1. Introduction

Acute appendicitis (AA) is among the most common causes of lower abdominal pain leading to emergency department visits and often to urgent abdominal surgery [

1]. As much as 95% of the patients with uncomplicated acute appendicitis eventually undergo surgical treatment [

2].

The incidence of acute appendicitis (AA) has shown a steady decline worldwide since the late 1940s. In developed nations, the occurrence of AA ranges from 5.7 to 50 cases per 100,000 inhabitants annually, with the highest incidence observed in individuals between the ages of 10 and 30 years old [

3,

4]. Regional differences play a significant role in the lifetime risk of developing AA, with reported rates of 9% in the United States, 8% in Europe, and a much lower than 2% in Africa [

5]. Furthermore, there is considerable variation in the clinical presentation of AA upon presentation at the doctor, the severity of the disease and the time it takes from first onset of symptoms to the acute phase, the approach to radiological diagnosis, and the surgical management of patients, which is influenced among others by the economic status of the country [

6].

The rate of appendiceal perforation, a serious complication of AA, varies widely, ranging from 16% to 40% [

7]. This complication is more frequently seen in younger patients, with perforation rates between 40% and 57%, and in those over 50 years of age, where rates range from 55% to 70% [

7]. Appendiceal perforation due to e.g. delayed presentation is particularly concerning as it is linked to significantly higher morbidity and mortality compared to non-perforating cases of AA.

In one cohort [

8], perforation was found in 13.8% of the cases of acute appendicitis and presented mostly in the age group of 21–30 years. Patients presented in 100% with abdominal pain, followed by vomiting (64.3%) and fever (38.9%). Patients with perforated appendicitis had a very high (72.2%) complication rate (mostly intestinal obstruction, intra-abdominal abcess and incisional hernia. The mortality rate in this cohort with perforated appendicitis was 4.8%.

The clinical diagnosis of AA is often challenging and involves a combination of clinical (e.g. physical examination findings such as a positive Psoas, Rovsign and McBurney sign that may indicate peritonitis), age, vital signs such as temperature and blood pressure , laboratory (e.g. CRP, leucocytes), and radiological findings (ultrasound as well as computed tomography, depending on patient constitution and clinician’s preference ) [

9]. In the emergency department, when a patient is suspected of having appendicitis, a thorough workup is essential to make an accurate diagnosis and determine the appropriate treatment plan. As mentioned, time is of the essence as appendiceal perforation is associated with a high complication rate.

Appendectomy has for a long time been the standard treatment for appendicitis, even though successful use of antibiotic therapy as an alternative was reported as early as 65 years ago [

10].

Evidence for antibiotics first-treatment has had renewed interest with several randomized controlled trials concluding that a majority of patients with acute, uncomplicated (nonperforated) appendicitis (AUA) can be treated safely with an antibiotics-first strategy (conservatively), with rescue appendectomy if indicated [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

With the recent worldwide coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19), health systems and professional societies e.g. the American College of Surgeons [

16] have proposed reconsideration of many aspects of care delivery, including the role of antibiotics in the treatment of appendicitis without signs indicative of high risk for perforation, in individuals unfit for surgery or those having concerns to undergo operation (choice to be made through shared decision making between patient and clinician).

The ultimate decision between explorative laparoscopy/appendectomy and conservative treatment should be made on a case-by-case basis, and while simple and user-friendly scoring systems such as the Alvarado score have been used by clinicians as a structured algorithm to aid in predicting the risk stratum of AA [

1], such scoring systems are often unreliable, confusing and not widely adopted by clinicians. Algorithms that rely on high throughput real-world data may in this light be of current interest.

In recent years, the field of artificial intelligence (AI) has witnessed remarkable advancements, for instance in the field of natural language processing (NLP) with most prominent applications including chat bots, text classification, speech recognition, language translation, and the generation or summarization of texts.

In 2017, Vaswani et al. [

17] introduced the Transformer deep learning model architecture, replacing previously widely used recurrent neural networks (RNN) [

18], deep learning models that are trained to process and convert a sequential data input into a specific sequential data output.

Transformers, characterized by their feedforward networks and specialized attention blocks, represent a significant advancement in neural network architecture, particularly in overcoming the limitations of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs). Unlike RNNs, where each computation step depends on the previous one, Transformers can process input sequences in parallel, significantly improving computational efficiency. Additionally, the attention blocks within Transformers enable the model to learn long-term dependencies by selectively focusing on different segments of the input data [

19]. A basic Transformer network comprises of an encoder and a decoder stack, each consisting of several identical blocks of feed-forward neural [

17]. The encoder processes an input sequence to produce a set of context vectors, which are then used by the decoder to generate an output sequence. In case of a Transformer both the input and output are text sequences, where the words are tokenized (broken down into smaller units called tokens) and represented as elements in a high-dimensional vector [

19].

Large Language Models (LLMs) refer to large Transformer models trained on extensive datasets [

19].

Chat GPT-3.5 (Generative Pre-trained Transformer), an LLM, is one of the NLP architectures developed by OpenAI to output an AI chatbot which has been pre-trained on online journals, Wikipedia and books [

20]. It is a so called large language model (LLM) that uses deep learning techniques to achieve general-purpose language understanding and generation that has gained widespread attention for its ability to generate human-like text based on a given input. The technology has shown promise in various applications, including language translation, content generation and summarization.

