1. Introduction

Appendicitis is a common clinical concern, particularly during adolescence when its incidence peaks. Retrospective analysis of USA data (1979–1984) revealed lifetime appendicitis risks of 8.6% for males and 6.7% for females, with the highest occurrence observed between the ages of 10 and 19 years [

1]. In this 1979-1984 analysis, prior to routine preoperative imaging, clinical accuracy of appendicitis diagnosis, as measured by normal appendix removal rate at surgery (the “negative appendicectomy rate” [NAR]), was calculated to be 91.2% for males, 78.6% for females [

1]. Pre-operative imaging aims to improve accuracy and minimize NAR. Traditionally, clinicians have turned to either ultrasound (US) or computed tomography (CT); however, each has limitations.

A meta-analysis of 17 studies with 2,841 participants found that US had a false negative rate of 55% and a false positive rate of 8% for detecting appendicitis [

2]. In one study, the appendix could only be visualized using US in 89/562 (16%) of cases. US accuracy for appendicitis was 86.5% for these 89 “appendix visualized” cases alone; however, reduced to only 13.7% when the other 473 “indeterminate” studies—where the appendix could not be visualized— in this series were also considered [

3]. Both publications recommended against using US routinely for appendicitis assessment.

CT provides high diagnostic accuracy but has significant iatrogenic risk. A Cochrane review of 71 studies, involving a total of 10,280 participants, reported 95% sensitivity and 94% specificity for CT in diagnosing appendicitis in individuals >14 years old [

4]. A 2010 publication showed beneficial NAR reduction from 23% to 1.7% when comparing data from the pre-routine CT era (1990–1994) to the period of 2003–2007 with >3,000 pre-operative CT scans/year at the same institution [

5]. BIER V (Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation) data supported a commonly cited average population risk of 1 cancer death per 2,000 CT studies [

6]. Citing this BIER V 1:2,000 risk assumption and reassessing the original published data from the abovementioned 2010 study, another author group predicted 1 CT-caused death for every 12 negative appendicectomies avoided in the 2010 study [

7].

A 20-year-old female undergoing non-contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis could face a cancer risk as high as 1 in 200, rather than 1 in 2,000 [

8]. If substituted into the above assumptions, this would predict nearly one CT-caused death for every negative appendicectomy avoided, with 1:1 ratio reached at CT risk of 1:167. The benefits of avoiding negative appendicectomy surgeries likely do not include lowered death risk, considering that a 10-year review of 16,315 laparoscopic emergency excisions of a normal appendix from United Kingdom national health records reported no deaths in patients <49 years old [

9].

In this study, we aimed to demonstrate that a locally designed 12-minute non-contrast MRI abdomen protocol (“MRI screening”) has been accurate for diagnosing or excluding appendicitis as the primary, and often only, imaging at the authors’ two emergency department (ED) sites. This has been available with extended hours every day since 2017 and has dramatically reduced both US and CT referrals for appendicitis assessment at each site.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

Ethical approval was obtained from the Western Sydney Local Health District Research & Education Network Scientific Advisory Committee (2311-07-QA), and the study was conducted in accordance with the principle outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. As this was a retrospective observational quality assurance study, requirement for informed consent was waived.

2.2. Facility Overview

Blacktown Mount Druitt Hospital is a tertiary care hospital in New South Wales, Australia, operating across two campuses: one at Blacktown and one at Mount Druitt, Sydney. Each provides 24-hour adult and pediatric emergency services. Within NSH Health, Blacktown is a “Major Hospital” transitioning to a “Principal Referral Hospital,” whereas Mount Druitt is a “District Hospital.” Clinical services are networked across the two sites with 530 beds combined. District records for 2023 showed that Blacktown Hospital had 65,000 presentations to ED, Mount Druitt Hospital 40,000 presentations: 105,000 across both sites inclusive of all demographic groups. For both sites Radiology Information System data for 2023 showed 90,275 referrals from ED to medical imaging, 15,528 for patients <25 years old. Of these 15,528 referrals, 1,963 were for MRI, and 1,309 were for CT. The 1,963 MRI referrals included 1,149 MRI screening abdomen referrals, 960 for possible appendicitis assessment. The 1,309 CT referrals included 115 contrast CT abdomen pelvis for any reason, trauma included.

2.3. MRI Screening Abdomen Service Development

Since May 2017 the presented 12-minute MRI screening protocol has been available as an open-access imaging option (no booking or discussion needed) for any ED or acute surgical patient for any clinical presentation. ED staff complete an electronic request and safety sheet, notify MRI staff, and send the patient for MRI. There was no directive to use this service; it simply became a new imaging option. Any patient could be referred. Children <5 years old and occasional patients >80 years old were equally accepted without booking restriction for any clinical indication.

Adherence to uniform imaging protocol and report layout by a single reporting radiologist improved clinician familiarity. An activity log of all reports was maintained by A.O.J. on a single-user, encrypted, password-protected Microsoft Access database. This included time and date of each report, whether appendicitis was being considered, summary of report conclusion and a field for later addition of a brief clinical outcome note. It was updated daily, including checks that no recent report had been missed. This activity log enabled follow-up of clinical outcomes, case comparison with similar cases and development of a comprehensive appreciation of expected imaging appearances for all commonly encountered pathologies, including appendicitis. It has played a critical role in service development at our sites, independent of any planned review.

2.4. Data Collection

With date and data filters a list of consecutive MRI screening reports fitting selection criteria could be produced from the activity log described above. These criteria were: report completed January 1, 2019 to December 31, 2023 inclusive; report finalized by A.O.J.; acute care ED based referral; appendicitis a clinical consideration. The list was exported to a Microsoft Excel file for addition of required data fields for this review.

From an initial list of 4,263 MRI screening reports within the defined timeframe 3,479 were identified when filtered to all requirements. One was excluded after review, described below, leaving 3,478 reports eligible for diagnostic accuracy analysis with no risk of missing data.

2.5. Use of Other Clinical Information

The reporting author had access to patient electronic medical records. Usual practice would be to quickly review ED presenting symptoms and available hematology results prior to reporting. Prior imaging was almost always not available or disregarded.

Description of presenting symptoms sometimes assisted faster identification of appendix location or refined the range of considered alternative diagnoses. High inflammatory markers could prompt longer image review time. Neither had any further influence on report conclusion.

Prior ultrasound imaging was considered unreliable, always ignored. CT and MRI, regarded by referring teams to have equivalent accuracy, were almost never done together. For rare cases where an indeterminate CT had led to a subsequent MRI the author would review MRI with little reference to the CT, as per the reason for that referral. Conversely, if CT were requested after MRI due to continued clinical uncertainty, the MRI had already been reported, hence its status in this review would not be affected.

Appendix report conclusion was always based on appendix MRI appearance alone. Achieving best accuracy depended on this.

2.6. Equipment

Equipment at our campuses included Siemens 3T MRI units; Siemens Magnetom Trio Tim (from 2018) that was upgraded to Magnetom Prismafit (2022); Siemens Skyra 3T (from 2018); and Siemens Vida 3T (from 2020).

2.7. Patient Preparation

Patients were instructed to drink two to three cups of water 20-45 minutes prior to imaging (longer is better). The MRI safety form was reviewed with the patient and the procedure explained.

