1. Introduction

Stroke remains a critical global health challenge, ranking as the second leading cause of death and the third leading cause of combined death and disability worldwide [

1]. The global burden of stroke continues to increase, with rises in incidence, mortality, and overall prevalence [

2].

Post-stroke impairments, particularly motor deficits such as hemiparesis, commonly limit mobility and self-care abilities, substantially impacting functional independence and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [

3]. Engagement in structured rehabilitation is essential for recovery; however, many stroke survivors face barriers to consistent participation due to physical and cognitive impairments [

4,

5] as well as psychological constraints [

6].

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly accelerated the integration of digital health technologies, reshaping care delivery across medical disciplines. Telemedicine, in particular, emerged as an effective alternative for maintaining continuity of care when in-person services were limited. Recent studies underscore both the opportunities and limitations of this transition, highlighting issues such as digital disparities and inconsistent policy implementation [

7,

8]. Telerehabilitation, the delivery of rehabilitation services via telecommunication platforms, has gained attention as a feasible approach that can be deployed in place of conventional outpatient therapy [

9].

Following discharge from acute or inpatient settings, many stroke patients experience a decline in functional capacity as supervised rehabilitation is reduced or discontinued [

10]. Sustained participation in task-specific exercise is critical to preserving motor coordination, balance, and gait function, yet access to facility-based programs often diminishes in the community phase. Limited access to supervised rehabilitation has been associated with decreased lower limb strength, postural instability, and increased fall risk [

11]. In response, growing evidence supports the utility of home-based exercise interventions. Structured home-based programs can effectively improve mobility and functional performance in individuals with stroke [

12], and sustained physical activity contributes to neuroplasticity and long-term motor recovery [

13]. Importantly, comparable outcomes have been reported between home-based telerehabilitation and traditional outpatient therapy, reinforcing the therapeutic equivalence of well-designed remote interventions [

14].

While telerehabilitation adoption has progressed rapidly in some countries, such as the United States, where supportive policy and infrastructure facilitated clinical implementation [

15], its integration in South Korea has been slower. Despite high digital readiness, utilization remains limited due to regulatory restrictions and fragmented application across providers, particularly among physical therapists [

16]. This highlights the need for standardized frameworks that support the structured and sustained delivery of telerehabilitation services.

Although individual-based telerehabilitation models have been widely examined, limited research has addressed the potential benefits of group-based telerehabilitation for stroke survivors. Group exercise formats may offer not only physical benefits but also psychosocial and motivational support. However, the efficacy of this approach when delivered remotely remains insufficiently investigated. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the effects of group-based telerehabilitation on physical function, depressive symptoms, and HRQoL in community-dwelling stroke survivors. Additionally, this study examines whether post-intervention changes in lower limb strength, balance, mobility, and fall efficacy are predictive of HRQoL. We hypothesize that greater functional improvements will be associated with higher levels of post-intervention HRQoL.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design Overview

