1. Introduction

Endometriosis is the second most common gynaecological condition, affecting about 10% of women of reproductive age [

1]. It is characterised by the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus, triggering a chronic inflammatory reaction. The main manifestations are chronic pelvic pain and infertility, but the impact of the disease goes beyond the physical sphere. Women with endometriosis have an increased risk of mental disorders – especially anxiety and depression – compared to the general population [

2,

3]. Chronic pain associated with endometriosis contributes to dysfunctions in neuroendocrine regulation (e.g. in the hippocampus and amygdala), being correlated with increased rates of anxiety and depression [

4]. These psychological symptoms significantly reduce the quality of life of patients and can create a vicious circle in which mental stress aggravates the perception of pain and vice versa [

5].

A psychological aspect specific to patients with chronic diseases is the fear of progression – the persistent fear that the disease will worsen or relapse in the future. Initially described in cancer patients, the fear of progression has recently been highlighted in patients with endometriosis. A 2023 study [

6] showed that scores on the fear of progression questionnaire are, on average, higher in women with endometriosis than those reported in patients with malignancies. This anxiety about the course of the disease can contribute to insomnia and fatigue and interfere with daily functioning [

7]. However, the factors that can influence the intensity of the fear of progression in endometriosis are not fully understood.

The relationship between the treatment strategy and the patient's psychology is a topic of clinical interest. On the one hand, surgery can reduce the disease burden by removing the lesions, possibly relieving anxieties related to the disease. On the other hand, conservative (hormonal) treatment prolongs the long-term management of the disease without a surgical "resolution", which could leave the patient with uncertainties about the evolution. It is not clear whether certain therapeutic approaches can diminish or, on the contrary, amplify the fear of progression. Also, age or previous experiences may play a role in how patients perceive the risk of disease progression.

This study aimed to evaluate the impact of different treatment modalities on the level of fear of progression in patients with endometriosis. We set out to compare the degree of concern about the evolution of the disease (measured by the FoP-Q-SF score) between four groups of patients, defined by the therapeutic strategy (hormonal, surgical, or combined). We also aimed to determine whether age influences the relationship between the type of treatment and fear of progression.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This prospective observational study was conducted at Endoinstitut–Regina Maria Hospital, Timisoara, from December 1, 2023, to March 30, 2024. Inclusion criteria were adult women (≥18 years) diagnosed laparoscopically or via imaging with endometriosis who provided informed consent. A total of 298 patients were included. They were grouped into four cohorts, depending on their treatment plan at the time of inclusion in the study:

Group 1: Patients undergoing exclusively hormonal treatment without indication for surgery.

Group 2: Patients undergoing hormone treatment who had an indication for surgery.

Group 3: Patients with an indication for surgery who were not undergoing hormonal treatment (e.g. prepared for surgery or who refused hormone therapy).

Group 4: Patients who refused hormone therapy and opted for alternative treatments (e.g. phytotherapy), who had not yet undergone surgery.

2.2. Procedures and Instruments

At the time of inclusion, all participants completed a form that included demographic data (age, marital status, number of children, history of the disease) and the Fear of Progression Questionnaire – Short Form (FoP-Q-SF) [

8]. This validated tool for chronic diseases includes 12 items on concerns about the course of the disease, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 – "never", 5 – "very often"). A total score (sum or average) is calculated, with higher values indicating a more pronounced fear of disease progression. We also recorded responses to each item of the FoP-Q-SF questionnaire to identify the most intense specific areas of concern (e.g., fear of pain, concern about effects on family, body image, etc.).

