1. Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common neurological disorders in the older population, and significantly impairs physical function and independence in daily life [

1]. Stroke survivors often experience a range of neurological deficits, including alterations in consciousness, sensory and motor impairments, and altered muscle tone, all of which negatively affect their balance. Additionally, these patients may experience dysphagia and bowel dysfunction, further deteriorating their overall quality of life [

2]. Among the various functional impairments, patients with stroke commonly exhibit increased spatiotemporal variability in gait, leading to a decline in lower limb function [

3]. Consequently, these patients often present with a prolonged swing phase on the affected side, slower walking speed, and shorter stride length and width [

4]. These patients also experience abnormal gait patterns and struggle with muscle activation and timing control, which further limits their functional walking ability [

5].

In daily life, patients with stroke are required not only to perform straight gaits (SG) and curved gaits (CG), such as walking around furniture or navigating corners in hallways. CG accounts for approximately 30% of daily walking tasks and poses a more significant challenge for these patients [

6,

7].

CG requires precise coordination between body segments, including axial rotation control and maintenance of gaze in the direction of movement, which requires complex commands from the central nervous system [

8,

9]. Unlike SG, CG involves asymmetric lower-limb movements, with the outer leg covering a greater distance than the inner leg. Furthermore, maintaining propulsion during CG requires increased mediolateral ground reaction forces, and shifting body weight to the inner leg, and thereby requiring greater lower limb stability than during SG [

10,

11].

Chen et al. (2014) demonstrated that patients with stroke exhibit insufficient muscle activation and employ inefficient kinematic strategies during CG, leading to significantly reduced walking speeds compared to healthy individuals. Moreover, when navigating curves toward the affected side, these patients experience impaired function of the contralateral leg function, leading to a decrease in balance ability and an increased risk of falls [

10]. Despite the known difficulties that patients with stroke experience during CG and the functional changes related to foot position, previous studies have primarily focused on comparing SG and CG, highlighting the importance and effects of CG. However, a lack of research exploring the functional differences in gait based on the foot position during CG training exists.

The effect CG on gait performance based on the position of the paretic foot position was investigated. CG training, particularly when the paretic foot is positioned on the inside of a curved path, was hypothesized to result in the most significant improvement in walking ability.

2. Materials and Methods

This study included 45 patients with subacute stroke and either cerebral infarction or hemorrhage who were able to walk ≥ 6 m without assistive devices. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Myongji Chun-Hye Rehabilitation Hospital (approval no. MJCHIRB-2023-05), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before to the study.

