1. Introduction

Vitiligo is a chronic dermatological condition characterized by the progressive destruction of epidermal melanocytes, resulting in well-defined hypopigmented macules and patches with irregular progression patterns (Bergqvist & Ezzedine, 2020; Liu et al., 2025; Samela et al., 2023). As one of the most prevalent skin conditions worldwide, vitiligo affects between 0.5% and 2% of the global population, transcending boundaries of gender, skin color, and age (Cao et al., 2024; Marchioro et al., 2022; Quaade et al., 2021). The condition manifests in two primary forms, each with distinct characteristics and progression patterns. Segmental Vitiligo (SV) typically presents unilaterally with rapid initial progression followed by stabilization, encompassing focal, unisegmental, and multisegmental subtypes (Benzekri et al., 2024; Bergqvist & Ezzedine, 2020; Do Bú et al., 2017). In contrast, Nonsegmental Vitiligo (NSV) (i.e., the more common variant) is characterized by symmetrical bilateral patches with slower progression over time. NSV includes several subtypes: acrofacial (i.e., affecting distal extremities and face), mucosal (i.e., involving oral and genital mucosae), generalized (i.e., bilateral symmetrical distribution), universal (i.e., near-complete depigmentation), mixed (i.e., concurrent SV and NSV), and rare variants such as leukoderma punctata and follicular vitiligo (Bergqvist & Ezzedine, 2020; Do Bú et al., 2022).

Despite extensive research, the pathogenesis of vitiligo remains incompletely understood, with researchers proposing multiple interconnected mechanisms including genetic predisposition, autoimmunity, oxidative stress, inflammatory mediator production, and cellular detachment processes (Marchioro, 2022; Spritz & Santorico, 2021). While endogenous factors such as genetic susceptibility and autoimmune dysfunction play crucial roles in the skin condition susceptibility, the heterogeneous nature of triggering factors presents a complex clinical picture (Said-Fernandez et al., 2021). However, emerging evidence increasingly highlights the significant role of psychological factors in both vitiligo onset and progression. Emotional triggers arising from stressful life events (e.g., including family loss, relationship dissolution, and occupational or financial difficulties) have been identified as important exogenous precipitating factors (Condamina et al., 2022; Do Bú et al., 2018; Haulrig et al., 2024). This relationship between psychological stress and vitiligo creates a potentially cyclical pattern, where emotional distress may trigger the dermatological condition onset, while the visible manifestations of vitiligo subsequently generate additional psychological burden (Do Bú et al., 2018; Do Bú et al., 2022).

In fact, the psychosocial implications of vitiligo extend far beyond cosmetic concerns, impacting patients’ quality of life and social functioning (Do Bú et al., 2019; Do Bú et al., 2021; Hedayati et al., 2023; Samela et al., 2023). Individuals with vitiligo frequently encounter discrimination and prejudice, including fears of contagion, assumptions about poor hygiene, and social withdrawal from physical contact, which collectively compromise their interpersonal relationships and emotional well-being (Do Bú et al., 2024). The associated stigma can severely impact body image, resulting in diminished self-esteem, interpersonal difficulties, and compromised intimate relationships, ultimately creating a feedback loop that may influence skin condition progression (Kussainova et al., 2020; Maamri & Badri, 2021; Saikarthik et al., 2022).

However, critical gaps remain in our understanding of how vitiligo affects different demographic groups. Research suggests that the psychological impact of vitiligo varies significantly across populations, with women experiencing higher rates of quality-of-life impairment and more severe mental health consequences across various psychopathological domains compared to men (Do Bú et al., 2021; Nasser et al., 2021; Samela et al., 2023; Szabo & Brandão, 2016). This disparity appears to be driven by multiple interconnected factors. Experience of stigma, for example, emerges as the major potential contributor to impaired health-related quality of life in women with vitiligo, reflecting broader societal pressures surrounding physical appearance that disproportionately affect women (Abdullahi et al., 2021). Research demonstrates women’s greater reactivity compared to men, which has been attributed to gender differences in biological and emotional responses, self-concepts, and coping styles (Sawant et al., 2019). Furthermore, women with skin conditions are more likely to experience dysmorphic concern and body dysmorphic disorder versus men (Sampogna et al., 2025), suggesting that visible dermatological conditions may interact with gendered vulnerability to appearance-related distress in ways that amplify psychological burden for women.

