1. Introduction

Balance impairment, with an estimated prevalence of 83% in stroke patients, can elevate fall risks and hinder daily activities [

1]. Such imbalances after a stroke arise from factors like muscle weakness, abnormal muscle tone, sensory deficits, reduced attention, as well as vision and spatial awareness abnormalities [

2,

3]. Studies have found that stroke patients who possess the ability to stand frequently exhibit delayed and disrupted equilibrium reactions, exaggerated postural sway in both sagittal and frontal planes, and reduced weight-bearing on the affected limb, all of which heighten their risk of falling [

4]. Studies highlight that within the first six months post-discharge, between 36% to 73% of stroke survivors experience falls [

5,

6]. Furthermore, one year post-stroke, the incidence of falls persists at a notable level, with 40% to 58% of these individuals still experiencing falls [

7,

8]. These incidents not only raise the risk of injury but can lead to medical complications, extended rehabilitation, increased costs, and psychological distress, such as fear of further falls [

9,

10,

11].

Consequently, reducing the risk of falls and their negative consequences is a crucial aspect of stroke rehabilitation. Given that balance impairments following a stroke are closely linked to the risk of falls, it is crucial to comprehensively assess the balance of affected individuals. Through such evaluations, at-risk patients can be identified and appropriate rehabilitation measures can be planned. Previous studies have employed various tools to assess balance, including the Berg Balance Scale, Functional Reach Test, Timed Up and Go Test, Mini-BESTest and Functional Gait Assessment (FGA) [

12,

13,

14,

15].

However, the majority of these assessment tools focus on forward walking and stepping, with the exception of the FGA, which includes a component for measuring backward walking. Backward walking has been found to demand higher levels of neuromuscular control, proprioception, and protective reflexes than forward walking, due to its greater complexity in motor planning and coordination [

16]. Consequently, backward walking has been proposed as a more sensitive measure of balance and mobility [

17,

18]. Incorporating backward walking into balance assessment tools may offer a more comprehensive evaluation of balance in stroke patients. Such inclusion can capture deficits not evident in forward walking assessments alone, thus providing a holistic understanding of post-stroke balance impairments. Backward walking is a crucial component in assessing the physical function of stroke patients, yet it is often marginalized in many gait assessments [

19]. The 3-Meter Backward Walk Test

(3MBWT) was developed to target this specific function. While its reliability has been validated in earlier studies with stroke patients [

20,

21]; there is an ongoing need to continuously reaffirm this reliability, especially when comparing it with well-regarded, established assessments. Choosing the FGA for comparison is intentional. The FGA provides a comprehensive view of gait and importantly, incorporates backward walking. This makes it a suitable benchmark for the 3MBWT. By comparing the 3MBWT to the FGA score, we intend to contextualize the 3MBWT within the broader landscape of gait evaluation instruments, emphasizing its potential significance in stroke patient assessments.

Furthermore, contrasting the 3MBWT with the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT) and the 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) is crucial for evaluating its construct validity and establishing its distinct place in gait evaluations. Additionally, considering the heightened fall risk in stroke survivors, investigating the correlation between 3MBWT outcomes and fall incidents is paramount. Through this research, we aim to clarify the role and efficacy of the 3MBWT among the array of clinical assessment tools for stroke patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

The present study was conducted at the Neurological Rehabilitation Centre Rosenhügel Vienna, between October 2022 and February 2023. All participants gave their written informed consent according to the declaration of Helsinki, and the local ethics committee approved the study protocol.

The participants received a comprehensive introduction to the procedures and were asked to practice the backward walking one time before the start of the actual testing period. Before the 3MBWT, the participants rested in a seated position. Measurements were carried out under identical environmental conditions (e.g. consistent flooring, morning time for measurements, uniform lighting, and constant room size) to minimize potential influences from environmental factors." Our study, conducted in a "test-retest" design, examined the psychometric properties of the 3MBWT in stroke patients. Due to organizational constraints at the rehabilitation center, we were unable to assign the same physiotherapists to administer the tests. Consequently, five different physiotherapists were charged with administering the tests. Considering the potential variability introduced by different physiotherapists conducting the tests, we opted for three repeated measurements in accordance with our "test-retest" design. The test administration was timed using the same stopwatch, and participants were not informed of their recorded times. Each physiotherapist began with the 3MBWT, which was administered three times. Subsequently, within the same session, they conducted other tests, including the 10MWT, the 6MWT, and the FGA. Adequate breaks of 2 to 5 minutes were provided between successive 3MBWT assessments. These intervals allowed participants to recover their energy levels and minimize the potential impact of fatigue on their subsequent test performance.

