1. Introduction

Computed tomography has become a frontline diagnostic tool in emergency departments, particularly for patients with acute abdominal pain. The detailed anatomical imaging provided by abdominopelvic CT (APCT) facilitates accurate diagnosis of acute conditions. However, the comprehensive scope of APCT also leads to the identification of incidental findings (IFs)—abnormalities unrelated to the patient’s presenting symptoms. Importantly, IFs encompass any such unrelated abnormality regardless of clinical significance; while many IFs are benign or clinically unimportant, a subset may represent significant pathology requiring intervention or follow-up. Prior studies estimate that approximately 20–40% of emergency CT examinations reveal at least one incidental finding, with some reports of abdominal CTs in Emergency Department (ED) patients showing IF rates up to 34–43% and even as high as 56.3% in certain populations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. These findings underscore the need for a systematic approach to reviewing all APCT images to recognize potentially significant incidental abnormalities and ensure appropriate follow-up.

Despite their potential clinical importance, IFs are often underreported or inadequately managed in the ER setting. Emergency physicians must prioritize acute, symptomatic conditions, and time constraints can lead to incidental findings being overlooked or deferred. Prior research indicates that only about 20–25% of ED patients with incidental findings receive proper documentation and arranged outpatient follow-up, highlighting the risk of missed diagnoses [

1,

6,

7]. Military hospitals may face additional challenges: limited availability of specialist radiologists, high patient turnover, and frequent relocations of personnel can all contribute to IFs being missed or not conveyed effectively. In South Korea, mandatory military service places young adult males in environments where access to comprehensive medical facilities is limited. A recent survey by Bae et al. found that nearly one in four Korean soldiers (24.8%) reported unmet healthcare needs during military service, a rate 6.8 times higher than among civilian males in their twenties (3.65%) [

8,

9]. Such limitations in military healthcare delivery underscore the importance of promptly identifying and clearly communicating IFs to prevent adverse outcomes.

This unique population is presumed healthy due to rigorous pre-enlistment screening, yet they operate under unique physical and environmental stressors [

10]. Therefore, understanding the prevalence of underlying pathologies is paramount for maintaining force readiness. To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize the spectrum of APCT incidental findings in this critical population [

11].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We performed a retrospective case series analysis of Korean soldiers who presented to the ER of our military hospital with acute abdominal pain between January 2021 and December 2022. Our hospital is the largest of 17 military hospitals in South Korea (666 beds, 130 physicians excluding trainees). The Institutional Review Board (IRB No. AFCH 2023-03-006) approved the study and waived informed consent due to the retrospective design. This cohort comprised all eligible cases from our center and represents a convenience sample.

Inclusion criteria were: (i) male Korean soldiers aged 18–28 years; (ii) ER presentation primarily for acute abdominal pain; (iii) an APCT scan performed at our hospital during that visit; and (iv) complete accessible medical records and imaging for review. Patients were excluded if: (a) they had undergone APCT at another facility prior to the ER visit (to ensure findings on our scans were truly incidental and not previously known); (b) medical records or imaging were incomplete, unclear, or insufficient for accurate interpretation; or (c) they were transferred from external hospitals with known abdominal conditions that could confound identification of new incidental findings.

Figure 1 illustrates the patient selection process, with 1,610 patients initially screened, 548 exclusions (primarily due to incomplete imaging data from prior outside scans or corrupted files), and a final cohort of 1,062 patients included for analysis.

2.2. Radiologic Assessment

All APCT images were initially interpreted by board-certified radiologists at the time of care. For this study, two senior radiologist consultants independently re-reviewed each scan in a blinded fashion to identify incidental findings. Incidental findings (IFs) were defined strictly as any radiological abnormalities detected on APCT that were unrelated to the patient’s presenting abdominal symptoms or initial clinical diagnosis, irrespective of clinical relevance. In other words, any abnormal finding not explaining the acute abdominal pain was recorded as an IF. After independent review, any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. We additionally noted which IFs were deemed clinically significant, defined as findings requiring further imaging surveillance, specialist referral, or surgical/medical intervention according to established clinical guidelines (e.g., Bosniak classification for renal cysts, Fleischner Society guidelines for pulmonary nodules) [

5,

12].

