Submitted:

18 September 2025

Posted:

18 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

- i)

-

First dimension: intakes.Intakes were explored in terms of weight consumed (grams) and energy intake (kcal, kJ). Average daily intakes were computed for each sub-group, for ‘all dairy’, i.e., all sub-groups except PBDA, and ‘all soft dairy’, i.e., milk, yoghurt, fermented dairy, and soft cheese.

- ii)

-

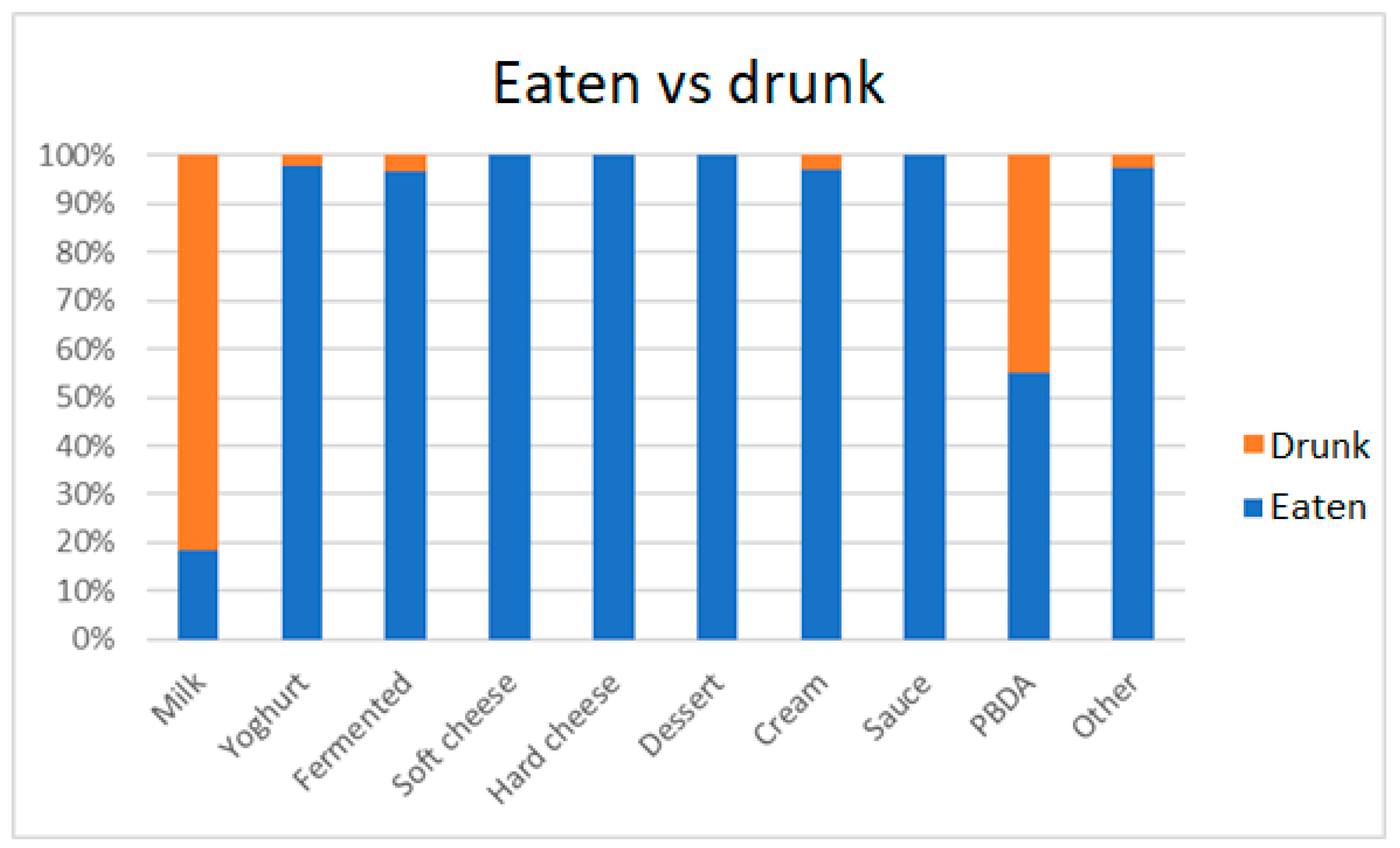

Second dimension: “eaten” vs “drunk”.All fluid products, whose texture is liquid, that can be consumed alone or with other liquid products, e.g., coffee, were classified as "drunk". Products whose texture does not allow them to be consumed as a beverage, but instead are "spoonable", or whose consistency is solid, were classified as "eaten".

- iii)

