Submitted:

25 October 2025

Posted:

27 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

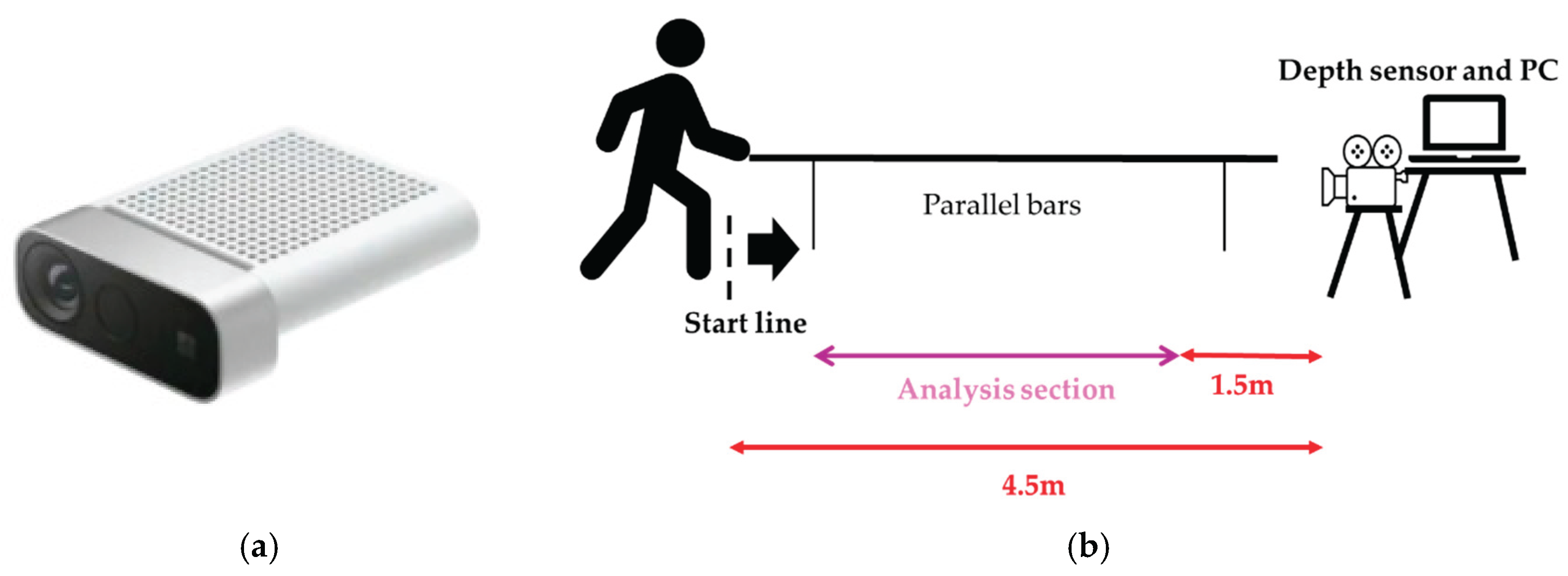

2.2. Measuring Equipment

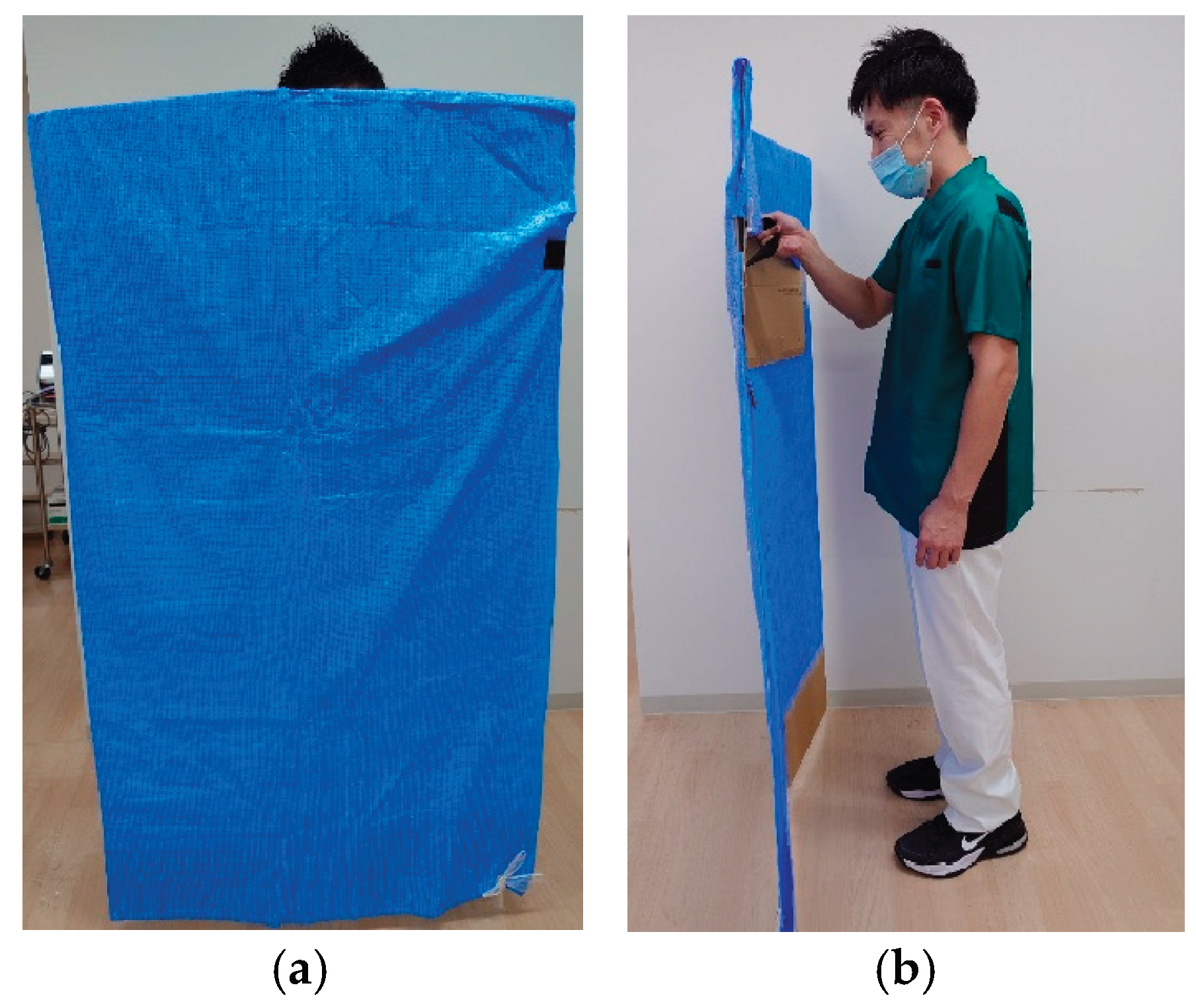

2.3. Gait Assessment

2.4. Data Processing

2.5. Statical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

3.2. Correlations Between Compensatory Movements and Gait/Functional Parameters at Initial Assessment

| Spatiotemporal and kinematic variables |

Paretic side femoral abduction angle |

Paretic side pelvic hike angle |

|||||

| Correlation | p-value | Correlation | p-value | ||||

| Gait speed (m/sec) a | -0.17 | 0.446 | -0.46 | 0.031 | |||

| Gait cycle time (sec) b | 0.22 | 0.326 | 0.51 | 0.016 | |||

| Double stance time (sec) a | 0.13 | 0.569 | 0.66 | 0.001 | |||

| Paretic stance time (sec) a | 0.14 | 0.544 | 0.56 | 0.006 | |||

| Paretic swing time (sec) b | 0.42 | 0.053 | 0.57 | 0.002 | |||

| Non-paretic swing time (sec) b | -0.26 | 0.234 | -0.04 | 0.875 | |||

| Stride length on the paretic side (m) a | -0.09 | 0.686 | -0.25 | 0.253 | |||