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). We summarized patient characteristics and IF frequencies using descriptive statistics. The distribution of age was checked for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test and visual histogram inspection); as age was not normally distributed, medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) are reported. Differences in continuous variables were assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test, and differences in categorical variables (e.g., IF prevalence between groups) were assessed with chi-square tests. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additionally, we conducted an exploratory cluster analysis to examine co-occurrence patterns among different IF types. This involved using chi-square tests for association between pairs of IF categories and calculating odds ratios (ORs) where appropriate. We considered an association significant if p<0.05 after any necessary adjustment for multiple comparisons. Significant IF co-occurrences were visualized with a network graph (see Results,

Figure 2) for illustrative purposes. This analysis was exploratory and hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory.

Artificial intelligence (ChatGPT, OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used only to assist in language editing and formatting. No part of the scientific analysis or interpretation was generated by AI.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Inclusion and Characteristics

A total of 1,062 young male soldiers with acute abdominal pain met the inclusion criteria and underwent APCT at the ER during the two-year study period. This final sample represents all eligible cases from our center (convenience sample). IFs – defined as radiological abnormalities unrelated to the initial abdominal complaint (irrespective of clinical importance) – were identified in 218 of these 1,062 patients, corresponding to an overall incidental finding prevalence of 20.5%. The remaining 844 patients (79.5%) had no incidental findings on their APCT. The age distribution of the cohort was tightly clustered (median age 21 years, IQR 20–22) due to the narrow age range of conscripted soldiers in Korea. Patients with IFs had a median age of 21 (IQR 20–22), which did not differ significantly from those without IFs (median 21, IQR 20–22; p = 0.14). All patients were male by study design, and other baseline clinical characteristics did not significantly differ between those with and without IFs. The demographic and baseline characteristics of the study population are summarized in

Table 1.

3.1.1. Incidental Findings on APCT: Frequencies and Types

The anatomical distribution and frequency of incidental findings on APCT are detailed in

Table 2. Renal-system IFs were most prevalent. Renal cysts were the single most common incidental finding, present in 66 patients (6.2% of the entire cohort) [

3,

13]. These cysts were predominantly simple benign cysts (Bosniak class I in 56 cases and class II in 5 cases). Notably, three renal cysts (0.3% of the cohort) were classified as Bosniak II-F, which are indeterminate and carry a potential malignancy risk, prompting a recommendation for scheduled radiologic follow-up. In addition to simple cysts, we incidentally identified two significant renal conditions: one case of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) and one case of medullary cystic kidney disease (MCKD). These were newly discovered in our young population (0.1% each of the total sample) and were clinically important, leading to referrals to specialized civilian centers for further management. Asymptomatic renal calculi (kidney stones) were also relatively frequent incidental findings, occurring in 20 patients (1.9%). While these stones were unrelated to the presenting pain (and thus truly incidental), their presence underscores the importance of documenting even benign IFs, as they could become symptomatic in the future.

Hepatobiliary incidental findings constituted the second most prevalent group. Hepatic IFs were found in 80 patients (7.5% of the total cohort), including fatty liver in 43 patients (4.0%) and hepatic cysts in 28 patients (2.6%). Nine patients (0.8%) had small hepatic hemangiomas. These liver findings were generally benign; for instance, none of the hepatic cysts were large (>4 cm) or symptomatic, and thus none required intervention [

14,

15]. Gallbladder-related IFs were identified in 16 patients (1.5%). This included 9 patients (0.8%) with asymptomatic gallstones and 7 patients (0.7%) with gallbladder adenomyomatosis. Gallbladder adenomyomatosis, although usually benign, can radiologically mimic malignancy or occasionally lead to symptoms [

16]. Its incidental detection in our young cohort was deemed clinically significant enough to warrant periodic ultrasound surveillance to monitor for any changes, given that 0.7% of all patients had this finding.