One of the primary challenges in the management of hospital medical records is the need to maintain the accuracy and consistency of information. Healthcare providers must be able to quickly access and update patient records, ensuring that the data is both accurate and up-to-date. GPT’s can assist in this process by automatically generating summaries of medical records, allowing healthcare professionals to quickly review and update the information as needed. Moreover, GPT’s can be utilized to improve the interoperability of medical records. As healthcare systems become more interconnected, the need for seamless data exchange between different providers and institutions becomes crucial. GPT’s can help bridge the gap between disparate electronic health record systems by translating medical records into a standardized format, facilitating smoother data exchange and reducing the risk of miscommunication.

Clinical decision support systems (DSSs), continuously learning artificial intelligence platforms can integrate all available data-clinical, imaging, biologic, genetic, validated predictive models and may help doctors by providing patient-specific recommendations. GPT’s may be able to assist by interpreting these recommendations, explaining the rationale behind them, and answering related clinical questions, thereby enhancing the decision-making process.

There are several promising results in the current literature as of august 2024 with the use of GPT’s in the high data throughput environment of the Radiology Department, for instance in helping the radiologist with choosing the appropriate radiologic study and scanning protocol, adequate differential diagnosis and potentially even with automated reporting [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].ChatGPT nevertheless often faces criticism for its inaccuracies, limited functionality, lack of transparency in citation sources, and the need for thorough verification by the end-user. These limitations pose several potential risks, including plagiarism, hallucinations (where the model fabricates or misrepresents information), academic misconduct, and various other ethical concerns [

26,

27,

28]. Therefore, ChatGPT is in our opinion better suited as a supplementary tool in the medical field rather than a primary information resource as errors in the information generated by ChatGPT could have serious implications for an individual’s health. Research should in our opinion be focused on providing the algorithm with abundant real world data, provide the algorithm proper context and see how it performs in comparison to individual healthcare domain-experts.

