1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD), a common consequence of diabetes and high blood pressure, is characterized by the gradual loss of kidney functions. The underlying pathology is hallmarked by chronic inflammation and tubulointerstitial fibrosis, i.e., excessive deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) that destroys functional tissue [

1]. The number of patients with CKD and kidney fibrosis is rapidly increasing, leading to a serious public health problem [

2]. However, our understanding of the molecular pathogenesis of fibrosis remains incomplete. Activated fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that overproduce ECM, are key pathogenic executors in fibrosis. Importantly, accumulating evidence from many studies now also reveals the importance of cues derived from surrounding cells, including the tubular epithelium, in activation of these ECM producing cells (reviewed in [

3,

4,

5]). Epithelial-mesenchymal crosstalk is mediated by factors released from tubular cells undergoing a pro-fibrotic phenotypic reprogramming, or partial epithelial-mesenchymal transition, leading to a pro-fibrotic epithelial phenotype (PEP) [

6]. This process can be induced by injury and cytokines, including TNFα and TGFβ1 [

7,

8,

9,

10]). TGFβ1 is one of the most important inducers of fibrogenesis (e.g., [

11]). We and others have highlighted the significance of RhoA signaling in tubular pro-fibrotic reprogramming [

6,

12,

13,

14]). Our data revealed early RhoA activation in tubular cells in a murine model of kidney injury and fibrosis [

6] and following stimulation by inflammatory mediators [

12,

15]. Myocardin-related Transcription Factors (MRTF-A and B) are key co-activators of serum response factor (SRF) that act downstream from RhoA (reviewed in [

16,

17]). MRTFs shuttle between the cytosol and the nucleus, controlled by the polymerization state of actin. RhoA-induced F-actin polymerization induces their nuclear accumulation, where the MRTF/SRF complex binds to CARG domains in the promoters of fibrosis-related target genes and initiates their transcription [

18,

19]. Key MRTF-dependent tubule-derived fibrogenic mediators include Cellular communication network factor 2 (CCN2), also known as Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF) and TGFβ1 itself [

6].

RhoA dysregulation during inflammation and injury repair contributes to a vicious cycle leading to maladaptive repair and fibrosis [

17,

20]. Rho family proteins are controlled by a large network of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEF) that promote their activation, and GTPase activating proteins (GAP) that enhance inactivation [

21,

22]. We have identified GEF-H1 (

ARHGEF2), as a key activator of RhoA in kidney tubular cells [

15]. GEF-H1 is a Dbl family GEF highly expressed in epithelial cells [

23,

24]. Its dysregulation was associated with various pathological conditions, including cancer, organ fibrosis and kidney disease [

13,

25,

26,

27,

28]. We have recently shown that GEF-H1 expression is elevated in a mouse kidney fibrosis model and in tubular cells stimulated by pro-fibrotic cytokines [

12]. Thus, accumulating evidence points to a central role of GEF-H1 in fibrogenesis. GEF-H1 is controlled by interacting proteins that localize it to the microtubules and intercellular junctions, and by phosphorylation (e.g., [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]). It is activated in response to an array of stimuli, including various inflammatory and fibrogenic input, such as TGFβ1, TNFα and mechanical stress [

15,

28,

34,

35]. However, fibrosis-relevant control of GEF-H1 activity remains incompletely understood. In search for new regulators, in this study we identified Myotonic dystrophy-related Cdc42-binding kinase α (MRCKα/CDC42BPA), as an interactor of GEF-H1. MRCK belongs to the AGC (PKA, PKG and PKC) kinase family [

36,

37,

38,

39]. It has three isoforms, closely related to Rho kinase. MRCK family kinases control epithelial apico-basal polarization, cell migration and tissue remodeling [

38]. However, their role in organ fibrosis or kidney disease remains unexplored.

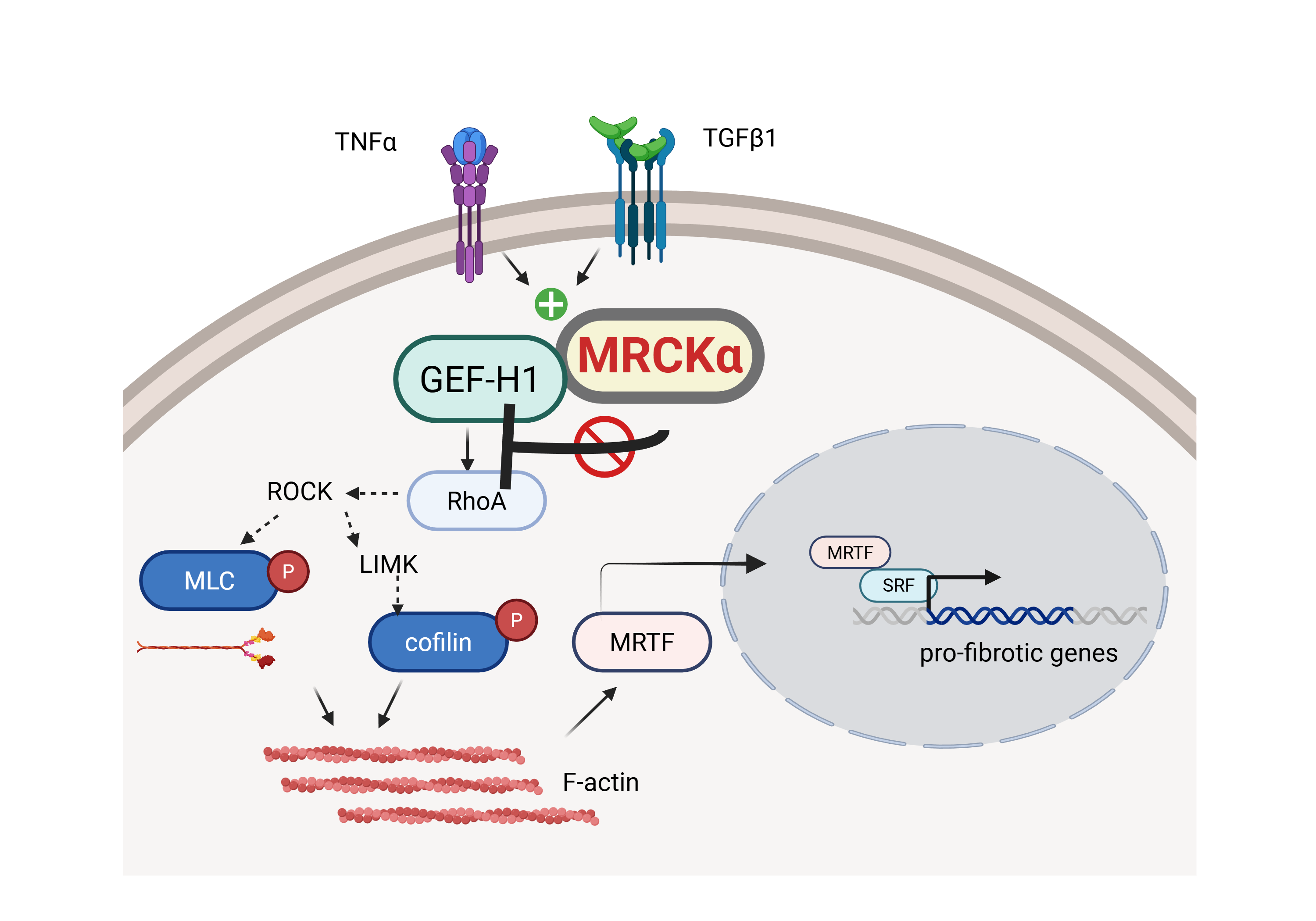

In this study we show that MRCKα inhibits GEF-H1/RhoA signaling, thereby reducing cytoskeleton remodelling, MRTF nuclear translocation and MRTF-dependent fibrotic gene expression. Overall, our findings establish MRCKα as a new suppressor of the GEF-H1/RhoA/MRTF axis, with important implications for fibrogenesis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Antibodies

TGFβ1 was from MedChem Express (Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA, Cat#HY-P7118) or R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA, Cat#240-B-002). Tumor Necrosis Factor α (TNFα) was purchased from MedChem Express (Cat# HY-P7058). The following GEF-H1 antibodies were used: for immunoprecipitation: Cat# NBP2-21577, RRID: AB_3265603 (Novus, Centennial, CO, USA); for proximity ligation assay, mouse anti-GEF-H1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) Cat# MA5-27803, RRID:AB_2735201) and for western blotting: Cat# 4076, RRID: AB_2060032 (Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, Massachusetts, USA). MRCKα antibodies used were as follows: for immunoprecipitation and western blotting Cat# A302-694A, RRID:AB_10750425 (Thermo Fisher Scientific); and rabbit anti-MRCKα for proximity ligation assay: Cat#GTX10259 RRID:AB_1240609 (GeneTex Inc., Irvine, CA, USA). The following antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology: FLAG (Cat# 8146, RRID: AB_10950495), RhoA (Cat# 2117S, RRID: AB_10693922), Phospho-Myosin Light Chain 2 (Thr18/Ser19) (E2J8F0) (Cat# 95777, RRID:AB_3677547), p-cofilin (Ser3) (Cat# 3313, RRID: AB_2080597), cofilin (Cat# 5175, RRID: AB_10622000), MRTF B (Cat# 14613, RRID: AB_2798539). Other antibodies used were: GFP (Cat# 66002-1-Ig, RRID: AB_11182611) and MRTF-A (Cat# 21166-1-AP, RRID:AB_2878822) from Proteintech (Rosemont, IL, USA); GAPDH (Cat# 39-8600, RRID: AB_2533438) from Thermo Fisher Scientific and α-smooth muscle actin (SMA) (Cat# ab150301, RRID:AB_3675461) from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). Secondary antibodies used for Western blotting were from Cell Signaling Technology: HRP-linked anti-rabbit IgG (Cat# 7074, RRID: AB_2099233) and HRP-linked anti-mouse IgG, (Cat#7076).

2.2. Cell Culture and Treatment

LLC-PK

1, a kidney tubule epithelial cell line (male) was from the European Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures (Wiltshire, UK), (ECACC Cat# 86121112, RRID: CVCL_0391). This cell line was used in our previous studies, e.g., ([

12,

40]). Human Embryonic kidney cells-293 (HEK-293) (female) (Cat# CRL-1573, RRID: CVCL_0045) was from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). Tissue culture media and reagents for culturing LLC-PK

1 and HEK cells were from Thermo Fisher/Life Technologies. Both cell lines were maintained in a low glucose DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in an atmosphere containing 5% CO

2. Unless otherwise stated, cells were serum depleted overnight before experiments. Human hTERT-immortalized renal proximal tubule epithelial cells (RPTEC/TERT1) (male) were from The American Type Culture Collection (CRL-4031). These cells were cultured in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (Cat# M4526, Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, ON, Canada), supplemented with RPTEC Complete supplement (Cat# MTOXRCSUP) and Gentamicin (G1397). RPTECs were incubated in culture medium without the supplement overnight prior to experiments.

For cytokine treatment, cells were grown to 100% confluence, serum/supplement depleted as indicated, and TNFα (20 ng/ml) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/mL) was added for the indicated times.

