1. Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common metabolic disorder during pregnancy characterized by glucose intolerance, which can lead to adverse outcomes for both the mother and child, including macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, neonatal hypoglycemia, and long-term metabolic disease in the offspring [

1,

2]. Globally, the prevalence of GDM ranges between 5% and 20%, depending , and it is increasing in parallel with maternal age, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle [

1]. Women with GDM are seven times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes later in life, and their offspring are at an increased risk for obesity, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease [

1,

2]. Thus, GDM not only represents a serious problem during pregnancy, but also it is a major risk for developing a cardiometabolic disease beyond pregnancy.

Beyond this, there is increasing attention on the impact of GDM on the fetal cardiovascular system. Our group and others have observed that fetuses of mothers with GDM show structural and functional cardiac alterations, including interventricular septal hypertrophy, increased myocardial mass, impaired diastolic relaxation, and abnormal global myocardial performance index. Aguilera et al. found that women with GDM and their fetuses both had subclinical cardiac dysfunction in the third trimester, with fetuses demonstrating more globular-shaped hearts with increased right and left ventricular sphericity indices and reduced global systolic performance [

3]. Yovera et al. showed that GDM was associated with significant changes in fetal cardiac morphology and function between the second and the third trimester, including impaired right ventricular function and abnormal global sphericity index [

4]. More recently, Huluta et al. reported that even at midgestation and prior to the diagnosis of GDM, fetuses already showed early mild increases in septal thickness and left atrial area, although systolic and diastolic function remained preserved [

5]. These studies support the concept of early diabetic cardiomyopathy in utero, which may contribute to long-term cardiovascular risk in exposed offspring.

Oxidative stress, increased myocardial workload, altered glucose and lipid metabolism, and prolonged fetal hyperinsulinemia are considered the pathophysiological reasons for these cardiac changes. Excessive glucose transfer across the placenta leads to increased fetal insulin secretion, which is a growth factor for the heart that promotes septal and ventricular hypertrophy [

3,

4,

5]. At the same time, exposure to inflammatory and oxidative mediators may affect the cardiovascular risk that persists into infancy and adulthood, which is likely influenced by these intrauterine programming mechanisms [

1,

2].

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a hydrophilic bile acid that is used to treat intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), improving maternal symptoms and biochemical parameters and showing a safety profile. Beyond hepatoprotection, UDCA has antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and mitochondrial stabilizing properties [

6]

. In preclinical studies, UDCA has shown the ability to reduce myocardial fibrosis through TGR5 receptor signaling [

6], preserve mitochondrial integrity, and limit apoptosis in cardiomyocytes. These actions are enhanced by antiarrhythmic effects: UDCA restores T-type calcium currents, inhibits ventricular conduction slowing, and reduces arrhythmogenesis induced by cholestatic bile acids [

7,

8]. Importantly, UDCA also affects cardiac fibroblasts by stopping the remodeling of the extracellular matrix in a way that makes it less flexible, thereby contributing to improved myocardial compliance [

10].

Interestingly, UDCA has also been linked to cardioprotective effects. Experimental studies indicate that whilst taurocholic acid disrupts ventricular conduction and induces fetal arrhythmias in ICP, UDCA counteracts these effects by normalizing calcium currents and regulating myofibroblast activity [

7,

8]. Other studies have shown that fetuses from mothers with intrahepatic cholestasis have prolonged atrioventricular conduction intervals, which decrease following maternal UDCA therapy, particularly in severe cases [

9,

10].

Despite the impact of GDM on fetal cardiac function, no pharmacological interventions have yet been shown to decrease these effects. Considering the metabolic and circulatory effects of UDCA, this may be considered as a promising candidate for further research.

