1. Introduction

Stroke is the second most common cause of death after ischemic heart disease and the second leading cause of disability globally [

1]. The Global Burden of Disease Study [

1] estimated that in 2016, 80.1 million people were living with stroke worldwide (95% uncertainty interval [UI] 74.1–86.3), of whom 13.7 million (95% UI 12.7–14.7) suffered a first-ever stroke. Stroke, mostly of ischemic type (84%; 95% UI 82.1–86.4), was diagnosed in 41.1 million women (95% UI 38.0–44.3) and 39.0 million men (95% UI 36.1–42.1). According to the Study’s stroke mortality statistics, 5.5 million people (95% UI 5.3–5.7) died of a stroke in 2016, and 116.4 million (95% UI 111.4–121.4) became disabled as a result of acute or chronic stroke [

1]. Between 1990 and 2013, the global number of strokes and stroke-related deaths and disabilities among individuals aged 20-64 years increased significantly by 1.4–1.8 times for ischemic strokes and 1.2–1.9 times for hemorrhagic strokes [

2].

After a systematic review of clinical trials, Steward et al.[

3] pointed to physical activity as a vital element of stroke prevention and treatment. Physical exercise reduces the effects of neurological damage and stimulates brain plasticity in stroke survivors, with the greatest improvement in motor function occurring in the early post-stroke phase. In the chronic phase (six months after a stroke and later), many patients reach a plateau or experience slower motor recovery, which dispirits them and causes that they withdraw from physiotherapy [

4,

5], Studies show, however, that regular physical exercise can offer significant health improvements even months after stroke [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], also in patients who have reached a recovery plateau [

6]. This means that patients in the late post-stroke period should not be excluded from training programs based on physical exercises that require learning new tasks, engage conscious attention, and stimulate cognitive functions [

13].

The most common consequences of stroke are postural balance, control, and gait impairments. France by De Peretti et al. [

14] reported balance disorders in 50% of post-stroke patients. Three months after stroke, gait disorders still affect 60% of patients, with 20% of whom need wheelchairs to move around [

15,

16,

17]. The distance that an adult who suffered an acute or subacute stroke can cover is 40–50% shorter than that a healthy adult can walk [

18]. De Haart et al. [

19] found abnormal postural control to be one of the main causes of post-stroke mobility impairment. Pohl et al. [

18] concluded that balance improvement was the strongest predictor of gait distance that patients could walk three months after stroke.

Post-stroke patients show many changes in motor strategies for postural control, among which body weight asymmetry, delayed and reduced anticipatory postural adjustments, synergistic muscle coactivation, and abnormal postural tilt are the most common. The majority of the changes are related to the impaired central nervous system, but some appear to be adaptive compartments [

20]. Lamb et al. [

21] concluded that postural and balance impairments are the strongest predictors of falls in stroke survivors, and Belgen et al. [

22] reported that individuals who had experienced falls were more fearful of falling in the chronic post-stroke phase (relative risk [RR]=2.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–4.9) and show lower falls-related self-efficacy (p=0.04) and more depressive symptoms (p=0.02) than those who had not fallen. Evidence has also been presented that individuals with a history of multiple falls have poorer balance (p=0.02), greater fear of falling (RR=5.6; 95% CI, 1.3–23), and use more medications (p=0.04) than non- or one-time fallers [

22]. Falls are a major cause of injuries leading to disability, social isolation, and reduced quality of life [

23]. People who fear falling tend to limit their daily activity and adopt a sedentary lifestyle, which further increases their risk of falling, dependence on others, and disability [

24].

For the above reasons, exercises that improve balance and gait quality play a significant role in stroke rehabilitation [

13]. To evaluate the ability of different types of exercise to improve balance in chronic stroke survivors, Van Duijnhoven et al. [

25] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 43 randomized clinical trials (RCTs) of moderate or high methodological quality (PEDro score ≥4) involving a total of 1.613 patients. The authors of most of the studies (n=28) assessed participants’ postural balance using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS). Subgroup analyses of studies that reported BBS outcomes showed that only balance and weight-shifting training (3.75 points, +6.7%; 95% CI, 1.71–5.78; p<0.01; I²=52%) and gait training (2.26 points, +4.0%; 95% CI, 0.94–3.58; p<0.01; I²=21%) had a significant and positive effect on postural balance.

Programs to rehabilitate balance and gait quality in chronic stroke survivors use various approaches utilizing modern technologies, including treadmill training [

10,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31]. Treadmill exercises, especially those performed without body weight support (BWS) [

10,

31], are significantly more effective in improving gait speed [

10,

31] and step length and width [

31] than overground training.

Perturbation-based balance training (PBT), which has in recent years been introduced as a therapy for balance and gait impairments of various origins, is usually performed using equipment inducing changes in ground surface compliance [

32,

33,

34] or moveable floor platforms [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Also used are treadmills [

30,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] where balance disturbances are induced by two independently moving belts [

48], belt accelerations or decelerations [

30,

41,

43,

45,

46] and forward-backward as well as lateral belt translations [

44]. A systematic review of 8 RCTs by Mansfield et al. [

49] found patients who completed the PBT to have a lower risk of falling (overall risk ratio 0.71, 95% CI 0.52–0.96, p=0.02) and to report fewer falls than controls who did not perform PBT (overall rate ratio 0.54, 95% CI 0.34–0.85, p=0.007). The RCTs involved 404 adults, including healthy and frail older adults (>60 years) and adults with Parkinson's disease.

To the authors' knowledge, there are only 4 RCTs [

40,

44,

45,

50] with chronic stroke patients performing PBT. In two of them, authored by Esmaeili et al. [

45] and Hu et al. [

44], participants had 9 [

45] and 20 [

44] training sessions spanning 3 [

45] and 4 [

44] weeks, respectively. In Esmaeili et al. [

45], balance perturbations were induced by accelerating and decelerating the treadmill belt, while Hu et al. [

44] also used lateral belt translations. The studies produced inconsistent results. Esmaeili et al. [

45] reported that PBT improved participants’ dynamic balance but not gait speed, whereas Hu et al. [

44] observed improvement in gait speed but not found in dynamic balance. The authors of the other two RCTs [

40,

50] used moveable floor platforms [

50] and applied changes in ground surface compliance [

40]. Based on the outcomes of a single PBT session, the authors of one of the studies [

40] concluded that PBT offered protection from falling by helping develop adaptive responses. The second study was a pilot RCT with only 12 patients, who were equally divided between two groups. After 20 PBT sessions performed over 4 weeks, its authors observed improvement in participants’ dynamic balance and gait speed. Three clinical studies [

46,

47,

51] where chronic stroke patients performed PBT did not have control groups. The studies only recruited 10 [

51] and 12 [

46,

47] patients who performed 3 [

46], 10 [

51], and 15 [

47] training sessions, respectively. All three studies reported improvements in participants’ gait speed [

47,

51] and gait quality [

46,

51].

The cited studies indicate that PBT, including involving the use of a treadmill, is capable of improving balance and gait quality in chronic stroke patients. However, given that RCTs of this type are few and their results are inconsistent due to the variety of training methods used by their authors, more RCTs are needed to ascertain the most appropriate training methods and their ability to influence balance and gait quality in chronic stroke patients.