| Step length on the paretic side (m) a | 0.11 | 0.615 | -0.02 | 0.927 | |||

| Step length on the non-paretic side (m) a | -0.05 | 0.818 | -0.38 | 0.080 | |||

| Step width (m)a | 0.46 | 0.031 | 0.36 | 0.095 | |||

| Paretic pelvic hike angle (°) a | 0.33 | 0.131 | - | - | |||

| H1 (°) a | 0.06 | 0.796 | -0.21 | 0.349 | |||

| H2 (°) a | 0.11 | 0.639 | -0.19 | 0.388 | |||

| H3 (°) a | -0.02 | 0.917 | 0.01 | 0.950 | |||

| H4 (°) a | -0.09 | 0.698 | -0.17 | 0.452 | |||

| H5 (°) a | 0.10 | 0.671 | -0.19 | 0.391 | |||

| H6 (°) a | 0.26 | 0.234 | -0.22 | 0.332 | |||

| K1 (°) a | 0.17 | 0.452 | -0.04 | 0.866 | |||

| K2 (°) a | 0.34 | 0.119 | 0.11 | 0.636 | |||

| K3 (°) b | -0.19 | 0.391 | -0.10 | 0.669 | |||

| K4 (°) a | -0.32 | 0.145 | -0.50 | 0.018 | |||

| K5 (°) a | -0.09 | 0.703 | -0.35 | 0.108 | |||

| K6 (°) a | -0.03 | 0.903 | -0.28 | 0.210 | |||

|

a Pearson's correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) b Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) | |||||||

