1. Introduction

Acute appendicitis (AA), with an incidence estimated between 100 and 150 cases per 100,000 population, represents one of the most common surgical emergencies in Western countries [

1]. Early diagnosis is of paramount importance as approximately 30% of AA cases result in perforation, which is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [

2,

3]. The clinical presentation of patients with AA is highly heterogeneous. Symptoms are often vague and may resemble various other abdominal conditions, making clinical assessment challenging [

2]. Laboratory markers such as leucocytosis and elevated CRP are used to support diagnosis. However, they are non-specific signs of inflammation [

4]. Thus, imaging plays a pivotal role in diagnosing AA. The imaging modalities of choice include abdominal ultrasound (US), computer tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

4,

5].

In emergency settings, a focused ultrasound examination, commonly referred to as “point-of-care ultrasound” (POCUS), is frequently used to address specific diagnostic questions. POCUS has shown high diagnostic accuracy, particularly in applications such as the extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (eFAST). In a meta-analysis by Netherton et al., sensitivities/specificities were 91%/94% for pericardial effusion, 74%/98% for intra-abdominal free fluid, and 69%/99% for pneumothorax [

6]. Furthermore, it has been shown that POCUS may reduce patient radiation exposure and save costs for the healthcare system as well as leading to a decreased length of stay in the emergency department (ED) [

6,

7].

POCUS has demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy for diagnosing acute appendicitis in children, with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 91%, as reported in a meta-analysis by Benabbas et al [

8]. However, in adults, the literature reports a wide range of sensitivity and specificity values (69–88% and 81–96%, respectively), as shown in meta-analyses of studies largely conducted by board-certified or experienced radiologists [

9]. This variability may be explained by differences in patient populations and various reference standards; moreover, the diagnostic accuracy significantly depends on the examiner’s experience. Non-radiologically trained physicians have shown lower diagnostic accuracy in POCUS for acute appendicitis in various studies [

9,

10].

The aim of the study was to analyse the impact of POCUS performed by the treating emergency physician, on the length of stay in the ED at a tertiary level hospital in Lucerne, Switzerland.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

We conducted a retrospective monocentre study of all consecutive patients presenting to the emergency department of the cantonal hospital of Lucerne, Switzerland, a university-affiliated tertiary teaching hospital. They all underwent an appendectomy due to acute appendicitis. The evaluation period spanned the years 2022 and 2023. The data used in this study including clinical history, demographics, laboratory data, diagnostic imaging and records were obtained from the electronic patient charts in EPIC (Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI, USA) and were approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (Project-ID 2023-00850, 8 august 2023).