2.3. Data Analysis

Data collected and curated in Microsoft Excel (Office 2021) was further analysed using the JASP (v. 0.19.1.0) open-source application. A descriptive analysis of patients' baseline characteristics and FoP-Q-SF scores was performed in each group (means, standard deviation, item medians). Group comparability was assessed by appropriate tests (ANOVA or nonparametric equivalent) for key demographic variables. As the Levene test showed an uneven variance of FoP-Q-SF scores between groups (p = .01), a non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was chosen to compare the distributions of total FoP-Q-SF scores between the four groups. In case of significant overall difference, the Dunn post-hoc test for pair comparisons was applied, with adjustment of the significance level by Bonferroni correction. To assess the potential influence of age on the observed differences, a covariance analysis (ANCOVA) was used, with age as the covariate, with the FoP-Q-SF score as the dependent variable and the treatment group as an independent factor. The threshold of statistical significance was set at α = .05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

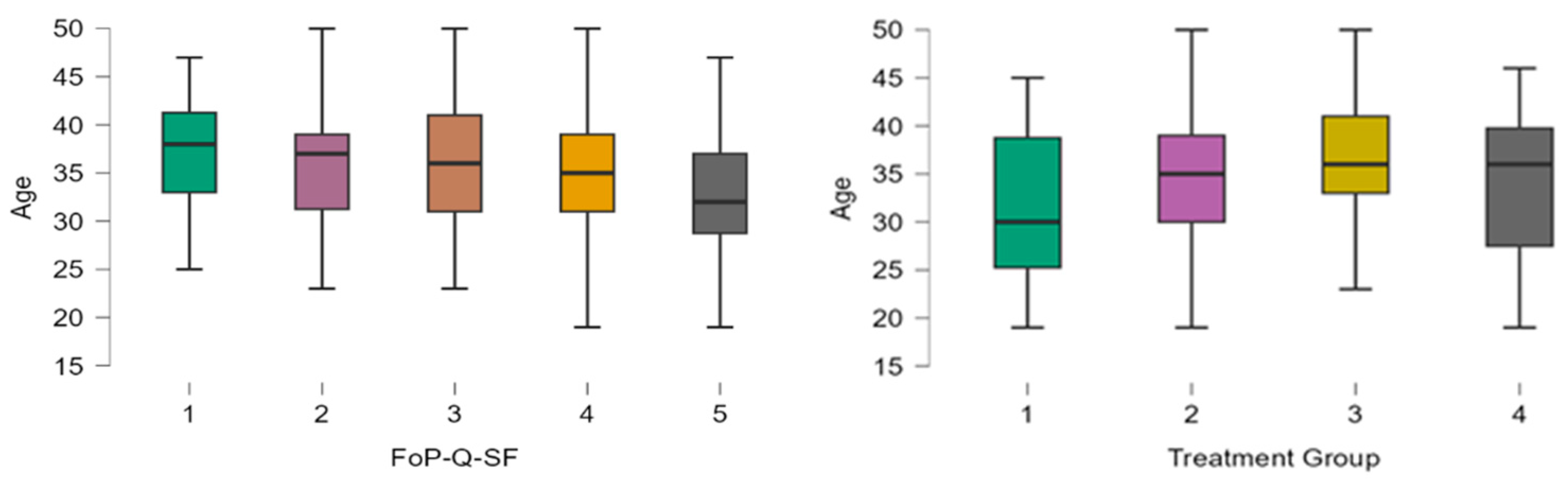

The clinical trial data reveals notable demographic variations among the four treatment groups. The age range spans from 20 to 51 across all groups, with the average age varying between 31.9 years for group 1 and 36.4 years for group 3. Thus, patients with surgical indications and no hormonal treatment tend to be older on average compared to those with hormonal treatment and no surgery indication, who are the youngest. The analysis of patient age distribution across different FoP-Q-SF scores revealed an inverse relationship between age and fear of progression, with younger patients consistently reporting higher FoP scores (

Figure 1). Specifically, patients exhibiting the highest level of fear (FoP score = 5) had a mean age of approximately 32.6 years, while those reporting the lowest fear levels (FoP score = 1) had a mean age of 37.5 years. This finding emphasises younger age as a significant factor associated with increased anxiety regarding disease progression.