-

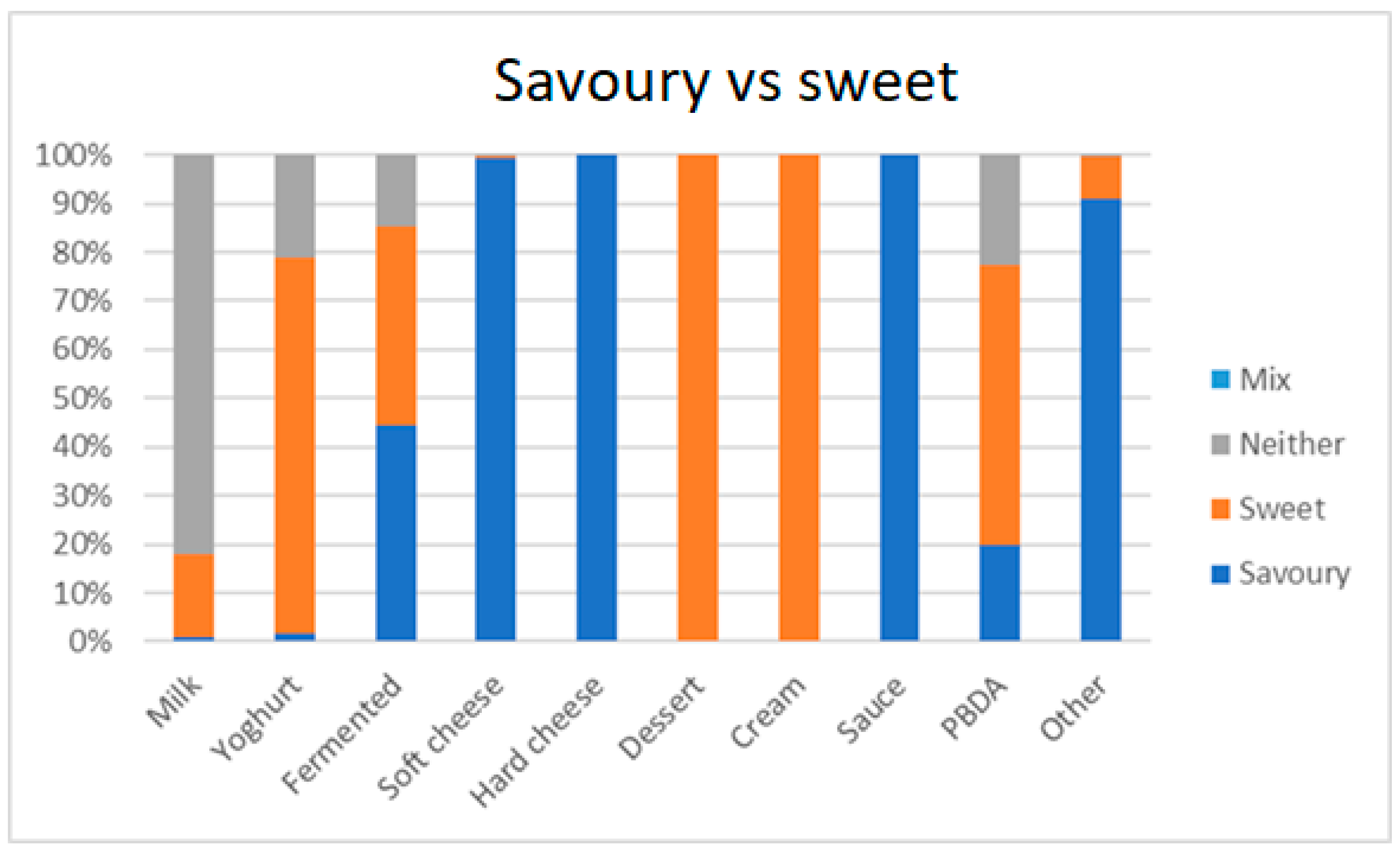

Third dimension: “savoury” vs “sweet”.All entries were checked one by one and classified according to the foods they were consumed with. They were classified as “savoury” if consumed with other savoury foods, e.g., pasta; they were classified as “sweet” if the other foods were sugary, e.g., jam. A third label was added to classify dairy entries when not paired with any food or paired with food neither 'savoury' nor 'sweet', i.e., coffee, cocoa, tea. In these cases, entries were classified as "neither".

- iv)