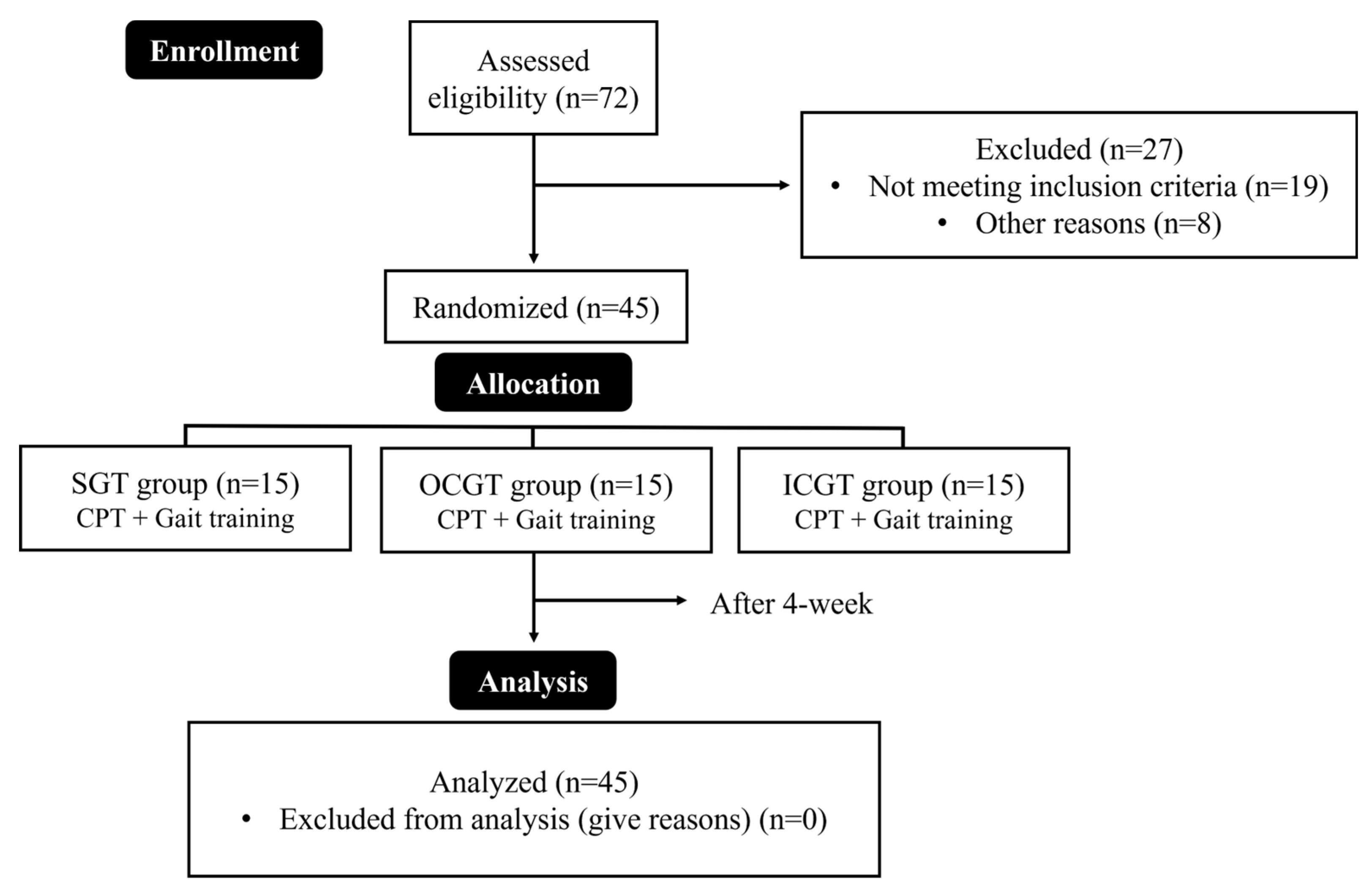

The participants were randomly assigned to three groups using a random function in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA): the straight gait training group (SGT, n = 15), outside paretic foot placement curved gait training group (OCGT, n = 15), and inside paretic foot placement curved gait training group (ICGT, n = 15). All groups underwent conservative physical therapy (CPT) and gait training for 30 minutes (15 minutes each) five times per week for four weeks (

Figure 1). All interventions were supervised by therapists to prevent falls and accidents, and protective equipment (corner protectors, mattresses, etc.) was used to ensure safety. If the participants lost balance or reported dizziness during training, they were allowed to rest for one minute before resuming training.

2.1. Intervention

2.1.1. CPT

CPT is based on neurodevelopmental therapy and includes joint mobilization exercises for the hip, knee, and ankle joints; lower limb muscle preparation exercises; and stability enhancement exercises through weight shifting prior to gait training. It also included weight-shifting exercises in the standing position to improve the awareness of the paretic leg. Each session lasted five minutes.

2.1.2. SGT

The SGT began with the participants seated, and they were trained to walk back and forth along a 20-meter straight path. Participants maintained a forward gaze while walking, and after reaching the 20-meter turning point, they turned in their preferred direction to repeat the 20-meter walk [

12]. All participants averaged 36.2 seconds in the pre-intervention timed up and go (TUG) test. To ensure participant safety and maintain continuous walking for 5 min, the time to complete the 20-meter distance was maintained at ≤ 2 min.