2.2. Participants

The study enrolled patients of all genders who were at least 18 years old and diagnosed with haemorrhagic or ischemic stroke (within 1 month of onset) by a neurologist. Participants were required to have a Functional Ambulation Category (FAC) score of ≥4, indicating that they were able to walk without human assistance or devices [

22], and to be oriented and cooperative by general condition. Patients who had a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score below 24, Alzheimer's disease, similar dementia diseases, or were unable to follow instructions were excluded from the study.

2.3. Sample Size

The required sample size was determined using the Sample Size Calculator website (

https://wnarifin.github.io/ssc/ssalpha.html) [

23]. Prior research by Kocaman et al. (2021) and DeMark et al. (2023) concerning the validity and reliability of the 3MBWT in stroke patients, reported an ICC of 0.9. With such a high ICC, our required sample size would be only 16 participants. However, to adopt a more conservative approach and ensure the robustness of our findings, we based our calculations on a minimally acceptable ICC of 0.7. Using this more conservative estimate, with an alpha and beta set at 0.05 and 0.20, respectively, and accounting for a 10% anticipated dropout rate, our study required a sample size of 33 ambulatory stroke survivors.

2.4. Measurement

3.-Meter Backward Walk Test

For the 3MBWT, a distance of 3 meters is measured and marked with black tape on the floor. Participants stand at the starting point with their heels aligned with the tape. Upon the command "walk" they walk backward as quickly as possible, aiming to reach the 3-meter mark as accurately as possible before stopping. The elapsed time in seconds is recorded for each of the three trials, and participants are allowed to turn around during the test if they wish to do so. However, running during the test is not allowed to ensure safety and prevent falls. Throughout the entire test, the evaluator walks behind the participants to ensure their safety and prevent potential falls. A shorter time spent in competing the 3MBWT indicates better performance on the test [

20,

21].

Functional Gait Assessment

The FGA is a performance-based measure that assesses the ability to perform various walking tasks in a manner that reflects the complexity of everyday life activities. It is composed of 10 tasks that require different levels of balance control, including walking with changing speed, walking backward, walking while looking up and down, walking and turning, walking over obstacles, and walking on uneven surfaces. Each task is scored on a 4-point ordinal scale (0 to 3), with higher scores indicating better performance. The maximum score is 30 points, with each task worth up to 3 points. The FGA takes about 15-20 minutes to administer, and has been found to be a reliable and valid measure of gait function in different patient populations, including stroke patients. It is considered to be a comprehensive and sensitive tool for assessing gait function, and has been used in clinical and research settings to evaluate interventions and track changes in gait function over time [

15,

24].

10-meter walking test

The 10MWT was conducted by identifying a 14-meter path of flat, hard-unobstructed surface in the laboratory room. The first and last two meters were used as acceleration and deceleration zones to allow for a uniform walking pace. Four cones marked the beginning and end of the path as well as the start and end of the acceleration and deceleration zones. Each participant received a walking demonstration before the start of the test, but they did not have a practice walk themselves. The following standardized instructions were given: "This is our walking corridor. I want you to walk to the other end of the trail at a comfortable speed, as if you were walking down the street. Walk past the other end of the tape before stopping". With the instructions of "Ready, steady, go", the participant begins to walk. Participants were allowed to use their usual walking aid if needed and started behind the starting line with their toes touching the line. 10MW aims to assess forward gait speed, which can predict morbidity and mortality as well as functional ability [

25,

26].

