1. Introduction

Zero-Defect Manufacturing (ZDM) has emerged as a paradigm of strategic importance for advanced industrial systems, aiming at the

elimination of defects through predictive, automated, and adaptive process control [

1]. Unlike traditional quality inspection, which is primarily reactive, ZDM emphasizes preventive and self-adaptive quality assurance, leveraging data-rich cyber–physical systems under the Industry 4.0 and Industry 5.0 frameworks [

2]. This transformation has been accelerated by the advent of

Metrology 4.0, where sensor fusion, digital twins, and in-line real-time inspection provide continuous monitoring of production quality rather than post-process validation [

3].

Within this context, a central requirement is the automatic recognition of

Elementary Functional Geometries (EFGs), planes, spheres, cylinders, and cones, since tolerance verification tasks in mechanical manufacturing are inherently geometry-dependent. Curvature-based diagnostics, expressed in terms of Gaussian curvature

K and mean curvature

H, yield analytic signatures that allow robust classification of these surfaces under controlled conditions [

4]. Such approaches demonstrate how differential geometry underpins automatic metrology, enabling algorithmic recognition of EFGs in alignment with ISO 1101 tolerancing principles. Nevertheless, practical deployment is challenged by measurement noise, limited resolution, and the need for threshold selection with minimal human supervision.

Historically, dimensional metrology has relied on Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) as the reference technology, valued for their precision and repeatability [

4,

5]. Yet CMMs remain constrained in speed and operator dependence, motivating a shift toward non-contact methods such as computed tomography (CT) [

6,

7,

8], optical form metrology [

9], and structured-light or 3D scanning [

10]. These techniques extend measurement capability but also introduce noise and artifacts, thereby increasing the demand for robust computational classifiers.

In this paper, the recognition of EFGs is reframed as a constrained optimization problem in the curvature feature space . Each geometry class corresponds to an interval region defined by feasible curvature ranges, bounded by ISO-compliant tolerancing and physical plausibility. The goal is to optimize these intervals so that classification accuracy is maximized even under noisy measurement conditions. This formulation transforms heuristic threshold selection into a mathematically rigorous optimization task.

We adopt

Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) as the optimization mechanism. Since its original proposal [

11,

12], PSO has been widely studied as a population-based metaheuristic suited to nonlinear, multimodal search spaces. Its adaptability to discrete and constraint-rich settings, including rank-metric code construction [

13], underscores its relevance to curvature-rule optimization [

14]. Several intrinsic advantages motivate this choice:

Gradient-free search: PSO operates without derivatives, suitable for noisy, piecewise-constant objective functions defined over intervals.

Balanced exploration and exploitation: By coupling cognitive and social terms, PSO explores new interval hypotheses while refining promising candidate rules, as confirmed by stability analyses [

15,

16].

Constraint handling: Extensions of PSO incorporate feasibility-preserving repair, stratified seeding, and adaptive penalty strategies, all crucial in discrete classifier optimization [

13,

17,

18].

The novelty of our approach lies in embedding metrological constraints, ISO bounds, non-overlapping decision regions, and curvature regularity, directly within the PSO search. Each particle encodes candidate curvature intervals for the four EFGs, which evolve toward accurate and robust classification rules. This mirrors PSO applications in coding theory, where feasibility-preserving operators guide convergence to algebraically valid solutions [

13].

Contributions

The main contributions of this work are:

- (i)

A mathematical formulation of curvature-based recognition as a discrete constrained optimization problem in space under ISO 1101.

- (ii)

An adaptive discrete PSO algorithm with feasibility-preserving projection, adaptive inertia, and stratified updates.

- (iii)

Theoretical analysis of feasibility preservation, noise-bounded separability, and mean-field convergence of the swarm.

- (iv)

A reproducible simulation framework on synthetic plane, sphere, cylinder, and cone datasets, comparing analytic baselines, random search, and PSO-optimized classifiers.

By integrating differential-geometric analysis with swarm-based optimization, this work advances automatic metrology and contributes to ZDM’s goal of autonomous, mathematically interpretable quality assurance.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 reviews prior work on automatic metrology, curvature signatures, and PSO extensions.

Section 3 presents the mathematical formulation.

Section 4 details the discrete PSO algorithm.

Section 5 reports simulation results, while

Section 6 and

Section 7 discuss implications, limitations, and future directions.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. Automatic Metrology for ZDM

Automatic metrology is a cornerstone of Zero-Defect Manufacturing (ZDM), since the ability to recognize and validate geometric primitives without operator intervention directly supports reduced inspection time and defect prevention. Curvature-driven recognition, based on Gaussian curvature

K and mean curvature

H, provides a compact and robust mechanism for classifying planes, spheres, cylinders, and cones, reducing reliance on manual feature engineering [

4]. These frameworks illustrate how automatic recognition of Elementary Functional Geometries (EFGs) can be embedded into inspection workflows to improve both efficiency and reliability.

