Submitted:

16 September 2025

Posted:

17 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

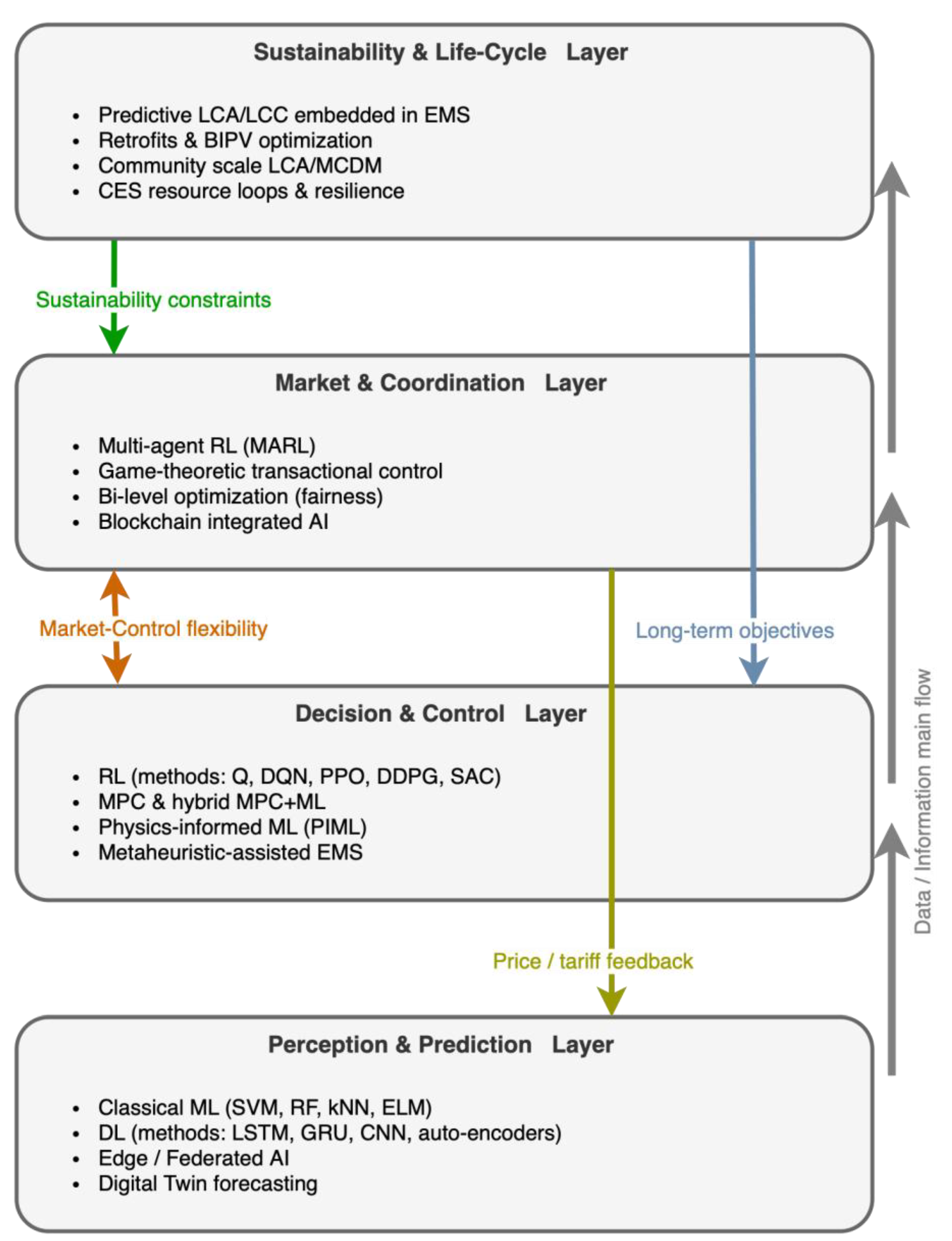

- AI methods should evolve from isolated predictors and controllers toward layered frameworks that combine perception, control, and market coordination;

- Lifecycle and sustainability dimensions remain insufficiently embedded in these frameworks, especially transactive processes, resulting in a structural gap between operational efficiency and long-term resilience;

