1. Introduction

The term “soilless culture” generally refers to any method of growing plants without using soil as a rooting medium (Lal, 2017; Savvas, 2003). Presently, the soilless culture systems (SCS) have emerged as a pivotal technological component in modern greenhouse operations, primarily due to their distinct advantages. A defining strength of SCS lies in its ability to liberate crops from dependence on soil—a natural medium characterized by heterogeneity, pathogen harboring, tendency to deteriorate under monoculture practices, and potential infertility, salinity, or sodicity. The independence from the soil as a rooting medium in SCS enables optimization of both physical and chemical characteristics in the root environment and a more efficient control of pathogens without the need to apply soil fumigation (Savvas & Gruda, 2018). This achieves high yields at reasonable costs, with low pesticide use and premium quality.

Containerized plant production poses two primary challenges to healthy root development. First, unlike natural soil profiles, the shallow growing medium layer in containers rapidly saturates during irrigation. Second, the limited volume of small containers restricts water-holding capacity between irrigation events (Bunt, 2012). Fundamentally, an effective growing medium must possess a physical structure capable of maintaining an optimal air-water balance during and between irrigation events, preventing root asphyxia and drought stress (Caron & Nkongolo, 1999; Fonteno, 1993). Soil’s failure to sustain this balance within such constrained volumes has been a key catalyst for the development of soilless substrates. Indeed, these substrates represent a breakthrough innovation, enabling growers to precisely regulate water, air, and nutrient delivery to plant roots while excluding soil-borne pathogens (Raviv et al., 2002).

Potting media are composed of components that supply air, water, and nutrients to support plant growth (Mariyappillai & Arumugam, 2021). The distribution of air, water, and solids within a container medium is influenced by multiple factors, including pore space, bulk density, substrate particle size distribution, container height, and media settling characteristics. Both inorganic and organic substrates are used as growing media: inorganic options include expanded clay, glass wool, gravel, perlite, pumice, rock wool, sand, sepiolite, vermiculite, volcanic tuff, zeolite, as well as synthetic materials like foam mats, hydrogels, and plastic foams; organic materials encompass bark, coconut coir, coco soil, fleece, marc, peat, raffia bark, rice husk, sawdust, and wood chips. To meet plant growth requirements, growing media must satisfy diverse criteria related to physical, chemical, hydrological, and biological properties (Nelson, 2011). Nonetheless, no single substrate or mixture can universally satisfy the needs of all plant species under all conditions (Di Lorenzo et al., 2013; Gruda, 2011).

In substrate-based cultivation systems, the particle size distribution of the growing medium (GM) and container dimensions must be carefully selected to balance water accessibility and aeration within the root zone (Savvas & Gruda, 2018). Notably, the substrate layer height must be sufficiently large to facilitate adequate drainage and aeration, determined by the substrate’s hydraulic properties (Heller et al., 2015). Generally, fine-particle-dominated GM performs optimally when contained in tall, narrow vessels, whereas coarser substrates are better suited to shallow bags or troughs to ensure adequate water supply (Savvas, 2007).

In traditional soil cultivation, plant root systems have unrestricted volume, whereas in soilless cultivation, root growth is constrained by container size, leading to varying degrees of root system limitation. Root restriction, as a form of abiotic stress, exerts both direct and indirect influences on plant morphology and physiology (Gao et al., 2023). By adjusting container dimensions appropriately, this technique can enhance plant quality and container utilization efficiency. Currently, root restriction has been effectively applied to diverse crops, including wolfberry (He et al., 2022), chili peppers (Zakaria et al., 2020), and grapes (Xu et al., 2021). Empirical studies have demonstrated that in root-restricted tomato plants, primary roots primarily proliferate toward the container base, producing numerous shorter lateral roots (LRs) that densely fill the entire volume to form a root mat (Peterson et al., 1991). This configuration enhances gas exchange efficiency by mitigating adverse effects of oxygen deficiency while improving nutrient uptake capacity (Balliu et al., 2021). Although larger container sizes typically correlate with higher yields (Balliu et al., 2021), emerging evidence highlights that root restriction elevates levels of primary metabolites, such as soluble sugars, amino acids, and lipids (Leng et al., 2021), and secondary biomolecules including carotenoids, flavonoids, phenolic acids, and alkaloids in fruits (Gao et al., 2023). These metabolic enhancements are conducive to improving fruit quality and bioactive compound content (Leng et al., 2022).

Studies have shown that soilless organic growing media have distinct ecological niches for diverse bacterial communities, which exhibit temporal functional stability (Grunert et al., 2016). Newly prepared or sterilized growing media often lack a diverse and competitive microbiome (Grunert et al., 2016; Postma, 2010; Raviv et al., 2019), whereas natural soil typically harbors up to 107–109 bacterial colony-forming units (CFU) and 104–106 culturable fungal propagules per gram of soil (Alexander, 1978). It has been hypothesized that organic peat-based growing media used in tomato cultivation systems are primarily colonized by fungi, Actinomycetes, and Trichoderma species (Koohakan et al., 2004; Sammar Khalil & Alsanius, 2001), while mineral-based growing media are dominated by bacterial communities (Grunert et al., 2020; Vallance et al., 2011). In the rhizosphere, bacteria emerge as one of the most abundant and diverse microbial groups. They play pivotal roles in nutrient cycling processes including nitrogen fixation, phosphorus solubilization, and potassium activation, while also contributing to disease suppression and plant growth promotion through the synthesis of various hormones and enzymes (Chepsergon & Moleleki, 2023; Kong & Liu, 2022). Fungi are integral to this ecosystem: symbiotic mycorrhizal fungi form mutually beneficial associations with plant roots to enhance water and nutrient uptake, whereas free-living fungi facilitate the decomposition of organic matter, further driving nutrient cycling (Grondin et al., 2024; Thepbandit & Athinuwat, 2024).

Although bacterial and fungal microbiota have been extensively investigated across diverse environments and plant species, the impacts of a stress-inducing technique, specifically root-zone restriction on tomatoes, remain largely uncharacterized. Here, we hypothesize that root-zone restriction modulates the assembly of plant-associated rhizosphere bacterial and fungal communities. This technique enhances root development and consequently promotes the enrichment of key bacterial and fungal taxa that correlate with both the depth of root restriction and the substrate type. Elucidating these microbial dynamics will advance our understanding of the “microbial terroir” of tomatoes under root-zone-restricted cultivation. Our central objective was to investigate how root-zone restriction shapes bacterial and fungal community structures across different substrates, as well as its association with fruit quality and yield.

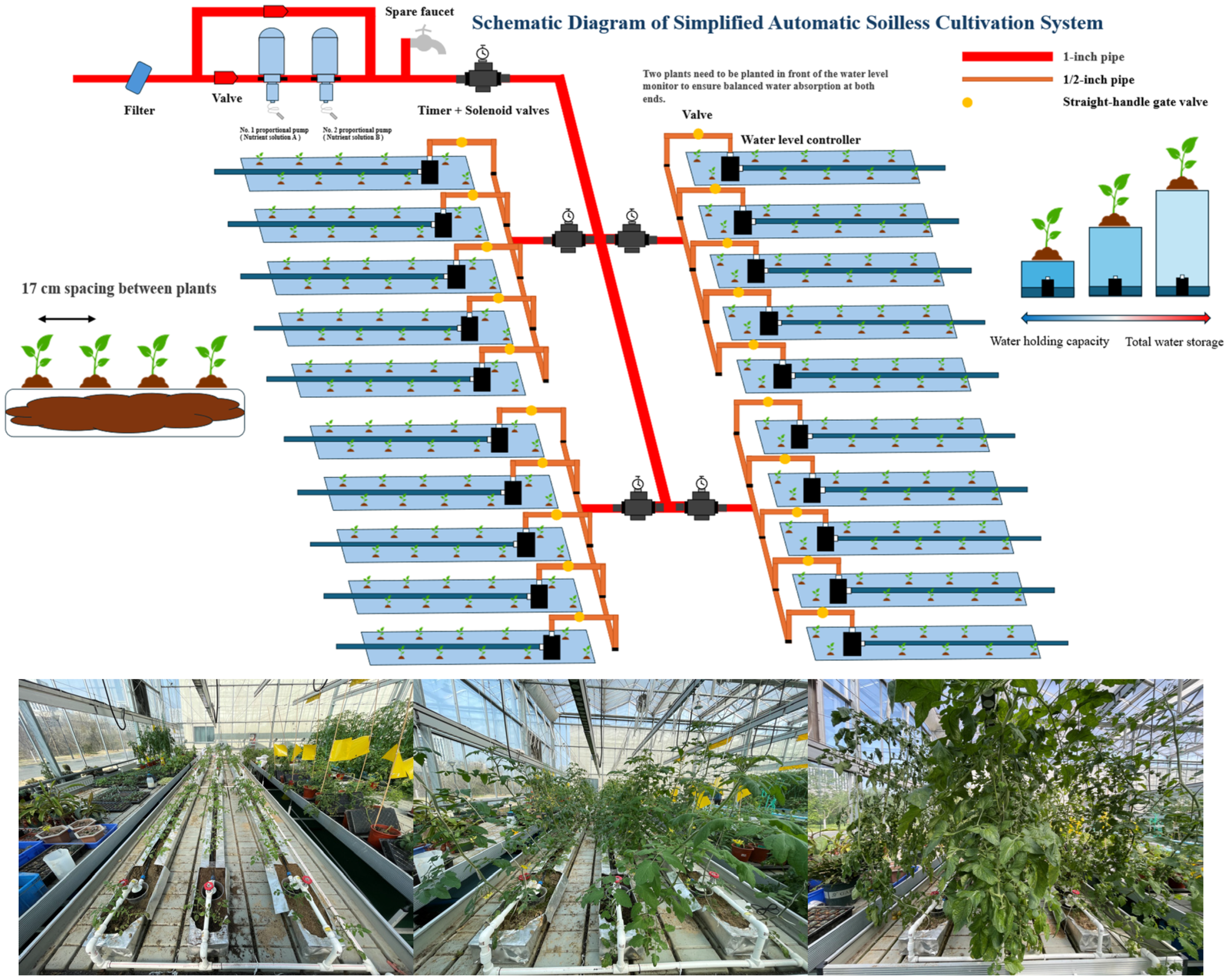

The experiment utilized peanut shell fermentation substrate, sand and soil in combination with a simplified soilless automated cultivation system (SAS) to impose different levels of root restriction on tomato plants. The study aims to investigate the effects of varying root restriction levels on tomato growth, fruit quality, and rhizosphere microbial communities.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of simplified automatic soilless cultivation system.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of simplified automatic soilless cultivation system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Cultivation Facilities

The tested plant variety is the cherry tomato “Marinka”. The cultivation facility used is Simplified Automatic Soilless Cultivation System (SAS). The cultivation substrates include fermented peanut shell substrate, sand, and soil. The soil sample was collected from the Agricultural Experiment Station of Zijingang Campus, Zhejiang University in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China (coordinates: 120°4′54.1164″E, 30°18′10.494″N). The nutrient solution used is Hoagland nutrient solution. The cultivation troughs are made of aluminum sheets (dimensions: length × width = 280 cm × 17 cm). Within each cultivation trough, 8 cm, 16 cm, and 24 cm of fermented peanut hull substrate, sand, and soil were filled respectively (with volumes of approximately 38.08 dm3; 76.16 dm3; and 114.24 dm3). The system is equipped with solenoid valves for timed daily irrigation. Each cultivation trough is installed with a water level controller and drip irrigation tape, which automatically stops drip irrigation when the water level at the bottom of the trough exceeds 2 cm.

2.2. Experimental Design and Sample Collection

The experiment was conducted in the Greenhouse A of the Agricultural Experiment Station on Zhejiang University’s Zijingang Campus in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, from January 14, 2024, to June 14, 2024. Each cultivation trough was planted with 12 tomato plants at three different heights: 8 cm, 16 cm, and 24 cm. Each height level was filled with peanut shell substrate, sand, or soil, respectively. An orthogonal experimental design was adopted, with 3 replications for each treatment. Irrigation was adjusted based on weather conditions and the water requirements of tomato plants at different growth stages, with consistent water and fertilizer application across all treatments. From the seedling stage to the initial fruiting stage, drip irrigation was applied once daily; from the initial fruiting stage to the full fruiting stage, it was applied three times daily. The water level at the bottom of each cultivation trough was regulated using a water level controller.

During the peak fruiting stage of tomatoes (79 to 80 days after transplanting), physiological indicators such as plant height, stem diameter, and chlorophyll content were measured. For each treatment, 12 plants were measured, and their average values were calculated. Five fruit clusters were retained per treatment, and yield was recorded after fruit ripening. During the peak fruiting stage, tomatoes of consistent maturity from the same cluster were randomly selected to determine soluble sugar content, soluble protein content, and lycopene content. After the vines were uprooted, root activity of the underground plant parts in each treatment was measured. Following tomato harvest, roots were excavated, rhizosphere growing media samples were collected and stored at -80°C, DNA was extracted for amplicon sequencing, and the sequencing data were used for microbial community analysis.