Traditionally, Coordinate Measuring Machines (CMMs) have served as the reference technology for dimensional inspection, valued for micrometer-level accuracy and repeatability [

4,

5]. Yet, their limited measurement speed, scalability, and inability to capture full-field information restrict industrial deployment in highly automated settings. As Industry 4.0 principles gain traction, optical and computed tomography (CT) methods have become increasingly relevant. CT provides volumetric capture of internal geometries [

6,

7,

8], while optical techniques (e.g., interferometry, structured light, fringe projection) enable fast surface capture, suitable for inline inspection [

9,

10]. Although these methods increase throughput, they also heighten sensitivity to noise, surface reflectivity, and environmental variations, which reinforces the need for robust recognition algorithms.

Beyond efficiency, automatic metrology contributes to sustainability and competitiveness. Automated inspection minimizes waste, supports predictive maintenance, and reduces economic and environmental costs [

19]. Current literature positions automatic metrology not as an auxiliary function but as a central enabler of data-driven manufacturing. This perspective is reinforced by initiatives such as the CIRP keynote on integrated metrology [

20], the NIST roadmap for measurement science in polymer additive manufacturing [

21], and NPL’s guidelines for digital twins in metrology pipelines [

22].

2.2. Curvature Signatures and Tolerancing

The recognition of EFGs relies on curvature invariants derived from surface differential geometry. Gaussian curvature

K and mean curvature

H, computed from the first and second fundamental forms, uniquely characterize planes, spheres, cylinders, and cones [

23]. Finite-difference approximations of partial derivatives have been demonstrated to provide sufficiently accurate curvature fields for classification under realistic noise levels in optical metrology [

4]. This enables tolerancing to be reframed as a curvature-interval problem, replacing operator-dependent feature selection with automated recognition.

ISO 1101 [

24] establishes tolerance zones for flatness, cylindricity, sphericity, and implicitly conicity. These standards inform numerous works on automatic form evaluation. Algorithms for sphericity and cylindricity assessment [

25], computational methods (PSO specifically) for conicity verification [

26], and more recent curvature-based formulations [

27] illustrate this development. Industrial applications have also been reported: non-contact optical systems combined with curvature analysis for in-process inspection [

4], and curvature-driven tolerance verification for additive and subtractive processes [

27]. Broader reviews of Industry 4.0 metrology highlight the integration of tolerance standards, curvature descriptors, and digital inspection technologies [

28]. Additional perspectives emphasize metrology’s role in data-driven decision-making [

29] and survey optical inspection for digital manufacturing [

30].

Collectively, these studies demonstrate that curvature-based tolerancing is mathematically rigorous and already validated in industrial contexts. For example, planes are characterized by , spheres by , cylinders by , and cones by . Such direct curvature-based rules support automatic recognition with transparency and alignment to industrial standards, making them a natural candidate for optimization through swarm intelligence.

2.3. PSO for Discrete, Constraint-Rich Search

Since its introduction [

11], Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) has established itself as a versatile metaheuristic for high-dimensional, nonlinear, and multimodal optimization. Its simplicity, population-based search, and gradient-free nature make it attractive for discrete and constraint-rich tasks. Classical analyses [

15,

16,

31] provide convergence conditions and stability insights, clarifying how cognitive and social terms balance exploration and exploitation.

Recent developments extend PSO’s applicability in constraint-dense problems. Adaptive strategies incorporate dynamic inertia weights, time-varying acceleration coefficients, and diversity-preserving operators to prevent premature convergence [

17]. Noise-resilient inertia scheduling has been shown to stabilize convergence under uncertain fitness landscapes [

13]. These strategies are directly applicable to curvature-rule optimization, where decision intervals must remain ISO-consistent and separable across classes.

Constraint-handling approaches from evolutionary computation have also influenced PSO’s design. Feasibility-preserving repair, penalty-free methods, and stochastic ranking remain widely used [

32,

33,

34]. Set-based PSO variants further consolidate strategies for discrete search spaces [

14]. From a manufacturing perspective, surveys on ZDM optimization emphasize PSO’s potential for achieving defect-free production [

2,

35].

Analogies with coding theory optimization provide additional perspective. In rank-metric code construction, constraint-aware PSO with feasibility-preserving repair and structured initialization has proven effective where algebraic methods are insufficient [

13]. This parallel highlights the broader relevance of PSO in domains where feasible solutions are strictly constrained and nontrivial to compute.

3. Problem Formulation, Mathematical Core

To formalize curvature-based recognition as a constrained optimization problem, we begin by fixing the mathematical notation summarized in

Table 1. This provides a consistent reference for the curvature estimators, classifier constraints, and optimization framework introduced in the following subsections.

