1. Introduction

Neuropathic pain (NP) is a chronic pain characterized by persistent or intermittent spontaneous pain, often accompanied by evoked pain, particularly cold or mechanical allodynia. NP arises from injury or malfunction of the nerves or spinal cord and is commonly prevalent in clinical practice. It may emerge as a secondary condition from a variety of clinical disorders, including trauma, stroke, infection, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and cancer[

1,

2]. Globally, the incidence of NP accounts for 6.9% to 10% of the total population [

3]. NP leads to significant reductions in both quality of life and behavioral function, placing a heavy physical and psychological burden on patients[

4]. The pathophysiology of NP is complex and multifactorial. Despite the availability of various interventions based on different mechanisms, the results of NP treatment are still unsatisfactory[

5]. Commonly used medications for NP, such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids, often cause adverse effects, including dizziness, drowsiness, arrhythmias, and issues related to tolerance when used alone[

6]. Consequently, the development of combination therapies targeting multiple analgesic mechanisms has become a promising insight in the treatment of NP. Indeed, clinical approaches to chronic pain often evolve from initial monotherapy to combination therapy as a more effective means of addressing the complex nature of NP[

7].

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) boasts an extensive history in the treatment of NP, with many Chinese herbal medicines and their active compounds reported to alleviate NP symptoms[

8]. These therapies represent a rich source for the screening of potential combination drugs for NP treatment. Chuanxiong Rhizoma, derived from the rhizome of

Ligusticum chuanxiong Hort., has been widely used in traditional medicine since the Han Dynasty (~1800 years ago), though it is typically employed as an adjunctive or supporting medicine according to TCM theory. Ligustrazine (LGZ), the major active ingredient of Chuanxiong Rhizoma, exhibits outstanding pharmacological effects in blood circulation or peripheral improving microcirculation. Its formulations, such as ligustrazine injection and salvia miltiorrhiza-ligustrazine injection are primarily used in China for the treatment of occlusive cerebrovascular diseases[

9,

10]. As reported, LGZ exhibited therapeutic effects in various pain animal models, such as migraine[

11] and spinal cord injury-induced NP [

12]. Sinomenii Caulis, sourced from the stems of

Sinomenium acutum (Thunb.) Rehd. et Wils. and

Sinomenium acutum var.

cinereum Rehd. et Wils. Sinomenine (SIN), the active compound in Sinomenii Caulis, is used clinically for the treatment of rheumatism, rheumatoid arthritis, and related pain symptoms[

13,

14]. SIN has demonstrated analgesic effects on inflammatory pain[

15], spared nerve injury-induced NP[

16], and diabetic peripheral NP[

17], exerting both anti-inflammatory and analgesic mechanisms. Our previous studies have shown that the combination of LGZ and SIN was effective in alleviating pain in various NP models, including those induced by sciatic nerve injury, trigeminal nerve injury, and spinal cord injury[

18]. Moreover, the combination of LGZ and SIN exhibited a synergistic analgesic effect, allowing for a reduction in the individual dosages of each compound. Both LGZ and SIN have been reported to have numerous potential targets and pathways, but the specific mechanisms underlying their analgesic effected in NP remain unclear.

Network pharmacology analyzes the relationships among drugs, targets, and diseases through network-based approaches, making it particularly well-suited for elucidating core targets and pathways in treating complex diseases by TCM, which characterized by "multi-target" and "multi-pathway"[

19]. By offering a systems-level perspective, network pharmacology uncovers the potential molecular mechanisms of TCM, shedding light on its holistic therapeutic effects[

20,

21]. Metabolomics, an essential component of systems biology, utilizes high-throughput and highly sensitive instruments to conduct comprehensive profiling of endogenous components within biological samples. By integrating multivariate statistical methods, metabolomics can reveal changes in endogenous metabolites under vatious physiological, pathological, or toxicological conditions[

22], enabling the identification of the key metabolic pathways within the organism[

23]. Therefore, the integration of metabolomics with network pharmacology can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the metabolic pathways and network regulatory mechanisms of the combined therapy in treating complex disease.

In this study, network pharmacology was initially used to predict the potential targets of LGZ and SIN in treating pain-related diseases, analyzing both their shared and distinct targets. Subsequently, the analgesic effects of LGZ, SIN and their combination at different time points and dosages were comprehensively evaluated in a chronic constriction injury (CCI)-induced NP model in rats. Furthermore, the key metabolites in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were screened, and their content were quantified using LC-MS metabolomics technology. Finally, a joint analysis of the potential targets and key metabolites was conducted to identify the crucial metabolic pathways through which LGZ and SIN exert their therapeutic effects in NP. The aim of this study was to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the combined use of LGZ and SIN in treating NP. Additionally, this research aimed to offer new experimental evidence to support the clinical combined application of LGZ and SIN in treating NP.

3. Discussion

NP is a secondary condition to various clinical disorders and significantly impacts on patients' quality of life. However, the precise pathogenesis of NP poorly understands, involving complex interactions of multiple signaling pathways and targets. Studies have demonstrated that in a spinal cord injury-induced NP rat model, tyrosine metabolism was disrupted, with dopamine levels significantly lower compared to normal rats[

24]. Furthermore, the levels of phenylalanine and tyrosine in the CSF of patients with localized pain syndromes were markedly elevated[

25]. Therefore, multi-drug combination therapies, encompassing both combined pharmaceutical agents and multi-target TCM, can partially address clinical treatment needs. However, for certain drugs with unclear mechanisms, it is essential to identify their key therapeutic targets. Small molecules derived from natural products or TCM frequently exhibit multi-target properities, complicating the precise identification of their therapeutic targets[

26]. Thus, employing metabolomics or network analysis techniques analysis to investigate the mechanism of action of these drugs through the modulation of entire metabolic pathways or networks could represent a promising approach[

27]. Chuanxiong Rhizoma and Sinomenii Caulis, widely utilized in clinical practice as TCM, have long been recognized for their substantial efficacy in treating various pain-related diseases. Based on those findings, we selected their active components, LGZ and SIN, for combined application, with the aim of exploring their potential therapeutic effects on NP.