| SIAS evaluation items |

Paretic side femoral abduction angle |

Paretic side pelvic hike angle |

|||||

| Correlation | p-value | Correlation | p-value | ||||

| Hip joint b | -0.10 | 0.654 | -0.44 | 0.041 | |||

| Knee joint b | -0.32 | 0.149 | -0.38 | 0.078 | |||

| Ankle joint b | -0.56 | 0.007 | -0.40 | 0.064 | |||

| L/E deep tendon reflex b | -0.20 | 0.372 | 0.02 | 0.939 | |||

| L/E muscle tone b | -0.06 | 0.791 | 0.05 | 0.833 | |||

| L/E superficial sensation b | -0.45 | 0.034 | -0.11 | 0.634 | |||

| L/E deep sensation b | -0.20 | 0.368 | 0.11 | 0.623 | |||

| Ankle joint range of motion b | -0.05 | 0.822 | -0.18 | 0.417 | |||

| Abdominal strength b | 0.17 | 0.444 | 0.01 | 0.957 | |||

| L/E: Lower extremity | |||||||

| b Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) | |||||||

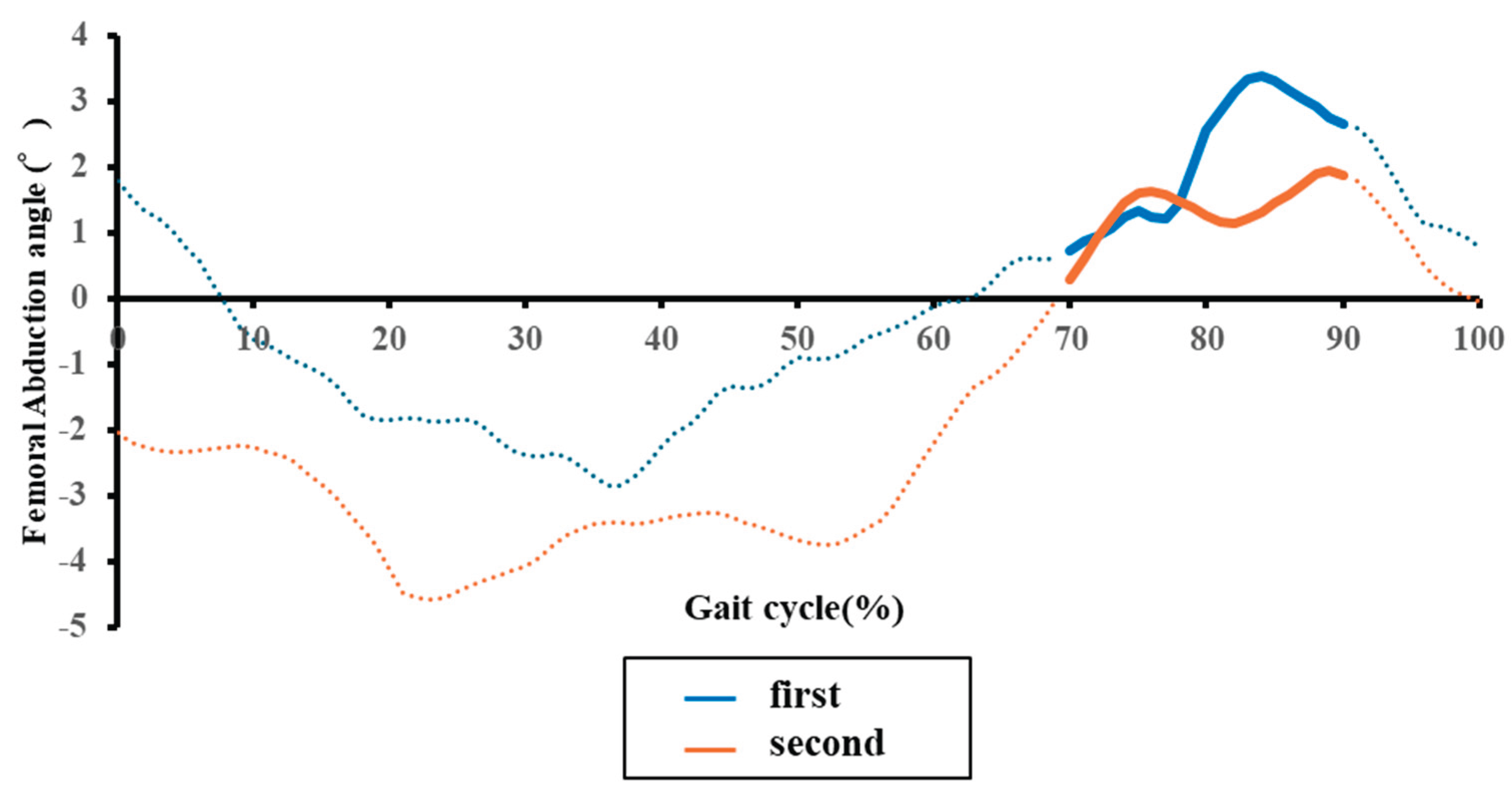

3.3. Longitudinal Changes in Gait Parameters

3.4. Longitudinal Changes in SIAS Scores

3.5. Correlations Between Changes in Compensatory Movements and Changes in Gait Parameters and Physical Function Assessment Items