2.3. Measurement of Plant and Soil Parameters

2.3.1. Growth Parameters Measurement

Tomato plant height was measured using a ruler, with 12 plants measured and the average value calculated. Stem diameter was measured using a vernier caliper at three points per plant (1 cm below each inflorescence), with 12 plants sampled and averaged. At the harvesting period, three uniformly growing tomato plants were selected. After excavating the entire root system, the residual substrate was rinsed off with water and blotted dry with gauze. Root activity is determined by the triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) method (J. Liu et al., 2014). Chlorophyll content in leaves was determined by acetone and anhydrous ethanol extraction followed by spectrophotometric analysis (Palta, 1990).

2.3.2. Determination of Fruit Quality and Yield

After fruit ripening, statistically record the yield data for all treatments. The lycopene content was determined by UV spectrophotometry (Rao et al., 1998). Soluble protein content was measured using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 staining method (Snyder & Desborough, 1978). Soluble sugar content was analyzed via the anthrone colorimetric method (Y. Zhang et al., 2023). Each tomato plant was allowed to retain 5 fruit clusters, and the yield per plant was weighed using a balance. For each treatment, 12 plants were evaluated.

2.3.3. Determination of Bulk Density, Water Holding Capacity, and Total Water Storage Capacity

Substrate bulk density, water holding capacity, and total water storage capacity were determined by the ring knife method (Erbach, 1987). After selecting appropriate sampling points, the cutting ring was vertically driven into the soil surface until fully embedded. The surrounding soil was carefully excavated with a shovel to remove the cutting ring assembly. The upper cutting ring holder was detached, and both ends of the soil column were trimmed with a soil knife to ensure a fixed volume (five replicates for surface soil samples). The entire soil sample from the cutting ring was then transferred to a pre-weighed aluminum box. The combined weight of the box and fresh soil sample was recorded. Subsequently, the sample was oven-dried at 105°C until reaching constant weight, after which the weight of the dried soil and aluminum box was measured.

2.3.4. Determination of Bacterial and Fungal Communities in Tomato Rhizosphere

After tomato harvest, the root system was excavated, and rhizosphere soil was collected and stored at -80°C for microbial community analysis. Total genomic DNA was extracted from soil samples using the conventional cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method. The integrity and purity of DNA were evaluated via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, while DNA concentration and purity were assessed using NanoDrop One. The primers used for amplification were: Bacterial V5V7-1 region (forward primer sequence: AACMGGATTAGATACCCKG, reverse primer sequence: ACGTCATCCCCACCTTCC); Fungal ITS2-1 region (forward primer sequence: GCATCGATGAAGAACGCAGC, reverse primer sequence: TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC). For PCR amplification and product analysis, genomic DNA was used as the template. Based on the target sequencing regions, primers with barcodes and Premix Taq (TaKaRa) were employed. PCR products were quantified using GeneTools Analysis Software (Version 4.03.05.0, SynGene) and pooled in equimolar ratios. The pooled products were purified using the E.Z.N.A.® Gel Extraction Kit to recover target DNA fragments. Subsequent library preparation followed the NEBNext® Ultra™ DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® protocol. The prepared libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq platform. Raw image data from sequencing were processed via base calling to generate raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files), which included sequence information and corresponding quality scores for each read.

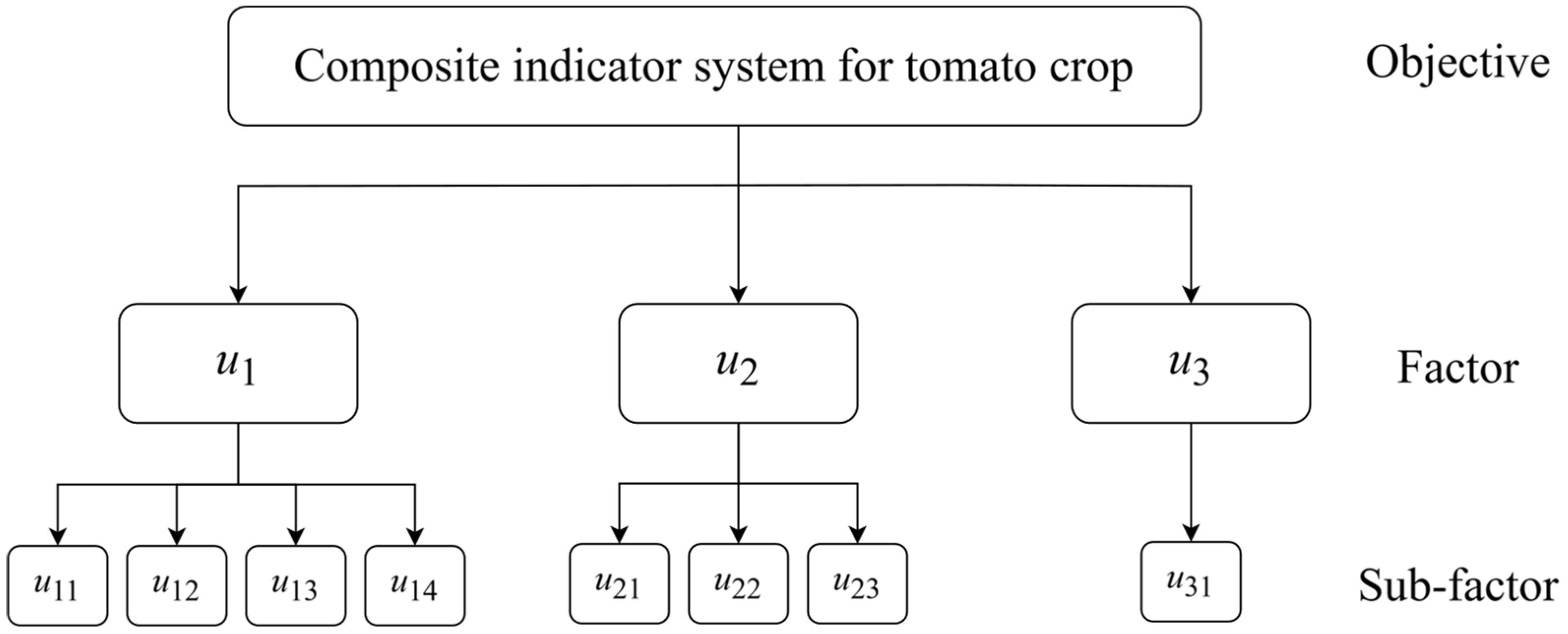

2.4. Composite Tomato Indicator Using TOPSIS

2.4.1. Establishment of Factors and Subfactors

(1) The tomato indicators were growth condition, fruit quality, yield.

where u1, u2, u3, and u4 are growth condition, fruit quality, and yield., respectively.

(2) Each factor was composed of subfactors. The growth condition indicators (u

1) were plant height (cm), stem diameter (cm), total chlorophyll content (mg/g), and root activity [mg/ (g·h)]. The fruit quality indicators (u

2) were soluble sugar (mg/g), soluble protein (mg/g), and lycopene (μg/g) content. The yield indicators (u

3) was single plant yield (kg/plant).

where u

11 is plant height, u

12 is stem diameter, u

13 is total chlorophyll content, u

14 is root activity; u

21 is soluble sugar content, u

22 is soluble protein content, u

23 is the lycopene content, u

31 is single plant yield.

Figure 2.

Composite indicator system for tomato crops in which u1, u2, u3 are respectively growth condition, fruit quality, and yield. The subfactors are the following: u11 is plant height, u12 is stem diameter, u13 is total chlorophyll content, u14 is root activity, u21 is soluble sugar content, u22 is soluble protein content, u23 is lycopene content, u31 is single plant yield.

Figure 2.

Composite indicator system for tomato crops in which u1, u2, u3 are respectively growth condition, fruit quality, and yield. The subfactors are the following: u11 is plant height, u12 is stem diameter, u13 is total chlorophyll content, u14 is root activity, u21 is soluble sugar content, u22 is soluble protein content, u23 is lycopene content, u31 is single plant yield.

2.4.2. Determination of Factor Weights

To eliminate the influence of different dimensions of factors, the measurement values of all tomato indicators were normalized. The weights of the factors were determined through the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP).

2.4.3. Composite Indicators of Tomato Based on TOPSIS

Tomato composite indicators were evaluated by TOPSIS, optimal substrate type and root restriction level combination for growth, fruit quality, and yield were obtained.

Constructing the decision matrix X.

where

represents the

th treatment, and (

represents the

th subfactor.

The standardized matrix is denoted as

, and each element in

is defined as

where

is the normalized

.

Determining the positive ideal solutions (

) and the negative ideal solutions (

):

Calculating the distance (

) between

and

:

Calculating the distance (

) between

and

:

where

is the weight obtained by analytic hierarchy process.

Calculating the composite indicators (

of all treatments.

where

. Tomato has an optimal composite indicator for growth, fruit quality, and yield when

is close to 1. Ranks are obtained based on

.

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis of tomato physiological indicators and substrate properties was performed using SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and Microsoft Excel 2019. One-way ANOVA was used for testing, and multiple comparisons were conducted using Duncan’s method (p < 0.05). Plotting was performed using GraphPad Prism 10. The correlation network heatmap was generated using R 4.5.0. The TOPSIS comprehensive score was calculated using MATLAB 2024 (MathWorks, USA). Microbial community analysis was performed using EasyAmplicon (Liu et al., 2023) for batch processing of sequencing data, with bacterial functional annotation via FAPROTAX (Louca et al., 2016)and fungal functional annotation using FUNGuild (Nguyen et al., 2016). LEfSe analysis was conducted through the ImageGP 2 online platform (Chen et al., 2024), network analysis utilizes ggClusterNet (Wen et al., 2022).

3. Results

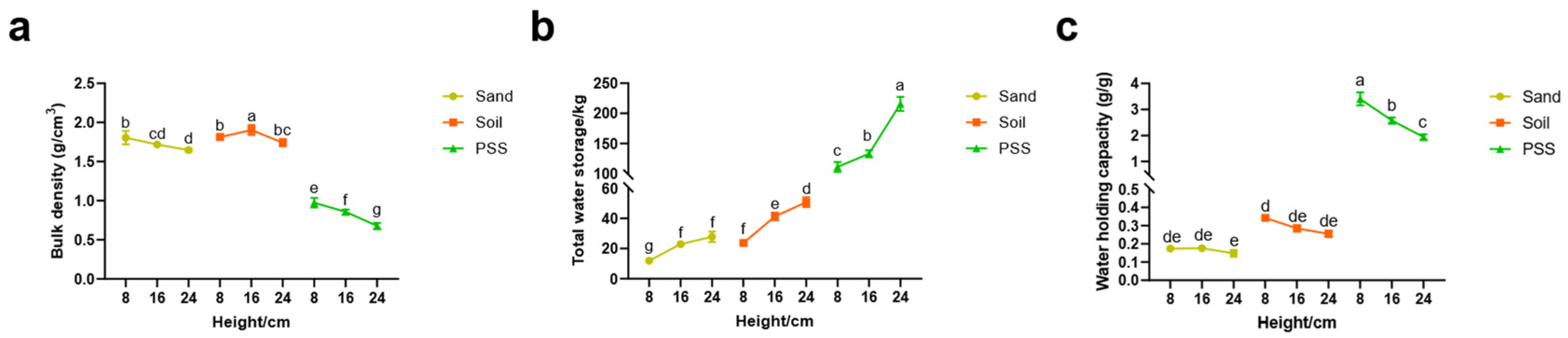

3.1. Substrate Physical Properties

In the peanut shell substrate (PSS), both bulk density and water holding capacity decreased with increasing substrate height. In contrast, soil and sand exhibited no significant reduction in these properties as height increased (

Figure 3a,c). Across all three substrates, total water storage capacity significantly increased with greater substrate height (

Figure 3b). The total water storage of 8cm PSS was approximately 51.6% of that of 24cm PSS. At the 8 cm height, bulk density measurements were 1.78 g/cm

3 (soil), 1.73 g/cm

3 (sand), and 0.78 g/cm

3 (PSS). While soil and sand showed similar bulk densities, PSS was significantly lower than both. Notably, PSS demonstrated substantially higher water holding capacity than soil and sand: at 8 cm height, values reached 0.34 g/g (soil), 0.17 g/g (sand), and 3.41 g/g (PSS). These results indicate that PSS is markedly lighter than soil or sand in containers of equivalent volume yet possesses far superior water absorption capacity. Even at shallow root-restricting heights or in limited container volumes, PSS can retain 200%–300% of its own weight in water.

3.2. Tomato Phenotype

To evaluate the effect of root restriction on tomato growth status, we constructed three cultivation troughs of different heights filled with soil, sand, and peanut shell substrate (PSS), with average volumes per plant of 3.17 dm3, 6.34 dm3, and 9.51 dm3, respectively.

