Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Referent Scientific Databases

3. Pharmacological Effects on Pain

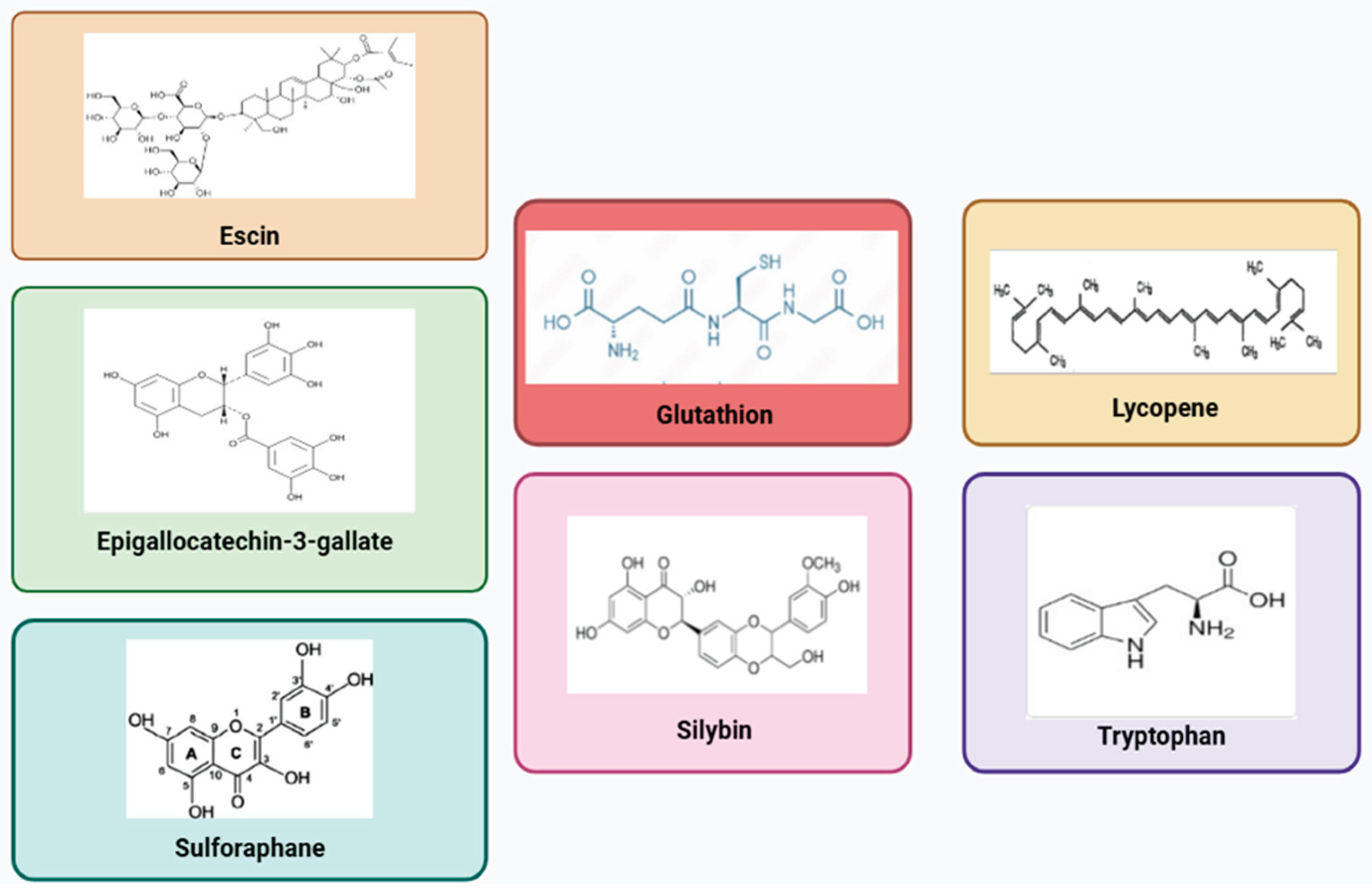

3.1. Lycopene (Solanum lycopersicum) and Glutathione

3.2. Silymarin (Silybum marianum)

3.3. Escin (Aesculus hippocastanum)

3.4. Tryptophan

3.5. Green Tea (Camellia sinensis)

3.6. Sulforaphane (Brassica oleracea)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IASP International Association for the Study of Pain -Terminology. Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/terminology/ (accessed on Jun 18, 2023).