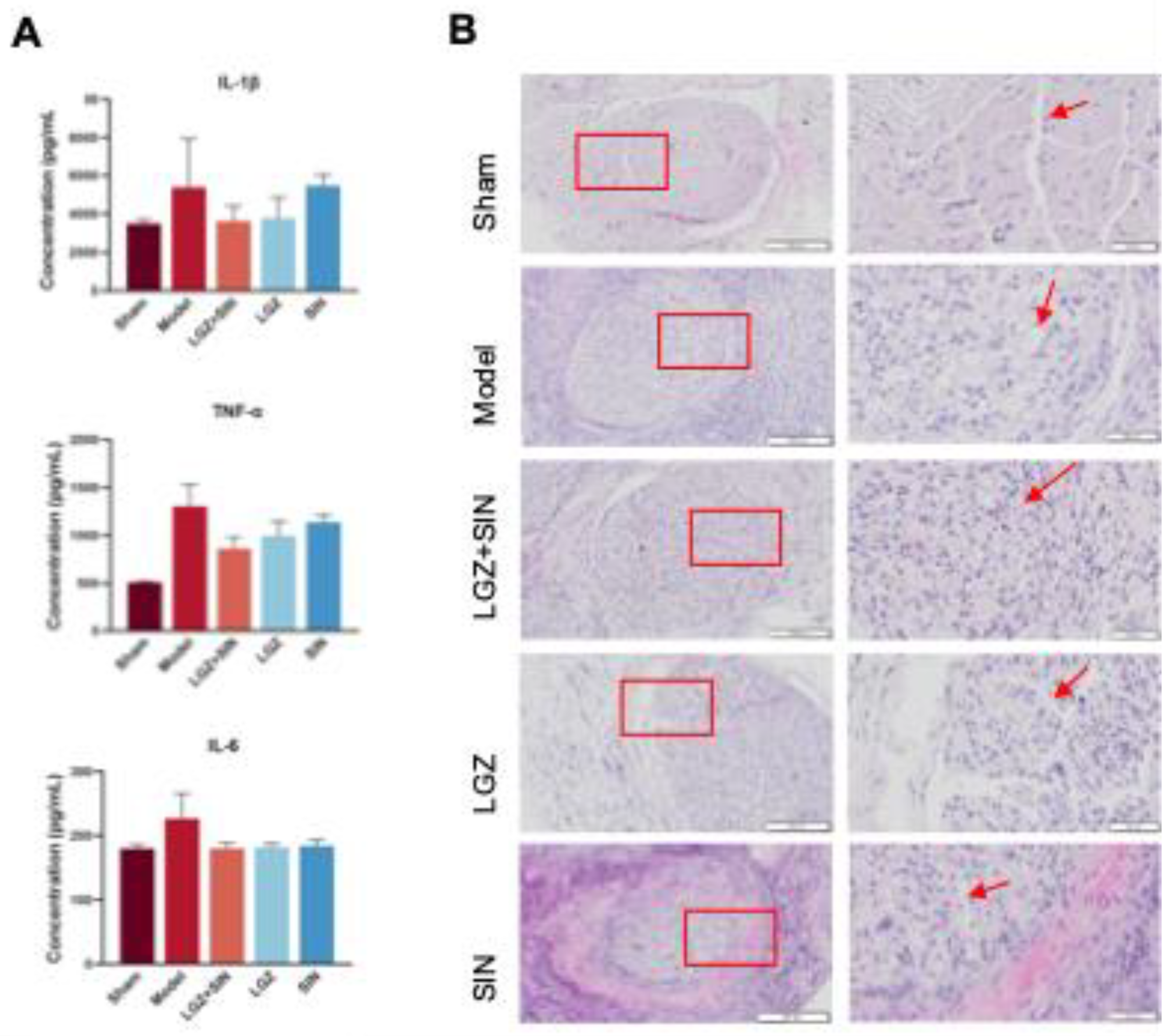

In previous studies, we investigated the analgesic effects of the combined use of LGZ and SIN in models of inflammatory pain, sciatic nerve injury, and spinal cord injury NP [

18]. Given that the CCI model simulated both neuropathic and inflammatory pain characteristics, we examined the analgesic effects of LGZ and SIN in combination, as well as individually, in the CCI model rats to comprehensively assess the advantage benefits of their combined use. In prior research, LGZ and SIN were administered via intraperitoneal injection[

16], whereas both have established oral administration protocols[

28,

29]. Therefore, in this study, we evaluated the analgesic effects of the oral administration of LGZ and SIN in combination. Additionally, the experimental design assessed the analgesic effects of various dosages and time points for both combined and single-drug treatments to fully characterize the analgesic properties of the LGZ-SIN combination. The results from the MWT test, cold allodynia test, and incapacitance test demonstrated that the combined use of LGZ and SIN, as well as individual treatments, effectively alleviated mechanical allodynia, cold pain sensitivity, and spontaneous pain in CCI-induced NP. Furthermore, the combination of LGZ and SIN exhibited significant greater analgesic effects than single-drug treatments, reinforcing the rationale for their combined use. Moreover, the results suggested that the combined use of LGZ and SIN also produced beneficial effects on sciatic nerve inflammation and repair in CCI rats. Following the evaluation of LGZ, SIN, and their combination, we conducted network pharmacology and metabolomics studies to explore their potential mechanisms in treating NP.