-

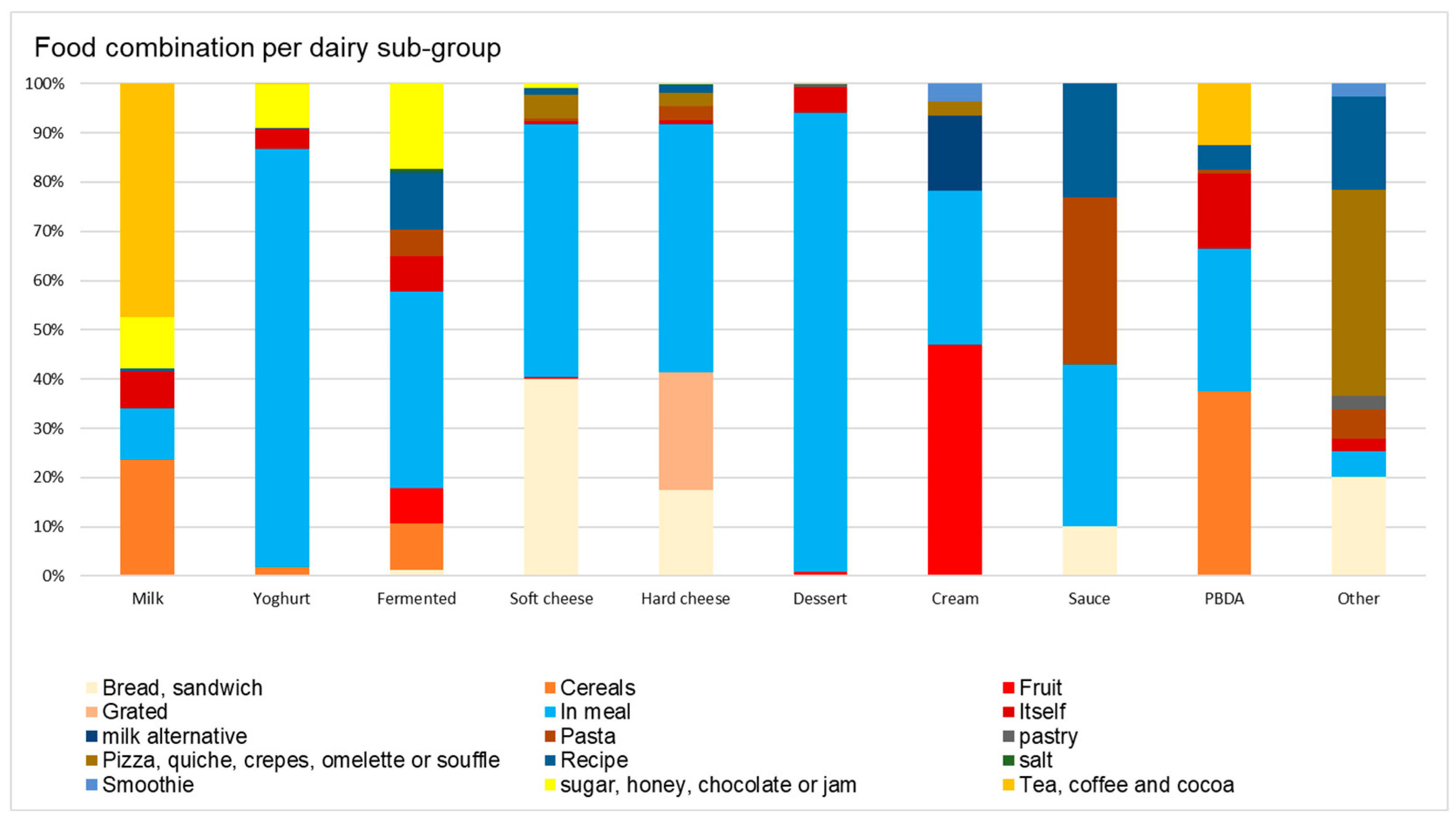

Fourth dimension: “combined with other foods” vs “by itself”.Each dairy entry was classified based on the foods it was paired with. When the dairy was consumed by itself in a standalone meal, it was classified as “by itself”; when the dairy was consumed in a meal and the accompanying foods were specified, it was classified according to those foods, e.g., “with fruit”. When dairy was consumed as part of a meal, but no details on the accompanying foods were stated, it was classified as “in a meal”.

- v)