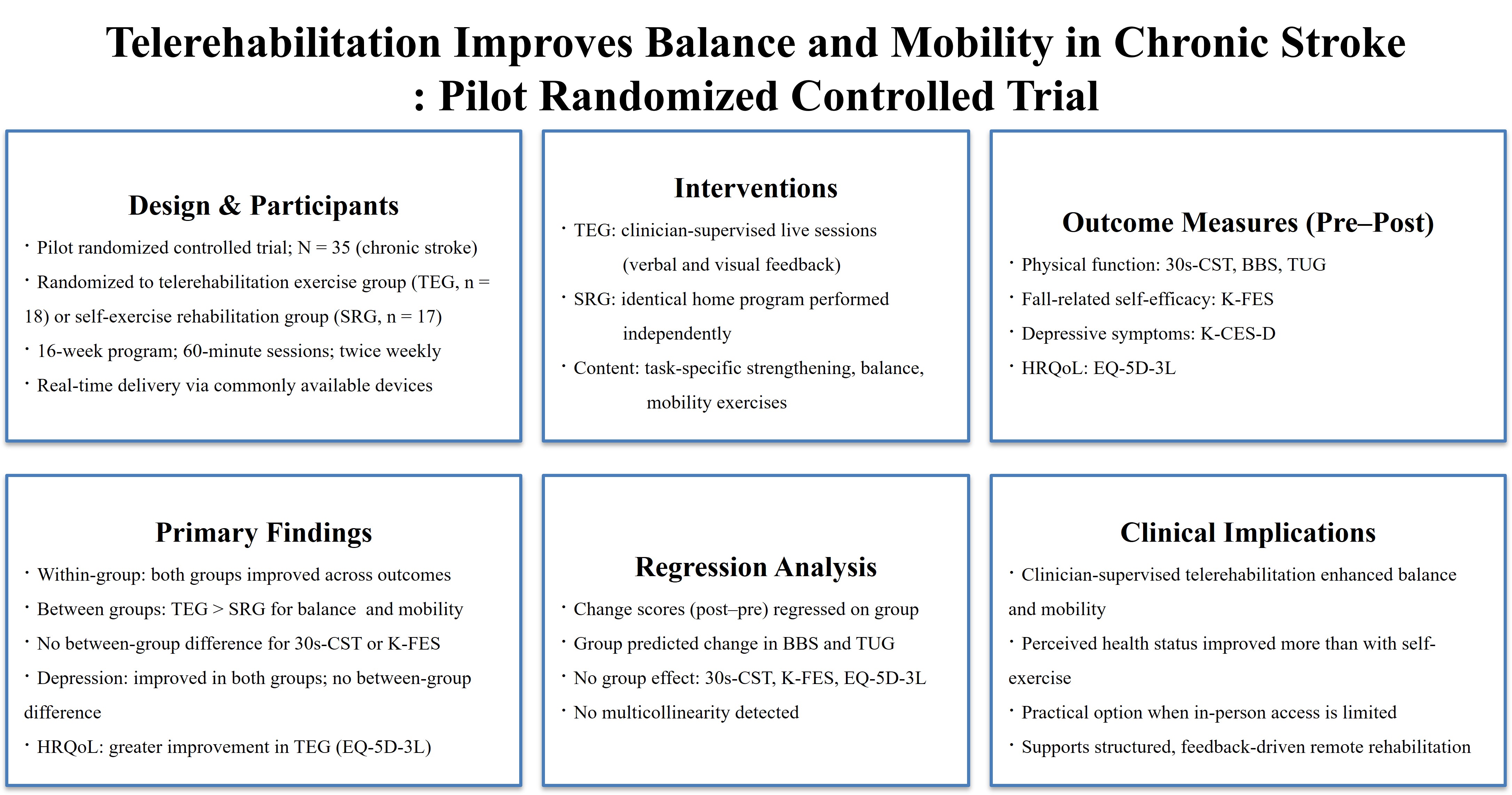

This pilot randomized controlled trial was conducted among community-dwelling stroke survivors, who were randomly assigned to either the telerehabilitation exercise group (TEG) or the self-exercise rehabilitation group (SRG). Baseline assessments were performed to evaluate participants’ general characteristics (

Table 1), physical function, depressive symptoms, and HRQoL. Following a 16-week intervention, post-assessments were conducted to analyze within- and between-group differences. Additionally, linear regression analyses were used to determine whether changes in physical function predicted post-intervention HRQoL outcomes.

2.2. Participants and Randomization

Participants were recruited from the rehabilitation exercise center of a public health subcenter in District S, Seoul, South Korea, via offline bulletin board postings. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) physician-confirmed diagnosis of stroke ≥12 months prior; (2) stable vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, temperature); (3) ability to ambulate independently for at least 15 meters with or without assistive devices; and (4) a score ≥24 on the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination. Exclusion criteria included: (1) significant musculoskeletal disorders; (2) cardiovascular or metabolic diseases; (3) use of muscle relaxants; (4) history of moderate to severe trauma; and (5) visual or auditory impairments.

Sample size estimation was performed using G*Power version 3.1.9.7 (Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany). Based on anticipated between-group differences from prior work, an effect size (Cohen’s d) of approximately 0.9 was used [

17]. Assuming a two-tailed independent t-test, with a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a statistical power (1–β) of 0.80, a minimum of 19 participants per group was required. However, due to recruitment limitations, 35 participants were ultimately enrolled and randomly assigned to the TEG (n = 18) and SRG (n = 17) using a computer-generated randomization sequence. Group assignment was conducted by an independent researcher who was not involved in the intervention or outcome assessments to ensure allocation concealment.

All participants were fully informed of the study’s purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangwon National University (KWNUIRB-2024-04-008-001).

2.3. Intervention

Participants assigned to the TEG completed the intervention from their homes via scheduled online sessions using either a personal computer or smartphone equipped with the Google Meet application. Each participant connected at a scheduled time, predetermined by the therapist. The sessions were conducted in real time by a licensed physical therapist located at the rehabilitation therapy room of the public health center.

Prior to each session, the therapist sent a session link via text message, enabling participants to join the session through their devices. During each session, the therapist provided verbal instructions and visual demonstrations, offering real-time feedback to ensure proper execution, safety, and participant engagement.

Participants in the SRG received an identical exercise program, delivered in printed or digital format. They were instructed to perform the exercises independently at home, without direct therapist supervision. To ensure safety, a caregiver or family member was required to be present during all sessions in both groups. Upon completion of each session, participants in the SRG submitted a self-reported confirmation form during their scheduled follow-up visits to the rehabilitation center. Both groups completed 60-minute sessions twice weekly over a 16-week period. The detailed components of the intervention are summarized in

Appendix A.