Discussion

4.1. Relationship Between Compensatory Movements and Gait/Physical Function at Initial Assessment

4.2. Longitudinal Changes in Gait: Context for Compensation Attenuation

4.3. Temporal Changes in Paretic Femoral Abduction Angle and Its Relationship with Physical Function

4.4. Temporal Changes in Paretic Pelvic Hike and Its Relationship with Physical Function

4.5. Limitation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Imanawanto, K., Andriana, M., & Satyawati, R. (2021). Correlation Between Joint Position Sense, Threshold To Detection of Passive Motion of The Knee Joint And Walking Speed of Post-Stroke Patient. International Journal of Research Publications, 83(1). [CrossRef]

- Mizuta, N., Hasui, N., Nakatani, T., Takamura, Y., Fujii, S., Tsutsumi, M., Taguchi, J., & Morioka, S. (2020). Walking characteristics including mild motor paralysis and slow walking speed in post-stroke patients. Scientific Reports, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Odetunde, M. O., Makinde, A. F., Jimoh, O. M., Mbada, C. E., Niyi-Odumosu, F., & Fatoye, F. (2025). Physical activity, fatigue severity, and health-related quality of life of community-dwelling stroke survivors: a cross-sectional study. Bulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy, 30(1). [CrossRef]

- Balbinot, G., Schuch, C. P., Oliveira, H. B., & Peyré-Tartaruga, L. A. (2020). Mechanical and energetic determinants of impaired gait following stroke: segmental work and pendular energy transduction during treadmill walking. Biology Open, 9(7). [CrossRef]

- Fulk, G. D., He, Y., Boyne, P., & Dunning, K. (2017). Predicting Home and Community Walking Activity Poststroke. Stroke, 48(2), 406–411. [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J. A. M., Oliveira, S. G., di Thommazo-Luporini, L., Phillips, S. A., Catai, A. M., Borghi-Silva, A., Ribeiro, J. A. M., Oliveira, S. G., di Thommazo-Luporini, L., Monteiro, C. I., Phillips, S. A., Catai, A. M., Borghi-Silva, A., & Russo, T. L. (2019). Energy Cost During the 6-Minute Walk Test and Its Relationship to Real-World Walking After Stroke: A Correlational, Cross-Sectional Pilot Study. https://academic.oup.com/ptj.

- Ardestani, M. M., Kinnaird, C. R., Henderson, C. E., & Hornby, T. G. (2019). Compensation or Recovery? Altered Kinetics and Neuromuscular Synergies Following High-Intensity Stepping Training Poststroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 33(1), 47–58. [CrossRef]

- Kerrigan, D. Casey, Frates, Elizabeth P, Rogan, Shannon BS; Riley, Patrick O.(2000). Hip Hiking and Circumduction Quantitative Definitions. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 79 (3) 247-252.

- Chen, G., Patten, C., Kothari, D. H., & Zajac, F. E. (2005). Gait differences between individuals with post-stroke hemiparesis and non-disabled controls at matched speeds. Gait and Posture, 22(1), 51–56. [CrossRef]

- Awad, L. N., Bae, J., Kudzia, P., Long, A., Hendron, K., Holt, K. G., OʼDonnell, K., Ellis, T. D., & Walsh, C. J. (2017). Reducing Circumduction and Hip Hiking During Hemiparetic Walking Through Targeted Assistance of the Paretic Limb Using a Soft Robotic Exosuit. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation, 96(10), S157–S164. [CrossRef]

- Mahtani, G. B., Kinnaird, C. R., Connolly, M., Holleran, C. L., Hennessy, P. W., Woodward, J., Brazg, G., Roth, E. J., & Hornby, T. G. (2017). Altered Sagittal-and Frontal-Plane Kinematics Following High-Intensity Stepping Training Versus Conventional Interventions in Subacute Stroke Background. Common locomotor deficits observed in people poststroke include. In Original Research (Vol. 320). https://academic.oup.com/ptj.