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

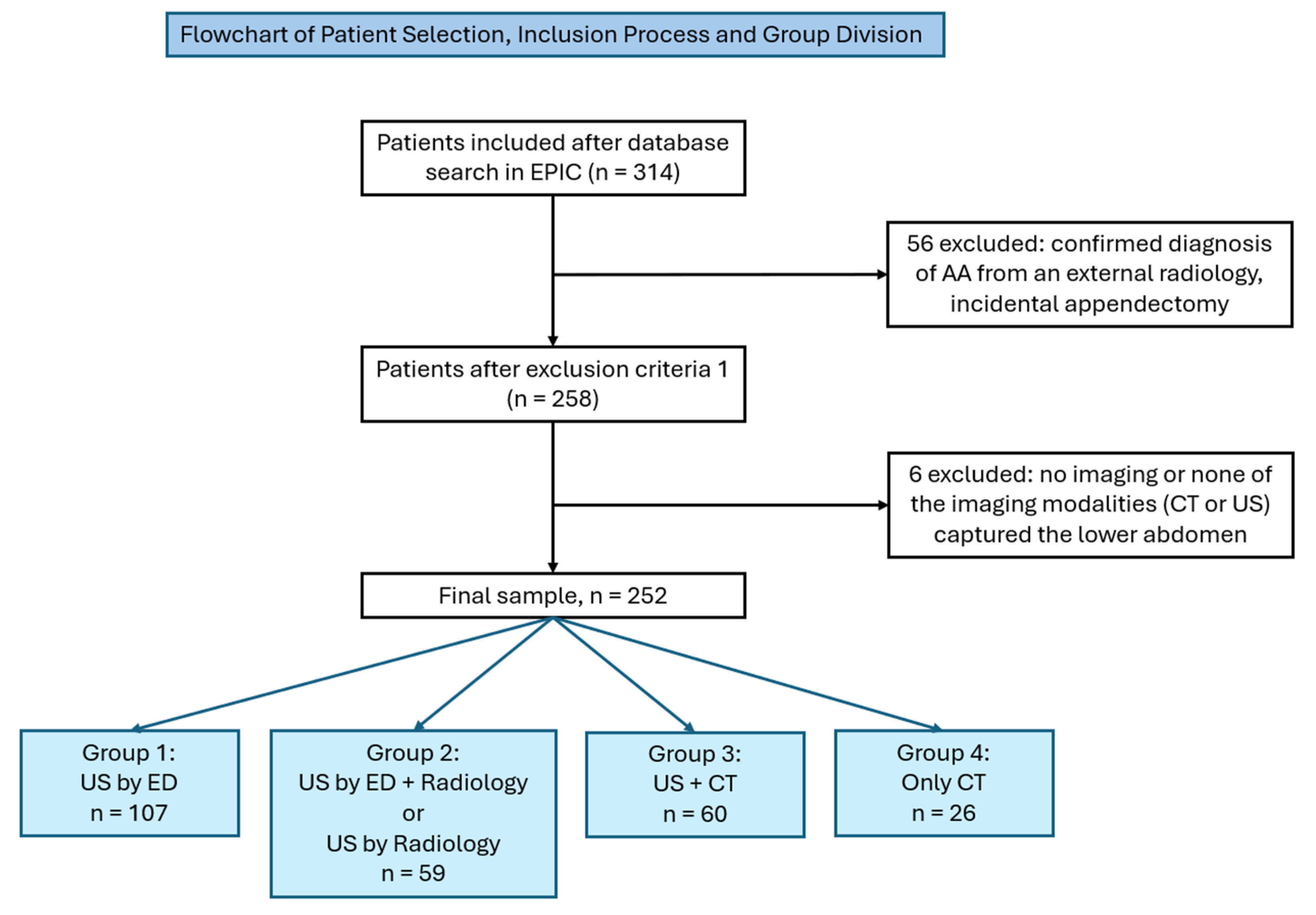

Patients included were at least 16 years old at the time of presentation. The patients had to be admitted through the emergency department of the cantonal hospital of Lucerne and undergo an appendectomy. Intraoperative findings were used for final adjudicated diagnosis of AA. Exclusion criteria encompassed patients with a confirmed external diagnosis of AA. If no imaging was performed or none of the imaging modalities (US or CT) captured the lower abdomen, the patient was not included in the study. Additionally, patients with a history of appendectomy or incidental appendectomy were excluded (

Figure 1).

2.3. Data Collection

Data from 252 patients were included in the analysis. The extracted data included age, sex, BMI and the laboratory value C-reactive-protein (CRP) [

8,

11]. The surgical report was used both to confirm the diagnosis of appendicitis and perforation, eventually. The imaging modality (US or CT), which was used to diagnose AA, was documented and whether it was performed by an emergency physician or a radiologist. US examinations were only included if a finding was recorded in the hospital information system and if it was performed by a specialist in emergency medicine or supervised by one. This distinction led to a division into four subgroups (