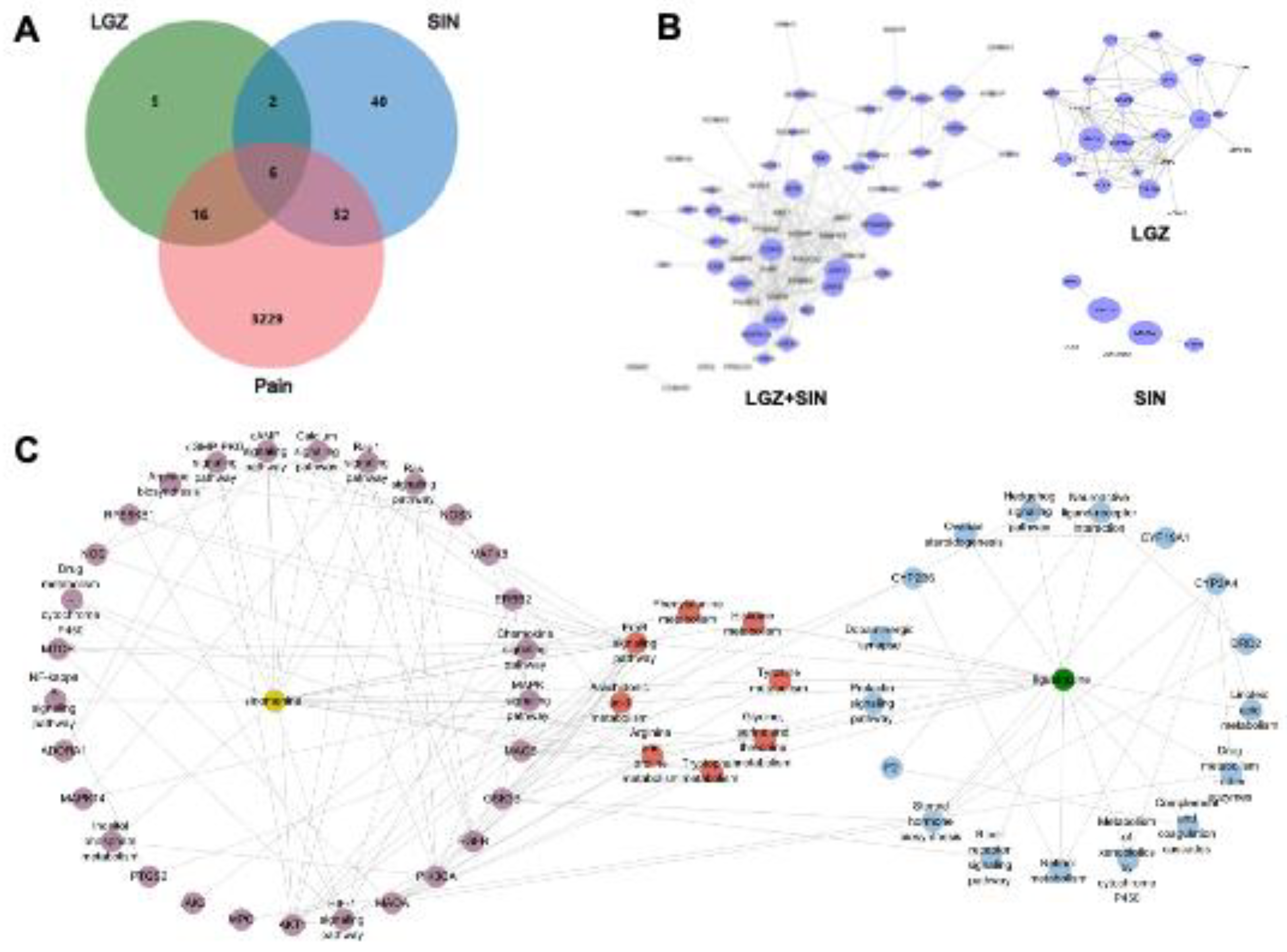

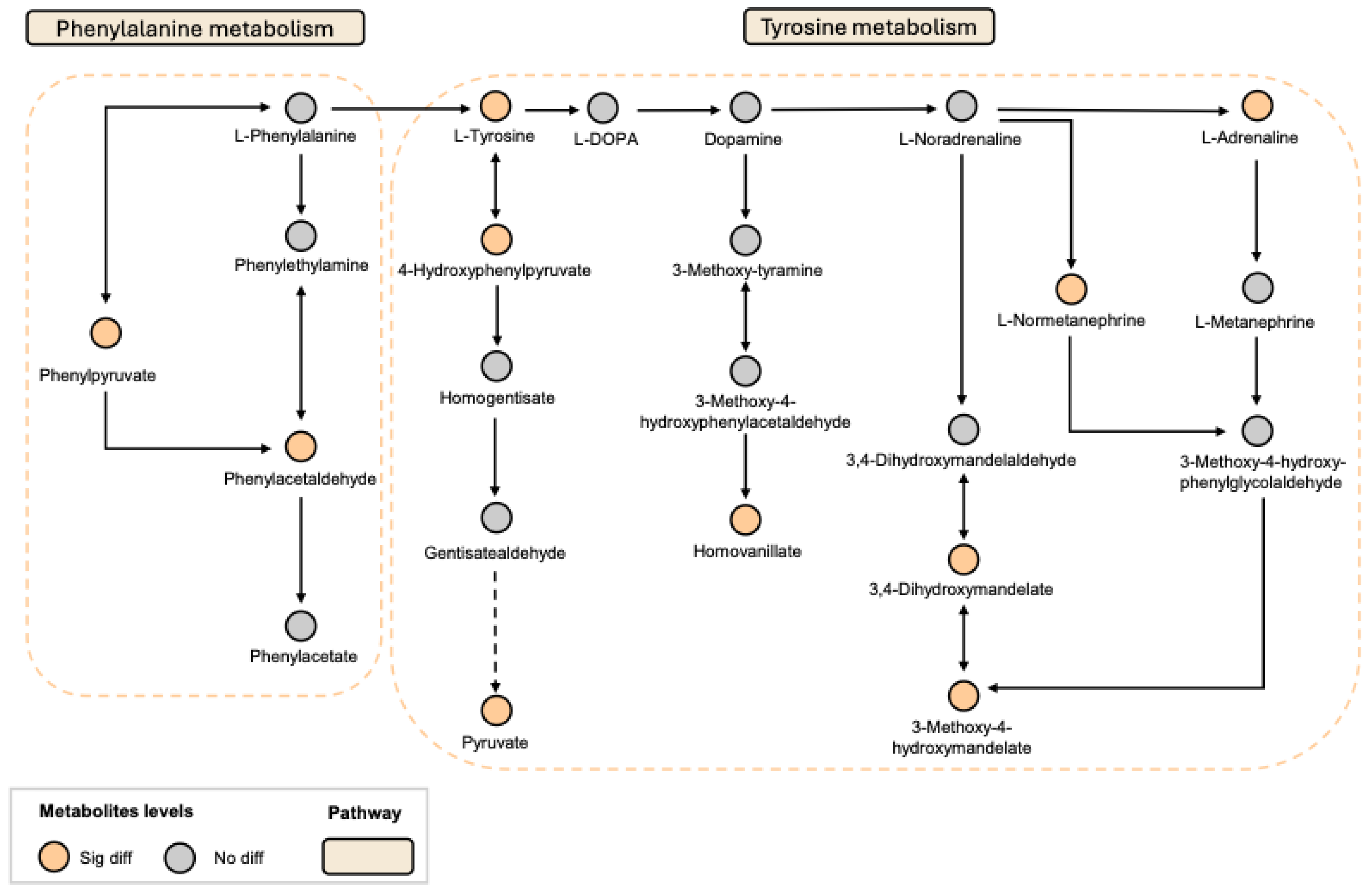

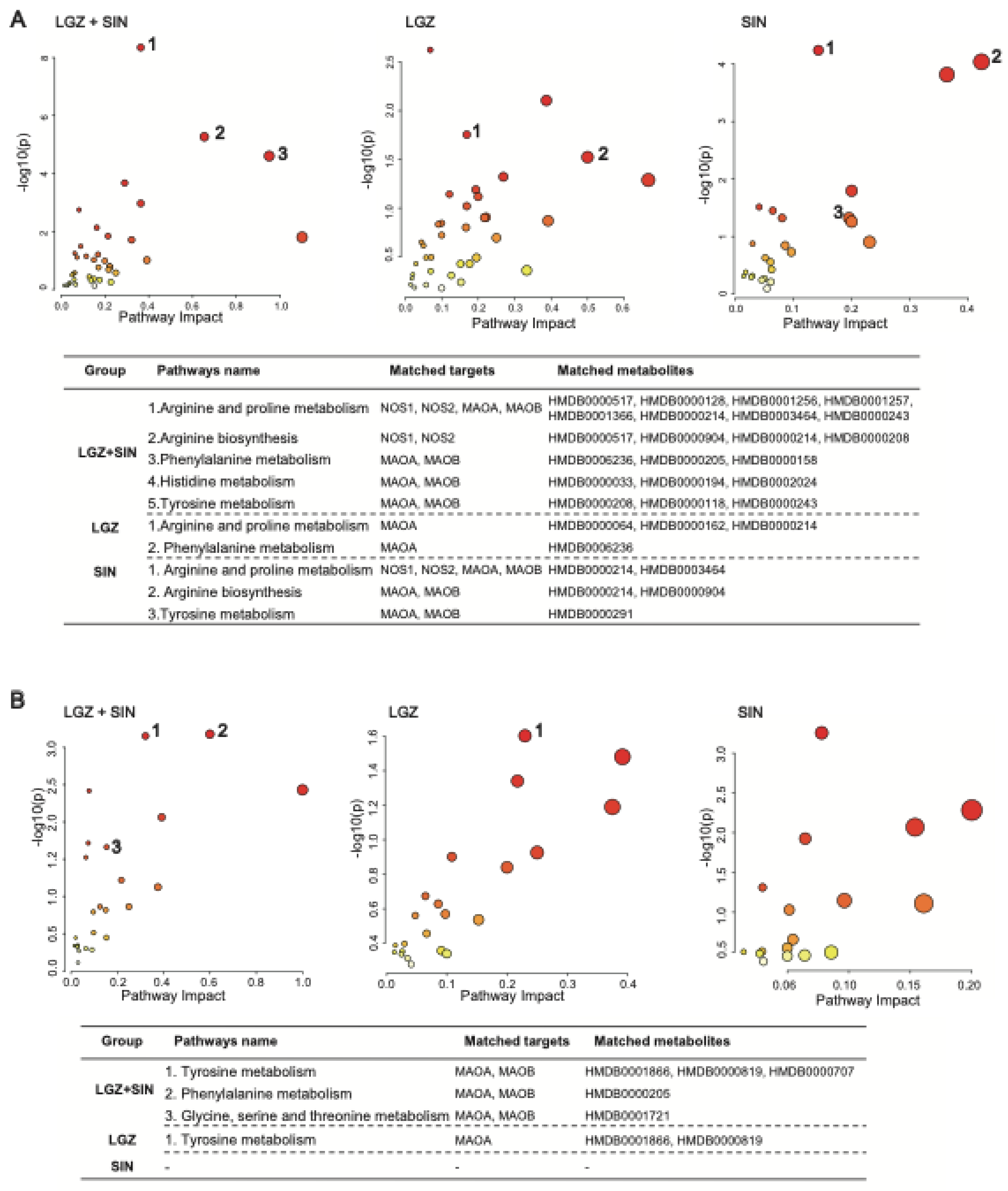

The network pharmacology approach elucidated the analgesic mechanism of the combined use of LGZ and SIN starting from these two substances. First, both LGZ and SIN exhibited multi-target properties. Second, pathway analysis confirmed that both LGZ and SIN could regulate multiple signaling pathways to exert their synergistic effects. Based on network pharmacology results, modulation of the tyrosine metabolism and phenylalanine metabolism pathway might be the key mechanisms through which the combined use of LGZ and SIN exerted its analgesic effects.

