1. Introduction

The landscape of clinical decision-making is undergoing a profound transformation with the stepwise integration of cutting-edge technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI) and Digital Twins (DT). In specialities such as hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery, these innovations hold immense potential to reshape patient care. AI-based clinical decision support systems (CDSS), for instance, are demonstrating the capability to improve diagnostic accuracy and optimise treatment pathways significantly (Ouanes and Farhah 2024). Concurrently, Digital Twins offer a revolutionary approach by providing personalised computational models that can simulate individual patient physiology. This enables highly individualised treatment planning, supports intricate surgical decision-making, and enhances the prediction of disease progression, thereby ushering in a new era of precision medicine (Björnsson et al. 2019).

However, despite the compelling promise of AI and Digital Twins to advance various facets of medical practice, their widespread adoption and comprehensive impact on real-world clinical workflows remain areas of significant uncertainty. As these technologies become more advanced, critical questions emerge regarding the autonomy clinicians maintain when using such tools, the optimal methods for incorporating patient preferences into AI-assisted decisions, and the crucial matter of accountability for potential errors (Iqbal et al. 2025). Consequently, there is an urgent need to reevaluate and update existing regulatory frameworks, as well as to increase awareness among healthcare professionals regarding their rights and the corresponding education necessary to ensure safe and practical integration. Taking together these challenges results in a gap between the development of AI and DT solutions and their implementation in medical practice (Kamel Rahimi et al. 2024).

To address this gap, it is essential to necessitate a deeper understanding of how healthcare professionals interact with these technologies in practice, as well as their overall attitude towards them. For example, in 2022, Elsevier launched the “Clinician of the Future” series to gather clinicians’ opinions, needs, and concerns about emerging medical trends (Lucy Goodchild et al. 2022). One issue specifically focused on “Clinician of the Future: Attitudes toward AI”, in response to the growing use of artificial intelligence in healthcare (Lucy Goodchild et al. 2024). Along with other articles, this series highlights the growth of interest in practical AI applications, the challenges of adoption, and the specific areas of medical care where this technology is most needed (Chew and Achananuparp 2022; Hua et al. 2024; Wysocki et al. 2023).

Digital Twins have started to be widely used in precision medicine (Armeni et al. 2022). This technology enables personalised dynamic predictions, with the possibility of updates as new patient information becomes available (Katsoulakis et al. 2024). Currently, there is a lack of information regarding clinicians’ opinions and attitudes on Digital Twins, which makes it difficult to address the specific challenges while integrating Digital Twins in healthcare.

Going further, the diversity of the medical field implies the possibility of not a general solution, but a group of individual solutions for separate specialities. For instance, developers of AI systems for medical fields, which aim to facilitate closer patient-doctor interactions, should prioritise incorporating patient preferences into the system’s recommendations. On the other hand, systems used in emergency medicine require speed and should provide clear and concise output information as one of the first priorities (Popa et al. 2024). The following can also be extrapolated to Digital Twins.

Against this background, this study aims to comprehensively examine clinicians’ perceptions of AI and Digital Twins within the specific context of hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery. By exploring these perspectives, we seek to provide valuable insights into the potential benefits, existing limitations, and the critical ethical implications associated with their use. Specifically, this research compares AI and Digital Twins and investigates clinical decision support tools based on them in three key areas: (1) the familiarity with the concepts, and the perceived extent to which these technologies should assist or automate clinical decision-making in hepatology; (2) impact on physician autonomy and patient involvement in shared decision-making; and (3) the identified challenges, practical limitations, and essential regulatory requirements for the safe and effective integration into clinical practice.

2. Results

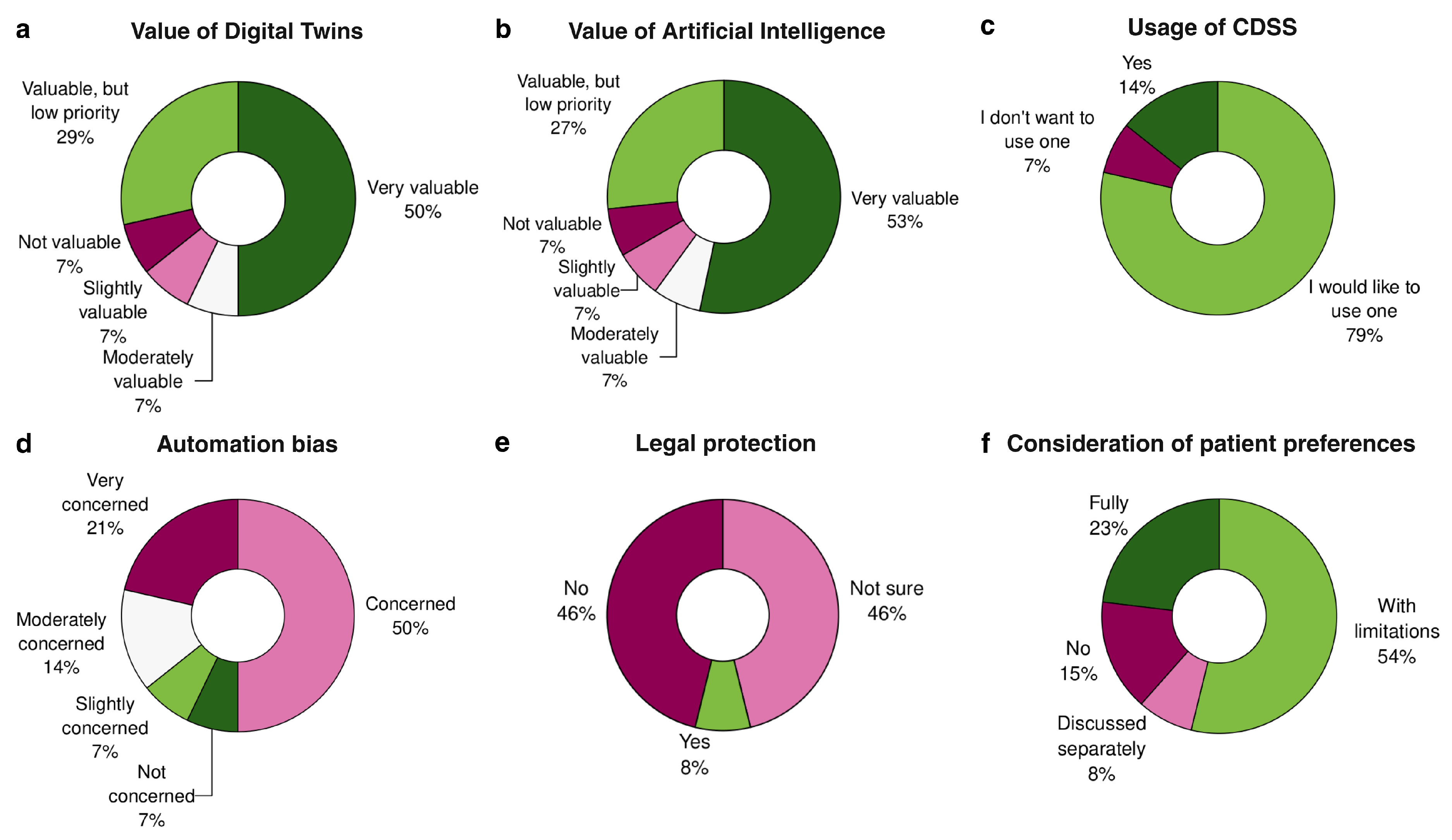

To provide context for the detailed results below, we begin with a brief summary of the main findings (

Figure 1). Overall, clinicians expressed a positive attitude toward the integration of Digital Twins (DT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) into hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: High perceived value: 79% of respondents consider Digital Twins to be valuable or very valuable, and 80% rate AI similarly (

Figure 1a,b). Growing adoption of decision support tools: 93% of participants already use or intend to use a clinical decision support system (CDSS) (

Figure 1c). Concerns about automation bias: 71% of respondents are concerned or very concerned about overreliance on algorithmic recommendations (

Figure 1d). Legal uncertainty: A striking 92% are uncertain about their legal protection when using AI- and DT-based tools. Patient-centred care: 77% support including patient preferences when integrating AI and DT into clinical decision-making (

Figure 1e). These findings highlight both the enthusiasm for technological innovation and the caution around potential risks, especially regarding liability and automation bias. The following sections provide a more detailed examination of these results.