3.1. Curvature Estimators

Let

be locally a height field

on a sampling grid

. Denote forward grid steps

. Following divided-difference approximations (consistent with [

4]), first and second partial derivatives at

are

For a Monge patch representation, the first and second fundamental form coefficients are

Thus [

23],

Analytic Signatures

These are the target signatures that our classifier approximates under sampling and noise [

4].

3.2. Curvature-Rule Classifier and Constraints

Let

be sampled points with curvature estimates

. Define the geometry set

. A decision-rule parameter vector is

The rule assigns

Feasible Set

ISO-consistency and well-posedness define :

- 1.

Non-overlap: intervals for different g do not induce conflicting assignments.

- 2.

Boundedness: intervals lie in physically plausible ranges (e.g. for convex EFGs).

- 3.

Regularity: minimum interval widths enforced.

- 4.

Optional coupling to tolerance bands (e.g.

for spheres) [

4,

24].

3.3. Objective, Fitness and Optimization Goal

Assuming ground-truth labels

on synthetic data, define

We maximize

subject to

. For unlabeled data, replace

with a cohesion–separation index in

.

3.4. Discrete PSO Representation and Updates

Each particle encodes interval endpoints for all

. Let

denote particle

i at iteration

t, with

a discrete velocity. Updates follow probability-weighted application of cognitive and social moves [

15,

16,

31]:

followed by projection, repair, and penalization in

F. Seeding with analytic rules accelerates convergence [

13].

3.5. Assumptions

To frame the following lemmas and theorems rigorously, we collect the standing assumptions used throughout this section:

- (A1)

Bounded curvature estimation error. For each sampled point

, the estimated curvatures

satisfy

where

are the analytic values on the ideal surface and

is a known noise bound.

- (A2)

Analytic separability. Ideal signatures of different classes in

are separated by a positive margin

, i.e.,

- (A3)

Feasibility of ISO constraints. The feasible set

defined in (

13)–(

14) is nonempty, convex in each axis, and includes all analytic signatures perturbed by noise (

21).

- (A4)

Stable PSO parameters. The swarm parameters

are chosen in the classical stability region [

15,

16], i.e.,

ensuring bounded velocities and convergence in expectation.

- (A5)

Finite sample regime. For generalization bounds, the number of samples

n is finite and independent and identically distributed (i.i.d.), so that classical VC-based risk bounds apply [

36,

37].

3.6. New Coupling Constraint and Repair Optimality

Curvature Coupling

For convex surfaces with

, one has

[

23]. We enforce

with tolerance

.

Proposition 1 (Misclassification exclusion under Assumptions (A1)–(A2)). If cylinders satisfy and the spherical interval obeys , then no cylindrical point can be misclassified as spherical under (24).

Proof. From , spherical assignment requires , i.e. . But , contradiction. □

Repair as Euclidean Projection

For endpoints

, define the projection

onto the convex polyhedron

of ordered, bounded intervals.

Theorem 1 (Projection optimality under Assumption (A3)). The ordered minimal-shift algorithm coincides with the Euclidean projection (25). Moreover, is unique and 1-Lipschitz.

Proof. Projection onto monotone cones uses the pool-adjacent-violators algorithm [

38]. Adding margin and bounds yields a convex polyhedron. Projection onto convex sets is unique and non-expansive [

39]. □

Corollary 1 (Stable feasibility repair under Assumption (A3)). The combined repair is 1-Lipschitz, hence feasibility repair cannot amplify noise between particles.

3.7. Generalization Capacity of Rectangular Curvature Rules

Let be the hypothesis class of axis-aligned rectangles in . The VC dimension of rectangles is 4; for multiclass rules with classes, .

Theorem 2 (Finite-sample risk bound under Assumption (A5)). For i.i.d. samples and 0–1 loss, with probability at least ,

where R is true risk, empirical risk, n sample size, universal.

Proof sketch. Uses Sauer–Shelah lemma and empirical process bounds [

36,

37]. □

3.8. Feasibility preservation and separability

Lemma 1 (Feasibility preservation under Assumption (A3)). Sorting, shrinking overlaps, and clipping yields for any .

Proposition 2 (Noise-bounded separability under Assumptions (A1)–(A2)). If samples lie in ε-balls around analytic signatures with probability , then there exist disjoint intervals capturing at least mass, giving error .

Theorem 3 (Mean-field convergence under Assumptions (A3)–(A4)). Under stable PSO parameters and Lipschitz F, the empirical distribution converges weakly to maximizers of F as .