2.1.3. CG Training

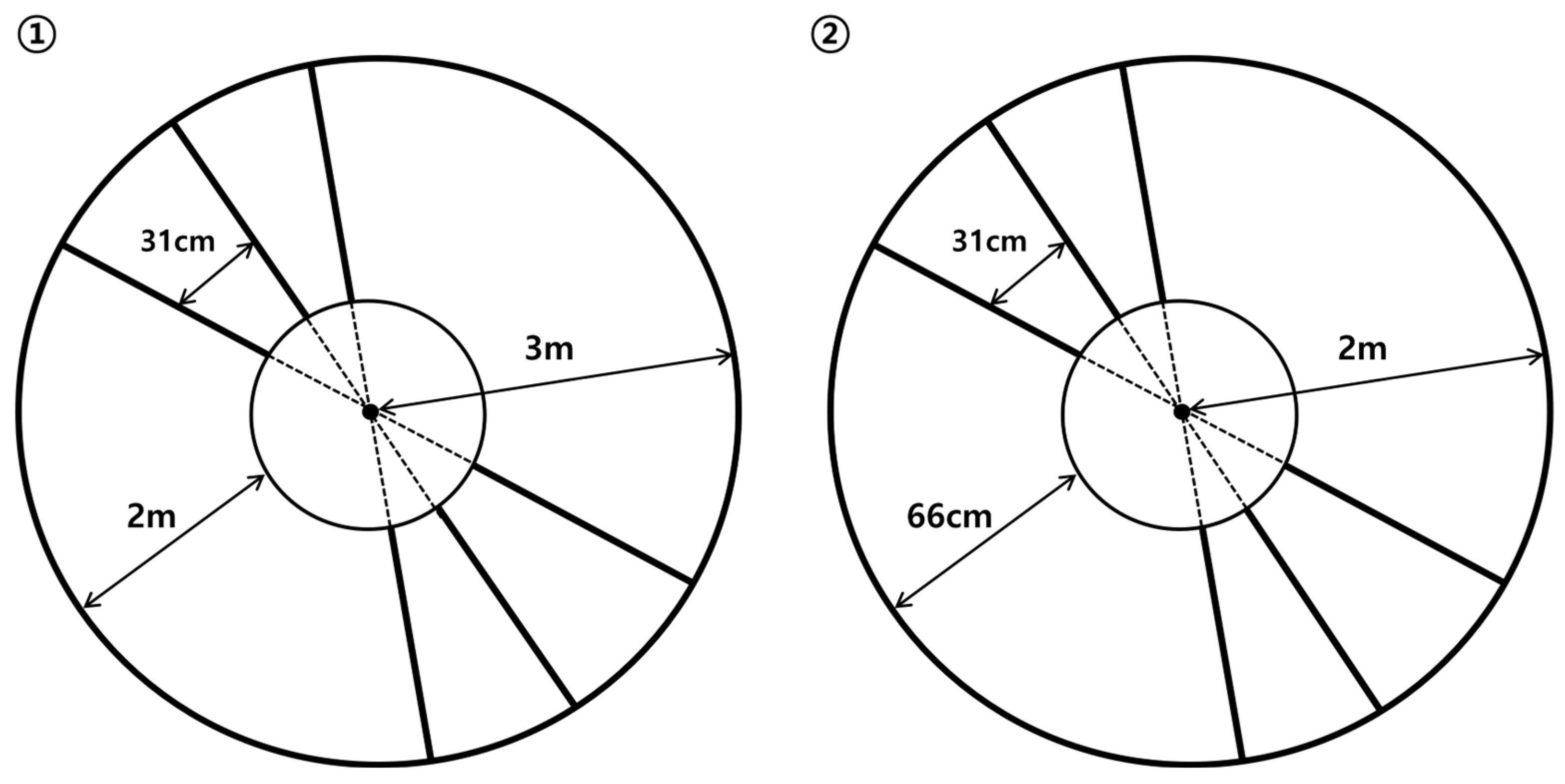

CG training was conducted according to previous studies, where a circular path with ladder-shaped steps was used to adjust the stride length [

