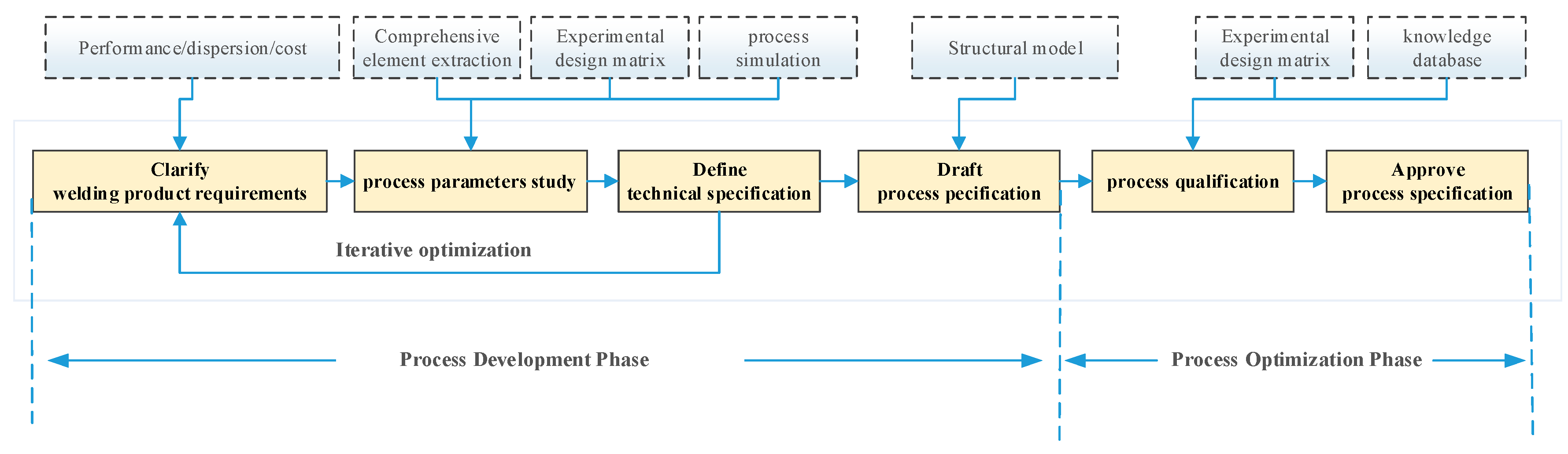

In the production process of welded products, the variety of welding structures and materials is extensive, and the welding requirements for each type differ. Welding process parameters often need to be determined through extensive repetitive experiments. This section, based on aviation product requirements and trade-off design, analyzes the process flows and elements affecting product quality, efficiency, and cost. It employs a forward-design approach that integrates product design and process considerations across the entire workflow, combining simulation theory with practical production experience. By mining data according to a pre-designed process specification structure model, process knowledge is generated. Data-driven analysis is used to identify key elements and indicator ranges that impact product requirements. Combined with process development activities and batch production task needs, quantifiable and measurable technical indicators are generated to meet actual processing and production demands.

2.1. Comprehensive Element Analysis of the Structural Model Based on Requirement-Driven and Trade-Off Design

With the increasing demands for forward design in aviation products, higher requirements are placed on the formation of manufacturing processes and process specifications. Process specification design now gradually considers the shared needs of both design and manufacturing parties. It should not only achieve high product quality but also provide confidence intervals and dispersion metrics for product quality and performance. While ensuring stable control of the production process, it must also meet economic requirements. The dispersion of product performance is closely related to human, machine, material, method, environment, and measurement factors, particularly process methods, process parameters, and production process control. Therefore, adopting scientific and rational process specifications significantly impacts the trade-off design and safety of aviation products.

Achieving forward design requires balancing the needs of both design and manufacturing to reasonably formulate welding process specifications. Trade-off design is the core of forward design, with quantification as its goal. From the design perspective, it is essential to clarify the performance of welded products and consider the manufacturing costs across the entire industry chain. From the manufacturing perspective, the focus should be closely aligned with welding product requirements, conducting manufacturability-oriented design, and defining the quality of welded products and the reliability of the welding process. Thus, based on the requirements of design and manufacturing and trade-off design, this study defines the objectives of welding process specifications, including welding product performance, reliability, and economy.