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.4.1. Physical Function

Lower limb strength and endurance were assessed using the 30-Second Chair Stand Test (30s-CST). Participants were instructed to repeatedly transition from a seated to a standing position without using arm support for 30 seconds. The number of properly executed repetitions was recorded. The 30s-CST is widely used in geriatric and neurologically impaired populations due to its simplicity, minimal equipment requirements, and suitability for both clinical and home settings. It demonstrates high test–retest reliability, with intraclass correlation coefficient (ICCs) reported 0.84 and 0.92 [

18].

Balance was evaluated using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), which consists of 14 tasks assessing both static and dynamic balance. Each item is scored on a 5-point scale (0-4), with a maximum score of 56, where higher scores indicate better balance performance and lower fall risk. The BBS is widely used in stroke rehabilitation due to its clinical applicability and sensitivity to change. It has demonstrated excellent intra- and inter-rater reliability in stroke patients, with ICCs of 0.99 and 0.98, respectively [

19].

Functional mobility was assessed via the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test. Participants were instructed to rise from a chair, walk 3 meters, turn, return, and sit down. The time required to complete the sequence was recorded, with shorter times indicating greater mobility. The TUG is a reliable and time-efficient indicator of dynamic balance and gait capacity. It is particularly suitable for stroke patients and demonstrates excellent test–retest reliability (ICC = 0.95 - 0.99) along with strong concurrent validity [

20].

2.4.2. Fall-Related Self-Efficacy

Fall-related self-efficacy was measured using the Korean version of the Falls Efficacy Scale (K-FES), a 10-item questionnaire rated on a 10-point Likert scale. Total scores range from 10 to 100, with higher scores reflecting greater confidence in performing daily activities without falling. The K-FES has shown high internal consistency and significant associations with physical function and balance, supporting its construct validity in stroke and older adults [

21].

2.4.3. Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Korean version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (K-CES-D), a validated 20-item self-report measure designed to evaluate the frequency of depressive symptoms over the preceding week. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 – 3), with total scores ranging from 0 to 60. Higher scores indicate greater severity of depressive symptoms. The K-CES-D has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, and shows significant correlations with other psychological measures, supporting its construct validity in clinical settings [

22].

2.4.4. Health-Related Quality of Life

HRQoL was evaluated using the Korean version of the EuroQol Five-Dimension Three-Level descriptive system (EQ-5D-3L), a standardized, preference-based measure comprising five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression. Each item is rated on a three-level scale, and responses are converted into an index score using the Korean valuation set. Higher scores indicate better perceived health status.

The EQ-5D-3L has demonstrated adequate validity and sensitivity to clinical change in patients with stroke. A previous cohort study confirmed that the EQ-5D-3L was sensitive to changes over time in stroke-related recovery, supporting its applicability for assessing HRQoL in clinical rehabilitation settings [

23]. It also exhibited good convergent validity with stroke-specific measures such as the modified Rankin Scale and Barthel Index [

24], supporting its suitability for assessing HRQoL in stroke.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 29.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the general characteristics of participants. The Shapiro-Wilk test confirmed normal distribution for all continuous variables.

Baseline homogeneity between the TEG and the SRG was evaluated using independent t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. Paired t-tests were conducted to examine within-group differences pre- and post-intervention, while independent t-tests were used to compare between-group differences in outcome measures, including 30s-CST, BBS, TUG, K-FES, K-CES-D, and EQ-5D-3L.

To examine the effect of group assignment on changes in outcomes, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted using the enter method. Change scores (post–pre) served as dependent variables, with group included as the independent variable. Variance inflation factors were examined to assess multicollinearity. A significance level of p < 0.05 was applied for all analyses.

3. Results

A total of 35 participants completed the study, with 18 assigned to the TEG and 17 to the SRG. Baseline characteristics, including age, sex distribution, affected side, height, weight, BMI, and duration since stroke onset, did not differ significantly between groups (

Table 1).

Following the 16-week intervention, both groups demonstrated significant within-group improvements in physical function. As shown in

Table 2, the TEG showed greater improvement in BBS (p = 0.010) and TUG (p = 0.020) compared to the SRG. Both groups showed improvements in 30s-CST and K-FES; however, between-group differences were not statistically significant.

Both groups exhibited significant reductions in K-CES-D; between-group differences were not significant (

Table 3). In contrast, the TEG showed a significantly greater increase in EQ-5D-3L index scores compared to the SRG (p = 0.035), indicating a more pronounced improvement in HRQoL.

