1. Introduction

Hormonal imbalances affect women’s health across life stages, leading to symptoms such as abdominal pain, severe menstrual cramps, and heavy bleeding [

1,

2]. These conditions may lead to infertility and psychological impacts [

3,

4,

5].

Despite the significance of these issues, symptoms like dysmenorrhea are often overlooked in Japan, contributing to a long-term burden [

6]. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry [

7] estimates that productivity loss due to these symptoms amounts to 3.4 trillion yen annually. Approximately one-third of dysmenorrhea cases progress to endometriosis, which affects around 10% of reproductive-age women and is strongly associated with infertility [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Diagnosis of endometriosis remains challenging, with an average global delay of 6–12 years [

12,

13], while Japan-specific data remain limited [

14].

Diagnostic delay for endometriosis—the time from the onset to confirmed diagnosis—can lead to physical, psychological, and financial impacts throughout woman's life. These health conditions often cause irregular absences due to fatigue, making students miss academic activities, which in turn interfere with their educational progress and academic achievements. In Japan, menstrual-related symptoms, such as dysmenorrhea, are often overlooked due to cultural misconceptions that "menstrual pain is natural and should be endured” [

15,

16]. This contributes to delay in seeking consultation with a gynecologist (79.6%), enduring pain without any over-the-counter (OTC) drugs (67.0%), or preferring to take an OTC painkiller (35.9%) only when they have severe pain [

15]. This behavior, in turn, exacerbates the progression of dysmenorrhea to endometriosis. A study from Sweden highlighted how symptoms of dysmenorrhea and their impact on education, which often begins in adolescence, severely continue to hinder educational progress and career choices, directly affecting long-term economic outcomes [

17].

A systematic decision period for discriminating between a “short” and a “long” time for diagnosing endometriosis is still lacking. Surrey et al. (2020) [

18] divided the decision period, known as diagnostic delay interval, into three categories: short (≤ 1 year), intermediate (1–3 years) and long (3–5 years). They revealed that the population that experiences longer diagnostic delay had higher clinical burden and healthcare costs than those who experience shorter delays. Furthermore, Brandes et al. (2022) [

13] showed a diagnostic interval of 5 years as the median period of time for differentiating between a Short Diagnostic Delay (Short DD) and a Long Diagnostic Delay (Long DD) for endometriosis using several variables. The variables with the strongest power to predict membership in the short DD versus long DD group were age at first symptom onset (P < 0.001) and age at first consultation with a physician due to endometriosis-associated symptoms (P = 0.01). The findings suggest that in populations experiencing diagnostic delays, higher clinical burden and increased healthcare costs are associated with younger ages at first symptom onset and at first consultation with a physician.

Based on these findings, it is critical to address the impacts of diagnostic delay for endometriosis. Delayed therapeutic intervention after symptom onset may negatively affect women’s education and career. This approach has not been previously considered, and it is necessary to investigate whether diagnostic delays contribute to adverse outcomes in education, career development, and economic burden within the Japanese healthcare system.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study aimed to (1) examine the association between diagnostic delay in endometriosis and patient characteristics, and (2) determine the mean and median time from symptom onset to confirmed diagnosis.

An online survey was administered from September to October 2024 among Japanese women aged 18 to 49 years who had been diagnosed with endometriosis. Participants were recruited through Freeasy, an online panel developed by iBridge Co. Ltd. (Osaka, Japan), which is widely used in health-related research to identify individuals diagnosed with endometriosis, being diagnosed in approximately 10 % of reproductive women. Considering that 72% of Japanese women were eligible for individual income (according to the employment-to-population ratio of women aged between 15 and 64 [

12]), we anticipated conducting a screening survey with 5,000 participants to identify 360 eligible respondents, accounting for an expected 20% missing response rate [

13]. All participants were required to read a study information sheet and provide informed consent before participating. Only individuals who provided consent were allowed to complete the self-administered and anonymous questionnaire.

Informed by previous findings on diagnostic delay and disease [

17], we investigated trends in education, individual income, and expenditures among patients with early symptoms of endometriosis, including dysmenorrhea, pelvic pain, fatigue, and nausea. Analyses included descriptive statistics on endometriosis outcomes and economic status. The endometriosis-specific outcomes included healthcare behavior and experience of endometriosis patients. The collected data were subsequently analyzed to explore factors associated with diagnostic delay and economic and psychosocial impacts.

2.2. Participants and Sampling Strategy

The study aimed to recruit 220 participants diagnosed with endometriosis. This sample size was calculated based on a previous study in Germany, which included 157 participants for validating diagnostic delay cut-offs [

13]. Considering the reproductive-age female population (15–49 years) in Germany (15.65 million) and Japan (22.94 million), we adjusted the sample size using a ratio of 1:1.39. Factoring in an anticipated 20% rate of ineligible or incomplete responses, we set the recruitment target at 275 participants to ensure sufficient statistical power.

2.3. Ethics Statement

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of St. Luke’s International University (approval number: 24-R093). All participants provided informed consent online prior to participation, and the survey was conducted anonymously and followed the Declaration of Helsinki, as well as the Ethical Guidelines for Life Science and Medical Research Involving Human Subjects issued by the Government of Japan.