2.3. Plasmid and Short Interfering RNA (siRNA) Transfection

FLAG-tagged GEF-H1 plasmids (WT and N-terminal GEF-H1 (1-443) in pCMV-Tag 2B and C-terminal GEF-H1 (444-985) in pCMV-Tag 2C vector) were a kind gift from Dr. H. Miki (Nishikyō-ku, Kyoto, Japan) [

32]. GFP-GEF-H1-WT or GFP- GEF-H1-ΔC constructs were a kind gift from Dr. M. Kohno (Nagayo, Nagasaki, Japan). These constructs were generated as described in [

41] by cloning into a pEGFP-C1 expression vector. GFP-GEF-H1-DH mutant was a kind gift from Dr. M. Bokoch (The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). This mutant was prepared by site-directed mutagenesis to generate a Tyr to Ala mutation at residue 393 in the conserved QRITKY sequence in the DH domain of GEF-H1 [

29]. MRCKα (CDC42BPA) cloned into the pReceiver-M56 vector containing an mCherry tag was purchased from GeneCopoeia (Maryland, Mid-Atlantic, USA Cat#EX-T0588-M56).

For immunoprecipitation experiments HEK-293 cells were grown in 10 cm dishes to 70-80% confluence and transfected with 4 µg of FLAG- or GFP-tagged GEF-H1 constructs using Fugene 6 transfection reagent (Cat# E2691, Promega Madison, WI, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were used 48 h post-transfection.

For siRNA-mediated silencing oligonucleotides were purchased from Dharmacon/Horizon Discovery (Lafayette, CO, USA). The non-related control siRNA (NR siRNA) was purchased from Dharmacon/Horizon Discovery (Cat nr D-001810-01-50) or MedChemExpress (Cat#HY-150150).

Table 1 lists the siRNA sequences used in LLC-PK

1 cells. For silencing proteins in the human RPTECs, the following predesigned siRNAs were used: ON-TARGETplus Human CDC42BPA (8476) siRNA (MRCK) cat# J-003814-14 and J-003814-15 (Horizon Discovery) and human ARHGEF2 siRNA (9181) cat #J-009883-06 and J-009883-07.

Cells were transfected using 100nM siRNA using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Cat#13778075, Thermo Fisher Scientific) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For MRTF A and B silencing, 50nM of each siRNA was used. Unless otherwise indicated, the experiments were performed 48 hours after transfection. For co-silencing GEF-H1 and MRCKα, the cells were sequentially transfected, as follows. First, they were transfected with GEF-H1 siRNA, and 24 hours or 6 hours later (as indicated in the legends), they were transfected with MRCKα siRNA for an additional 24h. Downregulation was routinely verified using Western blotting.

2.4. Immunoprecipitation (IP)

LLC-PK1 and HEK-293 cells were grown in 10 cm dishes. Where indicated, cells were transfected as described above. Cells were grown to 100% confluency, washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed with ice-cold NP-40 lysis buffer (150 mM NaCl, 30mM HEPES, 1% NP40, 0.25% Sodium deoxycholate, PH 7.5) containing1 mM Na3VO4 (Cat#0758, New England Biolabs, Whitby, ON, Canada), 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride (Cat# PMS444, Bioshop Burlington, ON Canada), protease and phosphatase inhibitors (cOmplete Mini, EDTA-free (cat# 4693159001) and PhosSTOP (cat# 4906845001) from Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 mins at 4°C. An aliquot of the supernatant was retained as input sample and the remaining supernatant was used for pre-clearing. For precipitating endogenous proteins, Pierce™ Protein A/G Agarose beads (Cat#PI20421, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were blocked by incubating with 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in NP40 lysis buffer for 1 hour at 4°C in a rotator, followed by washes with NP40 lysis buffer. The supernatants from the cell lysates were precleared for 1 hour at 4°C in a rotator using the A/G Agarose beads, then incubated with 3 µg of GEF-H1, or MRCKα antibody (1h), followed by incubation with blocked Pierce™ Protein A/G Agarose beads (3h).

For precipitating FLAG- and GFP-tagged GEF-H1, lysates were precleared using ChromoTek Binding Control Agarose Beads (Cat# bab, Proteintech), and immunoprecipitation was performed using ChromoTek DYKDDDDK Fab-Trap® Agarose (Cat#ffa, RRID:AB_2894836) or ChromoTek GFP-Trap® Agarose (cat#:gta, RRID:AB_2631357) from Proteintech, respectively, for 3 hours at 4°C using a rotator.

For all IP, following indicated times, beads were washed with ice-cold NP-40 lysis buffer three times, resuspended and boiled in Laemmli Sample Buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA, Cat# 1610737) and analysed by Western blotting.

For Mass spectrometry, cells were grown in 10 cm dishes, lysed as above, and lysates from 3 plates/sample were used for each condition. The IP was performed using the GEF-H1 antibody as above. Mass Spectrometry was performed by the Sparc Biocentre at The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, ON, Canada.

2.5. Western Blotting

Western blotting was done as in our previous studies (e.g., [

12]). Briefly, following the indicated treatments, cells were washed, lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 30 mM HEPES pH7.5, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100) supplemented with 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, and protease and phosphatase inhibitors, as for the NP40 lysis buffer used for IP. Lysates were centrifuged and protein concentration determined using bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific/ Pierce Biotechnology). Protein was separated by SDS polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferring to nitrocellulose membrane using standard protocols. The blots were blocked in Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST) containing 3% BSA for 1h, then incubated with the indicated primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, followed by washes, incubation with the corresponding peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and visualization with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) method (Cat#1705060, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). For multiple probing of the same blot, the blot was either stripped and re-probed or the membrane was cut horizontally and probed with different primary antibodies. ECL signals were captured using a BioRad ChemiDoc Imaging system. Densitometry was performed using ImageLab. Values were normalized using GAPDH as loading control, and expressed as fold change from control, taken as unity.

2.6. GEF-H1 and RhoA Activation Assay

Active GEF-H1 and RhoA (GTP-bound) were captured from cell lysates using GST-RhoA(G17A) or GST-RhoA-binding domain (RBD), amino acids 7–89 of Rhotekin, respectively as described in [

15,

42]. RhoA(G17A) cannot bind nucleotide and therefore has high affinity for activated GEFs [

43]. Confluent LLC-PK

1 cells were lysed with ice-cold assay buffer (100 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris base (pH 7.6), 20 mM NaF, 10 mM MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 0.1% SDS) containing 1 mM Na3VO4 and cOmplete Mini, EDTA-free protease inhibitor. After centrifugation, an aliquot of the supernatant was retained to sample input (total GEF-H1 or RhoA). The remaining supernatants were incubated with 20-25 µg of GST-RhoA(G17A) or GST-RBD beads (45 min, at 4°C), followed by extensive washes. Total and captured (active) proteins were analyzed by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry, as previously described ([

12]). Precipitated (active) GEF-H1 or RhoA for each condition was normalized using the corresponding total protein, and the fold change relative to control was calculated.

2.7. Immunofluorescence Microscopy

LLC-PK1 cells grown on coverslips were transfected and treated as indicated. Cells were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed with PBS, permeabilized and quenched with 0.1% Triton-PBS containing 100mM glycine. Following washing, coverslips were blocked with 3% BSA in PBS, then incubated with primary antibody (1:100) for 1 hour. Next, coverslips were washed and incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), F(ab’)2 Fragment secondary antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, Cat# 4413, RRID: AB_10694110) and 4′,6-Diamidine-2′-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI) (1:1000) (Cat# 10236276001, Roche Diagnostics). For F-actin staining, fixed, quenched and permeabilized cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor® 488 Phalloidin (Cat# 8878, Cell Signaling Technology) for 30 mins along with DAPI. The slides were visualized either using a Zeiss Widefield Microscope (63x objective), or a WaveFX spinning-disk confocal microscope (Quorum Technologies, Guelph, Canada) with an ORCA-flash4.0 digital camera with Gen II sCMOS image sensor. For confocal images, maximum intensity projection pictures were generated from Z-stack using the Metamorph software. All parameters for image acquisition were kept constant. Control and treatment groups were processed in parallel at the same time under the same conditions.

2.8. Proximity Ligation Assay (PLA)

RPTEC/TERT1 cells grown on coverslips were fixed, washed and permeabilized as described in 2.7. The PLA assay was performed using the Duolink In Situ Orange kit (cat#DUO92102, Millipore/Sigma-Aldrich), as recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, cells were blocked with the Duolink Blocking Solution (1h, room temperature). Primary antibodies (mouse anti-GEF-H1 (1:50) and rabbit MRCKα (1:500)) were diluted in the antibody diluent and incubated in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. Following washing, the PLA probes (Duolink In Situ PLA Probe Anti-Mouse MINUS and Anti-Rabbit PLUS, 1:5 dilution in antibody diluent) were added for 1h in a pre-heated humidified chamber at 37°C. Ligation was performed using Duolink Ligase (1:40 in ligation buffer, 30 min) at 37°C. The amplification reaction was performed using Duolink Polymerase (1:80, 100 min, 37°C). Cells were mounted with Duolink In Situ Mounting Medium containing DAPI and viewed using a WaveFX spinning-disk confocal microscope (Quorum Technologies, Guelph, Canada) with an ORCA-flash4.0 digital camera with Gen II sCMOS image sensor. Maximum intensity projection pictures were generated from Z-stack using the Metamorph software. The PLA signal was quantified by counting the puncta in each microscopic field and dividing it by the number of nuclei. For each experiment 3-5 randomly selected fields/coverslips were counted.

2.9. RT2 Profiler Fibrosis Array

An RT

2 Profiler™ Pig Fibrosis PCR Array was used to determine levels of 84 fibrosis-related genes (Cat# 330231, GeneGlobe ID: PASS-120Z, Qiagen (Montreal, QC, Canada). LLC-PK

1 cells were transfected with 100 nM NR or MRCKα siRNA. 24 hours post-transfection, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM medium followed by treatment with 10 ng/ml TGFβ1 for 24 hours. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Cat# 74104, Qiagen) and 1.5µg of RNA was used for gDNA elimination and cDNA synthesis using the RT

2 First strand kit (Cat# 330401, Qiagen). A the stock solution for each tested condition was prepared using RT

2 SYBR Green ROX qPCR Mastermix (Cat# 330523, Qiagen), plated in the RT

2 Profiler™ PCR Array and PCR was performed using a QuantStudio™ 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Relative gene expression was calculated using the ∆∆Ct method, and fold changes from control expressed. Fold changes were inputted into the R Studio Statistical software (version 4.4.2, R core team 2023, and Heatmap R package version 1.0.12, “pheatmap” plugin) (

https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pheatmap) . Heatmaps show Z scores (indicating the number of standard deviations a data point is from the mean) of genes across treatment groups. Fold change of selected genes upregulated by MRCKα silencing in the presence or absence of TGFβ1 was also calculated and graphed.

2.10. RNA Extraction and RT-PCR

LLC-PK

1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. Where indicated, 24 hours post-transfection, the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM medium and treated with 10 ng/mL of TGFβ1 for 24 hours. RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and 1µg of RNA was converted to cDNA using iScript™ cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Cat# 1708890) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. SYBR green-based real-time PCR was performed using QuantStudio™ 7 Flex Real-Time PCR System. Peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA) was used as the reference gene. Relative gene expression was calculated using the ∆∆Ct method.