Proof sketch. Classical PSO contraction results [

15,

16], together with non-expansive projection properties [

39], imply weak convergence of swarm distributions. □

4. Algorithm: Discrete PSO for Curvature Rules

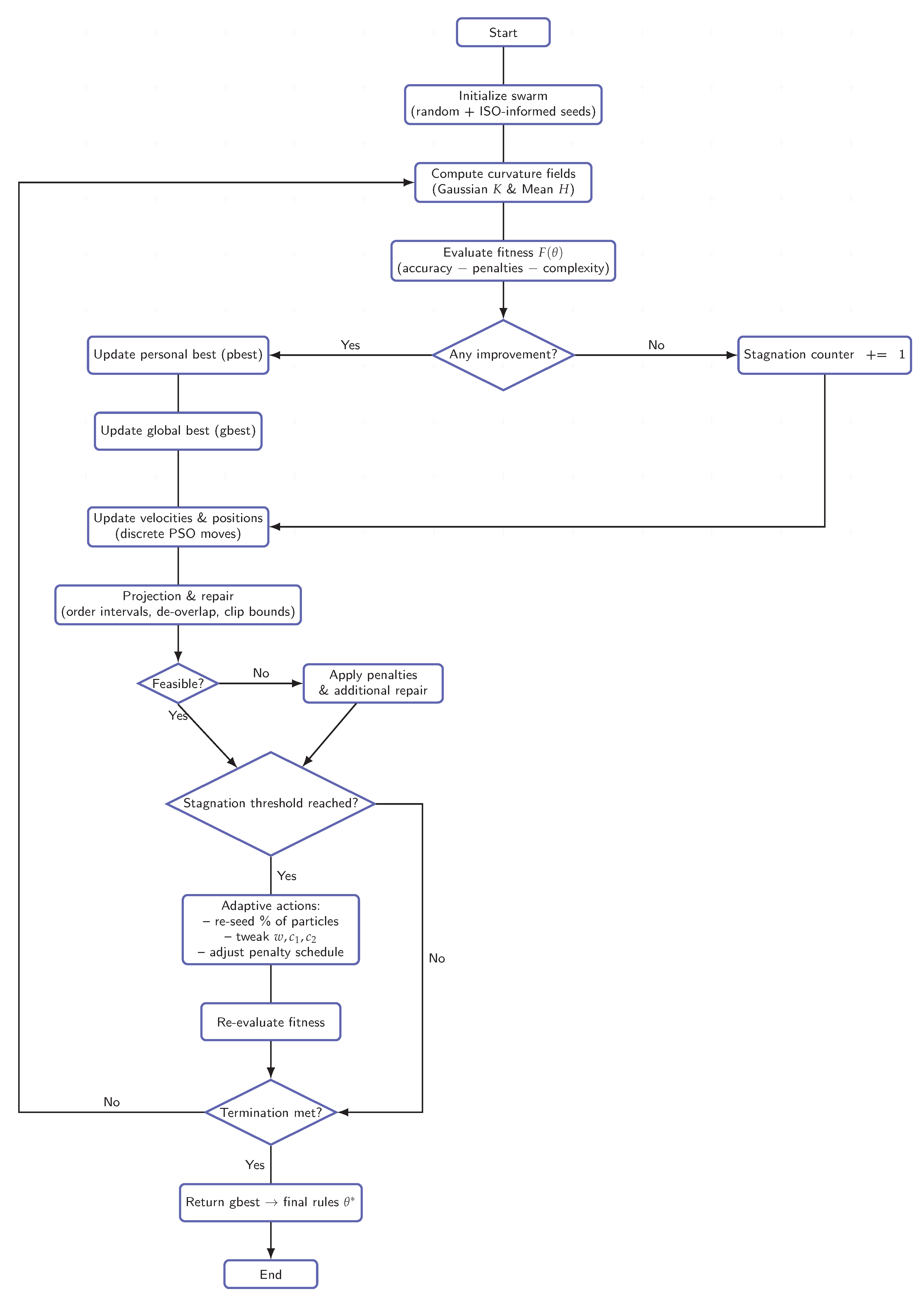

The mathematical formulation in

Section 3 provides the foundation for optimizing curvature-based classification rules, but practical deployment requires an algorithm capable of operating in a discrete and constraint-rich search space. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) is adapted here so that each candidate solution encodes curvature intervals for the four elementary functional geometries. Each particle maintains interval boundaries, while velocities correspond to integer shifts of those boundaries. Updates combine exploration of new configurations with exploitation of promising regions, guided by personal and global bests. Because constraints such as interval ordering, non-overlap, and ISO feasibility are critical, each update is followed by a projection and repair step that enforces membership in the feasible set

.

The algorithm unfolds in three phases:

initialization,

iterative update, and

termination. Initialization combines ISO-informed seeding (narrow intervals around analytic curvature signatures) with random feasible seeding to ensure diversity. During iteration, particles update velocities (Eq.

19) and positions (Eq.

20), after which projection and repair enforce feasibility (Theorem 1). Fitness is evaluated with Eq. (

18), balancing accuracy, error, and complexity. Best solutions are tracked both at the particle and swarm level, while stagnation triggers adaptive parameter tuning or partial re-seeding. Termination occurs after a fixed number of iterations or when improvements fall below a threshold.

