1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifactorial neurodegenerative disease that involves the progressive deterioration of voluntary motor control [

1]. It is the second most common age-related neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, affecting approximately 3% of adults over the age of 65 [

2]. The risk of developing this disease is twice as high in men as in women, although women have a higher mortality rate and a more rapid disease progression [

3]. Impaired voluntary motor control results in signs and symptoms such as bradykinesia, postural instability, rigidity and resting tremor, which commonly occur along with gait problems, arm, leg and trunk stiffness, and poor balance [

4]. These problems have a negative impact on functional ability and activities of daily living [

5].

The 6-minute walk test (6MWT) assesses in an integrated manner the response of the cardiorespiratory, circulatory, muscular and blood systems that a person develops during exercise [

6]. Functional integration is analysed by the maximum distance a person can cover on a flat surface for six minutes walking as fast as possible [

7,

8], and is widely used to assess exercise capacity in various diseases such as Silicosis [

9], COPD [

10], Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus [

11], Asthma [

12] and Pulmonary Disease [

13] due to its simplicity and low cost [

14], as it is performed at the subject’s own pace and does not require prior training or specific equipment [

15]. The 6MWT provides information on participants’ walking speed, cardiovascular fitness and endurance and correlates with aerobic fitness, functional capacity and morbidity and mortality [

16]. It also provides information on how motor symptoms affect the performance of daily activities, which is crucial for adjusting treatments and formulating rehabilitation strategies [

17]. Its simplicity and correlation with clinical outcomes make it a fundamental component in the evaluation and follow-up of patients with a wide variety of medical pathologies [

18,

19,

20]. In addition, the 6MWT has been shown to be useful in clinical assessment and to guide rehabilitation treatment planning in patients with moderate PD [

21].

However, it has been found that the 6MWT is commonly used to measure gait speed, as a measure of functional capacity, in people with gait limitations. Aunque el protocolo estándar de la 6MWT recomienda un pasillo de 30 m [

22], la literatura científica valida el uso de longitudes y recorridos alternativos [

23,

24]. The space limitation, which often exists in the clinical environment, creates the necessity of validating this test on other courses. Furthermore, the use of a square or rectangular circuit could increase the frequency of motor challenges, which is very important to assess in patients with Parkinson’s. Turning is a complex task that intensifies difficulties with dynamic balance and is a known precipitant of Freezing of Gait and the risk of falls. The objective of this study was to evaluate the absolute and relative reliability of the 6MWT on a 20m x 3.5m rectangular circuit in PD patients, thus allowing for the determination of its potential as an effective tool to evaluate their functional capacity and exercise endurance in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Extremadura data 01/30/2023 (reference number: 120/2022). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2024. All participants signed the informed consent form.

2.1. Sample Size

Accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a power of 0.8 in a two-sided test, 7 subjects are necessary in the first group and 7 in the second group to recognize as statistically significant a difference greater than or equal to 98 units. The common standard deviation is assumed to be 89 and the correlation coefficient between the initial and the final measurement is assumed to be 0.8. A drop-out rate of 20% has been anticipated. The null and alternative hypotheses were established following the study by Walter et al. [

25].

The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to assess the distribution of the data. Sample characterization was described using mean and standard deviation, together with the median and interquartile range. The Student’s t-test was applied to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the test and retest, as well as between genders. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

2.2. Participants

42 patients with PD (men= 27, women= 15), with a mean age of 66 years and an age range of 40-81 years, and stage II was the most common stage observed on the Hoehn and Yahr Scale, voluntarily participated in the test-retest reliability study. Participants met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Aged ≥18 years, (2) Diagnosed by a neurologist as stage I-III based on the Hoehn and Yahr Scale [

26], (3) No pathology contraindicating the physical exercise programme, for which the PAR-Q (Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire) [

27] was administered and (5) Signed informed consent for the study. During the study period, participants maintained their scheduled therapies and medications.

2.3. Procedure

Participants performed the 6MWT in two sessions one week apart. Both tests were conducted at approximately the same time of day to minimise variability caused by daily fluctuations in physical performance. They walked at a constant speed for 6 minutes in a 20m x 3.5m circuit marked by four cones located at the ends; on reaching each cone the participant had to go around it and continue walking until they reached the next cone, and so on until the six minutes were up. At the end of the test, the total number of laps completed, plus the metres of the last lap, were added together (1 lap = 47m). The test was carried out outdoors, on a flat surface, and participants were shown beforehand how to carry it out, by completing a full lap of the circuit from the starting point. During its development there were two evaluators to supervise the execution of the turns in the circuit and the test.