The aim of this study was therefore to evaluate the effect of UDCA compared with placebo on fetal cardiac function in pregnancies complicated by GDM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

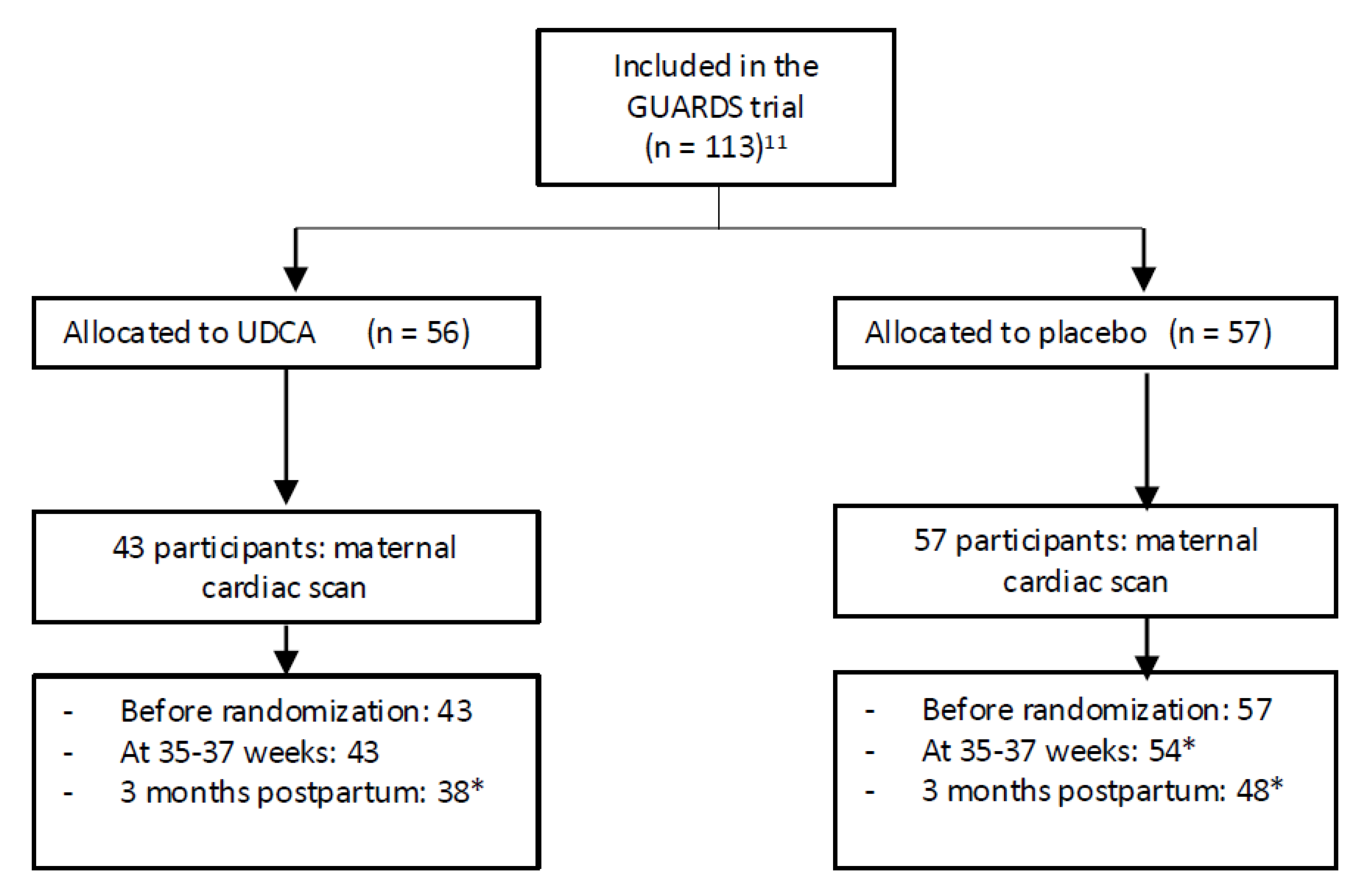

This prospective study was carried out within the GUARDS trial (a randomized, controlled trial of the impact of UDCA on glycemia in GDM) [

11]. This randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial (IMIB-GU-2019-02, date of registration 2020-06-17; date of the first participant enrolled: 2021-03-03) was performed at Clinic University Hospital “Virgen de la Arrixaca” in Murcia, Spain. Recruitment and eligibility data were reported in a CONSORT flow diagram (

Figure 1).

Adapted from Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D and CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. PLoS Med 2010; 7(3):e1000251.