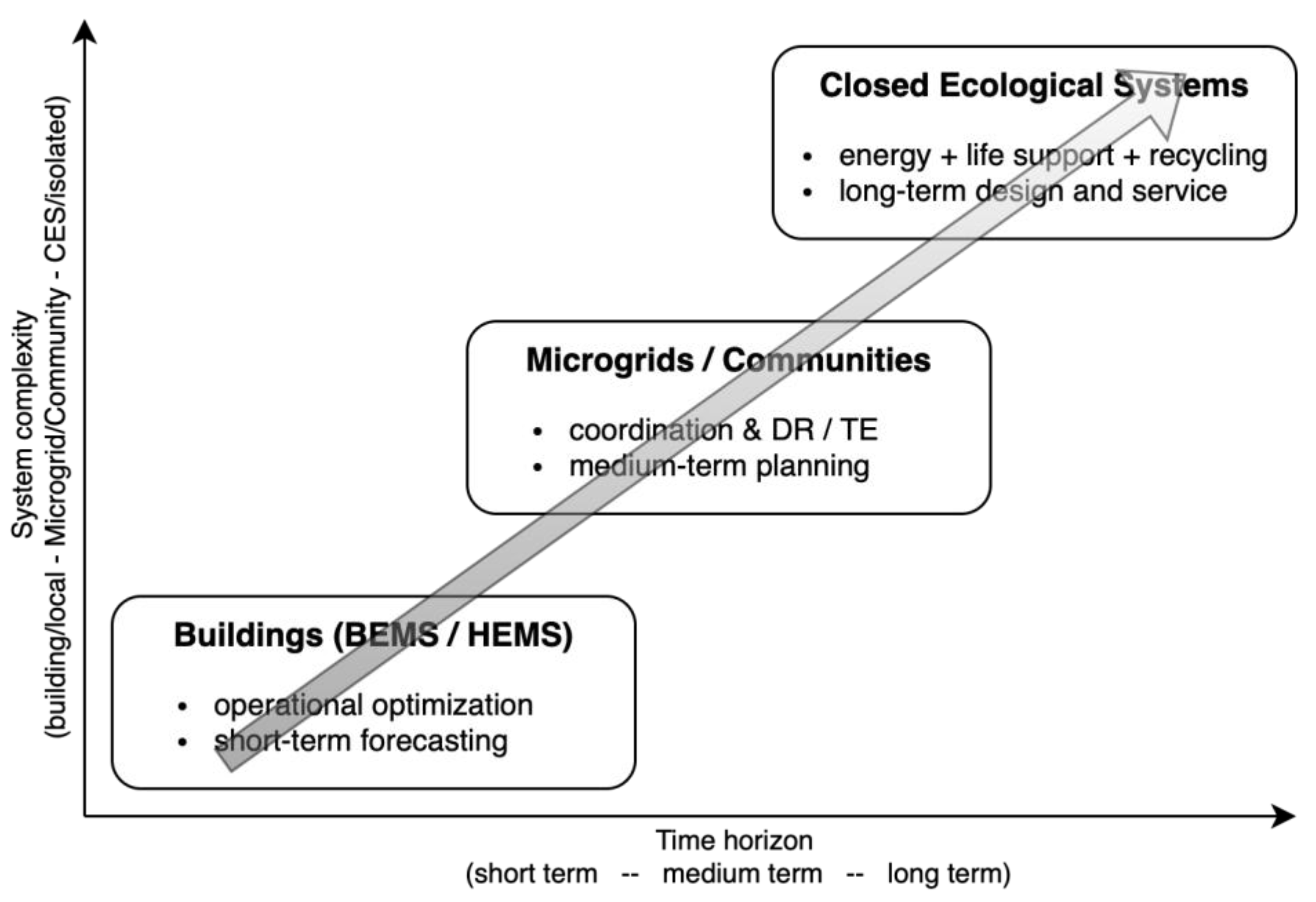

- Emerging application domains, such as CES, while not central to this review, offer valuable opportunities to stress-test building and microgrid concepts under extreme resource constraints.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Search Approach and Queries

- AI + Transactive/Peer-to-Peer Energy WoS example: TS=("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning" OR "deep learning" OR "reinforcement learning" OR AI) AND TS=("transactive energy" OR "peer-to-peer energy" OR "P2P energy") AND PY=2015-2025;

- AI + Smart Local Energy Systems / Microgrids WoS example: TS=("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning" OR "deep learning" OR "reinforcement learning" OR AI) AND TS=("local energy system" OR "smart local energy system" OR "smart microgrid") AND PY=2015-2025;

- AI + Life Cycle Assessment / Life Cycle Cost + Buildings WoS example: TS=("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning" OR "deep learning" OR "reinforcement learning" OR AI) AND TS=("life cycle assessment" OR "life cycle cost" OR "LCA" OR "LCC") AND TS=("building" OR "buildings") AND PY=2015-2025

-

AI + Sustainable / Smart / Green Buildings and Energy Performance WoS example: TS=("artificial intelligence" OR "machine learning" OR "deep learning"OR "reinforcement learning" OR AI) AND TS=("sustainable building" OR "building energy performance") AND PY=2015-2025.

2.2. Initial Identification

2.3. Screening and Eligibility

- Stage 1 – Basic merging: Publications were retained only if they were present in both databases (WoS and Scopus), included a valid DOI, and had complete metadata (e.g., authorship information). This step reduced the dataset to 614 publications;

- Stage 2 – Thematic filtering: Abstracts and keywords were screened for explicit relevance to energy management in buildings, leaving 306 publications;

- Stage 3 – Content-based filtering: Works outside the technical scope of this review were excluded, such as purely economic market models, forecasting without EMS/building context, or sustainability assessments without AI.

2.4. Special Consideration for Set 3 of Records Related to LCA/LCC and Buildings

- Research perspective – to capture the state of the art in LCA/LCC for buildings and to understand how these methods are currently applied in relation to energy management, even if not always explicitly AI-driven;

- Original contribution – to highlight a gap and research opportunity where AI techniques can complement and extend traditional LCA/LCC approaches, particularly by enabling dynamic, predictive, and data-driven assessments in building energy systems.

3. Results

3.1. General Overview of the Reviewed Publications

3.2. Research on Transactive Energy

3.2.1. Concepts and Market Designs

3.2.2. Implementations in Microgrids and Local Energy Systems

3.2.3. AI methods for TE Coordination and Trading

3.2.4. Evaluation Criteria: Welfare, Fairness, and Grid Constraints

3.2.5. Evaluation Criteria: Welfare, Fairness, and Grid Constraints

3.2.6. Identified Gaps and Future Directions

3.3. Research on Dynamic Energy Management

3.3.1. Scope and Reference DEM Architectures

3.3.2. DSM/DSR and Flexible Asset Coordination with RL

3.3.3. Forecast-Informed Control Loops

3.3.4. Control Strategies Beyond Pure RL: MPC, Hybrid and Physics-Informed Tracks

3.4. AI methods and Techniques Applied Across TE and DEM

3.4.1. Perception and Prediction Layer: From Classical ML to Edge-AI and DT

3.4.2. Decision-Making and Control Layer (DEM – Oriented)

3.4.3. Market-Level Coordination Layer (TE – Oriented)

3.4.4. Distributed and Secure AI Frameworks: From FL to Hybrid Optimization and DT

3.5. Complementary AI and Life Cycle Perspectives for Sustainable Buildings

3.5.1. AI for Dynamic and Predictive LCA/LCC in Building Energy Systems

3.5.2. Retrofit and Building-Integrated PV: AI-Enabled Life-Cycle Optimization

3.5.3. Community and District Energy Systems: Life-Cycle Anchors for AI-Driven Microgrids

3.5.4. Community and District Energy Systems: Life-Cycle Anchors for AI-Driven Microgrids

4. Discussion

4.1. Integrative View on AI in TE, DEM, and Life-Cycle Perspectives

4.2. Conceptual Gaps and Methodological Challenges

4.3. Cross-Domain Insights: From Buildings to Microgrids to CES

4.4. Towards a Multi-Layered AI Framework for Sustainable Energy Systems

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A2C | Advantage Actor-Critic |

| A3C | Asynchronous Advantage Actor-Critic |

| AC | Alternating Current |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| ANN | Artificial Neural Network |

| BACS | Building Automation and Control Systems |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| BIPV | Building Integrated Photovoltaic |

| BMS | Building Management System |

| CES | Closed Ecological Systems |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DC | Direct Current |