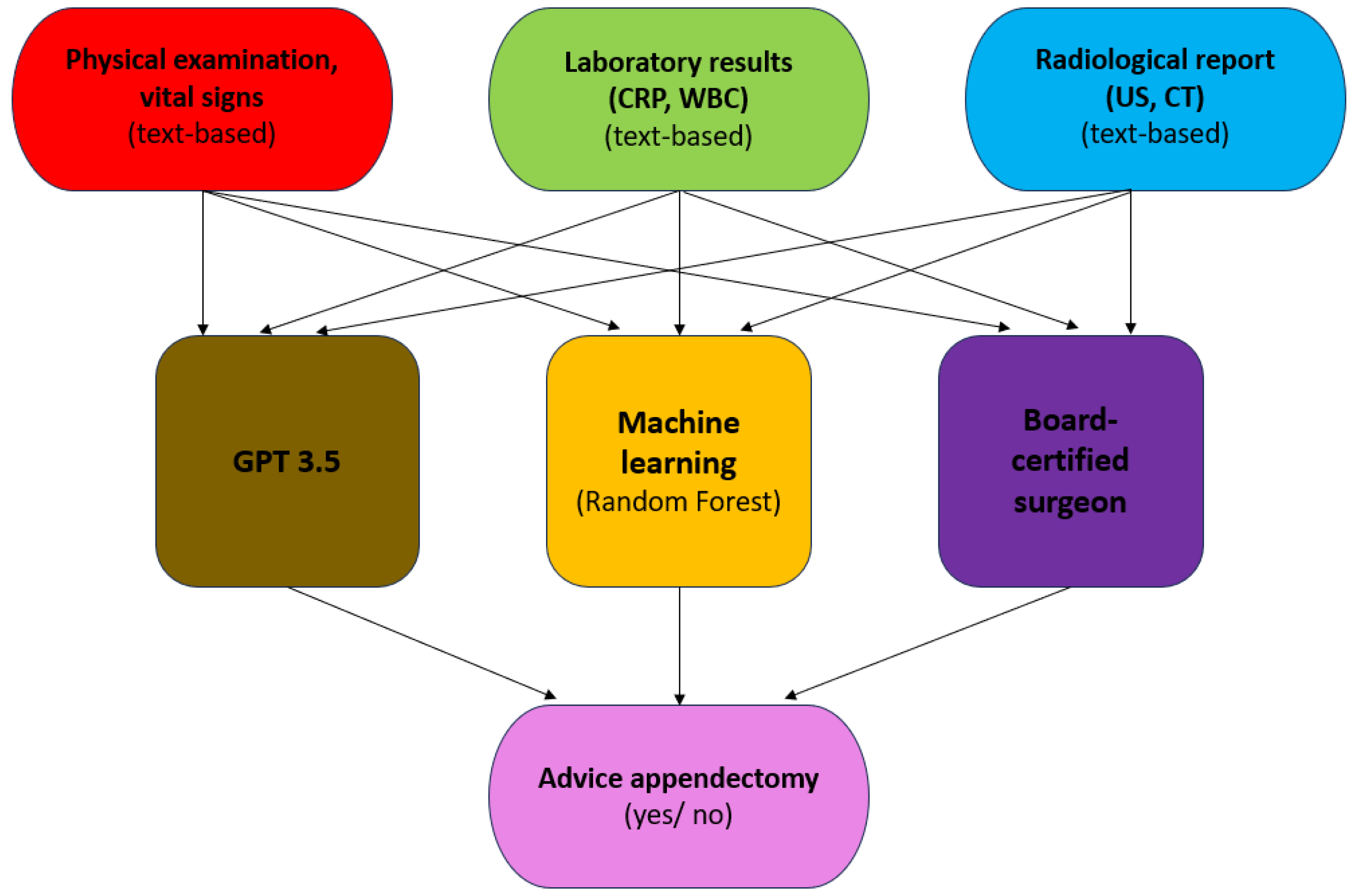

Our hypothesis in this study is that GPT-3.5 as well as a machine learning model, when provided high throughput clinical, laboratory and radiological text-based information will come to similar clinical decisions as a board-certified surgeon on the requirement of explorative laparoscopic investigation/ appendectomy or conservative treatment in patients presenting with acute abdominal pain at the Emergency Department.

2. Materials and Methods

This study received ethical approval (file number 23–1061-retro) by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of GFO Kliniken Troisdorf, and informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design of the study. No patient-identifying information was provided to the artificial intelligence.

2.1. Workflow

We randomly collected n=63 consecutive histopathological-confirmed appendicitis patients and n=50 control patients presenting with right abdominal pain at the Emergency Department of two German hospitals (GFO, Troisdorf and University Hospital Cologne) between October 2022 and October 2023.

For both groups, the following exclusion criteria applied: a) incomplete vital signs upon admission at the Emergency Department (temperature, blood pressure and respiratory rate) b) missing physical examination findings c) missing CRP and leucocyte count d) missing ultrasound examination findings in the surgically-confirmed appendicitis cases that did not undergo an abdominal CT examination e) patient had contra-indications for surgery (e.g. inability to tolerate general anesthesia).

Physical examination signs taken into account were [

36]: a) McBurney sign (maximum pain in the middle of the imaginary connecting Monro line between the navel and the anterior superior dextra iliac spine) b) Blumberg sign (contralateral release pain e.g. pain on the right when releasing the compressed abdominal wall in the left lower abdomen) c) right lower quadrant release pain d) Rovsign sign (pain in the right lower abdomen when extending the colon against the cecal pole) e)

Psoas sign (pain in the right lower abdomen when lifting the straight right leg against resistance.

Based on each patient’s clinical, laboratory and radiological findings (full reports), GPT-3.5 was accessed via ChatGPT (

https://chat.openai.com/) in October 2023 asked to determine the optimal course of treatment, namely laparoscopic exploration/ appendectomy or conservative treatment with antibiotics using zero-shot prompting and same dialogue box for each case to potentially enhance context awareness of the model.

Additionally a Random Forest- based machine learning classifier was trained and validated to determine the optimal course of treatment based on the same information that was provided to GPT-3.5 , albeit in a more structured data format.

It is important to mention that in all cases where GPT3.5 did not provide a clear cut answer it was prompted to give it’s best guess estimate based on the provided information.

The results were compared with an expert decision determined by 6 board-certified surgeons with at least 2 years of experience, which was defined as the reference standard.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R, version 3.6.2, on RStudio, version 2023.03.0+386 (

https://cran.r-project.org/). Overall agreement between GPT-3.5 output and the reference standard was assessed by means of inter-observer kappa values as well as accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value) with the “Caret” and “irr” package.

Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

2.3. Machine Learning Model Development

A random forest (RF) machine-learning classifier was computed (default settings: 500 trees, mtry = √ nr. of predictors, without internal cross-validation) and validated in an external validation cohort taking into account variables such as “age”, “physical examination”, “breathing rate”, “systolic/ diastolic blood pressure”, “temperature”, “CRP”, “leucocyte count”, “ultrasound findings” and “CT findings” indicative of appendicitis upon admission at the Emergency Department.

The “randomForest” package was used, which implements Breiman's random forest algorithm (based on Breiman and Cutler's original Fortran code) for both classification and regression tasks.

The “predict” function was used to predict the label of a new set of data from the given trained model, while the “roc” function (pROC package) was used to build a ROC curve and returns a “roc” object. McNemar's Test was used to compare the predictive accuracy of the machine learning model versus the GPT-3.5 output (based on the correct/ false classification according to the decision made by the board certified surgeon.

3. Results

In total n = 113 patients (n= 63 appendicitis patients confirmed by histopathology and n= 50 control patients presenting with lower abdominal pain) were included in the analysis across independent patient cohorts from two German hospitals (University Hospital Cologne and GFO Kliniken, Troisdorf). Both macroscopically mild, moderate as well as severely inflamed appendix cases were included in the analysis.

In the first cohort from GFO Kliniken Troisdorf (n = 100) a total n= 50 appendicitis patients confirmed by histopathology and n= 50 control patients presenting with lower abdominal pain were included (median age 35 yrs, 57% female). Upon admission to the Emergency Department an ultrasound examination was performed in all patients, while in 29 % of the patients a CT-examination was performed.