The difference between the lowest and highest average scores between treatment groups was relatively small, with all groups being above the level considered problematic in the literature (score ≥ 34 out of 60, equivalent to 2.8 out of 5) [

9].

The distribution of patients among treatment groups is not uniform; most belong to groups 2 (128, 42.9 %) and 3 (122, 40.9%)

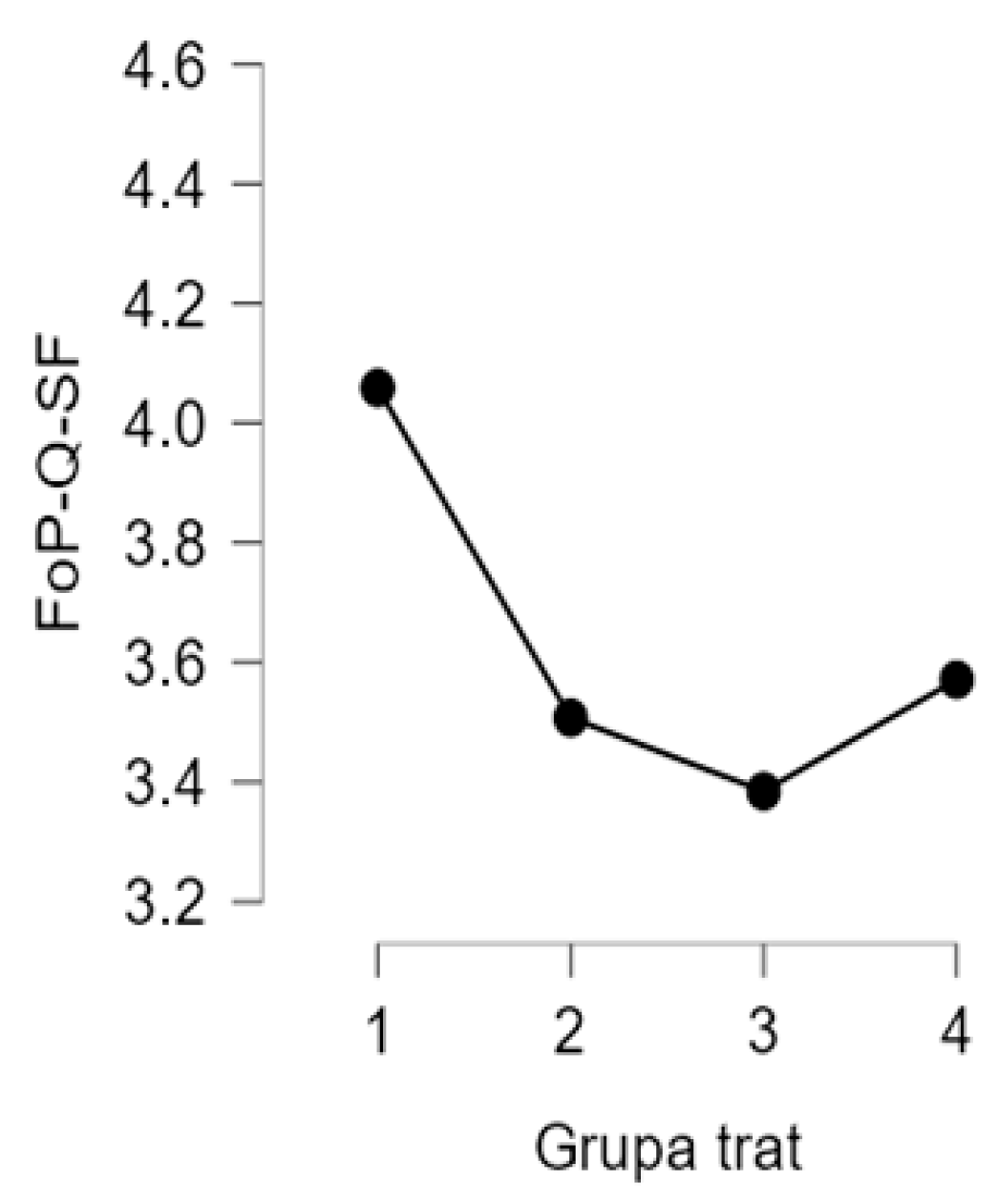

Regarding FoP-Q-SF scores, the level of fear of progression was high overall, with a median across the entire study population of 4 (on a scale of 1–5), corresponding to a moderate-high level of concern. Comparing between groups, Group 1 (hormone treatment only) recorded the highest mean FoP-Q-SF SCORE (4.06), followed by Group 4 (3.57) and Group 2 (3.51). Group 3 had the lowest average level of fear (3.38) (

Figure 2).

Analysis of individual items in the questionnaire revealed that the most intense concerns among patients were fear of medical procedures (e.g., anxiety before an intervention or check-up) and the impact of the disease on body image (concerns about physical changes caused by the disease or treatment). Both had a median response of 4 ("often") out of 5, indicating a high level of concern. In contrast, concern that the disease could be passed on to children (heredity concern) was the lowest, with a median of 2 ("rare"). Other aspects, such as fear of future chronic pain or decreased performance at work, had intermediate levels of concern, with medians between 3 and 4.

3.2. Comparison of Scores Between Groups

The Kruskal-Wallis test applied to the FoP-Q-SF total scores indicated statistically significant differences between the four treatment groups (χ^2 = 9.7, p = .021). This result suggests that at least one group differs from the others in terms of the level of fear of progression. The post-hoc analysis (Dunn with Bonferroni correction) showed that: Group 1 (hormonal, non-surgical) has a significantly higher FoP-Q-SF score than Group 3 (surgical, non-hormonal) – median difference ~0.7 points on scale 1–5, p = .002. Group 1 also has significantly higher scores than Group 2 (hormonal + surgical) – median difference ~0.4, p = .014. No other comparison between pairs of groups reached the threshold of statistical significance (i.e. the differences between groups 2 vs 3, 1 vs 4, 2 vs 4, 3 vs 4 were not significant).