6-minute walk test

The 6MWT is typically conducted in a long, straight corridor that is at least 30 meters long. However, in our rehabilitation facility, a corridor of 150 meters in length is used for the 6-minute walk test, where patients can complete multiple laps as needed. During the test, the participant is instructed to walk as many laps as possible along the corridor for 6 minutes. The participant is encouraged to walk at his or her own pace and to rest if necessary, but the timer continues to run throughout the entire 6 minutes. The distance covered in meters during the 6 minutes is recorded and used as a measure of functional capacity and endurance. The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of functional performance in a variety of patient populations [

26].

Functional Ambulation Categories

The FAC is a functional walking test that assesses ambulation ability. It utilizes a 6-point scale to determine the level of human support a patient requires while walking, irrespective of their use of personal assistive devices. It is important to note that the FAC does not measure endurance, as the patient is only required to walk a distance of approximately 10 feet. Although the FAC is commonly employed with stroke patients, it can be utilized with other populations as well [

22].

Demographic data (age, height, and weight), affected and dominant side, type and duration of stroke were recorded. Based on the recorded number of falls in the past two months, participants were categorized as 'Fallers' if they had experienced one or more falls, and 'Non-Fallers' if they had not experienced any falls. Furthermore, the well-being and gait safety of individuals were assessed using a single-item question rated on a scale ranging from 1 (very poor) to 10 (very good).

2.5. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were employed to depict the characteristics of the sample population. Continuous variables were reported as means, standard deviations (SDs), and medians with corresponding minimum and maximum values (min-max). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The association between repeated measurements of 3MBWT was calculated using the Pearson correlation coefficient and corresponding 95% confidence interval.

The construct validity was assessed by analysing the correlations between 3MBWT and the FGA, 10MWT, and 6MWT measures using either the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) or the Spearman correlation coefficient (rho), as appropriate. The resulting correlation coefficients were classified as poor (0.00-0.25), fair (0.26-0.50), moderate (0.51-0.75), or strong (0.76-1.00), according to established criteria [

27]. A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to compare scores obtained from the repeated assessments. This analysis is structured within participants, considering the variance in performance across the three trials for each participant.

An unpaired Wilcoxon test was used to compare the location parameter between patients with a history of falls and those without. The significance level was set at p=0.05 and p-values were not adjusted for multiple testing.

All statistical calculations were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

3. Results

Table 1 provides a detailed summary of the socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants, consisting of a total of 35 individuals, with females constituting 42.9% of the sample. The mean age of participants was 64.9 years (SD=13.9), and the average BMI was recorded at 26.3 kg/m² (SD=4.8). When it comes to the specifics of stroke, ischemic stroke was the most common type, affecting 94.3% of participants, while 5.7% had suffered a haemorrhagic stroke. Predominantly, participants were right-side dominant (97.1%) with the affliction of the stroke distributed almost equally between the left (51.4%) and the right (48.6%) sides. Results from the 3-Meter Backward Walk Test (3MBWT) showed a slight decrease in mean times across the three rounds, from an initial 11.6 seconds to 10.9 seconds in the last round.

However, a repeated measures ANOVA (p = 0.768) indicated no significant learning effect. In addition, the Functional Gait Assessment (FGA) revealed a median score of 24, while participants achieved a median completion time of 9 seconds on the 10-Meter Walk Test (10MWT). For the 6-Minute Walk Test (6-MWT), participants covered an average distance of 367.3 meters The Pearson correlation coefficients among the three rounds of measurements for the 3MBWT were notably high, ranging between r=0.97 and r=0.98, with very small confidence intervals (table 2) showing high reliability of measurement.