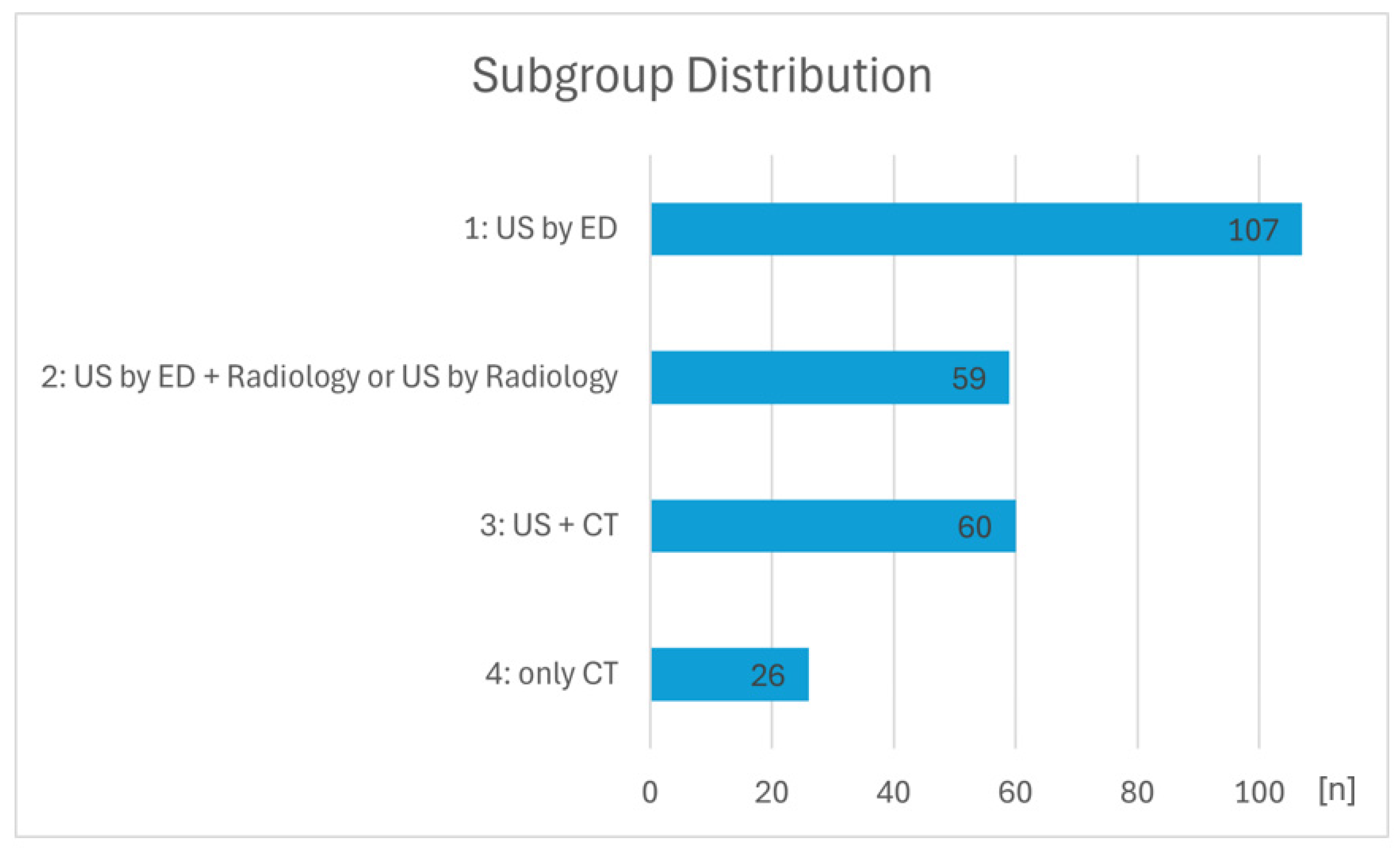

Figure 1). Group 1 summarises all patients which underwent only a POCUS examination through a specialist in emergency medicine. Group 2 summarises all patients which underwent a POCUS examination performed by both ED + radiology or only by radiology. Group 3 summarises all patients which underwent a POCUS examination and a CT imaging in addition. Group 4 summarises all patients which underwent only a CT imaging.

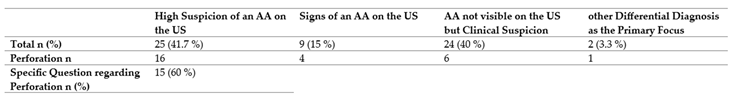

A subgroup analysis of all patients receiving CT imaging in addition to US (group 3) was performed based on physicians’ written information in the CT radiology request. This led to a classification into the following four categories: 1: high suspicion of an AA on the US, 2: signs of an AA on the US, 3: AA not visible on the US but clinical suspicion, 4: other differential diagnosis as the primary focus. Furthermore, in cases that showed a high suspicion of AA on the US (category 1), it was examined whether a specific inquiry about perforation was made.

Length of stay within the ED was measured using the electronic healthcare system EPIC, capturing the time from ED admission to referral to the preoperative ward.