On average 1.12 signs indicative of appendicitis were found upon physical examination (Psoas sign, Rovsign sign, McBurney/ Lanz, release pain etc.) in the appendicitis-confirmed group, while in the control group on average only 0.24 physical examination signs were found.

The average temperature upon admission was 36.8°C in the appendicitis-confirmed cases and 36.6°C in the control group. The average CRP and leucocyte values were 5.85 mg/dl and 12.82/μl respectively in the appendicitis group and 1.19 mg/dl and 8.14 /μl respectively in the control group.

In the second cohort from Cologne (n = 13) a total n= 13 appendicitis patients confirmed by histopathology were included (median age 22 yrs, 38% female).

On average 1.31 signs indicative of appendicitis were found upon physical examination (Psoas sign, Rovsign sign, McBurney/ Lanz, release pain etc.).

The average temperature upon admission was 36.5°C, while the average CRP and leucocyte values were 3.51 mg/dl and 13.43/μl respectively.

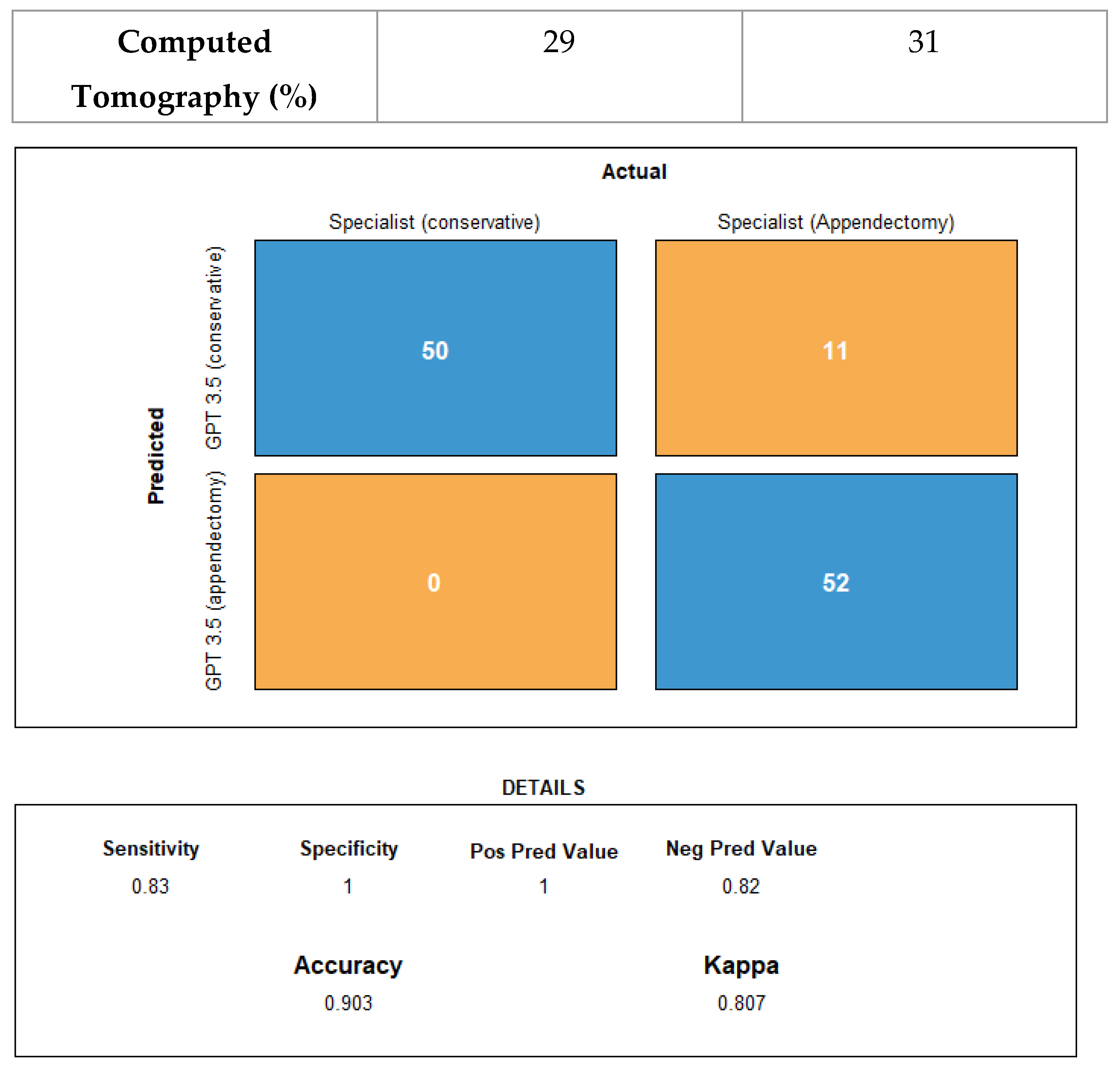

There was agreement between the reference standard (expert decision – appendicitis confirmed by histopathology) and GPT-3.5 in 102 of 113 cases (accuracy 90.3%; 95% CI: 83.2, 95.0), with an inter-observer Cohen’s kappa of 0.81 (CI: 0.70, 0.91).