2.1. Demographics

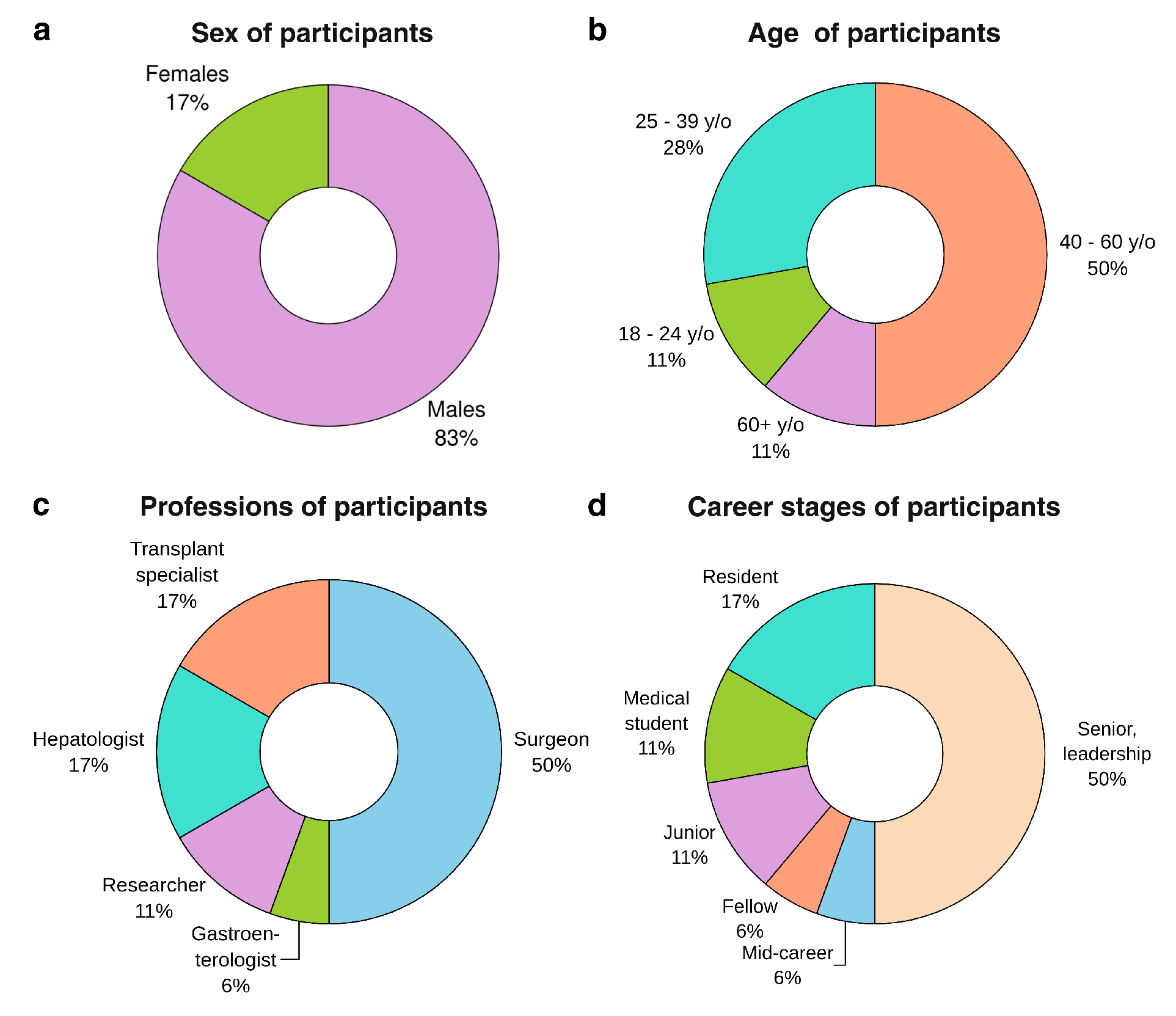

Demographic characteristics of the questionnaire respondents are reported in

Figure 2. The majority of participants identified as male (83%), with the remaining respondents identifying as female. The age distribution was relatively broad, with a concentration in mid-career stages: 11% of respondents were between 18 and 24 years old, 28% were between 25 and 39 years old, 50% fell within the 40–60 age range, and the remainder were over 60 years old. In terms of professional background, half of the sample were surgeons, while hepatologists and transplant specialists each accounted for 17%. Smaller proportions of respondents were researchers (11%), and the remaining were gastroenterologists. The career stage was similarly diverse, although skewed toward more experienced individuals: 50% reported holding senior or leadership positions, while 6% were at the mid-career level. Among trainees, 17% were residents, 6% were fellows, 11% were junior doctors, and an additional 11% comprised medical students.

