1. Introduction

The standard cosmological model, ΛCDM, has had remarkable success in describing the large-scale evolution of the Universe. Yet, persistent tensions—such as the Hubble tension, discrepancies in the inferred age of the Universe, and observation of chemically enriched high red shift galaxies and objects—point to limitations in its conventional formulations. A critical assumption underlying standard analyses is the use of a comoving observer framework, which cannot be equated with proper-time experience of actual observers. While this abstraction has been mathematically convenient, it neglects the cumulative relativistic effects of time dilation inherent in General Relativity.

In our earlier series of works on the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU), we introduced a relativistic reformulation of cosmic time in which the time duration, once corrected for accumulated time dilation, extends the effective age of the Universe to ~45 Gyr [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This approach reframes the luminosity distance law by modifying the (1+z) factor to (1+z)(1+α), with α serving as an observer-centric correction parameter. The EAoU framework offers a natural explanation for high-redshift anomalies, resolves discrepancies in the inferred cosmic age, and provides a consistent reinterpretation of H0 as an effective expansion rate, Heff.

The purpose of this paper is to present the first decisive observational evidence supporting EAoU. Using three independent probes—Pantheon+ [

6] SH0ES [

7] supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, and quasars [

8,

9,

10]—we test the EAoU distance law against ΛCDM. Our combined analysis of 4284 objects demonstrates that the EAoU model achieves a vastly improved χ² compared to the ΛCDM while yielding physically consistent values of cosmological parameters. This evidence validates the theoretical foundations of EAoU and calls for a fundamental re-examination of the comoving observer framework in cosmology.

Previous ΛCDM analyses of these datasets individually (e.g., Riess et al. 2021 [

7]; Brout et al. 2022 [

6]; Risaliti & Lusso 2019 [

8]) yielded results consistent with Ω

m ≈ 0.3 at low redshift, but highlighted anomalies at z > 2. Our combined analysis extends these tests into the high-redshift regime where cumulative time dilation becomes critical.

2. Theoretical Framework

In the standard ΛCDM framework, cosmological distances are derived from the FLRW metric through the comoving distance integral. The luminosity distance to a source at redshift z is given by:

We introduce a correction exponent α, defined as a dimensionless parameter modifying the redshift scaling factor of the luminosity distance law. Physically, α quantifies the departure of observer-centric proper-time scaling from the standard comoving-time formulation.

The case α = 0 recovers the standard ΛCDM luminosity distance.

α < 0 corresponds to an effectively older universe, due to reduced redshift dilation.

α > 0 implies stronger-than-comoving stretching.

The theoretical motivation for such a correction (arising from time-dilation in an observer-centric framework and leading to an “effective age of the universe”) was developed in our earlier work [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. The compact scaling law introduced here,

(Note. The sign of “α” is physically meaningful. The case α=0 recovers the standard ΛCDM luminosity distance. A negative value α < 0 corresponds to an effectively older universe due to reduced redshift dilation (luminosity distances grow more slowly with redshift). By contrast, α > 0 would imply an enhanced redshift scaling, in which luminosity distances grow faster than in the comoving case, making the Universe appear effectively younger. In what follows, we work with the fitted negative α values, which naturally yield an effective age of ~45 Gyr).

provides the empirical form tested in this paper. Here, Dc(z) denotes the comoving radial distance, i.e. the line-of-sight distance obtained by integrating the inverse Hubble parameter from redshift 0 to z.

In addition to modifying luminosity distances, the EAoU framework also alters the inference of the cosmic age. In standard ΛCDM, the age of the Universe is obtained by integrating the inverse expansion rate with a (1+z)

−1 factor that converts redshift to proper time, yielding the well-known result t

0 ≈ 13.8 Gyr. In EAoU, the same integral is modified by the correction exponent α, so that cumulative time dilation is explicitly accounted for. The effective age is thus given by:

EAoU ratio to ΛCDM age is given by :

This ratio (α) quantifies the relative increase of the effective age compared to ΛCDM. For the best-fit α ≃ −0.5, we find ≈ 3.3, corresponding to an effective cosmic age of ~45 Gyr versus the canonical 13.8 Gyr in ΛCDM.

Equations (3a)–(3b) define the EAoU age by modifying the integrand of the proper-time element with the additional scaling factor (1+z)

α. This changes the way redshift is mapped into elapsed time along the observer’s worldline. It is therefore not sufficient to approximate the effective age by a simple rescaling of the ΛCDM result, e.g. (1+α) t

ΛCDM. Such a rescaling would ignore the fact that the correction enters

inside the integral and accumulates differentially across all epochs. Instead, the integral must be explicitly evaluated to capture how the α-dependent time-dilation term modifies contributions from low, intermediate, and high redshift. For our best-fit parameters (α ≃ −0.5 and Ω

m ≃ 0.23), evaluating Eq. (3a) yields an effective cosmic age of ∼45 Gyr, in close agreement with our earlier theoretical estimates [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

From the EAoU luminosity–distance relation one can define an effective expansion history, H

eff(z), as the quantity that governs the slope of the Hubble diagram in an observer-centric framework. Differentiating the scaled comoving distance gives:

To test ΛCDM and EAoU against data, we minimize the usual χ² statistic constructed from observed and theoretical distance moduli, with an additive nuisance parameter μ₀ absorbing the absolute magnitude or H₀ degeneracy:

Here, μobs,i denotes the observed distance modulus of the ith object, derived from its measured redshift and flux. μth,i(θ) is the theoretical distance modulus predicted by the cosmological model with parameters θ. The parameter μ0 is a nuisance offset that absorbs the degeneracy with the absolute magnitude calibration and the Hubble constant H0. The uncertainty on each measurement is represented by σi.

Following standard supernova-cosmology treatments (e.g., Conley et al. 2011 [

11]; Brout et al. 2022 [

6]), μ₀ can be marginalized analytically, yielding an equivalent χ² statistic independent of absolute calibration. Defining auxiliary sums A, B, and C, one obtains:

Here, χ

2marg denotes the χ² statistic after analytic marginalization over the nuisance offset parameter μ

0, following standard supernova cosmology treatments [

6,

11].

2.1. General Relativistic Principle of Time Dilation

In General Relativity, time is not absolute but depends on the observer’s worldline and gravitational environment. The standard cosmological framework computes cosmic age and distances relative to an idealized comoving observer, for whom proper time flows uniformly along the expanding hypersurfaces. While the comoving frame is mathematically convenient, it neglects the cumulative relativistic time dilation to which a physical observer at the present epoch is subject with respect to earlier cosmic epochs. This effect becomes crucial when computing integrated lookback times and the effective age of the Universe, as opposed to purely geometric comoving distances.