Women with an abnormal oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) screen were offered participation between 24

+0 and 30

+6 weeks’ gestation. In Spain, the diagnosis of GDM involves a two-step screening process:Step 1: O’Sullivan Test—conducted between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. A 1-hour plasma glucose level ≥140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) after a 50 g glucose load is considered positive. Step 2: 100 g 3-hour OGTT—performed after an overnight fast. The diagnosis of GDM is confirmed if at least two of the following thresholds are met or exceeded:Fasting: ≥95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L); 1-hour: ≥180 mg/dL (10.0 mmol/L); 2-hour: ≥155 mg/dL (8.6 mmol/L); 3-hour: ≥140 mg/dL (7.8 mmol/L) [

1,

2].

Inclusion criteria were GDM diagnosed at 24–28 weeks’ gestation; planned antenatal care at the same center; singleton pregnancy; and ability to give informed and written consent. Exclusion criteria included age <18 years; previous diagnosis of diabetes outside of pregnancy; significant pre-pregnancy comorbidities that increase risk in pregnancy; and significant comorbidity in the current pregnancy.

After written informed consent, eligible women were randomly assigned to treatment with UDCA 500 mg twice daily or placebo until the time of delivery. In the present study, women that were allocated either to the UDCA group or placebo agreed to have a cardiac scan the day of randomization and before starting medication, at 35-37 weeks and 3 months postpartum.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Murcia (code 2018-11-5-HCUVA).

2.2. Maternal and Fetal Characteristics

We recorded information on maternal age, ethnic origin (White, Black, Asian, or mixed), method of conception (spontaneous or assisted by in vitro fertilization or ovulation induction drugs), cigarette smoking, and parity (parous or nulliparous if there was no previous pregnancy with delivery at ≥ 24 weeks of gestation). At every clinic visit, weight and height were measured and body mass index was calculated. At every visit, a prenatal ultrasonographic examination was performed to estimate fetal weight from measurements of fetal head circumference, abdominal circumference, and femur length (EPIQ Elite Philips, Bothell, WA, USA) [

12], and the values were converted to Z-scores based on the Fetal Medicine Foundation fetal weight chart [

13].

2.3. Fetal Cardiac Functional Analysis

Fetal cardiac functional measurements were performed at an ‘apex oblique’ projection with an angulation of at least 30° (EPIQ Elite Philips C5-1 or C9 transducer). Cardiac function was assessed using conventional Doppler. Fetal heart rate was calculated using spectral Doppler imaging of the aortic flow [

14]. Left ventricular outflow tract diameter (LVOTd) and peak aortic velocity (Ao Vmax) were obtained, and ejection time (ET) was measured from Doppler waveforms of aortic outflow. The left myocardial performance index (MPI) was calculated using pulsed-wave Doppler in a five-chamber view, with the sample volume including both aortic and mitral flows; valvular clicks in the Doppler waveforms were used as landmarks to define each time interval [

15]. Systolic function was evaluated by measuring tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) using M-mode and the isovolumetric contraction time (IVCT) from Doppler waveforms. Diastolic function was assessed by measuring peak early (E) and late (A) ventricular filling velocities across mitral valve, as well as the isovolumetric relaxation time (IVRT), using Doppler flow patterns. The E/A ratio was subsequently calculated [

14].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD if their distribution was normal or as median (interquartile range) if their distribution was non-normal. Normality of the distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Categorical variables were presented as n (%). Individual comparison between the placebo and treatment group at late third trimester and postpartum was performed using the t-test or Mann-Whitney U test.P-values are presented for the direct two-way comparisons between groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Linear mixed models were fitted to assess the effect of time and treatment on maternal cardiac indices after accounting for maternal characteristics. The statistical software package R was used for data analysis [

16].

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

In the current study, 113 patients were included, of whom 56 received UDCA and 57 received a placebo. After assessing the levels of UDCA in the maternal blood, 43 of the 56 had blood concentrations ≥0.5 µmol/L (consistent with having taken and absorbed the drug) and were included in the analysis.

There were no significant differences between groups with regard to participant characteristics and cardiac functional indices before randomization, with the exception of Ao_Vmáx. Individual comparisons between the placebo and treatment group are shown in Table 1 and Table 2.