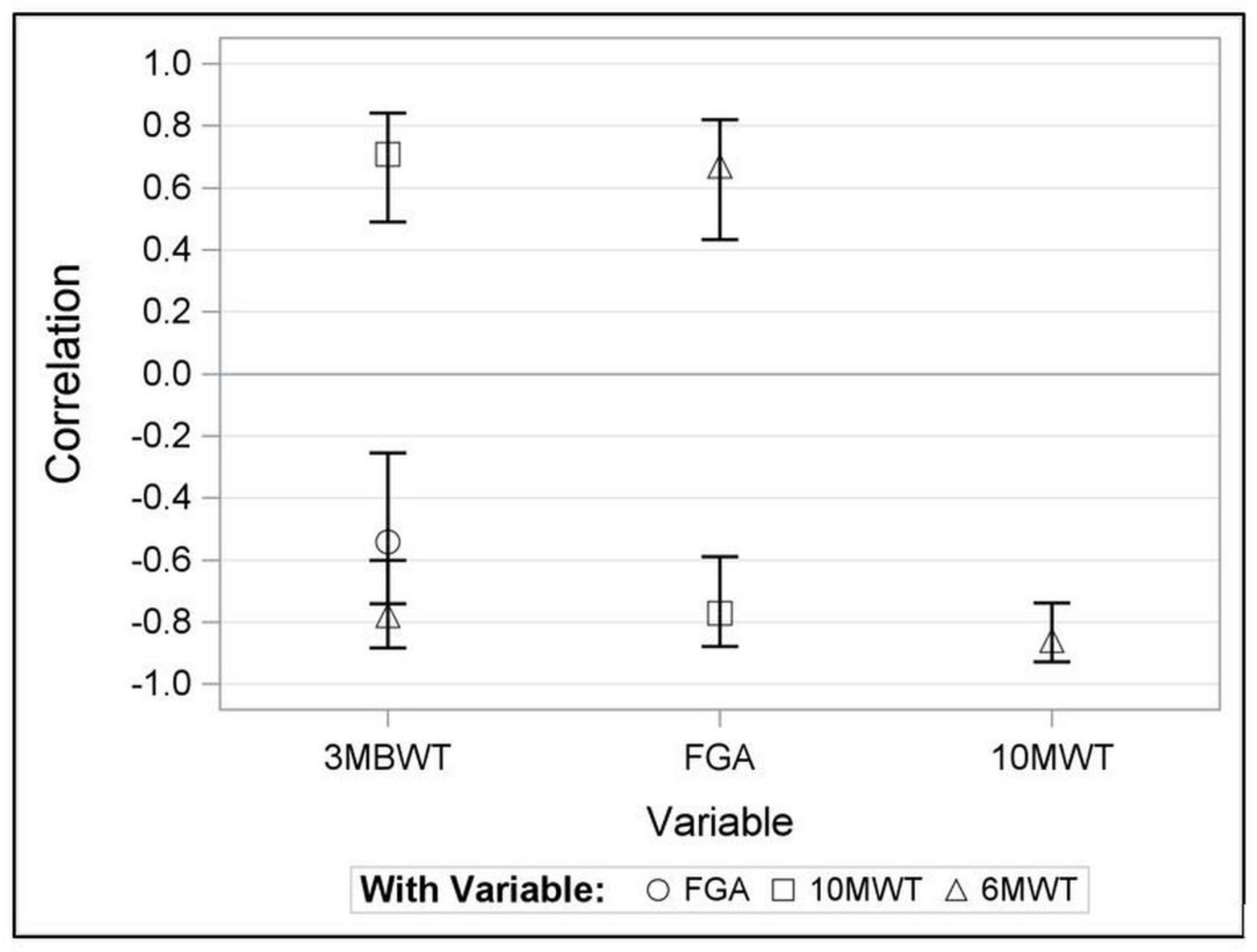

There was no significant change across the three rounds of the 3MBWT, (p = 0.768). The 3MBWT demonstrated substantial construct validity with both the 6MWT and 10MWT, showing correlations of r=-0.78 (95% CI -0.88 to -0.60) and r=0.71 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.84), respectively, while a moderate correlation was observed with the FGA (r=-0.54, 95% CI -0.74 to -0.26)

Figure 1.

Comparisons between patients with and without history of falls did not reveal significant differences in the 3MBWT (p=0.136), FGA score (p=0.532), 10 MWT (p=0.173), and 6MWT (p=0.108).