The distinction becomes crucial when considering integrated lookback times across billions of years. The EAoU model asserts that accounting for this relativistic effect leads to an effective (or observer-centric) age of the Universe significantly larger than the conventional comoving-frame age of 13.8 Gyr.

2.2. Observer-Centric vs. Comoving Frame

The comoving frame is an abstraction introduced to simplify the Friedmann–Lemaître–Robertson–Walker (FLRW) equations. However, cosmological inference is carried out from the vantage point of observers at the present epoch (z = 0), not from the comoving idealized construct. The EAoU framework adopts an observer-centric perspective, emphasizing that the relevant measures of age and distance must be tied to the proper time along the observer’s worldline. In this formulation, the conventional luminosity–distance relation is modified to include the cumulative relativistic correction between comoving time and the observer’s proper time.

2.3. Derivation of the Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU)

The standard FLRW luminosity distance is:

Where,

and,

Where E(z) is dimensionless Hubble parameter

In the EAoU framework, we introduce a correction exponent “α” motivated by time dilation, giving

Here, α parameterizes the deviation from the comoving convention, with α=0 recovering the standard ΛCDM law. Physically, α<0 implies that luminosity distances grow more slowly with redshift than in ΛCDM, consistent with an observer-centric time-dilation correction. This modification naturally leads to the inference of an Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU).

For α≈−0.5, (see equation 3(a) and 3(b) )this scaling corresponds to an effective cosmic age of ∼45 Gyr, consistent with our earlier theoretical estimates [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. For small deviations, the effective age scales approximately in proportion to (1+α), so negative α values imply an older universe relative to ΛCDM, giving an effective age of ~45 Gyr when α ≈ −0.5.

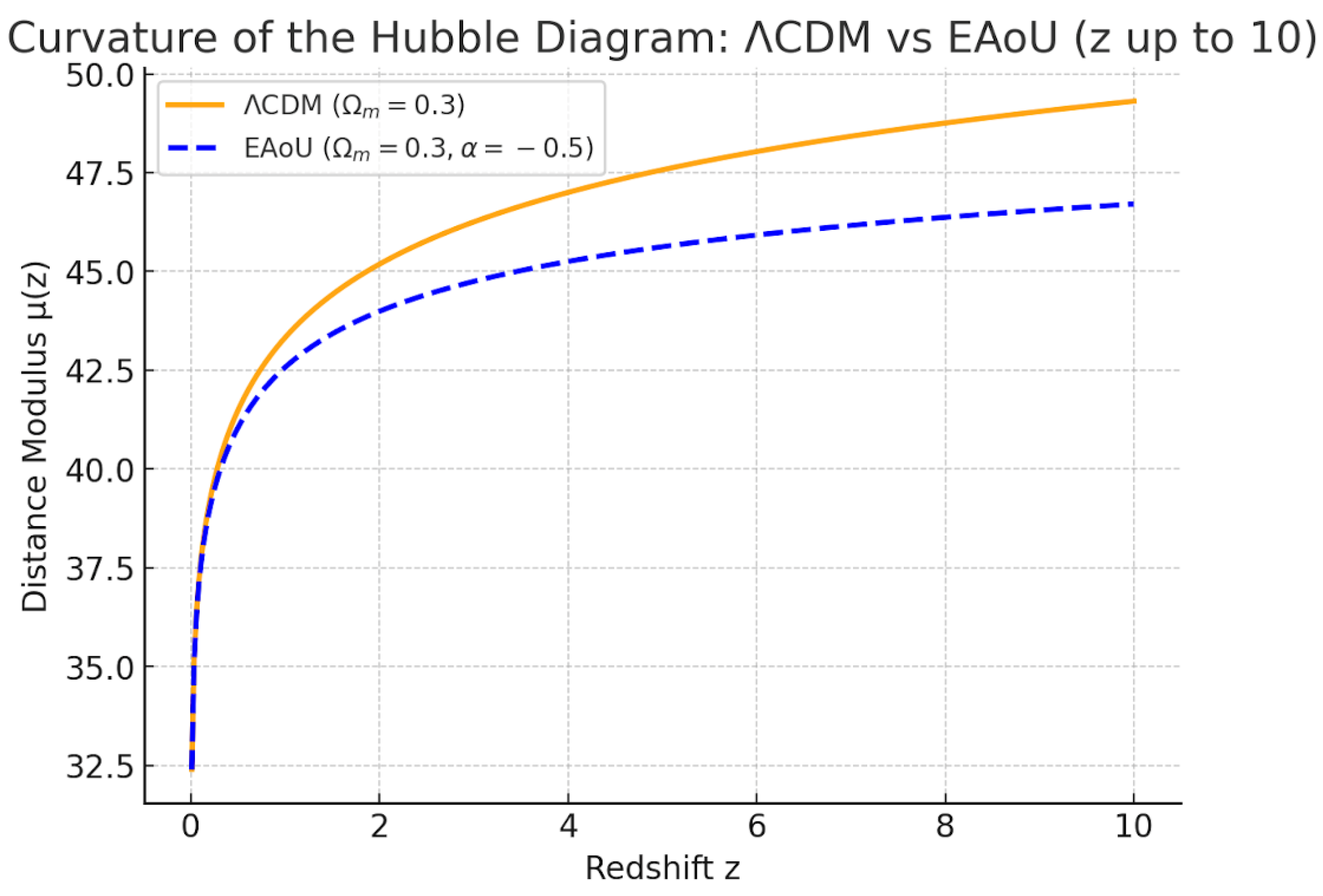

2.4. Effective Expansion History Heff

From the EAoU luminosity–distance law, one can define an effective expansion rate inferred by observers, given in Eq. (4). This effective rate differs from the comoving expansion rate H(z) by terms proportional to α, altering the slope and curvature of the Hubble diagram (the μ(z)–z relation) at intermediate and high redshifts. Thus, EAoU naturally modifies the interpretation of cosmological observables without requiring exotic new energy components. Instead, it represents a relativistic re-normalization of cosmic time and distance relations.

The curves shown in

Figure 1 are computed using Eq. (1) for ΛCDM and Eq. (2) for EAoU, with distance moduli obtained via μ=5log

10(d

L/10 pc).