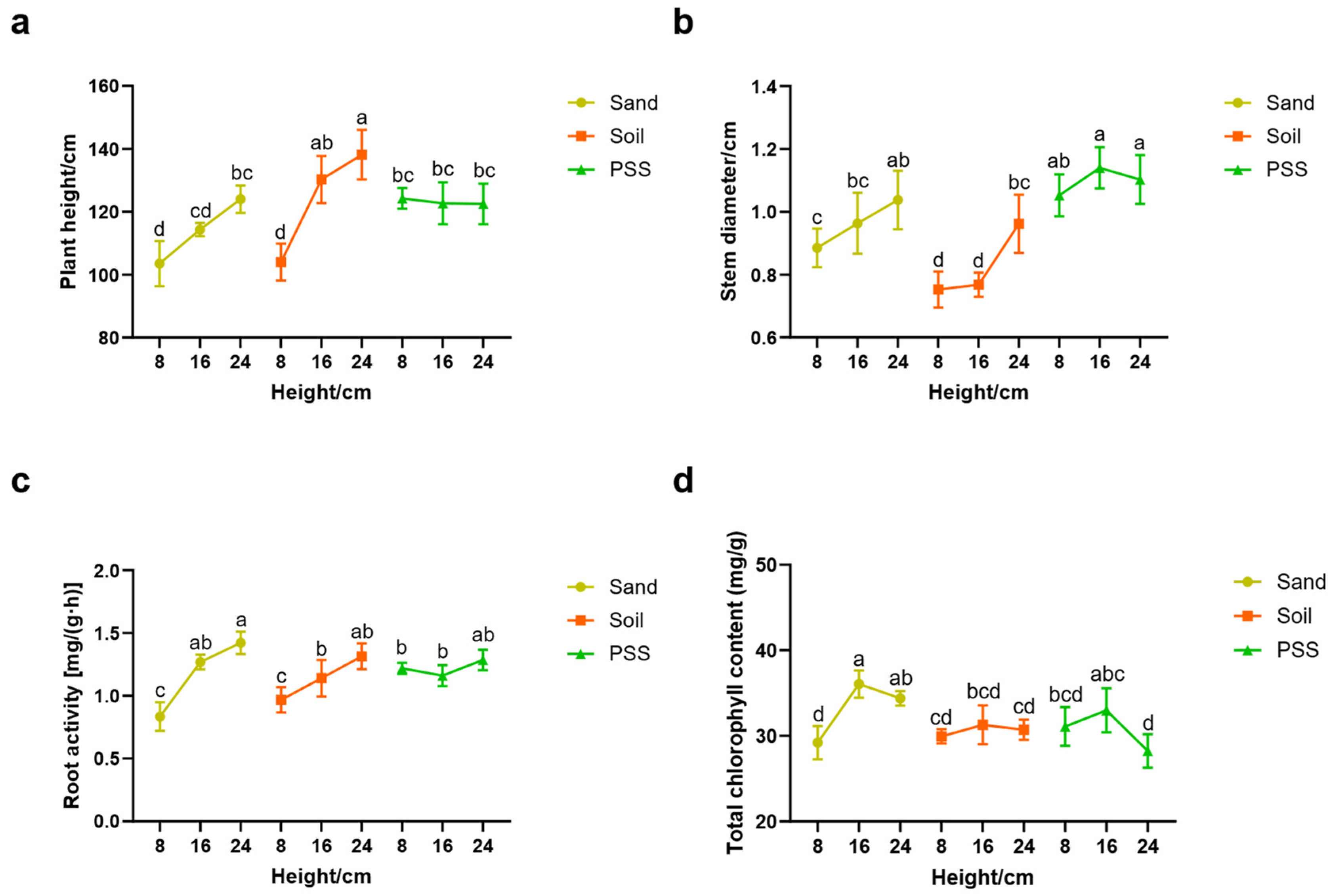

3.2.1. Growth Status

When soil or sand was used as the substrate, tomato plant height, stem diameter, and root activity increased significantly with rising substrate height. In contrast, cultivation in peanut shell substrate (PSS) resulted in no significant changes in these vegetative growth parameters across varying substrate heights (

Figure 4a–c). Total chlorophyll content in leaves remained stable with increasing substrate height in soil-based cultivation (

Figure 4d). At the 8 cm root-restriction height, tomatoes grown in soil and sand exhibited markedly lower plant height, stem diameter, and root activity compared to those in PSS. However, these differences progressively diminished as substrate height increased. Specifically, at 8 cm height, average stem diameters were 0.75 cm (soil), 0.88 cm (sand), and 1.05 cm (PSS). These results indicate that root restriction suppresses vegetative growth in soil and sand substrates, with more pronounced inhibition in soil than sand at minimal heights.

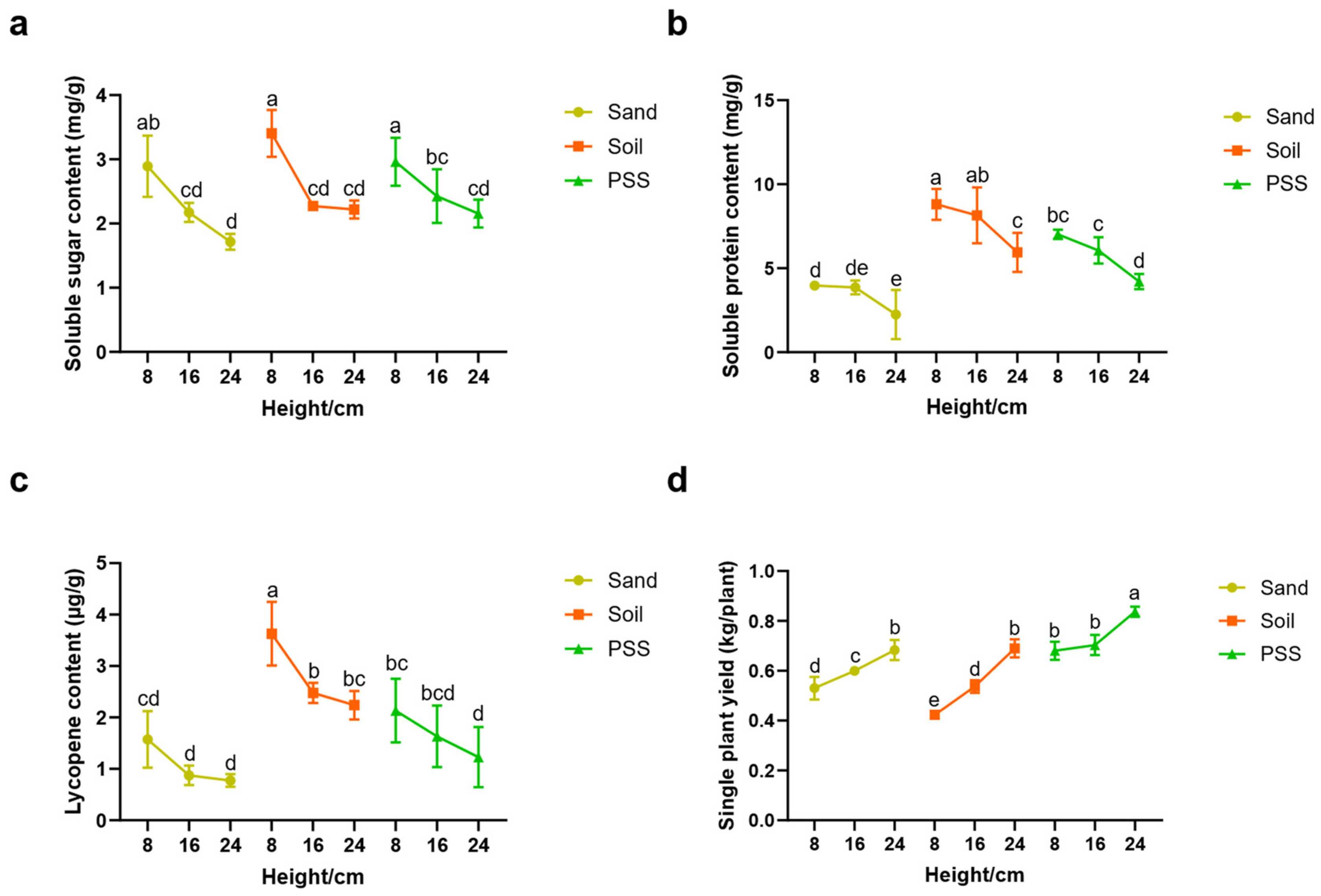

3.2.2. Fuit Quality and Yield

In tomato cultivation using soil, sand, or peanut shell substrate (PSS), the contents of soluble sugar, soluble protein, and lycopene in the fruits decreased as substrate height increased (

Figure 5a–c). In contrast, single-plant yield increased with greater substrate height (

Figure 5d). 8 cm root-restriction height increased soluble sugar (+69.01%, 53.84%, 37.67%), protein (+77.23%, 48.14%, 66.51%) and lycopene (+100.03%, 62.33%, 74.59 %) than that of 24cm height in sand, soil and PSS, respectively but reduced single-plant yield by 28.30% (sand), 64.28% (soil), 22.06% (PSS). At the 8 cm root-restriction height, soil-cultivated tomatoes exhibited significantly higher levels of soluble protein and lycopene compared to those grown in PSS or sand. Regarding yield, tomatoes in PSS at 8 cm height produced 28.30% and 61.90% higher single-plant yield than those in sand and soil. These results indicate that the choice of cultivation substrate significantly influences tomato fruit quality and yield. Root restriction imposed by reducing trough height enhanced fruit quality but reduced yield, an effect particularly pronounced in soil and sand.

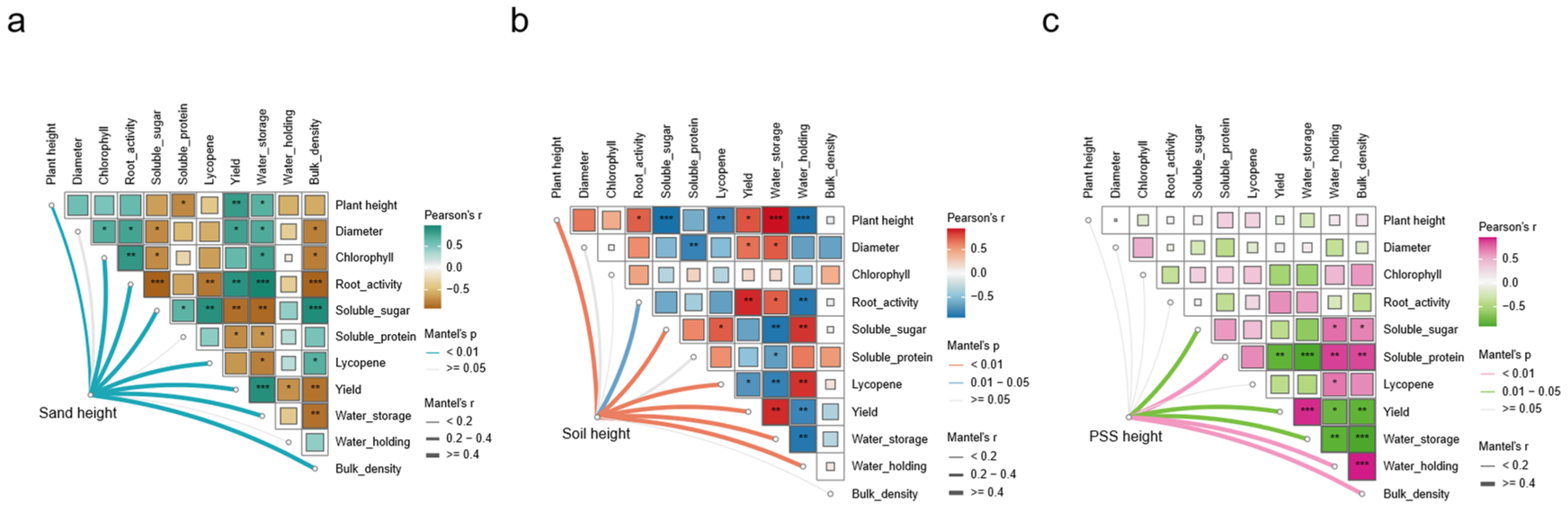

3.3. Multivariate Correlation Analysis of Root-Restriction Height Effects

When soil or sand served as substrates, tomato growth parameters (plant height, stem diameter), fruit quality, yield, and substrate properties were significantly affected by changes in substrate height (

Figure 6a,b). In contrast, cultivation in peanut shell substrate (PSS) resulted in no significant response of tomato plant height, stem diameter, total chlorophyll content, or root activity to varying substrate heights. However, substrate height still markedly influenced PSS fruit quality, yield, and physical properties (

Figure 6c). Specifically, tomato growth in soil and sand exhibited a significant positive correlation with substrate height. Across all substrates, substrate height was negatively correlated with fruit quality but positively correlated with yield. Additionally, water storage capacity showed a positive correlation with yield. Critically, variations in PSS height had no significant impact on tomato growth, indicating that PSS can sustain normal growth even at minimal root-restricting heights. Conversely, soil and sand imposed growth inhibition under reduced substrate heights. These results demonstrate that PSS, as an effective green compost, maintains favorable physical structure in the SAS system due to its low bulk density and high water-holding capacity, thereby balancing aeration and water retention during irrigation cycles and mitigating risks of root asphyxiation and drought stress.

3.4. Comprehensive Evaluation of Tomato Quality and Yield Improvement Based on TOPSIS Method

TOPSIS scores indicate that tomatoes cultivated in soil at a height of 24 cm, sand at a height of 8 cm, and peanut shell substrate (PSS) at 8 cm achieved the highest comprehensive scores within their respective substrates, with ranking orders of 2, 7, and 1 respectively. When used as SAS cultivation substrates, the comprehensive scores under different root-restricting heights followed the order: PSS > soil > sand (

Table 1).