- Zissimopoulos, A., Fatone, S., & Gard, S. (2015). Effects of ankle-foot orthoses on mediolateral foot-placement ability during post-stroke gait. Prosthetics and Orthotics International, 39(5), 372–379. [CrossRef]

- Akbas, T., Neptune, R. R., & Sulzer, J. (2019). Neuromusculoskeletal simulation reveals abnormal rectus femoris-gluteus medius coupling in post-stroke gait. Frontiers in Neurology, 10(APR). [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, V. A., Knarr, B. A., Reisman, D. S., & Higginson, J. S. (2014). Frontal plane compensatory strategies associated with self-selected walking speed in individuals post-stroke. Clinical Biomechanics, 29(5), 518–522. [CrossRef]

- Akbas, T., Prajapati, S., Ziemnicki, D., Tamma, P., Gross, S., & Sulzer, J. (2019). Hip circumduction is not a compensation for reduced knee flexion angle during gait. Journal of Biomechanics, 87, 150–156. [CrossRef]

- Tamaya, V. C., Wim, S., Herssens, N., van de Walle, P., Willem, D. H., Steven, T., & Ann, H. (2020). Trunk biomechanics during walking after sub-acute stroke and its relation to lower limb impairments. Clinical Biomechanics, 75. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J., Seamon, B. A., Lee, R. K., Kautz, S. A., Neptune, R. R., & Sulzer, J. S. (2025). Post-stroke Stiff-Knee gait: are there different types or different severity levels? Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Akbas, T., Kim, K., Doyle, K., Manella, K., Lee, R., Spicer, P., Knikou, M., & Sulzer, J. (2020). Rectus femoris hyperreflexia contributes to Stiff-Knee gait after stroke. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 17(1). [CrossRef]

- Han, X., Guffanti, D., & Brunete, A. (2025). A Comprehensive Review of Vision-Based Sensor Systems for Human Gait Analysis. In Sensors (Vol. 25, Issue 2). Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- Microsoft. Available online:https://www.microsoft.com/ja-JP/d/azure-kinect-dk/8pp5vxmd9nhq?activetab=pivot:%E6%A6%82%E8%A6%81tab (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Bawa, A., Banitsas, K., & Abbod, M. (2021). A Review on the Use of Microsoft Kinect for Gait Abnormality and Postural Disorder Assessment. Journal of Healthcare Engineering, 2021, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Sugai, R., Maeda, S., Shibuya, R., Sekiguchi, Y., Izumi, S. I., Hayashibe, M., & Owaki, D. (2023). LSTM Network-Based Estimation of Ground Reaction Forces during Walking in Stroke Patients Using Markerless Motion Capture System. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics, 5(4), 1016–1024. [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [CrossRef]

- Eltoukhy, M., Oh, J., Kuenze, C., & Signorile, J. (2017). Improved kinect-based spatiotemporal and kinematic treadmill gait assessment. Gait and Posture, 51, 77–83. [CrossRef]

- Eltoukhy, M., Kuenze, C., Oh, J., Jacopetti, M., Wooten, S., & Signorile, J. (2017). Microsoft Kinect can distinguish differences in over-ground gait between older persons with and without Parkinson’s disease. Medical Engineering and Physics, 44, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Shibuya, R. (2023). Verification of the reliability of gait data for patients with hemiparesis measured by a depth sensor [Unpublished master's thesis]. Department of Disability Science, Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University.

- Kazuhisa Domen (1995) Consistency and validity of the Stroke Impairment Assessment Set (SIAS) in hemiplegic stroke patients (1) -Motor function, muscle tone, tendon reflexes, and healthy side function on the paretic side Rehabilitation Medicine, 32(2), 113-122.

- Sonoda, Shigeru (1995) Consistency and validity of the Stroke Impairment Assessment Set (SIAS) for functional assessment of hemiplegic stroke patients (2) - Trunk, higher brain function, sensory items and outcome prediction Rehabilitation Medicine, 32(2), 123-132.

- Yeh, T. ting, Chang, K. chou, & Wu, C. yi. (2019). The Active Ingredient of Cognitive Restoration: A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Sequential Combination of Aerobic Exercise and Computer-Based Cognitive Training in Stroke Survivors With Cognitive Decline. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(5), 821–827. [CrossRef]

- Kharazi, M. R., Memari, A. H., Shahrokhi, A., Nabavi, H., Khorami, S., Rasooli, A. H., Barnamei, H. R., Jamshidian, A. R., & Mirbagheri, M. M. (2016). Validity of microsoft kinectTM for measuring gait parameters. 2015 22nd Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering, ICBME 2015, 375–379. [CrossRef]

- Tölgyessy, M., Dekan, M., Chovanec, Ľ., & Hubinský, P. (2021). Evaluation of the azure kinect and its comparison to kinect v1 and kinect v2. Sensors (Switzerland), 21(2), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- J. Zeni, J. Richards, J. Higginson, Two simple methods for determining gait events during treadmill and overground walking using kinematic data, Gait Posture 27 (2008) 710–714.

- Rose, J., Gamble, J.G., 2006. Human walking. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp. 33–51.