Less common but noteworthy incidental findings in the pancreatic and adrenal systems were also observed. Two patients (0.2%) had pancreatic lesions detected incidentally: one case of an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) of the pancreas and one pancreatic cyst. Both pancreatic lesions were clinically significant IFs given their potential for malignant transformation; we recommended specialist gastroenterology follow-up for these (each representing 0.1% of the total population). Adrenal gland lesions were found in four patients. Two patients (0.2%) had adrenal hyperplasia and two (0.2%) had adrenal adenomas incidentally noted on the APCT. One of the adrenal adenomas was larger than 2 cm, a size at which further endocrinologic evaluation is typically advised to rule out hormonal activity or malignancy. All adrenal lesions (0.4% of the cohort in total) were flagged for clinical follow-up; even in the absence of overt symptoms, incidental adrenal masses in young patients necessitate evaluation given their potential clinical implications.

Several gastrointestinal tract-related IFs were detected as well. Colonic diverticulosis was seen in 8 patients (0.8%), an incidental finding given the young age of our cohort and one that generally required no acute intervention. Two patients (0.2%) had appendiceal mucoceles (mucus-filled appendiceal lesions) discovered incidentally on their CT. Both cases of appendiceal mucocele were considered clinically significant due to the risk of progression to malignancy (low-grade appendiceal mucinous neoplasm); consequently, both patients underwent surgical resection of the appendix [

17]. Additionally, 2 patients (0.2%) were noted to have internal hemorrhoids on their scans – an incidental finding of minimal acute significance, documented for completeness. Miscellaneous abdominal findings included inguinal hernias in 3 patients (0.3%). These hernias were incidental in that they were unrelated to the abdominal pain presentation. All three were clinically apparent on exam as well, and surgical correction was performed, although the hernias were not the cause of the ER visits.

Incidental findings in non-abdominal structures captured on the APCT were also recorded. Musculoskeletal IFs were seen in 18 patients (1.7%) [

9]. These included degenerative changes such as spinal spondylosis in 8 patients (0.8%), sacroiliitis in 4 (0.4%), scoliosis in 4 (0.4%), and a congenital variant (lumbarization of S1) in 2 patients (0.2%). While these bone and joint findings were unrelated to the acute abdominal issues, they could have long-term implications for a soldier’s physical fitness and were thus noted for outpatient follow-up as needed. Pulmonary incidental findings were observed in 8 patients (0.8%), specifically small pulmonary nodules seen at the lung bases on the APCT. It should be noted that the APCT includes only a portion of the lungs; thus, these pulmonary nodules were incidentally visualized at the lung bases and this does not represent a systematic chest CT screening of the entire lungs. All patients with incidental lung nodules were advised to undergo appropriate follow-up (such as dedicated chest imaging in a few months) to ensure these nodules are stable and likely benign findings.

3.1.2. Clinically Significant Incidental Findings

Out of the 218 patients with IFs, only a subset had findings that required clinical intervention or specialized follow-up.

Table 3 summarizes the clinically significant IFs and the recommended management for each. Renal lesions with malignant potential or significant pathology were the most prominent: the 3 Bosniak II-F renal cysts (0.3% of all patients) were scheduled for interval imaging follow-up due to their indeterminate nature, and the single cases of ADPKD and MCKD (0.1% each) were referred to nephrology/urology specialists for comprehensive management of these inherited renal conditions. The 7 cases of gallbladder adenomyomatosis (0.7%) were advised to undergo periodic ultrasound surveillance, given the need to distinguish them from more serious pathology over time and monitor for any changes. Incidental pancreatic lesions (the 1 IPMN and 1 pancreatic cyst, 0.1% each) were referred to gastroenterologists for further evaluation; in young patients, these lesions necessitate careful follow-up (and in the case of IPMN, consideration of surgical resection depending on size and features) [