3.5. Rhizosphere Microorganisms

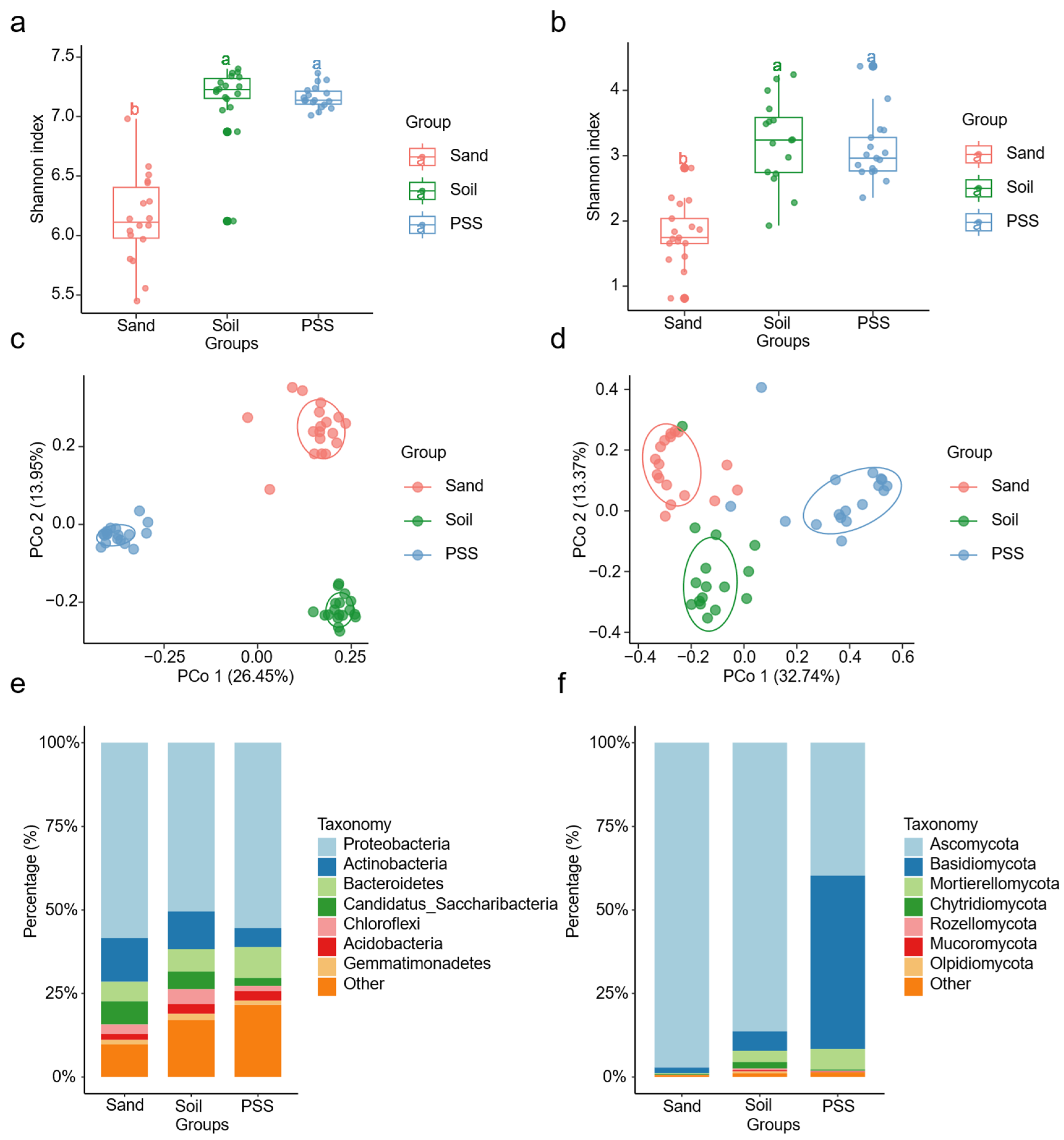

3.5.1. Microbial Diversity and Relative Abundance Under Different Substrates

Changes in cultivation substrates significantly altered the α- and β-diversity of bacterial and fungal communities in the tomato rhizosphere. The Shannon index of both bacterial and fungal communities was significantly higher in soil and peanut shell substrate (PSS) than in sand (

Figure 7a,b). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) revealed distinct compositional differences in rhizosphere microbial communities across substrates (

Figure 7c,d). At the phylum level, bacterial communities in all three substrates were dominated by

Proteobacteria,

Actinobacteria,

Bacteroidetes,

Candidatus_Saccharibacteria,

Chloroflexi,

Acidobacteria, and

Gemmatimonadetes (

Figure 7e). For fungi,

Ascomycota predominated in soil (86.34%) and sand (97.22%), whereas PSS comprised

Ascomycota (39.69%) and

Basidiomycota (51.93%). Notably, the relative abundances of

Basidiomycota and

Mortierellomycota in PSS significantly exceeded those in soil and sand (

Figure 7f). These results demonstrate that soil and PSS supported similar α-diversity levels in rhizosphere bacterial and fungal communities, both significantly higher than sand, while fungal community composition varied substantially among substrates.

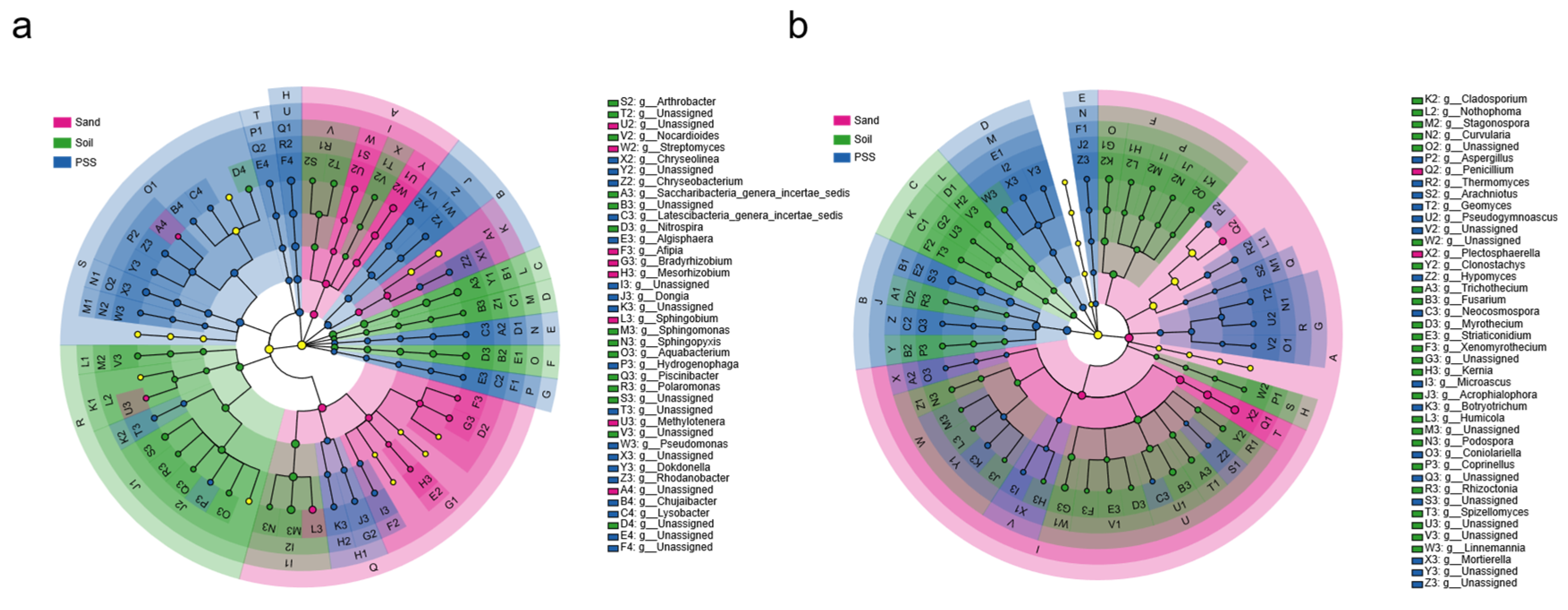

3.5.2. LEfSe (Linear Discriminate Analysis Effect Size) Analysis

Among the three substrates, compositional variations in the rhizosphere microbiome were primarily driven by significant shifts in the relative abundances of 9 specific bacterial phyla and 5 fungal phyla (Linear discriminate analysis effect size “LEfSe”, LDA score > 2, Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.05). At the genus level, we identified 14 specific markers in rhizosphere bacteria from soil, 8 in sand, and 17 in peanut shell substrate (PSS). For rhizosphere fungi at the genus level, 24 specific markers were identified in soil, 2 in sand, and 16 in peanut shell substrate (PSS). We noted that Sphingomonas (3.2%), Saccharibacteria_genera_incertae_sedis (2.2%), Nocardioides (1%), and Fusarium (2.4%) were indicator genera in soil; Methylotenera (1.4%), Penicillium (3.1%), and Plectosphaerella (5.2%) were indicator genera in sand; and Aspergillus (5.5%), Microascus (1.4%), and Mortierella (1.8%) were indicator genera in PSS. Notably, among the 16 marker genera detected in PSS rhizosphere fungi, they accounted for 12.5% of the relative abundance, with Aspergillus having the highest abundance at 5.5%. In sand rhizosphere fungi, the 2 detected marker genera accounted for 8.3% of the relative abundance, with Penicillium contributing 3.1% and Plectosphaerella contributing 5.2%. In summary, these results indicate that substrate properties shaped the bacterial and fungal communities inhabiting the root zone by selecting specific microbial taxa.

Figure 8.

Indicator rhizosphere microorganisms of tomato under different substrates. a: bacteria, b: fungi.

Figure 8.

Indicator rhizosphere microorganisms of tomato under different substrates. a: bacteria, b: fungi.

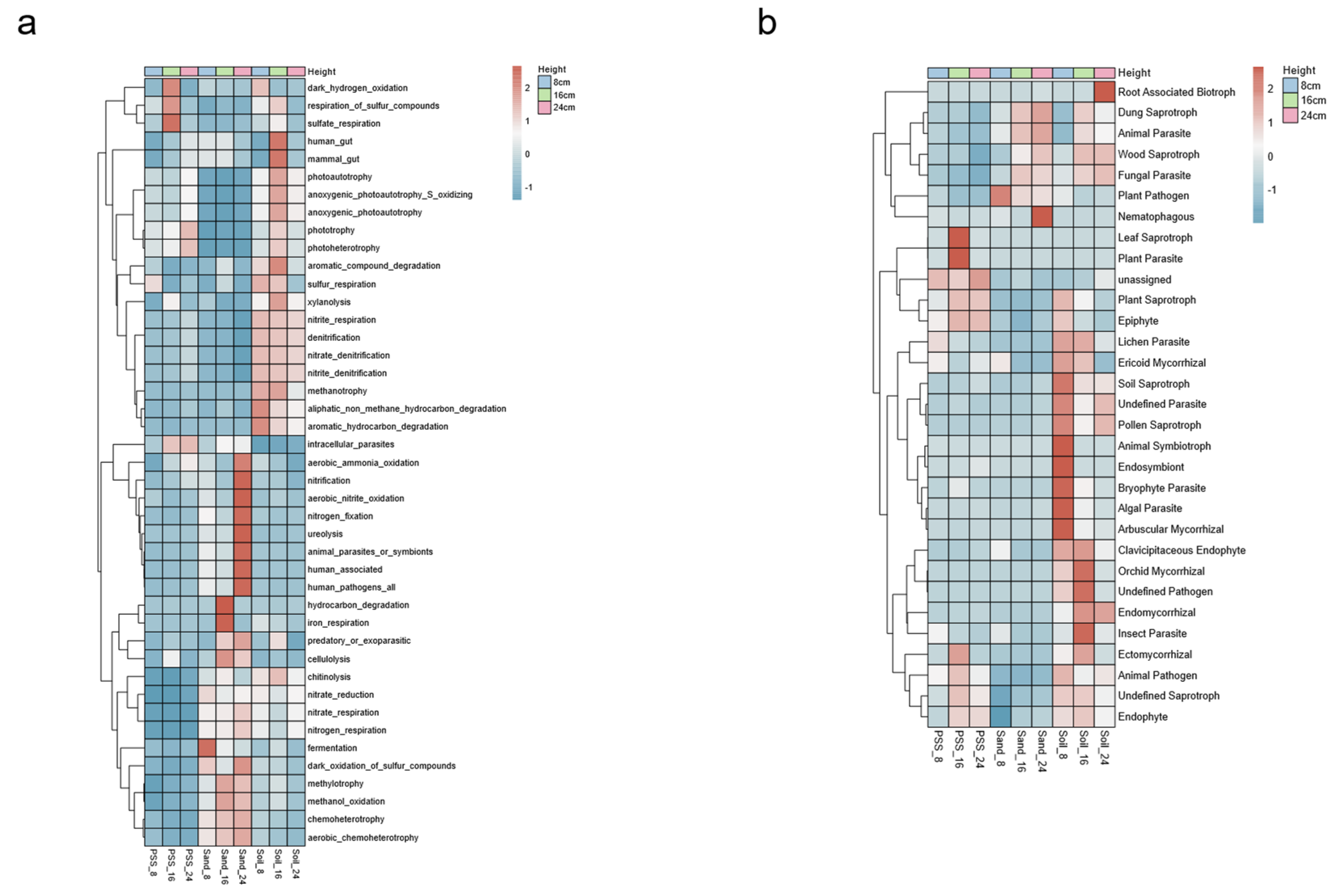

3.5.3. Microbial Functional Annotation

The relative abundances of functional bacteria involved in carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur cycling were higher in soil and sand, whereas those involved in element cycling were lower in peanut shell substrate (PSS). Specifically, the tomato rhizosphere in soil tended to enrich bacteria associated with denitrification, nitrite respiration, anaerobic photoautotrophic sulfur oxidation, sulfur respiration, and hydrocarbon degradation. In contrast, sand preferentially enriched bacteria involved in nitrification, aerobic nitrite oxidation, nitrogen fixation, urea decomposition, nitrate reduction, nitrate respiration, nitrogen respiration, aerobic sulfide oxidation, and methylotrophic bacteria. By comparison, PSS showed higher relative abundances of bacteria engaged in sulfur compound respiration and sulfate respiration (

Figure 9a). These results indicate that soil, with poorer aeration, harbors more anaerobic bacteria, whereas sand, with better aeration, supports bacterial communities inclined toward aerobic lifestyles. With increasing soil height, the relative abundances of functional bacteria related to dark hydrogen oxidation, denitrification, anaerobic photoautotrophic sulfur oxidation, sulfur respiration, and hydrocarbon degradation decreased. Conversely, as sand height increased, the abundances of nitrification, aerobic nitrite oxidation, aerobic sulfide oxidation, and methylotrophic bacteria rose. Additionally, higher heights in PSS correlated with increased abundances of phototrophic and aerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. These findings suggest that elevating substrate height shifted the functional traits of rhizosphere bacteria toward phototrophic and aerobic metabolism.