To further examine the influence of group allocation on treatment effects, multiple linear regression analyses were conducted using post-pre change scores as dependent variables. According to the findings in

Table 4, assignment to the TEG significantly predicted greater improvement in BBS (p < 0.05, R

2 = 0.152) and TUG (p < 0.05, R

2 = 0.153). No significant group effects were found for 30s-CST or K-FES. No multicollinearity was detected.

4. Discussion

This study examined the effects of telerehabilitation on physical function, depressive symptoms, and HRQoL in individuals with chronic stroke. Both the TEG and SRG showed significant within-group improvements across all outcomes following the 16-week intervention. However, between-group comparisons revealed greater improvements in balance, mobility, and HRQoL in the TEG. Regression analyses further identified group allocation as a significant predictor of changes in balance and mobility, suggesting the superiority of therapist-supervised telerehabilitation over self-directed exercise. These findings support clinician-supervised telerehabilitation as an effective and feasible rehabilitation strategy.

Telerehabilitation is considered a practical approach to improve access to rehabilitation for stroke patients with limited availability of facility-based services. A recent qualitative investigation reported that patients, caregivers, and clinicians recognized the clinical value of remotely delivered interventions as part of structured rehabilitation [

25]. However, successful implementation requires addressing context-specific barriers such as limited digital infrastructure, caregiver burden, and the need for professional training in remote delivery models [

26]. The present study further supports the feasibility of telerehabilitation, indicating that a structured exercise program can be effectively delivered using commonly available mobile platforms without usability limitations.

Previous studies have consistently demonstrated that exercise-based rehabilitation plays a critical role in improving physical function among stroke survivors [

27,

28]. A structured home-based exercise program significantly enhanced lower limb strength and gait ability in individuals with chronic stroke, emphasizing the importance of continuous physical exercise beyond inpatient care [

9]. In the present study, both the TEG and SRG exhibited significant improvements in the physical function following a 16-week intervention, indicating enhanced lower limb strength and mobility within both groups. These results reinforce the clinical value of incorporating structured lower limb strengthening and mobility exercises to improve functional outcomes in patients with chronic stroke.

The TEG demonstrated a greater improvement in balance compared to the SRG. This result is consistent with prior study suggesting that remote interventions incorporating real-time therapist supervision can offer superior outcomes compared to self-directed exercise programs [

29]. In addition, the way exercises are performed and the quality of external feedback play a critical role in functional recovery [

30]. In this study, the TEG, which received professional feedback, demonstrated greater improvements in both BBS and TUG compared to the SRG, further supporting the effectiveness of expert-led telerehabilitation. This suggests that real-time verbal and visual feedback from clinicians may reinforce correct movement and increase adherence, both of which are critical for balance recovery.

Both the TEG and SRG exhibited significant within-group reductions in depressive symptoms, however, the between-group difference in improvement was not statistically significant, suggesting that structured exercise, whether supervised or self-directed, may effectively reduce post-stroke depressive symptoms. A multicenter trial comparing home-based telerehabilitation with home exercise alone in stroke patients similarly found significant improvements in depression scores in both groups, with no significant between-group difference, highlighting the therapeutic benefit of consistent physical activity [

31].

Regarding HRQoL, the present study found that only the TEG gained a meaningful post-intervention improvement in EQ-5D-3L index scores compared to the SRG. This is consistent with a previous finding that telerehabilitation results in comparable or modestly greater improvements in HRQoL in stroke survivors compared to usual care [

32]. Additionally, telerehabilitation has been reported to produce comparable outcomes to traditional rehabilitation in the recovery of activities of daily living and HRQoL [

33]. The positive impact on the TEG emphasizes the added value of therapist involvement in enhancing perceived health status beyond physical recovery alone. These results suggest that while both supervised and self-exercise can alleviate depressive symptoms, telerehabilitation with professional guidance may offer greater improvements across multiple domains of HRQoL.

Regression analysis examined the impact of group allocation on changes in key functional outcomes and fall efficacy. Group assignment played a meaningful role in predicting improvements in balance and mobility with TEG participants achieving greater functional improvements than those in the SRG. This suggests that therapist-supervised telerehabilitation can enhance neuromuscular control and dynamic balance beyond what is achieved through self-directed exercise. This finding aligns with evidence that telerehabilitation produces small-to-moderate enhancements in balance and functional mobility in stroke survivors compared to usual care [

34].

By contrast, changes in lower limb strength and fall-related self-efficacy were not significantly influenced by group allocation. This may suggest that these outcomes are more closely tied to consistent activity levels or baseline functional capacity rather than real-time professional input. These results are consistent with a meta-analysis reporting no additional gain in lower-extremity strength with physiotherapist guidance [

35].

