R., Collins, T., Minton, G., Findlay, K., Leslie, M. S., Ponnampalam, L., Baldwin, R. & Rosenbaum, H. (2014). The World’s Most Isolated and Distinct Whale Population? Humpback Whales of the Arabian Sea. PLoS ONE, 9, e114162, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Preen, A. (2004) Distribution, abundance and conservation status of dugongs and dolphins in the southern and western Arabian Gulf. Biological Conservation, 118: 205-218. [CrossRef]

- Price, T.D., Qvarnström A. & Irwin D.E. (2003). The role of phenotypic plasticity in driving genetic evolution. Proceedings Biological Sciences. 270 (1523): 1433–40. [CrossRef]

- Pyenson, N. D., Goldbogen, J. A., & Shadwick, R. E. (2013). Mandible allometry in extant and fossil Balaenopteridae (Cetacea: Mammalia): the largest vertebrate skeletal element and its role in rorqual lunge feeding. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 108, 586–599. [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J. C. & Molina, D. (1997). Clave artificial para la identificación de cráneos de cetáceos del Pacífico sudeste. Boletín Museo Nacional de Historia Natural de Chile, 46: 95-119. [CrossRef]

- Robineau, D. (1989). Les types de cétacés actuels du Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle. I: Balaenopteridae, Kogiidae, Ziphiidae, Iniidae, Pontoporiidae. Bulletin du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle. Section A, Zoologie, biologie et écologie animales 11, 271-289.

- Robineau, D. & Fiquet, P. (1994) Cetaceans of Dawhat ad-Dafi and Dawhat al-Musallamiya (Saudi Arabia) one year after the Gulf War oil spill. Cour Forsch-Inst Senckenberg, 166, 76-80.

- Shokat, P., Nabavi, S.,M.,B., Savari, A. & Kochanian, P. (2010) Ecological quality of Bahrekan coast, biotic indices and benthic communities. Transitional Waters Bulletin, 4, 25-34.

- Swift, S. A., & Bower, A. S. (2003). Formation and circulation of dense water in the Persian/Arabian Gulf. Journal of Geophysical Research, 108 (C1), 3004. [CrossRef]

- Tomilin, A. G. (1967). Mammals of the U.S.S.R. and Adjacent Countries. Vol IX Cetacea. Translated from original Russian (1957). Israel Program for Scientific Translations Ltd., Jerusalem. 756pp. [CrossRef]

- True, F. W. (1983). The whalebone whales of the western North Atlantic compared with those occurring in European waters with some observations on the species of the North Pacific. Reprinted from 1904 original . Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C., USA. 332 pp.; 50 Plates.

- Van Bressem, M-F., Minton, G., Collins, T., Willson, A., Baldwin, R. & Van Waerebeek, K. (2014) Tattoo-like skin disease in the endangered subpopulation of the humpback whale Megaptera novaeangliae, in Oman (Cetacea: Balaenopteridae). Zoology in the Middle East, 61, 1-8.

- Van Waerebeek, K. & Leaper, R. (2008). Second Report of the IWC Vessel Strike data standardisation Working Group. IWC Scientific Committee document SC/60/BC5, Santiago, Chile, June 2008. 8pp. Available at. [CrossRef]

- Willson, A., Baldwin, R., Cerchio, S., Collins, T., Findlay, K., Gray, H., Godley, B.J., Al-Harthi, S., Kennedy, A., Minton, G., Zerbini, A. & Witt, M. (2015). Research update of satellite tracking studies of male Arabian Sea humpback whales; Oman. IWC Scientific Committee Document SC/66a/SH/22 Rev 1, San Diego, USA, 12 pp.

- Willson, A., Baldwin, R., Collins, T., Godley, B., Minton, G., Al-Harthi, S., Pikesley, S., & Witt, M.(2017). Preliminary ensemble ecological niche modelling of Arabian Sea humpback whale vessel sightings and satellite telemetry data. Document SC/67A/CMP/15 presented to the IWC Scientific Committee, Bled, Slovenia.

| 1 |

Georges Pouchet was a French naturalist who served as Professor of Comparative Anatomy at the National Museum of Natural History, succeeding Paul Gervais in that position. He was particularly interested in the anatomy of cetaceans. |

| 2 |

Mandibles and all postcranial bones were missing |

| 3 |

No catalogue number was visible. The size of the mandible was too small and did not match the holotype skull. However, wedged under the skull, it could not be inspected. |

| 4 |

In Balaenopteridae, the condylus mandibularis articulates posteriad with the zygomatic process of the squamosal at the level of the exoccipital. Hence, mandibular length is only slightly shorter than CBL, explaining the similar % of body length. |

| 5 |

At least in some juvenile Antarctic minke whales Balaenoptera bonaerensis Burmeister, 1867 there is neither any expansion (e.g. specimen KVW-2298 deposited at CEPEC, Pucusana, Peru). Unpublished data. |

Figure 1.