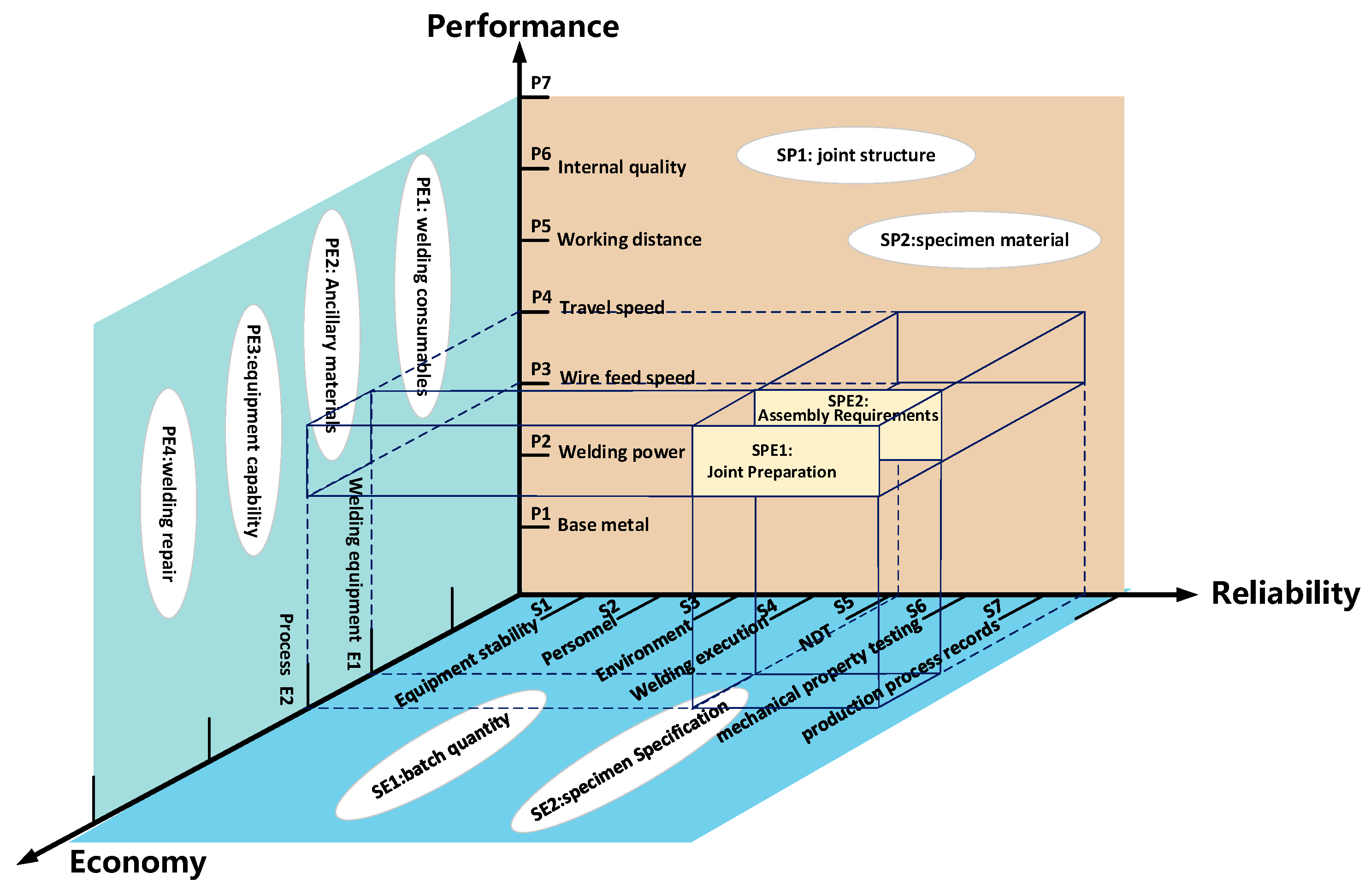

Figure 1 illustrates the comprehensive elements and quantification methods corresponding to each objective.

Figure 1 illustrates three coordinate axes representing the three objectives of product performance, economy, and reliability. The coordinate axes and points in different regions represent distinct elements.

In the product performance dimension, the requirements for the welded product, i.e., the design requirements are first determined. Through research and analysis, the quantitative indicators of product performance are primarily mechanical properties. Performance is related to the technical elements of the process specification, and the parameter values of these elements influence the final product performance. Key elements affecting product performance include base material requirements, welding consumables requirements, ancillary material requirements, joint structure, pre-weld joint requirements, assembly requirements, Travel speed, wire feed speed, welding power, working distance, defect types, appearance, internal quality, stress relief, and welding repair. Since welding is a special process, during the process development stage, the mapping relationship between the appearance, internal quality, and mechanical properties of welded joints is established through specimen and component tests to determine the parameter values for welding production and processing.

In the reliability dimension, under the premise of meeting the performance requirements of the welded product, the dispersion coefficient (Cv ) of the product performance is used to quantify the reliability of the welding process, which is also a core indicator of forward design. During the process development stage, experiments are conducted to determine the dispersion of product performance and identify its main influencing factors. The stability of the welding process is enhanced as much as possible through production control. Technical elements affecting dispersion primarily include equipment stability, joint structure, pre-weld joint requirements, assembly requirements, specimen specifications, specimen materials, batch quantity, personnel requirements, production environment, welding execution, non-destructive testing, mechanical performance testing, and production process records.