2.8. Imaging Protocol (Four Sequences)

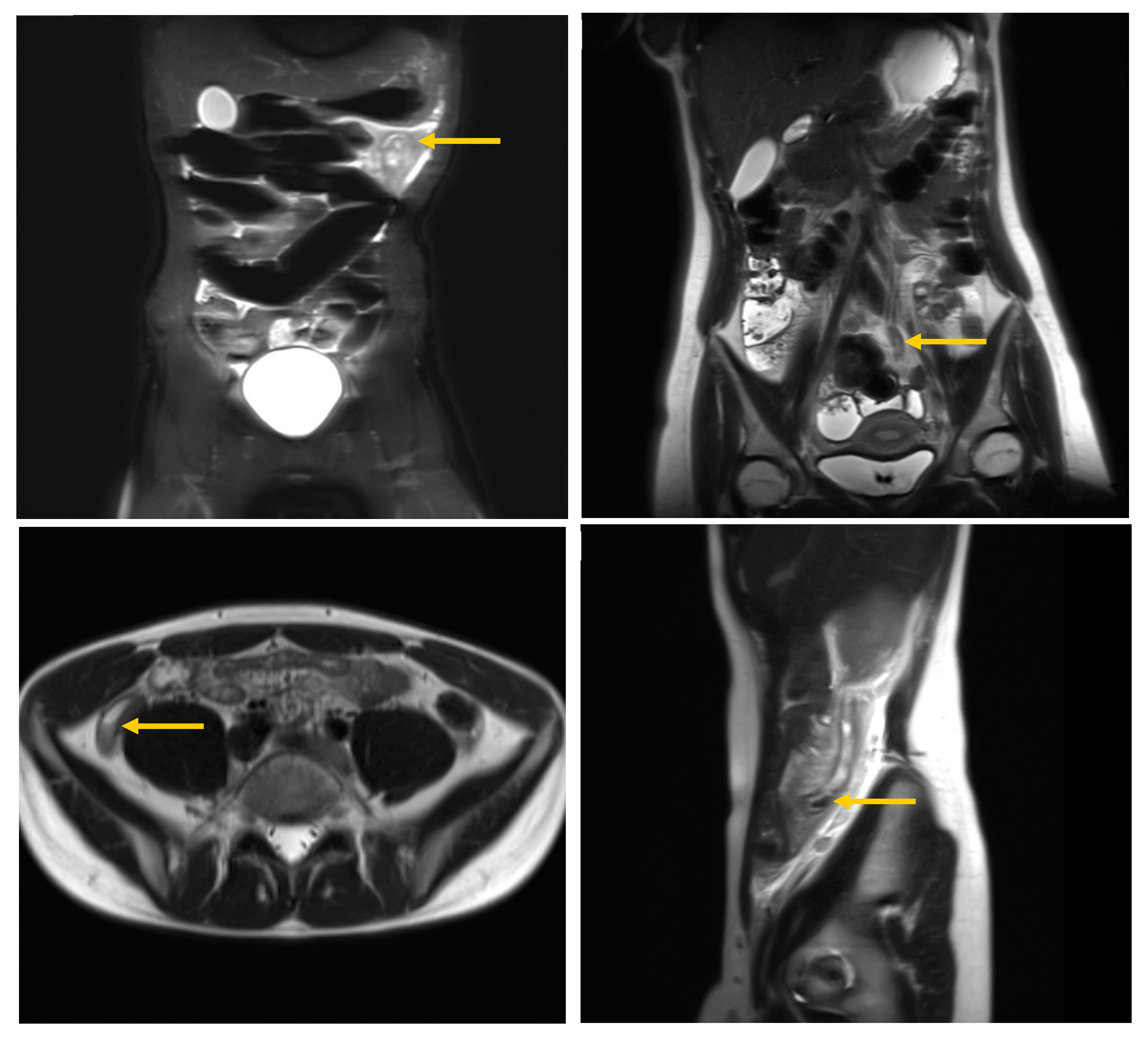

Coronal fast-acquisition (breath-hold) T2 image sets were obtained with and without fat-suppression using TR 1500, TE 100, 3 mm thickness, no slice gap, coverage from the pelvis to top of kidneys, angled along psoas muscles for best kidney coverage. Sagittal breath-hold T2 images were obtained across the right side only with TR 1500, TE 100, 4 mm thickness, no slice gap, extending from the pelvis to the top of the kidney. Axial breath-hold T2 images were obtained through the lower abdomen and pelvis with TR 1500, TE 95, 5 mm thickness and no slice gap (

Figure 1). Total imaging time for all four sequences was 12-minutes. Fat suppressed images can be identified by noting a dark subcutaneous fat appearance.

2.9. Imaging Protocol (Patient Instructions)

Optimal imaging was achieved with repeated small inspiratory breath-holds. For young children or patients with reduced MRI tolerance, continued gentle breathing was allowed. This would cause mild image blurring but remained adequate for appendix assessment (see

Figure 1).

2.10. Imaging Protocol Variations

Axial images were sometimes extended to the upper abdomen if symptoms extended to this level. Diffusion weighted imaging was performed for 90 early cases but was unhelpful and therefore discontinued.

2.11. Recommended Image Interpretation Technique

The authors’ technique for image review was to start with the non-fat-suppression sequences. Each image set was scrolled back and forth. On coronal images, the appendix was often identified crossing the iliac vessels. If not, the inferior cecum, toward the right kidney and near the right ovary, were checked. Caution was needed not to be misled by a Fallopian tube, round ligament, or by lumbosacral plexus nerves. On axial images, a fleeting structure could often be identified between the cecum and psoas muscle. On sagittal images the anterior psoas muscle margin, posterior margin of the ascending colon, and region anterior to the lumbosacral junction were checked. Fat-suppression images generally only assisted characterizing an inflamed appendix once found. If only one sequence were possible for a patient having difficulty, coronal T2 imaging without fat saturation was the best choice.

A request form suggestion of high or low suspicion of appendicitis was unhelpful. Specific details could be of assistance. Pain on urination could mean pyelonephritis, ureteric calculus, or an inflamed appendix against the bladder. Back pain could be due to spinal pathology or an inflamed appendix against the lower lumbar spine. Right iliac fossa pain was more likely due to an ovarian cyst if the appendix was shown on MRI to be high near the liver. Co-existing pathology was not uncommon. The appendix always needed to be directly assessed.

Diameter of appendix was the starting point of assessment but varied with luminal content and from base to tip. As with ultrasound and CT, where to measure appendix diameter depended on appendix visibility, and hence, was partially subjective. A measurement taken from the widest portion well clear of the base was generally best. A diameter of 10 mm near the base and 5 mm distally was usually normal, whereas a diameter of 5 mm near the base and 10 mm distally was usually appendicitis (see results).

Fluid adjacent to the appendix was common, thus rarely helpful for appendicitis assessment.

Appendix luminal fluid suggested a normal appendix if continuous with fluid in the cecum but suggested appendicitis if confined to only a distended distal appendix portion. Mild smooth fluid distension of the appendix lumen to the appendix base, occasionally seen due to cecum fecal loading, was regarded with caution, leading to further careful assessment for appendix wall thickening or mucosal contour irregularity.

Fecaliths within the appendix lumen were a very strong predicter of appendicitis (see results), particularly if distal appendix luminal fluid sharply defined the distal fecalith edge.