- Kinsella, S., & Moran, K. (2008). Gait pattern categorization of stroke participants with equinus deformity of the foot. Gait and Posture, 27(1), 144–151. [CrossRef]

- Chan, Y. H. (2003). Biostatistics 104: Correlational analysis. Singapore Medical Journal, 44(12), 614–619.

- Dean, J. C., Embry, A. E., Stimpson, K. H., Perry, L. A., & Kautz, S. A. (2017). Effects of hip abduction and adduction accuracy on post-stroke gait. Clinical Biomechanics, 44, 14–20. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Mukaino, M., Ohtsuka, K., Otaka, Y., Tanikawa, H., Matsuda, F., Tsuchiyama, K., Yamada, J., & Saitoh, E. (2020). Gait characteristics of post-stroke hemiparetic patients with different walking speeds. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research, 43(1), 69–75. [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, K., Kawakami, M., Okada, K., Okuyama, K., Tsuzuki, K., & Liu, M. (2021). Pelvis-toe distance: 3-dimensional gait characteristics of functional limb shortening in hemiparetic stroke. Sensors, 21(16). [CrossRef]

- Little, V. L., McGuirk, T. E., Perry, L. A., & Patten, C. (2018). Pelvic excursion during walking post-stroke: A novel classification system. Gait and Posture, 62, 395–404. [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G., van Peppen, R., Wagenaar, R. C., Dauphinee, S. W., Richards, C., Ashburn, A., Miller, K., Lincoln, N., Partridge, C., Wellwood, I., & Langhorne, P. (2004). Effects of augmented exercise therapy time after stroke: A meta-analysis. Stroke, 35(11), 2529–2536. [CrossRef]

- Patterson, K. K., Parafianowicz, I., Danells, C. J., Closson, V., Verrier, M. C., Staines, W. R., Black, S. E., & McIlroy, W. E. (2008). Gait Asymmetry in Community-Ambulating Stroke Survivors. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 89(2), 304–310. [CrossRef]

- Mizuike, C., Ohgi, S., & Morita, S. (2009). Analysis of stroke patient walking dynamics using a tri-axial accelerometer. Gait & Posture, 30(1), 60–64. [CrossRef]

- Kettlety, S. A., Finley, J. M., Reisman, D. S., Schweighofer, N., & Leech, K. A. (2023). Speed-dependent biomechanical changes vary across individual gait metrics post-stroke relative to neurotypical adults. Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, 20(1). [CrossRef]

- Awad, L. N., Palmer, J. A., Pohlig, R. T., Binder-Macleod, S. A., & Reisman, D. S. (2015). Walking speed and step length asymmetry modify the energy cost of walking after stroke. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair, 29(5), 416–423. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, C. K., Bowden, M. G., Neptune, R. R., & Kautz, S. A. (2007). Relationship Between Step Length Asymmetry and Walking Performance in Subjects With Chronic Hemiparesis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 88(1), 43–49. [CrossRef]

- Awad, L. N., Lewek, M. D., Kesar, T. M., Franz, J. R., & Bowden, M. G. (2020). These legs were made for propulsion: advancing the diagnosis and treatment of post-stroke propulsion deficits. In Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation (Vol. 17, Issue 1). BioMed Central Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Little, V. L., McGuirk, T. E., & Patten, C. (2014). Impaired Limb Shortening following Stroke: What’s in a Name? PLoS ONE, 9(10), e110140. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, N., Acosta, A. M., López-Rosado, R., & Dewald, J. P. A. (2018). Neural constraints affect the ability to generate hip abduction torques when combined with hip extension or ankle plantarflexion in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Frontiers in Neurology, 9(JUL). [CrossRef]

- Hinton, E. H., Bierner, S., Reisman, D. S., Likens, A., & Knarr, B. A. (2024). Paretic propulsion changes with handrail Use in individuals post-stroke. Heliyon, 10(5). [CrossRef]

| Stroke patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male/female) a | 17/5 | ||||

| Age (year)b | 66.05 | (15.44) | |||

| Height (m)b | 1.65 | (0.08) | |||

| Weight (kg)b | 68.43 | (15.43) | |||

| Diagnosis (Hemorrhage/Infarction) a | 5/17 | ||||

| Paretic side (left/right) a | 14/8 | ||||

| Time since onset (days)b | 8.77 | (5.27) | |||

| Physical therapy time during longitudinal period (minutes) |

25.72 | (7.68) | |||

| a Number of people | |||||

| b Mean (Standard deviation) | |||||

| Spatiotemporal parameters | Initial assessment | Second assessment | Effect size | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gait speed (m/sec) a | 0.38 | (0.16) | 0.53 | 0.18 | -1.181 | < 0.001 | |||