In the economy dimension, economy is considered from both the design and manufacturing perspectives, ensuring that the performance of the welded product is met while also accounting for manufacturing economy. Excessively stringent technical requirements for components to be welded inevitably increase production costs. Scientific experimental methods aim to determine stable process parameters with as few samples as possible, reducing the number of tests. Modular and parametric process specifications are rationally designed to enable parameter inheritance for similar products, effectively reducing the number of tests and associated costs. Thus, key elements affecting economy include welding consumables requirements, ancillary material requirements, equipment capability, pre-weld joint requirements, assembly requirements, batch quantity, and specimen specifications. For example, some current standards regarding equipment process qualification do not specify the batch, specifications, or structural types of test pieces, which hinders the qualification of equipment process capability and the determination of process parameters during implementation. Therefore, experimental methods should be designed early to solidify welding process requirements, providing support for subsequent welding processes and ensuring the operability and inheritability of welding process specifications. This approach meets design requirements while reducing welding production costs.

2.2. Composition of the WPS Structure Model

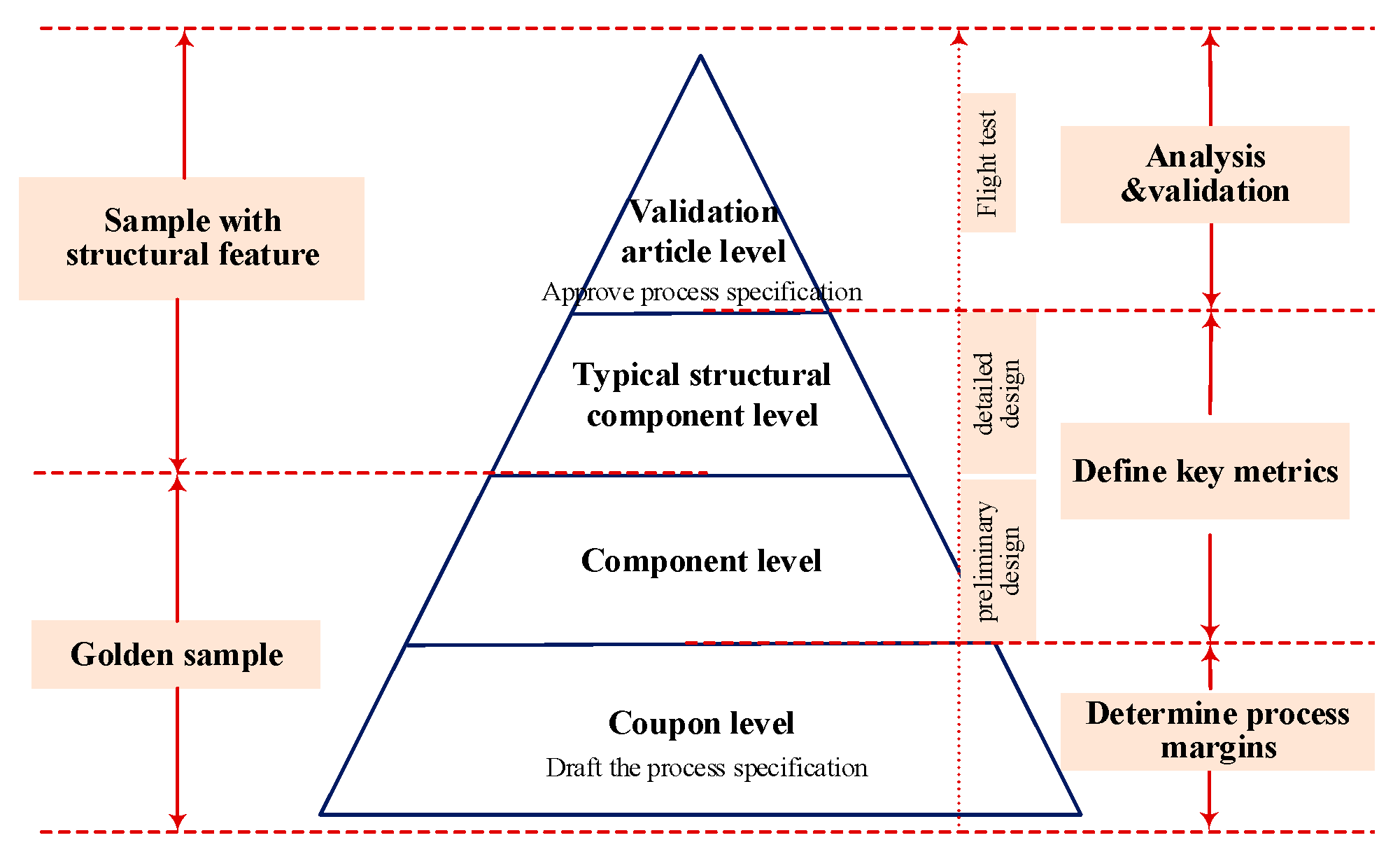

To address the requirements of aviation welded products in terms of performance, reliability, and economy, a structured model for aviation welding process specifications has been developed based on the principles of comprehensiveness, modularity, serialization, and parameterization. This model is designed to support the formation and optimization of welding process specifications.