Saprophytic, symbiotic, parasitic, and epiphytic fungi were all widely present in soil. Fungal lifestyles in sand tended to be saprophytic and parasitic, while those in peanut shell substrate (PSS) tended to be saprophytic, symbiotic, and epiphytic (

Figure 9b). These results indicate that PSS were rich in organic matter, thus favoring saprophytic and symbiotic fungal lifestyles; in contrast, sand lacked organic substances, leading fungi to adopt lifestyles such as parasitism and predation. In soil, due to its higher fungal diversity, fungal lifestyles were more diverse than those in sand and peanut shell substrate. With increasing height, the abundances of some saprophytic, symbiotic, and parasitic fungi decreased in soil. In sand, the abundances of saprophytic and parasitic fungi increased with height, while in PSS, the relative abundances of epiphytic, saprophytic, and symbiotic fungi increased with height

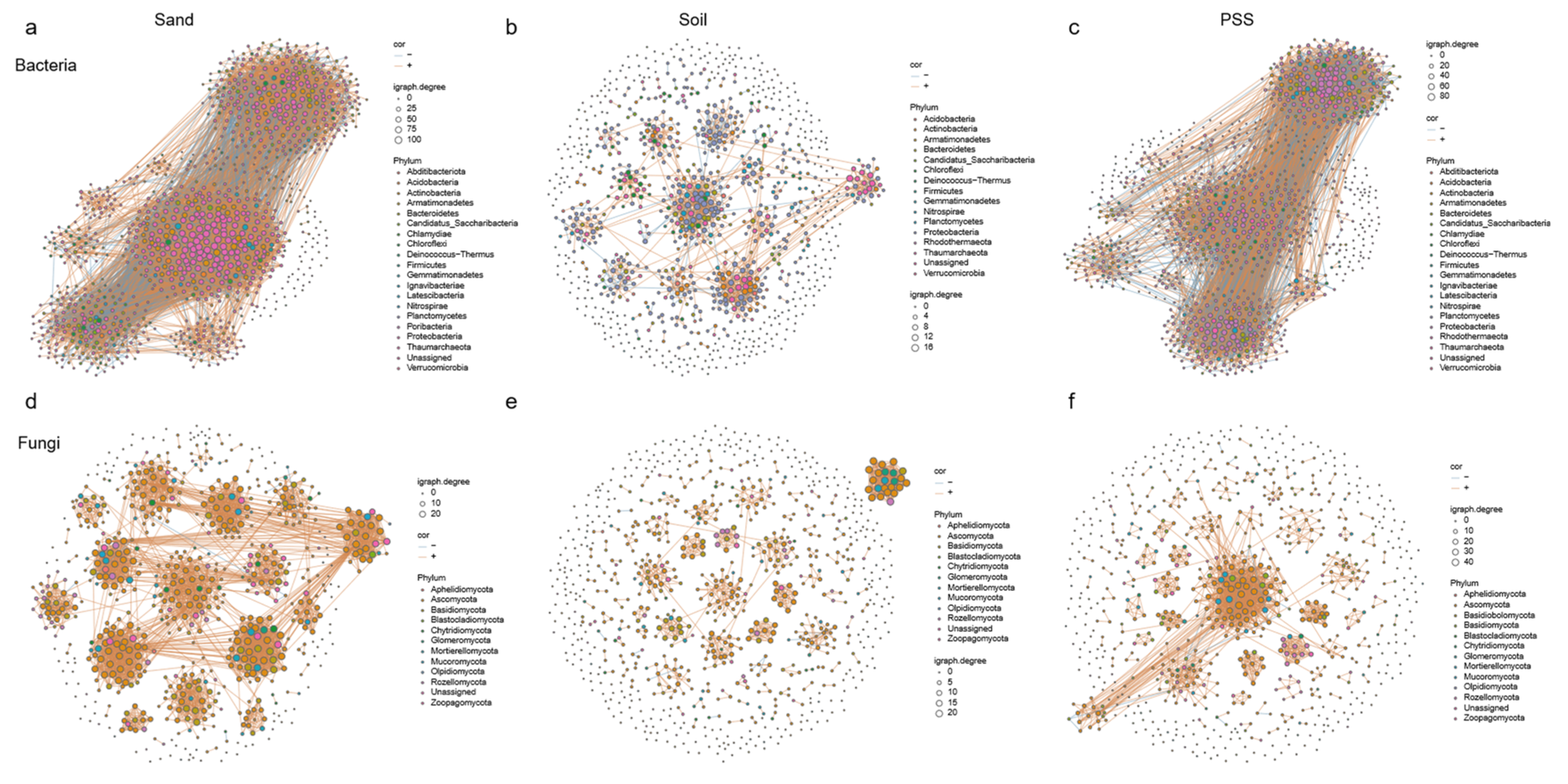

3.5.4. Microbial Network Analysis Under Different Substrates

At the phylum level, we observed that the dominant bacteria involved in interactions across the three substrates were

Proteobacteria (

Figure 10a–c), and the dominant fungi were

Ascomycota (

Figure 10d–f). The rhizosphere microbial networks in sand and peanut shell substrate (PSS) exhibited significantly higher numbers of edges, density, and average node degrees compared to soil, with relatively higher modularity. Specifically, the number of edges in soil was 893, versus 8473 in sand and 4637 in PSS; the average node degree was 2.80 in soil, 18.07 in sand, and 10.78 in PSS. For rhizosphere fungi, the number of edges was 929 in soil, 2978 in sand, and 1369 in PSS; the average node degree was 3.53 in soil, 10.29 in sand, and 5.24 in PSS. These results indicate that rhizosphere microbiomes in PSS and sand—particularly those in sand—exhibit strongly clustered network topologies with high connectivity among microbial taxa. This may be attributed to the coarse-textured soil environment, which, when saturated with water, has a larger pore volume and higher connectivity (Ebrahimi & Or, 2014; Holden, 2011; Stewart & Hartge, 1995; Vos et al., 2013). Such properties evidently promote material movement and exchange between microsites, thereby leading to elevated microbial co-occurrence patterns.

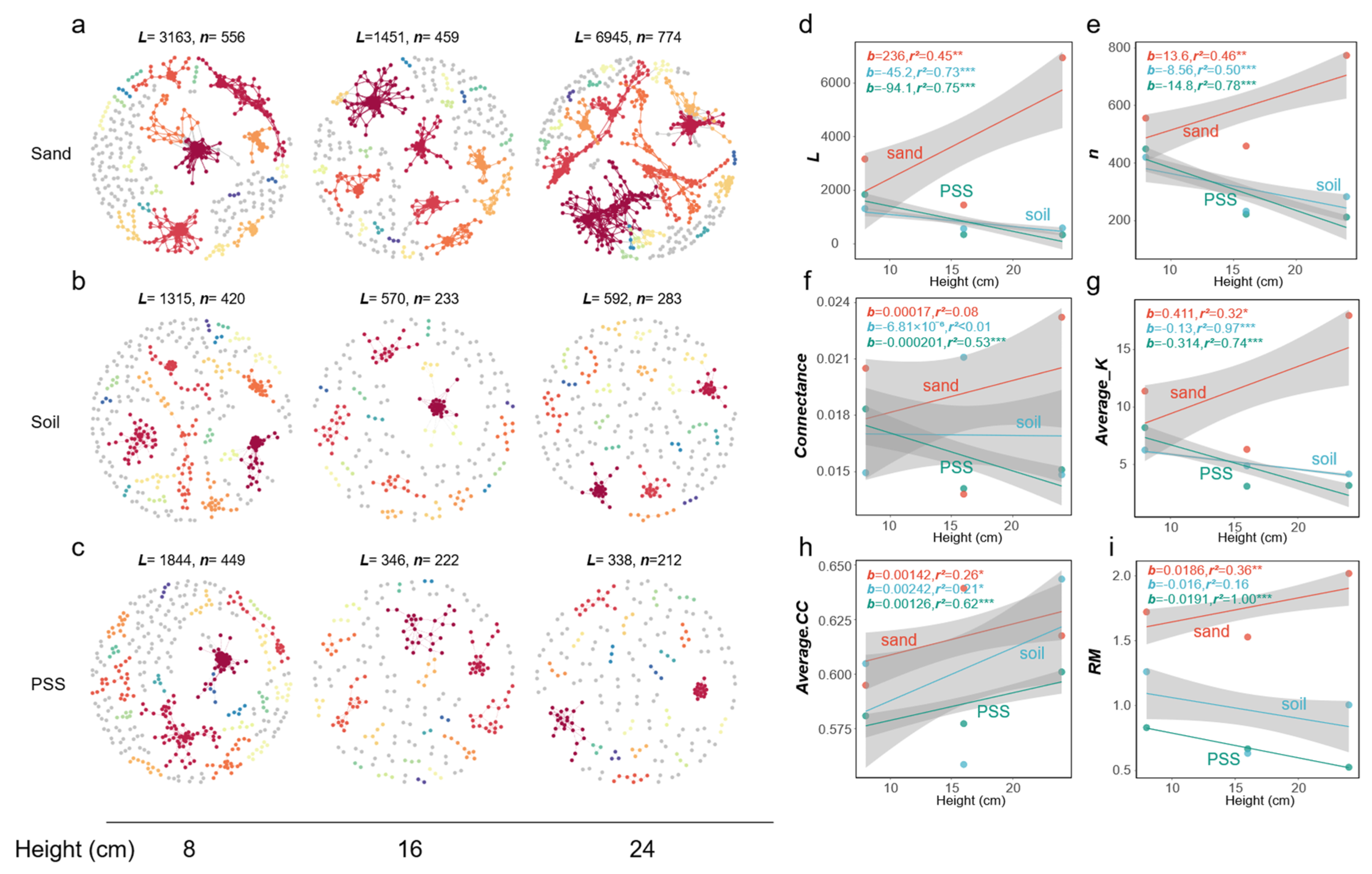

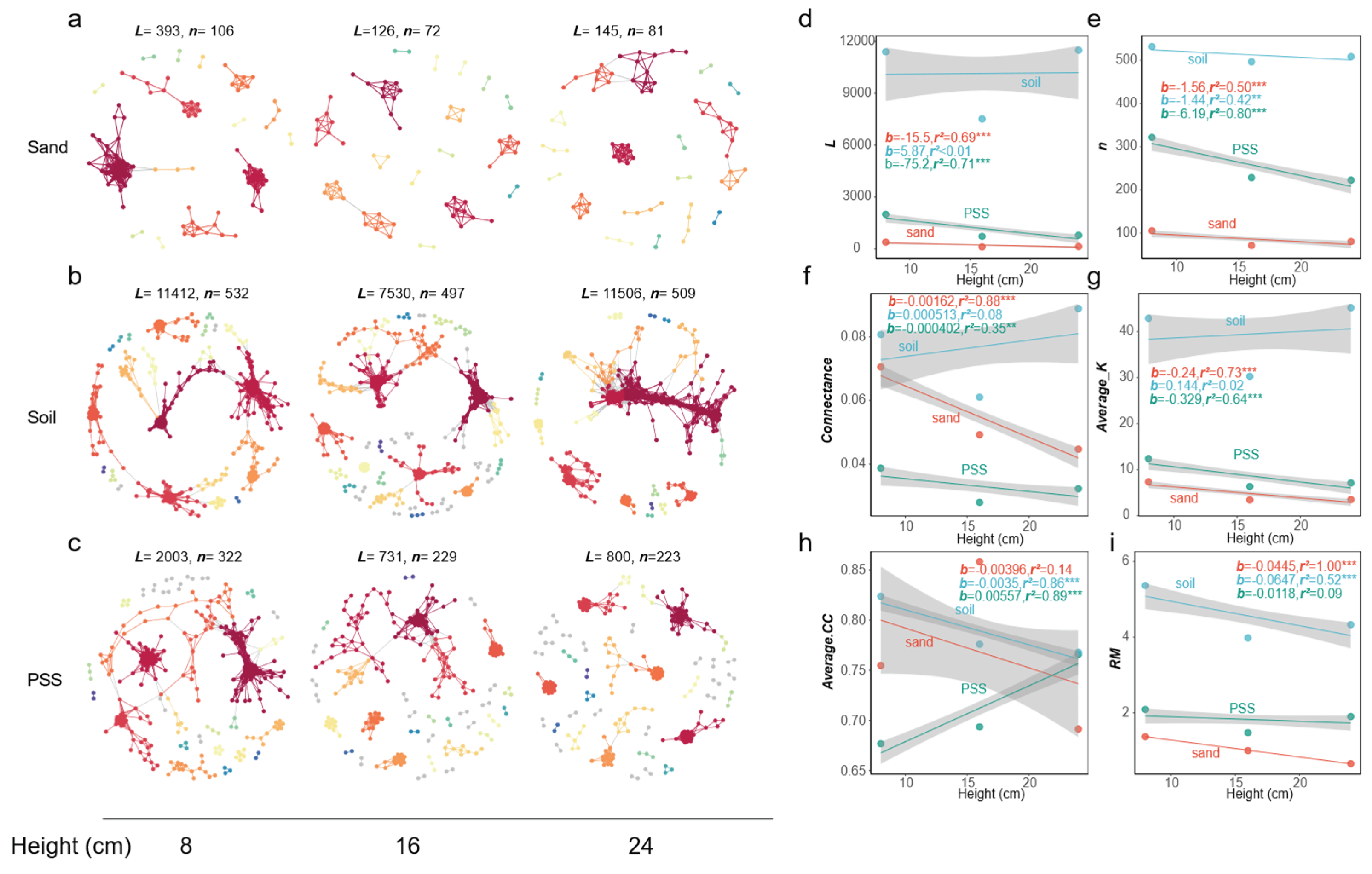

3.5.5. Analysis of Microbial Networks Under Different Container Heights

In soil and peanut shell substrate (PSS), when container height increased, the number of edges (