This RCT was designed to determine whether, and to what extent, treadmill perturbation-based balance training (TPBT) improves balance and gait quality and reduces fear of falling in chronic stroke patients. It also sought to establish whether the effect of TPBT on these parameters would be comparable or greater than in the case of overground gait and balance training.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Trial Design

This prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial was designed to compare body balance, gait quality, and fear of falling in chronic stroke patients divided into two parallel groups that participated in conventional stroke rehabilitation enhanced by treadmill perturbation-based training (TPBT; the Experimental Group, EG), and in conventional stroke rehabilitation supplemented by traditional overground gait and balance training (the Control Group, CG). The trial adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Bioethics Committee for Scientific Research at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland (Resolution No. 5/2020). It was prospectively registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number Registry: ISRCTN17138124.

2.2. Funding

The trial was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund for the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship (Poland; No. RPKK.01.02.01-04-0016/18).

2.3. Setting and Participants

All participants were under the care of the same single medical and rehabilitation center. They were recruited for the study based on the following eligibility criteria: age ≥18 years; first-ever ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke occurring ≥6 months prior; independent ambulation over 10 meters (assistive devices such as a cane or walker permitted); minimum gait speed of 0.4 km/h; spasticity of the affected lower limb graded between 0 and 2 on the Modified Ashworth Spasticity Scale; Brunnström Recovery Scale stages III–VI for the lower limb; and written informed consent to participate.

Excluded from the trial were patients who suffered more than one stroke; with contraindications to physical exercise or subarachnoid hemorrhage; unable to comprehend verbal instructions; with a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≤24 and a Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) score ≥20; affected by severe aphasia impeding communication (assessed by a speech therapist); with hemianopsia or hemineglect; with stroke onset <6 months prior; with complete hip joint ankylosis; with lower limb length discrepancy exceeding 3 cm; presenting with cardiopulmonary insufficiency precluding walking more than 10 meters or conditions affecting gait and balance other than related to stroke (central or peripheral nervous system disorders, fractures of the spine or limbs within the past year, osteoporosis, acute inflammatory diseases of internal organs or the musculoskeletal system, limb amputations, vision impairments, malignancies under treatment, post-chemotherapy neuropathies, diabetic neuropathy, etc.).

All participants completed outpatient and inpatient rehabilitation programs prior to enrollment in the trial, which was part of a broader rehabilitation plan. Their demographic data were collected through standard interviews, physical examinations, and a review of their medical records.

2.4. Randomization

A person unrelated to the trial received 50 slips of paper, 25 of which were marked with "A" (CG) and the other 25 with "B" (EG), and placed each slip in one of 50 envelopes according to a randomized computer-generated sequence. After sealing, the envelopes were delivered to the research manager, who opened them in the presence of a physiotherapist to randomly assign willing and consenting patients (or those who had consenting legal guardians) to either group.

2.5. Blinding

Both the physiotherapist who performed initial and final clinical assessments of the participants and the statistician in charge of data analysis were blinded to group assignments

2.6. Intervention. Post-Stroke Therapy Administered To Both Groups

All patients participated in a 3-week rehabilitation program based on conventional post-stroke therapy. Sessions of 2.5 hours, designed according to the best clinical practices, were delivered Monday through Saturday. The exercises they included aimed to improve participants’ movement patterns and normalize their muscle tone.

2.7. Treadmill Training in the EG

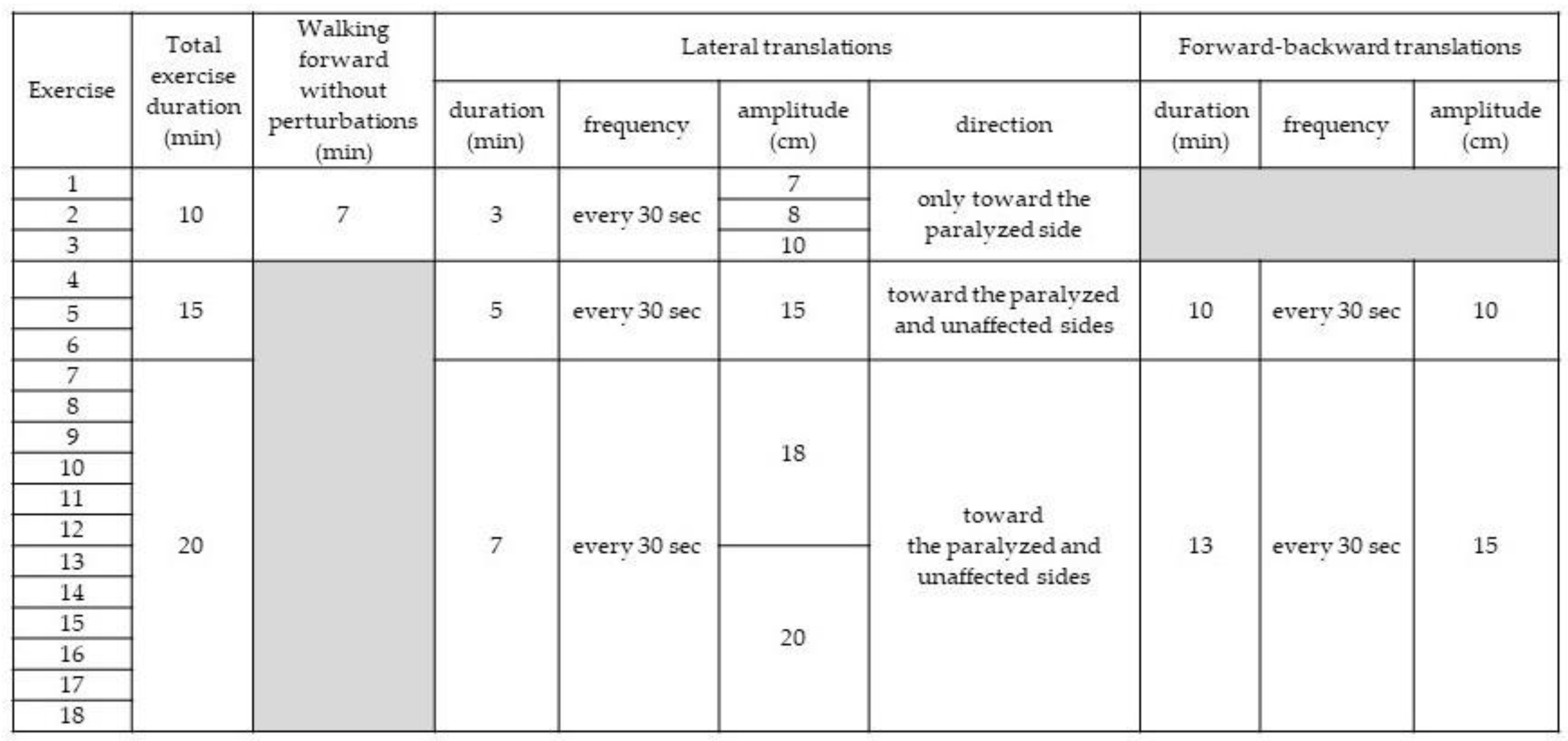

In addition to receiving conventional therapy, participants in the EG exercised on a treadmill (Balance Tutor; MediTouch, Ltd.; Israel) controlled by software capable of inducing postural perturbations in the frontal and sagittal planes during walking. A harness connected to an overhead support system protected exercising patients from falling without supporting their body weight. Handrail use was prohibited. Sessions were performed daily for 3 weeks, also Monday through Saturday. The treadmill speed was always set according to patient preference and recorded. Exercise duration and difficulty were progressively increased (

Table 1).