2.2. AI and Digital Twins in Clinical Decision Making

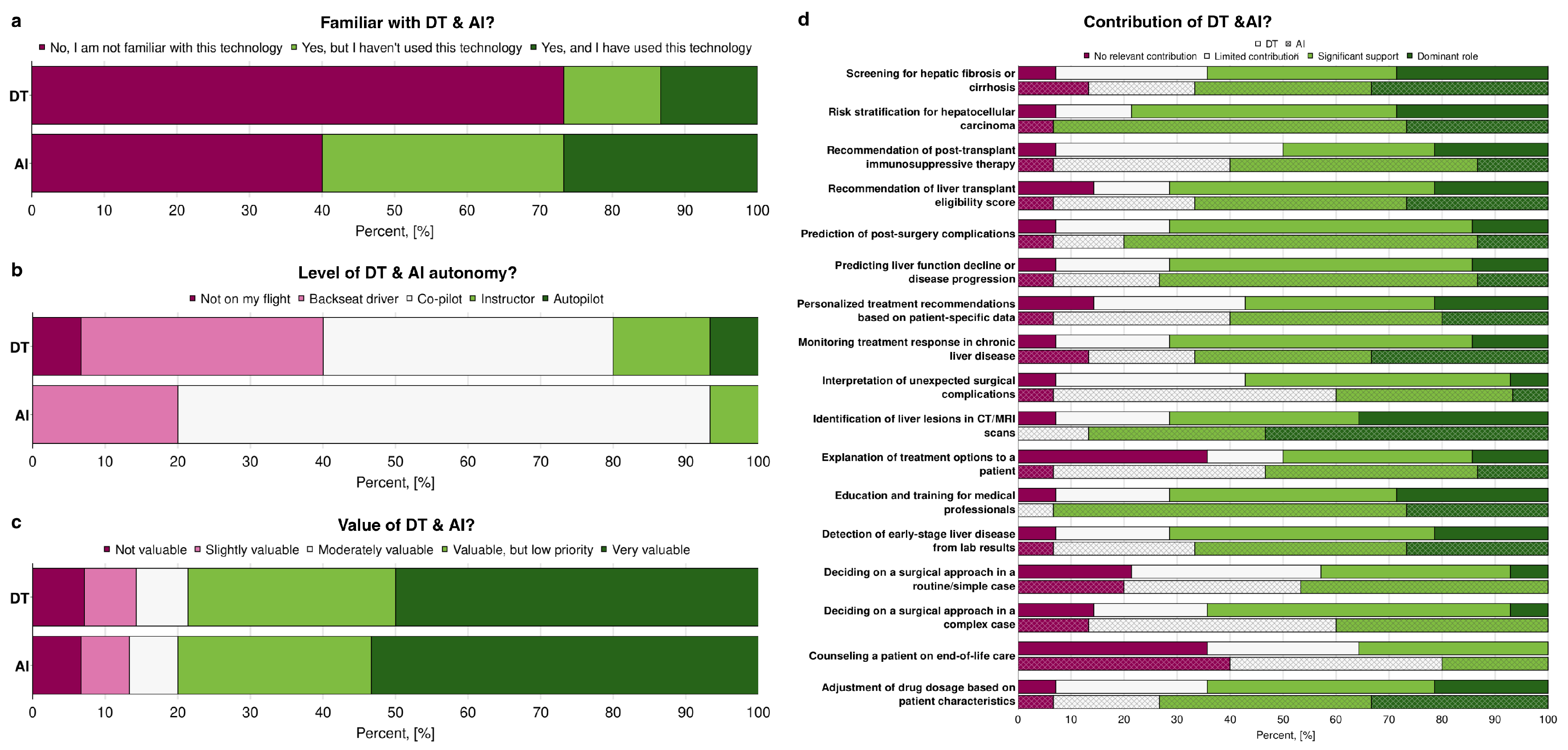

Figure 3 illustrates the respondents’ familiarity with AI and Digital Twins, their perception of the level of autonomy, and their assessment of the value of these technologies in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery. Overall, familiarity was higher for AI than for DT (

Figure 3a). While a majority of subjects reported at least some familiarity with AI (60%), only 27% of responders were familiar with the concept of Digital Twins. AI was often cited as a tool that is well known but not yet applied in clinical practice (33%). Despite DT being unknown to the majority (73%), 13% of participants reported using them in their professional work. Respondents were asked to evaluate whether both AI and DT can be applied in medical practice and their level of autonomy by using the metaphor of a flight. They could choose between multiple options, such as:

“Not on my flight”: The participant prefers to rely solely on their expertise.

“Backseat driver”: AI & Digital Twins can provide recommendations, but the participant does not always trust them.

“Co-pilot”: AI & Digital Twins can assist, but the participant remains in complete control.

“Instructor”: AI & Digital Twins can guide the participant and shape their decision-making.

“Autopilot”: The participant trusts AI & Digital Twins to make decisions, but can override them if needed.

When faced with this question, most respondents chose intermediate levels, such as “co-pilot”, “instructor” or “backseat driver”, rather than the more extreme options. When comparing the diversity of answers, participants showed higher agreement for AI. In contrast, for the DT, a wider range of answers was shown (

Figure 3b). When comparing the answers of participants who were not familiar with AI or DT and the level of autonomy they think the corresponding technologies can have, DT also showed a higher diversity of answers, starting from “not on my flight” to “autopilot”, while for AI two options were chosen: “backseat driver” and “co-pilot” (data not shown).In terms of value, AI was consistently rated more highly than DT, with a larger share of respondents describing it as “very valuable” (53%). At the same time, DT received more mixed assessments, ranging from “slightly valuable” to “moderately valuable” (

Figure 3c).

To identify which particular tasks clinicians can wholly or partly delegate to AI or Digital Twins, and which tasks they cannot, participants were given a list of tasks. They were asked to categorise each task as to whether AI or Digital Twins can play a dominant role in it, provide significant or limited support, or make no relevant contribution (

Figure 3d). For most tasks, respondents saw a clear contribution from AI and DT. From them, the identification of liver lesions in CT/MRI was considered the most prominent task to be automated using AI and DT. The only apparent difference was the ability of AI and Digital Twins to contribute to tasks related to communication with patients (such as explaining treatment options and counselling a patient on end-of-life care) and to decision-making in hepatobiliary surgery (including deciding on the surgical approach), where the majority agreed that these technologies would offer no meaningful support. Overall, participants considered AI to have a higher contribution potential in the listed tasks than Digital Twins. Exceptions included tasks such as interpreting unexpected surgical complications and determining the appropriate surgical approach in complex cases.