Appendix wall thickening and edema (brighter signal) strongly indicated appendicitis however did not always mean surgery was required. If continuous with similar changes along the ascending colon appendicitis secondary to adjacent infective colitis, potentially responsive to a trial of medical therapy, was occasionally suggested.

Peri-appendiceal fat edema strongly implied appendicitis only if surrounding it. Asymmetric adjacent oedema could sometimes be due to nearby cecal diverticulitis or epiploic appendagitis.

To achieve high report accuracy all factors above needed to be considered. Appendix diameter was only the starting point.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

2.12.1. MRI Report Classification

Each MRI report was categorized as either “any possibility positive” (positive; 581/3478 reports) or “no evidence of appendicitis” (negative; 2,897/3478 reports). Suggested alternative diagnoses were disregarded. There were no “indeterminate” reports. By standardized approach any case with uncertainty had the conclusion “Appendicitis could still be considered”, regarded as a positive report by clinicians, and a positive report for this review.

2.12.2. Clinical Outcome Classification

Clinical outcomes were assessed by reviewing medical records at least 2 weeks after patient discharge. A patient presentation was regarded to have been clinically negative for appendicitis (2,921 presentations) in the presence of clinical improvement without surgery or intravenous antibiotics and no clinical relapse (2,811/2,921), laparoscopy performed for other reasons, appendix left in place (58/2,921), or appendicectomy performed but no appendicitis on pathology report (52/2,921).

A patient presentation was regarded to have been clinically positive for appendicitis (557 presentations) if appendicectomy had been performed and appendicitis confirmed on the pathology report (537/557), if an abscess had been drained at the appendix site (6/557), if operative report confirmation was available without a pathology report (4/557), if there had been strong clinical agreement and successful medical treatment with intravenous antibiotics (6/557), or if there had been florid positive MRI imaging changes with clinical agreement but went elsewhere for surgery (4/557).

2.12.3. Statistical Classification

A true positive report is where appendicitis was suggested, and the clinical outcome was appendicitis. A false positive report is where appendicitis was suggested, and the clinical outcome did not include appendicitis. A true negative report is where a report directly stated, “there is no evidence of appendicitis” (or similar), and clinical outcome did not include appendicitis. A false negative report is where a report directly stated, “there is no evidence of appendicitis” (or similar), and clinical outcome was appendicitis. One patient, who returned 3 days after discharge with ongoing symptoms had undergone two MRI studies, and hence had two report entries: (i) false negative; and (ii) true positive. All other entries were for unrelated presentations.

Each image series was assessed by the same radiologist (A.O.J.) using consistent report phrasing. Each report concluded with a clear statement of either “possibility of appendicitis” (level of certainty specified) or “no evidence of appendicitis” (or similar). For a few difficult or uncertain cases, the phrase “appendicitis could still be considered” was used, recorded as a positive report in this series. There were no “indeterminate” reports.

One presentation within the initial activity log list of 3479 reports could not be appropriately classified. A 26-year-old female with right flank pain for 3 days had had a dilated fluid-signal appendix on MRI, reported as possible appendicitis. Pathology described a low-grade appendix mucinous neoplasm with clear margins. The “false positive” criteria were not met, as appendicectomy was curative. However, the “true positive” criteria were also not met, as there was no acute inflammation. This presentation was excluded from this series, leaving 3478 presentations for accuracy performance assessment.

2.12.4. Statistical Performance Measures

Rounded down to prior centile integer (disadvantageous).

Best value 100%.

Rounded down to the prior hundredth value (disadvantageous).

Best value = 1.

Rounded up to the next hundredth value (disadvantageous).

Best value = 0.

Rounded down to the prior centile integer (disadvantageous).

Best value = 100%.

Rounded down to the prior hundredth value (disadvantageous).

Best value = 1.

Rounded down to the prior integer value (disadvantageous).

False positive (FP) 0 causes division by zero error (“/0!”).

Positive likelihood ratio >10 regarded suitable for a screening test.

Rounded down to the prior centile integer (disadvantageous).

Best value = 100%.

Rounded down to the prior centile integer (disadvantageous).

Prevalence 0 % would bias true negative rate to 100%.

Prevalence 100% would bias true positive rate to 100%.

Prevalence 50% would not favor either measure.

Rounded up to the next centile integer (disadvantageous).

Prevalence threshold < prevalence reduces false positives.

Rounded down to the prior centile integer (disadvantageous).

Best value = 100%.

Rounded down to the prior centile integer (disadvantageous).

Best value = 100%.