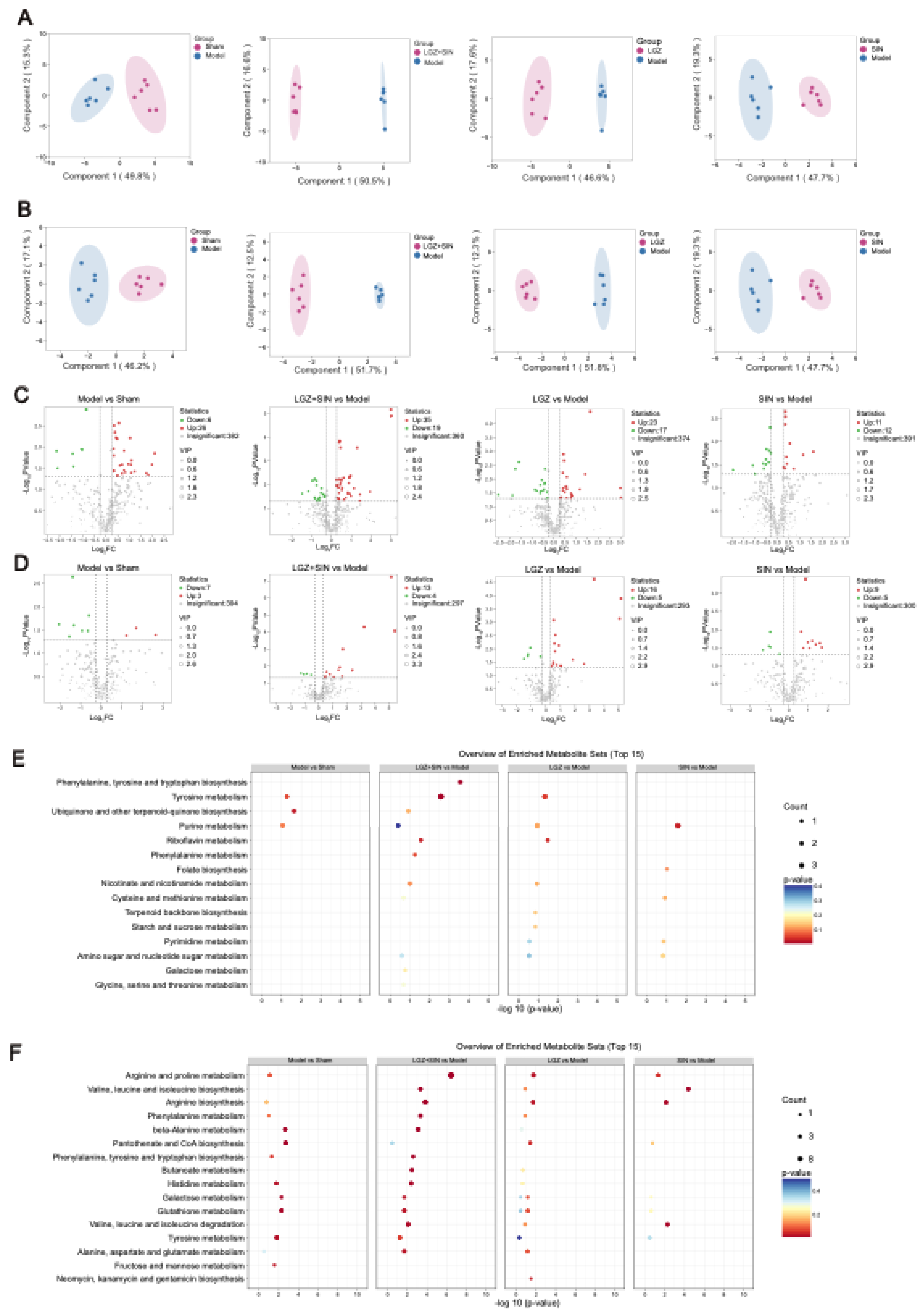

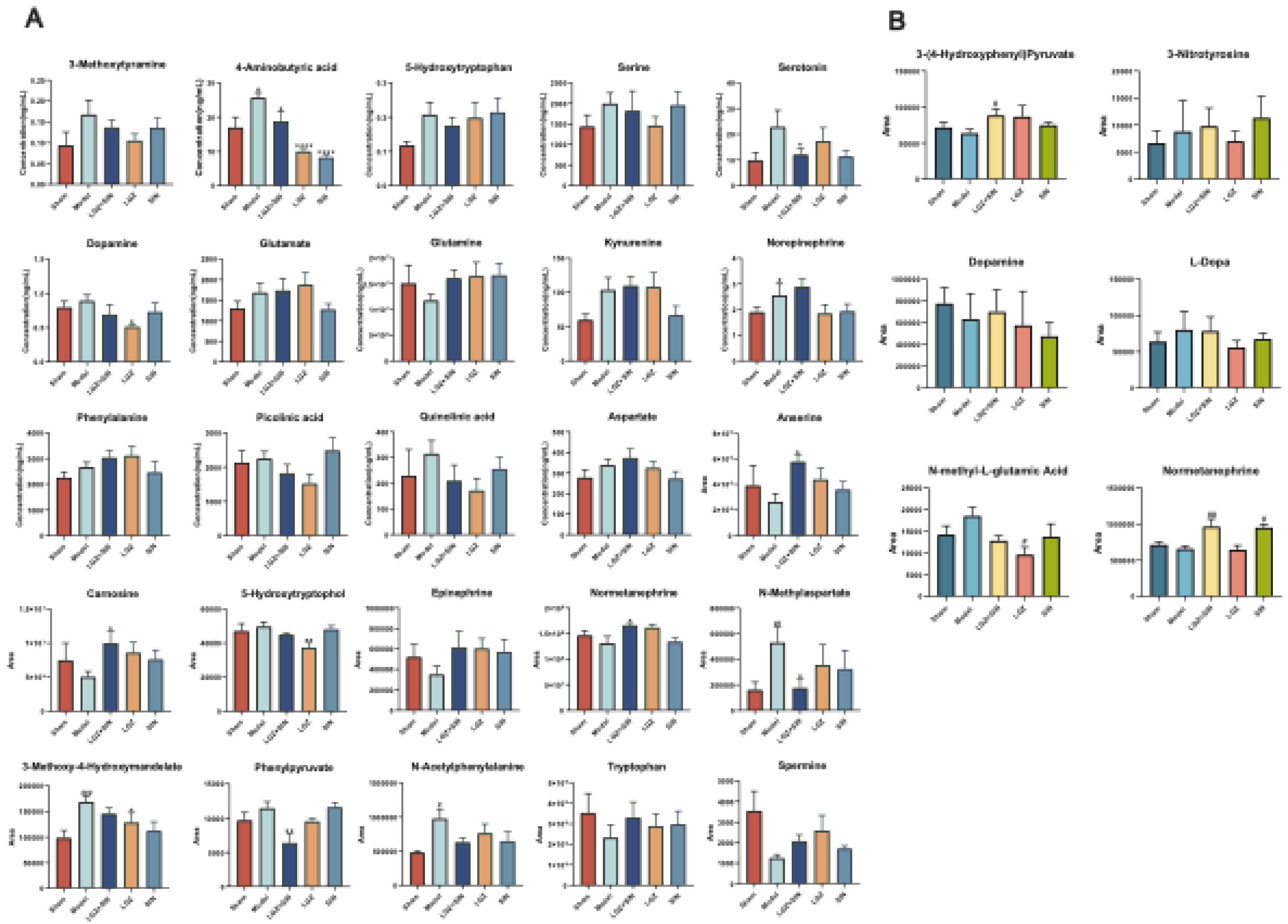

Given that NP affects both peripheral and central systems, this study analyzed plasma and CSF samples to investigate the metabolic regulatory effects of the combined use of LGZ and SIN, as well as their individual effects, on CCI rats. The results of metabolic pathway analysis showed that the combined treatment of LGZ and SIN regulated more metabolic pathways in both CSF and plasma samples compared to either LGZ or SIN used alone, exhibiting a synergistic effect. Finally, joint pathway analysis revealed that tyrosine metabolism and phenylalanine metabolism were the pathways enriched in both CSF and plasma samples. These pathways were considered the most critical. Among these, LGZ had a greater impact on tyrosine metabolism in CSF, while SIN exhibited a stronger effect on tyrosine metabolism in plasma. The arginine and proline metabolism pathways contained the most targets and differential metabolites enriched by the combined treatment of LGZ and SIN in plasma samples. Therefore, the combined treatment of LGZ and SIN might alleviate pain in the CCI model rats by jointly regulating tyrosine metabolism and phenylalanine metabolism in the CSF and plasma, as well as regulating arginine and proline metabolism in the plasma.

Tyrosine is an essential amino acid, and phenylalanine serves as its precursor. Both tyrosine and phenylalanine are precursors to monoamine neurotransmitters, including dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. The descending monoaminergic pathways, particularly norepinephrine and serotonin transmission, played a crucial role in the endogenous pain modulation system, a mechanism confirmed in NP[

30]. Studies have shown that CCI resulted a reduction of neurotransmitters crucial to the descending pain regulation pathways, such as serotonin and norepinephrine[

31]. Moreover, antidepressants that inhibited the reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin have been shown to be effective in chronic neuropathic pain[

5]. Metabolomics results showed that serotonin and its precursor, tryptophan, were reduced in the plasma of the Model group, but their levels were restored after treatment. The LGZ+SIN group demonstrated a more pronounced recovery compared to individual treatments. Arginine, a non-essential amino acid, serve as a precursor for nitric oxide, proline, and glutamate. Studies have demonstrated that arginine could increase pain sensitivity in animal models[

32]. Small-scale patient studies have suggested that L-arginine might have an analgesic effect in chronic pain[

33]. The central glutamatergic system played a critical role in the onset and persistence of persistent pain, including both neuropathic and inflammatory pain[

34]. Following nerve injury, the downregulation of GABA and opioid receptors in the spinal cord increased glutamate release, which might contribute to the development of neuropathic pain[

35]. Studies have shown that CCI-induced NP reduced GABA levels and neuronal activity in the dorsal horn[

36]. Furthermore, the glutamatergic system could exacerbate chronic neuropathic pain by activating N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) [