4. Discussion

Our study reveals a high reliability of the 3MBWT, as evidenced by a strong correlation (0.97-0.98; 95% CI: 0.95-0.99) across three measurements. This result is particularly striking considering it was achieved despite the involvement of five different physiotherapists. The ability to maintain such a high degree of reliability across varying treatment approaches underscores the robustness of the 3MBWT and its broad applicability in diverse clinical contexts. Furthermore, our findings align with those of DeMark et al. (2023), who reported a large intra-rater correlation of 0.96 in both subacute and chronic stroke patient groups, suggesting a similar level of reliability. Further, Kocaman et al. (2021) provided evidence of excellent internal consistency with a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.97, reinforcing the value of the 3MBWT. Upon utilizing ANOVA, our data showed no significant variance across three consecutive 3MBWT administrations. This could imply the lack of a learning effect. It is important to note that a detectable learning effect might affect test reliability, since improved scores could result from increased test familiarity rather than actual walking improvements. While our data supports the 3MBWT's reliability, further research is needed to conclusively determine the absence of a learning effect. Overall, these results underscore the potential of the 3MBWT as a valuable tool in clinical settings, especially for tailoring therapeutic interventions to individual patients.

The assessment of mobility and balance in stroke patients is crucial in the clinical setting for establishing accurate diagnoses, planning individual treatment methods, and evaluating the effectiveness of rehabilitation [

28]. In this respect, the 3MBWT has the potential to play a vital role in providing clinically relevant information that depicts patients' balance and mobility, and thus, predict the success of rehabilitation. In our study, we aimed to establish the clinical relevance of the 3MBWT by assessing its construct validity with the FGA, 6MWT and 10MWT, which are routinely used in clinical settings [

15,

28]. Our findings revealed that the 3MBWT exhibited substantial construct validity with the 6MWT and 10MWT, indicating that these tests measure similar constructs and suggesting that the 3MBWT can be a potent tool for assessing walking ability in stroke patients. However, when comparing the 3MBWT with the FGA, we found only a moderate correlation. This suggests that while the two measurements are associated, they seem to capture different aspects of gait and balance abilities.

The 3MBWT focuses on the ability to walk backward, requiring balance, coordination, and proprioceptive abilities [

16]. The FGA, on the other hand, measures a broader spectrum of gait and balance abilities, including the ability to perform head and neck movements while walking. This requires additional skills, such as integrating vestibular information and manoeuvring the body to maintain stability during these added tasks [

24]. Consequently, individuals who are capable of efficiently walking backward (and perform well in the 3MBWT) might encounter difficulties in performing complex tasks during the FGA, resulting in a moderate correlation between the two tests.

Our study aimed to form a relatively homogeneous group of stroke patients with FAC score of 4 or 5. This approach was intended to maintain consistency in terms of reliability and validity throughout our research. This objective was reflected in the low number of observed falls, with approximately 25% of participants reporting a fall within the last two months, a figure lower than the 36% to 73% reported in stroke patient literature [

5,

6]. As a result, this limited occurrence could have restricted the statistical power of the assessments conducted on the scores of the 3MBWT and FGA between stroke patients with and without a history of falls, resulting in non-significant p-values. These findings suggest that the low incidence of falls in our study group may have influenced the outcomes, limiting the ability to detect potential differences. It is crucial to consider that there may be unmeasured factors, such as muscle strength, depression, medication effects, or fear of falling, which could have a substantial impact on the risk of falls and should be considered in future investigations. While we attempted to account for some potential confounding variables, our single-item approach may not fully capture the complexity of fall risk. However, it is important to note that falls occurring in a backward direction have been reported in previous studies [

29]. Slowing of backward walking speed has also been observed in older individuals and has been associated with an increased risk of falls [

16,

30]. These findings suggest that the 3MBWT may indeed be a valuable tool for assessing fall risk in stroke patients. Additionally, the lack of association between the 3MBWT implementation time and fall frequency extends to the broader results of the FGA, highlighting the complexity of fall risk in stroke patients. Notably, the FGA has demonstrated the ability to predict falls within a 6-month period in a study involving community-dwelling older adults, exhibiting high sensitivity (100%) and specificity (72%) [

31]. While the association between FGA scores and fall risk in stroke patients has not been consistently confirmed, a moderate negative correlation has been found, suggesting that the FGA may have some predictive value in predicting fall risk in stroke patients [