3. Results

3.1. Statistical Performance Outcomes

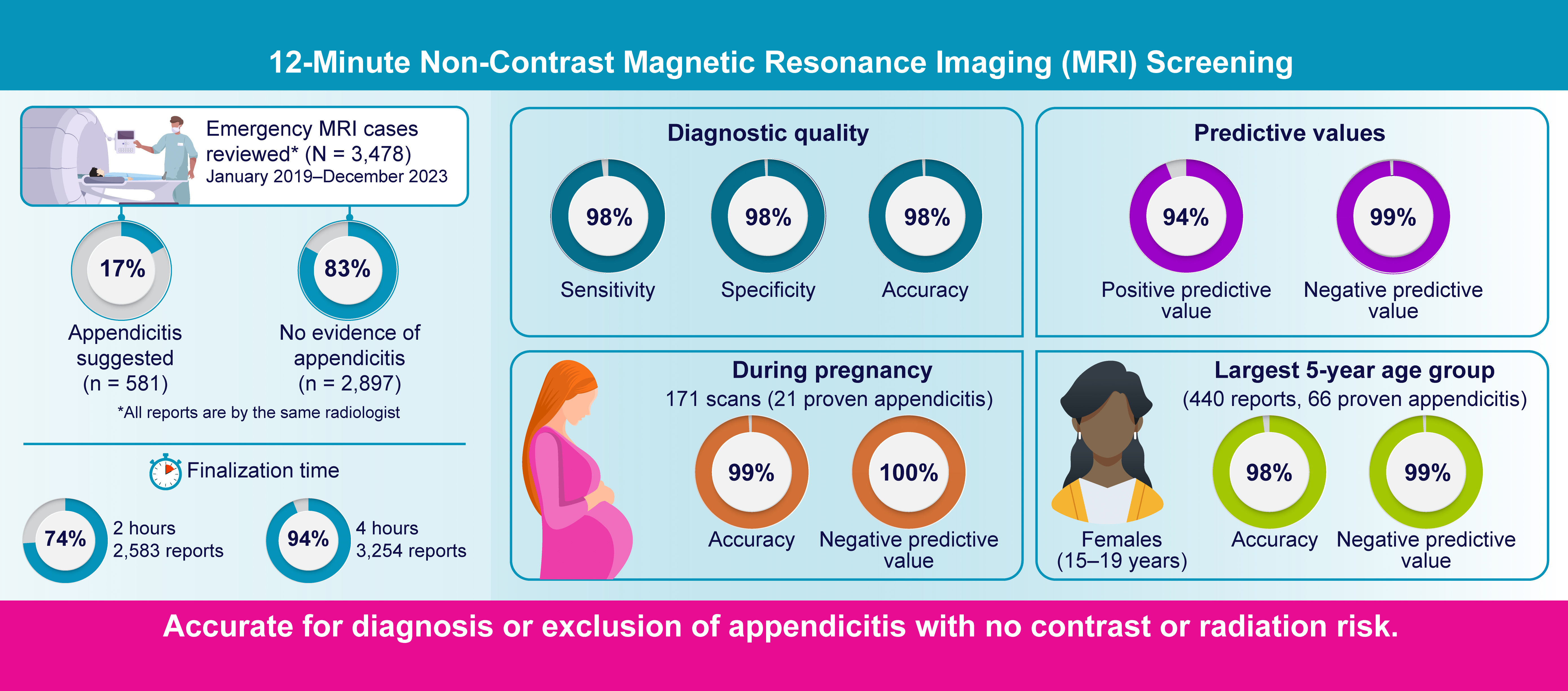

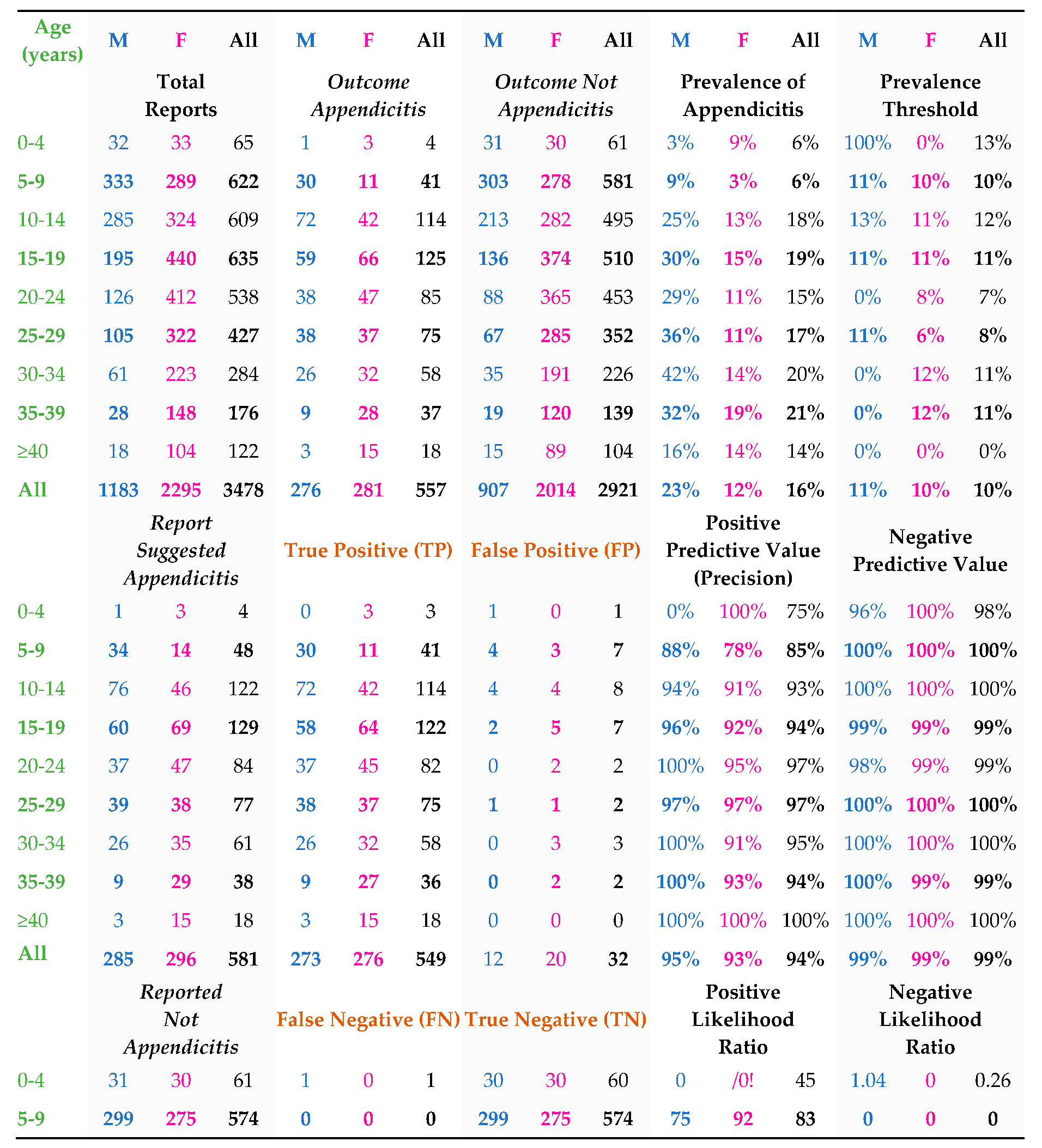

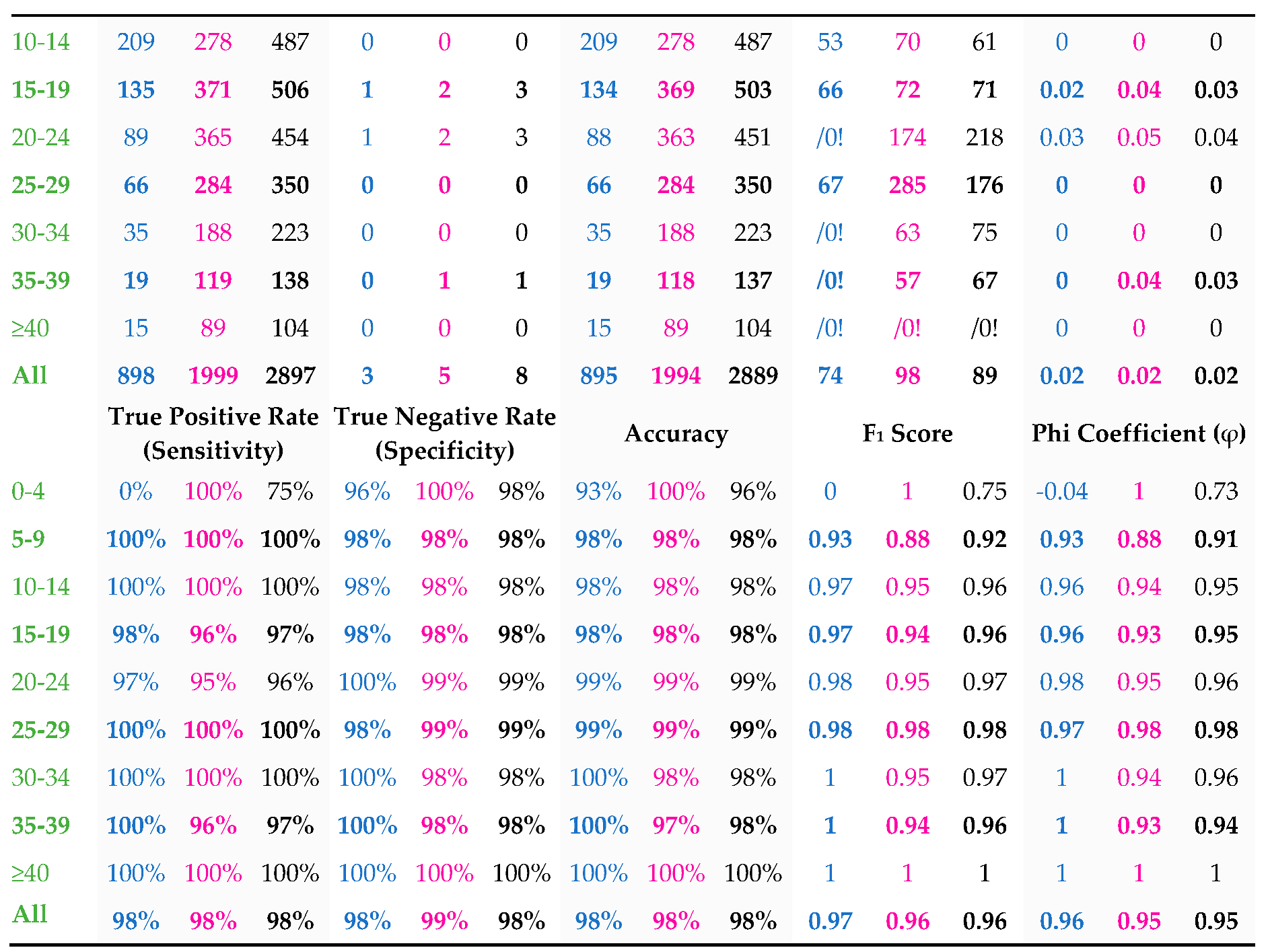

Of all reports, 2,889/3,478 were true negative, 549/3,478 were true positive, 8/3,478 were false negative, and 32/3,478 were false positive for appendicitis. With disadvantageous rounding to prior centile, these reports had 98% sensitivity, 98% specificity, 98% accuracy, 94% positive predictive value, and 99% negative predictive value for appendicitis (

Table 1).