3.2. Comparison of Cardiac Indices During the Study

Individual comparisons between the treatment and placebo groups at 36 weeks’ gestation and postpartum did not show significant differences in the cardiac indices (Table 2). However, in the multivariable analysis mixed models to account for differences in time and treatment, it appeared that MV-A and Ao_Vmáx increase over time in the treatment group and in the control group. However, this increase is more pronounced in the treatment group.

Specifically, there was a significant interaction for the MV-A between treatment and time in the postpartum period (9.58; p = 0.010). In addition, there was a significant interaction for the Ao_Vmáx between treatment and time in the postpartum period (7.97; p = 0.045).

3.3. Comments

Principal Findings

The findings of this randomized controlled trial suggest that ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) may exert a modest but specific effect on fetal and neonatal cardiac functional indices in pregnancies complicated by GDM. While cross-sectional comparisons at 36 weeks and postpartum did not reveal significant differences between groups, longitudinal mixed-model analysis demonstrated a significant treatment by time interaction postpartum: the UDCA group was associated with greater increases in mitral A-wave velocity (MV-A) and aortic peak velocity (Ao_Vmáx) in the postpartum period compared to placebo. These findings suggest that UDCA may have a selective effect on atrial contribution to ventricular filling and systolic outflow dynamics, rather than broad changes in global cardiac function.

3.4. Results in the Context of What We Know

Fetal Cardiac Changes in GDM

Multiple studies have shown that GDM is associated with subclinical remodeling—septal thickening, altered geometry (reduced global sphericity), and subtle functional changes (impaired diastolic relaxation; RV functional reduction), even when glycemia is apparently controlled. In the third trimester, Aguilera et al. demonstrated paired maternal–fetal alterations, including more globular fetal hearts and reduced global systolic performance, in the second and third trimesters [

3]. Yovera et al. reported reduced RV function and altered sphericity [

4], and in the second trimester, Huluta et al. identified early morphological changes preceding GDM diagnosis with largely preserved function [

5].

Our finding that MV-A increased more in UDCA-treated pregnancies suggests that UDCA affects late diastolic filling, an essential component of ventricular relaxation. This is especially important in GDM, where subtle impairments in diastolic function are common, and this supports the hypothesis that UDCA may modulate atrial–ventricular interplay during fetal cardiac adaptation. Significantly, our findings show that UDCA does not affect MPI or TAPSE, supporting the hypothesis that UDCA’s effects may be selective.

3.5. UDCA and the Fetal Heart

UDCA is widely used in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and has shown cardioprotective properties in both experimental and clinical contexts. Some studies have demonstrated that UDCA inhibits bile acid–induced conduction slowing, restores T-type calcium currents, and reduces arrhythmias in fetal heart models [

7,

8]. Clinical observations in ICP indicate that UDCA reduces fetal atrioventricular conduction intervals, especially in severe cases [

9]

. Vasavan et al. also showed that increased maternal bile acid levels in ICP were directly associated with fetal cardiac dysfunction, highlighting the distinct cardiotoxicity of bile acids [

17].

In line with this, our findings suggest that UDCA may also influence fetal diastolic filling (via MV-A) and systolic outflow (via Ao_Vmáx) in GDM pregnancies, rather than changes in conduction. The increase in Ao_Vmáx may improve forward stroke dynamics, while the rise in MV-A suggests greater atrial–ventricular coupling during adaptation. Recent findings by Chivers et al. further support that GDM pregnancies are associated with altered fetal heart rate and autonomic regulation, strengthening the concept that the fetal heart is functionally susceptible in this metabolic context [

18].

Differences in study populations (GDM vs. ICP), exposure patterns (hyperglycemia vs. elevated bile acids), and the specific endpoints evaluated (functional indices vs. conduction markers) likely explain why we did not observe MPI changes in our GDM cohort. This aligns with aggregate findings from Depla et al. who reported no MPI difference in GDM fetuses despite consistent signs of diastolic dysfunction [

19], and from Skovsgaard et al., which noted inconsistent MPI outcomes in neonatal cardiac studies of diabetic pregnancies [

20]. In contrast, cardiac dysfunction in ICP is more consistently manifested through conduction abnormalities and global indices such as MPI. This was observed by Vasavan et al., who proved that elevated maternal bile acid concentrations were directly associated with fetal cardiac dysfunction, particularly atrioventricular conduction disturbances

17. Zhan et al. also obtained the same results in his meta-analysis and reinforcing the evidence for a cardiotoxic effect of bile acids on the fetal heart [

21].