The welding process specification structure model studied in this paper primarily consists of three layers: structure, technical elements, and semantics, as illustrated in

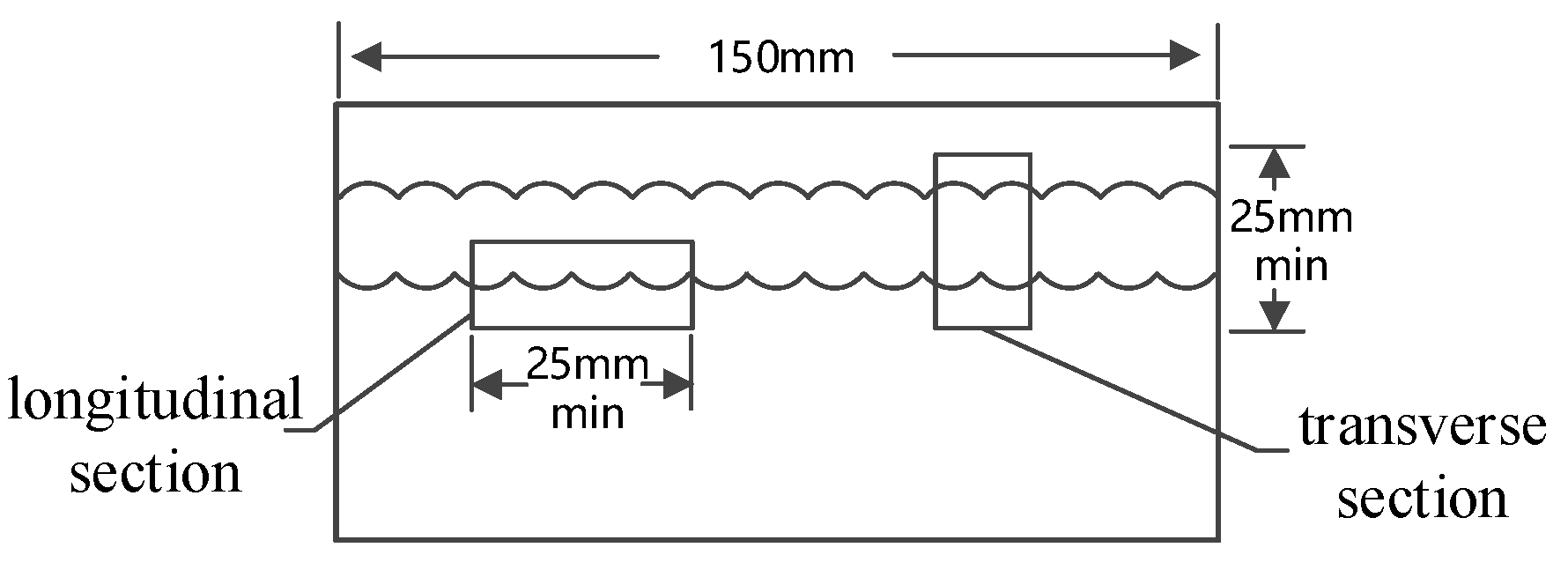

Figure 2. The model structure comprises six modules and eight submodules, with the eight submodules being reconfigured to form the six modules. The modules include personnel, environment, materials, equipment and tooling, process control, and quality control. The submodules cover eight aspects: material control, equipment control, process design, experimental design, parameter determination, production control, quality requirements, and inspection methods.

Technical elements refer to the content at the technical level under each submodule. The material control submodule includes requirements for base materials, welding consumables, and ancillary materials; The equipment control submodule covers equipment capability and equipment stability tests; The process design submodule involves joint structure, pre-weld joint requirements, and assembly requirements; The experimental design submodule includes specimen specifications, specimen materials, and batch quantity, primarily focusing on optimizing equipment control and process parameters through experimentation; Parameter determination, taking laser welding as an example, mainly includes Travel speed, wire feed speed, welding power, and working distance; Production control encompasses personnel requirements, production environment, Welding execution, stress relief, and welding repair; Quality requirements cover the appearance of welded joints, internal quality, mechanical properties, defect types, and handling of non-conforming welds; Inspection methods include production process records, visual inspection, non-destructive testing, and mechanical performance testing.