| Gait cycle time (sec)a | 1.99 | (0.68) | 1.60 | 0.42 | 0.882 | < 0.001 | |||

| Double stance time (sec)b | 0.49 | (0.23) | 0.35 | 0.18 | 0.878 | < 0.001 | |||

| Paretic stance time (sec)a | 1.44 | (0.54) | 1.10 | 0.34 | -0.792 | < 0.001 | |||

| Paretic swing time (sec)b | 0.53 | (0.16) | 0.48 | 0.11 | -0.415 | 0.051 | |||

| Non-paretic swing time (sec)b | 0.45 | (0.08) | 0.42 | 0.05 | -0.391 | 0.067 | |||

| Stride length on the paretic side (m)a | 0.66 | (0.15) | 0.78 | 0.14 | -1.081 | < 0.001 | |||

| Step length on the paretic side (m)a | 0.31 | (0.08) | 0.36 | 0.07 | -0.720 | 0.003 | |||

| Step length on the non-paretic side (m)a | 0.29 | (0.08) | 0.35 | 0.08 | -1.022 | < 0.001 | |||

| Step width (m)a | 0.13 | (0.03) | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.2999 | 0.174 | |||

| Paretic femoral abduction angle (°) a | 6.71 | (3.78) | 5.79 | 3.47 | 0.513 | 0.049 | |||

| Paretic pelvic hike angle (°) a | 3.82 | (2.34) | 2.90 | 2.35 | 0.513 | 0.025 | |||

| H1 (°) b | 23.18 | (5.67) | 23.93 | 4.30 | -0.174 | 0.424 | |||

| H2 (°) a | 23.20 | (5.40) | 24.02 | 4.29 | -0.197 | 0.367 | |||

| H3 (°) a | -3.89 | (6.17) | -5.91 | 5.13 | 0.417 | 0.064 | |||

| H4 (°) a | 5.52 | (7.12) | 4.69 | 5.76 | 0.139 | 0.521 | |||

| H5 (°) a | 24.28 | (6.79) | 25.55 | 5.49 | -0.245 | 0.263 | |||

| H6 (°) a | 29.59 | (5.42) | 32.32 | 5.43 | -0.469 | 0.039 | |||

| K1 (°) a | 9.93 | (5.16) | 8.58 | 5.23 | 0.342 | 0.124 | |||

| K2 (°) a | 15.15 | (4.80) | 15.09 | 6.20 | 0.010 | 0.963 | |||

| K3 (°) a | 5.65 | (3.16) | 5.96 | 4.40 | -0.132 | 0.543 | |||

| K4 (°) a | 35.24 | (10.95) | 37.74 | 8.89 | -0.358 | 0.108 | |||

| K5 (°) a | 46.65 | (11.67) | 50.87 | 10.82 | -0.513 | 0.026 | |||

| K6 (°) a | 41.82 | (10.73) | 45.84 | 9.77 | -0.479 | 0.036 | |||

| Mean (Standard deviation) a Paired t-test (p < 0.05) b Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < 0.05) | |||||||||

| SIAS evaluation items | First assessment | Second assessment | Effect size | p-value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hip joint (0/1/2/3/4/5) a | 1/0/6/7/8/0 | (4-2) | 0/0/3/3/9/7 | (5-3.25) | -0.82 | < 0.001 | |||

| Knee joint (0/1/2/3/4/5) a | 1/1/3/5/9/3 | (4-3) | 0/0/2/5/8/7 | (5-3) | -0.58 | 0.006 | |||

| Ankle joint (0/1/2/3/4/5) a | 2/2/5/4/5/4 | (4-2) | 1/3/0/3/6/9 | (5-3) | -0.74 | < 0.001 | |||

| L/E Deep tendon reflex (0/1/2/3) a | 2/13/6/1 | (2-1) | 3/6/11/2 | (2-1) | -0.30 | 0.153 | |||

| L/E muscle tone (0/1/2/3) a | 0/4/10/8 | (3-2) | 0/2/9/11 | (3-2) | -0.30 | 0.160 | |||

| Superficial sensation (0/1/2/3) a | 2/0/2/18 | (3-3) | 0/2/1/19 | (3-3) | -0.37 | 0.083 | |||

| Deep sensation (0/1/2/3) a | 2/0/2/18 | (3-3) | 0/2/0/20 | (3-3) | -0.42 | 0.046 | |||

| Ankle joint range of motion (0/1/2/3) a | 0/0/13/9 | (3-2) | 0/0/10/12 | (3-2) | -0.21 | 0.317 | |||

| Abdominal strength (0/1/2/3) a | 8/7/6/3 | (2-0) | 0/5/8/9 | (3-2) | -0.66 | 0.002 | |||

| SIAS: Stroke impairment assessment set (Interquartile range) L/E: Lower extremity a Wilcoxon signed-rank test (p < 0.05) | |||||||||

| Spatiotemporal and kinematic variables | Mean (SD) | Paretic side femoral abduction angle |