18]. Adrenal incidentalomas – 2 patients with adenomas (0.2%) – were recommended for endocrine evaluation, especially the one >2 cm, to test for hormone secretion and assess if surgical removal might be warranted; the 2 cases of adrenal hyperplasia (0.2%) were also noted for endocrine follow-up to rule out subclinical adrenal dysfunction [

19]. Both patients with appendiceal mucocele (0.2%) proceeded to surgical treatment (appendectomy) soon after detection, given the risk of neoplastic transformation. The 3 incidental inguinal hernias (0.3%) were electively repaired by surgeons (these were clinically evident and easily addressed). Finally, all 8 patients with incidental pulmonary nodules (0.8%) were scheduled for follow-up chest imaging (e.g., a dedicated chest CT or serial radiographs per Fleischner Society guidelines), to ensure that these nodules are stable and likely benign findings.

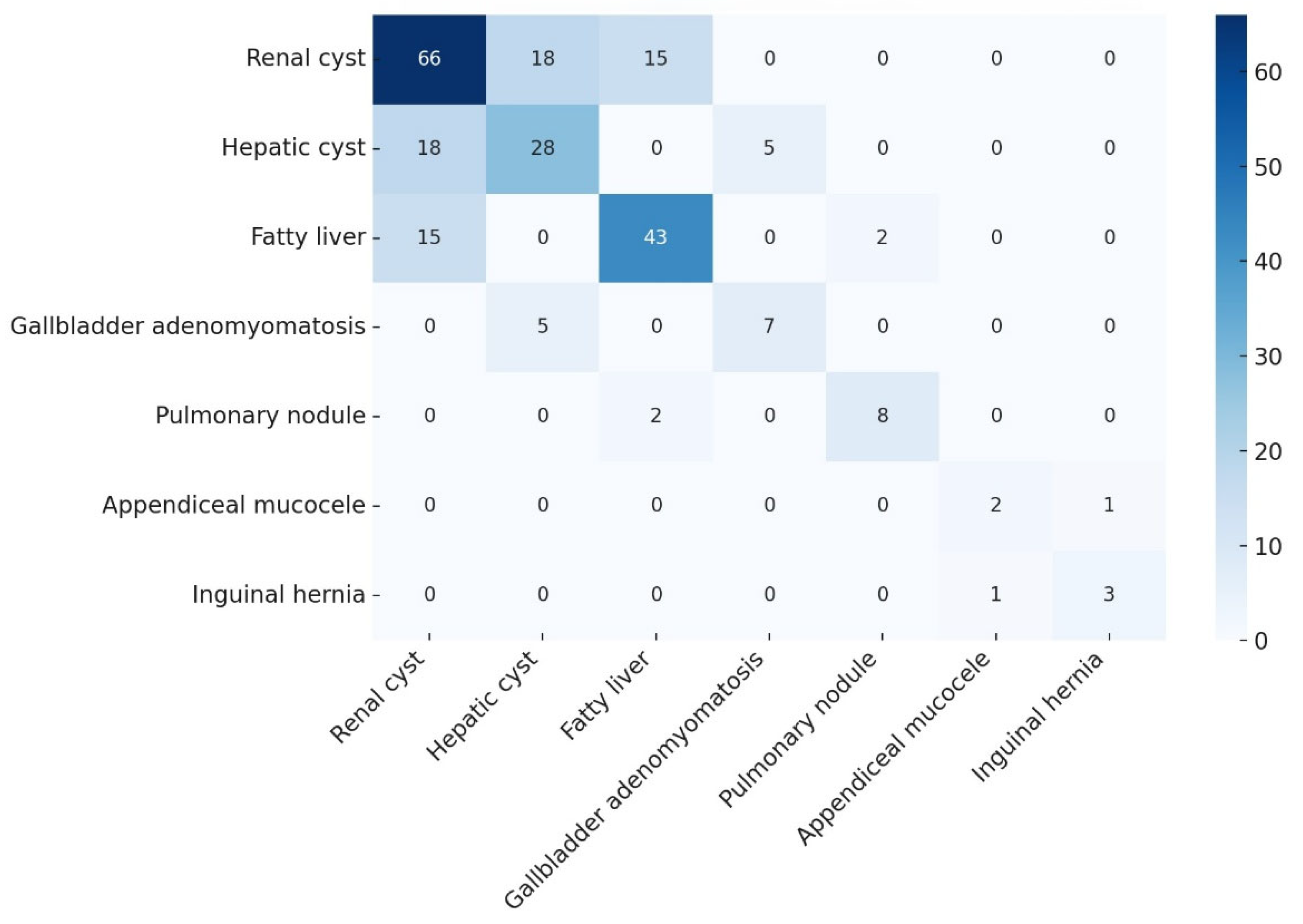

3.1.3. Co-Occurrence of Incidental Findings (Cluster Analysis)

We identified several significant associations between different types of IFs, as determined by our exploratory cluster analysis (

Table 4). Patients with certain IFs were more likely to have other specific IFs. Notably, among patients who had a renal cyst, 27.3% also had a hepatic cyst (p = 0.008), a rate significantly higher than in patients without renal cysts. Similarly, 22.7% of patients with renal cysts had concurrent fatty liver disease, which was a significantly elevated co-occurrence (p = 0.045). There was also a significant linkage between hepatic cysts and gallbladder adenomyomatosis: 17.9% of patients with an incidental hepatic cyst also had gallbladder adenomyomatosis (p = 0.032). Perhaps the most striking association was observed between appendiceal mucoceles and inguinal hernias—fully 50.0% of patients with an appendiceal mucocele (in fact, 1 out of the 2 such patients) also had an incidental inguinal hernia (p = 0.004). However, the association between appendiceal mucoceles and inguinal hernias, while statistically significant, is based on a very small number of cases (n=2) and should be interpreted with caution as it may be a chance finding. These patterns suggest that some IFs do not occur entirely at random; there may be shared risk factors or anatomical relationships contributing to their co-occurrence.