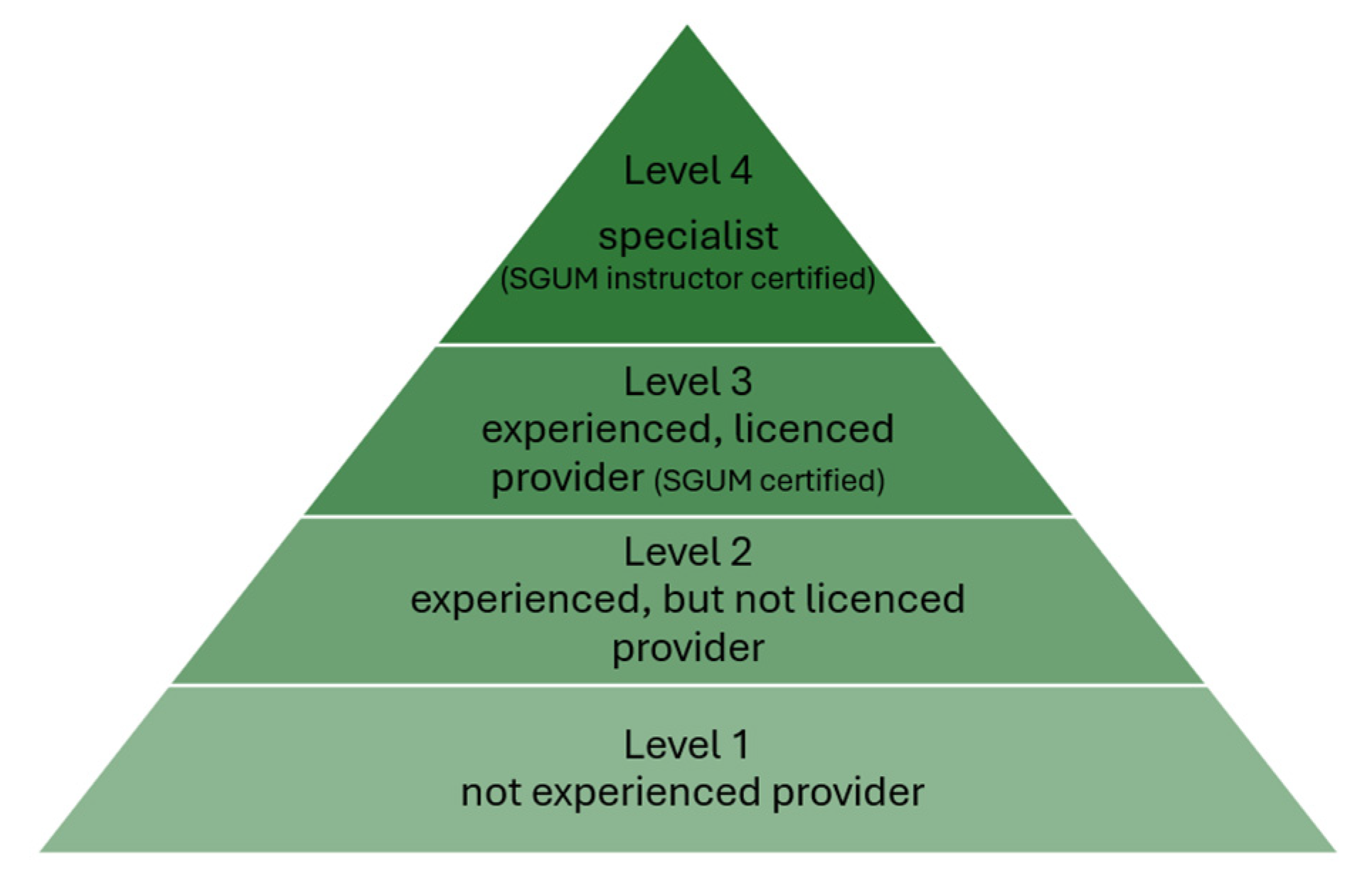

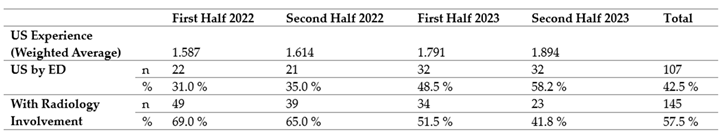

The US experience of the emergency physicians in the ED was assessed based on two criteria: the number of documented ultrasound examinations and the certification level of the “Swiss Society for Ultrasound in Medicine (SGUM)” (

Figure 2). To calculate a weighted average for statistical analysis, the number of available consultants was multiplied by an ascending factor of 4: 1x for “not experienced provider”, 2x for “experienced, but not licenced provider”, 3x for “experienced, licenced provider - SGUM certified”, 4x for “specialist - SGUM instructor certified”. The weighted average was aggregated into six-month periods. These data were anonymised and extracted from the personnel scheduling system (PEP).

2.4. Ultrasound-Based Identification of Appendicitis

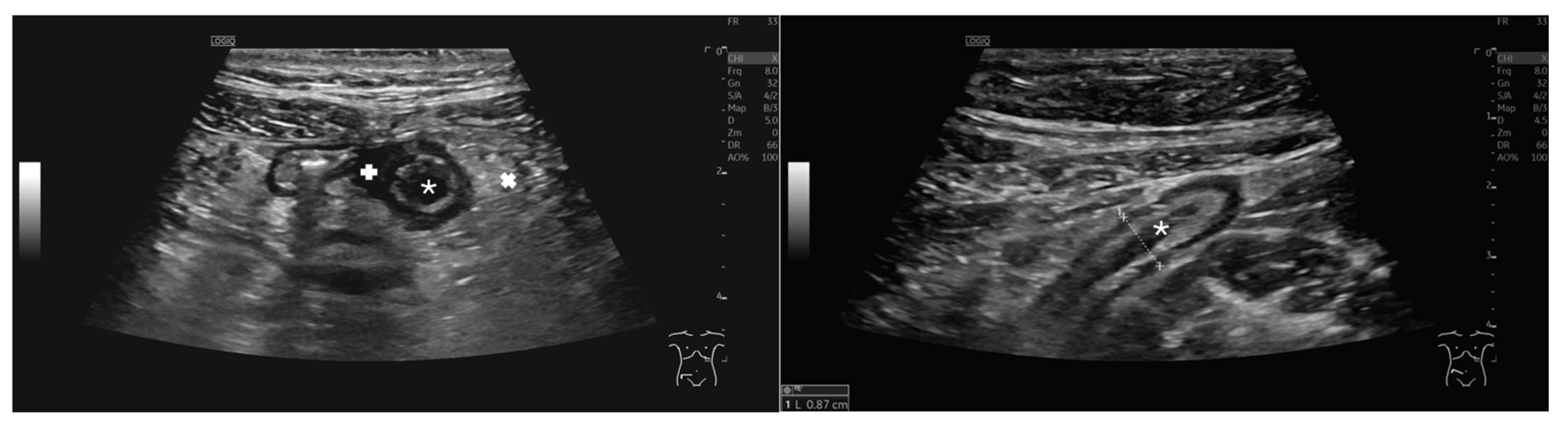

To reach a diagnosis using ultrasound, the examiners relied on established sonographic signs of acute appendicitis in conjunction with clinical evaluation. Typical ultrasound findings in AA include both direct and indirect signs, which are assessed in combination to support the diagnosis. Direct signs consist of a non-compressible appendix measuring more than 6 mm in diameter, as well as the “target sign”. Indirect signs may include free fluid around the appendix, increased echogenicity of the adjacent mesenteric fat and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes [

13,

14] (

Figure 3).