2.3. Role of Clinical Decision Support Systems

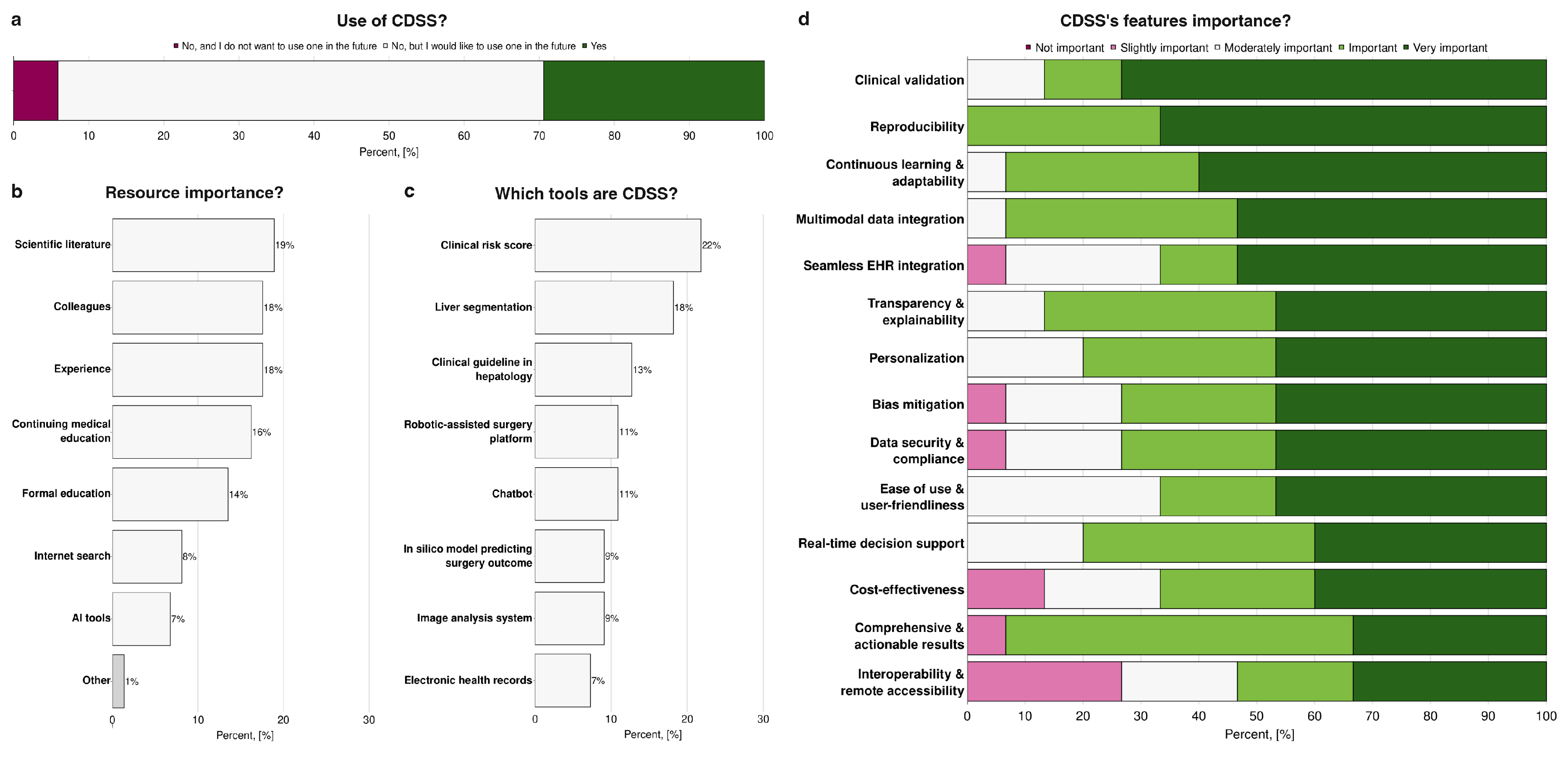

When asked about the use of CDSS, as reported in

Figure 4a, 29% of participants reported actively using such systems. Of them, 60% of responders specified the particular CDSS they use (UpToDate, LiverTox, MEVIS, Eurotransplant Donor Risk Index - ET-DRI). At the same time, the majority indicated that they do not currently use CDSS but would be interested in adopting them in the future (65%). A minority reported that they neither use nor have an interest in using CDSS. In terms of resources guiding clinical decision-making, traditional sources remained predominant: scientific literature, consultation with colleagues, and personal clinical experience were consistently rated as the most important, whereas AI-based tools were considerably less influential, with only 7% of participants considering them a key resource (

Figure 4b). One participant mentioned a specific medical decision support tool as an essential tool in their clinical practice (“Other” on

Figure 4b). To assess familiarity with CDSS, respondents were asked to identify tools that they would classify as part of this category (

Figure 4c). Clinical risk scores were the most frequently identified as CDSS (22%), followed by liver segmentation tools (18%), clinical guidelines in hepatology (13%), robotic-assisted surgery platforms (11%), chatbots (11%), in silico models predicting surgical outcomes (9%), image analysis systems (9%), and electronic health records (7%). Regarding the features considered most important in such systems, participants emphasised clinical validation, reproducibility, and the capacity for continuous learning and adaptability, indicating a preference for tools that are both reliable and capable of evolving with new evidence. Conversely, interoperability with other systems and remote accessibility were consistently ranked as less critical, suggesting that practical integration and accessibility outside the immediate clinical environment are not primary concerns compared to accuracy, reliability, and adaptability of the system itself (

Figure 4d).

2.4. Challenges and Conflicts

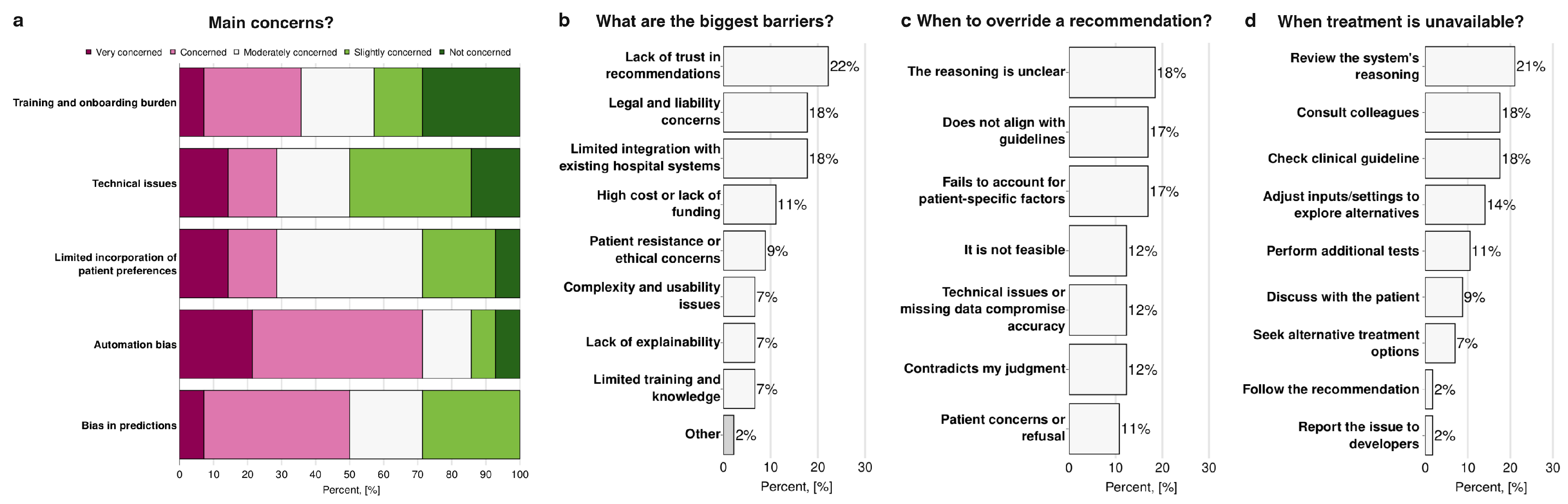

Participants identified several key challenges and conflicts associated with the use of AI and Digital Twins in the field of hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery. When evaluating participants’ main concerns about the use of AI and Digital Twins (

Figure 5a), automation bias was associated with the highest levels of worry (71%). In contrast, training and onboarding burden, as well as technical issues, were associated with the lowest levels of concern (43% and 50% respectively). When asked about the most significant barriers to implementation (

Figure 5b), the most frequently reported were lack of trust in system recommendations (22%), legal and liability concerns (18%), and limited integration with existing hospital operating systems (18%). In contrast, issues such as complexity and usability, lack of explainability, and limited training or knowledge were less frequently cited (7%). One participant specified a specific hepatology issue (“Other” on

Figure 5b): the complexity of the clinical management of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Regarding situations in which participants would override AI or Digital Twins recommendations (

Figure 5c), the most common triggers were unclear reasoning by the system (18%), misalignment with clinical guidelines (17%), and failure to account for patient-specific factors (17%). In contrast, patient concerns or refusal were less often reported as reasons for override (11%).

Figure 5d shows the responses that participants report they would have if the treatment suggested by AI were unavailable: 21% indicated they would review the system’s reasoning, 18% would consult colleagues and refer to clinical guidelines. In comparison, only a very small minority (2%) would either follow the recommendation despite unavailability or report the issue to developers.