-

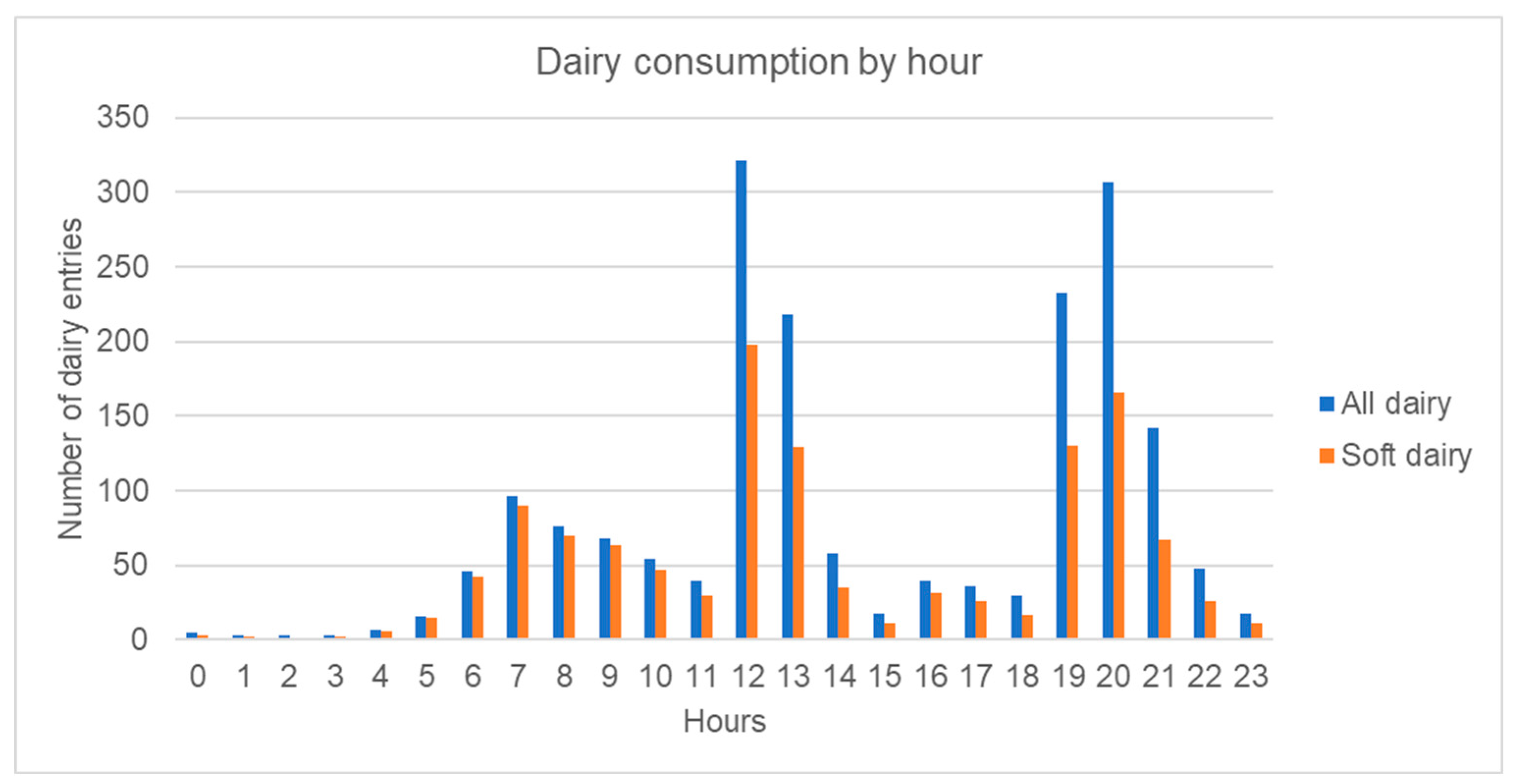

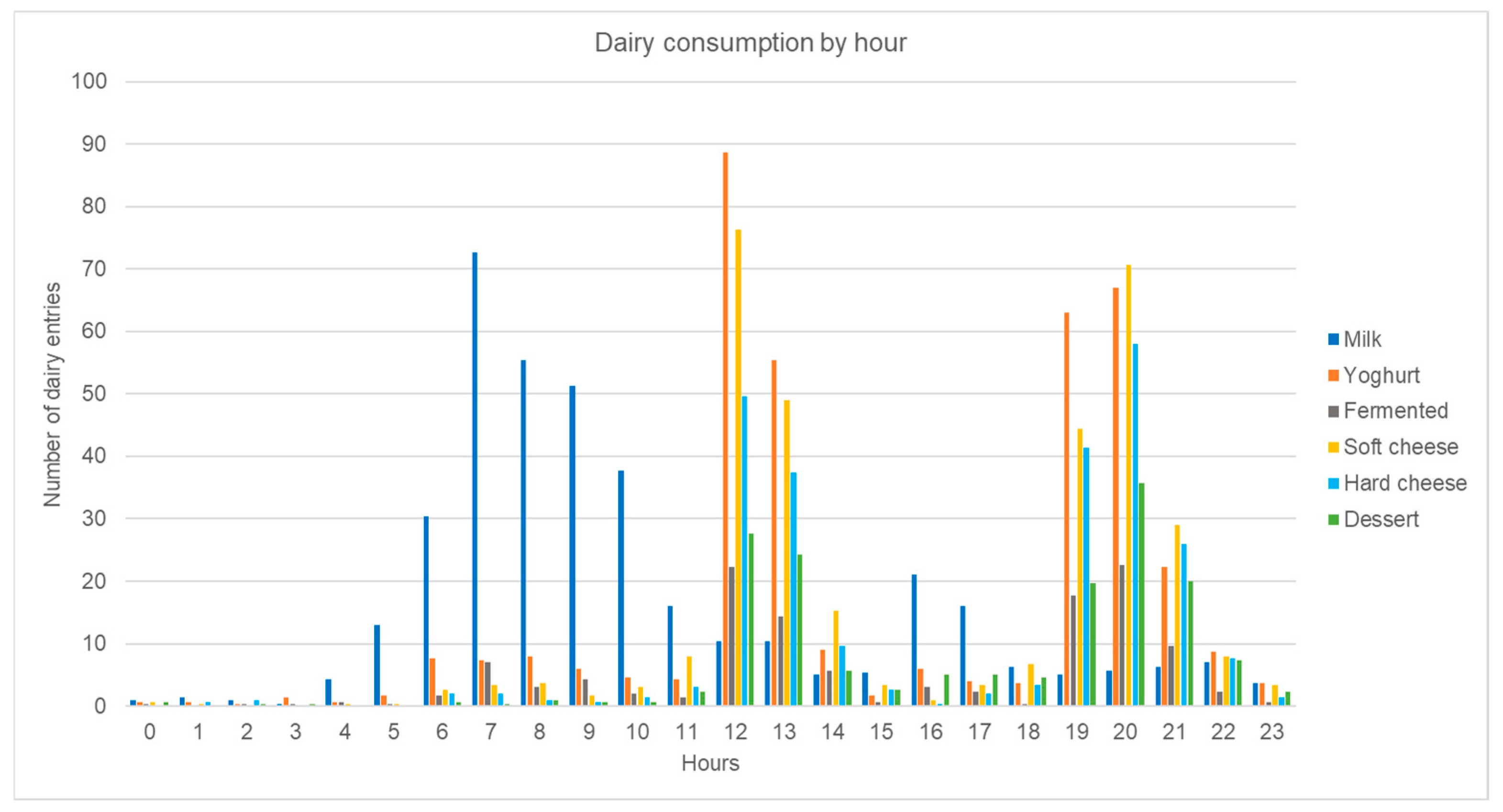

Fifth dimension: time of day of the consumption (in hours, from 0 to 23).Time of day was explored for total dairy, soft dairy, and each soft dairy product individually, hard cheese, and desserts.

- vi)

-

Sixth dimension: “meal” vs “snack”.This dimension was derived from dimension v) time of day, where meals and snacks were defined based on the time of consumption, considering traditional mealtimes in France. Notably, the daily meal structure is shared by most of the population and includes three main meals (i.e., breakfast, lunch, and dinner) at the same hours of the day [67]. A snack was defined following consumption at any other time [66,68,69].