2.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

All data analyses were performed using SPSS software version 29.0.02 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Patient demographic characteristics and extracted variables were summarised using standard descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were tested for normal distribution. Non-normally distributed variables were described as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) and categorical variables as frequencies or percentages, unless stated otherwise.

For non-normally distributed variables, the Mann-Whitney-U-test and the Kruskal-Wallis-test were used for hypothesis analyses. The experience of the US examiners was calculated using a weighted average, in which greater experience resulted in a higher weighting. A multivariable linear regression was conducted to examine the relationship between the independent variables: age, sex, BMI, and CRP and the dependent variable: diagnosis based solely on ultrasound. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Total Population and Subgroup Distribution

A total of 314 patients were identified through screening of an appendectomy in the period of 2022 and 2023 in EPIC. After reviewing the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 62 patients were excluded from the study, resulting in a study population of 252 patients (

Figure 1).

Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of patient subgroups based on imaging modality. Most patients underwent ultrasound only, either in the ED or with radiology involvement. Fewer patients received both US and CT or only CT.

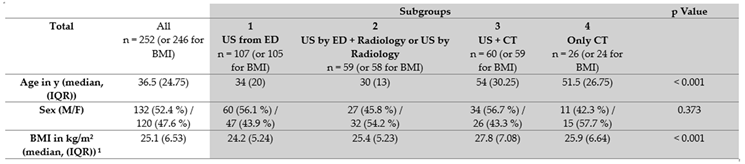

3.2. Patients’ Characteristics, Laboratory Value and Perforation Rate

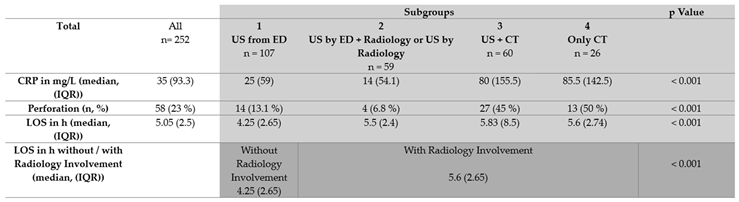

Table 1 demonstrates the demographic characteristics of the total population and the subdivision into subgroups. The sex distribution was similar and evenly balanced in the total population and across the subgroups (p=0.373). Age and BMI showed higher median values in the subgroup divisions with CT involvement compared to cases with ultrasound involvement alone (p <0.001). Additional variables extracted from the medical records are presented in

Table 2. CRP exhibited a median value of considerable variation across the subgroups with a significant difference (p <0.001). Perforation was documented in the operative findings of 58 (23%) patients. When a CT scan was performed, approximately half of the patients were diagnosed with perforated appendicitis. Both groups with CT involvement (group 3 + 4) together account for nearly 70% of all patients with perforations.