The burden may also vary by social and cultural context, shaped by factors such as local stigma, norms around appearance, and access to care (Abduljabbar, 2024). Together, these patterns underscore the need for an intersectional approach that explicitly considers gender and cultural context when assessing the psychosocial burden of vitiligo and designing culturally appropriate psychological interventions and comprehensive care approaches that address both clinical and psychosocial dimensions of the condition.

Despite the recognition of vitiligo psychosocial toll, patients’ own accounts of what triggers and aggravates the condition remain underexamined. These lay attributions that are shaped by emotional experience, cultural norms, and social position, matter for diagnosis acceptance, treatment engagement, and quality of life. Evidence on how these perceptions vary by gender is scarcer, and much of the literature comes from WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich and Democratic) countries, constraining generalizability. Studying Brazil that is a large and culturally diverse society with uneven appearance norms and access to care offers a critical test of how context and gender structure perceived triggers and progression.

This study addresses that gap by examining how Brazilians with vitiligo understand the factors that initiate and worsen their skin condition, with particular attention to gender differences. Drawing from established research on gender differences in health perception and coping mechanisms, we hypothesize that participants will invoke both biological and psychosocial explanations, but with systematic variation by gender that reflects broader patterns of health attribution and emotional processing. Specifically, we expect women to more frequently attribute vitiligo onset and progression to emotional and psychological factors, consistent with research demonstrating that women are more likely to recognize and articulate the connections between emotional states and physical health outcomes (Kessler et al., 2005; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012). Conversely, we anticipate that men will more frequently cite concrete, external, or biomedical causes such as genetic factors, physical trauma, or environmental exposures. This prediction aligns with masculine gender role expectations that emphasize problem-focused coping, emotional restraint, and preference for tangible, controllable explanations for health problems (Courtenay, 2000; O’Brien et al., 2005). Using a mixed-methods design—inductive coding of open-ended responses combined with quantitative semantic-similarity (lexical network) analysis to compare co-occurrence patterns by gender—we aim to deliver a context-sensitive account of the gendered psychological burden of vitiligo in Brazil and to identify targets for gender-responsive, stigma-aware clinical care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

To investigate the subjective experiences and attributions of individuals with vitiligo, we recruited a non-probabilistic convenience sample of 232 Brazilian citizens with a dermatologist-confirmed diagnosis. The sample, predominantly female (68.5%), ranged in age from 18 to 70 years (M = 37.65 years, SD = 12.43). A majority of participants self-identified as white (50.1%) and had a higher education level (28%).

2.2. Instrument

To capture participants’ responses, we developed an online questionnaire centered on a single, open-ended question: “Do you associate the onset and progression of your vitiligo with any factor? If yes, which one(s)?” This qualitative approach was chosen to allow for the spontaneous emergence of participant-driven themes and attributions, avoiding the constraints of predefined response options. We also collected key sociodemographic data, including gender, age, and level of education.

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected over a 60-day period (i.e., September and October) in 2023 using the Qualtrics online platform. The survey link was strategically distributed via prominent social media platforms (i.e., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and WhatsApp) to access a broad and geographically dispersed national sample. To ensure data integrity, only responses from participants who were Brazilian citizens, at least 18 years of age, and had a dermatologist-confirmed diagnosis of vitiligo were included. Participants provided digital informed consent and, on average, completed the survey in approximately five minutes. Data collection proceeded until a point of theoretical saturation was reached, a qualitative criterion indicating that no new codes or themes were emerging from the incoming data (Sá, 1998), thereby ensuring the depth and richness of our findings.

2.4. Data Analysis Procedure

The data were analyzed using a two-step, mixed-methods approach that combined inductive qualitative coding with quantitative lexical analysis. First, two researchers with a background in Psychology coded participants’ open-ended responses to inductively identify key themes and attributions, such as ‘rumination’ and ‘family loss’ (Madeira et al., 2022). Any disagreements were resolved through consensus to ensure inter-rater reliability. Researchers were masked to our original hypotheses.