Table 2 lists the qPCR Primer sequences used in this study.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

Western Blot and immunofluorescent pictures shown are representatives of at least three independent experiments. The graphs were generated using GraphPad Prism software (version 10.2.3) and the data are presented as means ±S.D. of the number of independent experiments indicated in the figure legends (n). Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism. Data normalized to the control, taken as unity, were analysed using one-sample t-test, with 1 as the hypothetical value, and significance was depicted using * symbols. Non-normalized samples were compared using unpaired t-test or one-way ANOVA, as indicated in the legends. Significance was denoted using #. Significance indicated on the figures is as follows: one symbol (# or *) p<0.05; two symbols (## or **) p<0.01; three symbols (### or ***) p<0.001; four symbols (#### or ****) p<0.0001.

4. Discussion

The key finding of this study is the demonstration that MRCKα interacts with and inhibits GEF-H1. We showed that MRCKα depletion augmented both basal and stimulus-induced GEF-H1 activity, promoted RhoA and MRTF activation and augmented TGFβ1-induced expression of several fibrosis-related genes. Taken together, our study identifies MRCKα as a new suppressor of the pro-fibrotic epithelial phenotype switch.

GEF-H1 is a ubiquitously expressed exchange factor for RhoA, RhoB and Rac, with vital roles in cytoskeletal organization, motility, epithelial polarization and permeability, as well as gene expression, including pro-fibrotic epithelial reprogramming (reviewed in [

23,

24]). Fine regulation of this protein is crucial for normal cellular functions, including epithelial homeostasis. Accordingly, GEF-H1 dysregulation was associated with various diseases. For example, GEF-H1-dependent signalling was reported to be upregulated in various cancers (e.g.

, [

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]). Studies from us and others also implicated GEF-H1 in heart, kidney and eye disease and organ fibrosis [

12,

25,

27,

28]. These diverse physiological and pathological functions are fine-tuned in a complex and incompletely understood manner. Resting GEF-H1 activity is suppressed by binding to intercellular junction proteins and/or the microtubules [

13,

29,

30,

31,

55,

56,

57]. Multiple phosphorylation sites in GEF-H1, that are targeted by a variety of kinases are also crucial for tight spatiotemporal control [

23]. For example, ERK1/2 is an activating kinase that was implicated in mediating effects of an array of stimuli (e.g.

, [

15,

41]). Interestingly, however, the majority of kinases were shown to interact with GEF-H1 appear to be inhibitory. Examples include the PAK family [

31,

58], Protein kinase A [

59], MARK2/Par1b [

32,

60] and cell cycle associated kinases such as Aurora A [

61]. Thus, kinase-dependent suppression is a key mechanism of GEF-H1 activity control.

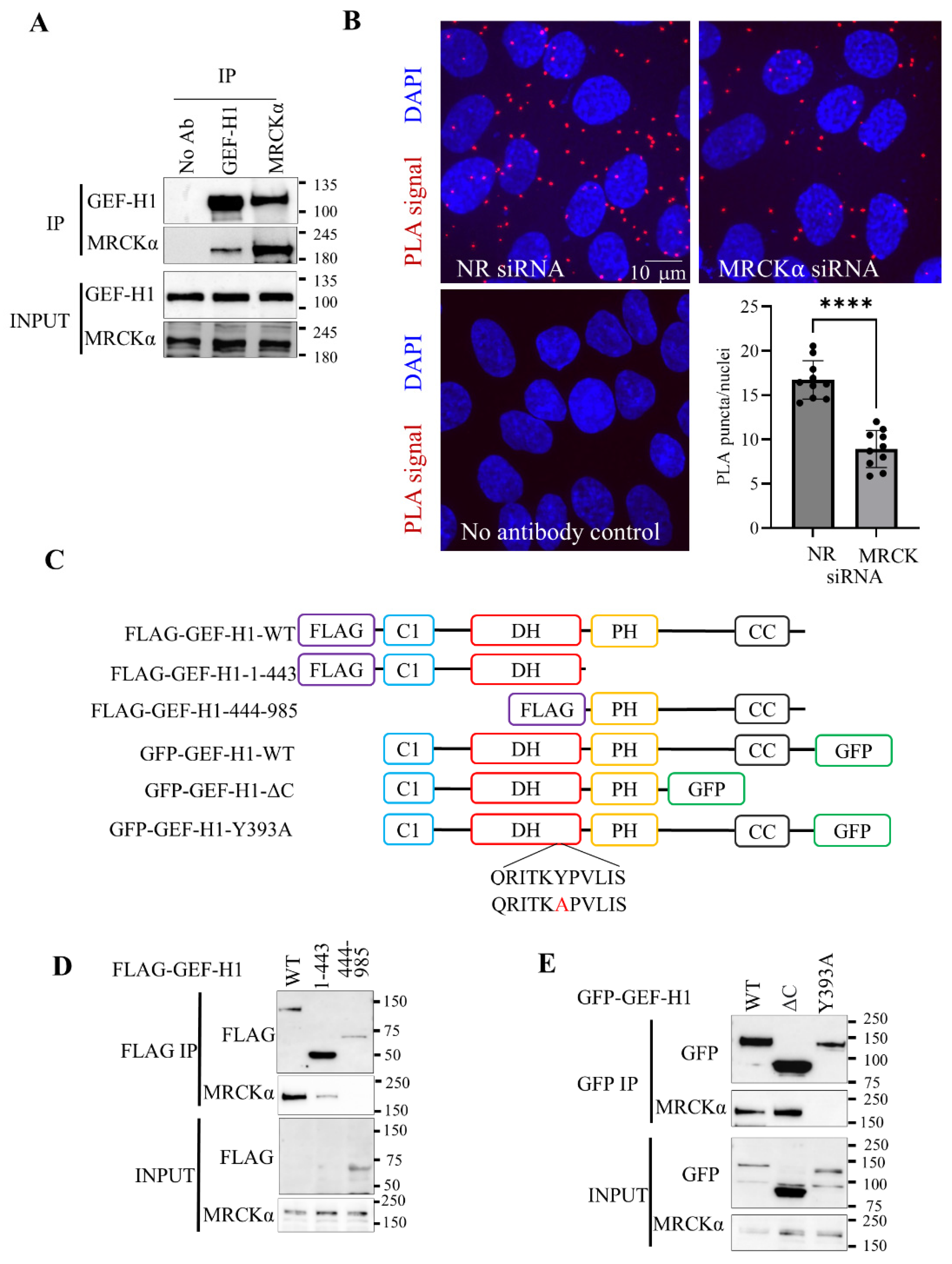

Our current study identifies MRCKα as a new interactor and inhibitor of GEF-H1. Using co-precipitation and in situ proximity ligation we verified interaction between MRCKα and GEF-H1 in kidney tubular cells. This finding is in line with a previous study that found these proteins in complex with BepC, an effector protein of the bacterium Bartonella [

62]. Moreover, GEF-H1 and MRCKα co-precipitated even in the absence of BepC. However, the functional relevance of this interaction remained unclear, as MRCKα knockout did not affect BepC-induced cytoskeleton remodelling. In the current study we provide further details of the interaction between these proteins. First, we mapped the MRCK binding site to the N-terminal portion of GEF-H1. Second, we showed that the interaction required an intact GEF-H1 DH domain, since a point mutation of a conserved site within the DH domain (Y393A) completely abolished the binding. The GEF-H1 DH domain physically interact with RhoA, and harbors the GEF activity [

24]. The Y393A mutant was shown to prevent interaction between GEF-H1 and RhoA [

24]. Thus, one possibility is that MRCKα binding might mask the site for the GEF-H1-RhoA interaction, resulting in inhibition of the effect of GEF-H1 on RhoA. MRCKα may also be in a tripartite complex with GEF-H1 and RhoA, affecting RhoA activation. Alternatively, MRCKα may phosphorylate GEF-H1, leading to its suppression. Although in LLC-PK

1 cells we have not been able to detect consistent changes in GEF-H1 phosphorylation upon MRCKα silencing, this may be due to techjnical limitations. Thus, further studies are warranted to define the exact mechanism, which may include MRCK-induced inhibitory GEF-H1 phosphorylation and/or hindrance of RhoA association or activation by GEF-H1.

Surprisingly, TNFα or TGFβ1, two cytokines known to activate GEF-H1 [

15,

28], increased the PLA signal, indicating that a larger pool of MRCKα and GEF-H1 were in close proximity after stimulation. This strongly suggests a negative feed-back mechanism, that may limit GEF-H1 activity and prevent its overactivation. This conclusion is supported by our data showing that MRCKα silencing augments not only basal, but also stimulus-induced GEF-H1 activation, and overexpression of a tagged MRCKα can mitigate TGFβ1-induced GEF-H1 activation.

Members of the MRCK family were identified as interactors of the Rho family small GTPase Cdc42 [

39,

44]. However, the exact role of Cdc42 in MRCK regulation remains unclear. Overexpression of active Cdc42 or silencing endogenous Cdc42 did not result in MRCKα activity changes [

63,

64]. Instead, Cdc42 binding likely controls MRCK localization, as Cdc42 downregulation was found to cause loss of lamellipodial MRCK in Hela cells [

64]. On the other hand, expression of a kinase-dead MRCKα was shown to block some downstream effects of active Cdc42 [

44]. Localized crosstalk between Rho family proteins has been documented in many systems, and MRCKα may represent a focal point for such interplay. Our finding that MRCKα is an inhibitor of GEF-H1/RhoA reveals an additional layer of complexity whereby Cdc42 might affect localized RhoA activity. Cdc42-dependent recruitment of MRCKα may lead to local inhibition of GEF-H1/RhoA signalling, for example in the lamellipodium of migrating cells, or during the development of epithelial polarity. Such crosstalk could also fine-tune perijunctional actomyosin contractility [

65]. Interestingly, GEF-H1 appears to integrate input from Rac and Cdc42 through PAK family kinases, that are also effectors of these small GTPases. PAK1 was shown to phosphorylate and inactivate GEF-H1, at least in part by regulating its microtubule binding [

31]. Further, in tubular cells we showed that TNFα-induced Rac activation promoted ERK-dependent stimulation of GEF-H1 towards RhoA [

33], and GEF-H1 phosphorylation status can determine which small GTPAse (e.g Rac or RhoA) is activated downstream [

33]. Together with the current study, these data further highlight the complext network of Rhio family regulation.