2.8. Conventional Gait and Balance Training in the CG

The purpose of this training was to improve participants’ performance of functional tasks, such as standing under various conditions (with reduced sensory input, narrowed base of support, while reaching for and catching objects, responding to unexpected manual perturbations), sit-to-stand transfers, multidirectional stepping, overground walking, and walking up and down stairs. Emphasis was placed on stability and normal weight-bearing patterns during training tasks. The use of assistive devices was permitted if needed. Participants were encouraged to use postural control and movement strategies they developed in daily living. The length of sessions was progressively increased to match the duration of sessions in the EG: 10 minutes on days 1–3, 15 minutes on days 4–6, and 20 minutes between day 7 and day 18.

2.10. Measures

Clinical assessments of participants were performed twice, on the day preceding the 3-week rehabilitation program and on the first day after it ended. Their cognitive function was determined pre-intervention using the MMSE [

52], and depressive symptoms were assessed with the GDS [

53]. Motor function and the stages of lower limb recovery were measured using the Brunnström Recovery Scale [

19,

54], spasticity severity was evaluated with the Modified Ashworth Scale [

55,

56], and independence in activities of daily living was established using the 100-point Barthel Index [

57].

Participants’ static and dynamic body balance, gait quality, and fear of falling were assessed pre- and post-intervention. Balance measurements were performed using functional tests: the BBS for static and dynamic balance [

58], the Functional Reach Test (FRT) for dynamic balance [

59], and the Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test for dynamic balance [

60]. The BBS is a 14-item objective tool with excellent interrater reliability (ICC=0.97) and intrarater reliability (ICC=0.98) for chronic stroke patients [

61]. It also has an adequate ability to predict fall occurrence (area under the curve [AUC] [95% CI]=0.813 [0.691–0.936], sensitivity=75%, and specificity=76.9%) [

63]. The FRT assesses dynamic balance in simple tasks and has intersubject reliability of 0.987 (0.983–0.992) and intrasubject reliability of 0.983 (0.979–0.989) for stroke patients [

64]. The TUG Test that evaluates mobility, balance, walking ability, and fall risk in older adults has excellent test-retest reliability (ICC=0.96) for chronic stroke patients [

65]. Its results show a high correlation (r=0.86–0.92) with the results of other mobility, balance, exercise tolerance, and fall risk tests, such as the Comfortable Gait Speed Test, Fast Gait Speed Test, Stair Climbing Test, and 6-Minute Walk Test [

65].

Participants’ static balance was additionally assessed using a stabilometric platform (Zebris FDM, Germany), which recorded forces and torques at a sampling rate of 80 Hz. During measurements, participants stood quietly for 60 seconds with eyes open, feet shoulder-width apart, and arms at their sides. Gait speed was assessed with the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) [

66], which measures walking speed over a short distance in meters per second. The test has excellent test-retest reliability

(ICC]=0.95–0.99) [

67] for chronic stroke patients, as well as excellent reliability for both comfortable (ICC=0.94) and fast (ICC=0.97) gait speeds [

65]. The 10MWT has also been demonstrated to have high predictive validity and excellent correlation with dependence in instrumental activities of daily living (r=0.76) and the Barthel Index (r=0.78) [

68]. Spatiotemporal gait parameters were also evaluated on a treadmill (Zebris FDM-T; Rehawalk, MaxxusDaum h/p Cosmos Force). For patients to be able to find a comfortable walking speed, they walked on the treadmill to try it before the test; during this trial, the belt speed was decreased and increased twice. A 30-second measurement was taken and its result was included in the analysis.

Participants’ fear of falling was assessed using the 16-item Falls Efficacy Scale–International (FES-I) [

69,

70], which showed excellent internal consistency (cronbach’s α=0.96) and test–retest reliability (ICC=0.96) in a group of 704 seniors aged 60-95 years at risk of falls. Its high validity and reliability have also been confirmed by a study on individuals with neurological disorders, including vestibular disorders (ICC=0.94) [

71] and Parkinson's disease (ICC=0.91 to 0.94) [

72].

2.11. Outcomes. Primary Outcomes

Primary outcomes of the trial included static and dynamic body balance and gait speed, which were measured at baseline and after 3 weeks of the rehabilitation program using the BBS and the 10MWT, respectively.

2.12. Secondary Outcomes

Secondary outcomes included dynamic body balance assessed by the TUG Test and the FRT; static body balance assessed on a stabilometric platform (Zebris FDM-T; Rehawalk, MaxxusDaum h/p Cosmos Force); gait quality assessed by a walking test on a treadmill (Zebris FDM-T; Rehawalk, MaxxusDaum h/p Cosmos Force); and fear of falling assessed using the FES-I questionnaire. These tests, too, were conducted at baseline and after 3 weeks of rehabilitation.

2.13. Statistical Analysis. Sample Size Calculation

To determine the appropriate sample size for the EG and CG, a pilot study was conducted with 12 chronic post-stroke patients, randomized to receive either perturbation-based treadmill training (EG) or conventional overground gait and balance training (CG) according to clinical guidelines. Body balance and gait speed over 10 meters were measured after three weeks of intervention using the BBS and 10MWT, respectively. Given the unimodal distribution of scores and skewness and kurtosis values below 2.5, the arithmetic mean and standard deviation were used to describe central tendency and dispersion. For the sample size calculation, the significance level (Type I error) was set at α = 0.05 and the Type II error at β = 0.1 (power = 0.90). A minimum clinically important difference (MCID) of 25% between pre- and post-intervention values was assumed. Based on these outcomes and Student’s t-distribution, each group required at least 23 participants. To account for potential dropouts, two additional participants per group were recruited, resulting in a final sample size of 25 per group.

2.14. Intention-to-Treat Analysis

All 50 randomized patients were included in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. For participants who did not complete the intervention, missing data were imputed using linear regression based on prior assessments and clinical similarity, according to the formula: y=a·x+b, where a is the regression coefficient and b is the intercept. This approach assumed a linear trend in the variables under study. The impact of imputation was evaluated by sensitivity analysis comparing ITT and per-protocol outcomes; the absence of statistically significant differences indicated that imputation did not materially affect the trial’s results.

2.15. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Statistica software (version 15, StatSoft Polska Sp. z o.o.). A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was adopted for all tests. The normality of pre-intervention variable distributions was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and the homogeneity of variances was evaluated with Levene’s test. As the data did not meet assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance, non-parametric tests were used throughout the analysis. For descriptive statistics, both means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges were reported, reflecting the unimodal distributions and skewness/kurtosis values below 2.5. Baseline characteristics were compared between groups using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables. Within-group pre- and post-intervention results were compared using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Between-group comparisons of outcome changes were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test.