3.6. Clinical and Research Implications

The findings of this study suggest that UDCA may have a modest, time-dependent influence on fetal and neonatal cardiac function in pregnancies complicated by GDM, selectively affecting indices of atrial filling (MV-A) and systolic outflow (Ao_Vmáx). Although these effects were statistically significant, they were limited to specific parameters and were not accompanied by broader improvements in systolic or global function. Therefore, their clinical relevance remains uncertain.

From a clinical standpoint, the lack of negative impacts on cardiac function offers reassurance regarding the safety of UDCA administration in this population. Given that offspring of GDM pregnancies are more likely to have cardiac and metabolic disorders later in life, even small improvements in fetal cardiac function could be important, but this hypothesis requires validation. In addition, while studies in ICP have consistently shown that UDCA mitigates conduction abnormalities and reduces global dysfunction caused by elevated bile acids [

17,

21], our data suggest that in GDM, UDCA may act through different pathways, modulating functional Doppler indices rather than conduction. At present, our results should be interpreted as preliminary and not as evidence supporting clinical benefit. Larger and adequately powered longitudinal studies are needed to incorporate not only echocardiographic measures but also maternal metabolic and inflammatory markers to clarify potential mechanisms. Future work should explore whether UDCA’s effects in GDM reflect direct myocardial actions or indirect modulation via improved metabolic or vascular function and whether such selective changes can contribute to longer-term cardiovascular outcomes in affected offspring.

3.7. Strengths and Limitations

A major strength of this study is its randomized, placebo-controlled design, allowing the assessment of both systolic and diastolic performance. Compliance was carefully monitored by maternal blood UDCA concentrations, ensuring accurate per-protocol analysis. Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small, limiting statistical power. Second, the significant differences were confined to two indices (MV-A and Ao_Vmáx), while the majority of functional measures remained unchanged; this selective pattern raises uncertainty regarding the consistency and physiological significance of the findings. Third, echocardiographic indices, despite their sensitivity to functional changes, may not directly correlate with clinically significant outcomes, and the study was not powered to assess perinatal or long-term cardiovascular endpoints. Finally, the mechanisms underlying the observed associations remain unclear, and it is uncertain whether they reflect direct myocardial actions of UDCA or indirect effects mediated by maternal metabolic or vascular changes.

4. Conclusion

UDCA administration in mid-pregnancy to women with GDM was associated with selective increases in MV-A and Ao_Vmáx during late gestation and postpartum, while other functional indices remained unchanged. These results should be interpreted cautiously: the observed changes were modest, confined to specific parameters, and their clinical significance remains uncertain. Larger, longer-term studies are needed to confirm these findings, clarify underlying mechanisms, and determine whether such selective effects translate into meaningful clinical benefit.

Author Contributions

A.M.C.C., C.P.M., C.W., and M.C. conceived the study and, together with K.N., M.C., and J.B., designed it. Participant recruitment was carried out by C.P.M., J.B., and A.M.C.C., while M.C. and C.C. conducted the statistical analyses. The manuscript was drafted by M.C., CP.M., C.W., and K.N., and all authors critically reviewed, revised, and approved the final version.

Funding

The trial was supported by a grant from the Fetal Medicine Foundation (charity No. 1037116).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Murcia (protocol code 2018-11-5-HCUVA and date of 2019-07-22).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Catalina De Paco Matallana is a guarantor of this study, and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the women for their generosity in participating in this study. The ultrasound machines for fetal echocardiography and the software for speckle-tracking analysis were provided free-of-charge by Philips, Bothell, WA, USA. These bodies had no involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373:1773-1779.

- Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:1862-1868.

- Aguilera J, Semmler J, Coronel C, et al. Paired maternal and fetal cardiac functional measurements in women with gestational diabetes mellitus at 35–36 weeks’ gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;223:574.e1–574.e15.