3.3. Length of Stay

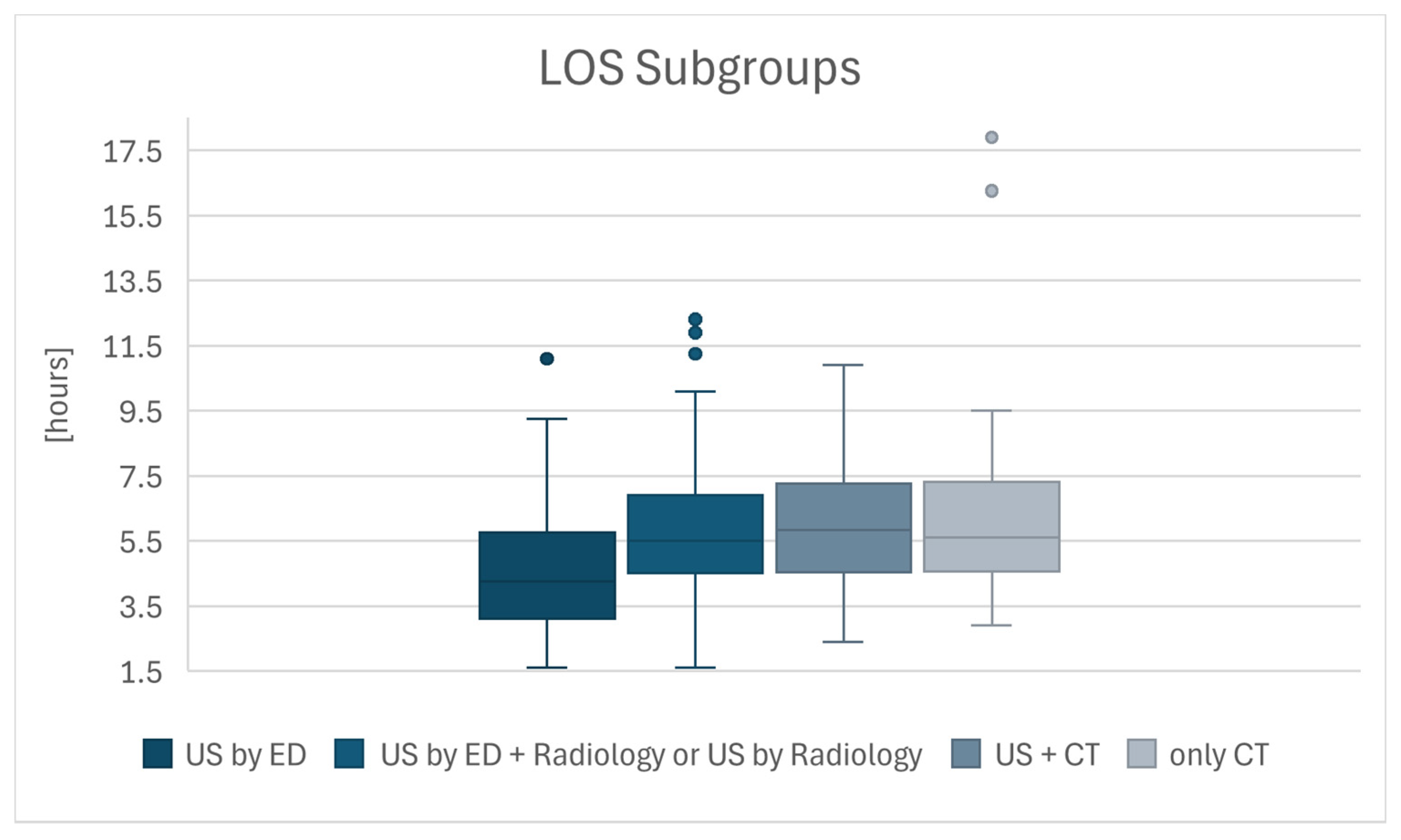

In median, the LOS from ED admission to referral to the preoperative ward was 5.05 hours. Furthermore, the median LOS, divided into subgroups, is also presented in

Table 2 and in the boxplot for further illustration (

Figure 5). The analysis revealed a significant difference in the LOS between the groups without (group 1) and with radiology involvement (group 2 + 3 + 4) (median [IQR]: 4.25 [2.65] vs. 5.6 [2.65] hours; U = 4304.5, p <0.001). Further analysis indicated a significant difference in the LOS between the four subgroups (H = 36.7, p <0.001). Post-hoc analysis showed that a significant difference in LOS was only observed when comparing group 1 (US by ED) with the other subgroups. Comparisons between groups 2 to 4, which all included radiology involvement, did not reveal any significant differences in LOS.

3.4. Analysis of the Reasons For performing a CT in Addition to US

The subgroup analysis of group 3 (n = 60) aimed to provide a more detailed verification of the reasons for performing a CT scan in addition to an ultrasound examination and yielded the following results (

Table 3). In 40% of the subgroup, the appendix could not be visualised on US, and based on clinical suspicion (symptoms, lab results, etc.), a CT scan was indicated to investigate the possibility of an AA. In a similar proportion of patients (41.7%, n=25), a strong suspicion of AA was already detected via US, yet a CT scan was still performed. In 9 patients (15%), signs of AA were visible on ultrasound but were insufficient to provide a definitive indication, leading to further imaging. In 3.3% of cases, another differential diagnosis was initially the focus or reason for a CT, and AA was either discovered or confirmed through the CT scan.

Further analysis of the 25 patients who underwent a CT scan despite a strong suspicion of an AA in the US examination revealed that in 60% of the cases, the specific question regarding perforation was raised. In the remaining 40%, this question was not explicitly addressed in the radiology request. Among these 25 patients, 16 (59.3%) were found to have a perforated appendix.

3.5. US Experience

The ultrasound experience, represented by the weighted average, showed a temporal trend (

Table 4). From 2022 to 2023, the ultrasound experience of the emergency physicians increased. In parallel, there was a proportional increase in cases that were diagnosed solely by US in the ED.

3.6. Linear Regression

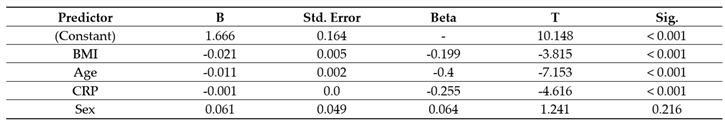

The linear regression indicates that a younger age (β = -0.4, p = < 0.001), lower BMI (β = -0.199, p = < 0.001), and lower CRP (β = -0.255, p = < 0.001) significantly increase the likelihood of diagnosing appendicitis solely through ultrasound without the need for additional CT imaging (

Table A1). The model accounted for 37.3% of the variance in diagnostic success (R² = 0.373). Sex proved to be a non-significant variable (β = 0.064, p = 0.216).