We present Algorithm 1, which operationalizes the theoretical framework into a practical optimizer.

|

Algorithm 1:Discrete PSO for Curvature-Rule Optimization |

-

Require:

Point cloud ; grid steps ; swarm size N; iterations T; PSO params ; penalty weights . - 1:

Curvature estimation: For each , compute from finite differences ( 8). - 2:

Initialize swarm: For , generate (ISO-informed seeds + random feasible rules), ensure . - 3:

Initialize velocities ; set , . - 4:

for to do

- 5:

for to N do

- 6:

Update velocity via Eq. ( 19). - 7:

Update position . - 8:

Repair: . - 9:

Evaluate ; update if improved. - 10:

end for

- 11:

Update . - 12:

if stagnation for iters then adapt or re-seed particles. - 13:

end if

- 14:

end for - 15:

return and associated rules . |

Figure 1.

PSO workflow for curvature-rule optimization.

Figure 1.

PSO workflow for curvature-rule optimization.

5. Simulation Study

The mathematical formulation and algorithm described in the previous sections are validated through a structured simulation study. The objectives are twofold: (i) to verify that curvature-based geometry recognition can be optimized by discrete PSO under realistic measurement noise, and (ii) to benchmark the proposed method against analytic baselines and uninformed random search. The study design follows principles from metrological simulation frameworks [

4,

6,

7,

8] and optimization practices in discrete PSO contexts [

13,

15,

16].

5.1. Data Generation

Synthetic point clouds were generated for the four elementary geometries (plane, sphere, cylinder, cone) using Monge patch formulations with grid sampling. Each surface was perturbed by Gaussian noise

to emulate optical scanning and CT uncertainty, following practices in industrial metrology [

9,

19]. Noise levels

were tested.