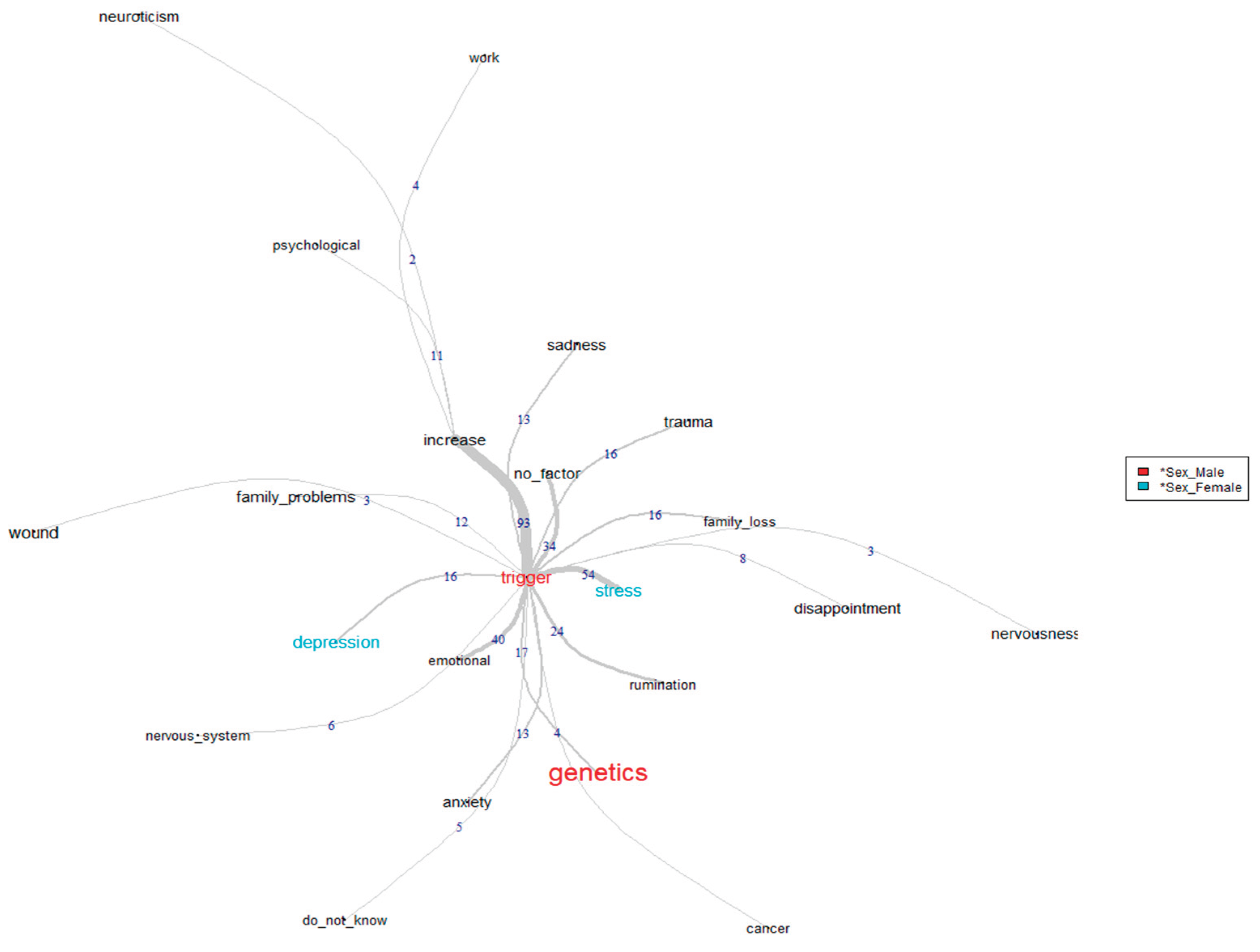

In the second step, we used Semantic Similarity Analysis, a technique within the IRaMuTeQ software, to visualize and quantify the relationships between these qualitative themes and our sociodemographic variable of gender (Camargo & Justo, 2013). This method allowed us to move beyond simple frequency counts to create a similarity tree, a network graph in which the size of a word’s vertex corresponds to its frequency, and the thickness of the edges reflects the strength of its co-occurrence with other words or with the gender variable (Monaco et al., 2017). This hybrid approach provided a robust, data-driven visualization of our qualitative findings, allowing us to identify and discuss gendered patterns in participant perceptions.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

The semantic similarity analysis revealed distinct patterns in how participants attributed vitiligo onset and progression, with notable gender differences emerging in the data.