12,

13]. The walking path consisted of a large circle (total length: 18.8 m, radius: 3 m, and curvature: 0.75 m) and a small circle (total length: 12.6 m, radius: 2 m, and curvature: 0.5 m), both created using 1.7 cm-wide tape. Additional radii were drawn 31 cm apart along the outer third of the path to create the ladder shape. A concentric inner circle was created by connecting points in the inner third of the radii, with the distance from the inner circle being 2 m for the large circle and 66 cm for the small circle (

Figure 2).

Training began with the large circle in which participants walked along a curved path, placing their feet as close to the ladder-shaped markers as possible. If no balance issues or dizziness occurred during the 8-minute session in the large circle, the training progressed to the small circle using the same method. To minimize the differences in walking distance, the time taken to complete one full rotation in the large circle was maintained at ≤ 1 min, and ≤ 30 s for the small circle. This procedure was repeated with foot placement adjusted according to the group assignment.

2.2. Assessment

2.2.1. Muscle Activity

Muscle activity was measured using a surface electromyography (EMG) system, Free EMG 1000 (BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy). Data were processed using an EMG Analyzer v2.9.37.0 (BTS Bioengineering, Milan, Italy). The EMG signals were sampled at a rate of 1,024 Hz and filtered using a bandwidth of 20–500 Hz to remove the noise. Two adhesive electrodes (3M 2223H type) were used for each muscle. Prior to electrode attachment, the skin of the participant was shaved and cleansed with alcohol to minimize resistance and noise. Additional tape was used to secure the electrodes.

The measured muscles included three key components: the gluteus medius (GM), which provides stability to the lower limbs and pelvis during walking, maintains pelvic alignment, and generates mediolateral ground reaction forces to ensure balance of the center of mass; the vastus medialis (VM), which plays a significant role in push-off and affects knee extension and joint stability; and the vastus lateralis (VL), which is crucial during the initial phase of push-off, absorbing impact and controlling leg position during walking [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Electrode placement was performed following the SENIAM guidelines [

19] (

Table 1).

To standardize the data, EMG signals were measured for 5 s, and the raw data were converted to root mean square (RMS) values. Considering the participants were patients with stroke, the EMG signal values were expressed as a percentage of the voluntary reference contraction (%RVC). %RVC was calculated by dividing the RMS of the measured muscle (measurement value) by the RMS of the standard contraction and then converting it to a percentage. The RMS value for the standard contraction was measured and set using the average of 4 s, excluding 0.5 seconds before and after the 5-second period of standing still without movement. The RMS measurement value was obtained from the sit-to-stand movement without armrests, with the EMG signal being measured three times (1-minute intervals) at the moment when the hips lifted off and touched the chair, and the average of these values was used.

2.2.2. Gait Parameter

Gait parameters were measured using the Zebris FDM Treadmill System (Zebris Medical GmbH, Germany). Participants walked barefoot on the treadmill for 30 s, and five gait parameters were measured for the paretic leg using Zebris FDM-T software (version 1.18.44): step length, stance phase, swing phase, velocity, and maximum force (

Table 2). All gait parameters, except for the swing phase, indicated an improvement in gait function when they increased. The Zebris FDM-T system has high reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.97 [

20].

2.2.3. TUG Test

The TUG test assesses the dynamic balance, functional mobility, and gait ability in patients with stroke. The test includes sitting, standing, and turning, making it a quick assessment tool and predictor of gait function [

21]. The participants were seated in an armchair, stood up at the signal of the evaluator, walked 3 meters, turned around, and sat back down. The time required was recorded using a stopwatch [

22]. The TUG test has high test-retest reliability (ICC = 0.95) [

23]. The test was performed thrice, and the average value was used.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Data for all variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Normality was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Paired t-tests were used for within-group comparisons and one-way ANOVA was used for between-group comparisons. The significance level was set at α=0.05.