Paretic side pelvic hike angle |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | p-value | Correlation | p-value | |||||||

| Gait speed Δ (m/sec) a | 0.15 | (0.13) | 0.09 | 0.701 | 0.03 | 0.886 | ||||

| Gait cycle time Δ (sec)b | -0.39 | (0.44) | -0.05 | 0.809 | 0.23 | 0.299 | ||||

| Double stance time Δ (sec)a | -0.14 | (0.16) | -0.24 | 0.290 | 0.12 | 0.609 | ||||

| Paretic stance time Δ (sec)b | -0.34 | (0.34) | -0.19 | 0.393 | 0.10 | 0.661 | ||||

| Paretic swing time Δ (sec)b | -0.05 | (0.13) | 0.32 | 0.148 | 0.41 | 0.058 | ||||

| Non-paretic swing time Δ (sec)b | -0.03 | (0.07) | -0.18 | 0.428 | -0.05 | 0.828 | ||||

| Paretic stride length Δ (m)a | 0.12 | (0.11) | 0.03 | 0.881 | 0.00 | 0.996 | ||||

| Paretic step length Δ (m)a | 0.04 | (0.06) | -0.03 | 0.892 | 0.15 | 0.517 | ||||

| Non-paretic step length Δ (m)a | 0.05 | (0.05) | 0.12 | 0.586 | -0.02 | 0.935 | ||||

| Step width Δ (m) a | -0.01 | (0.03) | -0.22 | 0.332 | 0.12 | 0.604 | ||||

| Paretic pelvic hike Δ (°) a | -0.91 | (1.74) | 0.55 | 0.008 | - | - | ||||

| H1Δ (°) b | 0.75 | (4.33) | -0.31 | 0.154 | -0.32 | 0.148 | ||||

| H2Δ (°) a | 0.83 | (4.20) | -0.34 | 0.118 | -0.27 | 0.221 | ||||

| H3Δ (°) a | -2.02 | (4.84) | -0.03 | 0.886 | -0.14 | 0.545 | ||||

| H4Δ (°) a | -0.83 | (5.99) | 0.02 | 0.938 | -0.14 | 0.540 | ||||

| H5Δ (°) a | 1.27 | (5.19) | -0.13 | 0.557 | -0.13 | 0.557 | ||||

| H6Δ (°) a | 2.73 | (5.82) | -0.09 | 0.679 | 0.02 | 0.936 | ||||

| K1Δ (°) a | -1.35 | (3.94) | -0.09 | 0.690 | -0.25 | 0.271 | ||||

| K2Δ (°) a | -0.06 | (5.98) | -0.23 | 0.311 | -0.13 | 0.569 | ||||

| K3Δ (°) a | 0.31 | (2.38) | -0.36 | 0.096 | -0.22 | 0.324 | ||||

| K4Δ (°) a | 2.49 | (6.96) | 0.26 | 0.247 | 0.03 | 0.894 | ||||

| K5Δ (°) a | 4.22 | (8.24) | 0.10 | 0.660 | 0.09 | 0.700 | ||||

| K6Δ (°) a | 4.02 | (8.40) | 0.19 | 0.388 | 0.13 | 0.573 | ||||

| SD: Standard deviation a Pearson's correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) b Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) | ||||||||||

| SIAS evaluation items | Median (IQR) |

Paretic side femoral abduction angle |

Paretic side pelvic hike angle |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation | p-value | Correlation | p-value | |||||||

| Hip joint Δ b | 1 | (1-1) | 0.42 | 0.050 | -0.20 | 0.371 | ||||

| Knee joint Δ b | 0 | (1-0) | -0.28 | 0.203 | -0.43 | 0.046 | ||||

| Ankle joint Δ b | 1 | (1-0) | -0.49 | 0.021 | -0.01 | 0.962 | ||||

| L/E deep tendon reflex Δ b | 0 | (1-0) | -0.34 | 0.121 | -0.13 | 0.566 | ||||

| L/E muscle tone Δ b | 0 | (0.00) | 0.01 | 0.969 | -0.31 | 0.161 | ||||

| L/E superficial sensation Δ b | 0 | (0.00) | -0.16 | 0.487 | -0.03 | 0.888 | ||||

| L/E deep sensation Δ b | 0 | (0.00) | 0.02 | 0.935 | 0.13 | 0.559 | ||||

| Ankle joint range of motion Δ b | 0 | (0.75-0) | 0.32 | 0.149 | 0.09 | 0.681 | ||||

| Abdominal strength Δ b | 1 | (1.75-0) | -0.11 | 0.614 | -0.20 | 0.365 | ||||

| IQR: Interquartile range L/E: Lower extremity b Spearman's rank correlation coefficient (p < 0.05) | ||||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).