2.4. Survey Instrument and Development

The questionnaire in the present study was adapted from that used in the EndoCost study [

19], including the version applied by Brandes et al. (2022) [

13]. The study evaluated the economic burden of endometriosis across multiple centers in ten countries [

19]. The aim of the study was to gather information on a wide range of disease-specific parameters, healthcare costs and health-related quality of life of endometriosis patients from a societal perspective. The original 30-page questionnaire included items such as age at symptom onset, first consultation, age at diagnosis, income, healthcare costs, and other disease-related factors [

20].

2.5. Questionnaire Content

A 21-item questionnaire was developed with reference to the EndoCost study [

19,

20], covering sociodemographic and disease-specific parameters tailored to the Japanese context.

In

Section 1, participants provided demographic information, such as age, educational attainment, occupation, personal annual income, area of residence, marital status with or without child. Additionally, participants were asked to report the following questions regarding expenditures related to endometriosis:

1. Medical expenditure

“What is your average monthly medical expenses covered by public insurance over the past six months for the treatment of endometriosis at clinics or hospitals?”

2. Transfer fee

“What is the average monthly amount spent on transportation costs (including parking fees, gasoline expenses, etc.) for visits to medical institutions (clinics or hospitals)?”

3. Self-care fee

“How much do you spend on self-care for endometriosis?”

In

Section 2, participants were asked endometriosis-specific questions, such as awareness of symptoms with/without OTC drugs, age of initial symptom onset, first consultation with gynecologist and confirmed diagnosis of endometriosis, disease stage (if applicable), consultation person, pain intensity using a face scale, and experience of stigma regarding endometriosis.

2.6. Variable Classification and Analytical Plan

Participants were categorized into Short DD (<1.5 years) and Long DD (≥1.5 years) groups based on the median diagnostic delay, and associations with healthcare behavior-related variables were subsequently examined.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistical analysis was conducted for all variables[

8,

13,

21]. Between-group comparisons were performed using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. Cases with missing responses were excluded from the analysis [

13]. Multiple linear regression analyses were performed to assess associations between diagnostic delay, social stigma, and economic burden. All analyses were conducted using STATA software (version 18.0; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

A total of 5,000 women were initially screened to confirm a diagnosis of endometriosis. Among these, 371 women met the diagnostic criteria for endometriosis. Subsequently, eligibility criteria were applied, which required participants with individual income, leading to the exclusion of 48 individuals who did not meet this criterion. This process resulted in a preliminary cohort of 323 eligible participants. Of these, a total of 287 women with endometriosis completed the study questionnaire, corresponding to a response rate of 88.9%. Fourteen of these were excluded due to missing or unclear diagnostic delay data, and 53 participants with asymptomatic were also excluded, then a total of 220 endometriosis patients reported experiencing initial symptoms before being diagnosed with endometriosis were participated.

For the target population with symptoms, the mean age was 36.1 years old, with the majority falling in the age group of 30–40 years old (38.2%). Regarding marital status, 53.2% were married, 70.1% of whom had at least one child; 46.8% were unmarried, 8.7% of whom had at least one child, indicating the single-parent rate. In terms of annual income, the average annual income was 3.7 million JPY among this population. The Japanese average personal annual income is 4.6 million JPY [

22], which means 0.9 million JPY less among study population. Medical costs were calculated based on categorical variables derived from respondent-selected choices to account for variations; the average monthly medical expenditure calculated from the mean of the responses from 1 to 7 (mean 2.58) was JPY 5,160.

3.2. Endometriosis Specific Outcomes

Regarding endometriosis symptoms, it was essential to identify the timing of initial symptom onset and the age at diagnosis to characterize diagnostic delay. Differences between the diagnostic delay groups represent novel findings in the Japanese context.

Table 1 presents the results of the primary objective which showed the distribution of endometriosis specific outcomes and healthcare behavior. The difference of mean between the age of initial symptom onset confirmed diagnostic age was 3.6 years, which was a similar to China [

14]. Following consultation with a gynecologist, patients experienced a 1.3-year diagnostic delay for endometriosis from initial onset. However, there was a 2.1-year interval between the manifestation of initial symptoms and the consultation with a gynecologist; this difference is indicative of Japanese healthcare behavior. In contrast to a previous study [

16], this population predominantly comprised OTC-drug users. In terms of staging according to the ASRM score, the presence of stage I was the highest at 53.2% and stage IV was the second highest at 36.2%, indicating that staging was bilaterally segregated, although the number of participants was limited to 47 people (21.4%, compared with total population). The social stigma most commonly experienced by endometriosis patients [

21], as indicated by a survey, was the perception that `Pain is common' (25.9%).