All cases where the surgeon decided upon conservative treatment were correctly classified by GPT-3.5. With a specificity of 100% a positive GPT-3.5 result tends to rule in all patients that require surgery according to the surgeon, while the sensitivity of GPT-3.5 with respect to reference standard was 83%.

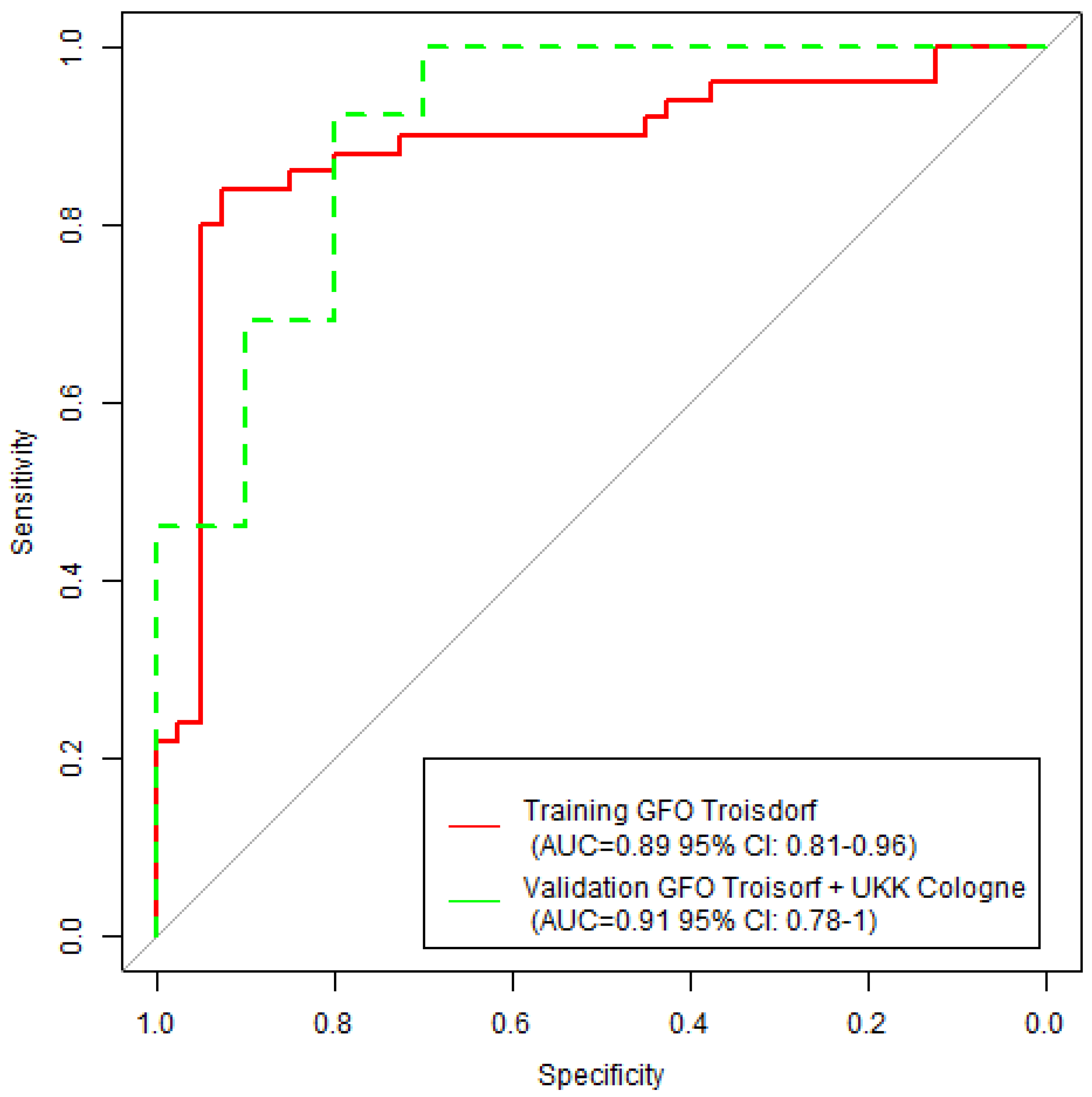

Figure 3 presents training and validation ROC-curves obtained by machine learning with a Random Forest model. The training cohort (n = 90) consisted of n = 50 appendicitis confirmed cases and n = 40 controls from GFO Troisdorf, while the validation cohort (n = 23) consisted of all n = 13 appendicitis confirmed cased from Cologne and n = 10 remaining controls from GFO Troisdorf.

The Random Forest model reached an AUC of 0.89 (CI: 0.81, 0.96) in the training cohort and an AUC of 0.91 (CI: 0.78, 1.0) in the validation cohort.

Table 1 presents the individual patient characteristics per hospital cohort, while

Figure 2 depicts a confusion matrix comparison constituting both cohorts between specialist decision (board-certified surgeon) decision versus GPT-3.5 decision on (explorative) appendectomy or conservative treatment.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix constituting both the GFO Troisdorf and the Cologne cohort (n=113). Comparisons are made between specialist decision (board-certified surgeon) decision versus GPT-3.5 decision on (explorative) appendectomy or conservative treatment.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix constituting both the GFO Troisdorf and the Cologne cohort (n=113). Comparisons are made between specialist decision (board-certified surgeon) decision versus GPT-3.5 decision on (explorative) appendectomy or conservative treatment.