In addition, the absence of a meaningful between-group difference in fall-related self-efficacy may reflect its multifactorial nature, which is influenced not only by physical function but also by psychological factors and environmental factors. Fall-related self-efficacy in chronic stroke survivors was independently associated with balance and mobility performance, emphasizing its complex relationship with both physical and cognitive domains [

36]. Moreover, evidence suggests that meaningful improvements in self-efficacy often require multi-component interventions, combining balance training, environmental modifications, and cognitive-behavioral strategies, rather than exercise alone [

37]. These findings suggest that while both TEG and SRG gained self-efficacy through consistent exercise routines, achieving greater improvements in fall-related confidence may necessitate additional components beyond structured physical rehabilitation. Accordingly, future telerehabilitation programs for stroke survivors might maximize impact by integrating targeted balance training, caregiver-supported home environment adaptations, and cognitive-behavioral elements aimed at addressing fall-related self-efficacy.

This study has several limitations. First, the relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings, and the study was not powered to detect subtle effects or interactions across subgroups. Second, participants were not blinded to group allocation, which may have introduced performance bias, especially given the motivational nature of supervised exercise. Third, although the intervention period was sufficient to observe short-term effects, longer follow-up is needed to determine the sustainability of functional and psychosocial improvements. Fourth, the SRG did not receive regular monitoring or adherence tracking, potentially underestimating the benefit of minimally supervised home-based interventions. Finally, despite the inclusion of regression analysis, only a limited set of predictors were examined, and other psychosocial or environmental variables that may influence HRQoL were not assessed.

5. Conclusions

This pilot randomized controlled trial found that a supervised home-based exercise program delivered through telerehabilitation led to greater improvements in balance and mobility among stroke survivors compared to unsupervised self-exercise. While both groups showed gains in lower limb strength and fall-related self-efficacy, only those receiving professional guidance demonstrated more meaningful progress in dynamic balance and gait ability. Additionally, HRQoL improved significantly only in the supervised group, although these changes were not strongly predicted by improvements in physical function. These findings support the effectiveness of structured, clinician-led telerehabilitation as a practical alternative when access to in-person services is limited.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L. and H.L.; methodology, H.L.; software, K.L. and H.R.; validation, K.L. and H.R.; formal analysis, K.L. and H.R.; investigation, H.L.; resources, H.L.; data curation, K.L. and H.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L..; writing—review and editing, K.L. and H.R.; supervision, H.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kangwon National University (KWNUIRB-2025-04-007-001).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants were fully informed of the study’s purpose and procedures and provided written informed consent prior to enrollment

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HRQoL |

Health-related quality of life |

| TEG |

Telerehabilitation exercise group |

| SRG |

self-exercise rehabilitation group |

| 30s-CST |

30-Second Chair Stand Test |

| ICCs |

intraclass correlation coefficients |

| BBS |

Berg Balance Scale |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go test |

| K-FES |

Korean version of the Falls Efficacy Scale |

| K-CES-D |

Korean version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| EQ-5D-3L |

EuroQol five-Dimension Three-Level descriptive system |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Description of the telerehabilitation exercise and self- exercise rehabilitation program.

Table A1.

Description of the telerehabilitation exercise and self- exercise rehabilitation program.

| Stage |

Exercise Description |

Exercise Type |

| Preparation |

Sit upright in a chair without leaning back, place both feet symmetrically on the floor. |

Postural Alignment |

| |

Place both hands on the lower abdomen and perform deep inhalation and exhalation (diaphragmatic breathing). |

Breathing Exercise |

| Main Exercise |

Interlock both hands and stretch the wrists to the left, right, up, and down while keeping the elbows extended. |

Flexibility Exercise |

| |

Interlock both hands and stretch the trunk to the left, right, up, and down while keeping the elbows extended. |

Flexibility Exercise |

| |

Interlock both hands and stretch diagonally upward and downward. |

Flexibility Exercise |

| |

Sit upright without leaning on the backrest, perform anterior and posterior pelvic tilts. |

Core Exercise |

| |

Cross one leg over the other while sitting, lift the pelvis on the side of the upper leg alternately. |

Core Exercise |

| |

Perform anterior/posterior pelvic tilts and lift the buttocks completely off the chair. |

Core Exercise |

| |

Wear a black resistance band on both feet and perform squatting movements. |

Core Exercise |

| |

In a supine position, lift the head and shoulders and hold for 10 seconds. |

Core Exercise |

| |

In a supine position with knees bent, lift the hips and maintain for 10 seconds. |

Core Exercise |

| |

In a bridge position with both knees bent, alternately extend and hold one leg at a time. |

Core Exercise |

| |

In a prone position supported by the elbows, shift weight forward, backward, left, and right using shoulder movements. |

Weight-Shifting

Exercise |

| |

In a prone position supported by both elbows, engage the abdominal muscles and lift the body in a straight line from head to waist (plank position). |