2.4. Clinical Evaluation

Sociodemographic. Participants completed a questionnaire focusing on age, gender, marital status, educational level, employment status, living arrangements, time of diagnosis of the disease, non-pharmacological therapies, psychopharmacological medication and frequency of falls in the last 8 weeks and last year.

Self-perception of fitness. The International Fitness Scale (IFIS) was use [

28]. This questionnaire assesses how participants perceive their general fitness, muscle strength, speed, cardiorespiratory fitness, agility and flexibility.

Quality of Life. This was assessed using the Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire PDQ-8. It is a summary index of 8 items present in the PDQ-39 that has been shown to be valid and reliable [

29]. It covers the following areas: mobility, activities of daily living, emotional wellbeing, stigma, social support, cognition, communication and bodily discomfort.

Fear of Falling. Participants completed the Falls Efficacy Scale International (FES-I) [

30]. This is a questionnaire that measures the level of concern about falling in 16 social and physical activities.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to assess the distribution of the data. Sample characterization was described using mean and standard deviation, together with the median and interquartile range. The Student’s t-test was applied to determine whether there were statistically significant differences between the test and retest, as well as between genders. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Reliability was examined using both relative and absolute reliability measures. Relative reliability was assessed through the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC3,1) [

31]. ICC data were calculated using the following parameters: (1) Model: 2-way random effects; (2) Type: single rater and, (3) Definition: consistency [

32]. The following classification was used for interpreting the ICC [

33]: an ICC less than 0.5 corresponds to poor reliability, an ICC from 0.5 to 0.75 corresponds to moderate reliability, an ICC from 0.75 to 0.9 corresponds to good reliability, and an ICC greater than 0.9 corresponds to excellent reliability. Absolute reliability was determined using the standard error of measurement (SEM) and the smallest real difference (SRD) [

34]. The SEM was calculated with the formula SEM=SD·

; where SD is the mean SD of the two repetitions. The SRD formula was SRD= 1.96·SEM·

. This score was subsequently converted to a percentage.