The estimated machine learning model training accuracy was 83.3 % (95% CI: 74.0, 90.4), while the validation accuracy for the model was 87.0 % (95% CI: 66.4, 97.2). This in comparison to the GPT-3.5 accuracy of 90.3% (95% CI: 83.2, 95.0), which did not perform significantly better in comparison to the machine learning model (McNemar P = 0.21).

Figure 3.

Training (red) and validation (green) Random Forrest machine learning ROC-curves including area-under-the-curve metrics and confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Training (red) and validation (green) Random Forrest machine learning ROC-curves including area-under-the-curve metrics and confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

This multicenter study found a high degree of agreement between board certified surgeons and GPT-3.5 in the clinical, laboratory and radiological parameter informed decision for laparoscopic explorative surgery/ appendectomy versus conservative treatment in patient presenting at the emergency department with lower abdominal pain.

Several medical studies were performed previously prompting GPT 3.5/4 to evaluate its performance of at selecting correct imaging studies and protocols based on medical history and corresponding clinical questions extracted from Radiology Request Forms (RRFs) [

22], determining top differential diagnoses based on imaging patterns [

23], generating accurate differential diagnoses in undifferentiated patients based on physician notes recorded at initial ED presentation [

24] as well as acting as a chatbot-based symptom checker [

25].

In the emergency department another study [

26] conducted an analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of ChatGPT in assisting healthcare providers with triage decisions for patients with metastatic prostate cancer in the emergency room. ChatGPT was found to have a high sensitivity of 95.7% in correctly identifying patients who needed to be admitted to the hospital. However, its specificity was much lower, at 18.2%, in identifying patients who could be safely discharged. Despite the low specificity, the authors concluded that ChatGPT's high sensitivity indicates a strong ability to correctly identify patients requiring admission, accurately diagnose conditions, and offer additional treatment recommendations. As a result, the study suggests that ChatGPT could potentially improve patient classification, leading to more efficient and higher-quality care in emergency settings.

In the field of general surgery a recent study [

27] compared Chat GPT 4 with junior, senior residents as well as attendings at identifying the correct operation to perform and recommending additional workup for postoperative complications in five clinical scenarios. Each clinical scenario was run through Chat GPT-4 and sent electronically to all general surgery residents and attendings at a single institution. The authors found that GPT 4 was significantly better than junior residents (P = .009) but was not significantly different from senior residents or attendings.

Another study [

28] evaluated the performance of ChatGPT-4 on

surgical questions, finding a near or above human-level performance. Performance was evaluated on the Surgical Council on Resident Education question bank and a second commonly used surgical knowledge assessment. This study revealed that the GPT model correctly answered 71.3% and 67.9% of multiple choice and 47.9% and 66.1% of open-ended questions for Surgical Council on Resident Education, respectively. Common reasons for incorrect responses by the model included inaccurate information in a complex question (n = 16, 36.4%), inaccurate information in a fact-based question (n = 11, 25.0%), and accurate information with circumstantial discrepancy (n = 6, 13.6%). The study highlights the need for further refinement of large language models to ensure safe and consistent application in healthcare settings. Despite its strong performance, the suitability of ChatGPT for assisting clinicians remains uncertain.A significant aspect of the ChatGPT model’s development is that its training primarily depends on general medical knowledge that is widely available on the internet. This approach is necessitated by the difficulty of integrating large datasets of patient-specific information into the model's training process. The challenge arises from the stringent requirements to protect patient privacy and adhere to ethical standards, which limit access to detailed, real-world clinical data. As a result, ChatGPT's responses to medical queries may lack the depth and specificity that come from direct exposure to extensive patient data. This reliance on publicly available information introduces a degree of non-scientific specificity into the model’s medical-related outputs. Consequently, while ChatGPT can provide general guidance and information, it may not always offer the precise or nuanced insights that are crucial in clinical decision-making, underscoring the importance of human oversight and verification when using the tool in a healthcare context.

In light of this current understanding we have attempted to provide GPT with highly structured and comprehensive real world patient data. Several findings are noteworthy in our own current study.

For instance, he relatively high AUC-values in the machine learning validation cohort (higher than the training AUC) indicate that the machine learning model is generalizable and not likely to overfit.

In ourcohort GPT-3.5 outperforms machine learning in terms of accuracy, highlighting the possibility that when provided with full text-data on relevant clinical findings such as physical examination and medical imaging with specific prompts it might be able to better understand the context and generate more relevant responses in comparison to the more traditional machine learning models.

On the other hand, machine learning, albeit being more time consuming to train offers a clearer insight into feature importance, making it better understandable which variables contribute more to the predictions of the model and which features do less.

The results from the machine learning part of analysis are in line with previous findings in literature in the detection of individuals with acute appendicitis [

29,

30,

31,

32].

To our knowledge this is the first ‘intended-use’ for surgical treatment decision study in literature that compares decision making of board-certified surgeons versus GPT- algorithm and machine learning on comprehensive clinical, biochemical and radiological information .