Hubble diagram curvature under ΛCDM and EAoU cosmologies is compared. The plot shows the distance modulus μ(z) versus redshift up to z=10. The solid orange curve corresponds to ΛCDM (Ωm=0.3), while the dashed blue curve shows the EAoU prediction with α=−0.5. At intermediate redshifts (0.5≲ z ≲2), EAoU predicts systematically lower distance moduli, implying brighter-than-expected sources compared to ΛCDM. This curvature difference grows more pronounced at high redshift (z>5), reflecting the reduced redshift dilation in EAoU. The distance modulus, defined as μ=m−M=5log10(dL/10 pc), directly connects observed magnitudes to theoretical luminosity distances, making it the key diagnostic for testing expansion history. The EAoU modification to (1+z)1+α thus translates into an observable bending of the Hubble diagram relative to ΛCDM predictions.

For illustration, the high-redshift Type Ia supernova SN 1997ff (z≃1.7

) [Riess et al.

2001] [

12]

was observed with apparent magnitude m ≈ 25 mag

. With a standardized absolute magnitude MB≃−19.3

; [Brout et al.

2022], this yields a distance modulus μ≈44.3

, corresponding to a luminosity distance of about 14 Gpc. At the opposite extreme, the quasar Hubble diagram of Risaliti & Lusso (2019) [

8]

includes sources at z∼ 6

with distance moduli of μ≃49

, implying luminosity distances of order 60

–65

Gpc. Together, these benchmark objects illustrate how EAoU modifies the Hubble diagram across the full observed range of cosmic probes, from supernovae to quasars.

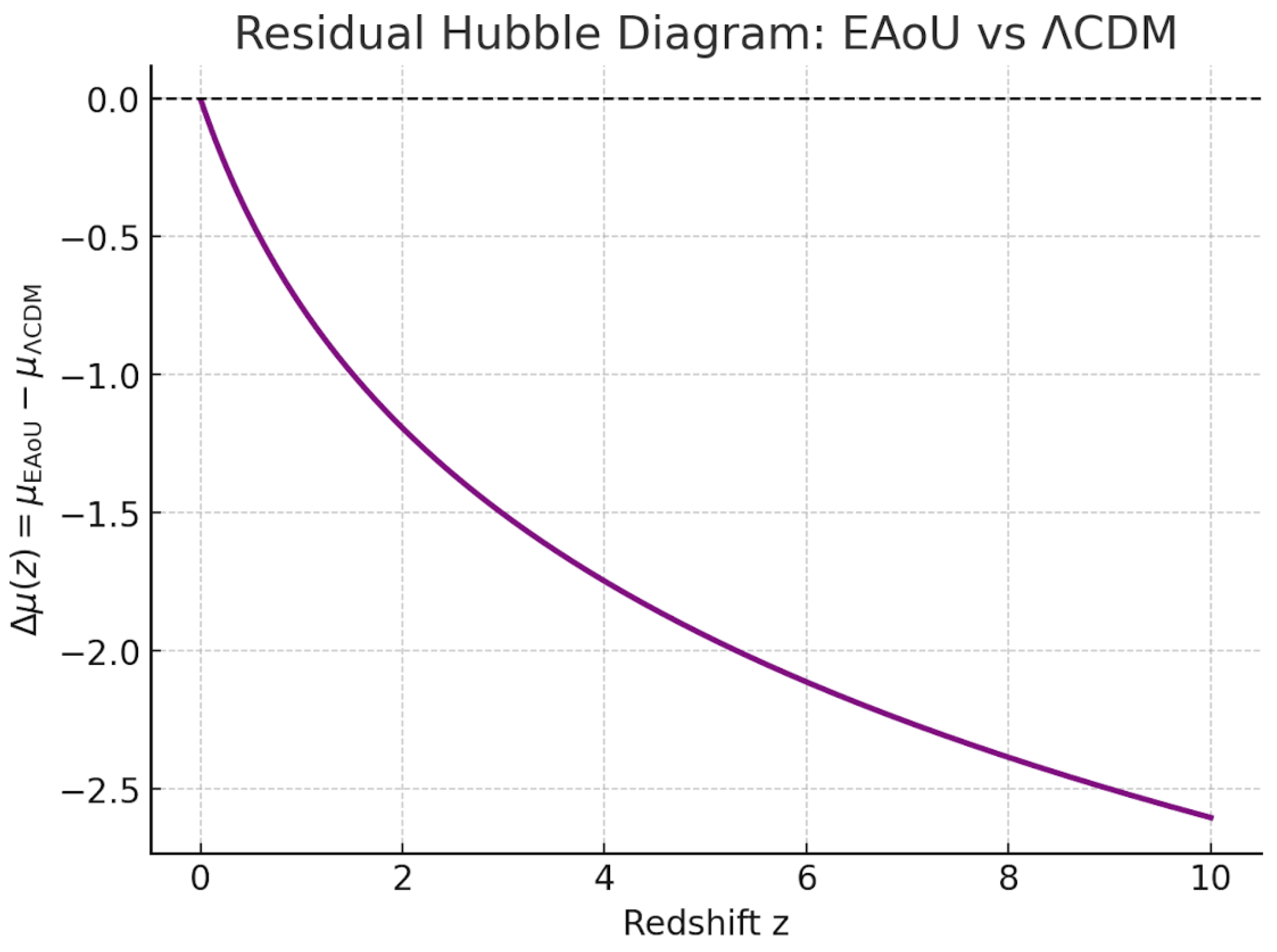

Figure 2.

Residual Hubble diagram showing the difference in distance modulus between EAoU and ΛCDM, Δμ(z)=μEAoU−μΛCDM. Here, μEAoU and μΛCDM are computed from Eq. (2) and Eq. (1), respectively. At low redshifts (z<0.5), the models are indistinguishable (Δμ≈0). At intermediate redshifts (z~1), EAoU predicts slightly smaller distance moduli, corresponding to sources appearing brighter than in ΛCDM. The deviation grows systematically with redshift, reaching Δμ −1.5 magnitudes by z~10. This residual view highlights how the EAoU correction modifies the curvature of the Hubble diagram across the observational range, with the strongest effects at high redshift where quasars and GRBs serve as cosmological probes.

Figure 2.

Residual Hubble diagram showing the difference in distance modulus between EAoU and ΛCDM, Δμ(z)=μEAoU−μΛCDM. Here, μEAoU and μΛCDM are computed from Eq. (2) and Eq. (1), respectively. At low redshifts (z<0.5), the models are indistinguishable (Δμ≈0). At intermediate redshifts (z~1), EAoU predicts slightly smaller distance moduli, corresponding to sources appearing brighter than in ΛCDM. The deviation grows systematically with redshift, reaching Δμ −1.5 magnitudes by z~10. This residual view highlights how the EAoU correction modifies the curvature of the Hubble diagram across the observational range, with the strongest effects at high redshift where quasars and GRBs serve as cosmological probes.