37]. Some studies have suggested that inhibiting NMDARs could alleviate the severity of NP[

38]. In the metabolomics analysis, the decrease in glutamine levels in the Model group and the subsequent recovered following treatment may be associated with this effect.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the therapeutic effects and potential mechanisms of combining LGZ and SIN for the treatment of neuropathic pain induced by CCI, using metabolomics and network pharmacology approaches. However, some limitations remain at the current stage. Further research is needed to elucidate the detailed mechanisms underlying the combined use of LGZ and SIN in treating CCI rats, with particularly focus on their targets and associated metabolic signaling pathways.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals and Treatment

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (180-200g) were obtained from Beijing Hfk Biosicence Co., Ltd. 3 rats were housed per cage in SPF-grade lab at a constantly maintained temperature (22 ± 2°C) with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and allowed free access to food and water.

Following the successful establishment of the model, 42 rats were randomly assigned into 7 groups, with 6 animals per group. The groups were as follows: Model group (Model, 10 ml⋅kg-1⋅d saline), LGZ+SIN low-dose group(LGZ 25 mg⋅kg-1⋅d+SIN 25 mg⋅kg-1⋅d),LGZ+SIN medium-dose group(LGZ 50 mg⋅kg-1⋅d+SIN 50 mg⋅kg-1⋅d), LGZ+SIN high-dose group (LGZ 25 mg⋅kg-1⋅d+SIN 25 mg⋅kg-1⋅d), Ligustrazine group (LGZ, 100 mg⋅kg⁻¹⋅d⁻¹), Sinomenine group (SIN, 100 mg⋅kg⁻¹⋅d⁻¹), Pregabalin positive control group (Pgb, 30 g⋅kg⁻¹⋅d⁻¹). In addition, 6 healthy rats were set as the sham operation group (Sham, 10ml⋅kg-1 saline). All animals were orally administered their respective treatments twice daily (morning and evening) for a period of three consecutive days.

4.2. Chemicals and Materials

The Easyflow independent ventilation cage was purchased from Tecniplast, Italy. The Von Frey filaments were obtained from Ugo Basile Biological Apparatus Conpany. The pain testing frame was made in our laboratory.

The HPLC-MS/MS system (AB Sciex, USA) comprised an ExionLC-20AC high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system, Ion DriveTM Turbo V ion source, Sciex 6500+ triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, Analyst 1.7 data acquisition software, and MultiQuant 3.0.3 data processing software. The Targin VX-III multi-tube vortexer was purchased from Beijing Tajin Technology Co., Ltd. The Forma 88000 Series −86°C ultra-low temperature freezer was obtained from Thermo Scientific (USA). The Rotanta 460R high-speed refrigerated centrifuge was acquired from Hettich (Germany). The MC-8 integrated cryogenic centrifuge concentrator was obtained from Beijing Jiaime Technology Co., Ltd. The Synergy2 multifunctional microplate reader was purchased from BioTek (USA). The desktop anesthetic machine was supplied by Harvard Apparatus (USA). The ThermoStar body temperature maintenance device was purchased from RWD Life Science Co., Ltd. The optical microscope (Olympus BX50) was purchased from Olympus Optical Co. (Tokyo, Japan).