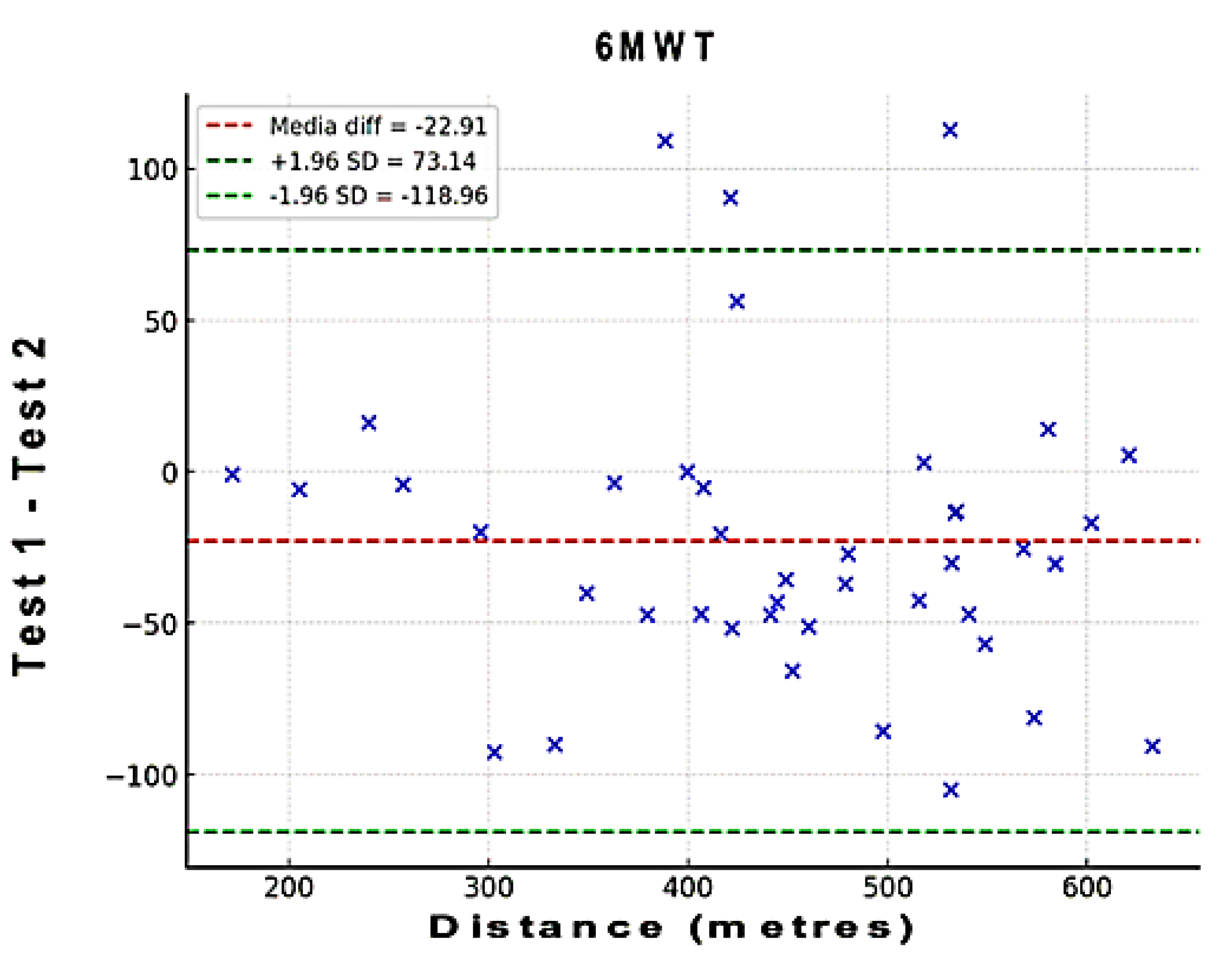

To assess the level of agreement between test and retest regarding distance of the 6MWT, a Bland-Altman analysis was performed. In these plots, the x-axis represents the mean of the test, and the y-axis shows the difference between the two measurements (A – B; A=test; B=retest). Bias and 95% limits of agreement (LOA) were calculated. Bias values close to zero represent strong agreement and the smaller range between these two LOA are interpreted as better agreement [

35].

3. Results

Table 1 and

Table 2 include age, anthropometric measurements and socio-demographic characteristics, for the total sample and men’s and women’s sub-groups.

No significant differences were observed overall between the descriptive variables for the entire sample. There were also no significant differences between the subgroups of men and women in any of the variables studied, except for the variable height and fear of falling, where differences between men and women did exist.

Table 3 shows the descriptive data of the test and retest measures. Significant differences were observed for all participants regarding distance for 6MWT. In the men’s and women’s sub-groups, there were only significant differences for distance for 6MWT in men.

Table 4 shows relative reliability (ICC) and absolute reliability (SEM, SEM%, SRD, and SRD%). Total sample ICC values were excellent (>0.90) for all participants and men and women sub-groups. The ICC for the whole sample was 0.94, while the ICC for the men’s subgroup was 0.91 and the women’s subgroup 0.96. Cronbach’s alpha was also obtained, the result being 0.95 for the whole sample (men’s sub-group 0.93 and women’s subgroup 0.96).

SEM% was 6.1 for all participants; SRD%, however, was 17. In the men’s sub-group, SEM% was around 6.1% and SRD% was around 17%. In the women’s sub-group SEM% was around 6.0 and SRD% was around 16.7%. The ICC was slightly better for the women’s sub-group.

The results obtained show that the 6MWT is sensitive in the Parkinson’s population, with a detection in the lower measurement error (SRD<17%).

Figure 1.

The Bland–Altman plots of the 6MWT. These plots indicate that the points outside the 95% LOA are less than 7.5%.

Figure 1.

The Bland–Altman plots of the 6MWT. These plots indicate that the points outside the 95% LOA are less than 7.5%.

4. Discussion

The 6MWT has proven to be a cornerstone in functional assessment across various pathologies [

36] and our findings confirm its applicability and excellent test-retest reliability in PD patients. The low SRD (≤17%) for the total sample indicates that a change in distance covered exceeding this percentage can be considered a true functional change, which is crucial for monitoring disease progression or the impact of therapeutic interventions in clinical practice. The comparable reliability between men and women further strengthens its universality within the PD population.