These results indicate that patients under hormone treatment alone, without planned surgery, have higher levels of fear of progression than patients who are being considered or have undergone surgery. The most pronounced difference was between the hormone-only treatment group and the surgical approach group without hormone therapy, where the fear level was significantly lower.

3.3. Adjusted Analysis (ANCOVA)

Given that the groups showed age differences, we also performed an ANCOVA analysis to adjust the FoP-Q-SF scores according to age. Including age as a control variable, the differences between treatment groups remained significant. In the ANCOVA model, belonging to group 1 (hormone treatment only) was associated with a significantly higher FoP-Q-SF score compared to group 2 (coefficient of -0.48, p = .028) and group 3 (coefficient of -0.54, p = .014). This confirms that groups 2 and 3 have significantly lower scores than group 1, even after age adjustment. Age itself had a significant negative association with the FoP-Q-SF score (coefficient -0.03 per year, p = .004), indicating that, regardless of the treatment group, younger patients tend to have a higher fear of progression than older ones.

In summary, the quantitative results emphasise two main aspects: (1) the type of treatment followed in endometriosis is associated with differences in the level of fear of progression, hormone-only therapy being linked to more significant anxiety about the evolution of the disease; (2) The age of the patients is inversely proportional to the intensity of this fear, the young ones being a more vulnerable group from this point of view.

4. Discussion

The present study highlights how specific clinical factors can influence the psychological perceptions of patients with endometriosis. We found that patients under hormone treatment alone, without surgery, show the highest fear of progression compared to the other groups. This result suggests a link between the absence of an immediate surgical solution and an increased level of anxiety about the disease. In endometriosis, surgery (e.g., laparoscopy to excise lesions) is often perceived as an essential step toward relief or even temporary "healing." The fact that patients in group 3 (with an indication for surgery) had much lower levels of fear compared to group 1 indicates a possible beneficial psychological effect of the prospect of a surgical solution: they know that their disease will be addressed directly, reducing uncertainty. In contrast, patients in group 1, who are only on hormone therapy, may feel that the disease is only temporarily controlled and that the risk of progression persists, which fuels anxiety.