3. Results

No significant differences were observed in general characteristics between the groups (

Table 3). The results of muscle activity, gait variables, and balance ability before and after the 4-week intervention are presented in

Table 4 and

Table 5. Significant changes were observed in the activity of all muscles across all groups (p < 0.00), with the GM showing a significant difference only between the SGT and ICGT groups. However, there were no significant differences in the VM and VL between the groups.

All groups showed significant differences in all gait parameters before and after the intervention; however, no significant differences were observed between the groups.

Regarding the balance assessment, there were significant differences between all groups before and after the intervention (p < 0.00), and a significant difference was observed only between the SGT and ICGT groups in the intergroup comparison (p < 0.00).

4. Discussion

The effects of a 4-week CG training based on the placement of the affected foot on lower limb muscle activity, gait variables, and balance ability in patients with subacute stroke were investigated in this study. Although significant changes were observed in all the groups before and after the intervention, some differences were observed depending on the training method and foot placement. The initial hypothesis was that the ICGT would demonstrate greater improvements in muscle activity, gait variables, and balance ability than the other groups; however, this was only partially supported by the results.

During CG, weight is transferred to the leg on the inner side of the curved path, requiring greater lower limb stability than during SG training [

11]. Additionally, GM activation may improve body awareness by facilitating pelvic rotation and weight transfer to the inner body [

13]. In this study, the GM activity significantly increased in all groups before and after the intervention; however, significant differences were found only between the SGT and ICGT groups. This suggests that the ICGT results in a greater increase in the weight-bearing capacity of the affected leg, leading to improved GM activation and potentially enhanced gait ability [

16].

The VM and VL also significantly improved within the groups before and after the intervention, but no significant differences were observed between the groups. This indicates that VM and VL muscle activation can be enhanced regardless of the training method, and this increased muscle activity likely contributes to improved knee stability and ground reaction forces during gait [

24,

25]. The results demonstrated that the stance phase and ground reaction force increased by 4.5% in the SGT group, and by 5.3% and 6.7% in the OCGT and ICGT groups, respectively. This improvement was linked to an increase in step length, with the average step length increasing by approximately 7 cm and 11 cm in the SGT and CG training groups, respectively. This led to an approximate 0.4 m/s increase in walking speed post-intervention [

26,

27].

In the TUG test, which assessed balance ability, significant improvements were observed in all groups post-intervention, with the SGT, OCGT, and ICGT groups exhibiting reductions in TUG test times of 5.7 seconds, 8.5 seconds, and 12.5 seconds, respectively. This indicated improved dynamic balance ability. Arabzadeh et al. (2023) reported that increased GM activation leads to enhanced pelvic stability, which in turn improves balance ability by stabilizing the proximal lower limb. [

28]. In this study, GM activation increased by 18% in the SGT group and 50% in the ICGT group, with a 42% greater improvement in the ICGT group. This activation affected the TUG test results, ultimately resulting in a significant difference between the SGT and ICGT groups.

Moreover, during walking, the eyes and head typically face the direction of travel, guide trunk movement and facilitate weight transfer, leading to improvements in dynamic balance and gait ability. However, during CG, the gaze is directed toward the inner side of the curve as the person walks [

8,

9,

29]. However, during CG, the gaze is directed toward the inner side of the curve as the person walks. This suggests that, during CG, the trunk shifts toward the leg on the inside of the curved path, promoting weight transfer. Jin and Song (2017) revealed that when weight transfer to the inner leg increases, the load on that leg also increases, providing more afferent sensory information that can improve weight-shifting ability and dynamic balance [

13]. This may explain the greater improvement in balance ability in the ICGT group than in the SGT group, as the ICGT group experienced increased weight transfer to the affected foot.

Overall, in patients with subacute stroke, CGT resulted in a 42% greater improvement in muscle activation, a 1.2% increase in the stance phase, and a 4 cm longer step length than SGT, which positively impacted overall gait ability. Specifically, the ICGT was more effective in improving gait ability because of a greater increase in GM activation, enhanced weight transfer to the inner leg, and increased sensory feedback.