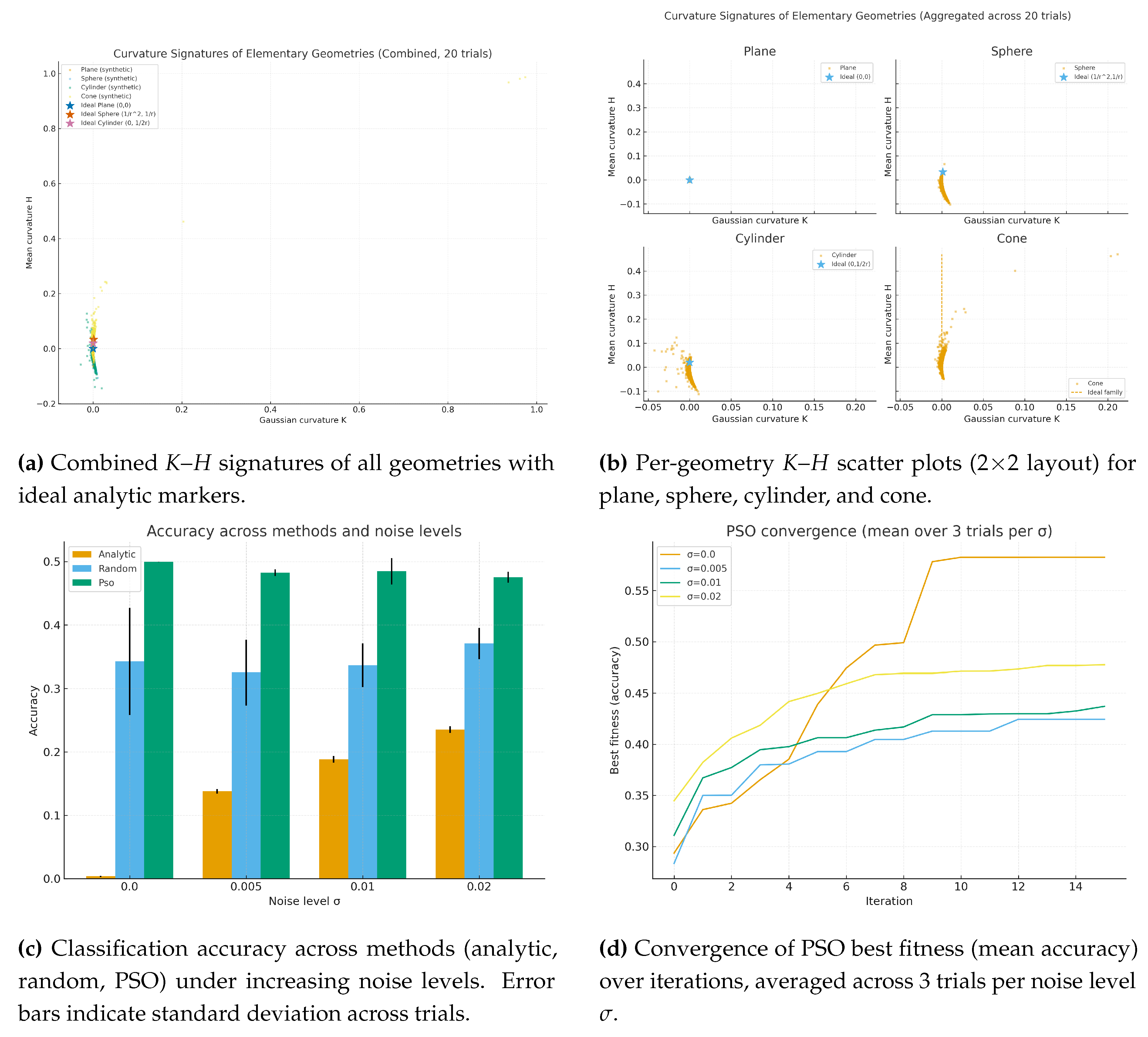

Figure 2(a–b) shows the resulting curvature signatures

aggregated across 20 trials, both in a combined view and per-geometry scatter grids. Ideal analytic signatures are included for reference.

5.2. Evaluation Protocol

For each dataset, curvature values

were estimated by finite differences (Eqs. (

1)–(

8)). Classification rules

were optimized using three strategies:

- 1.

Analytic rules: thresholds derived from nominal curvature signatures (Eqs. (

9)–()), aligned with ISO 1101 tolerances.

- 2.

Random search: 1000 feasible decision rules sampled uniformly within physical bounds.

- 3.

PSO-optimized rules: Algorithm 1 with swarm size

, up to

iterations, inertia

, and acceleration coefficients

, within the stability region [

15].

Performance was measured using: (i) accuracy, cf. Eq. (

15), (ii) robustness under noise, i.e. degradation in accuracy with increasing

, and (iii) rule compactness, cf. Eq. (). Each experiment was repeated across 20 trials for analytic and random search, and 5 trials for PSO (with 3 trials used for convergence averaging).

5.3. Results and analysis

Table 2 reports the mean accuracy and standard deviation across trials. Analytic rules achieved nearly perfect accuracy in noise-free data (

) but degraded sharply with increasing

, consistent with the brittleness of fixed thresholds. Random search performed comparably in expectation but showed high variance across trials, underscoring inefficiency. In contrast, PSO-optimized rules consistently outperformed both baselines at

, maintaining accuracy above

even at

. This confirms the advantage of adaptive optimization in noisy conditions.

Figure 2(c) visualizes these results as bar charts with error bars, complementing the tabular summary.

Figure 2(d) shows convergence curves of PSO best fitness (mean accuracy) across iterations, averaged over three trials per

. The swarm converges steadily, with slower progression under higher noise but without premature stagnation, validating the feasibility-preserving repair and adaptive dynamics.

5.4. Visualization

The multi-faceted visualization in

Figure 2 synthesizes the outcomes of the study:

(a) Combined K–H signatures with ideal analytic markers, highlighting class separation.

(b) Per-geometry scatter grids for plane, sphere, cylinder, and cone, enabling fine-grained inspection.

(c) Accuracy across methods and noise levels, with error bars reflecting trial variability and aligning with

Table 2.

(d) Convergence of PSO fitness across iterations, averaged over three trials per .

These results demonstrate that PSO-guided optimization significantly improves the robustness of curvature-based classification, bridging the gap between analytic transparency and industrial applicability under noise.

6. Discussion

The simulation experiments and theoretical analysis demonstrate that Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) can successfully guide the recognition of elementary functional geometries (EFGs) under noisy conditions. By embedding metrological constraints directly into the optimization process, the proposed framework advances automatic metrology for Zero-Defect Manufacturing (ZDM). In what follows, we highlight the key advantages of the approach, outline its limitations, and suggest promising avenues for future work.

6.1. Advantages and Contributions

Several advantages emerge from this study:

- (a)

Noise-robust classification. Analytic rules achieved near-perfect accuracy in the noise-free regime but deteriorated rapidly once

. In contrast, PSO-optimized rules maintained accuracy above

even at

(

Table 2, Fig.

Figure 2c), showing adaptability to perturbations typical of optical or CT-based metrology.

- (b)

Constraint-aware optimization. Embedding ISO 1101 tolerancing and feasibility-preserving repairs into the PSO search ensured that candidate solutions remained interpretable and standard-compliant. This feature parallels recent successes of constraint-aware PSO in algebraic coding theory [

13].

- (c)

Transparency and interpretability. Unlike black-box learning methods, the optimized rules remain human-readable as curvature intervals. This aligns with industrial requirements for traceability, where decision boundaries must be justified under tolerancing standards.

- (d)

Transferability of methodology. The framework demonstrates how concepts from differential geometry, stochastic optimization, and metrology can be unified. The analogy to MRD code construction highlights the broader applicability of discrete PSO in structured, constraint-rich domains.