Core Exercise |

| |

In a half-kneeling position, step one leg back and shift weight onto the front leg. |

Lower Limb

Strengthening |

| Cool-down |

Place both hands on the lower abdomen and perform deep inhalation and exhalation. |

Breathing Exercise |

References

- GBD 2021 Stroke Risk Factor Collaborators Global, Regional, and National Burden of Stroke and Its Risk Factors, 1990-2021: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Neurol 2024, 23, 973–1003. [CrossRef]

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.O.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P.; F Grupper, M.; Rautalin, I. World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025. Int J Stroke 2025, 20, 132–144. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.W.; Zorowitz, R.; Bates, B.; Choi, J.Y.; Glasberg, J.J.; Graham, G.D.; Katz, R.C.; Lamberty, K.; Reker, D. Management of Adult Stroke Rehabilitation Care: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Stroke 2005, 36, e100-143. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Otaka, Y.; Osu, R.; Kumagai, M.; Kitamura, S.; Yaeda, J. Motivation for Rehabilitation in Patients With Subacute Stroke: A Qualitative Study. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Tabah, F.T.D.; Sham, F.; Zakaria, F.N.; Hashim, N.K.; Dasiman, R. Factors Influencing Stroke Patient Adherence to Physical Activity: A Systematic Review. JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGY AND GERIATRICS 2020, 68, 174–179. [CrossRef]

- Xing, F.; Liu, J.; Mei, C.; Chen, J.; Wen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Xie, S. Adherence to Rehabilitation Exercise and Influencing Factors among People with Acute Stroke: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Neurol. 2025, 16, 1554949. [CrossRef]

- Clipper, B. The Influence of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Technology. Nurse Lead 2020, 18, 500–503. [CrossRef]

- Golinelli, D.; Boetto, E.; Carullo, G.; Nuzzolese, A.G.; Landini, M.P.; Fantini, M.P. Adoption of Digital Technologies in Health Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review of Early Scientific Literature. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22, e22280. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Lin, C.-H.; Su, S.-W.; Chang, Y.-T.; Lai, C.-H. Feasibility and Effect of Interactive Telerehabilitation on Balance in Individuals with Chronic Stroke: A Pilot Study. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation 2021, 18, 71. [CrossRef]

- Winstein, C.J.; Stein, J.; Arena, R.; Bates, B.; Cherney, L.R.; Cramer, S.C.; Deruyter, F.; Eng, J.J.; Fisher, B.; Harvey, R.L.; et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery. Stroke 2016, 47, e98–e169. [CrossRef]

- Langhorne, P.; Bernhardt, J.; Kwakkel, G. Stroke Rehabilitation. The Lancet 2011, 377, 1693–1702. [CrossRef]

- Galvin, R.; Cusack, T.; O’Grady, E.; Murphy, T.B.; Stokes, E. Family-Mediated Exercise Intervention (FAME): Evaluation of a Novel Form of Exercise Delivery After Stroke. Stroke 2011, 42, 681–686. [CrossRef]

- Winstein, C.J.; Stein, J.; Arena, R.; Bates, B.; Cherney, L.R.; Cramer, S.C.; Deruyter, F.; Eng, J.J.; Fisher, B.; Harvey, R.L.; et al. Guidelines for Adult Stroke Rehabilitation and Recovery: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2016, 47, e98–e169. [CrossRef]

- Laver, K.E.; Adey-Wakeling, Z.; Crotty, M.; Lannin, N.A.; George, S.; Sherrington, C. Telerehabilitation Services for Stroke - Laver, KE - 2020 | Cochrane Library.

- Kumar, R.; Osborne, C.; Rinaldi, R.; Smith, J.A.D.; B.Juengst, S.; Barshikar, S. Rehabilitation Providers’ Experiences with Rapid Telerehabilitation Implementation During the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. J Phys Med Rehabil 2021, Volume 3, 51–60. [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.-M.; Kim, H.; Jang, J.; Cha, S.; Chang, W.K.; Jung, B.-K.; Park, D.-S.; Jee, S.; Ko, S.-H.; Shin, J.-H.; et al. Attitude Toward Telerehabilitation Among Physical and Occupational Therapists in Korea: A Brief Descriptive Report. Brain Neurorehabil 2023, 16, e8. [CrossRef]

- Eng, J.J.; Chu, K.S.; Kim, C.M.; Dawson, A.S.; Carswell, A.; Hepburn, K.E. A Community-Based Group Exercise Program for Persons with Chronic Stroke. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003, 35, 1271–1278. [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.J.; Rikli ,Roberta E.; and Beam, W.C. A 30-s Chair-Stand Test as a Measure of Lower Body Strength in Community-Residing Older Adults. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 1999, 70, 113–119. [CrossRef]