3.3. Economic Situation of Patients with Endometriosis

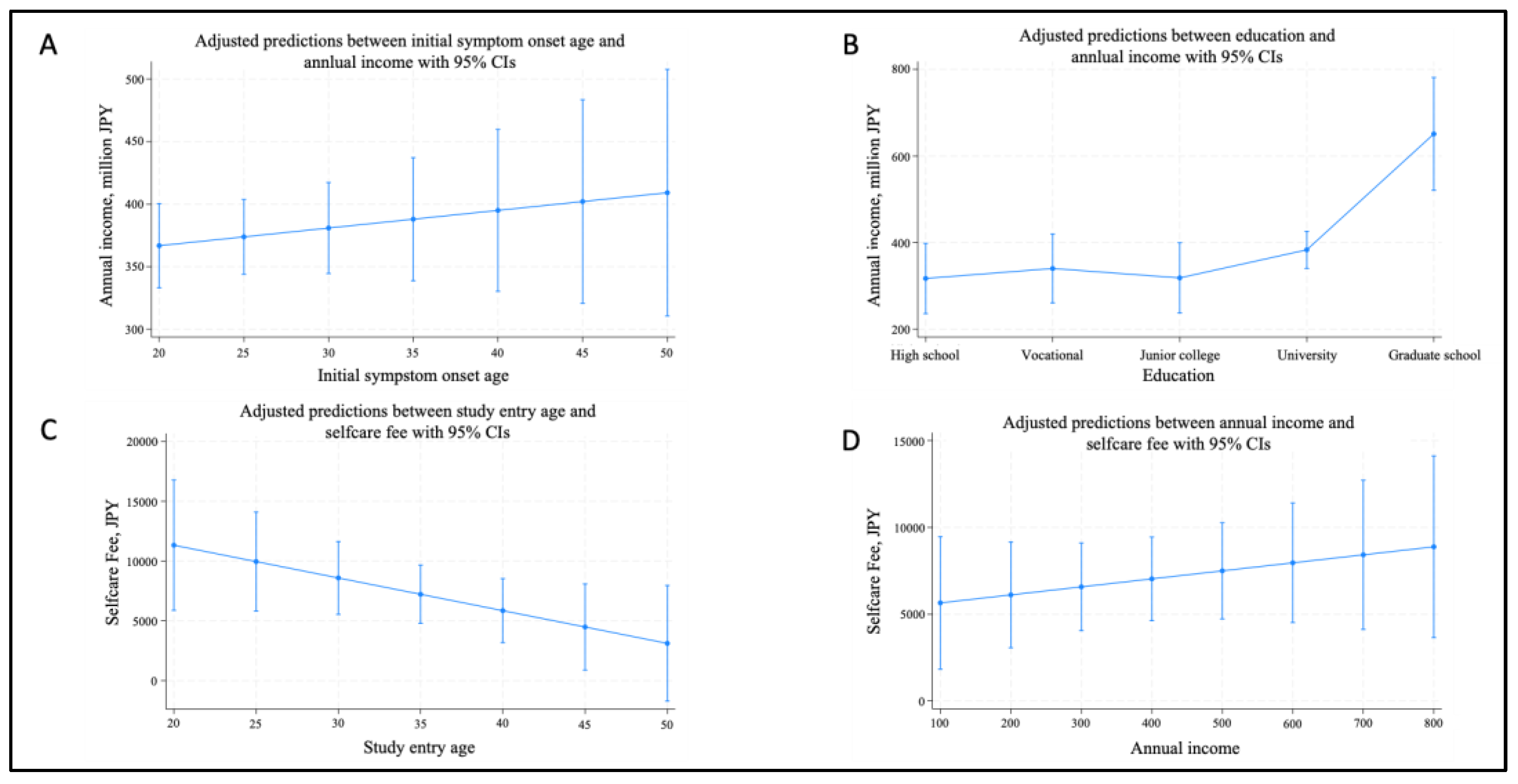

Figure 1 presents the regression analysis of predictive margins regarding the economic situation, which was also one of primary objective for endometriosis patients in this study. This figure included the following variables: age, age of symptom onset, and economic expenditures including medical expense, transfer fee, and self-care fee related to endometriosis. According to a previous Swedish research [

17], early symptom onset affected long-term educational and economic outcomes. Therefore, each variable included in the regression analysis model was identified based on the following demographic and economic variables: age, age of initial symptom onset, education, occupation, medical expense, transfer fee, self-care fee, OTC-drug use, and having a child.

Figure 1 also showed trends toward lower annual income with earlier symptom onset (A: P = 0.474) and higher self-care expenses among younger or higher-income participants (D: P = 0.395). However, none of these associations reached statistical significance. The group with a university degree or higher had a significantly higher annual income compared with the high school graduate group (B: P = 0.001**), indicating income differences based on educational attainment. The young generation had a significantly higher self-care expense for endometriosis, and the expense decreased significantly with increasing age (C: P = 0.044*), showing that the younger generation was likely to spend more on self-care than the older generation.