- IASP High Impact Chronic Pain- International Association for the Study of Pain. Available online: https://www.iasp-pain.org/resources/fact-sheets/high-impact-chronic-pain/#:~:text=Chronic pain is a major,than three months %5B2%5D. (accessed on Dec 9, 2024).

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Series Chronic Pain 1 Chronic pain : an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcianò, G.; Vocca, C.; Evangelista, M.; Palleria, C.; Muraca, L.; Galati, C.; Monea, F.; Sportiello, L.; De Sarro, G.; Capuano, A.; et al. The Pharmacological Treatment of Chronic Pain: From Guidelines to Daily Clinical Practice. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, A.; Arif, A.W.; Bhan, C.; Kumar, D.; Malik, M.B.; Sayyed, Z.; Akhtar, K.H.; Ahmad, M.Q. Managing Chronic Pain in the Elderly: An Overview of the Recent Therapeutic Advancements. Cureus 2018, 10, 1.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corder, G.; Castro, D.C.; Bruchas, M.R.; Scherrer, G. Endogenous and exogenous opioids in pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 41, 453–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connor, J.O.; Christie, R.; Harris, E.; Penning, J.; Mcvicar, J. Tramadol and Tapentadol: Clinical and Pharmacologic Review. Available online: https://resources.wfsahq.org/atotw/tramadol-and-tapentadol-clinical-and-pharmacologic-review/ (accessed on Jul 24, 2022).

- Knadler, M.P.; Lobo, E.; Chappell, J.; Bergstrom, R. Duloxetine: Clinical pharmacokinetics and drug interactions. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2011, 50, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, H.; Friedrich, C.M.; Cole, P.; Eccleston, C.; Serfaty, M.; Stewart, G.; White, S.; Moore, R.A.; Phillippo, D.; Pincus, T. Antidepressants for pain management in adults with chronic pain: a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD014682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urits, I.; Li, N.; Berardino, K.; Artounian, K.A.; Bandi, P.; Jung, J.W.; Kaye, R.J.; Manchikanti, L.; Kaye, A.M.; Simopoulos, T.; et al. The use of antineuropathic medications for the treatment of chronic pain. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Anaesthesiol. 2020, 34, 493–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, A.B.; Dworkin, R.H. Treatment of Neuropathic Pain: An Overview of Recent Guidelines. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, S22–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koes, B.W.; Backes, D.; Bindels, P.J.E. Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy Pharmacotherapy for chronic non-specific low back pain : current and future options Pharmacotherapy for chronic non-specific low back pain : current and future options. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018, 19, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonagh, Marian S. Selph, S.S.; Buckley, D.I.; Holmes, Rebecca S. Mauer, K.; Ramirez, S.; Hsu, F.C.; Dana, T.; Fu, R.; Chou, R. Nonopioid Pharmacologic Treatments for Chronic Pain; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville (USA), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Benyamin, R.; Trescot, A.M.; Datta, S.; Buenaventura, R.; Adlaka, R.; Sehgal, N.; Glaser, S.E.; Vallejo, R. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008, 11, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Haroutounian, S.; McNicol, E.; Baron, R.; Dworkin, R.H.; Gilron, I.; Haanpaa, M.; Hansson, P.; Jensen, T.S.; et al. Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: Systematic review, meta-analysis and updated NeuPSig recommendations. Lancet Neurol 2015, 14, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asconapé, J.J. Use of antiepileptic drugs in hepatic and renal disease. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Thour, A.; Marwaha, R. Amitriptyline. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537225/ (accessed on Jul 25, 2022).

- Bjarnason, I. Gastrointestinal safety of NSAIDs and over-the-counter analgesics. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2013, 67, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, N.; Pollack, C.; Butkerait, P. Adverse drug reactions and drug–drug interactions with over-the-counter NSAIDs. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2015, 11, 1061–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcianò, G.; Muraca, L.; Rania, V.; Gallelli, L. Ibuprofen in the Management of Viral Infections: The Lesson of COVID-19 for Its Use in a Clinical Setting. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 63, 975–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, J.K. Defining ‘nutraceuticals’: neither nutritious nor pharmaceutical. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiarella, G.; Marcianò, G.; Viola, P.; Palleria, C.; Pisani, D.; Rania, V.; Casarella, A.; Astorina, A.; Scarpa, A.; Esposito, M.; et al. Nutraceuticals for Peripheral Vestibular Pathology: Properties, Usefulness, Future Perspectives and Medico-Legal Aspects. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIA Drolessano- Società Italiana di Andrologia. Available online: https://www.siabc.it/drolessano (accessed on Dec 9, 2024).