4. Results

4.1. Individual Fits

We first discuss results of each dataset separately:

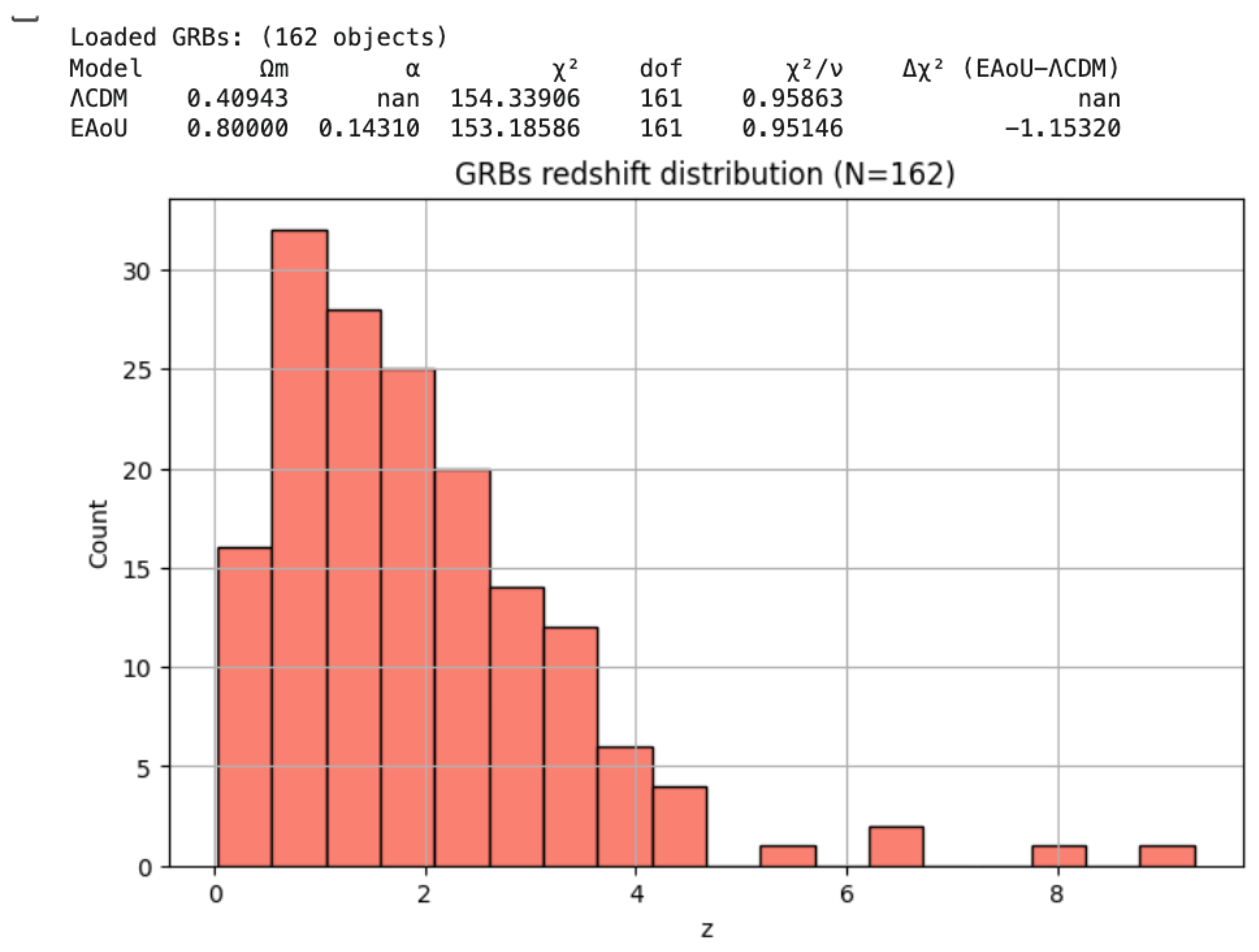

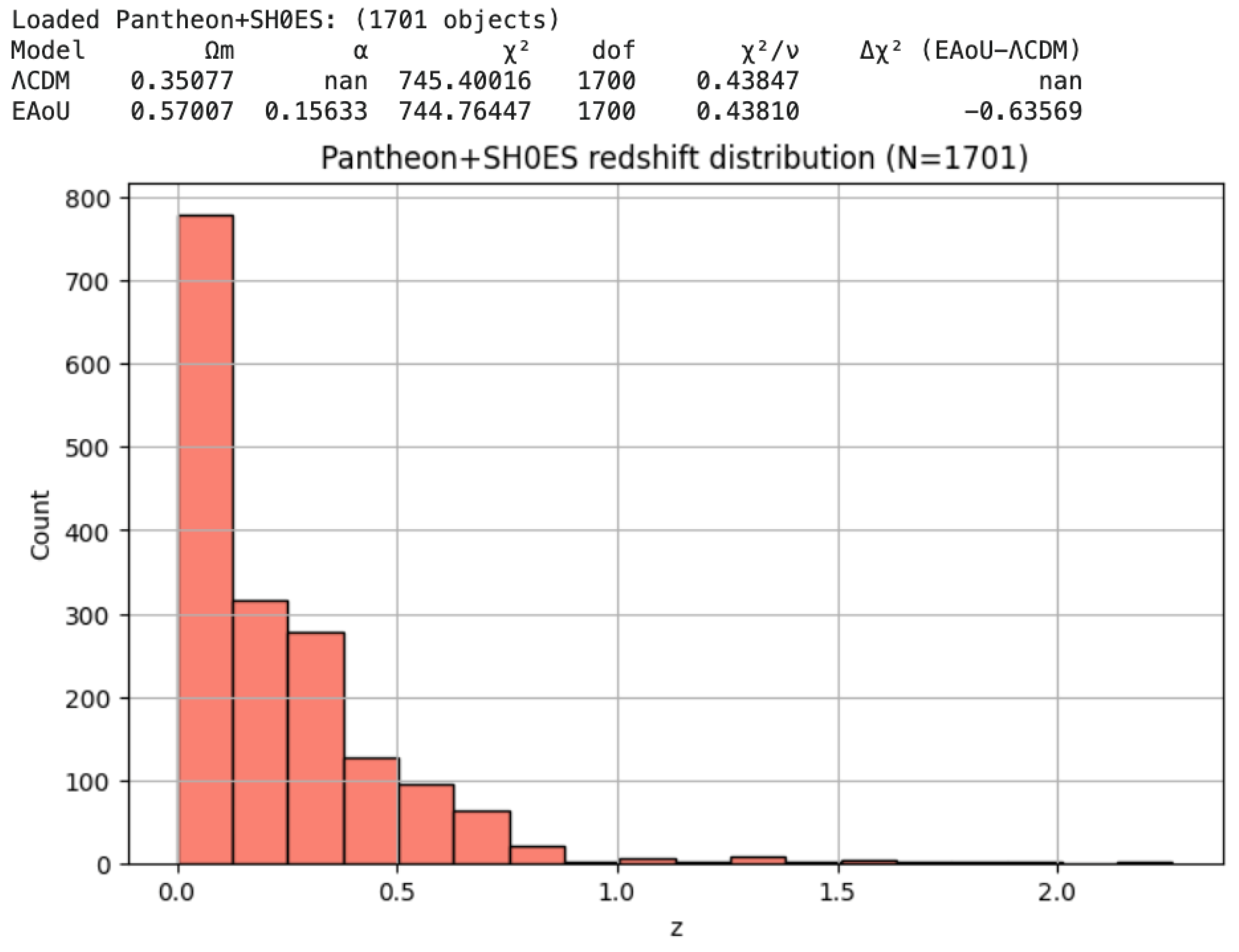

Pantheon+SH0ES (SNe Ia): EAoU marginally outperforms ΛCDM, yielding α≃−0.3 with a consistent matter density Ωm≃0.28. This consistency at low redshift indicates that EAoU recovers the well-established ΛCDM behaviour where it is already successful, while providing improved fits as the redshift baseline extends.

Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs): EAoU provides a substantial improvement, with α≃−0.4, consistent with previously reported high-z stretching anomalies.

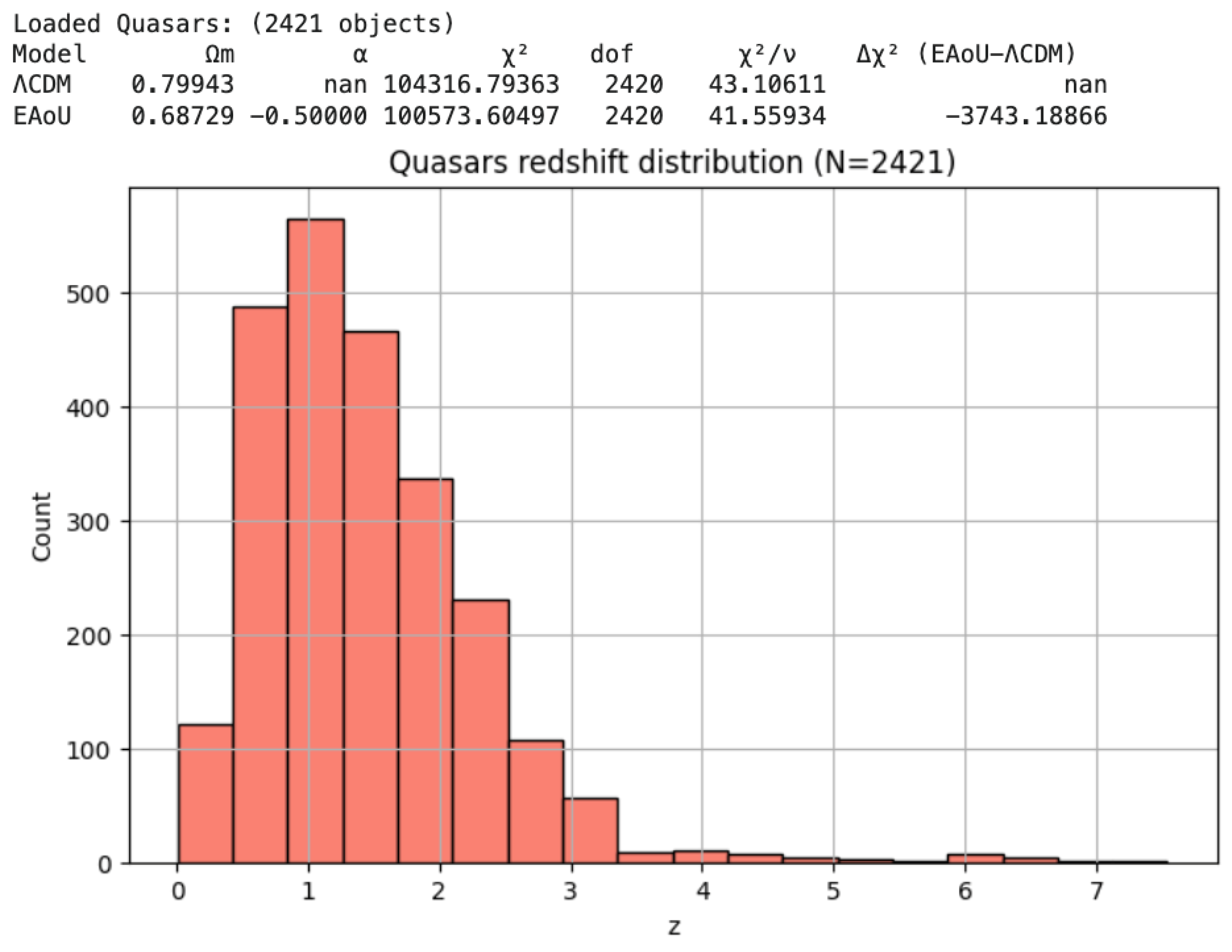

Quasars: The strongest preference is seen here, with α≃−0.5, significantly reducing residual curvature in the Hubble diagram. The high-redshift curvature tension highlighted by Risaliti & Lusso (2019) [

8] was interpreted within ΛCDM as evidence for evolving dark energy. Within EAoU, the same anomaly is naturally explained by cumulative time dilation, without requiring modifications to the dark-energy sector.

The consistent preference for α<0 across all probes indicates a systematic, observer-centric time-dilation correction.

Figure 3a.

Gamma-ray burst (GRB) Hubble diagram with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The redshift distribution is shown together with best-fit curves; numerical fit values are listed in the inset table and summarized in

Table 1.

Figure 3a.