3.4. Exploration of Diagnostic Delay Cut-off Score

The second objective was to identify the mean and median diagnostic delay. The analysis of the initial symptom age and diagnostic age revealed a mean and median diagnostic delay (difference between diagnostic age and initial symptom age: mean = 3.6 years, median = 1.5 years, IQR = [min: 0, max: 24.3],

Table 2). Although we attempted to identify the diagnostic-delay group as a mean of two-category approach based on prior studies [

13,

14,

18], the diagnostic delay groupings were inappropriate for comparative analysis across study arms. Therefore, the median value of 1.5 years was used to classify participants into the Short DD and Long DD groups as outlined by Brandes et al (2022) [

13]. Participants with a diagnostic delay of ≤ 1.5 years were categorized as the Short DD group, while those with a delay of > 1.5 years were categorized as the Long DD group.

3.5. Association of Diagnostic Delay and Variables of Characteristics

As part of the analysis plan, comparisons between diagnostic delay groups (Short DD and Long DD) in terms of health behavior, education, occupation, income, and economic expenditure were conducted as shown in

Table 3. The P-values presented in this table are the results of univariate analysis, which assessed the statistical differences between the Short DD and Long DD groups for each variable. The results of the initial symptom age and first consultation age with gynecologist were significantly earlier age in Long DD group (P < 0.001, P = 0.003). The difference between initial symptom onset age and diagnosis age was statistically significant among Short DD and Long DD (P < 0.001). Individuals in the Long DD group were more likely to use OTC drugs (P = 0.011). The Long DD group also had a significantly higher marriage rate (P = 0.037). Expenditure of self-care fee was significantly higher in the Short DD group (P < 0.001).

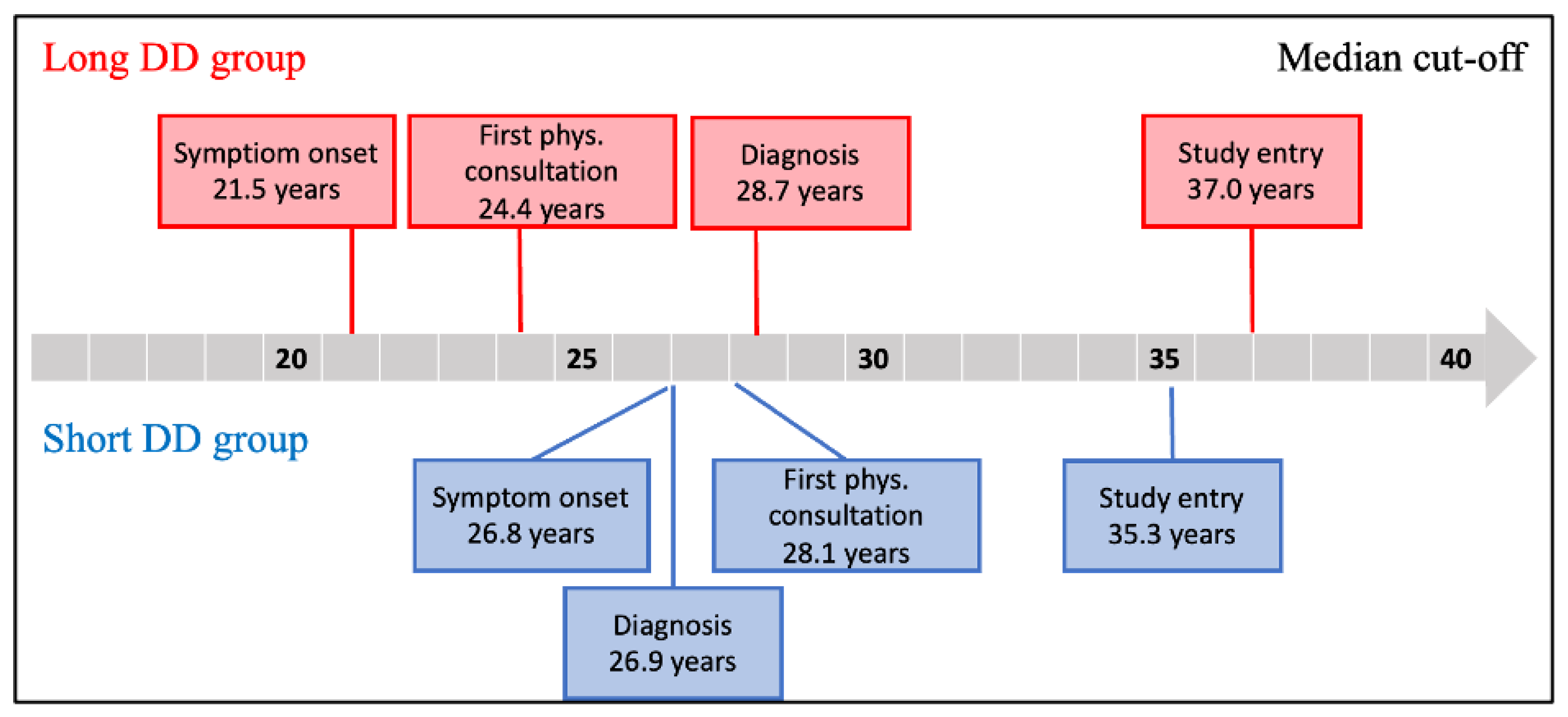

Progression from symptom onset to receiving a definitive diagnosis by a specialist is depicted for both the Short DD and Long DD groups in

Figure 2. The time scale of difference between age at symptom onset and age at consultation with a gynecologist was 2.7 years for Long DD and 1.3 years for Short DD (P = 0.02).