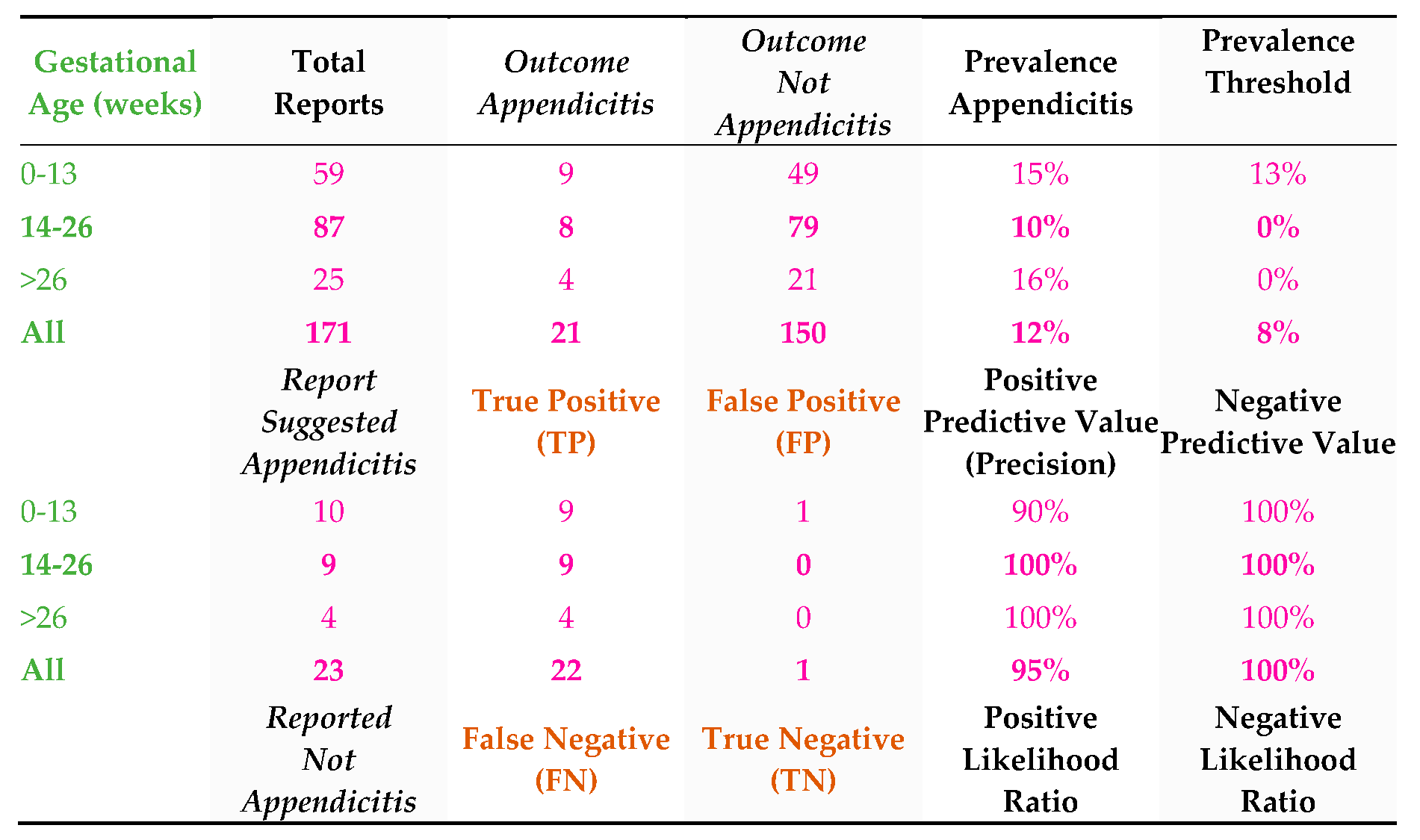

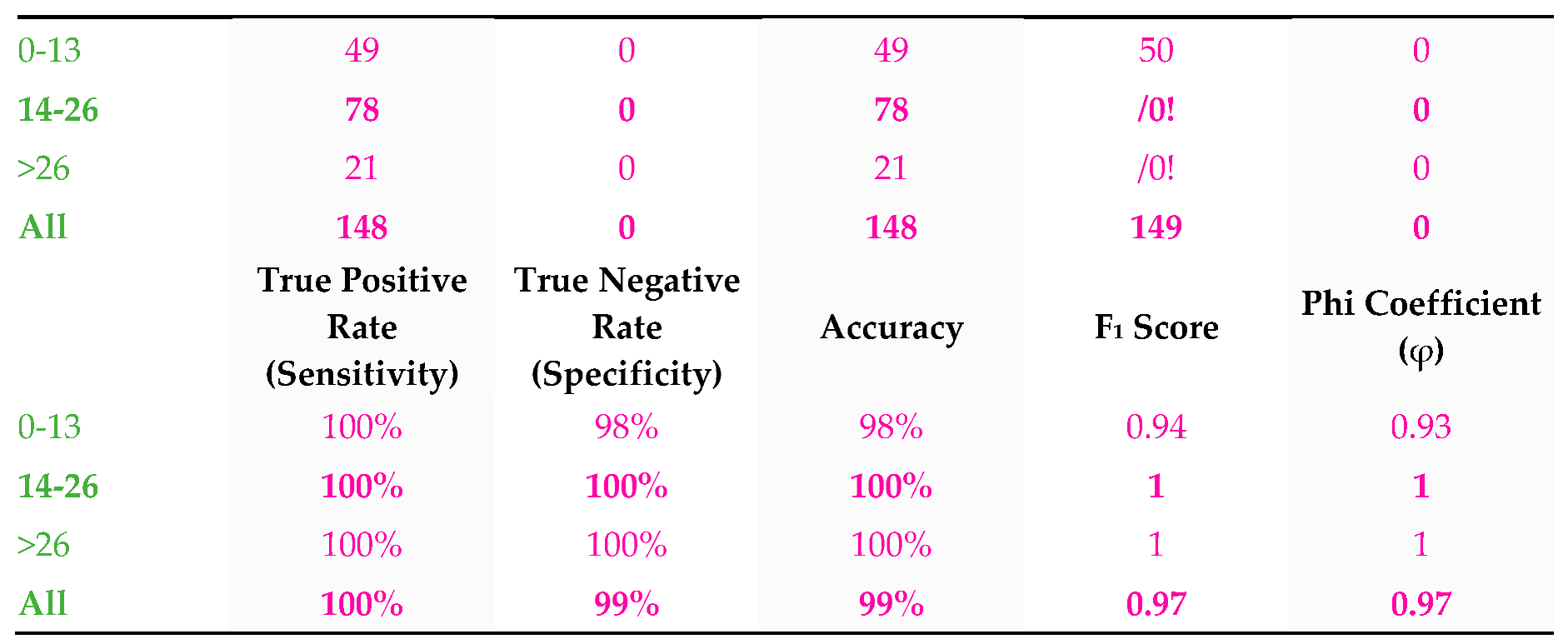

Within the female cohort 171/2,295 (7%) were referred for possible appendicitis assessment during pregnancy. These reports had 100% sensitivity, 99% specificity for detecting appendicitis (

Table 2).

3.2. Service Hours

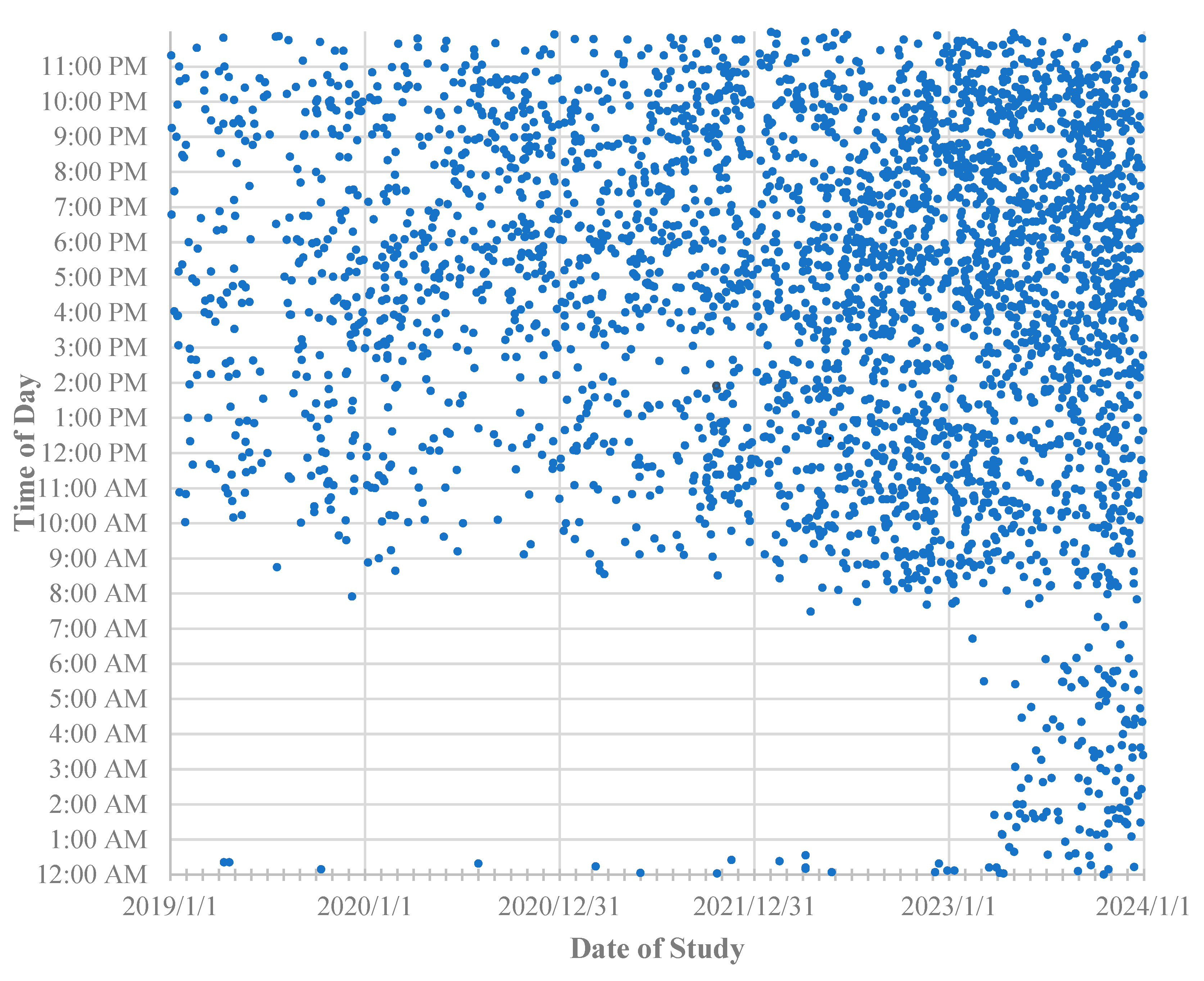

Between January 2019 and February 2023, MRI service hours were from 07:30 AM to midnight every day, with occasional cases after midnight due to staff staying back. Since March 2023, the service hours were extended to 24-hour coverage every day (

Figure 2). Of all scans, 840/3,478 (24%) were performed on Saturdays or Sundays.