L), number of vertices (

n), connectance (edge density), average degree (

Average K), and relative modularity (

RM) of tomato rhizosphere bacterial networks all decreased, whereas in sand, these indices increased. The mean clustering coefficient (

Average.CC) increased with increasing container height in all three substrates (

Figure 11a–i). At the fungal level, connectance (edge density) in sand decreased with increasing container height, while mean clustering coefficient (

Average.CC) in PSS increased, and both decreased in soil. Overall, the structure of rhizosphere fungal interaction networks showed no significant response to changes in substrate height (

Figure 12a-i). These results indicate that in soil and PSS with greater container heights, the overall rhizosphere bacterial connectivity decreased, and bacterial interactions became less frequent. In soil and PSS at lower container heights, bacterial communities exhibited higher connectivity. The structural changes in bacterial networks of sand were opposite to those of PSS and soil; increasing container height led to more intense interactions in the rhizosphere bacterial network of sand.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Root-Restriction Height on Substrate Physical Properties and Tomato Phenotype

Sand, as an inorganic substrate, has natural particle sizes ranging from 0.05 to 2.0 mm. It is relatively inexpensive, has good drainage capacity, but low nutrient and water retention capabilities, high bulk density (1400-1600 kg/m3), and total pore space of 40%-50% by volume. Green compost, as an organic substrate, is derived from plant residues after composting treatment. It is a good source of potassium and trace nutrients, suppresses diseases, has good water retention capacity, and reduces urban waste. Its composition varies, with a bulk density of 600 - 950 kg/m3, and may contain excessive salt levels, requiring time for composting treatment, and is prone to waterlogging (Gianquinto et al., 2006; Lal, 2017). Soil physical properties varying with depth or soil layer include bulk density, moisture content, texture (clay/silt/loam ratio), and porosity (Iqbal et al., 2005). Increasing the height of containerized substrates can significantly enhance air availability but reduce water availability. However, the substrate type (particularly particle size) ultimately determined whether air or water availability will critically limit crop growth (Savvas, 2009). Our results indicate that increasing the height of the three substrates led to decreases in bulk density and water holding capacity, while total water storage capacity increased. Among these, the bulk density and water holding capacity of the PSS responded more noticeably to changes in container height compared to soil and sand.

In soilless cultivation systems, the height of the cultivation trough and substrate particle size were considered key factors affecting root zone water availability and aeration (Savvas & Gruda, 2018). The height of the substrate layer should be maintained at a sufficiently large scale to ensure optimal drainage and aeration (Heller et al., 2015), whereas substrates with a higher proportion of fine particles demonstrate better suitability for tall and narrow containers, while coarser substrates are more appropriately utilized in shallow bags or troughs (Savvas, 2007). Altering the root-restriction height in substrate can affect tomato growth, yield, and quality. Studies have shown that root-restricted cultivation of tomatoes reduces the soluble sugar content in their fruits (Gao et al., 2023; D. Liu et al., 2023), while other studies demonstrated that root-restricted cultivation reduces tomato yield (Bar-Tal & Pressman, 1996). Although reducing the root-restriction volume can improve quality, it reduces yield by approximately 20–30%. Current research lacks a comprehensive trade-off analysis between “quality gains” and “yield losses”.

In this study, we evaluated the contributions of three representative cultivation substrates to tomato growth, fruit yield, and quality. We used the TOPSIS (Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution) method to evaluate optimal root-restriction levels for different substrates, considering the three factors above. The results showed that the optimal trough heights were 8 cm for peanut shell substrate (PSS), 24 cm for soil, and 8 cm for sand, respectively. These align with Savvas (2007) regarding particle-trough matching but extend prior work by demonstrating PSS’s unique water-holding capacity defies conventional coarse-substrate height requirements. Sand, with its coarser particles, was suitable for lower troughs; soil, with finer particles, was better suited for higher troughs—findings consistent with previous research (Savvas, 2007). Although PSS had a larger particle size, its superior water absorption capacity enabled it to maintain a water-air balance in shallow troughs.

Our research results indicate that as the root-restriction height decreased, the soluble sugar content and lycopene content of tomatoes increased, whereas the single-plant yield declined. This aligns with the research findings on the regulation of tomato fruit quality and yield by root-restricted cultivation technology. Additionally, we found that changes in the root-restriction height of sand and soil have a significant impact on tomato growth. Specifically, the higher height of sand and soil, the better vegetative growth status of tomatoes. However, the vegetative growth of tomatoes cultivated in PSS was insensitive to changes in substrate height. The results support the universal pattern that root-restricted cultivation improves quality while reducing yield through stress effects, but they also reveal for the first time that PSS (peanut shell substrate), owing to its high water-holding capacity, can overcome the conventional limitations imposed by root-restriction height, offering a new pathway for synergistically optimizing both fruit quality and resource efficiency.

4.2. Rhizosphere Microorganisms in Different Substrates

Investigations by Anzalone et al. revealed that the dominant bacterial phyla in the tomato rhizosphere are Proteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Actinobacteria, while the fungal communities are primarily dominated by Ascomycota, Basidiomycota, Olpidiomycota, and Morteriellomycota. Although bacterial and fungal microbiota have been extensively characterized across diverse plant species and environments, significant knowledge gaps persist regarding the impact of agricultural practices—particularly root-zone restriction (RZR)—on tomato rhizosphere microbiota and its functional implications (Anzalone et al., 2022). Our results demonstrate that RZR significantly reshapes tomato rhizosphere microbiota with substrate-dependent patterns: the bacterial community in the tomato rhizosphere was primarily composed of Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Candidatus_Saccharibacteria, Chloroflexi, Acidobacteria, and Gemmatimonadetes. Among the rhizosphere fungi, soil and sand were mainly dominated by Ascomycota, whereas the peanut shell substrate (PSS) was primarily composed of Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. Additionally, we observed that the relative abundances of Basidiomycota and Mortierellomycota in the PSS were higher than those in soil and sand.

LEfSe identified indicator genera in tomato rhizospheres under different substrates, revealing substrate-driven functional specialization. In soil,

Sphingomonas (Asaf et al., 2020; White et al., 1996),

Saccharibacteria_genera_incertae_sedis (X. Zhang et al., 2024), and

Nocardioides (Ma et al., 2023) have all been reported to participate in the degradation of organic pollutants such as heavy metals, petroleum, and aromatic compounds in soil, which aligns with the functional annotation results showing increased abundance of aromatic compound-degrading bacteria in soil (

Figure 10a). Fusarium, on the other hand, has been reported as a genus of plant-pathogenic fungi (Gordon, 2017; Han et al., 2012; Leplat et al., 2013). These results demonstrate that natural soils were contaminated with organic pollutants and harbor various plant pathogens. In sand, members of

Methylotenera were typical methylotrophic bacteria (Li et al., 2025).

Penicillium enhances plant growth by interacting synergistically with roots, providing nutrients (e.g., soluble phosphorus) and phytohormones (e.g., IAA, GA). Some species suppress pathogens via antibiotic production, while others boost resistance through systemic resistance induction and defense signaling activation. Certain

Penicillium strains are also applied in bioremediation to remediate heavy metal-polluted soils, and they further contribute to organic matter decomposition and nutrient cycling (Srinivasan et al., 2020). Most

Plectosphaerella species have been reported to cause disease symptoms in tomatoes and peppers (Raimondo & Carlucci, 2018). Functional studies on the microbial genera indicator in sand indicate that sand lacks plant-available carbon sources and similarly has plant pathogens. In peanut shell substrate (PSS), the indicator genus

Aspergillus played a critical role in the cycling of major nutrients such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, and sulfur. It exhibited antibacterial activity against other pathogenic fungi; some common or rare species within this fungal group can also produce important plant growth hormones, including auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins, and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) (Nayak et al., 2020).

Mortierella utilizes carbon from polymers (e.g., cellulose, hemicellulose, chitin), enhances bioavailable phosphorus and iron in soil, synthesizes phytohormones and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate (ACC) deaminase, and protects crops from pathogens (Ozimek & Hanaka, 2021). Some strains of this genus belonged to plant growth-promoting fungi (PGPF) (Xiong et al., 2017). Previous analyses overlooked how physicochemical properties (such as the high porosity of PSS and low water retention capacity of sand) drive microbial functional divergence. Our results indicate that substrate properties drive functional divergence of rhizosphere microbial communities through dual pathways: resource availability (e.g., cellulose-derived carbon sources in PSS) and stress selection pressure (e.g., soil pollutants). Soil legacy pollutants (e.g., heavy metals, petroleum hydrocarbons) selectively enrich pollutant-degrading bacteria (e.g.,

Sphingomonas,

Nocardioides) but concurrently elevate risks of pathogen proliferation. In sandy substrates, carbon scarcity drives the enrichment of methylotrophic bacteria (e.g.,

Methylotenera), which utilize C1 compounds as energy sources. However, limited carbon availability constrains energy-intensive antagonistic traits, resulting in compromised pathogen suppression capacity. Peanut shell substrate (PSS) leverages its lignocellulosic resources and high water-holding capacity to directly recruit synergistic fungal consortia specialized in carbon transformation (e.g.,

Aspergillus decomposing lignin) and plant growth promotion (e.g.,

Mortierella synthesizing IAA/ACC deaminase). This substrate-induced microbiome engineering offers novel strategies for optimizing root-zone restriction (RZR) systems by balancing physical confinement stress with beneficial microbial functions.

Rüger et al. demonstrated that fine-textured soils host small, isolated microbial subcommunities, whereas the rhizosphere microbiome in coarse-textured (high-sand) soils forms a strongly clustered network topology characterized by high microbial connectivity (Rüger et al., 2023). Soil texture defines important habitat properties for soil microbiota, but it also feeds back on root elongation rate and root system architecture. Decreased axial root length in coarse-grained texture levels was compensated for by enhanced lateral root growth. Previous studies have disproportionately focused on bacterial communities, overlooking the contribution of the modular structure of fungal networks to ecosystem stability. Additionally, existing conclusions fail to distinguish the fundamental differences in microbial network formation between artificial substrates and natural soils.Our results indicate that the number of edges, density, and average node degree of rhizosphere microorganisms in sand and PSS were significantly higher than those in soil, and their relative modularity is greater. The network topology of PSS lay between that of soil and sand. In terms of rhizosphere bacterial network topology, it was more inclined toward the structure of sand, showing a strongly clustered pattern, whereas the network topology of rhizosphere fungi was like that of soil, with networks leaning more toward modular structures.

4.3. Effect of Container Height on Microbial Functions and Network Structure

Savvas et al. reported that in soilless cultivation systems, the higher the container height, the lower the water content of the growing medium inside the container and the higher the gas content (Savvas, 2009). Heller et al., using lettuce as a model, investigated the water content of the growing medium in containers of varying heights and found that the water content in tall, narrow containers was lower than that in short, wide containers (Heller et al., 2015). Zhang et al. revealed that diverse metabolic pathways (encompassing aerobic/anaerobic transformations of C, N, S, Fe, and Mn) in soil columns exhibited responsiveness to water table fluctuations (Z. Zhang et al., 2024). Additionally, the vertical stratification of microbial communities was linked to dynamic hydrological conditions, specifically, frequent pulse recharge under infiltration regimes and recurrent groundwater variations under fluctuating regimes. Our annotation results of tomato rhizosphere bacterial communities under different heights reveal that the metabolic pathways of rhizosphere bacteria (aerobic or anaerobic pathways for C, N, and S) responded to changes in container height, and the differentiation of microbial redox functions was related to the hydrological conditions within the container.