Endometriosis-related characteristics for each diagnostic delay group indicated that the distribution of endometriosis stages differs significantly between the Short DD and Long DD groups (P = 0.049). Stage I was more commonly observed in the Short DD group, whereas Stage IV was predominant in the Long DD group. On the other hand, the ASRM scores showed a higher trend in the Long DD group than the Short DD group (37.6 vs. 19.9) although the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.072). Consultation with medical staff showed a higher trend in the Long DD group, but it was not significantly different (P = 0.065). The face scale, which measures distress on a scale from 1 to 10, was significantly higher in the Long DD group than the Short DD group (4.16 vs. 3.48, P < 0.001).

Logistic regression was conducted to investigate factors associated with diagnostic delay (Short DD vs Long DD). Stepwise regression was performed to select variables related to association between diagnostic delay and characteristics, using a significance threshold of P < 0.05 to determine the model. The results of the logistic regression analysis using the selected variables are presented in

Table 4.

The results revealed that the odds of experiencing a long diagnostic delay decreased by 5% with every one-year increase in age at first consultation with a gynecologist, which was statistically significant (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.92–0.98, P = 0.002). The results also revealed the odds of OTC drug using was significantly higher in the Long DD group (P = 0.008). Participants with a Junior College education, had significantly higher odds of experiencing a long diagnostic delay compared to high school / vocational school (OR = 3.60, 95% CI = 1.36–9.53, P = 0.010). In contrast, participants with medium expense group (5,000-10,000 JPY / month) were likely to experience a short diagnostic delay compared with lower expense group, less than 3,000 JPY / month and 3,000-5,000 JPY / month (OR = 0.27, 95% CI = 0.11–0.66, P = 0.003). No other factors, including occupation, annual income, self-care fees or transfer fee, were significantly associated with diagnostic delay.

Table 5 shows the results logistic regression analysis examining the factors from each variable associated with Endometriosis-specific outcomes (Short DD vs Long DD). Stepwise regression was performed to select variables related to diagnostic delay and endometriosis specific outcomes, using a significance threshold of p < 0.05 to determine the model. The results of the logistic regression analysis using the selected variables revealed that those in Stage 4 of endometriosis had significantly higher odds of long diagnostic delay than those in Stage 1 (OR: 4.71, 95% CI = 1.25–17.79, P = 0.022).