Ligustrazine (Ligustrazine Hydrochloride, lot number: DT201803-19) and Sinomenine (Sinomenine Hydrochloride, lot number: DT201806-22), both with a purity ≥98% were provided by Shanxi Datian Biotechnology Ltd. (Xian, China). Pregabalin (lot number: 295422) was provided by Beijing Jiaime Technology Co., Ltd. The isoflurane (lot number: 217180801) was purchased from RWD Life Science Co., Ltd.

IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α ELISA kits were purchased from Raybiotech. The tissue lysis buffer (EL-lysis) was obtained from Raybiotech. The BCA protein assay kit was purchased from Thermo Fisher. The 4-0 chromic gut sutures were obtained from Shandong Boda Medical Products Co., Ltd.

Mass spectrometry library kits and reference standards for glucose metabolism, amino acids, bile acids, and others were purchased from Sigma for the establishment of a widely targeted metabolomics analysis platform in our laboratory. Internal standards, including d-3 norepinephrine, d-4 dopamine-D4, d-5 serotonin, and MSK-A2, were obtained from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. Reference standards for metabolic pathways, including tyrosine, sodium borate, benzoyl chloride, and d-5 benzoyl chloride were purchased from Sigma. All reference and internal standards had a purity greater than 99%. LC/MS-grade acetonitrile, methanol, formic acid, and ammonium formate were obtained from Beijing Dikema Technology Co., Ltd.

4.3. CCI Model Establishment

The CCI model in rats was established following the method described by Bennett [

21]. After anesthetizing the rats with isoflurane, they were placed on a heating pad to maintain a body temperature of approximately 37°C. The skin below the left femur was incised and the left sciatic nerve was exposed after blunt separation from the surrounding tissue. The nerve was then ligated with 4–0 chromic gut suture at four knots, each approximately 1 mm apart. The degree of ligation was adjusted to induce slight twitching of the calf muscles without compromising the blood supply to the nerve epineurium. In the sham group, the sciatic nerve was exposed but left unligated. The mechanical withdrawal threshold (MWT) test was conducted both prior to surgery and on day 7 post-surgery to assess the success of the model.

4.4. Pharmacodynamic Research

The body weight of the rats was recorded daily. Behavioral tests were conducted on days 1, 2, and 3 following drug administration. The behavioral tests included the MWT test, cold allodynia test, and incapacitance test. The MWT and cold allodynia test were conducted at 0, 0.5, 2, 4, and 6 hours following drug administration each day. The incapacitance test was conducted 4 hours following drug administration each day. After the final behavioral test, samples of the affected sciatic nerve were collected for hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) analysis. Plasma and CSF samples were also collected for subsequent metabolomic analysis.

The MWT test was assessed using Von Frey filaments[

39]. The rats were placed in a plastic chamber (20 cm×20 cm×15 cm) with a transparent acrylic lid and allowed to habituate for 30 minutes. Von Frey filaments ranging from 4 g to 26 g were used during the test. The "up-and-down" method was employed to determine the MWT value of each rat[

40].

The cold allodynia test was performed by spraying 0.1 mL of acetone on the affected hind paw of the rat. The responses of the rats, including paw withdrawal and licking behavior, were observed, and scored based on the degree of reaction: 0 points for no response; 1 point for mild reaction or rapid withdrawal of the hind paw; 2 points for repeated paw shaking; 3 points for sustained or repeated lifting and licking of the hind paw[

41].

The incapacitance test was conducted by placing the rats in a transparent box equipped with an inclined platform, where the rats stood on their hind feet. The left and right hind feet were position on separate sensor panels. Care was taken to ensure that the rats maintained an exploratory posture, without leaning against the sides of the box. A capacimeter was used to measure the weight (in grams) on each panel over a 3-second period. Each rat underwent three measurements, with a minimum of 1 minute between each reading. The average of the readings for each hind foot was used to calculate the weight distribution. The bipedal balance bearing value was recorded as the percentage of total body weight supported by each hind foot. In normal rats, weight distribution is nearly symmetrical (50:50%), whereas pain resulting from injury leads to a reduction in the load-bearing capacity of the injured hind foot. The bipedal balance b average earing result was calculated using the following formula: Result = Weight on the affected hind foot / (Weight on the left hind foot+ Weight on the right hind foot) ×100%[

42].

The sciatic nerve tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently embedded in paraffin to prepare 5 μm thick sections. The sections were stained with hematoxylin for 5 minutes, followed by eosin staining for 3 minutes. Changes in the sciatic nerve were observed using an optical microscope.

The concentrations of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the sciatic nerve were measured using ELISA. The experimental procedure was strictly adhered to, following the instructions provided with the kits. The final concentrations were corrected using the total protein content of the sciatic nerve.

4.5. Network Pharmacology Analysis

First, the potential targets of LGZ and SIN were identified using the SWISS Target Prediction database (

http://swisstargetprediction.ch/). These targets were then verified and refined using the UniProt database to obtain accurate target names for each compound. Subsequently, pain-related target information was obtained from the Genecards database (

https://www.genecards.org/) and the OMIM database (

https://omim.org/). After removing duplicates, the remaining targets were regarded as pain-related targets for further analysis. The intersection of LGZ and SIN alkaloid targets with those associated with pain was identified using the Bioinformatics platform (

http://www.bioinformatics.com.cn), yielding common genes across the different compounds. This gene set was then analyzed based on the distinctiveness of the drug-target interactions.

Next, the intersecting target genes were inputted into the STRING database to construct a Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network. The network was visualized using Cytoscape 3.8.2, and the CytoHubba plugin was employed to identify the core targets for further differential analysis.

Finally, the core target genes underwent Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis using the Metascape database. A significance threshold of P < 0.01 was set for all analyses. The GO analysis encompassed three subcategories: Biological Process (BP), Molecular Function (MF), and Cellular Component (CC). Furthermore, based on the relationships between protein targets and signaling pathways, a compound-target-pathway association network was constructed.

4.6. Plasma and CSF METABOLOMICS ANALYSIS

4.6.1. Plasma and CSF SAMPLE PREPARATION

For the sample preparation, 50 μL of the test sample was combined with 450 μL of ice-cold extraction solvent containing internal standards (methanol: acetonitrile: water = 2:2:1). The mixture was vortexed for 3 minutes, then placed at -20°C for 2 hours. Subsequently, the samples were centrifuged at 20,000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was carefully transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube and subjected to vacuum concentration at 35°C and 1,500 rpm for 2 hours. The residue was reconstituted with 100 μL of extraction solvent devoid of internal standards. The sample was centrifuged again at 20,000 g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and 80 μL of the supernatant was collected for analysis. Additionally, 10 μL of each sample was pipetted to pool a quality control (QC) sample.