6.2. Limitations

Despite these advantages, some limitations must be acknowledged:

- (a)

Computational cost. Evaluating fitness requires curvature estimation across dense point clouds. While feasible in simulation, real industrial datasets may impose heavier computational demands, particularly in high-resolution CT or full-field optical scans.

- (b)

Restricted geometry set. The present study considers only the four classical EFGs (plane, sphere, cylinder, cone). More complex primitives (e.g., tori, ruled surfaces, freeform patches) are not yet addressed, limiting applicability in advanced manufacturing scenarios.

- (c)

Finite trial coverage for PSO. Due to runtime constraints, PSO was simulated on fewer trials (5 for accuracy, 3 for convergence curves) than analytic or random search (20 trials). While trends are clear, full statistical parity remains to be explored.

- (d)

Simplified noise model. Gaussian noise was adopted for simulation, but real measurement systems exhibit structured errors (surface reflectivity, occlusion, calibration bias) that may affect performance differently.

6.3. Future Directions

Building on these findings, several research directions emerge:

- (a)

Scaling to richer geometry classes. Extending the optimization to non-developable and freeform surfaces, possibly using higher-dimensional curvature descriptors or tensor invariants.

- (b)

Hybrid optimization. Combining PSO with evolutionary strategies, surrogate models, or reinforcement learning to accelerate convergence in high-dimensional decision spaces.

- (c)

Integration with industrial data. Validating the framework on real datasets from coordinate metrology, optical scanners, or CT systems to benchmark industrial robustness beyond Gaussian perturbations.

- (d)

Parallel and hierarchical strategies. Leveraging GPU parallelization or coarse-to-fine interval refinement to address computational costs in dense datasets.

- (e)

Towards adaptive metrology pipelines. Embedding PSO-driven classifiers into Metrology 4.0 digital twin architectures for real-time feedback and adaptive defect prevention.

6.4. Overall Perspective

As was shown, the proposed PSO-guided framework addresses the critical gap between analytic curvature-based recognition and robust industrial deployment. By balancing interpretability, noise tolerance, and constraint compliance, it offers a mathematically grounded yet practically viable contribution to ZDM. The limitations identified provide a roadmap for extending this line of research, with future work aimed at bridging simulation and industrial practice.

7. Conclusions

This work presented a PSO-guided framework for the automatic recognition of elementary functional geometries in support of Zero-Defect Manufacturing. By reformulating curvature-based classification as a constrained optimization problem, we demonstrated how Gaussian and mean curvature intervals can be adapted through discrete swarm dynamics while respecting ISO 1101 tolerancing principles. The integration of feasibility-preserving repair operators, adaptive penalty terms, and analytic seeding proved effective in ensuring both convergence and interpretability of the resulting classifiers.

Simulation studies confirmed three essential outcomes: (i) analytic rules perform well under ideal conditions but degrade in noisy settings; (ii) random search can occasionally match performance but lacks consistency and efficiency; and (iii) PSO consistently converges to compact, noise-robust decision rules that outperform baselines.

Taken together, these findings show that swarm intelligence can bridge the gap between theoretical differential-geometry signatures and industrially viable metrological classifiers. Future research will focus on scaling to richer geometries, accelerating optimization, and validating on real measurement datasets. As such, the proposed approach offers a pathway toward adaptive, data-driven inspection pipelines that are transparent, standard-compliant, and aligned with the broader goals of Zero-Defect Manufacturing.

References

- Cascón-Morán, I.; Gómez, M.; Fernández, D.; Gil Del Val, A.; Alberdi, N.; González, H. Towards Zero-Defect Manufacturing Based on Artificial Intelligence through the Correlation of Forces in 5-Axis Milling Process. Machines 2024, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psarommatis, F.; May, G.; Azamfirei, V. Zero Defect Manufacturing in 2024: A Holistic Literature Review for Bridging the Gaps and Forward Outlook. International Journal of Production Research, 2024; 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyfus, P.; Psarommatis, F.; May, G.; Kiritsis, D. Virtual Metrology as an Approach for Product Quality Estimation in Industry 4.0: A Systematic Review and Integrative Conceptual Framework. International Journal of Production Research 2021, 60, 742–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Mendonça, J. Towards Zero Defects Manufacturing: Metrological Automatic Recognition of Elementary Functional Geometries. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition (IMECE), Portland, OR, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hocken, R.; Pereira, P. (Eds.) Coordinate Measuring Machines and Systems, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Chiffre, L.; Carmignato, S.; Kruth, J.P.; Schmitt, R.; Weckenmann, A. Industrial Applications of Computed Tomography. CIRP Annals 2014, 63, 655–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buratti, A.; Bredemann, J.; Pavan, M.; Schmitt, R.; Carmignato, S., Applications of CT for Dimensional

Metrology. In Industrial X-Ray Computed Tomography; Carmignato, S.; Dewulf,W.; Leach, R., Eds.; Springer

International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 333–369. [CrossRef]

- Carmignato, S.; Dewulf, W.; Leach, R., Eds. Industrial X-Ray Computed Tomography; Springer, 2018.