Certainly there are a few limitations to our current study. Limitations of this study include 1) the output of GPT-3.5 is not always straightforward, but is rather an advice or recommendation to consult an external source of data. We have noticed that to achieve more precise responses it is very important to prompt GPT-3.5 to provide the user with a resolute answer, with other words to make a decision despite the uncertainties based on the data that was provided to the algorithm 2) inherent biases, inaccurate results of the LLM-algorithm and the inability of the current GPT-3.5 version to differentiate between reliable and unreliable sources. GPT-3.5 is only trained on content up to September 2021 on a limited amount of online sources, thereby limiting its accuracy on queries related to more recent events. GPT-4 is trained on data up through April 2023 or December 2023 (depending on the model version) and can browse the internet in case it is prompted to do so.

3) significant legal, technological and ethical concerns surrounding the use of ChatGPT in healthcare decision making in general [

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. Improper utilization of this technology could lead to violations of copyright laws, health regulations, and other legal frameworks. For instance, text generated by ChatGPT may include instances of plagiarism and can contribute to the creation of hallucinations- as previously mentioned content produced by the model that is not grounded in reality, often fabricating narratives or data. These issues may arise due to biases in the training data, insufficient information, a limited understanding of real-world contexts, or other inherent algorithmic limitations. It is important to further recognize that ChatGPT is unable to discern the significance of information and can only replicate existing research, lacking the capability to generate novel insights like human scientists. Therefore, a thorough investigation into the ethical implications of ChatGPT is necessary, and there is a pressing need to establish global ethical standards for its use [

34] particularly as a medical chatbot, on an international scale.

While GPT-3.5's role in the decision to perform an appendectomy should in our opinion be as a decision support tool rather than a replacement for clinical judgment, it has the potential to streamline the decision-making process, improve patient outcomes, and reduce the risk of unnecessary surgeries. We acknowledge that decision-making for appendectomy encompasses surgical judgement alongside with patient preference. In cases where fast decisions must be taken under time pressure and uncertainty (i.e high risks for surgical complications, lack of patient cooperation), GPT-3.5 and later versions can be in our opinion a valuable aid in decision-making process.

As with any medical application of AI, it's important to use GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 in conjunction with the expertise of trained healthcare professionals who can make the final decisions based on both the AI's guidance and their clinical judgment [

38].

In our opinion, this study merely serves as a proof of concept and clinical adoption possibilities of the proposed approach to use GPT-3.5 as well as more commonly used supervised machine learning algorithms as a clinical decision support system (CDSS) is still subject to regulatory review and approval (although the FDA and international regulatory authorities have already issued initial guideline documents for the development and approval of machine learning (ML)/artificial intelligence (AI)-based tools) [

39]. Nevertheless, with the advent of newer versions such as GPT-4 that are pre-trained on ever larger amounts of information and that can accept images as input and pull text from web pages when you share a URL in the prompt, but also grant the user the possibility to provide the LLM with additional domain-specific and unbiased information (e.g. retrieval augmented generation (RAG) and fine-tuning) such tools hold potential to improve clinical workflows, resource allocation, as well as cost-effectiveness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Di Saverio, S.; Podda, M.; De Simone, B.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of acute appendicitis: 2020 update of the WSES Jerusalem guidelines. World J Emerg Surg 2020, 15, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sceats, L.A.; Trickey, A.W.; Morris, A.M.; et al. Nonoperative management of uncomplicated appendicitis among privately insured patients. JAMA surgery 2019, 154, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilves, I. Seasonal variations of acute appendicitis and nonspecific abdominal pain in Finland. WJG. 2014, 20, 4037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viniol, A.; Keunecke, C.; Biroga, T.; et al. Studies of the symptom abdominal pain--a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fam Pract. 2014, 31, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhangu, A.; Søreide, K.; Di Saverio, S.; et al. Acute appendicitis: modern understanding of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2015, 386, 1278–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, C.A.; Abu-Zidan, F.M.; Sartelli, M.; et al. Management of Appendicitis Globally Based on Income of Countries (MAGIC) Study. World J Surg. 2018, 42, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, E.H.; Woodward, W.A.; Sarosi, G.A.; et al. Disconnect between incidence of nonperforated and perforated appendicitis: implications for pathophysiology and management. Ann Surg. 2007, 245, 886–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potey, K.; Kandi, A.; Jadhav, S.; Gowda, V. Study of outcomes of perforated appendicitis in adults: a prospective cohort study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2023, 85, 694–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Moris, D.; Paulson, E.K.; Pappas, T.N. Diagnosis and Management of Acute Appendicitis in Adults: A Review. JAMA 2021, 326, 2299–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, A.P.; Talan, D.A.; Moran, G.J.; et al. Evidence for an Antibiotics-First Strategy for Uncomplicated Appendicitis in Adults: A Systematic Review and Gap Analysis. J Am Coll Surg. 2016, 222, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Eriksson, S.; Granstrom, L. Randomized controlled trial of appendicectomy versus antibiotic therapy for acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 1995, 82, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styrud, J.; Eriksson, S.; Nilsson, I.; et al. Appendectomy versus antibiotic treatment in acute appendicitis. a prospective multi-center randomized controlled trial. World J Surg. 2006, 30, 1033–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turhan, A.N.; Kapan, S.; Kutukcu, E.; et al. Comparison of operative and non operative management of acute appendicitis. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2009, 15, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hansson, J.; Korner, U.; Khorram-Manesh, A.; et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotic therapy versus appendicectomy as primary treatment of acute appendicitis in unselected patients. Br J Surg. 2009, 96, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vons, C.; Barry, C.; Maitre, S.; et al. Amoxicillin plus clavulanic acid versus appendicectomy for treatment of acute uncomplicated appendicitis: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011, 377, 1573–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CODA Collaborative. A Randomized Trial Comparing Antibiotics with Appendectomy for Appendicitis (CODA). N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 1907–1919. [CrossRef]