| DDPG | Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient |

| DEM | Dynamic Energy Management |

| DERs | Distributed Energy Resources |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| DLT | Distributed Ledger Technology |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| DSM | Demand Side Management |

| DSO | Distribution System Operator |

| DSR | Demand Side Response |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| EMS | Energy Management Systems |

| EUI | Energy Use Intensity |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| GRU | Gated Recurrent Unit |

| HEMS | Home Energy Management System |

| HGSOA | Hybrid Gazelle and Seagull Optimization Algorithm |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, Air Condition |

| IDS | Intrusion Detection System |

| IMRAD | Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| kNN | k-Nearest Neighbors |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCC | Life Cycle Cost |

| LCSA | Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment |

| LSTM | Long-Short Term Memory |

| MARL | Multiagent Reinforcement Learning |

| MBC | Model Based Control |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision-Making |

| MILP | Mixed-Integer Linear Programming |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| MOO | Multi-Objective Optimization |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| NILM | Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring |

| NMGs | Networked Microgrids |

| P2P | Peer-to-peer |

| PIML | Physics-Informed Machine Learning |

| POMDP | Partially Observable Markov Decision Process |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RES | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RF | Random Forest |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| TE | Transactive Energy |

| TESP | Transactive Energy Simulation Platform |

| TRPO | Trust Region Policy Optimization |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| XAI | Explainable Artificial Intelligence |

References

- Mutluri, R.B.; Saxena, D. A Comprehensive Overview and Future Prospectives of Networked Microgrids for Emerging Power Systems. Smart Grids and Sustainable Energy 2024, 9, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arévalo, P.; Benavides, D.; Ochoa-Correa, D.; Ríos, A.; Torres, D.; Villanueva-Machado, C.W. Smart Microgrid Management and Optimization: A Systematic Review Towards the Proposal of Smart Management Models. Algorithms 2025, 18, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, T.; Deng, H.; Wang, P.; Liu, J.; Blaabjerg, F. Microgrid Energy Management with Energy Storage Systems: A Review. CSEE Journal of Power and Energy Systems 2023, 9, 483–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomari, Y.; Aspetakis, G.; Mateu, C.; Shobo, A.; Boer, D.; Marín-Genescà, M.; Wang, Q. A Hybrid Data-Driven Co-Simulation Approach for Enhanced Integrations of Renewables and Thermal Storage in Building District Energy Systems. Journal of Building Engineering 2025, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhayalan, V.; Raman, R.; Kalaivani, N.; Shrirvastava, A.; Reddy, R.S.; Meenakshi, B. Smart Renewable Energy Management Using Internet of Things and Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Computer, Communication and Control (IC4), February 8 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Barbierato, L.; Salvatore Schiera, D.; Orlando, M.; Lanzini, A.; Pons, E.; Bottaccioli, L.; Patti, E. Facilitating Smart Grids Integration Through a Hybrid Multi-Model Co-Simulation Framework. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 104878–104897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Saleh, A.M.; Waseem, M.; Sajjad, I.A. Artificial Intelligence Enabled Demand Response: Prospects and Challenges in Smart Grid Environment. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 1477–1505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saadi, M.; Al-Greer, M.; Short, M. Reinforcement Learning-Based Intelligent Control Strategies for Optimal Power Management in Advanced Power Distribution Systems: A Survey. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caggiano, M.; Semeraro, C.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Al-Alami, A.H.; Olabi, A.-G.; Dassisti, M. The Role of Industry 5.0 in the Energy System: A Conceptual Framework. Energy Sources, Part A: Recovery, Utilization, and Environmental Effects 2025, 47, 52–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, S.D.; Garcia, V.J. Transactive Energy in Microgrid Communities: A Systematic Review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2023, 171, 112999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X. Towards Transactive Energy: An Analysis of Information-related Practical Issues. Energy Conversion and Economics 2022, 3, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venayagamoorthy, G.K.; Sharma, R.K.; Gautam, P.K.; Ahmadi, A. Dynamic Energy Management System for a Smart Microgrid. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2016, 27, 1643–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arun, S.L.; Selvan, M.P. Intelligent Residential Energy Management System for Dynamic Demand Response in Smart Buildings. IEEE Syst J 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, R.; Mu, C.; Zhang, X.; Ding, Z.; Sun, C. Review of Home Energy Management Systems Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings - 2023 38th Youth Academic Annual Conference of Chinese Association of Automation, YAC 2023; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., 2023; pp. 1239–1244. [Google Scholar]

- Ożadowicz, A. A New Concept of Active Demand Side Management for Energy Efficient Prosumer Microgrids with Smart Building Technologies. Energies (Basel) 2017, 10, 1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shayeghi, H.; Shahryari, E.; Moradzadeh, M.; Siano, P. A Survey on Microgrid Energy Management Considering Flexible Energy Sources. Energies (Basel) 2019, 12, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, M.; Huang, Q.; Amin, W.; Umer, K.; Raza, A.; Naeem, M. Blockchain Enabled Distributed Demand Side Management in Community Energy System With Smart Homes. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 37428–37439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, A.A.; Shaban, K.; Massoud, A.M. DRL-HEMS: Deep Reinforcement Learning Agent for Demand Response in Home Energy Management Systems Considering Customers and Operators Perspectives. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2023, 14, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latoń, D.; Grela, J.; Ożadowicz, A. Applications of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Home Energy Management Systems: A Review. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17, 6420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczyk, G.; Ożadowicz, A. Moving Forward in Effective Deployment of the Smart Readiness Indicator and the ISO 52120 Standard to Improve Energy Performance with Building Automation and Control Systems. Energies (Basel) 2025, 18, 1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samaras, P.; Stamatopoulos, E.; Arsenopoulos, A.; Sarmas, E.; Marinakis, E. Readiness to Adopt the Smart Readiness Indicator Scheme Across Europe: A Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for Living Environment (MetroLivEnv), June 12 2024; IEEE; pp. 268–273. [Google Scholar]