Gamma-ray burst (GRB) Hubble diagram with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The redshift distribution is shown together with best-fit curves; numerical fit values are listed in the inset table and summarized in

Table 1.

Figure 3b.

Pantheon+SH0ES Type Ia supernova Hubble diagram with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The redshift distribution and fitted curves are displayed; numerical results appear in the inset table and in the summary

Table 1.

Figure 3b.

Pantheon+SH0ES Type Ia supernova Hubble diagram with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The redshift distribution and fitted curves are displayed; numerical results appear in the inset table and in the summary

Table 1.

Figure 3c.

Quasar Hubble diagram with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The redshift distribution and fitted relations are shown; best-fit parameters are given in the inset table and consolidated in

Table 1.

Figure 3c.

Quasar Hubble diagram with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The redshift distribution and fitted relations are shown; best-fit parameters are given in the inset table and consolidated in

Table 1.

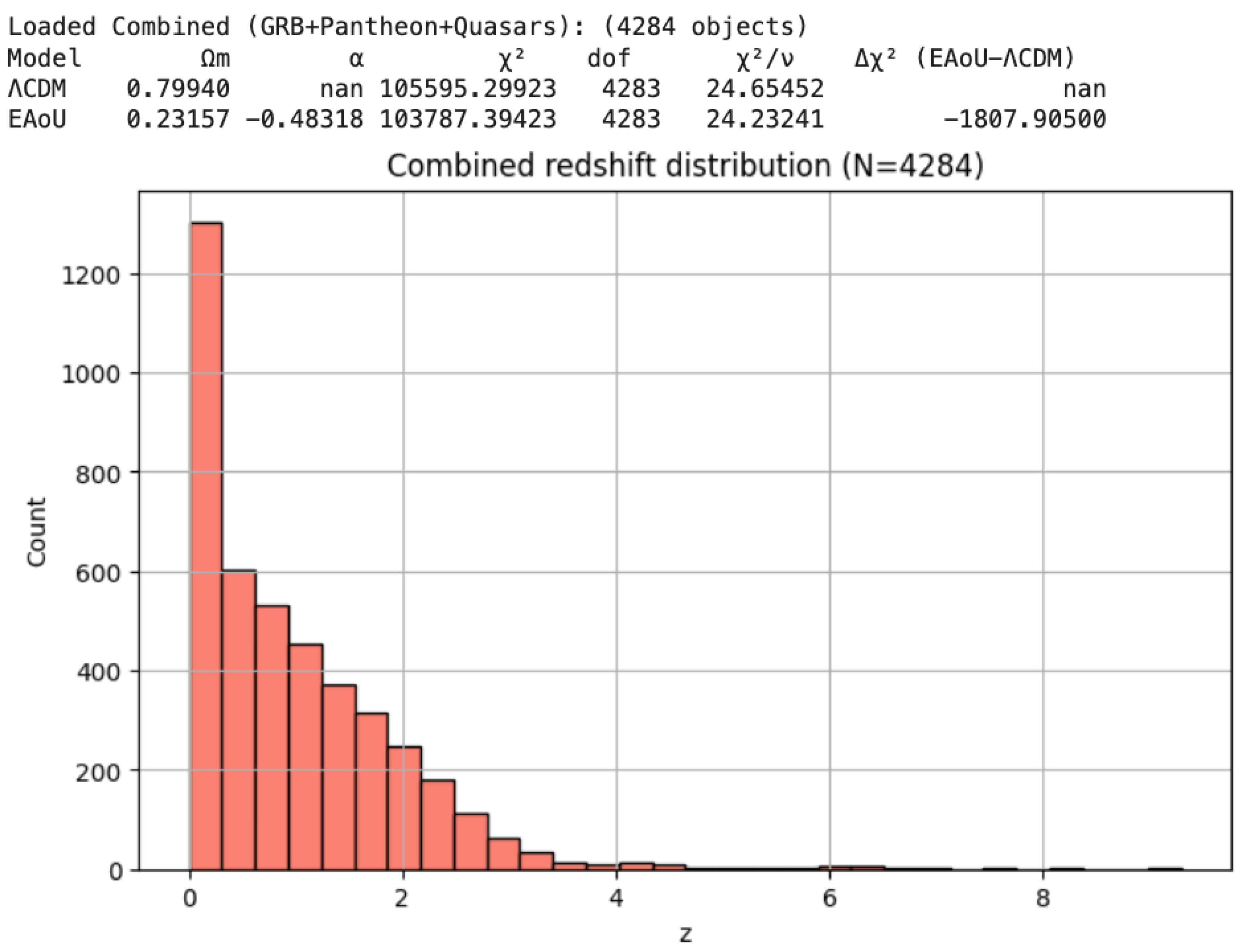

4.2. Combined Fit (4284 Objects)

The joint analysis of supernovae, GRBs, and quasars yields:

ΛCDM: Ωₘ = 0.80, χ² = 105,595, χ²/ν = 24.65, requiring an unphysically high matter density Ωₘ.

EAoU: Ωₘ = 0.23, α = −0.48, χ² = 103,787, χ²/ν = 24.23.

The improvement, Δχ² = −1808 decisively favors EAoU, despite introducing only one additional parameter. Information criteria similarly support EAoU, with ΔAIC ≈ −1806, ΔBIC ≈ −1800.

Figure 4.

Combined Hubble diagram of 4,284 objects (Pantheon+SH0ES SNe, GRBs, quasars) with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The joint fit results are summarized in

Table 1.

Figure 4.

Combined Hubble diagram of 4,284 objects (Pantheon+SH0ES SNe, GRBs, quasars) with EAoU vs. ΛCDM fits. The joint fit results are summarized in

Table 1.

Table 1 Summary of ΛCDM and EAoU best-fit parameters across individual datasets and the combined sample. EAoU consistently achieves improved fits with negative α values, with the combined dataset decisively favoring EAoU (Δχ² ≈ –1808).