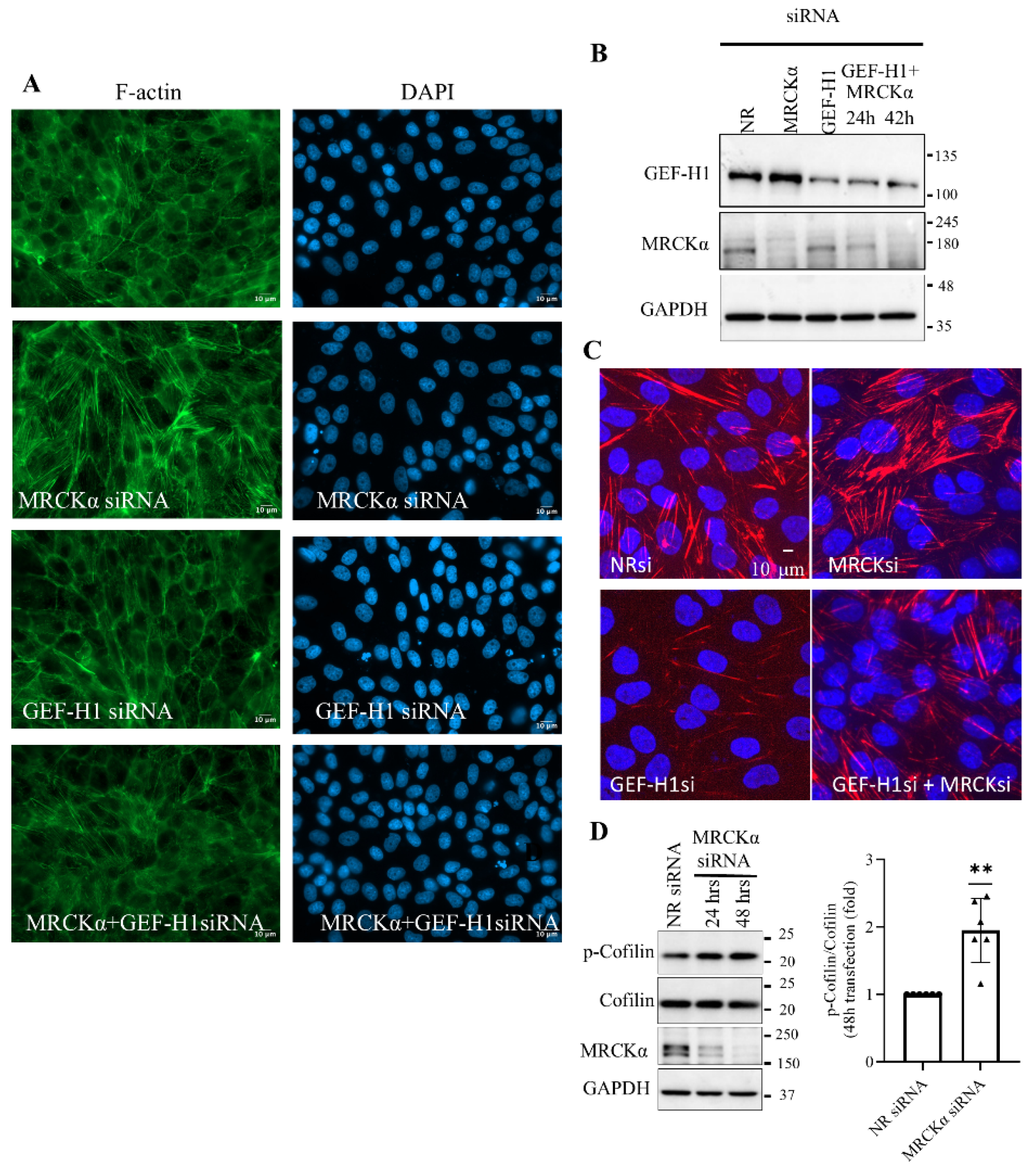

One key effect of MRCKα is the regulation of acto-myosin contractility. MRCKs can directly phosphorylate MLC, and can also control cofilin, a ubiquitous actin severing protein, through activating LIMK [

46,

66]. LIMK phosphorylates, and thereby inactivates cofilin, leading to increased actin polymerization [

67]. Both LIMK and MLC activity, however, are also controlled by RhoA/Rho kinase, and the effects of MRCKα on through these pathways appear to be opposite. Thus, the overall effect on pMLC, cofilin and F-actin of MRCKα in a given cell likely depends on the balance of the direct activating and indirect inactivating (through RhoA/Rho kinase) effects. We found that in tubular cells, downregulating MRCKα increased pMLC. It also induced cofilin phosphorylation and augmented F-actin levels through GEF-H1. This latter effects is similar to what was reported in breast cancer cells, where MRCKα knockout was also found to augment cofilin phosphorylation [

68]. Overall the cytoskeletal effecst we found in tubualr cells are in line with a suppressor role for MRCKα on RhoA-dependent cytoskeleotn remodelling and support the notion that MRCKα might also reduce MRTF avtivation, that is downstrem from F-actin.

GEF-H1 and RhoA are also key regulators of injury-induced epithelial reprogramming in tubular cells, and promote the production of pro-fibrotic mediators [

6]. Reprogrammed epithelial cells release various mediators to activate mesenchymal cells and enhance ECM production, a key step in fibrosis. Indeed, our data show that MRCK silencing augments the production of the matricellular signaling protein CCN2 (CTGF), a key profibrotic mediator. MRCKα silencing by itself also augments other fibrosis-related genes, and promotes the effects of TGFβ1. We also showed that MRCKα altered MRTF nuclear translocation, and MRTF-dependent gene transcription (e.g.

, ACTA2 and TNGLN) [

47]. However, the overall effect of MRCK is complex in this respect. While MRCKα silencing exerted a general positive effect on many genes we tested, a subset of genes showed reduced expression upon MRCKα silencing. Thus MRCKα may be a positive regulator of these . Further, MRCK silencing also significantly augmented SMAD7, that exerts a negative feed-back in TGFβ signalling and is considered anti-fibrotic [

69]. The comprehensive effect of MRCKα on TGFβ1 signalling itself warrants further studies. Overall, future studies involving animal models should reveal whether MRCKα expression or activity are affected by fibrogenesis, and explore its overall role in fibrogenesis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S..S, K.S and A.K.; methodology, V.S.S., Q.D., B.W., S.V.; formal analysis, V.S.S., Q.D., B.W., S.V.; investigation, V.S.S., Q.D., B.W., S.V.; resources, K.S.; data curation, V.S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S.S and K.S.; writing—review and editing, K.S and A.K.; visualization, V.S.S, B.W., S.V. and K.S.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, V.S.S.; funding acquisition, K.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

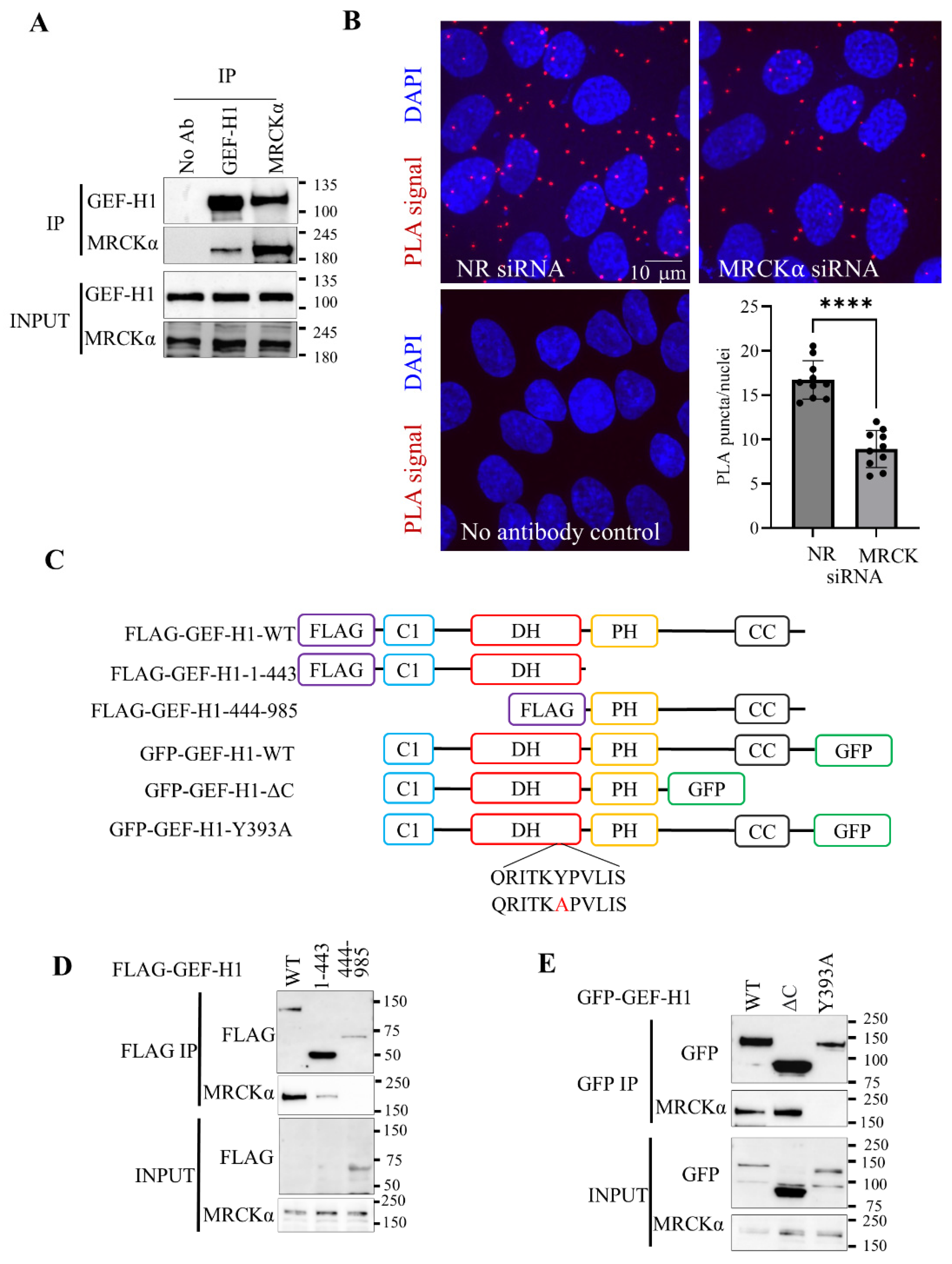

MRCKα interacts with the N-terminus of GEF-H1. (A) Endogenous GEF-H1 or MRCKα were immunoprecipitated from LLC-PK1 cells and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western Blotting (representative blot of n = 3). “No Ab” indicates IP without primary antibody, with beads alone. (B) RPTEC/hTERT cells grown on coverslips were transfected with control (non-related, NR) siRNA, or an MRCKα-specific siRNA, as indicated. PLA was performed using GEF-H1 and MRCKα-specific antibodies, as described in the Methods. Where indicated, the primary antibodies were omitted. The nuclei were counterstained using DAPI. The red puncta in 3-5 visual fields/coverslips were counted and divided by the number of nuclei. The graph shows mean+/-SD of 10 fields from 2 independent experiments (*** p<0.001, unpaired t-test, n=10). (C) FLAG- and GFP-tagged GEF-H1 constructs used. Domains of GEF-H1 include C1: zinc finger-like motif; DH: Dbl-homologous domain; PH: pleckstrin homology domain; Coiled: coiled-coil region. (D,E) FLAG- (D) or GFP- (E)-tagged GEF-H1 constructs were transfected in HEK-293 cells and immunoprecipitated through the corresponding tags. The co-immunoprecipitation of MRCKα was visualized by Western blotting (representative blots from n=3).