Figure 1 illustrates the co-occurrence network of thematic clusters, revealing a predominantly psychological attribution pattern. The most frequently cited triggers were stress (

n = 54), emotional factors (

n = 40), rumination (

n = 26), genetics (

n = 17), depression (

n = 16), family loss (

n = 16), trauma (

n = 16), sadness (

n = 13), and anxiety (

n = 13). Additional factors with lower co-occurrences included disappointment (

n = 8), nervous system dysfunction (

n = 6), cancer (

n = 4), and nervousness (

n = 3). A key finding from our analysis was the significant gender disparity in these attributions, strongly supporting our primary hypothesis. Among participants citing psychological triggers, women demonstrated a pronounced tendency to associate vitiligo onset with stress and depression. Conversely, while genetic factors represented a smaller proportion of overall attributions, they were disproportionately cited by male participants, indicating a preference for biological rather than psychological explanations among men. This is exemplified in the following first-hand accounts:

In my case, it is associated with anxiety. It came up during the time that I got into school and felt really sick due to anxiety and apprehension before going to school every day.

(Female Participant 23)

I associate it to genetic factors. One of my cousins also has it.

(Male Participant 45)

(I associate it to) Emotional condition. Vitiligo came up when I broke up with a boyfriend by the age of 17. I treated the patches that appeared on my face and they went away. Later, at 21, when my mom passed away after having cancer for three years, the patches came back.

(Female Participant 201)

I associate the appearance of my vitiligo with burnout and stress.

(Male Participant 210)

My father’s brother has it. I’ve always thought it was just a family thing.

(Male Participant 12)

The analysis of progression factors, while also dominated by psychological themes, revealed a more generalized consensus across participants regardless of gender. The most frequent co-occurrences were for the concepts of psychological state (

n = 11), work-related stress (

n = 4), and neuroticism (

n = 2), as shown in

Figure 1. Notably, the lower frequency of progression-related attributions compared to onset triggers may reflect participants’ greater uncertainty about ongoing disease mechanisms or suggest that progression factors are less salient in participants’ illness narratives.

Unlike the onset triggers, these progression factors did not show significant gen-der-based clustering in the semantic network, indicating that both men and women similarly perceive psychological factors as influential in disease advancement once the condition has been established. Participants’ accounts consistently suggest that ongoing emotional and mental states are perceived as actively influencing the expansion of vitiligo patches:

I deem myself rather worried about a lot of things, I think I’m too neurotic, that must be why they (patches) won’t stop growing.

(Female Participant 2)

I think the state of mind influences my vitiligo growing.

(Male Participant 52)

My job stresses me a lot. I believe that the preoccupations over there (work) make my patches progress.

(Female Participant 117)

4. Discussion

The findings from this study suggest that Brazilians with vitiligo perceive their dermatological condition through a deeply psychological lens, yet the specifics of this narrative are distinctly shaped by gender. The consensus among participants was that emotional factors are central to the condition, but a clear divergence appeared in their initial attributions. Women frequently pointed to stress and depression as the primary triggers, framing their vitiligo as an outward sign of inner turmoil. Men, in contrast, were more likely to cite genetic factors, adopting a biomedical narrative that located the cause in biology rather than emotion. This fundamental difference in how vitiligo’s story is told speaks volumes about the gendered experience of health and distress. Interestingly, this gap seemed to close when participants discussed the condition’s progression, with both men and women agreeing that their psychological state influenced the spread of macules. It appears that while initial explanations are filtered through social norms, the lived experience of the condition fosters a shared recognition of the powerful link between mind and skin.

This perceived connection is not simply anecdotal; it resonates with our understanding of psychoneuroimmunology. The stress so many participants identified is a known activator of the body’s inflammatory pathways, which are implicated in the autoimmune response that targets melanocytes (Do Bú et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2025). This process can be magnified by cognitive styles and personality traits. The theme of neuroticism, for instance, points to a predisposition to experience negative emotions more acutely, potentially amplifying the perceived burden of the illness (Hedayati et al., 2023). This is often coupled with rumination, a pattern of obsessive worry that can create a vicious cycle: anxiety about the condition’s progression elevates stress, which in turn is believed to fuel the very progression that is feared (Do Bú et al., 2022; Hu & Wang, 2023).