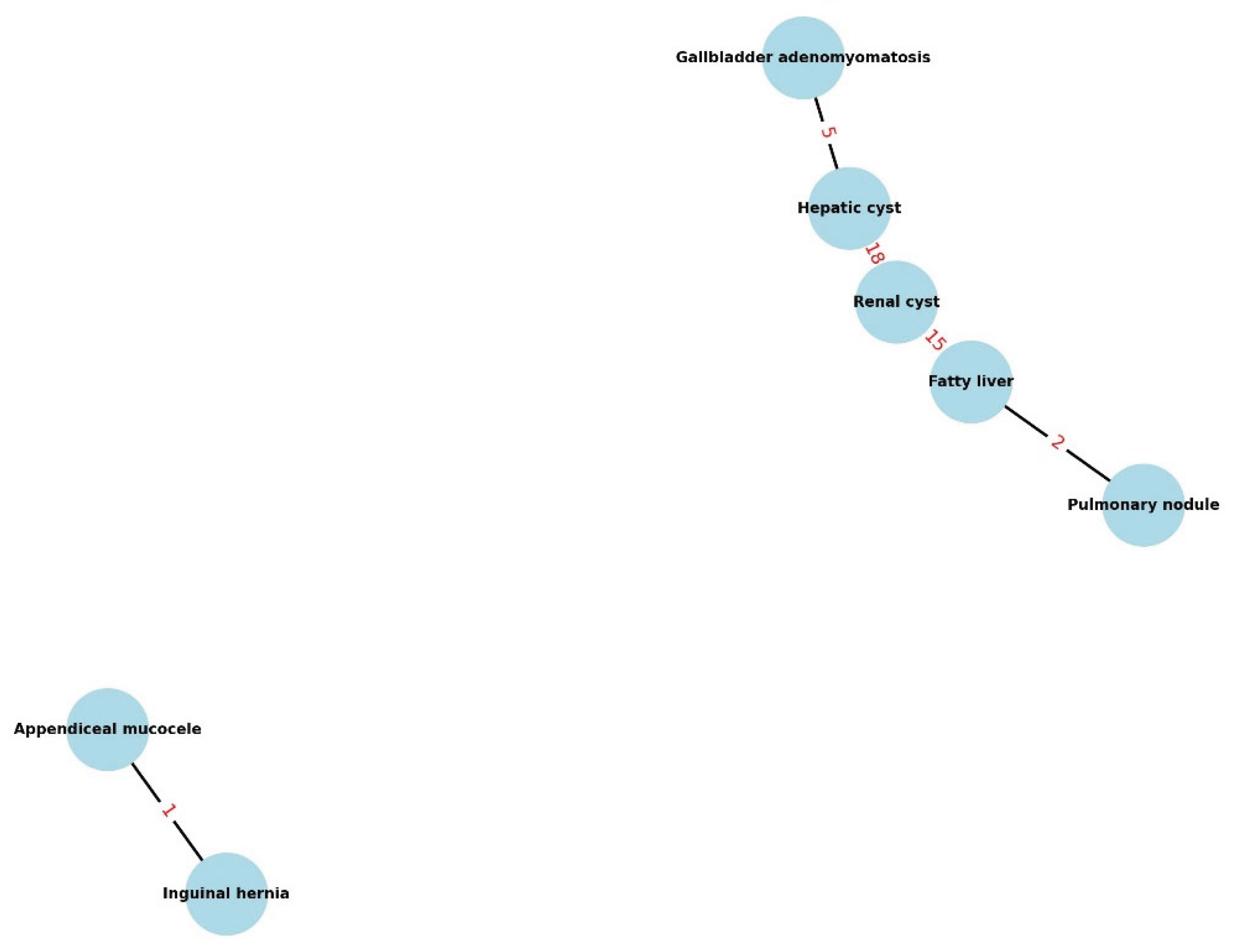

These relationships are visualized in

Figure 2, which presents a network graph of the significant IF co-occurrences. In the graph, each node represents a category of incidental finding, and connecting lines indicate pairs of IFs that significantly co-occurred. Thicker, bolder connection lines denote stronger associations (e.g., lower p-values or higher odds ratios). For example, the link between renal cysts and hepatic lesions (including hepatic cysts and fatty liver) is prominently displayed, as is the link between appendiceal mucocele and inguinal hernia. This visual aid complements the statistical results and highlights clusters of incidental findings that might share common underlying factors (genetic predispositions, lifestyle factors, or developmental anomalies).

Overall, our results emphasize that incidental findings in this young, ostensibly healthy population are not only common but also can be complex. Multiple IFs can occur in the same patient, and certain IFs tend to appear together. Recognizing these patterns can help clinicians not only in thoroughly reviewing scans (to be alert for associated findings) but also in developing targeted follow-up strategies (for instance, a soldier with a renal cyst might benefit from a liver ultrasound to check for hepatic cysts, given the association).

4. Discussion

In this retrospective case series of young adult soldiers in a military hospital ER, incidental findings were identified on APCT in 20.5% of patients who underwent scanning for acute abdominal pain. This prevalence is somewhat lower than the IF rates reported in many civilian emergency populations (often around 30–35%) [

4]

This is likely due to the unique demographics of our cohort – young, active-duty military personnel tend to be healthier and have fewer chronic conditions than older or general ED populations. This lower prevalence may also, in part, reflect the effect of rigorous pre-enlistment health screening, which screens out individuals with significant pre-existing conditions [

20].

4.1. Clinical Implications of Incidental Findings

Despite the lower overall prevalence, our study is significant because it demonstrates that even in a highly-screened, healthy population, APCT can uncover clinically significant pathologies that require follow-up. For example, our incidental discovery of rare conditions such as ADPKD, IPMN, and Bosniak II-F cysts in young individuals underscores the value of systematic and thorough CT interpretation. While these findings were uncommon, they have profound long-term implications for a soldier’s health and military readiness. This highlights a critical and under-addressed need within military healthcare systems: proactively managing these unexpected findings to prevent long-term morbidity.