Figure 1.

MRCKα interacts with the N-terminus of GEF-H1. (A) Endogenous GEF-H1 or MRCKα were immunoprecipitated from LLC-PK1 cells and co-immunoprecipitated proteins were detected by Western Blotting (representative blot of n = 3). “No Ab” indicates IP without primary antibody, with beads alone. (B) RPTEC/hTERT cells grown on coverslips were transfected with control (non-related, NR) siRNA, or an MRCKα-specific siRNA, as indicated. PLA was performed using GEF-H1 and MRCKα-specific antibodies, as described in the Methods. Where indicated, the primary antibodies were omitted. The nuclei were counterstained using DAPI. The red puncta in 3-5 visual fields/coverslips were counted and divided by the number of nuclei. The graph shows mean+/-SD of 10 fields from 2 independent experiments (*** p<0.001, unpaired t-test, n=10). (C) FLAG- and GFP-tagged GEF-H1 constructs used. Domains of GEF-H1 include C1: zinc finger-like motif; DH: Dbl-homologous domain; PH: pleckstrin homology domain; Coiled: coiled-coil region. (D,E) FLAG- (D) or GFP- (E)-tagged GEF-H1 constructs were transfected in HEK-293 cells and immunoprecipitated through the corresponding tags. The co-immunoprecipitation of MRCKα was visualized by Western blotting (representative blots from n=3).

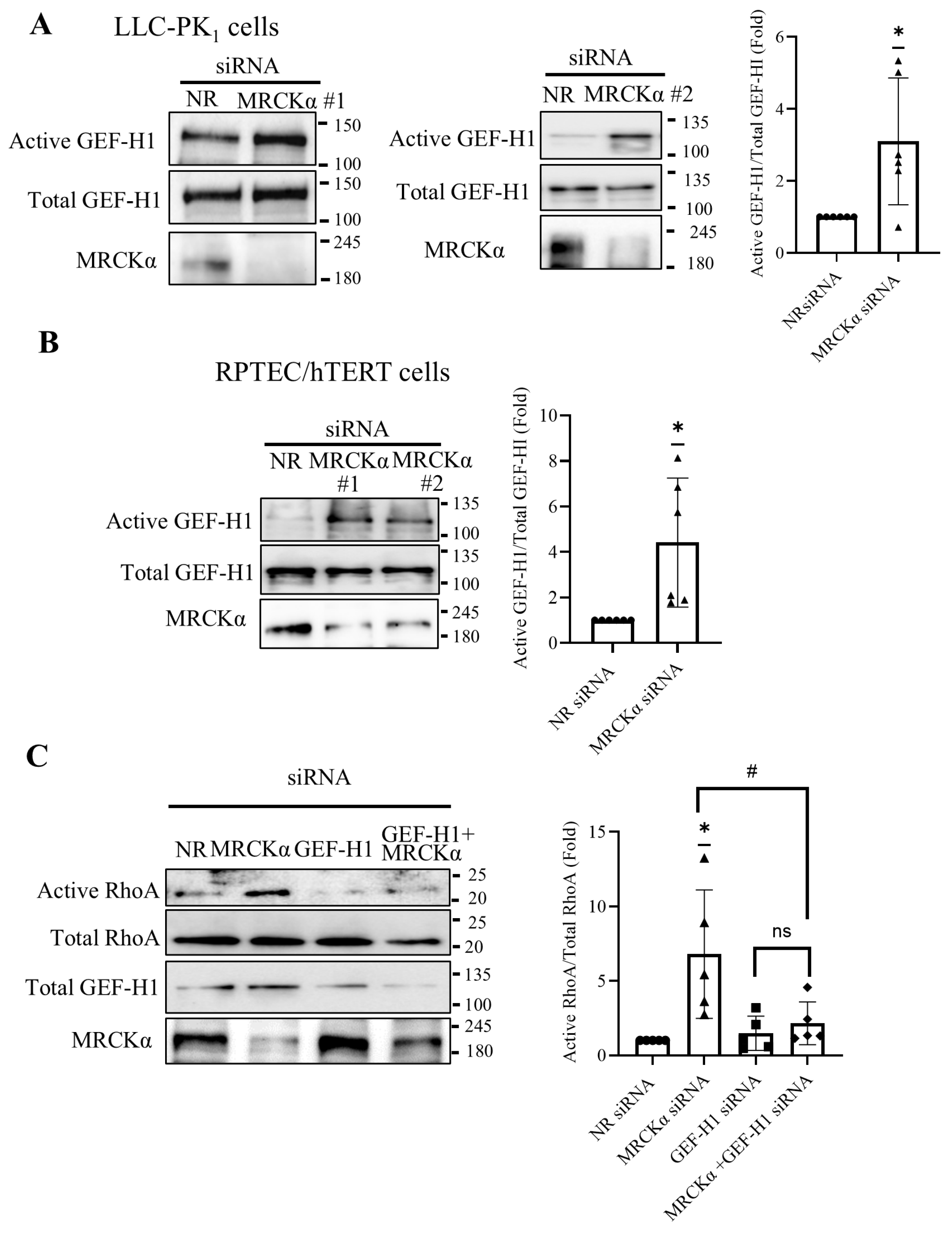

Figure 2.

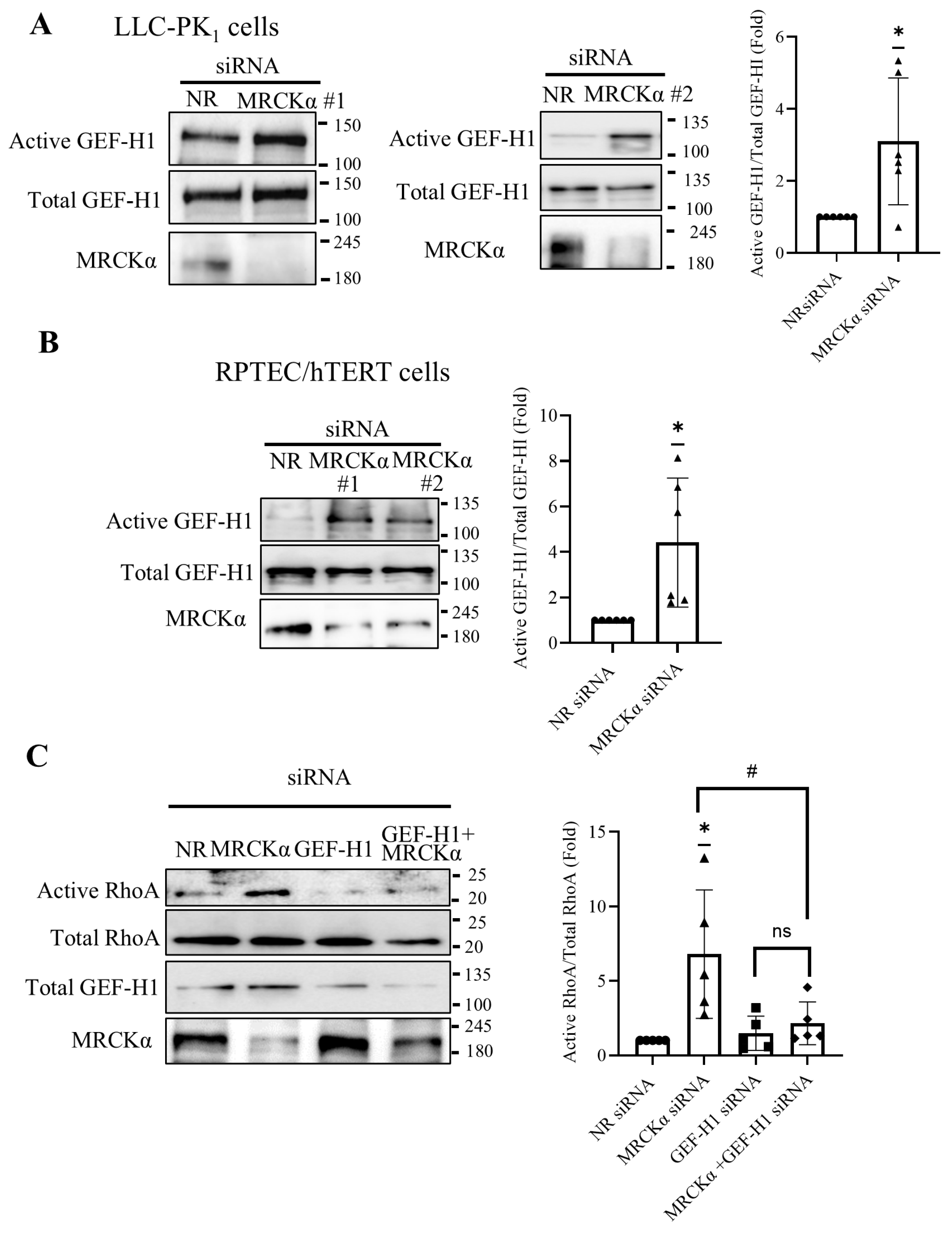

MRCKα suppresses GEF-H1 and RhoA activation. (A,B) LLC-PK1 (A) or RPTEC/hTERT cells (B) were transfected with NR siRNA, or two different MRCKα-specific siRNAs (100nM) for 48 hours. The cells were lysed and active GEF-H1 was captured using GST-RhoA(G17A) beads. Precipitated (active) and total GEF-H1 were detected by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry. The graphs show combined results obtained with the two siRNAs. Active GEF-H1 was normalized by the corresponding total GEF-H1 and expressed as fold change from control (taken as 1) (n=6 (3/siRNA), *p < 0.05, one sample t test vs. 1). (C) LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with NR, MRCKα or GEF-H1-specific siRNAs or their combination, as indicated. Active RhoA was captured using GST–RBD-coupled beads, and precipitated (active) and total RhoA, as well as GEF-H1 and MRCKα in the total cell lysates were detected by Western blotting. Active RhoA was normalized to the corresponding total RhoA, and expressed as fold change from control (taken as 1). (n=5, *p< 0.05, one sample t-test; # p< 0.05, one way ANOVA vs the indicated condition).

Figure 2.

MRCKα suppresses GEF-H1 and RhoA activation. (A,B) LLC-PK1 (A) or RPTEC/hTERT cells (B) were transfected with NR siRNA, or two different MRCKα-specific siRNAs (100nM) for 48 hours. The cells were lysed and active GEF-H1 was captured using GST-RhoA(G17A) beads. Precipitated (active) and total GEF-H1 were detected by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry. The graphs show combined results obtained with the two siRNAs. Active GEF-H1 was normalized by the corresponding total GEF-H1 and expressed as fold change from control (taken as 1) (n=6 (3/siRNA), *p < 0.05, one sample t test vs. 1). (C) LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with NR, MRCKα or GEF-H1-specific siRNAs or their combination, as indicated. Active RhoA was captured using GST–RBD-coupled beads, and precipitated (active) and total RhoA, as well as GEF-H1 and MRCKα in the total cell lysates were detected by Western blotting. Active RhoA was normalized to the corresponding total RhoA, and expressed as fold change from control (taken as 1). (n=5, *p< 0.05, one sample t-test; # p< 0.05, one way ANOVA vs the indicated condition).