- Sebastiani, F.; Alterio, C.D.; Vocca, C.; Gallelli, L.; Palumbo, F.; Cai, T.; Palmieri, A. Effectiveness of Silymarin, Sulforaphane, Lycopene, Green Tea, Tryptophan, Glutathione, and Escin on Human Health : A Narrative Review. Uro 2023, 3, 208–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Chen, B.; Bai, Y.; Miao, T.; Rui, L.; Zhang, H.; Xia, B.; Li, Y.; Gao, S.; Wang, X.; et al. Lycopene in protection against obesity and diabetes: a mechanistic review. Pharmacol Res 2020, 159, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancak, M.; Altintas, D.; Balaban, Y.; Caliskan, U.K. Evidence-based herbal treatments in liver diseases. Hepatol Forum 2024, 5, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Rinna, A. Glutathione: overview of its protective roles, measurement, and biosynthesis. Mol Asp. Med 2010, 30, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcianò, G.; Vocca, C.; Dıraçoglu, D.; Özda, R.; Gallelli, L. Escin’ s Action on Bradykinin Pathway : Advantageous Clinical Properties for an Unknown Mechanism ? Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M.M.; Akter, S.; Lin, C.-N.; Nazzal, S. Sulforaphane as an anticancer molecule : mechanisms of action, synergistic effects, enhancement of drug safety, and delivery systems. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 371–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, M.; Rashidi, N.; Nurgali, K.; Apostolopoulos, V. The Role of Tryptophan Metabolites in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Sep 1; 2022, 23, 9968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Q. Molecular mechanisms of green tea polyphenols. Nutr Cancer 2009, 61, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, P.; Mitra, D.; Das, P.K.; Oana, A.; Mon, E.; Janmeda, P.; Martorell, M.; Iriti, M.; Ibrayeva, M.; Sharifi-rad, J.; et al. Camellia sinensis : Insights on its molecular mechanisms of action towards nutraceutical, anticancer potential and other therapeutic applications. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhad, A.; Sharma, S.; Chopra, K. Lycopene attenuates thermal hyperalgesia in a diabetic mouse model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pain. 2008 Jul;12(5)624-3 2008, 12, 624–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, A.; Ghosh, S.; Das, R.K.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Bhattacharya, S. Chemopreventive potential of diallylsulfide, lycopene and theaflavin during chemically induced colon carcinogenesis in rat colon through modulation of cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase pathways. Eur J Cancer Prev 2006, 15, 301–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.F.; Morioka, N.; Kitamura, T.; Fujii, S.; Miyauchi, K.; Nakamura, Y.; Hisaoka-nakashima, K.; Nakata, Y. Lycopene ameliorates neuropathic pain by upregulating spinal astrocytic connexin 43 expression. Life Sci. 2016, 155, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, L.; He, S.; Ren, H.; Zhou, N.; Hu, Z. Lycopene alleviates disc degeneration under oxidative stress through the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Probes 2020, 51, 101559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Q.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Xie, H. Effect of lycopene on pain facilitation and the SIRT1 / mTOR pathway in the dorsal horn of burn injury rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 889, 173365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, C.; Castro, L.; Fang, C.; Castro, M.; Sherali, S.; White, S.; Wang, R.; Neugebauer, V. Bioactive compounds for neuropathic pain : An update on preclinical studies and future perspectives. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 104, 108979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goel, R.; Tyagi, N. Potential Contribution of Antioxidant Mechanism in the Defensive Effect of Lycopene Against Partial Sciatic Nerve Ligation Induced Behavioral, Biochemical and Histopathological Modification in Wistar Rats. Drug Res. (Stuttg). 