- Calotă, R.; Bode, F.; Souliotis, M.; Croitoru, C.; Fokaides, P.A. Bridging the Gap: Discrepancies in Energy Efficiency and Smart Readiness of Buildings. Energy Reports 2024, 12, 5886–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, M.T.; Koukaras, P.; Ioannidis, D.; Tjortjis, C. SmartBuild RecSys: A Recommendation System Based on the Smart Readiness Indicator for Energy Efficiency in Buildings. Algorithms 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Märzinger, T.; Österreicher, D. Supporting the Smart Readiness Indicator—A Methodology to Integrate A Quantitative Assessment of the Load Shifting Potential of Smart Buildings. Energies (Basel) 2019, 12, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, M.; Andreas, J.; Mai, T.L.; Kabitzsch, K. Towards a Comprehensive Life Cycle Approach of Building Automation Systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Industrial Electronics (ISIE), June 2017; IEEE; pp. 1541–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Yan, X. A Review of Buildings Dynamic Life Cycle Studies by Bibliometric Methods. Energy Build 2025, 332, 115453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakalis, D.; Hellwig, R.T.; Schweiker, M.; Gauthier, S. Challenges and Opportunities of Internet-of-Things in Occupant-Centric Building Operations: Towards a Life Cycle Assessment Framework. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 2023, 65, 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavan, F.; Maalek, R.; Toğan, V. Structural Optimization of Trusses in Building Information Modeling (BIM) Projects Using Visual Programming, Evolutionary Algorithms, and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) Tools. Buildings 2024, 14, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, A.; Samadzadegan, B.; Rasoulian, H.; Ranjbar, S.; Abolhassani, S.S.; Sanei, A.; Eicker, U. A New Modeling Approach for Low-Carbon District Energy System Planning. Energies (Basel) 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzikonstantinidis, K.; Giama, E.; Fokaides, P.A.; Papadopoulos, A.M. Smart Readiness Indicator (SRI) as a Decision-Making Tool for Low Carbon Buildings. Energies (Basel) 2024, 17, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Anwer, S.; Mehmood, I.; Umer, W.; Mohandes, S.R.; Wuni, I.Y.; Abdul-Rahman, M.; Li, H. Artificial Intelligence in Net-Zero Carbon Emissions for Sustainable Building Projects: A Systematic Literature and Science Mapping Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazmohammadi, N.; Madary, A.; Vasquez, J.C.; Guerrero, J.M. New Horizons for Control and Energy Management of Closed Ecological Systems: Insights and Future Trends. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2025, 19, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciurans, C.; Bazmohammadi, N.; Vasquez, J.C.; Dussap, G.; Guerrero, J.M.; Godia, F. Hierarchical Control of Space Closed Ecosystems: Expanding Microgrid Concepts to Bioastronautics. IEEE Industrial Electronics Magazine 2021, 15, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeulen, A.C.J.; Papic, A.; Nikolic, I.; Brazier, F. Stoichiometric Model of a Fully Closed Bioregenerative Life Support System for Autonomous Long-Duration Space Missions. Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ożadowicz, A. Modeling and Simulation Tools for Smart Local Energy Systems: A Review with a Focus on Emerging Closed Ecological Systems’ Application. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 9219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arwa, E.O.; Folly, K.A. Reinforcement Learning Techniques for Optimal Power Control in Grid-Connected Microgrids: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 208992–209007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Du, H.; Xue, S.; Ma, Z. Recent Advances in Data Mining and Machine Learning for Enhanced Building Energy Management. Energy 2024, 307, 132636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Akcakaya, M.; Mcdermott, T.E. Automated Control of Transactive HVACs in Energy Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2021, 12, 2462–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholizadeh, N.; Abedi, M.; Nafisi, H.; Marzband, M.; Loni, A.; Putrus, G.A. Fair-Optimal Bilevel Transactive Energy Management for Community of Microgrids. IEEE Syst J 2022, 16, 2125–2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Battula, S.; Singh, S.N. Transactive Electric Vehicle Agent: A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting (PESGM), July 21 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Gupta, B.B.; Tian, Z. An Edge-AI Based Forecasting Approach for Improving Smart Microgrid Efficiency. IEEE Trans Industr Inform 2022, 18, 7946–7954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayer, D.R.; Haag, F.; Pruckner, M.; Hopf, K. Electricity Demand Forecasting in Future Grid States: A Digital Twin-Based Simulation Study. In Proceedings of the 2024 9th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech), June 25 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Cho, K.; Choi, M. A Sustainability Evaluation of Buildings: A Review on Sustainability Factors to Move towards a Greener City Environment. Buildings 2024, 14, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Guo, J.; Lin, P.; Tiong, R.L.K. Detecting Energy Consumption Anomalies with Dynamic Adaptive Encoder-Decoder Deep Learning Networks. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 207, 114975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Duan, Q.; Samadi, F. A Systematic Review of Building Energy Performance Forecasting Approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2025, 223, 116061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amasyali, K.; Chen, Y.; Olama, M. A Data-Driven, Distributed Game-Theoretic Transactional Control Approach for Hierarchical Demand Response. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 72279–72289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Long, C.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, C. Performance Evaluation of Peer-to-Peer Energy Sharing Models. Energy Procedia 2017, 143, 817–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Brookson, A.; Fung, A.S.; Raahemifar, K.; Mohammadi, F. Transactive Control of a Residential Community with Solar Photovoltaic and Battery Storage Systems. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2019, 238, 012051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Akcakaya, M.; McDermott, T.E. Reduced Order Model of Transactive Bidding Loads. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2022, 13, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Liu, N.; Tan, L.; Han, J. Data-driven Energy Sharing for Multi-microgrids with Building Prosumers: A Hybrid Learning Approach. IET Renewable Power Generation 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Mendes, N.; Rasouli, S.; Mohammadi, J.; Moura, P. Federated Learning Assisted Distributed Energy Optimization. IET Renewable Power Generation 2024, 18, 2524–2538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Krishnan, V.V.G.; Pi, J.; Kaur, K.; Srivastava, A.; Hahn, A.; Suresh, S. Cyber Physical Security Analytics for Transactive Energy Systems. IEEE Trans Smart Grid 2020, 11, 931–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, M.; Biletskiy, Y. Smart Microgrid Architecture For Home Energy Management System. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), October 10 2021; IEEE; pp. 808–813. [Google Scholar]