Stranding location (red dot) of the holotype whale specimen of Megaptera indica Gervais, 1883, reported as ‘baie de Basora’ (Gervais, 1883a) and ‘baie de Bassora’ (Gervais, 1883b and 1888) in the Chat-el-Arab river delta, interpreted as present-day Basrah Bay, Iraq, situated at the extreme northwestern end of the Persian/Arabian Gulf.

Figure 1.

Stranding location (red dot) of the holotype whale specimen of Megaptera indica Gervais, 1883, reported as ‘baie de Basora’ (Gervais, 1883a) and ‘baie de Bassora’ (Gervais, 1883b and 1888) in the Chat-el-Arab river delta, interpreted as present-day Basrah Bay, Iraq, situated at the extreme northwestern end of the Persian/Arabian Gulf.

Figure 2.

Dorsoposteriad view of the cranium (holotype) of Megaptera indica. It shows the occipital condyles (CON), foramen magnum (FMA), exoccipital (EXOC), supraoccipital (SPO), frontal bone (FRO) with orbit (ORB), postorbital process of frontal (POP) and damaged fronto-nasal processes of maxillae (FNP). Scale is 50 cm. Photo ©KVW.

Figure 2.

Dorsoposteriad view of the cranium (holotype) of Megaptera indica. It shows the occipital condyles (CON), foramen magnum (FMA), exoccipital (EXOC), supraoccipital (SPO), frontal bone (FRO) with orbit (ORB), postorbital process of frontal (POP) and damaged fronto-nasal processes of maxillae (FNP). Scale is 50 cm. Photo ©KVW.

Figure 3.

Dorsolateral view of the M. indica holotype skull showing multiple cranial bones, including the right frontal bone (FRO), the (incomplete) fronto-nasal process (FNP) of the right maxilla, the parietal (PAR), occipital bone (OCC), and supraoccipital (SPO) at the skull’s crest. Note the prominent supraorbital process (SOP) of the frontal bone (FRO) narrowing markedly towards the orbit. The anterior margin of the squamosal (SQ) is smoothly rounded and U-shaped including the zygomatic process (ZYP). Both features are diagnostic for Megaptera. Scale shown is 50 cm (10 x 5 cm). Photo © KVW.

Figure 3.

Dorsolateral view of the M. indica holotype skull showing multiple cranial bones, including the right frontal bone (FRO), the (incomplete) fronto-nasal process (FNP) of the right maxilla, the parietal (PAR), occipital bone (OCC), and supraoccipital (SPO) at the skull’s crest. Note the prominent supraorbital process (SOP) of the frontal bone (FRO) narrowing markedly towards the orbit. The anterior margin of the squamosal (SQ) is smoothly rounded and U-shaped including the zygomatic process (ZYP). Both features are diagnostic for Megaptera. Scale shown is 50 cm (10 x 5 cm). Photo © KVW.

Figure 4.

Dorsal view of M. indica skull exposing: occipital bone (OCC), vertex (VER), frontal (FRO), parietal (PAR), squamosal (SQ) with zygomatic process (ZYG), fronto-nasal process (FNP) of maxilla (MAX) and vomer (VOM), which is incomplete and fractured but assembled with metal components. Naso-frontal processes of maxillae, although damaged, do not expand in width posteriad, characteristic for Megaptera. Premaxillae and nasals are missing. Two unrelated bones were present in the crate: non-matching left mandible (man) of a smaller balaenopterid; mandible of a small-sized Physeter macrocephalus (Phys). Photo © KVW.

Figure 4.

Dorsal view of M. indica skull exposing: occipital bone (OCC), vertex (VER), frontal (FRO), parietal (PAR), squamosal (SQ) with zygomatic process (ZYG), fronto-nasal process (FNP) of maxilla (MAX) and vomer (VOM), which is incomplete and fractured but assembled with metal components. Naso-frontal processes of maxillae, although damaged, do not expand in width posteriad, characteristic for Megaptera. Premaxillae and nasals are missing. Two unrelated bones were present in the crate: non-matching left mandible (man) of a smaller balaenopterid; mandible of a small-sized Physeter macrocephalus (Phys). Photo © KVW.

Figure 5.

Dorsal view of the basioccipital area including the occipital condyles. Note the (abnormal) small foramen at the upper rim of the left. condyle (arrow), set among mild idiopathic bone lysis. Photo © KVW.

Figure 5.

Dorsal view of the basioccipital area including the occipital condyles. Note the (abnormal) small foramen at the upper rim of the left. condyle (arrow), set among mild idiopathic bone lysis. Photo © KVW.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).