This study referenced the methodology of Yuan et al. for analyzing microbial network complexity and examined the variations in network parameters (Yuan et al., 2021)- including the number of edges (L), number of vertices (n), connectance (edge density), average degree (Average K), relative modularity (RM) and mean clustering coefficient (Average.CC) - with root restriction height. The network analysis reveals that increasing container height enhanced bacterial community complexity in sandy rhizosphere while reducing it in PSS and soil rhizospheres, with minimal impact on fungal community complexity across all three substrates (

Figure 11).

Upton et al. found more complex and highly connected networks of fungal and bacterial communities in shallower soil layers of grasslands (Upton et al., 2020). Zhao et al. reported that a decline in groundwater levels in grasslands reduced the complexity of microbial co-occurrence networks (Zhao et al., 2023). Banerjee et al. reported that the complexity of bacterial, fungal, and archaeal networks declined with increasing soil depth, alongside reductions in key network parameters such as node count, edge number, and maximum degree (Banerjee et al., 2021). In our study, we simulated groundwater levels using a water level controller and adjusted the depth of the water level at the bottom of containers by varying container height. The results showed that even in an artificially simulated cultivation system, changes in the structure of microbial co-occurrence networks in PSS and soils were consistent with previous findings: soils and PSS in taller containers had lower water content, lower groundwater levels, reduced overall connectivity of rhizosphere bacteria, and fewer bacterial interactions. Conversely, soils and PSS in shorter containers exhibited higher connectivity in their bacterial communities.

The structural changes in the bacterial network of sand differed from those in PSS and soil. Increasing the height of the cultivation container resulted in more intense interactions in the rhizosphere bacterial network of sand. Characterized by large pores and low water and nutrient retention capacity (Gianquinto et al., 2006; Lal, 2017), sand in taller containers formed a thicker sand layer. Differences in water infiltration and evaporation rates led to a vertical water gradient (Zhang et al., 2024) (with the surface layer drier and the deeper layer wetter). The surface sand layer, with more direct contact with air, has higher oxygen content (an aerobic environment), whereas the deep sand layer, restricted by oxygen diffusion, may develop anaerobic or micro-aerophilic microenvironments. This oxygen gradient drove redox functional differentiation in the microbial community (e.g., coexistence of aerobic nitrifying bacteria and anaerobic denitrifying bacteria) (Z. Zhang et al., 2024), enhancing functional interactions within the network.

Container height also influenced the intensity of the “edge effect” within the sand layer. In shorter containers, the surface sand layer experienced more frequent contact with the external environment, making it susceptible to disturbances such as temperature fluctuations, drying, or invasion by exotic microorganisms. This reduced the stability of the microbial community, but resident microbes harbored physiological tolerance mechanisms enabling adaptation to fluctuating redox potential conditions (DeAngelis et al., 2010; Pett-Ridge et al., 2006; Pett-Ridge & Firestone, 2005). In contrast, taller containers provided a larger internal space within the sand layer, weakening the edge effect and stabilizing the internal microenvironment (e.g., smaller temperature and humidity fluctuations). This stability offered long-term colonization opportunities for diverse microorganisms. Such stability allowed more “rare microorganisms” (which might be outcompeted by dominant species in shorter containers) to persist and participate in interactions, thereby increasing the connectivity and complexity of the network.

5. Conclusion

In this study, we employed the Simplified Automatic Soilless Culture System (SAS) to conduct root-restricted tomato cultivation at different levels. The objective was to identify the optimal coupling pattern of substrate type and container height in the SAS system that promotes tomato growth, enhances fruit yield and quality, and to investigate the changes in rhizosphere microorganisms under different substrate types and container heights. The main conclusions are as follows:

Increasing the height of the cultivation trough can enhance the total water storage capacity of the substrate and fruit yield in the SAS system, whereas decreasing the height will improve the fruit quality.

Using TOPSIS to evaluate the comprehensive indicators of tomatoes, the results indicate that the optimal root-restriction levels for different substrates: 8cm peanut shell substrate >24 cm soil >8cm sand.

Sand, soil, and peanut shell substrate establish bacterial and fungal communities inhabiting roots through the selection of specific microbial taxa.

High variation in the container can drive the functional differentiation of redox properties in microbial communities, affecting the connectivity and complexity of microbial networks.

This study was conducted in a glass greenhouse using the SAS system for testing, providing an important reference for substrate selection and root system management in industrial tomato cultivation. However, the results cannot reflect the overall conditions of tomatoes grown in field settings. In future research, further investigations can be conducted to explore the impacts of irrigation volume, irrigation frequency, and “plant growth-promoting microorganisms” on tomato growth, soil microbial environment, yield, and quality.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Yecheng Jin: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Visualization, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Siqi Xia: Visualization, Validation. Haili Zhang: Supervision. Lingyu Wang: Supervision, Funding acquisition. Ying Zhou: Supervision. Jie Zhou: Visualization, Validation, Methodology. Xiaojian Xia: Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Funding acquisition. Nianqiao Shen: Writing—review & editing, Conceptualization. Zhenyu Qi: Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFD2300704), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Zhejiang Provincial Universities (2024QZJH67).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Alexander, M. Introduction to soil microbiology. Soil Science 1978, 125(5), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.; Mosca, A.; Dimaria, G.; Nicotra, D.; Tessitori, M.; Privitera, G. F.; Pulvirenti, A.; Leonardi, C.; Catara, V. Soil and Soilless Tomato Cultivation Promote Different Microbial Communities That Provide New Models for Future Crop Interventions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23(15), 8820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaf, S.; Numan, M.; Khan, A. L.; Al-Harrasi, A. Sphingomonas: from diversity and genomics to functional role in environmental remediation and plant growth. In Critical Reviews in Biotechnology; 2020; Volume 40, 2, pp. 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balliu, A.; Zheng, Y.; Sallaku, G.; Fernández, J. A.; Gruda, N. S.; Tuzel, Y. Environmental and Cultivation Factors Affect the Morphology, Architecture and Performance of Root Systems in Soilless Grown Plants. Horticulturae 2021, Vol. 7(Page 243, 7 (8)), 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Zhao, C.; Kirkby, C. A.; Coggins, S.; Zhao, S.; Bissett, A.; van der Heijden, M. G. A.; Kirkegaard, J. A.; Richardson, A. E. Microbial interkingdom associations across soil depths reveal network connectivity and keystone taxa linked to soil fine-fraction carbon content. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2021, 320, 107559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, A.; Pressman, E. Root restriction and potassium and calcium solution concentrations affect dry-matter production, cation uptake, and blossom-end rot in greenhouse tomato. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 1996, 121(4), 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunt, B. R. Media and mixes for container-grown plants: a manual on the preparation and use of growing media for pot plants; Springer Science & Business Media, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Caron, J.; Nkongolo, V. K. N. Aeration in growing media: Recent developments. Acta Horticulturae 1999, 481, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Liu, Y. X.; Chen, T.; Yang, M.; Fan, S.; Shi, M.; Wei, B.; Lv, H.; Cao, W.; Wang, C.; Cui, J.; Zhao, J.; Han, Y.; Xi, J.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, L. ImageGP 2 for enhanced data visualization and reproducible analysis in biomedical research. IMeta 2024, 3(5), e239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepsergon, J.; Moleleki, L. N. Rhizosphere bacterial interactions and impact on plant health. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2023, 73, 102297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeAngelis, K. M.; Silver, W. L.; Thompson, A. W.; Firestone, M. K. Microbial communities acclimate to recurring changes in soil redox potential status. In Environmental Microbiology; 2010; Volume 12, pp. 3137–3149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lorenzo, R.; Pisciotta, A.; Santamaria, P.; Scariot, V. From soil to soil-less in horticulture: quality and typicity. Italian Journal of Agronomy 2013, 8(4), e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, A. N.; Or, D. Microbial dispersal in unsaturated porous media: Characteristics of motile bacterial cell motions in unsaturated angular pore networks. Water Resources Research 2014, 50(9), 7406–7429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbach, D. C. Measurement of Soil Bulk Density and Moisture. Transactions of the ASAE 1987, 30(4), 922–0931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonteno, W. C. PROBLEMS & CONSIDERATIONS IN DETERMINING PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF HORTICULTURAL SUBSTRATES. Acta Horticulturae 1993, 342, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liang, H.; Ji, Y.; Liu, M. Effects of Comparative Metabolism on Tomato Fruit Quality under Different Levels of Root Restriction. HortScience 2023, 58(8), 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianquinto, G.; Orsini, F.; Michelon, N.; Da Silva, D. F.; De Faria, F. D. Improving yield of vegetables by using soilless micro-garden technologies in peri-urban area of North-East Brazil. VIII International Symposium on Protected Cultivation in Mild Winter Climates: Advances in Soil and Soilless Cultivation under 747; 2006; pp. 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, T. R. Fusarium oxysporum and the Fusarium Wilt Syndrome. Annual Review of Phytopathology 2017, 55((Volume 55), 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grondin, A.; Li, M.; Bhosale, R.; Sawers, R.; Schneider, H. M. Interplay between developmental cues and rhizosphere signals from mycorrhizal fungi shape root anatomy, impacting crop productivity. Plant and Soil 2024, 503(1), 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruda, N. Current and future perspective of growing media in Europe. V Balkan Symposium on Vegetables and Potatoes 960; 2011; pp. 37–43. [Google Scholar]