Age was another important factor: younger patients had a more pronounced fear of progression. This observation is consistent with data from oncology, where young patients frequently report a greater fear of recurrence/progression than older patients [

10]. In the case of endometriosis, young women (often without children) may be particularly concerned about the impact of the disease on fertility and life plans, which explains the increased level of anxiety. Also, with age, better-coping mechanisms and a greater acceptance of uncertainties can appear, diminishing fears related to the disease in elderly patients. Our results confirm that fear of progression is a real problem in patients with endometriosis and aligns with the current literature. For example, Todd et al. (2023) reported high FoP scores in women with endometriosis, even higher than those seen in cancer patients. Pickup et al. (2024) highlighted that fear of progression contributes, along with depression, to the onset of fatigue and insomnia, exacerbating the negative impact of chronic pain. These findings suggest that anxiety about the evolution of the disease is not just an epiphenomenon but a factor that can amplify suffering and dysfunction, thus becoming a legitimate target for intervention.

From a practical perspective, identifying groups of patients at higher risk of anxiety (in our case, those treated exclusively hormonally and younger patients) allows for targeted interventions. First of all, effective communication with these patients regarding the treatment plan and prognosis is crucial. A clear explanation of the reasons for opting for hormone therapy and future options (including surgery if it becomes necessary) can reduce uncertainty and feelings of helplessness. Lack of communication and focus on the patient's needs can strain the doctor-patient relationship and intensify anxiety [

11]. Secondly, the integration of psychological interventions for patients with high levels of fear should be considered. Psychological counseling or cognitive-behavioral therapy, as well as mind-body therapies (meditation, yoga, relaxation techniques) have shown promise in relieving pain and emotional distress in endometriosis [

12]. Although the evidence is not yet definitive, including a psychologist in the multidisciplinary team can help develop patients' coping mechanisms and reduce anxieties related to the disease.

One aspect to discuss is that patients in Group 4 (who refused hormone therapy) did not present a significantly different fear profile. Although their numbers were small, their FoP-Q-SF scores were in the middle range, similar to the other groups. This could indicate the existence of individual factors (e.g. attitudes towards treatment, personality) that moderate anxiety levels. Some patients may refuse hormones for fear of adverse effects, but not necessarily out of a fear of disease progression; others, on the contrary, may be very little anxious and confident in alternative methods. Without additional qualitative data, these interpretations remain speculative.

Limitations. The study's main limitation is its cross-sectional nature, which does not allow causal relationships to be established. We cannot exclude that some patients with higher anxiety preferred or were referred to specific treatments. However, therapeutic decisions were made clinically, minimising this bias. We also did not systematically assess the severity of pain, the stage of endometriosis or the presence of other mental comorbidities, factors that can influence both the choice of treatment and the level of fear. Another limitation is the lack of follow-up of patients over time. We do not know how the fear of progression would evolve after therapeutic interventions (for example, if it decreases after surgery or if it increases in the absence of symptom improvement). Future longitudinal studies could clarify these aspects.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights that fear of progression is common among patients with endometriosis and varies depending on the therapeutic approach. Those treated with hormone therapy alone have the highest levels of fear about the evolution of the disease, while patients who undergo surgery (or are considering an intervention) tend to be less anxious from this perspective. Young patients are also more susceptible to progression anxiety compared to older patients.