- Nammouchi, A.; Aupke, P.; Kassler, A.; Theocharis, A.; Raffa, V.; Felice, M. Di Integration of AI, IoT and Edge-Computing for Smart Microgrid Energy Management. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2021 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe), September 7 2021; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarsheth, S.; Agbossou, K.; Henao, N.; Bendouma, M. The Advancements in Agricultural Greenhouse Technologies: An Energy Management Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, S.; Mehran, K. Reinforcement Learning Based Optimal Energy Management of A Microgrid. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), October 9 2022; IEEE; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dridi, A.; Boucetta, C.; Moungla, H.; Afifi, H. Deep Recurrent Learning versus Q-Learning for Energy Management Systems in Next Generation Network. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Global Communications Conference (GLOBECOM), December 2021; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Darshi, R.; Shamaghdari, S.; Jalali, A.; Arasteh, H. Decentralized Energy Management System for Smart Microgrids Using Reinforcement Learning. IET Generation, Transmission & Distribution 2023, 17, 2142–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadrian Zadeh, D.; Moshiri, B.; Abedini, M.; Guerrero, J.M. Supervised Learning for More Accurate State Estimation Fusion in IoT-Based Power Systems. Information Fusion 2023, 96, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiris, V.; Awagan, G.; Jiang, J. A Machine Learning Approach for the Identification of Photovoltaic and Electric Vehicle Profiles in a Smart Local Energy System. In Proceedings of the 2024 59th International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), September 2 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.-H.; Yang, S.; You, F. Thermal Comfort Control on Sustainable Building via Data-Driven Robust Model Predictive Control. In Proceedings of the 2023 American Control Conference (ACC), May 31 2023; IEEE; pp. 591–596. [Google Scholar]

- Renganayagalu, S.K.; Bodal, T.; Bryntesen, T.-R.; Kvalvik, P. Optimising Energy Performance of Buildings through Digital Twins and Machine Learning: Lessons Learnt and Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence (ICAPAI), April 16 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Aruta, G.; Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. Optimizing Heating Operation via GA- and ANN-Based Model Predictive Control: Concept for a Real Nearly-Zero Energy Building. Energy Build 2023, 292, 113139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Jiang, G.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J. A Review of Physics-Informed Machine Learning for Building Energy Modeling. Appl Energy 2025, 381, 125169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Zhou, N.; Feng, X.; Abdolhosseinzadeh, S. Optimizing Space Heating Efficiency in Sustainable Building Design a Multi Criteria Decision Making Approach with Model Predictive Control. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 27743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Ooka, R.; Ikeda, S.; Choi, W.; Kwak, Y. Model Predictive Control of Building Energy Systems with Thermal Energy Storage in Response to Occupancy Variations and Time-Variant Electricity Prices. Energy Build 2020, 225, 110291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Zhao, J. Multi-Regional Building Energy Efficiency Intelligent Regulation Strategy Based on Multi-Objective Optimization and Model Predictive Control. J Clean Prod 2022, 349, 131264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, R.; Cavone, G.; Dotoli, M.; Epicoco, N.; Scarabaggio, P. Model Predictive Control for Thermal Comfort Optimization in Building Energy Management Systems. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), October 2019; IEEE; pp. 2608–2613. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Chen, W.; Wan, M.P. A Machine-Learning-Based Event-Triggered Model Predictive Control for Building Energy Management. Build Environ 2023, 233, 110101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Zabala, V.F.; Gómez-Acebo, T. Building Energy Performance Metamodels for District Energy Management Optimisation Platforms. Energy Conversion and Management: X 2024, 21, 100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, F.J.V.; Segura Manzano, F.; Andújar Márquez, J.M.; Calderón Godoy, A.J. Extended Model Predictive Controller to Develop Energy Management Systems in Renewable Source-Based Smart Microgrids with Hydrogen as Backup. Theoretical Foundation and Case Study. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chen, J. Applications and Trends of Machine Learning in Building Energy Optimization: A Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings 2025, 15, 994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, P.; Hoare, C.; O’Donnell, J. Building Occupancy Detection and Localization Using CCTV Camera and Deep Learning. IEEE Internet Things J 2023, 10, 597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challa, K.; AlHmoud, I.W.; Kamrul Islam, A.K.M.; Graves, C.A.; Gokaraju, B. Comprehensive Energy Efficiency Analysis in Buildings Using Drone Thermal Imagery, Real-Time Indoor Monitoring, and Deep Learning Techniques. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 65094–65104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almadhor, A.; Alsubai, S.; Kryvinska, N.; Ghazouani, N.; Bouallegue, B.; Al Hejaili, A.; Sampedro, G.A. A Synergistic Approach Using Digital Twins and Statistical Machine Learning for Intelligent Residential Energy Modelling. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 26088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasebinia, F.; Lin, L.; Wu, S.; Kang, Y.; Sepasgozar, S. Exploring the Benefits and Limitations of Digital Twin Technology in Building Energy. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 8814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Yi, Z.; Shi, D.; Huang, Z. Optimizing Grid Services: A Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Approach for Demand-Side Resource Aggregation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Europe (ISGT EUROPE), October 14 2024; IEEE; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Dridi, A.; Afifi, H.; Moungla, H.; Badosa, J. A Novel Deep Reinforcement Approach for IIoT Microgrid Energy Management Systems. IEEE Transactions on Green Communications and Networking 2022, 6, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Aral, A.; Brandic, I.; Erol-Kantarci, M. Multiagent Bayesian Deep Reinforcement Learning for Microgrid Energy Management Under Communication Failures. IEEE Internet Things J 2022, 9, 11685–11698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Yun, H.; Rayhana, R.; Bin, J.; Zhang, C.; Herrera, O.E.; Liu, Z.; Mérida, W. An Adaptive Federated Learning System for Community Building Energy Load Forecasting and Anomaly Prediction. Energy Build 2023, 295, 113215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharehveran, S.S.; Shirini, K.; Khavar, S.C.; Mousavi, S.H.; Abdolahi, A. Deep Learning-Based Demand Response for Short-Term Operation of Renewable-Based Microgrids. J Supercomput 2024, 80, 26002–26035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadri, H. AI-Driven Integration of Digital Twins and Blockchain for Smart Building Management Systems: A Multi-Stage Empirical Study. Journal of Building Engineering 2025, 105, 112439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Um-e-Habiba; Ahmed, I.; Asif, M.; Alhelou, H.H.; Khalid, M. A Review on Enhancing Energy Efficiency and Adaptability through System Integration for Smart Buildings. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 89, 109354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooki, O.O.; Popoola, O.M. A Critical Review on Intelligent-Based Techniques for Detection and Mitigation of Cyberthreats and Cascaded Failures in Cyber-Physical Power Systems. Renewable Energy Focus 2024, 51, 100628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, B.; Jolfaei, A.; Tariq, M. Experience-Driven Attack Design and Federated-Learning-Based Intrusion Detection in Industry 4.0. IEEE Trans Industr Inform 2022, 18, 6398–6405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thulasiraman, P.; Hackett, M.; Musgrave, P.; Edmond, A.; Seville, J. Anomaly Detection in a Smart Microgrid System Using Cyber-Analytics: A Case Study. Energies (Basel) 2023, 16, 7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manbachi, M.; Hammami, M. Virtualized Experiential Learning Platform (VELP) for Smart Grids and Operational Technology Cybersecurity. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Reality (ICIR), December 2022; IEEE; pp. 54–57. [Google Scholar]