- Mao, H.-F.; Hsueh, I.-P.; Tang, P.-F.; Sheu, C.-F.; Hsieh, C.-L. Analysis and Comparison of the Psychometric Properties of Three Balance Measures for Stroke Patients. Stroke 2002, 33, 1022–1027. [CrossRef]

- Flansbjer, U.-B.; Holmbäck, A.M.; Downham, D.; Patten, C.; Lexell, J. Reliability of Gait Performance Tests in Men and Women with Hemiparesis after Stroke. J Rehabil Med 2005, 37, 75–82. [CrossRef]

- Park, G.; Cho, B.; Kwon, I.S.; Park, B.J.; Kim, T.; Cho, K.Y.; Park, U.J.; Kim, M.J. Reliability and Validity of Korean Version of Falls Efficacy Scale-International (KFES-I). Journal of the Korean Academy of Rehabilitation Medicine 34, 554–559.

- J, C.M. Diagnostic Validity of the CES-D (Korean Version) in the Assessment of DSM-III-R Major Depression. Journal of Korean Neuropsychiatric Association 1993, 32, 381.

- Golicki, D.; Niewada, M.; Karlińska, A.; Buczek, J.; Kobayashi, A.; Janssen, M.F.; Pickard, A.S. Comparing Responsiveness of the EQ-5D-5L, EQ-5D-3L and EQ VAS in Stroke Patients. Qual Life Res 2015, 24, 1555–1563. [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Lin, K.-C.; Liing, R.-J.; Wu, C.-Y.; Chen, C.-L.; Chang, K.-C. Validity, Responsiveness, and Minimal Clinically Important Difference of EQ-5D-5L in Stroke Patients Undergoing Rehabilitation. Qual Life Res 2016, 25, 1585–1596. [CrossRef]

- Irish, J.; Sharma, A.; Labbe, D.; Arsenault, S.; White, K.; Sakakibara, B.M. Stroke Virtual Rehabilitation in Rural Communities: Exploring the Perceptions of Stroke Survivors, Caregivers, Clinicians, and Health Administrators. Disabil Rehabil 2024, 46, 6352–6359. [CrossRef]

- Raymond, M.J.; Christie, L.J.; Kramer, S.; Malaguti, C.; Mok, Z.; Gardner, B.; Giummarra, M.J.; Alves-Stein, S.; Hudson, C.; Featherston, J.; et al. Delivery of Allied Health Interventions Using Telehealth Modalities: A Rapid Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Healthcare 2024, 12, 1217. [CrossRef]

- Billinger, S.A.; Arena, R.; Bernhardt, J.; Eng, J.J.; Franklin, B.A.; Johnson, C.M.; MacKay-Lyons, M.; Macko, R.F.; Mead, G.E.; Roth, E.J.; et al. Physical Activity and Exercise Recommendations for Stroke Survivors: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014, 45, 2532–2553. [CrossRef]

- Pollock, A.; Baer, G.; Campbell, P.; Choo, P.L.; Forster, A.; Morris, J.; Pomeroy, V.M.; Langhorne, P. Physical Rehabilitation Approaches for the Recovery of Function and Mobility Following Stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014, 2014, CD001920. [CrossRef]

- Cikajlo, I.; Rudolf, M.; Goljar, N.; Burger, H.; Matjačić, Z. Telerehabilitation Using Virtual Reality Task Can Improve Balance in Patients with Stroke. Disability and Rehabilitation 2012, 34, 13–18. [CrossRef]

- Howe, T.E.; Rochester, L.; Neil, F.; Skelton, D.A.; Ballinger, C. Exercise for Improving Balance in Older People - Howe, TE - 2011 | Cochrane Library.

- Linder, S.M.; Rosenfeldt, A.B.; Bay, R.C.; Sahu, K.; Wolf, S.L.; Alberts, J.L. Improving Quality of Life and Depression After Stroke Through Telerehabilitation. Am J Occup Ther 2015, 69, 6902290020p1-10. [CrossRef]

- Gebrye, T.; Mbada, C.; Fatoye, F.; Anazodo, C. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation on Quality of Life in Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta - Analysis. Physical Therapy Reviews 2024, 29, 187–196.