These findings underscore the need for an integrated approach to endometriosis management that addresses both the physical and emotional components. In addition to treating injuries and relieving somatic symptoms, it is necessary to support patients through counselling and interventions aimed at reducing anxiety and increasing the feeling of control. Multidisciplinary care – involving gynaecologists, surgeons, psychologists, and pain medicine specialists – is ideal for breaking the vicious circle between pain and mental suffering and improving quality of life. By recognising and addressing the fear of progression, we can provide truly patient-centred care aligned with the principles of personalised and humanistic medicine in endometriosis.

Funding

This research received no external funding. I would like to acknowledge Victor Babes University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara for covering the publication costs (APF) for this research paper.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Endoinstitut - Regina Maria Timisoara.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the raw data supporting this article's conclusions available upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the contribution of colleagues from the Endoinstitute and Regina Maria Hospital in this study's initial planning and data collection phases. Special thanks are extended to Dr. Alexandra Andreea Poienar, Romeo Micu, Carmen Ciontu, Corina Cristea, and Voicu Caius Simedrea for their support in carrying out this study. We also express gratitude to the patients who participated in it for their availability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data, the writing of the manuscript, or the decision to publish the results.

References

- van Stein K, Schubert K, Ditzen B, Weise C. Understanding Psychological Symptoms of Endometriosis from a Research Domain Criteria Perspective. J Clin Med. 2023;12(12):4056. [CrossRef]

- Carbone MG, Campo G, Papaleo E, et al. The Importance of a Multi-Disciplinary Approach to the Endometriotic Patients: The Relationship between Endometriosis and Psychic Vulnerability. J Clin Med. 2021;10(8):1616. PMID: 33920306. [CrossRef]

- Koller D, Pathak GA, Wendt FR, et al. Epidemiologic and Genetic Associations of Endometriosis With Depression, Anxiety, and Eating Disorders. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2251214. PMID: 36652249. [CrossRef]

- Li T, Mamillapalli R, Ding S, et al. Endometriosis alters brain electrophysiology, gene expression and increases pain sensitization, anxiety, and depression in female mice. Biol Reprod. 2018;99(2):349–359. PMID: 29425272. [CrossRef]

- Sherwani S, Khan MWA, Rajendrasozhan S, et al. The vicious cycle of chronic endometriosis and depression—an immunological and physiological perspective. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1425691. [CrossRef]

- Todd J, Pickup B, Coutts-Bain D. Fear of progression, imagery, interpretation bias, and their relationship with endometriosis pain. Pain. 2023;164(12):2839–2844 PMID: 37530656.

- Pickup B, Coutts-Bain D, Todd J. Fear of progression, depression, and sleep difficulties in people experiencing endometriosis pain: A cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2024;178:111595. PMID: 38281472.

- Herschbach, P.; Berg, P.; Dankert, A.; Duran, G.; Engst-Hastreiter, U.; Waadt, S.; Keller, M.; Ukat, R.; Henrich, G. Fear of progression in chronic diseases—Psychometric properties of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire. J. Psychosom. Res. 2005, 58, 505–511.

- Peikert ML, Inhestern L, Krauth KA, Escherich G, Rutkowski S, Kandels D, Schiekiera LJ, Bergelt C. Fear of progression in parents of childhood cancer survivors: prevalence and associated factors. J Cancer Surviv. 2022 Aug;16(4):823-833. PMID: 34302272. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang X, Wang J, Hu H, et al. Fear of disease progression, self-management efficacy, and family functioning in patients with breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2024; 15:1400695. PMID: 39045441. [CrossRef]

- Cetera GE, Facchin F, Viganò P, et al. “SO FAR AWAY” How Doctors Can Contribute to Making Endometriosis Hell on Earth. A Call for Humanistic Medicine and Empathetic Practice for Genuine Person-Centered Care. Int J Womens Health. 2024;16:273–287. PMID: 38405184. [CrossRef]

- Evans S, Fernandez S, Olive L, et al. Psychological and mind-body interventions for endometriosis: A systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2019; 124:109756. PMID: 31443810. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).