2016, 66, 633–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R.; Luo, X.; Huang, Y. Neuroprotective effects of lycopene in spinal cord injury in rats via antioxidative and anti-apoptotic pathway. Neurosci Lett 2017, 642, 07–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, G.; Fong, T.H.; Tzu, N.H.; Lin, K.H.; Chou, D.S.; Sheu, J.R. A Potent Antioxidant, Lycopene, Affords Neuroprotection Against Microglia Activation and Focal Cerebral Ischemia in Rats. In Vivo (Brooklyn). 2004, 356, 351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Tian, M.; Hua, T.; Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, H. Combination of autophagy and NFE2L2 / NRF2 activation as a treatment approach for neuropathic pain. Autophagy 2021, 17, 4062–4082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassani, F.V.; Rezaee, R.; Sazegara, H.; Hashemzaei, M.; Karimi, G. Effects of silymarin on neuropathic pain and formalin - induced nociception in mice. Iran J Basic Med Sci 2015, 18, 715–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zugravu, G.S.; Pintilescu, C.; Cumpat, C.; Miron, S.D.; Miron, A. Silymarin Supplementation in Active Rheumatoid Arthritis : Outcomes of a Pilot Randomized Controlled Clinical Study. Med. 2024, 60, 999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.E.; Elieh-Ali-Komi, D.; Goudarzi, F.; Mohammadi-Noori, E.; Assar, S.; Shavandi, M.; Kiani, A.; Elahi, H. Effects of silymarin as adjuvant drug on serum levels of CTRP3, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP), and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2024, 13, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallelli, L. Escin: A review of its anti-edematous, antiinflammatory, and venotonic properties. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2019, 13, 3425–3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallelli, L.; Cione, E.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L. Glucocorticoid-Like Activity of Escin : A New Mechanism for an Old Drug. Drug Des Devel Ther 2021, 15, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.-Q.; Xu, S.-Q.; Cheng, J.; Cao, X.-L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, W.-P.; Huang, Y.-J.; Wang, J.; Hu, X.-M. Anti-inflammatory effect of external use of escin on cutaneous inflammation: possible involvement of glucocorticoids receptor. Chin. J. Nat. Med. 2018, 16, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pabst, H.; Segesser, B.; Bulitta, M.; Wetzel, D.; Bertram, S. Efficacy and tolerability of escin/diethylamine salicylate combination gels in patients with blunt injuries of the extremities. Int. J. Sports Med. 2001, 22, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, D.; Menke, W.; Dieter, R.; Smasal, V.; Giannetti, B.; Bulitta, M. Escin/diethylammonium salicylate/heparin combination gels for the topical treatment of acute impact injuries: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled, multicentre study. Br J Sport. Med 2002, 36, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, X.; Wu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, T.; Zhang, L.; Yan, Z.; Wei, G. Ameliorative effects of escin on neuropathic pain induced by chronic constriction injury of sciatic nerve. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 267, 113503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Fanni, T.; Szab, Á. Co-Players in Chronic Pain : Neuroinflammation and the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic Pathway. Biomedicines. 2021, 9, 897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colorado Division of Workers’ Compensation Chronic Pain Disorder Medical Treatment Guideline. 2017; 1–178.