32]. Therefore, conducting a more comprehensive assessment is crucial to gain a better understanding of fall risk in stroke patients.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, the sample size was small, which limited the power to detect differences between patients with and without a history of falls. Additionally, the study focused on a specific subset of stroke patients with a minimum FAC score of ≥4. While this homogeneity is advantageous for reliability and validity studies, it may restrict the external validity and generalizability to stroke patients with more severe impairments. Another limitation of this study involves the lack of an inter-rater reliability assessment for 3MBWT. Although we found high intra-rater reliability, evidenced by Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from r=0.97 to r=0.98 and an absence of significant learning effects, we could not directly evaluate the agreement across different raters. Future research should incorporate inter-rater reliability evaluations to ensure consistency across observers and further strengthen the reliability of the measurements.

5. Conclusion

The 3MBWT demonstrated high test-retest reliability and showed substantial convergent validity with established assessments of walking function in chronic stroke patients. We found no significant association between test performance on the 3MBWT and the frequency of falls. These findings highlight the need for a comprehensive evaluation of fall risk in stroke patients, considering factors beyond balance and coordination measurements.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.K. and M.R.; methodology, A.K., M.R., G.K., L.Y., and T.W.; formal analysis, A.K. and T.W.; investigation, A.K. M.R., G.K., L.Y., and T.W.; data curation, A.K. and M.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.K., M.R.; writing—review and editing, A.K., G.K.,L.Y. and T.W.; supervision, T.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Board of Vienna (EK_23_082_0523).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients and healthcare professionals at the participating rehabilitation centers for their contribution to the original data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, J.; Zhong, D.; Ye, J.; He, M.; Liu, X.; Zheng, H.; Jin, R.; Zhang, S.-L. Rehabilitation for balance impairment in patients after stroke: a protocol of a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyson SF, Hanley M, Chillala J, et al. Balance disability after stroke. Phys. Ther. 2006, 86, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasseel-Ponche S, Yelnik A and Bonan I. Motor strategies of postural control after hemispheric stroke. Neurophysiol. Clin./Clin. Neurophysiol. 2015, 45, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuzer, G.; Eser, F.; Karakus, D.; Karaoglan, B.; Stam, H.J. The effects of balance training on gait late after stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabilitation 2006, 20, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treger I, Shames J, Giaquinto S, et al. Return to work in stroke patients. Disabil. Rehabil. 2007, 29, 1397–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denissen S, Staring W, Kunkel D, et al. Interventions for preventing falls in people after stroke. Interventions for preventing falls in people after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019.