4.6.2. Widely Targeted Metabolomics Analysis

Metabolites were identified using a self-established reference database. An ACQUITY UPLC BEH Amide column (2.1×50 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters, USA) and a pre-column (2.1 mm×5 mm, 1.7 μm, Waters) were used to separate samples. The mobile phase consisted of solvent A (95% water: 5% acetonitrile, containing 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.01% formic acid) and solvent B (95% acetonitrile: 5% water, containing 5 mM ammonium formate and 0.01% formic acid). The gradient elution program was as follows: 0-2 min, 95-95% B; 2-4 min, 95-90% B; 4-6 min, 90-90% B; 6-9 min, 90-85% B; 9-12 min, 85-85% B; 12-15 min, 85-75% B; 15-16 min, 75-75% B; 16-18 min, 75-50% B; 18-20 min, 50-50% B; 20-22 min, 50-25% B; 22-24 min, 25-25% B; 24-25 min, 25-95% B; 25-30 min, 95-95% B. Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min; column temperature: 35°C; temperature: 4°C; injection volume: 5 μL.

Electrospray ionization (ESI) was used as the ionization source. The curtain gas (N₂) was set to 40 psi, collision gas (N₂) to 9 psi, and the spray voltage was set at +5500 V and -4500 V for positive and negative ion modes, respectively. The nebulizer temperature was set to 550°C, with ion source gas (Ion Source Gas1, N₂) and auxiliary gas (Ion Source Gas2, N₂) both set to 55 psi. Scanning was performed in both positive and negative ion modes. Optimized ion pairs and mass spectrometry parameters were applied for each metabolite.

4.6.3. Targeted Metabolomics Analysis

The method for measuring the tyrosine pathway was adapted from previously published protocols[

43] with necessary modifications outlined below.

Sample preparation: A 50 μL aliquot of the sample was mixed with 150 μL of acetonitrile (1:3, v/v). The mixture was vortexed at 8,000 rpm for 5 minutes, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 10 minutes. Subsequently, 10 μL of the supernatant was transferred and added to 10 μL of 100 mM sodium borate and 10 μL of 1% benzoyl chloride. The mixture was vortexed for 5 minutes, incubated at 25°C for 5 minutes, and then centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 minutes. The resulting supernatant (24 μL) was mixed with 6 μL of an internal standard solution (a mixture of tyrosine pathway standards and d-5 benzoyl chloride for derivatization). The mixture was then vortexed and prepared for injection.

A PFP C18 column (2.1×50 mm, 1.8 μm, Waters, USA) was used to separate samples. Water with 0.1% formic acid and 5 mM ammonium formate served as mobile phase A and acetonitrile served as mobile phase B. The gradient programs were as follows: 0-1min, 20-20% B; 1-2min, 20-50% B; 2-6min, 50-80% B; 6-6.5min, 80-95% B; 8-8.1min, 95-20% B; 8.1-10min, 20-20% B. Flow rate: 0.3 mL/min; column temperature: 35°C; sample temperature: 4°C; injection volume: 2 μL.

Electrospray ionization (ESI) was used as the ionization source. The curtain gas (N₂) was set to 35 psi, collision gas (N₂) to 9 psi, and the spray voltage was set at 5500. The nebulizer temperature was set to 550°C, with ion source gas (Ion Source Gas1, N₂) and auxiliary gas (Ion Source Gas2, N₂) both at 55 psi. The analysis was performed in Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM) mode with positive ion scanning. The specific ion pair parameters used for the analysis are provided in

Supplementary Table S1.

4.6.4. Metabolomics Analysis

To ensure QC for the metabolomics analysis, a QC sample was injected after every ten experimental samples during the chromatography run. All LC-MS data underwent meticulous preprocessing using MultiQuant 3.0.3 software, including key steps such as peak detection, peak identification, peak area calculation, and calibration.

Principal component analysis (PCA) was first performed to reveal the major variability patterns within the datasets. Orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) was then applied to identify differentiate metabolites that might differentiate between groups. The quality of the OPLS-DA model was evaluated using the parameters R²Y and Q². Additionally, permutation testing was conducted to assess the risk of false positives in the OPLS-DA model. Potential biomarkers with significant statistical and biological relevance were selected based on the criteria: VIP > 1, t-test (

p) < 0.05, and fold change (FC) > 1.2 or < 0.83. Finally, metabolic pathways associated with the differentially expressed metabolites were determined using a significance threshold of

p < 0.05. The Metware Metabolomics Cloud Platform (

https://cloud.metware.cn/) and Metaboanalyst 6.0 (

https://www.metaboanalyst.ca/) were utilized to analyze the metabolomics data.

4.7. Joint Pathway Analysis

A joint pathway analysis was performed using the "Joint-Pathway Analysis" module in MetaboAnalyst 6.0 to correlate the key targets predicted by network pharmacology with the differential metabolites identified in the metabolomics analysis. Pathways that exhibited the highest enrichment of both targets and metabolites were considered as the key pathways.

4.8. Statistical Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed using SPSS 20.0 and GraphPad Prism 8.0. All data were shown as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The significance analysis of differences between two groups was assessed using a t-test, while multiple comparison was conducted using one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance, and p < 0.01 indicated highly statistical significance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tao Li, Zhiguo Wang, Zhaoyue Yuan; methodology, Tao Li, Zhaoyue Yuan, Xiaoliang Zhao, Jidan Zhang, Yanyan Ma; software, Zhaoyue Yuan; validation, Xiaoliang Zhao; formal analysis, Xiaoliang Zhao, Yue Jiao and Yang Liu; writing—original draft preparation, Zhaoyue Yuan and Yan Zhang; investigation, Yan Zhang; resources, Chang Gao; data curation, Zhaoyue Yuan; supervision, Chang Gao, Zhiguo Wang; writing—review and editing, Tao Li, Zhaoyue Yuan and Yan Zhang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.