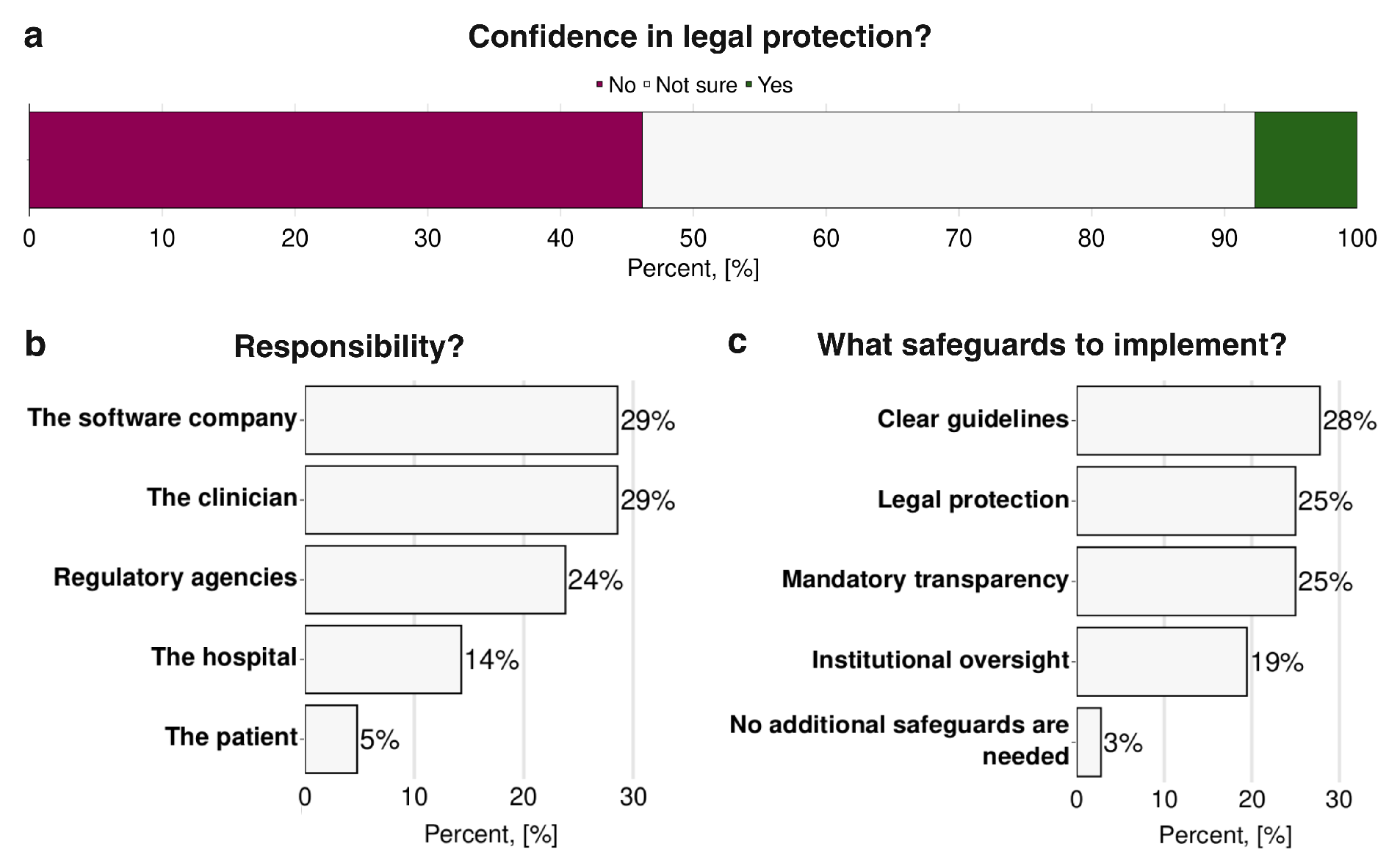

2.5. Liability Issues

Respondents’ concerns regarding liability in the use of AI and Digital Twins are shown in

Figure 6. When asked whether they felt confident in the current legal protections available for the use of such technologies, nearly half of the respondents (46%) indicated that they were not confident. In comparison, only a small minority (8%) expressed confidence and the remainder were uncertain (

Figure 6a). When asked who should ultimately be liable for errors or adverse outcomes related to AI or Digital Twins recommendations, participants ranked software companies and clinicians as the primary responsible parties (29%) followed by the regulatory agencies (24%), hospitals (14%), and finally patients (5%) (

Figure 6b). In terms of safeguards to mitigate these legal and ethical concerns (

Figure 6c), respondents most frequently asked for clear guidelines (28%), legal protection (25%), and mandatory transparency regarding system function and recommendations (25%). Institutional oversight was also considered necessary by a substantial proportion (19%), while only 3% felt that no additional safeguards were necessary.

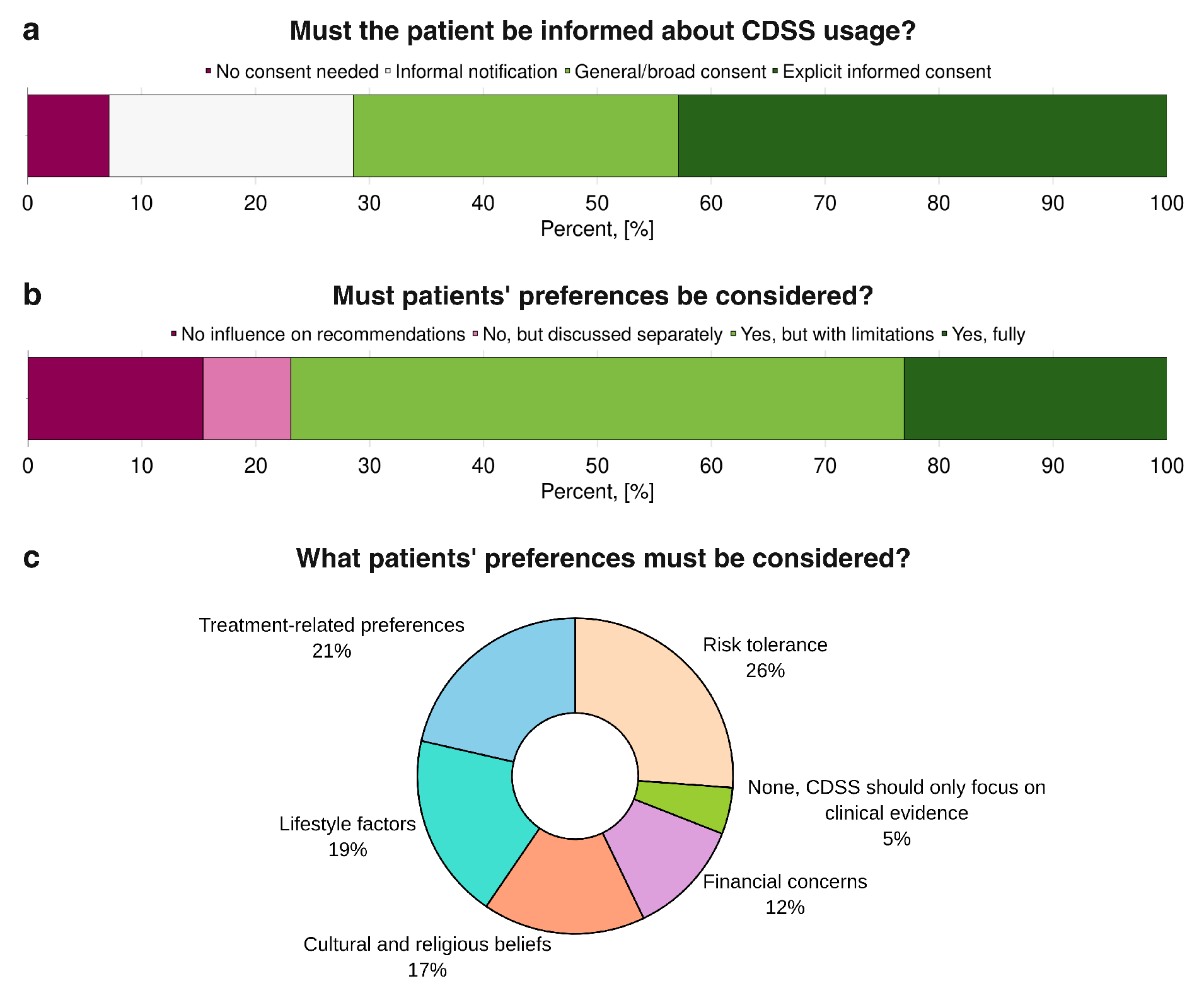

2.6. Patient Preferences

Patient preferences in relation to the use of CDSS and AI-based tools are illustrated in

Figure 7. When asked whether patients should be informed about the use of CDSS in their care (

Figure 7a), a clear majority supported some form of disclosure: 43% favored explicit informed consent, 29% endorsed a general or broad consent, and a smaller proportion preferred informal notification, whereas only 7% believed no consent was necessary. Regarding whether patient preferences should be considered in clinical decisions supported by AI or Digital Twins (

Figure 7b), most respondents agreed, with 23% advocating full integration of patient preferences and the majority of the remainder supporting partial consideration; only 15% entirely rejected their inclusion, and 8% argued that preferences should be addressed separately from the AI or DT-supported clinical decision process. When asked which specific patient preferences should be prioritised (

Figure 7c), the highest-ranked was tolerance of risk (26%), followed by treatment-related preferences (21%) and lifestyle factors (19%). Cultural and religious beliefs (17%) and financial concerns (12%) were also considered necessary, while only a very small minority (5%) believed no patient preferences needed to be considered.