For all primary and secondary outcomes, effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d, calculated from group means and pooled standard deviations. This approach provides a standardized measure of the magnitude and precision of observed effects, facilitating interpretation and comparison across outcomes and studies. All analyses adhered to the intention-to-treat principle, and sensitivity analyses were conducted to confirm the robustness of findings. All 50 randomized participants were included in the intention-to-treat analysis. Sensitivity analysis comparing ITT and per-protocol populations revealed no significant differences in the main outcomes.

3. Results

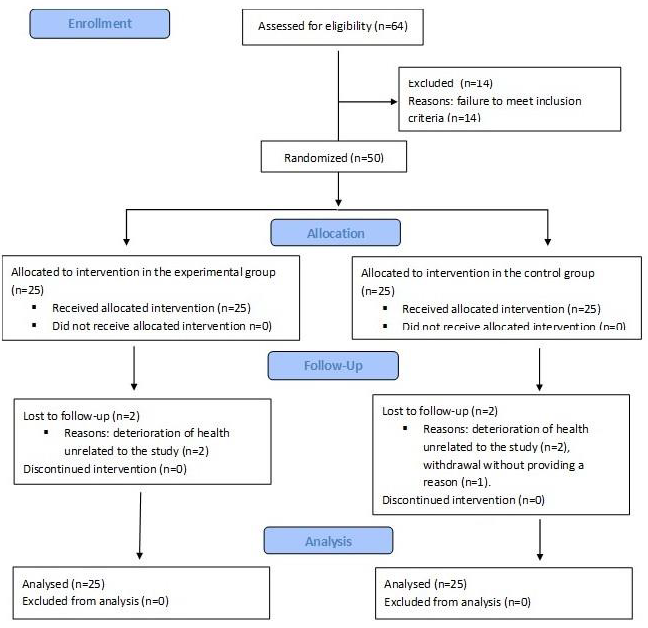

Between July 1, 2020, and June 30, 2022, 64 patients were screened for the trial. Fifty patients who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned to either the EG and CG. Five patients (10%) did not complete the trial. Two patients in the EG and two in the CG withdrew due to a deterioration in health unrelated to the procedures used in the study, while one patient in the CG withdrew without providing a reason. The remaining 45 participants completed the intervention. The participant flow is presented in

Figure 1.

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

Participants’ ages ranged from 45 to 82 years. BMI distribution was as follows: 15 participants (30%) had normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.99 kg/m²), 27 (54%) were overweight (BMI 25.0–29.99 kg/m²), 4 (8%) had obesity class I (BMI 30.0–34.99 kg/m²), and 4 (8%) had obesity class II (BMI 35.0–39.99 kg/m²). All participants (100%) had suffered an ischemic stroke 6–28 months prior to enrollment. Twenty-four participants (48%) had right-sided paresis, and 26 (52%) had left-sided paresis. In 24 patients (48%), the dominant limb was affected; in 26 (52%), the non-dominant limb. Brunnstrom Recovery Stages for the lower limb were: stage 3 in 4 (8%), stage 4 in 6 (12%), stage 5 in 8 (16%), and stage 6 in 32 (64%) participants. Increased muscle tone was not observed in 9 (58%) participants (grade 0, Modified Ashworth Scale), was slight in 9 (18%, grade I), and moderate in 3 (6%, grade II). Apart from 1 participant (2%) with severe dependence in activities of daily living (Barthel Index 21–60), all others (98%) were moderately dependent (Barthel Index 61–90). At baseline, there were no statistically significant differences between the EG and CG for any demographic or clinical variables (

Table 2 and

Table 3).

3.2. Primary Study Outcomes

BBS. After the intervention, both groups improved significantly on the BBS. In the EG, the mean BBS score increased from 43.83 (SD 8.85) to 49.50 (SD 7.82) (within-group p=0.001). In the CG, the mean increased from 46.00 (SD 9.80) to 49.23 (SD 9.80) (within-group p=0.009). The between-group difference in BBS change was 2.44 points (CI: –8.93 to 13.81), with a Cohen’s d of 0.27 (CI: –0.99 to 1.52), indicating a small effect size and no statistically significant difference between groups (pre-intervention p=0.408, post-intervention p=0.256;

Table 4).

10MWT. Gait speed improved significantly only in the CG, increasing from 0.63 m/s (SD 0.25) to 0.70 m/s (SD 0.21) (within-group p=0.015). The between-group difference in change was –0.07 m/s (CI: –0.37 to 0.23), Cohen’s d = –0.30 (CI: –1.55 to 0.96), again indicating a small and non-significant effect (pre-intervention p=0.948, post-intervention p = 0.543;

Table 4).

3.3. Secondary Study Outcomes

FRT. Functional reach increased significantly post-intervention only in the CG (from 29.87 [SD 9.29] cm to 34.50 [SD 8.64] cm, p=0.021). The between-group difference in change was 4.63 cm (99.99% CI: –5.24 to 14.50), Cohen’s d = 0.52 (CI: –0.60 to 1.63); however, this difference was not statistically significant (pre p=0.150, post p=0.870;

Table 4).

TUG Test. The CG required significantly less time post-intervention (from 13.07 [SD 6.56] to 11.13 [SD 4.88] seconds, p=0.009). The between-group difference in change was –1.94 seconds (CI: –8.30 to 4.42), Cohen’s d = –0.34 (CI: –1.44 to 0.77), with no significant difference between groups (pre p=0.958, post p=0.623;

Table 4).

FES-I. A significant decrease in fear of falling was observed only in the CG (from 28.47 [SD 8.96] to 26.10 [SD 9.10], p=0.002). The between-group difference in change was –2.37 points (CI: –12.31 to 7.57), Cohen’s d = –0.26 (CI: –1.37 to 0.84); differences between groups were not significant (pre p=0.525, post p=0.527;

Table 4).

Static Balance (Stabilometric Platform). No statistically significant changes were observed in CoP path length or 95% confidence ellipse area in either group (EG: p=0.385 and p=0.367; CG: p=0.824 and p=0.741). Between-group differences in change were 0.00 (CI: –11.01 to 11.01), Cohen’s d = 0.00 (CI: –1.10 to 1.10), with no significant differences at baseline or post-intervention (CoP path length: p=0.678 and p=0.675; ellipse area: p=0.597 and p=0.672;

Table 5).

Spatiotemporal Gait Parameters. Significant changes post-rehabilitation were observed only in the EG, where step length increased for both legs (right: from 27.4 [SD 8.2] cm to 30.3 [SD 9.0] cm, p=0.015; left: from 27.5 [SD 8.9] cm to 30.1 [SD 9.8] cm, p=0.449). The between-group differences in step length change were 2.90 cm (right leg: CI: –6.12 to 11.92), Cohen’s d = 0.35 (CI: –0.76 to 1.46), with no significant differences between groups (right: p=0.932; left: p=0.750).. In the EG, cadence decreased significantly (from 82.4 [SD 14.7] to 79.6 [SD 15.9] steps/min, p=0.029), but the between-group difference in change was not significant (p=0.250). Other gait parameters showed no significant within- or between-group differences (

Table 6).