- SIGN Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network- Management of chronic pain. Available online: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/SIGN136.pdf (accessed on Jul 17, 2022).

- King, R.B. Pain and tryptophan. J Neurosurg 1980, 53, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittorio, S.; Erica, S.; Cinzia, C.; Alvise, M.; Elena, M.; Alessandro, P.; Enrico, P.; Katia, D.; Teresa, V.M.; Luca, D.C. Comparison between Acupuncture and Nutraceutical Treatment with Migratens ® in Patients with Clinical Trial. Nutr.. 2020, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullano, S.A.; Marcianò, G.; Bianco, M.G.; Oliva, G.; Rania, V.; Vocca, C.; Cione, E.; De Sarro, G.; Gallelli, L.; Romeo, P.; et al. FT-IR Analysis of Structural Changes in Ketoprofen Lysine Salt and KiOil Caused by a Pulsed Magnetic Field. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshghpour, M.; Mortazavi, H.; Mohammadzadeh Rezaei, N.; Nejat, A. Effectiveness of green tea mouthwash in postoperative pain control following surgical removal of impacted third molars: Double blind randomized clinical trial. DARU, J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 21, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bimonte, S.; Cascella, M.; Schiavone, V.; Mehrabi-Kermani, F.; Cuomo, A. The roles of epigallocatechin-3-gallate in the treatment of neuropathic pain: an update on preclinical in vivo studies and future perspectives. Drug Des Devel Ther 2017, 11, 2737–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papini, J.Z.B.; Esteves, B. de A.; Oliveira, V.G. de S.; Abdalla, H.B.; Cereda, C.M.S.; de Araújo, D.R.; Tofoli, G.R. Analgesic Effect of Sulforaphane: A New Application for Poloxamer-Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels. Gels 2024, 10, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, C. Anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory actions of sulforaphane in chronic constriction injury-induced neuropathic pain mice. Inflammopharmacology 2017, 25, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, G.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.S. Nrf2 and NF- κ B Modulation by Sulforaphane Counteracts Multiple Manifestations of Diabetic Neuropathy in Rats and High Glucose-Induced Changes. Curr Neurovasc Res 2011, 8, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, C.; Fang, X.; Zhan, G.; Huang, N.; Gao, J.; Xu, H.; Orlando, G. Role of Keap1-Nrf2 Signaling in Anhedonia Symptoms in a Rat Model of Chronic Neuropathic Pain : Improvement With Sulforaphane. Front Pharmacol 2018, 9, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redondo, A.; Chamorro, P.A.F.; Riego, G.; Leánez, S.; Pol, O. Treatment with Sulforaphane Produces Antinociception and Improves Morphine Effects during Inflammatory Pain in Mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2017, 363, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucarini, E.; Testai, L.; Micheli, L.; Trallori, E.; Citi, V.; Martelli, A.; Rosalinda, G.; Renato, D.N.; Vincenzo, I.; Ghelardini, C.; et al. Effect of glucoraphanin and sulforaphane against chemotherapy - induced neuropathic pain : Kv7 potassium channels modulation by H 2 S release in vivo. Phytother Res 2018, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadarrama-Enríquez, O.; Moreno-Pérez, G.; González-Trujano, ME Ángeles-López, G.; Ventura-Martínez, R.; Díaz-Reval, I.; Cano-Martínez, A.; Pellicer, F.; Baenas, N.; Moreno, D.; García-Viguera, C.A. and antiedema effects produced in rats by B. oleracea var. italica sprouts involving sulforaphane. I. 2023 D.-3226. doi: Antinociceptive and antiedema effects produced in rats by Brassica oleracea var . italica sprouts involving sulforaphane. Inflammopharmacology 2023, 31, 3217–3226. [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Xu, G.; Lin, Z.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, F.; Xia, X.; Ma, X.; Zou, F.; et al. Sulforaphane Delays Intervertebral Disc Degeneration by Alleviating Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Nucleus Pulposus. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2023, 2023, 3626091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Küçükkurt, I.; Akbel, E.; Ince, S.; Acaröz, D.A.; Demirel, H.H.; Kan, F. Potential protective effect of escin from Aesculus hippocastanum extract against cyclophosphamide-induced oxidative stress on rat tissues. Toxicol. Res. (Camb). 2022, 11, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Dou, C.; Hu, L.; Du, G.; Wei, G. Deciphering the Molecular Mechanism of Escin against Neuropathic Pain : A Network Pharmacology Study. Evid Based Complement Altern. Med 2023, 16, 3734861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, T.L.; Miller, R.E. Molecular pathogenesis of OA pain_ Past, present, and future. Osteoarthr. Cartil. 2024, 32, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.P.; Mao, J. Neuropathic pain: Mechanisms and their clinical implications. BMJ 2014, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCANJ Pain Management Guideline. Available online: https://www.hcanj.org/files/2013/09/Pain-Management-Guidelines-_HCANJ-May-12-final.pdf (accessed on Jul 17, 2022).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Chronic pain (primary and secondary) in over 16s: assessment of all chronic pain and management of chronic primary pain. NICE Guidel. 2021.

- GVR Nutraceuticals Market Size & Trends-Grand View Research. Available online: https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/nutraceuticals-market (accessed on Dec 13, 2024).