This study had several limitations. First, it did not consider the movements of the pelvis, trunk, and upper limbs, which are related to gait ability in patients with stroke were not considered. Second, the curvature was not varied at regular intervals during the intervention period. Third, muscle activation was measured only in the gluteus medius, vastus medialis, and vastus lateralis. Future studies should measure the activation of other stability muscles, considering changes in curvature as well as movements of the trunk and upper limbs.

5. Conclusions

The effects of 4-week CG training based on the placement of the affected foot on lower limb muscle activity, gait variables, and balance ability in patients with subactue stroke were investigated in this study. The results suggest that muscle activity, balance ability, and gait performance can improve regardless of the gait training method. However, training with the affected foot positioned on the inner side of the curve was more effective in enhancing muscle activation and balance ability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.L. and Y.P.; methodology, Y.L. and Y.P.; validation, C.L. and Y.L.; formal analysis, Y.L., Y.P.; investigation, Y.P.; resources, Y.P.; data curation, C.L. and Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.P.; writing—review and editing, C.L and Y.L.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, C.L.; project administration, C.L. and Y.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Myongji Chun-Hye Rehabilitation Hospital (MJCHIRB-2023-05).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical considerations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Campbell, B.; De Silva, D.; Macleod, M.; Coutts, S.; Schwamm, L.; Davis, S.; Donnan, G. Ischaemic Stroke Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2019, 5, 70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, S.; Schmitz, T.; Fulk, G. Physical Rehabilitation 6th ed (p. 661); FA Davis: Philadelphia, PA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, P.; Enzastiga, D.; Casamento-Moran, A.; Christou, E.A.; Lodha, N. Increased temporal stride variability contributes to impaired gait coordination after stroke. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 12679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Zhong, D.; Ye, J.; He, M.; Liu, X.; Zheng, H.; Jin, R.; Zhang, S.-l. Rehabilitation for balance impairment in patients after stroke: a protocol of a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2019, 9, e026844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, S.; Patten, C.; Kautz, S.A. Altered muscle activation patterns (AMAP): an analytical tool to compare muscle activity patterns of hemiparetic gait with a normative profile. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2019, 16, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcato, A.M.; Godi, M.; Giardini, M.; Arcolin, I.; Nardone, A.; Giordano, A.; Schieppati, M. Abnormal gait pattern emerges during curved trajectories in high-functioning Parkinsonian patients walking in line at normal speed. Plos one. 2018, 13, e0197264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godi, M.; Giardini, M.; Schieppati, M. Walking along curved trajectories. Changes with age and Parkinson’s disease. Hints to rehabilitation. Front Neurol. 2019, 10, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellone, S.; Mancini, M.; King, L.A.; Horak, F.B.; Chiari, L. The quality of turning in Parkinson’s disease: a compensatory strategy to prevent postural instability? J NeuroEng Rehabil. 2016, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maidan, I.; Bernad-Elazari, H.; Giladi, N.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Mirelman, A. When is higher level cognitive control needed for locomotor tasks among patients with Parkinson’s disease? Brain topography. 2017, 30, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-H.; Yang, Y.-R.; Cheng, S.-J.; Chan, R.-C.; Wang, R.-Y. Neuromuscular and biomechanical strategies of turning in ambulatory individuals post-stroke. Chin J Physiol. 2014, 57, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia Bejarano, N.; Pedrocchi, A.; Nardone, A.; Schieppati, M.; Baccinelli, W.; Monticone, M.; Ferrigno, G.; Ferrante, S. Tuning of muscle synergies during walking along rectilinear and curvilinear trajectories in humans. Ann Biomed Eng. 2017, 45, 1204–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Lee, Y.; Park, S.; Lee, S.; Lim, C. Effects of Curved-Path Gait Training on Gait Ability in Middle-Aged Patients with Stroke: Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; 2023; p. 1777. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Song, B. The effects of curved path stride gait training on the lower extremity muscle activity and gait ability of patients with stroke. Korean J Phys, Multi Health Dis. 2017, 60, 141–168. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikbabu, S.; Chakrapani, M.; Ganesan, S.; Ellajosyla, R. Pelvic alignment in standing, and its relationship with trunk control and motor recovery of lower limb after stroke. Neurol Clin Neuro. 2017, 5, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebesi, B.; Fésüs, Á.; Varga, M.; Atlasz, T.; Vadász, K.; Mayer, P.; Vass, L.; Meszler, B.; Balázs, B.; Váczi, M. The indirect role of gluteus medius muscle in knee joint stability during unilateral vertical jump and landing on unstable surface in young trained males. Appl Sci. 2021, 11, 7421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P Darji, P.; J Diwan, S.; Ranjan, S. Effect of Four Weeks Level Ground Side Walking Training on Gluteus Medius Muscle Activation and Gait Parameters in Subjects with Post Stroke Chronic Hemiparesis. Int J Health Sci Res. 2024, 14, 54–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Montecinos, C.; Pérez-Alenda, S.; Querol, F.; Cerda, M.; Maas, H. Changes in muscle activity patterns and joint kinematics during gait in hemophilic arthropathy. Front physiol. 2020, 10, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjoerdsma, M.; Caresio, C.; Tchang, B.; Meeder, A.; van de Vosse, F.; Lopata, R. The feasibility of dynamic musculoskeletal function analysis of the vastus lateralis in endurance runners using continuous, hands-free ultrasound. Appl Sci. 2021, 11, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermens, H.J.; Freriks, B.; Merletti, R.; Stegeman, D.; Blok, J.; Rau, G.; Disselhorst-Klug, C.; Hägg, G. European recommendations for surface electromyography. Roe Res Devel. 1999, 8, 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Item-Glatthorn, J.F.; Casartelli, N.C.; Maffiuletti, N.A. Reproducibility of gait parameters at different surface inclinations and speeds using an instrumented treadmill system. Gait & posture. 2016, 44, 259–264. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K. Balance training with weight shift-triggered electrical stimulation for stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Brain sci. 2023, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kear, B.M.; Guck, T.P.; McGaha, A.L. Timed up and go (TUG) test: normative reference values for ages 20 to 59 years and relationships with physical and mental health risk factors. J prim Care Community Health. 2017, 8, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.P.; Tou, J.I.S.; Mimi, M.T.; Ng, S.S. Reliability and validity of the timed up and go test with a motor task in people with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017, 98, 2213–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, J.T.; Pietrosimone, B.; Harkey, M.S.; Luc, B.A.; Pamukoff, D.N. Quadriceps Function and Gait Kinetics after Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016, 48, 1664–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.J.; Park, S.K.; Uhm, Y.H.; Park, S.H.; Chun, D.W.; Kim, J.H. The correlation between muscle activity of the quadriceps and balance and gait in stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016, 28, 2289–2292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshioka, K.; Watanabe, T.; Maruyama, N.; Yoshioka, M.; Iino, K.; Honda, K.; Hayashida, K. Two-month individually supervised exercise therapy improves walking speed, step length, and temporal gait symmetry in chronic stroke patients: A before–after trial. In Proceedings of the Healthcare; 2022; p. 527. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuchi, C.A.; Fukuchi, R.K.; Duarte, M. Effects of walking speed on gait biomechanics in healthy participants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Systematic reviews. 2019, 8, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, S.; Kamali, F.; Bervis, S.; Razeghi, M. The hip joint mobilization with movement technique improves muscle activity, postural stability, functional and dynamic balance in hemiplegia secondary to chronic stroke: a blinded randomized controlled trial. BMC neurol. 2023, 23, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Lu, J.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G. Effects of gaze stabilization exercises on gait, plantar pressure, and balance function in post-stroke patients: a randomized controlled trial. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).