- Manbachi, M.; Nayak, J.; Hammami, M.; Bucio, A.G. Virtualized Experiential Learning Platform for Substation Automation and Industrial Control Cybersecurity. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Electrical Power and Energy Conference (EPEC), December 5 2022; IEEE; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kadechkar, A.; Grigoryan, H. FMEA 2.0: Machine Learning Applications in Smart Microgrid Risk Assessment. In Proceedings of the 2024 12th International Conference on Smart Grid (icSmartGrid), May 27 2024; IEEE; pp. 629–635. [Google Scholar]

- Amir, M.; Zaheeruddin; Haque, A.; Kurukuru, V.S.B.; Bakhsh, F.I.; Ahmad, A. Agent Based Online Learning Approach for Power Flow Control of Electric Vehicle Fast Charging Station Integrated with Smart Microgrid. IET Renewable Power Generation 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.C.; Baskaran, S.; Marimuthu, P. Cost Analysis Using Hybrid Gazelle and Seagull Optimization for Home Energy Management System. Electrical Engineering 2025, 107, 1441–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Hao, N.; Li, X.; Alshahrani, M.Y. AI-Enabled Sports-System Peer-to-Peer Energy Exchange Network for Remote Areas in the Digital Economy. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenninger, S.; Wiethe, C. Benchmarking Energy Quantification Methods to Predict Heating Energy Performance of Residential Buildings in Germany. Business & Information Systems Engineering 2021, 63, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Han, P.; Duan, Y.; Alden, R.E.; Rallabandi, V.; Ionel, D.M. Residential Electrical Load Monitoring and Modeling – State of the Art and Future Trends for Smart Homes and Grids. Electric Power Components and Systems 2020, 48, 1125–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Fannon, D.; Eckelman, M.J. Predictive Modeling for US Commercial Building Energy Use: A Comparison of Existing Statistical and Machine Learning Algorithms Using CBECS Microdata. Energy Build 2018, 163, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Ahn, K.; Park, C. Issues of Application of Machine Learning Models for Virtual and Real-Life Buildings. Sustainability 2016, 8, 543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, S.; Kontokosta, C.E. Grading Buildings on Energy Performance Using City Benchmarking Data. Appl Energy 2019, 233–234, 244–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. A Hybrid Deep Learning and Clonal Selection Algorithm-Based Model for Commercial Building Energy Consumption Prediction. Sci Prog 2024, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Dong, Z.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Xie, Y.; Li, K. Quantitative Evaluation of the Building Energy Performance Based on Short-Term Energy Predictions. Energy 2021, 223, 120065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srividhya, J.P.; Prabha, K.E.L.; Jaisiva, S.; Rajan, C.S.G. Power Quality Enhancement in Smart Microgrid System Using Convolutional Neural Network Integrated with Interline Power Flow Controller. Electrical Engineering 2024, 106, 6773–6796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Nagy, Z.; Goffin, P.; Schlueter, A. Reinforcement Learning for Optimal Control of Low Exergy Buildings. Appl Energy 2015, 156, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; O’Neill, Z. An Innovative Fault Impact Analysis Framework for Enhancing Building Operations. Energy Build 2019, 199, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosa, A.C.; Mateu, C.; Haddad, A.; Boer, D. Data-Augmented Deep Learning Models for Assessing Thermal Performance in Sustainable Building Materials. Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems 2025, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xia, B. Application of Machine Learning Algorithms Based on Active Learning Strategies and Interpretable Models for HVAC System Energy Consumption Prediction. Engineering Reports 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Chen, C.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X. Linking Human-Building Interactions in Shared Offices with Personality Traits. Build Environ 2020, 170, 106602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wu, Y.; Liu, W.; Xue, T.; Xu, J. A New Synthesized Framework of Artificial Neural Network-Based Sensitivity Analysis for Building Energy Performance: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Build Environ 2025, 283, 113290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemmatabady, H.; Welsch, B.; Formhals, J.; Sass, I. AI-Based Enviro-Economic Optimization of Solar-Coupled and Standalone Geothermal Systems for Heating and Cooling. Appl Energy 2022, 311, 118652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnaser, A.A.; Maxi, M.; Elmousalami, H. AI-Powered Digital Twins and Internet of Things for Smart Cities and Sustainable Building Environment. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 12056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.A.; Hammad, A. Developing Surrogate ANN for Selecting Near-Optimal Building Energy Renovation Methods Considering Energy Consumption, LCC and LCA. Journal of Building Engineering 2019, 25, 100790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini Toosi, H.; Del Pero, C.; Leonforte, F.; Lavagna, M.; Aste, N. Machine Learning for Performance Prediction in Smart Buildings: Photovoltaic Self-Consumption and Life Cycle Cost Optimization. Appl Energy 2023, 334, 120648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, N.; Li, L.; Xu, C. Multi-Objective Optimization of a Hybrid PVT Assisted Ground Source and Air Source Heat Pump System for Large Space Buildings Using Transient Metamodel. Energy 2025, 328, 136473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elomari, Y.; Mateu, C.; Marín-Genescà, M.; Boer, D. A Data-Driven Framework for Designing a Renewable Energy Community Based on the Integration of Machine Learning Model with Life Cycle Assessment and Life Cycle Cost Parameters. Appl Energy 2024, 358, 122619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abokersh, M.H.; Vallès, M.; Cabeza, L.F.; Boer, D. A Framework for the Optimal Integration of Solar Assisted District Heating in Different Urban Sized Communities: A Robust Machine Learning Approach Incorporating Global Sensitivity Analysis. Appl Energy 2020, 267, 114903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Tønnesen, J.; Caetano, L.; Bergsdal, H.; Justo Alonso, M.; Kind, R.; Georges, L.; Mathisen, H.M. Optimizing Ventilation Systems Considering Operational and Embodied Emissions with Life Cycle Based Method. Energy Build 2024, 325, 115040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y. Prediction and Optimization Analysis of the Performance of an Office Building in an Extremely Hot and Cold Region. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.A.; Hammad, A.; Eshraghi, P. Generation of Whole Building Renovation Scenarios Using Variational Autoencoders. Energy Build 2021, 230, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tharushi Imalka, S.; Yang, R.J.; Zhao, Y. Machine Learning Driven Building Integrated Photovoltaic (BIPV) Envelope Design Optimization. Energy Build 2024, 324, 114882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Yang, G.; Bian, C.; Long, L.; Wang, X.; Gao, C.; Wong, C.L.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Chen, X.; et al. Autonomous Design Framework for Deploying Building Integrated Photovoltaics. Appl Energy 2025, 377, 124760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, T.; Hutsol, T.; Vlasovets, V.; Glowacki, S.; Nurek, T.; Horetska, I.; Kukharets, S.; Firman, Y.; Bilovod, O. Ensemble Learning Based Sustainable Approach to Rebuilding Metal Structures Prediction. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abokersh, M.H.; Gangwar, S.; Spiekman, M.; Vallès, M.; Jiménez, L.; Boer, D. Sustainability Insights on Emerging Solar District Heating Technologies to Boost the Nearly Zero Energy Building Concept. Renew Energy 2021, 180, 893–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanya, D.; Paulillo, A.; Fiorini, S.; Lettieri, P. Evaluating Sustainable Building Assessment Systems: A Comparative Analysis of GBRS and WBLCA. Front Built Environ 2025, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, A.K.; Edwards, D.J.; Adjei, E.K.; Adjei-Kumi, T.; Owusu-Manu, D.-G.; Fianoo, S.I.; Thwala, W.D. Analysis of the Underlying Factors Affecting BIM-LCA Integration in the Ghanaian Construction Industry: A Factor Analysis Approach. Construction Innovation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhang, D.; Qin, H.; Tang, J. Bridging the Last-Mile Gap in Network Security via Generating Intrusion-Specific Detection Patterns through Machine Learning. Security and Communication Networks 2022, 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y. The Technological Assessment of Green Buildings Using Artificial Neural Networks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e36400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Set of Records | Thematic Area | Web of Science | Scopus | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AI + Transactive/Peer-to-Peer Energy | 189 | 322 | 511 |