The gendered nature of these attributions is rooted in powerful social scripts. Women’s focus on stress and depression reflects a socialization that not only permits but often expects emotional expression (Chaplin, 2015). This is compounded by the intense societal focus on female appearance, which can make a visible skin condition feel like a profound threat to one’s identity and social value (Casale et al., 2021; Schmid-Ott et al., 2007). For many women, linking vitiligo to an emotional cause is a coherent way to make sense of a deeply felt distress. Conversely, men’s reliance on a genetic explanation aligns with masculine norms that prize stoicism and emotional control (Courtenay, 2000). By attributing the condition to an unchangeable biological fact, the problem is externalized, separated from the realm of emotional vulnerability, which remains a difficult space for many men to navigate (O’Brien et al., 2005).

These insights have direct and practical implications for clinical care, demanding a move beyond purely dermatological treatments. The first step for any clinician is to validate the patient’s experience. Simple, open-ended questions like, “Many people I see with vitiligo notice a link between life events and their skin. Have you noticed anything like that?” can open a crucial dialogue and build trust. This allows for tailored psychoeducation. For a patient who attributes her vitiligo to stress, a clinician can affirm this by explaining the basic link between stress hormones and the immune system. For a patient who focuses solely on genetics, a clinician can validate that piece of the puzzle while gently introducing the idea that stress can act as a “switch” for genetic predispositions. This collaborative approach should lead to an integrated care pathway, ideally involving a “warm handover” to a mental health professional who understands the specific challenges of living with a visible chronic illness. A dermatologist might say, “I work with a psychologist who specializes in this area...” For those not ready or able to pursue formal therapy, clinicians can offer a menu of accessible tools, such as recommending mindfulness apps to manage stress or introducing basic concepts from cognitive behavioral therapy to challenge catastrophic thinking about the condition. Of course, the psychological burden is inseparable from the social context. Public health initiatives must work to dismantle the stigma that fuels so much of the anxiety associated with vitiligo. Campaigns that normalize skin differences in schools and workplaces are essential for creating environments where the stressors that patients believe trigger their condition are reduced (Do Bú et al., 2018; Do Bú et al., 2024).

This study, while illuminating, has limitations. The non-probabilistic, predominantly female sample restricts the generalizability of our findings. Future research must recruit larger, more diverse samples aiming to replicate these findings across different regions and socioeconomic strata of Brazil. However, as one of the first studies on this topic in Brazil, our work underscores the critical need for culturally-contextualized research. In a nation where skin color and appearance are woven into the fabric of social identity and hierarchy, a condition that alters pigmentation may carry a unique and profound weight. Future mixed-methods research should explore this intersectionality further. Longitudinal studies could also track how patients’ attributions evolve from diagnosis through long-term management, while in-depth qualitative interviews could give voice to the rich, personal narratives behind the patterns we have identified. Such work is essential for developing interventions that are not only evidence-based but also culturally and personally resonant.