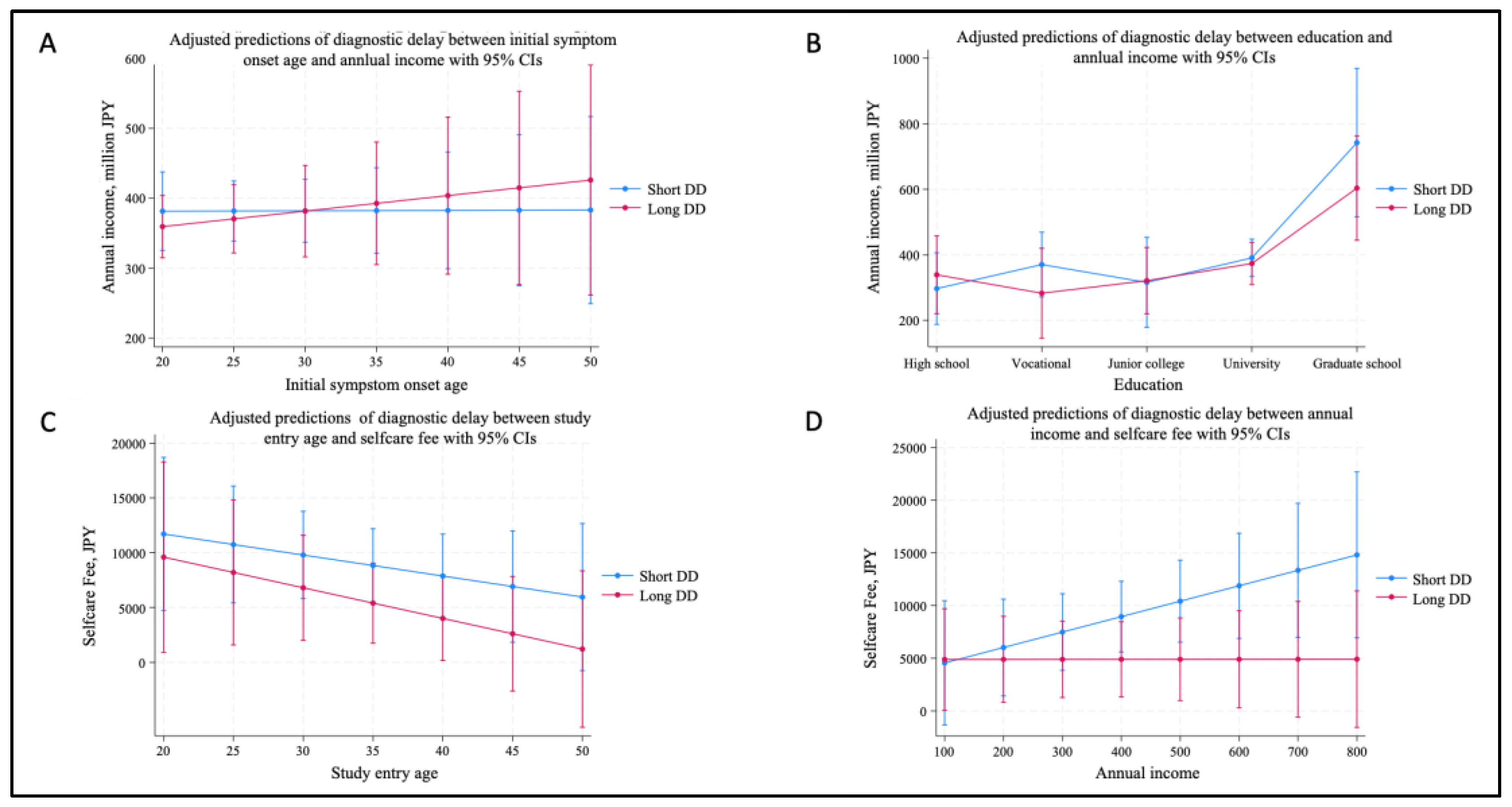

Figure 3 shows the results of the predictive margins for economic situation between Short DD and Long DD from Figures A to D: (A) Regression Coefficient of Initial symptom age towards annual income was -0.16 (P = 0.954). The earlier the age of initial symptoms, the lower the tendency for annual income in Long DD arm (P = 0.455); however, no statistically significant difference was observed; (B) Each educational group with Long DD showed negative coefficients compared to Short DD, suggesting that lower trends of annual income in the Long DD arm, but neither had significant difference; (C) Younger age in Short DD group tended to have higher self-care expenses, and consistently the expenses decrease with increasing age, but no statistically significant difference between Short DD and Long DD was observed (P = 0.863); and (D) The group in Short DD was shown to have higher self-care expenses with an increase in annual income. Statistical analysis was borderline (P = 0.063). Findings from

Figure 3 showed that there was no significantly difference in economic situation from the sights of early symptom age, educational attainment, selfcare fee and annual income.

4. Discussion

Our findings indicate a significant association between diagnostic delay, classification into the Long DD group, and several variables in logistic regression analysis. Specifically, patients experiencing a diagnostic delay of more than 1.5 years were significantly more likely to use OTC-drugs (Odds: 2.36, P = 0.008), have an educational background of Junior college (Odds: 3.60, P = 0.010), and present with Stage 4 disease (Odds: 4.71, P = 0.022), all of which had an odds ratio exceeding 2.30. Healthcare behavior regarding the time scale until consultation with specialists between Long DD and Short DD revealed significantly difference (P = 0.02). This behavior may stem from stigma that 'pain is common' (25.9%), delaying gynecological consultation in Japan. Conversely, older age at the first consultation with a specialist and higher healthcare expenditures were associated with a shorter diagnostic delay. These findings imply that severe endometriosis cases might be prevalent among Junior college participants, who in our study were taking OTC-drugs for pelvic pain. Although this interpretation is based on self-reported survey data, the possibility that disease progression may occur while pain is being alleviated with OTC drugs cannot be ruled out, potentially leading to delayed medical consultation and diagnosis.

By contrast, unlike the previous Swedish study [

17,

23], our study did not demonstrate a significant association between early age symptom onset and education or economic situation. However, from

Figure 1 and

Figure 3, our study suggests a trend of earlier symptom onset in endometriosis and lower annual income—particularly among those with longer diagnostic delays—even though the differences were not statistically significant. This may be due to differences in sample size and educational background between the two studies. The Swedish study revealed that patients had refrained from or quit their education due to their endometriosis over 30% in younger age group (< 30 years old). However, the participants in our study didn’t take the same questionnaires.

4.1. Determination of the Diagnostic Delay by Median Cut-Off

In our study, the diagnostic delay interval was 1.5 years, determined based on the median age cut-offs of diagnostic delay, while the average age cut-off of diagnostic delay was found to be 3.6 years (SD: 5.2), which was consistent with previous studies [

13,

18]. However, an uneven distribution between Short DD (n=152) and Long DD (n=68) groups indicated bias towards Short DD, if we chose the average age cut-offs. Therefore, it is recommended to use the median value for defining a cut-off age, based on the findings from a study by Brandes, et al. (2022) [

13]. Our study used median cut-off values as a baseline, with each arm having over 100 participants (n=114 vs 106 for Short DD vs Long DD, respectively), allowing for valid statistical analysis.