3. Methods

3.1. Survey Development

The questionnaire was developed to explore clinicians’ perceptions of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery. The development process involved several steps to ensure its relevance, clarity, and effectiveness in capturing nuanced perspectives.

Initially, a rapid literature review was conducted to identify existing frameworks and examples of surveys on AI and technology adoption in healthcare. Particular inspiration was drawn from the methodologies and topical coverage of studies by Cobianchi et al. (2023); Oh et al. (2019); van Hoek et al. (2019). This foundational review helped define the core thematic areas critical to understanding clinician perspectives, including familiarity with and current use of AI methods and Digital Twins, their perceived role in clinical decision-making, associated challenges, the incorporation of patient preferences, and perceptions of professional liability.

The interdisciplinary expertise within our research team was instrumental in refining the scope and phrasing of the questions. The questionnaire was designed with the primary aim of eliciting responses based on realistic clinical scenarios, prompting participants to consider potential situations and their reactions. Emphasising clarity and ease of response, questions were formulated to be concise, primarily utilising closed-ended formats to facilitate quantitative analysis. Care was taken to ensure that respondents felt empowered to express their genuine perspectives, avoiding leading language that might bias answers.

A preliminary draft of the questionnaire, comprising 22 questions, was then developed. This draft included five questions for demographic information, four questions specifically on AI methods, four questions on Digital Twins, six questions addressing involvement in clinical decision-making, four questions on perceived challenges, three questions concerning patient preferences, and three questions related to liability. This initial version was subjected to an internal review by a more general public, including individuals experienced in survey design and response, as well as medical professionals from diverse backgrounds (not exclusively hepatology). The feedback gathered during this phase focused on aspects such as questionnaire length, the understandability of the language, and the overall flow.

The final survey consisted of 8 sections:

Demographics (n=5). This section collected basic information about participants’ professional background, career stage, and role in hepatology or hepatobiliary surgery. The responses helped us understand the diversity of participants in the study.

Usage of clinical decision support systems (n=4). This section examined participants’ familiarity with and use of AI- and Digital Twins-based clinical decision support systems in hepatology and liver surgery. It aimed to understand how CDSS assist in clinical decision-making.

Artificial Intelligence methods in hepatology (n=4). This section collected insights into participants’ familiarity with AI methods and their role in their clinical practice.

Digital Twins of the liver (n=4). This section explored participants’ familiarity with the concept of Digital Twins and their potential applications in clinical decision-making.

Challenges & Conflicts (n=4). This section examined the difficulties and conflicts that arise when using AI and Digital Twins in clinical practice, including issues related to trust, reliability, and conflicts in decision-making.

Patient preferences (n=3). This section explored how AI- and Digital Twins-based decision systems should incorporate patient preferences and whether patients should be informed about their use.

Liability issues (n=3). This section addresses the responsibility and legal protection associated with AI- and Digital Twin-Based decisions that influence patient outcomes.

Feedback (n=1). This section aims to improve future research on AI and Digital Twins in hepatology and liver surgery.

The survey is available in Myshkina et al. (2025).

Considering the potential low awareness of the “Digital Twins” concept, we assessed participants’ familiarity with it and subsequently defined the concept of “Digital Twins”. Considering the “question-by-question” form of the survey, we assume it has a minimal impact on the previous familiarity question.

The questionnaire was then implemented and distributed online using

LimeSurvey, a GDPR-certified survey tool provided by Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. The survey itself and participants’ answers were stored in the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin’s central database for six months.

3.2. Participants’ Consent

Participants were aware of the types of data collected and the intended use.

3.3. Data Anonymisation

The following settings in LimeSurvey were used to ensure the maintenance of participants’ privacy and the anonymity of their responses; no personally identifiable information was stored, including participants’ IP addresses. An identification number was assigned for every participant using the LimeSurvey encryption service. After the survey was completed, it was permanently deleted from Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin’s database, along with the answers.

3.4. Data Analysis & Visualisation

The final results were exported from the LimeSurvey platform in table format. The analysis was conducted using Python 3.13, pandas, plotly, kaleido, and dash to process, analyse, and visualise the survey results. To ensure the accessibility of the plots, the

“Regenbogen” colour palette tool was used for selecting colours for the visualisations.

4. Discussion

The findings of this survey highlight both enthusiasm and caution among hepatobiliary professionals regarding the integration of AI and Digital Twins into clinical practice. Participants reported greater familiarity with AI compared to DT, which likely explains why AI was perceived as more valuable and assigned clearer roles in clinical workflows. In contrast, Digital Twins remain less well understood and will most likely face additional hurdles before they can be fully adopted.

The current use of CDSS was reported as low. Still, many participants expressed openness to adopting them in the future, suggesting that the lack of current use might stem more from existing barriers rather than outright resistance. In line with this, most clinicians continue to rely primarily on traditional decision-making resources, such as scientific literature, conversations with colleagues, and clinical experience. At the same time, AI tools were ranked much lower in importance. Interestingly, when asked to classify CDSS tools or name the CDSS tools they use, respondents frequently misattributed items such as clinical guidelines, clinical risk scores or robotic platforms, indicating a lack of clarity about what constitutes a CDSS and highlighting an urgent need for standardised definitions and training. When evaluating desired features of CDSS, respondents consistently prioritised clinical validation, reproducibility, and adaptability over more technical considerations such as interoperability or remote access, indicating that perceived reliability and evidence-based performance are valued above convenience.

The main barriers to adoption cited by the participants were a lack of trust in recommendations, liability concerns, and limited integration into existing hospital systems. In contrast, automation bias emerged as a greater concern than usability or training. This emphasises a strong assumption of responsibility by the respondents, who are not so worried by usability challenges that can be overcome through training, but rather by potentially damaging features that are inherently tied to the system’s design, such as automation bias. Clinicians can indeed learn to operate a new tool, but they cannot independently verify whether the underlying model is biased, making it a source of uncertainty and an issue that needs to be addressed to promote the integration of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twin-based tools into clinical workflows. In practice, participants indicated that they would override AI-generated recommendations if the reasoning was unclear, if guidance conflicted with established guidelines, or if patient-specific factors were not adequately considered. highlighting that clinicians view AI as a supportive tool, rather than a replacement for professional judgment. Consistent with this perspective, participants chose the task “Identification of liver lesions in CT/MRI” as the most prominent task to be automated using AI and DT. This choice not only underscores the supportive role of these techniques, as recognised by participants, but also reflects the growing integration of AI in medical image analysis that is already occurring today (Bajwa et al. 2021).