4. Discussion

The BBS scores showed that both treadmill perturbation-based training performed six days a week for three weeks (the EG) and overground gait and balance training of matching frequency and duration (the CG) significantly improved body balance in chronic stroke patients. The post-intervention outcomes of the 10MWT demonstrated that overground walking speed significantly improved only in the CG, but the change was not statistically significantly bigger compared with the EG. Spatiotemporal gait measurements obtained for participants walking on the treadmill indicated a statistically significant increase in step length (cm) and a statistically significant decrease in cadence [steps/min] only in the EG. Even so, the spatiotemporal gait parameters in the EG were not significantly better post-intervention than in the CG. These results are inconclusive as to whether three weeks of treadmill perturbation-based training and conventional overground gait training of the same duration can improve gait efficiency in chronic stroke patients.

4.1. Comparison of This Study’s Results with Other Studies

To the authors’ knowledge, there are only two RCTs [

44,

45] that are comparable to this study because both of them used treadmill perturbation-based training and chronic stroke patients. However, they are also different from our trial in some respects. Esmaeili et al. [

45] conducted a pilot study with only 18 participants divided between the EG (n=10) and the CG (n=8), which did treadmill perturbation-based training and treadmill training without balance perturbations, respectively. In both groups, the treadmill belt speed was set according to participants’ preferences. In the EG, balance perturbations were induced by changes in the belt speed. The training session duration was tailored to patients’ capacity and did not extend beyond 30 minutes.

In the CG, the training session duration was set for each participant so that it matched the time completed by EG participants with similar overground walking speeds. Both groups completed a total of nine sessions over three weeks. As in our study, dynamic balance was assessed using the Mini-BESTest, and walking speed was measured using the 10MWT. Post-intervention measurements showed that while dynamic balance improved significantly more in the EG than in the CG (p=0.007), walking speed did not significantly differentiate the groups, whether at a preferred pace (p=0.594) or a maximum speed (p=0.424). The results reported by Esmaeili et al. [

45] are, therefore, consistent with our findings, which also show improved dynamic balance in chronic stroke patients after treadmill perturbation-based training.

The other RCT was conducted by Hu et al. [

44] with 40 chronic stroke patients with gait impairments, who were equally divided into the EG and the CG (n=20 each group). Both groups exercised 30 minutes per day, five days a week, over four weeks. The number of training sessions (20) was thus comparable to that in our trial (18). As in our study, the CG participants received conventional overground gait and balance training, while the EG performed treadmill perturbation-based training. In the first two weeks, the treadmill walking speed was gradually increased to tailor it to the participants’ capacity; in the following two weeks, balance perturbations induced by belt speed changes (forward/backward translations) and its side-to-side movements (lateral translations) were introduced. The amplitude (cm), velocity (cm/s), and acceleration (cm/s²) of the perturbations were gradually increased from session to session. The protocol of perturbation-based training used by Hu et al. [

44] was similar to that in our trial. Measurements performed after 2 and 4 weeks showed significant improvements in normal and fast walking speeds in the EG (p < 0.05) but not in the CG (p > 0.05); moreover, in the EG, they were statistically significantly greater in the other group (p < 0.05). Dynamic balance during fast walking speed measured with the TUG Test also showed significant improvement only in the EG (p < 0.05 vs. p > 0.05), but intergroup differences were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Based on these findings, Hu et al. [

44] concluded that treadmill perturbation-based training could improve ambulation in chronic stroke patients, but its ability to enhance their dynamic balance was not significant. Therefore, although the research methodology used by Hu et al. [

44] and in our trial was similar, our participants showed improvement in dynamic balance but not in walking speed. Hu et al. [

44] recruited younger patients than we did (EG: 48.7 ± 14.8 years; CG: 43.1 ± 16.2 years), but the time since stroke was similar between our studies (mean 15.1 ± 16 months). Lower limb motor recovery assessed with the Brunnstrom scale was also comparable; in our study, it was stage 4 for most of the participants (64%) and stage 3 for only 8%. In Hu et al. [

44], stage 4 patients dominated the sample (48.5%), and stage 6 patients were the fewest (12.1%).

The effects of PBT on gait quality in chronic stroke patients were also analyzed in three clinical studies without control groups [

46,

47,

51]. However, they were conducted with only 10 [

51] and 12 [

46,

47] participants, respectively. In the study by Punt et al. [

51], 10 patients at least one-year post-stroke who had fallen at least once in the past six months participated in 10 training sessions involving treadmill walking over six weeks. The length of a single session ranged from 30 to 60 minutes and depended on participants’ physical capacity. The treadmill belt, whose speed was set to their preference, was accelerated, decelerated, and tilted laterally to induce perturbations. The study authors noted post-intervention statistically significant improvements (p<0.05) in participants’ gait speed and step length, as well as reductions in step time, stride time, and swing time, which led them to report an overall improvement in gait quality. Dusane et al. [

46] recruited 12 patients who suffered a stroke at least six months prior and exposed them to simulated slips (12 m/s²) and trips (16.75 m/s²) while they walked on a treadmill at their preferred speed. Each patient participated in three consecutive training sessions during which slips, trips, and a combination thereof were successively applied. During each session, postural stability (center of mass [CoM] position and velocity), trunk angle, the number of steps, and compensatory step length were measured. Slip training shifted the CoM forward, increased step length, and reduced the number of compensatory steps (p<0.05), while trip training decreased step length, number of steps, and trunk angle (p<0.05) without affecting the CoM position (p>0.05). Mixed training reduced step length and trunk angle (p<0.05) but CoM and step count remained unchanged. Dusane et al. [

46] suggested that PBT was capable of preventing falls by helping develop beneficial compensatory trunk and limb movements. The last of the three studies was conducted by Osman et al. [

47] and had 12 patients who were at least six months post-stroke. The study spanned six weeks, during which patients walked on a split-belt treadmill. Perturbations were induced by increasing the belt speed to 15 m/s² for 0.25 second and then reducing it to the previous speed. Each patient completed 15 sessions of 90 seconds, which consisted of a pre-perturbation phase (30 seconds), a perturbation phase (30 seconds), and a post-perturbation phase (30 seconds). Perturbations were randomly induced in the stance phase of the non-paretic leg. While exercising, participants wore a safety harness that protected them from falls. Walking speed improved statistically significantly for both preferred (p=0.003) and maximum pace (p=0.010), and the number of treadmill falls decreased (p=0.015). The authors concluded that PBT improves chronic stroke patients’ gait speed and compensatory movements, thus making them less likely to fall.

Although our findings and those reported by other authors [

44,

45,

46,

47,

51] are not entirely consistent, they confirm the ability of TPBT to help chronic stroke patients improve dynamic balance and gait. Our study and that by Esmaeili et al. [

45] found that the TPBT improved participants’ postural balance but did not influence their gait quality, Hu et al. [

44] reported improved gait and no changes in balance, Osman et al. [

47] observed improvements in both these parameters, Punt et al. [

51] noted gait improvements and Dusane et al. [

46] found their patients to develop protective compensatory movements following TPBT. These findings are promising, but given the limited number of such studies and the inconsistency of their results arising from the variety of research methodologies used, more RCTs are needed to unambiguously determine PBT types that will be the most effective in enhancing postural balance and gait quality in chronic stroke patients, and in reducing their fear of falling.