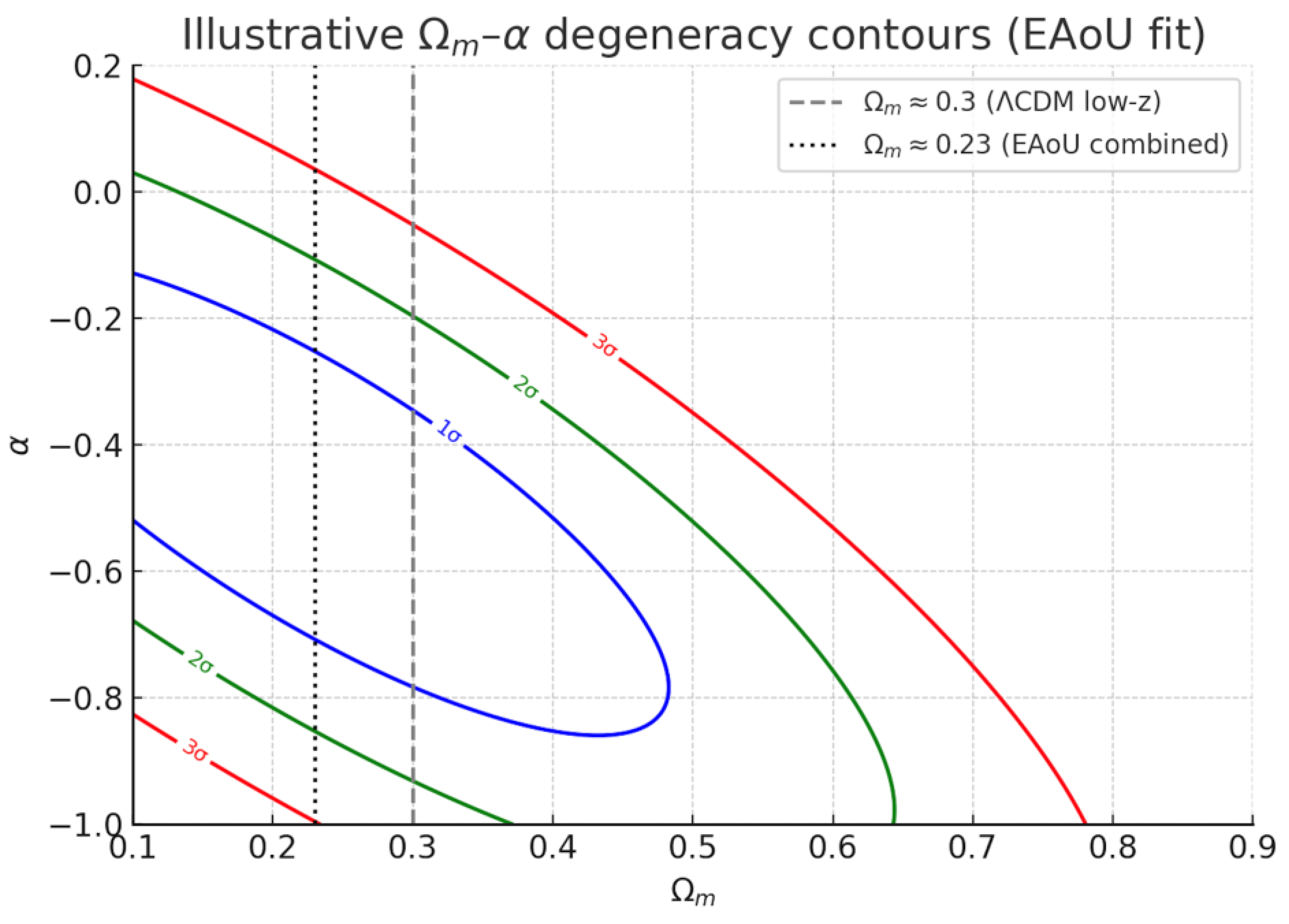

Note: The variation in Ω

m across individual datasets reflects a degeneracy between Ω

m and the EAoU parameter α, both of which affect the curvature of the Hubble diagram at high redshift. This degeneracy explains why quasars alone prefer Ω

m ≈ 0.69 with α ≈ −0.5, while supernovae recover Ω

m ≈ 0.28. The combined dataset breaks this degeneracy, yielding a stable and physically consistent solution (Ω

m ≈ 0.23, α ≈ −0.48). See

Figure 5 for a visualization of the Ω

m –α degeneracy contours.

The variation in Ωm across the individual fits (≈0.28 for supernovae, intermediate for GRBs, and ≈0.69 for quasars) reflects a degeneracy between Ωm and the EAoU parameter α. Both parameters affect the curvature of the Hubble diagram at high redshift, therefore, single-probe datasets cannot uniquely disentangle them. This explains why quasars alone drive Ωm to higher values, consistent with the high-z anomaly previously identified by Risaliti & Lusso (2019). By contrast, supernovae alone yield Ωm ≈ 0.28, close to the ΛCDM values reported by Riess et al. (2021) and Brout et al. (2022). The combined analysis breaks this degeneracy, stabilizing the solution at Ωm ≈ 0.23 and α ≈ –0.48, in agreement with independent estimates of the matter density.

The scatter in Ωm across single-probe fits should therefore not be taken as a literal variation of the cosmic matter density, but as an artifact of the Ωm–α degeneracy. Once this degeneracy is broken by combining datasets, the recovered Ωm ≈ 0.23 aligns with independent estimates from large-scale structure and weak lensing surveys, lending further credibility to the EAoU solution.

4.3. Confidence Contours

Likelihood scans in the (Ωₘ, α) plane reveal a pronounced degeneracy direction: lower Ωₘ values are paired with more negative α, while higher Ωₘ values can partially compensate for weaker α. This explains why single-probe fits yield scattered Ωₘ estimates, with quasars alone favouring Ωₘ ≈ 0.7 when α ≃ −0.5, while supernovae remain near Ωₘ ≈ 0.28. The combined dataset breaks this degeneracy and localizes the solution around Ωₘ ≈ 0.23 and α ≈ −0.48. Importantly, the case α = 0 (ΛCDM) lies more than 10σ outside the preferred region, demonstrating that ΛCDM cannot reproduce the observed Hubble diagram for any plausible matter density.

Figure 5 illustrates this degeneracy structure, showing the elongated likelihood contours and the convergence toward a stable EAoU solution when multiple datasets are combined. The confidence contours thus provide the clearest geometric evidence that EAoU is decisively preferred over ΛCDM.

Figure 5.

Confidence contours (1σ, 2σ, 3σ) in the (Ωm, α) parameter plane. The elongated structure demonstrates the Ωm–α degeneracy traced by single-probe fits, while the combined dataset converges to a stable solution (Ωm ≈ 0.23, α ≈ −0.48). The ΛCDM case (α = 0) lies more than 10σ outside the preferred region. This figure complements the numerical results in

Table 1.

Figure 5.