4. Discussion

In this study, we observed a significant association between the length of stay in the emergency department and the use of ultrasound performed solely by the attending emergency physician as the primary imaging modality in 252 patients with acute appendicitis. The advantages of lower LOS in the ED reported in the literature include higher patient satisfaction and quality of care [

15,

16]. While some studies report a reduction in short term mortality associated with decreased LOS in ED patients with low medical priority (RETTS-A levels 3-5), others find no significant impact, reflection ongoing debate in the field [

17,

18,

19]. There is not enough evidence to support the general assumption that a shorter length of stay (LOS) leads to improved patient outcomes, such as reduced mortality. However, in older patients in particular, the risk of adverse events increases with prolonged hospital stays [

20,

21]. The effect of a long LOS on emergency department crowding is undisputed [

22]. In times of limited spatial and personnel resources, patient throughput is crucial for ensuring optimal efficiency in emergency departments [

23].

Although sensitivity and specificity could not be determined due to the study design, a conclusive diagnosis could be established by ultrasound in 65.9% of cases, supported by existing literature [

8,

24]. Since all patients with appendicitis were admitted via the emergency department, this proportion corresponds to the overall rate among all treated appendicitis cases.

The likelihood of requiring CT imaging increased with higher patient age, BMI, and inflammatory marker levels. These factors can be interpreted as indicators of a more complicated clinical course. Correspondingly, regression analysis showed a strong association between lower age, BMI and CRP values and the likelihood of diagnosing appendicitis solely through ultrasound. Thus, straightforward and uncomplicated cases can often be diagnosed quickly and efficiently by the treating emergency physician with no further testing needed while complicated cases often seem to require radiological expertise [

8]. A positive ED-POCUS is thus diagnostic. Frequently, CT imaging was indicated to preoperatively assess complications such as perforation. The decision to perform supplementary or exclusive CT imaging depended on the individual physician, particularly the surgeon. The development of a standardised diagnostic protocol could be advantageous in this context.

In the present study, the proportion of US performed by ED patients increased over the years, correlating with the weighted average competency level. Previous studies that demonstrated higher sensitivity and specificity of emergency ultrasound examinations with increasing physician experience are thus supported by our findings [

25]. Greater ultrasound experience may significantly reduce the number of radiation-intensive examinations as well as the length of stay (LOS), as the need for additional CT imaging is frequently obviated. Several studies have demonstrated that the use of ultrasound as a primary imaging modality, without subsequent CT, can lead to significant cost savings in healthcare by reducing the need for expensive imaging and associated hospital resources [

26,

27].

Limitations

Due to the retrospective nature of this study, complete data collection cannot be guaranteed. In particular, cases may have been missed due to coding errors in the discharge diagnosis; however, this source of error is considered negligible due to the highly advanced hospital information system. The reasons for the omission of ultrasound examinations were not documented. Technical issues (e.g., IT system failures, equipment defects) or staffing factors (e.g., personnel shortages) in addition to medical considerations may have contributed. Moreover, this is a monocentre study characterised by high ultrasound expertise and experience among the treating emergency physicians. Therefore, the findings cannot be readily generalised to other emergency departments or less experienced settings. Ultrasound examinations were performed during routine clinical care, making inter- and intra-observer variability unavoidable. Not all investigators were certified ultrasound examiners. Furthermore, no internal or external validation of the study was performed, highlighting the need for larger multicentre studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.V. and M.S.; methodology, M.S. and S.V.; validation, M.S., S.V. and M.C.; formal analysis, M.S.; investigation, M.S.; resources, S.V. and M.S.; data curation, M.S. and F.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S..; writing—review and editing, S.V., L.S., M.C. and M.S.; visualization, M.S.; supervision, M.C.; project administration, S.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Northwestern and Central Switzerland (Project-ID 2023-00850, 8 august 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was either available or, in cases where no documented consent was present, the study was conducted under the exemption approval in accordance with Article 34 of the Swiss Human Research Act as specified in the ethics application (Project-ID 2023-00850, 8 august 2023).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AA |

Acute appendicitis |

| US |

Ultrasound |

| CT |

Computer tomography |

| MRI |

Magnetic resonance imaging |

| POCUS |

Point of care ultrasound |

| ED |

Emergency department |

| eFAST |

Extended Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma |

| LOS |

Length of stay |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1.

Linear regression analysis of predictive factors for diagnosis of AA by ultrasound alone. Dependent variable = only US. Predictors = (Constant), CRP, BMI, Sex, Age. R² = 0.373.

Table A1.

Linear regression analysis of predictive factors for diagnosis of AA by ultrasound alone. Dependent variable = only US. Predictors = (Constant), CRP, BMI, Sex, Age. R² = 0.373.

References

- Ferris M, Quan S, Kaplan BS, et al. The Global Incidence of Appendicitis: A Systematic Review of Population-based Studies. Annals of Surgery 2017; 266: 237–241. [CrossRef]

- Sartelli M, Baiocchi GL, Di Saverio S, et al. Prospective Observational Study on acute Appendicitis Worldwide (POSAW). World J Emerg Surg 2018; 13: 19. [CrossRef]

- Barrett ML, Hines AL, Andrews RM. Trends in Rates of Perforated Appendix, 2001–2010. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006.