The excellent test-retest reliability obtained is particularly significant given that the test was conducted on a 20m × 3.5 m circuit. This design requires a substantially greater number of 180º turns than the standard protocol (≥30 m), which imposes a high motor and balance demand. In PD, the turning movement is a known precipitant of bradykinesia, difficulty in initiating movement, and freezing of gait, factors that typically increase intra-subject variability. However, the high ICC suggests that, even under this increased demand, the walking performance was highly reproducible. This supports the use of shorter circuits not only for evaluating aerobic endurance but also as an ecological and functional challenge that more faithfully simulates the mobility demands in restricted home and community environments, which is fundamental for fall prediction.

The mean distance covered in our study is consistent with the existing literature, approaching the values reported by Falvo and Earhart (391.6±99.9 m) in mild to moderate PD [

37] and those by Kobayashi et al. (340.8±110.9 m) in moderate PD [

21]. These studies, like ours, confirm the construct validity of the 6MWT as a measure of aerobic endurance and its association with key variables such as balance, fall predisposition, and gait efficiency (correlation with TUG and energy cost) [

38]. The variability observed in the individual results can be attributed, in addition to the clinical variables specific to PD (age, gender, disease stage) [

39], to non-motor factors, such as the participants’ level of prior physical activity and their psychological state [

23].

Despite the solidity of the findings, this study presents certain limitations. The inclusion of subjects exclusively in Hoehn and Yahr stages I–III requires caution when extrapolating the results to patients with more severe involvement. Furthermore, this investigation did not analyze the effect of medication on 6MWT performance. Therefore, future research should take these limitations into account. It would be of interest to conduct longitudinal studies to determine the evolution of functional capacity and the impact of interventions. Likewise, it is recommended to incorporate complementary measures during the test, such as oxygen consumption and heart rate. We believe this would provide a more complete picture of functional performance and the physiological response to exercise in patients with PD.

5. Conclusions

The 6MWT, performed on a 20×3.5 m rectangular circuit, demonstrated excellent test-retest reliability in patients with PD. This confirms its validity as an effective and reproducible tool for evaluating functional capacity and exercise endurance in this population.

Funding

The activity has been co-financed at 85% by the European Union, European Regional Development Fund, and the Regional Government of (GR24125). Managing Authority: Ministry of Finance.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the University of Extremadura data 01/30/2023 (reference number: 120/2022). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964, as revised in 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants signed the informed consent form.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Parkinson Associations of Almendralejo, Mérida, Salamanca, Talavera de la Reina and Villanueva de la Serena for their collaboration in recruiting participants for this study. We would also like to thank James McCue for revising the text to English.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Lotankar, S. , Prabhavalkar KS, Bhatt LK. Biomarkers for Parkinson’s Disease: Recent Advancement. Neurosci Bull 2017, 33, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, D. T, Jenner P. Parkinson disease: From pathology to molecular disease mechanisms. Free Radic Biol Med 2013, 62, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolosa, E. , Garrido A, Seppi K, Tuite P, Rascol O, Albanese A et Al. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2021, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerri, S, Mus L, Blandinie F. Parkinson’s Disease in Women and Men: What’s the Difference? J Parkinsons Dis 2019, 9, 501–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liepelt-Scarfone, I. , Gräber S, Maetzler W, Müller K, Oing C, Gaenslen A et Al. Clinical characteristics with an impact on ADL functions of PD patients with cognitive impairment indicative of dementia. PLoS One 2013, 8, e82902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos-Martínez, L. E, Torres-Maldonado M, Hernández-Salas JA, Cruz-Medina E, Murillo-Jáurgui CX, Velasco-Benítez D.[Within-subject variability of the 6-minute walk test]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 2022, 60, 26–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, P, Gabaude C, Bulot V, Passerieux Y, Le Bot C, Couallier V, et al. Six minutes walk test for individuals with schizophrenia. Disabil Rehabil 2015, 37, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murillo-Jáuregui, C.X. , Zavaletea-Canchari F, Vargas-González Z, Pantoja-Salazar E, Huamán-Guerrero G, Santos-Martínez LE. , [Six minute walk test in young native high altitude residents]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 2023, 61, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco Pérez, J. J, Morchón C, Herrero-Cortina D, Martín-García C, Cueva B, Blanco-Alvarez A et al. The 6-Minute Walk Test as a Tool for Determining Exercise Capacity and Prognosis in Patients with Silicosis. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed) 2019, 55, 88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Rabinovich, R.A. , Vilaró J, Roca J. [Evaluation exercise tolerance in COPD patients: the 6-minute walking test]. Arch Bronconeumol 2004, 40, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Meléndez A, De la Parra-Vásquez D, Marín-Ávila JF, Olivos-Meza A, Vázquez-Castañeda F, Gallegos-Cruz V- [Correlation between the six-minute walk test and maximal exercise test in patients with type ii diabetes mellitus]. Rehabilitacion (Madr) 2019, 53, 2–7.