Liability and regulatory issues emerged as another major area of concern, with nearly half of respondents expressing a lack of confidence in existing legal protections. This concern can be directly linked to automation bias, as incorrect recommendations by an algorithm could expose clinicians to legal risk. In this context, the recent European Union AI Act is particularly significant, as it represents the first comprehensive attempt to regulate the use of Artificial Intelligence across multiple fields, including clinical and research settings (European Union Artificial Intelligence Act 2024). Under the Act, most medical systems cited in the survey, including CDSS and DT, are expected to fall into the category of “high risk” applications, bringing with it strict requirements on transparency, traceability, and human oversight of the algorithms. The AI Act also introduced a clearer framework surrounding liability that still leaves some open questions on how it will be shared between software manufacturers; healthcare institutions and the individual physicians, but nevertheless it attempts to ensure that the responsibility does not fall disproportionately on the clinician should unexpected or adverse outcomes arise from a decision assisted with AI (van Kolfschooten and van Oirschot 2024). The respondents’ limited confidence in legal protection may reflect a general lack of awareness about the existence and implications of this regulation. With the Act having entered into force in August 2024 and still being phased in, it is entirely possible that many clinicians may not yet be familiar with its implications in their field.

In terms of responsibility for eventual errors made by the software, most attributed the biggest impact to software companies. However, the roles of clinicians, regulators, and hospitals were still recognised, showing that they have a clear understanding of the main actors at play in delicate situations that can arise when incorporating AI or DT into the clinical workflow. It is interesting to note that most participants did not indicate contacting the developers as a main response in the case of unrealistic recommendations. This highlights the absence of a direct feedback channel and a lack of communication that could reinforce the idea that clinicians bear the liability and the burden of managing the system without being backed by the developers. Consistent with this, respondents expressed a strong demand for safeguards such as clear guidelines, legal protection, transparency, and institutional oversight, while very few believe that no additional measures are necessary.

Patient involvement was also considered essential: the majority of respondents favoured informing patients about CDSS use, with explicit informed consent being the most popular option. However, some subjects indicated that an informal notification might be sufficient in some cases. This opens the question of how much detail is necessary to avoid overwhelming patients and how to reach the right balance between transparency and practicality in clinical communication. Most agreed that patient preferences should be integrated into AI-supported decision-making, particularly with respect to risk tolerance, treatment-related preferences, and lifestyle factors. This aligns with the broader movement toward personalised medicine but also highlights the challenge of operationalising such preferences in AI-driven workflows. Our findings suggest that professionals in the hepatobiliary field are cautiously optimistic about the potential of AI and DT. However, their widespread adoption will depend on whether certain key issues are addressed, notably those of validation, trust, legal clarity, and patient-centred integration. The survey also highlighted the importance of education to bridge the familiarity gap with certain technologies, particularly those connected to CDSS and DT.

The modest sample size is the primary limitation of this study, indicating that the findings should be interpreted as exploratory yet nonetheless valuable in guiding future research and implementation efforts. Another potential source of bias is the likelihood that clinicians already interested in AI might have been more inclined to respond.

5. Conclusions

Clinicians demonstrate a strong interest in adopting AI and DT, but remain cautious due to concerns over trust, liability, and regulatory gaps. Clear guidelines, clinical validation, and patient-centred approaches are essential for safe and effective integration into hepatology practice.

Author Contributions

Design and distribution of the survey, M.M., E.C., A.S., H-M.T., M.K.; implementation of the survey, M.M., E.C.; formal analysis of its results, M.M., E.C., M.K.; visualisation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M., E.C., M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.M., E.C., A.S, H-M.T., T.R., M.K.; supervision, M.K.; project administration, M.M., E.C., M.K.; funding acquisition, H-M.T, T.R., M.K.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

MM and MK were supported by the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) within AI and Simulation for Tumor Liver Assessment (ATLAS) by grant number 031L0304B, AS and HMT by grant number 031L0304C, TR by grant number 031L0304A. MK, TR, and HMT were supported by the German Research Foundation (DFG) within the Research Unit Program FOR 5151 “QuaLiPerF (Quantifying Liver Perfusion-Function Relationship in Complex Resection - A Systems Medicine Approach)” by grant number 436883643 and by grant number 465194077 (Priority Programme SPP 2311, Subproject SimLivA). EC was supported by the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree (EMJMD) program Be in Precision Medicine.

Data Availability Statement

The survey is available in Myshkina et al. (2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Armeni, Patrizio, Irem Polat, Leonardo Maria De Rossi, Lorenzo Diaferia, Severino Meregalli, and Anna Gatti. 2022, July. Digital Twins in Healthcare: Is It the Beginning of a New Era of Evidence-Based Medicine? A Critical Review. Journal of Personalized Medicine 12(8), 1255. [CrossRef]

- Bajwa, Junaid, Usman Munir, Aditya Nori, and Bryan Williams. 2021, July. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: Transforming the practice of medicine. Future Healthcare Journal 8(2), e188–e194. [CrossRef]

- Björnsson, Bergthor, Carl Borrebaeck, Nils Elander, Thomas Gasslander, Danuta R. Gawel, Mika Gustafsson, Rebecka Jörnsten, Eun Jung Lee, Xinxiu Li, Sandra Lilja, David Martínez-Enguita, Andreas Matussek, Per Sandström, Samuel Schäfer, Margaretha Stenmarker, X. F. Sun, Oleg Sysoev, Huan Zhang, Mikael Benson, and Swedish Digital Twin Consortium. 2019, December. Digital twins to personalize medicine. Genome Medicine 12(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Chew, Han Shi Jocelyn and Palakorn Achananuparp. 2022, January. Perceptions and Needs of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care to Increase Adoption: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 24(1), e32939. [CrossRef]

- Cobianchi, Lorenzo, Daniele Piccolo, Francesca Dal Mas, Vanni Agnoletti, Luca Ansaloni, Jeremy Balch, Walter Biffl, Giovanni Butturini, Fausto Catena, Federico Coccolini, Stefano Denicolai, Belinda De Simone, Isabella Frigerio, Paola Fugazzola, Gianluigi Marseglia, Giuseppe Roberto Marseglia, Jacopo Martellucci, Mirko Modenese, Pietro Previtali, Federico Ruta, Alessandro Venturi, Haytham M. Kaafarani, Tyler J. Loftus, and Team Dynamics Study Group. 2023, January. Surgeons’ perspectives on artificial intelligence to support clinical decision-making in trauma and emergency contexts: Results from an international survey. World journal of emergency surgery: WJES 18(1), 1. [CrossRef]

- European Union Artificial Intelligence Act. 2024, June. Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations (EC) No 300/2008, (EU) No 167/2013, (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1139 and (EU) 2019/2144 and Directives 2014/90/EU, (EU) 2016/797 and (EU) 2020/1828 (Artificial Intelligence Act).

- Hua, David, Neysa Petrina, Noel Young, Jin-Gun Cho, and Simon K. Poon. 2024, January. Understanding the factors influencing acceptability of AI in medical imaging domains among healthcare professionals: A scoping review. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 147, 102698. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Usman, Afifa Tanweer, Annisa Ristya Rahmanti, David Greenfield, Leon Tsung-Ju Lee, and Yu-Chuan Jack Li. 2025, May. Impact of large language model (ChatGPT) in healthcare: An umbrella review and evidence synthesis. Journal of Biomedical Science 32, 45. [CrossRef]

- Kamel Rahimi, Amir, Oliver Pienaar, Moji Ghadimi, Oliver J Canfell, Jason D Pole, Sally Shrapnel, Anton H van der Vegt, and Clair Sullivan. 2024, August. Implementing AI in Hospitals to Achieve a Learning Health System: Systematic Review of Current Enablers and Barriers. Journal of Medical Internet Research 26, e49655. [CrossRef]

- Katsoulakis, Evangelia, Qi Wang, Huanmei Wu, Leili Shahriyari, Richard Fletcher, Jinwei Liu, Luke Achenie, Hongfang Liu, Pamela Jackson, Ying Xiao, Tanveer Syeda-Mahmood, Richard Tuli, and Jun Deng. 2024, March. Digital twins for health: A scoping review. npj Digital Medicine 7(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Lucy Goodchild, Elizabeth Shearing Green, Terri Mueller, and Adrian Mulligan. 2022. Clinician of the Future: A 2022 report. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/connect/clinician-of-the-future.