- Téoule P, De Laffolie J, Rolle U, et al. Acute Appendicitis in Childhood and Adulthood: An Everyday Clinical Challenge. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international 2020; [CrossRef]

- Bom WJ, Scheijmans JCG, Salminen P, et al. Diagnosis of Uncomplicated and Complicated Appendicitis in Adults. Scand J Surg 2021; 110: 170–179. [CrossRef]

- Arnold MJ, Jonas CE. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography. 2020; 101.

- Li JJ, Boivin Z, Bhalodkar S, et al. Point of Care Abdominal Ultrasound. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI 2024; 45: 11–21. [CrossRef]

- Benabbas R, Hanna M, Shah J, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of History, Physical Examination, Laboratory Tests, and Point-of-care Ultrasound for Pediatric Acute Appendicitis in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Academic Emergency Medicine 2017; 24: 523–551. [CrossRef]

- Matthew Fields J, Davis J, Alsup C, et al. Accuracy of Point-of-care Ultrasonography for Diagnosing Acute Appendicitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Academic Emergency Medicine 2017; 24: 1124–1136. [CrossRef]

- Cho SU, Oh SK. Accuracy of ultrasound for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the emergency department: A systematic review. Medicine 2023; 102: e33397. [CrossRef]

- Tsioplis C, Brockschmidt C, Sander S, et al. Factors influencing the course of acute appendicitis in adults and children. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2013; 398: 857–867. [CrossRef]

- World Interactive Network Focused On Critical UltraSound ECHO-ICU Group, Price S, Via G, et al. Echocardiography practice, training and accreditation in the intensive care: document for the World Interactive Network Focused on Critical Ultrasound (WINFOCUS). Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2008; 6: 49. [CrossRef]

- Mostbeck G, Adam EJ, Nielsen MB, et al. How to diagnose acute appendicitis: ultrasound first. Insights Imaging 2016; 7: 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Quigley AJ, Stafrace S. Ultrasound assessment of acute appendicitis in paediatric patients: methodology and pictorial overview of findings seen. Insights Imaging 2013; 4: 741–751. [CrossRef]

- Chang AM, Lin A, Fu R, et al. Associations of Emergency Department Length of Stay With Publicly Reported Quality-of-care Measures. Academic Emergency Medicine 2017; 24: 246–250. [CrossRef]

- Andersson J, Nordgren L, Cheng I, et al. Long emergency department length of stay: A concept analysis. International Emergency Nursing 2020; 53: 100930. [CrossRef]

- Wessman T, Ärnlöv J, Carlsson AC, et al. The association between length of stay in the emergency department and short-term mortality. Intern Emerg Med 2022; 17: 233–240. [CrossRef]

- Guttmann A, Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, et al. Association between waiting times and short term mortality and hospital admission after departure from emergency department: population based cohort study from Ontario, Canada. BMJ 2011; 342: d2983–d2983. [CrossRef]

- Burgess L, Ray-Barruel G, Kynoch K. Association between emergency department length of stay and patient outcomes: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health 2022; 45: 59–93. [CrossRef]

- Diercks DB, Roe MT, Chen AY, et al. Prolonged Emergency Department Stays of Non–ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Patients Are Associated With Worse Adherence to the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines for Management and Increased Adverse Events. Annals of Emergency Medicine 2007; 50: 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Ackroyd-Stolarz S, Read Guernsey J, MacKinnon NJ, et al. The association between a prolonged stay in the emergency department and adverse events in older patients admitted to hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Quality & Safety 2011; 20: 564–569. [CrossRef]

- Henneman PL, Nathanson BH, Li H, et al. Emergency Department Patients Who Stay More Than 6 Hours Contribute to Crowding. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 2010; 39: 105–112. [CrossRef]

- Pines JM, Hilton JA, Weber EJ, et al. International Perspectives on Emergency Department Crowding: INTERNATIONAL PERSPECTIVES ON ED CROWDING. Academic Emergency Medicine 2011; 18: 1358–1370. [CrossRef]

- Lehmann B, Koeferli U, Sauter TC, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of a pragmatic, ultrasound-based approach to adult patients with suspected acute appendicitis in the ED. Emerg Med J 2022; 39: 931–936. [CrossRef]

- Kim J, Kim K, Kim J, et al. The learning curve in diagnosing acute appendicitis with emergency sonography among novice emergency medicine residents. J of Clinical Ultrasound 2018; 46: 305–310. [CrossRef]

- Barton MF, Barton KM, Goldsmith AJ, et al. POCUS-first in acute diverticulitis: Quantifying cost savings, length-of-stay reduction, and radiation risk mitigation in the ED. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 2025; 88: 204–212. [CrossRef]

- Van Schaik GWW, Van Schaik KD, Murphy MC. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography (POCUS) in a Community Emergency Department: An Analysis of Decision Making and Cost Savings Associated With POCUS. J of Ultrasound Medicine 2019; 38: 2133–2140. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).