Figure 3.

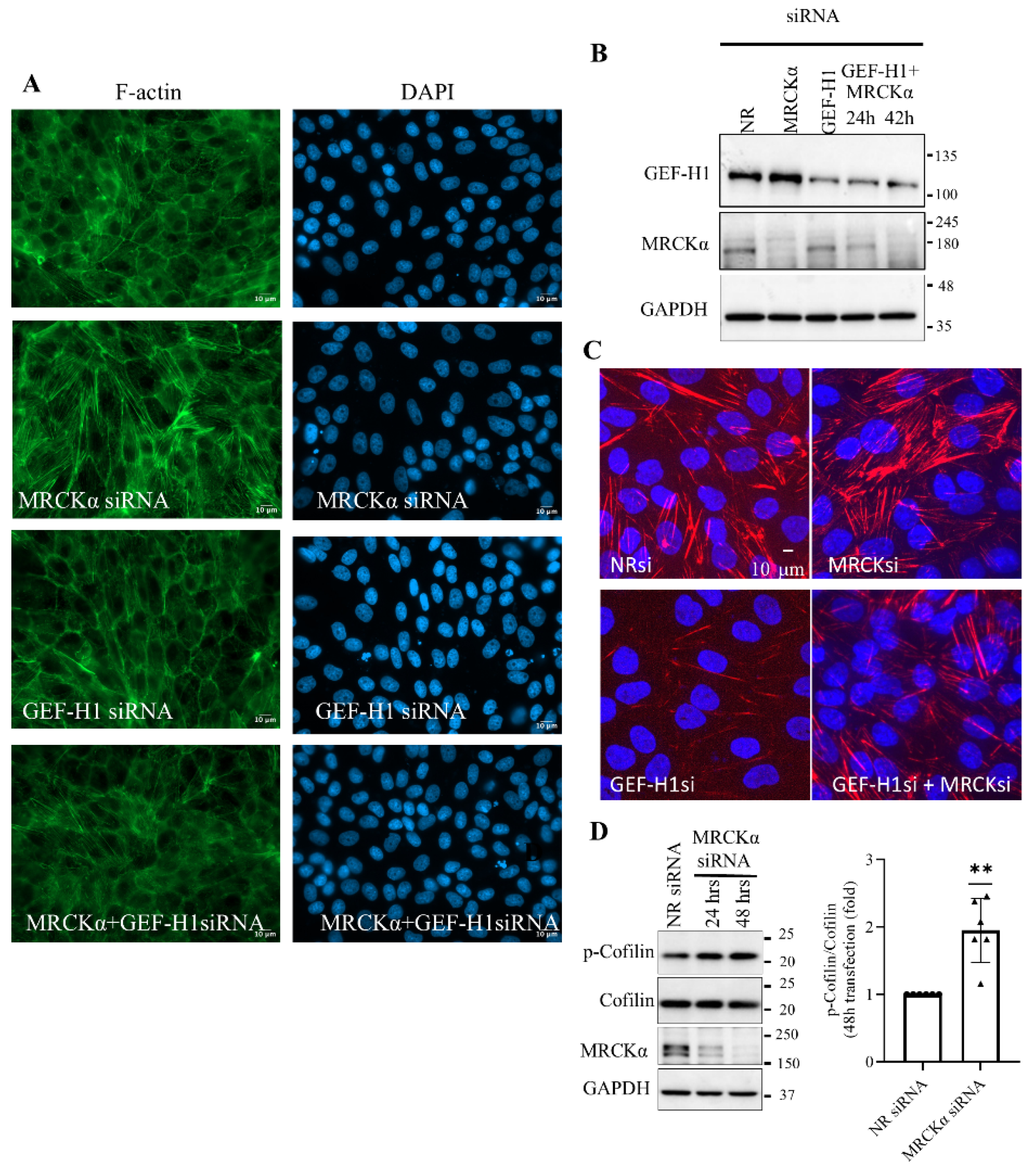

MRCKα suppresses phospho-cofilin and reduces GEF-H1-dependent actin stress fibers. LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with GEF-H1 siRNA and 6 hours or 24 hours later with MRCKα siRNA (24h or 42h total). (A) cells were fixed, permeabilized, and F-actin was visualized using Alexa Fluor® 488 Phalloidin and nuclei counterstained using DAPI. Pictures were taken using a Zeiss Widefield Microscope (63x objective). The scale bar represents 10µm. (B). GEF-H1 and MRCKα silencing was verified by Western Blotting. (C). Cells were transfected as indicated, fixed, permeabilized, and phospho-Ser18/Thr19 MLC and nuclei were stained. Pictures were taken using a confocal microscope. Maximum intensity projection pictures generated from Z-stack are show. The scale bar corresponds to 10 μm and applies to all images. (D). Phosphorylated and total cofilin were quantified using Western Blotting. Densitometry values show data for the 48h silencing of phospho-cofilin, normalized using the corresponding total cofilin, and expressed as fold change from control (taken as 1) (n=6, **p < 0.01, one sample t-test vs. 1).

Figure 3.

MRCKα suppresses phospho-cofilin and reduces GEF-H1-dependent actin stress fibers. LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with GEF-H1 siRNA and 6 hours or 24 hours later with MRCKα siRNA (24h or 42h total). (A) cells were fixed, permeabilized, and F-actin was visualized using Alexa Fluor® 488 Phalloidin and nuclei counterstained using DAPI. Pictures were taken using a Zeiss Widefield Microscope (63x objective). The scale bar represents 10µm. (B). GEF-H1 and MRCKα silencing was verified by Western Blotting. (C). Cells were transfected as indicated, fixed, permeabilized, and phospho-Ser18/Thr19 MLC and nuclei were stained. Pictures were taken using a confocal microscope. Maximum intensity projection pictures generated from Z-stack are show. The scale bar corresponds to 10 μm and applies to all images. (D). Phosphorylated and total cofilin were quantified using Western Blotting. Densitometry values show data for the 48h silencing of phospho-cofilin, normalized using the corresponding total cofilin, and expressed as fold change from control (taken as 1) (n=6, **p < 0.01, one sample t-test vs. 1).

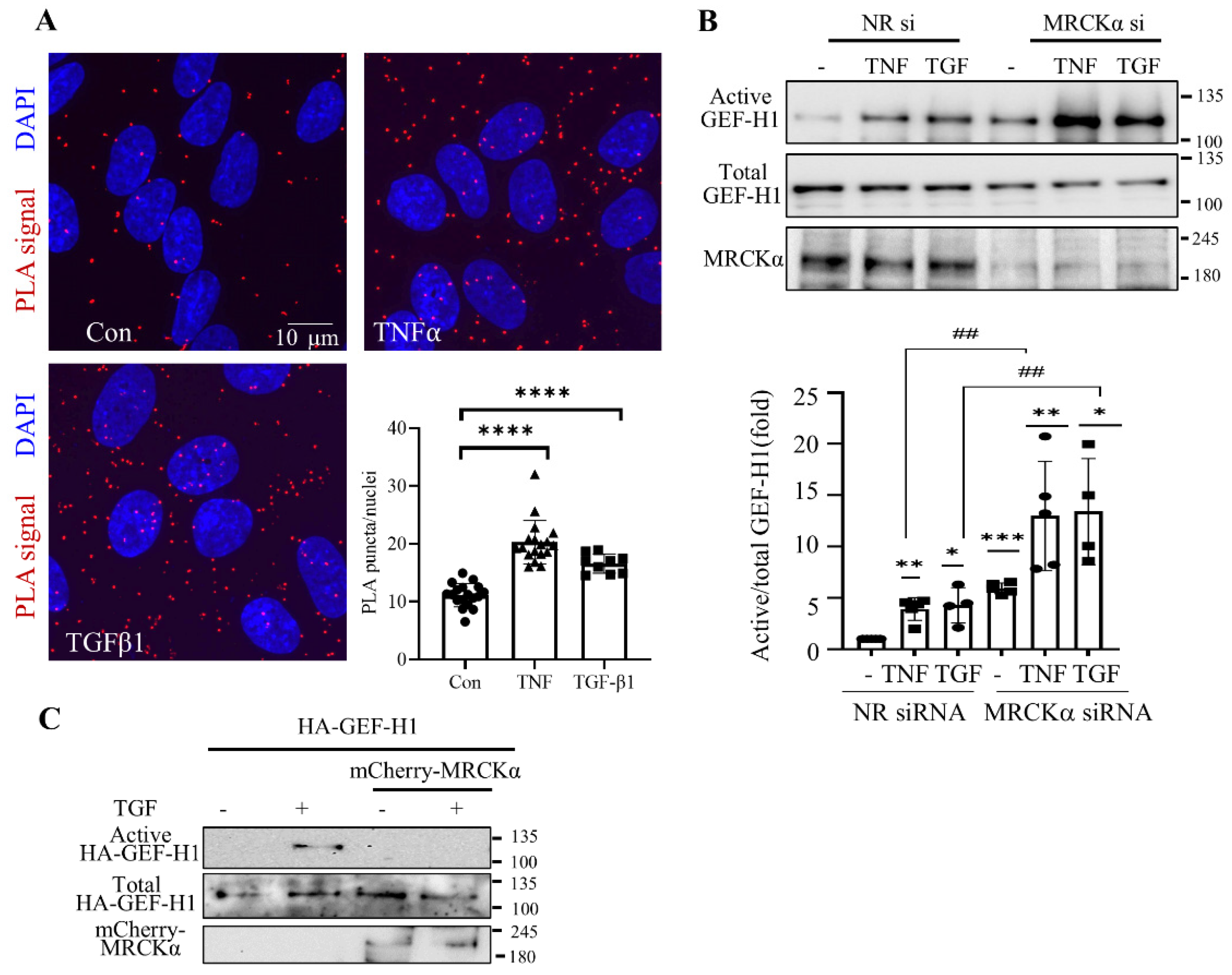

Figure 4.

MRCKα blunts cytokine-induced GEF-H1 activation. (A). RPTECs were stimulated by TNFα (20 mg/ml) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) for 15 min, and PLA was performed and quantified as in

Figure 1 (n=6 independet experiments for control and TNF treatment, n=3 for TGFβ1 treatment, 3 fields/experiment) **** p<0.0001, unpaired t-test.

(B). LLC-PK

1 cells were transfected with control (NR) or MRCKα-specific siRNAs. Cells were stimulated with TNFα or TGFβ1 for 15 min and active GEF-H1 precipitated and quantified as in

Figure 2 (n=4-5, (n=5, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001, one sample t-test vs 1; ## p< 0.01, one way ANOVA vs the indicated condition).

(C). LLC-PK

1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged GEF-H1 with or without mCherry-tagged-MRCKα, and 48 h later the cells were stimulated with TGFβ1(10 min). GEF-H1 activation was measured as in A, and the precipitation of active HA-GEF-H1 was detected by Western blotting (representative of n=3).

Figure 4.

MRCKα blunts cytokine-induced GEF-H1 activation. (A). RPTECs were stimulated by TNFα (20 mg/ml) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) for 15 min, and PLA was performed and quantified as in

Figure 1 (n=6 independet experiments for control and TNF treatment, n=3 for TGFβ1 treatment, 3 fields/experiment) **** p<0.0001, unpaired t-test.