- Grunert, O.; Hernandez-Sanabria, E.; Buysens, S.; De Neve, S.; Van Labeke, M. C.; Reheul, D.; Boon, N. In-Depth Observation on the Microbial and Fungal Community Structure of Four Contrasting Tomato Cultivation Systems in Soil Based and Soilless Culture Systems. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 11, 520834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, O.; Hernandez-Sanabria, E.; Vilchez-Vargas, R.; Jauregui, R.; Pieper, D. H.; Perneel, M.; Van Labeke, M. C.; Reheul, D.; Boon, N. Mineral and organic growing media have distinct community structure, stability and functionality in soilless culture systems. Scientific Reports 2016, 6:1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.-S.; Lee, S.-C.; Lee, J.-S.; Soh, J.-W. First Report of Pink Mold Rot on Tomato Fruit Caused by Trichothecium roseum in Korea. Research in Plant Disease 2012, 18(4), 396–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Li, X.; Tian, Y.; He, X.; Qin, K.; Zhu, L.; Cao, Y. Effect of Lycium barbarum L. Root Restriction Cultivation Method on Plant Growth and Soil Bacterial Community Abundance. Agronomy 2022, Vol. 13(Page 14, 13 (1)), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, H.; Bar-Tal, A.; Assouline, S.; Narkis, K.; Suryano, S.; de la Forge, A.; Barak, M.; Alon, H.; Bruner, M.; Cohen, S. The effects of container geometry on water and heat regimes in soilless culture: lettuce as a case study. Irrigation Science 2015, 33, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, P. A. How do the microhabitats framed by soil structure impact soil bacteria and the processes that they regulate? In Life in Inner Space; The Architecture and Biology of Soils: Life in Inner Space,, 2011; pp. 118–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, J.; Thomasson, J. A.; Jenkins, J. N.; Owens, P. R.; Whisler, F. D. Spatial Variability Analysis of Soil Physical Properties of Alluvial Soils. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2005, 69(4), 1338–1350, SUBPAGE:STRING:ABSTRACT;WEBSITE:WEBSITE:ACSESS.ON LINELIBRARY.WILEY.COM;WGROUP:STRING:PUBLICATION. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Z.; Liu, H. Modification of Rhizosphere Microbial Communities: A Possible Mechanism of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria Enhancing Plant Growth and Fitness. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022, 13, 920813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koohakan, P.; Ikeda, H.; Jeanaksorn, T.; Tojo, M.; Kusakari, S. I.; Okada, K.; Sato, S. Evaluation of the indigenous microorganisms in soilless culture: occurrence and quantitative characteristics in the different growing systems. Scientia Horticulturae 2004, 101(1–2), 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Encyclopedia of soil science; CRC Press, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, F.; Duan, S.; Song, S.; Zhao, L.; Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Ma, C.; Wang, L.; Wang, S. Comparative metabolic profiling of grape pulp during the growth process reveals systematic influences under root restriction. Metabolites 2021, 11(6), 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, F.; Wang, Y.; Cao, J.; Wang, S.; Wu, D.; Jiang, L.; Li, X.; Bao, J.; Karim, N.; Sun, C. Transcriptomic Analysis of Root Restriction Effects on the Primary Metabolites during Grape Berry Development and Ripening. Genes 2022, Vol. 13(Page 281, 13 (2)), 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leplat, J.; Friberg, H.; Abid, M.; Steinberg, C. Survival of Fusarium graminearum, the causal agent of Fusarium head blight. A review. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2013, 33(1), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Dong, X.; Humez, P.; Borecki, J.; Birks, J.; McClain, C.; Mayer, B.; Strous, M.; Diao, M. Proteomic evidence for aerobic methane production in groundwater by methylotrophic Methylotenera. The ISME Journal 2025, 19(1), 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Hao, Y.; Yang, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Y. Effects of Extreme Root Restriction on the Nutritional and Flavor Quality, and Sucrose Metabolism of Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Horticulturae 2023, 9(7). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wei, Z.; Li, J. Effects of copper on leaf membrane structure and root activity of maize seedling. Botanical Studies 2014, 55(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Ma, T.; Li, X.; Zheng, M.; Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Qian, X.; Xi, J.; Lu, H. EasyAmplicon: An easy-to-use, open-source, reproducible, and community-based pipeline for amplicon data analysis in microbiome research. Imeta 2023, 2(1), e83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, S.; Parfrey, L. W.; Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 2016, 353(6305), 1272–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, W.; Chen, T.; Liu, G.; Xue, L.; Cui, X. Nocardioides: “Specialists” for Hard-to-Degrade Pollutants in the Environment. Molecules 2023, Vol. 28(Page 7433, 28 (21)), 7433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyappillai, A.; Arumugam, G. Physico-chemical and hydrological properties of soilless substrates. Journal of Environmental Biology 2021, 42(3), 700–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, S.; Samanta, S.; Mukherjee, A. K. Beneficial Role of Aspergillus sp. in Agricultural Soil and Environment. In Frontiers in Soil and Environmental Microbiology; 2020; pp. 17–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, P. V. Greenhouse Operation and Management. Greenhouse Operation & Management 2011, 3, 455–456. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, N. H.; Song, Z.; Bates, S. T.; Branco, S.; Tedersoo, L.; Menke, J.; Schilling, J. S.; Kennedy, P. G. FUNGuild: an open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecology 2016, 20, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozimek, E.; Hanaka, A. Mortierella species as the plant growth-promoting fungi present in the agricultural soils. Agriculture (Switzerland) 2021, 11(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palta, J. P. Leaf chlorophyll content. Remote Sensing Reviews 1990, 5(1), 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T. A.; Reinsel, M. D.; Krizek, D. T. Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill., cv. ‘Better Bush’) Plant Response to Root Restriction. Journal of Experimental Botany 1991, 42(10), 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pett-Ridge, J.; Firestone, M. K. Redox fluctuation structures microbial communities in a wet tropical soil. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2005, 71(11), 6998–7007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pett-Ridge, J.; Silver, W. L.; Firestone, M. K. Redox fluctuations frame microbial community impacts on N-cycling rates in a humid tropical forest soil. Biogeochemistry 2006, 81(1), 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, J. The Status of Biological Control of Plant Diseases in Soilless Cultivation. In Recent Developments in Management of Plant Diseases; 2010; pp. 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimondo, M. L.; Carlucci, A. Characterization and pathogenicity assessment of Plectosphaerella species associated with stunting disease on tomato and pepper crops in Italy. In Plant Pathology; 2018; Volume 67, 3, pp. 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A. V.; Waseem, Z.; Agarwal, S. Lycopene content of tomatoes and tomato products and their contribution to dietary lycopene. Food Research International 1998, 31(10), 737–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, M.; Lieth, J. H.; Bar-Tal, A. Soilless culture: Theory and practice: Theory and practice; Elsevier, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raviv, M.; Wallach, R.; Silber, A.; Bar-Tal, A. Substrates and their analysis. In Hydroponic Production of Vegetables and Ornamentals; 2002; pp. 25–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rüger, L.; Feng, K.; Chen, Y.; Sun, R.; Sun, B.; Deng, Y.; Vetterlein, D.; Bonkowski, M. Responses of root architecture and the rhizosphere microbiome assembly of maize (Zea mays L.) to a soil texture gradient. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2023, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammar Khalil, S. K.; Alsanius, B. W. Dynamics of the indigenous microflora inhabiting the root zone and the nutrient solution of tomato in a commercial closed greenhouse system. 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Savvas, D. Hydroponics: a modern technology supporting the application of integrated crop management in greenhouse; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Savvas, D. Modern developments in the use of inorganic media for greenhouse vegetable and flower production. International Symposium on Growing Media 2007 819 2007, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savvas, D. Modern developments in the ise of inorganic media for greenhouse vegetable and flower production. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Savvas, D.; Gruda, N. Application of soilless culture technologies in the modern greenhouse industry - A review. European Journal of Horticultural Science 2018, 83(5), 280–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, J. C.; Desborough, S. L. Rapid estimation of potato tuber total protein content with coomassie brilliant blue G-250. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 1978, 52(3), 135–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, R.; Prabhu, G.; Prasad, M.; Mishra, M.; Chaudhary, M.; Srivastava, R. Penicillium. In Bacteria and Fungi; Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology, 2020; pp. 651–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, B. A.; Hartge, K. H. Soil structure: its development and function; CRC Press, 1995; Vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Thepbandit, W.; Athinuwat, D. Rhizosphere Microorganisms Supply Availability of Soil Nutrients and Induce Plant Defense. Microorganisms 2024, 12(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, R. N.; Checinska Sielaff, A.; Hofmockel, K. S.; Xu, X.; Wayne Polley, H.; Wilsey, B. J.; Upton, R. N.; Sielaff, A. C.; Hofmockel, K. S.; Xu, X.; Polley, H. W.; Wilsey, B. J.; Peters, D. P. C. Soil depth and grassland origin cooperatively shape microbial community co-occurrence and function. Ecosphere 2020, 11(1), e02973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallance, J.; Déniel, F.; Le Floch, G.; Guérin-Dubrana, L.; Blancard, D.; Rey, P. Pathogenic and beneficial microorganisms in soilless cultures. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2011, 31:1, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, M.; Wolf, A. B.; Jennings, S. J.; Kowalchuk, G. A. Micro-scale determinants of bacterial diversity in soil. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2013, 37(6), 936–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Xie, P.; Yang, S.; Niu, G.; Liu, X.; Ding, Z.; Xue, C.; Liu, Y. X.; Shen, Q.; Yuan, J. ggClusterNet: An R package for microbiome network analysis and modularity-based multiple network layouts. In IMeta; STRING:PUBLICATION: PAGEGROUP, 2022; Volume 1, 3, p. e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D. C.; Suttont, S. D.; Ringelberg, D. B. The genus Sphingomonas: physiology and ecology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 1996, 7(3), 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Li, R.; Ren, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, H.; Jousset, A.; Shen, Q. Distinct roles for soil fungal and bacterial communities associated with the suppression of vanilla Fusarium wilt disease 2017. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Xu, W.; Wang, S.; Jiu, S. The role of strigolactones in the regulation of root system architecture in grapevine (Vitis vinifera l.) in response to root-restriction cultivation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(16), 8799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, M. M.; Guo, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, N.; Ning, D.; Shi, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wu, L.; Yang, Y.; Tiedje, J. M.; Zhou, J. Climate warming enhances microbial network complexity and stability. Nature Climate Change 2021, 4, 343–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, N. I.; Ismail, M. R.; Awang, Y.; Megat Wahab, P. E.; Berahim, Z. Effect of Root Restriction on the Growth, Photosynthesis Rate, and Source and Sink Relationship of Chilli (Capsicum annuum L.) Grown in Soilless Culture. BioMed Research International 2020, 2020(1), 2706937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, M.; Zhang, T.; Gao, H.; Ou, Y.; Li, M. Effects of biochar immobilization of Serratia sp. F4 OR414381 on bioremediation of petroleum contamination and bacterial community composition in loess soil. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2024, 470, 134137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yun, F.; Man, X.; Huang, D.; Liao, W. Effects of Hydrogen Sulfide on Sugar, Organic Acid, Carotenoid, and Polyphenol Level in Tomato Fruit. Plants 2023, 12(4), 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Laverman, A.; Mellage, A.; Furman, A. Microbial community structure and function in a sandy soil column under dynamic hydrologic regimes. Journal of Hydrology 2024, 643, 131797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Y.; Fang, H.; Li, W. Impact of altered groundwater depth on soil microbial diversity, network complexity and multifunctionality. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1214186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author (s) and contributor (s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor (s). MDPI and/or the editor (s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

Figure 3.

Substrate physical properties under different substrates and heights. a: bulk density; b: total water storage; c: water holding capacity.

Figure 3.

Substrate physical properties under different substrates and heights. a: bulk density; b: total water storage; c: water holding capacity.

Figure 4.

Tomato growth status under different substrates and heights. a: plant height; b: stem diameter; c: root activity; d: total chlorophyll content.

Figure 4.

Tomato growth status under different substrates and heights. a: plant height; b: stem diameter; c: root activity; d: total chlorophyll content.

Figure 5.

Tomato quality and yield under different substrates and heights. a: soluble sugar content; b: soluble protein content; c: lycopene content; d: single plant yield.

Figure 5.

Tomato quality and yield under different substrates and heights. a: soluble sugar content; b: soluble protein content; c: lycopene content; d: single plant yield.

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of root-restricted height with tomato phenotype and substrate physical properties. a: soil; b: sand; c: peanut shell substrate (PSS).

Figure 6.

Correlation analysis of root-restricted height with tomato phenotype and substrate physical properties. a: soil; b: sand; c: peanut shell substrate (PSS).

Figure 7.

a, b: Rhizosphere bacterial and fungal α diversity under different substrate types; c, d: Rhizosphere bacterial and fungal β diversity under different substrate types; e, f: Microbial relative abundance at phylum level for rhizosphere bacteria and fungi under different substrate types.

Figure 7.

a, b: Rhizosphere bacterial and fungal α diversity under different substrate types; c, d: Rhizosphere bacterial and fungal β diversity under different substrate types; e, f: Microbial relative abundance at phylum level for rhizosphere bacteria and fungi under different substrate types.

Figure 9.

Functional annotation of rhizosphere microbial communities at varying heights in PSS, sand, and soil. a: bacteria; b: fungi.

Figure 9.

Functional annotation of rhizosphere microbial communities at varying heights in PSS, sand, and soil. a: bacteria; b: fungi.

Figure 10.

Microbial networks in tomato rhizosphere under different substrates. a: bacteria in sand; b: bacteria in soil; c: bacteria in peanut shell substrate (PSS); d: fungi in sand; b: fungi in soil; c: fungi in peanut shell substrate (PSS).

Figure 10.

Microbial networks in tomato rhizosphere under different substrates. a: bacteria in sand; b: bacteria in soil; c: bacteria in peanut shell substrate (PSS); d: fungi in sand; b: fungi in soil; c: fungi in peanut shell substrate (PSS).

Figure 11.

a-c: Rhizosphere bacterial network graphs under different substrate heights. Large modules with ≥5 nodes are displayed in distinct colors, while smaller modules are shown in grey. a-c: Rhizosphere bacterial network graphs at varying heights; a: rhizosphere bacteria in sand, b: rhizosphere bacteria in soil, c: rhizosphere bacteria in PSS; d-i: Variations in topological properties of rhizosphere bacterial networks with height for sand, soil, and peanut shell substrate, including: L (d), n (e), Con (f), Average K (g), Average CC (h), RM (i). Slopes (b) and adjusted r2 and P values from linear regressions are shown. *0.01 < P ≤ 0.05; **0.001 < P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Figure 11.

a-c: Rhizosphere bacterial network graphs under different substrate heights. Large modules with ≥5 nodes are displayed in distinct colors, while smaller modules are shown in grey. a-c: Rhizosphere bacterial network graphs at varying heights; a: rhizosphere bacteria in sand, b: rhizosphere bacteria in soil, c: rhizosphere bacteria in PSS; d-i: Variations in topological properties of rhizosphere bacterial networks with height for sand, soil, and peanut shell substrate, including: L (d), n (e), Con (f), Average K (g), Average CC (h), RM (i). Slopes (b) and adjusted r2 and P values from linear regressions are shown. *0.01 < P ≤ 0.05; **0.001 < P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Figure 12.

a-c: Rhizosphere fungal network graphs under different substrate heights. Large modules with ≥5 nodes are displayed in distinct colors, while smaller modules are shown in grey. a-c: Rhizosphere fungal network graphs at varying heights; a: rhizosphere fungi in sand, b: rhizosphere fungi in soil, c: rhizosphere fungi in PSS; d-i: Variations in topological properties of rhizosphere fungal networks with height for sand, soil, and peanut shell substrate, including: L (d), n (e), Con (f), Average K (g), Average CC (h), RM (i). Slopes (b) and adjusted r2 and P values from linear regressions are shown. *0.01 < P ≤ 0.05; **0.001 < P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Figure 12.

a-c: Rhizosphere fungal network graphs under different substrate heights. Large modules with ≥5 nodes are displayed in distinct colors, while smaller modules are shown in grey. a-c: Rhizosphere fungal network graphs at varying heights; a: rhizosphere fungi in sand, b: rhizosphere fungi in soil, c: rhizosphere fungi in PSS; d-i: Variations in topological properties of rhizosphere fungal networks with height for sand, soil, and peanut shell substrate, including: L (d), n (e), Con (f), Average K (g), Average CC (h), RM (i). Slopes (b) and adjusted r2 and P values from linear regressions are shown. *0.01 < P ≤ 0.05; **0.001 < P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

Table 1.

TOPSIS scores and rankings for different substrates and root restriction heights treatment combinations.

Table 1.

TOPSIS scores and rankings for different substrates and root restriction heights treatment combinations.

| Substrate Type |

Root restriction height/cm |

|

Rank |

| Soil |

8 |

0.546505178 |

4 |

| 16 |

0.48164078 |

6 |

| 24 |

0.558187026 |

2 |

| Sand |

8 |

0.362008551 |

7 |

| 16 |

0.330355118 |

9 |

| 24 |

0.358958413 |

8 |

Peanut shell substrate

(PSS) |

8 |

0.631022083 |

1 |

| 16 |

0.552148447 |

3 |

| 24 |

0.520564663 |

5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).