4.2. The Impact of Early Symptom Onset and OTC Drug Use on Healthcare Behavior

Group comparisons clearly show that women in the Long DD group were significantly younger (roughly more than 5 years younger) at the time of the first symptom onset than those in the Short DD group. The German population of the EndoCost study also revealed that the strongest association of age at symptom onset was with the total period from age at symptom onset to confirmed diagnosis: the younger the age at symptom onset, the longer the total diagnostic delay. In addition, our study found that patients in the Long DD group tended to use OTC drugs more frequently, which may contribute to the postponement of professional medical consultation. Although the use of OTC drugs did not directly impact endometriosis stage progression, it is plausible that temporary pain relief as OTC drugs may delay consultation with a specialist, potentially leading to exacerbation of the condition. This association between the use of OTC drugs and stage progression could not be established directly in this study, warranting further investigation.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot establish causal relationships between health behavior and endometriosis. The observed associations merely reflect associations at a single time point, and the temporal relationship remains unclear. Second, the results are self-reported, which introduces potential recall bias. Participants may misremember or misestimate key information, such as healthcare expenditures and potentially affecting the accuracy of the findings. Third, the diagnosis of endometriosis itself is also self-reported, lacking confirmation through medical records or clinical evaluation. This might lead to misclassification or overrepresentation of the condition. Fourth, potential confounding factors remain unaddressed, as detailed information on variables such as socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and access to healthcare was not collected. These unmeasured confounders could potentially bias the results. Fifth, this study was conducted with a relatively small and limited sample size of 220 participants, and the distribution of participants across prefectures was uneven. Sixth, this study was limited to individuals with individual income, which could introduce bias by excluding individuals without independent income, such as those relying solely on household income. This aspect was not thoroughly analyzed and presents an opportunity for further investigation. Future studies should address these limitations by incorporating a longitudinal design, larger and more representative sample sizes, and an exploration of the influence of household income dynamics on healthcare expenditures.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the association between diagnostic delay and health behavior of endometriosis patients, focusing on their disease management. The definition of diagnostic delay interval in our study was determined based on a median cut-off period of 1.5 years.

The longer diagnostic delay indicates a potential reliance on self-management with OTC drug using, which may contribute to the postponement of professional medical consultation. Early intervention strategies, such as routine screenings and awareness programs, could help patients seek medical attention earlier and potentially reduce the burden of advanced disease. Future research should prioritize clinical assessment alongside pain management to reduce silent progression and improve long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org,

Table A1: Participants’ area of residence.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of St. Luke’s International University (approval number: 24-R093 and date of approval: September 30th, 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical and privacy considerations. Participants were explicitly assured that their responses would remain anonymous and confidential, in accordance with the approved research protocol and institutional ethics guidelines. However, de-identified data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, subject to approval by the Institutional Review Board of St. Luke’s International University.

Acknowledgments

My deepest appreciation and gratitude to my supervisor, Dr. Satomi Sato who is an Associate Professor of Division of Health and Behavioral Sciences in the Graduate School of Public Health at St. Luke’s International University, for her unwavering and thoughtful support throughout this research. Her expertise and meticulous attention to detail were invaluable in helping me stay focused and complete this research project. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author used no GenAI for any purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ASRM score |

The American Society for Reproductive Medicine score |

| Long DD |

Long Diagnostic Delay |

| OTC drug |

Over The Counter drug |

| Short DD |

Short Diagnostic Delay |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

Table A1 presents the geographical distribution of participants with symptomatic endometriosis across Japan's prefectures. Among the 220 participants, the highest proportion resided in Tokyo (20.5%), followed by Aichi (7.7%), Osaka (7.3%), and Hokkaido (7.3%). Prefectures with the lowest representation included Iwate, Akita, Yamagata, Fukui, and Okinawa, each contributing 0.5% of the participants. This distribution highlights the wide geographic spread of the study population, encompassing both urban and rural regions across Japan.

Table A1.

Participants’ area of residence.

Table A1.

Participants’ area of residence.

| Prefecture |

n (%) |

Prefecture |

n (%) |

Prefecture |

n (%) |

| Hokkaido |

16 (7.3) |

Toyama |

3 (1.4) |

Shimane |

2 (0.9) |

| Iwate |

1 (0.5) |

Ishikawa |

3 (1.4) |

Okayama |

1 (0.5) |

| Miyagi |

5 (2.3) |

Fukui |

1 (0.5) |

Hiroshima |

4 (1.8) |

| Akita |

1 (0.5) |

Yamanashi |

2 (0.9) |

Yamaguchi |

2 (0.9) |

| Yamagata |

1 (0.5) |

Nagano |

3 (1.4) |

Tokushima |

1 (0.5) |

| Fukushima |

3 (1.4) |

Shizuoka |

2 (0.9) |

Kagawa |

1 (0.5) |

| Ibaraki |

5 (2.3) |

Aichi |

17 (7.7) |

Ehime |

2 (0.9) |

| Tochigi |

4 (1.8) |

Mie |

1 (0.5) |

Fukuoka |

11 (5.0) |

| Saitama |

6 (2.7) |

Kyoto |

7 (3.2) |

Kumamoto |

3 (1.4) |

| Chiba |

15 (6.8) |

Osaka |

16 (7.3) |

Oita |

1 (0.5) |

| Tokyo |

45 (20.5) |

Hyogo |

13 (5.9) |

Miyazaki |

1 (0.5) |

| Kanagawa |

11 (5.0) |

Nara |

4 (1.8) |

Kagoshima |

2 (0.9) |

| Niigata |

2 (0.9) |

Tottori |

1 (0.5) |

Okinawa |

1 (0.5) |

| |

|

|

|

Total |

220 (100.0) |

References

- Akande V.A., Hunt LP, Cahill DJ, Jenkins JM., Differences in time to natural conception between women with unexplained infertility and infertile women with minor endometriosis. Human Reproduction, 2004. 19(1): p. 96-103. [CrossRef]