(B). LLC-PK

1 cells were transfected with control (NR) or MRCKα-specific siRNAs. Cells were stimulated with TNFα or TGFβ1 for 15 min and active GEF-H1 precipitated and quantified as in

Figure 2 (n=4-5, (n=5, *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001, one sample t-test vs 1; ## p< 0.01, one way ANOVA vs the indicated condition).

(C). LLC-PK

1 cells were transfected with HA-tagged GEF-H1 with or without mCherry-tagged-MRCKα, and 48 h later the cells were stimulated with TGFβ1(10 min). GEF-H1 activation was measured as in A, and the precipitation of active HA-GEF-H1 was detected by Western blotting (representative of n=3).

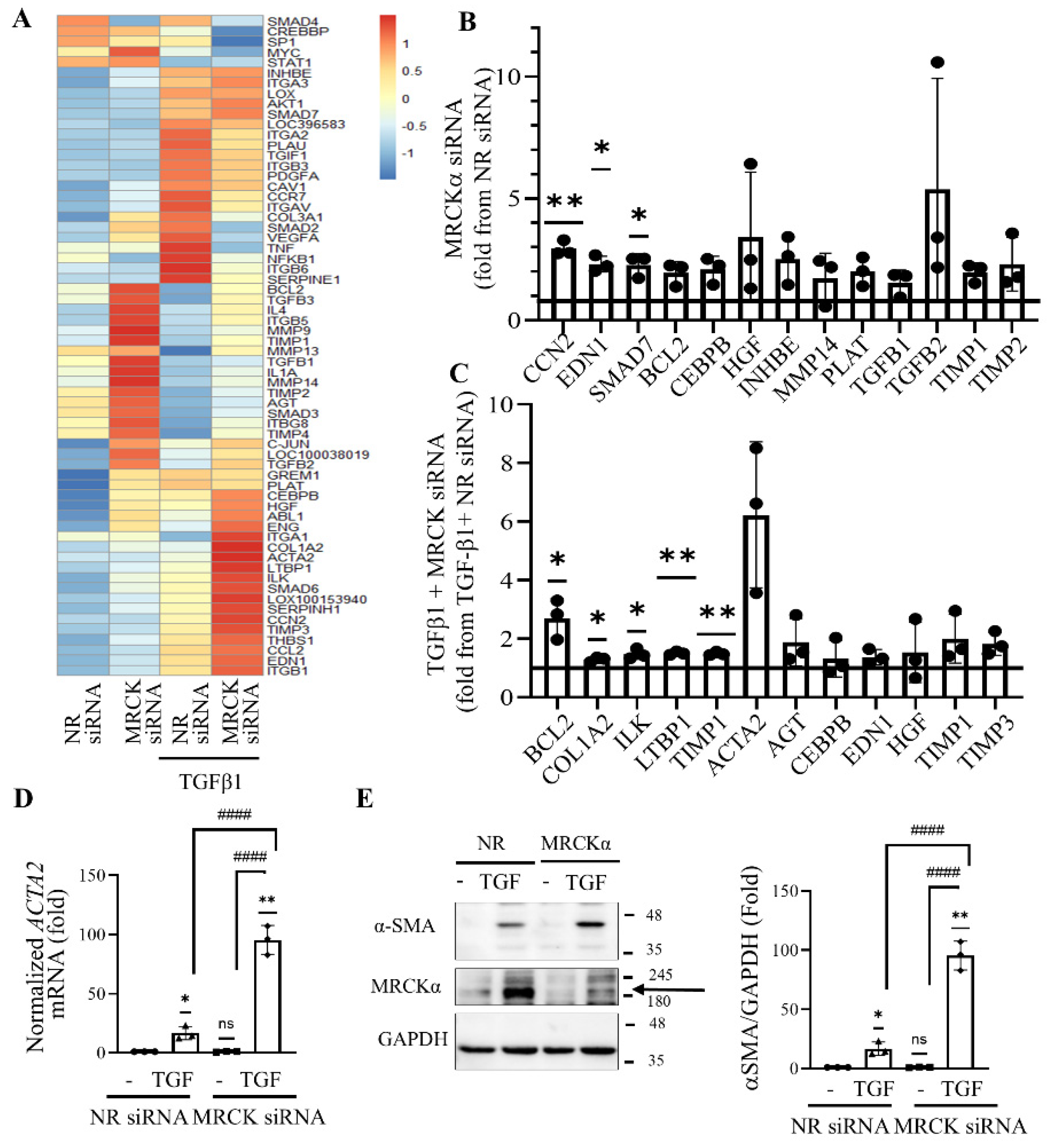

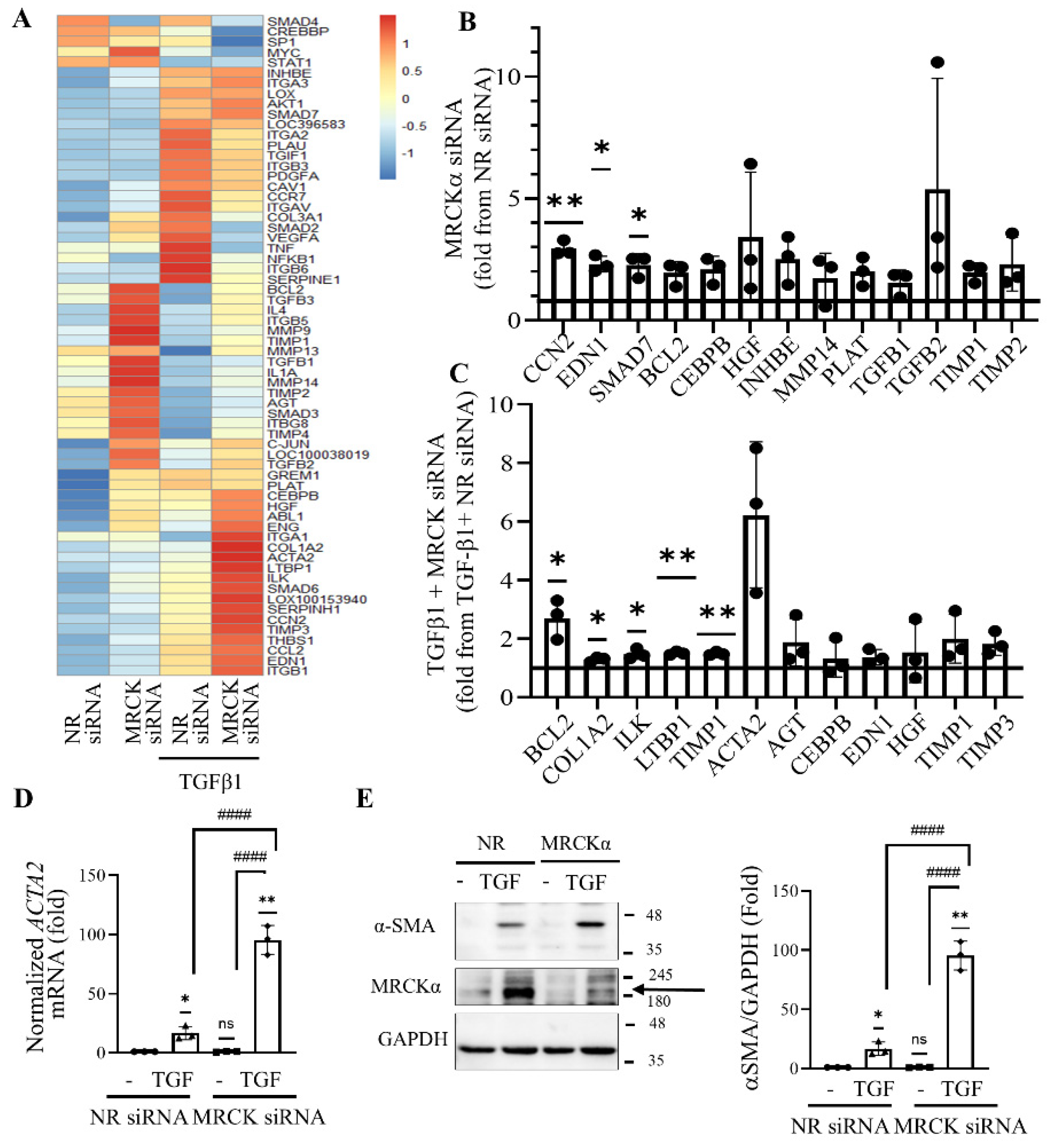

Figure 5.

MRCKα suppresses fibrosis-associated genes. (A). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with NR or MRCKα specific siRNA for 48 hours. Twenty-four hours post-transfection the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM supplemented with 10 ng/mL TGFβ1 for 24 hours, as indicated. The samples were analyzed using a Qiagen RT2 Profiler™ Pig Fibrosis gene PCR array. The heatmap shows Z scores, calculated using fold changes of the relative gene expression. (B) Genes that are upregulated in the array by at least 1.5-fold upon MRCKα silencing compared to the control (taken as 1). (C) Genes that are upregulated in the array by at least 1.5-fold by TGFβ1 in MRCKα siRNA transfecetd cells vs NR transfected cells taken as 1 (fold change). In B and C, n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 one sample t-test vs1). (D). Data from the fibrosis array for the ACTA2 mRNA expressed as fold change from control. (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, one sample t-test vs. 1; #### p<0.0001, one-way Anova vs the indicated condition). (E) LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and 4 hours later the medium was changed to serum-free DMEM with or without TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) for 48 hours. αSMA, MRCKα and GAPDH were detected by Western blotting (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, one sample t-test vs. 1; #### p<0.0001, one-way Anova vs the indicated condition). The MRCKα specific band is indicated by the arrow.

Figure 5.

MRCKα suppresses fibrosis-associated genes. (A). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with NR or MRCKα specific siRNA for 48 hours. Twenty-four hours post-transfection the medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM supplemented with 10 ng/mL TGFβ1 for 24 hours, as indicated. The samples were analyzed using a Qiagen RT2 Profiler™ Pig Fibrosis gene PCR array. The heatmap shows Z scores, calculated using fold changes of the relative gene expression. (B) Genes that are upregulated in the array by at least 1.5-fold upon MRCKα silencing compared to the control (taken as 1). (C) Genes that are upregulated in the array by at least 1.5-fold by TGFβ1 in MRCKα siRNA transfecetd cells vs NR transfected cells taken as 1 (fold change). In B and C, n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 one sample t-test vs1). (D). Data from the fibrosis array for the ACTA2 mRNA expressed as fold change from control. (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, one sample t-test vs. 1; #### p<0.0001, one-way Anova vs the indicated condition). (E) LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and 4 hours later the medium was changed to serum-free DMEM with or without TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) for 48 hours. αSMA, MRCKα and GAPDH were detected by Western blotting (n=3, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, one sample t-test vs. 1; #### p<0.0001, one-way Anova vs the indicated condition). The MRCKα specific band is indicated by the arrow.