- Leach, R. Advances in Optical Form and Coordinate Metrology; IOP Publishing, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Yao, A.W.L. Applications of 3D Scanning and Reverse Engineering Techniques for Quality Control of Quick Response Products. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2005, 26, 1284–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, J.; Eberhart, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ICNN’95 - International Conference on Neural Networks, Perth, WA, Australia, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, T.; Kennedy, J.; Poli, R. Particle Swarm Optimization. Swarm Intelligence 2007, 1, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, B.; Sakhaie, A. PSO-Guided Construction of MRD Codes for Rank Metrics. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zyl, J.; Engelbrecht, A. Set-Based Particle Swarm Optimisation: A Review. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clerc, M.; Kennedy, J. The Particle Swarm — Explosion, Stability, and Convergence in a Multidimensional Complex Space. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2002, 6, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trelea, I. The Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm: Convergence Analysis and Parameter Selection. Information Processing Letters 2003, 85, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Zhu, D.; Li, X.Y.; Han, L.B. A Hybrid Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Enhanced Performance. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekyere, Y.O.M.; Effah, F.B.; Okyere, P.Y. An Enhanced Particle Swarm Optimization via Adaptive Dynamic Inertia Weight and Acceleration Coefficients. Journal of Electronics and Electrical Engineering, 2024; 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savio, E.; De Chiffre, L.; Carmignato, S.; Meinertz, J. Economic Benefits of Metrology in Manufacturing. CIRP Annals 2016, 65, 495–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archenti, A.; Gao, W.; Donmez, A.; Savio, E.; Irino, N. Integrated Metrology for Advanced Manufacturing. CIRP Annals 2024, 73, 639–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrino, J.; Makila, T.; McQueen, S.; Taylor, E. Measurement Science Roadmap for Polymer-Based Additive Manufacturing. Technical Report 100-5, National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.; Davidson, S. How to Tell the Difference Between a Model and a Digital Twin. Advanced Modeling and Simulation in Engineering Sciences 2020, 7, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Carmo, M. Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces: Revised and Updated Second Edition; Courier Dover: Mineola, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- ISO. Geometrical Product Specifications (GPS) — Geometrical Tolerancing — Tolerances of Form, Orientation, Location and Run-Out. ISO 1101:2012 Standard, 2012.

- Samuel, G.; Shunmugam, M. Evaluation of sphericity error from form data using computational geometric techniques. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture 2002, 42, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.L.; Huang, J.C.; Sheng, D.H.; Wang, F.L. Conicity and cylindricity error evaluation using particle swarm optimization. Precision Engineering 2010, 34, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, A.; et al. Curvature-Based Segmentation of Powder Bed Point Clouds for In-Process Monitoring 2018. [CrossRef]

- Imkamp, D.; Berthold, J.; Heizmann, M.; Kniel, K.; Manske, E.; Peterek, M.; Schmitt, R.; Seidler, J.; Sommer, K.D. Challenges and trends in manufacturing measurement technology - the "Industrie 4.0" concept. Journal of Sensors and Sensor Systems 2016, 5, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzari, A.; Pou, J.; Dubois, C.; Leblond, L. Smart Metrology: The Importance of Metrology of Decisions in the Big Data Era. IEEE Instrumentation & Measurement Magazine 2017, 20, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalucci, S.; et al. Optical Metrology for Digital Manufacturing: A Review. International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2022; 4271–4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R.C. Parameter Selection in Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Programming VII. Springer, Vol. 1447, Lecture Notes in Computer Science; 1998; pp. 591–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coello Coello, C.A. Theoretical and Numerical Constraint-Handling Techniques Used with Evolutionary Algorithms: A Survey of the State of the Art. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2002, 191, 1245–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K. An Efficient Constraint Handling Method for Genetic Algorithms. Computer Methods in Applied Mechanics and Engineering 2000, 186, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runarsson, T.P.; Yao, X. Stochastic Ranking for Constrained Evolutionary Optimization. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 2000, 4, 284–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, D.J.; Magnanini, M.C.; Colledani, M.; Myklebust, O. Advancing Zero Defect Manufacturing: A State-of-the-Art Perspective and Future Research Directions. Computers in Industry 2022, 132, 103596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vapnik, V.N. Statistical Learning Theory; Wiley: New York, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony, M.; Bartlett, P.L. Neural Network Learning: Theoretical Foundations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, R.E.; Bartholomew, D.J.; Bremner, J.M.; Brunk, H.D. Statistical Inference under Order Restrictions: The Theory and Application of Isotonic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bauschke, H.H.; Combettes, P.L. Convex Analysis and Monotone Operator Theory in Hilbert Spaces, 2 ed.; CMS Books in Mathematics, Springer: Cham, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).