4.2. Strengths of the Study

The study was designed as a randomized controlled trial with a control group. The sizes of the EG and the CG were determined based on the results of a pilot study. All training sessions were provided at the same rehabilitation center and were supervised by physiotherapists to ensure that both groups exercised in a uniform and reliable manner. All assessments were carried out by the same team of physiotherapists. Results for 4 participants who failed to complete the trial were approximated and processed statistically using intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis.

4.3. Limitations of the Study

One limitation of the trial is that the intervention results were only compared with the baseline values of the parameters under study, without considering TPBT’s long-term impacts. Unfortunately, a follow-up assessment could not be performed because most of the trial participants lived in locations that were distant from the rehabilitation center. Because of the nature of the intervention, blinding of the participants and medical personnel was not possible, either.

5. Conclusions

The trial demonstrated that 18 sessions of treadmill perturbation-based training performed by chronic stroke patients over 3 weeks positively influenced their body balance, comparably to conventional overground gait and balance training. However, the PBT neither reduced participants’ fear of falling nor increased their walking speed. In the EG, spatiotemporal gait analysis revealed a significant increase in step length (cm) and a significant decrease in cadence [steps/min]. These changes do not conclusively indicate whether three weeks of the PBT can improve gait efficiency in chronic stroke patients. More RCTs are needed to create PBT protocols that will improve balance and gait and reduce the fear of falling in these patients the most effectively

Author Identification: Kamila Niewolak, PT – Head of the Medical Rehabilitation Department at "Solanki" Health Resort, Inowrocław. She graduated in July 2006 from the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Collegium Medicum in Bydgoszcz, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń. Since then, she has worked as a physiotherapist, primarily with neurological, cardiological, and geriatric patients. Her main research interests include gait re-education and fall prevention. Since 2015, she has been an active member of the Polish Physiotherapy Society, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Branch. She also collaborates with medical universities as a clinical instructor and practical training educator.Joanna Antkiewicz, PT is a licensed physiotherapist specializing in neurorehabilitation. Since 2019, she has been part of the therapeutic team at the "Solanki" Health Resort in Inowrocław. She earned her BSc in Physiotherapy in 2016 and completed her MSc in December 2018 at the Military Medical Faculty of the Medical University of Łódź. Her clinical and academic interests focus on integrating advanced technologies, especially robotics, into gait re-education for neurological patients. She is certified as a G-EO System user (REHA Technology) and has completed Clinical Training Levels 1 and 2 with EKSO BIONICS™, strengthening her expertise in robotic-assisted rehabilitation.Laura Piejko, PT, PhD – Assistant Professor at the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland. She earned her PhD in January 2018 and holds an MSc in Physiotherapy (2013). She has several years of professional experience as a licensed physiotherapist. Currently, she heads the Clinical Unit of Physiotherapy in Psychiatry at the Academy. Her research focuses on a multidisciplinary approach to skin aging prevention, including the use of physical treatments and chemical agents for managing various skin conditions, such as scars. Grzegorz Sobota MsC, PhD is an associate professor in the Department of Biomechanics and Head of Biomechanics Laboratory at the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice. He received his PH.D. in 2008 and habilitation in 2019 at the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice. His research interests include gait analysis, biomechanical movement analysis, and biological signal processing. He is a member of the Polish Society of Biomechanics.Prof. Adam Maszczyk is a full professor, Head of the Department of Statistics, Methodology, and Informatics, and Director of the Doctoral School at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland. He earned his PhD in 2007, habilitation in 2014, and was awarded the title of professor in 2020. With over 20 years of academic experience, his work focuses on advanced statistics, machine learning, biomechanics, and performance optimization in elite sport. He is Deputy Editor-in-Chief and Technical-Statistical Editor of the Journal of Human Kinetics. His research interests include predictive analytics in sport, neurophysiological adaptations, and evidence-based training design. Prof. Maszczyk is an active member of several scientific societies and has received multiple national awards for academic excellence and methodological innovation.Agnieszka Nawrat-Szołtysik, PT, PhD is an assistant professor at the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Faculty of Physiotherapy, and Head of the Department of Diagnostics and Rehabilitation Programming. She also leads the Rehabilitation and Occupational Therapy Unit at the Święta Elżbieta Centre in Ruda Śląska. She earned her MSc in Physiotherapy in 2007 and PhD in Physical Culture Sciences in 2014 from the same institution. She also completed postgraduate studies in Healthcare Management in 2010. Since 2010, she has been part of the Academy’s research and teaching staff. She has worked as a physiotherapist at the Święta Elżbieta Centre since 2003 and since 2023 has also provided home rehabilitation at the Euromed Clinic. She conducts training for healthcare professionals in geriatrics and coordinates national senior programs. Her research interests include aging, physical activity, body composition, bone mass, fracture prevention, and geriatric syndromes.Prof. Józef Opara, MD, PhD is a Full Professor in the Chair of Clinical Physiotherapy at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice. He graduated as a physician from the Silesian Academy of Medicine in 1967 and holds specializations in Neurology (1977) and Medical Rehabilitation (1982). He earned his MD in 1983 and completed habilitation in 1998. In 2008, he was awarded the title of Full Professor. From 1980 to 2006, he led the Department of Neurological Rehabilitation at the Silesian Centre of Rehabilitation in Tarnowskie Góry. Since 1999, he has been affiliated with the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice. His research covers stroke rehabilitation, spasticity, spinal cord injury, low back pain, spondylotic cervical myelopathy, post-polio syndrome, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, traumatic brain injury, clinimetrics, quality of life, and physical activity. He is a member of the World Federation for NeuroRehabilitation (WFNR), the European Society for NeuroRehabilitation, and the Polish Society for Neurological Rehabilitation.Prof. Cezary Kucio, MD is a professor of medical and health sciences and a specialist in internal medicine. From 1981 to 1992, he worked as an assistant and assistant professor at the Department and Clinic of Gastroenterology, Silesian Medical University in Katowice. Between 1992 and 2024, he served as Head of Internal Medicine Departments in hospitals in Czeladź, Jaworzno, and at the District Railway Hospital in Katowice. Since 2003, he has been a professor at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, and since 2007, Head of the Department of Physiotherapy in Internal Medicine. He was also Dean of the Faculty of Physiotherapy at the Academy from 2008 to 2016. His scientific achievements include authorship or co-authorship of 92 peer-reviewed articles (h-index 19), 27 congress reports, 3 textbooks (as editor or co-editor), and 15 book chapters. He has supervised 9 doctoral theses and led internal medicine specialization training for 21 physicians.Anna Polak, PT, PhD is an Associate Professor at the Academy of Physical Education in Katowice. She currently serves as Dean of the Faculty of Physiotherapy and Head of the Department of Clinical Physiotherapy. She holds a PhD in Medical Sciences (1999) and a postdoctoral degree (habilitation) in Medical and Health Sciences, in the field of Physical Culture Sciences (2018). Her clinical and academic expertise focuses on chronic wound treatment and geriatric rehabilitation. Her research specialization includes the use of physical modalities—particularly electrotherapy—in chronic wound management, as well as physiotherapy in geriatric and neurological patients. She is a member of the European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: AP, KN, JO; LP; Methodology: AP, KN, JO, LP; Software: KN, JA, GS; Formal Analysis, AP, KN, AM, JO, LP, CK; Investigation: KN, AP, JA; AN-S; Resources: AP, KN, LP, AN-S, Data Curation: AM, AP, KN, GS: Writing – Original Draft Preparation: AP, LP, AM, CK, Writing – Review & Editing: AP, JO, AM,.