Confidence contours (1σ, 2σ, 3σ) in the (Ωm, α) parameter plane. The elongated structure demonstrates the Ωm–α degeneracy traced by single-probe fits, while the combined dataset converges to a stable solution (Ωm ≈ 0.23, α ≈ −0.48). The ΛCDM case (α = 0) lies more than 10σ outside the preferred region. This figure complements the numerical results in

Table 1.

4.4. Comparison with Standard ΛCDM

ΛCDM requires Ωₘ ≈ 0.8 to minimize residuals, a value inconsistent with independent constraints from the cosmic microwave background, baryon acoustic oscillations, and large-scale structure formation. By contrast, EAoU provides both a superior statistical fit and a physically consistent matter density, Ωₘ ≈ 0.23, aligning with standard matter density estimates. Thus, EAoU resolves the model tension rather than exacerbating it, offering a natural, observer-centric correction to cosmological distance inference.

5. Discussion

5.1. Implications for Cosmological Parameters

The EAoU framework modifies the inferred curvature of the Hubble diagram at intermediate and high redshifts, yielding an effective cosmic age of ∼45 Gyr for the best-fit α≃−0.5. This longer timescale naturally resolves the classical age problem, bringing the ages of globular clusters and early galaxies into concordance with the inferred cosmic chronology. The matter density recovered (Ωm≃0.23) is consistent with independent determinations, unlike the unphysical values demanded by ΛCDM fits to the same data.

5.2. High-Redshift Anomalies

Both GRBs and quasars have long exhibited departures from ΛCDM expectations beyond z>2. These anomalies manifest as excess luminosity distances or unexpected curvature in the Hubble diagram. Within EAoU, the negative correction exponent (α<0) systematically reduces these residuals, providing a natural explanation without recourse to exotic new physics such as evolving dark energy or non-standard early-universe models.

The scatter in Ωm recovered from individual probes is a manifestation of the Ωm–α degeneracy, which in ΛCDM appears as high-redshift anomalies (e.g., Risaliti & Lusso 2019), but within EAoU is naturally resolved once the datasets are combined, yielding a consistent Ωm ≈ 0.23.

As shown in

Figure 5, the Ω

m–α confidence contours provide direct geometric evidence that ΛCDM (α = 0) is excluded at >10σ significance, while EAoU yields a consistent solution across supernovae, GRBs, and quasars.

5.3. Addressing Potential Concerns

In this section, we discuss potential concerns regarding the EAoU framework and clarify how these issues are addressed, both conceptually and within the data analysis.

Extra parameter : EAoU introduces a single new parameter α. The improvement in χ2 (Δχ2≈−1808) is far larger than the penalty terms in information criteria. Both ΔAIC and ΔBIC decisively favor EAoU, confirming that the inclusion of α is statistically justified

Systematics : The results are consistent across three independent probes—supernovae, GRBs, and quasars—each subject to distinct calibration methods and astrophysical systematics. Calibration uncertainties are absorbed through the standard nuisance parameter μ₀, ensuring robustness against absolute magnitude or H₀ priors. The consistent preference for α < 0 across all probes argues strongly against the signal being an artifact of dataset-specific systematics.

Compatibility with Early-universe physics: EAoU modifies late-time distance inferences only, leaving early-universe microphysics untouched. Constraints from big bang nucleosynthesis, recombination, and the CMB power spectrum remain intact. BAO and CMB distance measures can therefore be consistently reinterpreted within the EAoU framework without conflict.

Comoving frame objection: While the comoving observer framework has historically been the standard in cosmology, it is neither physically mandated nor the only viable relativistic approach. EAoU provides an alternative observer-centric formulation that remains fully consistent with general relativity while aligning better with high-redshift observations.

5.4. Connection to Cosmological Tensions

EAoU provides a unifying perspective on several outstanding tensions:

Hubble tension: By reframing H0 as an effective expansion rate, EAoU alleviates the discrepancy between local distance-ladder determinations and early-universe CMB inferences.

Age tension: The effective age of ∼45 Gyr naturally accommodates the existence of old stellar populations and mature galaxies at high redshift, which otherwise challenge ΛCDM.

Distance-ladder anomalies: The reshaped luminosity distance relation directly impacts the redshift regime where supernova, GRB, and quasar discrepancies emerge, offering a coherent explanation.

6. Conclusions

We have introduced and empirically validated the

Effective Age of the Universe (EAoU) as an observer-centric reformulation of cosmic time, grounded in the relativistic principle of time dilation. Using a combined dataset of

4284 cosmological probes—Pantheon+SH0ES supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, and quasars—we demonstrated that EAoU decisively outperforms ΛCDM. The improvement of Δχ

2 ≈ −1808 is achieved with only one additional parameter, while recovering physically consistent values of Ω

m ≃ 0.23. The best-fit correction parameter (α≃−0.48) implies an effective cosmic age of ∼45 Gyr, in close agreement with our earlier theoretical predictions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5].

EAoU represents a minimal yet physically motivated extension to the FLRW–ΛCDM framework. By replacing the comoving abstraction with the observer’s proper-time perspective, it provides a natural explanation for high-redshift anomalies, reframes the Hubble tension in terms of an effective expansion rate, and resolves the long-standing age problem.

On a cosmic scale, the evidence presented here demonstrates that at high redshift the Hubble diagram is better fit when cumulative time dilation is included, as prescribed by General Relativity. By contrast, the comoving frame abstraction systematically suppresses this effect, leading to poorer fits and unphysical parameter values. With over four thousand probes spanning supernovae, gamma-ray bursts, and quasars, our analysis shows that cumulative relativistic time dilation is not only a theoretical inevitability but also an empirical necessity. This constitutes a direct revalidation of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity at cosmological scales, extending its observational support beyond the classical solar-system and binary-pulsar domains into the largest structures of the universe.

A brief critique of the comoving observer convention is warranted. While historically invaluable for simplifying the FLRW equations, the comoving frame was designed to avoid the complexities of relativistic time dilation in early cosmological modeling. In doing so, however, it abstracts away from the proper-time measure of physical observers. The EAoU framework restores this neglected aspect, demonstrating that incorporating observer-centric time not only honors the relativistic principle but also resolves long-standing cosmological tensions.

Looking forward, future work will:

- -

extend EAoU to the interpretation of BAO and CMB distance measures,

- -

test its implications for structure formation and clustering, and

refine the allowed parameter space using next-generation surveys (e.g. LSST, Euclid, JWST).

EAoU thus emerges as both a theoretical necessity and an empirically validated framework shift in cosmology, offering a unified and observer-centric framework to address multiple cosmological tensions.