- Tchero, H.; Tabue Teguo, M.; Lannuzel, A.; Rusch, E. Telerehabilitation for Stroke Survivors: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Med Internet Res 2018, 20, e10867. [CrossRef]

- Su, Z.; Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Zheng, M.; Michael, N.; Lu, S.; Wang, W.; et al. The Effect of Telerehabilitation on Balance in Stroke Patients: Is It More Effective than the Traditional Rehabilitation Model? A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials Published during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Danielsson, A.; Meirelles, C.; Willen, C.; Sunnerhagen, K.S. Physical Activity in Community-Dwelling Stroke Survivors and a Healthy Population Is Not Explained by Motor Function Only. PM R 2014, 6, 139–145. [CrossRef]

- Pang, M.Y.C.; Eng, J.J. Fall-Related Self-Efficacy, Not Balance and Mobility Performance, Is Related to Accidental Falls in Chronic Stroke Survivors with Low Bone Mineral Density. Osteoporos Int 2008, 19, 919–927. [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.X.; De Silva, D.A.; Toh, Z.A.; Pikkarainen, M.; Wu, V.X.; He, H.-G. The Effectiveness of Self-Management Interventions with Action-Taking Components in Improving Health-Related Outcomes for Adult Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Disabil Rehabil 2022, 44, 7751–7766. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants. (N=35).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the participants. (N=35).

| Parameters |

TEG (N=18) |

SRG (N=17) |

t(p-value) |

| Age |

60.44±14.63 |

65.53±8.30 |

0.107 |

| Gender (male/female) |

10(55.6)/8(44.4) |

6(35.3)/11(64.7) |

0.229 |

| Affected side (Rt/Lt) |

10(55.6)/8(44.4) |

9(52.9)/8(47.1) |

0.877 |

| Height (cm) |

162.50±10.30 |

158.71±7.82 |

0.115 |

| Weight (kg) |

59.11±8.79 |

58.85±11.31 |

0.446 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

22.44±2.99 |

23.24±3.82 |

0.248 |

| Period of illness (month) |

174.78±68.47 |

167.18±43.68 |

0.350 |

Table 2.

Comparison of physical function within and between groups. (N=35).

Table 2.

Comparison of physical function within and between groups. (N=35).

| Measures |

|

TEG (N=18) |

SRG (N=17) |

t(p-value) |

| 30s-CST (rep) |

Pretest |

8.56±1.50 |

8.53±1.59 |

|

| |

Posttest |

9.61±1.61 |

9.29±1.57 |

|

| |

Post-pre |

1.06±0.54 |

0.77±0.66 |

1.191(0.243) |

| |

t(p) |

8.304(<0.001) |

4.747(<0.001) |

|

| BBS (points) |

Pretest |

30.72±5.89 |

31.24±6.14 |

|

| |

Posttest |

34.61±6.29 |

33.18±6.29 |

|

| |

Post-pre |

3.88±3.08 |

1.94±1.19 |

2.488(0.010) |

| |

t(p) |

5.348(<0.001) |

6.684(<0.001) |

|

| TUG (sec) |

Pretest |

21.51±8.68 |

21.94±6.79 |

|

| |

Posttest |

19.22±7.76 |

20.87±6.52 |

|

| |

Post-pre |

-2.29±1.52 |

-1.08±1.42 |

-2.439(0.020) |

| |

t(p) |

-4.301(<0.001) |

-3.129(0.006) |

|

| K-FES (points) |

Pretest |

71.28±12.86 |

70.92±16.39 |

|

| |

Posttest |

73.67±12.05 |

72.18±16.29 |

|

| |

Post-pre |

2.39±2.97 |

1.24±1.39 |

1.438(0.151) |

| |

t(p) |

3.409(0.003) |

3.656(0.002) |

|

Table 3.

Comparison of depression and quality of life within and between groups. (N=35).

Table 3.

Comparison of depression and quality of life within and between groups. (N=35).

| Measures |

|

TEG (N=18) |

SRG (N=17) |

t(p-value_ |

| K-CES-D (points) |

Pretest |

14.67±2.59 |

14.82±1.63 |

|

| |

Posttest |

13.28±2.74 |

13.94±2.22 |

|

| |

Post-pre |

1.39±1.15 |

0.88±1.45 |

-1.149(0.259) |

| |

t(p) |

5.147(<0.001) |

2.504(0.023) |

|

| EQ-5D-3L (points) |

Pretest |

0.650±0.192 |

0.639±0.179 |

|

| |

Posttest |

0.747±0.143 |

0.674±0.169 |

|

| |

Post-pre |

0.096±0.095 |

0.035±0.098 |

1.878(0.035) |

| |

t(p) |

-4.264(<0.001) |

-1.456(0.165) |

|

Table 4.

Linear regression of group allocation on change in physical function. (N=35).

Table 4.

Linear regression of group allocation on change in physical function. (N=35).

| Independent variable |

Measures |

(Constant) |

β |

t(p) |

F(p) |

R2 |

| Group |

30s-CST_diff |

1.235*** |

-.205 |

-1.202 |

1.444 |

.042 |

| BBS_diff |

5.837*** |

-.390 |

-2.434* |

5.925* |

.152 |

| TUG_diff |

-3.500** |

.391 |

2.439* |

5.950* |

.153 |

| K-FES_diff |

3.542** |

-.246 |

-1.455 |

2.117 |

.060 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).