3. Results

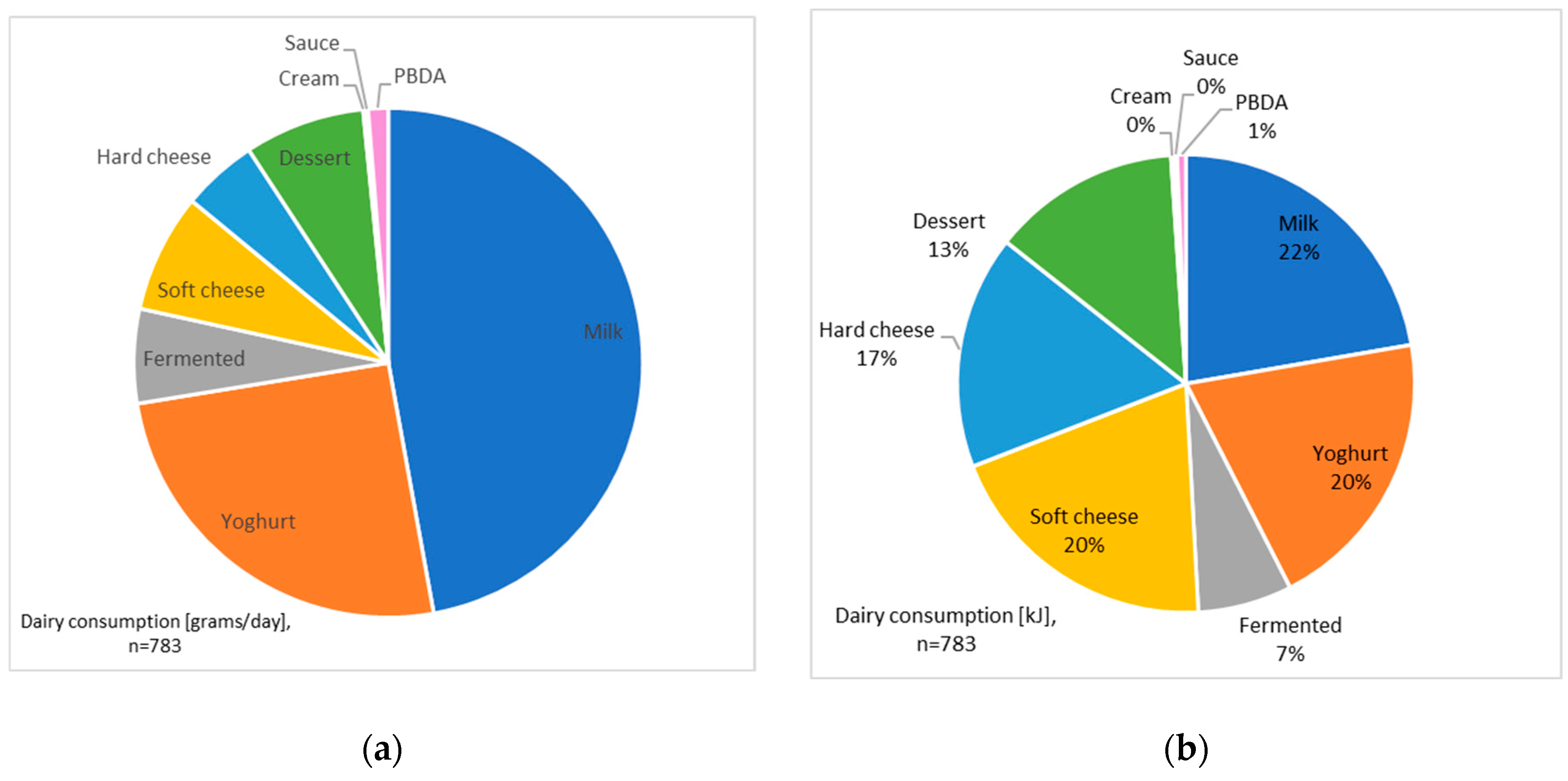

3.1. First Dimension: Intakes

3.2. Eating Patterns

3.2.1. Second Dimension: “Eaten” vs “Drunk”

3.2.2. Third Dimension: “Savoury” vs “Sweet”

3.2.3. Fourth Dimension: “In Combination with Other Foods” vs “By Itself”

3.2.4. Fifth Dimension: Time of Day

3.2.5. Sixth Dimension: “Meals” vs “Snacks”

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| INCA | French Individual and National Survey Consumption (études Individuelles Nationales des Consommations Alimentaires) |

| Kcal | Kilocalories |

| kJ | Kilojoules, 1Kcal = 4.186 kJ. |

| PBDA | Plant-Based Dairy Alternatives |

| PNNS | French National Nutrition and Health Program (Programme National Nutrition Santé) |

| UK | United Kingdom |

References

- Rozenberg S, Body J-J, Bruyère O, Bergmann P, Brandi M L, Cooper C, Devogelaer J-P, Gielen E, Goemaere S, Kaufman J-M, Rizzoli R and Reginster J-Y 2016 Effects of Dairy Products Consumption on Health: Benefits and Beliefs—A Commentary from the Belgian Bone Club and the European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis, Osteoarthritis and Musculoskeletal Diseases Calcif Tissue Int 98 1–17.

- Clegg M E, Tarrado Ribes A, Reynolds R, Kliem K and Stergiadis S 2021 A comparative assessment of the nutritional composition of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives available for sale in the UK and the implications for consumers’ dietary intakes Food Research International 148 110586. [CrossRef]

- Hoffman J R and Falvo M J 2005 Protein - Which is best? nternational Society of Sports Nutrition Symposium. Symposium - Macronutrient Utilization During Exercise: Implications For Performance And Supplementation vol 3 (Las Vegas, NV, USA: Journal of Sports Science and Medicine) pp 118–30.

- Mozaffarian D 2019 Dairy Foods, Obesity, and Metabolic Health: The Role of the Food Matrix Compared with Single Nutrients Advances in Nutrition 10 917S-923S. [CrossRef]

- Prentice A M 2014 Dairy products in global public health The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 99 1212S-1216S. [CrossRef]

- Tunick M H and Van Hekken D L 2015 Dairy Products and Health: Recent Insights J. Agric. Food Chem. 63 9381–8. [CrossRef]

- Savaiano D A and Hutkins R W 2021 Yogurt, cultured fermented milk, and health: a systematic review Nutrition Reviews 79 599–614.

- Kok C R and Hutkins R 2018 Yogurt and other fermented foods as sources of health-promoting bacteria Nutrition Reviews 76 4–15.

- Das C, Das P P and Kambhampati S B S 2023 Sarcopenia and Osteoporosis JOIO 57 33–41.

- Hereford T, Kellish A, Samora J B and Reid Nichols L 2024 Understanding the importance of peak bone mass Journal of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America 7 100031. [CrossRef]

- Wallace T C, Bailey R L, Lappe J, O’Brien K O, Wang D D, Sahni S and Weaver C M 2021 Dairy intake and bone health across the lifespan: a systematic review and expert narrative Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 61 3661–707. [CrossRef]

- Zingone F, Bucci C, Iovino P and Ciacci C 2017 Consumption of milk and dairy products: Facts and figures Nutrition 33 322–5.

- Lad S S, Aparnathi K D, Mehta B and Velpula S 2017 Goat Milk in Human Nutrition and Health – A Review Int.J.Curr.Microbiol.App.Sci 6 1781–92. [CrossRef]

- Raynal-Ljutovac K, Lagriffoul G, Paccard P, Guillet I and Chilliard Y 2008 Composition of goat and sheep milk products: An update Small Ruminant Research 79 57–72. [CrossRef]

- Gerber P J and Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2013 Tackling climate change through livestock: a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

- FAO 2022 FAO Strategy on Climate Change 2022–2031 (Rome).

- Gaillac R and Marbach S 2021 The carbon footprint of meat and dairy proteins: A practical perspective to guide low carbon footprint dietary choices Journal of Cleaner Production 321 128766.

- Berners-Lee M, Hoolohan C, Cammack H and Hewitt C N 2012 The relative greenhouse gas impacts of realistic dietary choices Energy Policy 43 184–90. [CrossRef]

- Haenlein G F W 2007 About the evolution of goat and sheep milk production Small Ruminant Research 68 3–6.

- Peacock C and Sherman D M 2010 Sustainable goat production—Some global perspectives Small Ruminant Research 89 70–80.

- Bylund G 1995 Dairy Processing Handbook (AB S-221 86 Lund, Sweden: Tetra Pak Processing Systems).

- Weltgesundheitsorganisation and FAO 2011 Milk and milk products. Second edition. (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations).

- Almena-Aliste M and Mietton B 2017 Cheese Classification, Characterization, and Categorization: A Global Perspective Microbiol Spectrum` 2 29.