- Ashish Vaswani, et al. Attention is all you need. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. 2017 Syst. 30. [CrossRef]

- Larry, R. Medsker, L.C. Jain. Recurrent neural networks. Des. Appl. 2001, 5, 64–67. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Dada, A.; Puladi, B.; Kleesiek, J.; Egger, J. ChatGPT in healthcare: A taxonomy and systematic review. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2024, 245, 108013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ChatGPT, ver. 3.5; OpenAI: San Francisco, 2023. Available online: https://openai.com/chatgpt (accessed on 22 September 2023).

- Dave, T.; Athaluri, S.A.; Singh, S. ChatGPT in medicine: an overview of its applications, advantages, limitations, future prospects, and ethical considerations. Front Artif Intell. 2023, 6, 1169595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gertz, R.J.; Bunck, A.C.; Lennartz, S.; Dratsch, T.; Iuga, A.I.; Maintz, D.; Kottlors, J. GPT-4 for Automated Determination of Radiological Study and Protocol based on Radiology Request Forms: A Feasibility Study. Radiology, 2023, 307, e230877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottlors, J.; Bratke, G.; Rauen, P.; Kabbasch, C.; Persigehl, T.; Schlamann, M.; Lennartz, S. Feasibility of Differential Diagnosis Based on Imaging Patterns Using a Large Language Model. Radiology 2023, 308, e231167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Berg, Hidde, et al. "ChatGPT and Generating a Differential Diagnosis Early in an Emergency Department Presentation." Annals of Emergency Medicine (2023). [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Gui, X. Self-diagnosis through ai-enabled chatbot-based symptom checkers: user experiences and design considerations. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2020, 1354–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrael, G.; Sahu, K.K.; Chigarira, B.; et al. Enhancing Triage Efficiency and Accuracy in Emergency Rooms for Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer: a Retrospective Analysis of Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Triage Using ChatGPT 4.0. Cancers. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palenzuela, D.L.; Mullen, J.T.; Phitayakorn, R. AI Versus MD: Evaluating the surgical decision-making accuracy of ChatGPT-4. Surgery. 2024, 176, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 28. Beaulieu-Jones BR, Shah S, Berrigan MT et al. Evaluating Capabilities of Large Language Models: Performance of GPT4 on Surgical Knowledge Assessments. medRxiv [Preprint]. 2023 Jul 24:2023.07.16.23292743. doi: 10.1101/2023.07.16.23292743. Update in: Surgery. 2024 Apr;175(4):936-942. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2023.12.014. PMID: 37502981; PMCID: PMC10371188. [CrossRef]

- Phan-Mai, T.A.; Thai, T.T.; Mai, T.Q.; Vu, K.A.; Mai, C.C.; Nguyen, D.A. Validity of Machine Learning in Detecting Complicated Appendicitis in a Resource-Limited Setting: Findings from Vietnam. BioMed research international 2023, 5013812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcinkevics, R.; Reis Wolfertstetter, P.; Wellmann, S.; Knorr, C.; Vogt, J.E. Using Machine Learning to Predict the Diagnosis, Management and Severity of Pediatric Appendicitis. Frontiers in pediatrics 2021, 9, 662183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijwil, M.M.; Aggarwal, K. A diagnostic testing for people with appendicitis using machine learning techniques. Multimedia tools and applications 2022, 81, 7011–7023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, S.; Yagin, F.H.; Cicek, I.B.; Koc, C.; Colak, C.; Yilmaz, S. Prediction of Perforated and Nonperforated Acute Appendicitis Using Machine Learning-Based Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland), 2023, 13, 1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; He, D. The Potential Applications and Challenges of ChatGPT in the Medical Field. Int J Gen Med. 2024, 17, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bernd Carsten Stahl, Damian Eke. The ethics of ChatGPT – Exploring the ethical issues of an emerging technology. International Journal of Information Management; 2024, 74, 102700. [CrossRef]

- Guleria, A.; Krishan, K.; Sharma, V.; Kanchan, T. ChatGPT: ethical concerns and challenges in academics and research. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2023, 17, 1292–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emsley, R. ChatGPT: these are not hallucinations – they’re fabrications and falsifications. Schizophr 2023, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelli, M.; Descamps, J.; Lavoué, V.; et al. Hallucination Rates and Reference Accuracy of ChatGPT and Bard for Systematic Reviews: Comparative Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, e53164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, Nicolas T. Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie essentials (2017). ; pp 172. [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, C.; Baumgartner, D. A regulatory challenge for natural language processing (NLP)-based tools such as ChatGPT to be legally used for healthcare decisions. Where are we now?. Clinical and translational medicine 2023, 13, e1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).