- Johnson N.P., Farquhar CM, Hadden WE, et al., The FLUSH Trial—Flushing with Lipiodol for Unexplained (and endometriosis-related) Subfertility by Hysterosalpingography: a randomized trial. Human Reproduction, 2004. 19(9): p. 2043-2051. [CrossRef]

- Rooney K.L. and A.D., Domar, The relationship between stress and infertility. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2018. 20(1): p. 41-47. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A. and D. Shrivastava, Psychological Problems Related to Infertility. Cureus, Published online October 15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Facchin F, Giussy Barbara, Emanuela Saita, et al., Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and mental health: pelvic pain makes the difference. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2015. 36(4): p. 135-141.

- Health and Global Policy Institute. Research Survey on Socioeconomic Factors and Women’s Health (March 6, 2023). Accessed May 16, 2024. https://hgpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2023_WomensHealthResearchReport_JPN.pdf.

- Healthcare Industry Unit. Estimates of economic losses due to health issues specific to women: Economic losses such as labor losses due to health issues specific to women are estimated to be about 3.4trillion yen in society as a whole. Accessed November 10, 2024. https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/mono_info_service/healthcare/downloadfiles/jyosei_keizaisonshitsu.pdf.

- Biasioli A, Silvia Zermano, Francesca Previtera, et al., Does Sexual Function and Quality of Life Improve after Medical Therapy in Women with Endometriosis? A Single-Institution Retrospective Analysis. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 2023. 13(12). [CrossRef]

- Lamvu G, Antunez-Flores O, Orady M, Schneider B., Path to diagnosis and women’s perspectives on the impact of endometriosis pain. Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders 2020; 12(1):16-25. [CrossRef]

- Khine YM, Taniguchi F, Harada T., Clinical management of endometriosis-associated infertility. Reproductive medicine and biology 2016; 15:217-225. [CrossRef]

- Arakawa I, Momoeda M, Osuga Y, et al., Cost-effectiveness of the recommended medical intervention for the treatment of dysmenorrhea and endometriosis in Japan. Cost Effectiveness and Resource Allocation 2018; 16(1). [CrossRef]

- Statistics Bureau. Summary of Key Statistics from the Labour Force Survey (Basic Tabulation) 2022. Accessed December 1, 2024. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/sokuhou/nen/ft/pdf/index1.pdf.

- Brandes I, Kleine-Budde K, Heinze N, et al., Cross-sectional study for derivation of a cut-off value for identification of an early versus delayed diagnosis of endometriosis based on analytical and descriptive research methods. BMC Women's Health 2022; 22(1). [CrossRef]

- Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, et al., Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertility and Sterility 2011; 96(2):366-373.e368. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka E, Momoeda M, Osuga Y, et al., Burden of menstrual symptoms in Japanese women: results from a survey-based study. Journal of Medical Economics 2013; 16(11):1255-1266. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka E, Momoeda M, Osuga Y, et al., Burden of menstrual symptoms in Japanese women - an analysis of medical care-seeking behavior from a survey-based study. International Journal of Women's Health 2013:11. [CrossRef]

- Söderman L, Edlund M, Marions L., Prevalence and impact of dysmenorrhea in Swedish adolescents. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 2019; 98(2):215-221. [CrossRef]

- Surrey E, Soliman AM, Trenz H, et al., Impact of Endometriosis Diagnostic Delays on Healthcare Resource Utilization and Costs. Advances in Therapy 2020; 37(3):1087-1099. [CrossRef]

- Simoens S, Dunselman G, Dirksen C, et al., The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Human Reproduction 2012; 27(5):1292-1299. [CrossRef]

- Simoens S, Hummelshoj L, Dunselman G, et al., Endometriosis Cost Assessment (the EndoCost Study): A Cost-of-Illness Study Protocol. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 2010; 71(3):170-176. [CrossRef]

- Sims OT, Gupta J, Missmer SA, et al., Stigma and Endometriosis: A Brief Overview and Recommendations to Improve Psychosocial Well-Being and Diagnostic Delay. MDPI AG; 2021. [CrossRef]

- National Tax Agency. Salaried workers who worked throughout the year. Accessed November 25, 2024. https://www.nta.go.jp/publication/statistics/kokuzeicho/minkan2000/menu/03.htm.

- Lövkvist L, Boström P, Edlund M, et al., Age-related differences in quality of life in Swedish women with endometriosis. Journal of women's health 2016; 25(6):646-653. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).