- Paul A A, Kumar S, Kumar V and Sharma R 2020 Milk Analog: Plant based alternatives to conventional milk, production, potential and health concerns Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 60 3005–23. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda M, Etaio I, Valentin D, Dacremont C, Zannoni M, Tupasela T, Lilleberg L and Pérez-Elortondo F J 2021 Effect of consumers’ origin on perceived sensory quality, liking and liking drivers: A cross-cultural study on European cheeses Food Quality and Preference 87 104047.

- Palacios O M, Badran J, Drake M A, Reisner M and Moskowitz H R 2009 Consumer acceptance of cow’s milk versus soy beverages: impact of ethnicity, lactose tolerance and sensory preference segmentation Journal of Sensory Studies 24 731–48.

- Cardello A V, Llobell F, Jin D, Ryan G S and Jaeger S R 2024 Sensory drivers of liking, emotions, conceptual and sustainability concepts in plant-based and dairy yoghurts Food Quality and Preference 113 105077.

- Brennan L, Francis C, Jenkins E L, Schivinski B, Jackson M, Florence E, Parker L, Langley S, Lockrey S, Verghese K, Phan-Le N T, Hill A and Ryder M 2023 Consumer Perceptions of Food Packaging in Its Role in Fighting Food Waste Sustainability 15 1917.

- Franzon C, Dougkas A, Memery J, Prigent J and Appleton K M 2024 A qualitative study to explore and identify reasons for dairy consumption and non-consumption among young adults (18-30 years old) in the UK and France Journal of Nutritional Science 13 1–10.

- Cruwys T, Bevelander K E and Hermans R C J 2015 Social modeling of eating: A review of when and why social influence affects food intake and choice Appetite 86 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Racey M, Bransfield J, Capello K, Field D, Kulak V, Machmueller D, Preyde M and Newton G 2017 Barriers and Facilitators to Intake of Dairy Products in Adolescent Males and Females With Different Levels of Habitual Intake Global Pediatric Health 4 2333794X1769422.

- Douglas M 1972 Deciphering a Meal (The MIT Press on behalf of American Academy of Arts & Sciences).

- Harris M 1998 Good to eat: Riddles of food and culture (Waveland Press). [CrossRef]

- Chinea C, Suárez E and Hernández B 2020 Meaning of food in eating patterns BFJ 122 3331–41. [CrossRef]

- Holm L, Skov Luridsen D, Gronow J, Khama N, Kjærnes U, Bøker Lund T, Mäkelä J and Niva M 2019 The food we eat Everyday Eating in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. A Comparative Study of Meal Patterns 1997-2012 (Bloomsbury Publishing) p 248.

- Visser M 2017 The rituals of dinner. The origin, evolution, eccentrities and meaning of table manners. (Penguin Books).

- Poulain J P 2002 The contemporary diet in France: “de-structuration” or from commensalism to “vagabond feeding” Appetite 39 43–55.

- Delfosse C 2012 La France et ses terroirs. Un siècle de débats sur les produits et leurs liens à l’espace: Pour N° 215-216 63–74.

- Gray A 2010 “The Greatest Ordeal”: Using Biography to Explore the Victorian Dinner Post-Medieval Archaeology 44 255–72.

- Harding G 2021 Dinner Is the Great Trial: Sociability and Service à la Russe in the Long Nineteenth Century.

- Almerico G M 2014 Food and identity: Food studies, cultural, and personal identity Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies 8.

- Duncan S E 1998 Dairy Products: The Next Generation. Altering the Image of Dairy Products Through Technology Journal of Dairy Science 81 877–83. [CrossRef]

- Pulina G, Milán M J, Lavín M P, Theodoridis A, Morin E, Capote J, Thomas D L, Francesconi A H D and Caja G 2018 Invited review: Current production trends, farm structures, and economics of the dairy sheep and goat sectors Journal of Dairy Science 101 6715–29. [CrossRef]

- Laila A, Topakas N, Farr E, Haines J, Ma D W, Newton G and Buchholz A C 2021 Barriers and facilitators of household provision of dairy and plant-based dairy alternatives in families with preschool-age children Public Health Nutr. 24 5673–85.

- Kemp B J, White-Flynn T T, Lyons O C, Cronin B E, O’Donovan C B, Donovan C M and Flynn M A T 2017 Is it yoghurt or is it a dessert? Proc. Nutr. Soc. 76 E69.

- Valli C and Traill W B 2005 Culture and food: a model of yoghurt consumption in the EU Food Quality and Preference 16 291–304. [CrossRef]

- Hobbs D A, Durrant C, Elliott J, Givens D I and Lovegrove J A 2020 Diets containing the highest levels of dairy products are associated with greater eutrophication potential but higher nutrient intakes and lower financial cost in the United Kingdom Eur J Nutr 59 895–908. [CrossRef]

- Berners-Lee M, Hoolohan C, Cammack H and Hewitt C N 2012 The relative greenhouse gas impacts of realistic dietary choices Energy Policy 43 184–90. [CrossRef]

- Agence de la transition écologique 2021 Agribalyse dataset, Synthese.

- Our World in Data 2025 “Yearly per capita supply of milk - excluding butter” [dataset]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Food Balances: Food Balances (-2013, old methodology and population)”; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, “Food Balances: Food Balances (2010-)” [original data]. ourworldindata.org.

- European Dairy Association 2021 EDA Factsheet ‘Daily Dairy Recommendations: Are we eating enough dairy?’.

- Weaver C M 2014 How sound is the science behind the dietary recommendations for dairy? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 99 1217S-1222S. [CrossRef]

- Baker I A, Elwood P C, Hughes J, Jones M, Moore F and Sweetnam P M 1980 A randomised controlled trial of the effect of the provision of free school milk on the growth of children. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 34 31–4. [CrossRef]

- Chen G-C, Szeto I M Y, Chen L-H, Han S-F, Li Y-J, Van Hekezen R and Qin L-Q 2015 Dairy products consumption and metabolic syndrome in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies Sci Rep 5 14606. [CrossRef]

- Zhang K and Wu J 2024 Meat–Egg–Dairy Consumption and Frailty among Chinese Older Adults: Exploring Rural/Urban and Gender Differences Nutrients 16 1334.