- Blennerhassett, J.M.; Dite, W.; Ramage, E.R.; Richmond, M.E. Changes in Balance and Walking From Stroke Rehabilitation to the Community: A Follow-Up Observational Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2012, 93, 1782–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburn, A.; Hyndman, D.; Pickering, R.; Yardley, L.; Harris, S. Predicting people with stroke at risk of falls. Age and Ageing 2008, 37, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joo, H.; Wang, G.; Yee, S.L.; Zhang, P.; Sleet, D. Economic Burden of Informal Caregiving Associated With History of Stroke and Falls Among Older Adults in the U.S. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017, 53, S197–S204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, L.M.; Phillips, V.L.; E Hunsaker, A.; Forducey, P.G. Falls among community-residing stroke survivors following inpatient rehabilitation: a descriptive analysis of longitudinal data. BMC Geriatr. 2009, 9, 46–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Pei, J.; Gou, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhong, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, L.; Dou, X. Risk factors for fear of falling in stroke patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e056340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tilson JK, Wu SS, Cen SY, et al. Characterizing and identifying risk for falls in the LEAPS study: a randomized clinical trial of interventions to improve walking poststroke. Stroke 2012, 43, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, P.S.; Hembree, J.A.; Thompson, M.E. Berg Balance Scale and Functional Reach: determining the best clinical tool for individuals post acute stroke. Clin. Rehabilitation 2004, 18, 811–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, C.S.; Liao, L.-R.; Chung, R.C.; Pang, M.Y. Psychometric Properties of the Mini-Balance Evaluation Systems Test (Mini-BESTest) in Community-Dwelling Individuals With Chronic Stroke. Phys. Ther. 2013, 93, 1102–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thieme, H.; Ritschel, C.; Zange, C. Reliability and Validity of the Functional Gait Assessment (German Version) in Subacute Stroke Patients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2009, 90, 1565–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, V.; Jain, T.; James, J.; Cornwall, M.; Aldrich, A.; de Heer, H.D. The 3-m Backwards Walk and Retrospective Falls: Diagnostic Accuracy of a Novel Clinical Measure. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 42, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- A Maritz, C.; Silbernagel, K.G.; Pohlig, R. Relationship of backward walking to clinical outcome measures used to predict falls in the older population: A factor analysis. Phys. Ther. Rehabilitation 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, E.M.; Kegelmeyer, D.A.; Kloos, A.D.; Nitta, M.; Raza, D.; Nichols-Larsen, D.S.; Fritz, N.E. Backward Walking and Dual-Task Assessment Improve Identification of Gait Impairments and Fall Risk in Individuals with MS. Mult. Scler. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rose, D.K.; DeMark, L.; Fox, E.J.; Clark, D.J.; Wludyka, P. A Backward Walking Training Program to Improve Balance and Mobility in Acute Stroke: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Neurol. Phys. Ther. 2018, 42, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, A.A.; Arslan, S.A.; Uğurlu, K.; Kırmacı, Z. .K.; Keskin, E. Validity and Reliability of The 3-Meter Backward Walk Test in Individuals with Stroke. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 105462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMark, L.A.; Fox, E.J.; Manes, M.R.; Conroy, C.; Rose, D.K. The 3-Meter Backward Walk Test (3MBWT): Reliability and validity in individuals with subacute and chronic stroke. Physiother. Theory Pr. 2022, 39, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teasell, R.; Foley, N.; Salter, K.; Bhogal, S.; Jutai, J.; Speechley, M. Evidence-Based Review of Stroke Rehabilitation: Executive Summary, 12th Edition. Top. Stroke Rehabilitation 2009, 16, 463–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifin, W.N. A Web-based Sample Size Calculator for Reliability Studies. Educ. Med. J. 2018, 10, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrisley, D.M.; Marchetti, G.F.; Kuharsky, D.K.; Whitney, S.L. Reliability, Internal Consistency, and Validity of Data Obtained With the Functional Gait Assessment. Phys. Ther. 2004, 84, 906–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalgas, U.; Severinsen, K.; Overgaard, K. Relations Between 6 Minute Walking Distance and 10 Meter Walking Speed in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis and Stroke. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2012, 93, 1167–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.K.; Nelson, M.; Brooks, D.; Salbach, N.M. Validation of stroke-specific protocols for the 10-meter walk test and 6-minute walk test conducted using 15-meter and 30-meter walkways. Top. Stroke Rehabilitation 2019, 27, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portney, L.G.; Watkins, M.P. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice; Pearson/Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- dos Santos, R.B.; Fiedler, A.; Badwal, A.; Legasto-Mulvale, J.M.; Sibley, K.M.; Olaleye, O.A.; Diermayr, G.; Salbach, N.M. Standardized tools for assessing balance and mobility in stroke clinical practice guidelines worldwide: A scoping review. Front. Rehabilitation Sci. 2023, 4, 1084085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Komisar, V.; Shishov, N.; Lo, B.; Korall, A.M.; Feldman, F.; Robinovitch, S.N. The Effect of Fall Biomechanics on Risk for Hip Fracture in Older Adults: A Cohort Study of Video-Captured Falls in Long-Term Care. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2020, 35, 1914–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritz, N.; Worstell, A.; Kloos, A.; Siles, A.; White, S.; Kegelmeyer, D. Backward walking measures are sensitive to age-related changes in mobility and balance. Gait Posture 2013, 37, 593–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wrisley, D.M.; Kumar, N.A. Functional Gait Assessment: Concurrent, Discriminative, and Predictive Validity in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Phys. Ther. 2010, 90, 761–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.; Choy, N.L. Investigating the Relationship of the Functional Gait Assessment to Spatiotemporal Parameters of Gait and Quality of Life in Individuals With Stroke. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2019, 42, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).