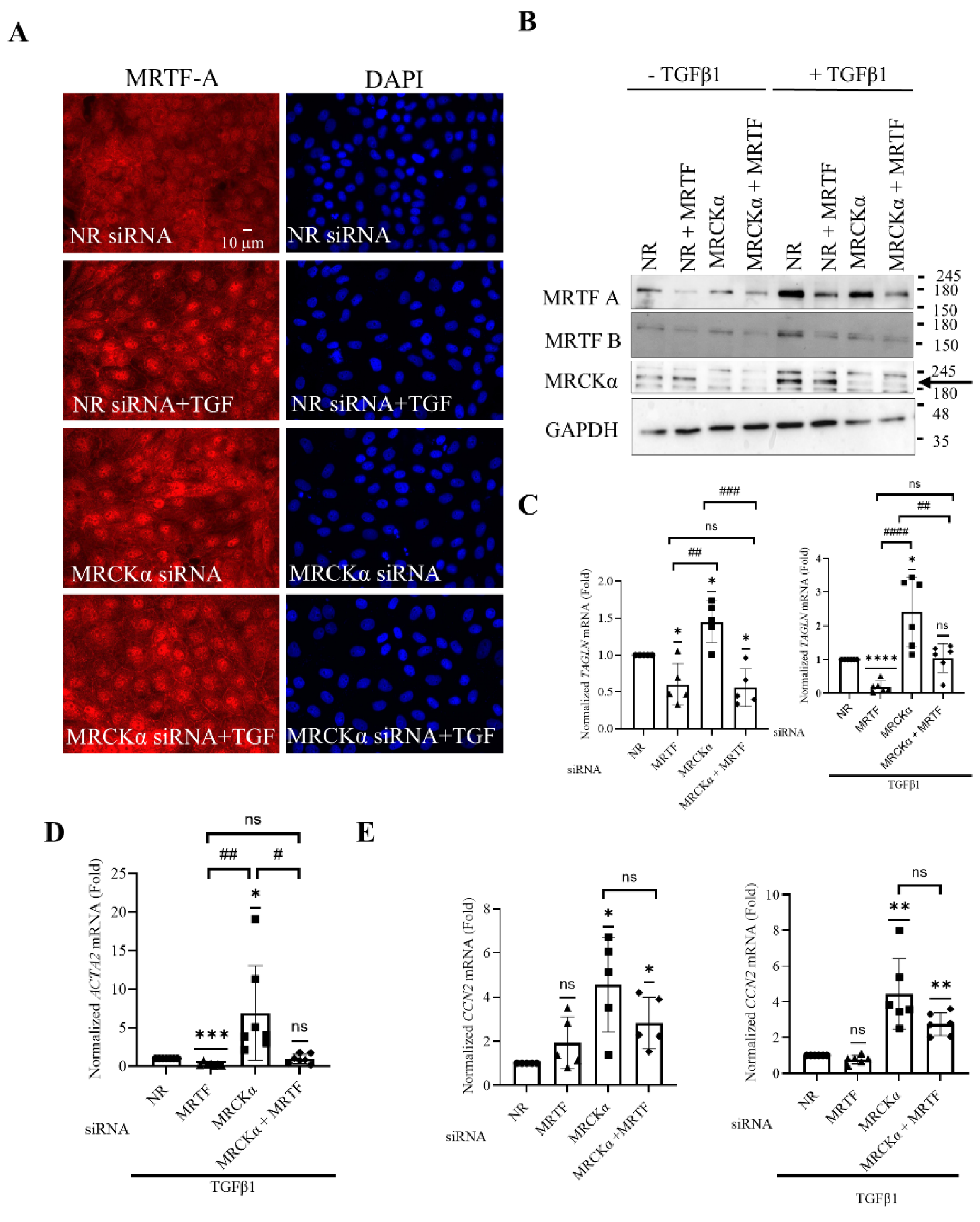

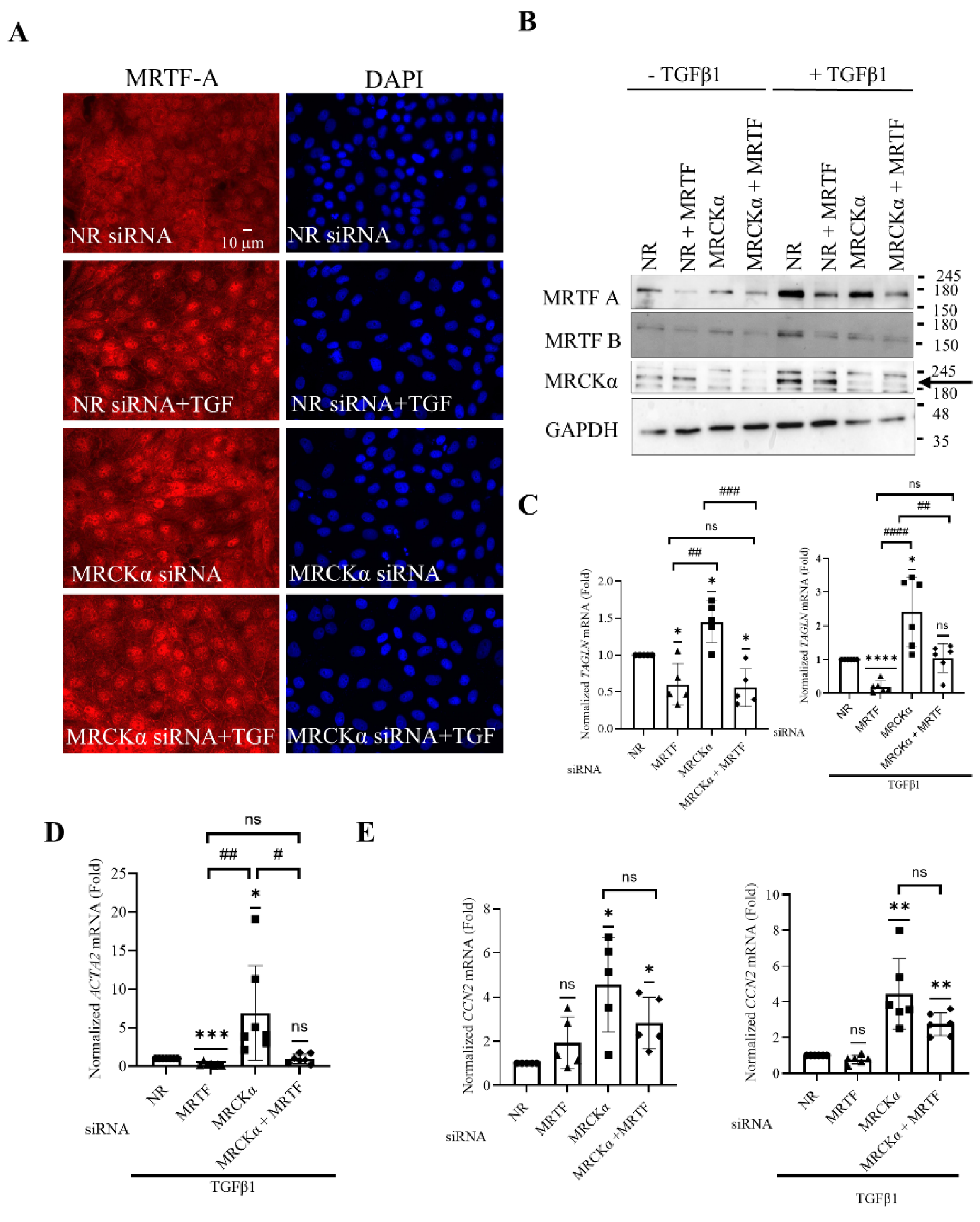

Figure 6.

MRCKα regulates MRTF-A nuclear translocation and MRTF-dependent gene transcription. (A). LLC-PK1 cells grown on coverslips were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and 32 h later the medium was changed to serum-free DMEM for 16 h. Cells were treated with or without TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml, 30 mins). MRTF-A was visualized by immunofluorescence using an Alexa Fluor 555-labelled secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. Pictures were taken using a Zeiss Widefield Microscope (63x objective). The scale bar represents 10µm. (B). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected and treated with TGFβ1 (48h), and the indicated siRNAs, and proteins detected using the indicated antibodies. The arrow points to MRCKα. (C-E). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and where indicated, treated with TGFβ1 for 24 h. RT-PCR was performed to measure TAGLN (C), ACTA2 (D) and CCN2 (E) mRNA as described in the Methods, using PPIA as the reference gene. Changes were expressed as fold change from NR siRNA transfected samples taken as 1 (n=5-7, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, one sample t-test vs. 1; # p<0.05, ## p<0.01, ### p<0.001, #### p<0.0001, one-way Anova vs the indicated condition).

Figure 6.

MRCKα regulates MRTF-A nuclear translocation and MRTF-dependent gene transcription. (A). LLC-PK1 cells grown on coverslips were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and 32 h later the medium was changed to serum-free DMEM for 16 h. Cells were treated with or without TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml, 30 mins). MRTF-A was visualized by immunofluorescence using an Alexa Fluor 555-labelled secondary antibody. Nuclei were stained using DAPI. Pictures were taken using a Zeiss Widefield Microscope (63x objective). The scale bar represents 10µm. (B). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected and treated with TGFβ1 (48h), and the indicated siRNAs, and proteins detected using the indicated antibodies. The arrow points to MRCKα. (C-E). LLC-PK1 cells were transfected with the indicated siRNAs, and where indicated, treated with TGFβ1 for 24 h. RT-PCR was performed to measure TAGLN (C), ACTA2 (D) and CCN2 (E) mRNA as described in the Methods, using PPIA as the reference gene. Changes were expressed as fold change from NR siRNA transfected samples taken as 1 (n=5-7, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001, one sample t-test vs. 1; # p<0.05, ## p<0.01, ### p<0.001, #### p<0.0001, one-way Anova vs the indicated condition).

Table 1.

Short interfering RNA sequences against porcine proteins (LLC-PK1 cells).

Table 1.

Short interfering RNA sequences against porcine proteins (LLC-PK1 cells).

| siRNA |

sequence |

| Porcine MRCKα #1 |

GGG AAA UGA AGA AGG GUU AUU |

| Porcine MRCKα #2 |

AGU UAG AAG AAG AGG UAA AUU |

| Porcine MRTF-A |

CCA AGG AGC UGA AGC CAA A |

| Porcine MRTF-B |

CGA CAA ACA CCG UAG CAA A |

Table 2.

Primers for detecting porcine mRNA used in the study.

Table 2.

Primers for detecting porcine mRNA used in the study.

| siRNA |

sequence |

| CCN2/CTGF F |

GTG AAG ACA TAC CGG GCT AAG |

| CCN2/ CTGF R |

GAC ACT TGA ACT CCA CAG GAA |

| TAGLN E3 F |

GAG CAG GTG GCT CAG TTC TT |

| TAGLN E3 R |

CCA CGG TAG TGT CCA TCA TTC |

| ACTA2 F |

CGTCCTAGACATCAGGGGGT |

| ACTA2 R |

GGGGCAACACGAAGCTCATT |

| PPIA F |

CGG GTC CTG GCA TCT TGT |

| PPIA R |

TGG CAG TGC AAA TGA AAA ACT G |