- Laird E, Casey M C, Ward M, Hoey L, Hughes C F, Mccarroll K, Cunningham C, Strain J J, Mcnulty H and Molloy A M 2017 Dairy intakes in older Irish aduts and effects on vitamin micronutrient status: data from the TUDA study J Nutr Health Aging 21 8.

- Kapaj A 2018 Factors that influence milk consumption world trends and facts uropean Journal of Business, Economics and Accountancy 6.

- Charby J, Hébel P and Vaudaine S 2017 Les produits laitiers en France : évolution du marché et place dans la diète Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique 52 S25–34.

- Ministère des solidarités et de la santé 2019 Programme National Nutrition Santé 2019-2023 (PNNS4), Annexe 4 (Ministère du travail, de la santé, des solidarités et de famille, France).

- Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire (ANSES) 2017 INCA 3 : Evolution des habitudes et modes de consommation, de nouveaux enjeux en matière de sécurité sanitaire et de nutrition.

- Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire (ANSES) 2017 Étude individuelle nationale des consommations alimentaires 3 (INCA 3) - Avis de l’Anses - Rapport d’expertise collective (Agence nationale de sécurité sanitaire (ANSES)).

- Ministère du travail, de la santé, des solidarités et de famille, France 2025 Programme national nutrition santé (PNNS) - Professionnels.

- Tamime A 2002 Fermented milks: a historical food with modern applications–a review Eur J Clin Nutr 56 S2–15. [CrossRef]

- Public Health England 2016 The Eatwell Guide.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025.

- Leech R M, Worsley A, Timperio A and McNaughton S A 2015 Characterizing eating patterns: a comparison of eating occasion definitions The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 102 1229–37. [CrossRef]

- Poulain J P 2002 The contemporary diet in France: “de-structuration” or from commensalism to “vagabond feeding” Appetite 39 43–55.

- Hess J M, Jonnalagadda S S and Slavin J L 2016 What Is a Snack, Why Do We Snack, and How Can We Choose Better Snacks? A Review of the Definitions of Snacking, Motivations to Snack, Contributions to Dietary Intake, and Recommendations for Improvement Advances in Nutrition 7 466–75. [CrossRef]

- Ovaskainen M-L, Reinivuo H, Tapanainen H, Hannila M-L, Korhonen T and Pakkala H 2006 Snacks as an element of energy intake and food consumption Eur J Clin Nutr 60 494–501. [CrossRef]

- Observatoire Economique de l’Achat Publique 2015 Recommandation nutrition groupe d’étude des marchès de restauration collective et nutrition GEM-RCN. Version 2.0 – Juillet 2015.

- Ministère des solidarités et de la santé 2018 Programme National Nutrition Santé (PNNS) 2019-2023.

- ANSES 2016 Ciqual Table de composition nutritionnelle des aliments.

- European Commission 2023 MMO Economic Board. Milk market observatory. Annex: Milk market situation.

- Szczepańska E, Janota B, Wlazło M and Czapla M 2021 Eating behaviours, the frequency of consumption of selected food products, and selected elements of lifestyle among young dancers Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 67–76.

- Cesbron-Lavau E, Lubrano-Lavadera A-S, Braesco V and Deschamps E 2017 Fromages blancs, petits-suisses et laits fermentés riches en protéines Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique 52 33–40.

- Bourlioux P 2007 Histoire des laits fermentes Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique 42 6.

- Tamime A 2002 Fermented milks: a historical food with modern applications–a review Eur J Clin Nutr 56 S2–15. [CrossRef]

- Herpin N 1988 Le repas comme institution: Compte rendu d’une enquête exploratoire Revue Française de Sociologie 29 503. [CrossRef]

- Roy B D 2008 Milk: the new sports drink? A Review Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition 5 15.

- Ng S W, Ni Mhurchu C, Jebb S A and Popkin B M 2012 Patterns and trends of beverage consumption among children and adults in Great Britain, 1986–2009 Br J Nutr 108 536–51.

- McCarthy K S, Parker M, Ameerally A, Drake S L and Drake M A 2017 Drivers of choice for fluid milk versus plant-based alternatives: What are consumer perceptions of fluid milk? Journal of Dairy Science 100 6125–38. [CrossRef]

- Corvera-Paredes B, Sánchez-Reséndiz A I, Medina D I, Espiricueta-Candelaria R S, Serna-Saldívar S and Chuck-Hernández C 2022 Soft Tribology and Its Relationship With the Sensory Perception in Dairy Products: A Review Front. Nutr. 9 874763. [CrossRef]

- Kupiec B and Revell B 1998 Speciality and artisanal cheeses today: the product and the consumer British Food Journal 100 236–43. [CrossRef]

- Conti-Silva A C and Souza-Borges P K D 2019 Sensory characteristics, brand and probiotic claim on the overall liking of commercial probiotic fermented milks: Which one is more relevant? Food Research International 116 184–9.

- Farag M A, Jomaa S A, Abd El-Wahed A and R. El-Seedi H 2020 The Many Faces of Kefir Fermented Dairy Products: Quality Characteristics, Flavour Chemistry, Nutritional Value, Health Benefits, and Safety Nutrients 12 346.

- Saint-Eve A, Leclercq H, Berthelo S, Saulnier B, Oettgen W and Delarue J 2016 How much sugar do consumers add to plain yogurts? Insights from a study examining French consumer behavior and self-reported habits Appetite 99 277–84. [CrossRef]

- Michaud C, Baudier F, Guilbert P, Carel D, Le Bihan G, Gautier A and Delamaire C 2004 Les repas des français : résultats du baromètre santé nutrition 2002 Cahiers de Nutrition et de Diététique 39 203–9.

- Michels N, De Henauw S, Beghin L, Cuenca-García M, Gonzalez-Gross M, Hallstrom L, Kafatos A, Kersting M, Manios Y, Marcos A, Molnar D, Roccaldo R, Santaliestra-Pasías A M, Sjostrom M, Reye B, Thielecke F, Widhalm K and Claessens M 2016 Ready-to-eat cereals improve nutrient, milk and fruit intake at breakfast in European adolescents Eur J Nutr 55 771–9. [CrossRef]

- Ozdogan Y, Yardimci H and Ozcelik A O 2017 Young adults’ milk consumption habits and knowledge about milk Studies on Ethno-Medicine 11 106–13.