5. Conclusions

This study illuminates vitiligo not merely as a loss of pigment, but as a condition deeply etched by the currents of human emotion and shaped by the contours of gender. For many, the skin becomes a canvas where internal struggles with stress and sorrow are made visible, a narrative told most often by women. For others, particularly men, it is a matter of genetic inheritance, a story told in the language of biology rather than feeling. Ultimately, these differing stories converge on a shared truth: the mind and the skin are inseparable. Recognizing this connection is paramount. Effective care must therefore look beyond the surface, attending to the psychological burdens that patients carry and tailoring support to the distinct ways men and women make sense of their experience. By listening to the stories our patients’ skin tells, we can move towards a more holistic and compassionate form of healing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and data colection, Emerson Do Bú, and Maria Edna Silva de Alexandre; methodology, Emerson Do Bú, Gabriella Tambara Nunes de Souza, Maria Edna Silva de Alexandre, and Vitória Medeiros dos Santos; software, Emerson Do Bú; formal analysis, Emerson Do Bú, Gabriella Tambara Nunes de Souza, Maria Edna Silva de Alexandre, Vitória Medeiros dos Santos, Washington Allysson Dantas Silva, Karla Santos Mateus, Marcus Vinícius Leal de Farias, and Guilherme Welter Wendt; writing—original draft preparation, Emerson Do Bú, Gabriella Tambara Nunes de Souza, Vitória Medeiros dos Santos; writing—review and editing, Emerson Do Bú, Gabriella Tambara Nunes de Souza, Maria Edna Silva de Alexandre, Vitória Medeiros dos Santos, Washington Allysson Dantas Silva, Karla Santos Mateus, Marcus Vinícius Leal de Farias, and Guilherme Welter Wendt; supervision, Emerson Do Bú. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Paraíba (protocol number: 69729117.8.0000.5188).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Grammarly and InstaText to assist with grammar and clarity. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abduljabbar, R. A. Vitiligo Causes and Treatment: A Review. Haya Saudi J Life Sci 2024, 9(5), 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, U.; Mohammed, T. T.; P Musa, B. O. Quality of life impairment amongst persons living with vitiligo using disease specific vitiligo quality of life index: A Nigerian perspective. The Nigerian postgraduate medical journal 2021, 28(3), 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzekri, L.; Cario-André, M.; Laamrani, F. Z.; Gauthier, Y. Segmental vitiligo distribution follows the underlying arterial blood supply territory: a hypothesis based on anatomo-clinical, pathological and physio-pathological studies. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11, 1424887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergqvist, C.; Ezzedine, K. Vitiligo: a review. Dermatology 2020, 236(6), 571–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, B. V.; Justo, A. M. IRAMUTEQ: Um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais. [IRAMUTEQ: A free software for analyzing textual data]. Temas em Psicologia 2013, 21(2), 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, S.; Gemelli, G.; Calosi, C.; Giangrasso, B.; Fioravanti, G. Multiple exposure to appearance-focused real accounts on Instagram: Effects on body image among both genders. Current Psychology 2021, 40, 2877–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Lin, F.; Jin, R.; Lei, J.; Zheng, Y.; Sheng, A.; Xu, W.; Xu, A.; Zhou, M. Anxiety - depression: a pivotal mental factor for accelerating disease progression and reducing curative effect in Vitiligo patients. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, 1454947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, T. M. Gender and emotion expression: A developmental contextual perspective. Emotion Review 2015, 7(1), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condamina, M.; Shourick, J.; Seneschal, J.; Sbidian, E.; Andreu, N.; Pane, I.; Ravaud, P.; Tran, V. T.; Ezzedine, K. Factors associated with perceived stress in patients with vitiligo in the ComPaRe e-cohort. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 2022, 86(3), 696–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courtenay, W. H. Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men's well-being: a theory of gender and health. Social science & medicine (1982) 2000, 50(10), 1385–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E.; de Alexandre, M. E. S.; Coutinho, M. da P. de L. Representações sociais do vitiligo elaboradas por brasileiros marcados pelo branco. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças 2017, 18, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E.; Alexandre, M. E. S.; Santos, V. M. Quality of Life of People with Vitiligo: A Brazilian Exploratory Study. Revista de Psicologia da IMED 2021, 3(1), 264–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E.; Alexandre, M. E. S.; Scardua, A.; Araújo, C. R. F. Vitiligo as a Psychosocial Disease: Apprehensions of Patients Imprinted by the White. Interface (Botucatu) 2018, 22, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E.; Coutinho, M. P. L. Representational Structure of Vitiligo: Non-Restrictive Skin Marks. Trends in Psychology 2019, 27(3), 615–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E. A.; Santos, V. M.; Lima, K. S.; Pereira, C. R.; Alexandre, M. E. S.; Bezerra, V. A. S. Neuroticism, stress, and rumination in anxiety and depression of people with Vitiligo: An explanatory model. Acta Psychologica 2022, 227, 103613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Bú, E. A.; Pereira, C. R.; Roberto, M. S. V. D.; Alexandre, M. E. S. d.; Silva, K. C.; Scardua, A.; Lima, K. S. The white human stain: Assessing prejudice towards people with vitiligo. Stigma and Health 2024, 9(2), 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haulrig, M. B.; Al-Sofi, R.; Baskaran, S.; Bergmann, M. S.; Løvendorf, M.; Dyring-Andersen, B.; Skov, L.; Loft, N. The global epidemiology of Vitiligo: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the incidence and prevalence. JEADV Clinical Practice 2024, 2024, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, A.; Mani, A.; Hamidizadeh, N.; Chohedri, E.; Moradi Khalaj, H.; Moshfeghinia, R.; Oji, B. Association of Personality Traits with Treatment Adherence in Vitiligo. Journal of Iranian Medical Council 2023, 6(3), 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Wang, T. Beyond skin white spots: Vitiligo and associated comorbidities. Frontiers in Medicine 2023, 10, 1072837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R. C.; Berglund, P.; Demler, O.; Jin, R.; Merikangas, K. R.; Walters, E. E. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry 2005, 62(6), 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kussainova, A.; Kassym, L.; Akhmetova, A.; Glushkova, N.; Sabirov, U.; Adilgozhina, S.; Tuleutayeva, R.; Semenova, Y. Vitiligo and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos one 2020, 15(11), e0241445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Ma, W.; Xue, X.; Li, S. The Neuro-Endocrinal Regulation in Vitiligo. Pigment cell & melanoma research 2025, 38(4), e70029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamri, A.; Badri, T. Sexual disorders in patients with vitiligo. La Tunisie Medicale 2021, 99(5), 504. Available online: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8759316/.