| 2 | AI + Smart Local Energy Systems / Microgrids | 53 | 122 | 175 |

| 3 | AI + Life Cycle Assessment / Life Cycle Cost + Buildings |

149 | 211 | 360 |

| 4 | AI + Sustainable / Smart / Green Buildings and Energy Performance |

324 | 713 | 1,055 |

| Total | 715 | 1,386 | 2,101 |

| Criterion | Included if… | Excluded if… |

|---|---|---|

| Source quality | Record indexed in WoS or Scopus, with complete metadata and DOI. |

Record without DOI, missing authors, or incomplete metadata. |

| Topical scope | Explicit mention of energy management in buildings (including Heating, Ventilation, Air Condition (HVAC), lighting, microgrids, Energy Management Systems, Demand Side Response (EMS/DSR), building performance). |

Focus exclusively on unrelated domains (e.g., mobility, large-scale grid operations). |

| AI relevance | AI techniques explicitly applied (Machine Learning - ML, Deep Learning - DL, Reinforcement Learning - RL, etc.) to energy-related functions in buildings or local microgrids. | No AI component, or purely conceptual without technical application. |

| Application domain | EMS, DSM, DSR, predictive control, optimization, building energy performance, sustainability with AI. |

Purely economic/market models (auctions, bidding, trading) without EMS/control aspects. |

| Forecasting role | Forecasting integrated into EMS, DSM/DSR, or microgrid operation. |

Standalone forecasting (photovoltaic - PV, wind, price) without EMS/control context. |

| Sustainability assessment | AI applied to LCA/LCC in connection with building energy management. |

LCA/LCC without AI or without EMS/building application. |

| Stage | Set 1 | Set 2 | Set 3 | Set 4 | Total | % of Previous | % of Start |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial identification (WoS + Scopus) | 511 | 175 | 360 | 1,055 | 2,101 | 100% | 100% |

| After merging (both databases, DOI, completeness) |

173 | 48 | 100 | 293 | 614 | 29.2% | 29.2% |

| After thematic filtering (EMS in buildings) | 119 | 29 | 41 | 117 | 306 | 49.8% | 14.6% |

| After content-based filtering (final set) |

29 | 23 | 1 | 106 | 159 | 52.0% | 7.6% |

| AI Method | TE (Trading, Markets) |

DEM (DSM/DSR, Control) |

Buildings (BEMS/HEMS) |

Microgrids | Energy Communities |

Closed Ecological Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Classical ML (SVM, RF, K-Nearest Neighbors - kNN, Extreme Learning Machine - ELM) |

Price & demand forecasting; bidding profiles [49,92,93] |

Load prediction, Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring (NILM), anomaly detection [60,94,95,96,97] | Energy Use Intensity (EUI) benchmarking, HVAC classification [48,93,95,97] |

DER pattern recognition, energy quantification methods [60,93] | Local demand/supply modeling [50,53] | Resource forecasting and pattern recognition for life-support loops [1,55] |

|

Deep Learning (LSTM, GRU, CNN, Regional CNN, Autoencoders) |

Short-term price signals, prosumer response [98,99,100] |

HVAC load prediction, IAQ/IEQ modeling [41,42,61,74,91] |

Occupancy detection, CO₂ prediction, drone thermal imagery [61,73,74,80] |

Recurrent EMS controllers [41,57] |

Net demand forecast, VPP integration [48,51,80] |

Prediction of environmental variables (temperature, humidity, CO₂) in greenhouses and space habitats [55,72] |

|

Reinforcement Learning (Q, DQN, A2C/A3C, PPO, DDPG, SAC) |

Transactive bidding, EV scheduling [40,46,77] |

LowEx control, EMS with storage [2,56,78,101] |

Smart HVAC dynamic control, comfort-aware policies [61] |

Adaptive EMS, ancillary services [36,77,78,90,102] |

MARL for distributed DR and pricing coordination [46,51,79] |

Adaptive control of life-support subsystems, water/air recycling optimization [55,103] |