- Rubio-Martín E, García-Escobar E, Ruiz De Adana M-S, Lima-Rubio F, Peláez L, Caracuel A-M, Bermúdez-Silva F-J, Soriguer F, Rojo-Martínez G and Olveira G 2017 Comparison of the Effects of Goat Dairy and Cow Dairy Based Breakfasts on Satiety, Appetite Hormones, and Metabolic Profile Nutrients 9 877.

- Blondin S A, Goldberg J P, Cash S B, Griffin T S and Economos C D 2018 Factors Influencing Fluid Milk Waste in a Breakfast in the Classroom School Breakfast Program Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 50 349-356.e1. [CrossRef]

- Fagt S, Matthiessen J, Thyregod C, Kørup K and Biltoft-Jensen A 2018 Breakfast in Denmark. Prevalence of Consumption, Intake of Foods, Nutrients and Dietary Quality. A Study from the International Breakfast Research Initiative Nutrients 10 1085. [CrossRef]

- Kupiec B and Revell B 1998 Speciality and artisanal cheeses today: the product and the consumer British Food Journal 100 236–43. [CrossRef]

- Murphy M, Cowan C, Meehan H and O’Reilly S 2004 A conjoint analysis of Irish consumer preferences for farmhouse cheese British Food Journal 106 288–300. [CrossRef]

- Jaeger S R and Porcherot C 2017 Consumption context in consumer research: methodological perspectives Current Opinion in Food Science 15 30–7.

- Borghini A 2015 What Is a Recipe? J Agric Environ Ethics 28 719–38.

- Garabuau-Moussaoui I 2001 La cuisine des jeunes : désordre alimentaire, identité générationnelle et ordre social Anthropology of food - Traditions et identités alimentaires locales 0.

- Hasan B, Thompson W G, Almasri J, Wang Z, Lakis S, Prokop L J, Hensrud D D, Frie K S, Wirtz M J, Murad A L, Ewoldt J S and Murad M H 2019 The effect of culinary interventions (cooking classes) on dietary intake and behavioral change: a systematic review and evidence map BMC Nutr 5 29. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Kim T and Jung H 2022 The Relationships between Food Literacy, Health Promotion Literacy and Healthy Eating Habits among Young Adults in South Korea Foods 11 2467.

- Delfosse C 2012 La diffusion mondiale de la consommation de fromage, de l’ingrédient de pizza au produit de terroir: Pour N° 215-216 123–9. [CrossRef]

- Fumey G 2012 La France, un plateau de fromages: La Géographie N° 1544 25–7. [CrossRef]

- Forwood S E 2025 Solving the diet problem: meals as food choice heuristics for behaviour change Current Opinion in Food Science 64 101317.

- Fatemi B, Duval Q, Girdhar R, Drozdzal M and Romero-Soriano A 2023 Learning to Substitute Ingredients in Recipes.

- Jung M E, Mistry C, Bourne J E, Perrier M-J, Martin Ginis K A and Latimer-Cheung A E 2015 A qualitative investigation of adults’ perceived benefits, barriers and strategies for consuming milk and milk products Health Education Journal 74 364–78.

- Glanz K 2004 Increasing fruit and vegetable intake by changing environments, policy and pricing: restaurant-based research, strategies, and recommendations*1 Preventive Medicine 39 88–93. [CrossRef]

- Glanz K and Mullis R M 1988 Environmental Interventions to Promote Healthy Eating: A Review of Models, Programs, and Evidence Health Education Quarterly 15 395–415. [CrossRef]

- Mandracchia F, Tarro L, Llauradó E, Valls R M and Solà R 2021 Interventions to Promote Healthy Meals in Full-Service Restaurants and Canteens: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Nutrients 13 1350. [CrossRef]

- Rozman U, Lorber M, Bolha A, Bahar J B, Lavrič M and Turk S Š 2025 Sustainability aspects of food and drinks offered in vending machines at Slovenian universities Front. Nutr. 12 1439690. [CrossRef]

- Whatnall M, Fozard T, Kolokotroni K Z, Marwood J, Evans T, Ells L J and Burrows T 2022 Understanding eating behaviours, mental health and weight change in young adults: protocol paper for an international longitudinal study BMJ Open 12 e064963. [CrossRef]

- Calabro R, Kemps E, Prichard I and Tiggemann M 2024 Vending machine backgrounds: nudging healthier beverage choices Curr Psychol 43 1733–42.

- Bos C, Van Der Lans I A, Van Kleef E and Van Trijp H C M 2018 Promoting healthy choices from vending machines: Effectiveness and consumer evaluations of four types of interventions Food Policy 79 247–55. [CrossRef]

- Rosi A, Zerbini C, Pellegrini N, Scazzina F, Brighenti F and Lugli G 2017 How to improve food choices through vending machines: The importance of healthy food availability and consumers’ awareness Food Quality and Preference 62 262–9. [CrossRef]

- Carrad A M, Louie J C, Milosavljevic M, Kelly B and Flood V M 2015 Consumer support for healthy food and drink vending machines in public places Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 39 355–7. [CrossRef]

- Palascha A and Chang B P I 2024 Which messages about healthy and sustainable eating resonate best with consumers with low socio-economic status? Appetite 198 107350.

- Myers J, Schweiger D and Clark S 2024 Dairy nutrition educational messages help increase dairy product knowledge, purchasing, and consumption JDS Communications 5 13–7. [CrossRef]

| N=783 | Average weight consumed [g/day] | Average energy intake [kcal/day] | Average energy intake [kJ/day] |

|---|---|---|---|

| All dairy | 246 | 269 | 1,126 |

| Soft dairy | 215 | 187 | 783 |

| Milk | 118 | 60 | 252 |

| Yoghurt | 63 | 54 | 227 |

| Fermented dairy | 15 | 18 | 75.3 |

| Soft cheese | 19 | 54 | 227 |

| Hard cheese | 12 | 45 | 187 |

| Dessert | 19 | 36 | 151 |

| Cream | 0.2 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| Sauce | 0.5 | 0.6 | 2.5 |

| PBDA | 3 | 2 | 7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).