- Cole, J.A.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Alqahtani, M.; Barry, H.E.; Cadogan, C.; Rankin, A.; Patterson, S.M.; Kerse, N.; Cardwell, C.R.; Ryan, C.; et al. Interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023, 11, CD008165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vocca, C.; Siniscalchi, A.; Rania, V.; Galati, C.; Marcianò, G.; Palleria, C.; Catarisano, L.; Gareri, I.; Leuzzi, M.; Muraca, L.; et al. The Risk of Drug Interactions in Older Primary Care Patients after Hospital Discharge : The Role of Drug Reconciliation. Geriatr. 2023, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peritore, A.F.; Siracusa, R.; Crupi, R. Therapeutic Efficacy of Palmitoylethanolamide and Its New Formulations in Synergy with Different Antioxidant Molecules Present in Diets. Nutrients 2019, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onofrj, M.; Ciccocioppo, F.; Varanese, S.; Di Muzio, A.; Calvani, M.; Chiechio, S.; Osio, M.; Thomas, A. Acetyl-L-carnitine: From a biological curiosity to a drug for the peripheral nervous system and beyond. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2013, 13, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiechio, S.; Copani, A.; Iv, R.W.G.; Nicoletti, F. Acetyl-L-carnitine in neuropathic pain: experimental data. CNS Drugs. 2007, 21, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogacci, F.; Rizzo, M.; Krogager, C.; Kennedy, C.; Georges, C.M.G.; Knežević, T.; Liberopoulos, E.; Vallée, A.; Pérez-Martínez, P.; Wenstedt, E.F.E.; et al. Safety evaluation of α-lipoic acid supplementation: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled clinical studies. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tankova, T.; Koev, D.; Dakovska, L. Alpha-lipoic acid in the treatment of autonomic diabetic neuropathy (controlled, randomized, open-label study). Rom J Intern Med 2004, 42, 457–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Artukoglu, B.B.; Beyer, C.; Zuloff-Shani, A.; Brener, E.; Bloch, M.H. Efficacy of palmitoylethanolamide for pain: A meta-analysis. Pain Physician 2017, 20, 353–362. [Google Scholar]

- Petkova-Gueorguieva, E.S.; Getov, I.N.; Ivanov, K. V.; Ivanova, S.D.; Gueorguiev, S.R.; Getova, V.I.; Mihaylova, A.A.; Madzharov, V.G.; Staynova, R.A. Regulatory Requirements for Food Supplements in the European Union and Bulgaria. Folia Med. (Plovdiv). 2019, 61, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, S.; Sawarkar, S.; Doshi, G.; Pimple, P.; Shah, J.; Bana, T. Chapter twenty one - Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of nutraceuticals. In Industrial Application of Functional Foods, Ingredients and Nutraceuticals; Anandharamakrishnan, C., Subramanian, P., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2023; pp. 725–783. [Google Scholar]

- Shavandi, M.; Yazdani, Y.; Asar, S.; Mohammadi, A. The Effect of Oral Administration of Silymarin on Serum Levels of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-1ß in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Iran J Immunol 2022, 19, 427–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Somogyi, A.A.; Barratt, D.T.; Coller, J.K. Pharmacogenetics of opioids. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 81, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marcianò, G.; Siniscalchi, A.; Gennaro, G. Di; Rania, V.; Vocca, C.; Palleria, C.; Catarisano, L.; Muraca, L.; Citraro, R.; Evangelista, M.; et al. Assessing Gender Differences in Neuropathic Pain Management : Findings from a Real-Life Clinical Cross-Sectional Observational Study. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 5682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rania, V.; Marcianò, G.; Casarella, A.; Vocca, C.; Palleria, C.; Calabria, E.; Spaziano, G.; Citraro, R.; Sarro, G. De; Monea, F.; et al. Oxygen – Ozone Therapy in Cervicobrachial Pain : A Real-Life Experience. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Muley, M.M.; Beggs, S.; Salter, M.W. Microglia-independent peripheral neuropathic pain in male and female mice. Pain 2022, 163, e1129–e1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.K.; Old, E.A.; Malcangio, M. Neuropathic pain and cytokines: Current perspectives. J. Pain Res. 2013, 6, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coraggio, V.; Guida, F.; Boccella, S.; Scafuro, M.; Paino, S.; Romano, D.; Maione, S.; Luongo, L. Neuroimmune-driven neuropathic pain establishment: A focus on gender differences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekar, T.; Kreft, S. Common risks of adulterated and mislabeled herbal preparations. Food Chem Toxicol 2019, 123, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awortwe, C.; Bruckmueller, H.; Cascorbi, I. Interaction of herbal products with prescribed medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Phramcol Res 2019, 141, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Opuni, K.F.M.; Kretchy, J.P.; Agyabeng, K.; Boadu, J.A.; Adanu, T.; Ankamah, S.; Appiah, A.; Amoah, G.B.; Baidoo, M. , Kretchy, I.A. Contamination of herbal medicinal products in low-and-middle-income countries: A systematic review. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Guidelines for assessing quality of herbal medicines with reference to contaminants and residues. World Health Organization. 2007. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/43510/9789241594448_eng.pdf.