|

Multi-Agent AI & Game Theory |

Cooperative /competitive market negotiation, fairness [39,46,79,81] |

Hierarchical DSM/DSR coordination [58,104] |

Occupant centric decision and behavior prediction [105] |

Coordination in networked microgrids, resilience enhancement [1,3,104] |

Federated MARL for transactive energy communities, blockchain-based TE [51,80,81] | Multi-agent control of food–energy–water loops in habitats [55,106] |

|

Hybrid AI (MPC+ML, Metaheuristics+ML, Surrogates) |

Surrogate MILP/MINLP for bidding optimization [3,102,107] |

RL+MPC and RL+MILP for EMS responsiveness [2,77,102] |

HEMS scheduling with LSTM+GA; DSM via BLSTM/CapsNet+HGSOA [53,91] |

ANN/GP surrogates for ESS and multi-energy scheduling [3,58,102] |

Consensus + FL for distributed optimization [51,58] | MPC+RL for CES climate /energy management [72,75] |

|

Federated & Edge AI |

FL-assisted distributed trading and coordination [51,58,100] |

Edge-AI for real-time EMS [41,54] | Adaptive FL for building forecasting; privacy-by-design automation [80,83] |

Edge-enabled EMS with IoT integration [51,54] | FL-assisted aggregation and consensus building [51,58,80] |

Edge/federated AI to preserve privacy and autonomy in CES habitats [75,82] |

|

Digital Twins & Blockchain Integration |

DT-enabled TE forecasting, auditing, blockchain-secured trades [81,82] |

DT+AI for EMS and predictive resilience [2,62,76] | BIM/IoT+DT for performance gap reduction [62,75,76] | DT /Blockchain /Building Management System (BMS) for microgrids [82,108] | DT frameworks for resilience in NMGs and TECs [1,58] |

DTs of bioregenerative CES habitats [64,72,75] |

|

Physics-Informed & Interpretable ML (PIML, Explainable AI - XAI) |

Trust metrics, explainable bidding and optimization [64] |

PIML for EMS stability and reliability [64] |

Bayesian calibration, explainability in building energy management DTs [62,76] |

XAI-based anomaly detection and IDS in MGs [2,86] |

Explainability in federated trading optimization [9,76] |

PIML/XAI for lifecycle resilience in CES habitats [64,83] |

|

Cybersecurity & Risk Aware AI |

Blockchain-secured TE markets and EV transactive flows [2,40,81] |

IDS with ML frameworks for EMS; homomorphic encryption for anomaly detection [2,52,84,85,86] |

Risk-aware ML in building automation [83,89] |

FMEA 2.0 for MG risk assessment; operator cyber-range training [87,88,89] |

Cybersecurity in federated TE and IoT environments [51,85,87,88] |

Predictive anomaly detection and ML-based maintenance in CES loops [64,82] |

| Area | Observed Focus in Literature | Identified Gap / Challenge | Future Direction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transactive Energy (TE) | Short-term market clearing (minutes–day-ahead), MARL-based bidding, bilevel fairness models |

Weak coupling with grid reliability, seasonal variability, and long-term investment decisions; resilience under cyber-physical uncertainty underexplored [39,40,52] |

Extend TE frameworks with multi-horizon optimization, AI-enhanced resilience metrics, and integration of environmental objectives |

| Dynamic Energy Management (DEM) | RL-based demand response, hybrid MPC for HVAC and microgrids, edge-AI forecasts |

Scalability and sample efficiency of RL not solved; safe deployment in heterogeneous real-world systems largely missing; interoperability with legacy BMS limited [56,57,58,61,62] |

Development of standardized DEM platforms combining robust RL/MPC hybrids with edge computing and safe RL formulations |

| AI Methodologies | Strong innovation in RL, DL, federated/edge AI, emerging DT applications |

Fragmentation across methods; limited explainability and trust; lack of integration into layered, interoperable frameworks [36,41,62,64,76] |

Move towards multi-layered AI architectures that integrate perception, control, market, and sustainability with explainability by-design |

|

Life-Cycle Integration (LCA/LCC) |

Surrogate models for retrofit/BIPV, conceptual links to community energy |

Lack of dynamic, predictive LCA coupled to EMS; minimal integration with operational control; uncertainty treatment and data standardization weak [26,109,110,111,112,114,118] |

Embed predictive LCA/LCC in EMS workflows; couple AI-based control with embodied/operational impact models; improve interoperability of data and signals |

|

Cross-domain (Buildings → Microgrids → CES) |

Building EMS well studied; microgrids emerging; CES nearly absent |

Limited research on transferability across scales and domains; no holistic studies linking building-level AI with CES-like survival-critical contexts [1,55,72,75] |

Use CES as a frontier testbed to stress-test AI for resilience, closed-loop resource management, and long-horizon sustainability |

|

Cybersecurity & Privacy |

Early works on federated learning, blockchain, IDS for microgrids |

Limited robustness against adversarial attacks; weak integration of cybersecurity into control loops; privacy preserved mainly in lab-scale pilots [52,82,83,84,85] |

Advance privacy by-design AI in EMS/TE; validate adversarial robustness in pilots; integrate AI-based intrusion detection with control frameworks |

| Layer | Trends Observed in Literature | Proposed Extensions (Framework Contribution) |

|---|---|---|

|

Perception & Prediction |

Widespread use of ML/DL for short-term forecasting (loads, prices, anomalies); early adoption of edge and federated approaches; DT mostly at experimental stage |

Develop unified, scalable pipelines combining edge/federated AI and digital twins for real-time, privacy-preserving, and explainable prediction |

|

Control & Optimization |

RL and MPC-hybrids show strong potential but remain validated mainly in simulations; limited safety guarantees and poor interoperability with legacy BMS |

Advance robust RL/MPC formulations with built-in safety, interoperability standards, and deployment in real-world pilots at building and community scales |

|

Market & Coordination |

MARL, game-theoretic models, and blockchain used in conceptual or lab-scale TE studies; DEM–TE coupling still fragmented | Establish integrated control–market architectures that embed fairness, resilience, and transparency, enabling deployment in energy communities and scalable TE platforms |

|

Sustainability & Life-Cycle |

Very limited works embedding LCA/LCC into EMS; mostly conceptual or surrogate models without operational integration |

Embed predictive LCA/LCC in EMS workflows; couple AI-based control with embodied/operational impact models; improve interoperability of data and signals |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).