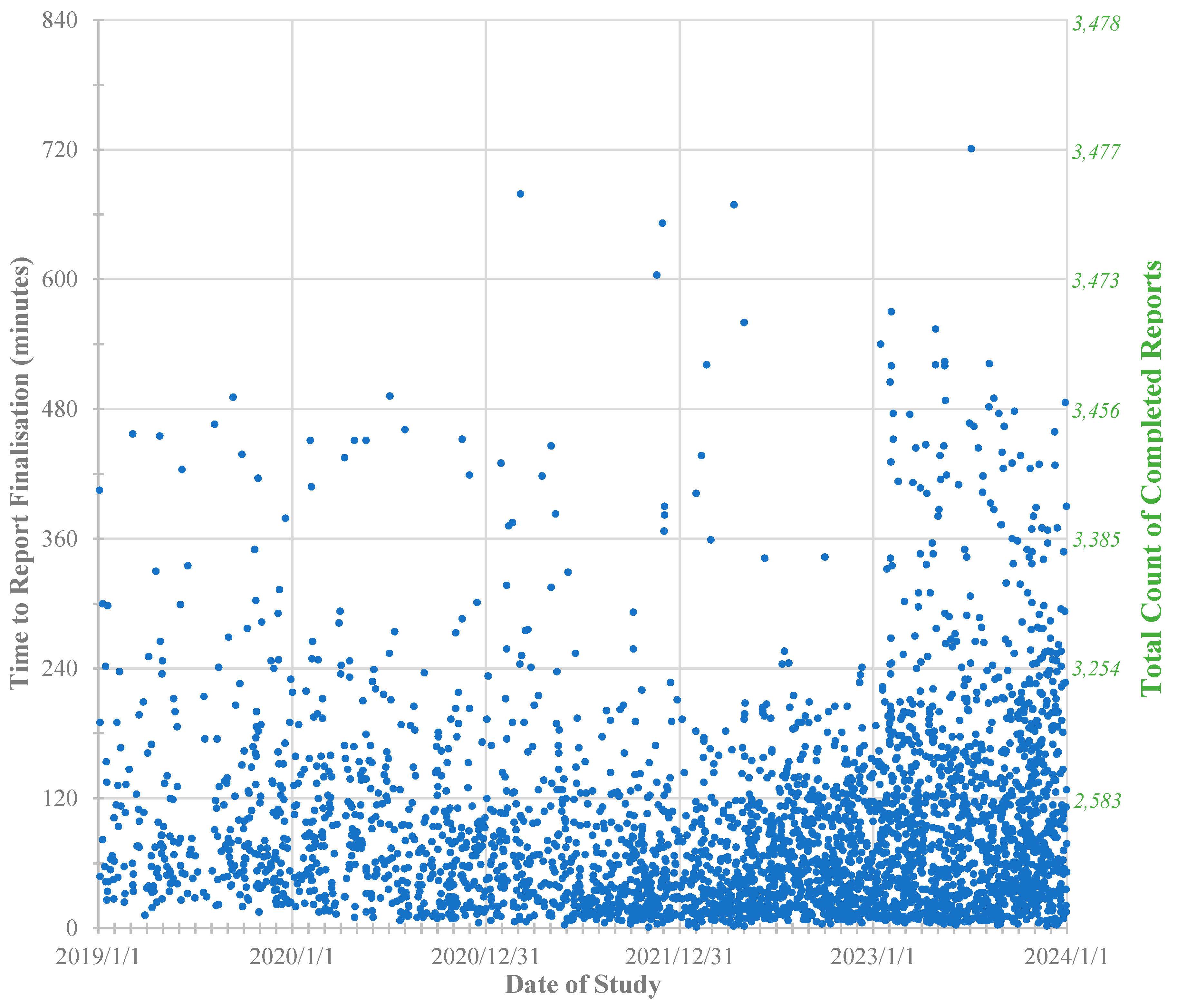

3.3. Urgent Report Availability

MRI screening was typically the only imaging performed for patients presenting to ED with possible appendicitis; thus, reports needed to be finalized within an acceptable timeframe. For this series 2,583/3,478 reports (74%) were finalized within 2 hours of MRI completion, 3254/3,478 (94%) within 4 hours (

Figure 3). Due to only single radiologist availability, when overnight service commenced from March 2023 clinically stable patients scanned overnight would have their reports delayed until the next morning, typically before 8:00 AM, unless an immediate report was requested. This was acceptable for our ED services.

3.4. Increasing Demand for Abdominal MRI Screening Assessment

Figure 2 demonstrates progressively increasing uptake of MRI screening as an imaging option, including increasing uptake of overnight imaging requests with the commencement of 24-hour availability from March 2023.

Figure 3 shows that despite more numerous report delays >4 hours for overnight studies this did not impede continued increasing referral rates at the authors’ sites.

3.5. NAR of the Study

Of the 588 patients with anatomical pathology in this series, 52/588 were negative for appendicitis, and 536/588 were diagnosed with acute appendicitis. The NAR for this series was thus 8.8% (52/588).

3.6. Appendix Diameter

In this series, a reported appendix diameter ≤4 mm had 100% negative predictive value for appendicitis, a diameter ≥11 mm had 100% positive predictive value. A 7 mm measurement was less helpful, having appendicitis outcome in 82/179 reports (46%) and normal outcome in 97/179 reports (54%) (

Table 3). For 13/3,478 (<1%) presentations, the appendix could not be measured due to appendix replacement by abscess, other pathology such as intussusception, or simple inability to visualize.

3.7. Fecaliths

A fecalith was reported in 154/3478 (4%) of MRI reports. Of these, 152/154 (99%) had true positive reports. In one false positive report a fecalith had been reported as though within an appendix, in retrospect likely within an adjacent inflamed cecal diverticulum. In one true negative report a small non-obstructing fecalith was reported as an incidental finding within an otherwise normal appendix. Two of eight false negative reports in this series also, in retrospect, had a fecalith within a dilated appendix. In one case the dilated appendix and fecalith were, in retrospect, clearly visible in a different location to that originally described (perception error false negative report). In the other case the appendix and fecalith had each been seen but had been mistaken to be small bowel containing a gas bubble (reader interpretive error false negative report).

3.8. Incidental Neuroendocrine Tumors with Co-existent Appendicitis

Pathology identified four incidental fully resected appendix neuroendocrine tumors, measuring 12 mm, 7 mm, 2 mm, and 1 mm, all with co-existing appendicitis. None of these tumors were identified prospectively on MRI amongst the background inflammatory change.

3.9. Retrospective Review of False Negative Errors

Of eight false negative reports 3/8 were reader perception errors, where, in retrospect, an inflamed appendix could be readily seen in another location to that reported, 1/8 was the interpretative error described above, and 4/8 remained difficult to appreciate as appendicitis, even in retrospect with appendicitis diagnosis known. All report errors have been included in this review, regardless of cause.

3.10. Female to Male Comparison

Females were more frequently referred for MRI in this series (2,295/3,478, [66%]) than males (1,183/3,478, [34%]) due to the broader range of female-specific alternative diagnoses that could clinically mimic appendicitis. This resulted in lower appendicitis prevalence in female referral subgroups compared to males. The highest female subgroup prevalence of appendicitis by 5-year age group was 28/148 (19%) for ages 35-39 years, then 66/440 (15%) for 15-19 years. This compared to male subgroup prevalence of appendicitis 72/285 (25%) in age range of 9-14 years and >25% for all older 5-year age groups up to 40 years (

Table 1).

3.11. Imaging Young Children Without Sedation

Almost all young children completed this MRI protocol without sedation. Neither intravenous sedation nor general anesthesia was offered. Of the 65 children <4 years old, 3 had supervised oral chloral hydrate sedation, 62 successfully completed the procedure without it. Among 78 children 5 years old, 3 had supervised oral chloral hydrate sedation, 75 did not. Children >5 years old were routinely imaged without sedation. If timed to a normal sleep pattern babies could be imaged after feed and wrapping during a normal sleep. For young children some examinations could be shortened by omitting one or two sequences without losing diagnostic value. For many allowing continued quiet breathing during imaging, rather than use of breath-holds, would significantly improve tolerance with minimal image blurring. All MRI studies, complete or not, were included in this series, provided at least one sequence could be obtained. Coronal T2 imaging was prioritized if tolerance appeared to be reduced.

4. Discussion

MRI screening for appendicitis had 98% accuracy for 3,478 reports. There were no known adverse effects from MRI for any patient. No intravenous contrast or line disposables were cost savings compared to CT. Examination time was 12 minutes compared to 20 minutes for US. Time-to-report and reporting cost were little different between modalities. Prevalence threshold, F1 score, and Phi coefficient are included in the provided analysis. These are briefly discussed.