The spectrum of IFs we observed was consistent with patterns noted in other studies, though with some differences in frequency. Hepatic and biliary IFs were the second most frequent category. We found fatty liver in 4.0% of all patients and hepatic cysts in 2.6%. While these percentages are lower than those reported in some civilian studies, they are notable given our cohort’s young age. The military lifestyle—though regimented—can involve high caloric intake and intermittent exercise patterns, possibly contributing to these findings [

14].

4.2. Co-Occurrence of Incidental Findings

Our cluster analysis was exploratory in nature and should be considered hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. The analysis provided insights into how certain IFs might relate to each other. For instance, the significant co-occurrence of renal and hepatic cysts suggests a possible shared predisposition—some individuals may have a tendency to develop cysts in multiple organs [

21]. This could be genetic or environmental. Previous studies have documented concurrent renal and hepatic cysts and even propose common risk factors or genetic patterns influencing cyst formation across organs. Similarly, the association between appendiceal mucocele and inguinal hernia, while based on very small numbers, is intriguing. Our finding of these two conditions together in one patient underscores the importance of thoroughly inspecting all aspects of a CT image—if one unusual finding is present, radiologists should be prompted to search for any other aberrant anatomy or pathology that might co-exist.

4.3. Military Healthcare Implications

From an operational perspective in military medicine, our study reinforces the critical need for structured management of incidental findings. Resource limitations in military hospitals (fewer specialists on-site, frequent relocation of service members, etc.) mean that communication and follow-up systems must be robust to ensure IFs are not lost to follow-up. Recent initiatives like the FIND (Follow-up of Incidental Imaging Findings) program have shown that systematic tracking and reminding can greatly improve compliance with recommended follow-ups for Ifs [

22]. Adopting similar structured reporting templates and automatic referral or notification systems in the military health system could ensure that when a young soldier has an incidental lesion (like a small lung nodule or an adrenal mass), appropriate steps are taken even if the soldier transfers to a different unit or facility [

23].

4.4. Limitations

Several inherent limitations of our retrospective case series warrant discussion. First, the retrospective design and convenience sampling introduce potential selection biases. We relied on existing records and imaging, which means some IFs or clinical data might have been missed or not recorded. The high exclusion rate (34%) may also affect the internal validity of the study and raises the possibility of selection bias, as excluded cases may have differed systematically from those analyzed. Second, our analysis lacked long-term follow-up, which is a notable limitation in a military context where service members may be lost to follow-up when they leave or are transferred. Finally, although we employed independent double-reading of scans to improve detection of IFs, we did not formally measure inter-observer reliability. This lack of a quantitative assessment of concordance between the two radiologists is a limitation, as it introduces potential subjectivity that could not be fully captured. This study's external validity is limited by the homogenous, male-only cohort, which may not be representative of the general population. Future prospective multi-center military studies with standardized IF reporting and long-term follow-up are warranted to address these limitations and to better characterize the natural history of these findings.

5. Conclusions

Incidental findings on APCT are common and clinically important even in a young, healthy military population. This study uncovers a significant and unaddressed health surveillance gap. The implementation of systematic, technology-driven protocols for reporting and tracking incidental findings is not merely a recommendation but a strategic necessity to ensure the long-term health, readiness, and combat effectiveness of the armed forces.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material is available at Military Medicine online.

Author Contributions

All authors were involved in the design of this research. K.L. and K.J. conducted data collection. All authors screened the data. Full-text screening was undertaken by C.L. and D.L. Data extraction was piloted between K.J. and D.L., and following piloting, K.L. extracted all data. C.L. analyzed the data and drafted the original manuscript. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a research grant (2020-08) from Jeju National University Hospital

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Institutional Review Board (IRB No. AFCH 2023-03-006) approved this study and waived the requirement for informed consent due to its retrospective nature.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to the privacy of study participants and the inclusion of sensitive military information. However, data may be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to approval by relevant military authorities.