- Lucy Goodchild, María Aguilar Calero, Nicola Mansell, and Adrian Mulligan. 2024. Insights 2024 | Attitudes toward AI | Elsevier. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/insights/attitudes-toward-ai.

- Myshkina, Mariia, Elisabetta Casabianca, Anton Schnurpel, Hans-Michael Tautenhahn, and Matthias König. 2025, March. Questionnaire: Assessing the Impact of AI and Digital Twins on Clinical Decision-Making in Hepatology and Hepatobiliary Surgery. [CrossRef]

- Oh, Songhee, Jae Heon Kim, Sung-Woo Choi, Hee Jeong Lee, Jungrak Hong, and Soon Hyo Kwon. 2019, March. Physician Confidence in Artificial Intelligence: An Online Mobile Survey. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21(3), e12422. [CrossRef]

- Ouanes, Khaled and Nesren Farhah. 2024, August. Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Clinical Decision Support Systems and Care Delivery. Journal of Medical Systems 48(1), 74. [CrossRef]

- Popa, Stefan Lucian, Abdulrahman Ismaiel, Vlad Dumitru Brata, Daria Claudia Turtoi, Maria Barsan, Zoltan Czako, Cristina Pop, Lucian Muresan, Mihaela Fadgyas Stanculete, and Dinu Iuliu Dumitrascu. 2024. Artificial Intelligence and medical specialties: Support or substitution? Medicine and Pharmacy Reports 97(4), 409–418. [CrossRef]

- van Hoek, Jasper, Adrian Huber, Alexander Leichtle, Kirsi Härmä, Daniella Hilt, Hendrik von Tengg-Kobligk, Johannes Heverhagen, and Alexander Poellinger. 2019, December. A survey on the future of radiology among radiologists, medical students and surgeons: Students and surgeons tend to be more skeptical about artificial intelligence and radiologists may fear that other disciplines take over. European Journal of Radiology 121, 108742. [CrossRef]

- van Kolfschooten, Hannah and Janneke van Oirschot. 2024, November. The EU Artificial Intelligence Act (2024): Implications for healthcare. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 149, 105152. [CrossRef]

- Wysocki, Oskar, Jessica Katharine Davies, Markel Vigo, Anne Caroline Armstrong, Dónal Landers, Rebecca Lee, and André Freitas. 2023, March. Assessing the communication gap between AI models and healthcare professionals: Explainability, utility and trust in AI-driven clinical decision-making. Artificial Intelligence 316, 103839. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Main findings: participants’ opinion on (a) potential value of Digital Twins; (b) potential value of Artificial Intelligence; (c) current usage of clinical decision support systems (CDSS) in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery; (d) participants’ main concern while using Digital Twins and Artificial Intelligence-based clinical decision support systems - automation bias; (e) considerations on legal protection while using them; and (f) opinion on considering patient preferences on systems’ recommendations.

Figure 1.

Main findings: participants’ opinion on (a) potential value of Digital Twins; (b) potential value of Artificial Intelligence; (c) current usage of clinical decision support systems (CDSS) in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery; (d) participants’ main concern while using Digital Twins and Artificial Intelligence-based clinical decision support systems - automation bias; (e) considerations on legal protection while using them; and (f) opinion on considering patient preferences on systems’ recommendations.

Figure 2.

Participants’ demographic information: (a) sex distribution, (b) age groups in years, (c) professions, (d) career stages in their current positions; y/o - years old (n=18).

Figure 2.

Participants’ demographic information: (a) sex distribution, (b) age groups in years, (c) professions, (d) career stages in their current positions; y/o - years old (n=18).

Figure 3.

Assessing familiarity and perceptions of Digital Twins and AI in clinical decision-making in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: comparison of participants’ (a) familiarity with Digital Twins (DT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) (n=15), (b) participants’ opinions on the potential autonomy levels (n=15), (c) the potential value (n=15 for AI, n=14 for DT), and (d) the contributions (n=15 for AI, n=14 for DT) of Digital Twins and AI in the clinical decision-making process.

Figure 3.

Assessing familiarity and perceptions of Digital Twins and AI in clinical decision-making in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: comparison of participants’ (a) familiarity with Digital Twins (DT) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) (n=15), (b) participants’ opinions on the potential autonomy levels (n=15), (c) the potential value (n=15 for AI, n=14 for DT), and (d) the contributions (n=15 for AI, n=14 for DT) of Digital Twins and AI in the clinical decision-making process.

Figure 4.

Role of clinical decision support systems in clinical practice in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: comparison of participants’ (a) usage of clinical decision support (n=17), (b) the importance of information resources (n=17), (c) understanding of the CDSS definition (n=17), and (d) ranking of CDSS features’ importance (n=15); AI - Artificial Intelligence, EHR - electronic health records.

Figure 4.

Role of clinical decision support systems in clinical practice in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: comparison of participants’ (a) usage of clinical decision support (n=17), (b) the importance of information resources (n=17), (c) understanding of the CDSS definition (n=17), and (d) ranking of CDSS features’ importance (n=15); AI - Artificial Intelligence, EHR - electronic health records.

Figure 5.

Challenges and conflicts that arise when using Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins in clinical practice in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: (a) a ranking the clinicians’ concerns regarding the adoption of AI and Digital Twins-based clinical decision support systems in their practice, (b) the most significant barriers to their implementation, (c) instances where recommendations are overridden, and (d) actions in situations where recommendations are difficult to implement (n=14).

Figure 5.

Challenges and conflicts that arise when using Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins in clinical practice in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: (a) a ranking the clinicians’ concerns regarding the adoption of AI and Digital Twins-based clinical decision support systems in their practice, (b) the most significant barriers to their implementation, (c) instances where recommendations are overridden, and (d) actions in situations where recommendations are difficult to implement (n=14).

Figure 6.

Liability issues that occur while using Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins technologies in medical practice in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: (a) clinicians’ confidence in legal protection and (b) legal responsibility when Artificial Intelligence- and Digital Twins-based decisions influence patient outcomes, and (c) safeguards needed for their regulation (n=13).

Figure 6.

Liability issues that occur while using Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins technologies in medical practice in hepatology and hepatobiliary surgery: (a) clinicians’ confidence in legal protection and (b) legal responsibility when Artificial Intelligence- and Digital Twins-based decisions influence patient outcomes, and (c) safeguards needed for their regulation (n=13).

Figure 7.

Patient preferences in the use of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins: (a) patients’ consent and (b, c) consideration of their preferences while using AI and Digital Twins-based clinical decision support tools’ (CDSS) recommendations in their treatment (n=13).

Figure 7.

Patient preferences in the use of Artificial Intelligence and Digital Twins: (a) patients’ consent and (b, c) consideration of their preferences while using AI and Digital Twins-based clinical decision support tools’ (CDSS) recommendations in their treatment (n=13).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 1996 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).