Prevalence threshold calculates the appendicitis prevalence below which positive predictive value for MRI would be expected to sharply decline [

10]. Patient 5-9 years old were unfavorable on this measure – 6% true appendicitis prevalence, 10% calculated prevalence threshold: 85% positive predictive value. Older age groups had favorable threshold values compared to appendicitis prevalence, each with over 90% positive predictive value (

Table 1). Prevalence threshold does not, however, relate directly to the primary purpose of MRI screening for appendicitis, which is to exclude, rather than confirm, appendicitis. MRI screening had 100% negative predictive value for the 5-9 years age group, fully satisfying this clinical referral goal. Furthermore, for all 3,478 reports the threshold value of 10% for all reports combined was favorable compared to overall 16% appendicitis prevalence, such that for the study cohort in total 94% positive predictive value also is favorable as a screening test metric.

F

1 score and Phi coefficient are metrics intended to compare different studies with different disease prevalence rates. An important difference is that F

1 score does not include true negative results, whereas Phi coefficient includes all outcomes and could thus be considered the more wholistic metric [

11]. To illustrate this, we present 3,478 reports with F

1 score of 0.96 for appendicitis identification (“true positive” = correct appendicitis report). The same reports would have F

1 score of 0.99 for normal appendix identification (“true positive” = correct normal appendix report). Phi coefficient is unchanged at 0.95 regardless of true positive definition. Both are provided for reference; however, Phi coefficient is preferred by the authors over F

1 score as the better performance metric.

To achieve referrer confidence in MRI screening consistent imaging protocol, consistent report presentation, prompt reporting, open communication, reliable critical results notification procedures and providing best possible outcomes were essential. One study showed US sensitivities for appendicitis in the first, second, and third trimesters of pregnancy of 69%, 63%, and 51% respectively, with corresponding specificities 85%, 85%, and 65% [

12]. MRI screening for 171 pregnant patients had 100%, 100%, 100% sensitivity, and 98%, 98% and 100% specificity for the first, second and third trimesters of pregnancy, in addition to providing 100% negative predictive value all 1,231 children in both the 5-9 years and 9-14 years old subgroups combined.

A 2020 publication suggested that routine pre-operative CT could reduce NAR from 22% to 7%, with 89% reduction in healthcare costs and better allocation of health resources elsewhere [

13]. This claim disregards potential for radiation-induced harm delayed costs and incorrectly presents NAR as a CT diagnostic accuracy metric for exclusion of appendicitis, rather than sensitivity or negative predictive value.

A South Korean review of 825,820 preoperative appendix CT assessment studies (52.9% male; median age, 28 years) showed a 1.26 times higher risk of developing delayed hematologic malignant neoplasms (mostly myeloid leukemia), including 2.14 times higher risk for those aged 0–15 years [

14]. A European study showed an increased risk of hematologic malignancy within 12 years after any CT for patients <22 years old (1–2 persons per 10,000) [

15]. An Australian study of 10.9 million people aged 0–19 years found a 24% higher cancer risk following just one CT [

16]. An American study calculated the mean CT-associated cancer risk for a single non-contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis to be 1 in 500 (for females) or 1 in 660 (for males) at age 20 years [

8]. CT intravenous contrast has additional risks and costs [

17]. High likelihood for delayed healthcare costs would be difficult to quantify in cost but should not be disregarded.

NAR is not a diagnostic accuracy study metric. It is the proportion of patients who had a normal appendix removed at surgery. Local policy recommendations, individual clinician experience, patient demographic considerations, clinician confidence in imaging reports, and patient preference all can influence this. Imaging sensitivity is an appropriate metric without these confounding factors. On meta-analysis review CT had 95% sensitivity for appendicitis in patients >14 years age [

4]. MRI screening in this review had 98% sensitivity, including paediatric and pregnant patients. These sensitivity results could be considered equivalent. NAR should not be used to make comparison across sites, between modalities and for different demographic groups. It includes too many confounding variables. Our data showed 8.8% NAR for MRI screening. This, however, was shared equally across all patient groups typically excluded from CT.

In the 3,478 cases assessed confident alternative diagnoses provided included cecal diverticulitis, epiploic appendagitis, enterocolitis, mesenteric adenitis, dermoid cyst, hemorrhagic ovarian cyst, peptic ulceration, severe corpus luteum hemorrhage, tubal or ovarian torsion, pyosalpinx, ectopic pregnancy, pyelonephritis, ureteric calculus, cholecystitis, bile duct calculus, pancreatitis, and intussusception. Neither CT nor US alone have this diagnostic range.

Limitations

A study design limitation is that assessment for all MRI reports was conducted by a single radiologist (A.O.J.). Other studies would be needed to confirm similar results with other reporters. To the best of our knowledge there is no comparable single-site large series review.

A 2021 Cochrane review of MRI in pregnant women, children, and adults showed 95% summary sensitivity and 96% summary specificity for appendicitis diagnosis. This included 1980/7462 participants with appendicitis from 58 studies but highlighted frequent methodology limitations of these studies. Our report adds a large series to the literature however did not avoid all methodological concerns raised. Of these the most significant limitation of our review was reliance on case note review for all non-surgical clinical outcome conclusions, as was commonly encountered in the Cochrane review. This has significant potential to cause positive study bias. Substituting worst-case assumptions illustrates this.

For outcome “appendicitis” our study had 557/3478 presentations. Of these 11/557 were based on assumptions: 1 false negative based on a later presentation; 6 true positive based on response to intravenous antibiotics rather than surgery; 4 true positive based on “convincing” MRI changes, initial clinical agreement, went elsewhere for surgery with no further verification. To have excluded these would have disrupted the consecutive design of this review. For the worst-case scenario that all 11/11 should be false positive the adjusted totals of 539 true positive versus 42 false positive reports would still result in 98% sensitivity, 98% specificity, 98% accuracy for our cohort, protected by the large sample size.

For outcome “not appendicitis” our study had 2921/3478 presentations, 2,811 true negative on the assumption that none had represented with appendicitis diagnosis to another site using a different medical records system. For the worst-case scenario that all had presented to another site with missed appendicitis, with no feedback returned for this ongoing issue, the adjusted total of 2819 false negative reports versus 78 surgically confirmed true negative reports would result in 16% sensitivity, 70% specificity, 18% accuracy for our cohort, not protected by the large sample size. Although an unrealistic scenario this highlights the Cochrane review criticism that reliance on notes review for non-surgical follow-up is a substantial methodology weakness. Unfortunately, the much better alternative of follow-up telephone contact with every patient was beyond resources available to the authors, and hence could not be within study design scope.

A subgroup statistical limitation of this study is that the sample size for the youngest age group, 0-4 years old, is too small to be statistically relevant. Although these results can be incorporated into total cohort analysis without issue, meaningful subgroup analysis is not possible for this 0-4 years old age range individually, evidenced by reduced Phi coefficient for the subgroup total, and unrealistic discrepancy in all metrics when comparing males and females within this subgroup. Further studies would be needed to overcome this.

As a final limitation we describe in detail a specific protocol using specific equipment. Further studies would be worthwhile to show ability to effectively transfer this to other sites with other equipment. Mild adjustments to some parameters would likely be needed at some sites.