Funding

The study was co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund for the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship (Poland; no. RPKK.01.02.01-04-0016/18).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study conformed to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Bioethics Committee for Scientific Research at the Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education in Katowice, Poland (Resolution No. 5/2020). The trial was prospectively registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Registry: ISRCTN17138124.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all patients involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the entire team of “Solanki” Health Resort Inowrocław Ltd. in Inowrocław, especially the physicians and physiotherapists whose commitment supported the clinical part of the study, as well as the individuals who provided legal and administrative support for the implementation of the study under the grant. The authors also extend their thanks to MSc Eng. Wojciech Marszałek and Dr. Krzysztof Czupryna for their assistance in developing the study concept and methodology.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript

| UI |

Uncertainty interval |

| RR |

Relative risk |

| CI |

Confidence interval |

| PBT |

Perturbation-based balance training |

| TPBT |

Treadmill perturbation-based balance training |

| RCT |

Randomized clinical trial |

| EG |

Experimental group |

| CG |

Control group |

| ISRCTN |

International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number |

| MMSE |

Mini-Mental State Examination |

| GDS |

Geriatric Depression Scale |

| BBS |

Berg Balance Scale |

| FRT |

Functional Reach Test |

| TUG |

Timed Up and Go |

| ICC |

Intraclass Correlation Coefficient |

| AUC |

Area Under the Curve |

| 10MWT |

10-Meter Walk Test |

| FES-I |

Falls Efficacy Scale–International |

| ITT |

Intention-to-treat |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| Q1 |

Lower quartile |

| Q3 |

Upper quartile |

| CoP |

Center of pressure |

| CoM |

Center of mass |

References

- Johnson, C.O.; Nguyen, M.; Roth, G.A.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019, 18, 439–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Norrving, B.; Mensah, G.A. Global Burden of Stroke. Circ Res 2017, 120, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, C.; Subbarayan, S.; Paton, P.; et al. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for the Improvement of Post-Stroke Quality of Life amongst Older Stroke Survivors: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews (The SENATOR ONTOP Series), Vol 10.; 2019. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, P.W.; Min, Lai, S.; Keighley, J. Defining post-stroke recovery: Implications for design and interpretation of drug trials. Neuropharmacology 2000;39, 835-841. [CrossRef]

- Demain, S.; Wiles, R.; Roberts, L.; et al. Recovery plateau following stroke: Fact or fiction? Disabil Rehabil. 2006, 28, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taub, E.; Miller, N.E.; Novack, T.A.; et al. Nepomuceno CS, Connell JS CJ. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1993, 74, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitall, J.; Waller, S.M.C.; Silver, K.H.C.; et al. Repetitive bilateral arm training with rhythmic auditory cueing improves motor function in chronic hemiparetic stroke. Stroke 2000, 31, 2390–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sterr, A.; Elbert, T.; Berthold, I.; et al. Longer versus shorter daily constraint-induced movement therapy of chronic hemiparesis: An exploratory study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 374–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sullivan, K.J.; Knowlton, B.J.; Dobkin, B.H. Step training with body weight support: Effect of treadmill speed and practice paradigms on poststroke locomotor recovery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2002, 83, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ada, L.; Dean, C.M.; Hall, J.M.; et al. A treadmill and overground walking program improves walking in persons residing in the community after stroke: A placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2003, 84, 1486–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dettmers, C.; Teske, U.; Hamzei, F.; et al. Distributed form of constraint-induced movement therapy improves functional outcome and quality of life after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2005, 86, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, K.H.; Lee, W.H. Effect of treadmill training based real-world video recording on balance and gait in chronic stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Gait Posture 2014, 39, 523–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stroke rehabilitation in adults NICE guideline. 2023, (October 2023). www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng236.

- De Peretti, C.; Grimaud, O.; Tuppin, P.; et al. Prévalence des accidents vasculaires cérébraux et de leurs séquelles et impact sur les activités de la vie quotidienne : apports des enquêtes déclaratives Handicap-santé-ménages et Handicap-santé-institution, 2008-2009. Bull Epidémiologique Hebd 2012, 1(January), 1-6.