- FDA Dietary Supplements. 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements.

- EC Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of The Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community code relating to medicinal products for human use. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:02001L0083-20210526.

- EMA Herbal medicinal products. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory-overview/herbal-medicinal-products.

- EMA List of national competent authorities in the EEA. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/partners-networks/eu-partners/eu-member-states/national-competent-authorities-human#list-of-national-competent-authorities-in-the-eea-11541.

- Thakkar, S.; Anklam, E.; Xu, A.; Ulberth, F.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Hugas, M.; Sarma, N.; et al. Regulatory landscape of dietary supplements and herbal medicines from a global perspective. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 2020, 114, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Mechanism | References |

| Lycopene | TNF-α and NO inhibition. | [33] |

| COX 2 inhibition | [33] | |

| Restoring the expression of Cx 43 | [35] | |

| Modulation on Nrf2 and autophagy modulation | [36] | |

| Reduced glial activation. Decrease of the expression of markers like pS6, mTOR, GFAP, p4EBP, Iba 1 and SIRT 1. | [37] | |

| Reduction of thermal and cold hyperalgesia, increase of CAT, GSH, SOD, MDA levels and signs of histopathological nerve damage, reduction of cell apoptosis. | [38] | |

| Neuroprotective effect on microglia | [41] | |

| Silymarin | Inhibition of PGE2, leukotrienes, NO, cytokines production IL 1-β and TNF-α reduction, and neutrophils infiltration. Silymarin is also a scavenger, and this may account for its beneficial properties. |

[43] |

| Reduced glutathione | Antioxidant effects | [42] |

| Escin | Glucocorticoid like activity with inhibition of NF-κB and hyaluronidase | [47] |

| Action on bradykinin pathway | [28] | |

| Antioxidant effect and endothelium protection | [46,68] | |

| Downregulation of TNF and IL1ß, TLR4, NF-κB, GFAP and NGF. | [51] | |

| Targeting of MMP9, SRC, PTGS 2, and MAPK 1, PKC, the T-cell receptors signaling pathway, TRP channels, and TNF. | [46,69] | |

| Tryptophan | Improvement of pain related dysfunction including mood disorders and insomnia, acting on serotonin pathway | [56] |

| Green tea | Inhibition of PMNs, NADPH-oxidase, myeloperoxidase, and to favor scavenging of superoxide anions. | [59] |

| Inhibition of nNOS/NO; CX3CL1, JNK, and NF-κB; TNF-α. | [59] | |

| Sulforaphane | Inhibition of Nrf 2, IL-1β, TNFα, COX-2, NLRP 3, NF-κB and CGRP | [60] |

| Increase of IL-10 | [66,67] | |

| Increase of μ opioid receptor expression | [61] | |

| Inhibition of the release of H2S and of potassium Kv7 channels activation | [65] | |

| CAT, catalase; CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide; Cx, connexin; COX, cyclooxygenase; H2S, hydrogen sulphide; CX3CL1, chemokine (C-X3-C motif) ligand 1; GFAP, glial fibrillary acidic protein; GSH, reduced glutathione; IL, interleukin; Iba1, ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1; JNK, Janus Kinase; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MMDA, malondialdehyde; MMP, metalloproteinase; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; NADPH, Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate Hydrogen; NGF, nerve growth factor; NF-κB, Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells ; NLRP, nucleotide-binding domain, leucine-rich–containing family, pyrin domain–containing; NO, nitric oxide; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; Nrf2, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2; PG, prostaglandin; PMN, polymorphonuclear leukocytes; PKC, protein kinase C; PTGS, prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase; SIRT1, sirtuin 1; SOD, superoxide dismutase; SRC, Steroid Receptor Coactivator; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; TRP, transient receptor potential. | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).