Acknowledgments

We confirm that there are no acknowledgments to report for this scoping review. All contributions to this work were made solely by the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| APCT |

Abdominopelvic computed tomography |

| IF |

Incidental finding |

| ED |

Emergency department |

| ER |

Emergency room |

| IPMN |

Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm |

| ADPKD |

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease |

| MCKD |

Medullary cystic kidney disease |

| IQR |

Interquartile range |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| CT |

Computed tomography |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Thompson, R.J.; et al. Incidental Findings on CT Scans in the Emergency Department. Emerg. Med. Int. 2011, 2011, 624847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.S.; et al. Incidental Radiology Findings on Computed Tomography Studies in Emergency Department Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2022, 80, 243–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samim, M.; et al. Incidental findings on CT for suspected renal colic in emergency department patients: prevalence and types in 5,383 consecutive examinations. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2015, 12, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Devine, A.S.; et al. Frequency of incidental findings on computed tomography of trauma patients. West. J. Emerg. Med. 2010, 11, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Israel, G.M. and M.A. Bosniak, An update of the Bosniak renal cyst classification system. Urology 2005, 66, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orme, N.M.; et al. Incidental findings in imaging research: evaluating incidence, benefit, and burden. Arch. Intern. Med. 2010, 170, 1525–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.L.; et al. White Paper: Best Practices in the Communication and Management of Actionable Incidental Findings in Emergency Department Imaging. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, E., J. Park, and E. Jung, Unmet Healthcare Needs and Associated Factors Among Korean Enlisted Soldiers. Mil. Med. 2021, 186, e186–e193. [Google Scholar]

- Dursa, E.K.; et al. Demographic, Military, and Health Characteristics of VA Health Care Users and Nonusers Who Served in or During Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom, 2009-2011. Public. Health Rep. 2016, 131, 839–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, A.Y.; et al. Clinical and Psychological Characteristics of Young Men with Military Adaptation Issues Referred for a Psychiatric Evaluation in South Korea: Latent Profile Analysis of Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 and Temperament and Character Inventory. Psychiatry Investig. 2021, 18, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisinger, H.S.; et al. A population approach to mitigating the long-term health effects of combat deployments. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2012, 9, E54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacMahon, H.; et al. Guidelines for Management of Incidental Pulmonary Nodules Detected on CT Images: From the Fleischner Society 2017. Radiology 2017, 284, 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Connor, S.D.; et al. Incidental Finding of Renal Masses at Unenhanced CT: Prevalence and Analysis of Features for Guiding Management. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; et al. Impact of Korean Military Service on the Prevalence of Steatotic Liver Disease: A Longitudinal Study of Pre-enlistment and In-Service Health Check-Ups. Gut Liver 2024, 18, 888–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalasani, N.; et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2018, 67, 328–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golse, N.; et al. Gallbladder adenomyomatosis: Diagnosis and management. J. Visc. Surg. 2017, 154, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.; AlSubaie, R.S.; Almohammed Saleh, A.A. Mucocele of the Appendix: A Case Report and Review of Literature. Cureus 2023, 15, e40168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, M.; et al. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2012, 12, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassnacht, M.; et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology Clinical Practice Guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 175, G1–G34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safari, S.; et al. Prevalence and clinical significance of incidental findings in chest and abdominopelvic CT scans of trauma patients; A cross-sectional study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 82, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hélénon, O.; et al. Simple and complex renal cysts in adults: Classification system for renal cystic masses. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2018, 99, 189–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki-Metias, K.M.; et al. The FIND Program: Improving Follow-up of Incidental Imaging Findings. J. Digit. Imaging 2023, 36, 804–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bunck, A.C.; et al. Structured Reporting in Cross-Sectional Imaging of the Heart: Reporting Templates for CMR Imaging of Cardiomyopathies (Myocarditis, Dilated Cardiomyopathy, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Arrhythmogenic Right Ventricular Cardiomyopathy and Siderosis). Rofo 2020, 192, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).