- Jørgensen, H.S.; Nakayama, H.; Raaschou, H.O.; et al. Recovery of walking function in stroke patients: The copenhagen stroke study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995, 76, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wade, D.T.; Wood, V.A.; Heller, A.; et al. Walking after stroke. Measurement and recovery over the first 3 months. Scand J Rehabil Med. 1987, 19, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesse, S. Treadmill training with partial body weight support after stroke: A review. NeuroRehabilitation 2008, 23, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pohl, P. S, Perera, S.; Duncan, P.W.; et al. Gains in Distance Walking in a 3-Month Follow-up Poststroke: What Changes? Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2004, 18, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Haart, M.; Geurts, A.C.; Huidekoper, S.C. Recovery of standing balance in postacute stroke patients: A rehabilitation cohort study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 85, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasseel-Ponche, S.; Yelnik, A.P.; Bonan, I.V. Motor strategies of postural control after hemispheric stroke. Neurophysiol Clin 2015, 45, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, S.E.; Ferrucci, L.; Volapto, S.; et al. Risk factors for falling in home-dwelling older women with stroke: the women’s health and aging study. Stroke 2003, 34, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgen, B.; Beninato, M.; Sullivan, P.E. The association of balance capacity and falls self-efficacy with history of falling in community-dwelling people with chronic stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006, 87, 554–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, A.A.; Van Puymbroeck, M.; Altenburger, P.A.; et al. Balance is associated with quality of life in chronic stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil 2013, 20, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eng, J.J.; Pang, M.Y.C.; Ashe, M.C. Balance, falls, and bone health: Role of exercise in reducing fracture risk after stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev 2008, 45, 297–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Duijnhoven, H.J.R.; Heeren, A.; Peters, M.A.M.; et al. Effects of Exercise Therapy on Balance Capacity in Chronic Stroke: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Stroke 2016, 47, 2603–2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Depaul, V.G.; Wishart, L.R.; Richardson, J.; et al. Varied overground walking training versus body-weight-supported treadmill training in adults within 1 year of stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2015, 29, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yen, C.L.; Wang, R.Y.; Liao, K.K.; et al. Gait training-induced change in corticomotor excitability in patients with chronic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2008, 22, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, A.; Merlo-Rains, A.; Peters, D.; et al. Body weight-supported treadmill training is no better than overground training for individuals with chronic stroke: A randomized controlled trial. Top Stroke Rehabil 2014, 21, 462–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.; Taly, A.B.; Gupta, A.; et al. Bodyweight-supported treadmill training for retraining gait among chronic stroke survivors: A randomized controlled study. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2016, 59, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, I.H.; Yang, Y.R.; Chan, R.C.; et al. Turning-based treadmill training improves turning performance and gait symmetry after stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2014, 28, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langhammer, B.; Stanghelle, J.K. Exercise on a treadmill or walking outdoors? A randomized controlled trial comparing effectiveness of two walking exercise programmes late after stroke. Clin Rehabil 2010, 24, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierbaum, S.; Peper, A.; Karamanidis, K.; et al. Adaptational responses in dynamic stability during disturbed walking in the elderly. J Biomech 2010, 43, 2362–2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bierbaum, S.; Peper, A.; Karamanidis, K. Adaptive feedback potential in dynamic stability during disturbed walking in the elderly. J Biomech 2011, 44, 1921–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smania, N.; Corato, E.; Tinazzi, M.; et al. Effect of balance training on postural instability in patients with idiopathic parkinsong’s disease. Neurorehabil Neural Repair 2010, 24, 826–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maki, B.E.; Cheng, K.C.C.; Mansfield, A.; et al. Preventing falls in older adults: New interventions to promote more effective change-in-support balance reactions. J Electromyogr Kinesiol 2008, 18, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, A.; Peters, A.L.; Liu, B.A.; et al. Effect of a perturbation-based balance training program on compensatory stepping and grasping reactions in older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther 2010, 90, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanvi, B.; Feng, Y.; Yi-Chung, P. Learning to resist gait-slip falls: Long-term retention in community-dwelling older adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012, 93, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, Y.C.; Bhatt, T.; Yang, F.; et al. Perturbation training can reduce community-dwelling older adults’ annual fall risk: A randomized controlled trial. Journals Gerontol - Ser A Biol Sci Med Sci 2014, 69, 1586–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pai, Y.C.; Yang, F.; Bhatt, T.; et al. Learning from laboratory-induced falling: Long-term motor retention among older adults. Age (Omaha) 2014, 36, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, T.; Dusane, S.; Gangwani, R. eta l. Motor adaptation and immediate retention to overground gait-slip perturbation training in people with chronic stroke: an experimental trial with a comparison group. Front Sport Act Living 2023, 5(September), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Protas, E.J.; Mitchell, K.; Williams, A.; et al. Gait and step training to reduce falls in Parkinson’s disease. NeuroRehabilitation 2005, 20, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, M.; Shiba, Y.; Sato, H.; et al. Motor adaptation during slip-perturbed gait in older adults. J Phys Ther Sci 2008, 20, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lurie, J.D.; Zagaria, A.B.; Pidgeon, D.M.; et al. Pilot comparative effectiveness study of surface perturbation treadmill training to prevent falls in older adults. BMC Geriatr 2013, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Jin, L.; Wang, Y.; et al. Feasibility of challenging treadmill speed-dependent gait and perturbation-induced balance training in chronic stroke patients with low ambulation ability: a randomized controlled trial. Front Neurol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esmaeili, V.; Juneau, A.; Dyer, J.O.; et al. Intense and unpredictable perturbations during gait training improve dynamic balance abilities in chronic hemiparetic individuals: A randomized controlled pilot trial. J Neuroeng Rehabil 2020, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusane, S.; Bhatt, T. Mixed slip-trip perturbation training for improving reactive responses in people with chronic stroke. J Neurophysiol 2020, 124, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osman, H.E.; van den Bogert, A.J.; Reinthal, A. A progressive-individualized midstance gait perturbation protocol for reactive balance assessment in stroke survivors. J Biomech 2021, 23, 123:110477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shimada, H.; Obuchi, S.; Furuna, T.; et al. New intervention program for preventing falls among frail elderly people: The effects of perturbed walking exercise using a bilateral separated treadmill. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 83, 493–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, A.; Wong, J.S.; Bryce, J.; et al. Does perturbation-based balance training prevent falls? Systematic review and meta-analysis of preliminary randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2015, 95, 700–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bang, D.H.; Shin, W.S.; Noh, H.J.; et al. Effect of unstable surface training on walking ability in stroke patients. J Phys Ther Sci 2014, 26, 1689–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Punt, M.; Bruijn, S.M.; van de Port, I.G.; et al. Does a Perturbation-Based Gait Intervention Enhance Gait Stability in Fall-Prone Stroke Survivors? A Pilot Study. J Appl Biomech 2019, 35, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975, 12, 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res 1982-1983, 17, 37-49. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brott, T.; Adams, H.P.; Olinger, C.P.; et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: A clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989, 20, 864–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashworth, B. Preliminary trial of carisoprodol in multiple sclerosis. Practitioner 1964, 192, 540–542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Charalambous, C.P. Interrater reliability of a modified ashworth scale of muscle spasticity. Class Pap Orthop. 2014:415-417. [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, F.I.; Barthel, D.W. Functional evaluation: The Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965, 14, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Berg, K.O.; Wood-Dauphinee, S.L.; Williams, J.I.; et al. Measuring balance in the elderly: Validation of an instrument. Can J Public Health 1992, 83(Suppl 2), 7–11.

- Duncan, P.W.; Weiner, D.K.; Chandler, J.; et al. Functional reach: A new clinical measure of balance. Journals Gerontol 1990, 45, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podsiadlo, D.; Richardson, S. The Timed Up and Go: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991, 39, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, J.L.; Potter, K.; Blankshain, K.; et al. A core set of outcome measures for adults with neurologic conditions undergoing rehabilitation: a clinical practice guideline. J Neurol Phys Ther 2018, 42, 174–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Al-Eisa, E.S.; Anwer, S.; et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of three scales for measuring balance in patients with chronic stroke. BMC Neurol 2018, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahin, F.; Yilmaz, F.; Ozmaden, A.; et al. Reliability and validity of the Turkish version of the Berg Balance Scale. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2008, 31, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchán-Baeza, J.A.; González-Sánchez, M.; Cuesta-Vargas, A.I. Reliability in the parameterization of the functional reach test in elderly stroke patients: A pilot study. Biomed Res Int 2014, 2014, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flansbjer, U.B.; Holmbäck, A.M.; Downham, D. Reliability of gait performance tests in men and women with hemiparesis after stroke. J Rehabil Med 2005, 37, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossier, P.; Wade, D.T. Validity and reliability comparison of 4 mobility measures in patients presenting with neurologic impairment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2001, 82, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collen, F.M.; Wade, D.T.; Bradshaw, C.M. Mobility after stroke: Reliability of measures of impairment and disability. Disabil Rehabil 1990, 12, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson, S.; Connell, L. The psychometric properties and clinical utility of measures of walking and mobility in neurological conditions: A systematic review Clin Rehabil 2009, 23, 1018-1033. [CrossRef]

- Yardley, L.; Beyer, N.; Hauer, K.; et al. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005, 34, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, S.A. Analysis of measurement tools of fear of falling for high-risk, community-dwelling older adults. Clin Nurs Res 2012, 21, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, M.T.; Friscia, L.A.; Whitney, S.L.; et al. Reliability and validity of the falls efficacy scale-international (FES-I) in individuals with dizziness and imbalance. Otol Neurotol 2013, 34, 1104–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh, M.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Habibi, S.A.; et al. Reliability and validity of fall efficacy scale-international in people with Parkinson’s disease during on- And off-drug phases.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).