- González-Díaz, S.N. , Galindo-García G, De la Cruz-Cano G, Valdés-de la Peña AE, González- Hernández S. [Evaluation of functional capacity by 6-minute walk test in children with asthma]. Rev Alerg Mex 2017, 64, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco I, Alcaraz V, Alcaraz R, Gea J. [Peak oxygen uptake during the six-minute walk test in diffuse interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension]. Arch Bronconeumol 2010, 46, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, P, Salzman SH. Six-Minute Walk Test: Clinical Role, Technique, Coding, and Reimbursement. Chest 2020, 157, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto S, Nagaya N, Saton T, Kyotani S, Sakamaki F, Fujita M, et al. Clinical correlates and prognostic significance of six-minute walk test in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. Comparison with cardiopulmonary exercise testing. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000, 161 Pt 1, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerda, AL. Manejo del trastorno de marcha del adulto mayor. Revista Médica Clínica Las Condes 2014, 25, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen T, Seney M. Test-retest reliability and minimal detectable change on balance and ambulation tests, the 36-item short-form health survey, and the unified Parkinson disease rating scale in people with parkinsonism. Phys Ther 2008, 88, 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambela, M. C, Rodrigues AS, De Siqueira AF, De Cassia T, Lima I, Costa IP, et al. Correlation of 6-min walk test with left ventricular function and quality of life in heart failure due to Chagas disease. Trop Med Int Health 2017, 22, 1314–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P. Test 6-minute walk or ergospirometry in the treatment of cardiac resynchronization: friend or foe? Med Clin (Barc) 2017, 148, 95. [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad D, Sáncehez-López M, Milla P, González-Sánchez G, Ramírez-Vélez R, Izquierdo M, et al. [Response to the six-minute walk test in children with cardiovascular risk]. Rev Chil Pediatr 2020, 91, 561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi E, Himuro N, Takahashi M. Clinical utility of the 6-min walk test for patients with moderate Parkinson’s disease. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research 2017, 40, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATS statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 166, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Lipkin, D. P, Scriven AJ, Poople-Wilson PA, Sutton GC. Six minute walking test for assessing exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986, 292, 653–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tröster, A.I. A Précis of Recent Advances in the Neuropsychology of Mild Cognitive Impairment(s) in Parkinson’s Disease and a Proposal of Preliminary Research Criteria. J Int Neuropsychological Society 2011, 17, 393–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walter, S. D, Eliasziw M, Donner A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med 1998, 17, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology 1967, 17, 427–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardinal, B. J,Esters J, Cardinal MK. Evaluation of the revised physical activity readiness questionnaire in older adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996, 28, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-López M, Fornari E, Milla P, Seral-Muñoz M, Zarza-Perez P, Piqueras-Sanchiz F, et al. Construct validity and test-retest reliability of the International Fitness Scale (IFIS) in Spanish children aged 9-12 years. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2015, 25, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Peto V, Greenhal R, Hyman N. The Parkinson’s Disease Questionnaire (PDQ-39): development and validation of a Parkinson’s disease summary index score. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yardley L, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen C, Piot-Ziegler E, Todd C. Development and initial validation of the Falls Efficacy Scale-International (FES-I). Age Ageing 2005, 34, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979, 86, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T. K, Li MY. A Guideline of Selecting and Reporting Intraclass Correlation Coefficients for Reliability Research. J Chiropr Med 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portney L, Watkins M. Construct validity. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. Prentice Hall Health. New Jersey, USA, 2000:87-91.

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J. M, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986, 1, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks D, Solway S, Gibbons WJ. ATS statement on six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003, 167, 1287. [CrossRef]

- Falvo, M. J, Earhart GM. Six-minute walk distance in persons with Parkinson disease: a hierarchical regression model. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2009, 90, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enright PL, Sherrill DL. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998, 158 Pt 1, 1384–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos M, Lemos M, Ligeiro M, Nogueira S, Basto A, Silva P. Test-retest and inter-rater reliability and construct validity of the 2-minute step test in individuals with Parkinson’s disease. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2024, 40, 2033–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).