- Madeira, F.; Costa-Lopes, R.; Do Bú, E.; Marinho, R. T. The Role of Stereotypical Information on Medical Judgements for Black and White Patients. PlosOne 2022, 17(6), e0268888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioro, H. Z.; Castro, C. C. S. D.; Fava, V. M.; Sakiyama, P. H.; Dellatorre, G.; Miot, H. A. Update on the pathogenesis of vitiligo. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 2022, 97(4), 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaco, G.; Piermatteo, A.; Rateau, P.; Tavani, J. L. Methods for studying the structure of social representations: A critical review and agenda for future research. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 2017, 47, 306–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasser, M. A. E. M.; Raggi El Tahlawi, S. M.; Abdelfatah, Z. A.; Soltan, M. R. Stress, anxiety, and depression in patients with vitiligo. Middle East Current Psychiatry 2021, 28, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S. Emotion regulation and psychopathology: the role of gender. Annual review of clinical psychology 2012, 8, 161–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Brien, R.; Hunt, K.; Hart, G. 'It's caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate': men's accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Social science & medicine 2005, 61(3), 503–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaade, A. S.; Simonsen, A. B.; Halling, A. S.; Thyssen, J. P.; Johansen, J. D. Prevalence, incidence, and severity of hand eczema in the general population–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Contact Dermatitis 2021, 84(6), 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said-Fernandez, S. L.; Sanchez-Domínguez, C. N.; Salinas-Santander, M. A.; Martinez-Rodriguez, H. G.; Kubelis-Lopez, D. E.; Zapata-Salazar, N. A.; Vazquez-Martinez; Wollina, U.; Lotti, T.; Ocampo-Candiani, J. Novel immunological and genetic factors associated with vitiligo: A review. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 2021, 21(4), 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saikarthik, P.; Reddy, V. H.; Rafi, S. M.; Basha, V. W.; Padmakar, S. A Systematic Review on Prevalence and Assessment of Sexual Dysfunction in Vitiligo. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 2022, 70(10), 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samela, T.; Malorni, W.; Matarrese, P.; Mattia, G.; Alfani, S.; Abeni, D. Gender differences in vitiligo: psychological symptoms and quality of life assessment description. Frontiers in Psychology 2023, 14, 1234734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampogna, F.; Samela, T.; Abeni, D.; Schut, C.; Kupfer, J.; Bewley, A. P.; Finlay, A. Y.; Gieler, U.; Thompson, A. R.; Gracia-Cazaña, T.; Balieva, F.; Ferreira, B. R.; Jemec, G. B.; Lien, L.; Misery, L.; Marron, S. E.; Ständer, S.; Zeidler, C.; Szabó, C.; Szepietowski, J. C.; European Society for Dermatology and Psychiatry (ESDaP) Study collaborators. A cross-sectional study on gender differences in body dysmorphic concerns in patients with skin conditions in relation to sociodemographic, clinical and psychological variables. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2025, 39(4), 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, N. S.; Vanjari, N. A.; Khopkar, U. Gender Differences in Depression, Coping, Stigma, and Quality of Life in Patients of Vitiligo. Dermatology research and practice 2019 2019, 6879412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Ott, G.; Künsebeck, H. W.; Jecht, E.; Shimshoni, R.; Lazaroff, I.; Schallmayer, S.; Calliess, P.; Malewski, F.; Lamprecht, A.; Götz, A. Stigmatization experience, coping and sense of coherence in Vitiligo patients. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2007, 21(4), 456–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spritz, R. A.; Santorico, S. A. The genetic basis of vitiligo. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2021, 141(2), 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, I.; Brandão, E. R. Mata de tristeza!: representações sociais de pessoas com Vitiligo atendidas na Farmácia Universitária da Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. [It kills with sadness!: social representations of people with Vitiligo treated at the University Pharmacy of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil]. Interface-Comunicação, Saúde, Educação 2016, 20(59), 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).