- Yovera L, Zaharia M, Jachymski T, Velicu-Scraba O, Coronel C, de Paco Matallana C, Georgiopoulos G, Nicolaides KH, Charakida M. Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on fetal cardiac morphology and function: cohort comparison of second- and third-trimester fetuses. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:607-613.

- Huluta I, Wright A, Cosma LM, et al. Fetal Cardiac Function at Midgestation in Women Who Subsequently Develop Gestational Diabetes. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177:718–725.

- Reilly-O'Donnell B, Ferraro E, Tikhomirov R, Nunez-Toldra R, Shchendrygina A, Patel L, Wu Y, Mitchell AL, Endo A, Adorini L, Chowdhury RA, Srivastava PK, Ng FS, Terracciano C, Williamson C, Gorelik J. Protective effect of UDCA against IL-11- induced cardiac fibrosis is mediated by TGR5 signalling. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2024;11:1430772.

- Miragoli M, et al. A protective antiarrhythmic role of ursodeoxycholic acid in an in vitro rat model of the fetal heart. J Hepatol. 2011;54):792–798.

- Adeyemi O, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid prevents ventricular conduction slowing and arrhythmia by restoring T-type calcium current in the fetal heart. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0183167.

- Eyisoy ÖG, Demirci O, Taşdemir Ü, Özdemir M, Öcal A, Kahramanoğlu Ö. Effect of Maternal Ursodeoxycholic Acid Treatment on Fetal Atrioventricular Conduction in Patients with Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2024;51(6):617-623.

- Schultz F, Hasan A, Alvarez-Laviada A, Miragoli M, Bhogal N, Wells S, Poulet C, Chambers J, Williamson C, Gorelik J. The protective effect of ursodeoxycholic acid in an in vitro model of the human fetal heart occurs via targeting cardiac fibroblasts. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 2016 Jan;120:149-63.

- Matallana CP, Blanco-Carnero JE, Company Calabuig A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of the impact of ursodeoxycholic acid on glycemia in gestational diabetes mellitus: the GUARDS trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2025;101732.

- Hammami A, Mazer Zumaeta A, Syngelaki A, Akolekar R, Nicolaides KH. Ultrasonographic estimation of fetal weight: development of new model and assessment of performance of previous models. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018; 52: 35–43.

- Nicolaides KH, Wright D, Syngelaki A, Wright A, Akolekar R. Fetal Medicine Foundation fetal and neonatal population weight charts. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2018; 52: 44–51.

- Crispi F, Gratacós E. Fetal cardiac function: technical considerations and potential research and clinical applications. Fetal Diagn Ther 2012;32:47–64.

- Hernandez-Andrade E, López-Tenorio J, Figueroa-Diesel H, et al. A modified myocardial performance (Tei) index based on the use of valve clicks improves reproducibility of fetal left cardiac function assessment. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005;26:227–32.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Version 2.15.1. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria. Accessed July 2025. https://www.r-project.org/.

- Vasavan T, Deepak S, Jayawardane IA, Lucchini M, Martin C, Geenes V, Yang J, Lövgren-Sandblom A, Seed PT, Chambers J, Stone S, Kurlak L, Dixon PH, Marschall HU, Gorelik J, Chappell L, Loughna P, Thornton J, Pipkin FB, Hayes-Gill B, Fifer WP, Williamson C. Fetal cardiac dysfunction in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is associated with elevated serum bile acid concentrations. J Hepatol. 2021;74:1087-96.

- Chivers S, Ovadia C, Vasavan T, Lucchini M, Hayes-Gill B, Pini N, Fifer WP, Williamson C. Fetal heart rate analysis in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective multicentre observational study. BJOG. 2025;132:473-82.

- Depla AL, Delhaas T, Breur JMPJ, Mulder TA, Blom NA, van der Werf D, et al. Effect of maternal diabetes on fetal heart function on ultrasound and fetal echocardiography: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2021;57:539-49.

- Skovsgaard J, Haugaard M, Iversen KK, Hjortdal VE, Bech BH. Cardiac function in offspring of mothers with diabetes in pregnancy: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1404625.

- Zhan Y, Xu T, Chen T, Deng X, Kong Y, Li Y, Wang X. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and fetal cardiac dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2023;5:100952.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).